- Guide to the Cambridge C2 Proficiency Writing Exam – Part 1: Essay

- Posted on 19/04/2023

- Categories: Blog

Are you preparing for the Cambridge C2 Proficiency (CPE) writing exam? If so, you may be feeling a little nervous and concerned about what lies ahead . Let us help put that fear and anxiety to bed and get started on how your academic writing can leave a positive impression on the examiner.

By the end of this blog post, you’ll know exactly what you need to do, how to prepare and how you can use your knowledge of other parts of the exam to help you.

Although you’ll find the advanced writing skills you’ve mastered at C1 will stand you in good stead for C2 writing, there are clear differences in the exam format in CPE. As in Cambridge C1, there are two parts in the writing exam, and understanding what you need to do before you’ve even put a pen to paper is incredibly important. So, let’s go!

What’s in Part 1?

First, let’s look at the format of Part 1:

- Task: essay.

- Word count: 240–280 words.

- Register: formal.

- Overview: a summary of two texts and an evaluation of the ideas.

- Suggested structure: introduction, paragraph 1, paragraph 2, conclusion.

- Time: 1 hour 30 minutes for Part 1 and 2.

Before we look at an example task, let’s look at how your paper will be assessed. The examiner will mark your paper using four separate assessment scales:

- Content – this demonstrates your ability to complete the task, including only relevant information.

- Communicative achievement – this shows how well you’ve completed the task, having followed the conventions of the task, used the correct register and maintained the reader’s attention throughout.

- Organisation – the overall structure of your essay, the paragraphs and the sentences.

- Language – your ability to use a wide range of C2 grammar and vocabulary in a fluent and accurate way.

How can I write a fantastic essay?

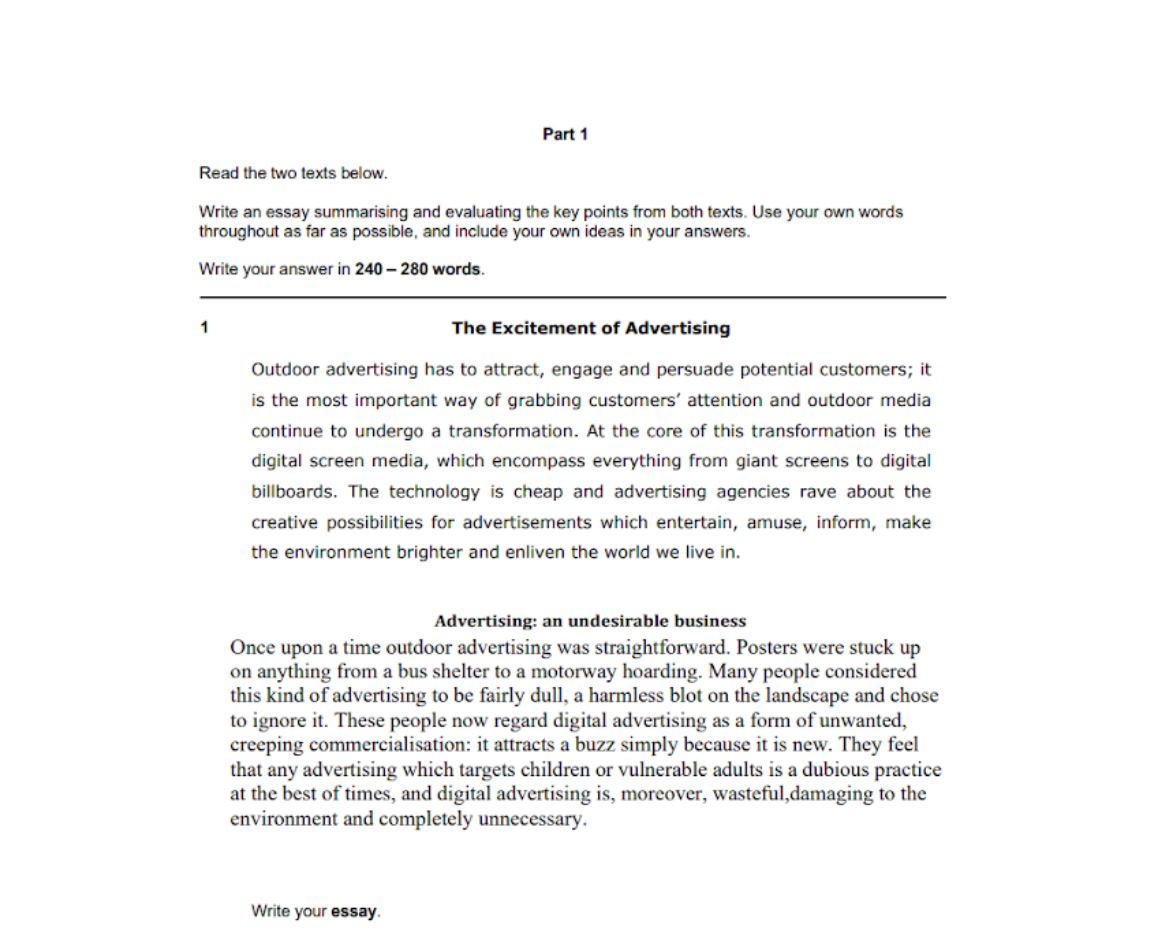

Let’s look at an example task:

The key things you’re being asked to do here are summarise, evaluate and include your own ideas, using your own words as far as possible. So, in short, you have to paraphrase. As a Cambridge exams expert, you’ll know that this is a skill you already use throughout the exam.

In Reading and Use of English Part 4, the techniques you are using to make the keyword transformations (active to passive, comparative structures, negative inversions, common word patterns, etc) will show you that you already know how you can say the same thing in other words.

Your ability to do word formation in Reading and Use of English Part 3 is useful here, as you look for verbs that you can change into nouns, and vice versa. This enables you to say reword sentences without losing the original meaning.

You are already adept at identifying the correct options in Reading and Use of English Part 5 and Listening Parts 1 and 3, although the words given are different to the information in the text or audio.

So, be aware of the skills you have already practised, and use them to your advantage!

How should I plan and structure my essay?

Before you even consider writing, read both texts thoroughly . Highlight the key points in each text and make notes about how you can express this in your own words. Look for contrasting opinions and think about how you can connect the ideas together. These contrasting ideas will usually form the basis of paragraphs 2 and 3.

Although there are multiple ways you can organise your essay, here is a tried and tested structure:

Paragraph 1: Introduction

Paragraph 2: Idea 1 with support

Paragraph 3: Idea 2 with support

Paragraph 4: Conclusion

Introduction

Use your introduction as a way to present the general theme. Don’t give anything away in terms of your own opinion, but instead give an overview of what you will discuss. Imagine this as a global comment, talking about how society as a whole may feel about the topic.

Start with a strong sentence. Make your intentions clear, then back up your idea with a supporting sentence and elaborate on it. Use linkers to show how this idea has different stances, paraphrased from the key points you highlighted in the texts.

Follow the same structure as Idea 1, but focus on a different element from the two texts. Introduce it clearly, then provide more support to the idea. Keep emotional distance from the topic – save your opinion for the conclusion!

Here is the opportunity for you to introduce your personal opinion. There shouldn’t be anything new included here other than how you personally feel about the topics discussed. Use your conclusion to refer back to the main point and round up how your opinion differs or is similar.

This is just one example of how you can structure your essay. However, we recommend trying different formats. The more you practise, the more feedback you’ll get from your teacher. Once you’ve settled on the structure that suits you, your planning will be a lot quicker and easier.

What can I do to prepare?

According to the Cambridge English website, ‘A C2 Proficiency qualification shows the world that you have mastered English to an exceptional level. It proves you can communicate with the fluency and sophistication of a highly competent English speaker.’

This means that being a proficient writer in your own language is not enough. So, what can you do to really convince the examiner that you truly are smarter than the average Joe ?

Prepare! Prepare! Prepare!

✔ Read academic texts regularly.

✔ Pay attention to model essay answers and highlight things that stand out.

✔ Always try to upgrade your vocabulary. Challenge yourself to think of synonyms.

✔ Write frequently and study the feedback your teacher gives you.

✔ Study C2 grammar and include it in your writing.

What do I need to avoid?

Don’t overuse the same linkers. Practise using different ones and not only in essays. You can write something much shorter and ask your teacher to check for correct usage.

- Don’t constantly repeat the same sentence length and punctuation. Long sentences may seem the most sophisticated, but you should consider adding shorter ones from time to time. This adds variety and a dramatic effect. Try it!

- Don’t be discouraged by your mistakes – learn from them! If you struggle with a grammar point, master it. If you spell something incorrectly, write it again and again.

- Don’t limit your English studying time. Do as much as possible in English – watch TV, read, listen to podcasts, or meet with English speaking friends. English time should not only be reserved for the classroom.

What websites can help me?

The Official Cambridge English page, where you can find a link to sample papers.

BBC Learning English has a range of activities geared towards advanced level learners.

Flo-joe has very useful writing practice exercises that allow you to see other students’ writing.

Writing apps and tools like Grammarly can improve your writing style with their feedback and suggestions.

Don’t forget about our fantastic C2 blogs too!

Passing Cambridge C2 Proficiency: Part 3 Reading and Use of English

Passing C2 Proficiency: A Guide to Reading Part 5

Passing C2 Proficiency: A Guide to Reading Part 6

Guide to the Cambridge C2 Proficiency Listening Test

Guide to the Cambridge C2 Proficiency Speaking Test

Looking for further support?

If you’re interested in preparing for the C2 Proficiency exam but don’t know where to start, get in touch with us here at Oxford House today! We offer specific courses that are designed especially to help you get ready for the exam. Let our fully qualified teachers use their exam experience to guide you through your learning journey. Sign up now and receive your free mock test!

Glossary for Language Learners

Find the following words in the article and then write down any new ones you didn’t know.

lie ahead (pv): be in the future.

stand you in good stead (id): be of great use to you.

adept at (adj): have a good ability to do something.

thoroughly (adv): completely.

tried and tested (adj): used many times before and proved to be successful.

back up (pv): give support to.

round up (pv): summarise.

settle on (pv): choose after careful consideration

average Joe (n): normal person.

discouraged (adj): having lost your enthusiasm or confidence.

pv = phrasal verb

adj = adjective

Leave a Reply

Name (required)

Email (required)

Improve your English pronunciation by mastering these 10 tricky words

- Posted on 05/04/2023

5 Spelling Rules For Comparative And Superlative Adjectives

- Posted on 03/05/2023

Related Post

A Guide to English Accents Aro

Countries can have extremely different English accents despite sharing the same language. Just take the word ‘water’... Read More

Passing Cambridge C2 Proficien

Many sections of the Cambridge Proficiency are multiple-choice, so Part 2 of the Reading and Use of English can seem cha... Read More

Exploring the Impact of AI in

Gone are the days of learning from phrasebooks and filling in worksheets for homework. Now students have access to a wid... Read More

Everything You Need To Know Ab

Although you learn plural nouns early on, they can be challenging. There are many rules and exceptions to remember plus ... Read More

The Importance of English For

No matter where you live, you’ve probably experienced record-breaking temperatures and severe weather. You may have se... Read More

Discovering Barcelona Through

We all know that Barcelona is a fantastic city to live in. You only need to spend the afternoon wandering around one of ... Read More

8 New Words To Improve Your Vo

The arrival of a new year presents an ideal opportunity to work on your language goals. Whether you’re preparing for a... Read More

Learning English through Chris

It’s beginning to look a lot like Christmas! If you resisted the urge to sing that line instead of saying it, then, we... Read More

24 Christmas Phrases for Joyfu

‘Tis the season to be jolly, and what better way to get ready for the festive period than by learning some typical Chr... Read More

3 Easy Ways To Use Music To Im

Are you ready to embark on your latest journey towards mastering the English language? We all know that music is there f... Read More

Grammar Guide – Understandin

Do you sometimes feel a bit lost when deciding which tense to use? Are you a little unsure of the differences between th... Read More

Halloween Humour: Jokes, Puns

We all need a break from time to time. Sometimes we’re up to our eyeballs in projects at work, and we just need a mome... Read More

English for Business: 7 Ways L

If you’re interested in getting a promotion at work, earning a higher salary or landing your dream job, then working o... Read More

A Beginner’s Guide to Ch

Understanding the need for exams An official exam is a fantastic way to demonstrate your English. Why? Firstly,... Read More

English Tongue Twisters to Imp

One of the most fun ways to practise and improve your pronunciation is with tongue twisters. That’s because they’re ... Read More

25 years of Oxford House – O

We all know that fantastic feeling we have after completing an academic year: nine months of English classes, often twic... Read More

Guide to the Cambridge C2 Prof

Are you working towards the Cambridge C2 Proficiency (CPE) exam? Have you been having sleepless nights thinking about wh... Read More

9 Tips For Communicating With

When travelling to or living in an English-speaking country, getting to know the local people can greatly enhance your e... Read More

Are you preparing for the Cambridge C2 Proficiency (CPE) writing exam? If those pre-exam jitters have started to appear,... Read More

English Vocabulary For Getting

Are you feeling bored of the way your hair looks? Perhaps it’s time for a new you. All you need to do is make an appoi... Read More

5 Spelling Rules For Comparati

Messi or Ronaldo? Pizza or sushi? Going to the cinema or bingeing on a series at home? A beach holiday or a walking trip... Read More

Improve your English pronuncia

What are some of the trickiest words to pronounce in English? Well, we’ve compiled a useful list of ten of the most di... Read More

Using Language Reactor To Lear

If you love watching Netflix series and videos on YouTube to learn English, then you need to download the Language React... Read More

Are you preparing for the Cambridge C2 Proficiency (CPE) exam? Would you like to know some tips to help you feel more at... Read More

How to use ChatGPT to practise

Are you on the lookout for an extra way to practise your English? Do you wish you had an expert available at 2 a.m. that... Read More

Well done. You’ve been moving along your English language journey for some time now. You remember the days of telling ... Read More

Tips for the IELTS listening s

Are you preparing for the IELTS exam and need some help with the listening section? If so, then you’ll know that the l... Read More

7 new English words to improve

A new year is a perfect opportunity to focus on your language goals. Maybe you are working towards an official exam. Per... Read More

How to Write a C1 Advanced Ema

Did you know that there are two parts to the C1 Advanced Writing exam? Part 1 is always a mandatory . Part 2 has ... Read More

5 Interesting Christmas tradit

When you think of the word Christmas, what springs to mind? For most people, it will be words like home, family and trad... Read More

How to write a C1 Advanced Rep

Are you preparing for the Cambridge C1 Advanced exam and need a hand with writing your report/proposal for Part 2 of the... Read More

5 of the best apps to improve

Would you like to improve your English listening skills? With all the technology that we have at our fingertips nowadays... Read More

Tips for the IELTS Reading sec

Looking for some tips to get a high band score in the IELTS Academic Reading exam? If so, then you’re in the right pla... Read More

The 5 best Halloween movies to

Boo! Are you a fan of Halloween? It’s that scary time of year again when the creepy creatures come out to play, and th... Read More

How to Write a Review for Camb

Are you planning to take the Cambridge C1 Advanced (CAE) exam? If so, you will need to complete two pieces of writin... Read More

How To Use Relative Pronouns i

Today we’re taking a look at some English grammar that sometimes trips up language learners. In fact, we’ve just use... Read More

How To Get Top Marks: Cambridg

So you’re taking the ? If so, you’ll know that you have four sections to prepare for: speaking, reading and use of E... Read More

Travel Vocabulary To Get Your

Summer is here and we can’t wait to go on our summer holidays! If you’re thinking about travelling overseas this yea... Read More

How To Get A High Score In The

So you’re preparing for the ! From wanting to live and work abroad to going to university in an English-speaking count... Read More

10 English Idioms To Take To T

Is there anything better than cooling off in the sea on a hot summer’s day? Well, if you live in Barcelona you hav... Read More

Tips for IELTS speaking sectio

Are you preparing for the IELTS test? If so, you’ll need to do the speaking section. While many people find speaking t... Read More

How to use 6 different English

Just when you think English couldn’t get any more confusing, we introduce you to English pronouns! The reason why peop... Read More

How to get top marks: B2 First

Congratulations – you’ve made it to the B2 First Reading and Use of English Part 7! Yet, before we get too excited, ... Read More

5 Of The Best Apps For Improvi

Speaking is often thought to be the hardest skill to master when learning English. What’s more, there are hundreds of ... Read More

Do you like putting together puzzles? If so, your problem solving skills can actually help you with B2 First Reading and... Read More

8 Vocabulary Mistakes Spanish

If you ask a Spanish speaker what they find difficult about English language learning, they may mention false friends an... Read More

How To Get Top Marks: B2 First

Picture this: You’re in your B2 First exam and you’ve finished the Use of English part. You can put it behind you fo... Read More

12 Business Phrasal Verbs to K

Want to improve your English for professional reasons? You’re in the right place. When working in English, it’s comm... Read More

How to use articles (a, an, th

Knowing what articles are and when to use them in English can be difficult for language learners to pick up. Especially ... Read More

Are you preparing for ? Reading and Use of English Part 4 may not be your cup of tea – in fact most students feel quit... Read More

Passing B2 First Part 3: Readi

Are you studying for the B2 First exam? You’re in the right place! In this series of blogs we want to show you al... Read More

8 new English words you need f

New words spring up each year! They often come from popular culture, social and political issues, and innovations in tec... Read More

7 of the Best Apps for Learnin

If you find yourself commuting often and spending a lot of time on the bus, you’ll most likely turn towards playing ga... Read More

The B2 First is one of the most popular English exams for students of English. It is a recognised qualification that can... Read More

4 Different Types Of Modal Ver

What are modal verbs? They are not quite the same as regular verbs such as play, walk and swim. Modal verbs are a type o... Read More

So you’ve decided to take the ! Formerly known as FCE or the First Certificate, this is by far most popular exam. Whe... Read More

Useful Expressions For Negotia

A lot of our global business is conducted in English. So, there’s a strong chance you may have to learn how to negotia... Read More

Passing C1 Advanced Part 8: Re

If you’re wondering how to do Part 8 of the Reading and Use of English paper, you’re in the right place! After s... Read More

The Difference Between IELTS G

You’ve probably heard of . It’s the world’s leading test for study, work and migration after all. And as the world... Read More

Passing C1 Advanced Part 7: Re

Welcome to Part 7 of the Reading and Use of English paper. This task is a bit like a jigsaw puzzle. One where you have ... Read More

The Benefits Of Learning Engli

Who said learning English was just for the young? You're never too old to learn something new. There are plenty of benef... Read More

So, you’re preparing to take the . You’ve been studying for each of the four sections; reading, writing, speaking an... Read More

6 Reels Accounts to Learn Engl

Are you looking for ways to learn English during the summer holidays? We’ve got you covered – Instagram Reels is a n... Read More

Passing Cambridge C1 Advanced

Well done you! You’ve made it to Part 6 of the Reading and Use of English exam. Not long to go now – just three mor... Read More

8 Resources To Help Beginner E

Learning a new language is hard, but fun. If you are learning English but need some help, our monthly course is what y... Read More

5 Famous Speeches To Help you

Everyone likes listening to inspiring speeches. Gifted speakers have a way of making people want to listen and take acti... Read More

How To Write A B2 First Formal

Dear reader… We sincerely hope you enjoyed our previous blog posts about the Writing section of the B2 First. As promi... Read More

4 Conditionals In English And

Conditionals? Is that something you use after shampooing your hair? Not quite. You may have heard your English teacher t... Read More

After racing through the first four parts of the Cambridge English Reading and Use of English paper, you’ve managed t... Read More

7 Of The Best Apps For Learnin

There are roughly 170,000 words in use in the English language. Thankfully, most native English speakers only have a voc... Read More

How to write a B2 First inform

You're probably very familiar with sending emails (and sometimes letters) in your first language. But how about in Engli... Read More

How can I teach my kids Englis

Keep kids’ minds sharp over the Easter holidays with some entertaining, educational activities in English. There are l... Read More

How Roxana went from Beginner

Roxana Milanes is twenty five and from Cuba. She began English classes back in May 2019 at Oxford House, and since then ... Read More

4 Future Tenses In English And

“Your future is whatever you make it, so make it a good one.” - Doc Brown, Back to the future. Just like the and... Read More

10 Business Idioms For The Wor

Business idioms are used throughout the workplace. In meetings, conversations and even whilst making at the coffee mac... Read More

5 Tips For Reading The News In

We spend hours consuming the news. With one click of a button we have access to thousands of news stories all on our pho... Read More

How To Write a Report: Cambrid

Imagine the scene. It’s exam day. You’re nearly at the end of your . You’ve just finished writing Part 1 - , and n... Read More

8 English Words You Need For 2

Back in December 2019, we sat down and attempted to make a list of . No one could have predicted the year that was about... Read More

5 Christmas Movies On Netflix

Christmas movies are one of the best things about the holiday season. They’re fun, they get you in the mood for the ho... Read More

MigraCode: An Inspiring New Pa

Oxford House are extremely proud to announce our partnership with MigraCode - a Barcelona-based charity which trains ref... Read More

The Ultimate Guide To Video Co

The age of telecommunication is well and truly here. Most of our business meetings now take place via video conferencing... Read More

6 Pronunciation Mistakes Spani

One of the biggest challenges for Spanish speakers when learning English is pronunciation. Often it’s a struggle to pr... Read More

6 Ways You Can Learn English w

“Alexa, what exactly are you?” Alexa is a virtual AI assistant owned by Amazon. She is voice-activated - like Sir... Read More

Passing Cambridge C1 Advanced:

Okay, take a deep breath. We’re about to enter the danger zone of the Cambridge exam - Reading and Use of English Par... Read More

What’s new at Oxford House f

Welcome to the new school year! It’s great to have you back. We’d like to remind you that , and classes are all st... Read More

European Languages Day: Where

The 26th of September is . It’s a day to celebrate Europe’s rich linguistic diversity and show the importance of lan... Read More

Back To School: 9 Tips For Lan

It’s the start of a new academic term and new courses are about to begin. This is the perfect opportunity to set your ... Read More

How to Maximise Your Online Co

If there’s one good thing to come out of this year, it’s that learning a language has never been so easy or accessib... Read More

How To Learn English With TikT

Are you bored of Facebook? Tired of Instagram? Don’t feel part of the Twitter generation? Perhaps what you’re lookin... Read More

A Brief Guide To Different Bri

It’s a fact! The UK is obsessed with the way people talk. And with , it’s no surprise why. That’s right, accents a... Read More

Study English This Summer At O

Summer is here! And more than ever, we’re in need of a bit of sunshine. But with travel restrictions still in place, m... Read More

5 Reasons To Learn English Out

As Barcelona and the rest of Spain enters the ‘new normality’, it’s time to plan ahead for the summer. Kids and te... Read More

5 Free Online Resources For Ca

Are you preparing for a Cambridge English qualification? Have you devoured all of your past papers and need some extra e... Read More

6 Different Uses Of The Word �

The word ‘get’ is one of the most common and versatile verbs in English. It can be used in lots of different ways, a... Read More

What Are The 4 Present Tenses

There are three main verb tenses in English - , the present and the future - which each have various forms and uses. Tod... Read More

5 Of The Best Netflix Series T

On average, Netflix subscribers spend streaming their favourite content. With so many binge-worthy series out there, it... Read More

Continue Studying Online At Ox

Due to the ongoing emergency lockdown measures imposed by the Spanish Government . We don’t know when we will be a... Read More

Five Ways To celebrate Sant Jo

The feast of Sant Jordi is one of Barcelona’s most popular and enduring celebrations. Sant Jordi is the patron saint o... Read More

What’s It Like To Study Onli

Educational institutions all over the world have shut their doors. From nurseries to universities, business schools to l... Read More

6 Benefits of Learning English

Whatever your new year’s resolution was this year, it probably didn’t involve staying at home all day. For many of u... Read More

9 Tips For Studying A Language

With the recent outbreak of Covid-19, many of us may have to gather our books and study from home. Schools are clos... Read More

10 Ways To Learn English At Ho

Being stuck inside can make you feel like you’re going crazy. But why not use this time to your advantage, and work on... Read More

Important Information –

Dear students, Due to the recent emergency measures from the Government concerning COVID-19, Oxford House premises wi... Read More

7 Books You Should Read To Imp

Reading is one of the best ways to practice English. It’s fun, relaxing and helps you improve your comprehension skill... Read More

Your Guide To Moving To The US

So that’s it! It’s decided, you’re moving to the USA. It’s time to hike the soaring mountains, listen to country... Read More

How to write a C1 Advanced Ess

The is an excellent qualification to aim for if you’re thinking of studying or working abroad. It’s recognised by u... Read More

Small Talk For Business Englis

Like it or not, small talk is an important part of business. Whether it’s in a lift, at a conference, in a meeting roo... Read More

English Vocabulary For Going O

It’s time for that famous celebration of love and romance - Valentine’s Day! It is inspired by the sad story of Sain... Read More

IELTS: Writing Part 2 –

When it comes to exams, preparation is the key to success - and the IELTS Writing Paper Part 2 is no exception! It is wo... Read More

5 Unmissable Events at Oxford

At Oxford House, we know learning a language extends beyond the classroom. It’s important to practise your skills in m... Read More

Am I ready for the C1 Advanced

Congratulations! You’ve passed your Cambridge B2 First exam. It was a hard road but you did it. Now what’s next? Som... Read More

Ireland is known as the Emerald Isle. When you see its lush green landscape and breathtaking views, it’s easy to see w... Read More

How SMART Goals Can Help You I

New year, new you. As one year ends and another begins, many of us like to set ourselves goals in order to make our live... Read More

15 New English Words You Need

Each year new words enter the English language. Some are added to dictionaries like . Others are old words that are give... Read More

Our Year In Review: Top 10 Blo

2019 went by in a flash - and what a year it’s been! We’re just as excited to be looking back on the past 12 months ... Read More

Telephone Interviews In Englis

Telephone interviews in English can seem scary. Employers often use them to filter-out candidates before the face-to-fa... Read More

How to Write a Great Article i

Writing in your only language can be a challenge, but writing in another language can be a complete nightmare ! Where do... Read More

A Black Friday Guide to Shoppi

Black Friday is the day after Thanksgiving. Traditionally, it signals the start of the Christmas shopping period. Expect... Read More

Passing C1 Advanced: Part 3 Re

The (CAE) is a high-level qualification, designed to show that candidates are confident and flexible language users who... Read More

AI Translators: The Future Of

Many people believe that artificial intelligence (AI) translators are surpassing human translators in their ability to a... Read More

8 Of The Best Apps For Learnin

Apps are a great tool for learning English. They are quick, easy to access and fun. It’s almost like having a mini cla... Read More

6 Ways To Improve Your Speakin

There are four linguistic skills that you utilise when learning a new language: reading, writing speaking and listening.... Read More

So, you’ve moved onto Part 3, and after completing Part 2 it’s probably a welcome relief to be given some help with ... Read More

8 Resources To Build Your Busi

Whether it’s in meetings, telephone conversations or networking events, you’ll find specific vocabulary and buzzword... Read More

5 Ways to Become a Better Lear

It’s time for some back-to-school motivation. The new school year is about to start and everyone is feeling refreshed ... Read More

Our 10 Favourite YouTubers To

Haven’t you heard? Nobody is watching the TV anymore - 2019 is the year of the YouTuber! If you’re an English langu... Read More

So, you’ve completed the of your Cambridge C1 Advanced (CAE). Now it’s time to sit back and enjoy the rest of the e... Read More

The Secret French Words Hidden

“The problem with the French is that they have no word for entrepreneur.” This phrase was attributed to George W. B... Read More

The Ultimate Guide To Gràcia

The Gràcia Festival, or , is an annual celebration taking place in the lovely, bohemian neighbourhood of Gràcia in upt... Read More

5 Things To Do In Barcelona In

Barcelona residents will often tell you than nothing happens in August. It’s too hot and everyone escapes to little vi... Read More

4 Past Tenses and When to Use

Do you have difficulty with the past tenses in English? Do you know the difference between the past simple and past perf... Read More

How To Write A Review: Cambrid

Students who are taking their B2 First Certificate exam (FCE) will be asked to do two pieces of writing within an 80 min... Read More

8 Hidden Benefits of Being Bil

Unless you were raised to be bilingual, speaking two languages can require years of study and hard work. Even once you�... Read More

7 Films to Practise Your Engli

What’s better than watching a fantastic, original-language movie in a theatre? Watching a fantastic, original-language... Read More

The 10 Best Instagram Accounts

Ever wonder how much time you spend on your phone a day? According to the latest studies, the average person spends on ... Read More

Challenge Yourself This Summer

Here comes the sun! That’s right, summer is on its way and, for many, that means a chance to take a well-deserved brea... Read More

You’ve done the hard part and finally registered for your , congratulations! Now all you need to do is pass it! H... Read More

These 5 Soft Skills Will Boost

Everyone is talking about soft skills. They are the personal traits that allow you to be mentally elastic, to adapt to n... Read More

Which English Exam Is Right Fo

Are you struggling to decide which English language exam to take? You’re not alone: with so many different options on ... Read More

Passing C2 Proficiency: A Guid

We’re sure you’ve done a great job answering the questions for of your . But now you’re faced with a completely d... Read More

Sant Jordi – Dragons, Bo

Imagine you have woken up in Barcelona for the first time in your life. You walk outside and you notice something unusua... Read More

5 Ways To Improve Your Listeni

Have you ever put on an English radio station or podcast and gone to sleep, hoping that when you wake up in the morning ... Read More

The Simple Guide To Communicat

What’s the most challenging thing about going on holiday in an English speaking country? Twenty years ago you might ha... Read More

Stop Making These 7 Grammar Mi

No matter how long you've been learning a language, you're likely to make a mistake every once in a while. The big ones ... Read More

How To Pass Your First Job Int

Passing a job interview in a language that’s not your mother tongue is always a challenge – but however daunting i... Read More

5 Ways To Practise Your Speaki

“How many languages do you speak?” This is what we ask when we want to know about someone’s language skills... Read More

You have survived the Use of English section of your , but now you are faced with a long text full of strange language, ... Read More

Improve Your English Accent Wi

Turn on a radio anywhere in the world and it won’t take long before you’re listening to an English song. And, if you... Read More

10 English Expressions To Fall

It’s nearly Valentine’s day and love is in the air at Oxford House. We’ll soon be surrounded by heart-shaped ballo... Read More

7 Graded Readers To Help You P

Graded readers are adaptations of famous stories, or original books aimed at language learners. They are written to help... Read More

6 Tools To Take Your Writing T

Written language is as important today as it has ever been. Whether you want to prepare for an , to respond to or it’... Read More

EF Report: Do Spanish Schools

The new year is here and many of us will be making promises about improving our language skills in 2019. However, how ma... Read More

Our 10 Most Popular Blog Posts

It’s been a whirlwind 2018. We’ve made so many amazing memories - from our twentieth-anniversary party to some enter... Read More

Time For A Career Change? Here

Have you ever wondered what it would be like to get a job in an international company? Perhaps you’ve thought about tr... Read More

Eaquals Accreditation: A Big S

We are delighted to be going through the final stages of our accreditation, which will help us provide the best languag... Read More

A Guide To The Cambridge Engli

Making the decision to do a Cambridge English language qualification can be intimidating. Whether you’re taking it bec... Read More

8 Top Tips To Get The Most Out

A language exchange (or Intercambio in Spanish) is an excellent way to practise English outside of the classroom. The a... Read More

The Haunted History And Terrib

The nights are drawing in and the leaves are falling from the trees. As our minds turn to the cold and frosty winter nig... Read More

Why Oxford House Is More Than

If you’re a student at , you’ll know it is far more than just a language academy. It’s a place to socialise, make ... Read More

10 Crazy Things You Probably D

From funny bananas, super long words and excitable foxes, our latest infographic explores 10 intriguing facts about the ... Read More

Meet our Director of Studies &

If you’ve been studying at Oxford House for a while there’s a good chance that you’ll recognise Judy - with her bi... Read More

Which English Course Is Right

The new school year is about to begin and many of you are probably thinking that it’s about time to take the plunge an... Read More

5 Ways To Get Over The Holiday

We head off on vacation full of excitement and joy. It’s a time to explore somewhere new, relax and spend time with ou... Read More

10 Essential Aussie Expression

Learning English is difficult! With its irregular verbs, tricky pronunciation and even harder spelling, lots of students... Read More

5 Great Apps To Give Your Engl

The next time you’re walking down the street, in a waiting room, or on public transport in Barcelona take a look aroun... Read More

Here’s Why You Should Move T

Many students have aspirations to move abroad. This might be for a number of reasons such as to find a new job, to impro... Read More

Improving Your Pronunciation W

What do English, Maori, Vietnamese and Zulu have in common? Along with another , they all use the . If your first la... Read More

How To Improve Your English Us

Netflix has changed the way we spend our free time. We don’t have to wait a week for a new episode of our favourite TV... Read More

Oxford House Community: Meet O

The year has flown by and we are already into the second week of our summer intensive courses. Today we look back at th... Read More

6 Amazing Events to Make It an

Things are hotting up in Barcelona. There’s so much to see and do during the summer months that it’s hard to know wh... Read More

How to Improve Your English Ov

The long summer holiday is almost here and we’ve got some top tips on how you can keep up your English over the summer... Read More

World Cup Vocabulary: Let’s

Football, football, football: the whole world is going crazy for the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar! The beautiful game i... Read More

The 10 Characteristics Of A �

Learning a second language has a lot in common with learning to play an instrument or sport. They all require frequent p... Read More

Catch Your Child’s Imaginati

Imagine, for a moment, taking a cooking class in a language you didn’t know - it could be Japanese, Greek, Russian. It... Read More

Exam Day Tips: The Written Pap

Exams are nerve-wracking. Between going to class, studying at home and worrying about the results, it’s easy to forget... Read More

10 Reasons to Study English at

Learning a second language, for many people, is one of the best decisions they ever make. Travel, work, culture, educati... Read More

Shadowing: A New Way to Improv

Speech shadowing is an advanced language learning technique. The idea is simple: you listen to someone speaking and you ... Read More

The Best Websites to Help Your

Our children learn English at school from a young age - with some even starting basic language classes from as early as ... Read More

15 Useful English Expressions

When was the last time you painted the town red or saw a flying pig? We wouldn’t be surprised if you are scratchin... Read More

Help Your Teens Practise Engli

Teenagers today are definitely part of the smartphone generation and many parents are concerned about the amount of time... Read More

IELTS: Writing Part 1 –

Are you taking an IELTS exam soon? Feeling nervous about the writing paper? Read this article for some top tips and usef... Read More

Business skills: How to delive

Love them or hate them, at some point we all have to give a business presentation. Occasionally we have to deliver them ... Read More

10 phrasal verbs to help you b

A lot of students think English is easy to learn - that is until they encounter phrasal verbs! We are sure you have hear... Read More

6 Unbelievably British Easter

Have you heard of these fascinating British Easter traditions? Great Britain is an ancient island, full of superstition... Read More

Guide to getting top marks in

Your is coming to an end and exam day is fast approaching. It’s about time to make sure you are prepared for what man... Read More

4 Ways English Words are Born

Have you ever wondered where English words come from? There are a whopping 171,476 words in the . From aardvark to zyzz... Read More

Writing an effective essay: Ca

Students take language certifications like the Cambridge B2 First qualification for lots of different reasons. You might... Read More

5 Powerful Tools to Perfect Yo

Foreign accent and understanding When you meet someone new, what’s the first thing you notice? Is it how they look?... Read More

Essential Ski Vocabulary [Info

Are you a ski-fanatic that spends all week dreaming about white-capped peaks, fluffy snow and hearty mountain food? ... Read More

5 Tips to Get the Best Out of

Quizlet, Duolingo, Busuu...there are lots of apps on the market nowadays to help you learn and improve your English. But... Read More

10 False Friends in English an

Is English really that difficult? English is a Germanic language, which means it has lots of similarities with Germa... Read More

How to Improve your English wi

If you’ve been studying English for a long time, you’ve probably tried lots of different ways of learning the langua... Read More

Myths and Mysteries of the Eng

Learning another language as an adult can be frustrating. We’re problem-solvers. We look for patterns in language and ... Read More

10 Ways to Improve your Englis

Every year is the same. We promise ourselves to eat more healthily, exercise more and save money. It all seems very easy... Read More

10 English words you need for

Languages are constantly on the move and English is no exception! As technology, culture and politics evolve, we’re fa... Read More

Catalan Christmas Vs British C

All countries are proud of their quirky traditions and this is no more evident than . In South Africa they eat deep-fri... Read More

9 Ideas To Kickstart Your Read

You’ve heard about the four skills: reading, writing, and . Some might be more important to you than others. Although... Read More

How to Write the Perfect Busin

Business is all about communication. Whether it’s colleagues, clients or suppliers, we spend a big chunk of our workin... Read More

10 Phrasal Verbs You Should Le

Why are phrasal verbs so frustrating? It’s like they’ve been sent from the devil to destroy the morale of English la... Read More

How to Ace the Cambridge Speak

Exams are terrifying! The big day is here and after all that studying and hard work, it’s finally time to show what y... Read More

7 Podcasts To Improve Your Lis

Speaking in a foreign language is hard work. Language learners have to think about pronunciation, grammar and vocabulary... Read More

IELTS: Your Ticket to the Worl

Have you ever thought about dropping everything to go travelling around the world? Today, more and more people are quit... Read More

6 Language Hacks to Learn Engl

It’s October and you’ve just signed up for an English course. Maybe you want to pass an official exam. Maybe you nee... Read More

5 Reasons to Learn English in

Learning English is more fun when you do it in a fantastic location like Barcelona. Find out why we think this is the pe... Read More

FAQ Cambridge courses and Exam

Is it better to do the paper-based or the computer-based exam? We recommend the computer-based exam to our stud... Read More

Cambridge English Exams or IEL

What exactly is the difference between an IELTS exam and a Cambridge English exam such as the First (FCE) or Advanced (C... Read More

Oxford House Language School C/Diputación 279, Bajos (entre Pau Claris y Paseo de Gracia). 08007 - Barcelona (Eixample) Tel: 93 174 00 62 | Fax: 93 488 14 05 [email protected]

Oxford TEFL Barcelona Oxford House Prague Oxford TEFL Jobs

Legal Notice – Cookie Policy Ethical channel

- Remember Me

Privacy Overview

- B1 Preliminary (PET)

- B2 First (FCE)

- C1 Advanced (CAE)

- C2 Proficient (CPE)

Not a member yet?

- Part 1 0 / 30

- Part 5 0 / 25

- Part 6 0 / 25

- Part 7 0 / 20

- Part 2 0 / 30

- Part 3 0 / 30

- Part 4 0 / 25

- Part 1 NEW 0 / 16

- Part 2 NEW 0 / 16

- Part 3 NEW 0 / 16

- Part 4 NEW 0 / 16

- Part 1 0 / 25

- Part 2 NEW 0 / 29

- Part 1 0 / 10

- Part 2 0 / 10

- Part 3 0 / 10

Get unlimited access from as little as 2.60 € / per month. *One-time payment, no subscription.

- New account

Login into your account...

Not a memeber yet? Create an account.

Lost your password? Please enter your email address. You will receive mail with link to set new password.

Back to login

- Sobre nosotros

- Cambridge Methodology

- Online English level test for Cambridge

- Curso Intensivo Cambridge Online

- Curso Online Preparación Cambridge

- Improve your listening skills

- PET Preliminary – B1

- FCE First – B2

- CAE Advanced – C1

- CPE Proficiency – C2

- Speaking Practice for Cambridge

- C1 Advanced

- C2 Proficiency

- Aprende inglés gratis

- Our podcast

- Clases de conversación

- Inglés de negocios

- TEFL ONLINE Teacher Training

C2 – Your Writing Guide For The Proficiency Essay

Writing an essay in part 1 of the Proficiency C2 exam can sometimes a bit confusing. In paper 2 you will be assessed on your skill to draft coherent and cohesive texts.

QUICK INFO ABOUT PAPER 2 PART 1:

- Time: 1 hour 30 mins

- Number of exercises: 2

- Part 1 (Essay) is mandatory

- Part 2 you can choose from 4 options

- Assessment: Organisations, Content, Communicative Achievement and Language

- Marks: 20 x 2

In this post we will just focus on Part 1, writing the essay for proficiency.

PART 1 ESSAY

You will be asked to summarise key points in two short text and giving opinions on what is stated in both texts.

IT’S A COMPULSORY TASK YOU MUST DO IT!

CONTENT THAT MUST BE INCLUDED:

You must make sure that you identify and summarise all the key points/opinions in the two texts (two for each text). Don’t forget you also need to give your own opinions on what is stated in the two texts. As the opinions given in the texts are closely related to each other, you will not need to use a lot of words to summarise them – try to do this briefly, while making sure you have not left out a key point. When you give your own opinions, you can agree or disagree with what is stated in the texts.

COMMUNICATIVE ACHIEVEMENT

Your essay should be suitably neutral or fairly formal in register but it does not have to be extremely formal. In it, you need to demonstrate that you have fully understood the main points, by summarising them in your own words, not copying large parts from the texts. The opinions that you give must be closely related to those main points so that your essay is both informative and makes clear sense as a whole.

ORGANIZATION

Make sure that your essay flows well and logically and is divided appropriately into paragraphs. Make sure that there is a clear connection between your opinions and the content of the two texts, and that these features are linked using appropriate linking words and phrases, both between sentences and between paragraphs.

The language that you use needs to be both accurate and not simple/basic. You need to demonstrate that you have a high level of English by using a range of grammatical structures and appropriate vocabulary correctly. Don’t use only simple words and structures throughout your answer. Try to think of ones that show a more advanced level, without making sentences too complicated for the reader to understand. It is advisable to check very carefully for accuracy when you have completed your answer. Also make sure that everything you have written makes clear sense.

THINGS TO KEEP IN MIND

- The content of your essay does not have to follow any particular order.

- Summarise the main points of the text and then give your own opinions.

- Give your opinion on each point from the text as you summarise it.

- You can summarise the points in a different order from how they appear in the text.

- You must include your own opinions but you can put them anywhere in the essay as long as they connect closely with the points made in the texts.

Download our C2 Essay guide and practise with the full sample and correction we have included to writing an essay for the proficiency exam.

If you need any extra practise for the writing part don’t forget to check out our online course to pass the writing paper of the C2 Proficiency.

Deja una respuesta Cancelar la respuesta

Lo siento, debes estar conectado para publicar un comentario.

CONTÁCTANOS

- Paseo de la Igualdad, 4

- +34 648510688

- [email protected]

Política de privacidad y cookies

NUESTROS CURSOS

Este sitio web utiliza cookies para que usted tenga la mejor experiencia de usuario. Si continúa navegando está dando su consentimiento para la aceptación de las mencionadas cookies y la aceptación de nuestra política de cookies , pinche el enlace para mayor información. plugin cookies

- Skip to Content

- Current Students

- Prospective Students

- Business Community

- Faculty & Staff

Writing and Learning

Connect. collaborate. achieve..

- Early Assessment Program

- Written Communication Placement

- Math Placement

- Academic Coaching

- Supplemental Instruction

- Study Sessions

- Study Strategies Library

- Additional Campus Resources

- GWR-Certified Courses

- GWR Portfolio

- Info for Transfer Students

- Info for Blended Students

Writing Proficiency Exam Scoring

In general, keep in mind the following three things:

- A well-organized essay has clarity both at the paragraph and essay level. Ideas flow logically through the essay and connections between ideas are made for the reader.

- A well-developed essay has appropriate examples which support, amplify and clarify points made. Ideas are explored rather than repeated.

- A well-expressed essay has not only sentence control and sentence variety but adequate control of grammar, punctuation, spelling and vocabulary.

Scoring Criteria

The exams are read holistically: the score is based on the total impression the essay conveys. Each paper is scored on four areas: comprehension, organization, development and expression.

Two faculty readers score your test on a scale from six (highest) to one (lowest). These scores are then combined. A total score of 8 or more reflects the two readers' agreement that the essay is passing. A score of 6 or less reflects the readers' decision that an essay does not pass. If the test has a pass-fail split (a 4 and a 3), the exam is reviewed carefully by a third reader, and his or her decision determines the final passing or failing score.

6—Exemplary Paper

- Comprehension: Demonstrates a thorough understanding of the article in developing an insightful response.

- Organization: Answers all parts of the question thoroughly; demonstrates strong essay and paragraph organization.

- Development: Strongly develops the topic through specific and appropriate detail; logical, intelligent, and thoughtful; may be creative or imaginative.

- Expression: Exhibits proficient sentence structure and usage but may have a few minor slips (e.g. an occasional misused or misspelled word, or comma fault); may show stylistic flair.

5—Proficient Paper

- Comprehension: Demonstrates a sound understanding of the article in developing a well-reasoned response.

- Organization: Displays effective paragraph and essay organization and answers all parts of the question.

- Development: Skillfully and logically employs specific and appropriate details but may lack the level of insight or intelligence found in an exemplary paper.

- Expression: Structures sentences effectively but may lack stylistic flair; keeps diction appropriate but may waver in tone; maintains sound grammar though may err occasionally.

4—Acceptable Paper

- Comprehension: Demonstrates (sometimes by implication) a generally accurate understanding of the article in developing a sensible response.

- Organization: Shows adequate paragraphing and essay organization but may give disproportionate attention to some parts of the question.

- Development: Shows adequate logical development of the topic but may not be as fully developed as a superior essay or may respond in a way which is somewhat simplistic or repetitive.

- Expression: Shows adequate command of sentence structure, using appropriate diction but may contain some minor problems in grammar, punctuation, or usage (problems which might annoy a reader but will not lead to confusion or misunderstanding).

3—Failing Paper

- Comprehension: Demonstrates some understanding of the article but may misconstrue parts of it or make limited use of it in developing a weak response.

- Organization: Does not address major aspects of the topic; presents a predominantly narrative response; is deficient in organization at the essay or paragraph level; lacks focus or wanders from the controlling idea.

- Development: Consistently generalizes without adequate support; presents conclusions which do not logically follow from the premises or the evidence or consistently repeats rather than explores ideas.

- Expression: Shows deficient sentence structure; uses a primer (grade school) style, or contains errors in mechanics (including spelling) which are serious or frequent enough to affect understanding.

2—Seriously Flawed Paper

- Demonstrates poor understanding of the main points of the article, does not use the article appropriately in developing a response, or may not use the article at all.

- Shows serious flaws in more than one important area of writing (organization, development, or expression).

- Sentence level error is so severe and pervasive that other strengths ofthe paper become obscured. Clarity may exist only on the sentence level .

1—Ineffectual Paper

- Demonstrates little or no ability to understand the article or to use it in developing a response.

- Shows virtually no ability to handle the topic.

- Reveals inability to handle the basic elements of prose.

Related Content

Our offices have temporarily relocated as a result of the Library construction project. Come visit us in our new space in the Graphic Arts Building (26), Room 110A . We look forward to supporting your learning! Connect. Collaborate. Achieve.

Academic Preparation and Transitions

The Academic Preparation and Transitions Department plays an integral role in help incoming first-year students prepare for a successful college experience through the Early Assessment Program and the Supportive Pathways for First-Year Students program. More information is available on the Academic Preparation and Transitions webpage .

Learning Support Programs

The Learning Support Programs department offers a comprehensive menu of programs and resources designed to help you navigate course expectations and achieve your learning goals: free tutoring for subjects across the curriculum, peer-led supplemental workshops and study sessions provide support for STEM-specific courses, and an online study strategies library. More information is available on the Learning Support Programs webpage.

Graduation Writing Requirement

All undergraduate students who are seeking a Cal Poly degree must fulfill the GWR before a diploma can be awarded. Students must have upp division standing (completed 90 units) before they can attempt to fulfill the requirement and should do so before the senior year. The two pathways to GWR completion are 1) in an approved upper-division course and 2) via the GWR Portfolio. More information is available on the GWR webpage .

Support Learn by Doing

Cambridge C2 Proficiency (CPE): How to Write a Report

- Mandatory task : no

- Word count : 280-320

- Main characteristics : descriptive, comparative, analytical, impersonal, persuasive

- Register : normally formal but depends on the task

- Structure : introduction, main paragraphs, conclusion (sub-heading for each paragraph)

Introduction

A report is written for a specified audience. This may be a superior, for example, a boss at work, or members of a peer group, colleagues or fellow class members. The question identifies the subject of the report and specifies the areas to be covered. The content of a report is mainly factual and draws on the prompt material, but there will be scope for candidates to make use of their own ideas and experience. Source: Cambridge English Assessment: C2 Proficiency Handbook for teachers

Reports in Cambridge C2 Proficiency are, unlike essays , not mandatory in the writing test. Instead of a report candidates might opt to write an article , a review or a letter .

Reports are very schematic

While some of the writing tasks in C2 Proficiency are quite free and open in terms of their paragraph structure and layout, reports follow a pretty rigid form, which makes it fairly easy to write them. With their sub-headings for each section and similar requirements in every task, candidates get a good grasp of report writing quite quickly.

This article shows you exactly how you can navigate those waters and how to score high marks with ease, so let’s get into it.

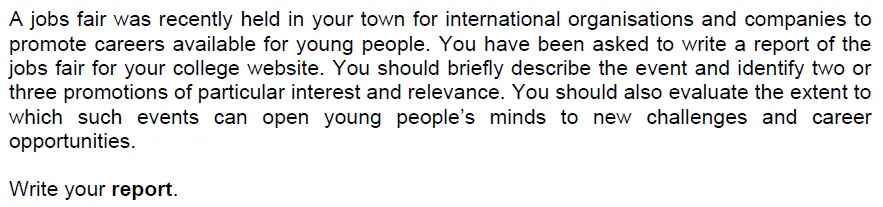

What a typical report task looks like

A report task in C2 Proficiency is usually very specific regarding the topic and the more detailed points you need to talk about in your text as well as the target reader you are writing for.

The three things I’ve mentioned above should always be the first things to find out when you analyse a writing task:

- the topic of the task

- the detailed points you have to include

- the target reader

The topic of this specific task is a jobs fair for young people . A more close-up look reveals that we need to describe the event a little bit in general as well as two or three promotions in more detail . Thirdly, we evaluate if and how much a fair like this can open young people’s minds to career opportunities .

Last but not least, we are writing the report for our college website meaning that teachers, students and parents are going to read it. Therefore, the style of language doesn’t need to be super formal, but I would also not write in an informal style. Neutral seems to be the right choice so contractions (I’m, don’t, etc.) as well as some phrasal verbs are fine, but colloquial expressions that we would use just in spoken English are taboo.

How to organise your report

The paragraph structure of a report in C2 Proficiency is fairly straightforward. I would simply start with a title and an introduction that states what the report is about (in this case, we could describe the fair in the introduction), then continue with the sections that address the main points and finish with a conclusion.

Title & introduction

Main sections.

For most reports, this structure works very well. Depending on the task, we mostly use two or three main sections and you are free to choose whatever organisational form you think makes the most sense.

Plan your report before you start writing

I can’t stretch this point enough, but I would always note down a short plan to make sure my ideas are already saved somewhere before I start writing. This reassures you whenever you don’t know how to continue and it can save you a lot of time.

The best way to go about making your plan is to decide on the paragraph structure you want to use for a particular task and then to add a few short ideas of what you definitely want to include in each section. For our example task, I came up with this:

- Title & introduction : jobs fair event summary; 10-12 July; 53 organisations; show career opportunities; specialists with valuable information

- First special organisation : English teaching jobs abroad; information about the jobs; people were happy

- Second special organisation : NGO from Peru; literacy and English classes; accommodation and food included; people had done programme before

- Conclusion : everyone happy; event broadens young people’s horizon; visitors surprised by variety of options; definitely recommend it

I’ve decided on four paragraphs as there are basically four things we need to do: introduce the event, talk about two different organisations at the fair and comment on how it opens young people’s minds.

This whole process took less than five minutes, but I know that once I start writing, I have a roadmap prepared that can help me whenever I need it. I won’t have to waste time rearranging my ideas or changing the paragraph structure because it’s all done already.

The different parts of a report

Once you have a plan, you can get started with the actual writing process. Thanks to all the information you’ve already noted down, it should all be smooth sailing, but there are, of course, several things to take note of when writing a report and we are going to look at them paragraph by paragraph.

A report in Cambridge C2 Proficiency typically has a title, which can be descriptive and doesn’t need to be anything special. For example, for our example task from earlier, we could choose a basic title like “Jobs Fair”. That’s it.

The introduction or first paragraph of your text, however, is a little bit more important. Here, you want to show what the report is going to talk about. This can be quite explicit, but you can also give a more subtle description of the subject matter.

Jobs Fair Event summary From 10-12 July, a jobs fair with 53 organisations from all over Europe was held at the college to display career opportunities for the students. The different booths were manned expertly by specialists so as to give the best information possible and to show what the future might hold for graduates of the school.

First of all, there is the title plus the first subheading (Event summary). Subheadings are an essential part of the typical layout of a report so make sure that each section gets one.

Secondly, I state what the fair was about and what purpose the different organisations came to the event for, i.e. to show graduates a variety of future job opportunities, so the reader knows what to expect from this report .

On top of that, I tried immediately to use rather impersonal language , another common feature of reports, which includes passive verb forms, generalisations (It is said that; Many people said; in general; etc.) as well as avoiding personal pronouns like I or we.

With a good introduction under our belt, we can now get into the nitty gritty of the report. The task requires us to point out a few of the organisations present at the fair and explain in a little bit more detail what they were offering.

Obviously, you need to get a little bit creative and come up with some ideas, but as the report is for the college website, I thought it would be nice to talk about some options that are connected to the English language.

Promotions to highlight While the event as a whole went remarkably well, two stands were mentioned by many to be of particular relevance. One provided insights about job opportunities abroad as an English speaker, which includes teaching the language as well as tutoring children and teenagers. There was a wide variety of employment options presented together with the expected salary, working conditions and other things to consider before taking the leap, which quite a lot of visitors commented on in a very positive way. The second organisation that was indicated to me fairly often was an NGO from Peru which runs literacy campaigns and English language courses in rural areas around the country. They were looking to attract young people to their volunteer programme that involves teaching reading and writing to primary school children from disadvantaged backgrounds. Accommodation and food are both included so participants only need to cover the cost for their flights to Peru and back. The people working at the stand had all done it themselves so the visitors at the fair were given first-hand accounts of what working for the NGO is like.

As the two paragraphs belong to the same section of the report, only one subheading is necessary, but apart from that, I really focussed on the basics of good report writing.

I described in detail what the two organisations have to offer using some appropriate vocabulary (remarkably well; particular relevance; a wide variety of employment options; salary; working conditions; NGO; literacy campaigns; disadvantaged backgrounds; first-hand accounts) as well as more impersonal and general language (mentioned by many; visitors commented on it; was indicated to me).

The conclusion is the part where finish your report and make recommendations or suggestions based on the information provided in the previous sections. Here, you can give your personal opinion to round off the text. Again, don’t forget the subheading and use appropriate language.

Benefits of such job fairs After listening to other people’s thoughts on this kind of event I’m of the opinion that job fairs like this can truly broaden the horizon of young people who might not have formed a clear idea of what they want to do after school yet. Several of my friends mentioned that they simply had not been aware of the multitude of options available to them and that they would absolutely recommend it to everyone who needs some inspiration for their future.

I refer back to the previous sections (After listening to …), then give my opinion (… I’m of the opinion …) and make a recommendation (… they would absolutely recommend it …). It is that simple.

It is not that difficult to write a report in C2 Proficiency if you know how to plan the text and what language you should include. Obviously, at this level you should be able to play with the language and adapt each report to the topic of the task, but I hope that this article has helped you get a better idea of what goes into writing this kind of text.

If you want to practise with me, I offer writing feedback as well as private classes and I would love to hear from you soon.

Lots of love,

Teacher Phill 🙂

Similar Posts

Cambridge C2 Proficiency (CPE): How to Calculate Your Score

Cambridge C2 Proficiency (CPE): How to Write a Letter

Cambridge C2 Proficiency (CPE): How Your Writing is Marked

Are native speakers better language teachers.

Reading Skills – 7 Great Tips To Improve

How To Stay Calm on Your Cambridge Exam Day

Exploring Students’ Generative AI-Assisted Writing Processes: Perceptions and Experiences from Native and Nonnative English Speakers

- Original research

- Open access

- Published: 30 May 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Chaoran Wang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4140-2757 1

505 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Generative artificial intelligence (AI) can create sophisticated textual and multimodal content readily available to students. Writing intensive courses and disciplines that use writing as a major form of assessment are significantly impacted by advancements in generative AI, as the technology has the potential to revolutionize how students write and how they perceive writing as a fundamental literacy skill. However, educators are still at the beginning stage of understanding students’ integration of generative AI in their actual writing process. This study addresses the urgent need to uncover how students engage with ChatGPT throughout different components of their writing processes and their perceptions of the opportunities and challenges of generative AI. Adopting a phenomenological research design, the study explored the writing practices of six students, including both native and nonnative English speakers, in a first-year writing class at a higher education institution in the US. Thematic analysis of students’ written products, self-reflections, and interviews suggests that students utilized ChatGPT for brainstorming and organizing ideas as well as assisting with both global (e.g., argument, structure, coherence) and local issues of writing (e.g., syntax, diction, grammar), while they also had various ethical and practical concerns about the use of ChatGPT. The study brought to front two dilemmas encountered by students in their generative AI-assisted writing: (1) the challenging balance between incorporating AI to enhance writing and maintaining their authentic voice, and (2) the dilemma of weighing the potential loss of learning experiences against the emergence of new learning opportunities accompanying AI integration. These dilemmas highlight the need to rethink learning in an increasingly AI-mediated educational context, emphasizing the importance of fostering students’ critical AI literacy to promote their authorial voice and learning in AI-human collaboration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Students’ voices on generative AI: perceptions, benefits, and challenges in higher education

Examining science education in chatgpt: an exploratory study of generative artificial intelligence.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) Student Assistants in the Classroom: Designing Chatbots to Support Student Success

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The rapid development of large language models such as ChatGPT and AI-powered writing tools has led to a blend of apprehension, anxiety, curiosity, and optimism among educators (Warner, 2022 ). While some are optimistic about the opportunities that generative AI brings to classrooms, various concerns arise especially in terms of academic dishonesty and the biases inherent in these AI tools (Glaser, 2023 ). Writing classes and disciplines that use writing as a major form of assessment, in particular, are significantly impacted. Generative AI has the potential to transform how students approach writing tasks and demonstrate learning through writing, thus impacting how they view writing as an essential literacy skill. Educators are concerned that when used improperly, the increasingly AI-mediated literacy practices may AI-nize students’ writing and thinking.

Despite the heated discussion among educators, there remains a notable gap in empirical research on the application of generative AI in writing classrooms (Yan, 2023 ) and minimal research that systematically examines students’ integration of AI in their writing processes (Barrot, 2023a ). Writing–an activity often undertaken outside the classroom walls–eludes comprehensive observation by educators, leaving a gap in instructors’ understandings of students’ AI-assisted writing practices. Furthermore, the widespread institutional skepticism and critical discourse surrounding the use of generative AI in academic writing may deter students from openly sharing their genuine opinions of and experiences with AI-assisted writing. These situations can cause disconnect between students’ real-life practices and instructors’ understandings. Thus, there is a critical need for in-depth investigation into students’ decision-making processes involved in their generative AI-assisted writing.

To fill this research gap, the current study explores nuanced ways students utilize ChatGPT, a generative AI tool, to support their academic writing in a college-level composition class in the US. Specifically, the study adopts a phenomenological design to examine how college students use ChatGPT throughout the various components of their writing processes such as brainstorming, revising, and editing. Using sense-making theory as the theoretical lens, the study also analyzes students’ perceived benefits, challenges, and considerations regarding AI-assisted academic writing. As writing is also a linguistic activity, this study includes both native and non-native speaking writers, since they may have distinct needs and perspectives on the support and challenges AI provides for writing.

2 Literature Review

2.1 ai-assisted writing.

Researchers have long been studying the utilization of AI technologies to support writing and language learning (Schulze, 2008 ). Three major technological innovations have revolutionized writing: (1) word processors, which represented the first major shift from manual to digital writing, replacing traditional typewriters and manual editing processes; (2) the Internet, which introduced web-based platforms, largely promoting the communication and interactivity of writing; and (3) natural language processing (NLP) and artificial intelligence, bringing about tools capable of real-time feedback and content and thinking assistance (Kruse et al., 2023 ). These technologies have changed writing from a traditionally manual and individual activity into a highly digital nature, radically transforming the writing processes, writers’ behaviors, and the teaching of writing. This evolution reflects a broader need towards a technologically sophisticated approach to writing instruction.

AI technologies have been used in writing instruction in various ways, ranging from assisting in the writing process to evaluating written works. One prominent application is automatic written evaluation (AWE), which comprises two main elements: a scoring engine producing automatic scores and a feedback engine delivering automated written corrective feedback (AWCF) (Koltovskaia, 2020 ). Adopting NLP to analyze language features, diagnose errors, and evaluate essays, AWE was first implemented in high-stakes testing and later adopted in writing classrooms (Link et al., 2022 ). Scholars have reported contrasting findings regarding the impact of AWE on student writing (Koltovskaia, 2020 ). Barrot ( 2023b ) finds that tools offering AWCF, such as Grammarly, improves students’ overall writing accuracy and metalinguistic awareness, as AWCF allows students to engage with self-directed learning about writing via personalized feedback. Thus the system can contribute to classroom instruction by reducing the burden on teachers and aiding students in writing, revision, and self-learning (Almusharraf & Alotaibi, 2023 ). However, scholars have also raised concerns regarding its accuracy and its potential misrepresentation of the social nature of writing (Shi & Aryadoust, 2023 ). Another AI application that has been used to assist student writing is intelligent tutoring system (ITS). Research shows that ITS could enhance students’ vocabulary and grammar development, offer immediate sentence- and paragraph-level suggestions, and provide insights into students’ writing behaviors (Jeon, 2021 ; Pandarova et al., 2019 ). Scholars also investigate chatbots as writing partners for scaffolding students’ argumentative writing (Guo et al., 2022 ; Lin & Chang, 2020 ) and incorporating Google’s neural machine translation system in second language (L2) writing (Cancino & Panes, 2021 ; Tsai, 2019 ).

Research suggests that adopting AI in literacy and language education has advantages such as supporting personalized learning experiences, providing differentiated and immediate feedback (Huang et al., 2022 ; Bahari, 2021 ), and reducing students’ cognitive barriers (Gayed et al., 2022 ). Researchers also note challenges such as the varied level of technological readiness among teachers and students as well as concerns regarding accuracy, biases, accountability, transparency, and ethics (e.g., Kohnke et al., 2023 ; Memarian & Doleck, 2023 ; Ranalli, 2021 ).

2.2 Integrating Generative AI into Writing

With sophisticated and multilingual language generation capabilities, the latest advancements of generative AI and large language models, such as ChatGPT, unlock new possibilities and challenges. Scholars have discussed how generative AI can be used in writing classrooms. Tseng and Warschauer ( 2023 ) point out that ChatGPT and AI-writing tools may rob language learners of essential learning experiences; however, if banning them, students will also lose essential opportunities to learn how to use AI in supporting their learning and their future work. They suggest that educators should not try to “beat” but rather “join” and “partner with” AI (p. 1). Barrot ( 2023a ) and Su et al. ( 2023 ) both review ChatGPT’s benefits and challenges for writing, pointing out that ChatGPT can offer a wide range of context-specific writing assistance such as idea generation, outlining, content improvement, organization, editing, proofreading, and post-writing reflection. Similar to Tseng and Warschauer ( 2023 ), Barrot ( 2023a ) is also concerned about students’ learning loss due to their use of generative AI in writing and their over-reliance on AI. Moreover, Su et al. ( 2023 ) specifically raise concerns about the issues of authorship and plagiarism, as well as ChatGPT’s shortcomings in logical reasoning and information accuracy.

Among the existing empirical research, studies have explored the quality of generative AI’s feedback on student essays in comparison to human feedback. Steiss et al. ( 2024 ) analyzed 400 feedback instances—half generated by human raters and half by ChatGPT—on the same essays. The findings showed that human raters provided higher-quality feedback in terms of clarity, accuracy, supportive tone, and emphasis on critical aspects for improvement. In contrast, AI feedback shone in delivering criteria-based evaluations. The study generated important implications for balancing the strengths and limitations of ChatGPT and human feedback for assessing student essays. Other research also examined the role of generative AI tools in L1 multimodal writing instruction (Tan et al., 2024 ), L1 student writers’ perceptions of ChatGPT as writing partner and AI ethics in college composition classes (Vetter et al., 2024 ), and the collaborative experience of writing instructors and students in integrating generative AI into writing (Bedington et al., 2024 ).