Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

How to Use Quotation Marks

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Using Quotation Marks

The primary function of quotation marks is to set off and represent exact language (either spoken or written) that has come from somebody else. The quotation mark is also used to designate speech acts in fiction and sometimes poetry. Since you will most often use them when working with outside sources, successful use of quotation marks is a practical defense against accidental plagiarism and an excellent practice in academic honesty. The following rules of quotation mark use are the standard in the United States, although it may be of interest that usage rules for this punctuation do vary in other countries.

The following covers the basic use of quotation marks. For details and exceptions consult the separate sections of this guide.

Direct Quotations

Direct quotations involve incorporating another person's exact words into your own writing.

- Quotation marks always come in pairs. Do not open a quotation and fail to close it at the end of the quoted material.

Mr. Johnson, who was working in his field that morning, said, "The alien spaceship appeared right before my own two eyes."

Although Mr. Johnson has seen odd happenings on the farm, he stated that the spaceship "certainly takes the cake" when it comes to unexplainable activity.

"I didn't see an actual alien being," Mr. Johnson said, "but I sure wish I had."

When quoting text with a spelling or grammar error, you should transcribe the error exactly in your own text. However, also insert the term sic in italics directly after the mistake, and enclose it in brackets. Sic is from the Latin, and translates to "thus," "so," or "just as that." The word tells the reader that your quote is an exact reproduction of what you found, and the error is not your own.

Mr. Johnson says of the experience, "It's made me reconsider the existence of extraterestials [ sic ]."

- Quotations are most effective if you use them sparingly and keep them relatively short. Too many quotations in a research paper will get you accused of not producing original thought or material (they may also bore a reader who wants to know primarily what YOU have to say on the subject).

Indirect Quotations

Indirect quotations are not exact wordings but rather rephrasings or summaries of another person's words. In this case, it is not necessary to use quotation marks. However, indirect quotations still require proper citations, and you will be committing plagiarism if you fail to do so.

Many writers struggle with when to use direct quotations versus indirect quotations. Use the following tips to guide you in your choice.

Use direct quotations when the source material uses language that is particularly striking or notable. Do not rob such language of its power by altering it.

The above should never stand in for:

Use an indirect quotation (or paraphrase) when you merely need to summarize key incidents or details of the text.

Use direct quotations when the author you are quoting has coined a term unique to her or his research and relevant within your own paper.

When to use direct quotes versus indirect quotes is ultimately a choice you'll learn a feeling for with experience. However, always try to have a sense for why you've chosen your quote. In other words, never put quotes in your paper simply because your teacher says, "You must use quotes."

The Editor’s Manual

Free learning resource on English grammar, punctuation, usage, and style.

- Punctuation |

- Quotation marks

Four Uses of Quotation Marks

Place quotation marks (or inverted commas) around direct speech or a quotation. Quotes may also enclose a word or a phrase used ironically or in some special sense other than its usual meaning. Also use quotes to enclose words used as themselves instead of functionally in a sentence. Quotation marks set off titles of shorter works that appear within a larger work (e.g., the title of a chapter, article, or poem).

Direct speech and quoted text

Use quotation marks (also known as inverted commas or quotes) to enclose the exact words of another person’s speech or text . Quotation marks always appear in pairs: use an opening quotation mark to indicate the start of quoted text and a closing quotation mark to indicate its end.

- Maya said, “We need more time.”

- Dash replied, “You always have a choice.”

- Nemo predicts that the travel sector will grow by 20% this year. “We are already seeing overcrowded airports and full occupancy at hotels.”

- “Where were you?” “At the park.”

- “Stop!” he cried.

- “I’m going to bake a cake,” said Lulu.

- “Are you still there?” she typed.

- She felt “a sudden, sharp pain” in her side.

- A witness described it as “the loudest bang” and said she thought “the world was ending.”

Prefer to use smart or curly quotes over straight quotes in formal writing. Smart quotes are directional: the opening and closing quotation marks look different from each other, curving inward towards the quotation instead of being identical and unidirectional (“. . . ” instead of ". . . "). The HTML character codes for smart quotes are “ and ” with Unicode values “ and ” . Microsoft Word has a checkbox you can select to make sure your documents display smart instead of straight quotes.

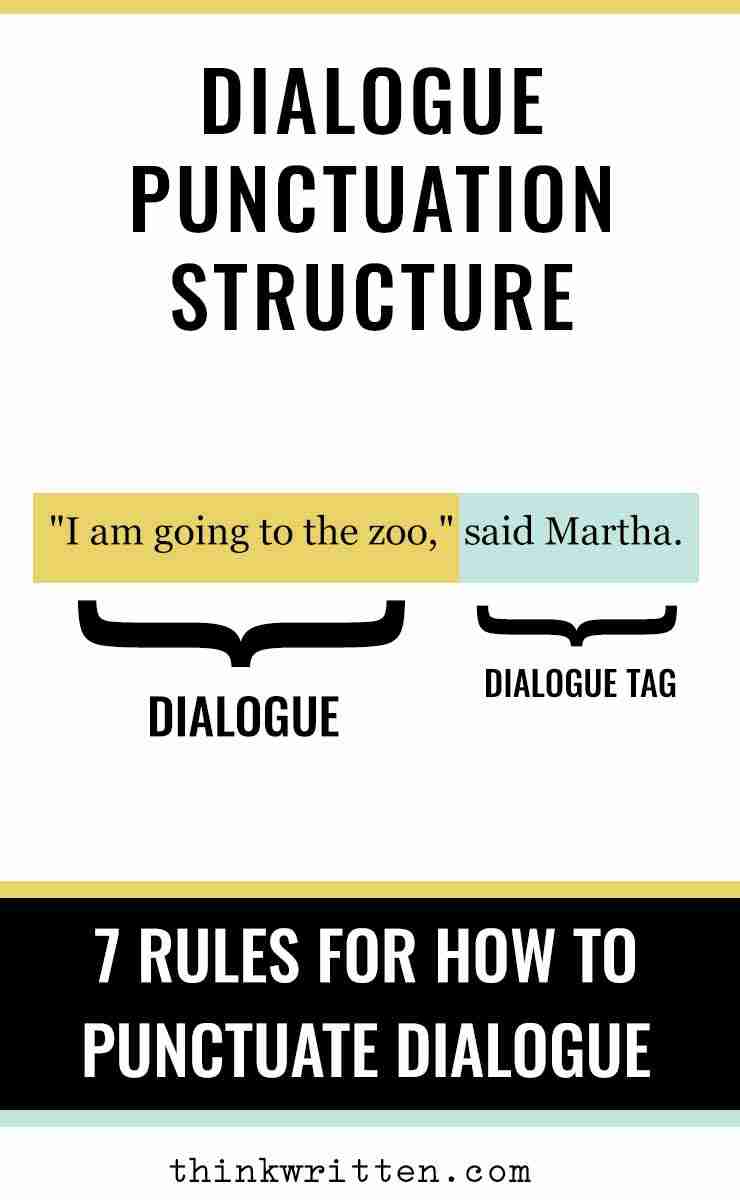

Commas surrounding a quotation

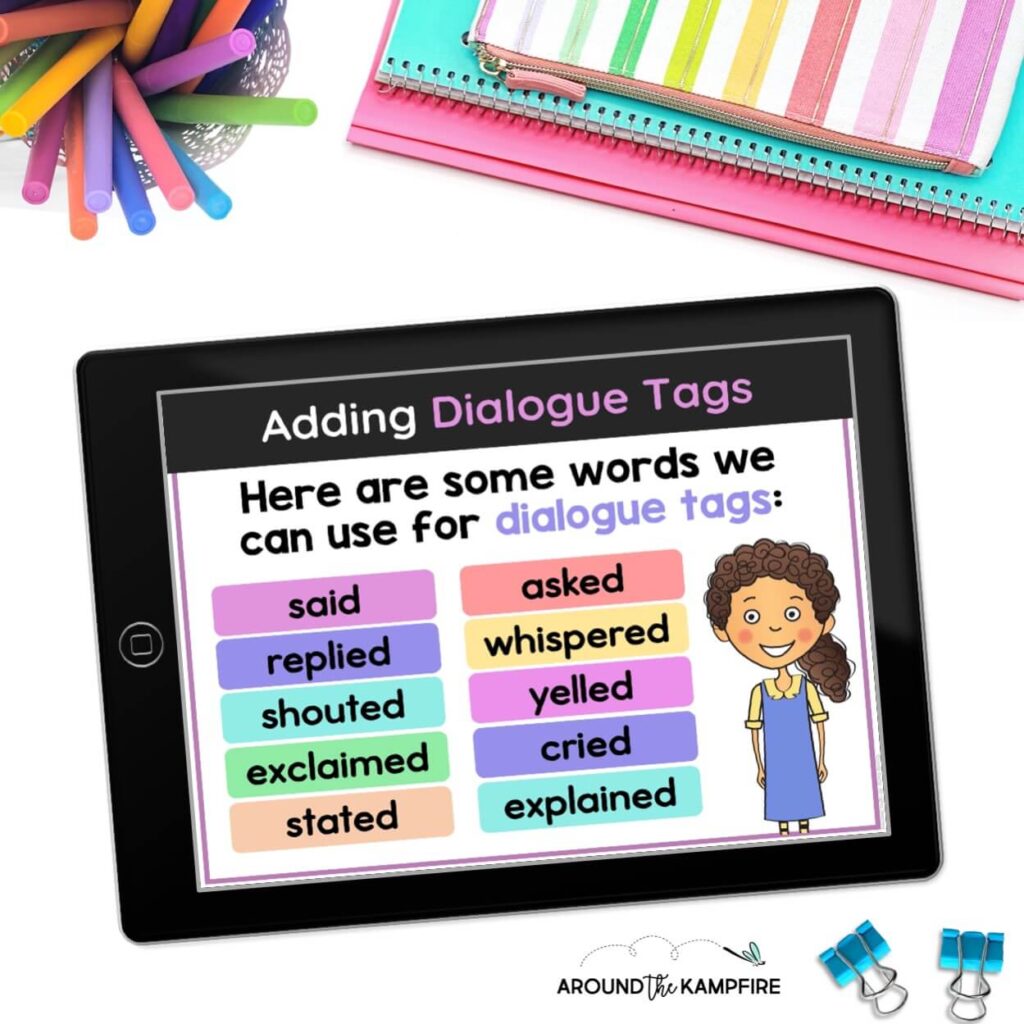

Use a comma after verbs like said , wrote , replied , and asked when they introduce a quote that is a complete sentence .

- Maya said, “I hope the train is on time.”

- Farley asked, “Do you sell pumpkins?”

- In a diary entry she wrote, “I now know why I’m here.”

- Lulu replied, “None of them has the answer.”

The explanatory text may appear after the quote, in which case the quote ends in a comma .

- “I hope the train is on time,” said Maya.

- “I now know why I’m here,” she wrote.

- “ None of them has the answer,” replied Lulu.

If the quote ends in a question mark or exclamation point , don’t use a comma.

- “Where have all the bees gone?” he asked.

- “Run!” she cried.

- “And then he was gone!” she wrote.

- He asked, “Where are all the butterflies?”

If the explanatory text divides the quote into two parts, use commas both before and after.

- “None of them,” she said, “has the answer.”

Don’t use commas if the quote appears in the flow of the surrounding sentence and cannot stand by itself as a complete sentence.

- They call it “the song of the birds.”

- She said it sent “a shiver right through her toes” to see him on TV.

Running quotations

Running quotations are those that span paragraphs. If a quote starts in one paragraph and continues into another, place an opening quotation mark at the start of each paragraph but a closing quotation mark only at the end of the final one. This indicates to the reader that it’s the same speaker or writer across paragraphs, whose quotation ends only at the end of the final paragraph.

- Dash said: “Paragraph 1. “Paragraph 2. “Paragraph 3. “Final paragraph.”

- She replied, “I don’t have any money. “I never have any money . Any money I have, I spend it. You know that.”

Scare quotes

Enclose a word or a phrase in quotation marks or “ scare quotes ” to indicate that it is being used ironically or in a nonstandard way (conveying a meaning other than the usual).

- She said she was going to “call the doctor.”

- That was some “meeting.” All he did was yell.

- She said she likes “classical” literature and then quoted Dan Brown.

Be careful not to overuse scare quotes. In particular, don’t enclose a word or a phrase in quotes simply to emphasize it (use formatting options like italic instead).

Don’t enclose standard idioms or slang in scare quotes.

- Incorrect: It’s time we gave him “a taste of his own medicine.” “A taste of someone’s own medicine” is a standard idiom in English with a defined meaning. Correct: It’s time we gave him a taste of his own medicine.

Words as words

To refer to a word or a term as itself in a sentence rather than using it functionally, you can enclose it in quotation marks.

- “I” and “ me ” are both pronouns. The words “I” and “me” are not used functionally as pronouns , but are referred to as themselves, which is why they are enclosed in quotation marks.

- I used to think the word “bell” was onomatopoeic.

- How do you spell “onomatopoeic”?

Italics are preferred over quotation marks in formal writing to refer to a term (a letter, word, or phrase ) used as itself in a sentence. Use quotes instead if doing so helps improve readability or clarity, or in media where italics are not easily available (chat messages, posts on social media such as tweets).

- There’s no “I” in “team.” There’s no “J” either.

- Sartre speaks of en soi , or “being-in-itself,” which is the self-contained existence of objects.

Titles of works

Titles of larger works are generally italicized (such as names of books, movies, journals, and magazines), but titles of shorter works that appear within a larger work are enclosed in quotation marks. For example, the title of a short story that appears within an anthology is enclosed in quotes, while the title of the larger anthology itself is italicized. Similarly, the title of a song is enclosed in quotation marks, while the name of a music album is italicized. Titles of articles are enclosed in quotation marks, while names of periodicals are italicized.

- Her short story, “Cat Person,” was published in the New Yorker in 2017.

- “Fade into You” is probably their most famous song.

- Refer to Chapter 4, “Why Humans Talk.”

Titles of larger works (like names of books and movies) may also be enclosed in quotation marks in media where the use of italics is uncommon or impossible (e.g., chat messages, social media).

- Did you know “The Silence” is a remake of a 1963 film?

- One of his books that affected me deeply as a child is “Insomnia.”

Capitalization

Capitalize a quote that is a full sentence introduced by verbs like said and wrote or phrases like as she said or according to .

- As Dash once said, “There is no life without hope.”

- She wrote, “There is no life without hope. To live is to hope.”

- According to Dash, “There is no life without hope.”

- Minerva replied, “My childhood was a time full of hope.”

Don’t capitalize a quotation that appears within the flow of a larger sentence.

- She once said that “ there is no life without hope.”

- She described her childhood as “ a time full of hope.”

Don’t capitalize the second part of a quote that is interrupted by an explanatory phrase.

- “My childhood,” she said, “ was a time full of hope.”

A quotation of one or more full sentences may also be introduced using a colon in formal text. It is then capitalized .

- Dash said: “There is no life without hope. To live is to hope.”

Quotes within quotes: Single and double quotes

Use single within double quotes to show quotes within quotes —to enclose in quotes a word or a phrase that appears within material already enclosed in quotation marks.

- Leonard’s latest article, “Bacteria and Fungi Can ‘Walk’ across the Surface of Our Teeth,” may make you want to rinse your mouth out every five minutes.

In British academic and creative writing, single quotes are the default , with double quotes reserved for quotes within quotes, as recommended by the New Oxford Style Manual (the style manual of the Oxford University Press). In British news copy however, double quotes are generally the default, as in American style.

Most U.S. style guides , like the Chicago Manual of Style , APA Publication Manual , AP Stylebook , and MLA Handbook , recommend enclosing quotations in double quotes, with single quotation marks reserved for quotes within quotes.

Periods and commas with quotation marks

In American writing, periods and commas always appear inside closing quotation marks .

- “My mother,” she said, “could get quite angry.”

- Use “I,” not “me,” as the subject of a sentence.

- We decimate our forests, pollute our waters, poison our air, and call it “progress.”

- I’m sure Poco, the “expert,” will be happy to advise us.

In British writing, a period or a comma precedes a closing quotation mark only if it part of the quoted text. If it is meant to punctuate the surrounding sentence instead, the comma appears after the closing quotation mark.

- ‘My mother’, she said, ‘could get quite angry.’ The commas punctuate the larger sentence and appear outside quotes. The period ends the quotation and therefore appears inside. Don’t use another period to end the sentence. Also note the use of single instead of double quotation marks in British style.

- Use ‘I’, not ‘me’, as the subject of a sentence.

- We cut down trees, pollute our waters, poison our air, and call it ‘progress’.

- I’m sure Poco, the ‘expert’, will be happy to advise us.

Other punctuation with quotation marks

Other punctuation marks, like question marks and exclamation points, precede a closing quotation mark if they belong to the quoted content. If they belong to the surrounding sentence, they appear after the closing quotation mark.

- She asked, “Where were you?”

- He cried, “It can’t be!”

- Did he just say, “I don’t want your money”?

- What do you mean by the word “truth”?

- She calls it “truth”!

Share this article

Use a comma after verbs like said when they introduce a quote that is a complete sentence.

Don’t use a comma before quoted text that is not a full sentence but appears in the flow of a larger sentence.

Capitalize a quote that is a complete sentence.

Don’t unnecessarily capitalize quoted text that is not a full sentence.

Enclose titles of shorter works (like poems) in quotation marks.

In U.S. style, double quotation marks are the primary choice, with single quotation reserved for quotes within quotes.

Periods always go inside closing quotation marks in American writing.

Using Quotation Marks

The rules for using quotation marks.

Table of Contents

Four Ways to Use Quotation Marks

Using quotation marks explained in detail, (1) using quotation marks for previously spoken or written words, (2) using quotation marks for the names of ships, books, and plays, (3) using quotation marks to signify so-called or alleged, (4) using quotation marks to show a word refers to the word itself, why quotation marks are important.

(1) To identify previously spoken or written words.

(2) To highlight the name of things like ships, books, and plays.

(3) To signify so-called or alleged.

(4) To show that a word refers to the word itself not the word's meaning.

(Issue 1) Being inconsistent with single or double quotation marks.

(Issue 2) Using quotation marks with reported speech

(issue 3) being unsure whether to use a comma or a colon before a quotation..

(Rule 1) Use a colon if the introduction is an independent clause.

- New York gang members all advise the following: "Don't run from fat cops. They shoot earlier."

(Rule 2) You can use a colon if the quotation is a complete sentence.

- The orders state: "In case of fire, exit the building before tweeting about it."

(Rule 3) Use a comma if the introduction is not an independent clause.

- Before each shot, the keeper said aloud, "bum, belly, beak, bang."

- Peering over his glasses, he said, "Never test the depth of a river with both feet."

(Rule 4) You can only use a comma after a quotation.

- "Always give 100%, unless you're donating blood", he would always say.

(Rule 5) Don't use any punctuation if the quotation is not introduced.

- I believe there really is, "no place like home."

- I would hate to see the worst if this is the, "best skiing resort in France".

(Issue 4) Being unsure whether to place punctuation inside or outside the quotation.

| Punctuation | UK Convention | US Convention |

|---|---|---|

. and, | Place your full stops and commas outside (unless they appear in the original). (The full stop is in the original.) | Place your full stops and commas inside. Obviously, don't put your comma inside if it precedes the quotation (like the one after Churchill). |

! and? | Place exclamation marks and question marks inside or outside according to logic. ("I love you" is not a question, but the whole sentence is.) (The whole sentence is not a question, but the quotation is.) The second example is not a question, but it ends in a question mark. For neatness, it's acceptable to use just one end mark. Under US convention, you should use only one end mark. Under the UK convention and if you're a real logic freak, you can use two end marks. | |

| ? ,! , and. | Don't double up with end marks. But, if you must, you can. (This is unwieldy but acceptable. The sentence is a question, and the quotation is a question.) (This is unwieldy but acceptable.) | Don't double up with end marks. (This is too unwieldy for US tastes.) |

| : and; | Place colons and semicolons outside the quotation. one mancipated to a master, not a free-man and a dependant. Johnson offered a fourth definition, "the lowest form of life"; however, he stated that this definition was only used proverbially. | |

| More on ? ,! , and. | Don't end a quotation with a period (full stop) when the quotation doesn't end the whole sentence. There's more leniency with question and exclamation marks, but try to avoid that situation too. | |

(Issue 5) Using quotation marks for emphasis.

- Nest single quotation marks within doubles.

- The instructions say: "Shout 'Yahtzee' loudly."

- Don't put reported speech in quotation marks.

Two Points about Editing Quotations

This page was written by Craig Shrives .

You might also like...

Was something wrong with this page?

Use #gm to find us quicker .

Create a QR code for this, or any, page.

mailing list

grammar forum

teachers' zone

Confirmatory test.

This test is printable and sendable

expand to full page

show as slides

download as .doc

print as handout

send as homework

display QR code

The Editor's Blog

Write well. Write often. Edit wisely.

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 13 | 15 | 16 | 17 | ||

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 22 | 23 | 24 | |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 30 | 31 | ||

- Copyright, Print, Citation

- Full Archives

- Writing Essentials

- The Magic of Fiction

- (Even More) Punctuation in Dialogue (PDF)

- Books by Beth Hill

- NaNo Support 2016

- Writing Prompts

- NaNo Write-in

- NaNo Support 2017

- A Reader Asks… (32)

- A Writer's Life (62)

- Announcements (9)

- Beginning Writers (44)

- Beyond the Basics (31)

- Beyond the Writing (2)

- Contests (4)

- Craft & Style (171)

- Definitions (15)

- Editing Tips (18)

- For Editors (11)

- Genre Requirements (1)

- Grammar & Punctuation (61)

- How to (19)

- Launch Week (13)

- Member Events (1)

- Recommendations (14)

- Self-Publishing (5)

- Site Business (4)

- Story Structure (1)

- Writing Challenge (6)

- Writing Essentials (7)

- Writing Tips (120)

- February 2020

- December 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

A Novel Edit

Beth's Books

Reference Books

This Blog's Purpose

Marking Text—Choosing Between Italics and Quotation Marks

An error in the use of italics or quotation marks—using one rather than the other or not using either when their use is required—is not likely a problem that will have an agent or publisher turning down your manuscript, especially if your manuscript isn’t bulging with other errors. Yet knowing when to use both italics and quotation marks is useful and important for writers. The cleaner the manuscript, the fewer problems it will be perceived to have. And when rules are followed, the manuscript will have consistency; if you don’t know the rules, it’s likely that you won’t make the same choices consistently throughout a story. And if you self-publish, when you’re the one doing the editing, you’ll definitely want to know how and when to use both italics and quotation marks and know how to choose between them.

To start off, I will point out that there is no need to underline anything in a novel manuscript . Writers used to underline text where they intended italics, but because it’s now so easy to see and find and identify italics, underlining is no longer necessary, not for fiction manuscripts.

Note: Underlining may be required for school or college writing projects or other purposes. I’m strictly addressing fiction manuscripts here.

Without underlining, the choices are italics, quotation marks, and unmarked or plain text.

Let’s start with the last option—plain text—first.

________________________

Not all text that seems to require italics or quotation marks actually does. Most words in your manuscript will be roman text—unchanged by italics—and, apart from dialogue, will not be enclosed by quotation marks. Yet sometimes writers are confused about italics and quotation marks, especially when dealing with named entities. A quick rule: Simple names need only be capitalized—no other marks are necessary.

This is one writing question that’s easy to overthink once you begin editing, but a name usually only needs to be capitalized; it typically doesn’t require italics or quotation marks. (There are exceptions, of course.)

Capitalize names of people, places, and things . This means that Bob, Mr. Smith, Grandma Elliott, and Fido are capitalized but not italicized or put in quotation marks. The same is true for Disney World, the Grand Canyon, Edie’s Bistro, and the World Series. When a person’s title is paired with a name—Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Reverend Thomas—both name and title are capitalized. But when a title is not used as a name—the president is young, the pastor can sing—no capitalization is required.

Nouns are typically the words that you’ll capitalize, but not all nouns are capitalized. Capitalize named nouns . So Fido is capitalized, but dog is not; Aunt Margaret (used as a name) is capitalized, but my aunt is not; my aunt Margaret gets a mix of capitalization.

Brand names and trademarks are typically capitalized, but some have unusual capitalizations (iPad, eBay, TaylorMade, adidas). Refer to dictionaries and to company guidelines or Internet sources for correct capitalization and spelling. Note that home pages of websites may feature decorative text; look at pages with corporate details for correct information.

You may make a style decision and capitalize such words according to established rules, and that would be a valid decision. Yet a name is a name, and spelling or capitalizing it the way its creators intended may well be the better choice.

That’s it for most named people or things or places—most are capitalized but do not require italics or quotation marks. A quick rule: Names (of people, places, and things) need to be capitalized, but titles (of things) need both capitalization and either quotation marks or italics.

Items in the following categories need neither italics nor quotation marks (unless italics or quotation marks are an intrinsic part of the title). This is only a very short list, but most named nouns are treated similarly.

car manufacturers General Motors, Volkswagen, Toyota car brands or divisions: Buick, Chevrolet car names: Riviera, Touareg, Camry restaurants: Chili’s, Sally’s Place, Chuck’s Rib House scriptures and revered religious books: the Bible, Koran, the Book of Common Prayer books of the Bible: Genesis, Acts, the Gospel according to Matthew wars and battles: Korean War, Russian Revolution, the Battle of Antietam, the Battle of Hastings companies: Coca-Cola, Amazon, Barclays, Nokia product names: Coke, Kleenex, Oreo shops: Dolly’s Delights, Macy’s, Coffee House museums, schools and colleges: the High Museum, the Hermitage, Orchard Elementary School, the University of Notre Dame houses of worship: First Baptist Church of Abbieville, the Cathedral of St. Philip, Temple Sinai, City Center Community Masjid Note : There is much more to capitalization, yet that topic requires an article (or five) of its own. Look for such an article in the future. The Chicago Manual of Style has an in-depth chapter on capitalization; I recommend you search it for specifics.

Quotation Marks and Italics

Beyond capitalization, some nouns are also distinguished by italics or quotation marks. Think in terms of titles here, but typically titles of things and not people.

So we’re talking book, movie, song, and TV show titles; titles of newspapers and magazines and titles of articles in those newspapers and magazines; titles of artwork and poems.

One odd category included here is vehicles. Not brand names of vehicles but names of individual craft: spaceships, airships, ships, and trains.

But which titles get quotation marks and which get italics?

The general rule is that titles of works that are made up of smaller/shorter divisions are italicized, and the smaller divisions are put in quotation marks . This means a book title is italicized, and chapter titles (but not chapter numbers) are in quotation marks. A TV show title is italicized, but episode titles are in quotation marks. An album or CD title is put in italics, but the song titles are in quotation marks.

Note : This rule for chapter titles in books is not referring to chapter titles of a manuscript itself, which are not put in quotation marks within the manuscript . Use quotation marks in your text if a character or narrator is thinking about or speaking a chapter title, not for your own chapter titles.

Quotation marks and italics are both also used for other purposes in fiction. For example, we typically use italics when we use a word as a word.

My stylist always says rebound when he means rebond .

I counted only half a dozen um s in the chairman’s speech. (Note that the s making um plural is not italicized.)

Since a list is quick and easy to read, let’s simply list categories for both italics and quotation marks.

Barring exceptions, items from the categories should be italicized or put in quotation marks, as indicated, in your stories.

Use Italics For

Titles : Titles of specific types of works are italicized. This is true for both narration and dialogue.

books TV shows radio shows movies plays operas and ballets long poems long musical pieces (such as symphonies) newspapers magazines journals works of art (paintings, sculptures, photographs) pamphlets reports podcasts blogs (but not websites in general, which are only capitalized)

Odds and Ends: Titles of cartoons and comic strips ( Peanuts, Calvin and Hobbes, Pearls Before Swine ) are italicized. Exhibitions at small venues (such as a museum) are italicized ( BODIES . . . The Exhibition ) but fairs and other major exhibitions (the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition) are only capitalized.

Examples : To Kill a Mockingbird (book), Citizen Kane (movie), A Prairie Home Companion (radio show), La bohème (opera), Paradise Lost (long poem), Rhapsody in Blue (long musical piece), Washington Post (newspaper), Car and Driver (magazine), Starry Night (painting), The Age of Reason (pamphlet), This American Life (podcast), The Editor’s Blog (blog)

Exception : Generic titles of musical works are not italicized. This includes those named by number (op. 3 or no. 5) or by key (Nocturne in B Major) and those simply named for the musical form (Requiem or Overture). If names and generic titles are combined, italicize only the name, not the generic title.

Exception : Titles of artwork dating from antiquity whose creators are unknown are not italicized. (the Venus de Milo or the Seated Scribe)

Ship names : names of ships on water, in space, in the air

Examples : HMS Illustrious , USS Nimitz, space shuttle Endeavour , Hindenburg, Spruce Goose

Notes: 1. The abbreviations for Her Majesty’s ship (HMS) and United States ship (USS) are not italicized.

2. The current recommendation of The Chicago Manual of Style is to not italicize train names. CMOS may be differentiating between physical ships with individual names and railroad route names, which is typically what is named when we think of trains; the specific grouping of train cars may not be named and may actually change from one trip to another. Locomotives, however, may have names. If they do, you would be safe to italicize that name.

While I understand this reasoning, I see no problem with italicizing a train’s (or a train route’s) commonly known name— Trans-Siberian Express , Royal Scotsman , California Zephyr —as writers have done in the past. This is strictly a personal opinion.

3. The definite article is unnecessary with ship names—they are names and not titles. So Yorktown rather than the Yorktown . It’s likely that characters with military backgrounds would follow this rule, but many civilians may not. If your character would say the Yorktown , then include the article.

Words as words: As already noted, words used as words are usually italicized. This helps forestall confusion when these words are not used in the usual manner.

Examples : The word haberdashery has gone out of style.

Edith wasn’t sure what lugubrious meant, but it sounded slimy to her.

Letters as letters : Letters referred to as letters are italicized.

Examples : The i in my name is silent.

On the faded treasure map, an X actually did mark the spot.

All the men in his hometown have at least three s’ s in their names.

Notes: 1. Only the letter itself is italicized for plurals. So we have s ’s, capital L s, and a dozen m’ s. (The apostrophe and concluding s are not italicized.)

2. An apostrophe is used for the plurals (lowercase letters only) to prevent confusion or the misreading of letters as words; a’ s rather than a s and i’ s rather than i s.

3. Familiar phrases including p’s and q’s and dot your i’s and cross your t’s do not require italics. (They are italicized here because I’m using them as words, not for their meaning.)

4. Letters for school grades are not italicized, though they are capitalized.

Sound words : Italicize words that stand in for sounds or reproduce sounds that characters and readers hear.

Examples : The whomp-whomp of helicopter blades drowned out her frail voice.

An annoying bzzz woke him.

C-r-rack ! Something heavy—some one heavy—fell through the rotted floorboards.

Foreign words : Uncommon or unfamiliar foreign words are italicized the first time they are used in a story. After that, roman type is sufficient. Foreign-language words familiar to most readers do not need italics. Proper names and places in foreign languages are never italicized.

Examples : The words amigo , mucho , coup d’état, risqué, nyet, and others like them are common enough that you wouldn’t need to italicize them in fiction. (I italicized them because in my example they are words used as words.)

“Use caution, my dear. That pretty flower you like so much is velenoso. It slows the heart.”

It was something my grandmother always said to me. Sie sind mein kostbares kleines Mädchen .

Building sites on the Potsdamer Platz went for a lot of money once the Berlin Wall came down.

Emphasis : Use italics to emphasize a word or part of a word. Yet don’t overdo. A character who emphasizes words all the time may sound odd. And the italics may annoy your readers.

Examples : I wanted a new dress, but I needed new shoes.

She quickly said, “It’s not what you think.”

“Sal invited everyone to the party at his uncle’s beach house. And I mean every single student from his school.”

Something—some one —shattered all the street lights.

Character thoughts : Character thoughts can be expressed in multiple ways; italics is one of those ways. (But it isn’t the only way and may not be the best way. See “ How to Punctuate Character Thoughts ” for details.)

Example : I expected more from her , he thought. But he shouldn’t have.

You can find many more tips and suggestions for cleaning up your text in The Magic of Fiction .

Use Quotation Marks For

Titles : As is done with titles and italics, titles of specific types of works are put inside quotation marks. This is true for both narration and dialogue.

book chapters (named, not numbered, chapters) TV show episodes radio show episodes songs short stories short poems (most poems) newspaper, magazine, and journal articles blog articles podcast episodes unpublished works (dissertations, manuscripts in collections)

Odds and Ends: Signs (and other notices) are typically not put in quotation marks or italicized, though they are capitalized—The back lot was marked with No Parking signs. They don’t even require hyphens for compounds—The gardener was putting up Do Not Walk on the Grass signs. However, long signs (think sentence length or longer) are put in quotation marks and not capitalized. Consider them as quotations—Did you see the handwritten sign? “Take your shoes off, line them up at the door, and walk without speaking to the second door on the left.”

The same rule applies for mottoes and maxims . An example: To Protect and Serve was the department’s old motto. Now it’s “Cover your tracks, lie if you get caught, blame your behavior on drugs, and vilify the victim.”

Examples : They read through “The Laurence Boy” in one sitting. (chapter three of Little Women )

He said he thought it was “The One With Phoebe’s Cookies.” (an episode of Friends )

My mother suggested we both read “The Gift of the Magi.” (short story)

“ The Princess Bride—Storytelling Done Right ” was written in two hours. (blog article)

Exception : Titles of regular columns in newspapers and magazines are not put in quotation marks (Dear Abby, At Wit’s End).

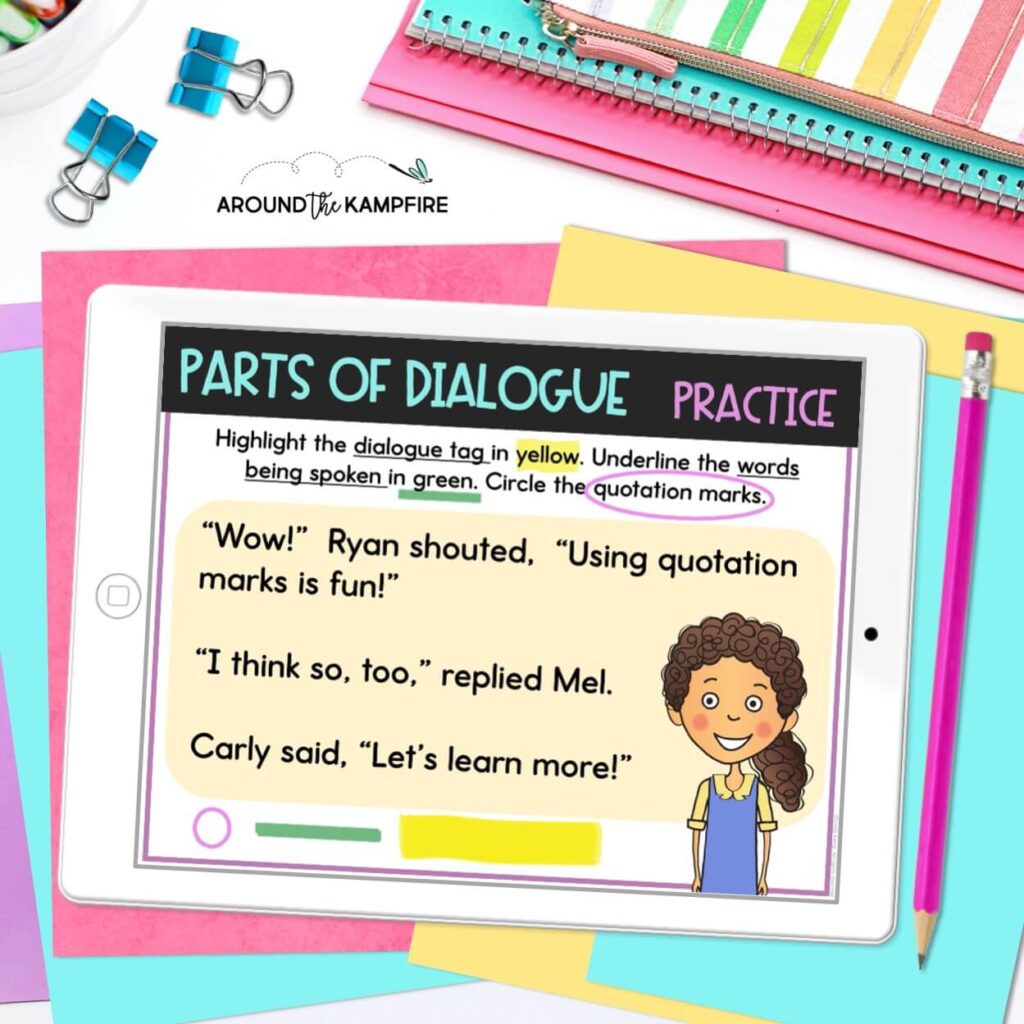

Dialogue : Enclose the spoken words of direct dialogue (not the dialogue tags or action beats) between opening and closing quotation marks. Do not use quotation marks for indirect dialogue.

Exception : When dialogue continues into a new paragraph, do not include a closing quotation mark at the end of the first paragraph; use the closing quotation mark only at the end of the spoken words. (If dialogue continues uninterrupted for several paragraphs, you will have a number of opening quotation marks but only one closing quotation mark.)

Examples : “I told you I loved you. You never believed me.”

“I told you I was there,” he said. But I never believed him.

“He tried,” I said, waving my fingers, “but he failed.”

“My dog ate the first page”—Billy pointed at Dexter Blue—“but I saved the rest.”

Exception Example : “I needed to do it, but I just couldn’t. And then you know what happened—Bing threw his knife and I ducked and he hit the minister’s wife. And then pandemonium broke out, everyone running every which way. It was madness.

“And after that, we raced out before the cops could get there.”

Notes: 1. American English (AmE) always uses double quotation marks for dialogue. If you have a quotation within dialogue, the inner quotation gets single quotation marks.

2. British English (BrE) allows for either single or double quotation marks, with the reverse for quotes inside other quotes or dialogue.

Words used in a nonstandard manner or as sarcasm, irony, or mockery : Use quotation marks to point out irony or words used in an unusual way, perhaps as slang or mockery. Most slang wouldn’t need to be put in quotation marks, but words unfamiliar to a character could be put in quotation marks. Always use double quotation marks for AmE and typically use singles for BrE (doubles are acceptable).

Example : Yeah, I guess he was on time. If three hours late is “on time” in his book.

Andy said his brother “skived off” two days this week. I didn’t tell him I had to check the Internet to figure out what he meant.

Made-up words or new words : Use quotation marks for the first use of made-up words. After that, no special punctuation is necessary.

Example : He’s a “rattlescallion,” a cross between a rapscallion and a snake.

Words as words : We often use italics for words used as words, but we can also use quotation marks.

Example: He used “I” all the time, as if his opinion carried more weight than anyone else’s.

________________________

When you’re deciding between italics and quotation marks, always remember the rules of clarity and consistency: make it clear for the reader and be consistent throughout the story. If you have to make a choice that doesn’t fit a rule or you choose to flout a rule, do so on purpose and do so each time the circumstances are the same. Include unusual words or special treatment of words in your style sheet so everyone dealing with your manuscript works from the same foundation.

Rewrite any wording that is likely to confuse the reader or that can be read multiple ways. There’s always a way to clear up confusing phrasing, often more than one way. Reduce distracting punctuation and italics when you can, but use both quotation marks and italics when necessary.

Put writing rules to work for your stories.

This article is a long one, but I hope it proves useful. Let me know if I omitted a category you wondered about.

Related posts:

- Single Quotation Marks—A Reader’s Question

- Quotes Within Quotes

- Capitalizing on the Holidays—A Reader’s Question

Tags: capitalization , italics , quotation marks Posted in: Grammar & Punctuation

Posted in Grammar & Punctuation

Leave a Reply

(Will Not Be Published) (Required)

Comments.....

Pings and Trackbacks

[…] In addition to dialogue, we use quotation marks for titles of many kinds, including songs, TV episodes, and newspaper and magazine articles. For the full list of titles we put in quotation marks, see Marking Text: Choosing Between Italics and Quotation Marks. […]

[…] Reblogged from The Editor’s Blog […]

[…] I knew there were some formatting issues in the text, such as how to show, inner thoughts, texts, quotes from other people, quotes from films or books, labels, signs, looks etc and I did some research to get some guidance. This link provided a lot of help. https://theeditorsblog.net/2014/05/12/marking-text-choosing-between-italics-and-quotation-marks/ […]

- Valid XHTML

Great Links

- Development Blog

- Documentation

- Suggest Ideas

- Support Forum

- WordPress Planet

NaNo Support Page

available in paperback Reviews Here

So maybe it's not only about the words. It's about syntax. And plot. And action. It's voice and pacing and dialogue...

It's about characters with character.

It's about putting the words together to touch, to entertain, to move the reader.

So, yeah, maybe it's all about the words...

Expanded Version Now Available in a PDF

Buy your PDF copy today

Recent Posts

- Readers Notice and They Care

- Story Goal, Story Question, and the Protagonist’s Inner Need (Story Structure Part 1)

- The Blog is Back

- Get Skilled

- The Calendar Year Changes Again

WD Tutorial

Showing & Telling

Worth Visiting

♦ CMOS Hyphens

♦ Writer's Digest

♦ Preditors & Editors

♦ Nathan Bransford

♦ Thoughts Over Coffee

♦ Writer Beware

♦ Grammar Girl

♦ Etymology Dictionary

The reader will focus on what stands out. Turn the reader's attention where you want it to go.

- A Reader Asks…

- A Writer's Life

- Announcements

- Beginning Writers

- Beyond the Basics

- Beyond the Writing

- Craft & Style

- Definitions

- Editing Tips

- For Editors

- Genre Requirements

- Grammar & Punctuation

- Launch Week

- Member Events

- Recommendations

- Self-Publishing

- Site Business

- Story Structure

- Writing Challenge

- Writing Tips

Copyright © 2010-2018 E. A. Hill Visit Beth at A Novel Edit Write well. Write often. Edit wisely.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Additional menu

The Creative Penn

Writing, self-publishing, book marketing, making a living with your writing

Writing Tips: How Writers Can Use Punctuation To Great Effect

posted on March 23, 2018

Commas are my personal nemesis. Those tiny little marks on a page can completely change the sense of a sentence, as per the fantastic book, Eats, Shoots and Leaves by Lynne Truss.

But how do we make the most of punctuation? Rachel Stout from New York Book Editors explains in today's article.

When it comes to grammar and the correct way to do things, I worry more about punctuation than anything else when writing.

Other rules — splitting infinitives, knowing the difference between further and farther or when to use the active voice versus passive — don’t weigh as heavily on my mind. I can just look those up quickly and move on, comfortable with what I’ve written.

But punctuation is not as easily referenced. In a grammar book or online, how do I describe my various clauses and intended meaning so that punctuation can correctly be assessed?

Most of my time is spent evaluating or editing manuscripts, so I can tell you that punctuation rules are some of the most commonly ignored rules in writing.

Either writers admit to me up front that they have no idea whether or not they’ve used way too many commas (answer: yes), improperly used quotation marks (answer: maybe, let me see) or used too few semicolons (answer: almost certainly no).

Understanding how and when to use common punctuation marks (meaning I’m not really interested in discussing interrobangs at the moment, or ever) will not only make you a more sophisticated and practiced writer, but it will give you the ultimate tool: knowing how and when to break those rules and use punctuation to imply feeling and tone in a way that mere word choice cannot.

Breaking punctuation rules is only effective if you’re breaking the rule on purpose.

The words, the flow, the insinuation of pause and of inflection becomes apparent in this case, and instead of mumbo jumbo, the result is something more like Molly Bloom’s “yes I said yes I will Yes,” which closes out an entire punctuation-less chapter that is full of feeling, emotion, swirling thoughts and contradictions, ending on this note of pure bliss at the close of James Joyce’s Ulysses.

“yes I said yes I will Yes” is famous not because the words chosen are anything special, but because no matter whether you’re familiar with the rest of the story, that final paragraph stirs something inside of you when you read it.

The rush of feeling, of teetering on the edge of choice and love and passion and self-doubt is so familiar, so utterly human that it’s palpable without explanation. The careful non-use of punctuation causes the reader to go ever faster, flying through the words, which again themselves aren’t of utmost importance here.

It’s the flying, the racing, the rush of getting everything in because there are no periods or commas to indicate a stop or a pause, nothing to slow the reader down or to shift course. The words themselves are chosen purposefully to accompany the punctuation (or lack thereof), making its use the most important thing in the passage.

How to get there, though? We know that punctuation can change the literal meaning of a sentence. Too many serial comma debates have ended with someone laying down the trump card stating the irrefutable difference between “I love my parents, Beyoncé, and Benedict Cumberbatch” and “I love my parents, Beyoncé and Benedict Cumberbatch” to deny that.

Cormac McCarthy, for example, has been quoted as saying, “I believe in periods, capitals, in the occasional comma, and that’s it,” and anyone who's read anything of McCarthy’s knows how much effect the starkness of the words and sparseness of punctuation adds to the depth and breadth of his work.

Where in Joyce’s chapter, the lack of punctuation results in a huge rush of intense emotion, McCarthy’s novels are quieter, though still deep in feeling. Neither author could have achieved that if they were writing without knowledge of the rules of punctuation. They were successful because they wrote in spite of them.

The first thing to note when using punctuation creatively is that there are still limitations . Not all punctuation marks can be played around with. You’ll have the best results with commas, periods, quotation marks and dashes.

Semicolons, however, don’t have the same elasticity. Colons and parentheses can be hugely effective when used intentionally, but my advice is to use them sparingly. They cause such an interruption in reading that the pause or aside should be worth it. The aside an em-dash indicates is usually not as drastic as it fits better within the flow of the sentence.

Let’s get the basics of each mark down so we can figure out how to manipulate them. When I say basics, I truly mean basics because of course pages can be written about each, but for our purposes, the basic rules will suffice.

First up, the one with the most rules, even at the basic level: the comma.

Comma Rules and Uses

Separating items in a series.

Commas are used to separate items in a series of three or more nouns or two or more coordinate adjectives. Whether or not you decide to use the serial, or Oxford, comma before the final “and” or “or” in the list is up to you.

- Example (Nouns): I went to the store and bought apples, bananas, bread and milk.

- Example (Coordinate adjectives): The bright, shining sun was warm that day.

(Note: Adjectives are coordinate if you can change their order and the meaning remains the same. If you cannot, they are not coordinate and should not be separated by commas)

Surrounding nonessential appositives

An appositive is the word or phrase that describes or adds additional information about a noun in the sentence. Only nonessential appositives are surrounded by commas. An essential appositive is a word or phrase that if removed, changes the meaning of the sentence. Essential appositives are not offset with commas. If the appositive only adds to the sentence, but does not affect its meaning, then commas are used.

- Example (Essential): Fleetwood Mac’s song Landslide has been covered by many other artists.

Here, “Landslide” is the appositive, but without it, the sentence would not have the same meaning, so we don’t use commas.

- Example (Nonessential): The house where I grew up, a blue bungalow with red shutters, has been repainted.

Here, “a blue bungalow with red shutters” is the appositive and without it, the sentence would retain its meaning: “The house where I grew up has been repainted.” This is why the appositive is offset with commas.

Before a coordinating conjunction

There are many sub-rules here, but at the most basic level, when you are connecting two independent clauses with a coordinating conjunction, you should use a comma. An independent clause is a portion of a sentence that could stand on its own and a coordinating conjunction is one of the following: and, nor, for, but, so, or, yet.

- Example: I hate eating apples, but I love eating apple pie.

After an introductory phrase

Usually, an adverbial phrase, the part of the sentence that sets up or introduces its subject and verb is the introductory phrase. (Hint: I started the previous sentence with an introductory phrase offset by a comma!) Sometimes a comma is not used, especially if the introductory phrase is made up of three words or less. (Hint: I did not offset the introductory word in that sentence, and it is grammatically okay).

- Example: After seeing the movie, we all went out for ice cream.

Breaking the Rules

So we know James Joyce doesn’t always love commas, and Cormac McCarthy certainly isn’t a fan. Gertrude Stein didn’t use them much, either, and she did okay for herself.

The most effective thing a comma does in a sentence is to create a pause. It’s a visual breathing mark or break in a sentence that can either go unnoticed or stand out.

Adding a comma where one might not necessarily be required should be an intentional choice—a moment where you are asking the reader to stop, sit up and notice. Maybe you want to call attention to the first part of a sentence or you want to make them pause awkwardly to show awkwardness in a scene.

Maybe you want to not use commas at all in dialogue to indicate a lilted accent or rushed way or speaking, or a child who doesn’t yet have a grasp on his or her own cadence, but you’ll have correct comma usage throughout all narrative portions of the text.

The best hint here? Read your work aloud as it is written, and then read it aloud as you intend it to sound. Are they different? If so, add or subtract the commas—the pauses, the emphases—where desired.

Period Rules and Uses

Ending a declarative sentence: This one doesn’t need too much explaining (I hope!). A period goes at the end of a sentence to indicate, well, its end, unless the sentence is a question or exclamation.

That’s pretty much the only hard and fast rule to using a period, which makes it a much simpler mark than the comma we just barreled through, but there is sometimes confusion as to where a period should be placed in conjunction with other punctuation marks, so here’s a quick overview:

With quotation marks: In American English, the period always goes inside the closing quotation marks. In British English, the period goes outside. After an abbreviation: If you’ve ended a sentence with an abbreviation, like “etc.,” there is no need to add a second period. With parentheses: If the parenthetical statement is its own independent clause placed in between two other full sentences, then the full sentence, including its period, goes inside the parentheses. If the statement is included in the middle of or at the end of another independent clause, the period goes at the end of the non-parenthetical statement and thus, outside of the parentheses.

- Example: I’m good at grammar. (At least I think I am.) A more accurate statement might be: I’m getting the hang of it.

- Example: I’m a grammar pro (and I don’t give myself enough credit).

Because the period is universally simple, it’s difficult to misuse! However, I like to think about the British term for a period when thinking about how best to use it to enhance my writing: the full stop.

Where a comma is a pause, a period is a full stop. Short, fragmented writing, where each phrase, independent clause or not, is separated by a period can indicate so many things. Depression, stilted thinking, disbelief, the inability to comprehend, shock—the list goes on.

Think about any moment in life where you’ve been so overcome by emotion or new information that it’s near impossible to form a complete thought. Using periods to end a sentence fragment, to bring it to a “full stop,” can indicate that numbness or that inability to process.

Of course, the opposite usage is the run-on sentence. Run-on sentences are tricky because so often they are written without intent, but used intentionally, they can indicate a different side of emotional overwhelm .

Instead of being at a loss for words, or indicating a full stop, run-on sentences indicate a racing mind, a fast-paced scene, or a glut of activity and conversation.

Here, our friend the comma comes back into play. Using a comma splice, which is to say using a comma instead of a period, should be done sparingly. If used intentionally and in the right tone, a comma splice can carry the tone of a passage.

See how clearly the image and voice of Holden Caufield becomes through this run-on sentence full of comma splices from J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye:

If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you'll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don't feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.

You can just see the teenager pretending to be apathetic about lame (and probably phony) things like caring about personal history and family.

Quotation Mark Rules and Uses

To show dialogue: The placement of punctuation inside and outside of quotation marks and whether or not to use single or double quotes vacillates between British and American English as well as between scholars in each school, so I’m not going to get into the nitty-gritty here. What you do need to know, is that the most common use of quotation marks in fiction is to indicate dialogue, or someone speaking.

They are not used to indicate a thought, even when a narrator is recalling the idea of what someone said. They are used when recalling the exact words that someone said.

- Example (recalling an idea): John remembered that Susie had told him to put his pants on when he left the house.

- Example (recalling exact words): John remembered Susie’s words so clearly. “If you forget to put your pants on, the neighbors will be angry!” He’d better put them on, he thought to himself.

Note: I threw in a bonus non-quoted thought in that last one!

To show a new person speaking: The rulebooks will tell you that when a new speaker speaks, whether in a conversation between two people or with a narrative paragraph being broken into by a speaker, a new paragraph is necessary. With each new paragraph and each line of dialogue, you must indent.

The most forgiven rules in creative fiction and memoir are those that accompany dialogue, and thus, quotation marks. However, and I’ll keep repeating myself here, it must be done with intention .

It’s very clear when an author is not aware of the rules of where to place punctuation within or outside of quotation marks (though remember, it varies between British and American), or if they are not clear on how to indicate dialogue at all. Usually, these writers are inconsistent with how they indicate or punctuate dialogue.

Consistency is what matters with quotation marks and dialogue. Do you want everything in one line, no quotation marks at all, ala Frank McCourt in Angela’s Ashes? Take a look at how colloquial, familiar, and conversational this feels:

Dad is out looking for a job again and sometimes he comes home with the smell of whiskey, singing all the songs he can about suffering Ireland. Ma gets angry and says Ireland can kiss her arse. He says that’s nice language to be using in front of the children and she says never mind the language, food on the table is what she wants, not suffering Ireland.

On top of the conversational tone and the speed with which you begin to race through the sentence, the perspective here is limited, a little rough around the edges. That’s because at this moment, the narrator is a small child and thus, takes in everything about the world in a particular way.

Using or not using quotes, indenting, breaking paragraphs and all the other rules surrounding dialogue affect style as much as tone.

How do you want the words to look on the page? Many paragraph breaks can achieve the same stilted or at-a-loss feeling as fragmented sentences separated by periods can. The same read aloud test can be used here.

Em-Dashes, Colons, and Parentheses Rules

I’m lumping all of these together because they all achieve a similar goal in creative writing: to indicate an aside, amplify a portion of a sentence or thought, or to offer an alternative point of view.

If you don’t know which to use, my rule of thumb is to always go em-dash, though as I said at the start of this post, you’ve got to be careful not to go overboard.

Using a colon: Unless you’re formatting a list, the only time to use a colon is after an already complete thought. What comes after the colon usually amplifies or expands upon the first portion, but doesn’t indicate much of a pause.

- Example: Sarah has two favorite foods: pizza and ice cream.

Using parentheses: Em-dashes have eclipsed parentheses when used to separate explanatory or qualifying remarks from the rest of the sentence. Using either is correct, but only parentheses can be used to offset a complete sentence or thought, usually as an aside.

Using em-dashes: Aside from replacing parentheses when used within a complete sentence, the em-dash can also set off appositives like commas, indicate a switch in focus, or bring focus to a list connected to a clause.

- Example (replacing parentheses): Mary always said she was an expert in fencing—she’s really not.

- Example (setting off appositives): All three of my dogs—Fluffy, Bumper and Duke—have different personalities.

- Example (switch in focus): And now I will tell you my greatest secret—actually, no, I’ve changed my mind.

- Example (bring focus to a list): Sunscreen, towel, book—everything is packed for the beach!

Here’s where you can have the most fun, in my opinion.

As long as you don’t overuse them, it’s very difficult to misuse a colon, parentheses or em-dash.

Do you want your narrator interjecting his or her own thoughts all the time in a distinctive voice or take on life? Em-dash, em-dash, em-dash!

Do you want to formally and distinctively expand upon a thought, or make that expansion seem like an awaited reveal or an extremely important detail? Use a colon!

Are we getting a whispered aside, an alternative viewpoint, or something special that only the reader gets to know and not others in the story? Do you want to tell a story within a story? Parentheses can achieve that for you!

I often see these three punctuation marks as the playful ones, the marks that can really bring a liveliness to your writing and showcase the voice of a particular character or narrator. Use them sparingly, yes, but play around and see how adding a few em-dashes into your narrative might bring out a new side to your story that even you were unaware was there.

Thanks for going on this whirlwind Punctuation 101 with me. I know it can be exhausting to get down, but once you’ve got the basics firm in your toolbox, you can begin to play with them, alter them to your whim and intentionally manipulate punctuation to change the tone or impact your writing has.

Do you have a favorite punctuation mark? Do you have a favorite author who flagrantly bucks the rules? Please leave your thoughts below and join the conversation.

New York Book Editors are a team of professional editors who have worked with some of the biggest names in the industry as well as offering services to indie authors. They provide in-depth manuscript reviews, manuscript critique, comprehensive edit, proposal edit, copyediting and ghostwriting.

Reader Interactions

March 23, 2018 at 3:13 am

I like breaking the rules when it comes to grammar from time to time. Of course, I keep my writing flow simple and to the point.

I’m talking about writing for a blog here. If we’re talking about writing a book or something it’s a different story.

I don’t think most blog readers really care about how good your grammar is as long as it is okay and they can understand the information you are trying to get across.

But, it is always a good idea to learn the proper grammar and use of a comma. I love commas, they do change the way you deliver information.

Thank you for sharing all of these tips and useful information! 🙂

Have a wonderful weekend! 😀

March 23, 2018 at 3:30 pm

Breaking the rules is the best part about having rules!

March 23, 2018 at 8:23 am

Now *that* is a guide! It covers almost everything people will need, each point is clear, but laid out so it’s genuinely fun. This goes straight into my Perennial Recommendations list– thank you, Rachel!

One rule of thumb I’d like to add, for one extra-common mistake I keep seeing:

If you write the characters endquote-period-lowercase, always change it to endquote-comma-lowercase. Also, if the word after an endquote is a name or other capitalized proper noun, imagine it as a simple pronoun to decide whether it would be lowercase, and if it would be, use the comma as above. Some lines with their corrections, and some that don’t need changing, are:

“Here’s one example.” he said. –> “Here’s one example,” he said. “Another example.” John said. –> “Another example,” John said. “There’s no change needed here.” John had little else to say. “And no change needed needed when it ends without a tag.”

March 23, 2018 at 3:23 pm

Rachel here! Thanks for your note and even MORE for you addition. I thought about adding in a note about that, but then realized I’d be taking up almost the whole thing with commas, so I’m glad you commented!

March 23, 2018 at 3:24 pm

Hah, KEN! I read John in your examples and ran with it. – Rachel

March 24, 2018 at 11:07 am

“John” does a lot of my examples. As for myself, I’v e been called worse things. 🙂

March 24, 2018 at 11:58 pm

I’m obsessed with punctuation, with commas in particular, and sloppy use of the latter can turn me off even a very good book. Thanks for featuring this useful article!

March 30, 2018 at 4:02 pm

I think I overdo commas. That’s what I’m trying to improve.

April 18, 2018 at 7:42 am

Rachel, thank you for this excellent exposition. It’s remarkable to me how many writers I’ve encountered who believe that some punctuation marks should simply never be used. This is a view I’ve never shared. It’s not enough to say, for example, that em-dashes are pointless because commas or parentheses can fulfill the same function (an actual argument one of my writing colleagues once made). False. Em-dashes can be used in ways to achieve emotional effects that commas can’t (as your examples show). And I totally agree with your overriding principle: understanding the how and the when of punctuation, so that you know how to deviate with intention.

May 12, 2018 at 7:58 am

You say, “With quotation marks: In American English, the period always goes inside the closing quotation marks. In British English, the period goes outside.”

My understanding is the in British English, where you put the quotation marks depends on how much of the sentence that the period ends is inside the quotation marks. So, if the whole sentence is a quote, you punctuate the same as in American English. But if only the last two words, or an short phrase within the sentence is at the end, then the quote goes inside the period because the end quote doesn’t cover the entire thing that the period covers. And the reason that Americans don’t want to do it the British way, is that you have to think about where the quote begins to know how to punctuate the end of the sentence.

I think a sentence where the last word is in quotes and you put the end quote outside the period doesn’t really make sense and the British rules make more sense. If they always put the quote inside the period, even when the beginning quote started at the beginning of the sentence, then their rules would also not make sense, I think. The quote really should end after the quoted material with whatever punctuation comes within the quoted material inside the end quote, don’t you think.

There might be a reader who is more of an expert on British English that can tell you if my understanding is really correct.

Thank you for this article. I found it fascinating!

May 13, 2018 at 1:21 am

I think it’s important to recognize that there is never an exactly right answer to many of these questions, as style and usage changes over time and place. There are many variations.

September 12, 2019 at 4:27 pm

It would *surpris!ing* if writers didn’t sometimes utilize! the graphic potential of the medium

September 2, 2020 at 3:11 pm

Which is the correct use of comma with quotation marks – in American English?

1. Tolle calls this emotional part of the Ego the “pain body,” the aspect of the Ego…

2. Tolle calls this emotional part of the Ego the “pain body”, the aspect of the Ego…

December 31, 2020 at 12:19 pm

What about colons instead of commas before a quote? example: The man stood up, said: “Why are you so short?” I’ve read a few stories that use this form of punctuation, which is what I used in my novel. However, I’ve heard some who say that it ruins the flow, like a speed bump. I think it sounds fine–but I wrote it :0)

March 14, 2024 at 3:53 pm

When using three periods to indicatexa pause, often in dialogue, isit … or. . . With spaces? Thanks!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of followup comments via e-mail

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Connect with me on social media

Sign up for your free author blueprint.

Thanks for visiting The Creative Penn!

Go to Index

Subscribe to The Chicago Manual of Style Online

Sign up for a free trial

Now Available for Preorder! The Chicago Manual of Style, 18th Edition

NEW! CMOS 18 Merch!!

CMOS for PerfectIt Proofreading Software

Quotations and Dialogue

Q. How do you handle text-message content? Is it put in quotation marks or do you use italics?

A. A message is a message, whether it comes from a book, an interview, lipstick on a mirror, or your phone. Use quotation marks to quote.

The CMOS Shop Talk Blog

CMOS editors share writing tips, editing ideas, interviews, quizzes, and more!

NEW! The Chicago Guide for Freelance Editors, by Erin Brenner

NEW! The CSE Manual: Scientific Style and Format, Ninth Edition

NEW! The Design of Books, by Debbie Berne

NEW! Developmental Editing, Second Edition, by Scott Norton

Retro Chic(ago)

%20Disco.png)

Visit the CMOS Bookstore

Charitable Giving Helps Advance Our Mission

Books for students, writers, and editors.

What this handout is about

Used effectively, quotations can provide important pieces of evidence and lend fresh voices and perspectives to your narrative. Used ineffectively, however, quotations can clutter your text and interrupt the flow of your argument. This handout will help you decide when and how to quote like a pro.

When should I quote?

Use quotations at strategically selected moments. You have probably been told by teachers to provide as much evidence as possible in support of your thesis. But packing your paper with quotations will not necessarily strengthen your argument. The majority of your paper should still be your original ideas in your own words (after all, it’s your paper). And quotations are only one type of evidence: well-balanced papers may also make use of paraphrases, data, and statistics. The types of evidence you use will depend in part on the conventions of the discipline or audience for which you are writing. For example, papers analyzing literature may rely heavily on direct quotations of the text, while papers in the social sciences may have more paraphrasing, data, and statistics than quotations.

Discussing specific arguments or ideas

Sometimes, in order to have a clear, accurate discussion of the ideas of others, you need to quote those ideas word for word. Suppose you want to challenge the following statement made by John Doe, a well-known historian:

“At the beginning of World War Two, almost all Americans assumed the war would end quickly.”

If it is especially important that you formulate a counterargument to this claim, then you might wish to quote the part of the statement that you find questionable and establish a dialogue between yourself and John Doe:

Historian John Doe has argued that in 1941 “almost all Americans assumed the war would end quickly” (Doe 223). Yet during the first six months of U.S. involvement, the wives and mothers of soldiers often noted in their diaries their fear that the war would drag on for years.

Giving added emphasis to a particularly authoritative source on your topic.

There will be times when you want to highlight the words of a particularly important and authoritative source on your topic. For example, suppose you were writing an essay about the differences between the lives of male and female slaves in the U.S. South. One of your most provocative sources is a narrative written by a former slave, Harriet Jacobs. It would then be appropriate to quote some of Jacobs’s words:

Harriet Jacobs, a former slave from North Carolina, published an autobiographical slave narrative in 1861. She exposed the hardships of both male and female slaves but ultimately concluded that “slavery is terrible for men; but it is far more terrible for women.”

In this particular example, Jacobs is providing a crucial first-hand perspective on slavery. Thus, her words deserve more exposure than a paraphrase could provide.

Jacobs is quoted in Harriet A. Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, ed. Jean Fagan Yellin (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987).

Analyzing how others use language.

This scenario is probably most common in literature and linguistics courses, but you might also find yourself writing about the use of language in history and social science classes. If the use of language is your primary topic, then you will obviously need to quote users of that language.

Examples of topics that might require the frequent use of quotations include:

Southern colloquial expressions in William Faulkner’s Light in August

Ms. and the creation of a language of female empowerment

A comparison of three British poets and their use of rhyme

Spicing up your prose.

In order to lend variety to your prose, you may wish to quote a source with particularly vivid language. All quotations, however, must closely relate to your topic and arguments. Do not insert a quotation solely for its literary merits.

One example of a quotation that adds flair:

President Calvin Coolidge’s tendency to fall asleep became legendary. As H. L. Mencken commented in the American Mercury in 1933, “Nero fiddled, but Coolidge only snored.”

How do I set up and follow up a quotation?

Once you’ve carefully selected the quotations that you want to use, your next job is to weave those quotations into your text. The words that precede and follow a quotation are just as important as the quotation itself. You can think of each quote as the filling in a sandwich: it may be tasty on its own, but it’s messy to eat without some bread on either side of it. Your words can serve as the “bread” that helps readers digest each quote easily. Below are four guidelines for setting up and following up quotations.

In illustrating these four steps, we’ll use as our example, Franklin Roosevelt’s famous quotation, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

1. Provide context for each quotation.

Do not rely on quotations to tell your story for you. It is your responsibility to provide your reader with context for the quotation. The context should set the basic scene for when, possibly where, and under what circumstances the quotation was spoken or written. So, in providing context for our above example, you might write:

When Franklin Roosevelt gave his inaugural speech on March 4, 1933, he addressed a nation weakened and demoralized by economic depression.

2. Attribute each quotation to its source.

Tell your reader who is speaking. Here is a good test: try reading your text aloud. Could your reader determine without looking at your paper where your quotations begin? If not, you need to attribute the quote more noticeably.

Avoid getting into the “they said” attribution rut! There are many other ways to attribute quotes besides this construction. Here are a few alternative verbs, usually followed by “that”:

| add | remark | exclaim |

| announce | reply | state |

| comment | respond | estimate |

| write | point out | predict |

| argue | suggest | propose |

| declare | criticize | proclaim |

| note | complain | opine |

| observe | think | note |

Different reporting verbs are preferred by different disciplines, so pay special attention to these in your disciplinary reading. If you’re unfamiliar with the meanings of any of these words or others you find in your reading, consult a dictionary before using them.

3. Explain the significance of the quotation.

Once you’ve inserted your quotation, along with its context and attribution, don’t stop! Your reader still needs your assessment of why the quotation holds significance for your paper. Using our Roosevelt example, if you were writing a paper on the first one-hundred days of FDR’s administration, you might follow the quotation by linking it to that topic:

With that message of hope and confidence, the new president set the stage for his next one-hundred days in office and helped restore the faith of the American people in their government.

4. Provide a citation for the quotation.

All quotations, just like all paraphrases, require a formal citation. For more details about particular citation formats, see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . In general, you should remember one rule of thumb: Place the parenthetical reference or footnote/endnote number after—not within—the closed quotation mark.

Roosevelt declared, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself” (Roosevelt, Public Papers, 11).

Roosevelt declared, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”1

How do I embed a quotation into a sentence?

In general, avoid leaving quotes as sentences unto themselves. Even if you have provided some context for the quote, a quote standing alone can disrupt your flow. Take a look at this example:

Hamlet denies Rosencrantz’s claim that thwarted ambition caused his depression. “I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself a king of infinite space” (Hamlet 2.2).

Standing by itself, the quote’s connection to the preceding sentence is unclear. There are several ways to incorporate a quote more smoothly:

Lead into the quote with a colon.

Hamlet denies Rosencrantz’s claim that thwarted ambition caused his depression: “I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself a king of infinite space” (Hamlet 2.2).

The colon announces that a quote will follow to provide evidence for the sentence’s claim.

Introduce or conclude the quote by attributing it to the speaker. If your attribution precedes the quote, you will need to use a comma after the verb.

Hamlet denies Rosencrantz’s claim that thwarted ambition caused his depression. He states, “I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself a king of infinite space” (Hamlet 2.2).

When faced with a twelve-foot mountain troll, Ron gathers his courage, shouting, “Wingardium Leviosa!” (Rowling, p. 176).

The Pirate King sees an element of regality in their impoverished and dishonest life. “It is, it is a glorious thing/To be a pirate king,” he declares (Pirates of Penzance, 1983).

Interrupt the quote with an attribution to the speaker. Again, you will need to use a comma after the verb, as well as a comma leading into the attribution.

“There is nothing either good or bad,” Hamlet argues, “but thinking makes it so” (Hamlet 2.2).

“And death shall be no more,” Donne writes, “Death thou shalt die” (“Death, Be Not Proud,” l. 14).

Dividing the quote may highlight a particular nuance of the quote’s meaning. In the first example, the division calls attention to the two parts of Hamlet’s claim. The first phrase states that nothing is inherently good or bad; the second phrase suggests that our perspective causes things to become good or bad. In the second example, the isolation of “Death thou shalt die” at the end of the sentence draws a reader’s attention to that phrase in particular. As you decide whether or not you want to break up a quote, you should consider the shift in emphasis that the division might create.

Use the words of the quote grammatically within your own sentence.