12.7 Prosocial Behavior

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe altruism

- Describe conditions that influence the formation of relationships

- Identify what attracts people to each other

- Describe the triangular theory of love

- Explain social exchange theory in relationships

You’ve learned about many of the negative behaviors of social psychology, but the field also studies many positive social interactions and behaviors. What makes people like each other? With whom are we friends? Whom do we date? Researchers have documented several features of the situation that influence whether we form relationships with others. There are also universal traits that humans find attractive in others. In this section we discuss conditions that make forming relationships more likely, what we look for in friendships and romantic relationships, the different types of love, and a theory explaining how our relationships are formed, maintained, and terminated.

Prosocial Behavior and Altruism

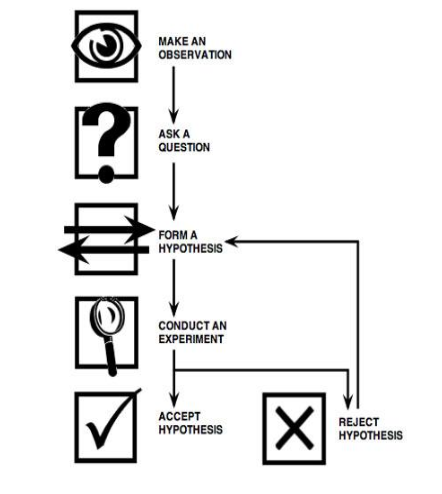

Do you voluntarily help others? Voluntary behavior with the intent to help other people is called prosocial behavior . Why do people help other people? Is personal benefit such as feeling good about oneself the only reason people help one another? Research suggests there are many other reasons. Altruism is people’s desire to help others even if the costs outweigh the benefits of helping. In fact, people acting in altruistic ways may disregard the personal costs associated with helping ( Figure 12.26 ). For example, news accounts of the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in New York reported an employee in the first tower helped his co-workers make it to the exit stairwell. After helping a co-worker to safety he went back in the burning building to help additional co-workers. In this case the costs of helping were great, and the hero lost his life in the destruction (Stewart, 2002).

Some researchers suggest that altruism operates on empathy. Empathy is the capacity to understand another person’s perspective, to feel what they feel. An empathetic person makes an emotional connection with others and feels compelled to help (Batson, 1991). Other researchers argue that altruism is a form of selfless helping that is not motivated by benefits or feeling good about oneself. Certainly, after helping, people feel good about themselves, but some researchers argue that this is a consequence of altruism, not a cause. Other researchers argue that helping is always self-serving because our egos are involved, and we receive benefits from helping (Cialdini, Brown, Lewis, Luce, & Neuberg 1997). It is challenging to determine experimentally the true motivation for helping, whether it is largely self-serving (egoism) or selfless (altruism). Thus, a debate on whether pure altruism exists continues.

Link to Learning

See this excerpt from the popular TV series Friends in which egoism versus altruism is debated to learn more.

Forming Relationships

What do you think is the single most influential factor in determining with whom you become friends and with whom you form romantic relationships? You might be surprised to learn that the answer is simple: the people with whom you have the most contact. This most important factor is proximity. You are more likely to be friends with people you have regular contact with. For example, there are decades of research that shows that you are more likely to become friends with people who live in your dorm, your apartment building, or your immediate neighborhood than with people who live farther away (Festinger, Schachler, & Back, 1950). It is simply easier to form relationships with people you see often because you have the opportunity to get to know them.

Similarity is another factor that influences who we form relationships with. We are more likely to become friends or lovers with someone who is similar to us in background, attitudes, and lifestyle. In fact, there is no evidence that opposites attract. Rather, we are attracted to people who are most like us ( Figure 12.27 ) (McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, 2001). Why do you think we are attracted to people who are similar to us? Sharing things in common will certainly make it easy to get along with others and form connections. When you and another person share similar music taste, hobbies, food preferences, and so on, deciding what to do with your time together might be easy. Homophily is the tendency for people to form social networks, including friendships, marriage, business relationships, and many other types of relationships, with others who are similar (McPherson et al., 2001).

But, homophily limits our exposure to diversity (McPherson et al., 2001). By forming relationships only with people who are similar to us, we will have homogenous groups and will not be exposed to different points of view. In other words, because we are likely to spend time with those who are most like ourselves, we will have limited exposure to those who are different than ourselves, including people of different races, ethnicities, social-economic status, and life situations.

Once we form relationships with people, we desire reciprocity. Reciprocity is the give and take in relationships. We contribute to relationships, but we expect to receive benefits as well. That is, we want our relationships to be a two way street. We are more likely to like and engage with people who like us back. Self-disclosure is part of the two way street. Self-disclosure is the sharing of personal information (Laurenceau, Barrett, & Pietromonaco, 1998). We form more intimate connections with people with whom we disclose important information about ourselves. Indeed, self-disclosure is a characteristic of healthy intimate relationships, as long as the information disclosed is consistent with our own views (Cozby, 1973).

We have discussed how proximity and similarity lead to the formation of relationships, and that reciprocity and self-disclosure are important for relationship maintenance. But, what features of a person do we find attractive? We don’t form relationships with everyone that lives or works near us, so how is it that we decide which specific individuals we will select as friends and lovers?

Researchers have documented several characteristics that humans find attractive. First we look for friends and lovers who are physically attractive. People differ in what they consider attractive, and attractiveness is culturally influenced. Research, however, suggests that some universally attractive features in women include large eyes, high cheekbones, a narrow jaw line, a slender build (Buss, 1989), and a lower waist-to-hip ratio (Singh, 1993). For men, attractive traits include being tall, having broad shoulders, and a narrow waist (Buss, 1989). Both men and women with high levels of facial and body symmetry are generally considered more attractive than asymmetric individuals (Fink, Neave, Manning, & Grammer, 2006; Penton-Voak et al., 2001; Rikowski & Grammer, 1999). Social traits that people find attractive in potential female mates include warmth, affection, and social skills; in males, the attractive traits include achievement, leadership qualities, and job skills (Regan & Berscheid, 1997). Although humans want mates who are physically attractive, this does not mean that we look for the most attractive person possible. In fact, this observation has led some to propose what is known as the matching hypothesis which asserts that people tend to pick someone they view as their equal in physical attractiveness and social desirability (Taylor, Fiore, Mendelsohn, & Cheshire, 2011). For example, you and most people you know likely would say that a very attractive movie star is out of your league. So, even if you had proximity to that person, you likely would not ask them out on a date because you believe you likely would be rejected. People weigh a potential partner’s attractiveness against the likelihood of success with that person. If you think you are particularly unattractive (even if you are not), you likely will seek partners that are fairly unattractive (that is, unattractive in physical appearance or in behavior).

Sternberg’s Triangular Theory of Love

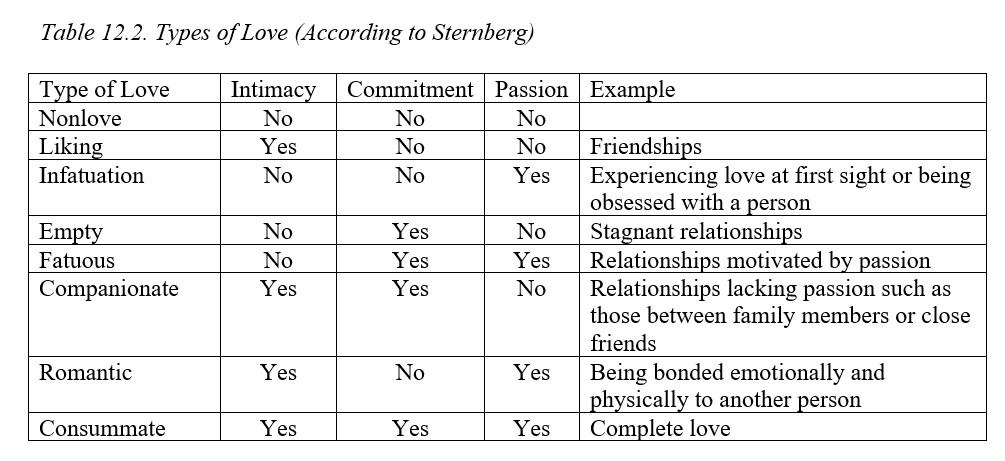

We typically love the people with whom we form relationships, but the type of love we have for our family, friends, and lovers differs. Robert Sternberg (1986) proposed that there are three components of love: intimacy, passion, and commitment. These three components form a triangle that defines multiple types of love: this is known as Sternberg’s triangular theory of love ( Figure 12.28 ). Intimacy is the sharing of details and intimate thoughts and emotions. Passion is the physical attraction—the flame in the fire. Commitment is standing by the person—the “in sickness and health” part of the relationship.

Sternberg (1986) states that a healthy relationship will have all three components of love—intimacy, passion, and commitment—which is described as consummate love ( Figure 12.29 ). However, different aspects of love might be more prevalent at different life stages. Other forms of love include liking, which is defined as having intimacy but no passion or commitment. Infatuation is the presence of passion without intimacy or commitment. Empty love is having commitment without intimacy or passion. Companionate love , which is characteristic of close friendships and family relationships, consists of intimacy and commitment but no passion. Romantic love is defined by having passion and intimacy, but no commitment. Finally, fatuous love is defined by having passion and commitment, but no intimacy, such as a long term sexual love affair. Can you describe other examples of relationships that fit these different types of love?

Social Exchange Theory

We have discussed why we form relationships, what attracts us to others, and different types of love. But what determines whether we are satisfied with and stay in a relationship? One theory that provides an explanation is social exchange theory. According to social exchange theory , we act as naïve economists in keeping a tally of the ratio of costs and benefits of forming and maintaining a relationship with others ( Figure 12.30 ) (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003).

People are motivated to maximize the benefits of social exchanges, or relationships, and minimize the costs. People prefer to have more benefits than costs, or to have nearly equal costs and benefits, but most people are dissatisfied if their social exchanges create more costs than benefits. Let’s discuss an example. If you have ever decided to commit to a romantic relationship, you probably considered the advantages and disadvantages of your decision. What are the benefits of being in a committed romantic relationship? You may have considered having companionship, intimacy, and passion, but also being comfortable with a person you know well. What are the costs of being in a committed romantic relationship? You may think that over time boredom from being with only one person may set in; moreover, it may be expensive to share activities such as attending movies and going to dinner. However, the benefits of dating your romantic partner presumably outweigh the costs, or you wouldn’t continue the relationship.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Rose M. Spielman, William J. Jenkins, Marilyn D. Lovett

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Psychology 2e

- Publication date: Apr 22, 2020

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/12-7-prosocial-behavior

© Jan 6, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Relationship Theories Revision Notes

Will Goulder

Psychology A-level Teacher

BSc (Hons), Psychology

Psychology and performing arts teacher in Canterbury. Deputy head of language and arts, and digital technology leader.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

What do the examiners look for?

- Accurate and detailed knowledge

- Clear, coherent, and focused answers

- Effective use of terminology (use the “technical terms”)

In application questions, examiners look for “effective application to the scenario,” which means that you need to describe the theory and explain the scenario using the theory making the links between the two very clear. If there is more than one individual in the scenario you must mention all of the characters to get to the top band.

Difference between AS and A level answers

The descriptions follow the same criteria; however, you have to use the issues and debates effectively in your answers. “Effectively” means that it needs to be linked and explained in the context of the answer.

Read the model answers to get a clearer idea of what is needed.

Exam Paper Advice

In the exam, you will be asked a range of questions on relationships, which may include questions about research methods or using mathematical skills based on research into relationships.

As in Paper One and Two, you may be asked a 16-mark question, which could include an item (6 marks for AO1 Description, 4 marks for AO2 Application, and 6 marks for AO3 Evaluation) or simply to discuss the topic more generally (6 marks AO1 Description and ten marks AO2 Evaluation).

There is no guarantee that a 16-mark question will be asked on this topic, though, so it is important to have a good understanding of all of the different areas linked to the topic.

There will be 24 marks for relationship questions, so you can expect to spend about 30 minutes on this section, but this is not a strict rule.

The evolutionary explanations for partner preferences

The relationship between sexual selection and human reproductive behavior.

Evolutionary approaches state that animals are motivated to select a ‘mate’ with the best possible genes who will best be able to ensure the offspring’s future health and survival.

Anisogamy means two sex cells (or gametes) that are different coming together to reproduce. Men have sperm cells, which can reproduce quickly with little energy expenditure, and once they start being produced, they do not usually stop until the man dies.

Female gametes (eggs or ova) are, in contrast, much less plentiful; they are released in a limited time frame (between puberty and menopause) and require much more energy to produce.

This difference (anisogamy) means that men and women use different strategies when choosing partners.

Inter-sexual Selection

Intersexual selection is the preferred strategy of the female. They value quality over quantity.

Intersexual selection is when one gender makes mate choices based on a specific characteristic of the other gender: e.g., peahens choosing peacocks with larger tails. As a result, peacock tails become larger across the population because peacocks with larger tails will mate more, thus passing these characteristics on.

Females lose more resources than men if they choose a sub-standard partner, so they are pickier about who they select. They are more likely to pick a partner who is genetically fit and willing to offer the maximum resources to raise their offspring (a man who will remain by her side as the child grows to protect them both and potentially provide more children).

Females tend to seek a man who displays physical health characteristics and is a high-status individual who controls resources within the social group. Thus male partners are able to protect, provide and control food and resources. Although this ability may have equated to muscular strength in our evolutionary past, in modern society, it is more likely to relate to occupation, social class, and wealth.

If they have made a good choice, then their offspring will inherit the positive features of their father and are therefore also more likely to be chosen by women or men in the next generation.

Intra-sexual Selection

Intrasexual selection is the preferred strategy of the male. They value quantity over quality. Anisogamy suggests that men’s best evolutionary strategy is to have as many partners as possible.

To succeed, men must compete with other males to present themselves as the most attractive mate, encouraging features such as muscles that indicate to the opposite sex an ability to protect both themselves and their offspring.

Intrasexual selection refers to competition between members of the same sex for access to a mate of the opposite sex. Whatever characteristics led to success in mating will be passed on to the next generation, thus becoming more widespread in the gene pool.

Buss (1989) surveyed over 10,000 adults in 33 countries and found that females reported valuing resource-based characteristics when choosing a male (such as their jobs) whilst men valued good looks and preferred younger partners more than females did.

Although the size and scale of Buss’s work are impressive, his use of questionnaires could lead to social desirability bias, with participants answering in socially desirable ways rather than honestly. Also, 77% of participants were from Western industrial nations, meaning Buss might have been measuring the effects of culture rather than an evolutionary-determined behavior.

Clark and Hatfield (1989) conducted a now infamous study where male and female psychology students were asked to approach fellow students of Florida State University (of the opposite sex) and ask them for one of three things; to go on a date, to go back to their apartment, or to go to bed with them.

About 50% of men and women agreed to the date, but 69% of men agreed to visit the apartment, and 75% agreed to go to bed with them; only 6% of women agreed to go to the apartment, and 0% accepted the more intimate offer.

The evolutionary approach is determinist suggesting that we have little free will in partner choice. However, everyday experience tells us we have some control over our preferences. Evolutionary approaches to mate preferences are socially sensitive in that they promote traditional (sexist) views regarding what are ‘natural’ male and female roles and behaviors.

Gender bias – In today’s society, women are more career orientated and, therefore,, will not look for resourceful partners as much – Evolutionary theory does not apply to modern society.

Finally, the evolutionary theory makes little attempt to explain other types of relationships, e.g., gay and lesbian relationships, and cultural variations in relationships that exist across the world, e.g., arranged marriages.

Factors Affecting Attraction

Self disclosure.

This refers to the extent to which a person reveals thoughts, feelings, and behaviors which they would usually keep private from a potential partner. This increases feelings of intimacy.

In the initial stages of a relationship, couples often seek to learn as much as they can about their new partner and feel that this sharing of information brings them closer together. But can too much sharing scare your partner away? Is not sharing very much information intriguing or frustrating?

Altman and Taylor (1973) identified breadth and depth as important factors of self-disclosure . At the start of a relationship, self-disclosure is likely to cover a range of topics as you seek to explore the key facts about your new partner. “What do you do for work” and “Where did you last go on holiday” but these topics are relatively superficial.

As the relationship develops, people tend to share more detailed and personal information, such as past traumas and desires for the future. If this sharing happens too soon, however, an incompatibility may be found before the other person has reached a suitable level of investment in the relationship. Altman and Taylor referred to this sharing of information as social penetration .

An important aspect of this is the reciprocity of the process; if one person shares more than the other is willing to, there may be a breakdown of trust as one person establishes themselves as more invested than the other.

Aron et al. (1997) found that by providing a list of questions to pairs of people that start with superficial information (Who would be your perfect dinner party guest) and moving over 36 questions to more intimate information (Of all the people in your family, whose death would you find the most disturbing) people grew closer and more intimate as the questions progressed.

Aron’s research also included a four-minute stare at the end of the question sequence, which may have also contributed to the increased intimacy.

Sprecher and Hendrick (2004) observed couples on dates and found a close correlation between the amount of satisfaction each person felt and the overall self-disclosure that occurred between the partners.

However, much of the research into self-disclosure is correlational, which means that a causal relationship cannot be easily determined; in short, it may be that it is the attraction between partners which leads to greater self-disclosure, rather than the sharing of information, that leads to greater intimacy.

Physical attractiveness: including the matching hypothesis

Physical attractiveness is viewed by society as one of the most important factors of relationship formation, but is this view supported by research?

Physical appearance can be seen as a range of indicators of underlying characteristics. Women with a favorable waist-to-hip ratio are seen as attractive because they are perceived to be more fertile (Singh, 2002), and people with more symmetrical features are seen to be more genetically fit.

This is because our genes are designed to make us develop symmetrically, but diseases and infections during physical development can cause these small imperfections and asymmetries (Little and Jones, 2003).

The halo effect is a cognitive bias (mental shortcut) that occurs when a person assumes that a person has positive traits in terms of personality and other features because they have a pleasing appearance.

Dion, Berscheid, and Walster (1972) asked participants to rate photographs of three strangers for a number of different categories, including personality traits such as overall happiness and career success.

When these results were compared to the physical attraction rating of each participant (from a rating of 100 students), the photographs which were rated the most physically attractive were also rated higher on the other positive traits.

Walster et al. proposed The Matching Hypothesis that similar people end up together. The more physically desirable someone is, the more desirable they would expect their partner to be. An individual would often choose to date a partner of approximately their own attractiveness.

The matching hypothesis (Walster et al., 1966) suggests that people realize at a young age that not everybody can form relationships with the most attractive people, so it is important to evaluate their own attractiveness and, from this, partners who are the most attainable.

If a person always went for people “out of their league” in terms of physical attractiveness, they may never find a partner, which would be evolutionarily foolish. This identification of those who have a similar level of attraction, and therefore provide a balance between the level of competition (intra-sexual) and positive traits, is referred to as matching.

Modern dating in society is increasingly visual, with the rise of online dating, particularly using apps such as Tinder.

In Dion et al.’s (1972) study, those who were rated to be the most physically attractive were not rated highly on the statement “Would be a good parent,” which could be seen to contradict theories about inter and intra-sexual selection.

Landy and Aronson (1969) show how the halo effect occurs in other contexts. They found that when victims of crime were perceived to be more attractive, defendants in court cases were more likely to be given longer sentences by a simulated jury.

When the defendants were unattractive, they were more likely to be sentenced by the jury, which supports the idea that we generalize physical attractiveness as an indicator of other, less visual traits such as trustworthiness.

Feingold (1988) conducted a meta-analysis of 17 studies and found a significant correlation between the perceived attractiveness of actual partners rated by independent participants.

Individual differences – Towhey et al. found that some people are less sensitive to physical attractiveness when making judgments of personality and likeability – The effects of physical attractiveness can be moderated by other factors and is not significant.

The Filter Theory

Kerckhoff and Davis (1962) suggested that when selecting partners from a range of those who are potentially available to them (a field of availability), people will use three filters to “narrow down” the choice to those who they have the best chance of a sustainable relationship with.

The filter model speaks about three “levels of filters” which are applied to partners.

The first filter proposed when selecting partners were social demography . Social variables such as age, social background, ethnicity, religion, etc., determine the likelihood of individuals meeting and socializing, which will, in turn, influence the likelihood of a relationship being formed.

We are also more likely to prefer potential partners with whom we share social demography as they are more similar to us, and we share more in common with them in terms of norms, attitudes, and experiences.

The second filter that Kerckhoff and Davis suggested was similarity in attitudes . Psychological variables to do with shared beliefs and attitudes are the best predictor of a relationship becoming stable. Disclosure is essential at this stage to ensure partners really do share genuine similarities.

This was supported by their original 1962 longitudinal study of two groups of student couples (those who had been together for more or less than 18 months).

Over seven months, the couples completed questionnaires based on their views and attitudes, which were then compared for similarities. Kerckhoff and Davis suggested that the similarity of attitudes was the most important factor in the group that had been together for less than 18 months. This is supported by the self-disclosure research described elsewhere on this topic.

The third filter was complementarity which goes a step further than similarity. Rather than having the same traits and attitudes, such as dominance or humor, a partner who complements their spouse has traits that the other lacks. For example, one partner may be good at organization, whilst the other is poor at the organization but very good at entertaining guests.

Kerchoff and Davis found that this level of the filter was the most important for couples who had been together for more than 18 months. This may be the origin of the classic phrase “opposites attract,” though we may add the condition “although not for the first 18 months of the relationship.

This theory may be interpreted as similar to the matching hypothesis but for personality rather than physical traits.

Some stages of this model may now be seen as less relevant; for example, as modern society is much more multicultural and interconnected (by things such as the internet) than in the 1960s, we may now see social demography as less of a barrier to a relationship. This may lead to the criticism that the theory lacks temporal validity.

This lack of temporal validity is supported by Levinger (1978), who, even only 16 years after the study, pointed out that many studies had failed to replicate Karchkoff and Davis’ original findings, although this may be down to methodological issues with operationalizing factor such as the success of a relationship or complementarity of traits.

Again, investigating the second and third levels of the filter theory looks at correlation which cannot easily explain causality. Both Davis and Rusbult (2001) and Anderson et al. (2003) found that people become more similar in different ways the more time that they spend in a relationship together.

So it may be that the relationship leads to an alignment of attitudes and also a greater complementarity as couples assign each other roles: “He does the cooking, and I do the hoovering.”

Theories of Romantic Relationships

Social exchange theory.

This is an economic theory of romantic relationships. Many psychologists believe that the key to maintaining a relationship is that it is mutually beneficial.

Psychologists Thibault and Kelley (1959) proposed the Social Exchange Theory , which stipulates that one motivation to stay in a romantic relationship, and a large factor in its development, is the result of a cost-benefit analysis that people perform, either consciously or unconsciously.

Thibaut and Kelley assume that people try to maximize the rewards they obtain from a relationship and minimize the costs (the minimax principle).

In a relationship, people gain rewards (such as attention from their partner, sex, gifts, and a boost to their self-esteem) and incur costs (paying money for gifts, compromising on how to spend their time or stress).

There is also an opportunity cost in relationships, as time spent with a partner that does not develop into a lasting relationship could have been spent with another partner with better long-term prospects.

How much value is placed on each cost and benefit is subjective and determined by the individual. For example, whilst some people may want to spend as much time as possible with their partner in the early stages of the relationship and see this time together as a reward of the relationship, others may value their space and see extended periods spent together as more of a necessary investment to keep the other person happy.

Thibault and Kelley also identified a number of different stages of a relationship which progress from the sampling stage, where couples experiment with the potential costs and rewards of a relationship through direct or indirect interactions, through the bargaining and commitment stages as negotiations of each partner’s role in the relationship occur.

The rewards and costs are established and become more predictable, and finally arriving at the institutionalization stage, where the couple is settled. The norms of the relationship are heavily embedded.

Comparison Levels (CL) and (CLalt)

The comparison level (CL) in a relationship is a judgment of how much profit an individual is receiving (benefits minus costs). The acceptable CL needed to continue to pursue a relationship changes as a person matures and can be affected by a number of external and internal factors.

External factors may include the media (younger people may want more from a relationship after being socialized by images of romance on films and television), seeing friends and families in relationships (people who have divorced or separated parents may have a different CL to those with parents who are still married), or experiences from prior relationships, which have taught the person to expect more or less from a partner. Internal perceptions of self-worth, such as self-esteem, will directly affect the CL that a person believes they are entitled to in a relationship.

CLalt stands for the Comparison Level for Alternatives and refers to a person’s judgment of if they could be getting fewer costs and greater rewards from another alternative relationship with another partner. Steve Duck (1994) suggested that a person’s CLalt is dependent on the level of reward and satisfaction in their current relationship. If the CL is positive, then the person may not consider the potential benefits of a relationship with another person.

Operationalizing rewards and costs are hugely subjective, making comparisons between people and relationships in controlled settings very difficult. Most studies that are used to support Social Exchange Theory account for this by using artificial procedures in laboratory settings, reducing the external validity of the findings.

Michael Argyle (1987) questions whether it is the CL that leads to dissatisfaction with the relationship or dissatisfaction which leads to this analysis. It may be that Social Exchange Theory serves as a justification for dissatisfaction rather than the cause of it.

Social Exchange Theory ignores the idea of social equity explained by the next relationship theory concerning equality in a relationship – would a partner really feel satisfied in a relationship where they received all of the rewards and their partner incurred all of the costs?

Real-world application – Social Exchange Theory is used in Integrated Behavioural Couples Therapy where couples are taught how to increase the proportion of positive exchanges and decrease negative exchanges – This shows high mundane realism in terms of the practical, real-world application of the theory therefore, SET is really beneficial at improving real relationships.

Equity Theory

This is an economic theory of romantic relationships. Equity means fairness.

Equity Theory (Walster ‘78) is an extension of Social Exchange Theory but argues that rather than simply trying to maximize rewards/minimize losses. Couples will experience satisfaction in their relationship if there is an equal ratio of rewards to losses between both partners: i.e., there is equity/fairness.

If one partner is benefiting from more profit (benefits-costs) than the other, then both partners are likely to feel unsatisfied.

If one partner’s reward: loss ratio is far greater than their partner’s, they may experience guilt or shame (they are giving nothing and getting lots in return).

If one partner’s reward: loss ratio is far lower than their partner’s, they may experience anger or resentment (they are giving a lot and getting little in return).

A partner who feels that they are receiving less profit in an inequitable relationship may respond by either working hard to make the relationship more equitable or by shifting their own perception of rewards and costs to justify the relationship continuing.

Principles of equity theory:

- Distribution – Trade-offs and compensations are negotiated to achieve fairness in a relationship e.g., one partner may cook and the other may clean; each has their own role.

- Dissatisfaction – The greater the perceived inequity, the greater the dissatisfaction e.g., someone who over-benefits in their relationship will feel guilty, and one who under-benefits will feel angry.

- Realignment – The more unfair the relationship feels, the harder the partner will work to restore equity. Or they may revise their perceptions of rewards and costs, e.g., what was once seen as a cost (abuse, infidelity) is now accepted as the norm.

Huseman et al. (1987) suggested that individual differences are an important factor in equity theory. They make a distinction between entitleds who feel that they deserve to gain more than their partner in a relationship and benevolents who are more prepared to invest by working harder to keep their partner happy.

Clark and Mills (2011) argue that we should differentiate between the role of equity in romantic relationships and other types of relationships, such as business or casual, friendly relationships. They found in a meta-analysis that there is more evidence that equity is a deciding factor in non-romantic relationships, the evidence being more mixed in romantic partnerships.

Social Equity Theory does not apply to all cultures; couples from collectivist cultures (where the group needs are more important than those of the individual) were more satisfied when over-benefitting than those from individualistic cultures (where the needs of the individual are more important than those of the individual) in a study conducted by Katherine Aumer-Ryan et al. (2007).

Some cultures have traditions and expectations that one member of a romantic relationship should benefit more from the partnership. The traditional nuclear family, typical in the early to mid-20th century, was patriarchal, and the woman was often expected to contribute to more tasks, such as housework and raising the children, than the man for whom providing money to the family was perceived to be the primary role.

Rusbult’s Investment Model

Rusbult et al.’s (2011) model of commitment in a romantic relationship builds upon the Social Exchange Theory discussed above and proposes that three factors contribute to the level of commitment in a relationship.

Satisfaction level . The sum total of positive and negative emotions experienced and how much each partner fulfills the other’s needs (financial, sexual, etc.)

Investment size . This relates to the number of investments made in the relationship to date in terms of time, money, and effort, which would be lost if the relationship stopped. Investments increase dependency on the relationship due to the costs caused by the loss of what has been invested. Therefore, investments are a powerful influence in preventing relationship breakdown.

Commitment level . This refers to the likelihood the relationship will continue. In new romantic relationships, partners tend to have high levels of commitment as they have (i) high levels of satisfaction, (ii) they would lose a lot if the relationship ended, (iii) they don’t expect any gains, (iv) they tend not to be interested in alternative relationships. However, as the relationship continues, these factors may change, resulting in lower levels of commitment.

Le and Agnew’s (2003) meta-analysis of studies relating to similar investment models found that satisfaction, comparison with alternatives, and investment were all strong indicators of commitment to a relationship. This importance was the same across cultures and genders and also applied to homosexual relationships.

Many of the studies relating to an investment in relationships rely on self-report techniques. Whilst this would be perceived as a less reliable and overly-subjective method in other areas when looking at the amount an individual feels they are committed to a relationship, their own opinion and the value that they place on behaviors and attributes are more relevant than objective observations.

Again, investment models tend to give correlational data rather than causal; it may be that a commitment established at an earlier stage leads inevitably to the partner viewing comparisons more favorably and investing more into the relationship.

Rusbult’s investment model has important real-world applications in that it can help explain why partners suffering abuse continue to stay in abusive relationships – although satisfaction may be very low, investment size (for example, children) may be very high, and they may lack alternative potential partners.

Rusbult (1995) found that for women living in a shelter for abused women, lack of alternatives and high investment were the major factors underlying why women returned to abusive relationships.

Duck’s Phase Model

Duck’s (2007) phase model suggests that the breakdown of a relationship is not a single event but rather a system of stages or phases in which a couple progresses, incorporating the end of the relationship.

Intra-Psychic Phase

Literally ‘within one’s own mind.’ In this phase, one of the partners begins to have doubts about the relationship. They spend time thinking about the pros and cons of the relationship and possible alternatives, including being alone. They may either internalize these feelings or confide in a trusted friend.

Dyadic Phase

The partners discuss their feelings about the relationship; this usually leads to hostility and may take place over a number of days or weeks. Over this period, the discussions will often focus on the equity in the relationship and will either culminate in a renewed resolution to invest in the relationship or the realization that the relationship has broken down.

Social Phase

Other people are involved in the process; friends are encouraged to choose a side and may urge for reconciliation with their partner or may encourage the breakdown through the expression of opinion or hidden facts (“I heard they did this…”). Each partner may seek approval from their friends at the expense of their previous romantic partner. At this point, the relationship is unlikely to be repaired as each partner has invested in the breakdown to their friends, and any retreat from this may be met with disapproval.

Grave-Dressing Phase

When the relationship has completely ended, each partner will seek to create a favorable narrative of the events, justifying to themselves and others why the relationship breakdown was not their fault, thus retaining their social value and not lowering their chances of future relationships.

Their internal narrative will focus more on processing the events of the relationship, perhaps reframing memories in the context of new discoveries about the partner. For example, an initial youthfulness may now be seen as immaturity.

Duck’s model may be a relevant description of the breakdown of relationships, but it does not explain what leads to the initial stages of the model, which other models of relationships discussed earlier attempt to do.

Duck’s phase model has useful real-life applications. When relationship therapists can identify the phase of a breakdown that a couple are in, they can identify strategies that target the issues at that particular stage. Duck (1994) recommends that couples in the intra-psychic phase should be encouraged to think about the positive rather than the negative aspects of their partner.

Rollie and Duck (2006) added a fifth stage to the model, the resurrection phase, where people take the experiences and knowledge gained from the previous relationship and apply it to future relationships they have. When Rollie and Duck revisited the model, they also emphasized that progression from one stage to the next is not inevitable and effective interventions can prevent this.

Virtual Relationships in Social Media

The development of social media sites since Facebook launched in 2004 has meant that people can initiate, maintain and dissolve relationships online without ever physically meeting the other person.

Research indicates important differences in the way in which people conduct virtual relationships compared to face-to-face relationships in terms of:

Self-Disclosure

This tends to vary according to whether the individual feels they are presenting information privately (e.g., private messaging) or publicly (e.g., their Facebook account). Disclosures to a public audience where the author’s identity is known are usually heavily edited.

Disclosures to ‘private’ audiences, particularly when the author’s identity is anonymous, are often marked by quicker and more revealing disclosures.

Online anonymity means that people do not fear the negative social consequences of disclosure in that they will not be judged negatively/punished for what would normally be judged as socially inappropriate disclosures.

Rubin (’75) found a similar phenomenon when studying personal disclosure of information in normal relationships, with people being far more likely to disclose highly personal information to strangers as they knew (a) they would probably never see the person again and (b) the stranger could not report disclosures to the individual’s social group.

Absence of Gating

A gate is any feature/obstacle that could interfere with the development of a relationship.

Gating in relationships refers to a peripheral feature becoming a barrier to the connection between people. This gate could be a physical feature, such as somebody’s weight or disfigurement, or a feature of one’s personality, such as introversion or shyness.

It may be that two people’s personalities are very compatible, and attraction would occur if they spoke for any length of time, but a gate prevents this from happening.

In face-to-face relationships, various factors influence the likelihood of a relationship starting in the 1st place: e.g., geographic location, social class, ethnicity, attractiveness, etc. These ‘gates’ are not present in virtual relationships and, in fact, people may mislead others online to form a false impression of their true identity: e.g., fake/photoshopped photos, females posing as males, etc.

McKenna and Bargh (1999) propose the idea that CmC relationships remove these gates and mean that there is little distraction from the connection between people that might not otherwise have occurred. Some people use the anonymity available on the internet to compensate for these gates by portraying themselves differently than they would do in FtF relationships.

People who lack confidence may use the extra time available in messaging to consider their responses more carefully, and those who perceive themselves to be unattractive may choose an avatar or edited picture which does not show this trait.

Gender bias – Theory assumes that gates affect people in the same way, but age and level of physical attractiveness are probably more gating factors for females seeking male partners than males seeking female partners – Research has suffered from a beta bias and oversimplified how gates are used in virtual relationships and are therefore less valid.

Zhao (2008) found that Facebook users often present highly edited, fictional representations of their true identity, presenting a false version of their ‘ideal’ self which they consider more likely to be attractive to others. Yurchisin (’05) interviewed online daters and found that although people would ‘stretch’ the truth about their true selves, they did not present completely imaginary identities to others for fear of rejection and ridicule if and when they met someone for a physical date.

Baker (2010) found that online relationships allowed shy people to overcome the lack of confidence that normally prevented them from forming face-to-face relationships. A survey of 207 male and female students found that high shyness and use of Facebook scores correlated with a higher perception of friend quality.

Low shyness and high Facebook use were not correlated with friendship quality. This seems to indicate that shy people may find virtual relationships particularly rewarding, presumably as the negative emotions brought about by face-to-face relationships are lessened or removed.

McKenna (2000) surveyed 568 internet users and found that just under 10% had gone on to physically meet friends who they had met online, and just over 10% had talked on the phone. After a 2-year gap, 57% revealed that their virtual relationship had increased intimacy. In terms of romantic relationships, 70% lasted 2 years or more compared to only 50% of relationships formed face-to-face.

A current danger in society relates to individuals assuming false identities online to deceive others into disclosing private information/images and then, possibly, blackmailing the individual who disclosed. School-delivered and online awareness campaigns aim to highlight the dangers of disclosing too much and putting trust in online relationships that may turn out to be based on false identities and/or dangerous/exploitative.

Parasocial Relationships

Levels of Parasocial Relationships

Parasocial relationships are one-sided relationships where one partner is unaware that they are apart of it.

Parasocial relationships may be described as those which are one-sided, Horton and Wohl (1956) defined them as relationships where the ‘fan’ is extremely invested in the relationships but the celebrity is unaware of their existence.

Parasocial relationships may occur with any dynamic which elevates someone above the population in a community, making it difficult for genuine interaction; this could be anyone from fictitious characters to teachers.

PSRs are usually directed toward media figures (musicians, bloggers, TV presenters, etc.). The object of the PSR becomes a meaningful figure in the individual’s life, and the ‘relationship’ may occupy a lot of the individual’s time.

PSRs are often formed because the individual lacks the social skills or opportunities to form a real relationship. PSRs do not involve risks present in real relationships, such as criticism or rejection.

PSRs are likely to form because the individual views the object of the PSR as (i) attractive and (ii) similar to themselves.

The Attachment Theory Explanation

Bowlby’s theory of attachment suggests that those who do not have a secure attachment earlier in life will have emotional difficulties and attachment disorders when they grow up.

Parasocial relationships are often associated with teenagers and young adults who may have had less genuine relationships to build an internal working model which allows them to recognize parasocial relationships as abnormal.

For example, it may be that those with insecure resistant attachment types are drawn to parasocial relationships because they do not offer the threat of rejection or abandonment.

The Absorption-Addiction Model

McCutcheon (2002) proposed that parasocial relationships form due to deficiencies in people’s lives. They look to the relationship to escape from reality, perhaps due to traumatic events or to fill the gap left by a real-life attachment ending.

Absorption refers to behavior designed to make the person feel closer to the celebrity. This could be anything from researching facts about them, both their personal life and their career, to repeatedly experiencing their work, playing their music or buying tickets to see them live, or paying for their merchandise to strengthen the apparent relationship.

As with other Addictions, this refers to the escalation of behavior to sustain and strengthen the relationship. The person starts to believe that the ‘need’ for the celebrity and behaviors become more extreme and more delusional. Stalking is a severe example of this behavior.

The absorption-addiction model can be viewed as more of a description of parasocial relationships than an explanation; it states how a parasocial relationship may be identified and the form it may take, but not what it is caused by.

Methodologically, many studies into parasocial relationships, such as Maltby’s 2006 survey, rely on the self-report technique. This can often lack validity, whether this is due to accidental inaccuracies, due to a warped perception of the parasocial relationship by the participant, genuine memory lapses, or more deliberate actions.

For example, the social desirability bias makes the respondents under-report their abnormal behavior. There is often competition between fans of celebrities to see who is the ‘biggest’ fan, which may lead to an exaggeration of the behaviors and attitudes when reporting the relationship.

McCutcheon et al. (2006) used 299 participants to investigate the links between attachment types and attitudes toward celebrities. They found no direct relationship between the type of attachment and the likelihood that a parasocial relationship will be formed.

Portrays a negative view of human behavior – PSRs are portrayed as psychopathological behavior like calling them ‘borderline pathological’ – Theory may be socially sensitive as it implies that such behavior is a bad thing when it may actually provide support for those who struggle with real-life relationships, it may be more appropriate to adopt a positive, humanistic approach.

Altman, I., Taylor, D. A., & Actman, I. (1973). Social penetration: The development of interpersonal relationships (2nd ed.) . New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Anderson, C., Keltner, D., & John, O. P. (2003). Emotional convergence between people over time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(5) , 1054–1068. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1054

Aron, A., Melinat, E., Aron, E. N., Vallone, R. D., & Bator, R. J. (1997). The experimental generation of interpersonal closeness: A procedure and some preliminary findings. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(4) , 363–377. doi:10.1177/0146167297234003

Buss, D. M. (1989). Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 12(01) , 1. doi:10.1017/s0140525x00023992

Clark, R. (1989). Gender differences in receptivity to sexual offers. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 2(1) , 39–55. doi:10.1300/j056v02n01_04

Davis, J. L., & Rusbult, C. E. (2001). Attitude alignment in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(1) , 65–84. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.81.1.65

Dion, K., Berscheid, E., & Walster, E. (1972). What is beautiful is good. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 24(3) , 285–290. doi:10.1037/h0033731

Feingold, A. (1988). Matching for attractiveness in romantic partners and same-sex friends: A meta-analysis and theoretical critique. Psychological Bulletin, 104(2) , 226–235. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.104.2.226

Flanagan, C., Berry, D., & Jarvis, M. (2016). AQA psychology for A level year 2 – student book . United Kingdom: Illuminate Publishing.

Gallagher, M., Nelson, R., J, Y., & Weiner, I. B. (2003). Handbook of psychology: V. 3: Biological psychology . New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Huston, T. L., & Levinger, G. (1978). Interpersonal attraction and relationships. Annual Review of Psychology, 29(1) , 115–156. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.29.020178.000555

Kerckhoff, A. C., & Davis, K. E. (1962). Value consensus and need Complementarity in mate selection. American Sociological Review,27(3) , 295. doi:10.2307/2089791

Landy, D., & Aronson, E. (1969). The influence of the character of the criminal and his victim on the decisions of simulated jurors. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 5(2) , 141–152. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(69)90043-2

Little, A. C., & Jones, B. C. (2003). Evidence against perceptual bias views for symmetry preferences in human faces. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 270(1526) , 1759–1763. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2445

Singh, D. (1993). Adaptive significance of female physical attractiveness: Role of waist-to-hip ratio. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(2) , 293–307. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.65.2.293

Sprecher, S., & Hendrick, S. S. (2004). Self-disclosure in intimate relationships: Associations with individual and relationship characteristics over time. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology,23(6) , 857–877. doi:10.1521/jscp.23.6.857.54803

Walster, E., Aronson, V., Abrahams, D., & Rottman, L. (1966). Importance of physical attractiveness in dating behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4(5) , 508–516. doi:10.1037/h0021188

Waynforth, D., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (1995). Conditional mate choice strategies in humans: Evidence from ‘lonely hearts’ advertisements. behavior, 132(9) , 755–779. doi:10.1163/156853995×001 andura’s Bobo Doll studies are laboratory experiments and therefore criticizable on the grounds of lacking ecological validity.’

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

IResearchNet

Matching Hypothesis

Matching hypothesis definition.

The matching hypothesis refers to the proposition that people are attracted to and form relationships with individuals who resemble them on a variety of attributes, including demographic characteristics (e.g., age, ethnicity, and education level), personality traits, attitudes and values, and even physical attributes (e.g., attractiveness).

Background and Importance of Matching Hypothesis

Evidence for Matching Hypothesis

There is ample evidence in support of the matching hypothesis in the realm of interpersonal attraction and friendship formation. Not only do people overwhelmingly prefer to interact with similar others, but a person’s friends and associates are more likely to resemble that person on virtually every dimension examined, both positive and negative.

The evidence is mixed in the realm of romantic attraction and mate selection. There is definitely a tendency for men and women to marry spouses who resemble them. Researchers have found extensive similarity between marital partners on characteristics such as age, race, ethnicity, education level, socioeconomic status, religion, and physical attractiveness as well as on a host of personality traits and cognitive abilities. This well-documented tendency for similar individuals to marry is commonly referred to as homogamy or assortment.

The fact that people tend to end up with romantic partners who resemble them, however, does not necessarily mean that they prefer similar over dissimilar mates. There is evidence, particularly with respect to the characteristic of physical attractiveness, that both men and women actually prefer the most attractive partner possible. However, although people might ideally want a partner with highly desirable features, they might not possess enough desirable attributes themselves to be able to attract that individual. Because people seek the best possible mate but are constrained by their own assets, the process of romantic partner selection thus inevitably results in the pairing of individuals with similar characteristics.

Nonetheless, sufficient evidence supports the matching hypothesis to negate the old adage that “opposites attract.” They typically do not.

References:

- Berscheid, E., & Reis, H. T. (1998). Attraction and close relationships. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (4th ed., pp. 193-281). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Kalick, S. M., & Hamilton, T. E. (1996). The matching hypothesis re-examined. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 673-682.

- Murstein, B. I. (1980). Mate selection in the 1970s. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 42, 777-792.

Matching hypothesis

Mate selection by social desirability / from wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, dear wikiwand ai, let's keep it short by simply answering these key questions:.

Can you list the top facts and stats about Matching hypothesis?

Summarize this article for a 10 year old

The matching hypothesis (also known as the matching phenomenon ) argues that people are more likely to form and succeed in a committed relationship with someone who is equally socially desirable, typically in the form of physical attraction . [1] The hypothesis is derived from the discipline of social psychology and was first proposed by American social psychologist Elaine Hatfield and her colleagues in 1966. [2]

Successful couples of differing physical attractiveness may be together due to other matching variables that compensate for the difference in attractiveness. [3] For instance, some men with wealth and status desire younger, more attractive women. Some women are more likely to overlook physical attractiveness for men who possess wealth and status. [3] [4]

It is also similar to some of the theorems outlined in uncertainty reduction theory , from the post-positivist discipline of communication studies . These theorems include constructs of nonverbal expression, perceived similarity, liking, information seeking, and intimacy, and their correlations to one another. [5]

Module 12: Attraction

Module Overview

It was important to end the book on a positive note. So much of what is researched in social psychology has a negative connotation to it such as social influence, persuasion, prejudice, and aggression. Hence, we left attraction to the end. We start by discussing the need for affiliation and how it develops over time in terms of smiling, play, and attachment. We will discuss loneliness and how it affects health and the related concept of social rejection. We will then discuss eight factors on attraction to include proximity, familiarity, beauty, similarity, reciprocity, playing hard to get, and intimacy. The third section will cover types of relationships and love. Finally, relationship issues are a part of life and so we could not avoid a discussion of the four horsemen of the apocalypse. No worries. We end the module, and book, with coverage of the beneficial effects of forgiveness.

Module Outline

12.1. The Need for Affiliation

12.2. factors on attraction, 12.3. types of relationships, 12.4. predicting the end of a relationship.

Module Learning Outcomes

- Describe the need for affiliation and the negative effects of social rejection and loneliness.

- Clarify factors that increase interpersonal attraction between two people.

- Identify types of relationships and the components of love.

- Describe the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse as they relate to relationship conflicts, how to resolve them, and the importance of forgiveness.

Section Learning Objectives

- Define interpersonal attraction.

- Define the need for affiliation.

- Report what the literature says about the need for affiliation.

- Define loneliness and identity its types.

- Describe smiling and how it relates to affiliation.

- Describe play and how it relates to affiliation.

- Define attachment.

- List and describe the four types of attachment.

- Clarify how attachment to parent leads to an attachment to God.

- Describe the effect of loneliness on health.

- Describe social rejection and its relation to affiliation.

12.1.1. Defining Key Terms

Have you ever wondered why people are motivated to spend time with some people over others, or why they chose the friends and significant others they do? If you have, you have given thought to interpersonal attraction or showing a preference for another person (remember, inter means between and so interpersonal is between people).

This relates to the need to affiliate/belong which is our motive to establish, maintain, or restore social relationships with others, whether individually or through groups (McClelland & Koestner, 1992). It is important to point out that we affiliate with people who accept us though are generally indifferent while we tend to belong to individuals who truly care about us and for whom we have an attachment. In terms of the former, you affiliate with your classmates and people you work with while you belong to your family or a committed relationship with your significant other or best friend. The literature shows that:

- Leaders high in the need for affiliation are more concerned about the needs of their followers and engaged in more transformational leadership due to affiliation moderating the interplay of achievement and power needs (Steinmann, Otting, & Maier, 2016).

- Who wants to take online courses? Seiver and Troja (2014) found that those high in the need for affiliation were less, and that those high in the need for autonomy were more, likely to want to take another online course. Their sample included college students enrolled in classroom courses who had taken at least one online course in the past.

- Though our need for affiliation is universal, it does not occur in every situation and individual differences and characteristics of the target can factor in. One such difference is religiosity and van Cappellen et al. (2017) found that religiosity was positively related to social affiliation except when the identity of the affiliation target was manipulated to be a threatening out-group member (an atheist). In this case, religiosity did not predict affiliation behaviors.

- Risk of exclusion from a group (not being affiliated) led individuals high in a need for inclusion/affiliation to engage in pro-group, but not pro-self, unethical behaviors (Thau et al., 2015).

- When affiliation goals are of central importance to a person, they perceive the estimated interpersonal distance between them and other people as smaller compared to participants primed with control words (Stel & van Koningsbruggen, 2015).

Loneliness occurs when our interpersonal relationships are not fulfilling and can lead to psychological discomfort. In reality, our relationships may be fine and so our perception of being alone is what matters most and can be particularly troublesome for the elderly. Tiwari (2013) points out that loneliness can take three forms. First, situational loneliness occurs when unpleasant experiences, interpersonal conflicts, disaster, or accidents lead to loneliness. Second, developmental loneliness occurs when a person cannot balance the need to relate to others with a need for individualism, which “results in loss of meaning from their life which in turn leads to emptiness and loneliness in that person.” Third, internal loneliness arises when a person has low self-esteem and low self-worth and can be caused by locus of control, guilt or worthlessness, and inadequate coping strategies. Tiwari writes, “Loneliness has now become an important public health concern. It leads to pain, injury/loss, grief, fear, fatigue, and exhaustion. Thus, it also makes a person sick and interferes in day to day functioning and hampers recovery…. Loneliness with its epidemiology, phenomenology, etiology, diagnostic criteria, adverse effects, and management should be considered a disease and should find its place in classification of psychiatric disorders.”

What do you think? Is loneliness a disease, needing to be listed in the DSM?

12.1.2. Development of Affiliation and Attachment

12.1.2.1. Smiling and affiliation. As early as 6-9 weeks after birth, children smile reliably at things that please them. These first smiles are indiscriminate, smiling at almost anything they find amusing. This may include a favorite toy, mobile over their crib, or even another person. Smiles directed at other people are called social smiles . Like smiles directed at inanimate objects, they too are indiscriminate at first but as the infant gets older, come to be reserved for specific people. These smiles fade away if the adult is unresponsive. Smiling is also used to communicate positive emotion and children become sensitive to the emotional expressions of others.

This indiscriminateness of their smiling ties in with how they perceive strangers. Before 6 months of age, they are not upset about the presence of people they do not know. As they learn to anticipate and predict events, strangers cause anxiety and fear. This is called stranger anxiety . Not all infants respond to strangers in the same way though. Infants with more experience show lower levels of anxiety than infants with little experience. Also, infants are less concerned about strangers who are female and those who are children. The latter probably has something to do with size as adults may seem imposing to children.

Important to stranger anxiety is the fact that children begin to figure people out or learn to detect emotion in others. They come to discern vocal expressions of emotion before visual ones, mostly due to their limited visual abilities early on. As vision improves and they get better at figuring people out, social referencing emerges around 8-9 months. When a child is faced with an uncertain circumstance or event, such as the presence of a stranger, they will intentionally search for information about how to act from a caregiver. So, if a stranger enters the room, an infant will look to its mother to see what her emotional reaction is. If the mother is happy or neutral, the infant will not become anxious. However, if the mother becomes distressed, the infant will respond in kind. Outside of dealing with strangers, infants will also social reference a parent if they are given an unusual toy to play with. If the parent is pleased with the toy, the child will play with it longer than if the parent is displeased or disgusted.

12.1.2.2. Play and affiliation. Children are also motivated to engage in play. Up to about 1.5 years of age, children play alone called solitary play . Between 1 ½ and 2 years of age, children play side-by-side, doing the same thing or similar things, but not interacting with each other. This is called parallel play . Associative play occurs next and is when two or more children interact with one another by sharing or borrowing toys or materials. They do not do the same thing though. Around 3 years of age, children engage in cooperative play which includes games that involve group imagination such as “playing house.” Finally, onlooker play is an important way for children to participate in games or activities they are not already engaged in. They simply wait for the right moment to jump in and then do so. Though play develops across time, or becomes more complex, solitary play and onlooker play do remain options children reserve for themselves. Sometimes we just want to play a game by ourselves and not have a friend split the screen with us, as in the case of video games and if they are on the couch next to you.

12.1.2.3. Attachment and affiliation, to people and God. Attachment is an emotional bond established between two individuals and involving one’s sense of security. Our attachments during infancy have repercussions on how we relate to others the rest of our lives. Ainsworth et al. (1978) identified three attachment styles an infant possesses. The first is a secure attachment and results in the use of a mother as a home base to explore the world. The child will occasionally return to her. She also becomes upset when she leaves and goes to the mother when she returns. Next is the avoidantly attached child who does not seek closeness with her and avoids the mother after she returns. Finally, is the ambivalent attachment in which the child displays a mixture of positive and negative emotions toward the mother. She remains relatively close to her which limits how much she explores the world. If the mother leaves, the child will seek closeness with the mother all the while kicking and hitting her.

A fourth style has been added due to recent research. This is the disorganized-disoriented attachment style which is characterized by inconsistent, often contradictory behaviors, confusion, and dazed behavior (Main & Solomon, 1990). An example might be the child approaching the mother when she returns, but not making eye contact with her.

The interplay of a caregiver’s parenting style and the child’s subsequent attachment to this parent has long been considered a factor on the psychological health of the person throughout life. For instance, father’s psychological autonomy has been shown to lead to greater academic performance and fewer signs of depression in 4th graders (Mattanah, 2001). Attachment is also important when the child is leaving home for the first time to go to college. Mattanah, Hancock, and Brand (2004) showed in a sample of four hundred four students at a university in the Northeastern United States that separation individuation mediated the link between secure attachment and college adjustment. The nature of adult romantic relationships has been associated with attachment style in infancy (Kirkpatrick, 1997). One final way this appears in adulthood is through a person’s relationship with a god figure.

An extrapolation of attachment research is that we can perceive God’s love for the individual in terms of a mother’s love for her child, but this attachment is not always to God. For instance, Protestants, seeing God as distant, use Jesus to form an attachment relationship while Catholics utilize Mary as their ideal attachment figure. It could be that negative emotions and insecurity in relation to God do not always signify the lack of an attachment relationship, but maybe a different type of pattern or style (Kirkpatrick, 1995). Consider that an abused child still develops an attachment to an abusive mother or father. The same could occur with God and may well explain why images of vindictive and frightening gods have survived through human history.

One important thing to note is that in human relationships, the other person’s actions can affect the relationship, for better or worse. Perceived relationships with God do not have this quality. As God cannot affect us, we cannot affect Him. This allows the person to invent or reinvent the relationship with God in secure terms without allowing counterproductive behaviors to retard progress. Hence, Kirkpatrick (1995) says people “with insecure attachment histories might be able to find in God…the kind of secure attachment relationship they never had in human interpersonal relationships (p. 62).” The best human attachment figures are ultimately fallible while God is not limited by this.

Pargament (1997) defined three styles of attachment to God. First is the ‘secure’ attachment in which God is viewed as warm, receptive, supportive, and protective, and the person is very satisfied with the relationship. Next is the ‘avoidant attachment’ in which God is seen as impersonal, distant, and disinterested, and the person characterizes the relationship as one in which God does not care about him or her. Finally, is the ‘anxious/ambivalent’ attachment. Here, God seems to be inconsistent in His reaction to the person, sometimes warm and receptive and sometimes not. The person is not sure if God loves him or not. We might say that the God of the secure attachment is the authoritative parent, the God of the avoidant attachment is authoritarian, and the God of the anxious/ambivalent attachment is permissive.

Kirkpatrick and Shaver (1990) note that attachment and religion may be linked in important ways. They offer a “ compensation hypothesis ” which states that insecurely attached individuals are motivated to compensate for the absence of this secure relationship by believing in a loving God. Their study evaluated the self-reports of 213 respondents (180 females and 33 males) and found that the avoidant parent-child attachment relationship yielded greater levels of adult religiousness while those with secure attachment had lower scores. The avoidant respondents were also four times as likely to have experienced a sudden religious conversion.

They also remind the reader that the child uses the attachment figure as a haven and secure base, and go on to note that there is ample evidence to suggest the same function for God. Bereaved persons become more religious, soldiers pray in foxholes, and many who are in emotional distress turn to God. Further, Christianity has a plethora of references to God being by one’s side always and the person having a friend in Jesus.

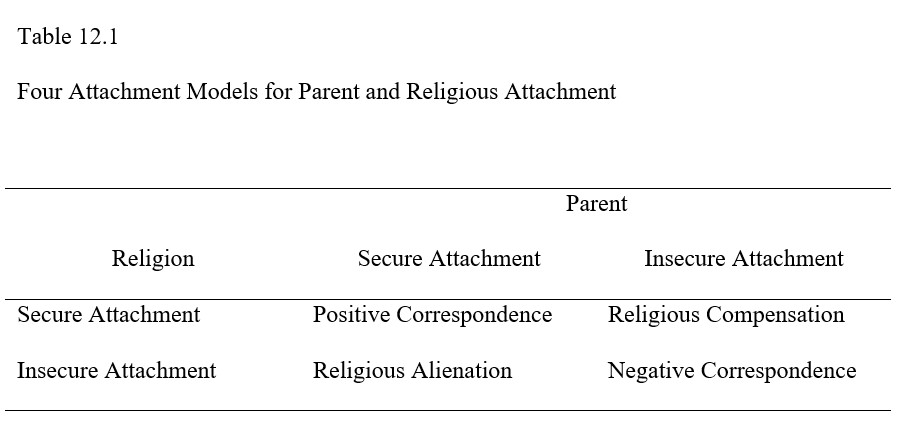

Pargament (1997) expanded upon the compensation hypothesis and showed that the relationship between attachment history and religious beliefs is far from simple. He summarized four relationships between parental and religious attachments extrapolated from Kirkpatrick’s research. First, if a child had a secure attachment to the parent, he may develop a secure attachment to religion, called ‘ positive correspondence .’ In this scenario, the result of a loving and trusting relationship with one’s parents is transferred to God as well. This is contrary to the findings of Kirkpatrick and Shaver (1990) which said that securely attached individuals displayed lower levels of religiosity. More in line with their view is Pargament’s second category, secure attachment to parents and insecure attachment to religion, called ‘ religious alienation .’ Here the person who had a secure attachment to parents may not feel the need to believe in God. He does not need to compensate for any deficiencies.

The third category is also in line with Kirkpatrick and Shaver’s study. Modeled after their hypothesis, ‘ religious compensation ’ results from an insecure attachment to parents and a secure attachment to religion. Finally, an insecure attachment to parents may yield an insecure attachment to religion called ‘ negative correspondence ’ (see Table 12.1). These insecure parental ties have left the person unequipped to build neither strong adult attachments nor a secure spiritual relationship. The person may cling to “false gods” like drug and alcohol addiction, food addiction, religious dogmatism, a religious cult, or a codependent relationship.

12.1.3. Health Factors

“ Loneliness kills.” These were the opening words of a March 18, 2015 Time article describing alarming research which shows that loneliness increases the risk of death. How so? According to the meta-analysis of 70 studies published from 1980 to 2014, social isolation increases mortality by 29%, loneliness does so by 26%, and living alone by 32%; but being socially connected leads to higher survival rates (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015). The authors note, as did Tiwari (2013) earlier, that social isolation and loneliness should be listed as a public health concern as it can lead to poorer health and decreased longevity, as well as CVD (coronary vascular disease; Holt-Lunstad & Smith, 2016). Other ill effects of loneliness include greater stimulated cytokine production due to stress which in turn causes inflammation (Jaremka et al., 2013); greater occurrence of suicidal behavior (Stickley & Koyanagi, 2016); pain, depression, and fatigue (Jarema et al., 2014); and psychotic disorders such as delusional disorders, depressive psychosis, and subjective thought disorder (Badcock et al., 2015).