- Open access

- Published: 11 May 2018

The Syrian conflict: a case study of the challenges and acute need for medical humanitarian operations for women and children internally displaced persons

- Rahma Aburas 1 ,

- Amina Najeeb 2 ,

- Laila Baageel 3 &

- Tim K. Mackey ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2191-7833 3 , 4 , 5

BMC Medicine volume 16 , Article number: 65 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

26k Accesses

28 Citations

20 Altmetric

Metrics details

After 7 years of increasing conflict and violence, the Syrian civil war now constitutes the largest displacement crisis in the world, with more than 6 million people who have been internally displaced. Among this already-vulnerable population group, women and children face significant challenges associated with lack of adequate access to maternal and child health (MCH) services, threatening their lives along with their immediate and long-term health outcomes.

While several health and humanitarian aid organizations are working to improve the health and welfare of internally displaced Syrian women and children, there is an immediate need for local medical humanitarian interventions. Responding to this need, we describe the case study of the Brotherhood Medical Center (the “Center”), a local clinic that was initially established by private donors and later partnered with the Syrian Expatriate Medical Association to provide free MCH services to internally displaced Syrian women and children in the small Syrian border town of Atimah.

Conclusions

The Center provides a unique contribution to the Syrian health and humanitarian crisis by focusing on providing MCH services to a targeted vulnerable population locally and through an established clinic. Hence, the Center complements efforts by larger international, regional, and local organizations that also are attempting to alleviate the suffering of Syrians victimized by this ongoing civil war. However, the long-term success of organizations like the Center relies on many factors including strategic partnership building, adjusting to logistical difficulties, and seeking sustainable sources of funding. Importantly, the lessons learned by the Center should serve as important principles in the design of future medical humanitarian interventions working directly in conflict zones, and should emphasize the need for better international cooperation and coordination to support local initiatives that serve victims where and when they need it the most.

Peer Review reports

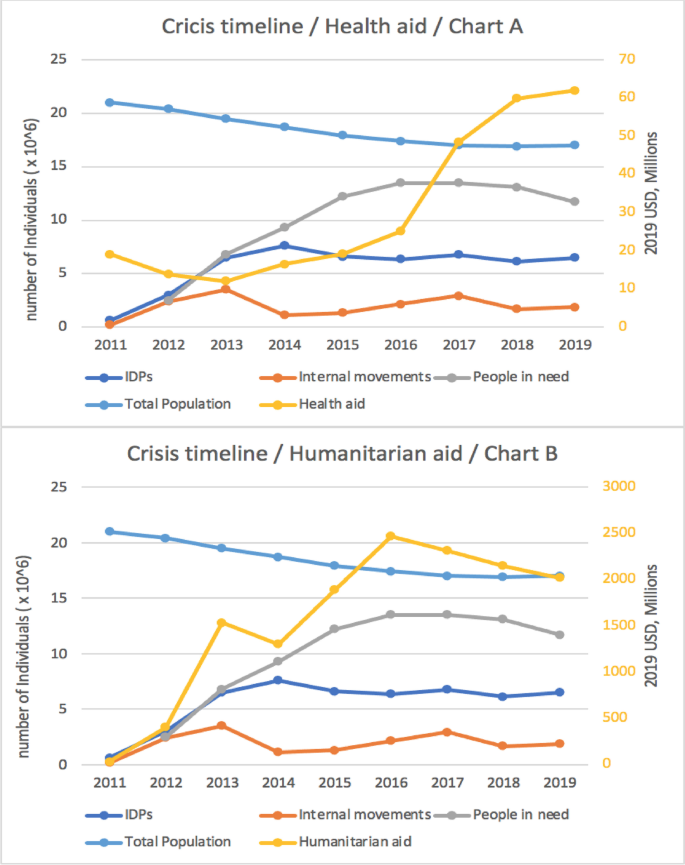

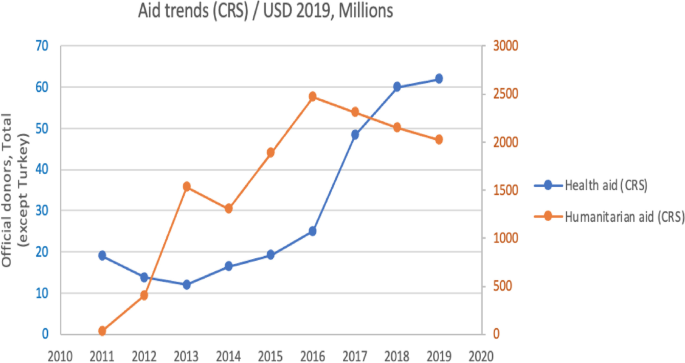

The Syrian civil war is the epitome of a health and humanitarian crisis, as highlighted by recent chemical attacks in a Damascus suburb, impacting millions of people across Syria and leading to a mass migration of refugees seeking to escape this protracted and devastating conflict. After 7 long years of war, more than 6 million people are internally displaced within Syria — the largest displacement crisis in the world — and more than 5 million registered Syrian refugees have been relocated to neighboring countries [ 1 , 2 ]. In total, this equates to an estimated six in ten Syrians who are now displaced from their homes [ 3 ].

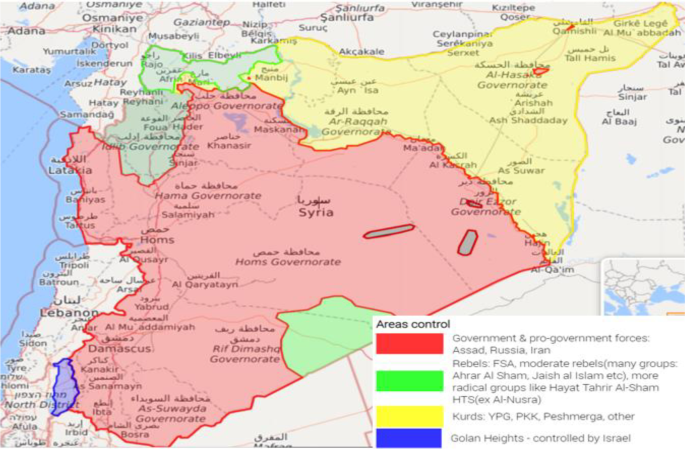

Syrian internally displaced persons (IDPs) are individuals who continue to reside in a fractured Syrian state now comprising a patchwork of government- and opposition-held areas suffering from a breakdown in governance [ 4 ]. As the Syrian conflict continues, the number of IDPs and Syrian refugees continues to grow according to data from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). This growth is continuing despite some borders surrounding Syria being closed and in part due to a rising birth rate in refugee camps [ 5 , 6 ]. This creates acute challenges for neighboring/receiving countries in terms of ensuring adequate capacity to offer essential services such as food, water, housing, security, and specifically healthcare [ 4 , 7 , 8 ].

Though Syrian refugees and IDPs face similar difficulties in relation to healthcare access in a time of conflict and displacement, their specific challenges and health needs are distinctly different, as IDPs lack the same rights guaranteed under international law as refugees, and refugees have variations in access depending on their circumstances. Specifically, there are gaps in access to medical care and medicines for both the internally displaced and refugees, whether it be in Syria, in transit countries (including services for refugees living in camps versus those living near urban cities), or in eventual resettlement countries. In particular, treatment of chronic diseases and accessing of hospital care can be difficult, exacerbated by Syrian families depleting their savings, increased levels of debt, and a rise in those living in poverty (e.g., more than 50% of registered Syrian refugees in Jordan are burdened with debt) [ 9 ].

Despite ongoing actions of international humanitarian organizations and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to alleviate these conditions, healthcare access and coverage for displaced Syrians and refugees is getting worse as the conflict continues [ 4 , 10 ]. Although Syria operated a strong public health system and was experiencing improved population health outcomes pre-crisis, the ongoing conflict, violence, and political destabilization have led to its collapse [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. Specifically, campaigns of violence against healthcare infrastructure and workers have led to the dismantling of the Syrian public health system, particularly in opposition-held areas, where access to even basic preventive services has been severely compromised [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ].

Collectively, these dire conditions leave millions of already-vulnerable Syrians without access to essential healthcare services, a fundamental human right and one purportedly guaranteed to all Syrian citizens under its constitution [ 4 ]. Importantly, at the nexus of this health and humanitarian crisis are the most vulnerable: internally displaced Syrian women and children. Hence, this opinion piece first describes the unique challenges and needs faced by this vulnerable population and then describes the case study of the Brotherhood Medical Center (the “Center”), an organization established to provide free and accessible maternal and child health (MCH) services for Syrian IDPs, and how it represents lessons regarding the successes and ongoing challenges of a local medical humanitarian intervention.

Syria: a health crisis of the vulnerable

Critically, women and children represent the majority of all Syrian IDPs and refugees, which directly impacts their need for essential MCH services [ 18 ]. Refugee and internally displaced women and children face similar health challenges in conflict situations, as they are often more vulnerable than other patient populations, with pregnant women and children at particularly high risk for poor health outcomes that can have significant short-term, long-term, and inter-generational health consequences [ 10 ]. Shared challenges include a lack of access to healthcare and MCH services, inadequate vaccination coverage, risk of malnutrition and starvation, increased burden of mental health issues due to exposure to trauma, and other forms of exploitation and violence such as early marriage, abuse, discrimination, and gender-based violence [ 4 , 10 , 19 , 20 ]. Further, scarce medical resources are often focused on patients suffering from acute and severe injury and trauma, leading to de-prioritization of other critical services like MCH [ 4 ].

Risks for women

A 2016 United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) report estimated that 360,000 Syrian IDPs are pregnant, yet many do not receive any antenatal or postnatal care [ 21 , 22 ]. According to estimates by the UNFPA in 2015, without adequate international funding, 70,000 pregnant Syrian women faced the risk of giving birth in unsafe conditions if access to maternal health services was not improved [ 23 ]. For example, many women cannot access a safe place with an expert attendant for delivery and also may lack access to emergency obstetric care, family planning services, and birth control [ 4 , 19 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ]. By contrast, during pre-conflict periods, Syrian women enjoyed access to standard antenatal care, and 96% of deliveries (whether at home or in hospitals) were assisted by a skilled birth attendant [ 13 ]. This coverage equated to improving population health outcomes, including data from the Syrian Ministry of Health reporting significant gains in life expectancy at birth (from 56 to 73.1 years), reductions in infant mortality (decrease from 132 per 1000 to 17.9 per 1000 live births), reductions in under-five mortality (from 164 to 21.4 per 1000 live births), and declines in maternal mortality (from 482 to 52 per 100,000 live births) between 1970 and 2009, respectively [ 13 ].

Post-conflict, Syrian women now have higher rates of poor pregnancy outcomes, including increased fetal mortality, low birth weights, premature labor, antenatal complications, and an increase in puerperal infections, as compared to pre-conflict periods [ 10 , 13 , 25 , 26 ]. In general, standards for antenatal care are not being met [ 29 ]. Syrian IDPs therefore experience further childbirth complications such as hemorrhage and delivery/abortion complications and low utilization of family planning services [ 25 , 28 ]. Another example of potential maternal risk is an alarming increase in births by caesarean section near armed conflict zones, as women elect for scheduled caesareans to avoid rushing to the hospital during unpredictable and often dangerous circumstances [ 10 ]. There is similar evidence from Syrian refugees in Lebanon, where rates of caesarean sections were 35% (of 6366 deliveries assessed) compared to approximately 15% as previously recorded in Syria and Lebanon [ 30 ].

Risks for children

Similar to the risks experienced by Syrian women, children are as vulnerable or potentially at higher risk during conflict and health and humanitarian crises. According to the UNHCR, there are 2.8 million children displaced in Syria out of a total of 6.5 million persons, and just under half (48%) of Syrian registered refugees are under 18 years old [ 1 ]. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) further estimates that 6 million children still living in Syria are in need of humanitarian assistance and 420,000 children in besieged areas lack access to vital humanitarian aid [ 31 ].

For most Syrian internally displaced and refugee children, the consequences of facing lack of access to essential healthcare combined with the risk of malnutrition (including cases of severe malnutrition and death among children in besieged areas) represent a life-threatening challenge (though some studies have positively found low levels of global acute malnutrition in Syrian children refugee populations) [ 24 , 32 , 33 , 34 ]. Additionally, UNICEF reports that pre-crisis 90% of Syrian children received routine vaccination, with this coverage now experiencing a dramatic decline to approximately 60% (though estimating vaccine coverage in Syrian IDP and refugee populations can be extremely difficult) [ 35 ]. A consequence of lack of adequate vaccine coverage is the rise of deadly preventable infectious diseases such as meningitis, measles, and even polio, which was eradicated in Syria in 1995, but has recently re-emerged [ 36 , 37 , 38 ]. Syrian refugee children are also showing symptoms of psychological trauma as a result of witnessing the war [ 4 , 39 ].

A local response: the Brotherhood Medical Center

In direct response to the acute needs faced by Syrian internally displaced women and children, we describe the establishment, services provided, and challenges faced by the Brotherhood Medical Center (recently renamed the Brotherhood Women and Children Specialist Center and hereinafter referred to as the “Center”), which opened its doors to patients in September 2014. The Center was the brainchild of a group of Syrian and Saudi physicians and donors who had the aim of building a medical facility to address the acute need for medical humanitarian assistance in the village of Atimah (Idlib Governorate, Syria), which is also home to a Syrian displacement camp.

Atimah (Idlib Governorate, Syria) is located on the Syrian side of the Syrian-Turkish border. Its population consisted of 250,000 people pre-conflict in an area of approximately 65 km 2 . Atimah and its adjacent areas are currently generally safe from the conflict, with both Atimah and the entire Idlib Governorate outside the control of the Syrian government and instead governed by the local government. However, continued displacement of Syrians seeking to flee the conflict has led to a continuous flow of Syrian families into the area, with the population of the town growing to approximately a million people.

In addition to the Center, there are multiple healthcare centers and field hospitals serving Atimah and surrounding areas that cover most medical specialties. These facilities are largely run by local and international health agencies including Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF), Medical Relief for Syria, and Hand in Hand for Syria, among others. Despite the presence of these organizations, the health needs of IDPs exceeds the current availability of healthcare services, especially for MCH services, as the majority of the IDPs belong to this patient group. This acute need formed the basis for the project plan establishing the Center to serve the unique needs of Syrian internally displaced women and children.

Operation of the Center

The Center’s construction and furnishing took approximately 1 year after land was purchased for its facility, a fact underlining the urgency of building a permanent local physical infrastructure to meet healthcare needs during the midst of a conflict. Funds to support its construction originated from individual donors, Saudi business men, and a group of physicians. In this sense, the Center represents an externally funded humanitarian delivery model focused on serving a local population, with no official government, NGO, or international organization support for its initial establishment.

The facility’s primary focus is to serve Syrian women and children, but since its inception in 2014, the facility has grown to cater for an increasing number of IDPs and their diverse needs. When it opened, facility services were limited to offering only essential outpatient, gynecology, and obstetrics services, as well as operating a pediatric clinic. The staffing at the launch consisted of only three doctors, a midwife, a nurse, an administrative aid, and a housekeeper, but there now exist more than eight times this initial staff count. The staff operating the Center are all Syrians; some of them are from Atimah, but many also come from other places in Syria. The Center’s staff are qualified to a large extent, but still need further training and continuing medical education to most effectively provide services.

Though staffing and service provision has increased, the Center’s primary focus is on its unique contribution to internally displaced women and children. Expanded services includes a dental clinic 1 day per week, which is run by a dentist with the Health Affairs in Idlib Governorate, and has been delegated to cover the dental needs for the hospital patients . Importantly, the Center facility has no specific policy on patient eligibility, its desired patient catchment population/area, or patient admission, instead opting to accept all women and children patients, whether seeking routine or urgent medical care, and providing its services free of charge.

Instead of relying on patient-generated fees (which may be economically prohibitive given the high levels of debt experienced by IDPs) or government funding, the Center relies on its existing donor base for financing the salaries for its physicians and other staff as well as the facility operating costs. More than an estimated 300 patients per day have sought medical attention since its first day of operation, with the number of patients steadily increasing as the clinic has scaled up its services.

Initially the Center started with outpatient (OPD) cases only, and after its partnership with the Syrian Expatriate Medical Association (SEMA) (discussed below), inpatient care for both women and children began to be offered. Patients’ statistics for September 2017 reported 3993 OPD and emergency room visits and 315 inpatient admissions including 159 normal deliveries and 72 caesarean sections, 9 neonatal intensive care unit cases, and 75 admissions for other healthcare services. To better communicate the clinic’s efforts, the Center also operates a Facebook page highlighting its activities (in Arabic at https://www.facebook.com/مشفى-الإخاء-التخصصي-129966417490365/ ).

Challenges faced by the Center and its evolution

The first phase of the Center involved its launch and initial operation in 2014 supported by a small group of donors who self-funded the startup costs needed to operationalize the Center facility’s core clinical services. Less than 2 years later, the Center faced a growing demand for its services, a direct product of both its success in serving its targeted community and the protracted nature of the Syrian conflict. In other words, the Center facility has continuously needed to grow in the scope of its service delivery as increasing numbers of families, women, and children rely on the Center as their primary healthcare facility and access point.

Meeting this increasing need has been difficult given pragmatic operational challenges emblematic of conflict-driven zones, including difficulties in securing qualified and trained medical professionals for clinical services, financing problems involving securing funding due to the shutdown of banking and money transferring services to and from Syria, and macro political factors (such as the poor bilateral relationship between Syria and its neighboring countries) that adversely affect the clinic’s ability to procure medical and humanitarian support and supplies [ 40 ]. Specifically, the Center as a local healthcare facility originally had sufficient manpower and funding provided by its initial funders for its core operations and construction in its first year of operation. However, maintaining this support became difficult with the closure of the Syrian-Turkish border and obstacles in receiving remittances, necessitating the need for broader strategic partnership with a larger organization.

Collectively, these challenges required the management committee and leadership of the Center to shift its focus to securing long-term sustainability and scale-up of services by seeking out external forms of cooperation and support. Borne from this need was a strategic partnership with SEMA, designed to carry forward the next phase of the Center’s operation and development. SEMA, established in 2011, is a non-profit relief organization that works to provide and improve medical services in Syria without discrimination regarding gender, ethnic, or political affiliation — a mission that aligns with the institutional goals of the Center. Selection of SEMA as a partner was based on its activity in the region; SEMA plays an active role in healthcare provision in Idlib and surrounding areas. Some other organizations were also approached at the same time of this organization change, with SEMA being the most responsive.

Since the Center-SEMA partnership was consummated, the Center has received critical support in increasing its personnel capacity and access to medicines, supplies, and equipment, resulting in a gradual scale-up and improvement in its clinical services. This now includes expanded pediatric services and the dental clinic (as previously mentioned and important, as oral health is a concern for many Syrian parents and children). The Center also now offers caesarean deliveries [ 41 ]. However, the Center, similar to other medical humanitarian operations in the region, continues to face many financial and operational challenges, including shortage of medical supplies, lack of qualified medical personnel, and needs for staff development.

Challenges experienced by the Center and other humanitarian operations continue to be exacerbated by the ongoing threat of violence and instability emanating from the conflict that is often targeted at local organizations and international NGOs providing health aid. For example, MSF has previously been forced to suspend its operations in other parts of Syria, has evacuated its facilities after staff have been abducted and its facilities bombed, and it has also been subject to threats from terrorist groups like the Islamic State (IS) [ 42 ].

The case study of the Center, which evolved from a rudimentary medical tent originally located directly in the Atimah displacement camp to the establishment of a local medical facility now serving thousands of Syrian IDPs, is just one example of several approaches aimed at alleviating the suffering of Syrian women and children who have been disproportionately victimized by this devastating health and humanitarian crisis. Importantly, the Center represents the maturation of a privately funded local operation designed to meet an acute community need for MCH services, but one that has necessitated continuous change and evolution as the Syrian conflict continues and conditions worsen. Despite certain successes, a number of challenges remain that limit the potential of the Center and other health humanitarian operations to fully serve the needs of Syrian IDPs, all of which should serve as cautionary principles for future local medical interventions in conflict situations.

A primary challenge is the myriad of logistical difficulties faced by local medical humanitarian organizations operating in conflict zones. Specifically, the Center continues to experience barriers in securing a reliable and consistent supply of medical equipment and materials needed to ensure continued operation of its clinical services, such as its blood bank, laboratory services, operating rooms, and intensive care units. Another challenge is securing the necessary funding to make improvements to physical infrastructure and hire additional staff to increase clinical capacity. Hence, though local initiatives like the Center may have initial success getting off the ground, scale-up and ensuring sustainability of services to meet the increasing needs of patients who remain in a perilous conflict-driven environment with few alternative means of access remain extremely challenging.

Despite these challenges, it is clear that different types of medical humanitarian interventions deployed in the midst of health crises have their own unique roles and contributions. This includes a broad scope of activities now focused on improving health outcomes for Syrian women and children that are being delivered by international aid agencies located outside of the country, international or local NGOs, multilateral health and development agencies, and forms of bilateral humanitarian assistance. The Center contributes to this health and humanitarian ecosystem by providing an intervention focused on the needs of Syrian women and children IDPs where they need it most, close to home.

However, the success of the Center and other initiatives working to end the suffering of Syrians ultimately relies on macro organizational and political issues outside Atimah’s border. This includes better coordination and cooperation of aid and humanitarian stakeholders and increased pressure from the international community to finally put an end to a civil war that has no winners — only victims — many of whom are unfortunately women and children.

Abbreviations

the Brotherhood Women and Children Specialist Center

Internally displaced persons

Maternal and child health

Medecins Sans Frontieres

Non-governmental organizations

Outpatient department

Syrian Expatriate Medical Association

United Nations Population Fund

the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

The United Nations Children’s Fund

UNHCR. Syria Regional Refugee Response: Inter-agency Information Sharing Portal [Internet]. data.unhcr.org. 2017. http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/regional.php . Accessed 17 July 2017.

iDMC. Syria [Internet]. 2017. http://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/syria . Accessed 31 Aug 2017.

Connor P, Krogstad JM. About six-in-ten Syrians are now displaced from their homes [Internet]. pewresearch.org. 2016. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/06/13/about-six-in-ten-syrians-are-now-displaced-from-their-homes/ . Accessed 31 Aug 2017.

Akbarzada S, Mackey TK. The Syrian public health and humanitarian crisis: a “displacement” in global governance? Glob Public Health. 2017;44:1–17.

Article Google Scholar

Albaster O. Birth rate soars in refugee camp as husbands discourage use of contraception [Internet]. 2016. independent.co.uk . http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/birth-rate-soars-in-jordan-refugee-camp-as-husbands-discourage-wives-from-using-contraception-a6928241.html . Accessed 21 Nov 2017.

Reliefweb. Closing Borders, Shifting Routes: Summary of Regional Migration Trends Middle East – May, 2016 [Internet]. reliefweb.int. 2016. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/closing-borders-shifting-routes-summary-regional-migration-trends-middle-east-may-2016 . Accessed 21 Nov 2017.

Schweiger G. The duty to bring children living in conflict zones to a safe haven. J Glob Ethics. 2016;12:380–97.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Arcos González P, Cherri Z, Castro Delgado R. The Lebanese–Syrian crisis: impact of influx of Syrian refugees to an already weak state. RMHP. 2016;9:165–72.

UNHCR and partners warn in Syria report of growing poverty, refugee needs. Geneva: UNHCR; 2016.

Devakumar D, Birch M, Rubenstein LS, Osrin D, Sondorp E, Wells JCK. Child health in Syria: recognising the lasting effects of warfare on health. Confl Heal. 2015;9:34.

Ferris E, Kirişçi K, Shaikh S. Syrian crisis: massive displacement, dire needs and a shortage of solutions. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution; 2013.

Google Scholar

Abu-Sada C, Serafini M. Humanitarian and medical challenges of assisting new refugees in Lebanon and Iraq. Forced Migr Rev. 2013:1:70–3.

Kherallah M, Sahloul Z, Jamil G, Alahfez T, Eddin K. Health care in Syria before and during the crisis. Avicenna J Med. 2012;2:51–3. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4103/2231-0770.102275

Heisler M, Baker E, McKay D. Attacks on health care in Syria — normalizing violations of medical neutrality? N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2489–91.

Cook J. Syrian medical facilities were attacked more than 250 times this year [Internet]. huffingtonpost.com . 2016. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/syria-hospital-attacks_us_56c330f0e4b0c3c550528d2e . Accessed 31 Aug 2017.

Ozaras R, Leblebicioglu H, Sunbul M, Tabak F, Balkan II, Yemisen M, et al. The Syrian conflict and infectious diseases. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. 2016;14:547–55.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Fouad FM, Sparrow A, Tarakji A, Alameddine M, El-Jardali F, Coutts AP, et al. Health workers and the weaponisation of health care in Syria: a preliminary inquiry for The Lancet-American University of Beirut Commission on Syria. Lancet. 2017:390:2516–26;

Women in the World. Women and children now make up the majority of refugees [Internet]. nytimes.com. 2016. http://nytlive.nytimes.com/womenintheworld/2016/05/16/women-and-children-now-make-up-the-majority-of-refugees/ . Accessed 31 Aug 2017.

Yasmine R, Moughalian C. Systemic violence against Syrian refugee women and the myth of effective intrapersonal interventions. Reprod Health Matters. 2016;24:27–35.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Elsafti AM, van Berlaer G, Safadi Al M, Debacker M, Buyl R, Redwan A, et al. Children in the Syrian civil war: the familial, educational, and public health impact of ongoing violence. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2016;10:874–82.

Save the Children. A devastating toll: the impact of three years of war on the health of Syria's children [Internet]. 2014. http://www.savethechildren.org/atf/cf/%7B9def2ebe-10ae-432c-9bd0-df91d2eba74a%7D/SAVE_THE_CHILDREN_A_DEVASTATING_TOLL.PDF . Accessed 12 Jan 2016.

UNFPA. Women and girls in the Syria crisis: UNFA response [Internet]. unfpa.org. 2015. https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/UNFPA-FACTSANDFIGURES-5%5B4%5D.pdf . Accessed 31 Aug 2017.

UNFPA. Shortage in funding threatens care for pregnant Syrian refugees [Internet]. unfpa.org. 2015. http://www.unfpa.org/news/shortage-funding-threatens-care-pregnant-syrian-refugees . Accessed 31 Aug 2017.

Bilukha OO, Jayasekaran D, Burton A, Faender G, King’ori J, Amiri M, et al. Nutritional status of women and child refugees from Syria-Jordan, April-May 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:638–9.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Reese Masterson A, Usta J, Gupta J, Ettinger AS. Assessment of reproductive health and violence against women among displaced Syrians in Lebanon. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14:25.

Samari G. Syrian refugee women’s health in Lebanon, Turkey, and Jordan and recommendations for improved practice. World Med Health Policy. 2017;9:255–74.

Hakeem O, Jabri S. Adverse birth outcomes in women exposed to Syrian chemical attack. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e196. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(15)70077-x

West L, Isotta-Day H, Ba-Break M, Morgan R. Factors in use of family planning services by Syrian women in a refugee camp in Jordan. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2016. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2014-101026.

Benage M, Greenough P, Vinck P, Omeira N, Pham P. An assessment of antenatal care among Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Confl Heal. 2015;9:8.

Huster KMJ, Patterson N, Schilperoord M, Spiegel P. Cesarean sections among Syrian refugees in Lebanon from December 2012/January 2013 to June 2013: probable causes and recommendations. Yale J Biol Med. 2014;87:269–88.

UNICEF. Humanitarian Action for Children - Syrian Arab Republic [Internet]. unicef.org. 2017. https://www.unicef.org/appeals/syria.html . Accessed 31 Aug 2017.

Hossain SMM, Leidman E, King’ori J, Harun Al A, Bilukha OO. Nutritional situation among Syrian refugees hosted in Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon: cross sectional surveys. Confl Heal. 2016;10:26.

Mebrahtu S. The struggle to reach Syrian children with quality nutrition [Internet]. 2015. https://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/syria_83147.html . Accessed 31 Aug 2017.

Nolan D. Children of Syria by the numbers [Internet]. 2016. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/children-of-syria-by-the-numbers/ . Accessed 31 Aug 2017.

Roberton T, Weiss W, The Jordan Health Access Study Team, The Lebanon Health Access Study Team, Doocy S. Challenges in estimating vaccine coverage in refugee and displaced populations: results from household surveys in Jordan and Lebanon. Vaccine. 2017;5:22.

Al-Moujahed A, Alahdab F, Abolaban H, Beletsky L. Polio in Syria: problem still not solved. Avicenna J Med. 2017;7:64–6.

Mbaeyi C, Ryan MJ, Smith P, Mahamud A, Farag N, Haithami S, et al. Response to a large polio outbreak in a setting of conflict — Middle East, 2013-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:227–31.

Sharara SL, Kanj SS. War and infectious diseases: challenges of the Syrian civil war. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004438.

Hassan G, Ventevogel P, Jefee-Bahloul H, Barkil-Oteo A, Kirmayer LJ. Mental health and psychosocial wellbeing of Syrians affected by armed conflict. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2016;25:129–41.

Sen K, Al-Faisal W, AlSaleh Y. Syria: effects of conflict and sanctions on public health. J Public Health (Oxf). 2013;35:195–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fds090 .

Pani SC, Al-Sibai SA, Rao AS, Kazimoglu SN, Mosadomi HA. Parental perception of oral health-related quality of life of Syrian refugee children. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2017;7:191–6.

Liu J. Syria: Unacceptable humanitarian failure [Internet]. 2015. http://www.msf.org/en/article/syria-unacceptable-humanitarian-failure . Accessed 31 Aug 2017.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Joint Masters Program in Health Policy and Law, University of California - California Western School of Law, San Diego, CA, USA

Rahma Aburas

Brotherhood Medical Center for Women and Children, Atimah, Syria

Amina Najeeb

Department of Anesthesiology, University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, San Diego, CA, USA

Laila Baageel & Tim K. Mackey

Department of Medicine, Division of Global Public Health, University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, San Diego, CA, USA

Tim K. Mackey

Global Health Policy Institute, San Diego, CA, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

We note that with respect to author contributions, all authors jointly collected the data, designed the study, conducted the data analyses, and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the formulation, drafting, completion, and approval of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Tim K. Mackey .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This community case study did not involve the direct participation of human subjects and did not include any personally identifiable health information. Hence, the study did not require ethics approval.

Competing interests

Amina Najeeb and Laila Baageel, two co-authors of this paper, were part of the foundation of the Center, remain active in its operation, and have a personal interest in the success of the operation of the clinic. The remaining authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Aburas, R., Najeeb, A., Baageel, L. et al. The Syrian conflict: a case study of the challenges and acute need for medical humanitarian operations for women and children internally displaced persons. BMC Med 16 , 65 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1041-7

Download citation

Received : 05 September 2017

Accepted : 20 March 2018

Published : 11 May 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1041-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Maternal child health

- Syrian crisis

- Humanitarian health aid

- Internally displaced people

BMC Medicine

ISSN: 1741-7015

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Cookies on this website

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you click 'Accept all cookies' we'll assume that you are happy to receive all cookies and you won't see this message again. If you click 'Reject all non-essential cookies' only necessary cookies providing core functionality such as security, network management, and accessibility will be enabled. Click 'Find out more' for information on how to change your cookie settings.

- Accessibility

- Connect with us

- Past projects

The Politics of the Syrian Refugee Crisis

Active 2016 - 2017

Funded by the SWISS FEDERAL DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS

Examining the politics of responses by the main host states of first asylum in the Syrian refugee crisis

Over 4 million refugees have fled Syria since the outbreak of the crisis and the armed conflicts in 2011. The overwhelming majority of these people have been hosted by Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey in what has been described by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees as “the biggest humanitarian emergency of our era ” . The crisis has created a set of fundamental policy challenges, including how to ensure ongoing protection in host countries with overwhelmed response capacities.

There has been a growing body of research on refugees from Syria. What has been lacking, however, is a focus on understanding the politics of responses by the main host states of first asylum: Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey. Although we already know a lot about those governments’ basic positions at the capital city level, there is a lot more to understand at the local level. For example, how do municipal or district level authorities shape responses, and what potential opportunities does this open up?

If we can better understand the layers of decision-making, and the gatekeepers that shape policy at local, national, and regional levels, then this in turn will point to new policy levers available to donor governments and the international community. Understanding how interests and power relations have played out at a micro-political level can open up new diplomatic channels to enhance protection space.

To take an example, in Jordan, in the governorate of Mafraq a series of opportunities to integrate Syrian refugees into local labour markets have emerged as a result of local political dynamics. Conversely, in Turkey, pressure on municipal authorities in Bodrum has created pressure on central government protection responses. Understanding these politics within the main host countries of first asylum is the key to unlocking protection space.

In this one-year project, we conducted fieldwork across the three main host countries. Methodologically, the research focused on undertaking qualitative interviews in each of the capital cities and a selection of local sites outside the capital city. The over-arching objective of the project is to inform policies that can enhance protection space for displaced Syrians within the region of origin.

A key output is the report Local Politics and the Syrian Refugee Crisis: Exploring Responses in Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan

Alexander Betts

Leopold Muller Professor of Forced Migration and International Affairs

Selected publications

Alexander Betts, Ali Ali, Fulya Memişoğlu, (2017)

March 13, 2024

Syria Refugee Crisis Explained

Here's What You Need to Know:

1. when did the syrian refugee crisis begin, 2. how are the türkiye-syria earthquakes impacting syrians, 3. where do syrian refugees live do all syrian refugees live in refugee camps, 4. what are syrian’s greatest challenges, 5. how are syrian children impacted by this crisis, 6. what is the un refugee agency doing to help syrians, when did the syrian refugee crisis begin.

The Syrian refugee crisis began in March 2011 as a result of a violent government crackdown on public demonstrations in support of teenagers who were arrested for anti-government graffiti in the southern town of Daraa. The arrests sparked public demonstrations throughout Syria which were violently suppressed by government security forces. The conflict quickly escalated and the country descended into a civil war that forced millions of Syrian families to flee their homes. Thirteen years later, the conflict is ongoing with Syrians continuing to pay the price—more than 16.7 million people in Syria are in need of humanitarian assistance, accounting for 70 percent of the population.

How are the Türkiye-Syria Earthquakes impacting Syrians?

On February 6, 2023, two powerful earthquakes struck south-eastern Türkiye and northern Syria, claiming thousands of lives and causing untold destruction to homes and infrastructure across the region. This is a crisis on top of existing crises already impacting internally displaced Syrians and Syrian refugees.

In Türkiye, the heavily impacted areas are regions where Syrian refugees live in high numbers. Syrian refugees were already vulnerable, living with protection risks and economic insecurity. For people inside Syria, the earthquake has only brought on more misery and pain and catapulted some of the most in need communities in the country into utter desperation.

As of March 2024, the earthquake has impacted 8.8 million people across Syria, uprooting tens of thousands—many of whom had already been displaced. The earthquake claimed 60,000 lives, with tens of thousands injured and entire neighborhoods reduced to rubble. In north-west Syria alone, more than 40,000 people remain displaced by the earthquake and are living in temporary reception centers.

The immediate impact of the earthquake has been devastating, but the full extent of the damage is yet to be seen. The long-term impacts of the earthquakes pose serious challenges for Syrians and will require a robust response on multiple fronts.

Where do Syrian refugees live? Do all Syrian refugees live in refugee camps?

Syrian refugees have sought asylum in more than 130 countries, but the vast majority live in neighboring countries within the region, such as Türkiye, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq and Egypt. Türkiye alone hosts the largest population of Syrian refugees: 3.3 million. Approximately 92 percent of refugees who have fled to neighboring countries live in rural and urban settings, with only roughly five percent living in refugee camps . However, living outside refugee camps does not necessarily mean success or stability. More than 70 percent of Syrian refugees are living in poverty, with limited access to basic services, education or job opportunities and few prospects of returning home.

What are Syrians' greatest challenges?

Protracted displacement, the war in Ukraine, global inflation and the earthquakes that struck south-eastern Türkiye and northern Syria are some of the biggest challenges Syrians currently face.

Poverty and unemployment are widespread within Syria, with over 90 percent of the population in Syria living below the poverty line. By October 2023, the cost of the food basket had doubled compared to January and quadrupled in the last two years. An estimated 12.9 million people are food insecure as a result of the economic crisis.

The situation for Syrian refugees living in neighboring host countries has deteriorated as well. Economic challenges in neighboring countries like Lebanon have pushed Syrians in the country into poverty with more than 90 percent of Syrian refugees reliant on humanitarian assistance to survive. In Jordan, more than 93 percent of Syrian households reported being in debt to cover basic needs. Ninety percent of Syrian refugees living in Türkiye cannot fully cover their monthly expenses or basic needs.

Millions of refugees have lost their livelihoods and are increasingly unable to meet their basic needs - including accessing clean water, electricity, food, medicine and paying rent. The economic downturn has also exposed them to multiple protection risks, such as child labor, gender-based violence, early marriage and other forms of exploitation.

How are Syrian children impacted by this crisis?

Thirteen years of crisis have had a profound impact on Syrian children. They have been exposed to violence and indiscriminate attacks, losing their loved ones, their homes, their possessions and everything they once knew. They have grown up knowing nothing but the crisis. Today, over 47 percent of Syrian refugees in the region are under 18 years old and more than a third of them do not have access to education. In Syria, more than 2.4 million children are out of school and 1.6 million children are at risk of dropping out.

Children’s rights during the crisis are undermined on a daily basis. An increasing number of Syrian children have fallen victim to child labor, with cases in Lebanon almost doubling in just one year.

Read some of their stories

What is the UN Refugee Agency doing to help Syrians?

The UN Refugee Agency has been on the ground since the start of the crisis providing shelter, lifesaving supplies, clean water, hot meals and medical care to families who have been forced to flee their homes. UNHCR has also helped repair civilian infrastructure – including homes, school facilities and recreation centers, supported educational activities for children and provided psycho-social support.

UNHCR and humanitarian partners are responding to the Türkiye-Syria Earthquakes by stepping up their assistance in the two countries. In Syria, UNHCR has delivered protection assistance, including psychosocial support, to more than 311,000 people affected by the earthquakes. UNHCR is also providing shelter support, cash assistance and other aid to those affected. In Türkiye, UNHCR has provided over 3 million relief items including tents, containers, hygiene kits, bedding and warm clothing for refugees and local residents in temporary accommodation centers. UNCHR is also supporting protection activities for more than 500,000 people – including legal counseling, identification and referral of people with specific needs, psychosocial support and cash assistance.

Help protect Syrian refugees...

Monthly giving is the most convenient, effective and efficient way you can help people fleeing conflict. Start making a lifesaving difference today. Please become USA for UNHCR’s newest monthly donor.

More Related News

Syrian refugees face waning support and hope after 13 years

Zuhur is among more than 5 million Syrians still living as refugees 13 years into the Syrian crisis, but Lebanon’s economic turmoil and decreased humanitarian support have pushed her and others to the brink.

A year after Türkiye-Syria quakes, UNHCR warns of rising humanitarian needs

A year after the devastating earthquakes that struck Türkiye and Syria in February 2023, the plight of millions of displaced people and their hosts has deteriorated, UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, warned today.

Culinary training offers refugees in the Washington, D.C. area a recipe for hope

Through culinary skills, community support and a shared commitment to hard work, refugees in the Washington, D.C. area are transforming challenges into opportunities and rebuilding their lives in the United States.

- Search Menu

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Journal of Global Security Studies

- About the International Studies Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, investigating the politics of host states’ forced migration management, theorizing refugee rentier states, methodology and case selection, foreign policy and the refugee rentier state in jordan, lebanon, and turkey, the syrian refugee crisis in regional perspective, acknowledgements.

- < Previous

The Syrian Refugee Crisis and Foreign Policy Decision-Making in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Gerasimos Tsourapas, The Syrian Refugee Crisis and Foreign Policy Decision-Making in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey, Journal of Global Security Studies , Volume 4, Issue 4, October 2019, Pages 464–481, https://doi.org/10.1093/jogss/ogz016

- Permissions Icon Permissions

How does forced migration affect the politics of host states and, in particular, how does it impact states’ foreign policy decision-making? The relevant literature on refugee politics has yet to fully explore how forced migration affects host states’ behavior. One possibility is that they will employ their position in order to extract revenue from other state or nonstate actors for maintaining refugee groups within their borders. This article explores the workings of these refugee rentier states , namely states seeking to leverage their position as host states of displaced communities for material gain. It focuses on the Syrian refugee crisis, examining the foreign policy responses of three major host states—Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey. While all three engaged in post-2011 refugee rent-seeking behavior , Jordan and Lebanon deployed a back-scratching strategy based on bargains, while Turkey deployed a blackmailing strategy based on threats. Drawing upon primary sources in English and Arabic, the article inductively examines the choice of strategy and argues that it depended on the size of the host state's refugee community and domestic elites’ perception of their geostrategic importance vis-à-vis the target. The article concludes with a discussion of these findings’ significance for understanding the international dimension of the Syrian refugee crisis and argues that they also pave the way for future research on the effects of forced displacement on host states’ political development.

“We can open the doors to Greece and Bulgaria anytime and we can put the refugees on buses,” Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan declared to a group of European Union (EU) senior officials in February 2016. “So how will you deal with refugees if you don't get a deal? Kill the refugees?” ( Reuters 2016a ). A year before this, the Greek Minister of Defense Panos Kammenos threatened that “we cannot keep ISIS out if the EU keeps bullying us” ( Aldrick and Carassava 2015 ). Other host states in the region—namely Lebanon and Jordan—have also repeatedly voiced their need for international economic assistance albeit by promising to continue supporting refugee populations within their borders. Indeed, forced migration often generates tensions in global politics and varied reactions by host states, most strikingly in the responses to the post-2011 displacement of Syrians across the Middle East and beyond. Existing theorization of host states’ engagement with forced migration flows indicates that they may aim to benefit from such outflows in an aggressive manner, even if they played no part in generating them. But this does not account for the full gamut of host states’ foreign policy choices or some states’ abstention from the use of coercion. This article aims to expand our understanding of the interplay between forced migration and power politics within the context of the Syrian refugee crisis, in order to address how refugee flows affect host states’ foreign policy.

I argue that a host state's domestic elites often approach refugee communities as potential sources of revenue. I introduce the term refugee rentier states to describe states that employ their position as host states of forcibly displaced populations to extract revenue, or refugee rent , from other state or nonstate actors in order to maintain these populations within their borders. Building on international relations literature on issue-linkage strategies, I identify two strategies through which a host state may exercise refugee rent-seeking behavior in its foreign policy: via blackmailing —threatening to flood a target state(s) with refugee populations within its borders, unless compensated—or via back-scratching —promising to maintain refugee populations within its borders, if compensated. Recognizing that a state's policy choice is rarely a simple binary between coercion and cooperation, I operationalize the two strategies with regard to specific patterns that allows to distinguish specific behavior patterns in host states’ policies. Using a three-case-study approach to examine the foreign policy behavior of the main host states of displaced Syrian communities since 2011, my data suggests that a host state's choice between blackmailing or back-scratching depends on domestic elites’ perception vis-à-vis the target state(s). Drawing on data collected in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey, I argue that a strategy of blackmailing is adopted when domestic elites believe that their state is geopolitically important vis-a-vis the target state(s) and they host a significant number of refugees. Otherwise, they are more likely to employ a strategy of back-scratching.

The article proceeds as follows. I review the relevant literature and present my theoretical model. I then introduce three case studies that will allow for further theory development via covariation and within-case analysis. Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan are selected for they constitute the largest host states of displaced Syrians in the post-2011 Middle East. I demonstrate how Lebanon and Jordan adopted a strategy of back-scratching in their foreign policy because, even though they believed they hosted large communities of Syrian refugees, they did not consider themselves geopolitically important vis-à-vis the European Union (EU). In sharp contrast, Turkey adopted a blackmailing strategy that can be explained by state elites’ perception of Turkey's geopolitical importance and the large size of Syrian refugees residing within its borders. I continue by explicitly discounting alternative explanations that may account for the three states’ foreign policy-making. I conclude with a note of how additional research may shed light on how forced displacement affects refugee rentier states’ domestic political development, particularly with regard to encouraging opportunities for state corruption, autocracy, and other pathologies associated with rentierism.

How does forced migration affect the politics of host states, and, in particular, how do the latter employ the presence of refugees in their foreign policy decision-making? A long line of international relations scholars has attempted to address these questions, albeit not systematically. As Betts and Loescher argue, “only relatively isolated pockets of theoretically informed literature have emerged on the international politics of forced migration,” while the study of refugee politics has yet to form part of mainstream international relations ( Betts and Loescher 2011 , 12–13). This is not to undermine the work of international politics scholars who critically examined the emergence of the international refugee regime, and who pioneered empirical work on the politics of forced migration ( Gordenker 1987 ; Zolberg 1989 ), primarily within the context of interstate conflict. During the Cold War, superpower rivalry resulted in forced displacement across developing states of the Third World ( Zolberg, Suhrke, and Aguayo 1989 ). It also shaped the refugee policy of American policy-makers, with Washington considering refugees “a weapon in the cold war” ( Zolberg 1988 , 661; Loescher and Scanlan 1986 ; Munz and Weiner 1997 ; Adamson 2006 , 190). Beyond the United States’ aiding of “lone individuals crossing borders to seek political freedom in the West” ( Stedman and Tanner 2004 , 5), host states also used refugees instrumentally in military conflicts, while numerous states sought to “embarrass or discredit adversary nations” by allowing refugee flows or to use them against an “adversarial neighboring regime” ( Teitelbaum 1984 ). In the Middle East, the status of Palestinian refugees served as a strategic asset for Arab states’ ongoing struggle against Israel ( Hinnebusch 2003 , 157); in the Rwandan and Pakistani contexts, humanitarian aid to refugee camps fueled violence by providing legitimacy and support to militants ( Lischer 2003 ). In fact, research has demonstrated the wide impact of refugees in the diffusion and exacerbation of conflict ( Lischer 2015 ), with Kaldor including displacement as a form of post-1989 “new wars” in the Balkans, sub-Saharan Africa, and elsewhere ( Kaldor 2013 ).

At the same time, the socioeconomic and political risks perceived to be associated with hosting large numbers of refugees has led to lukewarm responses in tackling the problem of forced migration ( Zolberg 1989 , 415; Loescher 1996 , 8). This also highlights some of the main problems behind the development of a functional global refugee regime ( Betts 2011 ), as “states have a legal obligation to support refugees on their own territory, [but] they have no legal obligation to support refugees on the territory of other states” ( Betts and Loescher 2011 , 19). Tackling this dichotomy lies at the heart of host states’ political engagement with forced migration. For historical and structural reasons, states across the Global South feature the large majority of refugee populations, which creates a power asymmetry with seemingly unaffected Global North states. Yet, Global North states continue to provide economic support for the governments of refugee host states in the Global South in an act of “calculated kindness” ( Loescher and Scanlan 1986 ; cf. Arar 2017b ). From a security perspective, they do so aiming to prevent the diffusion of forced displacement into their own territory, be it North America ( Weiner 1992 , 101) or Europe ( Huysmans 2000 ; Greenhill 2016 ). In attempting to examine how the North-South asymmetry may be perceived from the point of view of refugee host states, forcibly displaced populations arguably become a source of revenue, particularly given Western states’ tendency to offer “charity” in order to outsource refugee problems to the Global South (cf. Loescher 1996 ). Empirical examples attest to this: for instance, the influx of Afghani refugees into Pakistan paved the way for a five-year $3.2 billion aid package by the Reagan administration in 1981 ( Loescher 1992 ). More recently, between 2001 and 2007, Nauru received $30 million from the Australian government in order to host refugees and asylum seekers within the Nauru Regional Processing Centre, in addition to Australia covering its operating costs, at $72 million for 2001–2002 alone ( Oxfam 2002 ). 1 This is not to suggest that host states consciously encourage inflows of forcibly displaced populations—rather, that an inflow of refugees may constitute a strategic resource for these states’ governments.

How does the strategic importance of these forcibly displaced populations affect refugee host states’ foreign policy decision-making? Two research agendas are relevant in this regard: firstly, a small group of researchers examines issue-linkage processes, suggesting that “win-win” strategies may convince Global North states to continue providing support for protecting refugees in the South (cf. Hollifield 2012 ). As Betts argues, “in the absence of altruistic commitment by Northern states to support refugees in the South, issue-linkage has been integral in achieving international cooperation on refugees” ( Betts and Loescher 2011 , 20; Betts 2017 ). Secondly, work on leverage suggests that host states are also able to proceed unilaterally, aiming at extracting resources from target states that fear being overwhelmed by migrants or refugees; Greenhill demonstrates that host states may employ deportation in order to create targeted migrant or refugee “crises” in target countries that, in fear of being “capacity-swamped,” are likely to comply with these states’ demands ( Greenhill 2003 , 2010 ). As a result, Afghanistan, Sudan, Libya, and Jordan have been able to pursue issue-linkage strategies that manipulate “migration interdependence” by linking the management of cross-border population mobility to extracting foreign policy and economic benefits from Western and non-Western actors ( Tsourapas 2017 , 2018 ).

Two questions remain unresolved in existing theorizations of refugee host states’ policy-making: firstly, what is the full gamut of foreign policies that these states may employ in seeking to exploit the presence of a refugee population group on their soil, beyond encouraging generations of outflows? Greenhill argues for three types of refugee host states, namely “generators,” “ agent provocateurs ,” and “opportunists”—which do not consider states that aim to profit from forced displacement without resorting to coercion. A second, related question is the following: why do some refugee host states have more aggressive foreign policy preferences, while others develop strategies of policy coordination rather than coercion? In other words, when do refugee host states adopt a more coercive stance—reminiscent of Fidel Castro's use of the 1980 Mariel boatlift to exert pressure on the Carter administration—and when will they employ a more cooperative one, as in the case of Pakistan or Nauru? In addressing these questions, this article contributes to the literature by presenting a more complete picture of refugee host states’ foreign policy decision-making, as well as the rationale behind it.

reward—income or wealth—is not related to work and risk bearing, rather to chance or situation. For a rentier [state], reward becomes a windfall gain, an isolated fact, situational or accidental as against the conventional outlook where reward is integrated in a process as the end result of a long, systematic, and organized production circuit. The contradiction between production and rentier ethics is, thus, glaring. ( Beblawi 1987 , 385–86)

While rentier state theorists do not discuss cross-border population mobility, I introduce this framework into international refugee politics. I argue that refugee host states may adopt characteristics of a rentier state with regard to their management of forced migration, given that their governments are able to derive similar forms of unearned external income from a specific resource—namely, the presence of refugee populations within a state's borders. For the purposes of this analysis, a refugee rentier state is a state that hosts forcibly displaced population group(s) and relies financially on external income linked to its treatment of these group(s). Refugee rent may come from international organizations or third states in a variety of forms, including direct economic aid or grants, debt relief, preferential trade treatment, and so on. As per the expectations of rentier state theory, refugee host state actors are not engaged in the generation of such rent, but on its distribution or utilization, which may or may not directly relate to the domestic management of forcibly displaced population group(s). Finally, a refugee rentier state's government remains the principal recipient of this rent.

Some empirical examples allow the clarification of the refugee-rentier-state concept: Libya's reliance upon European economic aid under Colonel Gaddafi in order to prevent the outflow of sub-Saharan African refugees into the Mediterranean suggests that it is a refugee rentier state. the Libyan state was not involved in the creation of these refugee flows out of sub-Saharan Africa, and the Libyan government was the primary recipient of substantial European economic aid. In contrast, the 1923 population exchange between Turkey and Greece generated more than two million forcibly displaced persons and significant international economic support; yet, given the involvement of both states’ governments in the refugee-generation process, neither Turkey nor Greece qualify as refugee rentier states. Since 1948, Israel has witnessed the inflow of millions of Jewish refugees, notably from the Arab world and the Soviet Union; yet, it does not constitute a refugee rentier state, for Israeli governments do not receive any external income with regard to their treatment of these refugees. In contrast, the significant economic aid afforded to the Pakistani government in response to the influx of six million Afghan refugees since 1979 renders it a refugee rentier state.

As discussed in the previous section, the argument that refugee host states may seek material gains from the presence of displaced communities within their borders is not novel. In fact, already in 1984, Weiner had asserted that international migration may constitute a kind of “national resource” (quoted in Teitelbaum 1984 , 447). In this line of thought, the rentier state framework allows us a better understanding of states’ foreign policy decision-making and the rationale behind it, if examined via the prism of refugee rent-seeking behavior. I introduce two key terms from the literature on interdependence: blackmailing and back-scratching. For Oye, a central aspect of contemporary diplomacy within a world of asymmetrical power distribution involves the use of cross-issue linkage, via two forms. Firstly, blackmailing involves “threats to do something one does not believe to be in one's interest, unless compensated, and promises to refrain from doing something one does not believe to be in one's own interest, if compensated.” A main example is the Organisation of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries’ (OAPEC) oil embargo against the United States in 1973, which was not in the interests of its member states. On the other hand, back-scratching involves “promises to refrain from doing something one believes to be in one's interest, if compensated, and threats to do something one believes to be in one's interest, unless compensated.” One example of this is the post-1973 tacit agreement between Washington and Saudi Arabia to maintain oil production in excess of Saudi financial needs ( Oye 1979 , 14; cf. Haas 1980 ). Keohane and Nye summarize the difference between blackmailing and back-scratching by arguing that the first involves “making a threat one does not wish to carry out,” while the second refers to “offering a quid pro quo bargain” ( Keohane and Nye 1987 , 735).

Importing this model into refugee studies, I argue that there are two ways through which a host state may exercise rent-seeking behavior in its foreign policy: via blackmailing—threatening to flood target states with refugee populations within its borders, unless compensated—or via back-scratching—promising to refrain from taking unilateral action against refugee populations within its borders, if compensated. Although back-scratching and blackmailing may be considered as two sides of the same coin and the choice made by refugee rentier states may often be less clear-cut, there is value in understanding how the two policies may differ. I operationalize them as follows: on the one hand, a blackmailing strategy often includes threats of unilateral actions to be taken by a refugee host state. Blackmailers often frame their actions around potential losses that a target state(s) may incur and show little interest in international laws or norms. On the other hand, a back-scratching strategy is usually framed around common benefits accrued by cooperation. Back-scratchers tend to value multilateral negotiations rather than bilateral ones, and they believe that references to international laws or norms strengthen their case.

In order to understand whether a refugee rentier state will adopt a blackmailing or back-scratching strategy, I proceed inductively via an exploratory three-case study research design of the three main states hosting Syrian refugees in the aftermath of the 2011 Syrian conflict, namely Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey. In choosing a foreign policy strategy, I expect states to make a rational calculation based on their relative position and strength vis-à-vis their target state(s). This is not a structural variable based on geography alone: the relative position of Egypt vis-à-vis Great Britain, for instance, diminished in the aftermath of World War II once ensuring a safe passage to India became less important to London. The relative position of Pakistan vis-à-vis the United States increased exponentially in the aftermath of the Iranian Revolution and the Soviet Union's invasion of Afghanistan. A second expectation of refugee host-state foreign policy decision-making also involves an evaluation of itself vis-à-vis its target state(s). State strength may be calculated in numerous ways, but I expect the strength of a refugee host state to lie in the size of refugee communities it hosts, given that target states tend to estimate the significance of accepting refugees based on their numbers, rather than any other indicator such as age, sex, or educational status. As Teitelbaum and Weiner argue, the post–Cold War realities suggest that the United States and other Western states see migration flows less as instruments that “could both weaken our adversaries and strengthen our friends” and more as an imposition of “unacceptably high costs” and security threats ( Teitelbaum and Weiner 1995 , 17; Weiner 1996 , 17). The following section offers a brief discussion of the article's methodology before proceeding to the analysis of the three case studies in more detail.

I employ exploratory case-study methodology for the purposes of theory development through induction, and I rely on covariation and within-case analysis ( Bennett and Checkel 2015 ). Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan have been selected for they constitute the largest host states of Syrian refugees. As of September 2018, more than 3.56 million Syrian refugees have registered in Turkey, which currently constitutes the largest host state of Syrian refugees. Syrians enjoyed visa-free entry into Turkey, as part of a 2009 bilateral mobility agreement, until Turkey closed border crossing points in 2015. Estimates for Lebanon and Jordan vary, but they are acknowledged to be the second and third largest host states of Syrian refugees, with 1 to 2.2 million and 660,000 to 1.26 million Syrians, respectively. Jordan initially allowed Syrians free entry, albeit with restrictions on employment. Controls were gradually put in place, coinciding with the opening of the Za'atari refugee camp in July 2012, until border closures became more prominent since mid-2013. Syrians in Lebanon enjoyed similar freedom of entry but were also eligible to work based on the 1991 and 1993 bilateral agreements between the two countries. From October 2014 onward, the Lebanese government adopted the “October Policy” that tightened restrictions on entry and residency for Syrian refugees.

The potential pitfalls of the case-study method have been extensively examined in the literature ( Geddes 1990 ; Collier and Mahoney 1996 ), particularly if cases are selected on the dependent variable. Yet, a sizeable body of political science research also identifies how “in the early stages of a research program, selection on the dependent variable can serve the heuristic purpose of identifying the potential causes and pathways leading to the dependent variable of interest” ( George and Bennett 2005 , 23). Covariation is employed to substantiate the study's theoretical claims ( Gerring 2016 ), while within-case analysis is well suited to the “systematic examination of diagnostic evidence selected and analyzed” ( Collier 2011 , 823). The combination of the two methods enables the use of qualitative tools to assess the causal claims and mechanisms outlined in the previous section (for comparison, Beach and Pedersen 2013 ).

A final note on data collection: field research in the Global South contexts presents unique challenges ( Kapiszewski, MacLean, and Read 2015 , 218), particularly in light of the fact that regional migration is traditionally considered a security issue for ruling elites in broader Middle East. At the same time, research is plagued by a lack of detailed, publicly available statistical data on intra-Arab flows, a manipulation of statistics for economic and political gain, as well as by the fact that migration management is handled at the highest levels of the executive ( Tsourapas 2019 , 24–30). As Brand (2013 , 8) wrote on seeking statistical data on the Jordanian political economy, “one works under the assumption that such documents will probably never be released or may never have existed in the first place.” To overcome these issues, I rely upon a meticulous collection of primary sources, including Arabic and non-Arabic media reports collected during fieldwork in Amman and Beirut (2017 and 2018). For the purposes of triangulation, I also employ elite interviews, reports, briefs, and communications by international organizations and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) with regard to Syrian refugees in all three states.

Jordan and the February 2016 Compact

To what extent does Jordan constitute a refugee rentier state, and how has that influenced its foreign policy decision-making? With regard to the Syrian refugee crisis, the emergence of the Jordanian refugee rentier state occurred gradually, from 2013 onward. This is primarily evident in policy-makers’ attempt to render Syrian refugees as visible as possible to the international community, while also aiming to inflate their numbers. Despite a welcoming policy between 2011 and 2013, Jordan created the Directorate of Security Affairs for the Syrian Refugee Camps in March 2013 and, two months later, closed its border crossings with Syria, even to those carrying valid passports (Syrians do not need a visa for entry into Jordan). Palestinian Syrians, in particular, had been denied entry since April 2012 and officially since January 2013 ( Human Rights Watch 2014 ). A number of security reasons have been identified for these border closures that highlight the potential risks for sociopolitical unrest that a large influx of Palestinian-Syrians into the country might entail. A state security rationale does not, however, adequately account for the fact that Jordanian border officers prompted Syrians to enter the country via informal crossings, instead; at numerous times in the first three years of the Syrian conflict, the country's formal borders were closed to Syrian passport-holders, who were encouraged to use informal border crossings along the eastern border, instead.

While state security concerns were important for domestic policy-makers, the shift in Jordan's policy on border crossings was primarily aimed at increasing the international visibility of the Syrian refugee issue. Those entering the country through informal crossing points are automatically recognized as prima facie refugees, according to the 1998 Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) signed between Jordan and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). As a result, with the contribution of aid workers, local authorities were able to classify all Syrians entering into Jordan as refugees, rather than visitors. Syrians entering through informal crossing points were directly sent to the Za'atari refugee camp, near Mafraq. Whereas, in November 2012, Za'atari hosted some forty-five thousand Syrians, by February 2013 it was home to more than seventy-six thousand Syrians, a number that reached 156,000 refugees by March 11, 2013. This strategy enabled the Jordanian state to highlight that it was facing a clearly enumerated influx of Syrian refugees and to strengthen its appeals for international aid. The Jordanian security official in charge of the Azraq refugee camp, which was constructed in May 2014, notes that “if we hadn't built the camps, then the world would not understand that we were going through a crisis” ( Betts, Ali, and Memişoğlu 2017 , 9). As Turner argues, “part of the reason why Jordan built camps for Syrians is that it used encampment strategically to enable it to raise the profile of, and receive funds for, Syrian refugees on its territory” ( Turner 2015 , 393). In fact, Jordan insists that the number of Syrians inside its territory well exceeds the number of those formally registered; whereas the UNHCR puts forth approximately 655,500 Syrians registered with the United Nations inside Jordan, the government argues that Jordan hosted 1.3 million Syrians in 2017.

A strong indication of Jordan's refugee rent-seeking behavior lies in its treatment of earlier forced displacement, particularly Iraqi refugees that had entered its territory after 2003. By 2007, UNHCR estimated that Jordan hosted approximately fifty thousand registered Iraqis, but officials would claim that the number was between 750,000 and one million. This would cost the Jordanian state $1 billion annually. An independent report by Fafo, a Norwegian research institute commissioned by Jordan to establish an accurate estimate, produced a figure of 161,000 Iraqis, but the Jordanian government continued to inflate this figure. “We used to exaggerate the numbers with the Iraqis, but we do not do that anymore,” one high-ranking Jordanian official admitted, carefully noting that “we are not exaggerating the Syrian numbers” ( Arar 2017a , 14). At the same time, Jordan did not place Iraqis into camps, which has been identified as working “strongly against Jordan's attempts to secure increased financial aid” ( Turner 2015 , 393). Camps can turn refugees into a visible and “spatially legible population” ( Peteet 2011 , 18) and facilitate the counting of refugees, which in turn can facilitate fundraising ( Black 1998 ); in Jordan's case, the Iraqis were less visible to the international community, something that Jordanians sought to address with their management of Syrian refugees.

A number of domestic responses to Syrian refugees have been developed under a refugee rent-seeking rationale, particularly the July 2014 “bail out” process. According to this policy, Syrian refugees are permitted to exit their assigned camps only when they are able to secure a sponsorship from a Jordanian citizen, who has to be more than thirty-five years of age, married, and employed in a stable position. The Jordanian sponsor should also be able to prove a family relationship with the applicant and not have a criminal record ( Amnesty International 2013 ). While reliable data on this is not available, the Jordanian state's adoption of a bail-out process has encouraged phenomena of corruption and greed in the dealings between Syrian refugees and the Jordanian social body; numerous instances have been recorded of well-off Syrians that have been able to “buy” their way out of Jordanian refugee camps, for hefty prices. At the same time, the UNHCR has recorded instances of Syrians paying middlemen around $500 in order to be bailed out by unknown Jordanian citizens ( United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees 2013 , 8). The fact that Jordan cancelled this scheme in 2016, arguably once camp-enclosed Syrians who have been able to afford a Jordanian sponsor concluded such transactions, speaks to the state's refugee rent-seeking behavior.

Turning the Syrian refugee crisis into a development opportunity that attracts new investments and opens up the EU market with simplified rules of origin, creating jobs for Jordanians and Syrian refugees while supporting the postconflict Syrian economy;