- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Nine Teaching Ideas for Using Music to Inspire Student Writing

By Natalie Proulx

- May 10, 2018

Some of the greatest written works of our time have been inspired by music. Walt Whitman conceived of and wrote “Leaves of Grass” while listening to opera . Alice Walker, Langston Hughes, Ntozake Shange and Ralph Ellison were all moved by spirituals, jazz and blues . And Lin-Manuel Miranda’s rap musical “Hamilton” was born of his love of hip-hop . These writers understood what many educational researchers know — that music opens up pathways to creative thinking, sharpens our ability to listen and helps us weave together disparate ideas .

In this teaching resource, we suggest nine exercises to use music to inspire student writing — from creating annotated playlists and critical reviews to music-inspired poetry and personal narratives. Each idea pulls from Times reporting, Opinion pieces and multimedia on music to give students a place to start. The activities are categorized according to three genres: creative and narrative writing; informative and explanatory writing; and persuasive and argumentative writing.

How do you use music in your classroom? Let us know in the comments.

Creative and Narrative Writing

Exercise #1: Write a story or poem inspired by music.

One way you might let your students be inspired by music is to have them describe in words what they hear, a method Jean-Michel Basquiat employed in his poetry and paintings.

In “ Bowie, Bach and Bebop: How Music Powered Basquiat ,” Ekow Eshun writes:

In 1979, at 19, the artist Jean-Michel Basquiat moved into an abandoned apartment on East 12th Street in Manhattan with his girlfriend at the time, Alexis Adler. The home, a sixth-floor walk-up, was run-down and sparsely furnished. Basquiat, broke and unable to afford canvases, painted with abandon on the walls and floor, even on Ms. Adler’s clothes. The one item that remained undisturbed was Ms. Adler’s stereo, which had pride of place on a shelf scavenged from the street. “The main thing for us was having big speakers and a blasting stereo. That was the only furniture I purchased myself,” said Ms. Adler, who still lives in the apartment. When Basquiat was around, she recalled, “music was playing all the time.” On Thursday, the exhibition “Basquiat: Boom for Real” opened at the Barbican Center in London. The show focuses on the artist’s relationship to music, text, film and television. But it is jazz — the musical style that made up the bulk of Basquiat’s huge record collection — that looms largest as a source of personal inspiration to him and as a subject matter.

Invite your students to read the article and then listen to the Times-curated Spotify playlist “ The eclectic taste of Jean-Michel Basquiat ” as they view his art and read his poetry . Discuss what they notice about the musical influence in Basquiat’s work. How do the content, colors, textures and shapes in his paintings resemble the sounds they hear? How are these reflected in the words, phrases, mood and rhythm of his poems?

Next, have students listen to a song or playlist (perhaps one they created, one you created or one of these Times-curated ones) and, like Basquiat, let them write what they hear:

• describe the images that come to mind; • name the feelings and thoughts triggered by the imagery and sounds in the music; • mimic the pacing and rhythm through word choice, sentence structure and line breaks; • borrow the words, phrases or lines that resonate most; • or build on a theme or message.

Here’s an example of what one composer wrote as he listened to his own classical piece, “Become Desert”:

From the stillness around you a high glassy sound descends, like first light. Each new sound seems to breathe — emerging from and receding back into the stillness — and the glint of bells, like desert plants, here and there. Almost imperceptibly the music swells and continues falling in pitch. From somewhere above — like a gleam of metal, like sunlight emerging from behind a ridgeline — comes the sound of flutes. You are in a strange landscape. You don’t know how to read the weather or the light. You are unsure how long you will be here, or how challenging the journey may be.

To take this exercise a step further, students might use what they wrote while listening to music to develop a short story or poem. They might share their writing and song choices with the class so their classmates can analyze how music inspired their writing.

Exercise #2: Pen your own song or rap.

Invite students to write their own music about topics, events or themes you are studying in class. How can they summarize in song the role of the mitochondria , the main themes of “Romeo and Juliet” or the events that led to the Civil War?

Here’s an example from Julien Turner , 20, who produced this music video called “ XY Cell Life ” for a college biology class:

For inspiration, students might check out the Times “ Diary of a Song ” video series to see how songwriters and musicians like Zedd , Ed Sheeran and Justin Bieber make hits. What stands out to them about these songs? What are the artists’ processes for making music? How do they write lyrics and sounds that resonate with an audience? How do they communicate content and emotion?

You might have students simply write lyrics — like these students who wrote “Hamilton” hip-hop verses and these young people who summed up the year’s news in our annual “Year in Rap” challenge .

Or, invite them to make their own music videos or recorded songs. In this case, you might refer to use our lesson plan “ Project Audio: Teaching Students How to Produce Their Own Podcasts ,” which has a helpful section on audio editing and advice for gathering non copyrighted sound effects and music.

Exercise #3: Share what music means to you.

What role does music play in your students’ lives?

What are they listening to right now? What musicians and bands mean the most to them? What music inspires them? What song lyrics do they consider literature? Which artists do they believe are the future? Which do they think will stand the test of time?

We have published over 1,000 writing prompts for students , including many, like the questions above, dedicated to personal and narrative writing about music. You might have your students choose a question that speaks to them and read the related Times article. Then invite them to share their thoughts, stories, opinions and experiences in writing.

You can search “music” to find our newest music-related writing prompts here , which are open for comment indefinitely.

Informative and Explanatory Writing

Exercise #4: Connect songs to current events.

Music has always been a reflection of and window into society, culture and history — and the current era is no different. Hip-hop, folk, classical and even opera music draw on current events and politics for source material.

What connections can your students make between the music they listen to and current events? How does learning more about the context in which a song was written help them better understand it?

You might start by having students read and analyze how journalists make connections between music and current events every day. Take Childish Gamino’s latest video, “ This Is America ,” for instance. In a roundup of the best writing about this music video, Judy Berman writes:

But Glover’s graceful moves aren’t exactly the point. There’s plenty of messaging about race, violence and the entertainment industry in the song and video — which helps explain why fans and critics have devoted so much time to dissecting its references and debating its meaning.

And Doreen St. Félix from The New Yorker relates the video to the present day:

The video has already been rapturously described as a powerful rally cry against gun violence, a powerful portrait of black-American existentialism, a powerful indictment of a culture that circulates videos of black children dying as easily as it does videos of black children dancing in parking lots.

You might have students read the roundup or one of the articles it excerpts, or let them choose another topic or genre that interests them, such as:

Beethoven’s 200-Year-Old ‘Fidelio’ Enters Today’s Prisons Mouse on Mars at M.I.T.: A Symposium Becomes a Dance Party Eminem Lashes Out at Trump in Freestyle Rap Video New ‘Hamilton Mixtape’ Video Takes Aim at Immigration Celebrating Women’s Rights, ‘That Most American of Operas’ Watch 5 Moments When Classical Music Met Politics Can North Korea Handle a K-Pop Invasion? Review: Beyoncé Is Bigger Than Coachella

For whichever article they choose, students should consider: What current events does the music they read about reference? How do these allusions contribute to the artist’s message? What other themes in the music can they relate to what is happening in the world?

Then, challenge students to pair a song of their choosing with one or more Times articles and write an essay that explains the relationship between the song and the current or historical events.

Students might start by annotating song lyrics themselves or referring to Genius to find explicit connections and discover underlying themes that in some way relate to society, culture, history and politics. Students may also choose to research the artist to find out more about his or her background, beliefs and politics.

For help in writing the essay, what we call a text-to-text pairing , we also have a whole lesson plan that guides classes through the process of generating and writing about relevant connections between their studies and the world today, as well as dozens of example essays written by teenagers .

Exercise #5: Create an annotated playlist of songs related to a topic.

Every Friday, The Times publishes “ The Playlist ,” a weekly tour of notable new music and videos. Times pop music critics choose about a dozen of the week’s most popular or intriguing songs and music videos and write a short commentary for each. They even create a Spotify playlist of the songs each week.

You can use “The Playlist” as a model for students to compile their own annotated playlists — playlists with explanatory text or commentary for each song — related to a topic you are studying in class. It might be straightforward, such as songs that reference historical or current events, use a particular literary device or exhibit a specific musical technique. Or, the playlist could be more symbolic, like pieces that tell a story when played together, demonstrate a theme from a novel or capture the essence of a time period or setting. (You might use one of these as an example of a theme-oriented playlist.) Playlists could even be autobiographical, with students selecting songs that express aspects of their own identities.

Students can read through several of the past columns and listen to the playlists to determine what makes for compelling commentary. For example, on Billie Eilish’s and Khalid’s “Lovely,” Jon Pareles writes:

“Lovely” is the song of someone inextricably attached or trapped: “I hope someday I’ll make it out of here,” Billie Eilish sings with Khalid — not in dialogue or counterpoint, but in unison, as if they’re each others’ partner and burden. “Wanna feel alive outside/I can fight my fear.” The backdrop is piano and strings lingering on two chords; the melancholy never lifts, and at the end Khalid and Ms. Eilish share a chilling greeting: “Hello-welcome home.” J.P.

And on First Aid Kit’s “Fireworks,” Mr. Pareles writes:

First Aid Kit, a duo of sisters from Sweden who usually favor a folky, countryish approach — they’ve got a song named “Emmylou,” after Ms. Harris — turn to a gauzy retro sound in “Fireworks,” a song always about ending up lonely: “Why do I do this to myself every time/I know the way it ends even before it’s begun.” With a 1950s slow-dance beat and echoey guitars, it’s already nostalgic for the next failed romance. J.P.

Ask students: What do they notice about h ow the commentary is written? What does the writer include and why? How is it organized? What makes it interesting (or not)?

After students have curated their own playlists, they are ready to write song annotations. Some ingredients they should include in their writing are: a claim explaining how the song relates to the topic or theme; evidence from the song (e.g., lyrics, instruments, rhythm or melodies) illustrating their claim; and analysis that explains the significance of these aspects of the song.

Students can share their final playlists on Spotify so that everyone in the class can listen to and comment on them.

Exercise #6: Profile an artist in an imagined interview.

The Times Music section regularly profiles artists from different genres, time periods and corners of the globe. Students can use these articles and interviews as mentor texts before doing research and writing their own mini-biographies of a music figure they admire.

In an “imagined interview,” students, working individually or in pairs, play the part of both interviewer and interviewee. They do background research on an artist they select, come up with a list of questions and answers for the interview, and then write a profile on their subject.

To start, have students read one of these interviews with musicians:

Khalid, the Teenager With 5 Grammy Nominations: ‘They Got It Right This Year’ Jay-Z and Dean Baquet, in Conversation John Mayer Has More to Say: The Outtakes Bruce Springsteen on Broadway: The Boss on His ‘First Real Job’ Adele on ‘25’: Song by Song In Hip-Hop, Inspiration Arrived by Way of Kirk Franklin Gwen Stefani on Spirituality, Insecurity, Pharrell and ‘Truth’

Ask students: What types of questions did the interviewer ask? What subjects did the two discuss? What questions were missing from the interview that you wish were asked?

If you plan on having students write narratives based on their imagined interviews, they should also read at least one example of how Times writers write narratives based on interviews. Here are a few:

The 5 ‘Handsome Girls’ Trying to Be China’s Biggest Boy Band ‘I Could Barely Sing a High C’: Pretty Yende Finally Conquers Lucia For Milford Graves, Jazz Innovation Is Only Part of the Alchemy Dua Lipa Was Raised on Pop Bangers. Now She Writes Them. Valee, Kanye West’s New Signee, Is a Rapper Who Just Might Build You a Koi Pond Rafiq Bhatia Is Writing His Own Musical Language Ashley McBryde Takes Nashville, No Gimmicks Required

While reading, they should consider the following: What information did the reporter include and why do you think they made these choices? How did they effectively weave in biographical details to tell a story about the artist and the music?

Next, assign students to choose their own musical artist to interview and profile. The following steps can guide students through the process:

1. Do Your Research : To learn more about the artist you selected to interview, do an in-depth study of several song lyrics or an album, read published interviews with the artist, watch a video or listen to radio interviews to see how the artist speaks.

2. Prepare Your Questions : Consider this artist’s particular music and biography. What more do you want to know about the artist and his or her music? What in the songs or videos you studied struck you that you would like to ask about? For more inspiration, our lesson plan “ Beyond Question: Learning the Art of the Interview ” provides additional advice on how to conduct good interviews.

3. Conduct Your Imagined Interview : Based on your research of artists — their background, their music and the way they speak — imagine how they might respond to your questions. Be creative, but try to stay true to who the artist is. Alternatively, you could role-play the interview in partners, where one person is the interviewer and the other is the artist. It might be helpful to record the interview and take notes.

4. Write Your Article : You may choose to write your interview in a question and answer format , or create a narrative .

5. Share the Final Product : Share your imagined interviews with your classmates and reflect on the activity. Was your writing convincing to readers? What did you learn about writing artist profiles?

Persuasive and Argumentative Writing

Exercise #7: Review an artist, album or song.

Which artists, albums and songs can your students not stop talking about — either because they love them or hate them? Channel that energy into an argumentative essay using our culture review-writing lesson plan . In this lesson, students read Times reviews and heed advice from Times critics to write their own. They practice developing a clear claim, citing evidence and writing with a strong voice.

You might allow students to choose one of their favorite (or least favorite) artists or songs to practice writing passionately and knowledgeably about a subject. Or, challenge them to explore a genre of music they might not normally listen to and see what they can learn.

Consider having your students submit their finished pieces to our annual student review contest . They can read winning reviews from past years here .

Exercise #8: Weigh in on the latest criticisms, trends and news in music.

Music today incites opinions not just about the artists and albums themselves, but also about universal themes, like the music industry , social media , morality , the human condition , culture , the past and the future. “ Popcast ” is The Times’s podcast dedicated to discussing these very criticisms, trends and news in music.

You can invite students to weigh in on the music-related topics they care about most in a group writing activity that mimics the conversational style of this podcast. Here, they learn how to make a claim, develop it with evidence, write counterclaims and respond directly to one another in an informal and fun way.

First, you might start by having students listen to one full episode or excerpts from “ Popcast ” to analyze how the discussion unfolds. What background information is provided? How do the critics talk to and respond to one another? How do they open and close each episode?

Beyoncé and Kendrick Lamar Break Boundaries

Or, you might have students examine what a conversation like this looks like in writing. “ Kendrick Lamar Shakes Up the Pulitzer Game: Let’s Discuss ” by Times music editors provides a good example. The conversation begins:

JON PARELES To me, this prize is as overdue as it was unexpected. When I look at the Pulitzers across the board, what I overwhelmingly see rewarded are journalistic virtues: fact-gathering, vivid detail, storytelling, topicality, verbal dexterity and, often, real-world impact after publication. It’s an award for hard-won persuasiveness. Well hello, hip-hop. ZACHARY WOOLFE … But there is also wariness, which I join, about an opening of the prize — not to hip-hop, per se, but to music that has achieved blockbuster commercial success. This is now officially one fewer guaranteed platform — which, yes, should be open to many genres — for noncommercial work, which scrapes by on grants, fellowships, commissions and, yes, awards. PARELES That response is similar to many publishing-world reactions when Bob Dylan got the Nobel Prize in Literature — that a promotional opportunity was being lost for something worthy but more obscure, preferably between hard covers. A literary figure who had changed the way an entire generation looked at words and ideas was supposed to forgo the award because, well, he’d reached too many people? Do we really want to put a sales ceiling on what should get an award? The New York Times and The New Yorker already have a lot of subscribers … uh-oh.

Then, in small groups, have students come up with their own music topics worthy of debate. For inspiration, they might browse some of the past “Popcast” episodes.

You might then have them brainstorm some initial ideas and conduct research in the Times Music section to deepen and broaden their knowledge about the subject.

Next, invite them into a written conversation about their chosen topic. One student initiates the conversation and then each person in the group takes a turn responding to what each other writes — acknowledging their classmates’ remarks, voicing their own opinions, making connections and citing evidence to support or disagree with others.

Exercise #9: Write an editorial on a music-related topic.

Many musicians and music aficionados also contribute Opinion pieces to The Times, where they write passionately and persuasively about music’s influence in their lives, culture and society.

What music-related topics do your students care about? Do they believe music should be a required subject in school? What do they think today’s artists say about the world they live in? Can and should musicians’ work be separated from their personal lives?

Have your students write an editorial on a music-related topic that matters to them. We’ve written several lesson plans on teaching argumentative writing, including “ For the Sake of Argument: Writing Persuasively to Craft Short, Evidence-Based Editorials ,” “ I Don’t Think So: Writing Effective Counterarguments ” and “ 10 Ways to Teach Argument-Writing With The New York Times .”

You can pair any one of these lessons with music editorials as mentor texts, like the ones below:

A Note to the Classically Insecure The Real Song of the Summer Three Cheers for Cultural Appropriation The Heartbreak of Kanye West Is Music the Key to Success? Graceland, at Last The Songs That Bind

Students can also search for their own examples in the Music or Opinion sections. Or, refer to the many music-themed argumentative writing prompts we have published.

They might consider entering their finished editorials into our annual student editorial contest . And they can read essays from past winners here .

Other Music-Related Resources from The Learning Network

Lesson Plan | The Ten-Dollar Founding Father Without a Father: Teaching and Learning With ‘Hamilton’

Lesson Plan | Teaching With Protest Music

Teaching Close Reading and Compelling Writing With the ‘New Sentences’ Column

Music Composition Techniques and Resources

The following information on music composition techniques is excerpted from Eric Gould ’s Berklee Online course Creative Strategies for Composition Beyond Style .

As a composer, you will find that musical ideas come in various forms. You may be in the car and a rhythm might come to you. A snippet of a melody might occur to you while walking to the laundromat, or you may discover a chord or progression that you like and want to develop further. Any of these starting points can be the beginning of a highly evolved music composition.

Here we will discuss various music composition techniques and resources that will help you get started as you write your own piece of music.

How to Start a Music Composition

When you’re starting out with a blank piece of staff paper, there are infinite directions that you can go in. This is why you’ll want to begin with some parameters to narrow down those possibilities. Whatever your starting idea is, you’ll have several aspects to consider before embarking on your music composition. Some of the considerations are practical in nature and some are purely aesthetic, but having a grasp on the key issues from the beginning helps ensure the success of a project.

Let’s establish the things you should consider when kicking off a piece of music:

Why Are You Writing This Piece?

Having a purpose to do a project is one of the best ways to get you to sit in the chair and do the work. It also defines what you’re trying to accomplish musically. Think about how many great pieces of music are about some person, event, or story. When you have a motivating factor, it tends to lend musical clarity as well.

Ask yourself, what is the motivation for writing this piece of music? Is it…

- for your next recording?

- to commemorate something or an event?

- for a tribute?

- for a competition?

- as an exercise or etude?

Understanding how to use a template for the drafting phase can greatly enhance the compositional process. Templates allow you to get to the creative ideas faster by eliminating the steps involved in setting up a score just to record your ideas, and by helping to refine a method for getting to those creative ideas.

Here are three types of music composition templates:

Lead sheets.

- Two staves, with the melody on the top staff

- Harmony and rhythm on the bottom

Small Ensemble

- Three staves

- Horn voicings, or words and melodies on the top staff

- Rhythm section and bass lines on the bottom staves

- If voice and horns, you can use the bottom staves as a lead-sheet sketch

Large Ensemble

- Two grand staffs

- Allows for overlapping voicings or bass lines

Music Composition Software

Software templates are extremely helpful because, with a few clicks in a good software package, you can use the materials from your sketch directly in a score that you can build from the same file. Software templates also allow for easier editing, and allow you to take extensive notes on your piece or sketch as it evolves. Erasing the notes is as easy as selecting and deleting.

Sibelius and Finale

Sibelius and Finale are the two major music composition software programs, and Berklee Online offers courses that will give you thorough instruction on how to use them.

- Music Notation and Score Preparation using Sibelius Ultimate

- Music Notation and Score Preparation Using Finale

Berklee Online also has courses that will teach you how to use digital audio workstations (DAWs) such as Ableton Live , Pro Tools , Reason , Logic , and Cubase .

What is the Instrumentation?

Sometimes instrumentation is a practical consideration, and the piece of music is simply adapted to the resources and expertise available to the composer. Many times, however, the decision about instrumentation is part of the aesthetic of the piece. You may want to write a tune for your band to perform. Perhaps a string quartet has asked you to write a piece of music. Maybe a vocalist just wants a tune to add to their repertoire, and all you need to create is a lead sheet. Somewhere down the road, you may get an opportunity to write for a big band or full orchestra.

If you’re an inexperienced composer, you should start off writing for smaller ensembles, and then expand upon the arrangement. For example, you can go from a lead sheet to a quintet arrangement, to an octet, and then to a big band, building upon what you have at each step.

What Key or Tonal Center Will You Start in?

This decision can be influenced by many factors, including the instruments for which you’re writing.

How Long is the Piece?

Will your piece be a tune, a short arrangement, or an extended composition? You don’t want to start your composing career with a 30-minute-long masterwork. Build toward longer works by first coming up with a good melody, adding an intro and a coda, and then extending the piece. Many times, the length will be dictated by practical constraints like radio airplay, concert length, or budget.

What is the Form?

Defining the form of the music composition beforehand will help you to write the piece. If you know that you’re going to have an intro, bridge, and coda, you will approach the other sections in a way that will prepare for their incorporation into this larger framework. Planning the form in advance of the composition will also help you in deciding the character of the piece, as you will have to think about what will distinguish one section from another.

How will the Harmonic Rhythm Move? Statically or Modally? Are they:

- Long durations (more than one bar)?

- Short durations (one bar or less)?

- All of the above?

What do you want the character of the piece to be?

- Jagged and edgy?

- Traditional?

- Something else?

Do You Have a Time Signature in Mind?

If a song is a waltz, you would write it in 3/4. Funk and dance rhythms are most often in 4/4 time. Afro-Cuban rhythms are typically 6/8, 12/8, or 4/4. Any combination of beats per measure is possible. With compound meters (e.g., 7/8, 7/4, 9/8, etc.) the potential for complexity increases, and this can create a feeling of tension, but these time signatures can be very engaging. The bottom line is whether or not it sounds good!

Harmonic Rhythm

If you’re employing static or modal harmony, choose a chord or two that captures the character of what you’re trying to convey. If it’s a chord progression, decide what the duration of the chords (harmonic rhythm) will be.

Melodic Character

Sing or imagine a few beats that capture the character of what you’re trying to convey. Don’t worry about coming up with the perfect notes, and don’t try to write a piece—just come up with a fragment that has character, understanding that you can adjust it later.

In building the skill required to start from various points, limiting your options allows you to focus more on the process itself. You can transfer what you learned to a larger set of options as you grow. Like any other skill, compositional skills are cumulative—each thing you learn will prepare you for another set of challenges. Also, like any other skill, solid fundamentals are essential to sustained growth.

While this doesn’t mean feeding your musical fragment into your favorite sequencing software, the concept is very much the same. Sequencing involves repeating an idea with some sort of variation, most commonly involving pitch. The most common type of sequence involves simple transposition of the fragment to various starting points either in the key or tonal center or outside of it. If the transpositions occur within the confines of a key, then you will most likely need to change the intervallic relationship of the notes while retaining the basic shape.

Augmentation and Diminution

The value of a rhythmic element or an interval can be either increased (augmented) or decreased (diminished) upon repetition to create a variation. This is another widely used compositional device.

Pitch Augmentation (widening) and Pitch Diminution (contracting)

Likewise, you can widen the intervals within a melodic fragment, creating a sense of drama in the music while varying only one element.

Varied Harmonic Rhythm

One of the most common places for the harmonic rhythm to increase is in cadential passages. Increasing the frequency of harmonic change creates a sense of excitement and anticipation. Likewise, slowing down the harmonic momentum creates a sense of reflection, allowing the composer and listener to dig more deeply into the harmony of the moment.

I hope you find these music composition techniques helpful as you begin your piece. Keep in mind that there is so much more to learn in my 12-week Berklee Online course, Creative Strategies for Composition Beyond Style . Below I’ve included some resources to help you continue to learn music composition, including music composition books and more music composition courses from Berklee Online.

Music Composition Books

If you want to know how to learn music composition on your own, music composition books are a great place to start. Berklee Press has published several music composition books that will help you learn the basics of music notation. Here are a few music composition books from Berklee Press to check out:

- Music Notation: Preparing Scores and Parts

- Finale: An Easy Guide to Music Notation

- Berklee Contemporary Music Notation

Discover more music composition books from Berklee Press

Music Composition Courses

Berklee Online has more than a dozen music composition courses that will help you take your skills to the next level, all while composing professional work. You can also earn a professional certificate in Music Theory and Composition. Check out the following music composition courses:

- Contemporary Techniques in Music Composition 1

- Jazz Composition

- Music Composition for Film and TV 1

- Music Theory and Composition 1

- World Music Composition Styles

EARN A PROFESSIONAL CERTIFICATE IN MUSIC THEORY AND COMPOSITION

Related Articles

Berklee is accredited by the New England Commission of Higher Education "NECHE" (formerly NEASC).

Berklee Online is a University Professional and Continuing Education Association (UPCEA) award-winner fourteen years in a row (2005-2019).

What this handout is about

This handout features common types of music assignments and offers strategies and resources for writing them.

Writing about music

Elvis Costello once famously remarked that “writing about music is like dancing about architecture.” While he may have been overstating the case, it is often difficult to translate the non-verbal sounds that you experience when you listen to music into words. To make matters more difficult, there are a variety of ways to describe music:

- You can be technical and use terms from music theory. Example: “The cadential pattern established in the opening 16 bars is changed by a phrasal infix of two bars (mm. 22–24), thus prolonging the dominant harmony in the third phrase.”

- You can describe your feelings and personal reactions to the music. Example: “I felt that the chorus of the song was more gripping than the opening.”

- You can try to give a play-by-play description of what’s happening in the music. Example: “The saxophone soloist played a lot of scales in his improvisation, and the pianist added sparse chords to it.”

Without an extensive knowledge of music theory, you will most likely wind up doing a combination of 2 and 3. However, in all of these examples, you are only describing the music. Most music professors want you to analyze it. (So what if the dominant is prolonged? What is the effect and meaning of this?) How your description of music becomes an analysis of music depends on the kind of assignment you are answering. Consult our handout on understanding assignments for help in getting started.

Making an argument about music

Often, you will be asked to make an argument about a particular piece of music. In its most basic form, this is a statement about the piece with evidence that persuades your reader to agree with your argument. Clearly presenting your overall argument will help you organize your information around that main point. See our handout on argument.

For example, if you are writing about the historical importance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, you might develop an argument like this:

“Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, completed and first performed in 1824, is historically significant because of the ways that it challenged and expanded audiences’ expectations of symphonic structure.”

If this is your argument, then you should research what the audience expectations for a symphony might have been in 1824 based on other pieces of the time. How many movements did symphonies typically have? What were their formal structures? What were the performing forces? Once you understand the expectations of the day, you can identify the specific ways that Beethoven’s Ninth is different as well as what specific moments of the work (the entrance of the choir, the grand recapitulation which begins the last movement, etc.) you can cite as evidence for your argument. As you can see, making an argument in music involves historical or cultural evidence AND specific observations about the piece itself which combine to give a richly textured picture of the music and the composer, as well as the context from which they both emerged.

Even when making evaluative or interpretive claims about music, you should always provide evidence to support your claims. Music often evokes strong emotions in listeners, but these may not be the same for everyone. Music that you experience as “powerful” or “triumphant” may be experienced by another listener as “angry” or “violent.” Giving specific examples from the music will help explain your emotional reactions and give your reader a context for understanding them. For example, instead of saying

“The chorus of ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit” sounds angrier than the verses,’ you might argue that, “The added distortion in the guitar, increase in volume, and additional strain on Kurt Cobain’s voice give the chorus of ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ an angrier or more critical tone than the verses.”

Musical terminology

On occasion, or in some assignments, you may feel overwhelmed by the amount of technical vocabulary used to describe even the simplest musical gestures. Over the past thousand years, the study of music (particularly Western classical music) has acquired a host of specialized terms from Latin, Italian, German, and French, many of which remain untranslated in common usage. Do not be intimidated! If you have questions about these terms, ask your instructor or consult a reliable music dictionary . Typically the terms that will be most helpful to you and most essential in your writing will be ones that have been covered in class and explained in the textbook.

In addition to all the terms that you DO want to use, musical discourse also comes with some terms that professors and TAs might find particularly unhelpful. Generally these include casual value judgments such as “good,” “bad,” “lame,” “awesome,” “girly,” “soulful,” etc. These words may be fine when discussing an album with your friends, but they are not acceptable descriptors in academic writing. The most glaring of these words, however, and the one that your instructors will undoubtedly be on the lookout for is “authenticity” (and its close relatives “authentic,” “real,” genuine,” etc.). Instructors are particularly bothered by this word for two reasons:

- “Authenticity” is bound by a whole host of cultural and historical assumptions that make it impossible to pinpoint with any accuracy. Music that is considered “authentic” by one person might be considered deeply inauthentic to another and vice-versa. Similarly, music that was considered “authentic” by a group of fans in the 1960s may have lost its “authenticity” in the 1980s, but may have enjoyed a newfound “authenticity” in the early 2000s.

- “Authenticity” is not a claim about the substance of the music. Describing a performer as “authentic” is shorthand for referring to one’s personal conception of how musicians should look, sound, and act. What was it, specifically, that led you to interpret a particular artist as authentic? Was it an effective use of anti-commercial rhetoric in their lyrics or public persona? Was it their references to a particular tradition of music-making such as “folk” or “the blues”?

Examining the ways in which a particular style, band, or song came to be understood as “authentic” by its fans can be a valuable subject of inquiry, but any time you come across the word—in your or someone else’s writing—you should imagine it in scare quotes and try to more closely examine what the author is trying to say with the word in that particular context.

Common music assignments

Concert report.

You may have the opportunity to attend a live concert and report on it. Pay careful attention to the types of questions in the prompt. This is different from a music review in which you pass judgment on how “well” the players performed. Your professor might be okay with you adding your opinion, but most professors want you to listen closely to the music and try to describe it as accurately as possible using some of the vocabulary you’ve learned in class. A typical prompt usually asks for information about the performance venue, the performers, the music itself, and quite possibly your reactions to it. Make sure your report answers all of the questions!

Strategies: Read through the concert program. Sometimes there are program notes that provide background information and formal discussion of the music. This might act as a model for your own report. If your “concert” is more like a jazz jam session, you may not know the names of any of the pieces you hear. Sometimes you can just pick out your favorite performances to discuss. Elements to listen for might include (but are not limited to) instrumentation, variety of pieces performed, interaction of the performers, the setting (size, type, and location of the venue, acoustics of the space, etc.), audience reaction, and your own subjective interpretation.

Historical analysis: placing a piece in context

You may encounter this assignment in a music history or appreciation course. An instructor might ask you to pick a piece of music and discuss its historical context. This usually requires research, whether on the composer, the original performance, or the historical meaning. Sometimes you will be asked to relate the music itself to its historical setting. You may also need to make an argument about the piece. See our handout on writing history papers .

For example, you could write a paper relating how Mozart’s 1778 visit to Paris affected the compositions he wrote while there.

Strategies: Make sure you feel comfortable with the basic historical information before beginning an analysis. If you don’t know exactly what Mozart did and when, you will have trouble making any kind of argument.

If you are crafting an argument about how music relates to historical circumstances, then you should discuss those musical elements that most clearly support your argument. A possible thesis might be “Because Mozart wanted a job in Paris, he wrote a symphony designed to appeal to Parisian tastes.” If that is your argument, then you would focus on the musical elements that support this statement, rather than other elements that do not contribute to it. For example, “Though his Viennese symphonies featured a repeated exposition, Mozart did not include a repeat in the symphonies he composed in Paris, which conformed more closely to Parisian ideas about musical form at the time.” This observation might be more helpful to your argument than speculation about what he ate in Paris and how that influenced his compositional process.

Song analysis

How do the music and text (a song’s lyrics, an opera’s libretto) work together? You may complete this assignment for a music history or appreciation class. You should aim to make an argument about the song in question, using both text and music to support your claims.

Strategies: Look at how the text is set to music. This often requires you to first examine the text. Is it in a regular poetic form on its own? Does it have some type of pattern or other play with words? What is the meaning of the text? For more on word play and rhyme schemes, see our handout on poetry explications .

Now look at the text and listen to the music with it. Does the composer set it in an unusual way for the genre? Does the music seem to fit with the general meaning of the text, or does it seem to be at odds with it? Does the composer bring out certain words or lines of text? Why?

For example, you might say, “In the chorus of ‘Poses,’ Rufus Wainwright sets his first line of text to a long, arching melody, reminiscent of opera.” This describes the music and lets the reader know what part you are talking about and how you are hearing it (it reminds you of opera). Now tell the reader what is significant about this. What does it do for the meaning of the text? “The text suggests that ‘you said watch my head about it,’ but this rising operatic melody seems to suggest that the singer is really floating away and gone into another world.” Now your description of the music functions as evidence in an argument about how the song has two layers of meaning (text and music).

If you can do more theoretical music analysis, this might be a good opportunity to look at how the harmonies and phrase structures do or do not line up with the text. “Schubert sets the regular metrical pattern of the text to even four-bar phrases until he gets to the line ‘Ich will den Boden kuessen’ (I want to kiss the ground), whereupon it changes dramatically from there.” Once again, go further by explaining how this observation helps us understand the meaning of the text. “This technique extends the time spent on these lines and makes it seem like the singer is so frantically trying to reach green earth (through the snow), that he can’t maintain a steady pattern. He is overcome by desperate emotion when he thinks of seeing the ground again.” Now you have elucidated a moment in the music that casual listeners might have missed, and you have told them how, and why, it heightens the meaning of the text.

Performance/media comparison

For this assignment, you will compare different performances of a piece, different stagings of an opera, or different settings of a story (e.g. a stage version of an opera versus its movie adaptation). See our handout on comparing/contrasting for more tips on this type of assignment.

Strategies: Make sure you know the basic work before you begin comparing different versions of it. If you are comparing different instrumentalists’ or singers’ interpretations of a piece of music, then familiarize yourself with the piece. Listen to many different versions until you feel comfortable with it. Then you can focus on whatever elements of the individual performance the professor asks you to analyze (tempo, rubato, inflection, articulation, tone color, vibrato, etc.). Make sure you are familiar with these basic elements of music as well. Then ask yourself, what is the overall effect of the different performances? Do they interpret the piece differently? If they are not distinct in terms of overall interpretation, how are they different? How are these differences significant to your understanding or experience of the piece? Now you can use your musical elements to explain why. Remember to go beyond simply listing differences and similarities by making an argument about the music and its significance.

Let’s say you were asked to compare two performances of J.S. Bach’s Goldberg Variations: one recorded by Glenn Gould in 1955 and the second recorded by Jory Vinikour in 2001. You might observe that Gould’s performance is significantly faster than Vinikour’s and that Gould does not always repeat each section as the score indicates. How does Vinikour’s decision to play more slowly and with more repeats impact your experience of the piece? What might this tell you about the approach that Vinikour takes to Bach’s music versus the approach that Gould takes? You might also observe that Gould’s performance is on the piano while Vinikour’s is on the harpsichord. How does the instrumentation affect your experience of the piece? Is it historically significant that the two performers chose different instruments? Does this tell us something about the status of Baroque-period performance in the 1950s versus Baroque performance in the early 2000s?

In the case of opera, there are more elements beyond the music to take into consideration. Your assignment might ask you to focus on the staging (costume, set design, lighting, action). Remember that just as a play may be produced in different ways, there is no one “correct” staging of an opera. Some may be very traditional and attempt to portray the setting and time period used in the libretto (text). Others may try to make social commentary by “updating” the scenario to something that seems more relevant today. Others may try to comment upon the opera/story itself by making even more avant-garde productions.

For example, a production of Handel’s opera Giulio Cesare in Egitto (Julius Caesar in Egypt) might be set in Egypt in 47 BC, as it is in the original storyline. Or a modern opera producer and stage designer might collaborate and “update” it to appear to be about a Western superpower in the Middle East. Same exact text and music, different costumes, set design, lighting, and on-stage action. Does one production seem more believable to you? Does one make you think about the implications of the story more than the other?

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Bellman, Jonathan. 2007. A Short Guide to Writing About Music , 2nd ed. New York: Pearson Longman.

Herbert, Trevor. 2009. Music in Words: A Guide to Researching and Writing About Music . New York: Oxford University Press.

Holoman, D. Kern. 2014. Writing About Music: A Style Sheet , 3rd ed. Oakland: University of California Press.

Wingell, Richard. 2009. Writing About Music: An Introductory Guide , 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Music | All-Star Orchestra

Course: music | all-star orchestra > unit 1.

- Lesson 1: Note values, duration, and time signatures

- Lesson 2: Rhythm, dotted notes, ties, and rests

- Lesson 3: Meters in double and triple time, upbeats

- Lesson 4: Meters in 6, 9, and 12

- Lesson 5: Review of time signatures – Simple, compound, and complex

- Lesson 6: Constant versus changing time, adding triplets, and duplets

Glossary of musical terms

Want to join the conversation.

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Music and Me: Visual Representations of Lyrics to Popular Music

- Resources & Preparation

- Instructional Plan

- Related Resources

You can get your students to practice critical literacy without resorting to book interpretation. Instead, using texts such as song lyrics can engage students, while related images can be used as interpretive tools. In this lesson, students choose a song that they like. Then, they interpret the meaning of the lyrics by making personal connections, critically analyzing their interpretations, and planning how to represent them with images. After collecting digital images, they use Windows Movie Maker to create a photomontage movie. Then, students share their movies and reflect on both their own and their peers' work.

Featured Resources

Music and Me Idea Map : This tool allows students to visually organize details about their song’s lyrics, as well develop a sequence of ideas for their photomontage movie.

From Theory to Practice

- Students working with visual "texts" need to understand the technical skills to manipulate text, image, and color-but they also need to understand how these elements work together to create meaning.

- It is important for teachers to model how to talk about visual texts by looking at them with students and pointing out how these different elements have been used to create meaning. Explicit articulation of these ideas helps students assess their own work more thoughtfully and completely.

- Being visually literate means that a student can produce and "read" visual texts.

- To be visually literate, a student should actively engage in asking questions and seeking a variety of answers and interpretations of a visual project.

Common Core Standards

This resource has been aligned to the Common Core State Standards for states in which they have been adopted. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, CCSS alignments are forthcoming.

State Standards

This lesson has been aligned to standards in the following states. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, standard alignments are not currently available for that state.

NCTE/IRA National Standards for the English Language Arts

- 1. Students read a wide range of print and nonprint texts to build an understanding of texts, of themselves, and of the cultures of the United States and the world; to acquire new information; to respond to the needs and demands of society and the workplace; and for personal fulfillment. Among these texts are fiction and nonfiction, classic and contemporary works.

- 3. Students apply a wide range of strategies to comprehend, interpret, evaluate, and appreciate texts. They draw on their prior experience, their interactions with other readers and writers, their knowledge of word meaning and of other texts, their word identification strategies, and their understanding of textual features (e.g., sound-letter correspondence, sentence structure, context, graphics).

- 6. Students apply knowledge of language structure, language conventions (e.g., spelling and punctuation), media techniques, figurative language, and genre to create, critique, and discuss print and nonprint texts.

- 8. Students use a variety of technological and information resources (e.g., libraries, databases, computer networks, video) to gather and synthesize information and to create and communicate knowledge.

- 12. Students use spoken, written, and visual language to accomplish their own purposes (e.g., for learning, enjoyment, persuasion, and the exchange of information).

Materials and Technology

- Computers with Internet access

- Windows Movie Maker

- Overhead projector

- Digital or disposable cameras

- Scanner (optional)

- LCD projector (optional)

- Headphones (optional)

- Using Movie Maker to Create Photomontage Movies

- Music and Me Idea Map

- Music and Me Project Instructions

- Rubric for Photomontage Movie

- Self-Reflection on the Music and Me Project

- Music and My Friends: Evaluating Classmate’s Work

Preparation

Student objectives.

Students will

- Make text-to-self connections by examining the lyrics to a song they have chosen and describing how they relate to the words and music

- Express and organize their thoughts by using graphic organizers

- Practice interpretation by reading song lyrics both with and without music and by choosing images that represent the text-to-self connections they have made

- Increase their technical skills by learning how to acquire images digitally and how to use Windows Movie Maker

- Apply what they have learned by creating a photomontage movie

- Analyze their own work as well as the work of their peers by looking at the movies and filling out evaluation forms

Note: Prior to this session, students should choose their song and listen to it.

Homework (due at the beginning of Session 2): Students should bring a copy of the lyrics they have chosen to class.

Homework (due at the beginning of Session 3): Students should bring in a recorded version of the song they have chosen as well as their filled-in Idea Maps.

Homework: Students can prepare for the moviemaking sessions at home by gathering images to use in their movies. The questions they have answered and their Idea Maps should serve as guidelines for the type of images they want to use. Students can assemble images in a variety of ways, such as by:

- Taking photos using either a digital or conventional camera (if they use the former, they should make a photo CD; if they use the latter, they should make a CD or scan the images).

- Collecting images from magazines or books (again, these will need to be scanned).

- Searching the Internet for images. Please note that you should consult your school’s guidelines regarding safe Internet usage before allowing students to conduct an open search. In addition, your students should access and follow Copyright and Fair Use Guidelines for School Projects .

If students have difficulty accessing equipment, provide a few disposable cameras for them to use. You might also want to refer students to the training information on Tech-Ease: Images Q & A for Mac and PC so that students can practice using the software if they choose. You should provide at least a week for students to collect their images.

Sessions 4 through 6

Note: During these sessions, students will import the images into Windows Movie Maker and make a photomontage movie to play along with the music to their song. They should bring all of the images they have collected for homework. If you have not already done so, distribute Using Movie Maker to Create Photomontage Movies to students.

- You can find many other ideas for the use of a digital camera in the classroom on Using Digital Cameras in the Classroom . Although the lessons are mainly for elementary students, they can be modified to high school standards.

- Technology: Movie Maker Projects lists a number of additional projects you can complete with your students using Movie Maker.

- See Using Technology to Analyze and Illustrate Symbolism in Night for more ideas about using digital images.

Student Assessment / Reflections

- Have students turn in their Music and Me Project Instructions sheets and the two completed Music and Me Idea Maps . Check to see how well students were able to:

Make text-to-self connections by examining the lyrics to a song they chose Express and organize their thoughts by using graphic organizers Interpret the song lyrics both with and without music

- Use the Rubric for Photomontage Movie to assess students’ videos. You should also look at the Self-Reflection on the Music and Me Project sheets to see how well students achieved their goals in creating the movies.

- Students practice assessing both their own and their peers’ work using the self-reflection sheet and the Music and My Friends: Evaluating Classmate’s Work ; you may choose to collect these and look at how well students are able to offer suggestions and insight. You can also observe informally while students are working with their partners during class sessions.

- Calendar Activities

- Lesson Plans

Add new comment

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Music Matters Blog

Inspiring Creativity

The Perfect Assignment Sheet for Piano Students

January 26, 2017 by natalie 1 Comment

Somehow I just came across this fabulous compilation of free downloadable assignment sheets that Amy Chaplin, of the Piano Pantry blog , has either created or adapted! Even though I always create custom assignment books that correlate with our practice incentive theme for the year, I absolutely love the variety of ideas that Amy incorporates into these sheets. Whether you’re looking for an assignment sheet that includes helpful theory concepts, or one that outlines technique warm-ups, or even one that is based on specific practice tips, you’re sure to find one that is just the right fit for your students and studio!

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Reader Interactions

January 26, 2017 at 8:54 am

What a lovely surprise, Natalie. Thank you! There are more to come too. I only have about 60% of the ones I’ve made uploaded at the moment but plan on finishing it in the next few weeks. Thanks for sharing!

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Free Resources

- Piano Music for Left Hand

- New Free Tortoises Beginner Piano Solo with Teacher Duet

- Free Piano Music from Composer Albert Rozin

- Free Resources from the Creative Piano Teacher Website

- 3,000 Piano Repertoire Videos

Click for more Free Resources

Product Search

Blog archives, blog categories.

Advertisers and Affiliates

RSS Feed | YouTube | Twitter | Pinterest | LinkedIn | Facebook | Email

Blog content by Natalie's Piano Studio | © 2005-2024. All Rights Reserved. Sitemap | Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions | Advertising Opportunities

- QC Resources

- Music Library

Meaning In Music – Intro Lesson & Poster Assignment

This ‘Meaning In Music’ musical assignment is a great way to engage your students by analyzing the impact of music within our society. Your students will be asked to reflect and respond to how music is used within our society, and how music deeply impacts our lives and everyday experiences. This resource includes both a ready-to-print package AND a Google Slides version of the project and introduction lesson.

This resource includes:

– Introduction Lesson & Teacher Answer Key, with suggestions of potential student responses

– Meaning In Music Poster Assignment, where students will be asked to choose one song that has had an impact on our society. Students will be asked to create a poster representing their song, and write a paragraph outlining the impact of this song including how 3 musical elements are used to express the meaning of their chosen song. The assignment includes:

- Poster Assignment Instructions & Rubric

- Song Idea Brainstorm

- Brainstorming/Planning Pages (for poster design and paragraph writing)

- Poster & Paragraph Final Copy Template

– Extension Activity: Listening Response Worksheet

BONUS: 3 photos of a project exemplar

A rubric is also included for assessment, with a success criteria checklist that students can refer too while completing the assignment and before they submit.

Purchase of this product includes 2 versions of this assignment: a printable PDF and a Google Slides version, that is intended to be used on Google Apps such as Google Slides and Google Classroom. A ‘Google Classroom Help’ guide is also included to help answer any questions you may have regarding uploading the product correctly for your students.

Get this resource in French

You might also like...

Related products.

Soundtrack of my Life – Music Throughout the Decades

Soundtrack of my Life MEGA BUNDLE

Impactful Musicians Throughout History – Intro Lessons and PowerPoint Project

Middle School Music Project BUNDLE Volume 2

Copyright 2023 Teach From The Stage. All Rights Reserved. Website by MargaretSlater.co

The New Music Assignment Book

by Lauren Lewandowski | Jul 30, 2020 | Teaching/Practice Tips

This post may contain affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. That means I make a small commission (at no additional cost to you) if you purchase something from an affiliate link.

As a new school year approaches and the pandemic continues, I know many students are in need of something to lift their spirits right now! I created this new Music Assignment Book to include practice goals for students, reference sheets, and even spaces to highlight positive elements from music lessons. Students need this right now!

The Music Assignment Book Includes:

1. a beautiful, colorful cover to brighten anyone’s mood.

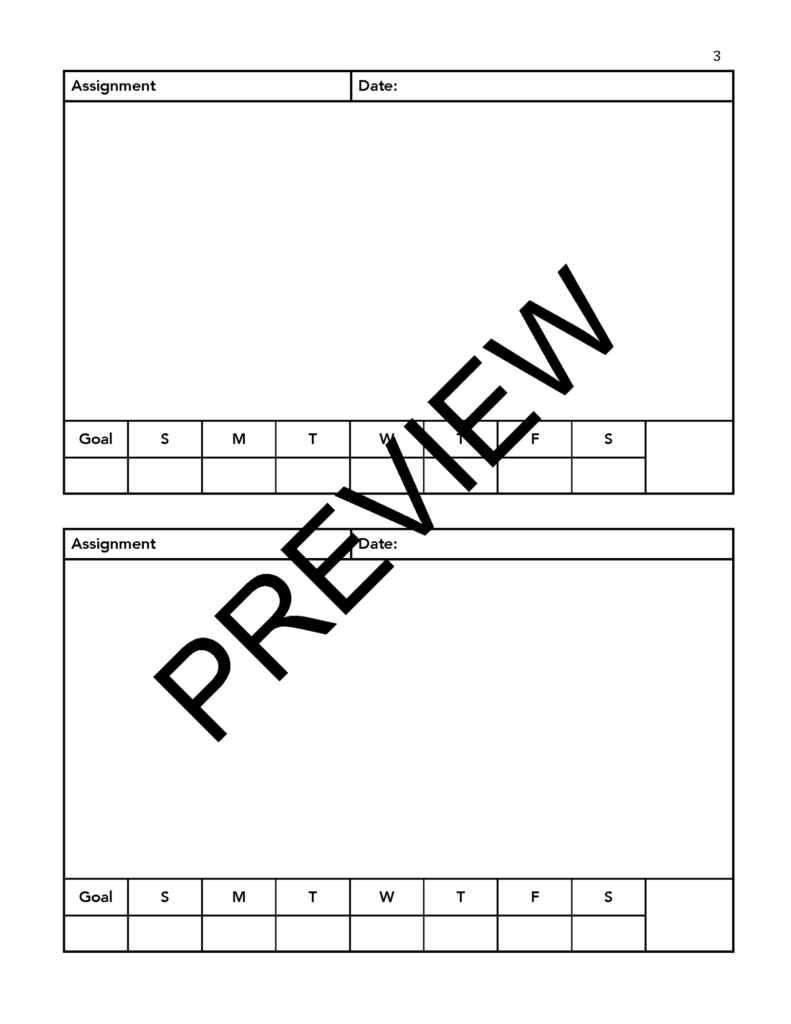

2. Fifty-two weeks of assignment pages with space to make a practice goal for the week

3. a practice log is included with each weekly assignment..

Teachers and set the weekly practice goal as a particular number of days to practice, or set the goal as a total number of minutes for the student to practice during the week. Use the empty box at the end of the weekly schedule to award students. Younger students may enjoy receiving a sticker if their weekly goal is met. Other ideas include giving students a letter grade or stars based on how their weekly goal was met. For example, the teacher can tell the student they receive 3 stars if the goal was met, 1-2 stars if the goal was partially met, or 0 stars if there was no practice. If teaching online lessons, students may write down their own assignment and discuss their practice with teachers the following week. Students can then grade their own practice!

4. An appendix with:

- Common musical terms and tempo markings (Great reference for online lessons)

- Rhythm charts with note and rest values for simple and complex meter

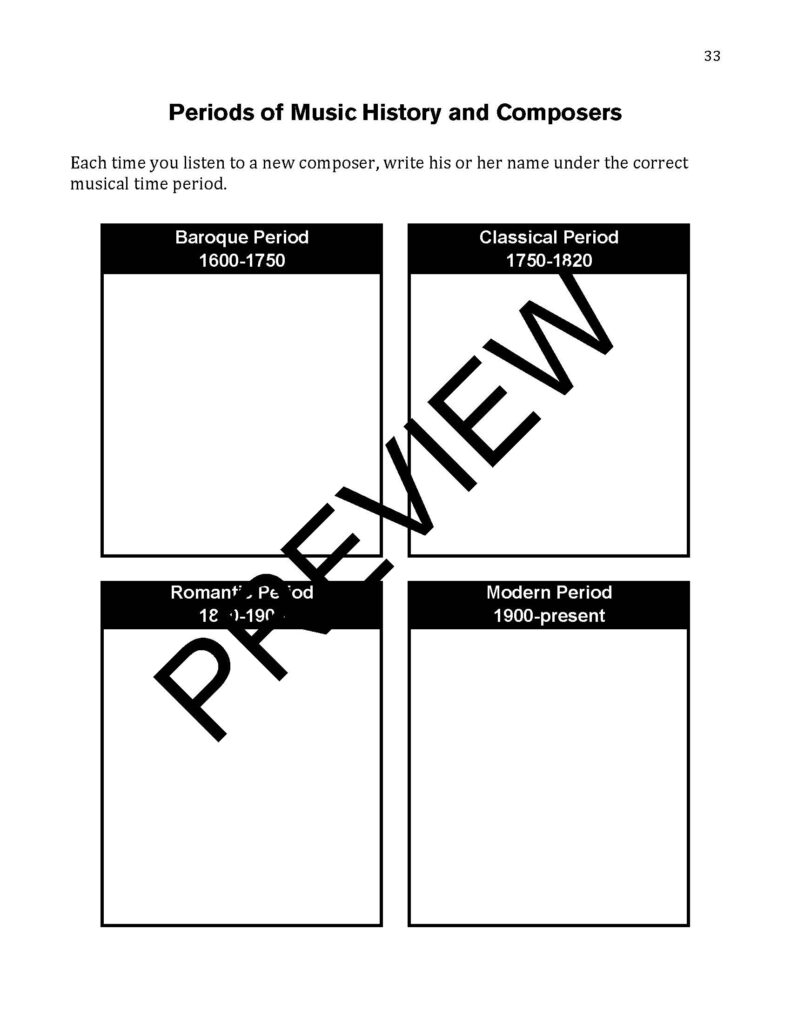

- Students can record composers they learn within the four musical time periods

- Space to notate favorite pieces and special achievements (Students really need to highlight anything positive right now!)

- Blank staff paper

- Blank paper for notes

Buy the Music Assignment Book

Lauren teaches piano to students of all ages in New Orleans, LA. Teaching is her passion. She enjoys creating resources for her students and is the author of Ready for Theory®.

Related posts:

Quick Search

Blog categories.

- Games & Activities

- Group Lessons

- Monthly Updates

- Online Lessons

- Popular Posts

- Ready for Theory

- Repertoire Lists

- Teaching/Practice Tips

- Uncategorized

- Skip to right header navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Analyzing a Song – So Simple Every Student Can Do It

December 13, 2022 // by Lindsay Ann // 2 Comments

Sharing is caring!

English teachers, teaching your students how to analyze song lyrics needs to be a “go-to” strategy, a step toward deeper analysis of more complex texts .

Whether you’re teaching poetry, persuasive essays, or some other writing unit, analyzing song lyrics will give your students an opportunity to look at the different ways that language can be used to capture emotions and tell stories .

This close reading process will also help improve their vocabulary and grammar skills while they are having fun!

Here are some tips on how to teach students to analyze song lyrics so that they can gain valuable writing knowledge through a familiar medium they love!

Analysis of Song Lyrics

Taylor Swift makes analyzing song lyrics in the classroom easy peasy. Like her or not, you can count on her to write songs that tell a story, are layered in deep meaning, and littered with Easter eggs that are fun to try and collect (even for the non-Swifties).

Taylor Swift’s “ Anti Hero” is a fun student-friendly song to bring into the classroom to practice analysis skills.

With callbacks to songs on other albums in lines like “I have this thing where I get older but just never wiser,” you can challenge students to analyze the development of a theme across multiple texts (helloooo higher level DOK and those really tricky to meet standards!).

Lyrics like “I’m the problem; it’s me” coupled with the title setup an opportunity to teach the concept of anti-hero (I especially like the idea of teaching about anti-heroes after teaching about the hero’s journey) and challenging students to analyze how Swift herself could be seen as this archetype by analyzing other songs and conducting online research.

“Anti Hero” also has what appear to be two references to pop culture ( 30 Rock and Knives Out ) that had even the swiftest of Swifties stumped online. These references are an accessible way to introduce the idea of allegory.

Taylor has really teed up the song analysis practice in English classrooms to be endless with so many rabbit holes to go down at every turn!

Song Meaning “Hallelujah”

Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” has a deep meaning making it a popular choice for teaching song analysis. The meaning of Hallelujah is about someone who was deeply in love and is mourning the guilt of the loss of that love .

The song can teach students how to analyze lyrics by pointing out that even though it doesn’t say so explicitly, this is a song about a break-up .

They can also learn other aspects of reading literature, like examining tone and form. Analyzing song lyrics enables students to apply what they’ve learned as they read other texts or songs.

After reading a poem or listening to a song’s lyrics, students should be able to answer questions like:

- Who is speaking?

- How do you know?

- What do you think the speaker’s feelings are?

- What does this tell you about their personality?

- Do these feelings make sense for the situation?

Good Songs to Analyze

When choosing good songs to analyze remember these three things:

- Choose a song that tells a story

- A song with a deep meaning or theme that challenges students’ inferential thinking skills works best

- Pick songs that students will know and be excited to listen to (that means that while “We Didn’t Start the Fire” is technically a great song for analysis, it might not be the most engaging for your students)

Here are some songs for teaching song analysis that will not only help you teach important analysis skills but also engage and delight your students:

- “ Pray for Me ” by the Weeknd ft. Kendrick Lamar

- “ Thunder ” by Imagine Dragons

- “ Bohemian Rhapsody ” by Queen (this one is suitable for older students)

- “ Born This Way ” by Lady Gaga

- “ Getting Older ” by Billie Eilish

- “ Drivers License ” by Olivia Rodrigo

- “ This is America ” by Childish Gambino/Donald Glover

- “ Matilda ” by Harry Styles

- “ Victoria’s Secret ” by Jax (does have some profanity – I’ve linked the “clean” version)

- “ Vacation ” by The Dirty Heads (does say “shit”)

How to Analyze a Song

Teaching students how to analyze a song is similar to teaching poetry or literary analysis, but using songs disguises the learning as a fun activity making it really engaging and accessible for all learners.

Start by having students listen to their song twice .

- Instruct them to listen through for the first time just for enjoyment and to follow along with the printed lyrics (or digital if you have a way for students to access the lyrics online).

- Then have them listen a second time but this time have them highlight and circle words and phrases that they think are important and interesting.

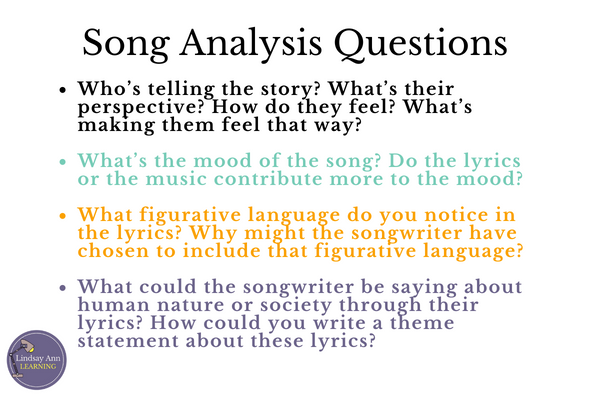

Challenge students to consider the following questions during their second time listening and to annotate the lyrics as they go:

- Who’s telling the story? What’s their perspective? How do they feel? What’s making them feel that way?

- What’s the mood of the song? Do the lyrics or the music contribute more to the mood?

- What figurative language do you notice in the lyrics? Why might the songwriter have chosen to include that figurative language?

- What could the songwriter be saying about human nature or society through their lyrics? How could you write a theme statement about these lyrics?

Once you’ve gotten your students started with the analysis process, make sure to involve your students. Ask them what they notice and use their insights to build discussion. Have them write a summary of the song or write a detailed analysis or work on a more creative, visual response.

Song & Poem Analysis Paired Text Lesson Plans

Make close reading, textual analysis and literary analysis of songs (and poems) less intimidating with these detailed, CCSS-aligned close reading song analysis lesson plans for paired texts . Integrated close reading, text-based writing, speaking, listening, and inquiry skills, make these lessons both engaging and worthwhile.

To help you save prep time, I’ve put together some awesome lessons for you HERE , including:

- Carrie Underwood’s song “Cry Pretty” & Macklemore & Ryan Lewis’ song “Growing Up”

- William Ernest Henley’s poem “Invictus” & Imagine Dragons’ song “Whatever it Takes”

- Maya Angelou’s poem “Still I Rise” and Tupac’s song “Still I Rise”

- Stephen Dobyns’ poem “Loud Music” and Incubus’ song “Dig”

- “Anti-Hero” by Taylor Swift

- “Boulevard of Broken Dreams” by Green Day and “Brick by Boring Brick” by Paramore

- “Hotel California” by the Eagles and “Stairway to Heaven” by Led Zeppelin

- Protest Songs

- “Mad World” by Tears for Fears and “A Million Dreams” sung by Pink / The Greatest Showman

Wrapping Up

When students analyze songs, they think about its overall impact.

What makes this song great, and why do you like it? What is it about this song that makes it stand out?

Thinking through these ideas with easily-accessible texts makes transferring their skills and knowledge to literature (ya know, the kind with the capital L ) easier.

They’ll have practice analyzing craft moves like figurative language and allegory, but they’ll also have practice with those more complex reading strategies like making inferences and connections .

Have a song you think would be perfect to analyze in the classroom? I’d love to hear about it! Drop me a comment below to share!

Hey, if you loved this post, you’ll want to download a FREE copy of my guide to streamlined grading .

I know how hard it is to do all the things as an English teacher, so I’m excited to share some of my best strategies for reducing the grading overwhelm.

About Lindsay Ann

Lindsay has been teaching high school English in the burbs of Chicago for 19 years. She is passionate about helping English teachers find balance in their lives and teaching practice through practical feedback strategies and student-led learning strategies. She also geeks out about literary analysis, inquiry-based learning, and classroom technology integration. When Lindsay is not teaching, she enjoys playing with her two kids, running, and getting lost in a good book.

Related Posts

You may be interested in these posts from the same category.

Book List: Nonfiction Texts to Engage High School Students

12 Tips for Generating Writing Prompts for Writing Using AI

31 Informational Texts for High School Students

Project Based Learning: Unlocking Creativity and Collaboration

Empathy and Understanding: How the TED Talk on the Danger of a Single Story Reshapes Perspectives

Teaching Story Elements to Improve Storytelling

Figurative Language Examples We Can All Learn From

18 Ways to Encourage Growth Mindset Versus Fixed Mindset in High School Classrooms

10 Song Analysis Lessons for Teachers

Must-Have Table Topics Conversation Starters

The Writing Process Explained: From Outline to Final Draft

The Art of Storytelling: Techniques for Writing Engaging Narratives

Reader Interactions

March 28, 2023 at 4:50 am

Jungle by Tash Sultana

[…] this post, I will share with you 20 must-read Classic novels for high school students and some modern texts that pair well with some of these well-loved […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Western Harmonic Practice I: Diatonic Tonality

6 Introduction to Four-Part Harmony and Voice Leading

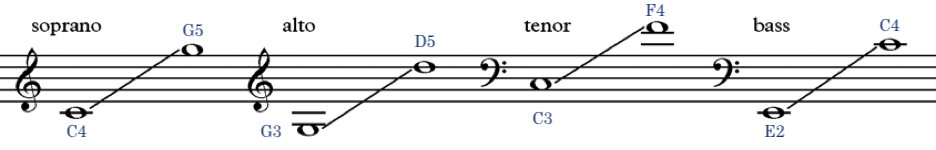

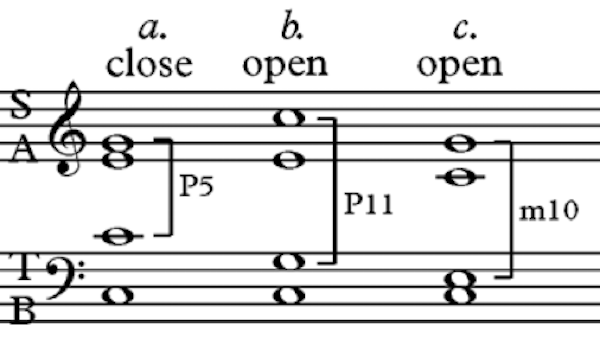

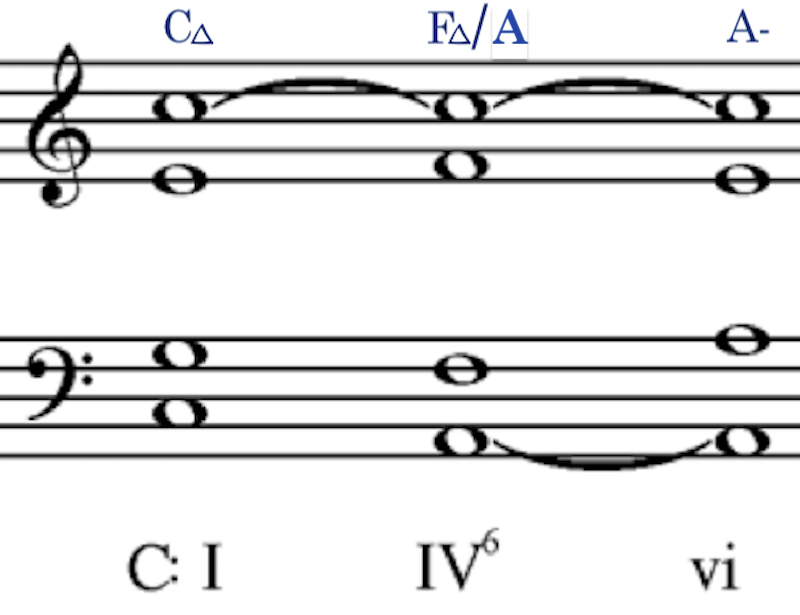

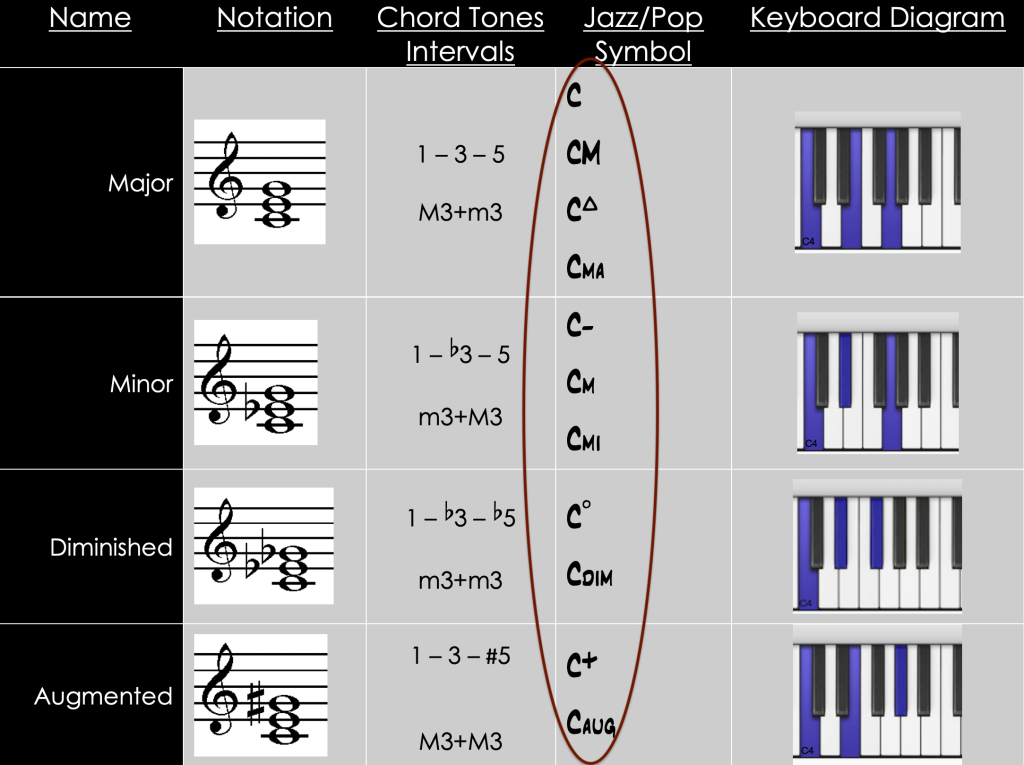

- Four-Part Harmony is the study and application of tonality through harmonic progressions in four voices (parts).

- Voicing is the process of taking a given chord and assigning/arranging the chord tones to each of the four voices (parts)

- Good spacing helps to insure balance and homogenous blending of the harmony.

- There are two different types of spacing: ( closed and open ).

- The voices , while sounding a complete chord, are also to be considered as independent lines, much like we learned in our study of counterpoint , and the process of moving the voices from one chord to the next is called voice leading .

- As with our study of counterpoint, the study of harmony in four part SATB chorale style is not designed to create good music but rather develop skills and reenforce basic musical concepts through active learning and creation, as well as to serve as a foundation upon which to build further knowledge. These exercises are analogous to lifting weights as part of athletic training, or the study of calculus as part of training in engineering, etc. Thus, these exercises in and of themselves are not intended to produce anything close to finished songs or well-constructed compositions. However, and what is an important challenge, one should strive to make them as musical as possible within the limited guidelines and resources provided.

Philosophy and Application

Pedagogical (teaching) philosophy.