- Privacy Policy

Home » What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Definition:

Hypothesis is an educated guess or proposed explanation for a phenomenon, based on some initial observations or data. It is a tentative statement that can be tested and potentially proven or disproven through further investigation and experimentation.

Hypothesis is often used in scientific research to guide the design of experiments and the collection and analysis of data. It is an essential element of the scientific method, as it allows researchers to make predictions about the outcome of their experiments and to test those predictions to determine their accuracy.

Types of Hypothesis

Types of Hypothesis are as follows:

Research Hypothesis

A research hypothesis is a statement that predicts a relationship between variables. It is usually formulated as a specific statement that can be tested through research, and it is often used in scientific research to guide the design of experiments.

Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis is a statement that assumes there is no significant difference or relationship between variables. It is often used as a starting point for testing the research hypothesis, and if the results of the study reject the null hypothesis, it suggests that there is a significant difference or relationship between variables.

Alternative Hypothesis

An alternative hypothesis is a statement that assumes there is a significant difference or relationship between variables. It is often used as an alternative to the null hypothesis and is tested against the null hypothesis to determine which statement is more accurate.

Directional Hypothesis

A directional hypothesis is a statement that predicts the direction of the relationship between variables. For example, a researcher might predict that increasing the amount of exercise will result in a decrease in body weight.

Non-directional Hypothesis

A non-directional hypothesis is a statement that predicts the relationship between variables but does not specify the direction. For example, a researcher might predict that there is a relationship between the amount of exercise and body weight, but they do not specify whether increasing or decreasing exercise will affect body weight.

Statistical Hypothesis

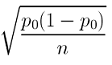

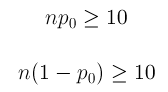

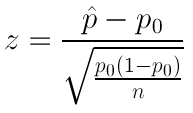

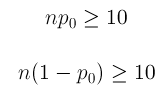

A statistical hypothesis is a statement that assumes a particular statistical model or distribution for the data. It is often used in statistical analysis to test the significance of a particular result.

Composite Hypothesis

A composite hypothesis is a statement that assumes more than one condition or outcome. It can be divided into several sub-hypotheses, each of which represents a different possible outcome.

Empirical Hypothesis

An empirical hypothesis is a statement that is based on observed phenomena or data. It is often used in scientific research to develop theories or models that explain the observed phenomena.

Simple Hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a statement that assumes only one outcome or condition. It is often used in scientific research to test a single variable or factor.

Complex Hypothesis

A complex hypothesis is a statement that assumes multiple outcomes or conditions. It is often used in scientific research to test the effects of multiple variables or factors on a particular outcome.

Applications of Hypothesis

Hypotheses are used in various fields to guide research and make predictions about the outcomes of experiments or observations. Here are some examples of how hypotheses are applied in different fields:

- Science : In scientific research, hypotheses are used to test the validity of theories and models that explain natural phenomena. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a particular variable on a natural system, such as the effects of climate change on an ecosystem.

- Medicine : In medical research, hypotheses are used to test the effectiveness of treatments and therapies for specific conditions. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a new drug on a particular disease.

- Psychology : In psychology, hypotheses are used to test theories and models of human behavior and cognition. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a particular stimulus on the brain or behavior.

- Sociology : In sociology, hypotheses are used to test theories and models of social phenomena, such as the effects of social structures or institutions on human behavior. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of income inequality on crime rates.

- Business : In business research, hypotheses are used to test the validity of theories and models that explain business phenomena, such as consumer behavior or market trends. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a new marketing campaign on consumer buying behavior.

- Engineering : In engineering, hypotheses are used to test the effectiveness of new technologies or designs. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the efficiency of a new solar panel design.

How to write a Hypothesis

Here are the steps to follow when writing a hypothesis:

Identify the Research Question

The first step is to identify the research question that you want to answer through your study. This question should be clear, specific, and focused. It should be something that can be investigated empirically and that has some relevance or significance in the field.

Conduct a Literature Review

Before writing your hypothesis, it’s essential to conduct a thorough literature review to understand what is already known about the topic. This will help you to identify the research gap and formulate a hypothesis that builds on existing knowledge.

Determine the Variables

The next step is to identify the variables involved in the research question. A variable is any characteristic or factor that can vary or change. There are two types of variables: independent and dependent. The independent variable is the one that is manipulated or changed by the researcher, while the dependent variable is the one that is measured or observed as a result of the independent variable.

Formulate the Hypothesis

Based on the research question and the variables involved, you can now formulate your hypothesis. A hypothesis should be a clear and concise statement that predicts the relationship between the variables. It should be testable through empirical research and based on existing theory or evidence.

Write the Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis is the opposite of the alternative hypothesis, which is the hypothesis that you are testing. The null hypothesis states that there is no significant difference or relationship between the variables. It is important to write the null hypothesis because it allows you to compare your results with what would be expected by chance.

Refine the Hypothesis

After formulating the hypothesis, it’s important to refine it and make it more precise. This may involve clarifying the variables, specifying the direction of the relationship, or making the hypothesis more testable.

Examples of Hypothesis

Here are a few examples of hypotheses in different fields:

- Psychology : “Increased exposure to violent video games leads to increased aggressive behavior in adolescents.”

- Biology : “Higher levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere will lead to increased plant growth.”

- Sociology : “Individuals who grow up in households with higher socioeconomic status will have higher levels of education and income as adults.”

- Education : “Implementing a new teaching method will result in higher student achievement scores.”

- Marketing : “Customers who receive a personalized email will be more likely to make a purchase than those who receive a generic email.”

- Physics : “An increase in temperature will cause an increase in the volume of a gas, assuming all other variables remain constant.”

- Medicine : “Consuming a diet high in saturated fats will increase the risk of developing heart disease.”

Purpose of Hypothesis

The purpose of a hypothesis is to provide a testable explanation for an observed phenomenon or a prediction of a future outcome based on existing knowledge or theories. A hypothesis is an essential part of the scientific method and helps to guide the research process by providing a clear focus for investigation. It enables scientists to design experiments or studies to gather evidence and data that can support or refute the proposed explanation or prediction.

The formulation of a hypothesis is based on existing knowledge, observations, and theories, and it should be specific, testable, and falsifiable. A specific hypothesis helps to define the research question, which is important in the research process as it guides the selection of an appropriate research design and methodology. Testability of the hypothesis means that it can be proven or disproven through empirical data collection and analysis. Falsifiability means that the hypothesis should be formulated in such a way that it can be proven wrong if it is incorrect.

In addition to guiding the research process, the testing of hypotheses can lead to new discoveries and advancements in scientific knowledge. When a hypothesis is supported by the data, it can be used to develop new theories or models to explain the observed phenomenon. When a hypothesis is not supported by the data, it can help to refine existing theories or prompt the development of new hypotheses to explain the phenomenon.

When to use Hypothesis

Here are some common situations in which hypotheses are used:

- In scientific research , hypotheses are used to guide the design of experiments and to help researchers make predictions about the outcomes of those experiments.

- In social science research , hypotheses are used to test theories about human behavior, social relationships, and other phenomena.

- I n business , hypotheses can be used to guide decisions about marketing, product development, and other areas. For example, a hypothesis might be that a new product will sell well in a particular market, and this hypothesis can be tested through market research.

Characteristics of Hypothesis

Here are some common characteristics of a hypothesis:

- Testable : A hypothesis must be able to be tested through observation or experimentation. This means that it must be possible to collect data that will either support or refute the hypothesis.

- Falsifiable : A hypothesis must be able to be proven false if it is not supported by the data. If a hypothesis cannot be falsified, then it is not a scientific hypothesis.

- Clear and concise : A hypothesis should be stated in a clear and concise manner so that it can be easily understood and tested.

- Based on existing knowledge : A hypothesis should be based on existing knowledge and research in the field. It should not be based on personal beliefs or opinions.

- Specific : A hypothesis should be specific in terms of the variables being tested and the predicted outcome. This will help to ensure that the research is focused and well-designed.

- Tentative: A hypothesis is a tentative statement or assumption that requires further testing and evidence to be confirmed or refuted. It is not a final conclusion or assertion.

- Relevant : A hypothesis should be relevant to the research question or problem being studied. It should address a gap in knowledge or provide a new perspective on the issue.

Advantages of Hypothesis

Hypotheses have several advantages in scientific research and experimentation:

- Guides research: A hypothesis provides a clear and specific direction for research. It helps to focus the research question, select appropriate methods and variables, and interpret the results.

- Predictive powe r: A hypothesis makes predictions about the outcome of research, which can be tested through experimentation. This allows researchers to evaluate the validity of the hypothesis and make new discoveries.

- Facilitates communication: A hypothesis provides a common language and framework for scientists to communicate with one another about their research. This helps to facilitate the exchange of ideas and promotes collaboration.

- Efficient use of resources: A hypothesis helps researchers to use their time, resources, and funding efficiently by directing them towards specific research questions and methods that are most likely to yield results.

- Provides a basis for further research: A hypothesis that is supported by data provides a basis for further research and exploration. It can lead to new hypotheses, theories, and discoveries.

- Increases objectivity: A hypothesis can help to increase objectivity in research by providing a clear and specific framework for testing and interpreting results. This can reduce bias and increase the reliability of research findings.

Limitations of Hypothesis

Some Limitations of the Hypothesis are as follows:

- Limited to observable phenomena: Hypotheses are limited to observable phenomena and cannot account for unobservable or intangible factors. This means that some research questions may not be amenable to hypothesis testing.

- May be inaccurate or incomplete: Hypotheses are based on existing knowledge and research, which may be incomplete or inaccurate. This can lead to flawed hypotheses and erroneous conclusions.

- May be biased: Hypotheses may be biased by the researcher’s own beliefs, values, or assumptions. This can lead to selective interpretation of data and a lack of objectivity in research.

- Cannot prove causation: A hypothesis can only show a correlation between variables, but it cannot prove causation. This requires further experimentation and analysis.

- Limited to specific contexts: Hypotheses are limited to specific contexts and may not be generalizable to other situations or populations. This means that results may not be applicable in other contexts or may require further testing.

- May be affected by chance : Hypotheses may be affected by chance or random variation, which can obscure or distort the true relationship between variables.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Great Hypothesis

Hypothesis Definition, Format, Examples, and Tips

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Verywell / Alex Dos Diaz

- The Scientific Method

Hypothesis Format

Falsifiability of a hypothesis.

- Operationalization

Hypothesis Types

Hypotheses examples.

- Collecting Data

A hypothesis is a tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. It is a preliminary answer to your question that helps guide the research process.

Consider a study designed to examine the relationship between sleep deprivation and test performance. The hypothesis might be: "This study is designed to assess the hypothesis that sleep-deprived people will perform worse on a test than individuals who are not sleep-deprived."

At a Glance

A hypothesis is crucial to scientific research because it offers a clear direction for what the researchers are looking to find. This allows them to design experiments to test their predictions and add to our scientific knowledge about the world. This article explores how a hypothesis is used in psychology research, how to write a good hypothesis, and the different types of hypotheses you might use.

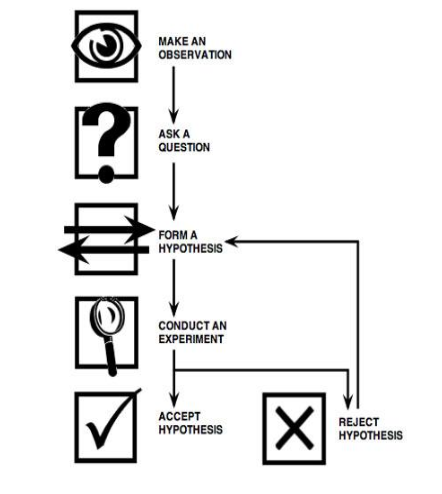

The Hypothesis in the Scientific Method

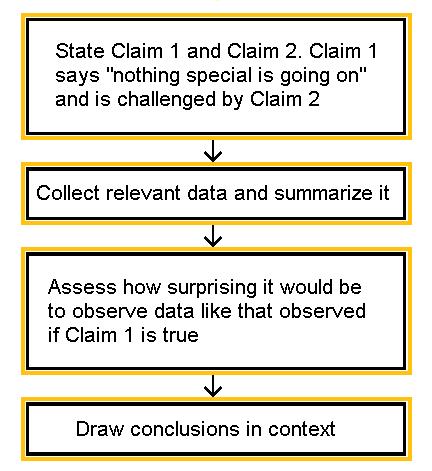

In the scientific method , whether it involves research in psychology, biology, or some other area, a hypothesis represents what the researchers think will happen in an experiment. The scientific method involves the following steps:

- Forming a question

- Performing background research

- Creating a hypothesis

- Designing an experiment

- Collecting data

- Analyzing the results

- Drawing conclusions

- Communicating the results

The hypothesis is a prediction, but it involves more than a guess. Most of the time, the hypothesis begins with a question which is then explored through background research. At this point, researchers then begin to develop a testable hypothesis.

Unless you are creating an exploratory study, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen.

In a study exploring the effects of a particular drug, the hypothesis might be that researchers expect the drug to have some type of effect on the symptoms of a specific illness. In psychology, the hypothesis might focus on how a certain aspect of the environment might influence a particular behavior.

Remember, a hypothesis does not have to be correct. While the hypothesis predicts what the researchers expect to see, the goal of the research is to determine whether this guess is right or wrong. When conducting an experiment, researchers might explore numerous factors to determine which ones might contribute to the ultimate outcome.

In many cases, researchers may find that the results of an experiment do not support the original hypothesis. When writing up these results, the researchers might suggest other options that should be explored in future studies.

In many cases, researchers might draw a hypothesis from a specific theory or build on previous research. For example, prior research has shown that stress can impact the immune system. So a researcher might hypothesize: "People with high-stress levels will be more likely to contract a common cold after being exposed to the virus than people who have low-stress levels."

In other instances, researchers might look at commonly held beliefs or folk wisdom. "Birds of a feather flock together" is one example of folk adage that a psychologist might try to investigate. The researcher might pose a specific hypothesis that "People tend to select romantic partners who are similar to them in interests and educational level."

Elements of a Good Hypothesis

So how do you write a good hypothesis? When trying to come up with a hypothesis for your research or experiments, ask yourself the following questions:

- Is your hypothesis based on your research on a topic?

- Can your hypothesis be tested?

- Does your hypothesis include independent and dependent variables?

Before you come up with a specific hypothesis, spend some time doing background research. Once you have completed a literature review, start thinking about potential questions you still have. Pay attention to the discussion section in the journal articles you read . Many authors will suggest questions that still need to be explored.

How to Formulate a Good Hypothesis

To form a hypothesis, you should take these steps:

- Collect as many observations about a topic or problem as you can.

- Evaluate these observations and look for possible causes of the problem.

- Create a list of possible explanations that you might want to explore.

- After you have developed some possible hypotheses, think of ways that you could confirm or disprove each hypothesis through experimentation. This is known as falsifiability.

In the scientific method , falsifiability is an important part of any valid hypothesis. In order to test a claim scientifically, it must be possible that the claim could be proven false.

Students sometimes confuse the idea of falsifiability with the idea that it means that something is false, which is not the case. What falsifiability means is that if something was false, then it is possible to demonstrate that it is false.

One of the hallmarks of pseudoscience is that it makes claims that cannot be refuted or proven false.

The Importance of Operational Definitions

A variable is a factor or element that can be changed and manipulated in ways that are observable and measurable. However, the researcher must also define how the variable will be manipulated and measured in the study.

Operational definitions are specific definitions for all relevant factors in a study. This process helps make vague or ambiguous concepts detailed and measurable.

For example, a researcher might operationally define the variable " test anxiety " as the results of a self-report measure of anxiety experienced during an exam. A "study habits" variable might be defined by the amount of studying that actually occurs as measured by time.

These precise descriptions are important because many things can be measured in various ways. Clearly defining these variables and how they are measured helps ensure that other researchers can replicate your results.

Replicability

One of the basic principles of any type of scientific research is that the results must be replicable.

Replication means repeating an experiment in the same way to produce the same results. By clearly detailing the specifics of how the variables were measured and manipulated, other researchers can better understand the results and repeat the study if needed.

Some variables are more difficult than others to define. For example, how would you operationally define a variable such as aggression ? For obvious ethical reasons, researchers cannot create a situation in which a person behaves aggressively toward others.

To measure this variable, the researcher must devise a measurement that assesses aggressive behavior without harming others. The researcher might utilize a simulated task to measure aggressiveness in this situation.

Hypothesis Checklist

- Does your hypothesis focus on something that you can actually test?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate the variables?

- Can your hypothesis be tested without violating ethical standards?

The hypothesis you use will depend on what you are investigating and hoping to find. Some of the main types of hypotheses that you might use include:

- Simple hypothesis : This type of hypothesis suggests there is a relationship between one independent variable and one dependent variable.

- Complex hypothesis : This type suggests a relationship between three or more variables, such as two independent and dependent variables.

- Null hypothesis : This hypothesis suggests no relationship exists between two or more variables.

- Alternative hypothesis : This hypothesis states the opposite of the null hypothesis.

- Statistical hypothesis : This hypothesis uses statistical analysis to evaluate a representative population sample and then generalizes the findings to the larger group.

- Logical hypothesis : This hypothesis assumes a relationship between variables without collecting data or evidence.

A hypothesis often follows a basic format of "If {this happens} then {this will happen}." One way to structure your hypothesis is to describe what will happen to the dependent variable if you change the independent variable .

The basic format might be: "If {these changes are made to a certain independent variable}, then we will observe {a change in a specific dependent variable}."

A few examples of simple hypotheses:

- "Students who eat breakfast will perform better on a math exam than students who do not eat breakfast."

- "Students who experience test anxiety before an English exam will get lower scores than students who do not experience test anxiety."

- "Motorists who talk on the phone while driving will be more likely to make errors on a driving course than those who do not talk on the phone."

- "Children who receive a new reading intervention will have higher reading scores than students who do not receive the intervention."

Examples of a complex hypothesis include:

- "People with high-sugar diets and sedentary activity levels are more likely to develop depression."

- "Younger people who are regularly exposed to green, outdoor areas have better subjective well-being than older adults who have limited exposure to green spaces."

Examples of a null hypothesis include:

- "There is no difference in anxiety levels between people who take St. John's wort supplements and those who do not."

- "There is no difference in scores on a memory recall task between children and adults."

- "There is no difference in aggression levels between children who play first-person shooter games and those who do not."

Examples of an alternative hypothesis:

- "People who take St. John's wort supplements will have less anxiety than those who do not."

- "Adults will perform better on a memory task than children."

- "Children who play first-person shooter games will show higher levels of aggression than children who do not."

Collecting Data on Your Hypothesis

Once a researcher has formed a testable hypothesis, the next step is to select a research design and start collecting data. The research method depends largely on exactly what they are studying. There are two basic types of research methods: descriptive research and experimental research.

Descriptive Research Methods

Descriptive research such as case studies , naturalistic observations , and surveys are often used when conducting an experiment is difficult or impossible. These methods are best used to describe different aspects of a behavior or psychological phenomenon.

Once a researcher has collected data using descriptive methods, a correlational study can examine how the variables are related. This research method might be used to investigate a hypothesis that is difficult to test experimentally.

Experimental Research Methods

Experimental methods are used to demonstrate causal relationships between variables. In an experiment, the researcher systematically manipulates a variable of interest (known as the independent variable) and measures the effect on another variable (known as the dependent variable).

Unlike correlational studies, which can only be used to determine if there is a relationship between two variables, experimental methods can be used to determine the actual nature of the relationship—whether changes in one variable actually cause another to change.

The hypothesis is a critical part of any scientific exploration. It represents what researchers expect to find in a study or experiment. In situations where the hypothesis is unsupported by the research, the research still has value. Such research helps us better understand how different aspects of the natural world relate to one another. It also helps us develop new hypotheses that can then be tested in the future.

Thompson WH, Skau S. On the scope of scientific hypotheses . R Soc Open Sci . 2023;10(8):230607. doi:10.1098/rsos.230607

Taran S, Adhikari NKJ, Fan E. Falsifiability in medicine: what clinicians can learn from Karl Popper [published correction appears in Intensive Care Med. 2021 Jun 17;:]. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47(9):1054-1056. doi:10.1007/s00134-021-06432-z

Eyler AA. Research Methods for Public Health . 1st ed. Springer Publishing Company; 2020. doi:10.1891/9780826182067.0004

Nosek BA, Errington TM. What is replication ? PLoS Biol . 2020;18(3):e3000691. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000691

Aggarwal R, Ranganathan P. Study designs: Part 2 - Descriptive studies . Perspect Clin Res . 2019;10(1):34-36. doi:10.4103/picr.PICR_154_18

Nevid J. Psychology: Concepts and Applications. Wadworth, 2013.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Shona McCombes .

A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested by scientific research. If you want to test a relationship between two or more variables, you need to write hypotheses before you start your experiment or data collection.

Table of contents

What is a hypothesis, developing a hypothesis (with example), hypothesis examples, frequently asked questions about writing hypotheses.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess – it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

Variables in hypotheses

Hypotheses propose a relationship between two or more variables . An independent variable is something the researcher changes or controls. A dependent variable is something the researcher observes and measures.

In this example, the independent variable is exposure to the sun – the assumed cause . The dependent variable is the level of happiness – the assumed effect .

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Step 1: ask a question.

Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project.

Step 2: Do some preliminary research

Your initial answer to the question should be based on what is already known about the topic. Look for theories and previous studies to help you form educated assumptions about what your research will find.

At this stage, you might construct a conceptual framework to identify which variables you will study and what you think the relationships are between them. Sometimes, you’ll have to operationalise more complex constructs.

Step 3: Formulate your hypothesis

Now you should have some idea of what you expect to find. Write your initial answer to the question in a clear, concise sentence.

Step 4: Refine your hypothesis

You need to make sure your hypothesis is specific and testable. There are various ways of phrasing a hypothesis, but all the terms you use should have clear definitions, and the hypothesis should contain:

- The relevant variables

- The specific group being studied

- The predicted outcome of the experiment or analysis

Step 5: Phrase your hypothesis in three ways

To identify the variables, you can write a simple prediction in if … then form. The first part of the sentence states the independent variable and the second part states the dependent variable.

In academic research, hypotheses are more commonly phrased in terms of correlations or effects, where you directly state the predicted relationship between variables.

If you are comparing two groups, the hypothesis can state what difference you expect to find between them.

Step 6. Write a null hypothesis

If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing , you will also have to write a null hypothesis. The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0 , while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a .

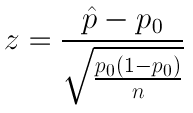

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

A hypothesis is not just a guess. It should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

A research hypothesis is your proposed answer to your research question. The research hypothesis usually includes an explanation (‘ x affects y because …’).

A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a mathematical statement about a population parameter. Statistical hypotheses always come in pairs: the null and alternative hypotheses. In a well-designed study , the statistical hypotheses correspond logically to the research hypothesis.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, May 06). How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 29 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/hypothesis-writing/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, operationalisation | a guide with examples, pros & cons, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples.

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

The Craft of Writing a Strong Hypothesis

Table of Contents

Writing a hypothesis is one of the essential elements of a scientific research paper. It needs to be to the point, clearly communicating what your research is trying to accomplish. A blurry, drawn-out, or complexly-structured hypothesis can confuse your readers. Or worse, the editor and peer reviewers.

A captivating hypothesis is not too intricate. This blog will take you through the process so that, by the end of it, you have a better idea of how to convey your research paper's intent in just one sentence.

What is a Hypothesis?

The first step in your scientific endeavor, a hypothesis, is a strong, concise statement that forms the basis of your research. It is not the same as a thesis statement , which is a brief summary of your research paper .

The sole purpose of a hypothesis is to predict your paper's findings, data, and conclusion. It comes from a place of curiosity and intuition . When you write a hypothesis, you're essentially making an educated guess based on scientific prejudices and evidence, which is further proven or disproven through the scientific method.

The reason for undertaking research is to observe a specific phenomenon. A hypothesis, therefore, lays out what the said phenomenon is. And it does so through two variables, an independent and dependent variable.

The independent variable is the cause behind the observation, while the dependent variable is the effect of the cause. A good example of this is “mixing red and blue forms purple.” In this hypothesis, mixing red and blue is the independent variable as you're combining the two colors at your own will. The formation of purple is the dependent variable as, in this case, it is conditional to the independent variable.

Different Types of Hypotheses

Types of hypotheses

Some would stand by the notion that there are only two types of hypotheses: a Null hypothesis and an Alternative hypothesis. While that may have some truth to it, it would be better to fully distinguish the most common forms as these terms come up so often, which might leave you out of context.

Apart from Null and Alternative, there are Complex, Simple, Directional, Non-Directional, Statistical, and Associative and casual hypotheses. They don't necessarily have to be exclusive, as one hypothesis can tick many boxes, but knowing the distinctions between them will make it easier for you to construct your own.

1. Null hypothesis

A null hypothesis proposes no relationship between two variables. Denoted by H 0 , it is a negative statement like “Attending physiotherapy sessions does not affect athletes' on-field performance.” Here, the author claims physiotherapy sessions have no effect on on-field performances. Even if there is, it's only a coincidence.

2. Alternative hypothesis

Considered to be the opposite of a null hypothesis, an alternative hypothesis is donated as H1 or Ha. It explicitly states that the dependent variable affects the independent variable. A good alternative hypothesis example is “Attending physiotherapy sessions improves athletes' on-field performance.” or “Water evaporates at 100 °C. ” The alternative hypothesis further branches into directional and non-directional.

- Directional hypothesis: A hypothesis that states the result would be either positive or negative is called directional hypothesis. It accompanies H1 with either the ‘<' or ‘>' sign.

- Non-directional hypothesis: A non-directional hypothesis only claims an effect on the dependent variable. It does not clarify whether the result would be positive or negative. The sign for a non-directional hypothesis is ‘≠.'

3. Simple hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a statement made to reflect the relation between exactly two variables. One independent and one dependent. Consider the example, “Smoking is a prominent cause of lung cancer." The dependent variable, lung cancer, is dependent on the independent variable, smoking.

4. Complex hypothesis

In contrast to a simple hypothesis, a complex hypothesis implies the relationship between multiple independent and dependent variables. For instance, “Individuals who eat more fruits tend to have higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.” The independent variable is eating more fruits, while the dependent variables are higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.

5. Associative and casual hypothesis

Associative and casual hypotheses don't exhibit how many variables there will be. They define the relationship between the variables. In an associative hypothesis, changing any one variable, dependent or independent, affects others. In a casual hypothesis, the independent variable directly affects the dependent.

6. Empirical hypothesis

Also referred to as the working hypothesis, an empirical hypothesis claims a theory's validation via experiments and observation. This way, the statement appears justifiable and different from a wild guess.

Say, the hypothesis is “Women who take iron tablets face a lesser risk of anemia than those who take vitamin B12.” This is an example of an empirical hypothesis where the researcher the statement after assessing a group of women who take iron tablets and charting the findings.

7. Statistical hypothesis

The point of a statistical hypothesis is to test an already existing hypothesis by studying a population sample. Hypothesis like “44% of the Indian population belong in the age group of 22-27.” leverage evidence to prove or disprove a particular statement.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

Writing a hypothesis is essential as it can make or break your research for you. That includes your chances of getting published in a journal. So when you're designing one, keep an eye out for these pointers:

- A research hypothesis has to be simple yet clear to look justifiable enough.

- It has to be testable — your research would be rendered pointless if too far-fetched into reality or limited by technology.

- It has to be precise about the results —what you are trying to do and achieve through it should come out in your hypothesis.

- A research hypothesis should be self-explanatory, leaving no doubt in the reader's mind.

- If you are developing a relational hypothesis, you need to include the variables and establish an appropriate relationship among them.

- A hypothesis must keep and reflect the scope for further investigations and experiments.

Separating a Hypothesis from a Prediction

Outside of academia, hypothesis and prediction are often used interchangeably. In research writing, this is not only confusing but also incorrect. And although a hypothesis and prediction are guesses at their core, there are many differences between them.

A hypothesis is an educated guess or even a testable prediction validated through research. It aims to analyze the gathered evidence and facts to define a relationship between variables and put forth a logical explanation behind the nature of events.

Predictions are assumptions or expected outcomes made without any backing evidence. They are more fictionally inclined regardless of where they originate from.

For this reason, a hypothesis holds much more weight than a prediction. It sticks to the scientific method rather than pure guesswork. "Planets revolve around the Sun." is an example of a hypothesis as it is previous knowledge and observed trends. Additionally, we can test it through the scientific method.

Whereas "COVID-19 will be eradicated by 2030." is a prediction. Even though it results from past trends, we can't prove or disprove it. So, the only way this gets validated is to wait and watch if COVID-19 cases end by 2030.

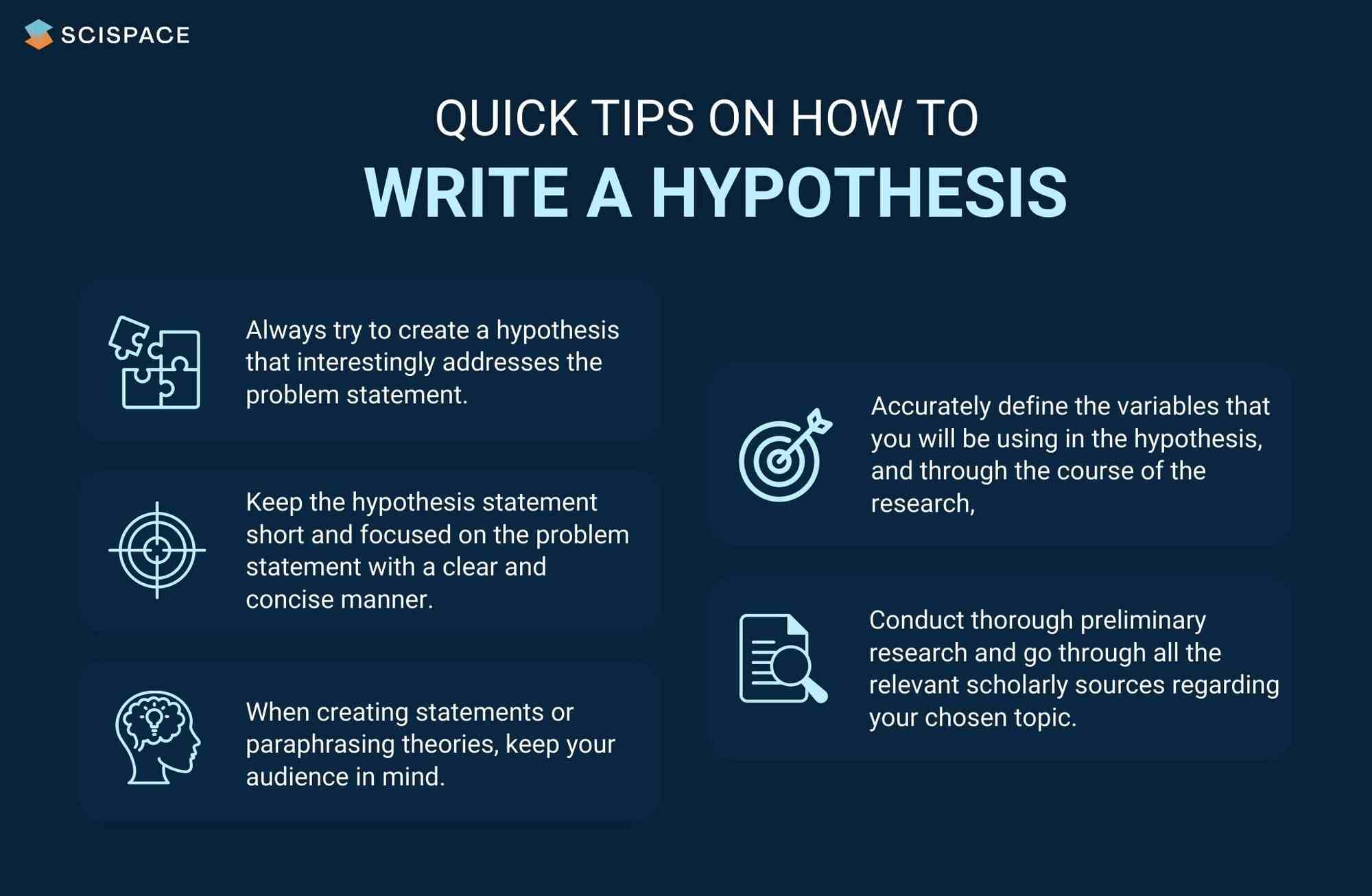

Finally, How to Write a Hypothesis

Quick tips on writing a hypothesis

1. Be clear about your research question

A hypothesis should instantly address the research question or the problem statement. To do so, you need to ask a question. Understand the constraints of your undertaken research topic and then formulate a simple and topic-centric problem. Only after that can you develop a hypothesis and further test for evidence.

2. Carry out a recce

Once you have your research's foundation laid out, it would be best to conduct preliminary research. Go through previous theories, academic papers, data, and experiments before you start curating your research hypothesis. It will give you an idea of your hypothesis's viability or originality.

Making use of references from relevant research papers helps draft a good research hypothesis. SciSpace Discover offers a repository of over 270 million research papers to browse through and gain a deeper understanding of related studies on a particular topic. Additionally, you can use SciSpace Copilot , your AI research assistant, for reading any lengthy research paper and getting a more summarized context of it. A hypothesis can be formed after evaluating many such summarized research papers. Copilot also offers explanations for theories and equations, explains paper in simplified version, allows you to highlight any text in the paper or clip math equations and tables and provides a deeper, clear understanding of what is being said. This can improve the hypothesis by helping you identify potential research gaps.

3. Create a 3-dimensional hypothesis

Variables are an essential part of any reasonable hypothesis. So, identify your independent and dependent variable(s) and form a correlation between them. The ideal way to do this is to write the hypothetical assumption in the ‘if-then' form. If you use this form, make sure that you state the predefined relationship between the variables.

In another way, you can choose to present your hypothesis as a comparison between two variables. Here, you must specify the difference you expect to observe in the results.

4. Write the first draft

Now that everything is in place, it's time to write your hypothesis. For starters, create the first draft. In this version, write what you expect to find from your research.

Clearly separate your independent and dependent variables and the link between them. Don't fixate on syntax at this stage. The goal is to ensure your hypothesis addresses the issue.

5. Proof your hypothesis

After preparing the first draft of your hypothesis, you need to inspect it thoroughly. It should tick all the boxes, like being concise, straightforward, relevant, and accurate. Your final hypothesis has to be well-structured as well.

Research projects are an exciting and crucial part of being a scholar. And once you have your research question, you need a great hypothesis to begin conducting research. Thus, knowing how to write a hypothesis is very important.

Now that you have a firmer grasp on what a good hypothesis constitutes, the different kinds there are, and what process to follow, you will find it much easier to write your hypothesis, which ultimately helps your research.

Now it's easier than ever to streamline your research workflow with SciSpace Discover . Its integrated, comprehensive end-to-end platform for research allows scholars to easily discover, write and publish their research and fosters collaboration.

It includes everything you need, including a repository of over 270 million research papers across disciplines, SEO-optimized summaries and public profiles to show your expertise and experience.

If you found these tips on writing a research hypothesis useful, head over to our blog on Statistical Hypothesis Testing to learn about the top researchers, papers, and institutions in this domain.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. what is the definition of hypothesis.

According to the Oxford dictionary, a hypothesis is defined as “An idea or explanation of something that is based on a few known facts, but that has not yet been proved to be true or correct”.

2. What is an example of hypothesis?

The hypothesis is a statement that proposes a relationship between two or more variables. An example: "If we increase the number of new users who join our platform by 25%, then we will see an increase in revenue."

3. What is an example of null hypothesis?

A null hypothesis is a statement that there is no relationship between two variables. The null hypothesis is written as H0. The null hypothesis states that there is no effect. For example, if you're studying whether or not a particular type of exercise increases strength, your null hypothesis will be "there is no difference in strength between people who exercise and people who don't."

4. What are the types of research?

• Fundamental research

• Applied research

• Qualitative research

• Quantitative research

• Mixed research

• Exploratory research

• Longitudinal research

• Cross-sectional research

• Field research

• Laboratory research

• Fixed research

• Flexible research

• Action research

• Policy research

• Classification research

• Comparative research

• Causal research

• Inductive research

• Deductive research

5. How to write a hypothesis?

• Your hypothesis should be able to predict the relationship and outcome.

• Avoid wordiness by keeping it simple and brief.

• Your hypothesis should contain observable and testable outcomes.

• Your hypothesis should be relevant to the research question.

6. What are the 2 types of hypothesis?

• Null hypotheses are used to test the claim that "there is no difference between two groups of data".

• Alternative hypotheses test the claim that "there is a difference between two data groups".

7. Difference between research question and research hypothesis?

A research question is a broad, open-ended question you will try to answer through your research. A hypothesis is a statement based on prior research or theory that you expect to be true due to your study. Example - Research question: What are the factors that influence the adoption of the new technology? Research hypothesis: There is a positive relationship between age, education and income level with the adoption of the new technology.

8. What is plural for hypothesis?

The plural of hypothesis is hypotheses. Here's an example of how it would be used in a statement, "Numerous well-considered hypotheses are presented in this part, and they are supported by tables and figures that are well-illustrated."

9. What is the red queen hypothesis?

The red queen hypothesis in evolutionary biology states that species must constantly evolve to avoid extinction because if they don't, they will be outcompeted by other species that are evolving. Leigh Van Valen first proposed it in 1973; since then, it has been tested and substantiated many times.

10. Who is known as the father of null hypothesis?

The father of the null hypothesis is Sir Ronald Fisher. He published a paper in 1925 that introduced the concept of null hypothesis testing, and he was also the first to use the term itself.

11. When to reject null hypothesis?

You need to find a significant difference between your two populations to reject the null hypothesis. You can determine that by running statistical tests such as an independent sample t-test or a dependent sample t-test. You should reject the null hypothesis if the p-value is less than 0.05.

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

How to Write a Hypothesis? Types and Examples

All research studies involve the use of the scientific method, which is a mathematical and experimental technique used to conduct experiments by developing and testing a hypothesis or a prediction about an outcome. Simply put, a hypothesis is a suggested solution to a problem. It includes elements that are expressed in terms of relationships with each other to explain a condition or an assumption that hasn’t been verified using facts. 1 The typical steps in a scientific method include developing such a hypothesis, testing it through various methods, and then modifying it based on the outcomes of the experiments.

A research hypothesis can be defined as a specific, testable prediction about the anticipated results of a study. 2 Hypotheses help guide the research process and supplement the aim of the study. After several rounds of testing, hypotheses can help develop scientific theories. 3 Hypotheses are often written as if-then statements.

Here are two hypothesis examples:

Dandelions growing in nitrogen-rich soils for two weeks develop larger leaves than those in nitrogen-poor soils because nitrogen stimulates vegetative growth. 4

If a company offers flexible work hours, then their employees will be happier at work. 5

Table of Contents

- What is a hypothesis?

- Types of hypotheses

- Characteristics of a hypothesis

- Functions of a hypothesis

- How to write a hypothesis

- Hypothesis examples

- Frequently asked questions

What is a hypothesis?

A hypothesis expresses an expected relationship between variables in a study and is developed before conducting any research. Hypotheses are not opinions but rather are expected relationships based on facts and observations. They help support scientific research and expand existing knowledge. An incorrectly formulated hypothesis can affect the entire experiment leading to errors in the results so it’s important to know how to formulate a hypothesis and develop it carefully.

A few sources of a hypothesis include observations from prior studies, current research and experiences, competitors, scientific theories, and general conditions that can influence people. Figure 1 depicts the different steps in a research design and shows where exactly in the process a hypothesis is developed. 4

There are seven different types of hypotheses—simple, complex, directional, nondirectional, associative and causal, null, and alternative.

Types of hypotheses

The seven types of hypotheses are listed below: 5 , 6,7

- Simple : Predicts the relationship between a single dependent variable and a single independent variable.

Example: Exercising in the morning every day will increase your productivity.

- Complex : Predicts the relationship between two or more variables.

Example: Spending three hours or more on social media daily will negatively affect children’s mental health and productivity, more than that of adults.

- Directional : Specifies the expected direction to be followed and uses terms like increase, decrease, positive, negative, more, or less.

Example: The inclusion of intervention X decreases infant mortality compared to the original treatment.

- Non-directional : Does not predict the exact direction, nature, or magnitude of the relationship between two variables but rather states the existence of a relationship. This hypothesis may be used when there is no underlying theory or if findings contradict prior research.

Example: Cats and dogs differ in the amount of affection they express.

- Associative and causal : An associative hypothesis suggests an interdependency between variables, that is, how a change in one variable changes the other.

Example: There is a positive association between physical activity levels and overall health.

A causal hypothesis, on the other hand, expresses a cause-and-effect association between variables.

Example: Long-term alcohol use causes liver damage.

- Null : Claims that the original hypothesis is false by showing that there is no relationship between the variables.

Example: Sleep duration does not have any effect on productivity.

- Alternative : States the opposite of the null hypothesis, that is, a relationship exists between two variables.

Example: Sleep duration affects productivity.

Characteristics of a hypothesis

So, what makes a good hypothesis? Here are some important characteristics of a hypothesis. 8,9

- Testable : You must be able to test the hypothesis using scientific methods to either accept or reject the prediction.

- Falsifiable : It should be possible to collect data that reject rather than support the hypothesis.

- Logical : Hypotheses shouldn’t be a random guess but rather should be based on previous theories, observations, prior research, and logical reasoning.

- Positive : The hypothesis statement about the existence of an association should be positive, that is, it should not suggest that an association does not exist. Therefore, the language used and knowing how to phrase a hypothesis is very important.

- Clear and accurate : The language used should be easily comprehensible and use correct terminology.

- Relevant : The hypothesis should be relevant and specific to the research question.

- Structure : Should include all the elements that make a good hypothesis: variables, relationship, and outcome.

Functions of a hypothesis

The following list mentions some important functions of a hypothesis: 1

- Maintains the direction and progress of the research.

- Expresses the important assumptions underlying the proposition in a single statement.

- Establishes a suitable context for researchers to begin their investigation and for readers who are referring to the final report.

- Provides an explanation for the occurrence of a specific phenomenon.

- Ensures selection of appropriate and accurate facts necessary and relevant to the research subject.

To summarize, a hypothesis provides the conceptual elements that complete the known data, conceptual relationships that systematize unordered elements, and conceptual meanings and interpretations that explain the unknown phenomena. 1

How to write a hypothesis

Listed below are the main steps explaining how to write a hypothesis. 2,4,5

- Make an observation and identify variables : Observe the subject in question and try to recognize a pattern or a relationship between the variables involved. This step provides essential background information to begin your research.

For example, if you notice that an office’s vending machine frequently runs out of a specific snack, you may predict that more people in the office choose that snack over another.

- Identify the main research question : After identifying a subject and recognizing a pattern, the next step is to ask a question that your hypothesis will answer.

For example, after observing employees’ break times at work, you could ask “why do more employees take breaks in the morning rather than in the afternoon?”

- Conduct some preliminary research to ensure originality and novelty : Your initial answer, which is your hypothesis, to the question is based on some pre-existing information about the subject. However, to ensure that your hypothesis has not been asked before or that it has been asked but rejected by other researchers you would need to gather additional information.

For example, based on your observations you might state a hypothesis that employees work more efficiently when the air conditioning in the office is set at a lower temperature. However, during your preliminary research you find that this hypothesis was proven incorrect by a prior study.

- Develop a general statement : After your preliminary research has confirmed the originality of your proposed answer, draft a general statement that includes all variables, subjects, and predicted outcome. The statement could be if/then or declarative.

- Finalize the hypothesis statement : Use the PICOT model, which clarifies how to word a hypothesis effectively, when finalizing the statement. This model lists the important components required to write a hypothesis.

P opulation: The specific group or individual who is the main subject of the research

I nterest: The main concern of the study/research question

C omparison: The main alternative group

O utcome: The expected results

T ime: Duration of the experiment

Once you’ve finalized your hypothesis statement you would need to conduct experiments to test whether the hypothesis is true or false.

Hypothesis examples

The following table provides examples of different types of hypotheses. 10 ,11

Key takeaways

Here’s a summary of all the key points discussed in this article about how to write a hypothesis.

- A hypothesis is an assumption about an association between variables made based on limited evidence, which should be tested.

- A hypothesis has four parts—the research question, independent variable, dependent variable, and the proposed relationship between the variables.

- The statement should be clear, concise, testable, logical, and falsifiable.

- There are seven types of hypotheses—simple, complex, directional, non-directional, associative and causal, null, and alternative.

- A hypothesis provides a focus and direction for the research to progress.

- A hypothesis plays an important role in the scientific method by helping to create an appropriate experimental design.

Frequently asked questions

Hypotheses and research questions have different objectives and structure. The following table lists some major differences between the two. 9

Here are a few examples to differentiate between a research question and hypothesis.

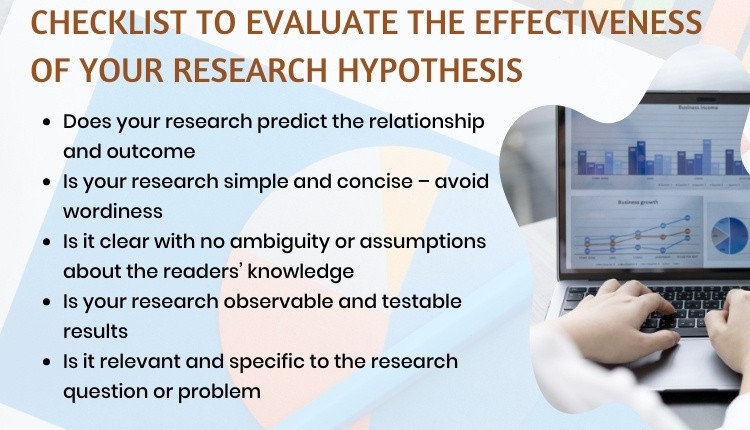

Yes, here’s a simple checklist to help you gauge the effectiveness of your hypothesis. 9 1. When writing a hypothesis statement, check if it: 2. Predicts the relationship between the stated variables and the expected outcome. 3. Uses simple and concise language and is not wordy. 4. Does not assume readers’ knowledge about the subject. 5. Has observable, falsifiable, and testable results.

As mentioned earlier in this article, a hypothesis is an assumption or prediction about an association between variables based on observations and simple evidence. These statements are usually generic. Research objectives, on the other hand, are more specific and dictated by hypotheses. The same hypothesis can be tested using different methods and the research objectives could be different in each case. For example, Louis Pasteur observed that food lasts longer at higher altitudes, reasoned that it could be because the air at higher altitudes is cleaner (with fewer or no germs), and tested the hypothesis by exposing food to air cleaned in the laboratory. 12 Thus, a hypothesis is predictive—if the reasoning is correct, X will lead to Y—and research objectives are developed to test these predictions.

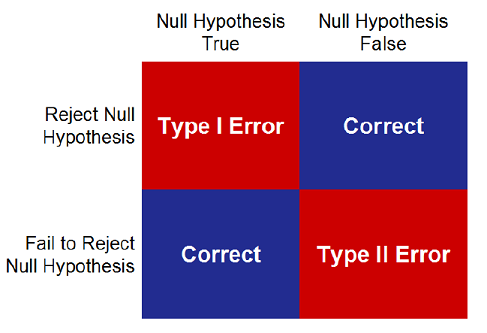

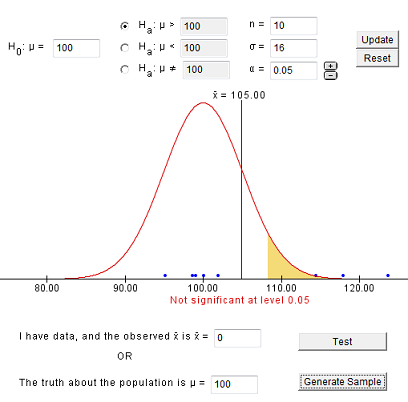

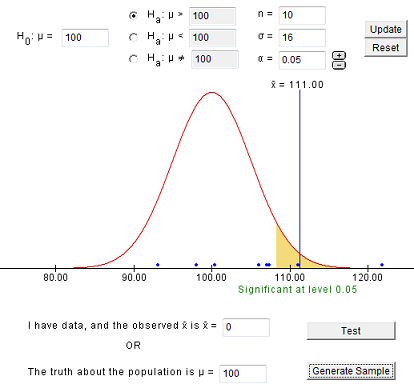

Null hypothesis testing is a method to decide between two assumptions or predictions between variables (null and alternative hypotheses) in a statistical relationship in a sample. The null hypothesis, denoted as H 0 , claims that no relationship exists between variables in a population and any relationship in the sample reflects a sampling error or occurrence by chance. The alternative hypothesis, denoted as H 1 , claims that there is a relationship in the population. In every study, researchers need to decide whether the relationship in a sample occurred by chance or reflects a relationship in the population. This is done by hypothesis testing using the following steps: 13 1. Assume that the null hypothesis is true. 2. Determine how likely the sample relationship would be if the null hypothesis were true. This probability is called the p value. 3. If the sample relationship would be extremely unlikely, reject the null hypothesis and accept the alternative hypothesis. If the relationship would not be unlikely, accept the null hypothesis.

To summarize, researchers should know how to write a good hypothesis to ensure that their research progresses in the required direction. A hypothesis is a testable prediction about any behavior or relationship between variables, usually based on facts and observation, and states an expected outcome.

We hope this article has provided you with essential insight into the different types of hypotheses and their functions so that you can use them appropriately in your next research project.

References

- Dalen, DVV. The function of hypotheses in research. Proquest website. Accessed April 8, 2024. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1437933010?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true&sourcetype=Scholarly%20Journals&imgSeq=1

- McLeod S. Research hypothesis in psychology: Types & examples. SimplyPsychology website. Updated December 13, 2023. Accessed April 9, 2024. https://www.simplypsychology.org/what-is-a-hypotheses.html

- Scientific method. Britannica website. Updated March 14, 2024. Accessed April 9, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/science/scientific-method

- The hypothesis in science writing. Accessed April 10, 2024. https://berks.psu.edu/sites/berks/files/campus/HypothesisHandout_Final.pdf

- How to develop a hypothesis (with elements, types, and examples). Indeed.com website. Updated February 3, 2023. Accessed April 10, 2024. https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/career-development/how-to-write-a-hypothesis

- Types of research hypotheses. Excelsior online writing lab. Accessed April 11, 2024. https://owl.excelsior.edu/research/research-hypotheses/types-of-research-hypotheses/

- What is a research hypothesis: how to write it, types, and examples. Researcher.life website. Published February 8, 2023. Accessed April 11, 2024. https://researcher.life/blog/article/how-to-write-a-research-hypothesis-definition-types-examples/

- Developing a hypothesis. Pressbooks website. Accessed April 12, 2024. https://opentext.wsu.edu/carriecuttler/chapter/developing-a-hypothesis/

- What is and how to write a good hypothesis in research. Elsevier author services website. Accessed April 12, 2024. https://scientific-publishing.webshop.elsevier.com/manuscript-preparation/what-how-write-good-hypothesis-research/

- How to write a great hypothesis. Verywellmind website. Updated March 12, 2023. Accessed April 13, 2024. https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-a-hypothesis-2795239

- 15 Hypothesis examples. Helpfulprofessor.com Published September 8, 2023. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://helpfulprofessor.com/hypothesis-examples/

- Editage insights. What is the interconnectivity between research objectives and hypothesis? Published February 24, 2021. Accessed April 13, 2024. https://www.editage.com/insights/what-is-the-interconnectivity-between-research-objectives-and-hypothesis

- Understanding null hypothesis testing. BCCampus open publishing. Accessed April 16, 2024. https://opentextbc.ca/researchmethods/chapter/understanding-null-hypothesis-testing/#:~:text=In%20null%20hypothesis%20testing%2C%20this,said%20to%20be%20statistically%20significant

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

- How to Write a Scientific Paper in 10 Steps

- What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

- What are Journal Guidelines on Using Generative AI Tools

Measuring Academic Success: Definition & Strategies for Excellence

What are scholarly sources and where can you find them , you may also like, 4 ways paperpal encourages responsible writing with ai, what are scholarly sources and where can you..., what is academic writing: tips for students, why traditional editorial process needs an upgrade, paperpal’s new ai research finder empowers authors to..., what is hedging in academic writing , how to use ai to enhance your college..., ai + human expertise – a paradigm shift..., how to use paperpal to generate emails &....

What Is A Research (Scientific) Hypothesis? A plain-language explainer + examples

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020

If you’re new to the world of research, or it’s your first time writing a dissertation or thesis, you’re probably noticing that the words “research hypothesis” and “scientific hypothesis” are used quite a bit, and you’re wondering what they mean in a research context .

“Hypothesis” is one of those words that people use loosely, thinking they understand what it means. However, it has a very specific meaning within academic research. So, it’s important to understand the exact meaning before you start hypothesizing.

Research Hypothesis 101

- What is a hypothesis ?

- What is a research hypothesis (scientific hypothesis)?

- Requirements for a research hypothesis

- Definition of a research hypothesis

- The null hypothesis

What is a hypothesis?

Let’s start with the general definition of a hypothesis (not a research hypothesis or scientific hypothesis), according to the Cambridge Dictionary:

Hypothesis: an idea or explanation for something that is based on known facts but has not yet been proved.

In other words, it’s a statement that provides an explanation for why or how something works, based on facts (or some reasonable assumptions), but that has not yet been specifically tested . For example, a hypothesis might look something like this:

Hypothesis: sleep impacts academic performance.

This statement predicts that academic performance will be influenced by the amount and/or quality of sleep a student engages in – sounds reasonable, right? It’s based on reasonable assumptions , underpinned by what we currently know about sleep and health (from the existing literature). So, loosely speaking, we could call it a hypothesis, at least by the dictionary definition.

But that’s not good enough…

Unfortunately, that’s not quite sophisticated enough to describe a research hypothesis (also sometimes called a scientific hypothesis), and it wouldn’t be acceptable in a dissertation, thesis or research paper . In the world of academic research, a statement needs a few more criteria to constitute a true research hypothesis .

What is a research hypothesis?

A research hypothesis (also called a scientific hypothesis) is a statement about the expected outcome of a study (for example, a dissertation or thesis). To constitute a quality hypothesis, the statement needs to have three attributes – specificity , clarity and testability .

Let’s take a look at these more closely.

Need a helping hand?

Hypothesis Essential #1: Specificity & Clarity

A good research hypothesis needs to be extremely clear and articulate about both what’ s being assessed (who or what variables are involved ) and the expected outcome (for example, a difference between groups, a relationship between variables, etc.).

Let’s stick with our sleepy students example and look at how this statement could be more specific and clear.

Hypothesis: Students who sleep at least 8 hours per night will, on average, achieve higher grades in standardised tests than students who sleep less than 8 hours a night.

As you can see, the statement is very specific as it identifies the variables involved (sleep hours and test grades), the parties involved (two groups of students), as well as the predicted relationship type (a positive relationship). There’s no ambiguity or uncertainty about who or what is involved in the statement, and the expected outcome is clear.

Contrast that to the original hypothesis we looked at – “Sleep impacts academic performance” – and you can see the difference. “Sleep” and “academic performance” are both comparatively vague , and there’s no indication of what the expected relationship direction is (more sleep or less sleep). As you can see, specificity and clarity are key.

Hypothesis Essential #2: Testability (Provability)

A statement must be testable to qualify as a research hypothesis. In other words, there needs to be a way to prove (or disprove) the statement. If it’s not testable, it’s not a hypothesis – simple as that.

For example, consider the hypothesis we mentioned earlier:

Hypothesis: Students who sleep at least 8 hours per night will, on average, achieve higher grades in standardised tests than students who sleep less than 8 hours a night.

We could test this statement by undertaking a quantitative study involving two groups of students, one that gets 8 or more hours of sleep per night for a fixed period, and one that gets less. We could then compare the standardised test results for both groups to see if there’s a statistically significant difference.

Again, if you compare this to the original hypothesis we looked at – “Sleep impacts academic performance” – you can see that it would be quite difficult to test that statement, primarily because it isn’t specific enough. How much sleep? By who? What type of academic performance?

So, remember the mantra – if you can’t test it, it’s not a hypothesis 🙂

Defining A Research Hypothesis

You’re still with us? Great! Let’s recap and pin down a clear definition of a hypothesis.

A research hypothesis (or scientific hypothesis) is a statement about an expected relationship between variables, or explanation of an occurrence, that is clear, specific and testable.

So, when you write up hypotheses for your dissertation or thesis, make sure that they meet all these criteria. If you do, you’ll not only have rock-solid hypotheses but you’ll also ensure a clear focus for your entire research project.

What about the null hypothesis?

You may have also heard the terms null hypothesis , alternative hypothesis, or H-zero thrown around. At a simple level, the null hypothesis is the counter-proposal to the original hypothesis.

For example, if the hypothesis predicts that there is a relationship between two variables (for example, sleep and academic performance), the null hypothesis would predict that there is no relationship between those variables.

At a more technical level, the null hypothesis proposes that no statistical significance exists in a set of given observations and that any differences are due to chance alone.

And there you have it – hypotheses in a nutshell.

If you have any questions, be sure to leave a comment below and we’ll do our best to help you. If you need hands-on help developing and testing your hypotheses, consider our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the research journey.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

16 Comments

Very useful information. I benefit more from getting more information in this regard.

Very great insight,educative and informative. Please give meet deep critics on many research data of public international Law like human rights, environment, natural resources, law of the sea etc

In a book I read a distinction is made between null, research, and alternative hypothesis. As far as I understand, alternative and research hypotheses are the same. Can you please elaborate? Best Afshin

This is a self explanatory, easy going site. I will recommend this to my friends and colleagues.

Very good definition. How can I cite your definition in my thesis? Thank you. Is nul hypothesis compulsory in a research?

It’s a counter-proposal to be proven as a rejection

Please what is the difference between alternate hypothesis and research hypothesis?

It is a very good explanation. However, it limits hypotheses to statistically tasteable ideas. What about for qualitative researches or other researches that involve quantitative data that don’t need statistical tests?

In qualitative research, one typically uses propositions, not hypotheses.

could you please elaborate it more

I’ve benefited greatly from these notes, thank you.

This is very helpful

well articulated ideas are presented here, thank you for being reliable sources of information

Excellent. Thanks for being clear and sound about the research methodology and hypothesis (quantitative research)

I have only a simple question regarding the null hypothesis. – Is the null hypothesis (Ho) known as the reversible hypothesis of the alternative hypothesis (H1? – How to test it in academic research?

this is very important note help me much more

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- What Is Research Methodology? Simple Definition (With Examples) - Grad Coach - […] Contrasted to this, a quantitative methodology is typically used when the research aims and objectives are confirmatory in nature. For example,…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, what is a hypothesis and how do i write one.

General Education

Think about something strange and unexplainable in your life. Maybe you get a headache right before it rains, or maybe you think your favorite sports team wins when you wear a certain color. If you wanted to see whether these are just coincidences or scientific fact, you would form a hypothesis, then create an experiment to see whether that hypothesis is true or not.

But what is a hypothesis, anyway? If you’re not sure about what a hypothesis is--or how to test for one!--you’re in the right place. This article will teach you everything you need to know about hypotheses, including:

- Defining the term “hypothesis”

- Providing hypothesis examples

- Giving you tips for how to write your own hypothesis

So let’s get started!

What Is a Hypothesis?

Merriam Webster defines a hypothesis as “an assumption or concession made for the sake of argument.” In other words, a hypothesis is an educated guess . Scientists make a reasonable assumption--or a hypothesis--then design an experiment to test whether it’s true or not. Keep in mind that in science, a hypothesis should be testable. You have to be able to design an experiment that tests your hypothesis in order for it to be valid.

As you could assume from that statement, it’s easy to make a bad hypothesis. But when you’re holding an experiment, it’s even more important that your guesses be good...after all, you’re spending time (and maybe money!) to figure out more about your observation. That’s why we refer to a hypothesis as an educated guess--good hypotheses are based on existing data and research to make them as sound as possible.