Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

- MEDICAL ASSISSTANT

- Abdominal Key

- Anesthesia Key

- Basicmedical Key

- Otolaryngology & Ophthalmology

- Musculoskeletal Key

- Obstetric, Gynecology and Pediatric

- Oncology & Hematology

- Plastic Surgery & Dermatology

- Clinical Dentistry

- Radiology Key

- Thoracic Key

- Veterinary Medicine

- Gold Membership

Case study of a patient living with diabetes mellitus

16 Case study of a patient living with diabetes mellitus Anne Claydon Chapter aims • To provide you with a case study of a patient who is living with diabetes together with the rationale for care • To encourage you to research and deepen your knowledge of diabetes Introduction This chapter provides you with an example of the nursing care that a patient with type 1 diabetes might require. The case study has been written by a diabetes nurse specialist and provides you with a patient profile to enable you to understand the context of the patient. The case study aims to guide you through the assessment, nursing action and evaluation of a patient with type 1 diabetes together with the rationale for care. Being in this community of practice has also enlightened me about diabetes as we come across many patients with diabetes. I have since learnt different ways of diabetes management. I can also give advice to patients suffering from diabetes bearing in mind that this is evidence based. (Patricia Moyo, third-year student nurse) Activity Chapter 1 gives a brief definition of diabetes and asks you to revise the normal anatomy and physiology of the endocrine system (see Montague et al 2005 ). How can diabetes affect the body and what happens within the body when a person’s blood sugars become unstable? The following paper outlines the latest guidelines for the care of patients with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). It would be useful to read these guidelines before you read the case study: Joint British Diabetes Societies Inpatient Care Group (2010) . The management of diabetic ketoacidosis in adults. NHS Diabetes, London. Online. Available at: http://www.bsped.org.uk/professional/guidelines/docs/DKAManagementOfDKAinAdultsMarch20101.pdf (accessed July 2011) Patient profile Lucy is an 18-year-old university student in her first year and is living in student accommodation. Lucy has had type 1 diabetes since the age of 13. Her parents are very supportive but naturally worried about her leaving home. Lucy had a take-away chicken meal 2 days ago and since then she has been vomiting and has diarrhoea. She stopped taking her insulin as she is not eating. She has been admitted with DKA. Assessment on admission Lucy is apyrexial and has not vomited for 6 hours. Her vital signs are: pulse 96 beats per minute, blood pressure 130/80 mmHg, respiratory rate slightly raised at 18 per minute. Due to her diarrhoea and vomiting, she is dehydrated. Ketones are + 2 on a standard urine stick, her blood glucose is 16 mmol/L and her venous pH is 7.2. Activity See Appendix 4 in Holland et al (2008) for possible questions to consider during the assessment stage of care planning. Lucy’s problems Based on your assessment of Lucy, the following problems should form the basis of your care plan: • Due to DKA, Lucy is dehydrated and has electrolyte imbalance. • Lucy lacks knowledge about the precipitating factors of DKA and how to prevent it. Lucy’s nursing care plan – acute stage (first hour) The most important therapeutic intervention for DKA in the acute stage is appropriate fluid replacement followed by insulin administration. Problem: Due to DKA, Lucy is dehydrated and has electrolyte imbalance. Goal: Lucy will maintain urine output > 30 mL hour. Lucy will have elastic skin turgor and moist, pink mucous membranes. Nursing action Rationale Measure and record urine output hourly Report urine output < 30 mL for 2 consecutive hours Catheterise Lucy Provide catheter care Lucy may undergo osmotic diuresis and have excessive urine output Measure fluid output accurately Maintain catheter hygiene at all time to prevent infection Administer intravenous therapy as prescribed and ensure that a cannula care plan is in place for this To prevent infection/complications around the cannula site Assess Lucy for signs of dehydration Assess Lucy’s skin turgor, mucous membranes and complaints of thirst Testing the skin; dry membranes and thirst are all signs of dehydration Continuous measurement of Lucy’s vital signs during this acute stage of DKA As Lucy has DKA and is dehydrated, compensatory mechanisms take place that may result in peripheral vasoconstriction which is characterised b a weak thready pulse, hypotension and Lucy may look pale Monitor Lucy’s neurological state Observe and document how awake Lucy is Assess how alert and orientated Lucy is to time and place Mental status in DKA can be altered due to severe volume depletion and electrolyte imbalance Monitor Lucy’s blood glucose levels every 15 minutes, then hourly as long as the insulin infusion continues Remember to wash Lucy’s hands to remove any contaminants that might alter the results Glucose levels need to be reduced gradually to prevent the risk of cerebral oedema Intravenous insulin therapy needs to continue until ketoacidosis is resolved Assess Lucy for signs of hypokalaemia, for example muscle weakness, shallow respirations, cramping and confusion DKA can cause excretion of potassium Insulin therapy results in intracellular movement of potassium resulting in low potassium levels Lucy may have signs of hyperkalaemia Assess Lucy for any weakness or irritability, ECG changes such as tall, peaked T waves, QRS and prolonged PR intervals may suggest this Potassium levels should be kept between 4 and 5 mmol/L As ketoacidosis resolves, potassium levels can rise quickly causing hyperkalaemia Ensure that the ECG leads are connected correctly and that the pads are not causing discomfort to Lucy’s skin Assess Lucy for signs of metabolic acidosis Lucy may show signs of being drowsy, she may have Kausmaul respirations, confusion and her breath may smell of pear drops Lucy may have metabolic acidosis due to a build up of ketones in her blood Measure Lucy’s serum ketone levels using a hand-held ketones meter Check ketones 4 hourly Blood glucose should be checked by a hand-held ketones meter This provides direct results for DKA to be resolved Ketonaemia has to be suppressed Lucy will need intravenous insulin during the acute stage Lucy will require fixed-rate intravenous infusion of insulin calculated on 0.1 units/kg The fixed rate of insulin may have to be adjusted in insulin resistance if the ketone concentration does not fall fast enough Aim for a reduction of blood ketone concentration by 0.5 mmol/L/hour Insulin has the following effects: • Reduction of blood glucose

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Related posts:

- Medical placements

- Revision and future learning

- The end of the journey

- Medicines management

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Comments are closed for this page.

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Elizabeth Nash, Yesenia Nunez and Casey Salinas

Molly is a 22 y.o. female performing arts student at CSUCI with an emphasis in theater. At 16 y.o., she was diagnosed with type 1 DM. Her pharmacological regimen consist 2 different types of insulin, which include glargine (long acting, basal) and humalog (rapid acting, meal coverage). Molly is an aspiring actress and struggles with her body image. She noticed weight gain ever since she started taking insulin. She discovered that by skipping her insulin she is able to “lose weight” and is able to maintain her image of an “industry standard body.” Molly’s roommate found her in a decompensated state in their dorm and called 911.

Upon field assessment, Molly was confused and diaphoretic. She was oriented X 2 (person, place). Pupils were equal, round, reactive to light and accommodated. She was tachycardic and has +1 peripheral pulses. Molly had Kussmaul respirations with a RR of 34 b/min with an abdominal pain level of 7/10. Her blood sugar was 850 mg/dL. Field Vitals: BP: bolus started, and NC at 2L/min was placed.

- What are your primary concerns with Molly?

- Why do you expect type I diabetic mellitus patients such as Molly engage in behaviors consistent with diabulimia?

- As the case manager, what resources would you recommend prior to discharge?

Nursing Case Studies by and for Student Nurses Copyright © by jaimehannans is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- DOI: 10.2337/DIASPECT.16.1.32

- Corpus ID: 73083750

Case Study: A Patient With Uncontrolled Type 2 Diabetes and Complex Comorbidities Whose Diabetes Care Is Managed by an Advanced Practice Nurse

- G. Spollett

- Published 2003

- Diabetes Spectrum

5 Citations

Management of ketosis-prone type 2 diabetes mellitus., integrating a pico clinical questioning to the ql4pomr framework for building evidence-based clinical case reports, nursing practice guideline for foot care for patients with diabetes in thailand, goal-driven structured argumentation for patient management in a multimorbidity setting, logic and argumentation: third international conference, clar 2020, hangzhou, china, april 6–9, 2020, proceedings, 18 references, using a primary nurse manager to implement dcct recommendations in a large pediatric program, diabetes in urban african americans. iii. management of type ii diabetes in a municipal hospital setting., primary care outcomes in patients treated by nurse practitioners or physicians: a randomized trial., caring for a child with diabetes: the effect of specialist nurse care on parents' needs and concerns., standards of medical care for patients with diabetes mellitus, management of patients with diabetes by nurses with support of subspecialists., a practical approach to type 2 diabetes., the diabetes control and complications trial (dcct): the trial coordinator perspective, oral antihyperglycemic therapy for type 2 diabetes: scientific review., caring for feet: patients and nurse practitioners working together., related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Diabetes Mellitus

The major sources of the glucose that circulates in the blood are through the absorption of ingested food in the gastrointestinal tract and formation of glucose by the liver from food substances.

- Diabetes mellitus is a group of metabolic diseases that occurs with increased levels of glucose in the blood.

- Diabetes mellitus most often results in defects in insulin secretion, insulin action, or even both.

Classification

The classification system of diabetes mellitus is unique because research findings suggest many differences among individuals within each category, and patients can even move from one category to another, except for patients with type 1 diabetes .

- Diabetes has major classifications that include type 1 diabetes , type 2 diabetes , gestational diabete s, and diabetes mellitus associated with other conditions.

- The two types of diabetes mellitus are differentiated based on their causative factors, clinical course, and management.

Pathophysiology

Diabetes Mellitus has different courses of pathophysiology because of it has several types

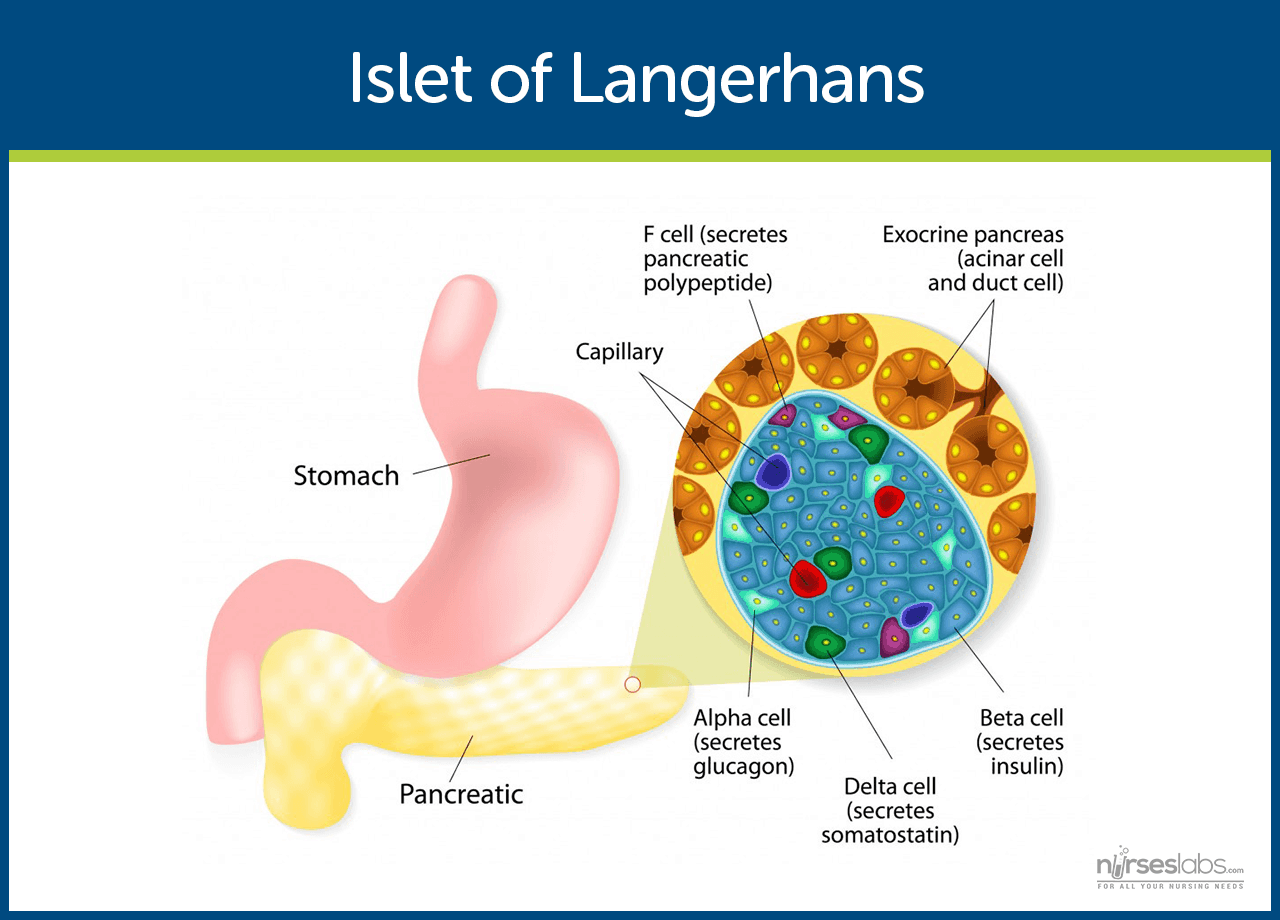

- Insulin is secreted by beta cells in the pancreas and it is an anabolic hormone.

- When we consume food, insulin moves glucose from blood to muscle , liver, and fat cells as insulin level increases.

- The functions of insulin include the transport and metabolism of glucose for energy, stimulation of storage of glucose in the liver and muscle, serves as the signal of the liver to stop releasing glucose, enhancement of the storage of dietary fat in adipose tissue, and acceleration of the transport of amino acid into cells.

- Insulin and glucagon maintain a constant level of glucose in the blood by stimulating the release of glucose from the liver.

Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus

- Type 1 diabetes mellitus is characterized by destruction of the pancreatic beta cel ls.

- A common underlying factor in the development of type 1 diabetes is a genetic susceptibility .

- Destruction of beta cells leads to a decrease in insulin production, unchecked glucose production by the liver and fasting hyperglycemia .

- Glucose taken from food cannot be stored in the liver anymore but remains in the blood stream.

- The kidneys will not reabsorb the glucose once it has exceeded the renal threshold, so it will appear in the urine and be called glycosuria .

- Excessive loss of fluids is accompanied by excessive excretion of glucose in the urine leading to osmotic diuresis .

- There is fat breakdown which results in ketone production , the by-product of fat breakdown.

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

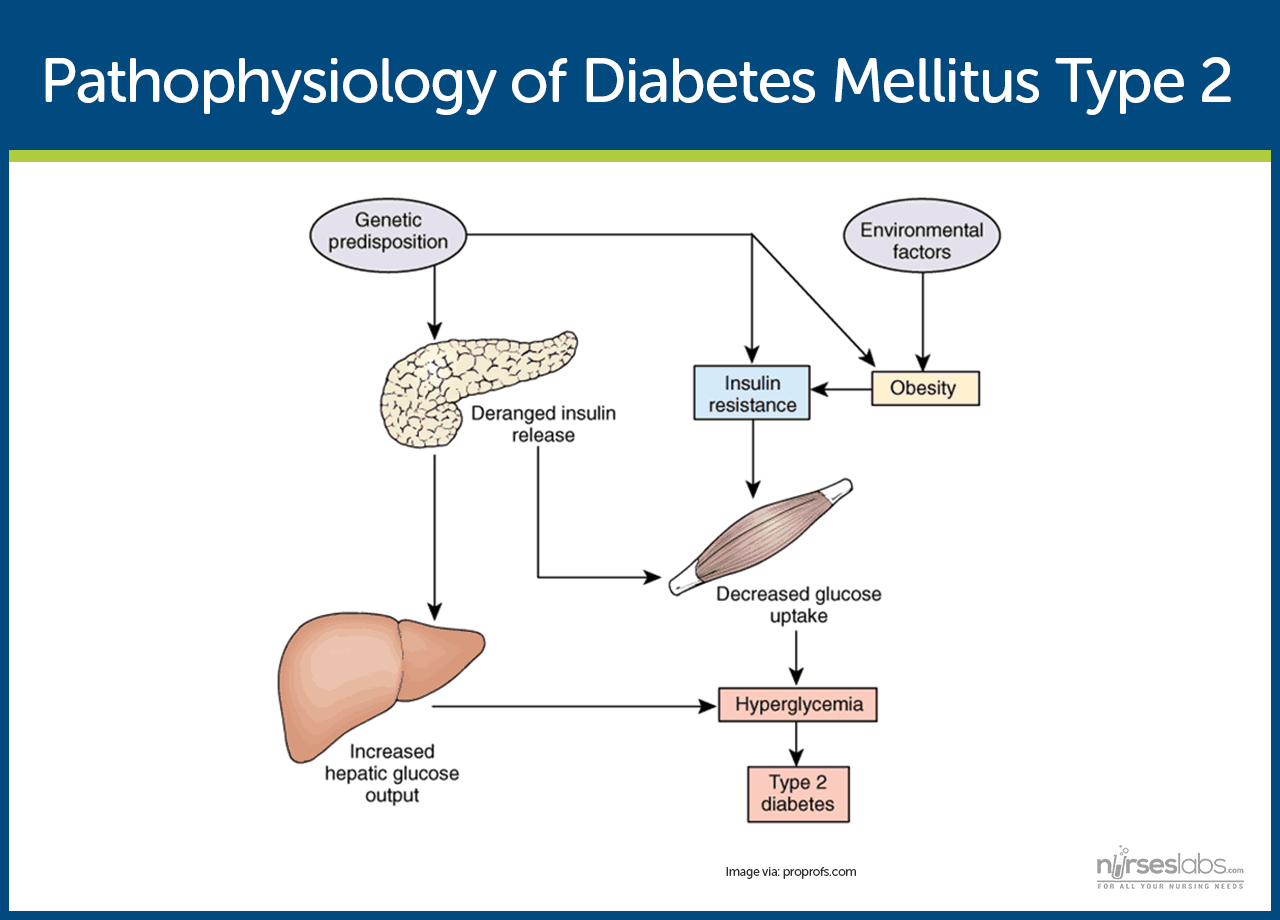

- Type 2 diabetes mellitus has major problems of insulin resistance and impaired insulin secretion .

- Insulin could not bind with the special receptors so insulin becomes less effective at stimulating glucose uptake and at regulating the glucose release.

- There must be increased amounts of insulin to maintain glucose level at a normal or slightly elevated level.

- However, there is enough insulin to prevent the breakdown of fats and production of ketones.

- Uncontrolled type 2 diabetes could lead to hyperglycemic, hyperosmolar nonketotic syndrome .

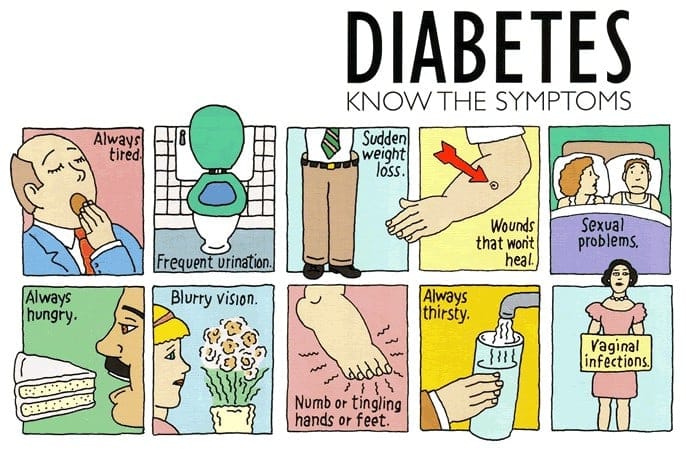

- The usual symptoms that the patient may feel are polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, fatigue , irritability, poorly healing skin wounds, vaginal infections, or blurred vision .

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus

- With gestational diabetes mellitus ( GDM ) , the pregnant woman experiences any degree of glucose intolerance with the onset of pregnancy.

- The secretion of placental hormones causes insulin resistance , leading to hyperglycemia.

- After delivery, blood glucose levels in women with GDM usually return to normal or later on develop type 2 diabetes.

Epidemiology

Diabetes mellitus is now one of the most common disease all over the world. Here are some quick facts and numbers on diabetes mellitus.

- More than 23 million people in the United States have diabetes, yet almost one-third are undiagnosed.

- By 2030, the number of cases is expected to increase more than 30 million.

- Diabetes is especially prevalent in the elderly ; 50% of people older than 65 years old have some degree of glucose intolerance.

- People who are 65 years and older account for 40% of people with diabetes.

- African-Americans and members of other racial and ethnic groups are more likely to develop diabetes.

- In the United States, diabetes is the leading cause of non-traumatic amputations, blindness in working-age adults, and end-stage renal disease .

- Diabetes is the third leading cause of death from disease.

- Costs related to diabetes are estimated to be almost $174 billion annually.

The exact cause of diabetes mellitus is actually unknown, yet there are factors that contribute to the development of the disease.

- Genetics. Genetics may have played a role in the destruction of the beta cells in type 1 DM.

- Environmental factors. Exposure to some environmental factors like viruses can cause the destruction of the beta cells.

- Weight. Excessive weight or obesity is one of the factors that contribute to type 2 DM because it causes insulin resistance.

- Inactivity. Lack of exercise and a sedentary lifestyle can also cause insulin resistance and impaired insulin secretion.

- Weight. If you are overweight before pregnancy and added extra weight, it makes it hard for the body to use insulin.

- Genetics. If you have a parent or a sibling who has type 2 DM, you are most likely predisposed to GDM.

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical manifestations depend on the level of the patient’s hyperglycemia.

- Polyuria or increased urination . Polyuria occurs because the kidneys remove excess sugar from the blood, resulting in a higher urine production.

- Polydipsia or increased thirst. Polydipsia is present because the body loses more water as polyuria happens, triggering an increase in the patient’s thirst.

- Polyphagia or increased appetite. Although the patient may consume a lot of food but glucose could not enter the cells because of insulin resistance or lack of insulin production.

- Fatigue and weakness . The body does not receive enough energy from the food that the patient is ingesting.

- Sudden vision changes. The body pulls away fluid from the eye in an attempt to compensate the loss of fluid in the blood, resulting in trouble in focusing the vision.

- Tingling or numbness in hands or feet. Tingling and numbness occur due to a decrease in glucose in the cells.

- Dry skin. Because of polyuria, the skin becomes dehydrated.

- Skin lesions or wounds that are slow to heal. Instead of entering the cells, glucose crowds inside blood vessels, hindering the passage of white blood cells which are needed for wound healing .

- Recurrent infections. Due to the high concentration of glucose, bacteria thrives easily.

Appropriate management of lifestyle can effectively prevent the development of diabetes mellitus.

- Standard lifestyle recommendations, metformin , and placebo are given to people who are at high risk for type 2 diabetes.

- The 16-lesson curriculum of the intensive program of lifestyle modifications focused on weight reduction of greater than 7% of initial body weight and physical activity of moderate intensity.

- It also included behavior modification strategies that can help patients achieve their weight reduction goals and participate in exercise.

Complications

If diabetes mellitus is left untreated, several complications may arise from the disease

- Hypoglycemia. Hypoglycemia occurs when the blood glucose falls to less than 50 to 60 mg/dL because of too much insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents, too little food, or excessive physical activity .

- Diabetic Ketoacidosis . DKA is caused by an absence or markedly inadequate amounts of insulin and has three major features of hyperglycemia, dehydration and electrolyte loss, and acidosis.

- Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar Nonketotic Syndrome . HHNS is a serious condition in which hyperosmolarity and hyperglycemia predominate with alteration in the sense of awareness.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Hypoglycemia may occur suddenly in a patient considered hyperglycemic because their blood glucose levels may fall rapidly to 120 mg/dL or even less.

- Serum glucose: Increased 200–1000 mg/dL or more.

- Serum acetone ( ketones ): Strongly positive.

- Fatty acids: Lipids, triglycerides , and cholesterol level elevated.

- Serum osmolality: Elevated but usually less than 330 mOsm/L.

- Glucagon: Elevated level is associated with conditions that produce (1) actual hypoglycemia , (2) relative lack of glucose (e.g., trauma , infection ), or (3) lack of insulin. Therefore, glucagon may be elevated with severe DKA despite hyperglycemia.

- Glycosylated hemoglobin ( HbA 1C ): Evaluates glucose control during past 8–12 wk with the previous 2 wk most heavily weighted. Useful in differentiating inadequate control versus incident-related DKA (e.g., current upper respiratory infection [URI]). A result greater than 8% represents an average blood glucose of 200 mg/dL and signals a need for changes in treatment.

- Serum insulin: May be decreased/absent (type 1) or normal to high (type 2), indicating insulin insufficiency/improper utilization (endogenous/exogenous). Insulin resistance may develop secondary to formation of antibodies.

- Electrolytes :

- Sodium : May be normal, elevated, or decreased.

- Potassium : Normal or falsely elevated (cellular shifts), then markedly decreased.

- Phosphorus: Frequently decreased.

- Arterial blood gases ( ABGs ): Usually reflects low pH and decreased HCO 3 (metabolic acidosis) with compensatory respiratory alkalosis.

- CBC: Hct may be elevated ( dehydration ); leukocytosis suggest hemoconcentration, response to stress or infection.

- BUN: May be normal or elevated ( dehydration /decreased renal perfusion).

- Serum amylase: May be elevated, indicating acute pancreatitis as cause of DKA.

- Thyroid function tests: Increased thyroid activity can increase blood glucose and insulin needs.

- Urine: Positive for glucose and ketones; specific gravity and osmolality may be elevated.

- Cultures and sensitivities: Possible UTI, respiratory or wound infections.

Medical Management

Here are some medical interventions that are performed to manage diabetes mellitus.

- Normalize insulin activity . This is the main goal of diabetes treatment — normalization of blood glucose levels to reduce the development of vascular and neuropathic complications.

- Intensive treatment. Intensive treatment is three to four insulin injections per day or continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion, insulin pump therapy plus frequent blood glucose monitoring and weekly contacts with diabetes educators.

- Exercise caution with intensive treatment. Intensive therapy must be done with caution and must be accompanied by thorough education of the patient and family and by responsible behavior of patient.

- Diabetes management has five components and involves constant assessment and modification of the treatment plan by healthcare professionals and daily adjustments in therapy by the patient.

Nutritional Management

- The foundations. Nutrition, meal planning , and weight control are the foundations of diabetes management.

- Consult a professional. A registered dietitian who understands diabetes management has the major responsibility for designing and teaching this aspect of the therapeutic plan.

- Healthcare team should have the knowledge. Nurses and other health care members of the team must be knowledgeable about nutritional therapy and supportive of patients who need to implement nutritional and lifestyle changes.

- Weight loss. This is the key treatment for obese patients with type 2 diabetes.

- How much weight to lose? A weight loss of as small as 5% to 10% of the total body weight may significantly improve blood glucose levels.

- Other options for diabetes management. Diet education, behavioral therapy, group support, and ongoing nutritional counselling should be encouraged.

Meal Planning

- Criteria in meal planning . The meal plan must consider the patient’s food preferences, lifestyle, usual eating times, and ethnic and cultural background.

- Managing hypoglycemia through meals. To help prevent hypoglycemic reactions and maintain overall blood glucose control, there should be consistency in the approximate time intervals between meals with the addition of snacks as needed.

- Assessment is still necessary. The patient’s diet history should be thoroughly reviewed to identify his or her eating habits and lifestyle.

- Educate the patient. Health education should include the importance of consistent eating habits, the relationship of food and insulin, and the provision of an individualized meal plan.

- The nurse ‘s role. The nurse plays an important role in communicating pertinent information to the dietitian and reinforcing the patients for better understanding .

Other Dietary Concerns

- Alcohol consumption. Patients with diabetes do not need to give up alcoholic beverages entirely, but they must be aware of the potential adverse of alcohol specific to diabetes.

- If a patient with diabetes consumes alcohol on an empty stomach , there is an increased likelihood of hypoglycemia .

- Reducing hypoglycemia . The patient must be cautioned to consume food along with alcohol, however, carbohydrate consumed with alcohol may raise blood glucose.

- How much alcohol intake? Moderate intake is considered to be one alcoholic beverage per day for women and two alcoholic beverages per day for men.

- Artificial sweeteners. Use of artificial sweeteners is acceptable, and there are two types of sweeteners: nutritive and nonnutritive.

- Types of sweeteners. Nutritive sweeteners include all of which provides calories in amounts similar to sucrose while nonnutritive have minimal or no calories.

- Exercise. Exercise lowers blood glucose levels by increasing the uptake of glucose by body muscles and by improving insulin utilization.

- A person with diabetes should exercise at the same time and for the same amount each day or regularly.

- A slow, gradual increase in the exercise period is encouraged.

Using a Continuous Glucose Monitoring System

- A continuous glucose monitoring system is inserted subcutaneously in the abdomen and connected to the device worn on a belt.

- This can be used to determine whether treatment is adequate over a 24-hour period.

- Blood glucose readings are analyzed after 72 hours when the data has been downloaded from the device.

Testing for Glycated Hemoglobin

- Glycated hemoglobin or glycosylated hemoglobin, HgbA1C, or A1C reflects the average blood glucose levels over a period of approximately 2 to 3 months.

- The longer the amount of glucose in the blood remains above normal, the more glucose binds to hemoglobin and the higher the glycated hemoglobin becomes.

- Normal values typically range from 4% to 6% and indicate consistently near-normal blood glucose concentrations.

Pharmacologic Therapy

- Exogenous insulin. In type 1 diabetes, exogenous insulin must be administered for life because the body loses the ability to produce insulin.

- Insulin in type 2 diabetes. In type 2 diabetes, insulin may be necessary on a long-term basis to control glucose levels if meal planning and oral agents are ineffective.

- Self-Monitoring Blood Glucose (SMBG). This is the cornerstone of insulin therapy because accurate monitoring is essential.

- Human insulin. Human insulin preparations have a shorter duration of action because the presence of animal proteins triggers an immune response that results in the binding of animal insulin.

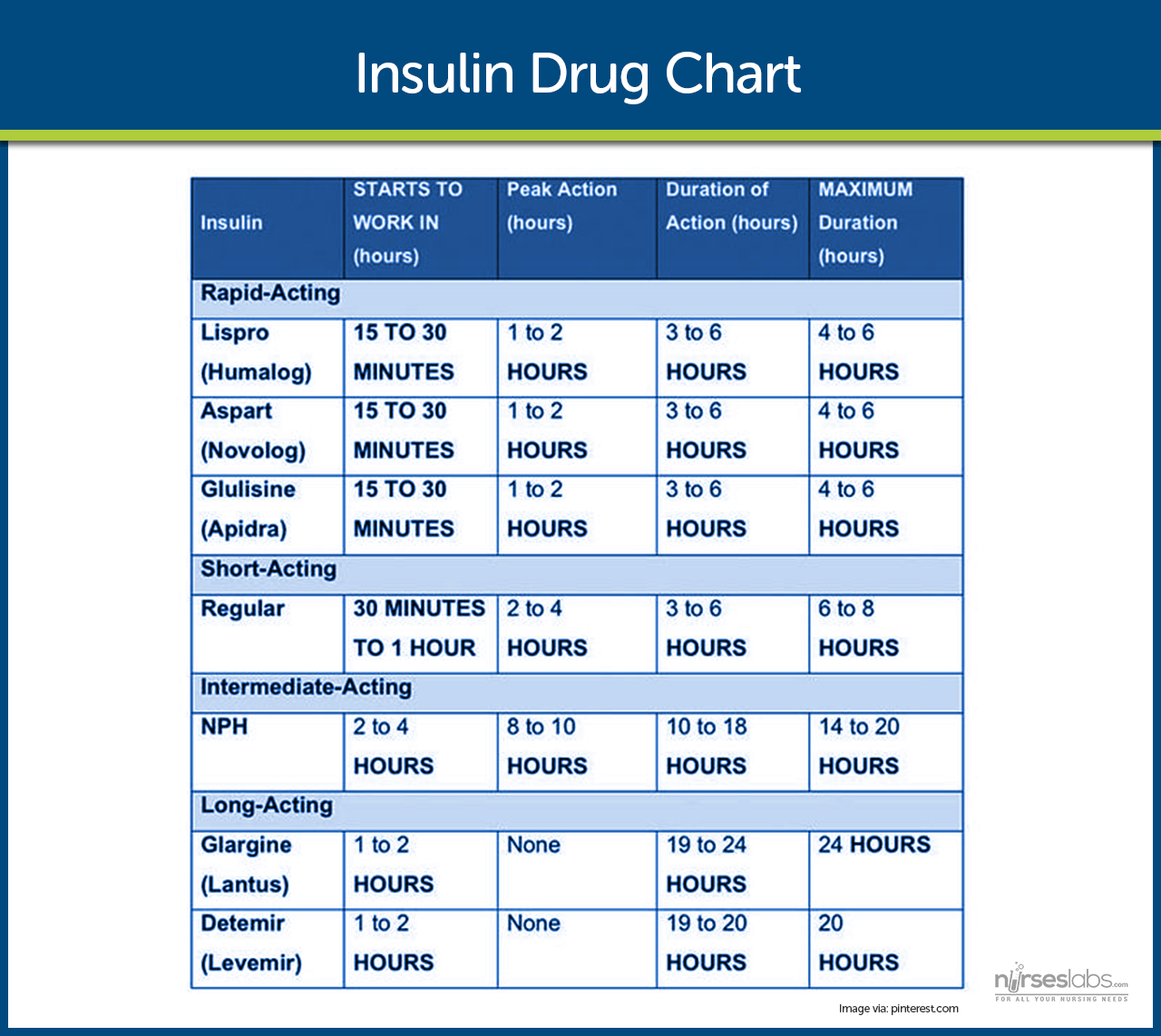

- Rapid-acting insulin. Rapid-acting insulins produce a more rapid effect that is of shorter duration than regular insulin.

- Short-acting insulin. Short-acting insulins or regular insulin should be administered 20-30 minutes before a meal , either alone or in combination with a longer-acting insulin.

- Intermediate-acting insulin. Intermediate-acting insulins or NPH or Lente insulin appear white and cloudy and should be administered with food around the time of the onset and peak of these insulins.

- The rapid-acting and short-acting insulins are expected to cover the increase in blood glucose levels after meals; immediately after the injection.

- Intermediate-acting insulins are expected to cover subsequent meals, and long-acting insulins provide a relatively constant level of insulin and act as a basal insulin.

- Approaches to insulin therapy. There are two general approaches to insulin therapy: conventional and intensive.

- Conventional regimen. Conventional regimen is a simplified regimen wherein the patient should not vary meal patterns and activity levels.

- Intensive regimen. Intensive regimen uses a more complex insulin regimen to achieve as much control over blood glucose levels as is safe and practical.

- A more complex insulin regimen allows the patient more flexibility to change the insulin doses from day to day in accordance with changes in eating and activity patterns.

- Methods of insulin delivery. Methods of insulin delivery include traditional subcutaneous injections, insulin pens, jet injectors, and insulin pumps.

- Insulin pens use small prefilled insulin cartridges that are loaded into a pen-like holder.

- Insulin is delivered by dialing in a dose or pushing a button for every 1- or 2-unit increment administered.

- Jet injectors deliver insulin through the skin under pressure in an extremely fine stream.

- Insulin pumps involve continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion with the use of small, externally worn devices that closely mimic the function of the pancreas.

- Oral antidiabetic agents may be effective for patients who have type 2 diabetes that cannot be treated by MNT and exercise alone.

- Oral antidiabetic agents . Oral antidiabetic agents include sulfonylureas , biguanides, alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, thiazolidinediones , and dipeptidyl-peptidase-4.

- Half of all the patients who used oral antidiabetic agents eventually require insulin, and this is called secondary failure .

- Primary failure occurs when the blood glucose level remains high 1 month after initial medication use.

Nursing Management

Nurses should provide accurate and up-to-date information about the patient’s condition so that the healthcare team can come up with appropriate interventions and management.

For the complete and comprehensive nursing care plan and management of patients with diabetes, please visit 20 Diabetes Mellitus Nursing Care Plans

Practice Quiz: Diabetes Mellitus

For our diabetes mellitus practice quiz, please do visit our nursing test bank for diabetes:

- Diabetes Mellitus Reviewer and NCLEX Questions (100 Items)

7 thoughts on “Diabetes Mellitus”

Humbled by the content I read here.. this is absolutely exceptional..work made easier

please can you give me your opinion on this weather is “Diabetes- only progression or can be regressed”

Perfect notes

Lesson is extremely explicit and easy to grasp

Hi Jennifer, Awesome to hear the lesson on diabetes mellitus was clear and easy to get! 😊 Anything in particular you found really helpful or any other topics you’re keen to explore?

Very effective

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

- Cancer Nursing Practice

- Emergency Nurse

- Evidence-Based Nursing

- Learning Disability Practice

- Mental Health Practice

- Nurse Researcher

- Nursing Children and Young People

- Nursing Management

- Nursing Older People

- Nursing Standard

- Primary Health Care

- RCN Nursing Awards

- Nursing Live

- Nursing Careers and Job Fairs

- CPD webinars on-demand

- --> Advanced -->

| | | |

- Clinical articles

- CPD articles

- CPD Quizzes

- Expert advice

- Clinical placements

- Study skills

- Clinical skills

- University life

- Person-centred care

- Career advice

- Revalidation

Art & Science Previous Next

Type 2 diabetes: a case study, priscilla cunningham nursing student, queen’s university belfast, belfast, northern ireland, helen noble lecturer, health services research, school of nursing and midwifery, queen’s university belfast, belfast, northern ireland.

Increased prevalence of diabetes in the community has been accompanied by an increase in diabetes in hospitalised patients. About a quarter of these patients experience a hypoglycaemic episode during their admission, which is associated with increased risk of mortality and length of stay. This article examines the aetiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment of type 2 diabetes using a case study approach. The psychosocial implications for the patient are also discussed. The case study is based on a patient with diabetes who was admitted to hospital following a hypoglycaemic episode and cared for during a practice placement. The importance of early diagnosis of diabetes and the adverse effects of delayed diagnosis are discussed.

Nursing Standard . 29, 5, 37-43. doi: 10.7748/ns.29.5.37.e9142

This article has been subject to double blind peer review

Received: 20 May 2014

Accepted: 15 July 2014

Blood glucose - case study - diabetes - glucose testing - hyperglycaemia - hypoglycaemia - insulin resistance - sulfonylureas - type 2 diabetes

User not found

Want to read more?

Already have access log in, 3-month trial offer for £5.25/month.

- Unlimited access to all 10 RCNi Journals

- RCNi Learning featuring over 175 modules to easily earn CPD time

- NMC-compliant RCNi Revalidation Portfolio to stay on track with your progress

- Personalised newsletters tailored to your interests

- A customisable dashboard with over 200 topics

Alternatively, you can purchase access to this article for the next seven days. Buy now

Are you a student? Our student subscription has content especially for you. Find out more

07 October 2014 / Vol 29 issue 5

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DIGITAL EDITION

- LATEST ISSUE

- SIGN UP FOR E-ALERT

- WRITE FOR US

- PERMISSIONS

Share article: Type 2 diabetes: a case study

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience.

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) Case Study (45 min)

Watch More! Unlock the full videos with a FREE trial

Included In This Lesson

Study tools.

Access More! View the full outline and transcript with a FREE trial

Mr. Logan is a 32-year-old male with a history of DM Type I. He presented to the Emergency Department (ED) after being found by his family with decreased LOC, rapid heavy breathing, and fruity breath. His family reports flu-like symptoms for the last few days.

Before even gathering further information - what do you think is going on? Why?

Diabetic Ketoacidosis – he is a Type I Diabetic with heavy breathing (Kussmaul Respirations) and fruity breath. These are classic signs. It’s important to recognize them and immediately begin anticipating the patient’s needs.

What diagnostic or lab tests would you expect the provider to order?

- Complete metabolic panel to check serum glucose, anion gap, potassium, etc.

- Arterial Blood Gas to assess for acidosis

- Urinalysis to look for ketones

The nurse draws a Complete Metabolic Panel and notifies the Respiratory Therapist to obtain an Arterial Blood Gas. Upon further assessment, the patient is oriented x 2 and drowsy. He is breathing heavily. Lungs are clear to auscultation, S1/S2 present, bowel sounds active, pulses present and palpable x 4 extremities. A POC glucose reads >450 (meter max).

Vital signs are as follows: HR 87 RR 32 BP 123/77 SpO 2 96%

Mr. Logan’s labs result and show the following: Glucose 804 mg/dL K 6.1 mEq/L BUN 39 mg/dL pH 7.12 Cr 1.9 mg/dL pCO 2 30 Anion Gap 29 mEq/L HCO 3 – 17 Urine = Positive for Ketones

Using these lab results, explain what is going on physiologically with Mr. Logan.

- His glucose is extremely high and he is positive for ketones, which says that his body is having to break down fatty acids to make energy

- His anion gap is high, meaning there are other “ions” in the system besides the electrolytes – in this case, the extra acids are creating this ‘gap’

- He is in metabolic acidosis because of the ketoacids – this is what’s causing the Kussmaul respirations – his body is trying to breathe off CO2 to bring his pH up

- His potassium is high because the body will kick potassium out of the cells to compensate for an acidotic state. This way instead of having H+ (acids) in the blood stream, we have K+ – this protects many tissues, but puts our heart at risk

- His BUN/Cr are elevated because of the dehydration caused by osmotic diuresis (caused by hyperglycemia and hyperosmolarity)

What is the #1 priority for Mr. Logan at this time?

- The #1 priority for DKA is to get the blood sugar down and get insulin into the system. Getting insulin into the system allows the gluconeogenesis to STOP (so that the body will STOP making ketoacids and start using the glucose it has).

- The #2 priority is fluid replacement due to severe dehydration from osmotic diuresis

The provider writes an order for an Insulin Lispro infusion IV, titrating to decrease blood glucose per protocol, 1L NS bolus NOW, and a continuous infusion of Normal Saline IV at 250 mL/hr, and to change the fluids to D5 ½ NS at 125 mL/hr once the blood glucose level falls below 250 mg/dL.

What is the first action you should take after receiving these orders?

Remind the provider that the only insulin that can be given IV is Regular Insulin and request that he change the order. Call the Pharmacist if you have to

- **Note – most facilities have a computerized ordering that prevents something like this from happening, but it’s important that you know this!!

The provider adjusts the order to Regular Insulin IV infusion. Orders are also written for hourly POC glucose checks and a q2h BMP.

Why is it important to check a BMP frequently? What are we monitoring for?

- Frequent BMP’s are important to confirm the blood glucose when the POC meter is just reading MAX.

- It’s also important to monitor the Anion Gap to see when it “closes” – indicating resolution of the acidosis

- We are also monitoring potassium levels. They will start elevated, but insulin drives potassium into the cells – causing it to decrease rapidly.

After 4 hours and another 1L bolus of NS, Mr. Logan’s blood glucose level has dropped to 174 mg/dL, but his anion gap is still 19. The nurse changes his fluids to D5 ½ NS per the order and continues the insulin infusion. The most recent BMP showed a K of 3.7, down from 6.1, so the provider orders to give 40 mEq of KCl PO.

Why is the insulin continued even after the blood glucose decreases?

- The goal is to stop gluconeogenesis and reverse the acidosis. The glucose may fall rapidly while there are still ketoacids being made.

- By giving D5 ½ NS infusion with the insulin, we can continue to bring down the acidosis process while maintaining safe blood sugars.

After another 4 hours, Mr. Logan’s anion gap is now 12, a repeat ABG shows a pH of 7.36 with normal CO 2 and HCO 3 – levels. The nurse begins to transition Mr. Logan off of the IV infusion to SubQ insulin per protocol. He is feeling much better and says he’s embarrassed that he had to be brought to the hospital.

What education can you provide Mr. Logan to help him understand why this happened and how to prevent it from recurring in the future?

- When you are ill, you should check your blood sugar more often as sometimes the body’s healing processes and stress response can make your sugar go higher than normal

- Notify your provider if you’re ill, they may recommend increasing your long-acting insulin

- Notify your provider or go to the ED at the FIRST indication of DKA – fruity breath, heavy breathing, feeling dry and hot, excessive urination, blurry vision, or a blood glucose over 400 mg/dL or over your meter MAX.

- If you have an insulin pump, make sure it is working appropriately – if not, notify your provider or turn the pump OFF and switch to SubQ insulin until the pump can be fixed

- **Note – if a patient comes in with an insulin pump, it should always be turned OFF – we will manage their sugars with SubQ insulin and don’t want them to receive a double dose.

View the FULL Outline

When you start a FREE trial you gain access to the full outline as well as:

- SIMCLEX (NCLEX Simulator)

- 6,500+ Practice NCLEX Questions

- 2,000+ HD Videos

- 300+ Nursing Cheatsheets

“Would suggest to all nursing students . . . Guaranteed to ease the stress!”

Nursing Case Studies

This nursing case study course is designed to help nursing students build critical thinking. Each case study was written by experienced nurses with first hand knowledge of the “real-world” disease process. To help you increase your nursing clinical judgement (critical thinking), each unfolding nursing case study includes answers laid out by Blooms Taxonomy to help you see that you are progressing to clinical analysis.We encourage you to read the case study and really through the “critical thinking checks” as this is where the real learning occurs. If you get tripped up by a specific question, no worries, just dig into an associated lesson on the topic and reinforce your understanding. In the end, that is what nursing case studies are all about – growing in your clinical judgement.

Nursing Case Studies Introduction

Cardiac nursing case studies.

- 6 Questions

- 7 Questions

- 5 Questions

- 4 Questions

GI/GU Nursing Case Studies

- 2 Questions

- 8 Questions

Obstetrics Nursing Case Studies

Respiratory nursing case studies.

- 10 Questions

Pediatrics Nursing Case Studies

- 3 Questions

- 12 Questions

Neuro Nursing Case Studies

Mental health nursing case studies.

- 9 Questions

Metabolic/Endocrine Nursing Case Studies

Other nursing case studies.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Putting Theory Into Practice: A Case Study of Diabetes-Related Behavioral Change Interventions on Chicago's South Side

Monica e. peek.

1 University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA

Molly J. Ferguson

Tonya p. roberson, marshall h. chin.

Diabetes self-management is central to diabetes care overall, and much of self-management entails individual behavior change, particularly around dietary patterns and physical activity. Yet individual-level behavior change remains a challenge for many persons with diabetes, particularly for racial/ethnic minorities who disproportionately face barriers to diabetes-related behavioral changes. Through the South Side Diabetes Project, officially known as “Improving Diabetes Care and Outcomes on the South Side of Chicago,” our team sought to improve health outcomes and reduce disparities among residents in the largely working-class African American communities that comprise Chicago's South Side. In this article, we describe several aspects of the South Side Diabetes Project that are directly linked to patient behavioral change, and discuss the theoretical frameworks we used to design and implement our programs. We also briefly discuss more downstream program elements (e.g., health systems change) that provide additional support for patient-level behavioral change.

Introduction

Diabetes self-management is central to diabetes care overall, and much of self-management entails individual behavior change, particularly around dietary patterns and physical activity. In a recent review of behavior change, Fisher et al. (2011) found that behavior changes are associated with multiple aspects of diabetes, including the onset of disease and disease prevention (e.g., dietary intake and obesity are risk factors for the development of diabetes; lifestyle changes can prevent diabetes in high-risk individuals; Diabetes Prevention Research Group, 2002 ; Eyre, Kahn, & Robertson, 2004 ; Tuomilehto et al., 2001 ), disease management (e.g., diabetes self-management programs can improve disease management, improve metabolic control, and prevent complications; The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group, 1993 ; Norris, Engelgau, & Narayan, 2001 ; Norris, Lau, Smith, Schmid, & Engelgau, 2002 ), and quality of life (e.g., behavior changes can reduce distress and depressive symptoms, increase emotional and social function, reduce anxiety, and improve general quality of life among persons with diabetes; Blumenthal et al., 2005 ; Cochran & Conn, 2008 ; Vale et al., 2003 ).

Despite the strong evidence base and the growing public health need for implementation, individual-level behavior change remains a challenge for many persons with diabetes. Racial/ethnic minorities disproportionately face barriers to diabetes-related changes, including access to healthy food, safe places for physical activity, diabetes education, and other self-management resources. Through the South Side Diabetes Project, officially known as “Improving Diabetes Care and Outcomes on the South Side of Chicago,” our team sought to improve health outcomes and reduce disparities among residents in the largely working-class African American communities that comprise Chicago's South Side ( Chin, Ferguson, Goddu, Maltby, & Peek, in press ; ( Peek, Wilkes, et al., 2012 ). A key part of this strategy involves the promotion of individual behavior change among persons with diabetes—changes in healthy behaviors (e.g., nutrition, physical activity), treatment adherence (e.g., medication adherence), self-care activities (e.g., self–foot examinations), and active involvement in treatment decisions with their health care providers (i.e., shared decision making [SDM]).

In this article, we describe several aspects of the South Side Diabetes Project that are directly linked to patient behavioral change, and discuss the theoretical frameworks we used to design and implement our programs. We also briefly discuss more macro-level program elements (e.g., health systems change) that provide additional support for patient-level behavioral change.

Program Components that Support Diabetes-Related Behavior Change

Patient education classes.

We have developed a patient empowerment curriculum that provides culturally tailored, evidence-based diabetes education with skills training in patient–provider communication and SDM. This educational program has been described in detail elsewhere ( Peek, Harmon, et al., 2012 ), but it has been summarized here. The classes met once weekly for 2 to 3 hours for 10 consecutive weeks. The first 6 weeks consisted of culturally tailored diabetes education, which modified the evidence-based BASICS curriculum developed by the International Diabetes Center and covered basic diabetes knowledge and management skills ( Peek, Harmon, et al., 2012 ). The curriculum was adapted to meet the literacy, adult-learning, and cultural needs of the population. The following 3 weeks addressed patient–provider communication and SDM; patients were taught skills and strategies to become more actively involved in discussions and decisions about their diabetes treatment plans ( Peek, Harmon, et al., 2012 ). The SDM curriculum addressed identified barriers, cultural norms, and beliefs among low-income African Americans with diabetes that we had previously identified about SDM ( Peek et al., 2008 ; Peek et al., 2009 ; Peek et al., 2010 ). The classes were interactive and used role-play, testimonials, games, film, and hands-on skills training to help teach key educational components and support behavior change skills. Each cohort was led by a multidisciplinary team of certified diabetes educators, nurses, dietitians, and physicians. Family and friends were invited to the classes to help support patients in developing and sustaining diabetes-related behavioral changes. Statistically significant improvements were seen in diabetes self-care behaviors, including following a “healthful eating plan,” self-glucose monitoring, exercise, and self–foot care, as well as glucose control (i.e., HbA1c [glycated haemoglobin] values; ( Peek, Harmon, et al., 2012 ).

“Prescriptions” for Food and Exercise

Our team has worked collaboratively with Walgreens and the 61st Street Farmer's Market to provide “Food Rx” for fresh fruits and vegetables. Our Food Rx program has been described in detail elsewhere ( Goddu, Roberson, Raffel, Chin, & Peek, in press ), but it is briefly summarized here. Nine Walgreens stores were selected based on their “food desert” designation (i.e., are located within a food desert and provide expanded healthy food options) and location within the catchment area of one of our six participating health centers. The Farmer's Market was selected based on its proximity to the University of Chicago and its commitment to providing skills-based education (e.g., cooking demonstrations) and serving low-income communities. For example, this Farmer's Market is the first and largest market participant in Illinois' food stamp (LINK) program, where the value of the LINK card purchase is doubled by the Farmer's Market ( Experimental Station, 2009 ). Physicians and mid-level providers (i.e., physician assistants and nurse practitioners) sign the Food Rx, which are distributed in the clinic to interested patients. The Food Rx combine the power of physician recommendations regarding lifestyle changes with patient educational information (the Food Rx are attached to a one-page low-literacy nutritional sheet that highlights examples of food recommendations), financial incentives (on the back of the Food Rx is a $5 coupon for Walgreens or a $9 voucher for the Farmer's Market), and information about local community resources.

Similar to the Food Rx, we have promoted an Exercise Rx where high-risk obese patients (i.e., those with diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and/or asthma) can receive prescriptions redeemable for 6 months of free services at any of the 64 Chicago Park District locations, which offer a variety of fitness classes and services.

Food Shopping Tours

Each month at the Save-A-Lot (SAL) grocery, a low-cost grocery chain prevalent on Chicago's South Side, we conduct a grocery store tour called “Shop Smart, Save a Lot, and Be Healthy.” The tours are conducted three Saturdays a month at three different store locations on Chicago's South Side. Participants are taken around the perimeters of the store (where fresh/frozen items are showcased) and taught how to read food labels, shop healthy on a budget, and make healthy food choices. At the end of the tour, participants receive a $25 gift card, donated by SAL, to purchase healthy food items. Initially led by a registered dietician/certified diabetes educator, our team has trained over 30 community members (e.g., fitness instructors, diabetes patients, nutritionists, public health students), who also lead the tours. Since January 2012, over 500 people have participated in the SAL tours, some of whom were referred from one of our participating health centers and 15 of whom had participated in our patient education classes.

We have adapted the food shopping script for the 61st Street Farmer's Market and Walgreens partner stores. Community members are currently doing educational tours of the Farmer's Market, where patients and community residents learn to identify and use the wide variety of produce at the market (that may have been previously unfamiliar), meet the farmers, and receive “special invitations” for the cooking demonstrations. In the first 4 months of the program, nearly 150 people have participated in the Farmer's Market tours. At Walgreens, pharmacists (also trained in diabetes education) are due to begin conducting tours of the healthy food sections in the stores in the fall of 2013 at participating stores.

Community Food Pantries

We have partnered with a local community center to enhance the access of our patients to free healthy food. The K.L.E.O. Community Family Life Center distributes several tons of fresh produce and other healthy food items, provided by the Greater Chicago Food Depository, to South Side community members every month. We have reorganized the food pantry to become a more comprehensive community health event by incorporating health education, fitness and cooking demonstrations, free health screenings, and referrals for regular medical care. Our team is currently working with several faith-based organizations and churches with food pantries to implement a similar model elsewhere on Chicago's South Side. From April 2012 to September 2013, we have had 1,459 touch points with 1,122 unique persons, 77 of whom were referred from one of our six health centers. An estimated 200 persons have been screened for diabetes and hypertension, and 85 persons without a regular physician were referred to a medical home.

Skills Training in Healthy Food Preparation/Cooking

Our team has worked closely with local chefs and culinary experts to provide skills training in healthy food preparation throughout the South Side, including our regular community events (e.g., Farmer's Market, K.L.E.O. Food Pantry) as well as other health events (e.g., health fairs). We have launched an Annual Diabetes Cook-Off, whose purpose is to showcase community-created diabetes-friendly dishes that are flavorful and can be enjoyed by everyone (i.e., also persons without diabetes). The Cook-Off is held in conjunction with a local community college's culinary arts program; instructors and students at the college support the Cook-Off semifinalists with the “professional presentation” of their food dishes to a panel of judges, which include celebrity chefs, nutritionists, persons with diabetes, and community leaders. The Diabetes Cook-Off is aired on a local cable television station and hosted by a local media personality. In the first year of the Cook-Off (2012), we had over 75 recipe submissions from patients and community members. Two of the semifinalists had completed our diabetes education classes.

Physical Activity Classes

Despite the widespread availability of parks within Chicago, many residents on the South Side do not have access to safe places for physical activity because of crime and other challenges within the local built environment. The Community Fitness Program is held at the Museum of Science and Industry and was designed by the University of Chicago Medical Center to encourage healthy fitness habits and to provide a safe place to exercise and help alleviate some of the most common barriers to exercise. The program offers a safe, warm place to walk for 90 minutes or participate in a free fitness class. We help promote this program within the patient education classes, clinics, and community venues.

In 2013, our team launched the Community Fitness Passport Program (CFPP), designed to expose South Side residents to a variety of fitness program (e.g., yoga, zumba, weight training) as well as a variety of local resources for physical activity (e.g., Park District centers, local churches with open fitness facilities, YMCA locations). The first CFPP class enrolled 25 participants, 19 of whom had completed the diabetes education classes. Because several of the “stops” along the Passport “journey” were at Chicago Park District centers, participants were exposed to existing facilities, programs, and resources that they could continue using through the Exercise Rx, which provide 6 months of free access to a local Park District center. The Passport program was designed to help community residents identify physical activity behaviors and facilities that they enjoyed and in which they would continue engaging after the CFPP ended.

Provider Workshops

We have conducted a workshop series among health care providers (i.e., physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants) and staff designed to increase knowledge and skills in motivational interviewing, patient–provider communication (with a focus on SDM), and culturally competent care. The goal of these interactive workshops is to equip health care teams to better activate diabetes patients from racial/ethnic minority communities and support such patients in making lifestyle changes to improve their health. To date, 100 providers and staff have been trained at the six participating health centers. In pre– posttest surveys using Likert-type response options, statistically significant improvements were noted in participants' self-rated ability to assess patients' readiness and motivation to change behavior, help patients initiate and maintain behavior change, understand potential barriers to engaging patients as active partners in care, and support patients' active participation in care ( p < .001 for all).

Mobile Technology Program

We developed a theory-driven interactive mobile technology program to support diabetes patients. The program components are described in detail elsewhere ( Dick et al., 2011 ; Nundy et al., 2012 ) but are summarized briefly here. Patients received interactive text messages to support them with diabetes self-management. Text messages were categorized into four content domains: education, medication reminders, glucose-monitoring reminders, and foot care reminders. Each domain was comprised of 2-week modules, which vary by topic and frequency of messages. The education domain covered diabetes self-management (e.g., purpose of medication and glucose monitoring, nutrition, foot care, and exercise) as well as living with a chronic illness (e.g., navigating the health care system, coping with stress). The other three domains supported behavior change with reminders (“Time to take your diabetes medication”), tips (“Think of your plate as a meal plan. Half your plate should be vegetables, a quarter meat or other proteins, and a quarter starches”), assessments (“On how many of the past 7 days did you take all of your diabetes medications?”), and feedback (“Great job!”). In addition, nurse-administrators used the automated text messaging to provide personalized self-management support for diabetes patients and facilitated care coordination with the primary care team.

Behavior Change Theoretical Frameworks

Several behavior change theoretical frameworks have informed the design and implementation of components of the South Side Diabetes Project. In this section, we describe the relevant theoretical constructs and discuss how we have directly applied them to our work. We use the following levels of the ecological model ( Fisher et al., 2002 ; Sallis, Owen, & Fisher, 2008 ) to organize the discussion: Patients; Family, Friends and Small Groups; Organizations, Communities, and Culture; and Government, Policies, and Large Systems. Within each of these levels, we describe behavioral theories that have direct relevance to our intervention and our target population. Some theories (e.g., health belief model) are more salient to behavior initiation (an important goal of the intervention), whereas other theories (e.g., self-efficacy) are more salient to the maintenance of behavior change.

At the individual patient level, we used several behavioral theories, which have some content overlap, to inform our program.

Health Belief Model

The health belief model theorizes that health behaviors are influenced by perceptions of the threat, severity of illness, and its consequences; perceived barriers to behavior change; and beliefs about the benefits of behavior change ( Janz & Becker, 1984 ). Thus, patients must first believe that they are at risk for the disease and/or its complications before behavior change can occur to reduce these risks. Risk perception has been shown to play an important role in developing healthy behaviors, such as dietary changes ( Janz & Becker, 1984 ). However, because the prevalence, morbidity, and mortality related to diabetes are disproportionately high among African Americans ( Chow, Foster, Gonzalez, & McIver, 2012 ), particularly within South Side communities, many of the persons with diabetes in our project believed that their risk for diabetes-related complications was significantly greater than it actually was. That is, they believed that personal complications from diabetes (e.g., renal failure, lower extremity amputation) were inevitable because of the experiences of friends and family members with the disease. Ironically, because of these fatalistic beliefs, many patients admitted to using “denial” as a coping strategy for dealing with diabetes ( Peek et al., 2009 ). Consequently, although our diabetes education classes included important information about diabetes complications, the curriculum focused more on risk factor reduction and the benefits of behavior change. One of the key messages of the classes has been “You can have diabetes, but diabetes doesn't have to have you.” That is, diabetes is a chronic disease that can be controlled, and the risks of complications are significantly reduced by patients' decisions and behaviors. We encouraged the sharing of success stories among diabetes patients within the class to help promote the idea, through personal testimonials, that diabetes is a condition over which patients can have control. In our interactive mobile texting program, we specifically included text messages designed to influence health beliefs; program participants had statistically significant changes in their health beliefs (e.g., perceived risk of long-term complications) at program completion ( Nundy, Mishra, et al., 2014 ).

Our program has addressed perceived barriers to behavior change, a key aspect of the health belief model. We have used multiple strategies, including active problem-solving and skills-building exercises within the patient classes (e.g., hands-on instructions about self-glucose testing, role-playing with teachers about SDM), identifying and promoting community resources for lifestyle changes (e.g., “prescriptions” for healthy food and exercise), providing social support, and sending regular text message reminders about diabetes self-care activities.

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy, or the sense of confidence in one's ability to perform an activity, is an important precursor to behavioral change ( Bandura, 1997 ). In Bandura's model, self-efficacy is built through mastery experience, social persuasions, physiological factors, and social modeling ( Skaff, Mullan, Fisher, & Chesla, 2003 ; Walker, Mertz, Kalten, & Flynn, 2003 ). In mastery experience , small successes raise self-efficacy. That is, individuals are more likely to believe they can do something continually if they have seen for themselves that they can do it at least once. A major goal of our overall project is to provide opportunities for small success in diabetes self-care and management through experiential learning. For example, in our diabetes classes, participants practice reading food labels, role-play ordering food from local restaurant menus, participate in chair-based exercises to jazz music, and role-play asking their physicians questions about recommended medications. We provide real-world opportunities for mastery experience through our guided shopping tours (where people practice reading food labels and shopping for healthy food options on budget), cooking demonstrations and community cook-off events, and “Ask the Doctor” opportunities at community venues, where community residents can engage physicians on our team and ask general questions about health/health care.

Social persuasions are defined as the encouragements or discouragements that affect an individual's self-efficacy. In the diabetes classes, we created an environment in which participants' behavior changes (e.g., beginning a physical activity regimen, discussing concerns about medication side effects with physicians at a prior clinic visit) and health outcomes (e.g., reduced HbA1c values, weight loss) were celebrated by the entire group. Class participants wanted to “make their teammates proud” of them and looked forward to sharing small victories during the class. Participants in the mobile texting program described the desire to “not let down” the text manager in aspects of their diabetes self-care and appreciated receiving positive feedback texts (e.g., “Great job!”) when they reported medication adherence.

Because hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia frequently cause physical symptoms, physiological factors played an important role in building self-efficacy. As patients in the classes reported fewer symptoms (e.g., fatigue, polyuria, blurry vision, palpitations, diaphoresis) related to unregulated glucose, it reinforced the positive behavioral changes they were making regarding their diet, physical activity, and treatment adherence. The relationship between symptoms and diabetes control was underscored for patients during the weekly reviews of blood glucose logbooks and discussions of diabetes-related symptoms and behavior modifications.

Social modeling has been a key strategy used by our team to influence the behavior of persons with diabetes. We have provided multiple opportunities for people to meet and learn from others who were living healthy lives because of the personal decisions and behaviors they made about their diabetes management. We celebrate graduates from our diabetes classes who have seen improvements in their diabetes, blood pressure, lipids, and/or weight. Some former class participants have served as peer mentors for patients struggling with their diabetes management, have been tour guides at the Farmer's Market and SAL, and work with our team at community outreach events (e.g., health fairs). We have worked closely with celebrity chefs, several of whom have diabetes or family members with the disease, who bring personal testimony to the real possibility of controlling diabetes with lifestyle changes. Thus, our team has sought to enhance the self-efficacy of our participants in performing diabetes-related health behaviors. In both the patient classes and the mobile texting program, statistically significant improvements in diabetes self-efficacy were noted among participants.

Theory of Planned Behavior

According to the theory of planned behavior (TPB), individual behavior is determined by a person's intention to perform it and by perceived control (self-efficacy) over performing the behavior ( Ajzen, 1991 ). A person's intention is determined by the weighted relative importance of the behavioral attitudes (positive or negative feelings about performing a behavior that reflect the summation of behavioral beliefs ) and the subjective norms (perceived social pressure to perform a behavior that reflects a summation of the normative beliefs ; Ajzen, 1991 ). That is, the TPB posits that behavior change is influenced by an individual's attitudes, perceived social norms, intention to perform the behavior, and perceived control over the process to change the behavior. We sought to influence each of the elements in the TPB model to promote behavior change among our patients with diabetes, many of which conceptually overlap with the health belief model and Bandura's (1997) self-efficacy model. As described earlier, our team has sought to modify beliefs and attitudes about diabetes-related health behaviors and increase patients' self-efficacy at successfully implementing behavioral changes.

In addition, we have tried to modify participants' subjective norms and normative beliefs about diabetes self-care: that is, what people believe is “normal behavior” for persons with diabetes and what they feel under social pressure to do regarding their diabetes care. We have largely accomplished this goal through the “social modeling” described above, but we have also used large media campaigns, involving television (e.g., annual 13-week series on the cable access network that takes live call-ins, interviews with local news stations), radio (e.g., regular interviews with several key African American radio stations), print media (e.g., community newspapers, major city newspapers), and social media, to influence subjective norms within the community.

Family, Friends, Small Groups

Support from friends, family members, and peers can help patients with diabetes modify their behaviors and achieve better health outcomes ( Peek, Harmon, et al., 2012 ); Samuel-Hodge et al., 2000 ; Trento et al., 2001 ). We purposely encouraged class participants to bring family members and/or friends (“whoever helps you manage your diabetes”) to the classes and facilitated the development of a family-like atmosphere within the classes themselves. Participants reported that the strong social bonds formed with their classmates, as well as the teachers, were a motivator for class retention and a facilitator of behavior change ( Goddu, Raffel, & Peek, 2012 ; Raffel, Goddu, & Peek, 2012 ).

Social Support

Social support has also been shown to have positive associations with diabetes behaviors and outcomes (Peek, Harmon, et al., 2012b; Samuel-Hodge et al., 2000 ; Trento et al., 2001 ). In Barrera's model, there are three types of social support: perceived support, enacted support, and social integration ( Cohen, Shmukler, Ullman, Rivera, & Walker, 2010 ). Perceived support is a person's subjective judgment that others will offer or have offered help. Enacted support includes specific supportive actions offered by others during times of need. Social integration is the extent to which a recipient is connected within a social network. We designed the diabetes education classes with the goal of implementing all three of these aspects of social support. We wanted participants to feel supported, both interpersonally and in tangible ways, throughout the class. We introduced the class as a “second family” and established a cultural expectation of emotional support throughout each session. Teachers were available before and after classes to provide individual assistance (e.g., rereviewing educational concepts), and participants used that time to provide social support to each other as well. During the classes, participants received glucometers and other tools to assist with diabetes self-care (e.g., measuring cups, pedometers, diabetes socks), real-time assistance and referrals to address pressing health issues (e.g., mental health counselors, urgent care visits), and other tangible means of support. Participants in the class were also socially integrated with each other; they would communicate outside of class, referred to each other as “teammates” and “family,” and relied on one another during class sessions.

We were able to leverage this social integration to facilitate behavioral change, particularly in the utilization of community-based resources that our research team collaboratively developed. Class participants reported being more comfortable using a new resource for the first time with the “warm hand-off” provided by trusted peers, class teachers, and other members of the intervention team (e.g., clinic staff, project managers). Class participants have participated in the K.L.E.O. Food Pantry, Diabetes Cook-Off, Museum of Science and Industry walking program, and the CFPP; they have used Food Rx at both the 61st Street Farmer's Market and at Walgreens locations and have joined local fitness facilities together using the Chicago Park District Exercise Rx distributed by our health care providers; and class graduates have led tours of the Farmer's Market and SAL grocery store and helped our team staff at health fairs and other community events (see Figure 1 ).

NOTE: Clockwise from upper right: K.L.E.O. Food Pantry participant; community leaders of Farmer's Market tours (including a patient class graduate), along with project staffer and state congressman; patient class graduate as a semifinalist in the 2012 Diabetes Cook-Off; Save-A-Lot grocery store tour being led by a dietician/certified diabetes educator; patient class graduate at the Farmer's Market.

Interestingly, participants in the mobile texting program reported statistically significant improvements in daily social support for diabetes self-care and qualitatively described feeling supported by the program. ( Nundy, Mishra, et al., 2014 ). Some participants in the texting program said they benefited from the feeling that “someone” was monitoring them and that help was available if needed. Some participants described the text messaging program as a “friend” or “support group,” and many valued the daily interaction the system provided.

Organizations, Communities, Culture

Ecological model.

This model expands behavior change influences from beyond the individual and their immediate social units (e.g., peers, family) to include environmental factors such as organizations, communities, and culture ( Fisher et al., 2002 ; Sallis et al., 2008 ). Health care organizations , and the providers within these organizations, can provide the infrastructure to not only improve patient care but also support patients in making behavior changes. For example, nurse care managers have been shown to enhance social support, increase medication adherence, and facilitate the adoption of lifestyle behaviors regarding diet and physical activity ( Sherbourne, Hays, Ordway, DiMatteo, & Kravitz, 1992 ). At one of our clinic sites, a nurse practitioner serves as a care manager for high-risk diabetes patients. She also coteaches in the diabetes education classes and, as such, is able to provide a seamless transition between intensive education, behavioral modification support, and care delivery. Increasingly, health systems are using team-based care and care coordination strategies for the management of chronic diseases such as diabetes, and a central component has been patient education and support of behavior change ( Peek, Ferguson, Bergeron, Maltby, & Chin, 2014 ). Within our project, we set out to provide additional tools and skills for providers and staff in motivational interviewing, engaging patients in SDM, and providing culturally competent care. Participants in our 4-hour workshop reported increased confidence in their ability to engage patients in their care and guide them along the “stages of change” in behavioral modifications. Our project also includes a quality improvement collaborative, composed of the quality improvement teams of the six participating health centers, which is currently working to incorporate diabetes care coordinators. One of roles of the care coordinators will be to provide personalized “coaching” for behavior change and lifestyle modification. As part of our mobile texting program, we piloted the use of a patient-generated health data tool, which summarized data from patients' texts into a one-page document, among primary care physicians and endocrinologists at one of our participating clinics. Providers found it to be a helpful tool for focusing their clinic visits on specific barriers to diabetes self-care, including behavior change ( Nundy, Lu, Hogan, Mishra, & Peek, 2014 ).

The importance of the local community , and its built environment, cannot be underestimated when assessing the feasibility of patients making recommended lifestyle changes to improve their health. Numerous studies have linked food deserts, the disproportionate presence of fast food venues (vs. grocery stores), and physical activity barriers (e.g., limited availability of parks and sidewalks, high traffic areas, crime/violence) to poor dietary patterns, sedentary lifestyles, obesity, and diabetes ( Dutton, Johnson, Whitehead, Bodenlos, & Brantley, 2005 ; Krishnan, Cozier, Rosenberg, & Palmer, 2009; Mari Gallagher Research and Consulting Group, 2006 ; Seligman & Schillinger, 2010 ). Thus, identifying and leveraging community resources to facilitate the adoption of healthy lifestyles are critical to any program seeking to change health behaviors among persons with diabetes. In our program, we specifically set out to identify and collaborate with local community resources that would help our activated patients sustain the behaviors they were eager to adopt. We did so in ways that addressed some of the financial constraints to the early adoption of behaviors, when patient ambivalence may allow financial constraints to outweigh the perceived benefits. Our Food Rx came with coupons or vouchers that allowed patients to obtain free, healthy food at locations close to their home. The Exercise Rx waived the fees for 6 months associated with the use of fitness facilities within the Chicago Park District, many of which are located within Chicago's South Side. The CFPP sought to expose participants to fitness resources on the South Side, at no cost, that they may not been aware of (e.g., local churches with designated space for weight training and exercise classes, University of Chicago recreational space that is open to the community) or may not have previously visited (e.g., local YMCA). The CFPP also sought to expose people to a range of physical activity types (e.g., weight training, yoga, running, line dancing) in order to help individuals “find their passion” about a specific physical activity that they would be willing to engage in long term. People are more likely to sustain behaviors that they enjoy (vs. cognitively recognize will improve their health), and so helping diabetes patients explore physical activity options, with the support of peers and members of our intervention team, may be an important way to bridge patients to community resources and sustain behavior change.

Patients living on the South Side of Chicago are largely working-class African Americans that were part of the Great Migration (or descendants of it) from the Southern United States ( Tolnay, 2003 ) As such, we have culturally tailored much of our program to fit the needs of this population. Our patient empowerment classes were designed based on qualitative research among African American diabetes patients on the South Side of Chicago ( Peek et al., 2008 ; Peek et al., 2009 ; Peek et al., 2010 ), and in consultation with a panel of experts that included community members with diabetes. We tailored the educational content, SDM training, to a teaching style (e.g., use of narrative, or storytelling) to fit the needs of the population ( Goddu et al., 2012 ; Peek, Harman, et al., 2012 ; Raffel et al., 2012 ). Similarly, we developed a bank of over 800 text messages for our mobile technology program with the help of a certified diabetes educator, who had worked on Chicago's South Side for decades, and several African American diabetes patients ( Dick et al., 2011 ; Nundy et al., 2012 ). Our CFPP incorporates components that culturally resonate with African Americans (e.g., incorporation of line dancing and zumba classes, the use of local African American fitness celebrities, the use of a “passport” whose design includes images of African Americans engaging in physical activity). Our community cooking demonstrations use African American chefs who are able to showcase traditional African American foods prepared in healthy, diabetes-friendly ways.

Government, Policies, Large Systems