- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

Syphilis is an infection caused by bacteria. Most often, it spreads through sexual contact. The disease starts as a sore that's often painless and typically appears on the genitals, rectum or mouth. Syphilis spreads from person to person through direct contact with these sores. It also can be passed to a baby during pregnancy and childbirth and sometimes through breastfeeding.

After the infection happens, syphilis bacteria can stay in the body for many years without causing symptoms. But the infection can become active again. Without treatment, syphilis can damage the heart, brain or other organs. It can become life-threatening.

Early syphilis can be cured, sometimes with a single shot of medicine called penicillin. That's why it's key to get a health care checkup as soon as you notice any symptoms of syphilis. All pregnant people should get tested for syphilis at their first prenatal checkup too.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Primary syphilis

Primary syphilis causes painless sores (chancres) on the genitals, rectum, tongue or lips. The disease can be present with the appearance of a single chancre (shown here on a penis) or many.

Syphilis develops in stages. The symptoms vary with each stage. But the stages may overlap. And the symptoms don't always happen in the same order. You may be infected with syphilis bacteria without noticing any symptoms for years.

The first symptom of syphilis is a small sore called a chancre (SHANG-kur). The sore is often painless. It appears at the spot where the bacteria entered your body. Most people with syphilis develop only one chancre. Some people get more than one.

The chancre often forms about three weeks after you come in contact with syphilis bacteria. Many people who have syphilis don't notice the chancre. That's because it's usually painless. It also may be hidden within the vagina or rectum. The chancre heals on its own within 3 to 6 weeks.

Secondary syphilis

You may get a rash while the first chancre heals or a few weeks after it heals.

A rash caused by syphilis:

- Often is not itchy.

- May look rough, red or reddish-brown.

- Might be so faint that it's hard to see.

The rash often starts on the trunk of the body. That includes the chest, stomach area, pelvis and back. In time, it also could appear on the limbs, the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet.

Along with the rash, you may have symptoms such as:

- Wartlike sores in the mouth or genital area.

- Muscle aches.

- Sore throat.

- Tiredness, also called fatigue.

- Weight loss.

- Swollen lymph nodes.

Symptoms of secondary syphilis may go away on their own. But without treatment, they could come and go for months or years.

Latent syphilis

If you aren't treated for syphilis, the disease moves from the secondary stage to the latent stage. This also is called the hidden stage because you have no symptoms. The latent stage can last for years. Your symptoms may never come back. But without treatment, the disease might lead to major health problems, also called complications.

Tertiary syphilis

After the latent stage, up to 30% to 40% of people with syphilis who don't get treatment have complications known as tertiary syphilis. Another name for it is late syphilis.

The disease may damage the:

- Blood vessels.

- Bones and joints.

These problems may happen many years after the original, untreated infection.

Syphilis that spreads

At any stage, untreated syphilis can affect the brain, spinal cord, eyes and other body parts. This can cause serious or life-threatening health problems.

Congenital syphilis

Pregnant people who have syphilis can pass the disease to their babies. Unborn babies can become infected through the organ that provides nutrients and oxygen in the womb, called the placenta. Infection also can happen during birth.

Newborns with congenital syphilis might have no symptoms. But without fast treatment, some babies might get:

- Sores and rashes on the skin.

- A type of discolored skin and eyes, called jaundice.

- Not enough red blood cells, called anemia.

- Swollen spleen and liver.

- Sneezing or stuffed, drippy nose, called rhinitis.

- Bone changes.

Later symptoms may include deafness, teeth problems and saddle nose, a condition in which the bridge of the nose collapses.

Babies with syphilis also can be born too early. They may die in the womb before birth. Or they could die after birth.

When to see a doctor

Call a member of your health care team if you or your child has any symptoms of syphilis. These could include any unusual discharge, a sore or a rash, especially in the groin area.

Also get tested for syphilis if you:

- Have had sexual contact with someone who might have the disease.

- Have another sexually transmitted disease such as HIV .

- Are pregnant.

- Regularly have sex with more than one partner.

- Have unprotected sex, meaning sex without a condom.

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Signs and symptoms of syphilis

Vivien Williams: Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum. Dr. Stacey Rizza, an infectious diseases specialist at Mayo Clinic, says syphilis affects men and women and can present in various stages.

Stacey Rizza, M.D.: Primary syphilis causes an ulcer, and this sometimes isn't noticed because it's painless and can be inside the vagina or on the cervix…after a few weeks, two months, they can get secondary syphilis, which is a rash.

Vivien Williams: It may then progress to latent stage syphilis and, finally, the most serious stage: tertiary. Pregnant women are not immune to syphilis. Congenital syphilis can lead to miscarriage, stillbirth or infant deaths. That's why all pregnant women should be screened. Syphilis is preventable and treatable. As for prevention, Dr. Rizza recommends barrier protection during sex.

Dr. Rizza: And that's during oral sex, anal sex, vaginal sex — using condoms, dental dams and any other barrier protection.

Vivien Williams: For the Mayo Clinic News Network, I'm Vivien Williams.

More Information

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

The cause of syphilis is a bacterium called Treponema pallidum. The most common way syphilis spreads is through contact with an infected person's sore during vaginal, oral or anal sex.

The bacteria enter the body through minor cuts or scrapes in the skin or in the moist inner lining of some body parts.

Syphilis is contagious during its primary and secondary stages. Sometimes it's also contagious in the early latent period, which happens within a year of getting infected.

Less often, syphilis can spread by kissing or touching an active sore on the lips, tongue, mouth, breasts or genitals. It also can be passed to babies during pregnancy and childbirth and sometimes through breastfeeding.

Syphilis can't be spread through casual contact with objects that an infected person has touched.

So you can't catch it by using the same toilet, bathtub, clothing, eating utensils, doorknobs, swimming pools or hot tubs.

Once cured, syphilis doesn't come back on its own. But you can become infected again if you have contact with someone's syphilis sore.

Risk factors

The risk of catching syphilis is higher if you:

- Have unprotected sex.

- Have sex with more than one partner.

- Live with HIV , the virus that causes AIDS if untreated.

The chances of getting syphilis also are higher for men who have sex with men. The higher risk may be linked, in part, with less access to health care and less use of condoms among this group. Another risk factor for some people in this group includes recent sex with partners found through social media apps.

Complications

Without treatment, syphilis can lead to damage throughout the body. Syphilis also raises the risk of HIV infection and can cause problems during pregnancy. Treatment can help prevent damage. But it can't repair or reverse damage that's already happened.

Small bumps or tumors

Rarely in the late stage of syphilis, bumps called gummas can form on the skin, bones, liver or any other organ. Most often, gummas go away after treatment with medicine called antibiotics.

Neurological problems

Syphilis can cause many problems with the brain, its covering or the spinal cord. These issues include:

- Meningitis, a disease that inflames the protective layers of tissue around the brain and spinal cord.

- Confusion, personality changes or trouble focusing.

- Symptoms that mimic dementia, such as loss of memory, judgment and decision-making skills.

- Not being able to move certain body parts, called paralysis.

- Trouble getting or keeping an erection, called erectile dysfunction.

- Bladder problems.

Eye problems

Disease that spreads to the eye is called ocular syphilis. It can cause:

- Eye pain or redness.

- Vision changes.

Ear problems

Disease that spreads to the ear is called otosyphilis. Symptoms can include:

- Hearing loss.

- Ringing in the ears, called tinnitus.

- Feeling like you or the world around you is spinning, called vertigo.

Heart and blood vessel problems

These may include bulging and swelling of the aorta — the body's major artery — and other blood vessels. Syphilis also may damage heart valves.

HIV infection

Syphilis sores on the genitals raise the risk of catching or spreading HIV through sex. A syphilis sore can bleed easily. This provides an easy way for HIV to enter the bloodstream during sex.

Pregnancy and childbirth complications

If you're pregnant, you could pass syphilis to your unborn baby. Congenital syphilis greatly raises the risk of miscarriage, stillbirth or your newborn's death within a few days after birth.

There is no vaccine for syphilis. To help prevent the spread of syphilis, follow these tips:

- Have safe sex or no sex. The only certain way to avoid contact with syphilis bacteria is not to have sex. This is called abstinence. If a person is sexually active, safer sex means a long-term relationship in which you and your partner have sex only with each other, and neither of you is infected. Before you have sex with someone new, you should both get tested for syphilis and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

- Use a latex condom. Condoms can lower your risk of getting or spreading syphilis. But condoms work only if they cover an infected person's syphilis sores. Other types of birth control do not lower your risk of syphilis.

- Be careful with alcohol and stay away from street drugs. Drinking too much alcohol or taking drugs can get in the way of your judgment. Either can lead to unsafe sex.

- Do not douche. It can remove some of the healthy bacteria that's usually in the vagina. And that might raise your risk of getting STIs .

- Breastfeed with caution. Syphilis can pass from a parent to a baby during breastfeeding if sores are on one or both breasts. This can happen when the baby or pumping equipment touches a sore. To keep that from happening, pump or hand-express breastmilk from the breast with sores. Do so until the sores heal. If your pump touches a sore, get rid of the milk you just pumped.

Partner notification and preventive treatment

If tests show that you have syphilis, your sex partners need to know so that they can get tested. This includes your current partners and any others you've had over the last three months to 1 year. If they're infected, they can then get treatment.

After you learn you have syphilis, your local health department may contact you. A department employee talks with you about private ways to let your partners know that they've been exposed to syphilis. You can ask the department to do this for you without revealing your identity to your partners.

Or you can contact your partners along with a department employee or simply tell your partners yourself. This free service is called partner notification. It can help limit the spread of syphilis. The practice also steers those at risk toward counseling and the right treatment.

And since you can get syphilis more than once, partner notification lowers your risk of getting infected again.

Screening tests for pregnant people

You can be infected with syphilis and not know it. And the disease can have deadly effects on unborn babies. For this reason, health officials recommend that all pregnant people be tested for the disease.

- Syphilis — CDC detailed fact sheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/stdfact-syphilis-detailed.htm. Accessed April 27, 2023.

- Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021: Syphilis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/syphilis.htm. Accessed April 27, 2023.

- Hicks CB, et al. Syphilis: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical manifestations in patients without HIV. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed April 27, 2023.

- Syphilis. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/infectious-diseases/sexually-transmitted-diseases-stds/syphilis. Accessed April 27, 2023.

- Hicks CB, et al. Syphilis: Treatment and monitoring. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed April 27, 2023.

- Hicks CB, et al. Syphilis: Screening and diagnostic testing. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed April 27, 2023.

- Syphilis — CDC basic fact sheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/stdfact-syphilis.htm. Accessed April 27, 2023.

- Loscalzo J, et al., eds. Syphilis. In: Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 21st ed. McGraw Hill; 2022. https://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com. Accessed July 14, 2019.

- AskMayoExpert. Syphilis (adult). Mayo Clinic; 2021.

- Sexually transmitted infections. Office on Women's Health. http://womenshealth.gov/publications/our-publications/fact-sheet/sexually-transmitted-infections.html. Accessed April 27, 2023.

- Tosh PK (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. May 1, 2023.

- Cáceres CF, et al. Syphilis in men who have sex with men: advancing research and human rights. The Lancet Global Health. 2021; doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00269-2.

- How can partner services programs help me and my patients? Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/clinicians/screening/partner-notification.html. Accessed April 28, 2023.

- Penicillin allergy FAQ. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. https://www.aaaai.org/tools-for-the-public/conditions-library/allergies/penicillin-allergy-faq. Accessed April 28, 2023.

- Just diagnosed? Next steps after testing positive for gonorrhea or chlamydia. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/std/prevention/NextSteps-GonorrheaOrChlamydia.htm. Accessed May 1, 2023.

News from Mayo Clinic

- Newborns diagnosed with syphilis at alarming rates Feb. 19, 2024, 03:30 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Syphilis surge is cause for concern Feb. 03, 2024, 12:00 p.m. CDT

- Syphilis: A rising community presence Aug. 01, 2022, 04:30 p.m. CDT

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Make twice the impact

Your gift can go twice as far to advance cancer research and care!

Syphilis – CDC Basic Fact Sheet

Electron micrograph of Treponema pallidum on cultures of cotton-tail rabbit epithelium cells

A primary vulvar syphilitic chancre due to Treponema pallidum bacteria

A penile chancre located on the proximal penile shaft: primary syphilitic infection

Gummatous lesions on the dorsal surface of the left hand

Secondary syphilitic papulosquamous rash on the torso and upper body

Secondary syphilitic lesions on the face

Secondary syphilis presenting pigmented macules and papules on the skin

Secondary syphilitic lesions of vagina

This was a case of congenital syphilis resulting in the death of this newborn infant

This newborn presented with symptoms of congenital syphilis that included lesions on the soles of both feet

Interstitial keratitis

Peg-shaped, notched central incisors (Hutchinson teeth)

Osteoperiostitis of the tibia ("saber shins")

Clutton joints

Signs and symptoms of primary syphilis

Signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis, latent syphilis, signs and symptoms of tertiary syphilis.

Loss of anal and bladder sphincter control

Dorsal column loss (loss of vibration and proprioception/position sense)

Romberg sign.

Behavioral changes

Memory impairment

Altered mood

Argyll-Robertson pupils.

HIV coinfection

Primary syphilis: larger, painful multiple ulcers.

Secondary syphilis: genital ulcers more common and higher titers with rapid plasma reagin (RPR) testing and Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) testing.

Possibly more rapid progression to neurosyphilis. [ 18 ]

Serologic responses to infection may be atypical. [ 34 ]

Signs and symptoms of congenital syphilis

Identification of syphilis in the mother

Adequacy of maternal treatment

Presence of clinical, laboratory, or radiographic evidence of syphilis in the infant (testing should include paired maternal and neonatal nontreponemal serologic titers using the same test, preferably conducted at the same laboratory).

Peg-shaped central incisors, notched at the apex (Hutchinson teeth)

Eighth cranial nerve deafness

Frontal bossing of the skull

Anterior bowing of the shins (Saber shins)

Saddle nose deformity

Clutton joints (symmetric painless knee swelling).

Initial investigations for acquired syphilis

Treponemal enzyme immunoassay (EIA)

T pallidum particle agglutination assay (TPPA)

T pallidum haemagglutination assay (TPHA)

Fluorescent antibody absorption (FTA-ABS)

Immunocapture assay (ICA).

EIA: 3 weeks

TPPA: 4-6 weeks

TPHA: 4-6 weeks.

RPR: 4 weeks

VDRL: 4 weeks.

Other initial investigations for acquired syphilis

Emerging investigations, further investigations for acquired syphilis.

CSF white blood cell (WBC) count >10 cells/mm³ (10 × 10⁶ cells/L)

CSF protein >50 mg/dL (0.50 g/L)

A positive CSF VDRL test.

Initial investigations for congenital syphilis

Further investigations for congenital syphilis.

An abnormal physical exam that is consistent with congenital syphilis (e.g., nonimmune hydrops, conjugated or direct hyperbilirubinemia or cholestatic jaundice or cholestasis, hepatosplenomegaly, rhinitis, skin rash, or pseudoparalysis of an extremity) or

A serum quantitative nontreponemal serologic titer that is fourfold higher than the mother's titer (e.g., maternal titer = 1:2, neonatal titer ≥1:8 or maternal titer = 1:8, neonatal titer ≥1:32) or

A positive dark-field test or PCR of placenta, cord, lesions or body fluids, or a positive silver stain of the placenta or cord.

The mother was not treated, was inadequately treated, or has no documentation of having received treatment or

The mother was treated with erythromycin or other nonpenicillin regimen or

The mother received treatment <4 weeks before delivery.

Infants and children ages ≥1 month with reactive serologic tests for syphilis.

sexual contact with an infected person

The risk of acquiring syphilis after sex with someone with primary or secondary syphilis is between 30% and 60%. [ 17 ]

men who have sex with men (MSM)

At higher risk, particularly if they are also HIV coinfected, use illicit drugs such as methamphetamine, or have multiple, casual sexual partners. [ 21 ] [ 22 ]

In 2021, almost half (46.5%) of all reported cases of primary and secondary syphilis in the US occurred in MSM. [ 12 ]

illicit drug use

Association due to the exchange of sex for money or drugs, particularly crack cocaine. [ 23 ]

commercial sex workers

Multiple sexual partners.

A risk factor for all STIs.

Important in syphilis epidemiology. [ 21 ]

people with HIV or other STIs

Suggests unprotected sexual intercourse, which increases the risk of STIs.

All patients who have an STI should have syphilis screening, as should patients at higher risk of STIs, irrespective of where they are seen.

syphilis during pregnancy (risk for congenital syphilis)

The fetus acquires the infection from the infected mother. Inadequate treatment of maternal syphilis accounts for up to one-third of congenital syphilis cases. [ 24 ]

This may result in miscarriage, stillbirth, or neonatal death. [ 3 ]

Screening for syphilis at the first prenatal visit aims to identify and treat asymptomatic infected women, thus preventing transplacental transmission. [ 25 ] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends repeating syphilis screening at 28 weeks' gestation and at delivery for women at high risk of syphilis infection. Risk factors for syphilis infection during pregnancy include commercial sex work, a history of substance misuse, sex with multiple partners, late entry into prenatal care (i.e., first visit during the second trimester or later) or no prenatal care, unstable housing or homelessness, and imprisonment of the woman or her partner. [ 8 ]

Initially a macule, developing into a papule and then ulcerating to form a chancre. Image

Classically appears in the anogenital area 14 to 21 days after exposure (primary infection).

Usually indurated, solitary, and painless. Image

May not always be noticed by the patient and examining physician, and it heals spontaneously.

Atypically may be multiple and painful. Coinfection with genital herpes or chancroid may cause painful ulceration. HIV coinfection may be associated with multiple ulcers.

Erosions on the genitalia may also occur in secondary syphilis. Image

Moderately enlarged, rubbery regional lymphadenopathy associated with the classical syphilitic ulcer (chancre) in primary infection.

Generalized lymphadenopathy may occur with secondary syphilis.

Symmetric macular, papular, or maculopapular rash in secondary syphilis. Image

Often widespread with mucous membrane involvement. Image

May desquamate.

Usually nonitchy, over the trunk, palms, soles, and scalp.

In dark-skinned patients may cause pruritus.

May accompany a history of constitutional symptoms such as fever and malaise.

Onset is usually 6 to 12 weeks after exposure.

Up to 25% of people who have untreated secondary syphilis develop relapsing episodes of rash and fever. [ 9 ] [ 17 ]

Rash also occurs in congenital syphilis.

Such as fever, malaise, myalgia, fatigue, and arthralgia with secondary syphilis.

May be mistaken for primary HIV infection or another intercurrent viral illness.

As a result of cardiovascular syphilis (tertiary disease), which may lead to heart failure.

May also be a constitutional symptom in secondary syphilis.

A sign of early congenital syphilis (occurring <2 years of age).

Discharge may be purulent and bloody.

Usually associated with other signs of disseminated infection (rash, mucous membrane ulceration).

May develop in secondary syphilis.

Slightly raised, or flat, round, or oval papules covered by gray exudates.

A sign of secondary syphilis.

May be present within moist areas of the perineum.

May be mistaken for genital warts.

Possible signs of neurosyphilis. [ 66 ]

Brain involvement in tertiary syphilis causes a range of syndromes, including cognitive and motor impairment, which are sometimes grouped under the broad term "general paresis".

Visual impairment may be a presenting feature of syphilitic iritis or uveitis, occurring in secondary infection.

Bilaterally small, irregular pupils, which do not constrict when exposed to bright light, but do constrict in response to accommodation.

A feature of tabes dorsalis occurring in tertiary syphilis.

Dorsal column loss is a feature of tabes dorsalis, occurring in tertiary syphilis.

Possible sign of cardiovascular syphilis (tertiary disease).

Diastolic murmur at the left sternal edge indicates aortic regurgitation, which may be due to aortitis caused by cardiovascular syphilis.

A sign of gummatous syphilis (also known as benign tertiary syphilis).

Affects skin and visceral organs.

The destructive gumma may gradually replace normal tissue.

Signs of congenital syphilis. [ 67 ]

Signs of early congenital syphilis.

May occur in early congenital syphilis (occurring <2 years of age).

This rash may be similar to the rash of secondary syphilis in adults. It may also be more widespread, bullous or papulonecrotic, or desquamating.

Initially the rash may be a vesicular rash with small blisters appearing on the palms and plantar surfaces of the feet. An erythematous or maculopapular rash, which is often copper-colored, may subsequently appear on the face, palms, and plantar surfaces of the feet. The rash may also affect the mouth, genitalia, and anus. Images

A sign of late congenital syphilis (occurring >2 years of age).

Due to neonatal osteochondritis in congenital syphilis. Image

Including frontal bossing, high cranium, and saddle nose.

Hutchinson teeth (peg-shaped incisors, notched at the apex), mulberry molars dome-shaped with small cusps at the apex.

Poorly mineralized teeth. Image

Necrotizing funisitis (inflammation of the umbilical cord) is virtually diagnostic of congenital syphilis. Usually found in preterm infants who are stillborn, or die within a few weeks of birth.

The umbilical cord has a specific appearance known as the "barberpole" cord as a result of inflammation of the matrix of the umbilical cord. [ 37 ]

May coexist with genital ulceration.

Occurs in both primary and secondary infection.

In secondary infection the mouth ulcers (snail track ulcers) will usually be coexistent with other symptoms or signs, such as rash, fever.

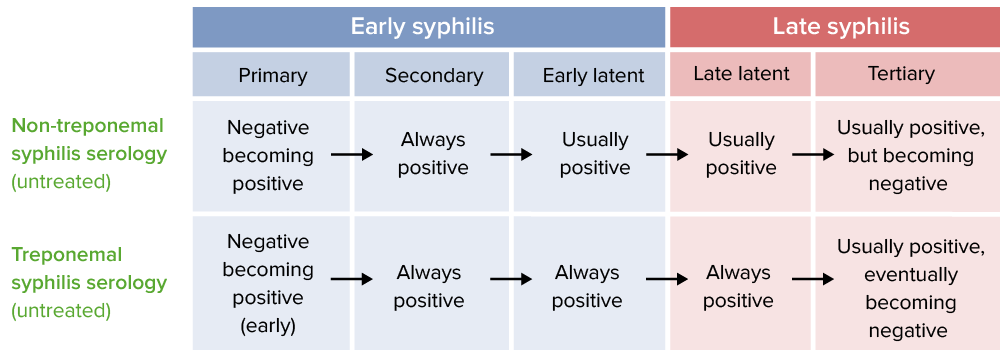

Latent syphilis is defined as positive serology in the absence of clinical features of syphilis.

Ulcers in primary syphilis may not be noticed by the patient and examining physician.

Possible sign of tertiary disease with brain involvement.

May indicate neurologic involvement.

May occur with neck stiffness.

May be a presenting feature of syphilitic iritis or uveitis, occurring in secondary infection.

The eighth cranial nerve is the most commonly affected cranial nerve in neurosyphilis.

Hearing loss may be a symptom and a sign of both early and late neurosyphilis.

Deafness may also occur as a result of late congenital syphilis (occurring >2 years of age).

Suggest neurologic involvement.

Occurs with nephrotic syndrome that may develop due to vasculitis in secondary syphilis.

May indicate hepatitis, due to vasculitis in secondary syphilis.

Sign of neurosyphilis.

Usually affecting lower limbs.

May occur in all forms of neurosyphilis.

As a result of cardiovascular syphilis (tertiary disease).

Aortic aneurysm caused by syphilis almost always affects the thoracic aorta (usually the ascending part of the thoracic aorta), resulting in heart failure.

Lesions in gummatous syphilis may cause organomegaly, and become infiltrative or destructive.

May occur as a result of gummatous syphilis.

May include a wide range of problems such as seizures, meningitis, obstructive hydrocephalus, and cranial nerve palsies.

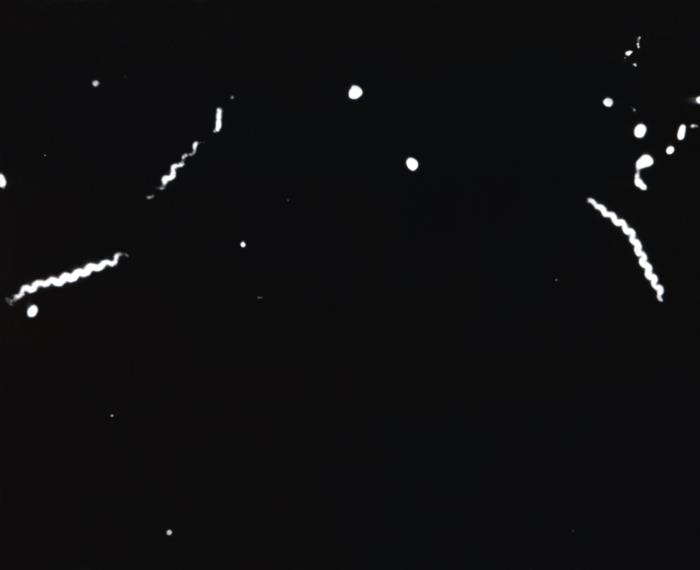

coiled spirochete bacterium with a corkscrew appearance and motility

Performed to identify Treponema pallidum .

Can provide a definitive diagnosis of syphilis, but is not usually available outside specialist settings.

The lesion is cleansed and abraded with a gauze pad until serous exudates appear, which are collected onto a glass slide for microscopic analysis.

A single negative result does not exclude infection; ideally 3 negative examinations on different days are required.

Primary syphilis: sensitivity of dark-field microscopy is 74% to 86%, specificity is 85% to 100%. [ 5 ] [ 6 ] [ 39 ]

Secondary syphilis: dark-field microscopy may be positive from ulcerative anogenital lesions.

Gummata in tertiary syphilis have few, if any, identifiable T pallidum organisms.

Congenital syphilis: test suspicious lesions (e.g., bullous rash or nasal discharge). [ 8 ]

A treponemal serology test.

A patient with a positive treponemal test result will remain positive for life. Therefore, a positive result alone cannot distinguish between an active infection or past (treated) infection.

The most common approach is to use a treponemal test as the initial serologic test, followed by a nontreponemal test to confirm diagnosis and provide evidence of active disease or reinfection (i.e., a "reverse sequence screening algorithm"). [ 40 ]

False-positive results may occur with other nonsexually transmitted treponemal infection (e.g., yaws, pinta, bejel).

False-negative results may occur in incubating and early primary syphilis. It usually takes 3 weeks for an EIA IgG/IgM test to become positive after infection with Treponema pallidum .

EIA is the test generally used for screening. [ 10 ]

Primary syphilis: EIA sensitivity 82% to 100%, and specificity 97% to 100%. [ 68 ]

Secondary syphilis: EIA sensitivity is 100%. [ 68 ]

Late latent syphilis: EIA sensitivity is 98% to 100%. [ 68 ]

A patient with a positive treponemal test result will remain positive for life. Therefore, a positive result alone cannot distinguish between an active or past (treated) infection.

Primary syphilis: TPPA sensitivity is 85% to 100%, and specificity is 98% to 100%. [ 69 ] [ 70 ]

Secondary and late latent syphilis: TPPA sensitivity is 98% to 100%. [ 70 ]

FTA-ABS is used less often than TPHA and TPPA because it is less specific.

LIA serologic tests (e.g., INNO-LIA syphilis test) can be used to confirm syphilis infection following initial serologic treponemal testing. A single LIA test can confirm infection, making it more convenient than traditional methods of serologic confirmation (which usually require multiple assays). Studies evaluating the performance of LIA tests for syphilis infection have demonstrated higher sensitivity and specificity compared with FTA-ABS and TPHA serology tests. [ 49 ] [ 50 ]

A nontreponemal serology test.

Provides a quantitative measure of disease activity and can be used to monitor treatment response (RPR titers decrease or become nonreactive with effective treatment).

Despite adequate treatment, some patients maintain a persisting low level positive antibody titer (known as a serofast reaction). [ 44 ]

False positives may occur due to the presence of a variety of medical conditions (e.g., pregnancy, autoimmune disorders, and infections).

A false-negative test may occasionally occur in an undiluted specimen (the prozone phenomenon).

Primary syphilis: RPR sensitivity is 70% to 73%. [ 5 ] [ 71 ]

Secondary syphilis: RPR sensitivity is 100%. [ 71 ]

Preferred test over the serum Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test.

Congenital syphilis: include paired maternal and neonatal nontreponemal serologic titers using the same test, preferably conducted at the same laboratory. [ 8 ]

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued a warning of false-positive RPR results linked to COVID-19 vaccination. RPR false reactivity has been observed in some individuals for at least 5 months following the vaccine. The issue has been identified in the Bio-Rad BioPlex 2200 Syphilis Total & RPR test kit. It is not yet known if other RPR tests are affected similarly. For healthcare professionals who use the Bio-Rad BioPlex 2200 Syphilis Total & RPR test kit, the FDA recommends performing confirmatory testing for all reactive results. In patients previously treated for syphilis who received a COVID-19 vaccine, and whose clinical presentation and epidemiologic considerations do not support syphilis reinfection, reactive RPR results obtained from the BioPlex 2200 Syphilis Total & RPR test kit should be confirmed using an RPR test from a different manufacturer. [ 45 ]

Provides a quantitative measure of disease activity and can be used to monitor treatment response (VDRL titers decrease or become nonreactive with effective treatment).

Primary syphilis: VDRL sensitivity is 44% to 76%. [ 5 ]

VDRL is positive in 77% of cases of late latent syphilis. [ 5 ]

VDRL sensitivity in secondary syphilis is 100%. [ 71 ]

WBC count >10 cells/mm³; CSF protein >50 mg/dL; CSF VDRL positive; CSF TPHA/TPPA/FTA-ABS positive

Indicated for any patient with clinical evidence of neurologic involvement (e.g., cranial nerve dysfunction, meningitis, stroke, acute or chronic altered mental status, or loss of vibration sense).

Indicated if syphilis of unknown duration exists in the presence of HIV coinfection.

Indicated in any child with congenital syphilis and neurologic symptoms or signs. [ 8 ]

An elevated CSF WBC count and positive CSF Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) suggests neurologic involvement. [ 31 ]

Some patients with neurosyphilis have an isolated elevated CSF WBC count and negative rapid plasma reagin/VDRL.

Neurosyphilis is unlikely at CSF Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay (TPHA)/ T pallidum particle agglutination assay (TPPA) titers <1:320.

A nonreactive CSF-TPHA test result usually excludes neurosyphilis.

possible widened thoracic aorta, aortic calcification

May detect possible thoracic aortic aneurysm or aortic calcification.

Required in people with symptoms or signs of aortic regurgitation, heart failure, or aortic aneurysm.

may show evidence of heart failure, aortic regurgitation, or thoracic aortic aneurysm

Required if cardiovascular syphilis is strongly suspected (e.g., a patient has symptoms or signs of aortic regurgitation, heart failure, or aortic aneurysm).

usually normal

Performed before lumbar puncture to exclude elevated intracranial pressure, to ensure that a lumbar puncture procedure will be safe.

Elevated intracranial pressure is rarely caused by syphilis itself.

positive or negative

All patients with syphilis should be tested for HIV.

In geographic areas in which the prevalence of HIV is high, patients who have syphilis should be retested for HIV after 3 months, even if the first HIV test result is negative, and be offered HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). [ 8 ]

All infants and children at risk for congenital syphilis should be tested for HIV. [ 8 ]

may show hepatomegaly, ascites, hydrops fetalis, intrauterine growth retardation

Should be performed on all pregnant women with syphilis or suspected of having syphilis.

Presence of fetal or placental syphilis indicates a greater risk of treatment failure for congenital syphilis. [ 65 ]

may show anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, possible neutrophilia

Performed in infants with possible congenital syphilis.

may demonstrate osteochondritis

May be indicated in infants with suspected congenital syphilis. [ 8 ]

Performed if osteochondritis suspected.

aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase may be elevated

Performed if clinical findings suggestive of liver involvement (e.g., hepatomegaly).

may detect deafness

Performed if clinically indicated.

may detect hearing deficit

Neurosyphilis may involve cranial nerves (particularly the 8th cranial nerve).

osseous lesions

Might aid diagnosis of congenital syphilis in stillborn infants. [ 8 ]

T pallidum PCR has been shown to have moderate sensitivity (70% to 80%) and high specificity >90% in the diagnosis of primary or secondary syphilis, when compared with adequate reference tests (e.g., serology, dark-field microscopy). [ 51 ]

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers PCR testing a valid method for diagnosing primary, secondary, and congenital syphilis, and its use is likely to increase. [ 8 ] [ 52 ]

positive; however, a positive result for treponemal antibodies alone does not distinguish between current, past, or treated infection

POC syphilis testing has been assessed in the setting of high-risk regions, where rapid and early diagnosis may be more important than accuracy. Several clinical trials have shown promise and POC testing has been recommended as part of the Pan American Health Organization strategy to diagnose and treat syphilis. [ 53 ] [ 54 ]

Genital herpes

Differentiating Signs/Symptoms

There may be a history of fever, genital blisters or sores, and lymphadenopathy with first episode herpes simplex.

The patient may describe previous episodes of genital ulceration.

On physical exam there are typically multiple, painful vesicular or ulcerative lesions on or around the genitals or rectum.

Differentiating Tests

If lesions are present, clinical diagnosis should be confirmed by swabbing lesions for herpes simplex virus (HSV) culture or HSV polymerase chain reaction (PCR). [ 8 ]

Because of the higher sensitivity of PCR, this is the preferred test when available. [ 8 ]

Glycoprotein G-based type-specific serology may be indicated in certain patient groups and can differentiate between infection with HSV-1 and HSV-2. [ 8 ]

Characterized by painful genital ulcers and painful inguinal lymphadenopathy. Lesions of primary syphilis are typically not painful.

Usually occurs in discrete outbreaks.

On physical exam there may be an erythematous papule, pustule, or painful ulcer, as well as painful unilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy (bubo formation), which may rupture.

Haemophilus ducreyi is identified on specialist culture medium, which is not widely commercially available and has a sensitivity of <80%. [ 72 ]

Polymerase chain reaction testing is up to 100% sensitive but is not universally approved. [ 72 ] [ 73 ]

Therefore a positive diagnosis of chancroid is suggested by the presence of one or more painful genital ulcers with no evidence of syphilis or herpes simplex virus. [ 8 ] Regional lymphadenopathy is also confirmatory, if present. [ 8 ]

Primary HIV infection

Not preceded by genital ulceration.

However, genital ulceration may be present at the same time as primary HIV infection and the rash associated with the ulceration.

Laboratory tests positive for HIV, including antigen (P24 antigen) tests.

Other acute viral exanthems

Laboratory tests positive for specific virus.

Skin lesions are usually pruritic.

Typical distribution: interdigital, wrists, nipples, ankles, buttocks.

Diagnosis is usually clinical, but skin scrapings and microscopy for Sarcoptes scabiei may be performed.

Skin lesions are usually absent on palms and plantar aspects of feet.

Not associated with signs of systemic infection.

Diagnosis is usually clinical.

Skin biopsy can be undertaken to confirm diagnosis.

Lichen planus

Skin lesions are usually absent on palms and plantar aspect of feet.

Genital warts

Pink lumps, in genital and/or perianal skin and mucous membranes. Not necessarily confined to opposing membranes.

Not associated with other signs of secondary syphilis (rash, constitutional symptoms, generalized lymphadenopathy).

Exclusion of syphilis (negative syphilis serology).

Alzheimer dementia

Progressive dementia.

No specific differentiating symptoms and signs compared with neurosyphilis.

Less likely to have a history of possible signs and symptoms of earlier stages of syphilis infection.

Vascular dementia

Multi-infarct dementia often associated with other evidence of arteriopathy.

Syphilis infection is often asymptomatic but highly transmissible

If untreated, it causes in-utero mortality and considerable morbidity many years after initial infection

Treatment of syphilis in the early stage of infection is curative and aims to halt disease progression and eliminate further transmission of infection

Syphilis is an important facilitator of HIV transmission.

Asymptomatic patients who are at risk of syphilis infection [ 1 ] [ 74 ]

Pregnant women [ 8 ] [ 29 ] [ 62 ] [ 63 ] [ 75 ]

Blood donors. [ 76 ]

Screening tests

Screening in sti clinic, prenatal screening, screening low-risk asymptomatic population, screening for hiv and other stis, treatment approach, without neurosyphilis, neurosyphilis, infection in pregnancy, coinfection with hiv, congenital syphilis.

Presence of clinical, laboratory, or radiographic evidence of syphilis in the infant (testing should include paired maternal and neonatal non-treponemal serological titres using the same test, preferably conducted at the same laboratory).

Potential adverse effects of therapy

Primary Options

penicillin G benzathine

2.4 million units intramuscularly as a single dose

Secondary Options

100 mg orally twice daily for 14 days

Empiric therapy may be considered in those with suspected early infection (a rash or ulceration) before results of serology are available. Empiric therapy may be appropriate if there are concerns regarding re-attendance. The benefits of empiric therapy (prompt therapy) and risks (potentially unnecessary treatment) should be discussed with the patient.

Intramuscular benzathine penicillin G as a single dose is given. If the patient is allergic to penicillin and is not pregnant, oral doxycycline may be offered.

Sexual contacts of patients with confirmed syphilis should be screened and offered presumptive treatment if follow-up may be problematic.

intramuscular benzathine penicillin G

primary/secondary/early latent syphilis (nonpregnant): 2.4 million units intramuscularly as a single dose; primary/secondary/early latent syphilis (pregnant): 2.4 million units intramuscularly as a single dose, may repeat in 1 week; late-latent/tertiary syphilis with normal cerebrospinal fluid examination: 2.4 million units intramuscularly once weekly for 3 weeks

The first-line treatment for primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis (without neurosyphilis) is intramuscular benzathine penicillin G as a single dose. [ 8 ] Note that the dose may be split and administered at two discrete injection sites.

The first-line treatment of late latent and tertiary (gummatous, cardiovascular, psychiatric manifestations, late neurosyphilis) syphilis with normal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination is intramuscular benzathine penicillin G (once weekly for 3 weeks).

All patients who have tertiary syphilis should undergo cerebrospinal fluid examination before treatment is started. Patients with abnormal CSF findings should be treated with a neurosyphilis regimen. [ 8 ]

Pregnant women should receive penicillin-based treatment according to their stage of syphilis. For pregnant women with primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis, certain evidence suggests that administering two injections of intramuscular benzathine penicillin G, rather than one, can help prevent congenital syphilis. Pregnant women with late latent or tertiary syphilis with normal CSF examination should receive three injections of intramuscular benzathine penicillin G, as per the guidance for nonpregnant individuals. [ 8 ]

Most clinicians treat HIV-positive and HIV-negative individuals with the same penicillin regimens, according to the stage of syphilis. [ 8 ]

Antibiotic therapy for cardiovascular syphilis does not reverse cardiovascular disease, which may continue to progress after treatment. Discussion with a cardiologist is advised.

40-60 mg orally once daily for 3 days; start 24 hours before penicillin

Corticosteroid therapy may be considered to minimize the risk of Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in nonpregnant patients with neurosyphilis. [ 10 ] However, evidence of effectiveness is unclear and it is not routinely recommended in the US.

Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction is an acute febrile illness that can occur within the first 24 hours after initiation of antibiotic treatment for syphilis. Symptoms include acute fever, headache, and myalgia, usually occurring in patients with early syphilis. [ 8 ]

oral doxycycline

100 mg orally twice daily for 14 days (primary/secondary/early latent syphilis) or 28 days (late latent/tertiary syphilis with normal cerebrospinal fluid examination)

If the patient is allergic to penicillin, the first-line treatment in nonpregnant patients is oral doxycycline.

Adherence and patient compliance may influence treatment outcome if oral therapy is administered.

Patients who are allergic to penicillin, with primary or secondary syphilis and HIV coinfection, should receive antibiotic therapy as recommended for penicillin-allergic, HIV-negative patients. [ 8 ]

40-60 mg orally once daily for 3 days; start 24 hours before doxycycline

Corticosteroid therapy may be considered to minimize the risk of Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in nonpregnant patients with neurosyphilis. [ 10 ] However, evidence of effectiveness is unclear and it is not routinely recommended in the US.

desensitization

Penicillin desensitization is recommended for all patients with penicillin hypersensitivity in pregnancy. The evidence for the use of nonpenicillin regimens is relatively weak. [ 8 ]

Penicillin allergy skin testing identifies patients at high risk for penicillin reactions. Skin reagents used should include major and minor allergens. [ 97 ] Those who are skin-test negative can receive penicillin therapy. However, some clinicians perform desensitization without skin testing, particularly if the skin reagents for both minor and major determinants of penicillin allergy are not available.

Acute desensitization can be performed in patients who have a positive skin test to one of the penicillin determinants, and should be performed in a hospital setting. Oral or intravenous desensitization can be performed, and is usually completed in 4 hours, following which the first dose of penicillin is administered. [ 98 ]

postdesensitization intramuscular benzathine penicillin G

primary/secondary/early latent syphilis: 2.4 million units intramuscularly as a single dose, may repeat in 1 week; late-latent/tertiary syphilis with normal cerebrospinal fluid examination: 2.4 million units intramuscularly once weekly for 3 weeks

Desensitization is usually completed in 4 hours, following which the first dose of penicillin is administered. [ 98 ]

Pregnant women should receive penicillin-based treatment according to their stage of syphilis. For pregnant women with primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis, certain evidence suggests that administering two injections of intramuscular benzathine penicillin G, rather than one, can help prevent congenital syphilis. Pregnant women with late latent or tertiary syphilis with normal cerebrospinal fluid examination should receive three injections of intramuscular benzathine penicillin G, as per the guidance for nonpregnant individuals. [ 8 ]

adults with neurosyphilis

intravenous aqueous penicillin G

penicillin G sodium

18-24 million units/day intravenously given in divided doses every 4 hours (or by continuous infusion) for 10-14 days

Central nervous system involvement can occur at any stage of syphilis and can range from asymptomatic meningeal involvement to dementia and sensory neuropathy. [ 18 ] First-line treatment for neurosyphilis is intravenous aqueous penicillin G. [ 8 ]

Pregnant women should receive penicillin-based treatment according to their stage of syphilis.

Most clinicians treat HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients with the same penicillin regimens, according to the stage of syphilis. [ 8 ]

subsequent intramuscular benzathine penicillin G

2.4 million units intramuscularly once weekly for 1-3 weeks

Some specialists administer benzathine penicillin G once weekly for up to 3 weeks after the intravenous aqueous penicillin G regimen for neurosyphilis has been completed.

This ensures the duration of treatment is comparable with that of late syphilis in the absence of neurosyphilis. [ 8 ]

intramuscular procaine penicillin G plus oral probenecid

penicillin G procaine

2.4 million units intramuscularly once daily for 10-14 days

500 mg orally four times daily for 10-14 days

Second-line treatment for neurosyphilis is intramuscular procaine penicillin G plus oral probenecid.

Most clinicians treat HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients with the same penicillin regimens according to the stage of syphilis.

Pregnant women should receive penicillin-based treatment according to their stage of syphilis. [ 8 ]

with penicillin allergy

Penicillin desensitization is recommended for all patients with neurosyphilis who have penicillin hypersensitivity. The evidence for the use of nonpenicillin regimens is relatively weak. [ 8 ]

postdesensitization penicillin G

subsequent postdesensitization intramuscular benzathine penicillin G

Some specialists administer benzathine penicillin G once weekly for up to 3 weeks after the treatment regimen for neurosyphilis has been completed (only if first-line intravenous therapy was chosen as the initial therapy).

high-dose oral doxycycline

200 mg orally twice daily for 28 days

The evidence for the use of nonpenicillin regimens is relatively weak. However, high-dose doxycycline is used by some clinicians in this situation. [ 7 ] [ 18 ]

congenital syphilis

neonate: confirmed proven or highly probable congenital syphilis

intravenous aqueous penicillin G or intramuscular procaine penicillin G

100,000 to 150,000 units/kg/day intravenously, administered as 50,000 units/kg/dose every 12 hours during the first 7 days of life and then every 8 hours thereafter for a total of 10 days

50,000 units/kg intramuscularly once daily for 10 days

All neonates born to mothers who have reactive nontreponemal and treponemal tests results should be evaluated with a quantitative nontreponemal serologic test (rapid plasma reagin tests [RPR] or Venereal Disease Research Laboratory [VDRL]) performed on the neonate's serum. The nontreponemal test performed on the neonate should be the same type of nontreponemal test performed on the mother. [ 8 ]

Confirmed proven or highly probable syphilis includes any neonate with: an abnormal physical exam that is consistent with congenital syphilis (e.g., nonimmune hydrops, conjugated or direct hyperbilirubinemia or cholestatic jaundice or cholestasis, hepatosplenomegaly, rhinitis, skin rash, or pseudoparalysis of an extremity); a serum quantitative nontreponemal serologic titer that is fourfold (or greater) higher than the mother's titer at delivery (e.g., maternal titer = 1:2, neonatal titer ≥1:8 or maternal titer = 1:8, neonatal titer ≥1:32); or a positive darkfield test or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of placenta, cord, lesions, or body fluids or a positive silver stain of the placenta or cord. [ 8 ]

First-line treatment of confirmed proven or highly probable congenital syphilis is intravenous aqueous penicillin G or intramuscular procaine penicillin G. [ 8 ] [ 100 ]

Discussion with an obstetric specialist and neonatologist is recommended. Subsequently, close clinical and serologic follow-up by a pediatric specialist is recommended.

Neonates with reactive nontreponemal tests should be followed up to ensure that the nontreponemal test returns to negative. [ 8 ]

Neonates with a penicillin allergy or those who develop an allergic reaction presumed secondary to penicillin should be desensitized and treated with penicillin. [ 8 ] The evidence for the use of nonpenicillin regimens is relatively weak.

Skin testing is not possible in neonates with congenital syphilis as the procedure has not been standardized in this age group. [ 8 ]

neonate: possible congenital syphilis

intravenous aqueous penicillin G or intramuscular procaine penicillin G or intramuscular benzathine penicillin G

50,000 units/kg intramuscularly as a single dose

All neonates born to mothers who have reactive nontreponemal and treponemal test results should be evaluated with a quantitative nontreponemal serologic test (rapid plasma reagin [RPR] or Venereal Disease Research Laboratory [VDRL]) performed on the neonate's serum. The nontreponemal test performed on the neonate should be the same type of nontreponemal test performed on the mother.

Possible congenital syphilis includes any neonate who has a normal physical exam and a serum quantitative nontreponemal serologic titer equal to or less than fourfold of the maternal titer at delivery (e.g., maternal titer = 1:8, neonatal titer ≤1:16) and one of the following: the mother was not treated, was inadequately treated, or has no documentation of having received treatment; the mother was treated with erythromycin or a regimen other than those recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (i.e., a nonpenicillin G regimen); the mother received the recommended regimen but treatment was initiated <30 days before delivery. [ 8 ]

Treatment of possible congenital syphilis is intravenous aqueous penicillin G, intramuscular procaine penicillin G, or intramuscular benzathine penicillin G. [ 8 ] [ 100 ]

Single-dose benzathine penicillin G may be used if follow up is certain and the following investigations are normal: cerebrospinal fluid analysis for VDRL test, cell count, and protein; complete blood count including differential and platelet count; and long-bone radiographs. [ 8 ] Single-dose benzathine penicillin G may also be considered if the risk of untreated maternal syphilis is considered low and the neonate's nontreponemal test is nonreactive. If the mother had untreated early syphilis at the time of delivery, the neonate is at increased risk for congenital syphilis and the 10-day course of aqueous penicillin G should be considered, even if investigations are normal, nontreponemal test is nonreactive, and follow-up is assured. [ 8 ]

neonate: congenital syphilis less likely

Congenital syphilis is less likely in any neonate who has a normal physical exam and a serum quantitative nontreponemal serologic titer equal or less than fourfold of the maternal titer at delivery (e.g., maternal titer = 1:8, neonatal titer ≤1:16) and both of the following are true: the mother was treated during pregnancy, treatment was appropriate for the infection stage, and the treatment regimen was initiated ≥30 days before delivery; the mother has no evidence of reinfection or relapse. [ 8 ]

Recommended treatment is with intramuscular benzathine penicillin G. [ 8 ]

If the mother's nontreponemal titers decreased at least fourfold after therapy for early syphilis, or remained stable for low-titer, latent syphilis (e.g., VDRL test <1:2 or RPR <1:4), an alternative approach is to provide close serologic follow-up every 2-3 months for 6 months. [ 8 ]

neonate: congenital syphilis unlikely

observation

Congenital syphilis is unlikely if the neonate has a normal physical exam and a serum quantitative nontreponemal serologic titer equal to or less than fourfold of the maternal titer at delivery and both of the following are true: the mother's treatment was adequate before pregnancy; and the mother's nontreponemal serologic titer remained low and stable (i.e., serofast) before and during pregnancy and at delivery (e.g., VDRL test ≤1:2 or RPR ≤1:4). [ 8 ]

No treatment is required. However, neonates with reactive nontreponemal tests should be followed up to ensure that the nontreponemal test returns to negative. [ 8 ]

Intramuscular benzathine penicillin G may be considered, particularly if the neonate has a reactive nontreponemal test and follow up is not certain. [ 8 ]

infant or child

intravenous aqueous penicillin G or intramuscular benzathine penicillin G

200,000 to 300,000 units/kg/day intravenously, administered as 50,000 units/kg/dose every 4-6 hours for 10 days

50,000 units/kg intramuscularly once weekly for up to 3 weeks, maximum 2.4 million units/dose

Infants and children ages ≥1 month who have reactive serologic tests for syphilis (e.g., serum rapid plasma reagin reactive, serum treponemal enzyme immunoassay reactive, or serum Treponema pallidum particle agglutination reactive) should be examined thoroughly for clinical manifestations of congenital syphilis. [ 8 ] Maternal records should be reviewed for evidence of maternal infection. Maternal serologic tests may have been negative in cases of extremely early or incubating syphilis. [ 8 ]

Evaluation should include: cerebrospinal fluid analysis for Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test, cell count, and protein; complete blood count, including differential and platelet count; and other tests if clinically indicated (e.g., long-bone x-rays, chest x-ray, liver enzymes, neuroimaging, auditory brain-stem response). [ 8 ]

Infants and children with clinical manifestations of congenital syphilis or abnormal evaluation should be treated with intravenous aqueous penicillin G. A single dose of intramuscular benzathine penicillin G may be considered after the 10-day treatment course of intravenous aqueous penicillin G to provide a more comparable duration as treatment for late syphilis. [ 8 ]

Infants and children with no clinical manifestations of congenital syphilis and normal evaluation (including normal cerebrospinal fluid evaluation) may be treated with up to 3 weekly doses of intramuscular benzathine penicillin G. [ 8 ]

Infants and children ages >1 month with acquired primary or secondary syphilis should be managed by a pediatric infectious disease specialist and evaluated for sexual abuse. [ 8 ] See Sexual abuse and assault .

Infants and children with a penicillin allergy or those who develop an allergic reaction presumed secondary to penicillin should be desensitized and treated with penicillin. [ 8 ] Skin testing may be used in children ages ≥2 years. The evidence for the use of nonpenicillin regimens is relatively weak.

Azithromycin

Ceftriaxone, primary prevention, secondary prevention.

People exposed within 90 days preceding diagnosis of primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis in a sexual partner should be treated presumptively, on the basis that they may be infected even if seronegative. It is estimated that 30% to 60% of sexual partners of people with early syphilis will develop the infection. [ 17 ]

People exposed more than 90 days before diagnosis of primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis in a sexual partner should be treated presumptively if syphilis serology is not available immediately and if follow-up may be problematic.

Treatment of long-term sexual partners of patients with latent syphilis is dependent on clinical evaluation and serology results.

For primary syphilis: exposure 3 months before treatment, plus duration of symptoms.

For secondary syphilis: 6 months plus duration of symptoms.

For early latent syphilis: 1 year.

Follow-Up Overview

Natural course of infection

Serology test results

Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction

Occurs within the first 24 hours after antibiotic therapy due to the rapid killing of treponemes.

Characterized by acute fever, headache, and myalgia, usually in patients with early syphilis. [ 8 ]

The likelihood of reaction is high in early syphilis but low in late syphilis. However, all patients should be advised of a possible reaction prior to receiving antibiotic treatment.

In pregnant women, Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction may cause fetal distress and premature labor. [ 8 ]

Treatment is supportive with oral fluids, acetaminophen, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Corticosteroid therapy may be considered to minimize the risk of a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in nonpregnant patients with cardiovascular syphilis or neurosyphilis. [ 10 ] However, the evidence of effectiveness is unclear and it is not routinely recommended in the US.

allergic reaction to penicillin

May arise in patients not previously known to be allergic.

In patients with penicillin allergy, alternative treatment options may be offered, dependent on the stage of syphilis.

Penicillin allergy skin testing and desensitization may be required (e.g., in the treatment of pregnant women).

Penicillin-allergic responses may include urticaria, angioedema, and anaphylaxis.

Treatment of allergic reaction is determined by the severity of the reaction.

asymptomatic progression of disease

Organ-specific complications can occur in untreated infection of unknown duration.

Specialist opinion should be sought depending on the nature of the complication (e.g., ophthalmology specialist opinion for ocular infection, cardiovascular specialist opinion for aortic regurgitation).

HIV infection

Syphilis facilitates the acquisition of HIV. [ 17 ]

iatrogenic procaine reaction

Occurs when intramuscular procaine penicillin G (e.g., used to treat neurosyphilis) is mistakenly administered intravenously.

Patients may develop penicillin allergic responses, including anaphylactic shock. [ 23 ]

Key Articles

Stoltey JE, Cohen SE. Syphilis transmission: a review of the current evidence. Sex Health. 2015 Apr;12(2):103-9. [Abstract] [Full Text]

British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH). UK national guidelines on the management of syphilis. December 2015 [internet publication]. [Full Text]

World Health Organization. Guidelines for the treatment of Treponema pallidum (syphilis). 2016 [internet publication]. [Full Text]

Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021 Jul 23;70(4):1-187. [Abstract] [Full Text]

World Health Organization. WHO guideline on syphilis screening and treatment for pregnant women. 2017 [internet publication]. [Full Text]

Referenced Articles

1. Stoltey JE, Cohen SE. Syphilis transmission: a review of the current evidence. Sex Health. 2015 Apr;12(2):103-9. [Abstract] [Full Text]

2. Baughn RE, Musher DM. Secondary syphilitic lesions. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005 Jan;18(1):205-16. [Abstract] [Full Text]

3. Newman L, Kamb M, Hawkes S, et al. Global estimates of syphilis in pregnancy and associated adverse outcomes: analysis of multinational antenatal surveillance data. PLoS Med. 2013;10(2):e1001396. [Abstract] [Full Text]

4. British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH). UK national guidelines on the management of syphilis. December 2015 [internet publication]. [Full Text]

5. Goh BT. Syphilis in adults. Sex Transm Infect. 2005 Dec;81(6):448-52. [Abstract] [Full Text]

6. O'Byrne P, MacPherson P. Syphilis. BMJ. 2019 Jun 28;365:l4159. [Erratum in: Syphilis. BMJ. 2019 Jul 19;366:l4746.] [Abstract] [Full Text]

7. World Health Organization. Guidelines for the treatment of Treponema pallidum (syphilis). 2016 [internet publication]. [Full Text]

8. Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021 Jul 23;70(4):1-187. [Abstract] [Full Text]

9. Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020 Feb 27;382(9):845-54. [Abstract]

10. British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH). UK national guidelines on the management of syphilis. December 2015 [internet publication]. [Full Text]

11. World Health Organization. Report on global sexually transmitted infection surveillance, 2018. 2018 [internet publication]. [Full Text]

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance, 2021. Apr 2023 [internet publication]. [Abstract] [Full Text]

13. Edmondson DG, Hu B, Norris SJ. Long-term in vitro culture of the syphilis spirochete Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum. mBio. 2018 Jun 26;9(3). [Abstract] [Full Text]

14. Lee V, Kinghorn G. Syphilis: an update. Clin Med (Lond). 2008 Jun;8(3):330-3. [Abstract] [Full Text]

15. Stoltey JE, Cohen SE. Syphilis transmission: a review of the current evidence. Sex Health. 2015 Apr;12(2):103-9. [Abstract] [Full Text]

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Transmission of primary and secondary syphilis by oral sex - Chicago, Illinois, 1998-2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004 Oct 22;53(41):966-8. [Abstract] [Full Text]

17. French P. Syphilis. BMJ. 2007 Jan 20;334(7585):143-7. [Abstract]

18. Ropper AH. Neurosyphilis. N Engl J Med. 2019 Oct 3;381(14):1358-63. [Abstract]

19. Clark EG, Danbolt N. The Oslo study of the natural course of untreated syphilis. Med Clin North Am. 1964;48:613-21.

20. Chaudhary PM, Roninson IB. Activation of MDR1 (P-glycoprotein) gene expression in human cells by protein kinase C agonists. Oncol Res. 1992;4(7):281-90. [Abstract]

21. Peterman TA, Heffelfinger JD, Swint EB, et al. The changing epidemiology of syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 2005 Oct;32(10 suppl):S4-10. [Abstract]

22. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of syphilis among men who have sex with men - Southern California, 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001 Feb 23;50(7):117-20. [Abstract]

23. Janier M, Unemo M, Dupin N, et al. 2020 European guideline on the management of syphilis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021 Mar;35(3):574-88. [Abstract]

24. Keuning MW, Kamp GA, Schonenberg-Meinema D, et al. Congenital syphilis, the great imitator-case report and review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 Jul;20(7):e173-9. [Abstract]

25. Saloojee H, Velaphi S, Goga Y, et al. The prevention and management of congenital syphilis: an overview and recommendations. Bull World Health Organ. 2004 Jun;82(6):424-30. [Abstract] [Full Text]

26. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Recommendations on reducing sexually transmitted infections. Jun 2022 [internet publication]. [Full Text]

27. Holmes KK, Levine R, Weaver M. Effectiveness of condoms in preventing sexually transmitted infections. Bull World Health Organ. 2004 Jun;82(6):454-61. [Abstract]

28. Tobian AA, Serwadda D, Quinn TC, et al. Male circumcision for the prevention of HSV-2 and HPV infections and syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2009 Mar 26;360(13):1298-309. [Abstract] [Full Text]

29. US Preventive Services Task Force. Syphilis infection in pregnant women: screening. Sept 2018 [internet publication]. [Full Text]

30. Molina JM, Charreau I, Chidiac C, et al. Post-exposure prophylaxis with doxycycline to prevent sexually transmitted infections in men who have sex with men: an open-label randomised substudy of the ANRS IPERGAY trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018 Mar;18(3):308-17. [Abstract] [Full Text]

31. Brown DL, Frank JE. Diagnosis and management of syphilis. Am Fam Physician. 2003 Jul 15;68(2):283-90. [Abstract]

32. Rompalo AM, Lawlor J, Seaman P, et al. Modification of syphilitic genital ulcer manifestations by coexistent HIV infection. Sex Transm Dis. 2001 Aug;28(8):448-54. [Abstract] [Full Text]

33. Lafond RE, Lukehart SA. Biological basis for syphilis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006 Jan;19(1):29-49. [Abstract] [Full Text]

34. Tucker JD, Li JZ, Robbins GK, et al. Ocular syphilis among HIV-infected patients: a systematic analysis of the literature. Sex Trans Infect. 2011 Feb;87(1):4-8. [Abstract]

35. Rottingen JA, Cameron DW, Garnett GP. A systematic review of the epidemiologic interactions between classic sexually transmitted diseases and HIV: how much is really known? Sex Transm Dis. 2001 Oct;28(10):579-97. [Abstract]

36. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease (STDs): syphilis & MSM fact sheet. 22 July 2021 [internet publication]. [Full Text]

37. Fojaco RM, Hensley GT, Moskowitz L. Congenital syphilis and necrotizing funisitis. JAMA. 1989 Mar 24-31;261(12):1788-90. [Abstract]

38. Hammerschlag MR, Guillén CD. Medical and legal implications of testing for sexually transmitted infections in children. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010 Jul;23(3):493-506. [Abstract] [Full Text]

39. Wheeler HL, Agarwal S, Goh BT. Dark ground microscopy and treponemal serological tests in the diagnosis of early syphilis. Sex Transm Infect. 2004 Oct;80(5):411-4. [Abstract]

40. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases: syphilis. CDC fact sheet (detailed). 10 August 2021 [internet publication]. [Full Text]

41. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Discordant results from reverse sequence syphilis screening - five laboratories, United States, 2006-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011 Feb 11;60(5):133-7. [Abstract] [Full Text]

42. Park IU, Fakile YF, Chow JM, et al. Performance of treponemal tests for the diagnosis of syphilis. Clin Infect Dis. 2019 Mar 5;68(6):913-18. [Abstract] [Full Text]

43. Pope V. Use of treponemal tests to screen for syphilis. Infect Med. 2004;21:399-402.

44. Seña AC, Wolff M, Behets F, et al. Rate of decline in nontreponemal antibody titers and seroreversion after treatment of early syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 2017 Jan;44(1):6-10. [Abstract] [Full Text]

45. US Food and Drug Administration. Possible false RPR reactivity with BioPlex 2200 Syphilis Total & RPR test kit following a COVID-19 vaccine - letter to clinical laboratory staff and health care providers. Dec 2021 [internet publication]. [Full Text]

46. Smith G, Holman RP. The prozone phenomenon with syphilis and HIV-1 co-infection. South Med J. 2004 Apr;97(4):379-82. [Abstract]

47. Kingston AA, Vujevich J, Shapiro M, et al. Seronegative secondary syphilis in 2 patients coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Dermatol. 2005 Apr;141(4):431-3. [Abstract]

48. British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH). BASHH national guideline on the management of sexually transmitted infections and related conditions in children and young people 2021. 2021 [internet publication]. [Full Text]

49. Lam TK, Lau HY, Lee YP, et al. Comparative evaluation of the INNO-LIA syphilis score and the MarDx Treponema pallidum immunoglobulin G Marblot test assays for the serological diagnosis of syphilis. Int J STD AIDS. 2010 Feb;21(2):110-3. [Abstract]

50. Hagedorn HJ, Kraminer-Hagedorn A, de Bosschere K, et al. Evaluation of INNO-LIA syphilis assay as a confirmatory test for syphilis. J Clin Microbiol. 2002 Mar;40(3):973-8. [Abstract] [Full Text]

51. Gayet-Ageron A, Lautenschlager S, Ninet B, et al. Sensitivity, specificity and likelihood ratios of PCR in the diagnosis of syphilis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2013 May;89(3):251-6. [Abstract]

52. Gayet-Ageron A, Sednaoui P, Lautenschlager S, et al. Use of Treponema pallidum PCR in testing of ulcers for diagnosis of primary syphilis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 Jan;21(1):127-9. [Abstract] [Full Text]

53. Shahrook S, Mori R, Ochirbat T, et al. Strategies of testing for syphilis during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Oct 29;(10):CD010385. [Abstract] [Full Text]

54. Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Guidance on syphilis testing in Latin America and the Caribbean: improving uptake, interpretation, and quality of testing in different clinical settings. 2015. 2015 [internet publication]. [Full Text]

55. Luger AF, Schmidt BL, Kaulich M. Significance of laboratory findings for the diagnosis of neurosyphilis. Int J STD AIDS. 2000 Apr;11(4):224-34. [Abstract]

56. Lavi R, Yarnitsky D, Rowe JM, et al. Standard vs atraumatic Whitacre needle for diagnostic lumbar puncture: a randomized trial. Neurology. 2006 Oct 24;67(8):1492-4. [Abstract]

57. Arendt K, Demaerschalk BM, Wingerchuk DM, et al. Atraumatic lumbar puncture needles: after all these years, are we still missing the point? Neurologist. 2009 Jan;15(1):17-20. [Abstract]

58. Nath S, Koziarz A, Badhiwala JH, et al. Atraumatic versus conventional lumbar puncture needles: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018 Mar 24;391(10126):1197-204. [Abstract]

59. Rochwerg B, Almenawer SA, Siemieniuk RAC, et al. Atraumatic (pencil-point) versus conventional needles for lumbar puncture: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2018 May 22;361:k1920. [Abstract] [Full Text]

60. Ahmed SV, Jayawarna C, Jude E. Post lumbar puncture headache: diagnosis and management. Postgrad Med J. 2006 Nov;82(973):713-6. [Abstract] [Full Text]

61. Arevalo-Rodriguez I, Ciapponi A, Roqué i Figuls M, et al. Posture and fluids for preventing post-dural puncture headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Mar 7;(3):CD009199. [Abstract] [Full Text]

62. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 752: prenatal and perinatal human immunodeficiency virus testing. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Sep;132(3):e138-42. [Abstract] [Full Text]

63. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK). Antenatal care. 19 August 2021 [internet publication]. [Full Text]

64. Simundic AM, Bölenius K, Cadamuro J, et al. Joint EFLM-COLABIOCLI recommendation for venous blood sampling. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2018;56(12):2015-38. [Abstract]

65. Hollier LM, Harstad TW, Sanchez PJ, et al. Fetal syphilis: clinical and laboratory characteristics. Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Jun;97(6):947-53. [Abstract]

66. Ropper AH. Neurosyphilis. N Engl J Med. 2019 Oct 3;381(14):1358-63. [Abstract]

67. Arnesen L, Serruya S, Duran P. Gestational syphilis and stillbirth in the Americas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2015 Jun;37(6):422-9. [Abstract] [Full Text]

68. Cole M, Perry K. MHRA 04109: ten syphilis EIAs. UK: HSMO; 2004.

69. Creegan L, Bauer HM, Samuel MC, et al. An evaluation of the relative sensitivities of the venereal disease research laboratory test and the Treponema Pallidum particle agglutination test among patients diagnosed with primary syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 2007 Dec;34(12):1016-18. [Abstract]

70. Manavi K, Young H, McMillan A. The sensitivity of syphilis assays in detecting different stages of early syphilis. Int J STD AIDS. 2006 Nov;17(11):768-71. [Abstract]

71. Cantor A, Nelson HD, Daeges M, et al. Screening for syphilis in nonpregnant adolescents and adults: systematic review to update the 2004 US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2016 Jun. Report No: 14-05213-EF-1. [Abstract] [Full Text]

72. Lewis DA. Chancroid: clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management. Sex Transm Infect. 2003 Feb;79(1):68-71. [Abstract] [Full Text]

73. Patterson K, Olsen B, Thomas C, et al. Development of a rapid immunodiagnostic test for Haemophilus ducreyi. J Clin Microbiol. 2002 Oct;40(10):3694-702. [Abstract] [Full Text]

74. US Preventive Services Task Force. Syphilis infection in nonpregnant adults and adolescents: screening. Sep 2022 [internet publication] [Full Text]

75. World Health Organization. WHO guideline on syphilis screening and treatment for pregnant women. 2017 [internet publication]. [Full Text]

76. World Health Organization. Screening donated blood for transfusion-transmissible infections: recommendations. 2009 [internet publication]. [Abstract] [Full Text]

77. Tucker JD, Bu J, Brown LB, et al. Accelerating worldwide syphilis screening through rapid testing: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010 Jun;10(6):381-6. [Abstract]

78. World Health Organization. The use of rapid syphilis tests. 2006 [internet publication]. [Full Text]

79. Young H. Guidelines for serological testing for syphilis. Sex Transm Infect. 2000 Oct;76(5):403-5. [Abstract]

80. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for partner services programs for HIV infection, syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydial infection. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008 Nov 7;57(RR-9):1-83;quiz CE1-4. [Abstract] [Full Text]

81. World Health Organization. WHO guideline on self-care interventions for health and well-being, 2022 revision. Jun 2022 [internet publication]. [Full Text]