An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

OHRP Guidance on Elimination of IRB Review of Research Applications and Proposals

NOTE : This guidance is consistent with the 2018 Requirements (i.e., the revised Common Rule).

Elimination of Institutional Review Board (IRB) Review of Research Applications and Proposals: 2018 Requirements

This guidance represents the Office for Human Research Protections’ (OHRP’s) current thinking on this topic. This guidance does not create or confer any rights for or on any person and does not operate to bind OHRP or the public.

OHRP guidance should be viewed as recommendations unless specific regulatory requirements are cited. The use of the word “must” in OHRP guidance means that something is required under the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) regulations at 45 CFR part 46. The use of the word “should” in OHRP guidance means that something is recommended or suggested, but not required. An institution may use an alternative approach if the approach satisfies the requirements of 45 CFR part 46. OHRP is available to discuss alternative approaches by telephone at 240-453-6900 or 866-447-4777, or by email at [email protected] .

Date: July 20, 2020

Scope: This guidance document applies to nonexempt research involving human subjects that is conducted or supported by HHS. It provides guidance on the elimination of the requirement in section 46.103(f) of the pre-2018 Requirements that each application or proposal for research undergo IRB review and approval as part of the certification process. This guidance also addresses the requirement in the 2018 Requirements for certification of each proposed research study prior to initiation.

Target Audience : Institutions, IRBs, investigators, HHS funding agencies, and others that may be responsible for the review, conduct, or oversight of nonexempt research involving human subjects conducted or supported by HHS.

Regulatory Background

In this document, the term “pre-2018 Requirements” refers to subpart A of 45 CFR part 46 (i.e., the Common Rule) as published in the 2016 edition of the Code of Federal Regulations. The pre-2018 Requirements were originally promulgated in 1991, and subsequently amended in 2005. The pre-2018 Requirements may also be referred to as the “pre-2018 Common Rule.”

The term “2018 Requirements” refers to the Common Rule as published in the July 19, 2018 edition of the e-Code of Federal Regulations. The 2018 Requirements were originally published on January 19, 2017 and further amended on January 22, 2018 and June 19, 2018. The 2018 Requirements may also be referred to as the “revised Common Rule.”

Any study initiated [1] on or after January 21, 2019 is required to comply with the 2018 Requirements. Any study initiated before January 21, 2019 is required to comply with the pre-2018 Common Rule, unless an institution voluntarily instead elected to transition such studies to comply with the 2018 Requirements. That election to transition a study must be documented and dated by the institution or an IRB. (45 CFR 46.101( l) More information about implementing the revised Common Rule is available on the OHRP website.

The 2018 Requirements include several provisions pertinent to certification, including the following:

“Certification means the official notification by the institution to the supporting Federal department or agency component, in accordance with the requirements of this policy, that a research project or activity involving human subjects has been reviewed and approved by an IRB in accordance with an approved assurance.” (45 CFR 46.102(a))

Note: The Federalwide Assurance (FWA) is the only type of assurance that OHRP approves.

“Certification is required when the research is supported by a federal department or agency and not otherwise waived under 45 CFR 46.101(i) or exempted under 45 CFR 46.104. For such research, institutions shall certify that each proposed research study covered by the assurance and [45 CFR 46.103] has been reviewed and approved by the IRB. Such certification must be submitted as prescribed by the federal department or agency component supporting the research. Under no condition shall research covered by [45 CFR 46.103] be initiated prior to receipt of the certification that the research has been reviewed and approved by the IRB.” (45 CFR 46.103(d)).

Pre-2018 Requirements:

The pre-2018 Requirements at 45 CFR 46.103(f) require an institution with an approved assurance to certify to HHS that each application or proposal covered by an OHRP-approved assurance and by 45 CFR 46.103 has been reviewed and approved by the IRB: that is, the research grant application and/or proposal submitted to an HHS component. Such certifications must be submitted with the application or proposal or by such later date as may be prescribed by the department or agency to which the application or proposal is submitted (45 CFR 46.103(f) of the pre-2018 Requirements).

2018 Requirements:

The 2018 Requirements eliminate the requirement in the pre-2018 Requirements that grant applications or proposals for research undergo IRB review and approval for the purpose of certification. Experience suggests that review and approval of the application or proposal is not a productive use of IRB time. Elimination of that requirement is not expected to reduce protections for human subjects because the research study (e.g. a research protocol) would remain subject to the requirement for IRB review and approval, assuming that an HHS component funds the research.

The 2018 Requirements at 45 CFR 46.103(d) require certification when the research is supported by HHS, and applicability of the regulations is not otherwise waived under 45 CFR 46.101(i) or the study is not exempted under 45 CFR 46.104. For such research, institutions must certify that each proposed research study covered by an OHRP-approved assurance and by 45 CFR 46.103 has been reviewed and approved by an IRB. Such certification must be submitted as prescribed by the federal department or agency component supporting the research. Under no condition shall research covered by 45 CFR 46.103 be initiated prior to receipt by HHS of the certification that the research has been reviewed and approved by the IRB.

Thus, for research to which the 2018 Requirements apply, the IRB must review and approve such research (e.g., a research protocol) for certification; however, the IRB no longer is required to review and approve the research grant application or proposal under the 2018 Requirements.

If you have specific questions about how to apply this guidance, please contact OHRP by phone at (866) 447-4777 (toll-free within the United States) or (240) 453-6900, or by e-mail at [email protected] .

[1] OHRP interprets “initiated” to mean research (1) initially approved by an IRB, (2) for which IRB review is waived, or (3) determined to be exempt on or after January 21, 2019 consistent with 45 CFR 46.101( l ).

- Whitepapers

- Ethics in Clinical Research

- FDA & ICH

- Regulatory Compliance

Drafting a Research Plan for IRB Review and Research Conduct: Information That Must Be Included in a Clinical Trial Protocol

A clinical trial is an interventional clinical study, in which participants are recruited for the administration of a specific intervention (use of a study drug, a procedure with a medical device, an educational intervention, etc.). Planning for a clinical research trial includes the development of a clinical protocol document. There are several reasons to have a clear and well-written protocol:

- So that the research plan is clearly defined to everyone who will participate in conducting the study, and all processes and procedures are clearly and completely described to avoid variation in procedures and the introduction of assessment bias into the study conduct

- So that oversight committees and agencies (Institutional Review Boards (IRBs)/Research Ethics Committees, scientific review committees, radiation safety or other committees, and regulatory agencies such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)) can review the research proposal in enough detail to ensure that it meets regulatory requirements to grant approval for the research conduct

- So that the endpoints, study design, data collection parameters, and the data analysis plan are prospectively defined prior to the research being conducted, and bias cannot be introduced by changing the design or analysis plan during the study (for this reason, many journals now require public posting of the full research protocol along with the publication of study results).

There are many ways to outline and describe the necessary components of the research protocol and plan, and there are many protocol templates that are available to serve as guidelines for protocol development. In this paper, we are addressing these requirements from the perspective of the IRB. Federal regulations dictate specific criteria against which the IRB must review all protocol submissions , to make an independent determination regarding whether the prospective research plan can be approved. If the protocol (or other documents such as the IRB submission form and consent documents that accompany the protocol in the submission) does not provide adequate or complete information for the IRB to make a determination that all criteria have been met, the IRB cannot approve the research plan. This document is intended to assist investigators and research teams by providing a list of the necessary information that they can use as a writing guide, or use as a checklist against the protocol and submission document package, to ensure that all the necessary information is included prior to submitting the protocol and plan for review by an IRB.

TABLE 1 lists the criteria for the approval of research (paraphrased here from the full regulatory language in 21 CFR 56.111 ) by an IRB, and describes the information that is necessary for the clinical protocol (or elsewhere in the research plan submitted for review), for the IRB to be able to make determinations regarding whether a research plan can be approved.

TABLE 2 describes additional components or documents that may need to be included, based on specifics of the study product or the study plan.

In addition, all protocol documents should:

- Be final documents. Draft protocols or other study documents should not be submitted for IRB review as the IRB must review final and complete study plans. If edits or changes are made after IRB review, the amended protocol must be resubmitted for approval of the changes.

- Include page numbers and/or section or outline numbering so that the location of content can be identified

- Include a table of contents

- Include some kind of version control notation (either a version number or version date) so that revisions of the documents can be clearly tracked.

TABLE 1: Necessary Information for All Protocol Submissions

Criterion for approval of the research proposal:.

That risks to participants are minimized by using procedures that are consistent with sound research design and that do not unnecessarily expose subjects to risk, and whenever appropriate, by using procedures already being performed on the subjects for diagnostic or treatment purposes.

Corresponding Information required in the Protocol/Research Plan:

- A clear and detailed list of all study procedures, including screening and follow-up procedures (often in tabular format, describing the procedures to be conducted at each study visit). “Procedures” includes (but is not limited to) study visits; interviews for the collection of safety or other data; vital sign measurements; surveys, questionnaires, or diary completion; study drug administration or other investigational study intervention; invasive and non-invasive procedures including blood draws, radiologic tests or other diagnostic testing.

- The protocol should very clearly define what visits, assessments and procedures would be occurring as part of standard care

- If participants need to leave the study early or suddenly, the protocol should include any specific testing or follow-up that may need to occur for safety purposes.

That risks to subjects are reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits, if any, to subjects, and the importance of the knowledge that may reasonably be expected to result.

- the scientific knowledge expected to result from the research project

- the potential direct benefits to individual research participants in the study

- The protocol should also contain a clear and complete description of the study drugs/study intervention including (as appropriate) dosing information, storage information, and criteria for dose modification or dose adjustments.

That the selection of subjects is equitable.

- Eligibility criteria should be designed to make the study as inclusive as possible while excluding persons with factors or conditions that unacceptably increase the potential risks, or unreasonably confound the measurement of study endpoints

- Consider demographics, medical history and co-morbidities, concomitant medications, and whether the protocol must include testing for the presence or absence of conditions specified in the criteria

- It is not necessary to specify opposite factors in both lists, i.e., if inclusion criterion is age ≥ 18, the exclusion does not need to specify age < 18.

Informed consent will be sought from each prospective subject or the subject’s legally authorized representative.

Informed consent will be appropriately documented or appropriately waived.

- While the protocol submission must include a written informed consent document, it should also describe the process of obtaining informed consent from participants; how they will be identified and contacted, who will approach them about the study, and how they will be given adequate opportunity to ask questions during the consent discussion

- The written informed consent document must provide all of the elements required by federal regulations

- If potential participants may be incapable of providing informed consent and consent must be provided by legally authorized representatives, the consent process must describe this and the consent form must have appropriate signature spaces

- While there are circumstances in which the regulations allow either a waiver of documentation of consent (no signature) or a waiver of obtaining consent for standard or for emergency research , if a waiver is requested the submission should describe how the proposed research meets the specific requirements for these waivers, and how participants’ rights and privacy will be protected if the waiver is granted.

When appropriate, the research plan makes adequate provisions for monitoring the data collected to ensure the safety of subjects.

- The protocol should include an adequate description of the safety and efficacy data points that will be collected, including how adverse events will be collected, recorded, graded, and assessed

- How will safety data be monitored on an ongoing basis to identify any unanticipated safety issues during the study? Who will review the data, and will the study include a Data Safety Monitoring Committee, Data Monitoring Committee, or Adjudication Committee?

When appropriate, there are adequate provisions to protect the privacy of subjects and to maintain the confidentiality of data.

- The protocol or associated documents should describe how the privacy of participants will be protected (including if appropriate how people will be approached about the study and given the opportunity to ask questions in a private setting), as well as how the data being collected will be anonymized or de-identified, stored, transferred and analyzed to maintain confidentiality.

When some or all of the subjects are likely to be vulnerable to coercion or undue influence, such as children, prisoners, individuals with impaired decision making capacity, or economically or educationally disadvantaged persons, additional safeguards have been included in the study to protect the rights and welfare of these subjects.

- Note that federal regulations have specific sections for additional precautions required in the research when research is conducted on children , pregnant persons , and prisoners . Inclusion or exclusion of these groups should be specified in the eligibility criteria.

- Consideration should also be given to whether the protocol should include specific steps for the protection of participants who may be unable to make consent decisions (temporarily or permanently).

TABLE 2: Additional Components to Include when Appropriate

Circumstance or condition:.

If the protocol is evaluating the safety and/or efficacy of a drug, biologic or medical device (even if the drug, biologic or medical device is already FDA approved).

Additional information or documents that must be provided:

The regulatory status of the drug/device must be provided to the IRB, either via

- a description in the protocol,

- the submission form, or

- a copy of a letter from the FDA.

For drugs or biologics , the documentation must include an (Investigational New Drug (IND) number or a regulatory-based rationale for why the product is considered IND-exempt (21 CFR 312.2).

For medical devices , the documentation must specify whether the device is used ‘on label’ (for exactly the same indication and circumstances for which is has already been FDA-cleared or approved) or is investigational. If the device is investigational, the documentation must include an Investigational Device Exemption (IDE), an NSR justification, or a regulatory-based rationale for why the device is considered IDE-exempt.

When the protocol is evaluating interventions for foods , herbal products , dietary and other supplements, vitamins , and cosmetics , a regulatory-based justification for why that agent is not considered a drug or biologic as used in the research must be provided. Remember that foods that are being researched for possible use as drug products (looking for evidence of action in diagnosing, treating or mitigating a disease or condition) are regulated as drugs.

The IRB must ensure that research is being conducted in compliance with FDA regulations, so submitting appropriate documents or explanations may prevent questions during the review process. If the IRB cannot confirm documentation, or if the IRB is not completely sure that the FDA would agree with the justification for why certain research would not need FDA oversight (i.e., would be IND- or IDE- exempt), the IRB must ask the researcher/sponsor to consult with FDA and obtain documentation that FDA agrees that their oversight is not indicated.

Some or all of the subjects are likely to be vulnerable to coercion or undue influence, such as children, prisoners, pregnant persons, individuals with impaired decision-making capacity, or economically or educationally disadvantaged persons.

When persons from vulnerable populations may be enrolled in the research the research plan must always specify this and consideration should also be given to whether the protocol should include specific steps for the protection of participants who may be unable to make consent decisions (temporarily or permanently).

Note that federal regulations have specific sections for additional precautions required in the research when research is conducted on children , pregnant persons , and prisoners .

The study includes the use of surveys, questionnaires or other instruments (quality of life assessments, etc.).

If the protocol includes the use of surveys, all survey questions must be submitted as part of the protocol, an attachment to the protocol, or a supplemental document. If standardized questionnaires or instruments are being used, these must also be submitted. The IRB is required to review all participant-facing materials, including participant diaries and participant recruitment materials [note: some IRBs, including WCG IRB, do not require submission of common, standard instruments such as the SF-36, but if there is any doubt about whether submission is required it is better to add it and avoid possible delays].

Study participants must provide written informed consent.

The informed consent document must be provided for review and must have all the elements required by regulations .

A waiver of informed consent documentation is being requested.

In addition to the regulatory-based justification for the waiver (see Table 1), a Participant Information Sheet must be included in the submission.

A waiver or alteration of HIPAA requirements is being requested.

A regulatory-based justification must be provided specifying how the research is eligible for the waiver or alteration.

For researchers new at conducting clinical research or writing protocols, developing a new clinical trial protocol that is complete and sufficient for the purposes for which it will be needed is often a larger and more time-consuming project that was initially expected. While IRBs are generally happy to provide information and to answer specific regulatory questions in advance of a protocol being submitted, most do not have the resources or capacity to provide one-on-one guidance to researchers who have protocols that need major revisions to meet the criteria for approval.

Researchers may find it best to work with an experienced medical writer or clinical research consultant; while the cost of these services can be significant, this may be the most cost-effective plan when balanced against the time saved by the researcher and the facilitation of the review and approval process when guided by someone who is familiar with clinical research regulations.

Learn more about our ethical and scientific review solutions

Don't trust your study to just anyone.

WCG's IRB experts are standing by to handle your study with the utmost urgency and care. Contact us today to find out the WCG difference!

MAGI@home 2024

MAGI@home brings you and your team best-in-class, accredited training and education from the comfort of your home or office. Event Details

As the nation’s largest public research university, the Office of the Vice President for Research (OVPR) aims to catalyze, support and safeguard U-M research and scholarship activity.

The Office of the Vice President for Research oversees a variety of interdisciplinary units that collaborate with faculty, staff, students and external partners to catalyze, support and safeguard research and scholarship activity.

ORSP manages pre-award and some post-award research activity for U-M. We review contracts for sponsored projects applying regulatory, statutory and organizational knowledge to balance the university's mission, the sponsor's objectives, and the investigator's intellectual pursuits.

Ethics and compliance in research covers a broad range of activity from general guidelines about conducting research responsibly to specific regulations governing a type of research (e.g., human subjects research, export controls, conflict of interest).

eResearch is U-M's site for electronic research administration. Access: Regulatory Management (for IRB or IBC rDNA applications); Proposal Management (eRPM) for the e-routing, approval, and submission of proposals (PAFs) and Unfunded Agreements (UFAs) to external entities); and Animal Management (for IACUC protocols and ULAM).

Sponsored Programs manages the post-award financial activities of U-M's research enterprise and other sponsored activities to ensure compliance with applicable federal, state, and local laws as well as sponsor regulations. The Office of Contract Administration (OCA) is also part of the Office of Finance - Sponsored Programs.

Ethics & Compliance

- eResearch IRB NextGen Project

- Class Assignments & IRB Approval

- Operations Manual (OM)

- Authorization Agreement Process

- ORCR Policies and Procedures

- Self-Assessment Tools

- Resources and Web Links

- Single IRB-of-Record (sIRB) Process

- Certificate of Confidentiality Process

- HRPP Education Resources

- How to Register a Clinical Trial

- Maintaining and Updating ClinicalTrial.gov Records

- How to Report Clinical Trial Results

- Research Study Participation - FAQ

- International Research

- Coordinated Services & Practices (CSP)

- Collaborative Research: IRB-HSBS sIRB Process

- Data Security Guidelines

- Research Incentive Guidelines

- Routine fMRI Study Guidelines

- IRB-HSBS Website Directory and Guidance

- Waivers of Informed Consent Guidelines

IRB Review Process

- IRB Amendment Process

- Continuing Review Process

- Incident Reporting (AE/ORIO)

- IRB Repository Application

- IRB-HSBS Education

- Newsletter Archive

You are here

- Human Subjects

- IRB Health Sciences and Behavioral Sciences (HSBS)

U-M HRPP Operations Manual References

IRB approval criteria: Part 3, Section III, C 6

Regulated/not regulated research: Part 4, Section V

Exempt research policy: Part 4, Section VI

Using the U-M IRB System

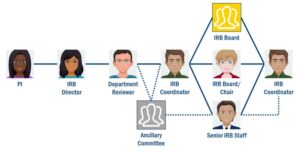

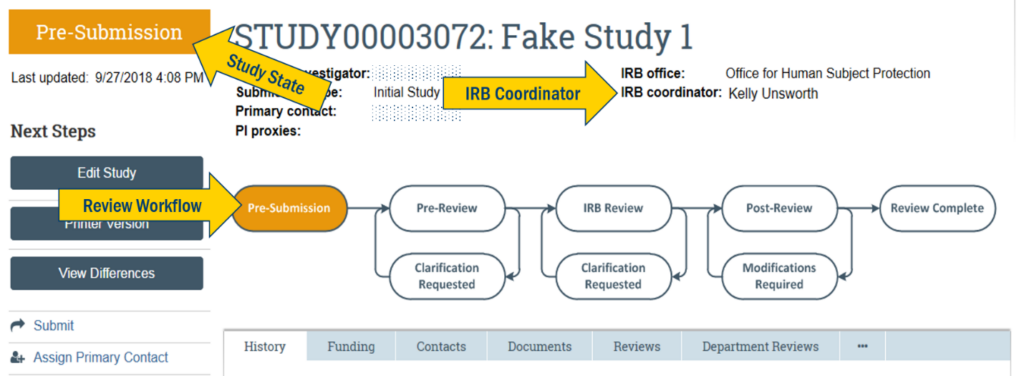

IRB staff and board members have access to the IRB application and posted correspondence via the eResearch Regulatory Management (eRRM) system. The system facilitates the IRB review process by:

- Providing regulatory checklists that guide IRB staff review

- Routing submissions to ancillary committees (e.g., COI-UMOR), as applicable

- Re-routing submissions to a different U-M IRB, if applicable

IRB-HSBS Turnaround Times

"Turnaround" is the estimated time it takes to complete the IRB review and determination process.

Full-board : 4 - 8 weeks

Expedited : 2 - 4 weeks

Exempt : < 1 week

The U-M Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) fulfill their goals to protect human research participants and support the design and conduct of sound research by reviewing and approving IRB submissions for new applications, amendments, and continuing reviews.

All projects that meet the definition of research with human subjects ( 45 CFR 46.102 ) must be reviewed and approved by an IRB, or receive an exempt determination, prior to beginning the research. The IRB staff initially screens submissions to determine the completeness and the appropriate type of review. Submissions may be returned to the study team for changes before the review type is assigned. The review type may be reassessed at any time during the review process.

Types of IRB Review

The basic types of IRB Review are: Comprehensive , Exempt , and Not Regulated . The type of IRB review and the associated review process (e.g., full board , expedited , limited IRB review , system-generated ) are determined by the:

- Level of risk to research participants

- Type of research being conducted (e.g., an educational intervention, a survey, an ethnographic observation, etc.)

- Sensitivity of the research questions or complexity of the research design

- Involvement of vulnerable populations as research participants

- Use of identifiable information or indentifiable biospecimens

- Applicability of one or more of the criteria for exempt or expedited review

Research Requiring Comprehensive IRB Review

The IRB may conduct either an expedited or full board review for IRB-regulated research proposed in the Interaction/Intervention or Secondary Use application types to ensure:

- Risks to the subjects are minimal, and are reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits

- The subject selection is equitable

- Privacy and confidentiality are protected

- Informed consent processes meet federal regulatory and U-M requirements

Full Board Review

Federal regulations and institutional policy require a review by the IRB Full Board for applications where the research involves more than minimal risk to human subjects, does not meet the criteria for one of the categories of expedited review , or has been referred to the committee by an expedited reviewer or the Chair. Regardless of risk level, IRB-HSBS may require full board review when the research involves:

- Vulnerable populations, particularly prisoners

- Sensitive topics, including illegal behaviors which may require an NIH Certificate of Confidentiality (CoC) to protect subject data from compelled disclosure

- Research involving genetic/genomic analyses

- A complex research design requiring the expertise of multiple board members to evaluate

The IRB posts submission deadlines for upcoming IRB meeting dates. If an application is “board ready”, meaning that it contains all of the information and materials necessary for the full board to conduct its review, the application will be assigned to the next IRB meeting date (see Related Information to the right for schedule links), except where the agenda is already full or a reviewer with the necessary expertise is not available for that meeting. IRB staff assign submissions to a primary and secondary IRB reviewer for presentation at the full board meeting. Investigators may be invited to attend the meeting to answer questions from the board. At the conclusion of the meeting, the board votes and issues a determination for the submission.

IRB Full Board Determinations

Approved : the application is approved as submitted. The approval date is the date of the IRB review.

Approved with Contingencies : the application is approved, contingent on submission of specified changes to the protocol, informed consent document(s) and/or other supporting materials. Final approval status is granted when the IRB has reviewed and approved all requested changes. The date of the "approved with contingencies" determination is deemed the date of approval.

Action Deferred : the IRB needs additional information from the investigator before the IRB can make all of the determinations found at 45 CFR 46.111 necessary to approve the study. The principal investigator must submit the requested additional information before the IRB will consider the application for further review.

Disapproved : the protocol does not provide adequate protection to human participants, and it is unlikely that it can be modified to provide such protection. The IRB notifies the principal investigator of the disapproval in writing, including a statement of the reasons for its decision, and provides the opportunity for the investigator to respond to the IRB in person or in writing.

Tabled : the IRB full board did not have time to review the application at the convened board meeting. The application is placed on the agenda for the next convened meeting.

Expedited Review

Federal regulations ( 45 CFR 46.110 ) authorize the use of an expedited review process for:

- Minimal risk human research that meets one or more of the OHRP Expedited Review Categories

- Minor changes to research previously approved by the full board

Applications qualifying for expedited review are assigned to an expediting reviewer, an experienced IRB member appointed to the role by the IRB Chair. The expediting reviewer has the authority to make a determination or to refer a submission for full board review for multiple purposes (e.g., clarification, expertise), including in cases of disapproval. Only the full board has the authority to disapprove a study. Most studies that qualify for the expedited review process do not require annual Continuing Review .

IRB Expedited Review Determinations

In addition to the Approved and Approved with Contingencies determinations ( described above ) reviewer may issue a Changes Requested determination, when substantial changes to the application and/or materials are required before the expediting reviewer can approve the study.

Exempt Research Review

Per university policy, investigators must submit an IRB application for determination of exemption before research begins. Applications are routed for exempt review through the Interaction/Intervention application or the Secondary Use application types. IRB-HSBS recommends using the Brief Protocol for Exempt Research Projects (download) to provide an overview of you exempt project or as a data entry guide when completing the IRB application.

Projects that meet the criteria for a federal exemption category (45 CFR 46.104) or for a U-M exemption #5 may be granted a determination of exemption by the IRB, or where applicable, through the system-generated review process. The review determination, whether conducted by the IRB or system-generated, is limited in scope to the information necessary to determine if the proposed exemption applies. The IRB does not review informed consent documentation or recruitment materials for proposed exempt studies. Exemptions may be granted by the IRB Chair, expedited reviewers, or (in most cases) qualified IRB staff members.

Projects receiving an exempt determination are not subject to the Continuing Review process . Amendments are required only if the changes to the project would alter the exemption criteria. An exempt determination does not lessen the researcher's ethical obligations to participants as articulated in the Belmont Report or to the codes of conduct for specific disciplines.

Limited IRB Review

The Common Rule provides a Limited IRB Review process, which is a required expedited review of recruitment and consent materials as well as plans to maintain participant privacy and data confidentiality for exempt 2 and 3 projects that collect or use sensitive and identifiable data . An exempt determination is issued once the expediting reviewer confirms that these protections are acceptable.

Not Regulated Review

Not all research-related activities that involve people, their data, or their biospecimens are covered by the regulations governing human research. However, investigators may wish to submit a brief eResearch IRB application for a formal “not regulated” determination for funding or publication purposes; or, the investigator may be able to issue a system-generated determination letter without submission to the IRB.

Submission to the IRB is not required for the following activities:

- Case studies

- Class activities

- Journalism/documentary activities

- Oral history

- Quality assurance and quality improvement activities

- Research on organizations

- Research using deidentified data or biospecimens

- Research using publicly available data sets

Some categories require IRB review for the purpose of assessing compliance with HIPAA or other regulations. These include:

- Research involving existing information or biospecimens that have been coded before the researcher receives them, but identifiers exist

- Research involving deceased individuals only

- Pre-review of clinical data sets preparatory to research

- Standard public health surveillance or prevention activities

For a complete list of not regulated research activities, see the HRPP Operations Manual, Part 4 .

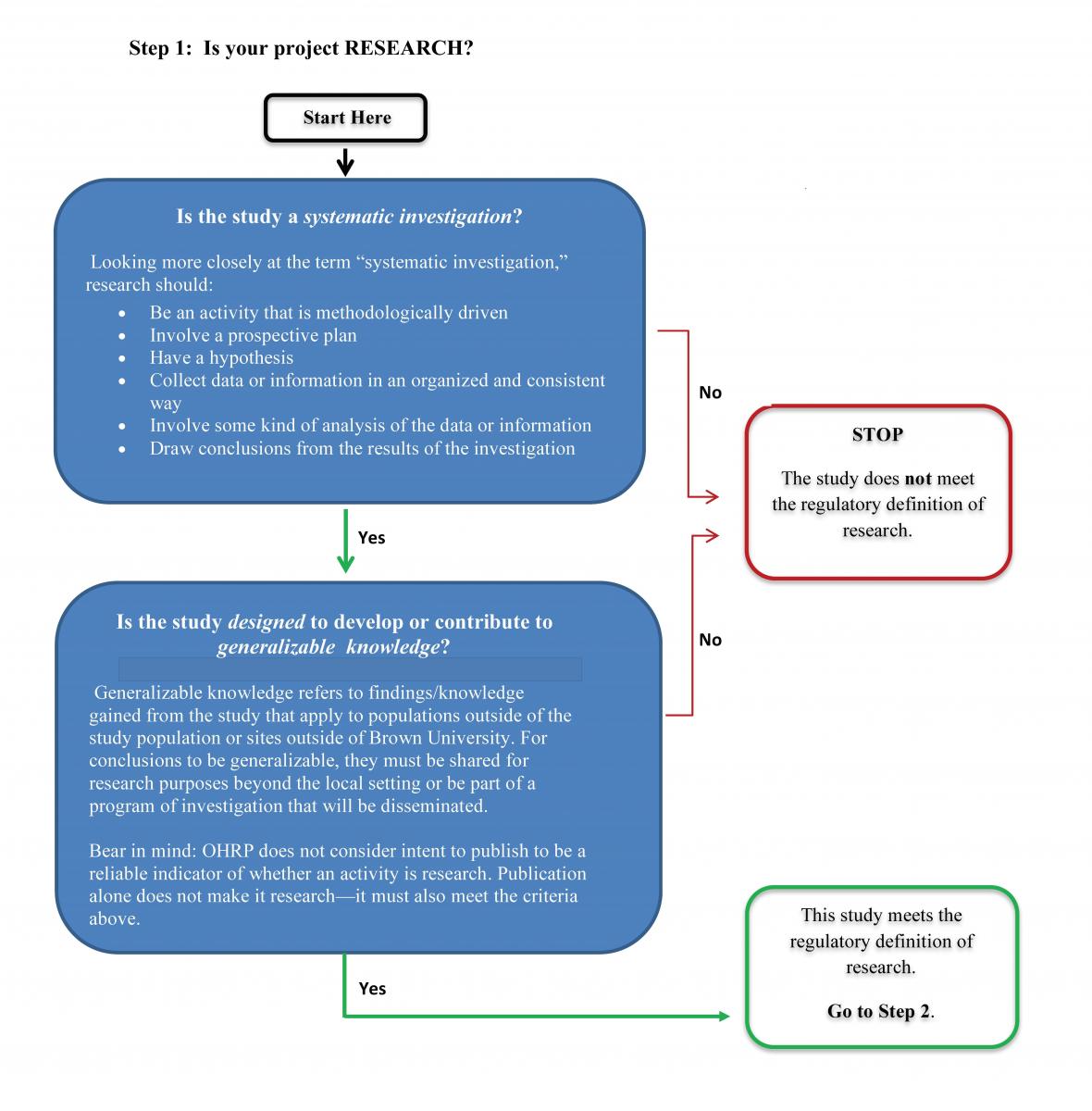

If you can answer "yes" to the following questions, you need to submit an IRB application in eResearch for IRB review:

1. Is it research?

Research is a systematic investigation (including research development, testing, and evaluation) designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge ~ Federal definition, 45 CFR 46.102 (l)

- Activities such as the practice of public health, medicine, counseling, or social work are not research.

- Studies for internal management purposes (e.g., program evaluation, quality assurance, or quality improvement) are not research because the intent is not to provide generalizable knowledge but to apply findings only to the program or activity.

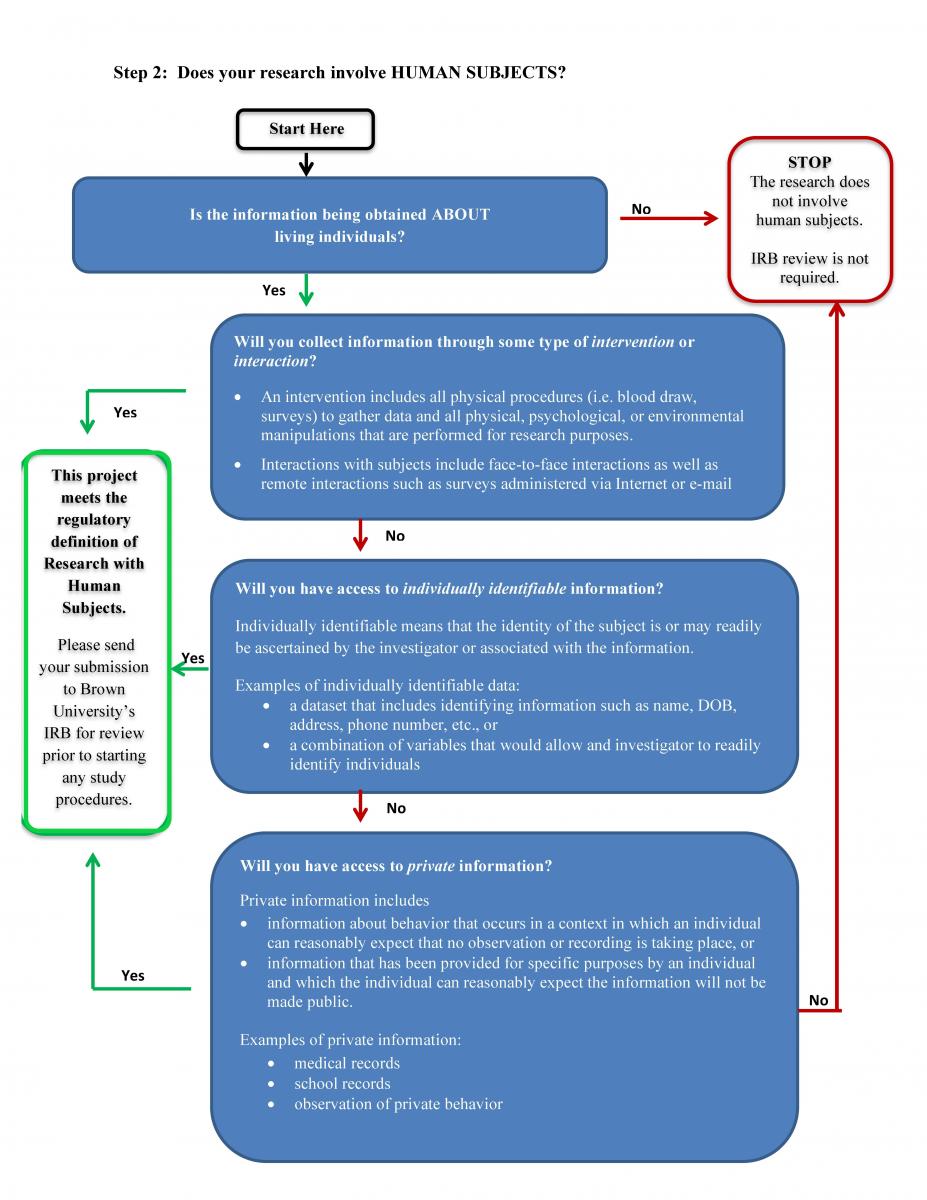

2. Does the research involve human subjects?

Human subjects research is a project that involves a living individual about whom the investigator (whether student or professional) (i) obtains information or biospecimens through interaction/intervention with the individual, and uses, studies, or analyzes the information or biospecimens; or (ii) obtains, uses studies, analyzes, or generates identifiable private information or indentifable biospecimens. ~ Federal definition 45 CFR 46.102 (e)(1)

3. Is the university engaged in the conduct of the research?

The university is "engaged" when the research is conducted by U-M faculty, staff, trainee, or other agent acting in connection to their university responsibilities. See OHRP's Guidance on Engagement of Institutions for more information and examples.

- Direct awards from federal sponsors that meet criteria #1 and #2 are always reviewed by a U-M IRB, whether or not the university is engaged in the research.

- If you answer "no" to any of these questions, you may have other obligations than IRB review. See the U-M HRPP Operations Manual Part 4, Section V for more information about regulated/non-regulated research.

IRB Health Sciences and Behavioral Sciences Phone: (734) 936-0933 Fax: (734) 936-1852 [email protected]

- Human Subjects Protections

- Request Info

- Faculty & Staff

- Job Seekers

- Scholarships & Aid

- Student Life

- Institutional Review Board

- Proposal Guidance

Research Proposal Guidance

Does your research require irb approval.

Research is defined as a systematic investigation, including research development, testing and evaluation, designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge. A project requires IRB review if it includes both research and human subjects. The IRB must make the final determination of whether or not a study requires review.

If you are wondering whether or not your research requires IRB oversight, the first question you should ask yourself is: Does your project involve human subjects? If your research does, then it requires IRB approval and you should continue reading this webpage. If it does not, then you do not need IRB approval.

Research That Involves Human Subjects

Below are a few examples of research that typically involve human subjects. This is not a comprehensive list and there are often exceptions to each research.

Generalizing Findings

Activities that obtain data about individuals, systematically performed with the intent to generalize findings.

Viewing Identifable Private Information

Identification of potential participants for a study or use of living individuals’ data for research purposes, whether or not the data will be recorded in an identifiable manner.

Survey, Interview, Observation

Collection of individuals’ data using surveys, interviews, or observation with the intent to generalize findings.

Audio or Videotaping

Taping individuals for study in situations not normally expected to be recorded or when individuals can be identified from recordings.

Research That Does Not Involve Human Subjects

Below are a few examples of research that typically does not involve human subjects. This is not a comprehensive list and there are often exceptions to each research.

Study or use of data that cannot be readily associated with the living individual about whom the information relates. There are some exceptions. Be sure to contact IRB for assistance.

Quality Improvement

Activities involving individuals intended solely for internal use, performed to improve services or develop new services or programs, (e.g., satisfaction surveys) without intent to generalize findings, even if results will be presented or published; audits (internal or external) performed as a part of organizational operations. There are some exceptions. Be sure to contact IRB for assistance.

Data Banking

Collection and storage of private information, if the data may be used in the future for research purposes, whether or not the data will be recorded in an identifiable manner.

Examples of Research & IRB Approval

Below are examples of research and whether or not they need IRB approval. Research that do need IRB approval also have levels of review.

Surveys, Questionnaires & Interviews with Adults

Not all survey, questionnaire, or interview research is minimal risk. For example, a survey or interview that asks questions about sensitive topics (childhood abuse, sexual functioning) likely to cause emotional stress or discomfort may require full IRB review. Some survey research may be classified as exempt from committee review if the information obtained is recorded in a way that the subject cannot be identified (either directly or through a code numbers or link); in other words, if the research data are anonymous.

A survey or interview study may also be considered exempt from committee review even when the data are not anonymous if the information being gathered could not reasonably place the subject at risk of criminal or civil liability or be damaging to the subject’s financial standing, employability, or reputation.

The most common classification for survey, questionnaire, or interview research is expedited approval. If the study is not anonymous and contains information that, if known, could be damaging as described above, but it does not rise to the level of more than minimal risk, it may be given expedited approval. Although the proposal application gives the investigator the opportunity to indicate a classification, the IRB makes the final determination as to the classification of exempt or expedited.

Normal Educational Practices

Normal education practices are considered exempt from committee review, but must still be reviewed and approved by the IRB office. Some examples of this could be a students’

- Curriculum-related written work, test scores, grades, artwork and other work samples produced by children

- Curriculum-related oral and non-verbal communicative responses individually, such as in an interview, in small groups and with the whole class

- Responses (written, oral or behavioral) to curriculum-related activities

- Level of active participation in curriculum-related activities

Please note: A “normal educational setting” means preschool, elementary, secondary, and higher educational facilities, and after-school programs (if the project relates to tutoring, or homework help). In Special Education, normal educational practices correspond to the Individualized Educational Program (IEP), which is tailored to each student with an identified disability and may be implemented in diverse settings (school, home, work, community).

Collection Methods

The following list outlines the ways in which a researcher may collect the information for their research.

- Videotapes and photographs of curriculum-related classroom activities

- Audio tapes of teacher-student and student-student discourse related to the assignment

- Teacher’s non-participant observation of curriculum-related activity of individual children or groups of children, noting what will be observed and how it will be analyzed, or whether it will be used as anecdotal evidence in the study

- Teacher’s commentary on students’ curriculum-related written work, artwork and other artifacts produced by children

- Student journals and communication books related to the curriculum

- Student grades and test scores

- Teacher journals, notes and reflective comments on student responses and participation in curriculum-related activities

- Questionnaires or interviews with students, parents and family members, teachers and administrators

- Non-participant classroom observations by colleagues, with the class teacher’s permission, stating what will be observed and how it will be used (i.e. How data will be analyzed or whether it will be used as anecdotal evidence)

Research for University Courses

Research conducted solely for pedagogical purposes may be excluded from IRB review, under the following conditions:

- The instructor’s intention is to teach professional research methods such as interviewing, surveying, or experimental design

- The data are gathered solely for the purposes of teaching how to analyze them

- The results will remain in the classroom

These data can be presented at the end of the semester within the confines of the institution, for instance, at Scholars Day. However, if the results will be published (including on Digital Commons), presented at a larger conference off-campus, or generalized in some other way, it will be necessary to obtain IRB approval.

If a class project evolves into a research project that the student/instructor wishes to publish or generalize, then the research will need to undergo IRB review. This should occur as soon as it is known that the data will be used for research. If this is not determined until after the research is completed, the investigator should submit a protocol to the IRB requesting permission to use existing data.

Professors, students, and research assistants are asked to submit the In-Class Research Form prior to beginning their in-class research projects to verify whether the proposed activity will require an IRB approval process.

Pilot Studies

Pilot studies with human research volunteers, no matter how small, must obtain IRB approval. You can include the pilot study as a smaller section of the complete protocol, or you can get approval for the pilot study first, then come through the IRB again for a review of the full “parent” study. At this stage, you may have modified your research to take into account the results of the pilot study. (For example, you may decide to change the survey questions as a result of the pilot study, or change inclusion/exclusion criteria.)

Oral History

The researcher’s intention plays a large part in determining whether research is an oral history or not. If the intention is to interview informants who have a unique perspective on a particular historical event or way of life, and the researcher also intends to let the informant’s stories stand on their own as a “testimonial” or in an archive, with no further analysis, the research is most likely oral history.

However, if the surveys or interviews are conducted with the intention of comparing, contrasting, or establishing commonalities between different segments or among members of the same segment, it is safe to say your research will be regular survey/interview procedures, because you will be generalizing the results.

Historians explain a particular past; they do not create general explanations about all that has happened in the past, nor do they predict the future.

Moreover, oral history narrators are not anonymous individuals, selected as part of a random sample for the purposes of a survey. Interviewees are selected because of their personal relationship to the topic under investigation. An oral history interview provides one person’s unique perspective. A series of oral history interviews offers up a number of particular, individual perspectives on the topic, not information that may be generalized to all research volunteers in the event or time under investigation.

Oral history interviews are not analyzed in the same way that qualitative data is generally analyzed. No content analysis, discourse analysis, coding for themes or other qualitative analysis methods of data analysis are performed on the interviews. They stand alone as unique perspectives.

It is primarily on the grounds that oral history interviews, in general, are not designed to contribute to “generalizable knowledge” that they are not subject to the requirements of 45 CFR part 46 and, therefore, can be excluded from IRB review.

Secondary Analysis of Existing Data

Research involving the secondary analysis of existing data must be reviewed by the IRB to ascertain whether or not it requires IRB oversight.

Such research will be considered exempt if one or more of the following are true:

- The sources of such data are publicly available

- The information is recorded by the investigator in such a manner that subjects cannot be identified, directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects

- The dataset has been stripped of all identifying information and there is no way that the data could be linked back to the subjects from whom it was originally collected

Such research will qualify for an expedited or full-board review if:

- The source of the data is not publicly available data and/or contains private identifiable information about living individuals

Content Experts/Consultants/Key Informant

It may not be necessary to get IRB approval if interview questions are with experts about a particular policy, agency, program, technology, technique, or best practice. The questions are not about the interviewee themselves, but rather about the external topic. For instance, questions will not include demographic queries about age, education, income or other personal information.

IRB review will be required when a researcher is interviewing individuals about content, but there is a research question or hypothesis involved and when a researcher intends to analyze and generalize the results–that look for common themes in the collected data, try to universalize the interviewees’ experiences, or quantify the results in some way.

Examples That May Be Excluded From IRB Review

In all the following examples, the questions are focused on the facts about the program, policy, software, curriculum, procedures or project. The researcher will simply report the facts as they are related by the content experts. You may not need to submit a protocol or an informed consent form for IRB approval if one or more of the following are true. You are,

- Interviewing managers in a company about their billing procedures, or their use of a particular software program

- Interviewing or surveying teachers about what should be included in the development of a particular curriculum unit

- Asking a panel of nurses and doctors to review your antismoking program for teens for correct medical content

- Interviewing social agency directors about their client intake procedures

Additional Resources

The following decision flowcharts can help you determine whether your project requires IRB oversight.

Is an Activity Research Involving Human Subjects?

Is the Human Subjects Research Eligible for Exemption?

Getting Started

Before you begin to set up an IRB, read and become familiar with the federal regulations that apply to research with human participants as specified in 45 CFR 46 and the " Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research " (National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 1979). An essential resource is the 100-page "Institutional Review Board (IRB) Guidebook" published by the Office of Human Research Protections (OHRP). This guidebook is available for purchase or free download from the OHRP website. The OHRP website has everything you need for creating your IRB.

Keep in mind that the basic job of the IRB is to protect the rights and welfare of human research participants and facilitate research by using the basic ethical principles from the Belmont Report.

The Nuts and Bolts

This section summarizes some of the key federal regulations for establishing an IRB. Please keep in mind that this is a brief summary; be sure to refer to 45 CFR 46 for complete and specific information about these regulations.

Size of the IRB

According to federal regulations, the minimum number of people required for an IRB is five; however, you can certainly have more than five members. The number of members will most likely depend on the size of the institution and the IRB workload. The availability of potential members will also affect the number of members you choose to have on your IRB.

Your institution may have more than one IRB. Many universities have multiple IRBs that specialize in particular types of research. If you are working for a community college or other undergraduate college that has multiple campuses, it may be advisable to have multiple IRBs so that each campus has its own review panel. This may help speed up the review process for each individual proposal.

Composition

As noted above, an IRB must consist of a minimum of five members of varied backgrounds to facilitate diversity in its composition. Accordingly, if you are doing federally funded research, you will need to make sure that your IRB is composed of members who represent the following characteristics:

Scientific area. At least one member must work in science (e.g., biology, psychology, chemistry).

Nonscientific area. At least one member must work in a nonscience area (e.g., history, English, philosophy).

External to the institution. One member must come from outside the institution and not be affiliated with the institution.

Diversity of representation. An effort must be made to achieve diversity of representation, particularly if members of a “vulnerable population,” such as children or people with intellectual disabilities, are frequently a subject of study (see Definitions ). If such populations will be used, someone who has knowledge of or experience with those populations should participate as a member of the IRB.

Diversity of gender. The IRB should have both male and female representation.

Diversity of profession. The IRB should not have representation from just from one profession, such as psychology.

If you are not doing federally funded research, you have the freedom to choose alternative and sometimes more appropriate members for your IRB.

Other Considerations

- An IRB may not allow any member to participate in the review of any project in which the member has a conflicting interest. That would include researchers involved in the project and administrators involved in the grant applications.

- An IRB may invite individuals with expertise in specific areas to assist in the review of projects that require expertise that is not represented sufficiently on the IRB; however, they may not vote with the IRB.

- By definition, the IRB is a board, not a committee. As such, it means that members of an IRB are tasked with rendering decisions about research they review. In contrast, members of standing committees may or may not be tasked with rendering decisions—often, their purpose is to offer recommendations or organize information used to help others make decisions. The appointment process to an IRB often differs from the appointment process to other standing committees, as federal regulations include specific requirements about the membership of an IRB.

Your institution will need to provide adequate staffing for the IRB. You may be able to designate a current employee as the IRB staff person, depending on the person’s current duties and the expected workload for the IRB. Depending on the number of research projects, you may need a full-time staff person for the IRB. Key tasks for staff include:

- Answering questions regarding the IRB process.

- Assisting researchers in completing their IRB proposals.

- Tracking when ongoing research projects are due for their annual review.

- Communicating with the IRB regarding incoming proposals and/or other board responsibilities.

- Maintaining documentation of completed training for IRB members and principal investigators (PIs).

IRB Members

The members of the IRB that come from current faculty and staff may need release time to perform the functions of the IRB. In particular, the chairperson of the IRB will likely have some administrative functions for the IRB and may need the time to perform them. This release time needs to be taken into consideration when considering cost. Additionally, you may choose to provide a stipend or reimburse travel time or mileage to your community representative.

Procedures for IRBs That Meet Federal Requirements

Your IRB will need to establish written procedures so that it is clear how the IRB will function. Before the IRB creates these procedures, considering how the IRB will fulfill its duties will be helpful. The questions below will likely need to be addressed; the answers to the questions will be based on your institutional organization and the anticipated volume of research conducted at your institution that requires IRB review.

Members of an IRB will determine the level of IRB review required for submitted research proposals (e.g., “exempt,” “expedited,” or “full” IRB review). Studies that meet the definition of “research” and that involve human participants may be considered exempt if they meet certain requirements.

A “full” IRB review is required when the research is defined as (a) a systematic investigation, including research development, testing and evaluation, designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge (38 CFR 16.102d); (b) that involves human subjects (i.e., a living person about whom a researcher collects either identifiable private information OR data through an intervention or interaction); and (c) involves greater than minimal risk to those human subjects. A full IRB review usually requires attendance from a quorum of IRB-appointed members.

An “expedited” IRB review is selected when the research is defined as meeting the first two classifications noted above but involves no more than minimal risk to subjects OR is being reviewed strictly for minor changes to previously approved protocols in the research project. An expedited review procedure can be conducted by a subset of reviewers designated by the IRB chairperson from members of the IRB.

An “exempt” IRB review (see Criteria for Exempt Status ) is selected when the research falls into one of the six approved categories of exempt research (45 CFR 46.101 [b]) and is not applicable to research in a covered research category (e.g., FDA regulation - 21 CFR 50.20). Exempt research does not mean that a research project has no review. Rather, for studies that are determined to be exempt, it means that the exemption (and its corresponding category) is documented in the IRB records and that the decision is communicated in writing to the investigator.

Accordingly, one of the first questions to consider is who on the IRB makes the determination that a proposed study is exempt (see Criteria for Exempt Status ). Is the IRB chairperson solely responsible for that determination, or will a subcommittee screen all proposals for exemption?

- How will expedited or administrative review be conducted? Studies that pose minimal risk or proposals that are minor changes to studies that were previously approved by the IRB may not need to undergo a full IRB review.

- How will the IRB conduct initial and continuing review of research proposals? Studies that are ongoing (lasting more than 12 months) should have a follow-up review process at least once every 12 months.

- How will the IRB’s decision be communicated to the PI?

- How will changes in proposed research activity be communicated to the IRB? If the IRB has already approved a proposal, will changes to that proposal require new review?

- How will unanticipated problems that pose subsequent risks to human participants be reported to institutional officials?

- What are the deadlines for submissions, and how often will the IRB meet?

Be sure that you give these kinds of questions some thought up front and then solicit input from those people who are interested in either serving on the IRB or helping with the formation of the IRB. Most likely, you will also need to educate administrators at your institution about IRB regulations and procedures.

Educating IRB Members and Principal Investigators

IRB members and PIs need training and education in research ethics and current research regulations if they are going to be applying for federal funds. Most IRBs will choose to have some record of training, but it can be as innocuous as having researchers affirm that they have read the Belmont Report . If more extensive training is deemed necessary, it may be delivered a number of ways (e.g., a face-to-face class, an online class, a self-paced tutorial). The cost of providing training can vary widely. If you choose to have IRB members and PIs attend a face-to-face class, they need to have the time to participate, and you will need to provide a trainer. Online training costs also vary. There are online training modules that your institution can use for free or purchase and customize (see References and Resources for a list of inexpensive training options). As a psychologist, you may wish to review these training modules, as they are often quite naïve in their treatment of research methodology.

Setting up your own online training also has costs, such as the time of the person designing the website and the time of the experts needed to write the training modules. For institutions with limited time and/or budgets, the OHRP’s " Institutional Review Board Guidebook " is a good place to begin in terms of deciding what material to include in a training course. The key information that needs to be delivered includes:

- The basic ethical principles underlying research with human participants as elucidated in the Belmont Report.

- The federal regulations for the protection of research participants.

- The history and ethics of research with human participants.

Completion of training requirements should be documented and kept on file so that the institution can demonstrate that IRB members and PIs have been provided the relevant information. Although probably not necessary, this documentation can be acquired by requiring that IRB members and PIs take a test after reading all of the material that is provided to them.

Record Keeping

Federal records, whether in hard copy or electronic form, need to be maintained and easily accessible for at least 3 years after the research is completed. You may choose a significantly less cumbersome system for research that is not federally funded. Office space or computer space will need to be allocated for storage. These records include:

- Research proposals, sample consent documents, updates from the researchers, and documentation of unanticipated problems ( as described by OHRP ).

- Minutes of IRB meetings that document who attended; a record of voting; rationale for accepting, rejecting, or requiring changes to research proposals; and, where there is conflict among the IRB members, a summary of the issue and its resolution.

- Copies of communication, including email, between the IRB and researchers.

- List of IRB members, including their degrees, area they represent, relevant experience, and association with the college.

- IRB procedures and forms.

- Evidence of training completion.

How Much Will An IRB Cost?

The cost of the IRB depends on how much research the faculty, staff, and students at your institution are conducting and the nature of the research being conducted. Generally, faculty members serve on IRBs as part of their college service without additional compensation. If the volume of research is relatively low and/or most of the research qualifies as exempt (see Criteria for Exempt Status ), the cost may be minimal. If the volume of research is high and/or the research involves more than minimal risk to participants, the additional record keeping may create greater costs.

Does All Data Collection at Our Institution Require an IRB Review?

Much of the data collected within or on behalf of an institution does not meet the regulatory definition of “research” and, thus, would likely not require IRB review. For example, many institutions often engage in projects that are best defined as quality improvement initiatives or program evaluation. Such projects usually do not meet the regulatory definition of research and thus would not need IRB review. However, if (a) the data being collected meet the regulatory definition of research and (b) the research is done using human participants (see Definitions ), the study does require an IRB review. In addition, if one of the anticipated activities following the study is to disseminate the information, such as in a publication or conference presentation, the study may require an IRB review. When in doubt, the PI should submit an IRB proposal. Remember that the IRB is the institutional authority on research requirements, not the researcher or the institutional administration.

- The Institutional Review Board: A College Planning Guide

Contact Education

- Affiliated Professors

- Invited Researchers

- J-PAL Scholars

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- Code of Conduct

- Initiatives

- Latin America and the Caribbean

- Middle East and North Africa

- North America

- Southeast Asia

- Agriculture

- Crime, Violence, and Conflict

- Environment, Energy, and Climate Change

- Labor Markets

- Political Economy and Governance

- Social Protection

- Evaluations

Research Resources

- Policy Insights

- Evidence to Policy

- For Affiliates

- Support J-PAL

The Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) is a global research center working to reduce poverty by ensuring that policy is informed by scientific evidence. Anchored by a network of more than 900 researchers at universities around the world, J-PAL conducts randomized impact evaluations to answer critical questions in the fight against poverty.

- Affiliated Professors Our affiliated professors are based at 97 universities and conduct randomized evaluations around the world to design, evaluate, and improve programs and policies aimed at reducing poverty. They set their own research agendas, raise funds to support their evaluations, and work with J-PAL staff on research, policy outreach, and training.

- Board Our Board of Directors, which is composed of J-PAL affiliated professors and senior management, provides overall strategic guidance to J-PAL, our sector programs, and regional offices.

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion J-PAL recognizes that there is a lack of diversity, equity, and inclusion in the field of economics and in our field of work. Read about what actions we are taking to address this.

- Initiatives J-PAL initiatives concentrate funding and other resources around priority topics for which rigorous policy-relevant research is urgently needed.

- Events We host events around the world and online to share results and policy lessons from randomized evaluations, to build new partnerships between researchers and practitioners, and to train organizations on how to design and conduct randomized evaluations, and use evidence from impact evaluations.

- Blog News, ideas, and analysis from J-PAL staff and affiliated professors.

- News Browse news articles about J-PAL and our affiliated professors, read our press releases and monthly global and research newsletters, and connect with us for media inquiries.

- Press Room Based at leading universities around the world, our experts are economists who use randomized evaluations to answer critical questions in the fight against poverty. Connect with us for all media inquiries and we'll help you find the right person to shed insight on your story.

- Overview J-PAL is based at MIT in Cambridge, MA and has seven regional offices at leading universities in Africa, Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, Middle East and North Africa, North America, South Asia, and Southeast Asia.

- Global Our global office is based at the Department of Economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. It serves as the head office for our network of seven independent regional offices.

- Africa J-PAL Africa is based at the Southern Africa Labour & Development Research Unit (SALDRU) at the University of Cape Town in South Africa.

- Europe J-PAL Europe is based at the Paris School of Economics in France.

- Latin America and the Caribbean J-PAL Latin America and the Caribbean is based at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

- Middle East and North Africa J-PAL MENA is based at the American University in Cairo, Egypt.

- North America J-PAL North America is based at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the United States.

- South Asia J-PAL South Asia is based at the Institute for Financial Management and Research (IFMR) in India.

- Southeast Asia J-PAL Southeast Asia is based at the Faculty of Economics and Business at the University of Indonesia (FEB UI).

- Overview Led by affiliated professors, J-PAL sectors guide our research and policy work by conducting literature reviews; by managing research initiatives that promote the rigorous evaluation of innovative interventions by affiliates; and by summarizing findings and lessons from randomized evaluations and producing cost-effectiveness analyses to help inform relevant policy debates.

- Agriculture How can we encourage small farmers to adopt proven agricultural practices and improve their yields and profitability?

- Crime, Violence, and Conflict What are the causes and consequences of crime, violence, and conflict and how can policy responses improve outcomes for those affected?

- Education How can students receive high-quality schooling that will help them, their families, and their communities truly realize the promise of education?

- Environment, Energy, and Climate Change How can we increase access to energy, reduce pollution, and mitigate and build resilience to climate change?

- Finance How can financial products and services be more affordable, appropriate, and accessible to underserved households and businesses?

- Firms How do policies affecting private sector firms impact productivity gaps between higher-income and lower-income countries? How do firms’ own policies impact economic growth and worker welfare?

- Gender How can we reduce gender inequality and ensure that social programs are sensitive to existing gender dynamics?

- Health How can we increase access to and delivery of quality health care services and effectively promote healthy behaviors?

- Labor Markets How can we help people find and keep work, particularly young people entering the workforce?

- Political Economy and Governance What are the causes and consequences of poor governance and how can policy improve public service delivery?

- Social Protection How can we identify effective policies and programs in low- and middle-income countries that provide financial assistance to low-income families, insuring against shocks and breaking poverty traps?

Introduction to randomized evaluations

The elements of a randomized evaluation

Teaching resources on randomized evaluations

Resources for researchers new to randomized evaluations

Formalize research partnership and establish roles and expectations

Assessing viability and building relationships

Checklist for launching a randomized evaluation in the United States

Administrative steps for launching a randomized evaluation in the United States

Ethical conduct of randomized evaluations

Institutional Review Board (IRB) proposals

Power calculations

Quick guide to power calculations

Grant proposals

Grant and budget management

Trial registration

Pre-analysis plans

Resources for conducting remote surveys

Introduction to measurement and indicators

Survey design

Repository of measurement and survey design resources

Design and iterate implementation strategy

Define intake and consent process

Randomization

Implementation monitoring

Real-time monitoring and response plans: Creating procedures

Increasing response rates of mail surveys and mailings

Survey programming

Data quality checks

Survey logistics

Surveyor hiring and training

Field team management

Working with a third-party survey firm

Questionnaire piloting

Using administrative data for randomized evaluations

Evaluating technology-based interventions

Data security procedures for researchers

Data cleaning and management

Data visualization

Data analysis

Conducting cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA)

Pre-publication planning and proofing

Data de-identification

Data publication

Communicating with a partner about results

Coding resources for randomized evaluations

Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) review research involving human subjects to ensure that participants are protected from potentially harmful research. This resource provides an overview of the roles of IRBs and ethics guidelines. It also includes practical tips for researchers preparing IRB proposals, including an annotated informed consent checklist, guidance on timeline planning and responding to common concerns of IRBs, and handling unanticipated events. Researchers who are already familiar with the roles of IRBs and obtaining human subjects training certificates may wish to begin at the section "Preparing the proposal."

Important terms

- Institutional Review Board (IRB): Ethics review committee. US requirements often govern the contents and elements of an IRB application, even if you also submit the application to an ethics board somewhere else. All J-PAL funded projects need to pass IRB review at MIT or cede authority to another host institution.

- Common Rule: Shorthand term for the Federal (US) Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects, which outlines the criteria and mechanisms for IRB review of human subjects research.

- Exempt research involves minimal risk and fits under one of the exempt review categories described in the Common Rule. Exempt status means the study is exempted from some (but not all) regulatory review, though not from ethics review, and IRBs may still place conditions on exempt research. It is up to the IRB, not the researcher, to determine whether the study qualifies for exempt status 1 . The revisions to the Common Rule include new categories and clarification of existing categories of exemption. See Human Subjects Decision Chart 2 : “Is the Research Involving Human Subjects Eligible for Exemption Under 45 CFR 46.104(d)?”

- Expedited review involves research with minimal risk and fulfills a set of other criteria listed by the US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Human Research Protections (DHHS OHRP, 2017). Expedited review is carried out by one member of the IRB Committee.

- Full review is required if the protocol is greater than minimal risk and/or does not fall into one of the expedited or exempt review categories, according to both pre-2018 and 2018 regulations. This may happen, for example, when a study targets a vulnerable population. Full review requires that the protocol is discussed by the full Board, which requires a Board meeting (DHHS OHRP 2009 & 2018 ).

- Amendment : You should submit an amendment request to the IRB to make any change to the original protocol. This includes updates to personnel, consent scripts or processes, surveys questions, funding, and participating institutions.

- IRB Authorization Agreements (IAA): Agreements between two IRBs that one of them will take on all reviewing responsibilities for a project for both of them. For example, if a research team includes a principal investigator (PI) at Tufts University and one at Cornell, Cornell can cede reviewing responsibilities to Tufts. DHHS OHRP provides a sample IAA , though many IRBs now process IAAs online via Smart IRB . Please check with your IRB to see which is preferred.

- Adverse event: A violation of IRB protocols or an event during the research that carries the risk of potential harm to the subjects. This includes data breaches. Adverse events must be reported to the IRB.

Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) review research involving human subjects to ensure protection of research participants from potentially harmful research.

Research involving human subjects obtains information through interventions or generates identifiable private information (including bio-specimens). Identifiable information means that the identity of the subject may readily be ascertained or associated with an individual. Private information refers to behavior taking place in a context in which an individual can reasonably expect no observation, recording, or information that the individual provided for a specific purpose and can reasonably expect will not be made public (e.g., a medical record).

The "Common Rule" is the popular term for the Federal (US) Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects , 45 CFR part 46 , which outlines the criteria and mechanisms for IRB review of human subjects research. The revised Common Rule went into effect January 21, 2019. All new protocols submitted after January 21, 2019, are required to comply with the revised requirements. It is up to individual IRBs, however, whether to apply the previous or revised version of the regulations to ongoing studies that were submitted before that transition date (DHHS OHRP 2019a).

J-PAL IRB requirements

All research projects that are either funded or implemented by J-PAL must be reviewed by the IRB at the host institutions of all PIs on the project and adhere to all policies and protocols approved by the IRB. Effective all rounds of J-PAL funding starting October 1, 2022, and for all projects where data collection is supposed to start after January 1, 2023, at least one of the IRBs reviewing the project must have status as an IRB Organization (IORG). An IRB’s status can be found by consulting the database of IORGs .