- PhD Failure Rate – A Study of 26,076 PhD Candidates

- Doing a PhD

The PhD failure rate in the UK is 19.5%, with 16.2% of students leaving their PhD programme early, and 3.3% of students failing their viva. 80.5% of all students who enrol onto a PhD programme successfully complete it and are awarded a doctorate.

Introduction

One of the biggest concerns for doctoral students is the ongoing fear of failing their PhD.

After all those years of research, the long days in the lab and the endless nights in the library, it’s no surprise to find many agonising over the possibility of it all being for nothing. While this fear will always exist, it would help you to know how likely failure is, and what you can do to increase your chances of success.

Read on to learn how PhDs can be failed, what the true failure rates are based on an analysis of 26,067 PhD candidates from 14 UK universities, and what your options are if you’re unsuccessful in obtaining your PhD.

Ways You Can Fail A PhD

There are essentially two ways in which you can fail a PhD; non-completion or failing your viva (also known as your thesis defence ).

Non-completion

Non-completion is when a student leaves their PhD programme before having sat their viva examination. Since vivas take place at the end of the PhD journey, typically between the 3rd and 4th year for most full-time programmes, most failed PhDs fall within the ‘non-completion’ category because of the long duration it covers.

There are many reasons why a student may decide to leave a programme early, though these can usually be grouped into two categories:

- Motives – The individual may no longer believe undertaking a PhD is for them. This might be because it isn’t what they had imagined, or they’ve decided on an alternative path.

- Extenuating circumstances – The student may face unforeseen problems beyond their control, such as poor health, bereavement or family difficulties, preventing them from completing their research.

In both cases, a good supervisor will always try their best to help the student continue with their studies. In the former case, this may mean considering alternative research questions or, in the latter case, encouraging you to seek academic support from the university through one of their student care policies.

Besides the student deciding to end their programme early, the university can also make this decision. On these occasions, the student’s supervisor may not believe they’ve made enough progress for the time they’ve been on the project. If the problem can’t be corrected, the supervisor may ask the university to remove the student from the programme.

Failing The Viva

Assuming you make it to the end of your programme, there are still two ways you can be unsuccessful.

The first is an unsatisfactory thesis. For whatever reason, your thesis may be deemed not good enough, lacking originality, reliable data, conclusive findings, or be of poor overall quality. In such cases, your examiners may request an extensive rework of your thesis before agreeing to perform your viva examination. Although this will rarely be the case, it is possible that you may exceed the permissible length of programme registration and if you don’t have valid grounds for an extension, you may not have enough time to be able to sit your viva.

The more common scenario, while still being uncommon itself, is that you sit and fail your viva examination. The examiners may decide that your research project is severely flawed, to the point where it can’t possibly be remedied even with major revisions. This could happen for reasons such as basing your study on an incorrect fundamental assumption; this should not happen however if there is a proper supervisory support system in place.

PhD Failure Rate – UK & EU Statistics

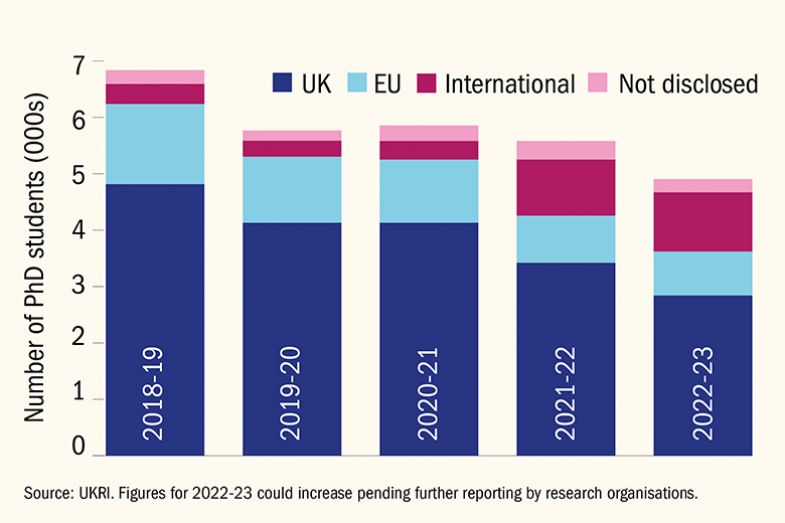

According to 2010-11 data published by the Higher Education Funding Council for England (now replaced by UK Research and Innovation ), 72.9% of students enrolled in a PhD programme in the UK or EU complete their degree within seven years. Following this, 80.5% of PhD students complete their degree within 25 years.

This means that four out of every five students who register onto a PhD programme successfully complete their doctorate.

While a failure rate of one in five students may seem a little high, most of these are those who exit their programme early as opposed to those who fail at the viva stage.

Failing Doesn’t Happen Often

Although a PhD is an independent project, you will be appointed a supervisor to support you. Each university will have its own system for how your supervisor is to support you , but regardless of this, they will all require regular communication between the two of you. This could be in the form of annual reviews, quarterly interim reviews or regular meetings. The majority of students also have a secondary academic supervisor (and in some cases a thesis committee of supervisors); the role of these can vary from having a hands-on role in regular supervision, to being another useful person to bounce ideas off of.

These frequent check-ins are designed to help you stay on track with your project. For example, if any issues are identified, you and your supervisor can discuss how to rectify them in order to refocus your research. This reduces the likelihood of a problem going undetected for several years, only for it to be unearthed after it’s too late to address.

In addition, the thesis you submit to your examiners will likely be your third or fourth iteration, with your supervisor having critiqued each earlier version. As a result, your thesis will typically only be submitted to the examiners after your supervisor approves it; many UK universities require a formal, signed document to be submitted by the primary academic supervisor at the same time as the student submits the thesis, confirming that he or she has approved the submission.

Failed Viva – Outcomes of 26,076 Students

Despite what you may have heard, the failing PhD rate amongst students who sit their viva is low.

This, combined with ongoing guidance from your supervisor, is because vivas don’t have a strict pass/fail outcome. You can find a detailed breakdown of all viva outcomes in our viva guide, but to summarise – the most common outcome will be for you to revise your thesis in accordance with the comments from your examiners and resubmit it.

This means that as long as the review of your thesis and your viva examination uncovers no significant issues, you’re almost certain to be awarded a provisional pass on the basis you make the necessary corrections to your thesis.

To give you an indication of the viva failure rate, we’ve analysed the outcomes of 26,076 PhD candidates from 14 UK universities who sat a viva between 2006 and 2017.

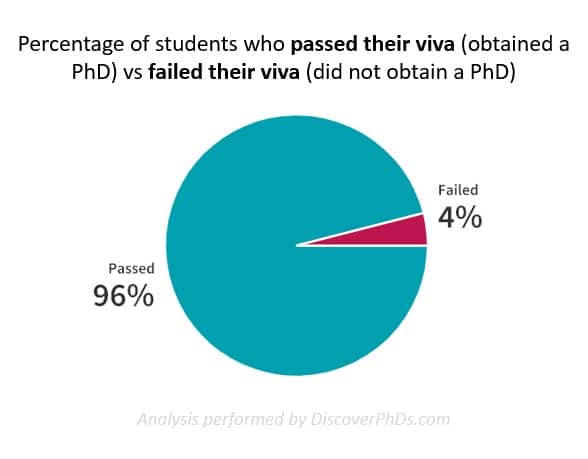

The analysis shows that of the 26,076 students who sat their viva, 25,063 succeeded; this is just over 96% of the total students as shown in the chart below.

Students Who Passed

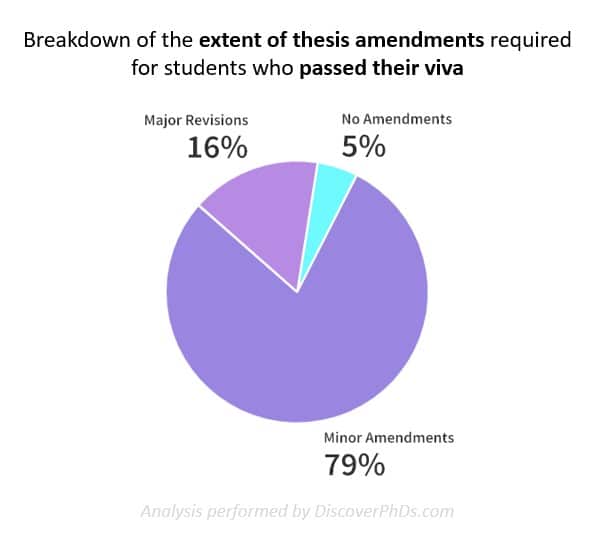

The analysis shows that of the 96% of students who passed, approximately 5% required no amendments, 79% required minor amendments and the remaining 16% required major revisions. This supports our earlier discussion on how the most common outcome of a viva is a ‘pass with minor amendments’.

Students Who Failed

Of the 4% of unsuccessful students, approximately 97% were awarded an MPhil (Master of Philosophy), and 3% weren’t awarded a degree.

Note : It should be noted that while the data provides the student’s overall outcome, i.e. whether they passed or failed, they didn’t all provide the students specific outcome, i.e. whether they had to make amendments, or with a failure, whether they were awarded an MPhil. Therefore, while the breakdowns represent the current known data, the exact breakdown may differ.

Summary of Findings

By using our data in combination with the earlier statistic provided by HEFCE, we can gain an overall picture of the PhD journey as summarised in the image below.

To summarise, based on the analysis of 26,076 PhD candidates at 14 universities between 2006 and 2017, the PhD pass rate in the UK is 80.5%. Of the 19.5% of students who fail, 3.3% is attributed to students failing their viva and the remaining 16.2% is attributed to students leaving their programme early.

The above statistics indicate that while 1 in every 5 students fail their PhD, the failure rate for the viva process itself is low. Specifically, only 4% of all students who sit their viva fail; in other words, 96% of the students pass it.

What Are Your Options After an Unsuccessful PhD?

Appeal your outcome.

If you believe you had a valid case, you can try to appeal against your outcome . The appeal process will be different for each university, so ensure you consult the guidelines published by your university before taking any action.

While making an appeal may be an option, it should only be considered if you genuinely believe you have a legitimate case. Most examiners have a lot of experience in assessing PhD candidates and follow strict guidelines when making their decisions. Therefore, your claim for appeal will need to be strong if it is to stand up in front of committee members in the adjudication process.

Downgrade to MPhil

If you are unsuccessful in being awarded a PhD, an MPhil may be awarded instead. For this to happen, your work would need to be considered worthy of an MPhil, as although it is a Master’s degree, it is still an advanced postgraduate research degree.

Unfortunately, there’s a lot of stigma around MPhil degrees, with many worrying that it will be seen as a sign of a failed PhD. While not as advanced as a PhD, an MPhil is still an advanced research degree, and being awarded one shows that you’ve successfully carried out an independent research project which is an undertaking to be admired.

Finding a PhD has never been this easy – search for a PhD by keyword, location or academic area of interest.

Additional Resources

Hopefully now knowing the overall picture your mind will feel slightly more at ease. Regardless, there are several good practices you can adopt to ensure you’re always in the best possible position. The key of these includes developing a good working relationship with your supervisor, working to a project schedule, having your thesis checked by several other academics aside from your supervisor, and thoroughly preparing for your viva examination.

We’ve developed a number of resources which should help you in the above:

- What to Expect from Your Supervisor – Find out what to look for in a Supervisor, how they will typically support you, and how often you should meet with them.

- How to Write a Research Proposal – Find an outline of how you can go about putting a project plan together.

- What is a PhD Viva? – Learn exactly what a viva is, their purpose and what you can expect on the day. We’ve also provided a full breakdown of all the possible outcomes of a viva and tips to help you prepare for your own.

Data for Statistics

- Cardiff University – 2006/07 to 2016/17

- Imperial College London – 2006/07 to 2016/17

- London School of Economics (LSE) – 2006/07 to 2015/16

- Queen Mary University of London – 2009/10 to 2015/16

- University College London (UCL) – 2006/07 to 2016/17

- University of Aberdeen – 2006/07 to 2016/17

- University of Birmingham – 2006/07 to 2015/16

- University of Bristol – 2006/07 to 2016/17

- University of Edinburgh – 2006/07 to 2016/17

- University of Nottingham – 2006/07 to 2015/16

- University of Oxford – 2007/08 to 2016/17

- University of York – 2009/10 to 2016/17

- University of Manchester – 2008/09 to 2017/18

- University of Sheffield – 2006/07 to 2016/17

Note : The data used for this analysis was obtained from the above universities under the Freedom of Information Act. As per the Act, the information was provided in such a way that no specific individual can be identified from the data.

Browse PhDs Now

Join thousands of students.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

- Plans for new private student accommodation rejected for a second time

- New report confirms that HMP Durham is the most overcrowded Prison in England and Wales

- University buildings close ahead of planned riots in city centre

- Mary Foy sends letter to Network Rail about suicides at Durham stations

- Durham students to compete in Paris 2024 Olympics

Durham's Official Student Newspaper

One in four PhD students drop out

By Luke Payne

One in four Durham PhD students leave study without achieving their target doctorate degree. The data, acquired through a Palatinate Freedom of Information request, reveals performance is particularly poor in certain departments, with Computer Science, Education, and History performing amongst the worst in their respective faculties.

Palatinate received data from 10 UK universities counting the number of PhD students who left study between the 2015/16 and 2019/20 academic years and how many of those students received a doctoral degree. The figures include some medical students and other doctoral awards, while a small minority of students leave study due to transferring to another university.

At Durham, only 74% of doctoral students, who left study over the five-year period, received doctorates. This figure compares poorly with rival institutions such as Glasgow and Imperial where figures are 93% and 91%. Only two of the 10 institutions surveyed had poorer PhD success rates based on the raw data. These were Strathclyde (68%) and Liverpool (65%).

In response to the article, Durham University disputed Palatinate’s findings and said the true success rate was closer to 81%, after taking into account students transferring between institutions. It further claimed that it was not accurate to compare its data with other UK universities.

In the Faculty of Science, a number of Durham departments are very successful at ensuring their PhD students graduate with doctoral degrees. Over 90% of Physics, Mathematics and Earth Sciences PhD students graduate with doctorates.

By comparison, only 73% of Engineering and 69% of Computer Science students leave with doctorates. These rates are 10 to 20 percentage points behind comparable departments at Glasgow, Imperial, York and Leeds.

A Durham Physics PhD student told Palatinate that their department had a “very strong sense of community and provided many activities, both academic and social. This really helps students to feel less isolated, which I think can be a problem in other departments.”

“Only 55% of Durham’s Education PhD students graduate with doctorates”

In the Faculty of Social Sciences and Health, less than two-thirds of Durham PhD students within the Sociology Department, School of Government and International Relations and the School of Education graduate with doctorates.

Only 55% of Durham’s Education PhD students graduate with doctorates compared with 86% at the University of Leeds and 81% at the University of Glasgow. This equated to 51 Durham Education PhD students leaving with non-doctoral degrees (such as Research Masters) and 36 leaving with no degree over the past five years.

Within Arts and Humanities, the success of PhD students studying within the Theology & Religion, History and Classics and Ancient History departments was less than 73%.

In their response to the article, Durham University provided some explanation of why some departments’ PhD students may be struggling to achieve doctoral degrees.

“A number of our disciplines (Education, Theology and Religion and Business/Economics/Management) have a significant proportion of mature students returning to higher education… financial and life challenges and changes for these students tend to contribute to withdrawals.

“Science research is often conducted in teams whereas, in other disciplines, postgraduate researchers tend to work alone on their individual research topic. Differences in the proportion of part-time, mature, international and self-funded students between disciplines also contribute to differing outcomes.

“The University, through its Research Degrees Committee, analyses thesis submission and withdrawal data annually. Where a department has a submission rate that is lower… departments are required to review the data and report on their action plans.

“Recently departments have addressed this issue through a number of measures across the student journey that have shown positive results in improving submission rates. In particular, departments have reviewed and enhanced their recruitment practices and processes to support students through annual progress reviews and training.”

“It makes me concerned that the department really does not value its postgraduate researchers”

Not all students are satisfied that sufficient progress is being made to support PhD students during their programmes. Upon learning of Palatinate’s findings, a Durham Engineering PhD student provided this comment:

“It was disappointing to hear that only 73% of Engineering PhD students receive a doctorate. It makes me concerned that the department really does not value its postgraduate researchers, especially after very little support has been provided during virtual working since the start of the pandemic.

“Many PhD colleagues in Engineering haven’t had any additional support or check-ins from supervisors – if anything, it has subsided. It makes me wonder if the general lack of any community amongst Engineering PhD students and staff contributes to the higher drop-out rates.

“I envy other departments which have reading groups, specialised research communities and department organised socials. This lack of support has made me feel lonely, frustrated and underappreciated for the research and teaching contributions my PhD colleagues and I make.”

Image: Michal Jarmoluk via Pixabay

- ← Another letter to my past self

- £1m+ individual donors to Durham revealed →

More by this author

Durham PhD theses sold on Amazon without authors’ consent

Common room finances reveal £170,000 gap in profits

Left to rot? Durham’s forgotten monuments

Proportion of durham first class graduates more than doubled in last decade.

Breaking: Plans for new student accommodation block near South & John Snow Colleges approved

University drafts proposals to spend millions on homes of College Principals

Donate to palatinate.

Welcome to Palatinate’s website. We rely on readers’ generosity to keep producing award-winning journalism and provide media training opportunities to our team of more than 100 students. Palatinate has produced some of the biggest names in British media, including Jeremy Vine, Sir Harold Evans and George Alagiah. Every contribution to Palatinate is an investment into the future of journalism.

Graduate Statistics for the UK

Graduates make a huge impact in the UK economy, job market and workplace, so we wanted to record all of the facts and figures surrounding graduates in one place.

We’ve scoured a huge amount of UK graduate information sources to provide you with all of the latest graduate statistics.

If you want to know the current number of graduates in the UK, the average graduate salary, or which universities have the lowest drop-out rates, and more… It’s all below.

|

|

|

|

Key UK Graduate Statistics

- As of 2023 , estimates show there will be 36.4 million graduates in the UK .

- Undergraduate figures increased by 0.4% from 527,070 in 2021 to 529,360 in 2022.

- Recent graduates (2020 onwards) currently face an unemployment rate of 12.7% , which equates to over 96,000 unemployed graduates each academic year.

- Universities in the UK awarded 133,995 first-class honours qualifications in 2022 , a 14.1% decrease from the 155,955 awarded in 2021.

- Business studies graduates achieved the highest number of qualified degrees, with a total of 175,670 graduates in 2022.

- Women made up 57.6% of higher education graduates in 2022, with 530,170 women graduating.

- On average, 6 in 100 (6.3%) students in the UK drop out of university, an average of 48,548 students each year since 2014.

- Male graduates typically at the age of 25 earn 5% more than the average female graduate

- The average student loan debt is £46,150 in England and takes and average of 29 years and 4 months to pay off.

Get the latest stats and studies delivered to your inbox

Get our studies on jobs, salaries, recruitment and more as soon as they are published, number of graduates per year in the uk.

In the UK, there are over 800,000 undergraduates and postgraduates leaving higher education each year. Importantly, this is the number of people graduating and does not include those who do not successfully complete their degree .[1]

“There were an estimated 36.4 million graduates in the UK in 2022”

In 2017 (the latest study of this kind), 42% of adults aged 21 to 64 years held a graduate degree, meaning there were over 34 million graduates then. [2] Using annual graduate figures, estimates would show that the figure in 2021 would be around 36.4 million graduates in the country.

Undergraduate numbers have steadily increased in the 2010s. The following graph shows this increase in the number of graduates per year in the UK.

Undergraduate figures increased by 7% from 492,355 in 2019/20 to 527,070 in 2020/21.

However, from 2020/21 to the 2021/22 academic year, undergraduate figures increased by only 0.4% from 527,070 to 529,360.

Similar to undergraduates, postgraduate numbers also increased in 2020/21 by 12%. The sharp increase in both undergraduate and postgraduate figures in 2021 is likely due to the drop seen in the 2019/20 year as a result of the pandemic. Postgraduate numbers saw a similar increase in 2021/22 with a 12.9% increase on the previous year, from 345,700 to 390,585.

Gender split of graduates in the UK

The table below shows comparisons of UK graduates by gender from 2019 to 2022: [34]

| Academic Year | Female | Male | Other |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019/20 | 466,790 | 332,925 | 1,000 |

| 2020/21 | 511,675 | 359,650 | 1,440 |

| 2021/22 | 530,170 | 387,690 | 2,080 |

Female graduates made the largest contribution to the total number of graduates over the previous five years. In fact, females made up 57.6% of higher education students in 2021/22, totalling 530,170. The number of females studying in higher education has increased by 13.5% since 2019/20.

Male numbers have also steadily increased from 332,925 in 2019/20 to 387,690 in 2021/22, a 16.4% increase in male graduates. Graduates who identify as other genders have also increased since 2019/20 from 1,000 to 2,080 in total. A large increase of around 108%. [34]

Which course has the highest number of graduates?

In the UK, typically business studies is the course with the highest number of graduates at a total of 141,125 graduates achieving a degree in this selected field in 2020. In second place, science subjects allied to medicine and biological sciences awarded 159,520 students with a degree in that same year. [1]

| Subject | 2022 Graduates |

|---|---|

| Business and management | 175,670 |

| Subjects allied to medicine | 99,570 |

| Social sciences | 92,560 |

| Design, and creative and performing arts | 65,380 |

| Education and teaching | 65,355 |

| Engineering and technology | 60,345 |

| Law | 48,790 |

| Biological and sport sciences | 36,175 |

| Computing | 50,465 |

| Psychology | 40,810 |

| Language and area studies | 28,405 |

| Historical, philosophical and religious studies | 27,345 |

| Architecture, building and planning | 22,525 |

| Medicine and dentistry | 21,535 |

| Media, journalism and communications | 19,250 |

| Physical sciences | 19,000 |

| Mathematical sciences | 15,900 |

| Geography, earth and environmental studies (natural sciences) | 10,675 |

| Agriculture, food and related studies | 6,265 |

| Combined and general studies | 6,800 |

| Geography, earth and environmental studies (social sciences) | 4,655 |

| Veterinary sciences | 2,480 |

At the other end of the scale, veterinary science courses typically have the fewest number of graduates in the UK with just 2,480 graduates entering the market in 2022.

Undergraduate enrolment by ethnicity

The vast majority (71.5%) of undergraduates are white, while Asian students account for the second-largest demographic at 12.9%. The third-largest ethnicity demographic in 2022 was Black students (8.5%), followed by just under 1 in 20 (4.8%) who were from mixed ethnic backgrounds, as well as 2.3% who were from other minority ethnic groups.

Over a six-year period prior to 2022, the percentage of Asian, Black, Mixed and other ethnic groups beginning an undergraduate course has increased from 24% to 28.5%. [3]

Black students have seen the biggest increase in postgraduate study as figures rose from 5.8% in 2010/11 to 8.3% in 2019/20. Postgraduate entrants who were Asian rose by 2.4% from 9.4% over the same period.[4]

Graduate achievements by ethnicity

A higher proportion of white graduates (36.1%) complete their degree with a first-class qualification than any other ethnicity, closely followed by those with mixed ethnicity (31.3%).

The data below breaks down degree achievement by ethnicity:

| Asian | 27.5% | 47.3% | 25.2% |

| Black | 17.3% | 45.4% | 37.3% |

| Mixed | 31.3% | 48.7% | 20% |

| White | 36.1% | 46.9% | 17% |

| Other | 25.1% | 47.6% | 27.3% |

According to the UK government, the percentage gap decreased from 26.3% to 20.0% between white and Black graduates getting a first-class or upper second degree from 2015 to 2022. The data suggests the trend is shifting but could take many more years to get to similar levels. [5]

Student dropout rates in the UK

On average, 6 in 100 (6.3%) students in the UK drop out of university. Since 2007/08, dropout rates have decreased by 1.1%, from 7.3% in 2008, to 6.2% a decade later. [6] This would mean an average of 48,548 students each year drop out.

Universities with the highest dropout rates in the UK

The graph below shows the universities with the highest dropout rates:

| Rank | University | Percentage No Longer in Higher Education |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Arden University | 32.30% |

| 2 | Point Blank Music School | 19.20% |

| 3 | SAE Education Limited | 18.50% |

| 4 | London Metropolitan University | 16.00% |

| 5 | Richmond, The American International University in London | 15.80% |

| 6 | University of Bedfordshire | 15.70% |

| 7 | The London Institute of Banking & Finance | 15.70% |

| 8 | University Centre Peterborough | 14.60% |

| 9 | University of the Highlands and Islands | 14.00% |

| 10 | Regent's University London Limited | 13.70% |

The university with the highest dropout rate as of the 2019/20 year is Arden University with a dropout rate of 32.3%. This is followed by Point Blank Music School at 19.2% [7]

Universities with the lowest dropout rates

The universities with the lowest dropout rates in the country as of 2019/20 are the Royal Veterinary College (0.4%), the University of Cambridge (0.6%), and the University of St Andrews (0.6%). [7]

| Rank | University | Percentage of Students No Longer in Higher Education |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Royal Veterinary College | 0.40% |

| 2 | The University of Cambridge | 0.60% |

| 3 | The University of St Andrews | 0.60% |

| 4 | The University of Oxford | 0.90% |

| 5 | The University of Durham | 1.30% |

| 6 | The University of Bristol | 1.50% |

| 7 | Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine | 1.50% |

| 8 | The University of Birmingham | 1.60% |

| 9 | London School of Economics and Political Science | 1.60% |

| 10 | Glasgow School of Art | 1.70% |

Studies show that the majority of universities with the lowest dropout rates can be found in the top 20 on the Complete University Guide’s league table. St George’s and the University of London are just two universities that have one of the lowest dropout scores and don’t sit in the top 20 league table.

Undergraduate courses with the highest dropout rates

IT and computing degrees, such as computer science, have the highest dropout rates with 9.2% not making it.

Undergraduate courses with the highest dropout rates were as follows: [7]

| Rank | Subject | Dropout Rate |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Computer sciences | 9.20% |

| 2 | Business and administrative studies | 8.60% |

| 3 | Mass communications and documentation | 7.60% |

| 4 | Creative arts and design | 7.60% |

| 5 | Subjects allied to medicine | 7.50% |

| 6 | Combined subjects | 7.2 |

| 7 | Agriculture and related subjects | 7% |

| 8 | Engineering and technology | 7% |

| 9 | Architecture, building and planning | 6.90% |

| 10 | Biological sciences | 6.80% |

In 2020, 29,360 students in the UK deferred their studies for a gap year due to the pandemic, a 9.4% increase compared to 2019. [8]

Which universities have the best grades in the UK?

Overall, universities in the UK awarded 133,995 first-class honours qualifications in 2022, a 14.1% decrease from the previous year where 155,955 were awarded.

We ranked data based on which universities awarded the most first class honours awards in 2022 below, with the University of Manchester coming out on top with 2,855 given. [9]

Universities with the most first-class degrees in the UK

| Rank | University | First-class degrees (2022) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | The University of Manchester | 2,855 |

| 2 | The University of Leeds | 2,750 |

| 3 | The Manchester Metropolitan University | 2,730 |

| 4 | University of Nottingham | 2,575 |

| 5 | University College London | 2,550 |

| 6 | The Open University | 2,505 |

| 7 | Coventry University | 2,485 |

| 8 | King's College London | 2,100 |

| 9 | The University of Birmingham | 2,050 |

| 10 | The University of Exeter | 2,050 |

The University of Leeds ranked second awarding 2,750 first-class honours classifications.

Overall, 197,345 upper second class honours qualifications were awarded in 2020/2021, a 4.1% increase compared to the year before.

UK universities with top employment figures

The University of Cambridge has the highest employability ranking for the 2022 academic year, with the University of Oxford coming in second.

The table below shows the UK universities with the highest employability rank in the 2022 academic year. [32]

| University | UK Employability Rank (2022) |

|---|---|

| University of Cambridge | 1 |

| University of Oxford | 2 |

| Imperial College London | 3 |

| London School of Economics and Political Science | 4 |

| London Business School | 5 |

| King's College London | 6 |

| University of Manchester | 7 |

| UCL | 8 |

| University of Edinburgh | 9 |

| University of St Andrews | 10 |

| University of Birmingham | 11 |

| Durham University | 12 |

| Cardiff University | 13 |

| Brunel University London | 14 |

Which universities have the best career prospects?

Five institutions based in London ranked in the top ten for the best career prospects in the UK. Imperial College London scored the highest (95%) based on the success of graduates after leaving university with the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) scoring slightly lower at 91%. [10]

The graph below shows the top ten universities in the UK ranked by their career prospects:

Best UK universities for business founders

Whilst many graduates full of ambition go on to secure a full-time role, many also opt for a different path and become business founders. The best UK university for the proportion of business founders was found to be the University of the Arts London (15.83%), followed by LSE (14.03%).[11]

The table below shows the top ten universities for producing business founders ranked by the percentage of founders that came from there:

| University of the Arts London | 15.83% |

| London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) | 14.03% |

| Goldsmiths, University of London | 12.25% |

| Falmouth University | 12.09% |

| University of Oxford | 12.06% |

| University of Cambridge | 12% |

| Soas University of London | 11.47% |

| University College London (UCL) | 10.41% |

| University for the creative arts | 10.13% |

| Middlesex University [E] | 10.11% |

The percentage of business founders is made from the number of graduates from that institution who go on to become business founders.

Graduate schemes: what are they?

Graduate schemes are designed to help someone gain industry experience whilst earning a competitive salary. The aim of the scheme is to allow new candidates to explore various areas of a business in order to broaden their knowledge whilst following a structured program, leading to a successful career for many.

Companies such as Google, KMPG, NHS, and the UK Civil Service are just a few of many large corporations offering graduate schemes on a yearly basis in Britain.

Who is eligible for a graduate scheme?

Graduate schemes require a minimum grade in order to be considered for the role. In most cases, a 2.1 or higher is the grade most companies will look for when recruiting new candidates .

How many graduate schemes do students apply for?

Recent reports show that students on average were applying up to 29 graduates schemes with different employers.

“The NHS receives an average of 85 applications for every graduate position”

In terms of NHS graduate schemes, reports show the public health service receives around 85 applications for each graduate position; they have 17,000 applications for just 200 spaces. [12]

On average, reports show that overall graduate job applications have increased by 41% from 2020 to 2021. [13]

What is the average graduate scheme salary?

The average graduate scheme salary is £30,362 and ranges between £25,000 and £32,000 according to Glassdoor [14] .

If you require more information on this topic, our research team has also compiled a complete analysis of graduate salaries in the UK including a comparison to non-graduates and a variety of job-specific data.

How much do graduate jobs pay by region?

As you would expect, London pays the highest starting salary for graduates at £31,423, with the East of England following at £26,216. In the UK, Northern Ireland pays the least at an average of £22,143 to start. [15]

The table below shows the average starting salary for graduates around the UK:

| London | £31,423 |

| East of England | £26,216 |

| South East | £26,180 |

| South West | £25,722 |

| Scotland | £25,476 |

| North East | £25,034 |

| West Midlands | £24,877 |

| North West | £24,762 |

| Wales | £24,758 |

| East Midlands | £24,617 |

| Yorkshire and The Humber | £24,448 |

Graduate starting salaries can clearly vary with a clear financial divide between the North and South of the UK. The total average salary in the UK is £29,669 as of 2023, therefore, only London graduates meet and exceed this.

Which graduate schemes pay the highest?

The highest-paid graduate scheme in the UK is a private finance role for Rothschilds, with a salary of £65,000 followed by investment banking positions with J.P. Morgan, who will pay graduates £58,000 a year. [16]

| Rothschilds | Private Finance | £65,000 |

| J. P. Morgan | Investment Banking | £58,000 |

| Goldman Sachs | Investment Banking | £52,000 |

| The Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) | Investment Banking | £54,000 |

Most commonly, the highest-paid graduate schemes sit within finance and banking and often exceed the average amount by tens of thousands of pounds.

How many undergraduates gain work experience?

Studies show that the majority (64%) of undergraduates undertake some period of unpaid work experience, with 41% of this group doing so for at least one month. [17]

In 2020, that would mean around 512,227 (64%) students did some period of work experience before entering the job market as graduates, and 210,014 did so unpaid.

“Over 210,000 students work unpaid during their degrees each year”

A separate study from 1995 showed that 82% of undergraduates had some work experience during their degree, comparatively this could indicate modern students are less likely to do work experience. [18]

In terms of employability, most (94%) interns are offered job roles once they have completed work experience, therefore, it is a valuable decision for students to add to their CV. [17]

How long does it take graduates to secure a job?

Securing a job role is a process many students start prior to graduating with many beginning applications in an attempt to begin full-time work as soon as possible once qualified.

Studies show the time it takes for graduates to secure a job varies anywhere between three to 18 months.

Graduate outcomes and employment figures

In 2023, 82% of UK graduates from 2021 were in full-time or part-time employment. That’s around 314,450 graduates employed from that year. [33]

“A typical graduate cohort will see around 82% enter into employment or further studies within a year”

Below is an example of typical graduate outcomes showing the many different paths students choose once they have completed their degrees. The data refers to the graduates who graduating in 2020 and what they were doing when data was analysed in 2022.

| Graduate Outcome | Number of Graduates |

|---|---|

| Full-time employment | 230,595 |

| Part-time employment | 43,785 |

| Unknown pattern of employment | 2,610 |

| Voluntary or unpaid work | 4,825 |

| Employment and further study | 42,330 |

| Full-time further study | 33,395 |

| Part-time further study | 2,260 |

| Unknown pattern of further study | 290 |

| Other including travel, caring for someone or retired | 19,530 |

| Unemployed and due to start work | 4,275 |

| Unemployed and due to start further study | 1,340 |

| Unemployed | 18,605 |

Using 2021 graduates the data shows a typical outcome for a year’s cohort of students: the majority 89% are in some form of education or employment, a further 5% go into caring for loved ones and/or travel, while the remaining 5% are unemployed, or unknown.

Degrees with the highest employment in the UK

Degrees related to professional services, tech , and science, had the highest percentage of high-skilled graduates employed in the UK at 93%, closely followed by information and communication professionals (90%).[19] Therefore, the degrees with the highest employment in the UK, are likely those in I.T., tech, and science related fields.

Below is a table which displays the percentage of graduates and/or postgraduates working in various professional industries by the level of skill, giving some indication of employment by degree subject:

| Professional, scientific and technical activities | 93% | 6% | 1% |

| Information and communication | 90% | 5% | 4% |

| Education | 88% | 12% | 1% |

| Mining and quarrying | 87% | 8% | 4% |

| Human health and social work activities | 83% | 16% | 1% |

| Public administration and defence; compulsory social security | 82% | 15% | 2% |

| Activities of extraterritorial organisations and bodies | 82% | 16% | 2% |

| Manufacturing | 80% | 13% | 8% |

| Construction | 77% | 17% | 6% |

| Real estate activities | 77% | 19% | 5% |

| Water supply; sewerage, waste management and remediation activities | 75% | 15% | 10% |

| Financial and insurance activities | 75% | 20% | 5% |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 69% | 21% | 10% |

| Other service activities | 66% | 29% | 5% |

| Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply | 64% | 14% | 21% |

| Administrative and support service activities | 56% | 24% | 20% |

| Transportation and storage | 41% | 21% | 38% |

| Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles | 34% | 8% | 58% |

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 33% | 29% | 38% |

| Accommodation and food service activities | 17% | 16% | 67% |

| Activities of households as employers; undifferentiated goods-and services-producing activities of households for own use | 7% | 91% | 2% |

9 in 10 (90%) postgraduates who completed their course in 2018/2019 were in high-skilled jobs in 2021. In comparison to this, undergraduates equated to 69% suggesting that postgraduate study makes a prospective employee more likely to be hired.

How many graduates are self-employed?

In 2021, 13,275 graduates (from 2018 onwards) were self-employed , using graduate figures, that would mean only 0.42% of graduates from four academic years became self-employed after graduating.[19]

The table below demonstrates graduate numbers (from two academic years) for self-employment, and those running their own business, or working on creating projects.

| Region | Self-employed/ freelance | Running own business | Developing a creative portfolio | Multiple |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| England | 11,400 | 4,360 | 16,760 | 11,735 |

| Wales | 550 | 200 | 940 | 615 |

| Scotland | 880 | 335 | 1,270 | 950 |

| Northern Ireland | 420 | 130 | 730 | 445 |

| Other UK | 25 | 10 | 35 | 30 |

| Total UK | 13,275 | 5,035 | 19,740 | 13,770 |

What is the average graduate salary?

The average graduate salary in the UK is £30,000 and has been this way since 2015. As we’ve discussed, this varies per region, and graduate schemes often inflate the average when compared to an entry-level role outside of such schemes.

Data from the UK government states that as of 2022, the median nominal graduate salary in the UK is £38,500, however, when adjusted for inflation, the median real-terms salary for graduates is £26,500. [30]

UK graduate salaries per subject area

Science-based subjects such as medicine, dentistry, subjects allied to medicine, biological science, and veterinary sciences pay the highest salary to graduates who achieve a first-class degree and are highly skilled with starting salaries ranging between £31,000 to £35,000. [19]

A medium skilled dentistry role could be a dental assistant, while the high-skilled role in the field could be a dentist. This designation is not a choice we have made in the analysis and comes from the various data sources.

| Medicine & dentistry | £35,000 | £18,500 | N/A |

| Subjects allied to medicine | £25,000 | £19,000 | £18,000 |

| Biological sciences | £23,000 | £18,500 | £18,000 |

| Veterinary science | £31,000 | N/A | N/A |

| Agriculture & related subjects | £23,500 | £18,500 | £19,000 |

| Physical sciences | £25,000 | £19,500 | £18,000 |

| Mathematical sciences | £28,000 | £20,500 | £17,000 |

| Computer science | £27,000 | £20,000 | £18,000 |

| Engineering & technology | £28,000 | £22,000 | £18,000 |

| Architecture, building & planning | £24,000 | £20,000 | £18,000 |

| Social studies | £26,000 | £20,000 | £18,000 |

| Law | £22,000 | £19,500 | £18,000 |

| Business & administrative studies | £25,000 | £20,500 | £18,000 |

| Mass communications & documentation | £21,000 | £19,500 | £17,000 |

| Languages | £24,000 | £19,500 | £18,000 |

| Historical & philosophical studies | £24,500 | £19,000 | £18,000 |

| Creative arts & design | £21,000 | £18,000 | £16,000 |

| Education | £24,500 | £18,000 | £17,000 |

| Combined | £26,000 | £19,000 | £18,000 |

| Total average | £25,000 | £19,500 | £18,000 |

For most roles, if graduates possess a lower range of skills when starting out, the average salary earned is £18,000 with the potential to progress as skillsets are improved.

Best universities for high salaries in the UK

The best university for high salaries is the University College of Estate Management (UCEM), as 29% of its graduates receive a salary of £51,000 or more. This is a remote learning institution specialising in construction and real estate graduates, leading to roles that have higher salaries.

London School of Economics (LSE) is the next highest university with 12% of its graduates hitting the £51,000+ salary mark. [13] In 2021, LSE was offering 41 undergraduate courses therefore not having a specialised pool of undergraduates like UCEM.

The following is a list of the top ten universities ranked by the percentage of graduates earning above £51,000:

| University College of Estate Management | 29% |

| London School of Economics and Political Science | 12% |

| BPP University | 11% |

| Birkbeck College | 9% |

| Imperial College of Science, Technology, and Medicine | 8% |

| The Open University | 8% |

| The University of Cambridge | 7% |

| Arden University | 6% |

| The University of Oxford | 6% |

| The University of Warwick | 5% |

The highest published graduate starting salaries for 2021 include law firms White & Case (£50,000), Clifford Chance (£48,000), Baker McKenzie (£48,000), Linklaters (£47,000), technology company TPP (£45,000) and retailer Aldi (£44,000.) [13]

Other studies [31] on universities with the highest graduate salaries have shown:

- Graduates of Bayes Business School (formerly Cass) earn an average of £52,167 five years after graduating.

- Students leaving the University of Oxford can expect an average salary of £47,618 after five years.

- Imperial College graduates earn an average of £45,741 per year after five years.

- The average salary five years after graduation for students from the University of Cambridge is £44,190.

- University College London graduates achieve an average salary of £40,855 five years after graduation.

Gender pay gap for graduates

Male full-time high-skilled graduates who obtained first-class degree qualifications and entered full-time paid employment in the UK in 2019 were paid on average £26,000 compared to high skilled females who were paid £24,500. [19]

On average, male graduates at the age of 25 earn 5% more than the average female graduate. By age 30, the gender pay gap in annual earnings stands at 25%. [20]

The graph below demonstrates the portion of graduates and their earnings for men and women. [19] Studies do not offer comparative information for anyone identifying as other than male or female.

Lower salary bands on average have a higher percentage of women earning more than men. Whilst an average of 6% more women than men earned more in the salary bracket £24,000 – £26,999, it seems that the gender pay gap widens as the salary band increases. In particular, 7% of males earn £51,000+ compared to just 3% of females.

How many unemployed graduates in the UK?

The graduate unemployment rate is 12.7% for graduates who obtained a degree in recent years (2020 onwards). In 2021, the graduate unemployment rate was 12%, meaning the rate has decreased by 0.7 percentage points.[30]

With the rate of 12%, this would mean, in recent years, there are approximately 96,041 unemployed graduates each year in the UK, based off 2021’s academic year.

When looking at the data regionally, we can see that England, Wales, and Scotland have an average graduate unemployment rate of 5%, while Northern Ireland has just 3%. [2]

How many jobs do graduates apply for?

Most graduates who apply for graduate schemes and job roles will never receive a response from the majority of their applications. With most graduates applying on average to around 25 job roles, they find that the ratio of receiving an invitation to an interview to job applications is just over twenty to one .

Degrees with the highest unemployment in the UK

There are some degree subjects that are more likely to land you a job when you graduate than others. One study analysed the employability of different degrees by asking students to give a rating on the job prospects available to them after graduating.

Media and cultural studies came out as the worst degree subject for employment with students rating it a 2.5/5 on average. As a broad degree, students found that jobs in media were highly competitive and applicants with more specific skills generally fared better.

The degree subject with the second lowest employability rating was European studies (2.8/5). Similar to international relations (3/5), graduates in this sector are often competing for a small number of roles in global organisations, making it a tough job market.

Other subjects that students rated poorly for job prospects were Psychology (2.9/5), which often requires further study to obtain a job, and civil engineering (3.1/5) which saw a 50% decrease in new apprentices in 50% as the sector has struggled to offer new jobs.[28]

| Rank | Subject | Rating for job prospects |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Media and cultural studies | 2.5/5 |

| 2 | European studies | 2.8/5 |

| 3 | Psychology | 2.9/5 |

| 4 | International Relations and European Studies | 3/5 |

| 5 | Civil Engineering | 3.1/5 |

UK graduates and Covid-19

The pandemic had a detrimental impact on the opportunities available and career prospects for everyone, but especially graduates who entered the market at the time.

As many were ordered to stay indoors, 75% of graduates noticed a fall in the number of available opportunities in 2020 and 2021, with many (72.6%) graduates feeling less confident about their future. [38] According to the University of Southampton, 83% said that the pandemic had a detrimental impact on graduates’ employment prospects with most graduates saying they had to rethink their future (79.4%). [21]

Furthermore, the ONS found that UK graduates reported a lower life satisfaction score (6.7) than people of their typical age (6.9) and average adults (7.0) during that time. [22]

The pandemic also saw many more graduates in roles that aren’t typically filled by people with degrees. In the UK in 2020, 25.5% of graduates were in a role that was requiring skills less than they had gained in their degree, referred to as a ‘skills mismatch’, this was 5% more in 2019 during the pandemic. [2]

Student finance statistics in UK

Fees to study at university were first introduced in 1998. In 2006, a new system was introduced which would make studying for a degree more accessible. The cost to study was raised to £3,000 in England which would be classed as a tuition loan. As fees gradually increased, the Government raised fees further to £9,000 per year in 2012.

Whilst the pandemic caused record unemployment, graduates were also unable to make repayments. [40] In fact, 201,900 graduates (From various academic years) failed to make repayments through their salary in 2020-21.

How much is the average student loan debt in the UK?

As students in England pay £9,000 a year to study for their chosen degree, they will incur an average of over £46,150 of student loan debt in the 2021/22 year.

In comparison, the average student loan debt varies in other regions, for example, Wales has an average of £33,830, and Northern Ireland has £24,360. Scotland has the lowest average student loan debt at £14,840, this is due to Scottish students not having to pay tuition fees. [23]

When does a student debt have to be paid off?

Whilst the new system implemented in 2012 allows students to defer their student loans during their study, these debts still have to be repaid within 30 years.

The table below shows a graduates minimum earnings (before tax) to have to pay back their student debts:

| England | £27,295 | £2,274 |

| Scotland | £25,000 | £2,083 |

| Wales | £27,295 | £2,274 |

| Northern Ireland | £19,895 | £1,657 |

As you can see, England has the highest repayment threshold allowing graduates to earn up to £27,295 a year before having to start making repayments. In comparison, Northern Ireland has the lowest threshold with graduates beginning repayments once earning £19,895.

The average annual repayment via HMRC per region in order was England (£930), Northern Ireland (£840), Wales (£800), and finally, Scotland (£660.)

How long on average does it take a graduate to pay off their student loan?

As students start making repayment at different thresholds, the average time to pay off a student loan may vary per person. A study revealed that a student loan takes an average of 29 years and 4 months to pay off with the average debt being just under £48k in England. [25]

According to the UK Government, it is expected that just 25% of current full-time undergraduates will repay their full student loan. [26]

Outstanding student debt

The Students Loan Company states that as of 2021, outstanding student loan debt in the United Kingdom reached over 177 billion British pounds starting from 2013/14 when student debts were increased to £9,000 a year.

“Estimates say by 2050, there will be £560 billion of student loan debt in the UK”

England owes the majority of this debt standing at £160 billion with Scotland totalling £6.5 billion, Wales £6.2 billion, and Northern Ireland £4.1 billion. By the middle of the century, the Government predicts that the value of outstanding loans will be around £560 billion. [27]

In 2021, 1,117,000 students took a student loan. The value of student loans equalled £15,908 million.

[1] HESA: Higher Education Student Statistics: UK https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/students

[2] ONS: Graduates’ labour market outcomes during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/articles/graduateslabourmarketoutcomesduringthecoronaviruscovid19pandemicoccupationalswitchesandskillmismatch/2021-03-08

[3] Gov: First year entrants onto undergraduate study

https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/education-skills-and-training/higher-education/first-year-entrants-onto-undergraduate-and-postgraduate-degrees/latest/

Accessed February 2024

[4] Office for Students: Equality, diversity, and student characteristics data.

https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/data-and-analysis/equality-diversity-and-student-characteristics-data/

[5] UK Gov: Undergraduate degree results

https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/education-skills-and-training/higher-education/undergraduate-degree-results/latest

[6] Debut: Degree Dropouts

https://debut.careers/degree-dropouts/

[7] HESA: UK Higher Education Performance Indicators –

https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/performance-indicators/non-continuation

[8] Teaching Abroad Direct: Gap Year Statistics UK

https://www.teachingabroaddirect.co.uk/blog/gap-year-statistics-uk

[9] HESA: HE qualifiers by HE provider and level of qualification obtained 2014/15 to 2021/22

https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/students/table-16

[10] Complete University Guide: University League Tables 2022

https://www.thecompleteuniversityguide.co.uk/league-tables/rankings?sortby=graduate-prospects

[11] Hitachi Capital Invoice Finance: Which university produces the most CEOs? Via

https://www.businessleader.co.uk/which-university-produces-the-most-ceos/#

[12] NHS: Multi-award winning Graduate Management Training Scheme doubles its intake

https://www.hee.nhs.uk/news-blogs-events/news/multi-award-winning-graduate-management-training-scheme-doubles-its-intake

[13] Highfliers: The Graduate Market in 2021

https://www.highfliers.co.uk/download/2021/graduate_market/GM21-Report.pdf

[14] Glassdoor: Graduate Scheme Salaries in the UK

https://www.glassdoor.co.uk/Salaries/graduate-scheme-salary-SRCH_KO0,15.htm

[15] Prospects Luminate: Graduate Salaries in the UK

https://luminate.prospects.ac.uk/graduate-salaries-in-the-uk

[16] Glide: Highest Paid Graduate Schemes

https://glide.co.uk/guides/highest-paid-graduate-schemes/

[17] Prospects: Students urged to focus on longer work experience for employability boost

https://www.prospects.ac.uk/prospects-press-office/students-urged-to-focus-on-longer-work-experience-for-employability-boost

[18] HEFCE: Nature and extent of undergraduates’ work experience

https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/5159/1/rd19_02.pdf

[19] HESA: Graduates’ salaries

https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/graduates/salaries

[20] IFS: Gender differences in subject choice lead to gender pay gap immediately after graduation

https://ifs.org.uk/publications/15657#:~:text=At%20age%2025%2C%20the%20average,annual%20earnings%20stands%20at%2025%25 .

[21] AGCAS : The Impact of Covid-19 On Recent Graduates’ Career Decisions And Outcomes

https://www.agcas.org.uk/write/MediaUploads/Resources/Research%20and%20knowledge/826_The_impact_of_Covid-19_on_recent_graduates_career_decisions_and_outcomes_-_July_2021.pdf

[22] ONS: Coronavirus and higher education students. November 2021 https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandwellbeing/bulletins/coronavirusandhighereducationstudents/5to15november2021

[23] UK Gov: Average Loan Balance on entry into repayment

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/62a9a6c8d3bf7f03744c7c90/Average_loan_balance_on_entry_into_repayment.pdf

[24] STS: Student Loan repayment guide 2021

https://www.savethestudent.org/student-finance/student-loan-repayments.html#plan2

[25] Cosmopolitan: It takes a depressingly long time to pay off your student loan

https://www.cosmopolitan.com/uk/worklife/campus/a12443209/how-long-uni-students-pay-student-loans/

[26] UK Parliament: House of Commons Library: Student loan statistics https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn01079/

[27] Statista: Outstanding debt of student loans in the UK 2013-2021

https://www.statista.com/statistics/376411/uk-outstanding-student-loan-debt/

[28] Ice: Is COVID-19 a friend or foe of civil engineering? – https://www.ice.org.uk/news-and-insight/ice-community-blog/august-2021/covid-19-friend-or-foe-civil-engineering

[29] Edu Opinions: Student reviews of the best degrees for job prospects – https://www.eduopinions.com/blog/what-to-study/eduopinions-student-reviews-guide-best-degrees-for-job-prospects/

[30] UK Gov: Graduate Labour Markets 2022 – https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/graduate-labour-markets

[31] Adzuna: Which Universities Produce the Highest Earning Graduates? – https://www.adzuna.co.uk/blog/which-universities-produce-the-highest-earning-graduates/

[32] Times Higher Education: Graduate Employability – https://www.timeshighereducation.com/student/best-universities/graduate-employability-top-universities-uk-ranked-employers

[33] HESA: Higher Education Graduate Outcomes – https://www.hesa.ac.uk/news/16-06-2022/sb263-higher-education-graduate-outcomes-statistics/activities

[34] HESA: Higher Education Student Statistics: UK, 2021/22 – Qualifications achieved – https://www.hesa.ac.uk/news/19-01-2023/sb265-higher-education-student-statistics/qualifications

[35] HESA: Higher Education Student Statistics: What are HE students’ progression rates and qualifications?- https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/students/outcomes

Advertisement

Predictors of UK postgraduate researcher attendance behaviours and mental health-related attrition intention

- Open access

- Published: 08 December 2022

- Volume 42 , pages 30521–30534, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Clio Berry ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1164-9836 1 ,

- Jeremy E. Niven ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7786-5254 2 &

- Cassie M. Hazell ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5868-9902 3

1718 Accesses

4 Citations

Explore all metrics

High rates of postgraduate researchers (PGRs) terminate their studies early. This attrition can have detrimental personal consequences, and results in a loss of productivity, and research and innovation for the higher education sector and society as a whole. PGRs are vulnerable to the experience of mental health problems; a factor that appears to be increasing attrition amongst students in the UK. However, investigation of the determinants of problems with PGRs’ attendance and influencing intention to discontinue their studies is rare. Here, we consider the relative predictive validity of a set of putative predictors (mental health symptoms, demographic, occupational, psychological, social, and relational) of attendance behaviours (absenteeism, presenteeism, mental health-related intermission) and early attrition intention amongst UK PGRs. Depression, anxiety, and suicidality predicted attendance behaviours and greater attrition intention. Individual demographic and occupational factors predicted all outcomes. Psychological, social and relational factors had less predictive validity, although individual variables in these conceptual clusters did significantly predict some outcomes. Our results suggest that interventions to reduce high rates of mental health problems are likely to improve attendance behaviours, and reduce the extent to which PGRs intermit or consider ending their PhD studies for mental health-related reasons. Initiatives designed to improve supervisory relationships and reduce loneliness may also reduce absenteeism, intermission and attrition intention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Doctoral students’ experiences leading to completion or attrition: a matter of sense, progress and distress

Evaluating mental health and wellbeing of postgraduate researchers: prevalence and contributing factors.

Physical and mental determinants of dropout and retention among nursing students: protocol of the SPRiNG cohort study

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Doctoral attrition is high in many countries, with reported rates of up to 40 to 50% of postgraduate researchers (PGRs) terminating their PhD studies before completion (Geven et al., 2017 ; Litalien & Guay, 2015 ). Attrition can be considered a process, in which PGRs weigh the costs and benefits of persisting or discontinuing, and then do or do not actually end their studies accordingly (Jaksztat et al., 2021 ). Attrition may be provoked by reasons outside of the PhD, such as other opportunities, changing goals, or family obligations (Maher et al., 2017 ), and is not in itself ‘bad’. However, for many PGRs, attrition results in adverse psychological, financial and employment outcomes, as well as there being problematic consequences of non-completed PhD research for supervisors, institutions, and society (Litalien & Guay, 2015 ).

There has been limited research attention to PGR attrition (Jaksztat et al., 2021 ; Litalien & Guay, 2015 ), especially as it relates to mental health problems and other psychological factors (Jaksztat et al., 2021 ). The few known studies that have been conducted in this area originate from the US, where the PhD experience is unique; for example, typically being more structured and longer in duration (Jaksztat et al., 2021 ). This lack of research is especially concerning as increasing numbers of university students generally in the UK appear to be discontinuing their studies due to poor mental health (The Guardian, 2017 ).

Much evidence has emerged in the past few years in particular to suggest that PGRs experience high rates of stress (Hazell et al., 2020 ), depression, anxiety and suicidality; seemingly at rates that exceed those seen in other student and working populations (Hazell et al., 2021 ; Levecque et al., 2017 ). The PhD itself and its surrounding environment have been implicated in the onset and exacerbation of PGR mental health problems (Berry et al., 2020 ; Levecque et al., 2017 ), with the recent COVID-19 pandemic seemingly exacerbating the poor mental health and wellbeing of the adult population generally (Amerio et al., 2021 ; Odone et al., 2020 ), and PGRs specifically (Byrom, 2020 ) even further.

Poor mental health and suicidality are inherently distressing and associated with negative health and functional outcomes (DeRoma et al., 2009 ; Okajima et al., 2015 ), including death by suicide; a frequently under-reported phenomenon (Visentin et al., 2019 ). A functional outcome for PGRs that is important, yet under-investigated, is mental health-related attrition. However, attrition is not the only index of disengagement from academic study. Disengagement can be conceptualised multi-dimensionally, with a focus on problematic attendance behaviours as well as attrition-related cognitions. Attendance behaviours themselves can be conceptualised as using multiple indices: absenteeism (non-planned/non-holiday absences); presenteeism (working or studying when unwell enough to take absence); and intermission (interruption or prolonged break from doctoral studies). Evidence suggests that PGRs with experience of mental health problems report greater absenteeism and presenteeism (Berry et al., 2021a ), intermission, and intention to discontinue doctoral study (Castelló et al., 2017 ; González-Betancor & Dorta-González, 2020 ; Hunter & Devine, 2016 ).

The present study tests a comprehensive range of potential determinants of attendance behaviours and attrition intention amongst a large sample of UK PGRs. We were informed by our previous work which identified putative determinants of mental health symptoms as demographic, occupational, psychological, social and relational in nature (Berry et al., 2021b ). Taking this same approach here aligns with studies that suggest influences on doctoral attrition are complex and multifactorial (Castelló et al., 2017 ; Gardner, 2010 ), and with theoretical models of student retention as being a product of both academic and social integration (Tinto, 2016 ). We first predicted that mental health symptoms would predict poorer attendance and attrition intention.

We next predicted that demographic and occupational factors would predict attendance and attrition intention. White PGRs report fewer days absent but more severe presenteeism (Berry et al., 2021a ). Female PGRs appear to spend more time in presenteeism and absenteeism (Berry et al., 2021a ), report greater number of intermissions (Moore & Keith, 1992 ), greater attrition intention (Castelló et al., 2017 ), and are more likely to actually discontinue their PhD studies (Jaksztat et al., 2021 ). A lack of funding is associated with greater attrition intention (Castelló et al., 2017 ) and attrition (Litalien & Guay, 2015 ). PGRs who spend less time per week in PhD study report greater attrition intention (Castelló et al., 2017 ). However, it is unclear to what extent demographic and PhD-study related characteristics independently and uniquely influence attendance behaviours and attrition intention, i.e. when modelled simultaneously and when considering psychological and social factors.

Finally, we predicted that psychological, social and relationship factors would predict PGR attendance behaviours and attrition intention. With respect to psychological factors, PGRs who perceive themselves to lack competence report greater attrition intention (Castelló et al., 2017 ) and attrition (Litalien & Guay, 2015 ). Moreover, lower academic aspirations are associated with a greater number of intermissions (Moore & Keith, 1992 ). This suggests a potential role in doctoral attrition for the psychological traits of perfectionism ( i.e. having high standards and/or believing one is not meeting their standards) and impostor thoughts ( i.e. believing that one is not as competent as others perceive one to be). Moreover, the nature of interpersonal relationships in general, and specifically with the supervisor, are likely important. Social disconnectedness is associated with PGR attrition intention (Castelló et al., 2017 ; Volkert et al., 2018 ). Supervisory relationship stressors and lack of psychological support are associated with attrition intention (Litalien & Guay, 2015 ; Volkert et al., 2018 ), and clear authoritative direction, i.e . supervisor agency, seems important in doctoral completion (McCray & Joseph-Richard, 2020 ). Mental health problems may be a confounding factor here, however, as previous research has found supervisory relationship qualities to predict mental health symptoms (Berry et al., 2021b ) and thus, this should be accounted for in modelling associations with attendance and attrition-related outcomes.

Research considering the relative contribution of influences across multiple domains on PGR disengagement is rare, especially considering indices spanning multiple proxies of attendance and attrition intention. Furthermore, although research has considered whether dissatisfaction is a precursor to attrition (González-Betancor & Dorta-González, 2020 ), no known study has tested whether problematic attendance behaviours themselves may function as precursors to attrition intention. We predicted that this would be the case because academic disengagement leads to intention to leave academia (Lesko & Corpus, 2006 ). Furthermore, absence and presenteeism reduce productivity (Johns, 2010 ), organisational commitment and embeddedness (Boswell et al., 2008 ), and additionally likely increase time-to-completion, which in turn predicts doctoral attrition (de Valero, 2001 ).

Based upon our predictions, we tested the specific hypotheses that attendance behaviours and attrition intention would be predicted by mental health symptoms (depression, anxiety, suicidality), and then by the following factors:

demographic; age, gender, ethnicity, UK residency, disability and lifetime mental health problem prevalence,

occupational; fulltime status, funding, year of study, fieldwork, time spent in occupational activity,

psychological; impostor thoughts, perfectionistic standards and discrepancy,

social; loneliness and multiple group memberships, and

relational; supervisory relationship communion and agency.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedure.

Data were obtained from a national online self-report survey (U-DOC) conducted in the UK between 2018 and 2019. The survey was designed to contain a battery of self-report survey assessments and qualitative data pertaining to PGR mental health symptoms, and multiple factors considered to be potential correlates of these symptoms and associated behaviours. Participants were a convenience sample of 3352 current PGRs who provided informed consent and then completed questionnaire measures and qualitative free-text questions. The participant inclusion criteria were that participants were aged 18 years or over and were currently studying for their PhD at a UK University. Participants were recruited by contacting all UK doctoral schools ( N = 162) and asking for them to promote the study, via email, institutional communications and through social media advertising (e.g. Twitter, Facebook). The research team additionally promoted the study via social media platforms. The study received research ethics approval from the University of Sussex Sciences and Technology Cross-Schools Research Ethics Committee (Reference: ER/CH283/9). Additional methodological and sample details are reported elsewhere (Authors, 2021).

Absenteeism and presenteeism

Absenteeism and presenteeism data were collected using items from the Institute for Medical Technology Assessment Productivity Cost Questionnaire (iMTA PCQ) – Presenteeism Scale (Bouwmans et al., 2015 ). For the present study, binary variables were used to indicate absenteeism (no absenteeism 0, absenteeism 1) or presenteeism (no presenteeism 0, presenteeism 1) specifically regarding PhD study in the past month, excluding planned annual leave or holidays. Absenteeism referred to days absent and presenteeism referred to “days in which you worked but during this time were bothered by physical or psychological problems”. Additional information about the measure of absenteeism and presenteeism has been published previously (Berry et al., 2021a ).

Mental health-related intermission and attrition intention

Respondents indicated if they had had to take a break from their PhD studies for mental health-related reasons (mental health-related intermission), and if they had considered terminating their PhD studies for mental health-related reasons (mental health-related attrition intention). In both cases, respondents indicated whether statements were ‘true’ or ‘false’; coded as ‘1’ or ‘0’, respectively. A third option ‘not sure’ was also coded as ‘0’.

Mental health symptoms

The 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 (Kroenke et al., 2001 )) was used to capture depression symptoms, the 7-item (GAD-7 (Spitzer et al., 2006 ) to capture anxiety symptoms, and the 4-item Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire – Revised (SBQ-R (Linehan & Nielsen, 1981 )) to capture suicidality.

Demographic characteristics

Participants self-reported age in years, gender (coded for this study as female versus male/another identity), ethnicity (coded as White versus non-White), UK citizenship ( versus non-UK citizenship), disability status (not including mental health problems), and lifetime prevalence of mental health problems (coded as pre-existing mental health problems up to and including during undergraduate studies versus onset during postgraduate study).

Occupational characteristics

Participants were asked to self-report their PhD study mode (fulltime versus part-time), funding (full, partial or self-funded), year of study, and past or planned fieldwork ( versus none). Participants estimated how many hours per week on average they spent engaged in PhD study, teaching activities, and any other employment. These were summed to create weekly average of hours spent in occupational activity.

Psychological factors

Impostor thoughts were measured using the 20-item Clance Impostor Phenomenon Scale (CIPS (Clance, 1985 )), and perfectionistic standards ( i.e. high expectations for oneself) and discrepancy ( i.e. the degree to which one thinks they fail to meet these expectations) using the 8-item Short Almost Perfect Scale (SAPS (Rice et al., 2014 )).

Social factors

The social variables captured were loneliness ( i.e. the subjective sense of deficiency in one’s social relationships), and multiple group memberships ( i.e. the degree to which one perceives they have ties and relationships with multiple social groups). Loneliness was measured using the 20-item UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell et al., 1978 ). Multiple group memberships was captured using a 4-item self-report scale derived from the Exeter Identity Transition Scale (Haslam et al., 2008 ).

Relational factors

The relational qualities of the supervisory relationship were measured using the 41-item Questionnaire on Supervisor–Doctoral student Interaction (QSDI (Mainhard et al., 2009 )). Two dimensional scores were used; agency (influence and leadership) and communion (proximity and cooperativeness).

All analysis was conducted in SPSS (version 26.0). Bivariate associations between putative predictor variables, attendance behaviours and attrition intention were examined using t-test and chi-square models. Hierarchical logistic regression was used to test predictors of attendance behaviours and attrition intention in four separate models. Attendance behaviours and attrition intention were specified as binary categorical dependent variables in these models. Mental health symptom scores were added as predictors first, before then entering the demographic, occupational, psychological, social and relational factors in turn as separate blocks. Variables not showing bivariate associations with attendance behaviours and attrition intention were not entered. Hochberg’s correction was applied for multiple testing in the final models (Menyhart et al., 2021 ). These models met the requisite assumptions of the independence of errors and absence of significant multicollinearity. Moreover, with the exception of two standardised residuals in the presenteeism model and one in the attrition intention model, all standardised residuals were under 2.5. Cook’s distances and DFbetas all under 1, suggesting, showed no significant impact of unusual cases on any model. The Box-Tidwell test was used to confirm that the relationship between the logit (log-odds) of the outcome and each continuous predictor was linear. All interactions between the predictors and their logits were non-significant, with the exception of depression (PHQ-9), anxiety (GAD-7), and supervisory agency and communion (QSDI) in one model respectively. However, these interactions were not highly significant (p ≥ 0.03) and the sample size is large, therefore, we considered the assumption of non-linearity to be satisfied (Wuensch, 2021 ).

Sample characteristics