Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

Definition and Introduction

Journal article analysis assignments require you to summarize and critically assess the quality of an empirical research study published in a scholarly [a.k.a., academic, peer-reviewed] journal. The article may be assigned by the professor, chosen from course readings listed in the syllabus, or you must locate an article on your own, usually with the requirement that you search using a reputable library database, such as, JSTOR or ProQuest . The article chosen is expected to relate to the overall discipline of the course, specific course content, or key concepts discussed in class. In some cases, the purpose of the assignment is to analyze an article that is part of the literature review for a future research project.

Analysis of an article can be assigned to students individually or as part of a small group project. The final product is usually in the form of a short paper [typically 1- 6 double-spaced pages] that addresses key questions the professor uses to guide your analysis or that assesses specific parts of a scholarly research study [e.g., the research problem, methodology, discussion, conclusions or findings]. The analysis paper may be shared on a digital course management platform and/or presented to the class for the purpose of promoting a wider discussion about the topic of the study. Although assigned in any level of undergraduate and graduate coursework in the social and behavioral sciences, professors frequently include this assignment in upper division courses to help students learn how to effectively identify, read, and analyze empirical research within their major.

Franco, Josue. “Introducing the Analysis of Journal Articles.” Prepared for presentation at the American Political Science Association’s 2020 Teaching and Learning Conference, February 7-9, 2020, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Sego, Sandra A. and Anne E. Stuart. "Learning to Read Empirical Articles in General Psychology." Teaching of Psychology 43 (2016): 38-42; Kershaw, Trina C., Jordan P. Lippman, and Jennifer Fugate. "Practice Makes Proficient: Teaching Undergraduate Students to Understand Published Research." Instructional Science 46 (2018): 921-946; Woodward-Kron, Robyn. "Critical Analysis and the Journal Article Review Assignment." Prospect 18 (August 2003): 20-36; MacMillan, Margy and Allison MacKenzie. "Strategies for Integrating Information Literacy and Academic Literacy: Helping Undergraduate Students make the most of Scholarly Articles." Library Management 33 (2012): 525-535.

Benefits of Journal Article Analysis Assignments

Analyzing and synthesizing a scholarly journal article is intended to help students obtain the reading and critical thinking skills needed to develop and write their own research papers. This assignment also supports workplace skills where you could be asked to summarize a report or other type of document and report it, for example, during a staff meeting or for a presentation.

There are two broadly defined ways that analyzing a scholarly journal article supports student learning:

Improve Reading Skills

Conducting research requires an ability to review, evaluate, and synthesize prior research studies. Reading prior research requires an understanding of the academic writing style , the type of epistemological beliefs or practices underpinning the research design, and the specific vocabulary and technical terminology [i.e., jargon] used within a discipline. Reading scholarly articles is important because academic writing is unfamiliar to most students; they have had limited exposure to using peer-reviewed journal articles prior to entering college or students have yet to gain exposure to the specific academic writing style of their disciplinary major. Learning how to read scholarly articles also requires careful and deliberate concentration on how authors use specific language and phrasing to convey their research, the problem it addresses, its relationship to prior research, its significance, its limitations, and how authors connect methods of data gathering to the results so as to develop recommended solutions derived from the overall research process.

Improve Comprehension Skills

In addition to knowing how to read scholarly journals articles, students must learn how to effectively interpret what the scholar(s) are trying to convey. Academic writing can be dense, multi-layered, and non-linear in how information is presented. In addition, scholarly articles contain footnotes or endnotes, references to sources, multiple appendices, and, in some cases, non-textual elements [e.g., graphs, charts] that can break-up the reader’s experience with the narrative flow of the study. Analyzing articles helps students practice comprehending these elements of writing, critiquing the arguments being made, reflecting upon the significance of the research, and how it relates to building new knowledge and understanding or applying new approaches to practice. Comprehending scholarly writing also involves thinking critically about where you fit within the overall dialogue among scholars concerning the research problem, finding possible gaps in the research that require further analysis, or identifying where the author(s) has failed to examine fully any specific elements of the study.

In addition, journal article analysis assignments are used by professors to strengthen discipline-specific information literacy skills, either alone or in relation to other tasks, such as, giving a class presentation or participating in a group project. These benefits can include the ability to:

- Effectively paraphrase text, which leads to a more thorough understanding of the overall study;

- Identify and describe strengths and weaknesses of the study and their implications;

- Relate the article to other course readings and in relation to particular research concepts or ideas discussed during class;

- Think critically about the research and summarize complex ideas contained within;

- Plan, organize, and write an effective inquiry-based paper that investigates a research study, evaluates evidence, expounds on the author’s main ideas, and presents an argument concerning the significance and impact of the research in a clear and concise manner;

- Model the type of source summary and critique you should do for any college-level research paper; and,

- Increase interest and engagement with the research problem of the study as well as with the discipline.

Kershaw, Trina C., Jennifer Fugate, and Aminda J. O'Hare. "Teaching Undergraduates to Understand Published Research through Structured Practice in Identifying Key Research Concepts." Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology . Advance online publication, 2020; Franco, Josue. “Introducing the Analysis of Journal Articles.” Prepared for presentation at the American Political Science Association’s 2020 Teaching and Learning Conference, February 7-9, 2020, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Sego, Sandra A. and Anne E. Stuart. "Learning to Read Empirical Articles in General Psychology." Teaching of Psychology 43 (2016): 38-42; Woodward-Kron, Robyn. "Critical Analysis and the Journal Article Review Assignment." Prospect 18 (August 2003): 20-36; MacMillan, Margy and Allison MacKenzie. "Strategies for Integrating Information Literacy and Academic Literacy: Helping Undergraduate Students make the most of Scholarly Articles." Library Management 33 (2012): 525-535; Kershaw, Trina C., Jordan P. Lippman, and Jennifer Fugate. "Practice Makes Proficient: Teaching Undergraduate Students to Understand Published Research." Instructional Science 46 (2018): 921-946.

Structure and Organization

A journal article analysis paper should be written in paragraph format and include an instruction to the study, your analysis of the research, and a conclusion that provides an overall assessment of the author's work, along with an explanation of what you believe is the study's overall impact and significance. Unless the purpose of the assignment is to examine foundational studies published many years ago, you should select articles that have been published relatively recently [e.g., within the past few years].

Since the research has been completed, reference to the study in your paper should be written in the past tense, with your analysis stated in the present tense [e.g., “The author portrayed access to health care services in rural areas as primarily a problem of having reliable transportation. However, I believe the author is overgeneralizing this issue because...”].

Introduction Section

The first section of a journal analysis paper should describe the topic of the article and highlight the author’s main points. This includes describing the research problem and theoretical framework, the rationale for the research, the methods of data gathering and analysis, the key findings, and the author’s final conclusions and recommendations. The narrative should focus on the act of describing rather than analyzing. Think of the introduction as a more comprehensive and detailed descriptive abstract of the study.

Possible questions to help guide your writing of the introduction section may include:

- Who are the authors and what credentials do they hold that contributes to the validity of the study?

- What was the research problem being investigated?

- What type of research design was used to investigate the research problem?

- What theoretical idea(s) and/or research questions were used to address the problem?

- What was the source of the data or information used as evidence for analysis?

- What methods were applied to investigate this evidence?

- What were the author's overall conclusions and key findings?

Critical Analysis Section

The second section of a journal analysis paper should describe the strengths and weaknesses of the study and analyze its significance and impact. This section is where you shift the narrative from describing to analyzing. Think critically about the research in relation to other course readings, what has been discussed in class, or based on your own life experiences. If you are struggling to identify any weaknesses, explain why you believe this to be true. However, no study is perfect, regardless of how laudable its design may be. Given this, think about the repercussions of the choices made by the author(s) and how you might have conducted the study differently. Examples can include contemplating the choice of what sources were included or excluded in support of examining the research problem, the choice of the method used to analyze the data, or the choice to highlight specific recommended courses of action and/or implications for practice over others. Another strategy is to place yourself within the research study itself by thinking reflectively about what may be missing if you had been a participant in the study or if the recommended courses of action specifically targeted you or your community.

Possible questions to help guide your writing of the analysis section may include:

Introduction

- Did the author clearly state the problem being investigated?

- What was your reaction to and perspective on the research problem?

- Was the study’s objective clearly stated? Did the author clearly explain why the study was necessary?

- How well did the introduction frame the scope of the study?

- Did the introduction conclude with a clear purpose statement?

Literature Review

- Did the literature review lay a foundation for understanding the significance of the research problem?

- Did the literature review provide enough background information to understand the problem in relation to relevant contexts [e.g., historical, economic, social, cultural, etc.].

- Did literature review effectively place the study within the domain of prior research? Is anything missing?

- Was the literature review organized by conceptual categories or did the author simply list and describe sources?

- Did the author accurately explain how the data or information were collected?

- Was the data used sufficient in supporting the study of the research problem?

- Was there another methodological approach that could have been more illuminating?

- Give your overall evaluation of the methods used in this article. How much trust would you put in generating relevant findings?

Results and Discussion

- Were the results clearly presented?

- Did you feel that the results support the theoretical and interpretive claims of the author? Why?

- What did the author(s) do especially well in describing or analyzing their results?

- Was the author's evaluation of the findings clearly stated?

- How well did the discussion of the results relate to what is already known about the research problem?

- Was the discussion of the results free of repetition and redundancies?

- What interpretations did the authors make that you think are in incomplete, unwarranted, or overstated?

- Did the conclusion effectively capture the main points of study?

- Did the conclusion address the research questions posed? Do they seem reasonable?

- Were the author’s conclusions consistent with the evidence and arguments presented?

- Has the author explained how the research added new knowledge or understanding?

Overall Writing Style

- If the article included tables, figures, or other non-textual elements, did they contribute to understanding the study?

- Were ideas developed and related in a logical sequence?

- Were transitions between sections of the article smooth and easy to follow?

Overall Evaluation Section

The final section of a journal analysis paper should bring your thoughts together into a coherent assessment of the value of the research study . This section is where the narrative flow transitions from analyzing specific elements of the article to critically evaluating the overall study. Explain what you view as the significance of the research in relation to the overall course content and any relevant discussions that occurred during class. Think about how the article contributes to understanding the overall research problem, how it fits within existing literature on the topic, how it relates to the course, and what it means to you as a student researcher. In some cases, your professor will also ask you to describe your experiences writing the journal article analysis paper as part of a reflective learning exercise.

Possible questions to help guide your writing of the conclusion and evaluation section may include:

- Was the structure of the article clear and well organized?

- Was the topic of current or enduring interest to you?

- What were the main weaknesses of the article? [this does not refer to limitations stated by the author, but what you believe are potential flaws]

- Was any of the information in the article unclear or ambiguous?

- What did you learn from the research? If nothing stood out to you, explain why.

- Assess the originality of the research. Did you believe it contributed new understanding of the research problem?

- Were you persuaded by the author’s arguments?

- If the author made any final recommendations, will they be impactful if applied to practice?

- In what ways could future research build off of this study?

- What implications does the study have for daily life?

- Was the use of non-textual elements, footnotes or endnotes, and/or appendices helpful in understanding the research?

- What lingering questions do you have after analyzing the article?

NOTE: Avoid using quotes. One of the main purposes of writing an article analysis paper is to learn how to effectively paraphrase and use your own words to summarize a scholarly research study and to explain what the research means to you. Using and citing a direct quote from the article should only be done to help emphasize a key point or to underscore an important concept or idea.

Business: The Article Analysis . Fred Meijer Center for Writing, Grand Valley State University; Bachiochi, Peter et al. "Using Empirical Article Analysis to Assess Research Methods Courses." Teaching of Psychology 38 (2011): 5-9; Brosowsky, Nicholaus P. et al. “Teaching Undergraduate Students to Read Empirical Articles: An Evaluation and Revision of the QALMRI Method.” PsyArXi Preprints , 2020; Holster, Kristin. “Article Evaluation Assignment”. TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology . Washington DC: American Sociological Association, 2016; Kershaw, Trina C., Jennifer Fugate, and Aminda J. O'Hare. "Teaching Undergraduates to Understand Published Research through Structured Practice in Identifying Key Research Concepts." Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology . Advance online publication, 2020; Franco, Josue. “Introducing the Analysis of Journal Articles.” Prepared for presentation at the American Political Science Association’s 2020 Teaching and Learning Conference, February 7-9, 2020, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Reviewer's Guide . SAGE Reviewer Gateway, SAGE Journals; Sego, Sandra A. and Anne E. Stuart. "Learning to Read Empirical Articles in General Psychology." Teaching of Psychology 43 (2016): 38-42; Kershaw, Trina C., Jordan P. Lippman, and Jennifer Fugate. "Practice Makes Proficient: Teaching Undergraduate Students to Understand Published Research." Instructional Science 46 (2018): 921-946; Gyuris, Emma, and Laura Castell. "To Tell Them or Show Them? How to Improve Science Students’ Skills of Critical Reading." International Journal of Innovation in Science and Mathematics Education 21 (2013): 70-80; Woodward-Kron, Robyn. "Critical Analysis and the Journal Article Review Assignment." Prospect 18 (August 2003): 20-36; MacMillan, Margy and Allison MacKenzie. "Strategies for Integrating Information Literacy and Academic Literacy: Helping Undergraduate Students Make the Most of Scholarly Articles." Library Management 33 (2012): 525-535.

Writing Tip

Not All Scholarly Journal Articles Can Be Critically Analyzed

There are a variety of articles published in scholarly journals that do not fit within the guidelines of an article analysis assignment. This is because the work cannot be empirically examined or it does not generate new knowledge in a way which can be critically analyzed.

If you are required to locate a research study on your own, avoid selecting these types of journal articles:

- Theoretical essays which discuss concepts, assumptions, and propositions, but report no empirical research;

- Statistical or methodological papers that may analyze data, but the bulk of the work is devoted to refining a new measurement, statistical technique, or modeling procedure;

- Articles that review, analyze, critique, and synthesize prior research, but do not report any original research;

- Brief essays devoted to research methods and findings;

- Articles written by scholars in popular magazines or industry trade journals;

- Academic commentary that discusses research trends or emerging concepts and ideas, but does not contain citations to sources; and

- Pre-print articles that have been posted online, but may undergo further editing and revision by the journal's editorial staff before final publication. An indication that an article is a pre-print is that it has no volume, issue, or page numbers assigned to it.

Journal Analysis Assignment - Myers . Writing@CSU, Colorado State University; Franco, Josue. “Introducing the Analysis of Journal Articles.” Prepared for presentation at the American Political Science Association’s 2020 Teaching and Learning Conference, February 7-9, 2020, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Woodward-Kron, Robyn. "Critical Analysis and the Journal Article Review Assignment." Prospect 18 (August 2003): 20-36.

- << Previous: Annotated Bibliography

- Next: Giving an Oral Presentation >>

- Last Updated: Jun 3, 2024 9:44 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

Research Paper Analysis: How to Analyze a Research Article + Example

Why might you need to analyze research? First of all, when you analyze a research article, you begin to understand your assigned reading better. It is also the first step toward learning how to write your own research articles and literature reviews. However, if you have never written a research paper before, it may be difficult for you to analyze one. After all, you may not know what criteria to use to evaluate it. But don’t panic! We will help you figure it out!

In this article, our team has explained how to analyze research papers quickly and effectively. At the end, you will also find a research analysis paper example to see how everything works in practice.

- 🔤 Research Analysis Definition

📊 How to Analyze a Research Article

✍️ how to write a research analysis.

- 📝 Analysis Example

- 🔎 More Examples

🔗 References

🔤 research paper analysis: what is it.

A research paper analysis is an academic writing assignment in which you analyze a scholarly article’s methodology, data, and findings. In essence, “to analyze” means to break something down into components and assess each of them individually and in relation to each other. The goal of an analysis is to gain a deeper understanding of a subject. So, when you analyze a research article, you dissect it into elements like data sources , research methods, and results and evaluate how they contribute to the study’s strengths and weaknesses.

📋 Research Analysis Format

A research analysis paper has a pretty straightforward structure. Check it out below!

| This section should state the analyzed article’s title and author and outline its main idea. The introduction should end with a strong , presenting your conclusions about the article’s strengths, weaknesses, or scientific value. | |

| Here, you need to summarize the major concepts presented in your research article. This section should be brief. | |

| The analysis should contain your evaluation of the paper. It should explain whether the research meets its intentions and purpose and whether it provides a clear and valid interpretation of results. | |

| The closing paragraph should include a rephrased thesis, a summary of core ideas, and an explanation of the analyzed article’s relevance and importance. | |

| At the end of your work, you should add a reference list. It should include the analyzed article’s citation in your required format (APA, MLA, etc.). If you’ve cited other sources in your paper, they must also be indicated in the list. |

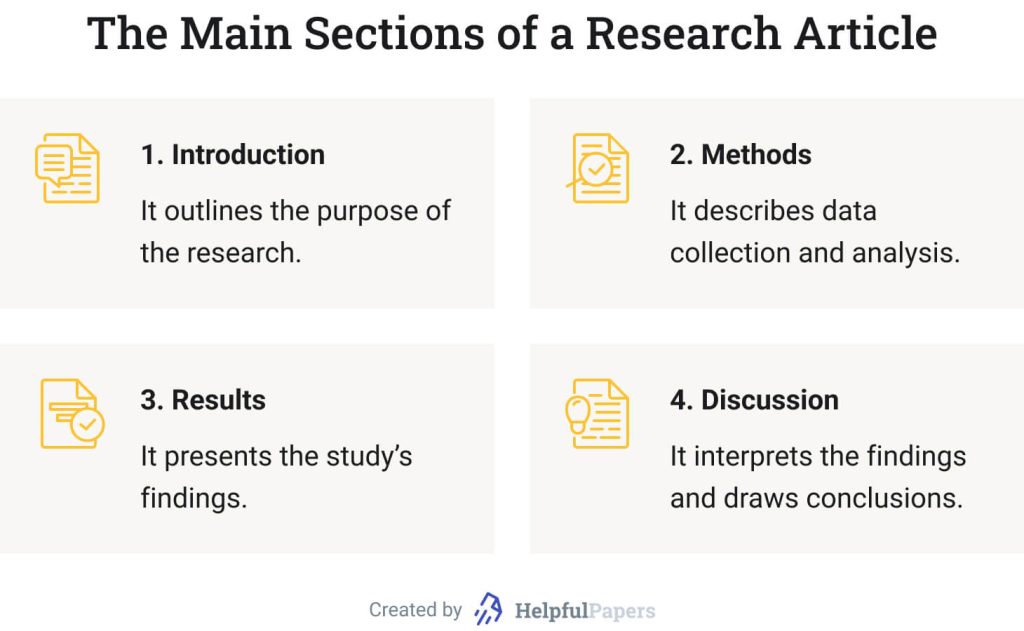

Research articles usually include the following sections: introduction, methods, results, and discussion. In the following paragraphs, we will discuss how to analyze a scientific article with a focus on each of its parts.

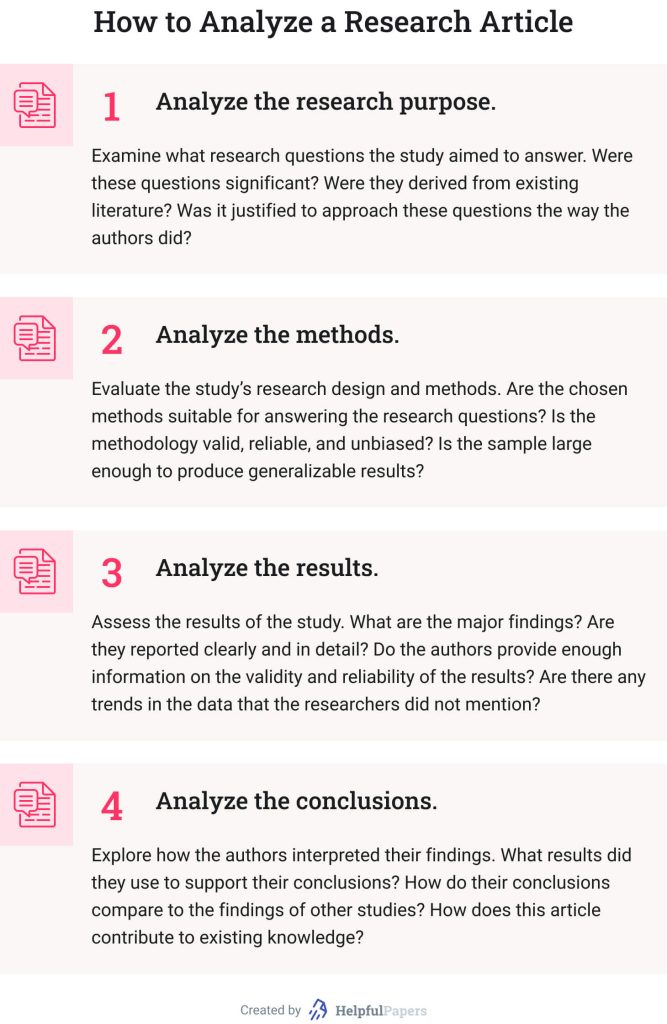

How to Analyze a Research Paper: Purpose

The purpose of the study is usually outlined in the introductory section of the article. Analyzing the research paper’s objectives is critical to establish the context for the rest of your analysis.

When analyzing the research aim, you should evaluate whether it was justified for the researchers to conduct the study. In other words, you should assess whether their research question was significant and whether it arose from existing literature on the topic.

Here are some questions that may help you analyze a research paper’s purpose:

- Why was the research carried out?

- What gaps does it try to fill, or what controversies to settle?

- How does the study contribute to its field?

- Do you agree with the author’s justification for approaching this particular question in this way?

How to Analyze a Paper: Methods

When analyzing the methodology section , you should indicate the study’s research design (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed) and methods used (for example, experiment, case study, correlational research, survey, etc.). After that, you should assess whether these methods suit the research purpose. In other words, do the chosen methods allow scholars to answer their research questions within the scope of their study?

For example, if scholars wanted to study US students’ average satisfaction with their higher education experience, they could conduct a quantitative survey . However, if they wanted to gain an in-depth understanding of the factors influencing US students’ satisfaction with higher education, qualitative interviews would be more appropriate.

When analyzing methods, you should also look at the research sample . Did the scholars use randomization to select study participants? Was the sample big enough for the results to be generalizable to a larger population?

You can also answer the following questions in your methodology analysis:

- Is the methodology valid? In other words, did the researchers use methods that accurately measure the variables of interest?

- Is the research methodology reliable? A research method is reliable if it can produce stable and consistent results under the same circumstances.

- Is the study biased in any way?

- What are the limitations of the chosen methodology?

How to Analyze Research Articles’ Results

You should start the analysis of the article results by carefully reading the tables, figures, and text. Check whether the findings correspond to the initial research purpose. See whether the results answered the author’s research questions or supported the hypotheses stated in the introduction.

To analyze the results section effectively, answer the following questions:

- What are the major findings of the study?

- Did the author present the results clearly and unambiguously?

- Are the findings statistically significant ?

- Does the author provide sufficient information on the validity and reliability of the results?

- Have you noticed any trends or patterns in the data that the author did not mention?

How to Analyze Research: Discussion

Finally, you should analyze the authors’ interpretation of results and its connection with research objectives. Examine what conclusions the authors drew from their study and whether these conclusions answer the original question.

You should also pay attention to how the authors used findings to support their conclusions. For example, you can reflect on why their findings support that particular inference and not another one. Moreover, more than one conclusion can sometimes be made based on the same set of results. If that’s the case with your article, you should analyze whether the authors addressed other interpretations of their findings .

Here are some useful questions you can use to analyze the discussion section:

- What findings did the authors use to support their conclusions?

- How do the researchers’ conclusions compare to other studies’ findings?

- How does this study contribute to its field?

- What future research directions do the authors suggest?

- What additional insights can you share regarding this article? For example, do you agree with the results? What other questions could the researchers have answered?

Now, you know how to analyze an article that presents research findings. However, it’s just a part of the work you have to do to complete your paper. So, it’s time to learn how to write research analysis! Check out the steps below!

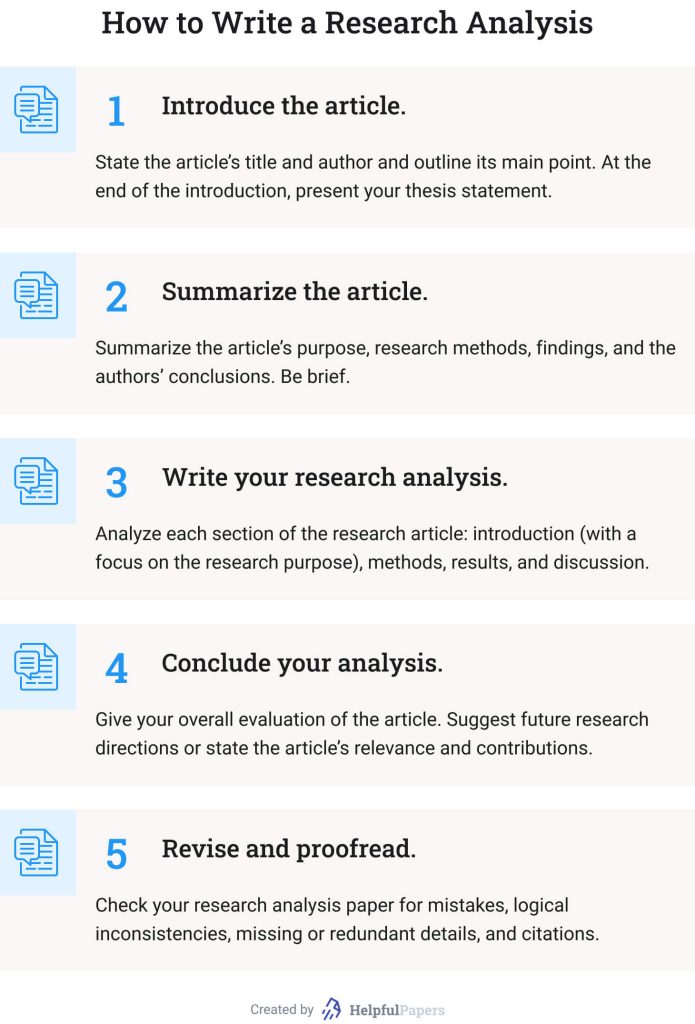

1. Introduce the Article

As with most academic assignments, you should start your research article analysis with an introduction. Here’s what it should include:

- The article’s publication details . Specify the title of the scholarly work you are analyzing, its authors, and publication date. Remember to enclose the article’s title in quotation marks and write it in title case .

- The article’s main point . State what the paper is about. What did the authors study, and what was their major finding?

- Your thesis statement . End your introduction with a strong claim summarizing your evaluation of the article. Consider briefly outlining the research paper’s strengths, weaknesses, and significance in your thesis.

Keep your introduction brief. Save the word count for the “meat” of your paper — that is, for the analysis.

2. Summarize the Article

Now, you should write a brief and focused summary of the scientific article. It should be shorter than your analysis section and contain all the relevant details about the research paper.

Here’s what you should include in your summary:

- The research purpose . Briefly explain why the research was done. Identify the authors’ purpose and research questions or hypotheses .

- Methods and results . Summarize what happened in the study. State only facts, without the authors’ interpretations of them. Avoid using too many numbers and details; instead, include only the information that will help readers understand what happened.

- The authors’ conclusions . Outline what conclusions the researchers made from their study. In other words, describe how the authors explained the meaning of their findings.

If you need help summarizing an article, you can use our free summary generator .

3. Write Your Research Analysis

The analysis of the study is the most crucial part of this assignment type. Its key goal is to evaluate the article critically and demonstrate your understanding of it.

We’ve already covered how to analyze a research article in the section above. Here’s a quick recap:

- Analyze whether the study’s purpose is significant and relevant.

- Examine whether the chosen methodology allows for answering the research questions.

- Evaluate how the authors presented the results.

- Assess whether the authors’ conclusions are grounded in findings and answer the original research questions.

Although you should analyze the article critically, it doesn’t mean you only should criticize it. If the authors did a good job designing and conducting their study, be sure to explain why you think their work is well done. Also, it is a great idea to provide examples from the article to support your analysis.

4. Conclude Your Analysis of Research Paper

A conclusion is your chance to reflect on the study’s relevance and importance. Explain how the analyzed paper can contribute to the existing knowledge or lead to future research. Also, you need to summarize your thoughts on the article as a whole. Avoid making value judgments — saying that the paper is “good” or “bad.” Instead, use more descriptive words and phrases such as “This paper effectively showed…”

Need help writing a compelling conclusion? Try our free essay conclusion generator !

5. Revise and Proofread

Last but not least, you should carefully proofread your paper to find any punctuation, grammar, and spelling mistakes. Start by reading your work out loud to ensure that your sentences fit together and sound cohesive. Also, it can be helpful to ask your professor or peer to read your work and highlight possible weaknesses or typos.

📝 Research Paper Analysis Example

We have prepared an analysis of a research paper example to show how everything works in practice.

No Homework Policy: Research Article Analysis Example

This paper aims to analyze the research article entitled “No Assignment: A Boon or a Bane?” by Cordova, Pagtulon-an, and Tan (2019). This study examined the effects of having and not having assignments on weekends on high school students’ performance and transmuted mean scores. This article effectively shows the value of homework for students, but larger studies are needed to support its findings.

Cordova et al. (2019) conducted a descriptive quantitative study using a sample of 115 Grade 11 students of the Central Mindanao University Laboratory High School in the Philippines. The sample was divided into two groups: the first received homework on weekends, while the second didn’t. The researchers compared students’ performance records made by teachers and found that students who received assignments performed better than their counterparts without homework.

The purpose of this study is highly relevant and justified as this research was conducted in response to the debates about the “No Homework Policy” in the Philippines. Although the descriptive research design used by the authors allows to answer the research question, the study could benefit from an experimental design. This way, the authors would have firm control over variables. Additionally, the study’s sample size was not large enough for the findings to be generalized to a larger population.

The study results are presented clearly, logically, and comprehensively and correspond to the research objectives. The researchers found that students’ mean grades decreased in the group without homework and increased in the group with homework. Based on these findings, the authors concluded that homework positively affected students’ performance. This conclusion is logical and grounded in data.

This research effectively showed the importance of homework for students’ performance. Yet, since the sample size was relatively small, larger studies are needed to ensure the authors’ conclusions can be generalized to a larger population.

🔎 More Research Analysis Paper Examples

Do you want another research analysis example? Check out the best analysis research paper samples below:

- Gracious Leadership Principles for Nurses: Article Analysis

- Effective Mental Health Interventions: Analysis of an Article

- Nursing Turnover: Article Analysis

- Nursing Practice Issue: Qualitative Research Article Analysis

- Quantitative Article Critique in Nursing

- LIVE Program: Quantitative Article Critique

- Evidence-Based Practice Beliefs and Implementation: Article Critique

- “Differential Effectiveness of Placebo Treatments”: Research Paper Analysis

- “Family-Based Childhood Obesity Prevention Interventions”: Analysis Research Paper Example

- “Childhood Obesity Risk in Overweight Mothers”: Article Analysis

- “Fostering Early Breast Cancer Detection” Article Analysis

- Space and the Atom: Article Analysis

- “Democracy and Collective Identity in the EU and the USA”: Article Analysis

- China’s Hegemonic Prospects: Article Review

- Article Analysis: Fear of Missing Out

- Codependence, Narcissism, and Childhood Trauma: Analysis of the Article

- Relationship Between Work Intensity, Workaholism, Burnout, and MSC: Article Review

We hope that our article on research paper analysis has been helpful. If you liked it, please share this article with your friends!

- Analyzing Research Articles: A Guide for Readers and Writers | Sam Mathews

- Summary and Analysis of Scientific Research Articles | San José State University Writing Center

- Analyzing Scholarly Articles | Texas A&M University

- Article Analysis Assignment | University of Wisconsin-Madison

- How to Summarize a Research Article | University of Connecticut

- Critique/Review of Research Articles | University of Calgary

- Art of Reading a Journal Article: Methodically and Effectively | PubMed Central

- Write a Critical Review of a Scientific Journal Article | McLaughlin Library

- How to Read and Understand a Scientific Paper: A Guide for Non-scientists | LSE

- How to Analyze Journal Articles | Classroom

How to Write an Animal Testing Essay: Tips for Argumentative & Persuasive Papers

Descriptive essay topics: examples, outline, & more.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HCA Healthc J Med

- v.1(2); 2020

- PMC10324782

Introduction to Research Statistical Analysis: An Overview of the Basics

Christian vandever.

1 HCA Healthcare Graduate Medical Education

Description

This article covers many statistical ideas essential to research statistical analysis. Sample size is explained through the concepts of statistical significance level and power. Variable types and definitions are included to clarify necessities for how the analysis will be interpreted. Categorical and quantitative variable types are defined, as well as response and predictor variables. Statistical tests described include t-tests, ANOVA and chi-square tests. Multiple regression is also explored for both logistic and linear regression. Finally, the most common statistics produced by these methods are explored.

Introduction

Statistical analysis is necessary for any research project seeking to make quantitative conclusions. The following is a primer for research-based statistical analysis. It is intended to be a high-level overview of appropriate statistical testing, while not diving too deep into any specific methodology. Some of the information is more applicable to retrospective projects, where analysis is performed on data that has already been collected, but most of it will be suitable to any type of research. This primer will help the reader understand research results in coordination with a statistician, not to perform the actual analysis. Analysis is commonly performed using statistical programming software such as R, SAS or SPSS. These allow for analysis to be replicated while minimizing the risk for an error. Resources are listed later for those working on analysis without a statistician.

After coming up with a hypothesis for a study, including any variables to be used, one of the first steps is to think about the patient population to apply the question. Results are only relevant to the population that the underlying data represents. Since it is impractical to include everyone with a certain condition, a subset of the population of interest should be taken. This subset should be large enough to have power, which means there is enough data to deliver significant results and accurately reflect the study’s population.

The first statistics of interest are related to significance level and power, alpha and beta. Alpha (α) is the significance level and probability of a type I error, the rejection of the null hypothesis when it is true. The null hypothesis is generally that there is no difference between the groups compared. A type I error is also known as a false positive. An example would be an analysis that finds one medication statistically better than another, when in reality there is no difference in efficacy between the two. Beta (β) is the probability of a type II error, the failure to reject the null hypothesis when it is actually false. A type II error is also known as a false negative. This occurs when the analysis finds there is no difference in two medications when in reality one works better than the other. Power is defined as 1-β and should be calculated prior to running any sort of statistical testing. Ideally, alpha should be as small as possible while power should be as large as possible. Power generally increases with a larger sample size, but so does cost and the effect of any bias in the study design. Additionally, as the sample size gets bigger, the chance for a statistically significant result goes up even though these results can be small differences that do not matter practically. Power calculators include the magnitude of the effect in order to combat the potential for exaggeration and only give significant results that have an actual impact. The calculators take inputs like the mean, effect size and desired power, and output the required minimum sample size for analysis. Effect size is calculated using statistical information on the variables of interest. If that information is not available, most tests have commonly used values for small, medium or large effect sizes.

When the desired patient population is decided, the next step is to define the variables previously chosen to be included. Variables come in different types that determine which statistical methods are appropriate and useful. One way variables can be split is into categorical and quantitative variables. ( Table 1 ) Categorical variables place patients into groups, such as gender, race and smoking status. Quantitative variables measure or count some quantity of interest. Common quantitative variables in research include age and weight. An important note is that there can often be a choice for whether to treat a variable as quantitative or categorical. For example, in a study looking at body mass index (BMI), BMI could be defined as a quantitative variable or as a categorical variable, with each patient’s BMI listed as a category (underweight, normal, overweight, and obese) rather than the discrete value. The decision whether a variable is quantitative or categorical will affect what conclusions can be made when interpreting results from statistical tests. Keep in mind that since quantitative variables are treated on a continuous scale it would be inappropriate to transform a variable like which medication was given into a quantitative variable with values 1, 2 and 3.

Categorical vs. Quantitative Variables

| Categorical Variables | Quantitative Variables |

|---|---|

| Categorize patients into discrete groups | Continuous values that measure a variable |

| Patient categories are mutually exclusive | For time based studies, there would be a new variable for each measurement at each time |

| Examples: race, smoking status, demographic group | Examples: age, weight, heart rate, white blood cell count |

Both of these types of variables can also be split into response and predictor variables. ( Table 2 ) Predictor variables are explanatory, or independent, variables that help explain changes in a response variable. Conversely, response variables are outcome, or dependent, variables whose changes can be partially explained by the predictor variables.

Response vs. Predictor Variables

| Response Variables | Predictor Variables |

|---|---|

| Outcome variables | Explanatory variables |

| Should be the result of the predictor variables | Should help explain changes in the response variables |

| One variable per statistical test | Can be multiple variables that may have an impact on the response variable |

| Can be categorical or quantitative | Can be categorical or quantitative |

Choosing the correct statistical test depends on the types of variables defined and the question being answered. The appropriate test is determined by the variables being compared. Some common statistical tests include t-tests, ANOVA and chi-square tests.

T-tests compare whether there are differences in a quantitative variable between two values of a categorical variable. For example, a t-test could be useful to compare the length of stay for knee replacement surgery patients between those that took apixaban and those that took rivaroxaban. A t-test could examine whether there is a statistically significant difference in the length of stay between the two groups. The t-test will output a p-value, a number between zero and one, which represents the probability that the two groups could be as different as they are in the data, if they were actually the same. A value closer to zero suggests that the difference, in this case for length of stay, is more statistically significant than a number closer to one. Prior to collecting the data, set a significance level, the previously defined alpha. Alpha is typically set at 0.05, but is commonly reduced in order to limit the chance of a type I error, or false positive. Going back to the example above, if alpha is set at 0.05 and the analysis gives a p-value of 0.039, then a statistically significant difference in length of stay is observed between apixaban and rivaroxaban patients. If the analysis gives a p-value of 0.91, then there was no statistical evidence of a difference in length of stay between the two medications. Other statistical summaries or methods examine how big of a difference that might be. These other summaries are known as post-hoc analysis since they are performed after the original test to provide additional context to the results.

Analysis of variance, or ANOVA, tests can observe mean differences in a quantitative variable between values of a categorical variable, typically with three or more values to distinguish from a t-test. ANOVA could add patients given dabigatran to the previous population and evaluate whether the length of stay was significantly different across the three medications. If the p-value is lower than the designated significance level then the hypothesis that length of stay was the same across the three medications is rejected. Summaries and post-hoc tests also could be performed to look at the differences between length of stay and which individual medications may have observed statistically significant differences in length of stay from the other medications. A chi-square test examines the association between two categorical variables. An example would be to consider whether the rate of having a post-operative bleed is the same across patients provided with apixaban, rivaroxaban and dabigatran. A chi-square test can compute a p-value determining whether the bleeding rates were significantly different or not. Post-hoc tests could then give the bleeding rate for each medication, as well as a breakdown as to which specific medications may have a significantly different bleeding rate from each other.

A slightly more advanced way of examining a question can come through multiple regression. Regression allows more predictor variables to be analyzed and can act as a control when looking at associations between variables. Common control variables are age, sex and any comorbidities likely to affect the outcome variable that are not closely related to the other explanatory variables. Control variables can be especially important in reducing the effect of bias in a retrospective population. Since retrospective data was not built with the research question in mind, it is important to eliminate threats to the validity of the analysis. Testing that controls for confounding variables, such as regression, is often more valuable with retrospective data because it can ease these concerns. The two main types of regression are linear and logistic. Linear regression is used to predict differences in a quantitative, continuous response variable, such as length of stay. Logistic regression predicts differences in a dichotomous, categorical response variable, such as 90-day readmission. So whether the outcome variable is categorical or quantitative, regression can be appropriate. An example for each of these types could be found in two similar cases. For both examples define the predictor variables as age, gender and anticoagulant usage. In the first, use the predictor variables in a linear regression to evaluate their individual effects on length of stay, a quantitative variable. For the second, use the same predictor variables in a logistic regression to evaluate their individual effects on whether the patient had a 90-day readmission, a dichotomous categorical variable. Analysis can compute a p-value for each included predictor variable to determine whether they are significantly associated. The statistical tests in this article generate an associated test statistic which determines the probability the results could be acquired given that there is no association between the compared variables. These results often come with coefficients which can give the degree of the association and the degree to which one variable changes with another. Most tests, including all listed in this article, also have confidence intervals, which give a range for the correlation with a specified level of confidence. Even if these tests do not give statistically significant results, the results are still important. Not reporting statistically insignificant findings creates a bias in research. Ideas can be repeated enough times that eventually statistically significant results are reached, even though there is no true significance. In some cases with very large sample sizes, p-values will almost always be significant. In this case the effect size is critical as even the smallest, meaningless differences can be found to be statistically significant.

These variables and tests are just some things to keep in mind before, during and after the analysis process in order to make sure that the statistical reports are supporting the questions being answered. The patient population, types of variables and statistical tests are all important things to consider in the process of statistical analysis. Any results are only as useful as the process used to obtain them. This primer can be used as a reference to help ensure appropriate statistical analysis.

| Alpha (α) | the significance level and probability of a type I error, the probability of a false positive |

| Analysis of variance/ANOVA | test observing mean differences in a quantitative variable between values of a categorical variable, typically with three or more values to distinguish from a t-test |

| Beta (β) | the probability of a type II error, the probability of a false negative |

| Categorical variable | place patients into groups, such as gender, race or smoking status |

| Chi-square test | examines association between two categorical variables |

| Confidence interval | a range for the correlation with a specified level of confidence, 95% for example |

| Control variables | variables likely to affect the outcome variable that are not closely related to the other explanatory variables |

| Hypothesis | the idea being tested by statistical analysis |

| Linear regression | regression used to predict differences in a quantitative, continuous response variable, such as length of stay |

| Logistic regression | regression used to predict differences in a dichotomous, categorical response variable, such as 90-day readmission |

| Multiple regression | regression utilizing more than one predictor variable |

| Null hypothesis | the hypothesis that there are no significant differences for the variable(s) being tested |

| Patient population | the population the data is collected to represent |

| Post-hoc analysis | analysis performed after the original test to provide additional context to the results |

| Power | 1-beta, the probability of avoiding a type II error, avoiding a false negative |

| Predictor variable | explanatory, or independent, variables that help explain changes in a response variable |

| p-value | a value between zero and one, which represents the probability that the null hypothesis is true, usually compared against a significance level to judge statistical significance |

| Quantitative variable | variable measuring or counting some quantity of interest |

| Response variable | outcome, or dependent, variables whose changes can be partially explained by the predictor variables |

| Retrospective study | a study using previously existing data that was not originally collected for the purposes of the study |

| Sample size | the number of patients or observations used for the study |

| Significance level | alpha, the probability of a type I error, usually compared to a p-value to determine statistical significance |

| Statistical analysis | analysis of data using statistical testing to examine a research hypothesis |

| Statistical testing | testing used to examine the validity of a hypothesis using statistical calculations |

| Statistical significance | determine whether to reject the null hypothesis, whether the p-value is below the threshold of a predetermined significance level |

| T-test | test comparing whether there are differences in a quantitative variable between two values of a categorical variable |

Funding Statement

This research was supported (in whole or in part) by HCA Healthcare and/or an HCA Healthcare affiliated entity.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares he has no conflicts of interest.

Christian Vandever is an employee of HCA Healthcare Graduate Medical Education, an organization affiliated with the journal’s publisher.

This research was supported (in whole or in part) by HCA Healthcare and/or an HCA Healthcare affiliated entity. The views expressed in this publication represent those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of HCA Healthcare or any of its affiliated entities.

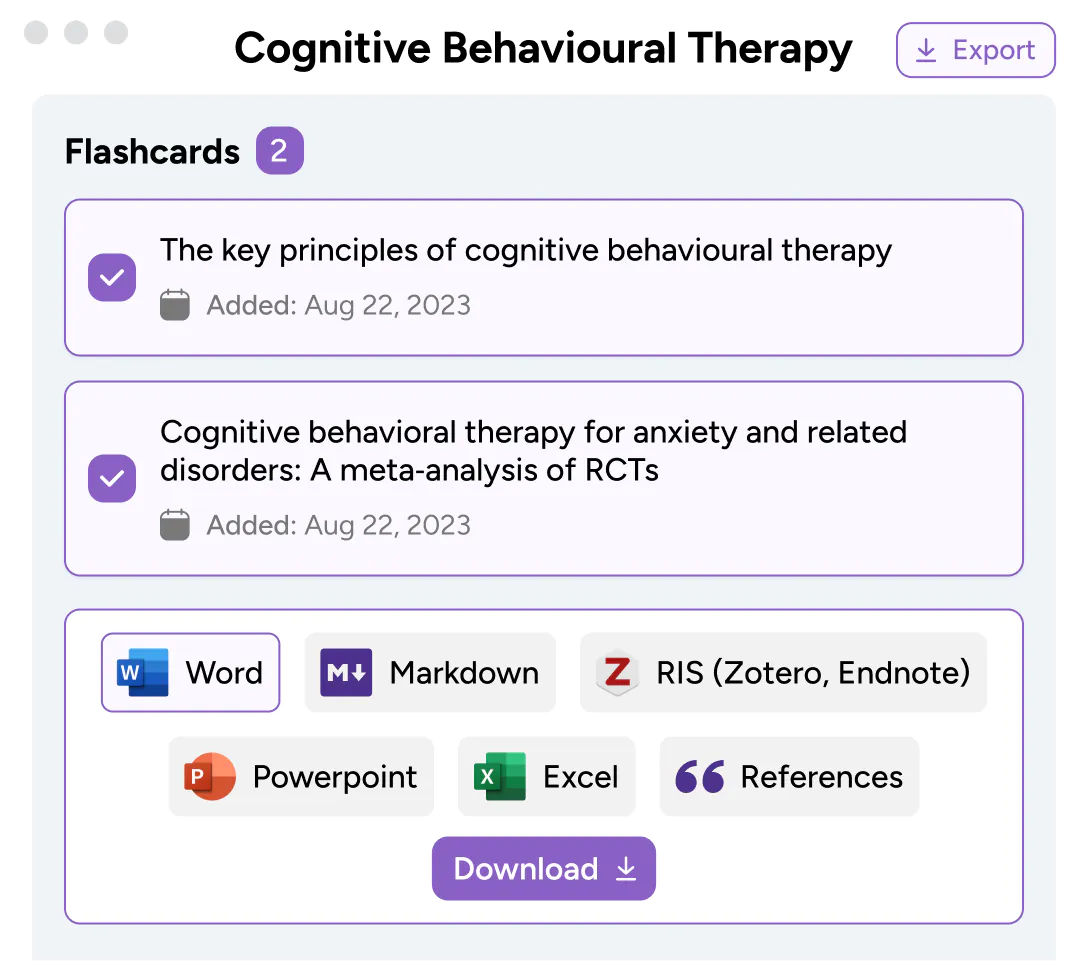

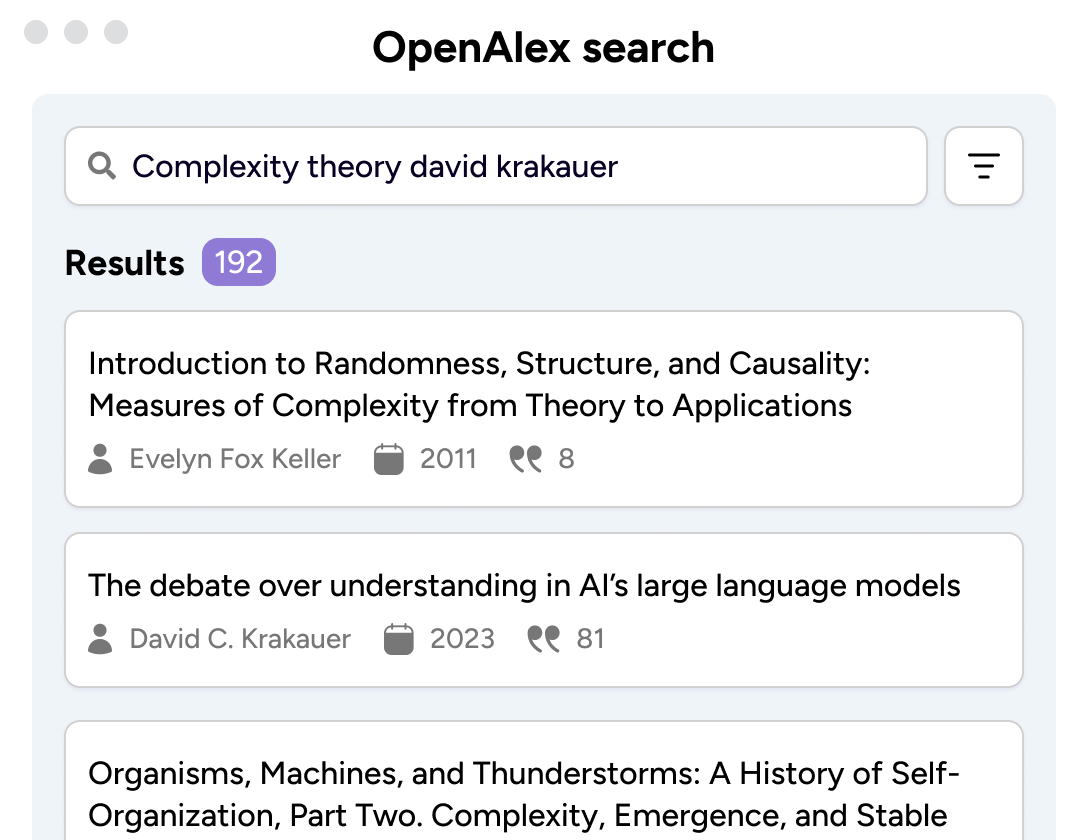

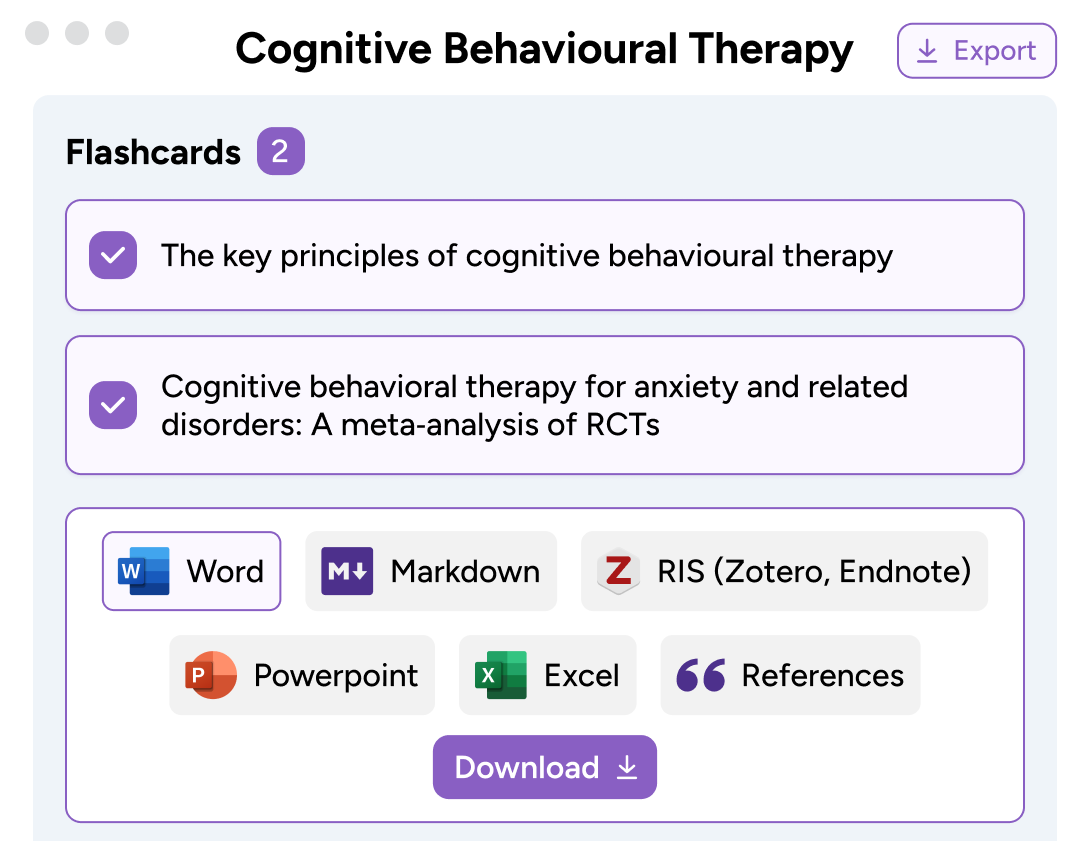

Extract key information from research papers with our AI summarizer.

Get a snapshot of what matters – fast . Break down complex concepts into easy-to-read sections. Skim or dive deep with a clean reading experience.

Summarize, analyze, and organize your research in one place.

Features built for scholars like you, trusted by researchers and students around the world.

Summarize papers, PDFs, book chapters, online articles and more.

Easy import

Drag and drop files, enter the url of a page, paste a block of text, or use our browser extension.

Enhanced summary

Change the summary to suit your reading style. Choose from a bulleted list, one-liner and more.

Read the key points of a paper in seconds with confidence that everything you read comes from the original text.

Clean reading

Clutter free flashcards help you skim or diver deeper into the details and quickly jump between sections.

Highlighted key terms and findings. Let evidence-based statements guide you through the full text with confidence.

Summarize texts in any format

Scholarcy’s ai summarization tool is designed to generate accurate, reliable article summaries..

Our summarizer tool is trained to identify key terms, claims, and findings in academic papers. These insights are turned into digestible Summary Flashcards.

Scroll in the box below to see the magic ⤸

The knowledge extraction and summarization methods we use focus on accuracy. This ensures what you read is factually correct, and can always be traced back to the original source .

What students say

It would normally take me 15mins – 1 hour to skim read the article but with Scholarcy I can do that in 5 minutes.

Scholarcy makes my life easier because it pulls out important information in the summary flashcard.

Scholarcy is clear and easy to navigate. It helps speed up the process of reading and understating papers.

Join over 400,000 people already saving time.

From a to z with scholarcy, generate flashcard summaries. discover more aha moments. get to point quicker..

Understand complex research. Jump between key concepts and sections. Highlight text. Take notes.

Build a library of knowledge. Recall important info with ease. Organize, search, sort, edit.

Bring it all together. Export Flashcards in a range of formats. Transfer Flashcards into other apps.

Apply what you’ve learned. Compile your highlights, notes, references. Write that magnum opus 🤌

Go beyond summaries

Get unlimited summaries, advanced research and analysis features, and your own personalised collection with Scholarcy Library!

With Scholarcy Library you can import unlimited documents and generate summaries for all your course materials or collection of research papers.

Scholarcy Library offers additional features including access to millions of academic research papers, customizable summaries, direct import from Zotero and more.

Scholarcy lets you build and organise your summaries into a handy library that you can access from anywhere. Export from a range of options, including one-click bibliographies and even a literature matrix.

Compare plans

Summarize 3 articles a day with our free summarizer tool, or upgrade to Scholarcy Library to generate and save unlimited article summaries.

Import a range of file formats

Export flashcards (one at a time)

Everything in Free

Unlimited summarization

Generate enhanced summaries

Save your flashcards

Take notes, highlight and edit text

Organize flashcards into collections

Frequently Asked Questions

How do i use scholarcy, what if i’m having issues importing files, can scholarcy generate a plain language summary of the article, can scholarcy process any size document, how do i change the summary to get better results, what if i upload a paywalled article to scholarcy, is it violating copyright laws.

Explore millions of high-quality primary sources and images from around the world, including artworks, maps, photographs, and more.

Explore migration issues through a variety of media types

- Part of The Streets are Talking: Public Forms of Creative Expression from Around the World

- Part of The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Winter 2020)

- Part of Cato Institute (Aug. 3, 2021)

- Part of University of California Press

- Part of Open: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Part of Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, Vol. 19, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

- Part of R Street Institute (Nov. 1, 2020)

- Part of Leuven University Press

- Part of UN Secretary-General Papers: Ban Ki-moon (2007-2016)

- Part of Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol. 12, No. 4 (August 2018)

- Part of Leveraging Lives: Serbia and Illegal Tunisian Migration to Europe, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (Mar. 1, 2023)

- Part of UCL Press

Harness the power of visual materials—explore more than 3 million images now on JSTOR.

Enhance your scholarly research with underground newspapers, magazines, and journals.

Explore collections in the arts, sciences, and literature from the world’s leading museums, archives, and scholars.

Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice

- Read this journal

- Journal snapshot

- Advertising information

Journal scope statement

Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice is a multidisciplinary journal committed to increasing the communication between the subdisciplines within behavior analysis and psychology, and bringing up-to-date information on current developments within the field.

It publishes original research, reviews of the discipline, theoretical and conceptual work, applied research, translational research, program descriptions, research in organizations and the community, clinical work, and curricular developments.

Areas of interest include, but are not limited to, clinical behavior analysis, applied and translational behavior analysis, behavior therapy, behavioral consultation, organizational behavior management, and human performance technology.

Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice presents current experimental and translational research, and applications of behavioral analysis, in ways that can improve human behavior in all its contexts: across the developmental continuum in organizational, community, residential, clinical, and any other settings in which the fruits of behavior analysis can make a positive contribution.

The journal also provides a focused view of behavioral consultation and therapy for the general behavioral intervention community. Additionally, the journal highlights the importance of conducting clinical research from a strong theoretical base. Additional topic areas of interest include contextual research, third-wave research, and clinical articles.

For more information regarding submissions to Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice , please visit the Types of Articles Accepted by Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice page.

Disclaimer: APA and the editors of the Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice assume no responsibility for statements and opinions advanced by the authors of its articles.

Equity, diversity, and inclusion

Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice supports equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) in its practices. More information on these initiatives is available under EDI Efforts .

Editor’s Choice

One article from each issue of Behavioral Analysis: Research and Practice will be highlighted as an “ Editor’s Choice ” article. Selection is based on the recommendations of the associate editors, the paper’s potential impact to the field, the distinction of expanding the contributors to, or the focus of, the science, or its discussion of an important future direction for science. Editor’s Choice articles are featured alongside articles from other APA published journals in a bi-weekly newsletter and are temporarily made freely available to newsletter subscribers.

Author and editor spotlights

Explore journal highlights : free article summaries, editor interviews and editorials, journal awards, mentorship opportunities, and more.

Prior to submission, please carefully read and follow the submission guidelines detailed below. Manuscripts that do not conform to the submission guidelines may be returned without review.

To submit to the editorial office of Joel E. Ringdahl, please submit manuscripts electronically through the Manuscript Submission Portal in Microsoft Word or Open Office format.

Prepare manuscripts according to the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association using the 7 th edition. Manuscripts may be copyedited for bias-free language (see Chapter 5 of the Publication Manual ). APA Style and Grammar Guidelines for the 7 th edition are available.

Submit Manuscript

Joel E. Ringdahl, PhD, BCBA Associate Professor Special Education 565 Aderhold Hall University of Georgia Email

General correspondence may be directed to the editorial's office .

In addition to addresses and phone numbers, please supply email addresses, as most communications will be by email.

Manuscript preparation

Review APA's Journal Manuscript Preparation Guidelines before submitting your article.

If your manuscript was mask reviewed, please ensure that the final version for production includes a byline and full author note for typesetting.

Double-space all copy. Other formatting instructions, as well as instructions on preparing tables, figures, references, metrics, and abstracts, appear in the Manual . Additional guidance on APA Style is available on the APA Style website .

Below are additional instructions regarding the preparation of display equations, computer code, and tables.

Display equations

We strongly encourage you to use MathType (third-party software) or Equation Editor 3.0 (built into pre-2007 versions of Word) to construct your equations, rather than the equation support that is built into Word 2007 and Word 2010. Equations composed with the built-in Word 2007/Word 2010 equation support are converted to low-resolution graphics when they enter the production process and must be rekeyed by the typesetter, which may introduce errors.

To construct your equations with MathType or Equation Editor 3.0:

- Go to the Text section of the Insert tab and select Object.

- Select MathType or Equation Editor 3.0 in the drop-down menu.

If you have an equation that has already been produced using Microsoft Word 2007 or 2010 and you have access to the full version of MathType 6.5 or later, you can convert this equation to MathType by clicking on MathType Insert Equation. Copy the equation from Microsoft Word and paste it into the MathType box. Verify that your equation is correct, click File, and then click Update. Your equation has now been inserted into your Word file as a MathType Equation.

Use Equation Editor 3.0 or MathType only for equations or for formulas that cannot be produced as Word text using the Times or Symbol font.

Computer code

Because altering computer code in any way (e.g., indents, line spacing, line breaks, page breaks) during the typesetting process could alter its meaning, we treat computer code differently from the rest of your article in our production process. To that end, we request separate files for computer code.

In online supplemental material

We request that runnable source code be included as supplemental material to the article. For more information, visit Supplementing Your Article With Online Material .

In the text of the article

If you would like to include code in the text of your published manuscript, please submit a separate file with your code exactly as you want it to appear, using Courier New font with a type size of 8 points. We will make an image of each segment of code in your article that exceeds 40 characters in length. (Shorter snippets of code that appear in text will be typeset in Courier New and run in with the rest of the text.) If an appendix contains a mix of code and explanatory text, please submit a file that contains the entire appendix, with the code keyed in 8-point Courier New.

Use Word's insert table function when you create tables. Using spaces or tabs in your table will create problems when the table is typeset and may result in errors.

Academic writing and English language editing services

Authors who feel that their manuscript may benefit from additional academic writing or language editing support prior to submission are encouraged to seek out such services at their host institutions, engage with colleagues and subject matter experts, and/or consider several vendors that offer discounts to APA authors .

Please note that APA does not endorse or take responsibility for the service providers listed. It is strictly a referral service.

Use of such service is not mandatory for publication in an APA journal. Use of one or more of these services does not guarantee selection for peer review, manuscript acceptance, or preference for publication in any APA journal.

Submitting supplemental materials

APA can place supplemental materials online, available via the published article in the PsycArticles ® database. Please see Supplementing Your Article With Online Material for more details.

Abstract and keywords

All manuscripts must include an abstract containing a maximum of 250 words typed on a separate page. After the abstract, please supply up to five keywords or brief phrases.

List references in alphabetical order. Each listed reference should be cited in text, and each text citation should be listed in the references section.

Examples of basic reference formats:

Journal article

McCauley, S. M., & Christiansen, M. H. (2019). Language learning as language use: A cross-linguistic model of child language development. Psychological Review , 126 (1), 1–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000126

Authored book

Brown, L. S. (2018). Feminist therapy (2nd ed.). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000092-000

Chapter in an edited book

Balsam, K. F., Martell, C. R., Jones. K. P., & Safren, S. A. (2019). Affirmative cognitive behavior therapy with sexual and gender minority people. In G. Y. Iwamasa & P. A. Hays (Eds.), Culturally responsive cognitive behavior therapy: Practice and supervision (2nd ed., pp. 287–314). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000119-012

Preferred formats for graphics files are TIFF and JPG, and preferred format for vector-based files is EPS. Graphics downloaded or saved from web pages are not acceptable for publication. Multipanel figures (i.e., figures with parts labeled a, b, c, d, etc.) should be assembled into one file. When possible, please place symbol legends below the figure instead of to the side.

- All color line art and halftones: 300 DPI

- Black and white line tone and gray halftone images: 600 DPI

Line weights

- Color (RGB, CMYK) images: 2 pixels

- Grayscale images: 4 pixels

- Stroke weight: 0.5 points

APA offers authors the option to publish their figures online in color without the costs associated with print publication of color figures.

The same caption will appear on both the online (color) and print (black and white) versions. To ensure that the figure can be understood in both formats, authors should add alternative wording (e.g., “the red (dark gray) bars represent”) as needed.

For authors who prefer their figures to be published in color both in print and online, original color figures can be printed in color at the editor's and publisher's discretion provided the author agrees to pay:

- $900 for one figure

- An additional $600 for the second figure

- An additional $450 for each subsequent figure

Permissions

Authors of accepted papers must obtain and provide to the editor on final acceptance all necessary permissions to reproduce in print and electronic form any copyrighted work, including test materials (or portions thereof), photographs, and other graphic images (including those used as stimuli in experiments).

On advice of counsel, APA may decline to publish any image whose copyright status is unknown.

- Download Permissions Alert Form (PDF, 13KB)

Publication policies

For full details on publication policies, including use of Artificial Intelligence tools, please see APA Publishing Policies .

APA policy prohibits an author from submitting the same manuscript for concurrent consideration by two or more publications.

See also APA Journals ® Internet Posting Guidelines .

APA requires authors to reveal any possible conflict of interest in the conduct and reporting of research (e.g., financial interests in a test or procedure, funding by pharmaceutical companies for drug research).

- Download Full Disclosure of Interests Form (PDF, 41KB)

In light of changing patterns of scientific knowledge dissemination, APA requires authors to provide information on prior dissemination of the data and narrative interpretations of the data/research appearing in the manuscript (e.g., if some or all were presented at a conference or meeting, posted on a listserv, shared on a website, including academic social networks like ResearchGate, etc.). This information (2–4 sentences) must be provided as part of the author note.

Ethical Principles

It is a violation of APA Ethical Principles to publish "as original data, data that have been previously published" (Standard 8.13).

In addition, APA Ethical Principles specify that "after research results are published, psychologists do not withhold the data on which their conclusions are based from other competent professionals who seek to verify the substantive claims through reanalysis and who intend to use such data only for that purpose, provided that the confidentiality of the participants can be protected and unless legal rights concerning proprietary data preclude their release" (Standard 8.14).

APA expects authors to adhere to these standards. Specifically, APA expects authors to have their data available throughout the editorial review process and for at least 5 years after the date of publication.

Authors are required to state in writing that they have complied with APA ethical standards in the treatment of their sample, human or animal, or to describe the details of treatment.

- Download Certification of Compliance With APA Ethical Principles Form (PDF, 26KB)

The APA Ethics Office provides the full Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct electronically on its website in HTML, PDF, and Word format. You may also request a copy by emailing or calling the APA Ethics Office (202-336-5930). You may also read "Ethical Principles," December 1992, American Psychologist , Vol. 47, pp. 1597–1611.

Other information

See APA’s Publishing Policies page for more information on publication policies, including information on author contributorship and responsibilities of authors, author name changes after publication, the use of generative artificial intelligence, funder information and conflict-of-interest disclosures, duplicate publication, data publication and reuse, and preprints.

Visit the Journals Publishing Resource Center for more resources for writing, reviewing, and editing articles for publishing in APA journals.

Joel E. Ringdahl University of Georgia, United States

Associate editors

Jonathan C. Baker, PhD, BCBA-D Western Michigan University, United States

Andrew R. Craig, PhD SUNY Upstate Medical University, United States

Kelly Schieltz, PhD University of Iowa, United States

Maria G. Valdovinos, PhD, BCBA-D Drake University, United States

Consulting editors

Keith D. Allen, PhD, BCBA-D Munroe-Meyer Institute for Genetics and Rehabilitation, United States

Cynthia M. Anderson, PhD, BCBA-D May Institute, United States

Scott P. Ardoin, PhD, BCBA-D University of Georgia, United States

Jennifer Austin, PhD, BCBA-D Georgia State University, United Kingdom

Judah Axe, PhD, BCBA-D, LABA Simmons University, United States

Jessica Becraft, PhD Kennedy Krieger Institute, United States

Kevin Michael Ayres, PhD, BCBA-D The University of Georgia, United States

Jordan Belisle, PhD, BCBA, LBA Missouri State University, United States

Carrie S.W. Borrero, PhD, BCBA-D, LBA Kennedy Krieger Institute, United States

Rachel R. Cagliani, PhD, BCBA-D University of Georgia, United States

Regina Carroll, PhD University of Nebraska Medical Center, United States

Joseph D. Cautilli, PhD Behavior Analysis and Therapy Partners, United States

Linda J. Cooper-Brown, PhD University of Iowa, United States

Casey Clay, PhD, BCBA-D Utah State University, United States

Mack S. Costello, PhD, BCBA-D Rider University, United States

Neil Deochand, PhD University of Cincinnati, United States

Florence D. DiGennaro Reed, PhD, BCBA-D University of Kansas, United States

Mark R. Dixon, PhD, BCBA-D Southern Illinois University, United States

Jeanne M. Donaldson, PhD, BCBA-D, LBA Louisiana State University, United States

Claudia L. Dozier, PhD BCBA-D, LBA-KS University of Kansas, United States

Anuradha Dutt, PhD Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

Terry S. Falcomata, PhD University of Texas at Austin, United States

Margaret R. Gifford, PhD Louisiana State University Shreveport, United States

Shawn P. Gilroy, PhD NCSP BCBA-D LP Louisiana State University, United States

Kaitlin Gould, PhD, BCBA-D The College of St. Rose, United States

John Guercio, PhD, BCBA-D Benchmark Human Services, United States

Louis Hagopian, PhD Kennedy Krieger Institute and Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, United States

Thomas S. Higbee, Ph.D., BCBA-D Utah State University, United States

Joshua Jessel Queens College, City University of New York, United States

P. Raymond Joslyn, PhD West Virginia University, United States

Michael E. Kelley, PhD, BCBA-D, LP University of Scranton, United States

Carolynn S. Kohn, PhD University of the Pacific, United States

Michael P. Kranak, PhD, BCBA-D Oakland University Center for Autism, United States

Joseph M. Lambert, PhD, BCBA-D Vanderbilt University, United States

Robert LaRue, PhD Rutgers University, United States

Anita Li, PhD University of Massachusetts Lowell, United States

Joanna Lomas Mevers, PhD, BCBA-D Marcus Autism Center, United States

Odessa Luna, BCBA-D, PhD St. Cloud State University, United States

David B. McAdam, PhD University of Rochester, United States

Jennifer McComas, PhD University of Minnesota, United States

Brandon E. McCord, PhD, BCBA-D, LBA West Tennessee Community Homes, United States

Heather M. McGee, PhD Western Michigan University, United States

Raymond G. Miltenberger, PhD University of South Florida, United States

Daniel R. Mitteer, PhD, BCBA-D Children's Specialized Hospital and Rutgers University Center for Autism Research, Education, and Services, United States

Samuel L. Morris, PhD, BCBA Louisiana State University, United States

Matthew Normand, Ph.D., BCBA-D University of the Pacific, United States

Matthew J. O’Brien, PhD, BCBA-D University of Iowa, United States

Yaniz Padilla Dalmau, PhD, BCBA-D Seattle Children’s Hospital, United States

Steven W. Payne, PhD, BCBA-D University of Nevada, Las Vegas, United States

Sacha T. Pence, PhD Western Michigan University, United States

Christopher A. Podlesnik, PhD, BCBA-D University of Florida, United States

Shawn Quigley, PhD, BCBA-D, CDE Melmark, United States

Allie E. Rader, PhD, BCBA-D May Institute, United States

Mark P. Reilly, PhD Central Michigan University, United States

Patrick W. Romani, PhD, BCBA-D University of Colorado School of Medicine, United States

Griffin Wesley Rooker, PhD, BCBA Mount St. Mary's University, United States

Valdeep Saini, PhD Brock University, Canada

Mindy Scheithauer, PhD, BCBA-D Emory University School of Medicine and Marcus Autism Center, United States

Daniel B. Shabani, PhD, BCBA-D Shabani Institute, United States

M. Alice Shillingsburg, PhD, BCBA-D University of Nebraska Medical Center, United States

Sarah Slocum Freeman, PhD, BCBA-D Emory University and Marcus Autism Center, United States

Julie M. Slowiak, PhD, BCBA-D University of Minnesota Duluth, United States

William E. Sullivan, PhD SUNY Upstate Medical University, United States

Jessica Torelli, PhD, BCBA-D University of Georgia, United States

Kristina K. Vargo, BCBA-D, LBA Sam Houston State University, United States