Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 5: The Literature Review

5.3 Acceptable sources for literature reviews

Following are a few acceptable sources for literature reviews, listed in order from what will be considered most acceptable to less acceptable sources for your literature review assignments:

- Peer reviewed journal articles.

- Edited academic books.

- Articles in professional journals.

- Statistical data from government websites.

- Website material from professional associations (use sparingly and carefully). The following sections will explain and provide examples of these various sources.

Peer reviewed journal articles (papers)

A peer reviewed journal article is a paper that has been submitted to a scholarly journal, accepted, and published. Peer review journal papers go through a rigorous, blind review process of peer review. What this means is that two to three experts in the area of research featured in the paper have reviewed and accepted the paper for publication. The names of the author(s) who are seeking to publish the research have been removed (blind review), so as to minimize any bias towards the authors of the research (albeit, sometimes a savvy reviewer can discern who has done the research based upon previous publications, etc.). This blind review process can be long (often 12 to 18 months) and may involve many back and forth edits on the behalf of the researchers, as they work to address the edits and concerns of the peers who reviewed their paper. Often, reviewers will reject the paper for a variety of reasons, such as unclear or questionable methods, lack of contribution to the field, etc. Because peer reviewed journal articles have gone through a rigorous process of review, they are considered to be the premier source for research. Peer reviewed journal articles should serve as the foundation for your literature review.

The following link will provide more information on peer reviewed journal articles. Make sure you watch the little video on the upper left-hand side of your screen, in addition to reading the material at the following website: http://guides.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/c.php?g=288333&p=1922599

Edited academic books

An edited academic book is a collection of scholarly scientific papers written by different authors. The works are original papers, not published elsewhere (“Edited volume,” 2018). The papers within the text also go through a process of review; however, the review is often not a blind review because the authors have been invited to contribute to the book. Consequently, edited academic books are fine to use for your literature review, but you also want to ensure that your literature review contains mostly peer reviewed journal papers.

Articles in professional journals

Articles from professional journals should be used with caution for your literature review. This is because articles in trade journals are not usually peer reviewed, even though they may appear to be. A good way to find out is to read the “About Us” section of the professional journal, which should state whether or not the papers are peer reviewed. You can also find out by Googling the name of the journal and adding “peer reviewed” to the search.

Statistical data from governmental websites

Governmental websites can be excellent sources for statistical data, e.g, Statistics Canada collects and publishes data related to the economy, society, and the environment (see https://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/start ).

Website material from professional associations

Material from other websites can also serve as a source for statistics that you may need for your literature review. Since you want to justify the value of the research that interests you, you might make use of a professional association’s website to learn how many members they have, for example. You might want to demonstrate, as part of the introduction to your literature review, why more research on the topic of PTSD in police officers is important. You could use peer reviewed journal articles to determine the prevalence of PTSD in police officers in Canada in the last ten years, and then use the Ontario Police Officers´ Association website to determine the approximate number of police officers employed in the Province of Ontario over the last ten years. This might help you estimate how many police officers could be suffering with PTSD in Ontario. That number could potentially help to justify a research grant down the road. But again, this type of website- based material should be used with caution and sparingly.

Research Methods for the Social Sciences: An Introduction Copyright © 2020 by Valerie Sheppard is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

How To Find A-Grade Literature For Review

Sourcing, evaluating and organising.

By: David Phair (PhD) and Peter Quella (PhD) | January 2022

As we’ve discussed previously on our blog and YouTube channel, the first step of the literature review process is to source high-quality , relevant resources for your review, and to catalogue these pieces of literature in a systematic way so that you can digest and synthesise all the content efficiently.

In this article, we’ll look discuss 6 important things to keep in mind for the initial stage of your literature review so that you can source high-quality, relevant resources, quickly and efficiently. Let’s get started!

Overview: Literature Review Sourcing

- Develop and follow a clear literature search strategy

- Understand and use different types of literature correctly

- Carefully evaluate the quality of your potential sources

- Use a reference manager and a literature catalogue

- Read as broadly and comprehensively as possible

- Keep your golden thread front of mind throughout the process

1. Have a clear literature search strategy

As with any task in the research process, you need to have a clear plan of action before you get started, or you’ll end up wasting a lot of time and energy. So, before you begin your literature review , it’s useful to develop a simple search strategy . Broadly speaking, a good literature search strategy should include the following steps:

Step one – Clearly identify your golden thread

Your golden thread consists of your research aims , research objectives and research questions . These three components should be tightly aligned to form the focus of your research. If you’re unclear what your research aims and research questions are, you’re not going to have a clear direction when trying to source literature. As a result, you’re going to waste a lot of time reviewing irrelevant resources.

So, make sure that you have clarity regarding your golden thread before you start searching for literature. Of course, your research aims, objectives and questions may evolve or shift as a result of the literature review process (in fact, this is quite common), but you still need to have a clear focus to get things started.

Step two – Develop a keyword/keyphrase list

Once you’ve clearly articulated your golden thread in terms of the research aims, objectives and questions, the next step is to develop a list of keywords or keyphrases, based on these three elements (the golden thread). You’ll also want to include synonyms and alternative spellings (for example, American vs British English) in your list.

For example, if your research aims and research questions involve investigating organisational trust , your keyword list might include:

- Organisational trust

- Organizational trust (US spelling)

- Consumer trust

- Brand trust

- Online trust

When it comes to brainstorming keywords, the more the better . Don’t hold back at this stage. You’ll quickly find out which ones are useful, and which aren’t when you start searching. So, it’s best to just go as broad as possible here to ensure you cast a wide net.

Step three – Identify the relevant databases

Now that you’ve got a comprehensive set of keywords, the next step is to identify which literature databases will be most useful and relevant for your particular study. There are hundreds, if not thousands of databases out there, and they are often subject or discipline-specific . For example, within the medicine space, Medline is a popular one.

To identify relevant databases, it’s best to speak to your research advisor/supervisor, Grad Coach or a librarian at your university library. Oftentimes, a quick chat with a skilled librarian can yield tremendous insight. Don’t be shy to ask – chances are, they’ll be thrilled that you asked!

At this stage, you might be asking, “why not just use Google Scholar?”. Of course, an academic search engine like Google Scholar will be useful in terms of getting started and finding a broad range of resources, but it won’t always present every possible resource or the best quality resources. It also has limited filtering options compared to some of the specialist databases, so you shouldn’t rely purely on Google Scholar.

Step four – Use Boolean operators to refine your search

Once you’ve identified your keywords and databases, it’s time to start searching for literature – hooray! However, you’ll quickly find that there is a seemingly endless number of journal articles to sift through, and you have limited time to work through the literature. So, you’ll need to get smart about how you use these databases – enter Boolean operators.

Boolean operators are special characters that allow you to refine your search. Common operators include:

- AND – only show results that contain both X and Y

- OR – show results that contain X or Y

- NOT – show results that include X, but not Y

These operators are incredibly useful, especially when there are topics that are very similar to yours but are not relevant . For example, if you’re researching something about the growth of apples, you’ll want to exclude all literature related to Apple, the company. Boolean operators allow you to cut out the irrelevant content and improve the signal to noise ratio in your search.

Need a helping hand?

2. Use different types of literature correctly

Once you start searching for literature, you’ll quickly notice that there are different “types” of resources that come up. It’s important to understand the different types of literature available to you and how to use each of them appropriately.

Generally speaking, you’ll find three categories of literature:

Primary literature

Secondary literature

Tertiary literature

Primary literature refers to journal articles , typically peer reviewed, which document a study that was undertaken, where data were collected and analysed, and findings were discussed. For example, a journal article that involves the collection and analysis of survey data to identify differences in personality between two groups of people.

Primary literature should, ideally, form the foundation of your literature review – the bread and butter, so to speak. You’ll likely refer to many of the arguments made and findings identified in these types of articles to build your own arguments throughout your literature review. You’ll also rely on these types of articles for theoretical models and frameworks, which may form the foundation of your own proposed framework, depending on the nature of your research.

Lastly, primary literature can be a useful source of measurement scales for quantitative studies. For example, many journal articles will include a copy of the survey measures they used at the end of the article, which will typically be reliable and valid. You can either use these “as is” or as a foundation for your own survey measures .

So, long story short, you’ll need a good stockpile of these types of resources. They are, admittedly, more “dense” and challenging to digest than the other types of literature, but taking the time to work through them will pay off greatly.

Secondary literature refers to journal articles that summarise and integrate the findings from primary literature. For example, you’ll likely find “review of the literature” type journal articles which provide an overview of the current state of the research (at the time of publication, of course).

Secondary literature is very useful for orienting yourself with regards to the current state of knowledge and identifying key researchers , seminal works and so on. In other words, they’re a good tool to make sure you’ve got a broad, comprehensive view of what all is out there. They’re not going to give you the level of detail that primary literature will (and they’ll likely be a bit outdated), but they’ll point you in the right direction.

In practical terms, it’s a good idea to start by reviewing secondary literature-type articles to help you get a bird’s eye view of the landscape and then dive deeper into the primary literature to get a grasp of the specifics and to bring your knowledge up to date with the most current studies.

The final category of literature refers to sources that would be considered less academic and scientifically rigorous in nature, but up to date and highly relevant. For example, sources such as current industry and country reports published by management consulting groups, news articles, blog posts and so on.

While these sources are not as credible and trustworthy as journal articles (especially peer-reviewed ones), they can provide very up to date information , whereas academic research tends to roll out quite slowly. Therefore, they can be very useful for contextualising your research topic and/or demonstrating a current trend. Quite often, you’d cite these types of sources in your introduction chapter rather than your literature review chapter, but you may still have use for them in the latter.

In summary, it’s important to understand the three different types of literature – primary, secondary and tertiary, and use them appropriately in your dissertation, thesis or research project.

3. Carefully evaluate the quality of your sources

As we’ve alluded to, not all literature is created equally. Not only does literature vary in terms of type (i.e., primary vs secondary), it also varies in terms of overall quality .

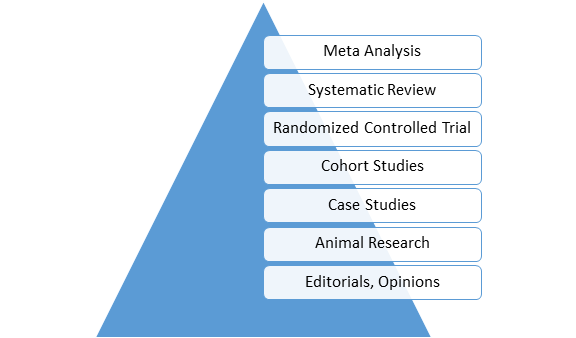

Simply put, all sources exist on a quality spectrum . On the high end of the spectrum are peer-reviewed articles published in popular, credible journals. Next are journal articles that are not peer-reviewed, or that are published in lower quality or lesser-known journals. In the middle are sources like textbooks and reports by professional organisations (e.g., management consulting firms). On the low end are sources like newspapers, blog posts and social media posts.

As you can probably see, this loosely reflects the categories we mentioned previously (primary, secondary and tertiary literature), so there is once again a trade-off between quality and recency . Therefore, you need to carefully evaluate the quality of each potential source and let this inform how you use it in your literature review. Importantly, this doesn’t mean that you can’t include a newspaper article or blog post as a source – it just means that you shouldn’t rely too heavily on these types of courses as the core of your argument.

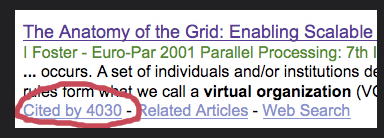

When evaluating journal articles, you can consider their citation count (i.e., the number of other articles that reference them) as a quality indicator. But keep in mind that citation count is a product of many factors , including the popularity of the article, the popularity of the research field and most importantly, time. In other words, it’s natural for newer articles to have lower citation counts. This is useful to keep in mind, as you ideally want to focus on more recent literature (published within the last 3-5 years) in your literature review.

In summary, aim to focus on higher-quality literature , especially when you’re building core arguments in your literature review. You don’t, for example, want to make an argument regarding the importance and novelty of your research (i.e., its justification) based on some blogger’s opinion.

4. Use a reference manager and literature catalogue

As you review the literature and build your collection of potential sources, you’ll need a way to stay on top of all the details. To this end, it’s essential that you make use of both a reference manager and a literature catalogue . Let’s take a look at each of these.

The reference manager

Reference management software helps you store the reference information for each of your articles and manages the citation and reference list building task as you write up your actual literature review chapter. In other words, a reference manager ensures that your citations and reference list are correctly formatted in the reference style required by your university – e.g., Harvard, APA , MLA, etc.

Using a reference manager saves you the hassle of trying to manually type out your in-text citations and reference list, which you’re bound to mess up in some way. A simple comma out of place, incorrect italicisation or boldfacing can result in you losing marks, and that’s highly likely when you’re dealing with a large number of references. So, it just makes sense to use a piece of software for this task.

The good news is that there are loads of options , many of which are free . For new researchers, we usually recommend Mendeley or Zotero . So, don’t waste your time trying to manage your references manually – get yourself a reference manager ASAP.

The literature catalogue

The second tool you’ll need is a literature catalogue. This is simply an Excel document that you can easily compile yourself (or download our free one here ), where you list and categorise all your literature. You might doubt whether it’s really necessary to have a separate catalogue when you’ve already logged your reference data in a reference manager, but trust us, you’re going to need it. It’s quite common that throughout the literature review process, you’ll review hundreds of articles , so it’s simply impossible that you’ll remember all the details.

What makes a literature catalogue extremely powerful is that you can store as much information as you want for each piece of literature that you include (whereas a reference manager only includes basic fields). Typically, you would include things like:

- Title of the article

- One-line summary of the research

- Key findings and takeaways

- Context (i.e. where did it take place)

- Useful quotes

- Methodology (e.g. qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods)

- Category (you can customise as many categories as makes sense for you)

- Quality of resource

- Type of literature (e.g. primary, secondary or tertiary)

These are just some examples – ultimately you need to customise your catalogue to suit your needs. But, as you can see, the more detailed you get, the more useful your catalogue will become when it’s time to synthesise the research and write up your literature. For example, you could quickly filter the catalogue to display all papers that support a certain hypothesis, that argue in a specific direction, or that were written at a certain time.

5. Read widely (and efficiently)

As we’ve discussed in other posts , the purpose of the literature review chapter is to present and synthesise the current state of knowledge in relation to your research aims, objectives and research questions. To do this, you’ll need to read as broadly and comprehensively as possible. You’ll need to demonstrate to your marker that you “know your stuff” and have a strong understanding of the relevant literature.

Ideally, your literature review should include an eclectic mix of research that features multiple perspectives . In other words, you need to avoid getting tunnel vision and running down one narrow stream of literature. Ideally, you want to highlight both the agreements and disagreements in the literature to show that you’ve got a well-balanced view of the situation.

If your topic is particularly novel and there isn’t a lot of literature available, you can focus your efforts on adjacent literature . For example, if you’re researching factors that cultivate organisational trust in Germany, but there’s very little literature on this, you can draw on US and UK-based studies to form your theoretical foundation. Similarly, if you’re investigating an occurrence in an under-researched industry, you can look at other industries for literature.

As you read each journal article, be sure to scan the reference list for further reading (this technique is called “snowballing”). By doing this, you will quickly identify key literature within a topic area and fast-track your literature review process. You can also check which articles have cited any given article using Google Scholar, which will give you a “forward view” in terms of the progress of the literature.

Given that you’ll need to work through a large amount of literature, it’s useful to adopt a “strategic skimming ” approach when you’re initially assessing articles, so that you don’t need to read the entire journal article . In practical terms, this means you can focus on just the title and abstract at first, and if the article seems relevant based on those, you can jump to the findings section and limitations section . These sections will give you a solid indicator as to whether the resource is relevant to your study, which you can then shortlist for full reading.

6. Keep your golden thread front of mind

Your golden thread (i.e., your research aims, objectives and research questions) needs to guide every decision you make throughout your dissertation, thesis, or research project. This is especially true in the literature review stage, as the golden thread should act as a litmus test for relevance whenever you’re reviewing potential articles or resources. In other words, if an article doesn’t relate to your golden thread, its probably not worth spending time on.

Keep in mind that your research aims, objectives and research questions may evolve as a result of the literature review process. For example, you may find that after reviewing the literature in more depth, your topic focus is not as novel as you originally thought, or that there’s an adjacent area that is more deserving of investigation. This is perfectly natural, so don’t be surprised if your focus shifts somewhat during the review process. Just remember to update your literature review in this case and be sure to update any previous chapters so that your document has a consistent focus throughout.

Wrapping up

In this article, we covered 6 pointers to help you find and evaluate high-quality resources for your literature review. To recap:

- Understand and use different types of literature for the right purpose

If you have any questions, please feel free to leave a comment . Alternatively, if you’d like hands-on help with your literature review, be sure to check out our 1-on-1 private coaching services here.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

this is very helpful to any researcher, I am learning this for the benefit of myself and overs as a library staff

Of course this is useful to most of researchers. I have learnt a lot issues which are relevant to teaching research. Surely they will enjoy my research sessions.

Thank you. Very clear and concise

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Literature Review - what is a Literature Review, why it is important and how it is done

- Strategies to Find Sources

Evaluating Literature Reviews and Sources

Reading critically, tips to evaluate sources.

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

- Useful Resources

A good literature review evaluates a wide variety of sources (academic articles, scholarly books, government/NGO reports). It also evaluates literature reviews that study similar topics. This page offers you a list of resources and tips on how to evaluate the sources that you may use to write your review.

- A Closer Look at Evaluating Literature Reviews Excerpt from the book chapter, “Evaluating Introductions and Literature Reviews” in Fred Pyrczak’s Evaluating Research in Academic Journals: A Practical Guide to Realistic Evaluation , (Chapter 4 and 5). This PDF discusses and offers great advice on how to evaluate "Introductions" and "Literature Reviews" by listing questions and tips. First part focus on Introductions and in page 10 in the PDF, 37 in the text, it focus on "literature reviews".

- Tips for Evaluating Sources (Print vs. Internet Sources) Excellent page that will guide you on what to ask to determine if your source is a reliable one. Check the other topics in the guide: Evaluating Bibliographic Citations and Evaluation During Reading on the left side menu.

To be able to write a good Literature Review, you need to be able to read critically. Below are some tips that will help you evaluate the sources for your paper.

Reading critically (summary from How to Read Academic Texts Critically)

- Who is the author? What is his/her standing in the field.

- What is the author’s purpose? To offer advice, make practical suggestions, solve a specific problem, to critique or clarify?

- Note the experts in the field: are there specific names/labs that are frequently cited?

- Pay attention to methodology: is it sound? what testing procedures, subjects, materials were used?

- Note conflicting theories, methodologies and results. Are there any assumptions being made by most/some researchers?

- Theories: have they evolved overtime?

- Evaluate and synthesize the findings and conclusions. How does this study contribute to your project?

Useful links:

- How to Read a Paper (University of Waterloo, Canada) This is an excellent paper that teach you how to read an academic paper, how to determine if it is something to set aside, or something to read deeply. Good advice to organize your literature for the Literature Review or just reading for classes.

Criteria to evaluate sources:

- Authority : Who is the author? what is his/her credentials--what university he/she is affliliated? Is his/her area of expertise?

- Usefulness : How this source related to your topic? How current or relevant it is to your topic?

- Reliability : Does the information comes from a reliable, trusted source such as an academic journal?

Useful site - Critically Analyzing Information Sources (Cornell University Library)

- << Previous: Strategies to Find Sources

- Next: Tips for Writing Literature Reviews >>

- Last Updated: Jul 3, 2024 10:56 AM

- URL: https://lit.libguides.com/Literature-Review

The Library, Technological University of the Shannon: Midwest

Literature review sources

Sources for literature review can be divided into three categories as illustrated in table below. In your dissertation you will need to use all three categories of literature review sources:

| Primary sources for the literature | High level of detail Little time needed to publish | Reports Theses Emails Conference proceedings Company reports Unpublished manuscript sources Some government publications |

| Secondary sources for the literature | Medium level of detail Medium time needed to publish | Journals Books Newspapers Some government publications Articles by professional associations |

| Tertiary sources for the literature | Low level of detail Considereable amount of time needed to publish | Indexes Databases Catalogues Encyclopaedias Dictionaries Bibliographies Citation indexes Statistical data from government websites |

Sources for literature review and examples

Generally, your literature review should integrate a wide range of sources such as:

- Books . Textbooks remain as the most important source to find models and theories related to the research area. Research the most respected authorities in your selected research area and find the latest editions of books authored by them. For example, in the area of marketing the most notable authors include Philip Kotler, Seth Godin, Malcolm Gladwell, Emanuel Rosen and others.

- Magazines . Industry-specific magazines are usually rich in scholarly articles and they can be effective source to learn about the latest trends and developments in the research area. Reading industry magazines can be the most enjoyable part of the literature review, assuming that your selected research area represents an area of your personal and professional interests, which should be the case anyways.

- Newspapers can be referred to as the main source of up-to-date news about the latest events related to the research area. However, the proportion of the use of newspapers in literature review is recommended to be less compared to alternative sources of secondary data such as books and magazines. This is due to the fact that newspaper articles mainly lack depth of analyses and discussions.

- Online articles . You can find online versions of all of the above sources. However, note that the levels of reliability of online articles can be highly compromised depending on the source due to the high levels of ease with which articles can be published online. Opinions offered in a wide range of online discussion blogs cannot be usually used in literature review. Similarly, dissertation assessors are not keen to appreciate references to a wide range of blogs, unless articles in these blogs are authored by respected authorities in the research area.

Your secondary data sources may comprise certain amount of grey literature as well. The term grey literature refers to type of literature produced by government, academics, business and industry in print and electronic formats, which is not controlled by commercial publishers. It is called ‘grey’ because the status of the information in grey literature is not certain. In other words, any publication that has not been peer reviewed for publication is grey literature.

The necessity to use grey literature arises when there is no enough peer reviewed publications are available for the subject of your study.

John Dudovskiy

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 5. The Literature Review

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A literature review surveys prior research published in books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated. Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have used in researching a particular topic and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within existing scholarship about the topic.

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . Fourth edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2014.

Importance of a Good Literature Review

A literature review may consist of simply a summary of key sources, but in the social sciences, a literature review usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

Given this, the purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2011; Knopf, Jeffrey W. "Doing a Literature Review." PS: Political Science and Politics 39 (January 2006): 127-132; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012.

Types of Literature Reviews

It is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the primary studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally among scholars that become part of the body of epistemological traditions within the field.

In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews. Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are a number of approaches you could adopt depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study.

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply embedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews [see below].

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses or research problems. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication. This is the most common form of review in the social sciences.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [findings], but how they came about saying what they say [method of analysis]. Reviewing methods of analysis provides a framework of understanding at different levels [i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches, and data collection and analysis techniques], how researchers draw upon a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection, and data analysis. This approach helps highlight ethical issues which you should be aware of and consider as you go through your own study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyze data from the studies that are included in the review. The goal is to deliberately document, critically evaluate, and summarize scientifically all of the research about a clearly defined research problem . Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?" This type of literature review is primarily applied to examining prior research studies in clinical medicine and allied health fields, but it is increasingly being used in the social sciences.

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

NOTE: Most often the literature review will incorporate some combination of types. For example, a review that examines literature supporting or refuting an argument, assumption, or philosophical problem related to the research problem will also need to include writing supported by sources that establish the history of these arguments in the literature.

Baumeister, Roy F. and Mark R. Leary. "Writing Narrative Literature Reviews." Review of General Psychology 1 (September 1997): 311-320; Mark R. Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147; Petticrew, Mark and Helen Roberts. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide . Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2006; Torracro, Richard. "Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples." Human Resource Development Review 4 (September 2005): 356-367; Rocco, Tonette S. and Maria S. Plakhotnik. "Literature Reviews, Conceptual Frameworks, and Theoretical Frameworks: Terms, Functions, and Distinctions." Human Ressource Development Review 8 (March 2008): 120-130; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Thinking About Your Literature Review

The structure of a literature review should include the following in support of understanding the research problem :

- An overview of the subject, issue, or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review,

- Division of works under review into themes or categories [e.g. works that support a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative approaches entirely],

- An explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others,

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research.

The critical evaluation of each work should consider :

- Provenance -- what are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence [e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings]?

- Methodology -- were the techniques used to identify, gather, and analyze the data appropriate to addressing the research problem? Was the sample size appropriate? Were the results effectively interpreted and reported?

- Objectivity -- is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness -- which of the author's theses are most convincing or least convincing?

- Validity -- are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

II. Development of the Literature Review

Four Basic Stages of Writing 1. Problem formulation -- which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues? 2. Literature search -- finding materials relevant to the subject being explored. 3. Data evaluation -- determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic. 4. Analysis and interpretation -- discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature.

Consider the following issues before writing the literature review: Clarify If your assignment is not specific about what form your literature review should take, seek clarification from your professor by asking these questions: 1. Roughly how many sources would be appropriate to include? 2. What types of sources should I review (books, journal articles, websites; scholarly versus popular sources)? 3. Should I summarize, synthesize, or critique sources by discussing a common theme or issue? 4. Should I evaluate the sources in any way beyond evaluating how they relate to understanding the research problem? 5. Should I provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history? Find Models Use the exercise of reviewing the literature to examine how authors in your discipline or area of interest have composed their literature review sections. Read them to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research or to identify ways to organize your final review. The bibliography or reference section of sources you've already read, such as required readings in the course syllabus, are also excellent entry points into your own research. Narrow the Topic The narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to obtain a good survey of relevant resources. Your professor will probably not expect you to read everything that's available about the topic, but you'll make the act of reviewing easier if you first limit scope of the research problem. A good strategy is to begin by searching the USC Libraries Catalog for recent books about the topic and review the table of contents for chapters that focuses on specific issues. You can also review the indexes of books to find references to specific issues that can serve as the focus of your research. For example, a book surveying the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict may include a chapter on the role Egypt has played in mediating the conflict, or look in the index for the pages where Egypt is mentioned in the text. Consider Whether Your Sources are Current Some disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. This is particularly true in disciplines in medicine and the sciences where research conducted becomes obsolete very quickly as new discoveries are made. However, when writing a review in the social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be required. In other words, a complete understanding the research problem requires you to deliberately examine how knowledge and perspectives have changed over time. Sort through other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. You can also use this method to explore what is considered by scholars to be a "hot topic" and what is not.

III. Ways to Organize Your Literature Review

Chronology of Events If your review follows the chronological method, you could write about the materials according to when they were published. This approach should only be followed if a clear path of research building on previous research can be identified and that these trends follow a clear chronological order of development. For example, a literature review that focuses on continuing research about the emergence of German economic power after the fall of the Soviet Union. By Publication Order your sources by publication chronology, then, only if the order demonstrates a more important trend. For instance, you could order a review of literature on environmental studies of brown fields if the progression revealed, for example, a change in the soil collection practices of the researchers who wrote and/or conducted the studies. Thematic [“conceptual categories”] A thematic literature review is the most common approach to summarizing prior research in the social and behavioral sciences. Thematic reviews are organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time, although the progression of time may still be incorporated into a thematic review. For example, a review of the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics could focus on the development of online political satire. While the study focuses on one topic, the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics, it would still be organized chronologically reflecting technological developments in media. The difference in this example between a "chronological" and a "thematic" approach is what is emphasized the most: themes related to the role of the Internet in presidential politics. Note that more authentic thematic reviews tend to break away from chronological order. A review organized in this manner would shift between time periods within each section according to the point being made. Methodological A methodological approach focuses on the methods utilized by the researcher. For the Internet in American presidential politics project, one methodological approach would be to look at cultural differences between the portrayal of American presidents on American, British, and French websites. Or the review might focus on the fundraising impact of the Internet on a particular political party. A methodological scope will influence either the types of documents in the review or the way in which these documents are discussed.

Other Sections of Your Literature Review Once you've decided on the organizational method for your literature review, the sections you need to include in the paper should be easy to figure out because they arise from your organizational strategy. In other words, a chronological review would have subsections for each vital time period; a thematic review would have subtopics based upon factors that relate to the theme or issue. However, sometimes you may need to add additional sections that are necessary for your study, but do not fit in the organizational strategy of the body. What other sections you include in the body is up to you. However, only include what is necessary for the reader to locate your study within the larger scholarship about the research problem.

Here are examples of other sections, usually in the form of a single paragraph, you may need to include depending on the type of review you write:

- Current Situation : Information necessary to understand the current topic or focus of the literature review.

- Sources Used : Describes the methods and resources [e.g., databases] you used to identify the literature you reviewed.

- History : The chronological progression of the field, the research literature, or an idea that is necessary to understand the literature review, if the body of the literature review is not already a chronology.

- Selection Methods : Criteria you used to select (and perhaps exclude) sources in your literature review. For instance, you might explain that your review includes only peer-reviewed [i.e., scholarly] sources.

- Standards : Description of the way in which you present your information.

- Questions for Further Research : What questions about the field has the review sparked? How will you further your research as a result of the review?

IV. Writing Your Literature Review

Once you've settled on how to organize your literature review, you're ready to write each section. When writing your review, keep in mind these issues.

Use Evidence A literature review section is, in this sense, just like any other academic research paper. Your interpretation of the available sources must be backed up with evidence [citations] that demonstrates that what you are saying is valid. Be Selective Select only the most important points in each source to highlight in the review. The type of information you choose to mention should relate directly to the research problem, whether it is thematic, methodological, or chronological. Related items that provide additional information, but that are not key to understanding the research problem, can be included in a list of further readings . Use Quotes Sparingly Some short quotes are appropriate if you want to emphasize a point, or if what an author stated cannot be easily paraphrased. Sometimes you may need to quote certain terminology that was coined by the author, is not common knowledge, or taken directly from the study. Do not use extensive quotes as a substitute for using your own words in reviewing the literature. Summarize and Synthesize Remember to summarize and synthesize your sources within each thematic paragraph as well as throughout the review. Recapitulate important features of a research study, but then synthesize it by rephrasing the study's significance and relating it to your own work and the work of others. Keep Your Own Voice While the literature review presents others' ideas, your voice [the writer's] should remain front and center. For example, weave references to other sources into what you are writing but maintain your own voice by starting and ending the paragraph with your own ideas and wording. Use Caution When Paraphrasing When paraphrasing a source that is not your own, be sure to represent the author's information or opinions accurately and in your own words. Even when paraphrasing an author’s work, you still must provide a citation to that work.

V. Common Mistakes to Avoid

These are the most common mistakes made in reviewing social science research literature.

- Sources in your literature review do not clearly relate to the research problem;

- You do not take sufficient time to define and identify the most relevant sources to use in the literature review related to the research problem;

- Relies exclusively on secondary analytical sources rather than including relevant primary research studies or data;

- Uncritically accepts another researcher's findings and interpretations as valid, rather than examining critically all aspects of the research design and analysis;

- Does not describe the search procedures that were used in identifying the literature to review;

- Reports isolated statistical results rather than synthesizing them in chi-squared or meta-analytic methods; and,

- Only includes research that validates assumptions and does not consider contrary findings and alternative interpretations found in the literature.

Cook, Kathleen E. and Elise Murowchick. “Do Literature Review Skills Transfer from One Course to Another?” Psychology Learning and Teaching 13 (March 2014): 3-11; Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . London: SAGE, 2011; Literature Review Handout. Online Writing Center. Liberty University; Literature Reviews. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2016; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012; Randolph, Justus J. “A Guide to Writing the Dissertation Literature Review." Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation. vol. 14, June 2009; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016; Taylor, Dena. The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Writing a Literature Review. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra.

Writing Tip

Break Out of Your Disciplinary Box!

Thinking interdisciplinarily about a research problem can be a rewarding exercise in applying new ideas, theories, or concepts to an old problem. For example, what might cultural anthropologists say about the continuing conflict in the Middle East? In what ways might geographers view the need for better distribution of social service agencies in large cities than how social workers might study the issue? You don’t want to substitute a thorough review of core research literature in your discipline for studies conducted in other fields of study. However, particularly in the social sciences, thinking about research problems from multiple vectors is a key strategy for finding new solutions to a problem or gaining a new perspective. Consult with a librarian about identifying research databases in other disciplines; almost every field of study has at least one comprehensive database devoted to indexing its research literature.

Frodeman, Robert. The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity . New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Just Review for Content!

While conducting a review of the literature, maximize the time you devote to writing this part of your paper by thinking broadly about what you should be looking for and evaluating. Review not just what scholars are saying, but how are they saying it. Some questions to ask:

- How are they organizing their ideas?

- What methods have they used to study the problem?

- What theories have been used to explain, predict, or understand their research problem?

- What sources have they cited to support their conclusions?

- How have they used non-textual elements [e.g., charts, graphs, figures, etc.] to illustrate key points?

When you begin to write your literature review section, you'll be glad you dug deeper into how the research was designed and constructed because it establishes a means for developing more substantial analysis and interpretation of the research problem.

Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1 998.

Yet Another Writing Tip

When Do I Know I Can Stop Looking and Move On?

Here are several strategies you can utilize to assess whether you've thoroughly reviewed the literature:

- Look for repeating patterns in the research findings . If the same thing is being said, just by different people, then this likely demonstrates that the research problem has hit a conceptual dead end. At this point consider: Does your study extend current research? Does it forge a new path? Or, does is merely add more of the same thing being said?

- Look at sources the authors cite to in their work . If you begin to see the same researchers cited again and again, then this is often an indication that no new ideas have been generated to address the research problem.

- Search Google Scholar to identify who has subsequently cited leading scholars already identified in your literature review [see next sub-tab]. This is called citation tracking and there are a number of sources that can help you identify who has cited whom, particularly scholars from outside of your discipline. Here again, if the same authors are being cited again and again, this may indicate no new literature has been written on the topic.

Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2016; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

- << Previous: Theoretical Framework

- Next: Citation Tracking >>

- Last Updated: Jul 3, 2024 10:07 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Getting Started

- Introduction

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

Reading Critically

To be able to write a good literature review, you need to be able to read critically. Below are some tips that will help you evaluate the sources for your paper.

Reading critically (summary from How to Read Academic Texts Critically)

- Who is the author? What is his/her standing in the field?

- What is the author’s purpose? To offer advice, make practical suggestions, solve a specific problem, to critique, or clarify?

- Note the experts in the field. Are there specific names/labs that are frequently cited?

- Pay attention to methodology. Is it sound? What testing procedures, subjects, and materials were used?

- Note conflicting theories, methodologies and results. Are there any assumptions being made by most/some researchers?

- Theories: Have they evolved overtime?

- Evaluate and synthesize the findings and conclusions. How does this study contribute to your project?

Useful links:

Tips to Evaluate Sources

Criteria to evaluate sources:

Authority : Who is the author? what is his/her credentials--what university he/she is affliliated? Is his/her area of expertise?

Usefulness : How this source related to your topic? How current or relevant it is to your topic?

Reliability : Does the information comes from a reliable, trusted source such as an academic journal?

Useful sites

- Critically Analyzing Information Sources (Cornell University Library)

Evaluating Literature Reviews and Sources

A good literature review evaluates a wide variety of sources (academic articles, scholarly books, government/NGO reports). It also evaluates literature reviews that study similar topics. This page offers you a list of resources and tips on how to evaluate the sources that you may use to write your review.

- A Closer Look at Evaluating Literature Reviews Excerpt from the book chapter, “Evaluating Introductions and Literature Reviews” in Fred Pyrczak’s Evaluating Research in Academic Journals: A Practical Guide to Realistic Evaluation , (Chapter 4 and 5). This PDF discusses and offers great advice on how to evaluate "Introductions" and "Literature Reviews" by listing questions and tips.

- Tips for Evaluating Sources (Print vs. Internet Sources) Excellent page that will guide you on what to ask to determine if your source is a reliable one. Check the other topics in the guide: Evaluating Bibliographic Citations and Evaluation During Reading on the left side menu.

- << Previous: Strategies to Find Sources

- Next: Tips for Writing Literature Reviews >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

Conducting a Literature Review

- Getting Started

- Define your Research Question

- Finding Sources

- Evaluating Sources

- Organizing the Review

- Cite and Manage your Sources

Introduction

The process of evaluating sources can take place when you first encounter a source, when you're reading it over, and as you incorporate it into your project. In general, some level of evaluation should take place at all of these stages, with different goals for each. The last evaluation will be discussed in "Organizing the Review," but we'll go over the first two here.

The overall purpose of evaluating sources is to make sure that your review has the most relevant, accurate, and unbiased literature in the field, so that you can determine what has already been learned about your topic and where further research may be needed.

Additional Resources

- Evaluate Sources by Kansas State University Libraries

- How to Evaluate Any Source by Skyline College Library

Evaluating Sources During the Initial Search Process

When you first encounter a potential source, you'll want to know very quickly whether it is worth reading in detail and considering for your literature review. To avoid wasting time on unhelpful sources as much as possible, it's generally best to run each article, book, or other resource you find through a quick checklist, using information you can find by skimming through the summary and introduction.

The two most common forms of early source evaluation are the "Big 5 Criteria" and the "CRAAP Test." These cover the same most significant variables for evaluation, and which one to use comes down to preference.

Big 5 Criteria:

The most important criteria for evaluating a potential resource are:

- Currency : When the source was published

- Coverage/Relevance : How closely related the source is to your topic and research question

- Authority : Who wrote the source and whether they are likely to be credible on the subject

- Accuracy : Whether the information is accurate or not (this will be more heavily evaluated further on in the research process, but you should skim through quickly for any obviously inaccurate information as a means of disqualifying the source)

- Objectivity/Purpose : Whether or not the source presents a biased point of view or agenda

A good rule of thumb for Currency is that medical, scientific, and technology resources should be published within the last 5 years to prevent the information from being out-of-date; for less time-sensitive topics like history or the humanities, resources published within the last 5-10 years are often acceptable.

CRAAP Test:

A helpful mnemonic to remember the evaluation criteria, CRAAP is an acronym for:

Helpful questions for initial evaluation:

- When was this source published?

- Is this source relevant to your topic?

- What are the author or authors' qualifications?

- Is the resource scholarly/peer-reviewed?

- Are sources cited to support the author's claims?

- Does the website or journal the source comes from have a bias to their reporting?

- Do you notice biased or emotional language in the summary or introduction?

- Do you notice spelling or grammatical errors in a quick examination of the source?

- Writing a Research Paper: Evaluate Sources by Kansas State University

Evaluating Sources During the Reading Process

Once a resource has passed the initial evaluation, you are ready to begin reading through it to more carefully determine if it belongs in your project. In addition to the questions posed above, which are always relevant to evaluating sources, you should look at your potential sources of literature with an eye to the following questions:

1. Is there any bias visible in the work?

You already began this process in the previous step and hopefully eliminated the most obviously unreliable sources, but as you read it is always important to keep an eye out for potential blind spots the author might have based on their own perspective. Bias is not inherently disqualifying -- a biased article may still have accurate information -- but it is essential to know if a bias exists and be aware of how it might impact how the information was gathered, evaluated, or delivered.

Peer-reviewed sources tend to be less likely to have this risk, because multiple editors had to go through the resource looking for mistakes or biases. They need to meet a much higher academic threshold.

2. How was the research conducted? Are there any strengths or weaknesses in its methodology?

It is important to understand how the study in your source was administered; a significant part of the literature review will be about potential gaps in the current research, so you need to understand how the existing research was done.

3. How does the author justify their conclusions?

Either through the results of their own research or by citing external evidence, an article, book, or other type of resource should provide proof of its claims. In the initial research process you checked to make sure that there was evidence supporting the author's assertions; now it is time to take a look at that evidence and see if you find it compelling, or if you think it doesn't justify the conclusions drawn by the article.

4. What similarities do these articles share?

Grouping your literature review by categories based on subtopic, findings, or chronology can be an extremely helpful way to organize your work. Take notes while you're reading of common themes and results to make planning the review easier.

5. Where does this research differ from the other sources?

While very close to the previous question, this one emphasizes what unique information, methodology, or insights a particular source brings to the overall understanding of the topic. What new knowledge is being brought to the table by this source that would justify it appearing in your literature review?

6. Does this source leave any unanswered questions or opportunities for further research?

Most scholarly journal articles will include a section near the end of the article addressing limits of their study and opportunities for further research. Examine these closely and see where other sources you have fill in the gaps, and where perhaps additional research needs to be done to gain a more complete understanding of your topic.

As you go through this process, you might find yourself eliminating certain sources that no longer seem like they fit with your project's goals, or getting inspired to search for additional sources based on new information you've found. This is a normal part of the research process, and additional searching may be necessary to fill in any gaps left after evaluating the sources you already have.

- << Previous: Finding Sources

- Next: Organizing the Review >>

- Last Updated: Apr 12, 2024 10:37 AM

- URL: https://libraryservices.acphs.edu/lit_review

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Working with sources

- Evaluating Sources | Methods & Examples

Evaluating Sources | Methods & Examples

Published on June 2, 2022 by Eoghan Ryan . Revised on May 31, 2023.