- Study Notes

- College Essays

AP U.S. History Notes

- Chapter Outlines

- Practice Tests

- Topic Outlines

- Court Cases

- Sample Essays

- The Progressive Presidents

Roosevelt’s Square Deal

At the dawn of the twentieth century, America was at a crossroads. Presented with abundant opportunity, but also hindered by significant internal and external problems, the country was seeking leaders who could provide a new direction. The political climate was ripe for reform, and the stage was set for the era of the Progressive Presidents, beginning with Republican Theodore Roosevelt.

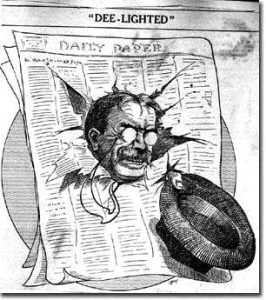

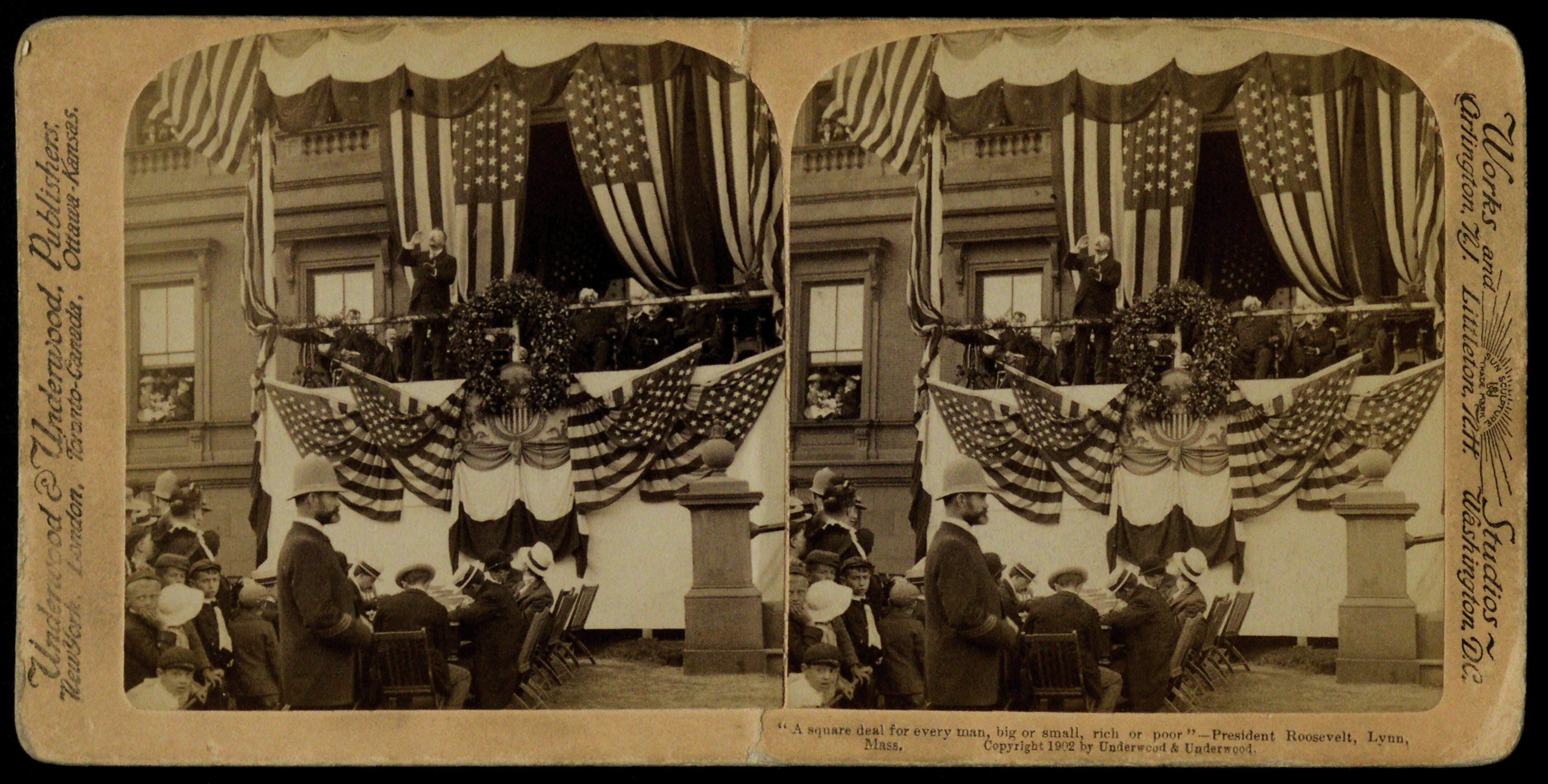

Teddy Roosevelt was widely popular due to his status as a hero of the Spanish-American War and his belief in “speaking softly and carrying a big stick.” Taking over the presidency in 1901 after the assassination of William McKinley, he quickly assured America that he would not take any drastic measures. He then demanded a “Square Deal” that would address his primary concerns for the era—the three C’s: control of corporations, consumer protection, and conservation.

The ownership of corporations and the relationship between owners and laborers, as well as government’s role in the relationship, were the contentious topics of the period. Workers were demanding greater rights and protection, while corporations expected labor to remain cheap and plentiful. This conflict came to a head in 1902, with the anthracite coal strike in Pennsylvania. Coal mining was dirty and dangerous work, and 140,000 miners went on strike and demanded a 20 percent pay increase and a reduction in the workday from ten to nine hours. The mine owners were unsympathetic and refused to negotiate with labor representatives. With the approach of winter the dwindling coal supply began to cause concern throughout the nation.

Roosevelt, going against established precedent, decided to step in. He summoned the mine owners and union representatives to meet with him in Washington. Roosevelt was partly moved by strong public support and took the side of the miners. Still, the mine owners were reluctant to negotiate until Roosevelt, threatening to use his “big stick,” declared that he would seize the mines and operate them with federal troops. Owners reluctantly agreed to arbitration, where the striking workers received a 10 percent pay increase and a nine-hour working day. This was the first time a president sided with unions in a labor dispute, and it helped cement Roosevelt’s reputation as a friend of the common people and gave his administration the nickname “The Square Deal.”

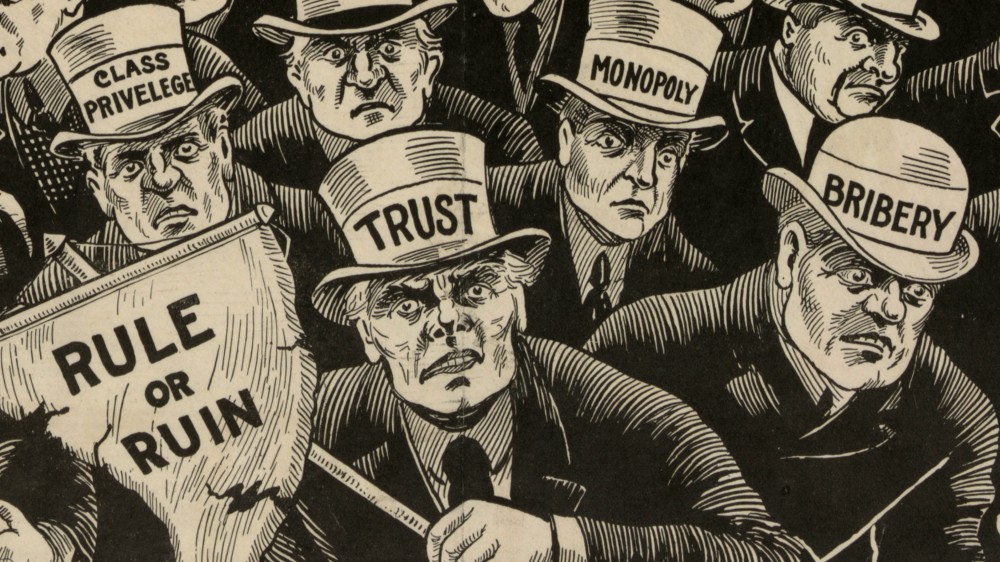

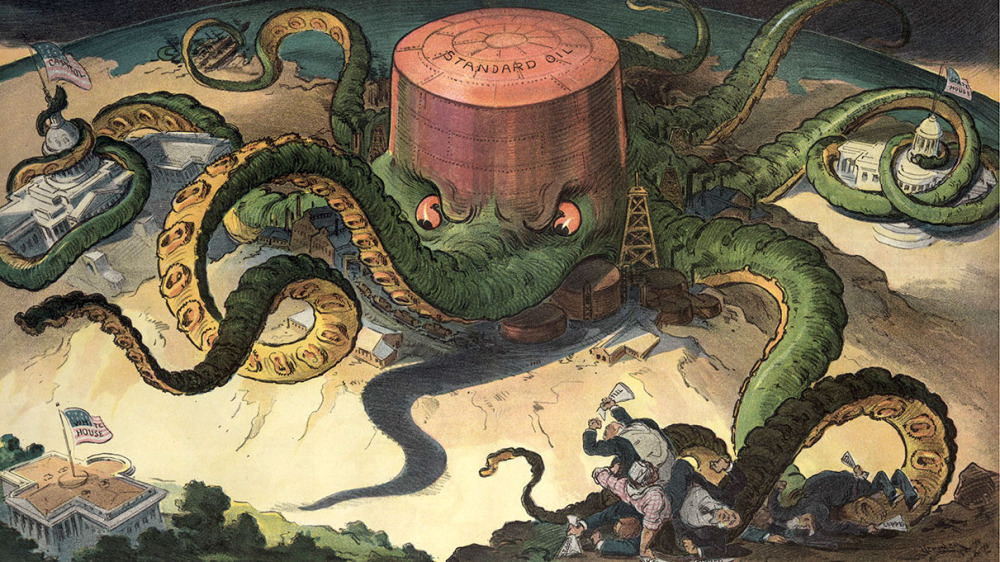

Emboldened by this success and in pursuit of the first element of his Square Deal, Roosevelt began to attack large, monopolistic corporations. Some trusts were effective and legitimate, but many of these companies engaged in corrupt and preferential business practices. In 1902, the Northern Securities Company, owned by J.P. Morgan and James J. Hill, controlled most of the railroads in the northwestern United States and intended to create a total monopoly. Roosevelt initiated legal proceedings against Northern Securities and eventually the Supreme Court ordered that the company be dissolved. Roosevelt’s radical actions angered big business and earned him the reputation of a “trust buster,” despite the fact that his successors Taft and Wilson actually dissolved more trusts.

In 1903, with urging from Roosevelt, Congress created the Department of Commerce and Labor (DOCL). This cabinet-level department was designed to monitor corporations and ensure that they engaged in fair business practices. The Bureau of Corporations was created under the DOCL to benefit consumers by monitoring interstate commerce, helping dissolve monopolies, and promoting fair competition between companies. In 1913, the DOCL was split into two separate entities, the Department of Commerce and the Department of Labor, both of which continue to play an important role in regulating business today.

The railroad business continued to be one of the most powerful and influential industries. Like many companies of the time, railroad companies engaged in corrupt business practices such as rebating and price fixing. Roosevelt encouraged Congress to take action to address these abuses, and in 1903 they passed the Elkins Act, which levied heavy fines on companies that engaged in illegal rebating. In 1906, they passed the Hepburn Act, which greatly strengthened the Interstate Commerce Commission. This law allowed the Commission to set maximum rates, inspect a company’s books, and investigate railroads, sleeping car companies, oil pipelines, and other transportation firms. This was a bold action by Roosevelt and Congress given the transportation industry was a powerful lobbyist and a significant political contributor.

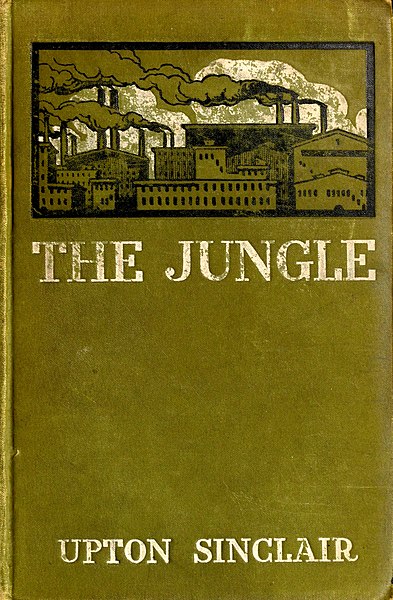

The second element of Roosevelt’s Square Deal was consumer protection. In the early 1900s, there was little regulation of the food or drugs that were available to the public. In 1906, Upton Sinclair published a book called The Jungle that described in graphic detail the Chicago slaughterhouse industry. Sinclair intended for his book to expose the plight of immigrant workers and possibly bring readers to the Socialist movement, but people were instead shocked and sickened by the practices of the meat industry.

Roosevelt had the power to do something about the horrors described in The Jungle . He immediately appointed a special investigating committee to look into food handling practices in Chicago. Their report confirmed much of what Sinclair had written. Roosevelt was shocked by the report and predicted that it could have a devastating effect on American meat exports. He agreed to keep it quiet on the condition that Congress would take action to address the issues.

After much pressure from Roosevelt, Congress reluctantly agreed to pass the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. Many members of Congress were reluctant to pass these laws, as the meat industry was a powerful lobbying force. However, the passage of this legislation helped prevent the adulteration and mislabeling of food, alcohol, and drugs. It was an important first step toward ensuring that Americans were buying safe and healthy products. Eventually, the meatpacking industry welcomed these reforms, as they found that a government seal of approval would help increase their export revenues.

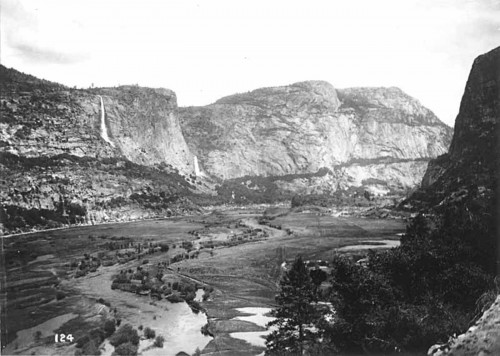

The final element of Roosevelt’s Square Deal was conservation. Roosevelt was widely known as a sportsman, hunter, and outdoorsman, and he had a genuine love and respect for nature. However, many Americans of the time viewed the country’s natural resources as limitless. For example, many farmers, ranchers, and timber companies in the west were consuming a huge portion of the available resources at an alarming rate. Their primary obsession was profit, and they had little concern for the damage they were causing. However, there was a small but vocal population who had a great deal of concern for the environment. Fortunately for them and for future Americans, the environmentalists had a friend in Teddy Roosevelt.

Environmentalism and conservation were not new ideas, but most had not been concerned with ecological issues. While a number of laws had been passed to prevent or limit the destruction of natural resources, the majority of this legislation was not enforced or lacked the teeth necessary to make a significant difference.

With Roosevelt’s urging, Congress passed the Newlands Act of 1902. This legislation allowed the federal government to sell public lands in the arid, desert western states and devote the proceeds to irrigation projects. Landowners would then repay part of the irrigation costs from the proceeds they received from their newly fertile land, and this money was earmarked for more irrigation projects. Eventually, dozens of dams were created in the desert including the massive Roosevelt Dam on Arizona’s Salt River.

Another major concern of environmentalists was the devastation of the nation’s timberlands. By 1900, only about 25 percent of the huge timber preserves were still standing. Roosevelt set aside 125 million acres of timberlands as federal reserves, over three times the amount preserved by all of his predecessors combined. He also performed similar actions with coal and water reserves, thus guaranteeing the preservation of some natural resources for future generations. Environmentalists such as John Muir, Gifford Pinchot, and the upstart Sierra Club aided Roosevelt in his efforts. Preserving America’s natural resources and calling attention to the desperate need for conservation may well have been Teddy Roosevelt’s greatest achievement as President, and his most enduring legacy.

Taft’s Administration

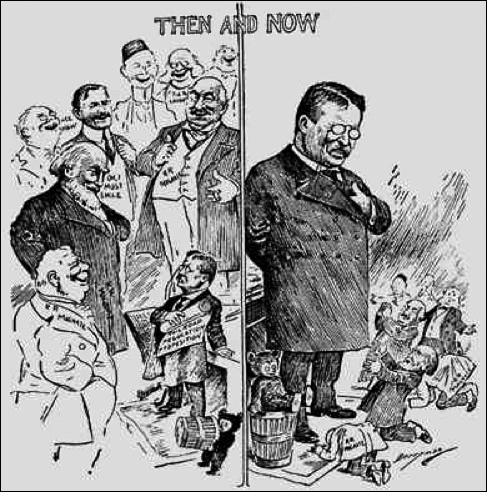

In 1908, President Teddy Roosevelt could have easily carried his burgeoning popularity to a sweeping victory in the presidential election, but in 1904 he made an impulsive promise not to seek a second elected term. However, he did not intend to completely relinquish control, so he handpicked a successor. Howard Taft, the 350-pound Secretary of War, was chosen as the Republican candidate for 1908. Taft was a mild progressive and an easygoing man that Roosevelt and other Republican leaders felt they could control. Taft easily defeated the Democratic candidate, William Jennings Bryan, and the Socialist candidate, Eugene Debs, in what can be construed as continued public endorsement of Roosevelt.

Unfortunately, from the onset of his administration Taft did not live up to Roosevelt’s standards or the expectations of other Progressives. He lacked Roosevelt’s strength of personality and was more passive in his dealings with Congress. Many politicians were surprised to learn that Taft did not share some of the Progressive ideas and policies that Roosevelt endorsed. In fact, many people felt that Taft lacked the mental and physical stamina necessary to be an effective President.

The first major blow to the Progressives during Taft’s administration was the Payne-Aldrich Tariff of 1909. Taft called a special session of Congress to address what many people felt were excessive tariffs. After this session, the House of Representatives passed a bill that moderately restricted tariffs, but their legislation was severely modified when it reached the Senate. Radical Senators, led by Nelson W. Aldrich of Rhode Island, tacked on hundreds of revisions that effectively raised tariffs on almost all products. Taft eventually signed the bill and declared it “the best bill that the Republican Party ever passed.” This action dumbfounded Progressives and marked the beginning of an internal struggle for control of the Republican Party.

Another issue that caused dissension among Republicans was Taft’s handling of conservation issues. Taft was a dedicated conservationist and he devoted extensive resources to the protection of the environment. However, most of his progress was undone by his handling of the Ballinger-Pinchot dispute. Pinchot, the leader of the Department of Forestry and a well-liked ally of Roosevelt, attacked Secretary of the Interior Richard Ballinger for how he handled public lands.

Ballinger opened up thousands of acres of public lands in Wyoming, Montana, and Alaska for private use, and this angered many Progressives. Pinchot was openly critical of Ballinger, and in 1910 Taft responded by firing Pinchot for insubordination. This infuriated much of the public as well as the legions of political players who were still fiercely loyal to Roosevelt.

A major rift occurred in the Republican Party as a result of Taft’s straying from Progressive policy. The party was split down the middle between the “Old Guard” Republicans who supported Taft and the Progressive Republicans who backed Roosevelt. This division in the Republican Party allowed Democrats to regain control of the House of Representatives in a landslide victory in the congressional elections of 1910.

In early 1912, Roosevelt triumphantly returned and announced himself as a challenger for the Republican presidential nomination. Roosevelt and his followers, embracing “New Nationalism,” began to furiously campaign for the nomination. However, as a result of their late start and Taft’s ability as incumbent to control the convention, they were unable to secure the delegates necessary to win the Republican candidacy. Not one to admit defeat, Roosevelt formed the “Bull Moose” Party and vowed to enter the race as a third-party candidate.

The split in the Republican Party made the Democrats optimistic about regaining the White House for the first time since 1897. They sought a reformist candidate to challenge the Republicans, and decided on Woodrow Wilson, a career academic and the current progressive governor of New Jersey. Wilson’s “New Freedom” platform sought reduced tariffs, banking reform, and stronger antitrust legislation. The Socialists again nominated Eugene V. Debs whose platform sought public ownership of resources and industries. As expected, Roosevelt and Taft split the Republican vote, and Wilson easily won a majority of the electoral votes. Having received only 41 percent of the popular vote, Wilson was a minority president.

Wilson’s New Freedom

Upon taking office, Woodrow Wilson became only the second Democratic president since 1861. Wilson was a trim figure with clean-cut features and pince-nez glasses clipped to the bridge of his nose, giving him an academic look. Partly due to his academic background and limited political experience, Wilson was very much an idealist. He was intelligent and calculating, but the public perception was that he was emotionally cold and distant. Wilson arrived in the White House with a clear agenda and the drive to achieve all of his goals. In addition, the Democratic majority in both houses of Congress was eager to show the public that their support was not misdirected.

Wilson’s platform called for an assault on “the triple wall of privilege,” which consisted of tariffs, banks, and trusts, and rarely has a president set to work so quickly. His first objective was to reduce the prohibitive tariffs that hurt American businesses and consumers. In an unprecedented move, Wilson personally appeared before Congress to call a special session to discuss tariffs in early 1913. Moved and stunned by Wilson’s eloquence and force of character, Congress immediately designed the Underwood Tariff Bill, which significantly reduced import fees.

The Underwood Tariff Bill brought the first significant reduction of duties since before the Civil War. In order to make up for the loss in revenues caused by the lower tariffs, the Underwood Bill introduced a graduated income tax. This new tax was introduced under the authority of the recently ratified Sixteenth Amendment. Initially, the tax was levied on incomes over $3,000, which was significantly higher than the national average. However, by 1917 the revenue from income taxes greatly exceeded receipts from the tariff. This margin has continued to grow exponentially over the years.

After tackling the tariff, Wilson turned his attention to the nation’s banks. The country’s financial structure was woefully outdated, and its inefficiencies had been exposed by the Republican’s economic expansion and the Panic of 1907. The currency system was very inelastic, with most reserves concentrated in New York and a few other large cities. These resources could not be mobilized quickly in the event of a financial crisis in a different area. Wilson considered two proposals: one calling for a third Bank of the United States, the other seeking a decentralized bank under government control.

Siding with public opinion, Wilson called another special session of Congress in June of 1913. He overwhelmingly endorsed the idea of a decentralized bank, and asked Congress to radically change the banking system. Congress passed the Federal Reserve Act, which was arguably the greatest piece of legislation between the Civil War and Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. The Act created a Federal Reserve Board, which oversaw a system of 12 regional reserve districts, each with its own central bank. This new system also issued Federal Reserve Notes, paper currency that quickly allowed the government to adjust the flow of money, which are still in use today. The Federal Reserve Act was instrumental in allowing America to meet the financial challenges of World War I and emerge from the war as one of the world’s financial powers.

Emboldened by his successes, President Wilson turned his attention to the trusts. Although legislation designed to address the issue of trusts had existed for many years, they were still very much a problem. Again, Wilson appeared before Congress and delivered an emotional and dramatic address. He asked Congress to create legislation that would finally address trusts and tame the rampant monopolies. After several months of discussion, Congress presented Wilson with the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914. This act allowed the government to closely inspect companies engaged in interstate commerce, such as meatpackers and railroads. The Commission investigated unfair trading practices such as false advertising, monopolistic practices, bribery, and misrepresentation.

Following closely behind the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914, was the Clayton Act of 1914. It served to strengthen the Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890 (the first measure passed by the U.S. Congress to prohibit trusts) and redefine the practices that were considered monopolistic and illegal. The Clayton Act provided support for labor unions by exempting labor from antitrust prosecution and legalizing strikes and peaceful picketing, which were not part of the Sherman Act. Renowned American Federation of Labor union leader, Samuel Gompers, declared the Clayton Act the “Magna Carta” of labor. Unfortunately, labor’s triumph was short-lived, as conservative judges continued to curtail union power in controversial decisions.

The era of the Progressive presidents produced a number of notable achievements. Trust-busting forced industrialists and monopolistic corporations to consider public opinion when making business decisions. This benefited the consumer and helped grow the economy. The Progressive presidents also increased consumers’ rights by limiting corporate abuses and trying to ensure the safe labeling of food and drugs. The creation of a federal income tax system lowered tariffs and increased America’s presence as a global trading partner. It also raised additional revenues, some of which were used for beneficial programs such as conservation. The Progressive presidents served to strengthen the office of the president and the public began to expect more from the executive branch. Progressivism as a concept helped challenge traditional thinking about government’s relationship to the people and sparked new ideas that stimulated thought for decades to come.

Along with these significant accomplishments, the Progressive movement also had a number of notable shortcomings. Due to several contrary schools of thought within the movement, goals were often confusing and contradictory. Although most Progressives had good intentions, their conflicting goals helped detract from the overall objectives of the movement. Despite the numerous successes and lofty goals and ideals of the Progressive movement, the federal government was still too greatly influenced by industry and big business.

You just finished The Progressive Presidents . Nice work!

Previous Outline Next Outline

Tip: Use ← → keys to navigate!

How to cite this note (MLA)

More apush topic outlines.

- Discovery and Settlement of the New World

- Europe and the Impulse for Exploration

- Spanish and French Exploration

- The First English Settlements

- The New England Colonies

- The Middle, Chesapeake, and Southern Colonies

- Colonial Life

- Scientific and Religious Transformation

- French and Indian War

- Imperial Reorganization

- Philosophy of American Revolution

- Declaration of Independence

- The Revolutionary War

- Articles of Confederation

- The Confederation Faces Challenges

- Philadelphia Convention

- Federalists versus Antifederalists

- Development of the Two-party System

- Jefferson as President

- War of 1812

- James Monroe

- A Growing National Economy

- The Transportation Revolution

- King Cotton

- Democracy and the “Common Man”

- Nullification Crisis

- The Bank of the United States

- Indian Removal

- Transcendentalism, Religion, and Utopian Movements

- Reform Crusades

- Manifest Destiny

- Decade of Crisis

- The Approaching War

- The Civil War

- Abolition of Slavery

- Ramifications of the Civil War

- Presidential and Congressional Reconstruction Plans

- The End of Reconstruction

- The New South

- Focus on the West

- Confrontations with Native Americans

- Cattle, Frontiers, and Farming

- End of the Frontier

- Gilded Age Scandal and Corruption

- Consumer Culture

- Rise of Unions

- Growth of Cities

- Life in the City

- Agrarian Revolt

- The Progressive Impulse

- McKinley and Roosevelt

- Taft and Wilson

- U.S. Entry into WWI

- Peace Conferences

- Social Tensions

- Causes and Consequences

- The New Deal

- The Failures of Diplomacy

- The Second World War

- The Home Front

- Wartime Diplomacy

- Containment

- Conflict in Asia

- Red Scare -- Again

- Internal Improvements

- Foreign Policy

- Challenging Jim Crow

- Consequences of the Civil Rights Movement

- Material Culture

- JFK - John F. Kennedy

- LBJ - Lyndon Baines Johnson

- Nixon and Foreign Policy

- Nixon and Domestic Issues

- Ford, Carter, and Reagan

- Moving into a New Millennium

- 695,409 views (163 views per day)

- Posted 12 years ago

Progressive Presidents: Roosevelt, Taft, and Wilson

Introduction.

The Progressive Era in American history, spanning roughly from the late 19th century to the early 20th century, was a period of significant social, political, and economic change. During this transformative time, a group of presidents emerged, each leaving an indelible mark on the nation’s history and paving the way for a more progressive America.

In this 3,000-word essay, we will delve into the roles and contributions of three influential leaders of this era: Presidents Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson. Each of these leaders brought their unique vision and policies to the forefront, shaping the course of the Progressive movement and the nation as a whole.

Theodore Roosevelt: The Trustbuster

As we explore the Progressive Era, we must first turn our attention to Theodore Roosevelt, a larger-than-life figure who ascended to the presidency in the wake of President William McKinley’s assassination in 1901. Roosevelt’s ascent to the highest office in the land marked a turning point in American politics.

Roosevelt, known for his boundless energy and strong-willed persona, embarked on a mission to confront the immense power held by corporate trusts and monopolies. His approach, often described as “trust-busting,” aimed to break the stranglehold that these monopolistic entities had on various industries.

During his presidency, Roosevelt championed antitrust legislation such as the Sherman Antitrust Act and the Hepburn Act, which aimed to curb the excessive influence of big business and promote fair competition. He was not afraid to take on corporate giants like Standard Oil and Northern Securities, earning him the nickname “Trustbuster-in-Chief.”

However, Roosevelt’s legacy extended beyond trust-busting. He was also a fervent advocate for conservation and environmental protection. Through initiatives like the establishment of national parks and monuments, he laid the groundwork for the modern environmental movement.

As we delve deeper into the Progressive era, we will examine Theodore Roosevelt’s policies, his impact on the Progressive movement, and the enduring legacy he left on the American political landscape.

William Howard Taft: The Era of Dollar Diplomacy

William Howard Taft, who succeeded Theodore Roosevelt as the 27th President of the United States in 1909, faced the formidable task of following in the footsteps of his dynamic predecessor. Taft’s presidency marked a continuation of the Progressive movement, albeit with a distinct emphasis on foreign policy and economic interests.

One of Taft’s notable policies was his approach to foreign affairs, famously known as “Dollar Diplomacy.” This foreign policy doctrine aimed to promote American economic interests abroad by using diplomatic means to support American businesses in foreign markets. In essence, it sought to replace “bullets with dollars” as a means of exerting influence.

Under Dollar Diplomacy, Taft’s administration encouraged American businesses to invest in Latin American and East Asian countries, particularly in industries such as infrastructure, mining, and banking. The idea was to strengthen economic ties with these nations and, in doing so, promote political stability and American influence in regions historically prone to instability.

While Dollar Diplomacy had its proponents who saw it as a pragmatic approach to international relations, it also faced criticism. Some argued that it amounted to economic imperialism , as it often prioritized the interests of American corporations over the sovereignty of foreign nations. Taft’s approach drew controversy and tensions in various parts of the world, including in countries like Nicaragua and China.

Despite the challenges and criticisms, William Howard Taft made significant contributions to the Progressive agenda. His administration continued to enforce antitrust laws, and he advocated for safety regulations in the workplace, a move aimed at protecting the rights and well-being of American workers.

As we delve deeper into Taft’s presidency, we will analyze the complexities of Dollar Diplomacy, the domestic policies of his administration, and his place in the broader context of the Progressive Era.

Woodrow Wilson: The Progressive Reformer

Woodrow Wilson, the 28th President of the United States, assumed office in 1913 with a vision of reform and a commitment to advancing the principles of the Progressive movement. His presidency marked a distinct phase in the evolution of progressivism, characterized by his “New Freedom” agenda and his transformative impact on domestic and foreign policy.

Wilson’s background as a former governor of New Jersey and a scholar of political science provided him with a unique perspective on governance. He believed in restoring economic competition and fairness, and he sought to break up monopolistic corporations, much like Roosevelt and Taft before him.

The centerpiece of Wilson’s domestic agenda was the implementation of the “New Freedom” platform, which aimed to promote small businesses, reduce the power of big corporations, and enhance individual economic liberty. Key legislative achievements during his presidency included the Federal Reserve Act and the Clayton Antitrust Act, which aimed to regulate banks and curb anticompetitive practices, respectively.

Furthermore, Wilson’s commitment to social and labor reforms resulted in the establishment of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to monitor business practices and protect consumers. His presidency also saw the introduction of labor reforms, such as the Adamson Act, which established an eight-hour workday for railroad workers.

Woodrow Wilson’s progressive ideals extended to foreign policy as well. He advocated for a foreign policy based on moral principles and self-determination. Although initially reelected in 1916 with the campaign slogan “He Kept Us Out of War” regarding World War I, Wilson eventually led the United States into the conflict, believing it was a war to make the world “safe for democracy.”

As we examine Woodrow Wilson’s presidency in greater detail, we will delve into his domestic and foreign policies, the impact of the New Freedom agenda, and the legacy he left on the Progressive movement and the world stage.

Comparing the Progressive Presidents

As we explore the Progressive Era through the lenses of Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson, it becomes evident that each of these leaders made significant contributions to the Progressive movement, albeit with distinctive approaches and priorities. Comparing and contrasting their presidencies offers valuable insights into the diversity of progressive ideals and actions during this transformative period.

While all three presidents shared a commitment to addressing the excesses of big business and promoting fairness, they differed in their strategies. Roosevelt, often hailed as the “Trustbuster-in-Chief,” focused on antitrust legislation and conservation, aiming to tame corporate giants and protect natural resources. Taft, on the other hand, introduced the concept of “Dollar Diplomacy,” prioritizing economic interests in foreign policy. Wilson, with his New Freedom agenda, emphasized the importance of individual economic liberty and pushed for comprehensive domestic reforms.

Moreover, their foreign policies diverged significantly. Roosevelt was known for his active involvement in international affairs, exemplified by his mediation efforts in the Russo-Japanese War and his pursuit of a “big stick” diplomacy. Taft, through Dollar Diplomacy, aimed to exert American influence through economic means. Wilson, in contrast, initially focused on neutrality in international conflicts but eventually led the United States into World War I with a vision of promoting global democracy.

Despite these differences, there were also commonalities among the Progressive Presidents. All three recognized the need to address the challenges posed by monopolistic corporations, and each contributed to antitrust legislation in their own way. They shared a commitment to improving the lives of ordinary Americans through labor and social reforms, reflecting the broader ethos of progressivism.

Comparing these presidents allows us to appreciate the multifaceted nature of the Progressive movement and its evolving priorities. It highlights the complexities of leadership during a period of rapid change and the enduring impact of their policies on American society.

Legacy of the Progressive Presidents

The legacies of Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson continue to shape American society and politics to this day. Collectively, they left an indelible mark on the Progressive movement and the nation as a whole.

Roosevelt’s legacy is perhaps most evident in the realm of conservation and environmental protection. His establishment of national parks and monuments laid the foundation for modern environmentalism. Additionally, his trust-busting policies paved the way for greater government regulation of business practices, a trend that would persist in the decades to come.

Taft’s legacy is closely tied to the concept of Dollar Diplomacy, which, although controversial, marked a shift in how the United States engaged with the world economically. It set a precedent for American economic involvement abroad, influencing future foreign policy decisions.

Woodrow Wilson’s legacy is notable for the enduring principles of his New Freedom agenda, including the creation of the Federal Reserve System and the protection of consumers through the FTC. His vision of self-determination and global democracy also played a pivotal role in shaping the nation’s role on the international stage.

Furthermore, the Progressive Presidents left a lasting impact on the trajectory of American politics. Their commitment to addressing economic inequality, regulating corporate power, and improving the lives of ordinary citizens set a precedent for future generations of leaders and progressive movements. The foundations they laid in areas such as antitrust legislation, environmental conservation, and labor rights continue to influence policy discussions and reforms in the 21st century.

Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson, as the Progressive Presidents of their time, navigated the complexities of a rapidly changing America. Each brought their unique approach to addressing the challenges of the era, leaving behind a legacy that continues to shape the nation’s politics and policies.

Roosevelt’s trust-busting efforts and conservation initiatives, Taft’s Dollar Diplomacy, and Wilson’s New Freedom agenda all played pivotal roles in advancing the ideals of the Progressive movement. While their methods and priorities differed, their collective impact on American society, both domestically and in the realm of foreign affairs, was profound.

As we reflect on the Progressive Era and the contributions of these Presidents, we must recognize that their legacy extends far beyond their time in office. Their commitment to social justice, economic fairness, and the well-being of the American people continue to inspire leaders and movements seeking to build a more equitable and progressive future for the United States.

Their stories remind us of the enduring power of leadership and the potential for positive change in even the most challenging of times. The Progressive Presidents of the early 20th century have left an enduring mark on American history, one that serves as a testament to the enduring spirit of progress and reform.

Class Notes – Theodore Roosevelt – Progressive President

The actions of the muckrakers and a newly active middle class were heard by the then Vice President of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt. When the President, a very conservative William McKinley was assassinated, Roosevelt became President. Roosevelt was the son of a wealthy old money family. He was involved in government from when he was very young. It was his belief that the wealthy had an obligation to serve. This led him to government service. He became the Assistant Secretary of War, left to form the Rough Riders and took them to Cuba where he fought in the famous battle of San Juan Hill during the taking of Cuba in the Spanish American War .

I. Theodore Roosevelt – Progressive

A. The “ Square Deal ” – Reforms – Increase in Federal Power, ended Laissez Faire. ( Result of Roosevelt’s belief in “Noblesse Oblige.” ) “Let the watchwords of all our people be the old familiar watchwords of honesty, decency, fair-dealing, and commonsense.”… “We must treat each man on his worth and merits as a man. We must see that each is given a square deal, because he is entitled to no more and should receive no less.””The welfare of each of us is dependent fundamentally upon the welfare of all of us.” –New York State Fair, Syracuse September 7, 1903

1. Sherman Anti trust Act (Felt trusts should be judged on actions)

2. Mediated Coal Strike

3. Elkins Act (1903)

-Made it illegal for railroads and shippers to offer rate rebates. Railroad had to set rates. They couldn’t change w/out notice.

4. Hepburn Act (1906)

-Gave ICC the power to set maximum railroad rates.

5. Pure Food and Drug Act – Passed in 1906 and amended in 1911 to include a prohibition on misleading labeling.

6. Meat Inspection Act (1906)

7. Conservation

-Strengthening of Forest Bureau and created National Forest Service. -Creation of much national park land. -Appointment of Gifford Pinchot, professional conservationist to be in charge of national forests.

B. Roosevelt and William Howard Taft

1. Roosevelt did not run for a third term. 2. He was only in his mid fifties. 3. Stayed involved in politics. 4. Became dissatisfied with Taft and ran for a third term with a third party, the Progressive Party, which was later nicknamed the “Bull Moose Party.” Bull Moose Party–Nickname for the Progressive Party of 1912. The bull moose was the emblem for the party, based on Roosevelt’s boasting that he was “as strong as a bull moose.”

C. Election of 1912

1. Roosevelt runs for the Progressive Party a.k.a. The Bull Moose Party. 2. Republicans split and the Democratic candidate Woodrow Wilson won

Woodrow Wilson – Progressive President

When Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat won the election of 1912 he received only 42% of the vote. The Progressive candidates; Roosevelt, Taft and Debs totaled 58% of the vote. Clearly America still sought progressive change. Wilson, an educator and the son of a Presbyterian Minister, recognized this and embarked on a program to continue Progressive reform called the “New Freedom.”

I. Woodrow Wilson – The “ New Freedom ” reforms

A. Underwood Tariff of 1913 -First lowering of tariffs since the Civil War -Went against the protectionist lobby

B. Federal Trade Act (1914)

-Set up FTC or Federal Trade Commission to investigate and halt unfair and illegal business practices. The FTC could put a halt to these illegal business practices by issuing what is known as a “cease and desist order.”

C. Clayton Antitrust Act (1914)

-Declared certain businesses illegal (interlocking directorates, trusts, horizontal mergers) -Unions and the Grange were not subject to antitrust laws. This made unions legal! -Strikes, boycotts, picketing and the collection of strike benefit funds ruled legal

C. Creation of Federal Reserve System (1914)

– Federal Reserve Banks in 12 districts would print and coin money as well as set interest rates. In this way the “Fed,” as it was called, could control the money supply and effect the value of currency. The more money in circulation the lower the value and inflation went up. The less money in circulation the greater the value and this would lower inflation.

D. Federal Farm Loan Act set up Farm Loan Banks to support farmers.

Help inform the discussion

- X (Twitter)

Theodore Roosevelt: Impact and Legacy

Theodore Roosevelt is widely regarded as the first modern President of the United States. The stature and influence that the office has today began to develop with TR. Throughout the second half of the 1800s, Congress had been the most powerful branch of government. And although the presidency began to amass more power during the 1880s, Roosevelt completed the transition to a strong, effective executive. He made the President, rather than the political parties or Congress, the center of American politics.

Roosevelt did this through the force of his personality and through aggressive executive action. He thought that the President had the right to use any and all powers unless they were specifically denied to him. He believed that as President, he had a unique relationship with and responsibility to the people, and therefore wanted to challenge prevailing notions of limited government and individualism; government, he maintained, should serve as an agent of reform for the people.

His presidency endowed the progressive movement with credibility, lending the prestige of the White House to welfare legislation, government regulation, and the conservation movement. The desire to make society more fair and equitable, with economic possibilities for all Americans, lay behind much of Roosevelt's program. The President also changed the government's relationship to big business. Prior to his presidency, the government had generally given the titans of industry carte blanche to accomplish their goals. Roosevelt believed that the government had the right and the responsibility to regulate big business so that its actions did not negatively affect the general public. However, he never fundamentally challenged the status of big business, believing that its existence marked a naturally occurring phase of the country's economic evolution.

Roosevelt also revolutionized foreign affairs, believing that the United States had a global responsibility and that a strong foreign policy served the country's national interest. He became involved in Latin America with little hesitation: he oversaw the Panama Canal negotiations to advocate for U.S. interests and intervened in Venezuela and Santo Domingo to preserve stability in the region. He also worked with Congress to strengthen the U.S. Navy, which he believed would deter potential enemies from targeting the country, and he applied his energies to negotiating peace agreements, working to balance power throughout the world.

Even after he left office, Roosevelt continued to work for his ideals. The Progressive Party's New Nationalism in 1912 launched a drive for protective federal regulation that looked forward to the progressive movements of the 1930s and the 1960s. Indeed, Roosevelt's progressive platform encompassed nearly every progressive ideal later enshrined in the New Deal of Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Fair Deal of Harry S. Truman, the New Frontier of John F. Kennedy, and the Great Society of Lyndon B. Johnson.

In terms of presidential style, Roosevelt introduced "charisma" into the political equation. He had a strong rapport with the public and he understood how to use the media to shape public opinion. He was the first President whose election was based more on the individual than the political party. When people voted Republican in 1904, they were generally casting their vote for Roosevelt the man instead of for him as the standard-bearer of the Republican Party. The most popular President up to his time, Roosevelt used his enthusiasm to win votes, to shape issues, and to mold opinions. In the process, he changed the executive office forever.

Sidney Milkis

Professor of Politics University of Virginia

More Resources

Theodore roosevelt presidency page, theodore roosevelt essays, life in brief, life before the presidency, campaigns and elections, domestic affairs, foreign affairs, life after the presidency, family life, the american franchise, impact and legacy (current essay).

Brewminate: A Bold Blend of News and Ideas

The Progressive Presidents: Teddy Roosevelt, Taft, and Wilson

Share this:.

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

The ownership of corporations and the relationship between owners and laborers were the contentious topics of the period.

Roosevelt’s Square Deal

At the dawn of the twentieth century, America was at a crossroads. Presented with abundant opportunity, but also hindered by significant internal and external problems, the country was seeking leaders who could provide a new direction. The political climate was ripe for reform, and the stage was set for the era of the Progressive Presidents, beginning with Republican Theodore Roosevelt.

Teddy Roosevelt was widely popular due to his status as a hero of the Spanish-American War and his belief in “speaking softly and carrying a big stick.” Taking over the presidency in 1901 after the assassination of William McKinley, he quickly assured America that he would not take any drastic measures. He then demanded a “Square Deal” that would address his primary concerns for the era—the three C’s: control of corporations, consumer protection, and conservation.

The ownership of corporations and the relationship between owners and laborers, as well as government’s role in the relationship, were the contentious topics of the period. Workers were demanding greater rights and protection, while corporations expected labor to remain cheap and plentiful. This conflict came to a head in 1902, with the anthracite coal strike in Pennsylvania. Coal mining was dirty and dangerous work, and 140,000 miners went on strike and demanded a 20 percent pay increase and a reduction in the workday from ten to nine hours. The mine owners were unsympathetic and refused to negotiate with labor representatives. With the approach of winter the dwindling coal supply began to cause concern throughout the nation.

Roosevelt, going against established precedent, decided to step in. He summoned the mine owners and union representatives to meet with him in Washington. Roosevelt was partly moved by strong public support and took the side of the miners. Still, the mine owners were reluctant to negotiate until Roosevelt, threatening to use his “big stick,” declared that he would seize the mines and operate them with federal troops. Owners reluctantly agreed to arbitration, where the striking workers received a 10 percent pay increase and a nine-hour working day. This was the first time a president sided with unions in a labor dispute, and it helped cement Roosevelt’s reputation as a friend of the common people and gave his administration the nickname “The Square Deal.”

Emboldened by this success and in pursuit of the first element of his Square Deal, Roosevelt began to attack large, monopolistic corporations. Some trusts were effective and legitimate, but many of these companies engaged in corrupt and preferential business practices. In 1902, the Northern Securities Company, owned by J.P. Morgan and James J. Hill, controlled most of the railroads in the northwestern United States and intended to create a total monopoly. Roosevelt initiated legal proceedings against Northern Securities and eventually the Supreme Court ordered that the company be dissolved. Roosevelt’s radical actions angered big business and earned him the reputation of a “trust buster,” despite the fact that his successors Taft and Wilson actually dissolved more trusts.

In 1903, with urging from Roosevelt, Congress created the Department of Commerce and Labor (DOCL). This cabinet-level department was designed to monitor corporations and ensure that they engaged in fair business practices. The Bureau of Corporations was created under the DOCL to benefit consumers by monitoring interstate commerce, helping dissolve monopolies, and promoting fair competition between companies. In 1913, the DOCL was split into two separate entities, the Department of Commerce and the Department of Labor, both of which continue to play an important role in regulating business today.

The railroad business continued to be one of the most powerful and influential industries. Like many companies of the time, railroad companies engaged in corrupt business practices such as rebating and price fixing. Roosevelt encouraged Congress to take action to address these abuses, and in 1903 they passed the Elkins Act, which levied heavy fines on companies that engaged in illegal rebating. In 1906, they passed the Hepburn Act, which greatly strengthened the Interstate Commerce Commission. This law allowed the Commission to set maximum rates, inspect a company’s books, and investigate railroads, sleeping car companies, oil pipelines, and other transportation firms. This was a bold action by Roosevelt and Congress given the transportation industry was a powerful lobbyist and a significant political contributor.

The second element of Roosevelt’s Square Deal was consumer protection. In the early 1900s, there was little regulation of the food or drugs that were available to the public. In 1906, Upton Sinclair published a book called The Jungle that described in graphic detail the Chicago slaughterhouse industry. Sinclair intended for his book to expose the plight of immigrant workers and possibly bring readers to the Socialist movement, but people were instead shocked and sickened by the practices of the meat industry.

Roosevelt had the power to do something about the horrors described in The Jungle . He immediately appointed a special investigating committee to look into food handling practices in Chicago. Their report confirmed much of what Sinclair had written. Roosevelt was shocked by the report and predicted that it could have a devastating effect on American meat exports. He agreed to keep it quiet on the condition that Congress would take action to address the issues.

After much pressure from Roosevelt, Congress reluctantly agreed to pass the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. Many members of Congress were reluctant to pass these laws, as the meat industry was a powerful lobbying force. However, the passage of this legislation helped prevent the adulteration and mislabeling of food, alcohol, and drugs. It was an important first step toward ensuring that Americans were buying safe and healthy products. Eventually, the meatpacking industry welcomed these reforms, as they found that a government seal of approval would help increase their export revenues.

The final element of Roosevelt’s Square Deal was conservation. Roosevelt was widely known as a sportsman, hunter, and outdoorsman, and he had a genuine love and respect for nature. However, many Americans of the time viewed the country’s natural resources as limitless. For example, many farmers, ranchers, and timber companies in the west were consuming a huge portion of the available resources at an alarming rate. Their primary obsession was profit, and they had little concern for the damage they were causing. However, there was a small but vocal population who had a great deal of concern for the environment. Fortunately for them and for future Americans, the environmentalists had a friend in Teddy Roosevelt.

Environmentalism and conservation were not new ideas, but most had not been concerned with ecological issues. While a number of laws had been passed to prevent or limit the destruction of natural resources, the majority of this legislation was not enforced or lacked the teeth necessary to make a significant difference.

With Roosevelt’s urging, Congress passed the Newlands Act of 1902. This legislation allowed the federal government to sell public lands in the arid, desert western states and devote the proceeds to irrigation projects. Landowners would then repay part of the irrigation costs from the proceeds they received from their newly fertile land, and this money was earmarked for more irrigation projects. Eventually, dozens of dams were created in the desert including the massive Roosevelt Dam on Arizona’s Salt River.

Another major concern of environmentalists was the devastation of the nation’s timberlands. By 1900, only about 25 percent of the huge timber preserves were still standing. Roosevelt set aside 125 million acres of timberlands as federal reserves, over three times the amount preserved by all of his predecessors combined. He also performed similar actions with coal and water reserves, thus guaranteeing the preservation of some natural resources for future generations. Environmentalists such as John Muir, Gifford Pinchot, and the upstart Sierra Club aided Roosevelt in his efforts. Preserving America’s natural resources and calling attention to the desperate need for conservation may well have been Teddy Roosevelt’s greatest achievement as President, and his most enduring legacy.

Taft’s Administration

In 1908, President Teddy Roosevelt could have easily carried his burgeoning popularity to a sweeping victory in the presidential election, but in 1904 he made an impulsive promise not to seek a second elected term. However, he did not intend to completely relinquish control, so he handpicked a successor. Howard Taft, the 350-pound Secretary of War, was chosen as the Republican candidate for 1908. Taft was a mild progressive and an easygoing man that Roosevelt and other Republican leaders felt they could control. Taft easily defeated the Democratic candidate, William Jennings Bryan, and the Socialist candidate, Eugene Debs, in what can be construed as continued public endorsement of Roosevelt.

Unfortunately, from the onset of his administration Taft did not live up to Roosevelt’s standards or the expectations of other Progressives. He lacked Roosevelt’s strength of personality and was more passive in his dealings with Congress. Many politicians were surprised to learn that Taft did not share some of the Progressive ideas and policies that Roosevelt endorsed. In fact, many people felt that Taft lacked the mental and physical stamina necessary to be an effective President.

The first major blow to the Progressives during Taft’s administration was the Payne-Aldrich Tariff of 1909. Taft called a special session of Congress to address what many people felt were excessive tariffs. After this session, the House of Representatives passed a bill that moderately restricted tariffs, but their legislation was severely modified when it reached the Senate. Radical Senators, led by Nelson W. Aldrich of Rhode Island, tacked on hundreds of revisions that effectively raised tariffs on almost all products. Taft eventually signed the bill and declared it “the best bill that the Republican Party ever passed.” This action dumbfounded Progressives and marked the beginning of an internal struggle for control of the Republican Party.

Another issue that caused dissension among Republicans was Taft’s handling of conservation issues. Taft was a dedicated conservationist and he devoted extensive resources to the protection of the environment. However, most of his progress was undone by his handling of the Ballinger-Pinchot dispute. Pinchot, the leader of the Department of Forestry and a well-liked ally of Roosevelt, attacked Secretary of the Interior Richard Ballinger for how he handled public lands.

Ballinger opened up thousands of acres of public lands in Wyoming, Montana, and Alaska for private use, and this angered many Progressives. Pinchot was openly critical of Ballinger, and in 1910 Taft responded by firing Pinchot for insubordination. This infuriated much of the public as well as the legions of political players who were still fiercely loyal to Roosevelt.

A major rift occurred in the Republican Party as a result of Taft’s straying from Progressive policy. The party was split down the middle between the “Old Guard” Republicans who supported Taft and the Progressive Republicans who backed Roosevelt. This division in the Republican Party allowed Democrats to regain control of the House of Representatives in a landslide victory in the congressional elections of 1910.

In early 1912, Roosevelt triumphantly returned and announced himself as a challenger for the Republican presidential nomination. Roosevelt and his followers, embracing “New Nationalism,” began to furiously campaign for the nomination. However, as a result of their late start and Taft’s ability as incumbent to control the convention, they were unable to secure the delegates necessary to win the Republican candidacy. Not one to admit defeat, Roosevelt formed the “Bull Moose” Party and vowed to enter the race as a third-party candidate.

The split in the Republican Party made the Democrats optimistic about regaining the White House for the first time since 1897. They sought a reformist candidate to challenge the Republicans, and decided on Woodrow Wilson, a career academic and the current progressive governor of New Jersey. Wilson’s “New Freedom” platform sought reduced tariffs, banking reform, and stronger antitrust legislation. The Socialists again nominated Eugene V. Debs whose platform sought public ownership of resources and industries. As expected, Roosevelt and Taft split the Republican vote, and Wilson easily won a majority of the electoral votes. Having received only 41 percent of the popular vote, Wilson was a minority president.

Wilson’s New Freedom

Upon taking office, Woodrow Wilson became only the second Democratic president since 1861. Wilson was a trim figure with clean-cut features and pince-nez glasses clipped to the bridge of his nose, giving him an academic look. Partly due to his academic background and limited political experience, Wilson was very much an idealist. He was intelligent and calculating, but the public perception was that he was emotionally cold and distant. Wilson arrived in the White House with a clear agenda and the drive to achieve all of his goals. In addition, the Democratic majority in both houses of Congress was eager to show the public that their support was not misdirected.

Wilson’s platform called for an assault on “the triple wall of privilege,” which consisted of tariffs, banks, and trusts, and rarely has a president set to work so quickly. His first objective was to reduce the prohibitive tariffs that hurt American businesses and consumers. In an unprecedented move, Wilson personally appeared before Congress to call a special session to discuss tariffs in early 1913. Moved and stunned by Wilson’s eloquence and force of character, Congress immediately designed the Underwood Tariff Bill, which significantly reduced import fees.

The Underwood Tariff Bill brought the first significant reduction of duties since before the Civil War. In order to make up for the loss in revenues caused by the lower tariffs, the Underwood Bill introduced a graduated income tax. This new tax was introduced under the authority of the recently ratified Sixteenth Amendment. Initially, the tax was levied on incomes over $3,000, which was significantly higher than the national average. However, by 1917 the revenue from income taxes greatly exceeded receipts from the tariff. This margin has continued to grow exponentially over the years.

After tackling the tariff, Wilson turned his attention to the nation’s banks. The country’s financial structure was woefully outdated, and its inefficiencies had been exposed by the Republican’s economic expansion and the Panic of 1907. The currency system was very inelastic, with most reserves concentrated in New York and a few other large cities. These resources could not be mobilized quickly in the event of a financial crisis in a different area. Wilson considered two proposals: one calling for a third Bank of the United States, the other seeking a decentralized bank under government control.

Siding with public opinion, Wilson called another special session of Congress in June of 1913. He overwhelmingly endorsed the idea of a decentralized bank, and asked Congress to radically change the banking system. Congress passed the Federal Reserve Act, which was arguably the greatest piece of legislation between the Civil War and Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. The Act created a Federal Reserve Board, which oversaw a system of 12 regional reserve districts, each with its own central bank. This new system also issued Federal Reserve Notes, paper currency that quickly allowed the government to adjust the flow of money, which are still in use today. The Federal Reserve Act was instrumental in allowing America to meet the financial challenges of World War I and emerge from the war as one of the world’s financial powers.

Emboldened by his successes, President Wilson turned his attention to the trusts. Although legislation designed to address the issue of trusts had existed for many years, they were still very much a problem. Again, Wilson appeared before Congress and delivered an emotional and dramatic address. He asked Congress to create legislation that would finally address trusts and tame the rampant monopolies. After several months of discussion, Congress presented Wilson with the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914. This act allowed the government to closely inspect companies engaged in interstate commerce, such as meatpackers and railroads. The Commission investigated unfair trading practices such as false advertising, monopolistic practices, bribery, and misrepresentation.

Following closely behind the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914, was the Clayton Act of 1914. It served to strengthen the Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890 (the first measure passed by the U.S. Congress to prohibit trusts) and redefine the practices that were considered monopolistic and illegal. The Clayton Act provided support for labor unions by exempting labor from antitrust prosecution and legalizing strikes and peaceful picketing, which were not part of the Sherman Act. Renowned American Federation of Labor union leader, Samuel Gompers, declared the Clayton Act the “Magna Carta” of labor. Unfortunately, labor’s triumph was short-lived, as conservative judges continued to curtail union power in controversial decisions.

The era of the Progressive presidents produced a number of notable achievements. Trust-busting forced industrialists and monopolistic corporations to consider public opinion when making business decisions. This benefited the consumer and helped grow the economy. The Progressive presidents also increased consumers’ rights by limiting corporate abuses and trying to ensure the safe labeling of food and drugs. The creation of a federal income tax system lowered tariffs and increased America’s presence as a global trading partner. It also raised additional revenues, some of which were used for beneficial programs such as conservation. The Progressive presidents served to strengthen the office of the president and the public began to expect more from the executive branch. Progressivism as a concept helped challenge traditional thinking about government’s relationship to the people and sparked new ideas that stimulated thought for decades to come.

Along with these significant accomplishments, the Progressive movement also had a number of notable shortcomings. Due to several contrary schools of thought within the movement, goals were often confusing and contradictory. Although most Progressives had good intentions, their conflicting goals helped detract from the overall objectives of the movement. Despite the numerous successes and lofty goals and ideals of the Progressive movement, the federal government was still too greatly influenced by industry and big business. The Progressive movement was not a complete success, but it did serve to spark new ideas and new ways of thinking about business and government. It created a new school of thought that challenged traditional ideas and allowed several new politicians to break the mold and lead the country in a new direction. This new way of thinking proved vital for the United States as the First World War loomed on the horizon.

Originally published by AP Study Notes , republished with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- 20th Century: Post-1945

- 20th Century: Pre-1945

- African American History

- Antebellum History

- Asian American History

- Civil War and Reconstruction

- Colonial History

- Cultural History

- Early National History

- Economic History

- Environmental History

- Foreign Relations and Foreign Policy

- History of Science and Technology

- Labor and Working Class History

- Late 19th-Century History

- Latino History

- Legal History

- Native American History

- Political History

- Pre-Contact History

- Religious History

- Revolutionary History

- Slavery and Abolition

- Southern History

- Urban History

- Western History

- Women's History

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Progressives and progressivism in an era of reform.

- Maureen A. Flanagan Maureen A. Flanagan Department of Humanities, Illinois Institute of Technology

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.84

- Published online: 05 August 2016

The decades from the 1890s into the 1920s produced reform movements in the United States that resulted in significant changes to the country’s social, political, cultural, and economic institutions. The impulse for reform emanated from a pervasive sense that the country’s democratic promise was failing. Political corruption seemed endemic at all levels of government. An unregulated capitalist industrial economy exploited workers and threatened to create a serious class divide, especially as the legal system protected the rights of business over labor. Mass urbanization was shifting the country from a rural, agricultural society to an urban, industrial one characterized by poverty, disease, crime, and cultural clash. Rapid technological advancements brought new, and often frightening, changes into daily life that left many people feeling that they had little control over their lives. Movements for socialism, woman suffrage, and rights for African Americans, immigrants, and workers belied the rhetoric of the United States as a just and equal democratic society for all its members.

Responding to the challenges presented by these problems, and fearful that without substantial change the country might experience class upheaval, groups of Americans proposed undertaking significant reforms. Underlying all proposed reforms was a desire to bring more justice and equality into a society that seemed increasingly to lack these ideals. Yet there was no agreement among these groups about the exact threat that confronted the nation, the means to resolve problems, or how to implement reforms. Despite this lack of agreement, all so-called Progressive reformers were modernizers. They sought to make the country’s democratic promise a reality by confronting its flaws and seeking solutions. All Progressivisms were seeking a via media, a middle way between relying on older ideas of 19th-century liberal capitalism and the more radical proposals to reform society through either social democracy or socialism. Despite differences among Progressives, the types of Progressivisms put forth, and the successes and failures of Progressivism, this reform era raised into national discourse debates over the nature and meaning of democracy, how and for whom a democratic society should work, and what it meant to be a forward-looking society. It also led to the implementation of an activist state.

- Progressives

- Progressivisms

- urbanization

- immigration

The reform impulse of the decades from the 1890s into the 1920s did not erupt suddenly in the 1890s. Previous movements, such as the Mugwump faction of the Republican Party and the Knights of Labor, had challenged existing conditions in the 1870s and 1880s. Such earlier movements either tended to focus on the problems of a particular group or were too small to effect much change. The 1890s Populist Party’s concentration on agrarian issues did not easily resonate with the expanding urban population. The Populists lost their separate identity when the Democratic Party absorbed their agenda. The reform proposals of the Progressive era differed from those of these earlier protest movements. Progressives came from all strata of society. Progressivism aimed to implement comprehensive systemic reforms to change the direction of the country.

Political corruption, economic exploitation, mass migration and urbanization, rapid technological advancements, and social unrest challenged the rhetoric of the United States as a just and equal society. Now groups of Americans throughout the country proposed to reform the country’s political, social, cultural, and economic institutions in ways that they believed would address fundamental problems that had produced the inequities of American society.

Progressives did not seek to overturn capitalism. They sought to revitalize a democratic promise of justice and equality and to move the country into a modern Progressive future by eliminating or at least ameliorating capitalism’s worst excesses. They wanted to replace an individualistic, competitive society with a more cooperative, democratic one. They sought to bring a measure of social justice for all people, to eliminate political corruption, and to rebalance the relationship among business, labor, and consumers by introducing economic regulation. 1 Progressives turned to government to achieve these objectives and laid the foundation for an increasingly powerful state.

Social Justice Progressivism

Social justice Progressives wanted an activist state whose first priority was to provide for the common welfare. Jane Addams argued that real democracy must operate from a sense of social morality that would foster the greater good of all rather than protect those with wealth and power. 2 Social justice Progressivism confronted two problems to securing a democracy based on social morality. Several basic premises that currently structured the country had to be rethought, and social justice Progressivism was promoted largely by women who lacked official political power.

Legal Precedent or Social Realism

The existing legal system protected the rights of business and property over labor. 3 From 1893 , when Florence Kelley secured factory legislation mandating the eight-hour workday for women and teenagers and outlawing child labor in Illinois factories, social justice Progressives faced legal obstacles as business contested such legislation. In 1895 , the Supreme Court in Ritchie v. People ruled that such legislation violated the “freedom of contract” provision of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court confined the police power of the state to protecting immediate health and safety, not groups of people in industries. 4 Then, in the 1905 case Lochner v. New York , the Court declared that the state had no interest in regulating the hours of male bakers. To circumvent these rulings, Kelley, Josephine Goldmark, and Louis Brandeis contended that law should address social realities. The Brandeis brief to the Supreme Court in 1908 , in Muller v. Oregon , argued for upholding Oregon’s eight-hour law for women working in laundries because of the debilitating physical effects of such work. When the Court agreed, social justice Progressives hoped this would be the opening wedge to extend new rights to labor. The Muller v. Oregon ruling had a narrow gender basis. It declared that the state had an interest in protecting the reproductive capacities of women. Henceforth, male and female workers would be unequal under the law, limiting women’s economic opportunities across the decades, rather than shifting the legal landscape. Ruling on the basis of women’s reproductive capacities, the Court made women socially inferior to men in law and justified state-sponsored interference in women’s control of their bodies. 5

Role of the State to Protect and Foster

Women organized in voluntary groups worked to identify and attack the problems caused by mass urbanization. The General Federation of Women’s Clubs ( 1890 ) coordinated women’s activities throughout the country. Social justice Progressives lobbied municipal governments to enact new ordinances to ameliorate existing urban conditions of poverty, disease, and inequality. Chicago women secured the nation’s first juvenile court ( 1899 ). 6 Los Angeles women helped inaugurate a public health nursing program and secure pure milk regulations for their city. Women also secured municipal public baths in Boston, Chicago, Philadelphia, and other cities. Organized women in Philadelphia and Dallas were largely responsible for their cities implementing new clean water systems. Women set up pure milk stations to prevent infant diarrhea and organized infant welfare societies. 7

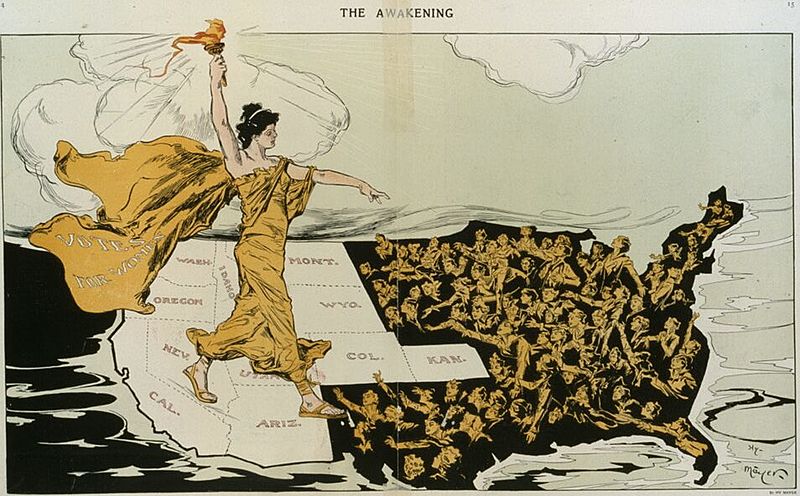

Social justice Progressives sought national legislation to protect consumers from the pernicious effects of industrial production outside of their immediate control. In 1905 , the General Federation of Women’s Clubs initiated a letter-writing campaign to pressure Congress to pass pure food legislation. Standard accounts of the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act and pure milk ordinances generally credit male professionals with putting in place such reforms, but female social justice Progressives were instrumental in putting this issue before the country. 8

Social justice Progressives sought a ban on child labor and protections for children’s health and education. They argued that no society could progress if it allowed child labor. In 1912 they persuaded Congress to establish a federal Children’s Bureau to investigate conditions of children throughout the country. Julia Lathrop first headed the bureau, which was thenceforth dominated by women. Nonetheless, when Congress passed the Keating-Owen Child Labor Act ( 1916 ), banning interstate commerce in products made with child labor, a North Carolina man immediately sued, arguing that it deprived him of property in his son’s labor. The Supreme Court ( 1918 ) ruled the law unconstitutional because it violated state powers to regulate conditions of labor. A constitutional amendment banning child labor ( 1922 ) was attacked by manufacturers and conservative organizations protesting that it would give government power over children. Only four states ratified the amendment. 9

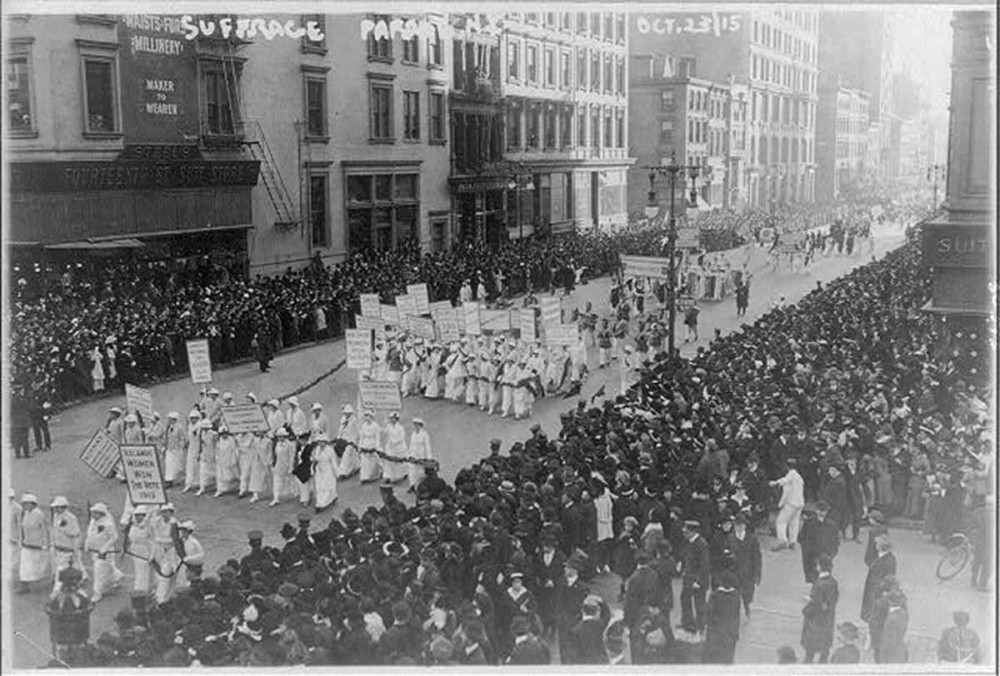

Woman suffrage was crucial for social justice Progressives as both a democratic right and because they believed it essential for their agenda. 10 When suffrage left elected officials uncertain about the power of women’s votes in 1921 , Congress passed the Sheppard-Towner Maternity and Infant Welfare bill, which provided federal funds for maternal and infant health. The American Medical Association opposed the bill as a violation of its expertise. Businessmen and political leaders protested that the federal government should not interfere in health care and objected that it would raise taxes. Congress made Sheppard-Towner a “sunset” act to run for five years, after which it would decide whether to renew it. Congress temporarily extended it but ended the funding in 1929 , even though the country’s infant mortality rate exceeded that of six other industrial countries. The hostility of the male-dominated American Medical Association and the Public Health Service to Sheppard-Towner and to its administration by the Children’s Bureau, along with attacks against the social justice network of women’s organizations as a communist conspiracy to undermine American society, doomed the legislation. 11

New Practices of Democracy

Women established settlement houses, voluntary associations, day nurseries, and community, neighborhood, and social centers as venues in which to practice participatory democracy. These venues intended to bring people together to learn about one another and their needs, to provide assistance for those needing help, and to lobby their governments to provide social goods to people. This was not reform from the bottom; middle-class women almost always led these venues. Most of these efforts were also racially exclusive, but African American women established venues of their own. In Atlanta, Lugenia Hope, who had spent time at Chicago’s Hull House, established the Atlanta Neighborhood Union in 1908 to organize the city’s African American women on a neighborhood basis. Hope urged women to investigate the problems of their neighborhoods and bring their issues to the municipal government. 12

The National Consumers’ League (NCL, 1899 ) practiced participatory democracy on the national level. Arising from earlier working women’s societies and with Florence Kelley at its head, the NCL investigated working conditions and urged women to use their consumer-purchasing power to force manufacturers to institute new standards of production. The NCL assembled and published “white lists” of those manufacturers found to be practicing good employment standards and awarded a “white label” to factories complying with such standards. The NCL’s tactics were voluntary—boycotts were against the law—and they did not convince many manufacturers to change their practices. Even so, such tactics drew more women into the social justice movement, and the NCL’s continuous efforts were rewarded in New Deal legislation. 13

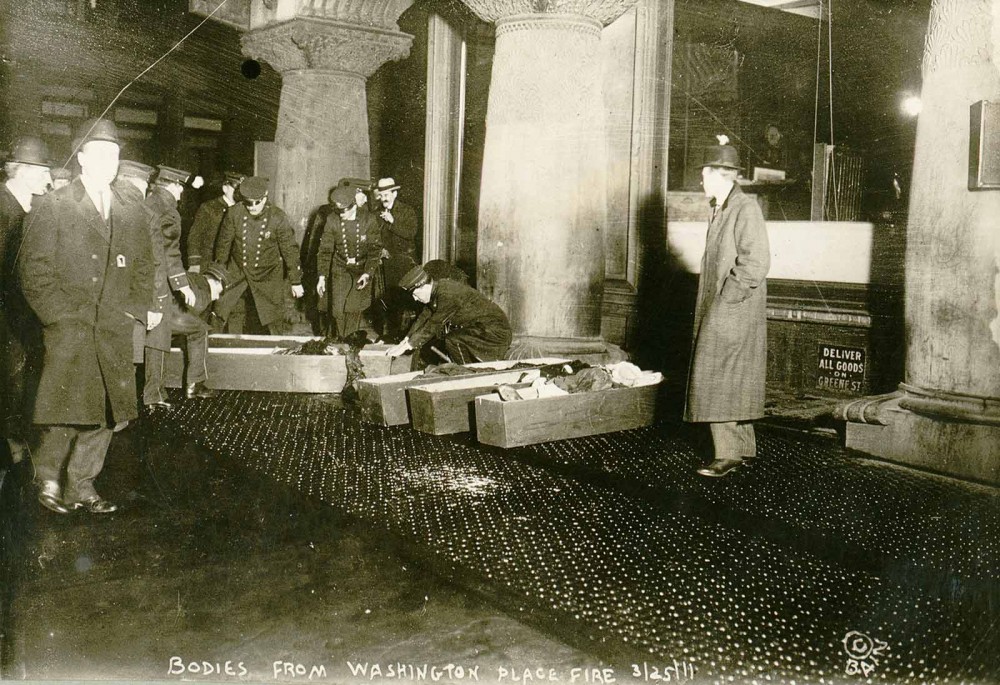

A group of working women and settlement-house residents formed the National Women’s Trade Union League (NWTUL, 1903 ) and organized local affiliates to work for unionization in female-dominated manufacturing. 14 Middle-class women walked the picket lines with striking garment workers and waitresses in New York and Chicago and helped secure concessions from manufacturers. The NWTUL forced an official investigation into the causes of New York City’s Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire ( 1911 ), in which almost 150 workers, mainly young women, died. Members of the NWTUL were organizers for the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union. Despite these participatory venues, much literature on such movements emphasizes male initiatives and fails to appreciate gender differences. The public forums movement promoted by men, such as Charles Sprague Smith and Frederic Howe, was a top-down effort in which prominent speakers addressed pressing issues of the day to teach the “rank and file” how to practice democracy. 15 In Boston, Mary Parker Follett promoted participatory democracy through neighborhood centers organized and run by residents. Chicago women’s organizations fostered neighborhood centers as spaces for residents to gather and discuss neighborhood needs. 16

Suffrage did not provide the political power women had hoped for, but female social justice Progressives occupied key offices in the New Deal administration. They helped write national anti-child labor legislation, minimum wage and maximum hour laws, aid to dependent children, and elements of the Social Security Act. Such legislation at least partially fulfilled the social justice Progressive agenda that activist government provide social goods to protect daily life against the vagaries of the capitalist marketplace.

Political Progressivism

Political Progressivism was a structural-instrumental approach to reform the mechanisms and exercise of politics to break the hold of political parties. Its adherents sought a well-ordered government run by experts to undercut a political patronage system that favored trading votes for services. Political Progressives believed that such reforms would enhance democracy.

Mechanisms and Processes of Electoral Democracy

The Wisconsin Idea promoted by the state’s three-time governor Robert La Follette exemplified the political Progressives’ approach to reform. The plan advocated state-level reforms to electoral procedures. A key proposal of the Wisconsin Idea was to replace the existing party control of all nominations with a popular direct primary. Wisconsin became the first state to require the direct primary. The plan also proposed giving voters the power to initiate legislation, hold referenda on proposed legislation, and recall elected officials. Wisconsin voters adopted these proposals by 1911 , 17 although Oregon was the first state to adopt the initiative and referendum, in 1902 . 18