- CBSE Class 10th

- CBSE Class 12th

- UP Board 10th

- UP Board 12th

- Bihar Board 10th

- Bihar Board 12th

- Top Schools in India

- Top Schools in Delhi

- Top Schools in Mumbai

- Top Schools in Chennai

- Top Schools in Hyderabad

- Top Schools in Kolkata

- Top Schools in Pune

- Top Schools in Bangalore

Products & Resources

- JEE Main Knockout April

- Free Sample Papers

- Free Ebooks

- NCERT Notes

- NCERT Syllabus

- NCERT Books

- RD Sharma Solutions

- Navodaya Vidyalaya Admission 2024-25

- NCERT Solutions

- NCERT Solutions for Class 12

- NCERT Solutions for Class 11

- NCERT solutions for Class 10

- NCERT solutions for Class 9

- NCERT solutions for Class 8

- NCERT Solutions for Class 7

- JEE Main 2024

- MHT CET 2024

- JEE Advanced 2024

- BITSAT 2024

- View All Engineering Exams

- Colleges Accepting B.Tech Applications

- Top Engineering Colleges in India

- Engineering Colleges in India

- Engineering Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- Engineering Colleges Accepting JEE Main

- Top IITs in India

- Top NITs in India

- Top IIITs in India

- JEE Main College Predictor

- JEE Main Rank Predictor

- MHT CET College Predictor

- AP EAMCET College Predictor

- GATE College Predictor

- KCET College Predictor

- JEE Advanced College Predictor

- View All College Predictors

- JEE Advanced Cutoff

- JEE Main Cutoff

- MHT CET Result 2024

- JEE Advanced Result

- Download E-Books and Sample Papers

- Compare Colleges

- B.Tech College Applications

- AP EAMCET Result 2024

- MAH MBA CET Exam

- View All Management Exams

Colleges & Courses

- MBA College Admissions

- MBA Colleges in India

- Top IIMs Colleges in India

- Top Online MBA Colleges in India

- MBA Colleges Accepting XAT Score

- BBA Colleges in India

- XAT College Predictor 2024

- SNAP College Predictor

- NMAT College Predictor

- MAT College Predictor 2024

- CMAT College Predictor 2024

- CAT Percentile Predictor 2024

- CAT 2024 College Predictor

- Top MBA Entrance Exams 2024

- AP ICET Counselling 2024

- GD Topics for MBA

- CAT Exam Date 2024

- Download Helpful Ebooks

- List of Popular Branches

- QnA - Get answers to your doubts

- IIM Fees Structure

- AIIMS Nursing

- Top Medical Colleges in India

- Top Medical Colleges in India accepting NEET Score

- Medical Colleges accepting NEET

- List of Medical Colleges in India

- List of AIIMS Colleges In India

- Medical Colleges in Maharashtra

- Medical Colleges in India Accepting NEET PG

- NEET College Predictor

- NEET PG College Predictor

- NEET MDS College Predictor

- NEET Rank Predictor

- DNB PDCET College Predictor

- NEET Result 2024

- NEET Asnwer Key 2024

- NEET Cut off

- NEET Online Preparation

- Download Helpful E-books

- Colleges Accepting Admissions

- Top Law Colleges in India

- Law College Accepting CLAT Score

- List of Law Colleges in India

- Top Law Colleges in Delhi

- Top NLUs Colleges in India

- Top Law Colleges in Chandigarh

- Top Law Collages in Lucknow

Predictors & E-Books

- CLAT College Predictor

- MHCET Law ( 5 Year L.L.B) College Predictor

- AILET College Predictor

- Sample Papers

- Compare Law Collages

- Careers360 Youtube Channel

- CLAT Syllabus 2025

- CLAT Previous Year Question Paper

- NID DAT Exam

- Pearl Academy Exam

Predictors & Articles

- NIFT College Predictor

- UCEED College Predictor

- NID DAT College Predictor

- NID DAT Syllabus 2025

- NID DAT 2025

- Design Colleges in India

- Top NIFT Colleges in India

- Fashion Design Colleges in India

- Top Interior Design Colleges in India

- Top Graphic Designing Colleges in India

- Fashion Design Colleges in Delhi

- Fashion Design Colleges in Mumbai

- Top Interior Design Colleges in Bangalore

- NIFT Result 2024

- NIFT Fees Structure

- NIFT Syllabus 2025

- Free Design E-books

- List of Branches

- Careers360 Youtube channel

- IPU CET BJMC

- JMI Mass Communication Entrance Exam

- IIMC Entrance Exam

- Media & Journalism colleges in Delhi

- Media & Journalism colleges in Bangalore

- Media & Journalism colleges in Mumbai

- List of Media & Journalism Colleges in India

- CA Intermediate

- CA Foundation

- CS Executive

- CS Professional

- Difference between CA and CS

- Difference between CA and CMA

- CA Full form

- CMA Full form

- CS Full form

- CA Salary In India

Top Courses & Careers

- Bachelor of Commerce (B.Com)

- Master of Commerce (M.Com)

- Company Secretary

- Cost Accountant

- Charted Accountant

- Credit Manager

- Financial Advisor

- Top Commerce Colleges in India

- Top Government Commerce Colleges in India

- Top Private Commerce Colleges in India

- Top M.Com Colleges in Mumbai

- Top B.Com Colleges in India

- IT Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- IT Colleges in Uttar Pradesh

- MCA Colleges in India

- BCA Colleges in India

Quick Links

- Information Technology Courses

- Programming Courses

- Web Development Courses

- Data Analytics Courses

- Big Data Analytics Courses

- RUHS Pharmacy Admission Test

- Top Pharmacy Colleges in India

- Pharmacy Colleges in Pune

- Pharmacy Colleges in Mumbai

- Colleges Accepting GPAT Score

- Pharmacy Colleges in Lucknow

- List of Pharmacy Colleges in Nagpur

- GPAT Result

- GPAT 2024 Admit Card

- GPAT Question Papers

- NCHMCT JEE 2024

- Mah BHMCT CET

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Delhi

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Hyderabad

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Mumbai

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Maharashtra

- B.Sc Hotel Management

- Hotel Management

- Diploma in Hotel Management and Catering Technology

Diploma Colleges

- Top Diploma Colleges in Maharashtra

- UPSC IAS 2024

- SSC CGL 2024

- IBPS RRB 2024

- Previous Year Sample Papers

- Free Competition E-books

- Sarkari Result

- QnA- Get your doubts answered

- UPSC Previous Year Sample Papers

- CTET Previous Year Sample Papers

- SBI Clerk Previous Year Sample Papers

- NDA Previous Year Sample Papers

Upcoming Events

- NDA Application Form 2024

- UPSC IAS Application Form 2024

- CDS Application Form 2024

- CTET Admit card 2024

- HP TET Result 2023

- SSC GD Constable Admit Card 2024

- UPTET Notification 2024

- SBI Clerk Result 2024

Other Exams

- SSC CHSL 2024

- UP PCS 2024

- UGC NET 2024

- RRB NTPC 2024

- IBPS PO 2024

- IBPS Clerk 2024

- IBPS SO 2024

- Top University in USA

- Top University in Canada

- Top University in Ireland

- Top Universities in UK

- Top Universities in Australia

- Best MBA Colleges in Abroad

- Business Management Studies Colleges

Top Countries

- Study in USA

- Study in UK

- Study in Canada

- Study in Australia

- Study in Ireland

- Study in Germany

- Study in China

- Study in Europe

Student Visas

- Student Visa Canada

- Student Visa UK

- Student Visa USA

- Student Visa Australia

- Student Visa Germany

- Student Visa New Zealand

- Student Visa Ireland

- CUET PG 2024

- IGNOU B.Ed Admission 2024

- DU Admission 2024

- UP B.Ed JEE 2024

- LPU NEST 2024

- IIT JAM 2024

- IGNOU Online Admission 2024

- Universities in India

- Top Universities in India 2024

- Top Colleges in India

- Top Universities in Uttar Pradesh 2024

- Top Universities in Bihar

- Top Universities in Madhya Pradesh 2024

- Top Universities in Tamil Nadu 2024

- Central Universities in India

- CUET DU Cut off 2024

- IGNOU Date Sheet

- CUET DU CSAS Portal 2024

- CUET Response Sheet 2024

- CUET Result 2024

- CUET Participating Universities 2024

- CUET Previous Year Question Paper

- CUET Syllabus 2024 for Science Students

- E-Books and Sample Papers

- CUET Exam Pattern 2024

- CUET Exam Date 2024

- CUET Cut Off 2024

- CUET Exam Analysis 2024

- IGNOU Exam Form 2024

- CUET PG Counselling 2024

- CUET Answer Key 2024

Engineering Preparation

- Knockout JEE Main 2024

- Test Series JEE Main 2024

- JEE Main 2024 Rank Booster

Medical Preparation

- Knockout NEET 2024

- Test Series NEET 2024

- Rank Booster NEET 2024

Online Courses

- JEE Main One Month Course

- NEET One Month Course

- IBSAT Free Mock Tests

- IIT JEE Foundation Course

- Knockout BITSAT 2024

- Career Guidance Tool

Top Streams

- IT & Software Certification Courses

- Engineering and Architecture Certification Courses

- Programming And Development Certification Courses

- Business and Management Certification Courses

- Marketing Certification Courses

- Health and Fitness Certification Courses

- Design Certification Courses

Specializations

- Digital Marketing Certification Courses

- Cyber Security Certification Courses

- Artificial Intelligence Certification Courses

- Business Analytics Certification Courses

- Data Science Certification Courses

- Cloud Computing Certification Courses

- Machine Learning Certification Courses

- View All Certification Courses

- UG Degree Courses

- PG Degree Courses

- Short Term Courses

- Free Courses

- Online Degrees and Diplomas

- Compare Courses

Top Providers

- Coursera Courses

- Udemy Courses

- Edx Courses

- Swayam Courses

- upGrad Courses

- Simplilearn Courses

- Great Learning Courses

Democracy In India Essay

Democracy is regarded as the best type of government since it allows citizens to directly elect their leaders. They have access to a number of rights that are fundamental to anyone's ability to live freely and peacefully. There are many democratic countries in the world, but India is by far the biggest. Here are a few sample essays on the topic ‘Democracy In India’.

100 Words Essay On Democracy

200 words essay on democracy, 500 words essay on democracy.

Democracy is a term used to describe a form of government in which the people have a voice by voting. Democracy is an essential part of any society, and India is no exception. After years of suffering under British colonial control, India attained democracy in 1947. India places a great emphasis on democracy. India is also without a doubt the largest democracy in the world.

The spirit of justice, liberty, and equality has permeated Indian democracy ever since the country attained independence. As the world’s largest democracy, India has been a shining example of how democracy can foster progress and ensure rights for all its citizens.

In a democracy, the people have the ultimate say in how their government is run. They elect representatives to represent them in government, and they can hold those representatives accountable through regular elections. And finally, the rule of law is important in a democracy to ensure that everyone is treated equally before the law and that the government operates within its proper bounds. Democracy has been a recent phenomena in human history, only really taking root in the last few centuries. But it has quickly become one of the most popular forms of government around the world. India is one of the world’s largest democracies, with over 1 billion people living within its borders.

India's constitution serves as the foundation for its democracy. The Indian Constitution guarantees equality for all citizens regardless of caste, creed, or religion. It also establishes a system of representative government, with elected officials at the national, state, and local levels. And finally, it enshrines the rule of law by establishing an independent judiciary to interpret and uphold the Constitution.

There are many different types of democracy, but most modern democracies are based on the principles of popular sovereignty, representative government, and rule of law and public opinion.

There are two main types of democracies—direct and representative. Direct democracy allows citizens to participate directly in the decision-making process, while representative democracy allows citizens to elect representatives to make decisions on their behalf. The advantages of democracy in India include the fact that it allows for greater participation of citizens in the political process, and it also provides checks and balances on the government. The disadvantages of democracy in India include the fact that it can be slow to make decisions and that it can be difficult to hold people accountable for their actions.

Features Of Indian Democracy

Sovereignty | One important aspect of Indian democracy is sovereignty. The absolute control a governing body has over itself without external influence is referred to as sovereignty. In India's democracy, people can also exert their power. The fact that Indians choose their representatives is remarkable. Furthermore, these officials continue to be accountable to the general public.

Political Equality | It is the foundation of Indian democracy. It also simply means that everyone is treated equally under the law. The fact that there is no discrimination based on caste, religion, race, creed, or sect is particularly notable. As a result, all Indian citizens have equal political rights.

Rule Of Majority | A key component of Indian democracy is the rule of the majority. Furthermore, the winning party creates and governs the government. In addition, the party with the most seats creates and governs the country. Most importantly, no one can object to majority support.

Socialist | Being socialist implies that the country continuously prioritises the needs of its citizens. The poor person should be offered numerous incentives, and their fundamental needs should be met by any means necessary.

Secular | There is no such thing as a "state religion," and there is no discrimination based on religion in this nation. In the eyes of the law, all religions must be equal; it is not acceptable to discriminate against anyone based on their religion. Everyone has the right to practise and spread any religion, and they are free to do so at any moment.

Advantages And Disadvantages Of Democracy In India

There are many advantages and disadvantages of democracy in India. On the one hand, democracy gives everyone an equal say in how the country is run. This is particularly important in a country as large and diverse as India. On the other hand, democracy can also be slow and chaotic, and it can be difficult to get things done. One advantage of democracy in India is that it ensures that everyone has a say in how the country is run. This is especially important in a country as large and diverse as India.

There are many different languages spoken in India, and democracy ensures that everyone has a voice. Another advantage of democracy in India is that it leads to more stability than other forms of government. In a dictatorship, for example, one person has all the power. This can lead to them making decisions that are not in the best interests of the country. In a democracy, there are checks and balances in place so that no one person has too much power.

Applications for Admissions are open.

Aakash iACST Scholarship Test 2024

Get up to 90% scholarship on NEET, JEE & Foundation courses

JEE Main Important Physics formulas

As per latest 2024 syllabus. Physics formulas, equations, & laws of class 11 & 12th chapters

PW JEE Coaching

Enrol in PW Vidyapeeth center for JEE coaching

JEE Main Important Chemistry formulas

As per latest 2024 syllabus. Chemistry formulas, equations, & laws of class 11 & 12th chapters

TOEFL ® Registrations 2024

Accepted by more than 11,000 universities in over 150 countries worldwide

PTE Exam 2024 Registrations

Register now for PTE & Save 5% on English Proficiency Tests with ApplyShop Gift Cards

Download Careers360 App's

Regular exam updates, QnA, Predictors, College Applications & E-books now on your Mobile

Certifications

We Appeared in

- About Project

- Testimonials

Business Management Ideas

Essay on Democracy in India

List of essays on democracy in india, essay on democracy in india – short essay for children (essay 1 – 150 words), essay on democracy in india – 10 lines on democracy written in english (essay 2 – 250 words), essay on democracy in india (essay 3 – 300 words), essay on democracy in india – what is democracy (essay 4 – 400 words), essay on democracy in india – for school students (class 6, 7 and 8) (essay 5 – 500 words), essay on democracy in india – for college students (essay 6 – 600 words), essay on democracy in indian constitution (essay 7 – 750 words), essay on democracy in india – long essay for competitive exams like ias, ips civil services and upsc (essay 8 – 1000 words).

India is the largest country in the world that follows the Democratic form of government. With a population of over a billion, India is a secular, socialistic, republic, and democratic country in the world.

India is considered as the lighthouse that guides the democratic movement in the African–Asian countries. Democracy in India is backed by our written Constitution which consists of a list of all fundamental laws upon which our nation is to be governed.

January 26, the day on which our Constitution came into effect is celebrated as Republic Day and it was on this day that Democracy truly entered India.

Audience: The below given essays are exclusively written for school students (Class 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 Standard) and college students. Furthermore, those students preparing for competitive exams like IAS, IPS and UPSC can also increase their knowledge by studying these essays.

Introduction:

Democracy in India can be defined as a government by the people, of the people and for the people. In India the government is formed by the citizens through their elected representatives.

Principle of Democracy in India:

In a democracy at least the fundamental rights of the individuals are guaranteed. The five principles by which the democracy in India works are Sovereign, Socialist, Secular, Democratic and Republic.

Enhancement Areas:

Some of the areas in which the Democracy in India can be improved include the eradication of poverty, encouraging people to vote and educate them about choosing the appropriate candidate, increasing literacy etc.

Conclusion:

Democracy in India is one of the biggest in the world and is celebrated worldwide. Given the wide range of culture and diversity, the need of the hour is that democracy is upheld without losing the diverse heritage of which the country is proud of. Democracy in India would be smooth when the emotions of every culture is acknowledged.

India is the largest democracy in the world. The citizens of the country who are above 18 years of age, elect their representatives in the Lok Sabha via secret ballots (general elections). They are elected for a period of 5 years and ministers are chosen from the elected representatives. India became a democratic nation in 1947 and thereafter the leaders were elected by the people of India. Different parties’ campaign using different future agendas and they emphasize on what they did for the development of people between the election periods. This way, the citizens can make an informed choice in selecting a particular representative.

The word democracy is derived from Greek and it literary means ‘power of the people’. The government is run by the people and it if for the people. The model of Indian democracy is followed by the entire Afro-Asian countries. Our form of democracy in India is much different from democracy of other nations like England and USA.

Although the democracy in India is much advanced, there are still some drawbacks which affect the healthy functioning of the system. These include religion and ignorance. Although we say India is a secular country, but there are still people present who believe in treating people from different religions differently. We have advanced from the ancient traditions like Sati but now a days, people kill each other over killing of Cow, which is considered as a sacred animal for Hindus. Other than these, much work needs to be done to reduce and eliminate poverty, illiteracy and gender discrimination among a list of many others.

India is the largest country in the world that follows the Democratic form of government. With a population of over a billion, India is a secular, socialistic, republic, and democratic country in the world. India is considered as the lighthouse that guides the democratic movement in the African–Asian countries.

Meaning of Democracy:

Democracy means ‘by the people, for the people, and of the people’. A democratic country is one whose government is made of the people, elected by the people to serve the people. The Indian country is governed by a parliamentary system of governance which follows the constitution of India. During the past 70 years, India has held regular elections for the legislative and parliamentary assemblies, reflecting the power of the election commission, who is regarded as the powerful authority.

Democracy in India has a very strong foundation that runs deep into the cultural and moral ethics. Thanks to the efficient leaders like Lal Bahadur Shastri, Sardar Vallabhai Patel, Dr. Rajendra Prasad, etc., whose contribution to a successful democratic India is immeasurable.

Principles of Democratic India:

Democracy in India follows five principles. They are:

a) Secular – A place where people are bestowed with the freedom of religion, to follow a religion of their own choice.

b) Social – Providing equality to everyone irrespective of their caste, creed, color, gender, and other differences.

c) Sovereign – A country that is free from the control of any foreign authorities or power.

d) Democratic – A country where the government is made for the people, by the people of the country with the representatives of people.

e) Republic – No hierarchy is followed while the head of the country is elected by regular elections and the power changes at a regular period of interval.

Not only does democracy in India mean that every citizen has the right to vote, but also it says that people – the citizens of India have full right to question the government if the government doesn’t ensure equality to its citizens in all spheres of life. While democracy in India is effective, we have a long way to go to become a successful democratic country. Illiteracy, poverty, discrimination, and other social issues should be eradicated completely to enjoy the real fruit of democracy in India.

The best definition of democracy has been described as the government of the people, by the people and for the people. India became a sovereign democratic nation back in the year 1947 and the country is still on the roads to development.

In true terms, democracy in India would mean a country wherein people can find quality and they have the freedom to express themselves. The ideal nation is going to be truly democratic and this leaves us with a baffling question. Is democracy in India truly established?

Given the state of turmoil which our nation is in, the question indeed has a palpable and sorry answer. To be honest, if democracy in India was legit, people will have the power to choose their destiny. While we do have a voting system in place which gives people the power to elect their representative, it is often seen to be grossly misused.

The Need to Educate and Enlighten:

If we want the largest democracy of the world to truly live up to the meaning of democracy; it is important to both educate and enlighten the masses. More and more people need to understand the power that has been vested in them. When the commoners understand the kind of influence they can have as far as choosing their political leader is concerned; it might help them think meticulously before putting in the vote and can sanctify the meaning of democracy in India.

There are so many people who do not even bother to register a vote. Are they not bothered about the outcome and progress of their nation? Unless, the right measures are taken to truly educate the mass about how democracy in India is the glorious future we should all dream of, things are least likely to change.

Handling the Flaws:

It’s been a long time since we became independent. So, it is important now to handle the flaws in the democracy in India. The seeds of corruption have been very deeply set in our country and one needs to do something as a start to combat the problem.

It is easy to whine and very hard to put up a fight. So, the right thing which you should do is ensure that you do your bit for the sake of improving the state of affairs of the country. Give in your best shot and be hopeful that things will change for the good as far as democracy in India is concerned.

When the people of the country start taking an active part in the welfare of the state, we will achieve the true meaning of democracy in India.

The word Democracy is derived from the Greek words ‘Demos’ and ‘Kratos’. Demos means People and Kratos means Power. Together put, it means People’s Power. Abraham Lincoln described Democracy as ‘Government by the people, for the people and of the people’. The emphasis on people clearly shows that Democracy is a people-centric form of government. Many consider it to be a superior form of governance as it ensures social and economic equality of every citizen in the country.

In India, a Democratic government was formed only after its freedom from the British rule in 1947. However, the practices of a Democratic system in India go way back. Both Rigveda and Atharvaveda have references of a system where the people gather as a whole and elect Kings.

Democracy in India is backed by our written Constitution which consists of a list of all fundamental laws upon which our nation is to be governed. January 26, the day on which our Constitution came into effect is celebrated as Republic Day and it was on this day that Democracy truly entered India.

Types of Democracy:

Democracy is of two types, Direct Democracy and Indirect Democracy.

In Direct Democracy, all the people come together in a single place to elect the governing executives themselves. This is possible for small cities where the population is less and everybody can gather together at one place. Even today, Switzerland exercises a Direct Democracy system.

Indirect Democracy is exercised in countries where there is huge population, making it difficult for all to gather at one place. In this case, people elect representatives who in turn elect the governing executive. Hence in India, Indirect Democracy is practiced.

Five Principles of Indian Democracy:

Democracy in India operates on five important principles:

1. Sovereign: In our country, we Indians are the supreme power and are not controlled by any other foreign power.

2. Socialist: There is economic and social equality promised to every citizen of India.

3. Secular: Every Indian citizen has the freedom to practise his religion of choice.

4. Democratic: Our government is elected by the people.

5. Republic: Supreme power is held by the people and their nominated representatives, instead of a hereditary king.

Working of Indian Democracy:

India has a Federal government where there are separate State governments which come under a single Central government. Indian citizens elect their leaders by the system of voting. Both State and Central elections happen once in five years. Every citizen above the age of eighteen years has the right to vote irrespective of caste, color, creed, religion, gender and education.

Any citizen has the right to stand as a candidate for the post of President and Prime Minister irrespective of religion, gender and education. Elections happen through secret ballots. People elect their representatives of the State who in-turn elect the Head of State, the Chief Minister. Similarly, the public elect the members of the Parliament who in turn elect the Prime Minister.

Democracy in India has succeeded on contrary to the beliefs of many political scientists. Today, India is a pioneer of Democracy in Asia and all other Asian and African countries look up to us for Democratic inspirations.

India is a democratic nation. If you do not know what democracy means, one of the most popular definition has to be, “the government by the people, for the people, of the people.”

So, if we truly want our nation to be democratic and preserve the value of this term, it signifies the fact that the common people should all be a part of the development of the nation. The government should so function that their decisions help in the betterment of the country and the citizens.

Are we truly a democratic nation?

A lot of people argue as to whether or not we are truly democratic, we need to know that there is still a long way to go. As per the books of law and the great Indian constitution, we can see that we are one of the leading democratic countries. However, if you decide to go beyond the books, you will perceive the change. There is a long way to go because democracy has a wider and deeper meaning.

The True Meaning:

Democracy means that people elect the representatives who in turn take charge of the nation and help in the betterment and upliftment of the citizens. While in India, which is a top democratic country, we do have the power to elect our representatives, there is still a lot which needs to be done. Our elected representatives do not understand the importance of the office they are holding. This is why the country has failed to make the kind of progress which it may have otherwise made.

Along with this, it is also seen that there are a lot of unscrupulous means which are often used for the sake of electing representatives. There has to be even more control when it comes to voting and election. When people are clear about their role and they understand that it is with their influence and power that the future of the country can be improved, they are likely to put their power to right use.

How can we truly live up to the tag of democracy?

The change needs to begin with you. There are so many people who complain about how our country has made a mockery of democracy, however what one has to clearly understand is that democracy calls for an equal work by everyone. Remember rather than whining and blaming, you should make it a point to do something yourself.

Create an awareness campaign and try and explain people as to why and how they could bring a change in the nation and contribute towards justifying the tag of India being a true democracy. This awareness and education can be critical in pushing the right waves of change.

Choose leader wisely: It is also important to make sure that we are mindful of who we are choosing as our leaders. You should take the decision on the right parameters rather than being judgmental and getting hoodwinked by superficial factors. The right decision today can safeguard your tomorrow.

So in the end you should understand that democracy is definitely one of the founding pillars for any progressive nation, India is a democracy but we still have a long way to go. Both the individuals and the leaders need to understand the true meaning of democracy and then find the right ways to work around things.

There is no great bond than what ties people to their motherland. So you should make it a point to let the meaning and feeling of democracy seep inside your body and mind and then let it work the magic. Our country deserves our love and respect and definitely the undivided attention as well.

So, let us do our bit for true democracy.

Over a long period of time, India has been ruled by different rulers as well had different forms of government. However, post the British era, India has seen a constant form of government which is governed under the law as laid down under the constitution of India. Democracy is one such important feature of our constitution. Under democracy, the citizens of the country have the right to vote as well the members who in turn form the government.

History of Democracy

The earliest mention of the word democracy has been found in the Greek political texts dating back to 508-507 BC. It has been derived from the word demos which mean common people and Kratos which means strength.

Democracy in Indian Constitution:

Democracy through the constitution of India gives its nationals the privilege to cast a ballot regardless of their rank, caste, creed religion or gender. It has five equitable standards – secular, socialist, republic, sovereign and democratic. Different political organisations represent people at the state and national level. They proliferate about the undertakings achieved in their past residency and furthermore share their tentative arrangements with the general population.

Each citizen of India, over the age of 18 years, has the privilege to cast a vote. The government has always encouraged the individuals to make their choice and cast their vote. Individuals must know everything about the applicants representing the decisions and vote in favour of the most meriting one for good government.

India is known to have an effective democratic framework. In any case, there are some loopholes as well that dampen the spirit of democracy and should be dealt with. In addition to other things, the legislature must work on disposing of poverty, lack of education, communalism, gender discrimination and casteism with the end goal to guarantee democratic system in its obvious sense.

Importance of Democracy in Indian Politics:

Indian democratic government is described by peaceful conjunction of various thoughts and beliefs. There are solid collaboration and rivalry among different political organisations. Since the poll is the path of democratic system, there exist numerous political organisations and every organisation has their own agenda and thoughts.

Good Effects of Democracy:

The democracy has its own share of advantages as well as disadvantages for the common citizens of the country. First, it is instrumental in protecting the rights of the citizens and gives them all the right to choose their government. Additionally, it does not allow a monocratic rule to crop us as all leaders know that need to perform in case they want the people to elect them during the next elections as well. Hence they cannot assume that they have powers forever. Giving all the citizens right to vote provides them with a sense of equality irrespective of their caste, gender, creed or financial status.

The government so formed after democratic elections is usually a stable and responsible form of government. It makes the government socially responsible towards all citizens and the government cannot ignore the plight of its citizens. On the other side, the citizen also behaves in a responsible manner as they know that it is not only their right but their duty as well to choose the government wisely. They are themselves to be blamed if they do not get the government they had wished for it is they who have not rightly exercised their right to vote.

Ill Effects of Democracy:

Democracy, however, leads to misuse of public funds as time and again the elections are conducted at short intervals when we don’t get a stable government and there is infighting among the elected representatives. Also, though considered a duty, the people at times do not exercise their right to vote and a very less voting percentage is seen in many areas which do not give a fair chance to all contestants. Last, but not the least, unfair practices during elections dampen the very spirit of democracy.

A government who strive to be successful cannot overlook the majority of the population that work at fields and the middle class in India. The laws are confined by just thoughts and beliefs of the population. Majority ruling government keeps away from struggle and showdown and makes a peaceful climate for all to live a happy life.

However, at times it has been seen that the majority of the general population of our nation are ignorant and struggle to make their ends meet on day to day basis. Except if the nation is financially and instructively propelled, it will not be right to believe that the electorate will utilize their right to vote to the best advantages of themselves and the nation.

Introduction (Definition) and Concept of Democracy in India:

Democracy in India is the largest in the whole world. Democracy means that the citizens of that country have the power to choose their government. Based on that concept laid by Abraham Lincoln, democracy in India gives rise to a government which is of the people, by the people, and for the people.

Since independence, our constitution has made sure that democracy in India is exercised in its truest form. The greatest of all the powers given to the citizens is their right to vote and maintain the fair establishment of democracy in India.

Not only that, but the system of democracy in India also gives every citizen the right to form a political party and participate in the elections. As you can see, the democracy in India focuses more on its common people than its ruling party.

Importance and Need of Democracy in India:

But why has the democracy in India gained so much hype globally? Well, with the second largest population in the world, we would have been a mess, if it were not for the democracy in India. There are people from so many religions, castes, and creeds that incorporating the system of democracy in India was the only way out to maintain peace in the country.

With so much cultural and religious diversity, democracy in India protects the citizens from unjustified partialities and favoritism. Democracy in India gives equal rights and freedom to every person regardless of their beliefs and standard of living.

The scheduled caste and scheduled tribes in our country had been out casted from the main society since ages. Democracy in India makes sure that they get as many opportunities and support from us as anyone else needs to grow and progress in life.

And to be honest, it’s not just the tribes and castes, in fact, in the absence of democracy in India, there would be so many disparities on gender and income levels. The allegedly weaker and less privileged sections of society including women, transgender, and physically handicapped would be mere space fillers in the country. Democracy in India empowers them with full rights and freedom of speech as well.

Types and Forms of Democracy in India:

Basically, there are two types of Democratic system practiced in the world. The same holds true in the context of our nation also. These two types of democratic systems are direct democracy and indirect democracy.

First, we will talk about direct democracy. In this kind of system, people directly participate in the process of picking their leaders. In fact, they are physically present during the whole process and collectively announce the name of their leader. As you can see, such kind of method is not feasible in the case of a large population. This is the reason why direct democracy in India has disappeared over the years. If at all, it is only followed in small villages and panchayat.

The second type of democracy is indirect democracy. The indirect democracy in India is the most popular alternative to form the government in the country. In this system, instead of getting involved directly, citizens of the nation participate indirectly in the process of electing their leaders. The biggest way to practice indirect democracy in India is by giving the votes during the election.

In the case of indirect democracy, the political parties pick a handful of their worthiest members and help them stand and fight in the elections. The common public gets to vote in favor of their favorite political leader. The one who gets the highest votes becomes the ruling minister in the respective region.

Democracy in India (Reality and Expectations):

Although ideally, all the procedures involved in the indirect democracy in India sound flawless, the ground reality is something else. Incorporating laws, in theory, is much easier than following in practical life. Same is the story with our country.

No matter how much we claim to have a fair and transparent system of democracy in India, we must admit that there are plenty of loopholes in reality. For instance, voting is done through Electronic voting machines (EVM).

The EVM topic has been the talk of the town for a while in India, especially during the recent elections. Allegedly, the ruling parties have been accused of interfering with the machines which led to a huge scam. In other words, it can be called nothing but a great dishonor to the indirect democracy in India.

Apart from that, we have a long history of violence and terror in the common public spread by the political parties, right before the major elections. This kind of shameful threating is specifically true in case of villages and small towns where people are made to vote at gunpoint for a particular party.

Moreover, democracy in India gives everyone equal rights to participate in the elections and in the process of voting. However, these right have been hampered on many occasions. A few years ago, women candidates in the political parties were not taken seriously. Even if they fought in the elections and won, their decision making was mainly carried out either by their husbands or by other political leaders in the same party.

The road to democracy in India has been uneven and tricky for the trans-genders as well. It wasn’t much before when they were crashed and killed just for trying to attempt and enter the political arena of the country.

That being said, things are changing at a considerable pace and for the better. There are more openness and acceptance in terms of people from other genders and age groups. The Election Commission is following strict measures to ensure a clean and fair system of democracy in India.

Democracy , Democracy in India , Political System

Get FREE Work-at-Home Job Leads Delivered Weekly!

Join more than 50,000 subscribers receiving regular updates! Plus, get a FREE copy of How to Make Money Blogging!

Message from Sophia!

Like this post? Don’t forget to share it!

Here are a few recommended articles for you to read next:

- Which is More Important in Life: Love or Money | Essay

- Essay on My School

- Essay on Solar Energy

- Essay on Biodiversity

No comments yet.

Leave a reply click here to cancel reply..

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Billionaires

- Donald Trump

- Warren Buffett

- Email Address

- Free Stock Photos

- Keyword Research Tools

- URL Shortener Tools

- WordPress Theme

Book Summaries

- How To Win Friends

- Rich Dad Poor Dad

- The Code of the Extraordinary Mind

- The Luck Factor

- The Millionaire Fastlane

- The ONE Thing

- Think and Grow Rich

- 100 Million Dollar Business

- Business Ideas

Digital Marketing

- Mobile Addiction

- Social Media Addiction

- Computer Addiction

- Drug Addiction

- Internet Addiction

- TV Addiction

- Healthy Habits

- Morning Rituals

- Wake up Early

- Cholesterol

- Reducing Cholesterol

- Fat Loss Diet Plan

- Reducing Hair Fall

- Sleep Apnea

- Weight Loss

Internet Marketing

- Email Marketing

Law of Attraction

- Subconscious Mind

- Vision Board

- Visualization

Law of Vibration

- Professional Life

Motivational Speakers

- Bob Proctor

- Robert Kiyosaki

- Vivek Bindra

- Inner Peace

Productivity

- Not To-do List

- Project Management Software

- Negative Energies

Relationship

- Getting Back Your Ex

Self-help 21 and 14 Days Course

Self-improvement.

- Body Language

- Complainers

- Emotional Intelligence

- Personality

Social Media

- Project Management

- Anik Singal

- Baba Ramdev

- Dwayne Johnson

- Jackie Chan

- Leonardo DiCaprio

- Narendra Modi

- Nikola Tesla

- Sachin Tendulkar

- Sandeep Maheshwari

- Shaqir Hussyin

Website Development

Wisdom post, worlds most.

- Expensive Cars

Our Portals: Gulf Canada USA Italy Gulf UK

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

Talk to our experts

1800-120-456-456

- Democracy Essay for Students in English

Essay on Democracy

Introduction.

Democracy is mainly a Greek word which means people and their rules, here peoples have the to select their own government as per their choice. Greece was the first democratic country in the world. India is a democratic country where people select their government of their own choice, also people have the rights to do the work of their choice. There are two types of democracy: direct and representative and hybrid or semi-direct democracy. There are many decisions which are made under democracies. People enjoy few rights which are very essential for human beings to live happily.

Our country has the largest democracy. In a democracy, each person has equal rights to fight for development. After the independence, India has adopted democracy, where the people vote those who are above 18 years of age, but these votes do not vary by any caste; people from every caste have equal rights to select their government. Democracy, also called as a rule of the majority, means whatever the majority of people decide, it has to be followed or implemented, the representative winning with the most number of votes will have the power. We can say the place where literacy people are more there shows the success of the democracy even lack of consciousness is also dangerous in a democracy. Democracy is associated with higher human accumulation and higher economic freedom. Democracy is closely tied with the economic source of growth like education and quality of life as well as health care. The constituent assembly in India was adopted by Dr B.R. Ambedkar on 26 th November 1949 and became sovereign democratic after its constitution came into effect on 26 January 1950.

What are the Challenges:

There are many challenges for democracy like- corruption here, many political leaders and officers who don’t do work with integrity everywhere they demand bribes, resulting in the lack of trust on the citizens which affects the country very badly. Anti-social elements- which are seen during elections where people are given bribes and they are forced to vote for a particular candidate. Caste and community- where a large number of people give importance to their caste and community, therefore, the political party also selects the candidate on the majority caste. We see wherever the particular caste people win the elections whether they do good for the society or not, and in some cases, good leaders lose because of less count of the vote.

India is considered to be the largest democracy around the globe, with a population of 1.3 billion. Even though being the biggest democratic nation, India still has a long way to becoming the best democratic system. The caste system still prevails in some parts, which hurts the socialist principle of democracy. Communalism is on the rise throughout the globe and also in India, which interferes with the secular principle of democracy. All these differences need to be set aside to ensure a thriving democracy.

Principles of Democracy:

There are mainly five principles like- republic, socialist, sovereign, democratic and secular, with all these quality political parties will contest for elections. There will be many bribes given to the needy person who require food, money, shelter and ask them to vote whom they want. But we can say that democracy in India is still better than the other countries.

Basically, any country needs democracy for development and better functioning of the government. In some countries, freedom of political expression, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, are considered to ensure that voters are well informed, enabling them to vote according to their own interests.

Let us Discuss These Five Principles in Further Detail

Sovereign: In short, being sovereign or sovereignty means the independent authority of a state. The country has the authority to make all the decisions whether it be on internal issues or external issues, without the interference of any third party.

Socialist: Being socialist means the country (and the Govt.), always works for the welfare of the people, who live in that country. There should be many bribes offered to the needy person, basic requirements of them should be fulfilled by any means. No one should starve in such a country.

Secular: There will be no such thing as a state religion, the country does not make any bias on the basis of religion. Every religion must be the same in front of the law, no discrimination on the basis of someone’s religion is tolerated. Everyone is allowed to practice and propagate any religion, they can change their religion at any time.

Republic: In a republic form of Government, the head of the state is elected, directly or indirectly by the people and is not a hereditary monarch. This elected head is also there for a fixed tenure. In India, the head of the state is the president, who is indirectly elected and has a fixed term of office (5 years).

Democratic: By a democratic form of government, means the country’s government is elected by the people via the process of voting. All the adult citizens in the country have the right to vote to elect the government they want, only if they meet a certain age limit of voting.

Merits of Democracy:

better government forms because it is more accountable and in the interest of the people.

improves the quality of decision making and enhances the dignity of the citizens.

provide a method to deal with differences and conflicts.

A democratic system of government is a form of government in which supreme power is vested in the people and exercised by them directly or indirectly through a system of representation usually involving periodic free elections. It permits citizens to participate in making laws and public policies by choosing their leaders, therefore citizens should be educated so that they can select the right candidate for the ruling government. Also, there are some concerns regarding democracy- leaders always keep changing in democracy with the interest of citizens and on the count of votes which leads to instability. It is all about political competition and power, no scope for morality.

Factors Affect Democracy:

capital and civil society

economic development

modernization

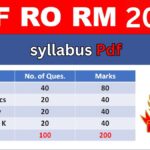

Norway and Iceland are the best democratic countries in the world. India is standing at fifty-one position.

India is a parliamentary democratic republic where the President is head of the state and Prime minister is head of the government. The guiding principles of democracy such as protected rights and freedoms, free and fair elections, accountability and transparency of government officials, citizens have a responsibility to uphold and support their principles. Democracy was first practised in the 6 th century BCE, in the city-state of Athens. One basic principle of democracy is that people are the source of all the political power, in a democracy people rule themselves and also respect given to diverse groups of citizens, so democracy is required to select the government of their own interest and make the nation developed by electing good leaders.

FAQs on Democracy Essay for Students in English

1. What are the Features of Democracy?

Features of Democracy are as follows

Equality: Democracy provides equal rights to everyone, regardless of their gender, caste, colour, religion or creed.

Individual Freedom: Everybody has the right to do anything they want until it does not affect another person’s liberty.

Majority Rules: In a democracy, things are decided by the majority rule, if the majority agrees to something, it will be done.

Free Election: Everyone has the right to vote or to become a candidate to fight the elections.

2. Define Democracy?

Democracy means where people have the right to choose the rulers and also people have freedom to express views, freedom to organise and freedom to protest. Protesting and showing Dissent is a major part of a healthy democracy. Democracy is the most successful and popular form of government throughout the globe.

Democracy holds a special place in India, also India is still the largest democracy in existence around the world.

3. What are the Benefits of Democracy?

Let us discuss some of the benefits received by the use of democracy to form a government. Benefits of democracy are:

It is more accountable

Improves the quality of decision as the decision is taken after a long time of discussion and consultation.

It provides a better method to deal with differences and conflicts.

It safeguards the fundamental rights of people and brings a sense of equality and freedom.

It works for the welfare of both the people and the state.

4. Which country is the largest democracy in the World?

India is considered the largest democracy, all around the world. India decided to have a democratic Govt. from the very first day of its independence after the rule of the British. In India, everyone above the age of 18 years can go to vote to select the Government, without any kind of discrimination on the basis of caste, colour, religion, gender or more. But India, even being the largest democracy, still has a long way to become perfect.

5. Write about the five principles of Democracy?

There are five key principles that are followed in a democracy. These Five Principles of Democracy of India are - secular, sovereign, republic, socialist, and democratic. These five principles have to be respected by every political party, participating in the general elections in India. The party which got the most votes forms the government which represents the democratic principle. No discrimination is done on the basis of religion which represents the secular nature of democracy. The govt. formed after the election has to work for the welfare of common people which shows socialism in play.

Democracy Essay

Democracy is derived from the Greek word demos or people. It is defined as a government in which the supreme power is vested in the people. Democracy is exercised directly by the people; in large societies, it is by the people through their elected agents. In the phrase of President Abraham Lincoln, democracy is the “Government of the people, by the people, and for the people.” There are various democratic countries, but India has the largest democracy in the world. This Democracy Essay will help you know all about India’s democracy. Students can also get a list of CBSE Essays on different topics to boost their essay-writing skills.

500+ Words Democracy Essay

India is a very large country full of diversities – linguistically, culturally and religiously. At the time of independence, it was economically underdeveloped. There were enormous regional disparities, widespread poverty, illiteracy, unemployment, and a shortage of almost all public welfare means. Since independence, India has been functioning as a responsible democracy. The same has been appreciated by the international community. It has successfully adapted to challenging situations. There have been free and fair periodic elections for all political offices, from the panchayats to the President. There has been a smooth transfer of political power from one political party or set of political parties to others, both at national and state levels, on many occasions.

India: A Democratic Country

Democracy is of two, i.e. direct and representative. In a direct democracy, all citizens, without the intermediary of elected or appointed officials, can participate in making public decisions. Such a system is only practical with relatively small numbers of people in a community organisation or tribal council. Whereas in representative democracy, every citizen has the right to vote for their representative. People elect their representatives to all levels, from Panchayats, Municipal Boards, State Assemblies and Parliament. In India, we have a representative democracy.

Democracy is a form of government in which rulers elected by the people take all the major decisions. Elections offer a choice and fair opportunity to the people to change the current rulers. This choice and opportunity are available to all people on an equal basis. The exercise of this choice leads to a government limited by basic rules of the constitution and citizens’ rights.

Democracy is the Best Form of Government

A democratic government is a better government because it is a more accountable form of government. Democracy provides a method to deal with differences and conflicts. Thus, democracy improves the quality of decision-making. The advantage of a democracy is that mistakes cannot be hidden for long. There is a space for public discussion, and there is room for correction. Either the rulers have to change their decisions, or the rulers can be changed. Democracy offers better chances of a good decision. It respects people’s own wishes and allows different kinds of people to live together. Even when it fails to do some of these things, it allows a way of correcting its mistakes and offers more dignity to all citizens. That is why democracy is considered the best form of government.

Students must have found this “Democracy Essay” useful for improving their essay writing skills. They can get the study material and the latest update on CBSE/ICSE/State Board/Competitive Exams, at BYJU’S.

| CBSE Related Links | |

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

Indian Democracy: A Reflection of Aspirations and Achievements | Essay Writing for UPSC by Vikash Ranjan Sir | Triumph ias

Table of Contents

Indian Democracy: A Voyage of Aspirations and Triumphs

(relevant for essay writing for upsc civil services examination).

Indian Democracy is a vibrant, complex tapestry that reflects the diverse aspirations of its people. This post explores the achievements that have marked this democratic journey and the aspirations that continue to shape its path.

Aspirations: A Beacon for Democracy

Indian Democracy’s aspirations are a guiding light, reflecting the dreams of inclusivity, transparency, and sustainable development.

Achievements: Milestones Along the Way

From universal adult suffrage to remarkable economic growth, Indian Democracy’s achievements are many. They stand as testament to the nation’s commitment to its democratic principles.

Challenges: The Road Ahead

Despite its triumphs, Indian Democracy faces challenges. Political, social, and economic disparities continue to be areas of concern.

Conclusion: Democracy’s Ongoing Journey

Indian Democracy is an evolving journey of aspirations and achievements. Embracing its triumphs and addressing its challenges, India marches forward in its democratic voyage.

To master these intricacies and fare well in the Sociology Optional Syllabus , aspiring sociologists might benefit from guidance by the Best Sociology Optional Teacher and participation in the Best Sociology Optional Coaching . These avenues provide comprehensive assistance, ensuring a solid understanding of sociology’s diverse methodologies and techniques

Indian Democracy, Aspirations, Achievements, Inclusivity, Transparency, Sustainable Development, Universal Adult Franchise, Economic Progress, Political Polarization, Social Inequalities.

Sociology Optional Syllabus Course Commencement Information

- Enrolment is limited to a maximum of 250 Seats.

- Course Timings: Evening Batch

- Course Duration: 4.5 Months

- Class Schedule: Monday to Saturday

- Batch Starts from: Admission open for online batch

Book Your Seat Fast Book Your Seat Fast

We would like to hear from you. Please send us a message by filling out the form below and we will get back with you shortly.

Instructional Format:

- Each class session is scheduled for a duration of two hours.

- At the conclusion of each lecture, an assignment will be distributed by Vikash Ranjan Sir for Paper-I & Paper-II coverage.

Study Material:

- A set of printed booklets will be provided for each topic. These materials are succinct, thoroughly updated, and tailored for examination preparation.

- A compilation of previous years’ question papers (spanning the last 27 years) will be supplied for answer writing practice.

- Access to PDF versions of toppers’ answer booklets will be available on our website.

- Post-course, you will receive two practice workbooks containing a total of 10 sets of mock test papers based on the UPSC format for self-assessment.

Additional Provisions:

- In the event of missed classes, video lectures will be temporarily available on the online portal for reference.

- Daily one-on-one doubt resolution sessions with Vikash Ranjan Sir will be organized post-class.

Syllabus of Sociology Optional

FUNDAMENTALS OF SOCIOLOGY

- Modernity and social changes in Europe and emergence of sociology.

- Scope of the subject and comparison with other social sciences.

- Sociology and common sense.

- Science, scientific method and critique.

- Major theoretical strands of research methodology.

- Positivism and its critique.

- Fact value and objectivity.

- Non- positivist methodologies.

- Qualitative and quantitative methods.

- Techniques of data collection.

- Variables, sampling, hypothesis, reliability and validity.

- Karl Marx- Historical materialism, mode of production, alienation, class struggle.

- Emile Durkheim- Division of labour, social fact, suicide, religion and society.

- Max Weber- Social action, ideal types, authority, bureaucracy, protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism.

- Talcott Parsons- Social system, pattern variables.

- Robert K. Merton- Latent and manifest functions, conformity and deviance, reference groups.

- Mead – Self and identity.

- Concepts- equality, inequality, hierarchy, exclusion, poverty and deprivation.

- Theories of social stratification- Structural functionalist theory, Marxist theory, Weberian theory.

- Dimensions – Social stratification of class, status groups, gender, ethnicity and race.

- Social mobility- open and closed systems, types of mobility, sources and causes of mobility.

- Social organization of work in different types of society- slave society, feudal society, industrial /capitalist society

- Formal and informal organization of work.

- Labour and society.

- Sociological theories of power.

- Power elite, bureaucracy, pressure groups, and political parties.

- Nation, state, citizenship, democracy, civil society, ideology.

- Protest, agitation, social movements, collective action, revolution.

- Sociological theories of religion.

- Types of religious practices: animism, monism, pluralism, sects, cults.

- Religion in modern society: religion and science, secularization, religious revivalism, fundamentalism.

- Family, household, marriage.

- Types and forms of family.

- Lineage and descent.

- Patriarchy and sexual division of labour.

- Contemporary trends.

- Sociological theories of social change.

- Development and dependency.

- Agents of social change.

- Education and social change.

- Science, technology and social change.

INDIAN SOCIETY: STRUCTURE AND CHANGE

Introducing indian society.

- Indology (GS. Ghurye).

- Structural functionalism (M N Srinivas).

- Marxist sociology (A R Desai).

- Social background of Indian nationalism.

- Modernization of Indian tradition.

- Protests and movements during the colonial period.

- Social reforms.

SOCIAL STRUCTURE

- The idea of Indian village and village studies.

- Agrarian social structure – evolution of land tenure system, land reforms.

- Perspectives on the study of caste systems: GS Ghurye, M N Srinivas, Louis Dumont, Andre Beteille.

- Features of caste system.

- Untouchability – forms and perspectives.

- Definitional problems.

- Geographical spread.

- Colonial policies and tribes.

- Issues of integration and autonomy.

- Social Classes in India:

- Agrarian class structure.

- Industrial class structure.

- Middle classes in India.

- Lineage and descent in India.

- Types of kinship systems.

- Family and marriage in India.

- Household dimensions of the family.

- Patriarchy, entitlements and sexual division of labour

- Religious communities in India.

- Problems of religious minorities.

SOCIAL CHANGES IN INDIA

- Idea of development planning and mixed economy

- Constitution, law and social change.

- Programmes of rural development, Community Development Programme, cooperatives,poverty alleviation schemes

- Green revolution and social change.

- Changing modes of production in Indian agriculture.

- Problems of rural labour, bondage, migration.

3. Industrialization and Urbanisation in India:

- Evolution of modern industry in India.

- Growth of urban settlements in India.

- Working class: structure, growth, class mobilization.

- Informal sector, child labour

- Slums and deprivation in urban areas.

4. Politics and Society:

- Nation, democracy and citizenship.

- Political parties, pressure groups , social and political elite

- Regionalism and decentralization of power.

- Secularization

5. Social Movements in Modern India:

- Peasants and farmers movements.

- Women’s movement.

- Backward classes & Dalit movement.

- Environmental movements.

- Ethnicity and Identity movements.

6. Population Dynamics:

- Population size, growth, composition and distribution

- Components of population growth: birth, death, migration.

- Population policy and family planning.

- Emerging issues: ageing, sex ratios, child and infant mortality, reproductive health.

7. Challenges of Social Transformation:

- Crisis of development: displacement, environmental problems and sustainability

- Poverty, deprivation and inequalities.

- Violence against women.

- Caste conflicts.

- Ethnic conflicts, communalism, religious revivalism.

- Illiteracy and disparities in education.

Mr. Vikash Ranjan, arguably the Best Sociology Optional Teacher , has emerged as a versatile genius in teaching and writing books on Sociology & General Studies. His approach to the Sociology Optional Syllabus / Sociology Syllabus is remarkable, and his Sociological Themes and Perspectives are excellent. His teaching aptitude is Simple, Easy and Exam Focused. He is often chosen as the Best Sociology Teacher for Sociology Optional UPSC aspirants.

About Triumph IAS

Innovating Knowledge, Inspiring Success We, at Triumph IAS , pride ourselves on being the best sociology optional coaching platform. We believe that each Individual Aspirant is unique and requires Individual Guidance and Care, hence the need for the Best Sociology Teacher . We prepare students keeping in mind his or her strength and weakness, paying particular attention to the Sociology Optional Syllabus / Sociology Syllabus , which forms a significant part of our Sociology Foundation Course .

Course Features

Every day, the Best Sociology Optional Teacher spends 2 hours with the students, covering each aspect of the Sociology Optional Syllabus / Sociology Syllabus and the Sociology Course . Students are given assignments related to the Topic based on Previous Year Question to ensure they’re ready for the Sociology Optional UPSC examination.

Regular one-on-one interaction & individual counseling for stress management and refinement of strategy for Exam by Vikash Ranjan Sir , the Best Sociology Teacher , is part of the package. We specialize in sociology optional coaching and are hence fully equipped to guide you to your dream space in the civil service final list.

Specialist Guidance of Vikash Ranjan Sir

The Best Sociology Teacher helps students to get a complete conceptual understanding of each and every topic of the Sociology Optional Syllabus / Sociology Syllabus , enabling them to attempt any of the questions, be direct or applied, ensuring 300+ Marks in Sociology Optional .

Classrooms Interaction & Participatory Discussion

The Best Sociology Teacher, Vikash Sir , ensures that there’s explanation & DISCUSSION on every topic of the Sociology Optional Syllabus / Sociology Syllabus in the class. The emphasis is not just on teaching but also on understanding, which is why we are known as the Best Sociology Optional Coaching institution.

Preparatory-Study Support

Online Support System (Oss)

Get access to an online forum for value addition study material, journals, and articles relevant to Sociology on www.triumphias.com . Ask preparation related queries directly to the Best Sociology Teacher , Vikash Sir, via mail or WhatsApp.

Strategic Classroom Preparation

Comprehensive Study Material

We provide printed booklets of concise, well-researched, exam-ready study material for every unit of the Sociology Optional Syllabus / Sociology Syllabus , making us the Best Sociology Optional Coaching platform.

Why Vikash Ranjan’s Classes for Sociology?

Proper guidance and assistance are required to learn the skill of interlinking current happenings with the conventional topics. VIKASH RANJAN SIR at TRIUMPH IAS guides students according to the Recent Trends of UPSC, making him the Best Sociology Teacher for Sociology Optional UPSC.

At Triumph IAS, the Best Sociology Optional Coaching platform, we not only provide the best study material and applied classes for Sociology for IAS but also conduct regular assignments and class tests to assess candidates’ writing skills and understanding of the subject.

Choose T he Best Sociology Optional Teacher for IAS Preparation?

At the beginning of the journey for Civil Services Examination preparation, many students face a pivotal decision – selecting their optional subject. Questions such as “ which optional subject is the best? ” and “ which optional subject is the most scoring? ” frequently come to mind. Choosing the right optional subject, like choosing the best sociology optional teacher , is a subjective yet vital step that requires a thoughtful decision based on facts. A misstep in this crucial decision can indeed prove disastrous.

Ever since the exam pattern was revamped in 2013, the UPSC has eliminated the need for a second optional subject. Now, candidates have to choose only one optional subject for the UPSC Mains , which has two papers of 250 marks each. One of the compelling choices for many has been the sociology optional. However, it’s strongly advised to decide on your optional subject for mains well ahead of time to get sufficient time to complete the syllabus. After all, most students score similarly in General Studies Papers; it’s the score in the optional subject & essay that contributes significantly to the final selection.

“ A sound strategy does not rely solely on the popular Opinion of toppers or famous YouTubers cum teachers. ”

It requires understanding one’s ability, interest, and the relevance of the subject, not just for the exam but also for life in general. Hence, when selecting the best sociology teacher, one must consider the usefulness of sociology optional coaching in General Studies, Essay, and Personality Test.

The choice of the optional subject should be based on objective criteria, such as the nature, scope, and size of the syllabus, uniformity and stability in the question pattern, relevance of the syllabic content in daily life in society, and the availability of study material and guidance. For example, choosing the best sociology optional coaching can ensure access to top-quality study materials and experienced teachers. Always remember, the approach of the UPSC optional subject differs from your academic studies of subjects. Therefore, before settling for sociology optional , you need to analyze the syllabus, previous years’ pattern, subject requirements (be it ideal, visionary, numerical, conceptual theoretical), and your comfort level with the subject.

This decision marks a critical point in your UPSC – CSE journey , potentially determining your success in a career in IAS/Civil Services. Therefore, it’s crucial to choose wisely, whether it’s the optional subject or the best sociology optional teacher . Always base your decision on accurate facts, and never let your emotional biases guide your choices. After all, the search for the best sociology optional coaching is about finding the perfect fit for your unique academic needs and aspirations.

To master these intricacies and fare well in the Sociology Optional Syllabus , aspiring sociologists might benefit from guidance by the Best Sociology Optional Teacher and participation in the Best Sociology Optional Coaching . These avenues provide comprehensive assistance, ensuring a solid understanding of sociology’s diverse methodologies and techniques. Sociology, Social theory, Best Sociology Optional Teacher, Best Sociology Optional Coaching, Sociology Optional Syllabus. Best Sociology Optional Teacher, Sociology Syllabus, Sociology Optional, Sociology Optional Coaching, Best Sociology Optional Coaching, Best Sociology Teacher, Sociology Course, Sociology Teacher, Sociology Foundation, Sociology Foundation Course, Sociology Optional UPSC, Sociology for IAS,

Follow us :

🔎 https://www.instagram.com/triumphias

🔎 www.triumphias.com

🔎https://www.youtube.com/c/TriumphIAS

https://t.me/VikashRanjanSociology

Find More Blogs

|

|

|

|

|

| Modernity and social changes in Europe |

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Skip to main content

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

A Plus Topper

Improve your Grades

Essay on Democracy in India | Democracy in India Essay for Students and Children in English

February 14, 2024 by Prasanna

Essay on Democracy in India: Of the people, by the people and for the people coined by the great president of the United States of America, Abraham Lincoln represents the core values and principles of democracy. Democracy might not be the best form of governance in the world, but one thing is for sure, there is no alternative for democracy. Sure democracy has its own loopholes and problems, but at the core of this system, it values the qualities of equality and fraternity in society. The alternatives for democracy is authoritarianism, dictatorship or fascism, which at its core, does not guarantee the fundamental freedom and humanitarian values to people.

You can read more Essay Writing about articles, events, people, sports, technology many more.

Long and Short Essays on Democracy in India in English for Students and Kids

In this article, we have provided a long as well as short essay on democracy in India which will be of use for school students in their essay writing, tests, assignments, and project work.