Last updated 27/06/24: Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > Bilingualism: Language and Cognition

- > Volume 21 Issue 5

- > Critical periods for language acquisition: New insights...

Article contents

Critical periods for language acquisition: new insights with particular reference to bilingualism research.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 October 2018

One of the best-known claims from language acquisition research is that the capacity to learn languages is constrained by maturational changes, with particular time windows (aka ‘critical’ or ‘sensitive’ periods) better suited for language learning than others. Evidence for the critical period hypothesis (CPH) comes from a number of sources demonstrating that age is a crucial predictor for language attainment and that the capacity to learn language diminishes with age. To take just one example, a recent study by Hartshorne, Tenenbaum and Pinker ( 2018 ) identified a ‘sharply-defined critical period’ for grammar learning, and a steady decline thereafter, based on a very large dataset (of 2/3 million English Speakers) that allowed them to disentangle critical-period effects from non-age factors (e.g., amount of experience) affecting grammatical performance. Other evidence for the CPH comes from research with individuals who were deprived of linguistic input during the critical period (Curtiss, 1977 ) and were consequently unable to acquire language properly. Moreover, neurobiological research has shown that critical periods affect the neurological substrate for language processing, specifically for grammar (Wartenburger, Heekeren, Abutalebi, Cappa, Villringer & Perani, 2003 ).

One of the best-known claims from language acquisition research is that the capacity to learn languages is constrained by maturational changes, with particular time windows (aka ‘critical’ or ‘sensitive’ periods) better suited for language learning than others. Evidence for the critical period hypothesis (CPH) comes from a number of sources demonstrating that age is a crucial predictor for language attainment and that the capacity to learn language diminishes with age. To take just one example, a recent study by Hartshorne, Tenenbaum and Pinker ( Reference Hartshorne, Tenenbaum and Pinker 2018 ) identified a ‘sharply-defined critical period’ for grammar learning, and a steady decline thereafter, based on a very large dataset (of 2/3 million English Speakers) that allowed them to disentangle critical-period effects from non-age factors (e.g., amount of experience) affecting grammatical performance. Other evidence for the CPH comes from research with individuals who were deprived of linguistic input during the critical period (Curtiss, Reference Curtiss 1977 ) and were consequently unable to acquire language properly. Moreover, neurobiological research has shown that critical periods affect the neurological substrate for language processing, specifically for grammar (Wartenburger, Heekeren, Abutalebi, Cappa, Villringer & Perani, Reference Wartenburger, Heekeren, Abutalebi, Cappa, Villringer and Perani 2003 ).

In bilingualism research, the CPH has received a somewhat mixed response, with some researchers plainly denying that critical periods constrain language acquisition (e.g., Bialystok & Kroll, Reference Bialystok and Kroll 2018 ) and others having ‘little doubt’ that language acquisition is subject to critical period effects (Meisel, Reference Meisel, Boeckx and Grohmann 2013 : 71). It is true that early onsets of bilingual first language acquisition (during childhood) do indeed typically yield better linguistic skills than later ones, in line with the CPH. On the other hand, individuals with early onsets of acquisition of a particular language are typically also younger when they learn that language and have a longer time of exposure than individuals with a later onset of acquisition. Given these potentially confounding factors, supposed critical period effects might be open to alternative interpretations.

Our keynote article (Mayberry & Kluender, Reference Mayberry and Kluender 2018a ) offers a new challenging perspective on the CPH by relying mainly on studies of the acquisition of sign languages, the specific learning circumstances of which offer a unique opportunity to disentangle genuine critical-period effects from non-age factors affecting linguistic performance. Mayberry and Kluender specifically compare linguistic outcomes of the acquisition of sign languages in post-childhood L2 learners with that of post-childhood L1 learners. Their most striking finding is that late L1 learners perform significantly worse in morphology, syntax and phonology than late L2 learners. This contrast appears to be unrelated to non-linguistic cognitive or motivational factors but is attributed instead to very late L1 learners having developed an incomplete brain/language system during childhood brain maturation. L2 learners, on the other hand, have already established a fully-fledged brain/language system during this period. Mayberry and Kluender conclude from the more substantial age-of-acquisition effect in adult L1 than in adult L2 learners that there is a critical period for the acquisition of a first language only, whereas L2 development is affected by other factors.

Fifteen commentaries, most of which were specifically selected to represent different views on the CPH from the perspective of bilingualism research, accompany the keynote article. Many commentators praise the keynote article for drawing attention to the acquisition of sign languages, which through comparisons of late L1 and L2 learners contributes important insights for our understanding of a critical or sensitive period for the acquisition of language. Woll ( Reference Woll 2018 ) reports an additional case of late L1 acquisition of (British) Sign language, a deaf person with very late exposure to L1, who exhibits severe difficulties with syntax and phonology despite intact cognitive skills, in line with the findings reported in the keynote article. On the other hand, Mayberry and Kluender's ( Reference Mayberry and Kluender 2018 a) claim that maturational factors (viz. critical or sensitive periods) do not affect L2 acquisition has received a less positive response from many commentators. Several commentators point to evidence indicating age-of-acquisition effects on L2 speakers’ linguistic skill and to models of L2 acquisition that account for the role of maturational constraints implicated by the CPH (Abrahamsson, Reference Abrahamsson 2018 ; DeKeyser, Reference DeKeyser 2018 ; Hyltenstam, Reference Hyltenstam 2018 ; Long & Granena, Reference Long and Granena 2018 ; Newport, Reference Newport 2018 ; Reh, Arredondo & Werker, Reference Reh, Arredondo and Werker 2018 ; Veríssimo, Reference Veríssimo 2018 ). As opposed to these researchers, some commentators question the role of critical or sensitive periods for language not only for L2 but also for L1 acquisition (Bialystok & Kroll, Reference Bialystok and Kroll 2018 ; Flege, Reference Flege 2018 ). Other commentators highlight specific limitations of the proposed account and of the data presented in its support. Birdsong and Quinto-Pozos ( Reference Birdsong and Quinto-Pozos 2018 ) note that what is missing from Mayberry and Kluender's comparison of late L1 vs. L2 signers is a role for bilingualism, arguing that comparing bilinguals with monolinguals will always reveal differences regardless of the age of L2 acquisition. Emmorey ( Reference Emmorey 2018 ) questions the keynote article's claim that if L2 outcomes were fully under the control of a critical period, they should not be as variable as they are and affected by cognitive or motivational factors, by pointing out that this variability does indeed extend to L1 learners. Lillo-Martin ( Reference Lillo-Martin 2018 ) points out that there may be domain-specific splits with respect to critical periods, with different age cutoffs for different linguistic phenomena, a possibility that is not considered in any detail in the keynote article (see also Veríssimo, Reference Veríssimo 2018 ). Finally, Bley-Vroman ( 2018 ) and White ( Reference White 2018 ) use the evidence presented in our keynote article to address the question of whether or not domain-specific learning mechanisms are available to adult language learners; see also Clahsen & Muysken ( Reference Clahsen and Muysken 1986 ; Reference Clahsen and Muysken 1989 ).

In their response, Mayberry and Kluender ( Reference Mayberry and Kluender 2018b ) highlight points of agreement, clear up misunderstandings, admit current limitations of their proposal, and welcome suggestions for future research. Most importantly, however, in the face of the commentaries Mayberry and Kluender ( Reference Mayberry and Kluender 2018b ) modify their original claim of a critical period for L1 acquisition only. They now sympathize with the idea that there are critical periods for both L1 and L2 acquisition, but with less severe AoA effects on late L2 acquisition than on delayed L1 acquisition, due to L2 speakers having learnt another language early in life; see Hyltenstam ( Reference Hyltenstam 2018 ) and Newport ( Reference Newport 2018 ).

We hope our readers will enjoy the keynote article together with the commentaries and the authors’ response as well as the interesting regular research articles and research notes presented in the current issue.

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

- Google Scholar

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Volume 21, Issue 5

- JUBIN ABUTALEBI (a1) and HARALD CLAHSEN (a2)

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728918001025

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Key Concepts

- The View From Here

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish?

- About ELT Journal

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Age and the critical period hypothesis

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Christian Abello-Contesse, Age and the critical period hypothesis, ELT Journal , Volume 63, Issue 2, April 2009, Pages 170–172, https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccn072

- Permissions Icon Permissions

In the field of second language acquisition (SLA), how specific aspects of learning a non-native language (L2) may be affected by when the process begins is referred to as the ‘age factor’. Because of the way age intersects with a range of social, affective, educational, and experiential variables, clarifying its relationship with learning rate and/or success is a major challenge.

There is a popular belief that children as L2 learners are ‘superior’ to adults ( Scovel 2000 ), that is, the younger the learner, the quicker the learning process and the better the outcomes. Nevertheless, a closer examination of the ways in which age combines with other variables reveals a more complex picture, with both favourable and unfavourable age-related differences being associated with early- and late-starting L2 learners ( Johnstone 2002 ).

The ‘critical period hypothesis’ (CPH) is a particularly relevant case in point. This is the claim that there is, indeed, an optimal period for language acquisition, ending at puberty. However, in its original formulation ( Lenneberg 1967 ), evidence for its existence was based on the relearning of impaired L1 skills, rather than the learning of a second language under normal circumstances.

Furthermore, although the age factor is an uncontroversial research variable extending from birth to death ( Cook 1995 ), and the CPH is a narrowly focused proposal subject to recurrent debate, ironically, it is the latter that tends to dominate SLA discussions ( García Lecumberri and Gallardo 2003 ), resulting in a number of competing conceptualizations. Thus, in the current literature on the subject ( Bialystok 1997 ; Richards and Schmidt 2002 ; Abello-Contesse et al. 2006), references can be found to (i) multiple critical periods (each based on a specific language component, such as age six for L2 phonology), (ii) the non-existence of one or more critical periods for L2 versus L1 acquisition, (iii) a ‘sensitive’ yet not ‘critical’ period, and (iv) a gradual and continual decline from childhood to adulthood.

It therefore needs to be recognized that there is a marked contrast between the CPH as an issue of continuing dispute in SLA, on the one hand, and, on the other, the popular view that it is an invariable ‘law’, equally applicable to any L2 acquisition context or situation. In fact, research indicates that age effects of all kinds depend largely on the actual opportunities for learning which are available within overall contexts of L2 acquisition and particular learning situations, notably the extent to which initial exposure is substantial and sustained ( Lightbown 2000 ).

Thus, most classroom-based studies have shown not only a lack of direct correlation between an earlier start and more successful/rapid L2 development but also a strong tendency for older children and teenagers to be more efficient learners. For example, in research conducted in the context of conventional school programmes, Cenoz (2003) and Muñoz (2006) have shown that learners whose exposure to the L2 began at age 11 consistently displayed higher levels of proficiency than those for whom it began at 4 or 8. Furthermore, comparable limitations have been reported for young learners in school settings involving innovative, immersion-type programmes, where exposure to the target language is significantly increased through subject-matter teaching in the L2 ( Genesee 1992 ; Abello-Contesse 2006 ). In sum, as Harley and Wang (1997) have argued, more mature learners are usually capable of making faster initial progress in acquiring the grammatical and lexical components of an L2 due to their higher level of cognitive development and greater analytical abilities.

In terms of language pedagogy, it can therefore be concluded that (i) there is no single ‘magic’ age for L2 learning, (ii) both older and younger learners are able to achieve advanced levels of proficiency in an L2, and (iii) the general and specific characteristics of the learning environment are also likely to be variables of equal or greater importance.

Google Scholar

Google Preview

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| November 2016 | 31 |

| December 2016 | 27 |

| January 2017 | 31 |

| February 2017 | 151 |

| March 2017 | 238 |

| April 2017 | 217 |

| May 2017 | 355 |

| June 2017 | 190 |

| July 2017 | 91 |

| August 2017 | 126 |

| September 2017 | 264 |

| October 2017 | 449 |

| November 2017 | 743 |

| December 2017 | 2,636 |

| January 2018 | 2,610 |

| February 2018 | 2,558 |

| March 2018 | 3,166 |

| April 2018 | 3,303 |

| May 2018 | 3,359 |

| June 2018 | 2,511 |

| July 2018 | 2,078 |

| August 2018 | 2,265 |

| September 2018 | 2,635 |

| October 2018 | 2,792 |

| November 2018 | 3,935 |

| December 2018 | 3,107 |

| January 2019 | 2,182 |

| February 2019 | 2,369 |

| March 2019 | 3,416 |

| April 2019 | 3,041 |

| May 2019 | 2,845 |

| June 2019 | 2,220 |

| July 2019 | 2,079 |

| August 2019 | 2,154 |

| September 2019 | 2,452 |

| October 2019 | 2,578 |

| November 2019 | 2,371 |

| December 2019 | 1,968 |

| January 2020 | 1,602 |

| February 2020 | 1,679 |

| March 2020 | 1,768 |

| April 2020 | 2,161 |

| May 2020 | 1,377 |

| June 2020 | 1,934 |

| July 2020 | 1,221 |

| August 2020 | 1,264 |

| September 2020 | 1,773 |

| October 2020 | 2,082 |

| November 2020 | 2,169 |

| December 2020 | 2,161 |

| January 2021 | 1,988 |

| February 2021 | 1,588 |

| March 2021 | 1,974 |

| April 2021 | 1,892 |

| May 2021 | 1,617 |

| June 2021 | 1,224 |

| July 2021 | 981 |

| August 2021 | 983 |

| September 2021 | 1,286 |

| October 2021 | 1,714 |

| November 2021 | 1,757 |

| December 2021 | 1,510 |

| January 2022 | 1,419 |

| February 2022 | 1,028 |

| March 2022 | 1,344 |

| April 2022 | 993 |

| May 2022 | 947 |

| June 2022 | 698 |

| July 2022 | 534 |

| August 2022 | 337 |

| September 2022 | 496 |

| October 2022 | 836 |

| November 2022 | 817 |

| December 2022 | 701 |

| January 2023 | 682 |

| February 2023 | 419 |

| March 2023 | 636 |

| April 2023 | 706 |

| May 2023 | 656 |

| June 2023 | 422 |

| July 2023 | 709 |

| August 2023 | 343 |

| September 2023 | 411 |

| October 2023 | 619 |

| November 2023 | 751 |

| December 2023 | 501 |

| January 2024 | 534 |

| February 2024 | 345 |

| March 2024 | 685 |

| April 2024 | 671 |

| May 2024 | 687 |

| June 2024 | 388 |

| July 2024 | 23 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1477-4526

- Print ISSN 0951-0893

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

What Does a Critical Period for Second Language Acquisition Mean?: Reflections on Hartshorne, Tenenbaum, and Pinker (2018)

Arturo E. Hernandez was the lead author and worked on all aspects of the manuscript. Jean Bodet was involved in the revision and the incorporation of Neuroemergentist models of language development. Kevin Gehm and Shutian Shen worked on the description of the previous work by Hartshorne and colleagues.

Hartshorne, Tenenbaum and Pinker (2018) used a very large sample in order to disentangle the effects of age, years of experience, and age of exposure from each other in context of second-language acquisition. Participants were administered an online test of English grammar. Results revealed a critical period ending around 17 years of age for the most effective acquisition of a second language (L2). The findings of a late cutoff indicate the age range of late childhood to late adolescence as crucial for learning an L2. In this piece, we argue that these results can be conceptualized by emergentist models of language acquisition in which both behavior and brain interactively reorganize across development.

Introduction

Hartshorne, Tenenbaum, and Pinker (2018) , henceforth HTP, present evidence for a critical period of second-language (L2) syntax acquisition that extends into late adolescence, only declining around the age of 17. We, as well as HTP, have come to the conclusion that the proposed critical period may be representative of a change in a behavioral skill with more breadth than simply L2-syntax learning. In other words, we propose that the window closing on syntax acquisition in L2 (or, for that matter, any other sub-skill of language acquisition) falls under the closing of a larger biological window of opportunity of some kind.

To better operationalize a ‘critical period,’ Johnson (2011) proposes a framework distinguishing between neurobiological and behavioral views of the critical period. Johnson suggests that, while it may be unreliable to reduce behavior to brain or biological processes, modelling the underlying hardware to a behavior (in this case, L2 syntax learning) could provide insight on the emergence of higher levels of behavior. Johnson further hypothesizes that increased performance in different behavioral domains could be explained by the development of supporting neural “hardware.” HTP rightly point out that “it is hard to say whether any of the identified neural maturational processes might correspond to the changes in syntax acquisition that we observed” (p. 275), so a framework for examining neural changes alongside behavioral performance may be of use in analyzing the developmental trajectory of a skill. In other words, combining neural and behavioral approaches would allow us to connect the development of one to corresponding changes in the other. Using this approach we attempt to elucidate what broader skills may share similar neural and behavioral developments and so underlie the changes in language-specific skills. To this end, we propose the use of two models to connect neural development with behavioral development: Interactive Specialization (IS) ( M. H. Johnson, 2011 ) and Neuroemergentism (NM).

Our argument regarding HTP’s critical period results is that they may not be confined to the narrow domain of L2 syntax learning but represent larger behavioral and neural changes. Therefore, given the power of their study from such a large sample size, their findings may serve as an effective tool for further research into the ways in which behavior and neurobiology organize and reorganize across development. These IS and NM frameworks in concert with the critical period proposed by HTP are likely to shed light on the nature of development. The predictions listed here, based on each framework given HTP’s data, would be instrumental in further testing this critical period. In order to more clearly flesh this argument out, we will review HTP’s findings.

A short summary of HTP’s findings

Hartshorne, Tenenbaum, and Pinker (2018) use a much larger than normal sample (680,333 participants) to investigate the nature of a potential critical period for second language acquisition. HTP argue that a large sample was required in order to make sense of the potential effects that the age of an individual, age of first exposure to L2, and duration of exposure to L2 could have on their results. The use of this approach allowed the authors to arrive at a model that is better able to determine the shape of any decline in L2-learning ability. Analysis puts the onset of this decline at 10-12 years of age, marking the end of the putative “critical period” for L2 learning. Support for this conclusion comes from the small amount of variation in task performance between individuals who began L2 learning in the first decade of life. A sharp decline represents the end of ability in the ‘ultimate’ acquisition of L2 syntax (where abilities could ever reach native-like) beginning around 17.4 years of age. The authors attribute this decline to changes specific to late adolescence, rather than developmental changes that occur in early childhood or during the onset of puberty (for further discussion see Johnson & Newport, 1989 ).

Further support for HTP’s critical period comes from another recent study using online tests to amass an enormous sample size like HTP. In 2015, Hartshorne & Germine found that language task performance (word-pairs in long and short-term memory; word lists) dropped starkly in the late teens. Few other tasks ( i.e. , Reversed Lists, Long-Term Memory for Faces, Arithmetic, Vocabulary knowledge, etc.) had such early drop-offs in performance—most declines seem to occur far later in life. This (and HTP’s complimentary data) contradicts the tendency to focus on early childhood and infancy as the critical periods for language acquisition: developmentally, the experience-dependent ‘word boom’ in early childhood has always represented the peak of language acquisition, and performance afterwards is a trough ( Dale & Fenson, 1996 ; Fenson et al., 1994 ; Weisleder& Fernald, 2013 ). Though, even early-life critical periods of language learning have led to the proposal of a shared mechanism (as do the present proposal and HTP) with other forms of early learning ( Watson et al., 2014 ).

Finally, as an aside, it is worth noting that critical periods in L2 have a more nuanced nature than critical periods in a first language (L1), especially when sequentially acquired (languages not learned simultaneously). Namely, the learning of an L2 builds upon other existing skills that are already present at the time that L2 learning begins ( Newport et al., 2001 ). Any developmental model of language learning must contend with this while also considering the neural processes across the lifespan that may affect (or, more specifically, limit) L2 acquisition.

So far, we have reviewed HTP’s results indicating a steep decline of L2 syntax-learning ability around 17.4 years of age. HTP argue that this finding is compatible with the view that language learning ability is the only ability to show a drop so early in life. We also noted that HTP’s findings may actually be consistent with the view that general cognitive functions may be declining in late adolescence. Recall that this does, however, contrast with the far earlier critical periods for language learning that have been previously discussed in the literature. This raises the need for an explanation of the later-closing critical period; one that takes into account the complications of Unlearning through the lenses of neural development and behavioral development.

Implications of HTP’s findings

In the remaining section of this piece we will consider the implications of HTP’s findings focusing on three specific questions: 1) Why does HTP’s critical period close so much later than those generally used in the language acquisition literature? 2) What role might the decline of other broader cognitive skills play in the decline of L2 learning abilities? 3) What models may best explain the late close of HTP’s critical periods in terms of said other skills? Here, we present two models, Interactive Specialization (IS) and Neuroemergentism (NM) which focus on the relationship between the brain, behavior and development. Taken together these two models may resolve Question 3 and aid in explanations of Questions 1 and 2 using HTP’s data.

The IS framework is centered on the interaction between neighboring brain regions that are specialized to certain tasks leading to behaviors. It proposes a number of clear hypotheses on how this may play out in terms of regional specialization and inter-regional interaction: a) as brain regions specialize, the behaviors associated with activation in said area become more specific and their response to unimportant stimuli diminishes; b) amount of localization for any particular skill can be linked directly to the degree of specialization for that skill; c) a region of the brain with high levels of specialization will be less plastic in the wake of injury than it would if it were less specialized (as it may have been at earlier points in life); d) as cognitive skills develop behaviorally, so too physically do their associated regions; e) as regions specialize and develop, so too do their networks, and vice-versa, leading to smaller, more specialized networks; f) as regions specialize, they are influenced by and so influence their neighbors’ specializations.

IS suggests that behavioral and neural development are a reciprocal process, and over time regions and networks will become more specialized on their own, as networks interconnected within themselves, and in neighborhoods (all reciprocally). This framework has been used to account for language development. For instance, the comparison in brain activity observed before and after the period of extreme vocabulary growth during early childhood revealed language-related activity that was more generalized both in regions of activation and in stimuli to which they would react (see Johnson [2011 , p. 14] for more). Applied to HTP’s critical period data, the IS framework would make a number of predictions.

First, it would predict that activity seen during L2 syntax learning (such as event-related potentials seen in electroencephalograms or cortical blood flow activity changes in functional magnetic resonance imaging scans) would become more specialized over the course of HTP’s critical period (approximately 10-17 years)— i.e., that areas specializing in syntax-learning would show less activity to irrelevant or incorrect stimuli. Second, as key regions further specialize within the behavior, their neighboring regions will retain and refine pertinent abilities and the behavior’s neural networks will shrink. Third, injured neighboring regions’ abilities would not be as readily adopted by other regions in later years of the critical period as in earlier.

Applied to our critical questions, these might offer some solutions. In response to Question 1, the later-closing critical period may be attributed to a longer period of neural development than previously expected: perhaps the hyper-specialization of related regions continues long after heightened plasticity of infancy typically associated with L2 learning ability. To test this, a longitudinal study of language networks and/or activation (fMRI, ERP, etc.), or a cohort-based study of the same regions of interest would help to disambiguate this possibility. In particular, differences before and after early childhood and before and after puberty could be compared and tracked longitudinally. In doing so, we may also be able to answer Question 2 and observe the development of specialized regions (related skills) that were clearly involved in the network in early childhood but pruned out over adolescence and now only tangentially involved. By this method, we may be able to see what skills’ rise and fall could lead to the consequent abilities in L2 learning.

Such a methodology has recently been leveraged by Váša and colleagues in order to understand how the brain changes during adolescence ( Váša et al., 2020 ). To do this they tracked changes in functional connectivity in a group of 14- and 26-year-olds with a focus on cortical and subcortical brain regions over the course of more than 1.5 years. The results of their analyses revealed two different forms of change across development. Some areas showed conservative growth in that they led to stronger connectivity across time whereas others were disruptive in that the interconnectivity changed (either by strengthening or weakening) across development. The areas of the brain represented in these two different types of networks has the potential to shed light on HTP’s data. Areas that were conservative where those involved in sensorimotor processing including but not limited to domains such as movements of body parts and sensory modalities. Areas that showed disruption were associated with higher-level cognition such as memory, theory of mind, and language or sentence processing. Areas that had a disruptive role included those involved in cortical-subcortical communication as well as association areas involved in cortical-cortical processing such as the parietal and prefrontal cortex. Future studies could observe whether the closing of a critical period for syntax does or does not align with the neuroanatomical changes that are occurring during this phase. In a similar vein, studies could also ask participants to complete a number of cognitive, perceptual and motor tasks as well as some second language tasks at different ages. In this way, it would help to see the extent to which second language acquisition might rely on different underlying factors. Using both a behavioral and a neural approach, future studies could investigate the ways in which changes in the ability to learn a second language may shed light on the type of window that is closing during adolescence.

A second framework that may be of use is Neuroemergentism (NM) ( Hernandez et al., 2019 ). NM combines the concepts of a number of different emergentist approaches to neurobehavioral development over the lifespan, including Neuronal Recycling, Neural Reuse and Neuroconstructivism ( Anderson, 2010 ; Dehaene & Cohen, 2007 ; Goldberg, 2006 ; Tomasello, 2009 ; Anderson, 2016 ; Karmiloff-Smith, 2006 ). Essentially, NM provides a developmental framework to account for the specialization of regions and networks in the brain supporting new skills (like language). It considers ontogenetic (individual) development in the discussion of phylogenetic (evolutionary) predispositions of certain regions to certain large-scale skills. These phylogenetically predisposed regions (for instance, the primary auditory cortex) can then be recruited during developmental periods ( i.e. , HTP’s critical period) to perform new functions in a broader ability (like leveraging skills from the auditory systems in language comprehension).

For example, the Visual Word Form Area (VWFA) is specialized for reading and located in the fusiform gyrus across multiple language groups. Although specialized reading had no reason to exist until very recently, reading results in very uniform patterns of neural activity ( Dehaene & Cohen, 2007 ). As was eloquently stated by the authors of the NM framework when discussing Neural Reuse and the VWFA: “The presence of a clearly defined and consistently located VWFA in humans provides evidence this area adapted functions from one set of areas for a very different purpose. The original area was likely involved in more elementary functions such as detecting lines, curves, and intersections. The fact that it was dedicated to such basic functions makes it, according to Anderson (2010) , an ideal circuit for neural reuse and the development of human language and reading. Anderson points out that areas like the VWFA show how the brain can take evolutionarily older areas and reuse them for newer purposes.” ( Hernandez et al., 2019 ).

NM also highlights the idea that no developmental change is isolated to any one region or skill (behavioral or cognitive). This builds on previous work by Elizabeth Bates (1979) who used an emergentist approach to describe the nature of language representation and its neural bases. This can be seen in her classic example of a giraffe which makes use of the same neck bones present in humans. This new neck is not its own new organ, though, nor is its change isolated; the giraffe’s cardiovascular system must adapt to the new height of the head, its back legs must shorten to accommodate the new, higher center of gravity. In the same way, no brain region changes on its own, and to consider it to be singularly responsible for that skill (like a long neck for eating from high trees, or the Fusiform gyrus area for face recognition) would be short-sighted. Should there be an injury (genetic, neural, etc.) to any given skill at some point in its development, that injury would snowball across any number systems, no matter how tangentially involved.

NM complements the approach taken by IS. Both consider the development of specialization: IS via the effect of pruning (localization) of skills to ever-smaller regions and networks, and how those regions affect their neighbors’ specializations; NM via the evolutionary and individual developmental backgrounds of any given ‘old’ system that may be co-opted for ‘new’ skills and the diffuse effects of injury. NM differentiates itself by including the evolutionary background of regions as well as individual changes that occur across the lifespan.

Answers to the questions surrounding HTP’s critical period using the NM framework would be more general than IS. First, it would predict that early-life injury (genetic or neural) to any system involved in syntax learning, no matter how distal, would have an observable effect on the critical period development of that skill. Taken with IS, this could be observed by ERP or fMRI activity over that period when compared to neurodevelopmentally typical L2 learners (Question 1). This could also help elucidate what other cognitive processes are involved in L2 syntax learning through the effect of their injury (again, no matter how tangentially connected) (Question 2). Also, as is illustrated in the original paper, studies on the evolutionary bases of those involved systems may elucidate how they were adapted to L2 syntax learning (also Question 2). Again, these predictions are far more abstract, but this matches the more general framework of NM.

Much discussion of this mysteriously late-closing CP is beyond the scope of this paper, which only seeks to incorporate new frameworks into elucidating its causes. Future research should also consider the age at which this CP would begin, and how that may be modulated by bilingual or monolingual early-life experience. Following this line of thought, research into the difference between early/simultaneous bilinguals and late/sequential bilinguals would also be interesting. IS predicts that during early-life, neighboring regions and networks would be more interactive and interconnected. Thus, an early bilingual could develop and incorporate various skills for use in learning and controlling their languages, while a late bilingual would be limited in their adaptive abilities by the lower plasticity of later life. Research comparing the functional connectivity of highly specialized regions involved in syntax between early and late bilinguals would highlight such incorporation (or exclusion) of other skills or networks. Research of this kind would also address how age of acquisition of L2 influences later-life skills and the differences between monolinguals and bilinguals in HTP’s original work. Understanding how early bilinguals use other skills to improve their language abilities from such a plastic period of life would aid in explaining the differences they show in those skills when later compared to monolinguals and late bilinguals.

These frameworks are neurobiological, and this discussion is meant to encourage linking cognitive and biological approaches, but the effect of environment cannot be ignored when considering critical periods and cognitive development. In fact, inherent in the discussion of genetic predisposition is the need to understand how it interacts with environmental influence. Perhaps such factors as socioeconomic status may have a strong effect on how late a CP like HTP’s closes. Considering how the effects of such factors may differ between early and late bilinguals will also play a role in understanding their influence on the development of skills such as syntax learning.

HTP’s publication involving a large number of participants led to the identification of a critical period for syntax with the window for the acquisition closing at 17.4 years of age. In this piece we describe two frameworks, Interactive Specialization and Neuroemergentism, that could be leveraged in further investigations of HTP’s evidenced critical period and the mechanisms underlying the critical period’s closure. We hope to stimulate future studies that seek to more closely link the closing of this window with neurobiological indices and accompanying psychological processes.

Acknowledgments

The authors confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome . Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health to the National Institute On Aging under Award Number R21AG063537 as well as to the National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development under the Award Number P50HD052117. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

- Anderson ML (2010). Neural reuse: A fundamental organizational principle of the brain . Behavioral and Brain Sciences , 33 ( 4 ), 245–266. 10.1017/S0140525X10000853 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson ML (2016). Neural reuse in the organization and development of the brain . Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology , 58 ( S4 ), 3–6. 10.1111/dmcn.13039 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bates E (1979). The Emergence of Symbols: Cognition and Communication in Infancy . Academic Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dale PS, & Fenson L (1996). Lexical development norms for young children . Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers , 28 ( 1 ), 125–127. 10.3758/BF03203646 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dehaene S, & Cohen L (2007). Cultural Recycling of Cortical Maps . Neuron , 56 ( 2 ), 384–398. 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.004 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fenson L, Dale PS, Reznick JS, Bates E, Thai DJ, & Pethick SJ (1994). Variability in early communicative development . Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development , 59 ( 5 ), 1–173; discussion 174–185. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goldberg AE (2006). Constructions at Work: The Nature of Generalization in Language . Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hartshorne JK, & Germine LT (2015). When Does Cognitive Functioning Peak? The Asynchronous Rise and Fall of Different Cognitive Abilities Across the Life Span . Psychological Science , 26 ( 4 ), 433–443. 10.1177/0956797614567339 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hartshorne JK, Tenenbaum JB, & Pinker S (2018). A critical period for second language acquisition: Evidence from 2/3 million English speakers . Cognition , 177 , 263–277. 10.1016/j.cognition.2018.04.007 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hernandez AE, Claussenius-Kalman HL, Ronderos J, Castilla-Earls AP, Sun L, Weiss SD, & Young DR (2019). Neuroemergentism: A framework for studying cognition and the brain . Journal of Neurolinguistics , 49 , 214–223. 10.1016/j.jneuroling.2017.12.010 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnson JS, & Newport EL (1989). Critical period effects in second language learning: The influence of maturational state on the acquisition of English as a second language . Cognitive Psychology , 21 ( 1 ), 60–99. 10.1016/0010-0285(89)90003-0 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnson MH (2011). Interactive Specialization: A domain-general framework for human functional brain development? Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience , 1 ( 1 ), 7–21. 10.1016/j.dcn.2010.07.003 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Karmiloff-Smith A (2006). The tortuous route from genes to behavior: A neuroconstructivist approach . Cognitive, Affective and Behavioral Neuroscience , 6 ( 1 ), 9–17. Scopus 10.3758/CABN.6.1.9 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Newport EL, Bavelier D, & Neville HJ (2001). Critical thinking about critical periods: Perspectives on a critical period for language acquisition . In Language, brain and cognitive development: Essays in honor of Jacques Mehler (pp. 481–502). The MIT Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tomasello M (2009). Constructing a Language . Harvard University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Váša F, Romero-Garcia R, Kitzbichler MG, Seidlitz J, Whitaker KJ, Vaghi MM, Kundu P, Patel AX, Fonagy P, Dolan RJ, Jones PB, Goodyer IM, the NSPN Consortium, Vértes PE, & Bullmore ET. (2020). Conservative and disruptive modes of adolescent change in human brain functional connectivity . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , 117 ( 6 ), 3248–3253. 10.1073/pnas.1906144117 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Watson TL, Robbins RA, & Best CT (2014). Infant perceptual development for faces and spoken words: An integrated approach: Development of Face and Spoken Language Recognition . Developmental Psychobiology , 56 ( 1 ), 1454–1481. 10.1002/dev.21243 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Weisleder A, & Fernald A (2013). Talking to Children Matters: Early Language Experience Strengthens Processing and Builds Vocabulary . Psychological Science . 10.1177/0956797613488145 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Breadcrumbs Section. Click here to navigate to respective pages.

Second Language Acquisition and the Critical Period Hypothesis

DOI link for Second Language Acquisition and the Critical Period Hypothesis

Get Citation

Second Language Acquisition and the Critical Period Hypothesis is the only book on the market to provide a diverse collection of perspectives, from experienced researchers, on the role of the Critical Period Hypothesis in second language acquisition. It is widely believed that age effects in both first and second language acquisition are developmental in nature, with native levels of attainment in both to be though possible only if learning began before the closure of a "window of opportunity" – a critical or sensitive period. These seven chapters explore this idea at length, with each contribution acting as an authoritative look at various domains of inquiry in second language acquisition, including syntax, morphology, phonetics/phonology, Universal Grammar, and neurofunctional factors. By presenting readers with an evenly-balanced take on the topic with viewpoints both for and against the Critical Period Hypothesis, this book is the ideal guide to understanding this critical body of research in SLA, for students and researchers in Applied Linguistics and Second Language Acquisition.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter 1 | 22 pages, david birdsong, chapter 2 | 16 pages, christine m.weber-fox and helen j.neville, chapter 3 | 26 pages, co-evolution of language size and the critical period, chapter 4 | 36 pages, lynn eubank and kevin r.gregg, chapter 5 | 32 pages, age of learning and second language speech, chapter 6 | 28 pages, theo bongaerts, chapter 7 | 22 pages, ellen bialystok and kenji hakuta.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Taylor & Francis Online

- Taylor & Francis Group

- Students/Researchers

- Librarians/Institutions

Connect with us

Registered in England & Wales No. 3099067 5 Howick Place | London | SW1P 1WG © 2024 Informa UK Limited

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Critical period in second language acquisition: the age-attainment geometry.

- Teachers College, Columbia University, New York City, NY, United States

One of the most fascinating, consequential, and far-reaching debates that have occurred in second language acquisition research concerns the Critical Period Hypothesis [ 1 ]. Although the hypothesis is generally accepted for first language acquisition, it has been hotly debated on theoretical, methodological, and practical grounds for second language acquisition, fueling studies reporting contradictory findings and setting off competing explanations. The central questions are: Are the observed age effects in ultimate attainment confined to a bounded period, and if they are, are they biologically determined or maturationally constrained? In this article, we take a sui generis , interdisciplinary approach that leverages our understanding of second language acquisition and of physics laws of energy conservation and angular momentum conservation, mathematically deriving the age-attainment geometry. The theoretical lens, termed Energy Conservation Theory for Second Language Acquisition, provides a macroscopic perspective on the second language learning trajectory across the human lifespan.

Introduction

The Critical Period Hypothesis (CPH), as proposed by [ 1 ], that nativelike proficiency is only attainable within a finite period, extending from early infancy to puberty, has generally been accepted in language development research, but more so for first language acquisition (L1A) than for second language acquisition (L2A).

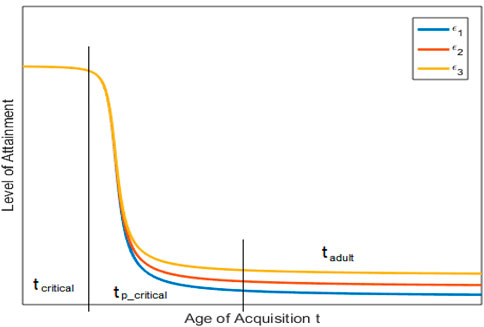

In the context of L2A, there are two parallel facts that appear to compound the difficulty of establishing the validity of CPH. One is that there is a stark difference in the level of ultimate attainment between child and adult learners. “Children eventually reach a more native-like level of proficiency than learners who start learning a second language as adults” ([ 2 ], p . 360). But this fact exists alongside another fact, namely, that there are vast differences in ultimate attainment among older learners. [ 3 ] observed:

Although few adults, if any, are completely successful, and many fail miserably, there are many who achieve very high levels of proficiency, given enough time, input, and effort, and given the right attitude, motivation, and learning environment. ( p . 13).

The dual facets of inter-learner differential success are at the nexus of second language acquisition research. As [ 4 ] once noted:

One of the enduring and fascinating problems confronting researchers of second language acquisition is whether adults can ever acquire native-like competence in a second language, or whether this is an accomplishment reserved for children who start learning at a relatively early age. As a secondary issue, there is the question of whether those rare cases of native-like success reported amongst adult learners are indeed what they seem, and if they are, how it is that such people can be successful when the vast majority are palpably not. ( p . 219).

The primary question Kellerman raised here is, in essence, a critical period (CP) question, concerning differential attainment between child and adult learners, and his secondary question relates to differential attainment among adult learners.

As of this writing, neither question has been settled. Instead, the two phenomena are often seen conflated in debates, including taking evidence for one as counter-evidence for the other (see, e.g., [ 5 ]). By and large, it would seem that the debate has come down to a matter of interpretation; the same facts are interpreted differently as evidence for or against CPH (see, e.g., [ 5 – 7 ]). This state of affairs, tinted with ideological differences over the role of nature and/or nature in language development, continues to put a tangible understanding of either phenomenon out of reach, let alone a coherent understanding of both phenomena. In order to break out of the rut of ‘he said, she said,” we need to engage in systems thinking.

Our research sought to juxtapose child and adult learners, as some researchers have, conceptually, attempted (see, e.g., [ 8 – 11 ]). Specifically, we built on and extended an interdisciplinary model of L2A, Energy Conservation Theory for L2A (ECT-L2A) [ 12 , 13 ], originally developed to account for differential attainment among adult learners, to child learners. In so doing, we sought to gain a coherent understanding of the dual facets of inter-learner differential success in L2A, in addition to mathematically obtaining the geometry of the age-attainment function, a core concern of the CPH/L2A debate.

In what follows, we first provide a quick overview of the CPH research in L2A. We then introduce ECT-L2A. Next, we extend ECT-L2A to the age issue, mathematically deriving the age-attainment function. After that, we discuss the resultant geometry and the fundamental nature of CPH/L2A, and, more broadly, L2 attainment across the human lifespan. We conclude by suggesting a number of avenues for furthering the research on CPH within the framework of ECT-L2A.

However, before we proceed, it is necessary to note two “boundary conditions” we have set for our work. First, the linguistic domain in which we theorize inter-learner differential attainment concerns only the grammatical/computational aspects of language, or what [ 14 , 15 ] calls basic language cognition, which concerns aspects of language where native speakers show little variance. As [ 2 ] has aptly pointed out, much of the confusion in the CPH-L2A debate is attributable to a lack of agreement on the scope of linguistic areas affected by CP. Second, we are only concerned with naturalistic acquisition (i.e., acquisition happens in an input-rich or immersion environment), not instructed learning (i.e., an input-poor environment). These two assumptions are often absent in CPH/L2A research, leading to the different circumstances under which researchers interpret the CP notion and empirical results (for discussion, see [ 7 ]).

The critical period hypothesis in L2A

To date, two questions have dominated the research and debate on CPH/L2A: What counts as evidence of a critical period? What accounts for the age-attainment difference between younger learners and older learners? More than 4 decades of research on CPH/L2A- from [ 16 ] to [ 17 ] to [ 18 ]—have, in the main, found an inverse correlation between the age of acquisition (AoA) and the level of grammatical attainment (see also [ 19 ], for a meta-analysis); “the age of acquisition is strongly negatively correlated with ultimate second language proficiency for grammar as well as for pronunciation” ([ 20 ], p . 88).

However, views are almost orthogonal over whether the observed inverse correlation can count as evidence of CPH or the observed difference is attributable to brain maturation (see, e.g., [ 5 , 7 , 21 – 35 ]).

For some researchers, true evidence or falsification of CPH for L2A must be tied to whether or not late learners can attain a native-like level of proficiency (e.g., [ 36 ]). Others contend that the nativelikeness threshold, in spite of it being “the most central aspect of the CPH” ([ 2 ], p . 362), is problematic, arguing that monolingual-like native attainment is simply impossible for L2 learners [ 37 , 38 ]. Echoing this view, [ 39 ] offered:

[Sequential] bilinguals are not “two monolinguals in one” in any social, psycholinguistic, or cognitive neurofunctional sense. From this perspective, it is of questionable methodological value to quantify bilinguals’ linguistic attainment as a proportion of monolinguals’ attainment, with those bilinguals reaching 100% levels of attainment considered nativelike. ( p . 121).

In the meantime, empirical research into adult learners have consistently produced evidence of selective nativelike attainment, that is, nativelikeness is attained vis-à-vis some aspects of the target language but not others. These studies employed a variety of methodologies, including cross-sectional studies and longitudinal case studies (see, e.g., [ 40 – 56 ]). Some researchers (e.g., [ 55 , 57 ]) take the selective nativelikeness as falsifying evidence of CPH/L2A; other researchers disagree (see, e.g., [ 36 ]).

Leaving aside the vexed issue of nativelikeness, 1 Birdsong [ 58 ], among others, postulated that CPH/L2A must ultimately pass geometric tests: if studies comparing younger learners and older learners yield the geometry of a “stretched Z” for the age-attainment function, that would prove the validity of CPH/L2A, or falsify it, if otherwise. The stretched Z or inverted S [ 20 ] references a bounded period in which the organism exhibits heightened neural plasticity and sensitivity to linguistic stimuli from the environment. This period has certain temporal and geometric features. Temporally, it extends from early infancy to puberty, coinciding with the time during which the brain undergoes maturation [ 1 , 36 , 59 – 62 ]. Geometrically, this period should exhibit two points of inflection or discontinuities, viz, “an abrupt onset or increase of sensitivity, a plateau of peak sensitivity, followed by a gradual offset or decline, with subsequent flattening of the degree of sensitivity” ([ 58 ], p . 111).

By the temporal and geometric hallmarks, few studies seem to have confirmed CPH/L2A, not even those that have allegedly found stark evidence. A case in point is the [ 17 ] study, which reported what appears to be clear-cut evidence of CPH/L2A: r = −.87, p <.01 for the early age of arrival (AoA) group and r = −.16, p >.05 for the late AoA group. As Johnson and Newport described it, “test performance was linearly related to [AoA] up to puberty; after puberty, performance was low but highly variable and unrelated to [AoA],” which supports “the conclusion that a critical period for language acquisition extends its effects to second language acquisition” ( p . 60). However, this claim has been contested.

Focusing on the geometry of the results, [ 58 ] pointed out that the random distribution of test scores within the late AoA group “does not license the conclusion that “through adulthood the function is low and flat” or the corresponding interpretation that “the shape of the function thus supports the claim that the effects of age of acquisition are effects of the maturational state of the learner” ([ 17 ], p . 79)” ( p . 117). Birdsong argued that if CPH holds for L2A, the performance scores of the late AoA group should be distributed horizontally in addition to showing marginal correlation with age. Accordingly, the random distribution of scores could only be taken as indicative of “a lack of systematic relationship between the performance and the AoA and not of a “levelling off of ultimate performance among those exposed to the language after puberty” ([ 17 ], p . 79)” ([ 58 ], p . 118).

Interpreting the same study, other researchers such as [ 20 ] did not set their sights as much on the random distribution of the performance scores among the late learners as on the discontinuity between the early AoA and late AoA groups, arguing that the qualitative difference is sufficient evidence of CPH/L2A.

If geometric satisfaction is one flash point in CPH/L2A research, explaining random distribution of performance scores or, essentially, differential attainment among late learners counts as another. Analyses of late learners’ ultimate attainment (e.g., [ 10 , 22 , 26 , 43 , 63 – 67 ]) have yielded a host of cognitive, socio-psychological, or experiential factors that can be associated with inter-learner differential attainment among late learners. The question, then, is whether or not these non-age factors confound, or even interact with, the age or maturational effect (see discussion in [ 2 , 68 – 72 ]. As Newport [ 7 ] aptly asked, “why cannot other variables interact with age effects?” ( p . 929).

These are undoubtedly complex questions for which sophisticated solutions are needed—beyond the methodological repairs many have thought are solely needed in advancing CPH/L2A research (see, e.g., [ 19 , 67 ]). In the remainder of this article, we take a different tack to the age issue, adopting a theoretical, hybrid approach, ECT-L2A [ 12 , 13 ], to mathematically derive the age-attainment function.

Energy-Conservation Theory for L2A

ECT-L2A is a theoretical model originally developed to account for the divergent states of ultimate attainment in adult L2A [ 12 , 13 ]. Drawing on the physics laws of energy conservation and angular momentum conservation, it theorizes the dynamic transformation and conservation of internal energies (i.e., from the learner) and external energies (i.e., from the environment) in rendering the learner’s ultimate attainment. This model, thus, takes into account nature and nurture factors, and specifically, uses five parameters - the linguistic environment or input, learner motivation, learner aptitude, distance between the L1 and the target language (TL) and the developing learner—and their interaction to account for levels of L2 ultimate attainment.

ECT-L2A draws a number of parallels between mechanical energies and human learning energies: kinetic energy for motivation and aptitude energy, potential energy for environmental energy, 2 and centrifugal energy for L1-TL deviation energy (for discussion, see [ 12 ]). These energies each perform a unique yet dynamic role. As the learner progresses in the developmental process, the energies shift in their dominance, while the total energy remains constant.

Mathematically, ECT-L2A reads as follows:

where ζ r denotes the learner’s motivational energy, r the learner’s position in the learning process relative to the TL, η the distance between L1 and TL, and ρ the input of TL. According to Eq. 1 , the total learning energy, ∈ , comes from the sum of motivation energy ζ r , aptitude (a constant) Λ , deviation energy η 2 r 2 , and environmental energy - ρ r .

The energy types included in Eq. 1 are embodiments of nature and nurture contributions. The potential energy or TL traction, - ρ r , represents the external or environmental energy, while the kinetic or motivational energy, ζ r , along with aptitude, Λ , and the centrifugal or deviation energy η 2 r 2 represent the internal energies.

Under the overarching condition of the total energy being the same or conserved throughout the learning process, ϵ = constant , each type of energy performs a different role, with one converting to another over time as the position of the learner changes in the developmental process.

For mathematical and conceptual convenience, (1) is rewritten into (2) which contains the effective potential energy, U eff (r) .

where U e f f r = η 2 r 2 − ρ r . In other words, the effective potential energy is the sum of deviation energy and the potential energy (see further breakdown in the next section).

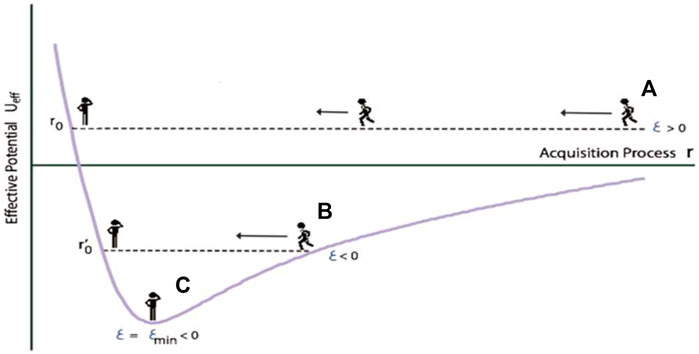

The L2A energy system as depicted here is true of every learner, meaning that the total energy is constant for a single learner. But the total energy varies from learner to learner. Accordingly, different learners may reach different levels of ultimate attainment (i.e., closer or more distant from the TL), r 0 . This is illustrated in Figure 1 , where r 0 and r 0 ′ represent the ultimate attainments for learners with different amounts of total energy, ϵ >0 or ϵ <0.

FIGURE 1 . Inter-learner differential ultimate attainment as a function of different amounts of total energy: ϵ >0; ϵ < 0; ϵ = ϵ min [ 12 , 13 ].

Key to understanding Figure 1 is that it is the individual’s total energy that determines their level of attainment. Of the three scenarios on display here, ECT-L2A is only concerned with the case of ϵ ≥0, which represents the unbound process (r 0 , ∞), ignoring the bounded processes of ϵ < 0; ε = ϵmin.

The central thesis of ECT-L2A, as expressed in Eq. 1 , is that the moment a learner begins to receive substantive exposure to the TL, s/he enters a ‘gravitational’ field or a developmental ecosystem in which s/he is initially driven by kinetic or motivational energy, increasingly subject to the traction of the potential or environmental energy, but eventually stonewalled by the deviation energy or centrifugal barrier, resulting in an asymptotic endstate. This trajectory is further elaborated below.

The developmental trajectory depicted and forecast by ECT-L2A

The L2A trajectory begins with the learner at the outset of the learning process or at infinity (r = ∞). Initially, their progression toward the central source, i.e., the TL, is driven almost entirely by their motivation energy and aptitude, as expressed in Eq. 3 .

As learning proceeds, but with r still large (i.e., the learner still distant from the target) and the deviation energy much weaker than the environmental energy, η 2 r 2 ≪ ρ r (due to the second power of r ), the motivation energy rises as a result of its “interaction” with the environmental energy− ρ r , in which case the environmental energy transfers to the motivation energy. Mathematically, this is expressed in Eq. 4 .

As learning further progresses, the environmental energy - ρ r becomes dominant before yielding to the deviation energy η 2 r 2 . Eventually, the deviation energy overrides the environmental energy, as expressed in Eq. 1 , repeated below as Eq. 5 for ease of reference.

The deviation energy is so powerful that it draws the learner away from the target and their learning reaches an asymptote, where their motivation energy becomes minimal, ζ ( r 0 ) = 0, as expressed in Eq. 6 .

At this point, all other energies submit to the deviation energy, including the initial motivation energy ζ (∞) and some of the potential or environmental energy. Consequently, further exposure to TL input would not be of substantive help, meaning that it would not move the learner markedly closer to the target.

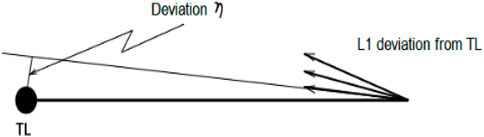

Figure 2 gives a geometric expression of the L1-TL deviation η, which is akin to the angular momentum of an object moving in a central force field [ 73 – 75 ]. The deviation from the TL, signifying the distance between the L1 and the TL, varies with different L1-TL pairings. For example, the distance index, according to the Automated Similarity Judgment Program Database [ 76 ], is 90.25 for Italian and English but 100.33 for Italian and Chinese.

FIGURE 2 . Geometric description of the deviation parameter η .

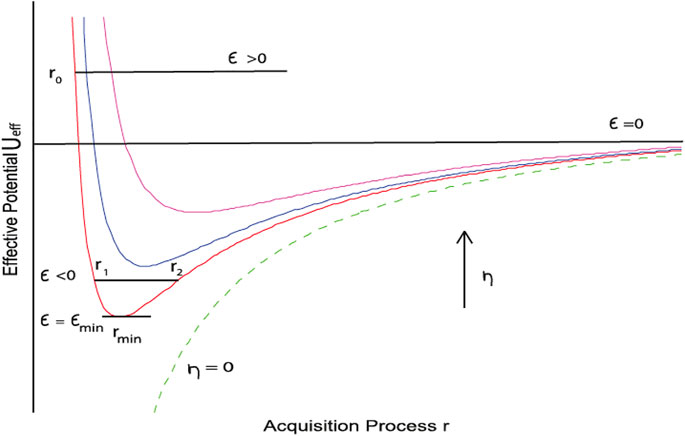

Figure 3 illustrates differential ultimate attainment (indicated by r 0 ) as a function of the deviation parameter η. As η increases, the level of attainment is lower or the attainment is further away from the target ( r = 0).

FIGURE 3 . Effective potentials U eff with different values of η [ 12 , 13 ].

For adult L2A, ECT-L2A predicts, inter alia , that high attainment is possible but full attainment is not. In other words, near-nativelike attainment is possible, but complete-nativelike attainment is not. ECT-L2A also predicts that while motivation and aptitude are part and parcel of the total energy of a given L2 learner, their role is largely confined to the earlier stage of development. Most of all, ECT-L2A predicts that the L1-L2 deviation is what keeps L2 attainment at asymptote.

For L2 younger learners, ECT-L2A also makes a number of predictions to which we now turn.

ECT-L2A vis-à-vis younger learners

As highlighted above, the deviation energy is what leads L2 attainment to an asymptote. It follows that as long as η (i.e., the L1-TL distance) is non-zero, the learner’s ultimate attainment, r 0 , will always eventuate in an asymptote. As shown in Figure 3 , the larger the deviation r 0 , the more distant the ultimate attainment r 0 is from the TL. Put differently, a larger η portends that learning would reach an asymptote earlier or that the ultimate attainment would be less native-like. But how does that work for child L2A?

On the ECT-L2A account, it is the low η value that determines child learners’ superior attainment. In child L2 learners, the deviation is low, because of the incipient or underdeveloped L1. However, as the L1 develops, the η value grows until it becomes a constant, presumably happening around puberty 3 , hence coinciding with the offset of the critical period [ 1 ]. As shown in Figures 1 , 3 , the smaller the deviation, η, the closer r 0 (i.e., the ultimate level of attainment) is to the TL or the higher the ultimate attainment.

From Eq. 6 the ultimate attainment of any L2 learner, irrespective of age, can be mathematically derived:

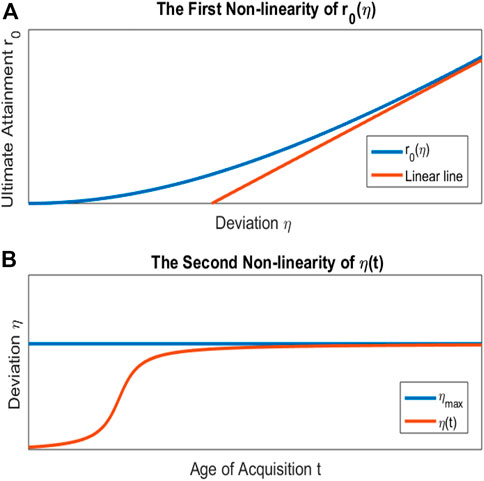

where ε = ϵ – Λ (i.e., total energy minus aptitude). r 0 here again denotes ultimate attainment. The upper panel in Figure 4 displays the geometry of ultimate attainment as a function of deviation, η.

FIGURE 4 . Double non-linearity of r 0 η [ (A) : first non-linearity] and η t [ (B) : second non-linearity] at early AoA.

For a given child learner, η is a constant, but different child learners can have a different η value, depending on their AoA . Herein lies a crucial difference from adult learning where η is a constant for all learners because of their uniform late AoA or age of acquisition and because their L1 has solidified. Adult learning starts at a time when the deviation between their L1 and the TL has become fixed, so to speak, as a result of having mastered their L1 (see the lower panel of Figure 4 ).

Further, for child L2 learners, η is simultaneously a function of their AoA, a proxy for time ( t ), and can therefore be expressed as η(t). This deviation function of time varies in the range of 0 ≤ η t ≤ η max . Accordingly; Eq. 7 can be mathematically rewritten into (8):

Assuming that as t grows or as AoA increases, η increases slowly and smoothly from 0 to η max until it solidifies into a constant, which marks the onset of adult learning, η( t ) can mathematically be expressed as (9).

where a is a constant. The geometry of the deviation function of time is illustrated in the lower panel of Figure 4 .

Figure 4 displays a double non-linearity characterizing L2 acquisition by young learners, with (A) showing the first order of non-linearity of r 0 η , that is, ultimate attainment as a function of deviation or the L1-TL distance (computed via Eq. 7 ), and with (B) displaying the second order of non-linearity, η (t), that is, η changing with t , age of acquisition (computed through Eq. 9 ).

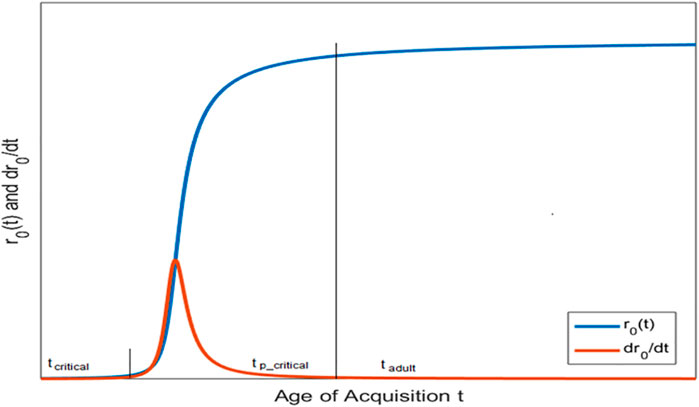

Figure 5 illustrates ultimate attainment as a function of AoA, r 0 (t), and its derivative against t , d r 0 d t , which naturally yields three distinct periods: a critical period, t critical ; a post-critical period, t p-critical ; and an adult learning period, t adult . Within the critical period, t critical , r 0 ≅ 0 , meaning there is no real difference in attainment as age of acquisition increases. But within the post-critical period, t p-critical , r 0 changes dramatically, with d r 0 d t peaking and waning until it drops to the level approximating that of the adult period. Within the adult period, t adult , r 0 remains a constant, as attainment levels off.

FIGURE 5 . Ultimate attainment (the blue line) as a function of age of acquisition ( t ) and its derivatives giving three distinct periods (the orange line).

ECT-L2A, therefore, identifies three learning periods. First, there is a critical period, t critical , within which attainment is nativelike, r 0 ≅ 0. Notice that the blue line in Figure 5 is the lowest during the critical period, signifying that the attainment converges on the target, but it is the highest during the adult period, meaning that the attainment diverges greatly from the target. The offset of the critical period is smooth rather than abrupt, with the impact of deviation, η , slowly emerging at its offset. During this period, the L1 is surfacing, yet with negligible deviation from the TL and weak in strength.

Key to understanding this account of the critical period is the double non-linearity: first, ultimate attainment as a function of L1-TL deviation ( r 0 ( η ), see (A) in Figure 4 ); and second, L1-TL deviation as a function of AoA ( η ( t ); see (B) in Figure 4 ). Crucially, this double non-linearity extends a critical “point” into a critical “period” .

Second, there is a post-critical period, t p-critical , 0 < r 0 ≤ r 0 ( η max ), within which, with advancing AoA, the L1-L2 deviation grows larger and stronger, resulting in ultimate attainment that is increasingly lower (i.e., increasingly non-nativelike). The change rate of r 0 , its first derivative to time, d r 0 d t , is dramatic, waxing and waning. As such, the post-critical period is more complex and nuanced than the critical period. During the post-critical period, as the learner’s L1 becomes increasingly robust and developed, the deviation becomes larger, resulting in a level of attainment increasingly away from the target (i.e., increasingly non-nativelike).

Third, there is an adult learning period, t adult , η = η max ≅ constant, where, despite the continuously advancing AoA, the deviation reaches its maximum and remains a constant, as benchmarked in indexes of crosslinguistic distance (see, e.g., the Automated Similarity Judgment Program Database [ 76 ]). As a result, L2 ultimate attainment turns asymptotic (for discussion, see [ 12 , 13 ]).

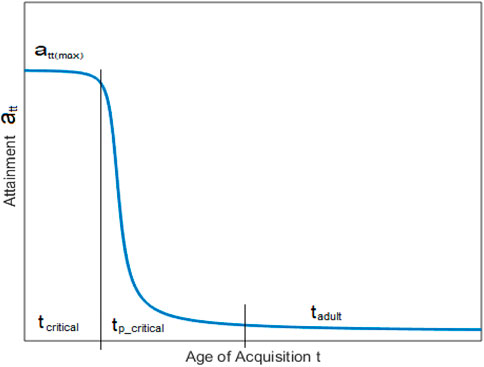

The three periods mathematically produced by ECT-L2A coincide with the stretched “Z” slope that some researchers have argued (e.g., [ 17 , 58 , 59 ]) constitutes the most unambiguous evidence for CPH/L2A, and by extension, for a maturationally-based account of the generic success or lack thereof (i.e., nativelike or non-nativelike L2 proficiency) in early versus late starters. For better illustration of the stretched “Z,” we can convert Figure 5 into Figure 6 , using Eq. 10 .

where a t t stands for level of attainment. According to Eq. 10 , the smaller the r 0 is, the higher the attainment is.

FIGURE 6 . Level of attainment as a function of AoA.

In sum, ECT-L2A mathematically establishes the critical period geometry. That said, the geometry, as seen in Figure 6 , exhibits anything but abrupt inflections; the phase transitions are gradual and smooth. The adult period, for example, does not exhibit a complete “flattening” but markedly lower attainment with continuous decline (cf. [ 7 , 23 , 28 ]). 4

Explaining CPH/L2A

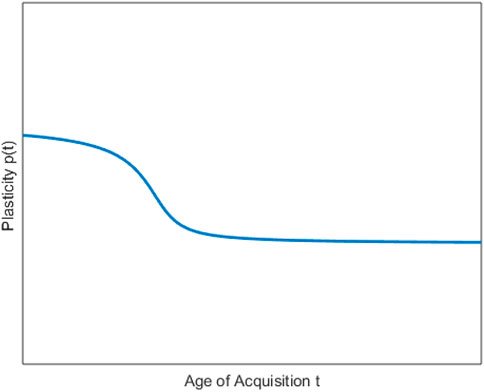

As is clear from the above, on the ECT-L2A account of the critical period, η (i.e., L1-TL deviation) is considered an inter-learner variable and, at once, a proxy for age of acquisition, t . More profoundly, however, ECT-L2A associates η with neural plasticity or sensitivity (cf [ 77 ]). The relationship between plasticity, p ( t ), and deviation function, η (t) , is expressed as (11):

Thus, the relationship between plasticity and the deviation function is one of inverse correlation. During the critical period, η = η min (i.e., minimal L1-TL deviation) and p = p max (i.e., maximal plasticity); conversely, during the adult learning period, η = η max (i.e., maximal L1-TL deviation) and p = p min (i.e., minimal plasticity). In short, an increased deviation, η (t) , corresponds to a decrease of plasticity, p (t) , and vice versa , as illustrated in Figure 7 .

FIGURE 7 . Plasticity as a function of age of acquisition.

Illustrated in Figure 7 is that neural plasticity, first proposed by [ 78 ] as the underlying cause of CP, is at its highest during the critical period and, as [ 79 ] put it, it “endures within the confines of its onset and offset” ( p . 182). But it begins to decline and drops to a low level during the post-critical period, and remains low through the adult learning period. 5 It would, therefore, seem reasonable to call the first period “critical” and the second period “sensitive.” It is worth mentioning in passing that the post-critical or sensitive period has thus far received scant empirical attention in CPH/L2A research.