Improving Your English Writing Skills as a Non-Native Speaker

Writing in English can be a daunting task for non-native speakers, especially when it comes to crafting blog content. Despite my familiarity with the language, accurately expressing myself remains a constant challenge.

However, through perseverance and exploration, I’ve discovered invaluable strategies to overcome these obstacles and improve my English writing skills .

Why I Started Blogging in English as a Non-Native Speaker

One of the primary motivations behind my decision to blog in English alongside Dutch was to expand my audience reach .

While Dutch is my native language, I recognized that limiting myself to this audience would restrict the potential impact of my content. By incorporating English into my blogging repertoire, I aimed to make my insights and perspectives accessible to a broader global audience .

Developing My English Writing Skills

The decision proved fruitful, as evidenced by the significantly increased viewership of my English articles compared to those written solely in Dutch.

It really showed me how important it is to make your content accessible in different languages. It’s all about reaching out to different folks and making those connections through what you write.

But let me tell you, writing in English isn’t just about being able to talk the talk. When I first dipped my toes into blogging in English, I realized there’s a whole other skill se t involved.

It was like starting from scratch, trying to get the hang of writing fluently and effectively.

Fortunately, there are various resources and techniques for quickly boosting your written English proficiency. After finding these tools and putting them into action, I’m now able to express myself confidently through my words!

And that’s why I’m here! This article is all about giving fellow non-native English speakers some handy tips and tricks to level up their writing game. I’m excited to share what I’ve learned and help you become a pro with your words.

Disclaimer: This blog post contains affiliate links . I may earn a small commission to fund my coffee-drinking habit if you use these links to make a purchase. You will not be charged extra. So it’s a win for everyone! Please note that I won’t link any products I don’t believe in or don’t resonate with my blog site. Thank you!

Do you have the linguistic proficiency needed to blog in English?

Feeling unsure about starting an English blog? Don’t sweat it! You’ve got what it takes.

Sure, writing in English might seem daunting at first, but having a blog is a fantastic chance to hone your skills. With a bit of practice and some careful editing, you’ll see your writing improve in no time.

Plus, having a blog means you can reach all sorts of people, even those who aren’t native English speakers. By keeping your language clear and relatable, you’ll make it easy for everyone to connect with your content.

So, if you’re itching to write in English, don’t hold back! Let your creativity flow and dive right in. Trust me, the right audience will find and appreciate your unique voice.

8 Tips to Elevate Your English Writing Skills

Tip #1: employ surfer seo for optimized content creation.

Surfer SEO is a comprehensive tool designed to assist content creators in generating SEO-friendly blog posts.

By analyzing search engine optimization (SEO) metrics and providing actionable insights, Surfer SEO enables writers to craft engaging and discoverable content in English.

Tip #2: DeepL Pro Translator for precise translations

DeepL Pro translator offers advanced translation capabilities, allowing writers to accurately convey their message in English.

With features such as customizable translations and context-based suggestions, DeepL Pro Translator facilitates seamless communication across language barriers.

Tip #3: Lingq App to Cultivate Your Vocabulary

The Lingq app serves as a valuable resource for language learners seeking to enhance their vocabulary and comprehension skills in English.

Through interactive lessons, reading materials, and vocabulary-building exercises, Lingq empowers users to expand their linguistic repertoire and improve their English writing proficiency.

Tip #4: Engage in language practice with native speakers via HelloTalk

HelloTalk provides a platform for language exchange and conversation practice with native English speakers. By engaging in real-time conversations and cultural exchanges, users can strengthen their English writing skills and gain valuable insights into language usage and expression.

Tip #5: Initiate writing drafts in your native language first

Starting with drafts in your native language allows for clearer articulation of ideas and concepts. Subsequently translating these drafts into English enables writers to refine their content while ensuring accuracy and coherence in the final output.

Tip #6: Foster a habit of consuming English literature regularly

Regular reading is essential for developing a strong command of the English language.

By immersing oneself in English literature, writers can familiarize themselves with diverse writing styles, vocabulary usage, and grammatical structures, thereby enhancing their English writing skills.

Tip #7: Allow ample time for writing, prioritizing quality over quantity

Writing is a process that requires time, patience, and dedication. By allocating sufficient time for brainstorming, drafting, and revising, writers can produce high-quality content that resonates with readers.

Prioritizing quality over quantity ensures that each piece of writing is meticulously crafted and engaging, thereby fostering reader engagement and retention.

Also watch this video by Learn English with Harry for more English writing tips:

If you put these techniques and resources into practice, you’ll soon find yourself becoming more and more comfortable with writing in English.

I hope that this post has provided the motivation and guidance you need to either begin or continue blogging in English, as well as create a multilingual website !

Please share your English blog links with me in the comments section!

About the Author

Angie is a blogger and creative entrepreneur from the Netherlands who is currently residing as a digital nomad in Serbia together with her husband and 2-year old daughter Ana Milena. She is the creator of She Can Blog and works as a Pinterest manager for several Dutch companies.

- Angie https://shecanblog.com/author/admin/ Child Admitted to ICU Abroad? Our Story of Coping as Digital Nomads

- Angie https://shecanblog.com/author/admin/ Reflecting on 2 Years of Living in Belgrade as a Digital Nomad

- Angie https://shecanblog.com/author/admin/ 25 Productivity-Boosting Smart Home Gadgets You Need Right Now

- Angie https://shecanblog.com/author/admin/ 11 Tips for Balancing Multiple Roles as a Home Business Owner

I like to take on challenges when come to blogging in English. There is nothing to shy. For me, even non-native English, you can express your thought and content.

As long as the message is there, I think you delivered well.

Hi Evie, thank you so much for your comment! I think you’re English is perfect, and there’s no need to be worried about writing in English at all. But, I feel ya, I’m still insecure about my English writing skills as well, but it gets easier to write. You got this! X

English is my native language but these are still excellent tips for anyone who needs them! Grammarly has been lifesaver for me too. 🙂

Thank you, Alyssa! If Grammarly had a Dutch version, I’d definitely use it as well! So, I can totally relate to that. Thanks for commenting! 🙂

I really want to try blogging but I’m having trouble expressing my thoughts and ideas in English. I’m glad that I ran into your blog post. I took down notes of all the tips you have mentioned. Thanks for sharing this.

You’re welcome 🙂 And I hope you’ll start blogging in English too!! Love your website!

Really love it!!! I hava a blog in spanish, but my readers speak ensglish!!! This stress me out a little but because I want to bring the best experience to them. This blog really encourage me to write in english!

You’re welcome! Glad to hear I encouraged you to do the same. Like the Google Translate widget on your blog!

Comments are closed.

Privacy Overview

8 Tips to Get Better at English Writing as a Non Native

Table of contents

Caroline Grape

Learning a new language can be difficult. Improving your writing skills in it can seem even harder.

I’ve learned four languages: English, Norwegian, Danish, and French, so I know first-hand the challenges of learning a new language. It can be tough to constantly improve your writing skills while also navigating the common pitfalls of being a non-native speaker. As a writer, it can be even more frustrating when you feel like you’re not able to articulate exactly what you want to say.

My journey as a writer and language-lover has led me to discover some helpful tips and tricks for improving your language skills. From total immersion to accepting mistakes, here are eight tried-and-tested ways to enhance your learning as a non-native English speaker when developing your English writing.

1. Immerse yourself

There's no better way to learn a new language than to immerse yourself in it to the fullest extent possible.

The most effective way to immerse yourself is, of course, moving to an English-speaking country. If that’s not possible for you, there are plenty of other ways to simulate a similar immersion. For example, focus on only speaking English and consuming content in English. Start by watching English TV shows and movies. Entertaining and educational, this is an easy, daily way to immerse yourself in the language.

For learning on the go, listen to podcasts. Podcasts are perfect for squeezing in that extra bit of language immersion when you’re busy. Find one about something you already love to make it more engaging. You could also consider podcasts specifically designed for English learning, like The Voice of America: Learning English . We recommend English Learning for Curious Minds , which is perfect for intermediate to advanced speakers. This podcast covers fascinating historical topics in each episode, tailored to help improve your English language learning. Listening to other people speak will help you to understand more when engaging with native English speakers, improve your connected speech, and build up your vocabulary. This will be incredibly useful when it comes to writing, as you’ll pick up common phrases and understand how to write naturalistically.

You should also practice conversing with native speakers where possible or attend language classes to test your knowledge. Many cities have free language cafés, designed to help non-native speakers have a place to communicate and practice their English.

Immersion is important, but make sure you take breaks to let yourself absorb the language and enjoy the process of learning it. Speak as much as you can, even if you make mistakes. Remember that making mistakes is part of the process! Finally, have fun with it and be patient.

2. Improve your vocabulary

Developing a solid vocabulary helps you improve your language skills. An adult native-speaker tends to have an average active vocabulary between 20,000-35,000 words . That’s a lot of words!

There are two forms of vocabulary when learning a new language: active and passive. Active vocabulary refers to the words that you understand easily in any context, without having to think about it too much. Passive vocabulary, on the other hand, are words that you can understand when reading or hearing them, but are harder to use when you are actively writing or speaking.

For example, if you’re asked to write a sentence using the word ‘serendipitous’ and you can do it easily, it is considered part of your active vocabulary.

Let’s consider passive vocabulary using the passage below:

“I started from my sleep with horror; a cold dew covered my forehead, my teeth chattered, and every limb became convulsed; when, by the dim and yellow light of the moon, as it forced its way through the window shutters, I beheld the wretch—the miserable monster whom I had created.” - Frankenstein , Mary Shelley

While you might not use terms like ‘beheld’ or ‘wretch’ in daily exchanges, if you can understand them when reading the passage these words are considered part of your passive vocabulary. Understanding the differences between active and passive vocabulary is particularly useful for building your writing skills. Once you identify any gaps, you can spend time developing the scope of your vocabulary.

If you’re looking to expand your vocabulary , consider using a dictionary to pick up and understand new words. You could also learn about root words or make up word associations .

Reading fiction that’s written for young adults is another great way to expand your active and passive vocabulary. The Harry Potter series, The Hunger Games trilogy, and The Perks of Being a Wallflower are all amazing books that can help you improve your vocabulary and reading comprehension. Young adult books tend to be easier to understand and will help you pick up new words in no time. Equally, you can read a newspaper or a magazine, or broaden your horizons by reading books in different genres.

You can also learn new words by playing word games or doing word puzzles. For example, you could complete a crossword or play Scrabble. Playing word games is a great way to expand your vocabulary, and using a dictionary or thesaurus while you play can help you find the definitions of unfamiliar words.

Journaling everyday is another great way to quickly become comfortable writing in English. However, this practice can get a bit repetitive. Using writing prompts is a great way to develop your vocabulary and keep it interesting. Consider setting aside time to practice your writing with some of these prompts:

- What was your favorite childhood memory?

- Write a story based on the last song you listened to.

- Write about a time when you were scared.

- Describe your perfect party.

- If you discovered a new planet, what would it look like?

By challenging yourself to use new words regularly, you will enhance and build your active vocabulary.

3. Treat everything as an opportunity to improve your English

Got an email to write? Write the %@#$ out of it. Got a group text you’re working on? Start by writing it longer than it needs to be and practice ways to shorten or rephrase it. Read news articles and books, watch movies and documentaries, and talk to people in English. Pay attention to the words and phrases used and try to incorporate them into your own writing. Don't be afraid to make mistakes and ask for help if you need it. Note down new words and phrases and review them often so they become part of your regular vocabulary. Practice speaking and writing in English every opportunity you get — this will help you feel more confident in your abilities.

4. Get by with a little help from your friends

It’s hard to ask for help, and it’s even harder to ask people to point out your mistakes, but this is one of the the most valuable steps you can take. Ask your colleagues and friends for feedback on your English, and be open to constructive criticism. This will help you to improve your skills and knowledge. Accept their feedback graciously; it’s not a personal attack. After all, you can’t improve if you don’t know what you’re doing wrong!

Consider asking a colleague or friend for feedback on a piece of writing you’ve done. E-mails, letters, prose, and any other piece of writing you have are all text your friend could look over. Any notes they give you can help you identify key areas for improvement and mistakes you might have missed. Make sure you’re asking native English speakers to help you.

Asking for feedback will also help you to build relationships and develop trust with others. Don’t forget to thank those who help you and acknowledge the value of their input.

5. Identify your patterns

We can all fall into bad habits. The same goes for language learning. Based on what your friends and colleagues pointed out, see if you can identify patterns and recurring mistakes that you can focus on improving. Make a plan of action to address those mistakes. Set achievable goals and do your best to stick to them. Consider keeping a notebook where you can jot down any mistakes. This way, you can quickly notice any patterns, which will make you more vigilant in the future. If you can identify specific areas that require improvement (vocabulary, grammar, tense usage, etc.), it is easier to create an action plan that will give positive results.

For example, if you identified that you have issues with grammar, your action plan can include using grammar tools like Wordtune when writing, and spending time studying grammar rules. You’ll quickly start to see progress when you have a defined plan to stick to.

Celebrate your successes as you go along and remember that progress takes time. Practice self-compassion and understand that setbacks are part of the journey. Above all, stay focused and don't give up. Continuously remind yourself of your desired outcome, and believe in your ability to reach it. With a positive attitude, dedication and perseverance, you can overcome repeating mistakes.

6. Use an AI writing assistant to catch errors and add clarity

Writing assistants are designed to help you catch any errors you might make and improve your writing. If used correctly, it can also be a great tool for learning and improving your language skills.

The Wordtune writing assistant checks for grammar and spelling errors, and suggests ways to improve vocabulary or enhance fluency. Paying attention to these suggestions will teach you how to add clarity to your writing and perfect it. It’s also incredibly useful if you are writing something important that you want to make sure is error-free.

7. Keep it simple (but not stupid)

It’s easy to make the common mistake of writing long sentences or repeating the same points over and over. Remember to keep your writing simple and to the point. This doesn’t mean to “dumb down” the writing, but to remove any unnecessary words or repetitions.

Even seasoned writers often overwrite, redundantly expanding on the same points. Wordtune’s shorten feature suggests ways to cut down on the number of words in your sentences to improve your writing. This helps you get straight to the point and keeps your writing clear.

Use Wordtune’s Spices feature to expand on short ideas and points in your writing. This handy feature gives you several options to choose from: continue writing, explain, emphasize, expand on, give an example, or counterargument. There are also options for adding in statistics, inspirational quotes, definitions, or even adding in a joke! It’s a great tool for anyone suffering from writer’s block (we’ve all been there).

If you’re struggling to articulate yourself, Spices enhances your writing quickly and easily. Using AI technology, Wordtune comes up with suggestions based on the text provided. You can then accept suggestions or request new ones. Pay attention to the suggestions and how sentences are formulated to flow with the natural rhythm of your writing. Perfect when you’re feeling a bit stuck or struggling to articulate yourself, Spices helps you focus on getting the task at hand done, while also helping you improve your writing skills.

Conclusion

Improving your language skills takes time. Immersing yourself in English as much as possible is a quick way to pick up the language and build your writing skills. However, it’s important to remember that making mistakes is part of the process, too. Asking your friends to correct your written English and taking advantage of AI writing assistants like Wordtune will help you improve your writing.

Although it can be challenging, through diligent practice and taking every opportunity to learn, improve, and develop, you’ll be an English language pro in no time.

Share This Article:

%20(1).webp)

8 Tips for E-commerce Copywriting Success (with Examples!)

.webp)

The Brand Strategy Deck You Need to Drive Social Media Results + 5 Examples

Grammarly Alternatives: Which Writing Assistant is the Best Choice for You?

Looking for fresh content, thank you your submission has been received.

10 ways for non-native speakers of English to develop scientific writing skills

English is not your mother tongue and it makes you feel overwhelmed in grad school? You need to read & write in English, but feel insecure about it? Reading seems to take ages and you are dreading the time when you have to start writing up your results… But don’t despair! Follow these 10 tips and develop your English writing skills “on the side”, as you go about your everyday research work.

Conducting research in a foreign language is not easy. Yet you are not alone in this. For most researchers in the world English is not their first language. The same is true for me: English is not even my second, but a third language. But I managed to get to a proficient level, and you can manage, too!

Here I introduce my best tips that will help you develop your ESL (English as a second language) writing skills casually, without too much effort. Especially if you start early in grad school, before there are any important texts to be written.

1. Practice regularly

The key to developing your English writing skills is to practice English as much as possible, in all the different modalities : read anything that interests you (from blog posts to books), watch films, listen to podcasts, contribute to online discussions, and especially: talk. Talk to your foreign friends, help tourists in the city, whatever comes to your mind and sounds like fun to you. Yes, fun is an important part of effective learning, so don’t make your English practice a chore!

This main principle has a second part, and that is regularity . If you want to learn or achieve something effectively, it’s best to create habits and routines for your practice. These give you regularity and help you avoid the internal struggles to actually do what you intend.

2. Read a lot and take notes

Reading a lot of relevant research articles is a fundamental element for everyone who wants to develop their scientific writing skills, whether they are native speakers or not. It allows you to build (passive) vocabulary and (implicit) knowledge about grammar and style .

To intensify the gains, take notes : summarize the relevant information and your thoughts about it. When you come across an especially well-worded passage, you can retype it — this also contributes to your learning. Just don’t forget to include the passage in quotation marks to avoid plagiarism if you later want to reuse your notes 😉

To establish reading and note taking as a regular habit , you can aim for reading at least 1-2 papers weekly, ideally setting a concrete day and time for it. For example, you could decide that you won’t leave home on Friday until you have finished reading your selected papers.

3. Freewrite daily in English

One way how to integrate freewriting into your daily routine is to use it as a brain dump at the beginning of your work day. Here, you set up a timer for 10 minutes and just write whatever is on your mind. When there are no personal issues on your mind that “want” to be discussed, use this writing time to think about the day that is coming, about what you want to do and how to best approach it. This will clear your head and prepare you for work. Such a freewriting session is also a great warm-up when you need to write something relevant.

An additional option is to use the variations of freewriting — focused freewriting and loop writing — to freewrite on a topic relevant to your research. Such thinking in writing not only benefits your writing skills, but it will also help to advance your research!

4. Avoid translating — learn to think in English

If you want to become proficient in a foreign language, it is essential that you avoid translating from your mother tongue for both speaking and writing. Because a 1:1 translation is rarely possible, which results in a situation where you have clear ideas in mind but can’t express them in English well. Instead of translating, you need to learn to formulate your thoughts directly in English .

Yes, this is possible even if your vocabulary is limited — and freewriting helps you get there. Since the basic idea of freewriting is to write without stopping, if you want to freewrite in English you have no choice but to think directly in English. At the beginning, the text you produce will sound as if it was written by an eight-year-old: simple language, broken sentences and bad grammar. Don’t worry about it! It will improve quickly when you practice daily, I promise 🙂

5. Talk frequently to your foreign colleagues

Besides reading English research papers and writing in English (about your research), you also want to talk regularly about your research — In English, of course. Here, the best conversation partners for you are your colleagues who don’t speak your mother tongue .

The simplest possibility for regular discussions might be a joint lunch break . If your group is not doing it yet, you could try to establish a group lunch at least once a week. Other possibilites to spend more time with your colleagues include after-work beer or sport activities. Additionally, I suggest to accept all those birthday party invitations from your colleagues you are often passing on because you are busy, tired, or simply don’t feel like attending.

When you are together with your colleagues, the discussions typically move from small talk to your research projects or general science stuff. This can be pretty interesting, even fun, especially when you are relaxed and outside of your work environment.

Do you need to revise & polish your manuscript or thesis but don’t know where to begin?

Get your Revision Checklist

Click here for an efficient step-by-step revision of your scientific texts.

6. Take an English language class

If you struggle a lot with reading research articles and communicating with your colleagues, you should consider taking an English language class to build basic language skills . First, check whether your university is offering English courses for researchers, these are ideal as they are focused on topics relevant for your work.

But don’t be too critical with yourself: once you don’t have problems with understanding research papers from your field, and others seem to understand what you say in English, you don’t need basic language classes… Then you are ready to proceed on your own, using all the other tips from this article.

7. Don’t obsess with grammar — but use reference resources when needed

Learn the basics of English, but don’t obsess with grammar! You don’t need to know all the rules before you start writing. When you follow the steps 2 + 3, and read & freewrite regularly, you will “assimilate” the necessary language knowledge without much effort — pretty much like children learning their native language. This gives you much more solid knowledge than what you can memorize from books.

That said, it’s not a bad idea to use books and other resources as a reference , to consult them as the need arises. Here a couple of recommendations:

- Grammarly blog , especially its handbook containing well-structured information on grammar, punctuation, mechanics (abbreviations, compound words, etc.), techniques (idioms, similes, etc.) and style (passive voice, paralellisms, etc.)

- The Punctuation Guide , an online resource discussing in detail the usage of all kinds of punctuation marks (hyphens and dashes, parentheses, etc.).

- Strunk & White: The Elements of Style , a little book containing condensed advice on writing style (rules of usage, principles of composition, misused words and expressions, etc.). Style is something more relative than grammar (yet still important). So there is no need to follow all the suggestions blindly, especially where your field seems to be following a different convention…

- Glasman-Deal: English Research Writing for Non-Native Speakers of English , a book that takes you section by section through writing a scientific research paper, providing for each section relevant info and exercises on grammar and language usage conventions.

8. Don’t worry about language when writing a first draft

If your English language skills are not perfect, it is tempting to evaluate the grammar, spelling, etc. of your text as you produce it. But I strongly suggest to avoid considering the language aspect of your writing when working on a first draft. In other words, avoid drafting & revising at the same time because these two processes have completely opposite requirements on your mind.

So write a draft first, then revise & improve it. And when you revise , don’t start with the language level: consider content and structure first . This allows you to write better texts faster and possibly even enjoy yourself along the way 😉

9. Ask your peers for text feedback

Getting peer feedback on your texts is a powerful way how anyone can improve their writing skills. If English is not your mother tongue, ask a native-speaker colleague for feedback specifically on the language level . Before you ask for this feedback, polish your text by yourself as much as you can. Then what your colleague points out are gaps in your English language skills.

Pay special attention to recurring mistakes you make. You can collect them in a dedicated document which you can use as a checklist when polishing your texts.

10. See it as your strength

This is a good thing for scientific writing! Because the topics we write about are complex, simple language helps others understand what we mean . With a limited vocabulary, it’s also easier to see whether what we write is clear . Furthermore, don’t forget that most of the readers of your research articles are also non-native speakers. They will surely appreciate the simple language you are using 😉

You can do it!

If you follow these ten tips and practice regularly , you will soon see your English writing skills improving. This increases your motivation to continue with these activities, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of progress . And before you know it, you will feel much more confident to talk and write about your research in English than in your mother tongue 😉

Do you know any tips or tricks that have helped you improve your English writing skills? Please, share them with us in the comments!

Do you need to revise & polish your manuscript or thesis but don’t know where to begin? Is your text a mess and you don't know how to improve it?

Click here for an efficient step-by-step revision of your scientific texts. You will be guided through each step with concrete tips for execution.

Diese Webseite verwendet Cookies, um Ihnen ein besseres Nutzererlebnis zu bieten. Wenn Sie die Seite weiternutzen, stimmen Sie der Cookie-Nutzung zu.

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

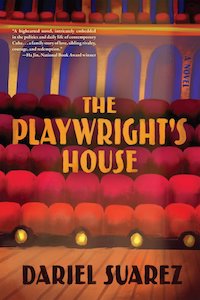

On a Non-Native English Speaker’s Creative Journey to Authenticity

Dariel suarez considers language is a vehicle for culture.

As an undergraduate creative writing student, one piece of feedback kept appearing on the margin of my stories: awkward phrasing. Red markings littered my pages, arrows pointing every which way, words circled or crossed out, re-written passages squeezed between lines. As a result, I began to obsess over language. I read contemporary fiction by American-born writers, particularly those known for their stylistic prowess. I pilfered and repurposed any metaphor or descriptive passage I found appealing. I made and frequently updated lists of words to use in my stories. I carried a modern thesaurus and dictionary everywhere and actively avoided the kind of outdated language found in classic literature—you know, the one that had gotten me into writing in the first place.

After three years of this and getting into an MFA program, the feedback remained: your phrasing is awkward . By then, I’d developed a bit of a complex. When asked about my biggest area of weakness, my fixed answer became “language.” It wasn’t a huge confidence boost to admit this. The whole enterprise of being a good writer, it seemed to me, hinged on that very thing: your ability to successfully string just the right words together. I tried camouflaging my insecurities by claiming that conflict and plot were more important. Secretly, though, I felt profound envy for the writers who seemed naturally gifted at wielding evocatively inventive sentences at every turn.

Then, during workshop one night, a professor praised the supposed awkwardness of my style as something worthy of embrace. “Nurture it as your own,” he said after class. Suddenly, I realized what lay at the heart of my struggle. I was aiming to please an audience whose native language and cultural experience were fundamentally different from mine. No matter how much I tried, the result would be artificial, clunky, detached from the reality and sensibility driving my fiction.

I didn’t learn to speak English until I was 15 years old. The authors whose books led me to write were Latin American and Russian. My stories were set in Cuba, where I grew up. In essence, my writing was an act of literal and cultural translation. A new path opened for me the instant I recognized this. I began to incessantly read contemporary works in translation. I rediscovered the sort of global literature that had inspired me to draft my first few stories. I found authors from South Africa, Nigeria, Colombia, Mexico, Argentina, China, and Korea who were engaging with place the way I wished to—with uncompromising authenticity. Their style, or that of their translators, would’ve been tagged as awkward in my classes.

Following the completion of my MFA, I committed to two projects: a story collection and a novel, both set in Cuba. My language, I decided, would remain “awkward.” Which, in practice, simply meant I would prioritize the cultural authenticity and idiosyncrasy of my characters over any American reader. Immediately, I experienced a level of freedom and confidence I hadn’t felt before.

At the same time, a new set of obstacles appeared. How could I remain true to a people and culture in a language that wasn’t theirs? What would I do when something was untranslatable? How much Spanish should there be in the writing? To what extent would I be willing to compromise for the sake of clarity or familiarity, especially at key moments in the story? The incessant wrestling with these questions could have a detrimental or even stifling effect if the answers weren’t clear.

Thus, I established a set of craft parameters I use to this day. The first is to use Spanish whenever a word or phrase would be severely undermined by translation. For instance, certain idiosyncratic Cuban expressions just wouldn’t have the same impact in English.

“!Carajo!” “Me cago en diez,” “Tremenda muela,” “Tírame un cabo”: there’s no way to translate these without losing the essence of the original. Therefore, if I choose to include them, instead of offering an immediate translation, I focus on placement and rely on the context and tone of the narrative for the reader to get what’s necessary.

Then there are the cultural references unique to a country or region. Having to constantly explain the context for a detail, setting, or circumstance—especially if it doesn’t deepen or complicate the story—is ultimately a burden for both writer and reader. I find it more effective to weave these types of references into the conflict and stakes.

If their inclusion is indispensable to the arc of the story, readers are more likely to experience them as an earned and authentic element, even if they don’t have the full picture. Being intentional and thorough in this area can also help avoid gratuitous or stereotypical details. The more deeply embedded your socio-cultural references are, the more you force yourself to genuinely engage with them and interrogate their usage.

Finally—though I’m writing in English to a largely American audience—everything happening in my work exists outside that language and country, and my job shouldn’t be catering to them. Instead, I need to honor my characters’ plight, respect the specificity of my characters’ experiences and culture, prod and get at some sort of complex truth in the context of the place they’re inhabiting and the forces they’re facing.

Language is a vehicle, the lens through which my reader can follow along. I have to tend to it, ensure it is effective and compelling. But it is in the authenticity of a story’s central conflict and its layered characters that I want my reader to connect and become invested. In order to achieve this, my language should be a reflection of my characters’ world and sensibilities, even if at times it might seem strange or awkward to someone not familiar with it.

None of the above are hardened rules, of course. If there’s something writers know to dwell in, it’s contradiction. I go through my fair share of concessions when it comes to language. There are enough nuances in every single sentence to render my decision-making process difficult and occasionally inconsistent; I’m not too hard on myself when I have to compromise.

But I’m always interrogating what ends up on the page, asking myself what my characters would think if they saw their own words and thoughts and actions depicted in a different tongue. It is exhausting work, no doubt, writing in-between two languages, the relentless effort of translating. It is also immensely rewarding to complete something which feels authentic and doesn’t water down, exploit, or demean your native home.

Now that I’m a writing instructor, I get asked about avoiding stereotypes and exoticism. I must admit the question frustrates me. If you’re asking, part of me thinks you’ve already failed. Not a generous response, I know, but some of the most critical responsibilities of a writer are to imagine, to dig, to engage, to persistently interrogate. We have to move past the obvious and recognizable. We have to avoid reducing characters and places to a few descriptors or buzzwords presented in a different language. We have to challenge our audience and not just pander to them. The same goes for ourselves.

In my most vulnerable moments, I still question the clarity of my style. I’ll read sentences out loud several times. I worry some readers will be confused by a word choice, even if it’s loyal to its linguistic and cultural source. The longwinded nature of Spanish betrays me more often than I’m willing to admit. But I’ve also grown to embrace the occasional awkwardness of my phrasing, as my professor encouraged me to do. I’ve accepted that my audience, whoever that is, will see it as a sincere attempt to tell an authentic story, no matter how different from their own expectations, experiences, or world view. Ultimately, even if I fully surrendered to an Americanized, more familiar, highly stylized mode of expression in my writing, a satisfying turn of phrase would only take my characters and their complex lives so far.

__________________________________

The Playwright’s House is available from Red Hen Press. Copyright © 2021 by Dariel Suarez.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Dariel Suarez

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Jordan Kisner Talks Pain, Masculinity, and Cowboys in Chloé Zhao’s The Rider

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Dr. Karen Palmer

If you learned English as a second language and you regularly speak a language other than English, this appendix is for you. It also provides a refresher course on many of the elements in the rest of this handbook.

Parts of Speech

In English, words are used in one of eight parts of speech: noun, pronoun, adjective, verb, adverb, conjunction, preposition, and interjection. This table includes an explanation and examples of each of the eight parts of speech:

| Noun | Person, place, or thing | Wow! After the game, silly Mary ate her apples and carrots quickly. | Iowa | book | arm |

| horse | idea | month | |||

| Pronoun | Takes the place of a noun | Wow! After the game, silly Mary ate her apples and carrots quickly. | he | it | I |

| her | my | theirs | |||

| Adjective | Describes a noun or pronoun | Wow! After the game, silly Mary ate her apples and carrots quickly. | sticky | funny | crazy |

| long | cold | round | |||

| Verb | Shows action or state of being | Wow! After the game, silly Mary ate her apples and carrots quickly. | run | jump | felt |

| think | is | gone | |||

| Adverb | Describes a verb, another adverb, or an adjective and tells how, where, or when something is done | Wow! After the game, silly Mary ate her apples and carrots quickly. | slowly | easily | very |

| often | heavily | sharply | |||

| Conjunction | Joins words, phrases, and clauses | Wow! After the game, silly Mary ate her apples and carrots quickly. | and | because | but |

| since | or | so | |||

| Preposition | First word in a phrase that indicates the relationship of the phrase to other words in the sentence | Wow! After the game, silly Mary ate her apples and carrots quickly. | in | on | to |

| after | at | over | |||

| Interjection | A word that shows emotion and is not related to the rest of the sentence | Wow! After the game, silly Mary ate her apples and carrots quickly. | Hey | Wow | Look |

| Super | Oh | Yuck |

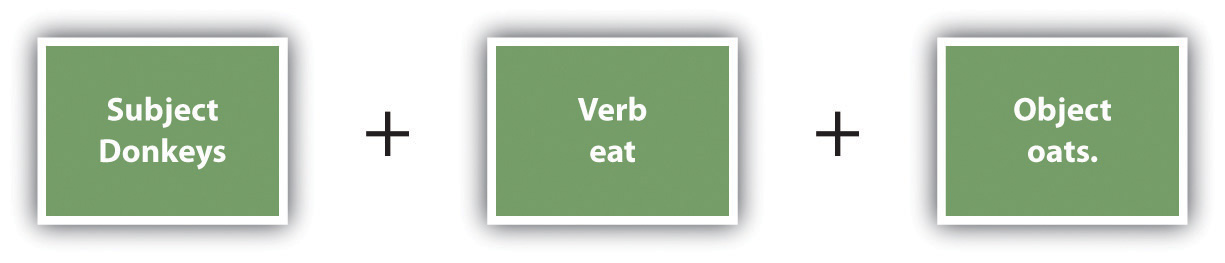

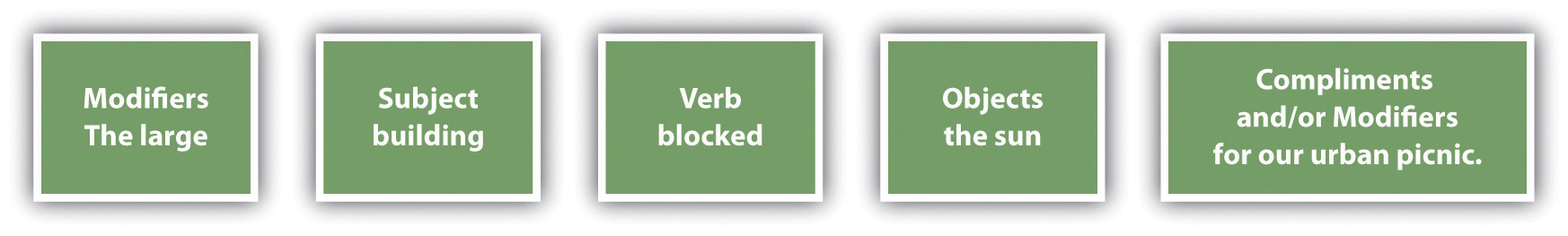

English Word Order

The simplest level of English word order within a sentence is that subjects come first followed by verbs and then direct objects.

When you have more complicated sentences, use the following general order.

When an English sentence includes more than one adjective modifying a given noun, the adjectives have a hierarchy you should follow. You should, however, keep a string of adjectives to two or three. The example includes a longer string of adjectives simply to clarify the word order. Using this table, you can see that “the small thin Methodist girl…” would be correct but “the young French small girl…” would be incorrect.

Some languages, such as Spanish, insert “no” before a verb to create a negative sentence. In English, the negative is often indicated by placing “not” after the verb or in a contraction with the verb.

I can’t make it before 1:00 p.m.

Incorrect example: I no can make it before 1:00 p.m.

Count and Noncount Nouns

Nouns that name separate things or people that you can count are called count nouns. Nouns that name things that cannot be counted unless additional words are added are called noncount nouns. You need to understand count and noncount nouns in order to use the nouns correctly with articles, in singular and plural formations, and in other situations. Some nouns can serve as either count or noncount nouns.

Examples of Count Nouns

- leaf (leaves)

Examples of Noncount Nouns

- information

Examples of Nouns That Can Be Either Count or Noncount Nouns

- baseball (play baseball vs. throw a baseball)

- love (He is my love! vs. two loves: poetry and basketball)

- marble (play with a marble vs. a floor made of marble)

In English, nouns are identified or quantified by determiners. Articles, such as a , an , and the , are one type of determiner. Use the following guidelines to alleviate confusion regarding whether to use an article or which article to use.

- Use a and an with nonspecific or indefinite singular count nouns and some proper nouns where you do not have enough information to be more specific. Use a before nouns beginning with a consonant sound and an before nouns beginning with a vowel sound.

I have a dog at home, also. (The word “dog” is a nonspecific noun since it doesn’t refer to any certain dog.)

(before a vowel): Carrie gave everyone an apple at lunch.

(before a consonant; with proper noun): He was wearing a Texas shirt.

- Use every and each with singular count nouns and some proper nouns.

I heard every noise all night long.

I tried each Jell-O flavor and liked them all.

- Use this and that with singular count and noncount nouns.

(with count noun): I am going to eat that apple .

(with noncount noun): I am not too excited about this weather .

- Use any , enough , and some with nonspecific or indefinite plural nouns (count or noncount).

I didn’t have any donuts at the meeting because he ate them all.

Do you have enough donuts for everyone?

He ate some donuts at the meeting.

- Use (a) little and much with noncount nouns.

I’d like a little meatloaf , please.

There’s not much spaghetti left.

- Use the with noncount nouns and singular and plural count nouns.

(with noncount noun): The weather is beautiful today.

(with singular count noun): Who opened the door ?

(with plural count noun): All the houses had brick fronts.

- Use both , (a) few , many , several , these , and those with plural count nouns.

I have a few books you might like to borrow.

Daryl and Louise have been traveling for several days .

Are those shoes yours?

Singulars and Plurals

English count nouns have singular and plural forms. Typically, these nouns are formed by adding – s or – es . Words that end in – ch , – sh , or – s usually require the addition of – es to form the plural. Atypical plurals are formed in various ways, such as those shown in the following table.

| Singular Nouns | Plural Nouns |

|---|---|

| dog | dogs (- added) |

| table | tables (- added) |

| peach | peaches (- added) |

| wish | wishes (- added) |

| kiss | kisses (- added) |

| man | men (atypical) |

| sheep | sheep (atypical) |

| tooth | teeth (atypical) |

| child | children (atypical) |

| alumnus | alumni (atypical) |

| leaf | leaves (atypical) |

Proper nouns are typically either singular or plural. Plural proper nouns usually have no singular form, and singular proper nouns usually have no plural form.

| Singular Proper Nouns | Plural Proper Nouns |

|---|---|

| Kentucky | Sawtooth Mountains |

| Alex |

Noncount nouns typically have only one form that is basically a singular form. To quantify them, you can add a preceding phrase.

| Noncount Nouns | Sentences with Noncount Nouns and Quantifying Phrases |

|---|---|

| gas | We put twelve gallons of gas in the car this morning. |

| anguish | After years of anguish, he finally found happiness. |

Verb Tenses

You can practice conjugating many English verbs to increase your awareness of verb tenses. Use this format for the basic conjugation:

- I laugh at Millie.

- You laugh at Millie.

- He/She/It laughs at Millie.

- We laugh at Millie.

- They laugh at Millie.

You can also practice completing these five forms of English. A mixture of tenses is used to show that you can practice the different forms with any tense.

Affirmative Usage

- I play ball.

- You play ball.

- She plays ball.

- We play ball.

- They play ball.

Negative Usage

- I do not play ball.

- You do not play ball.

- She does not play ball.

- We do not play ball.

- They do not play ball.

Yes/No Questions

- Do you play ball?

- Does she play ball?

- Do we play ball?

- Do they play ball?

Short Answers

- Yes, she does.

- No, they do not.

- No, you do not.

Wh- Questions

- Who is she?

- Where did you find it?

- When are you coming?

- Why won’t it work?

- What are you going to do?

Correct Verbs

People who are new to English often experience confusion about which verb forms can serve as the verb in a sentence. An English sentence must include at least one verb or verb phrase and a tense that relays the time during which the action is taking place. Verbals (such as gerunds and infinitives) should not be confused with verbs.

- A sentence with a gerund must also have another verb.

Correct example: Roger enjoys driving the RV.

Incorrect example: Roger driving the RV.

- A sentence with an infinitive must have another verb.

Correct example: Kyle decided to write a long message.

Incorrect example: Kyle to write a long message.

- Verbs must match the timing indicated by the other words in a sentence.

Past tense correct example: Yesterday, I called you at 5:00 p.m.

Past tense incorrect example: Yesterday, I call you at 5:00 p.m.

Future tense correct example: The next time it rains, I will bring my umbrella.

Future tense incorrect example: The next time it rains, I bring my umbrella.

Present tense correct example: Come in and get warm.

Present tense incorrect example: Come in and got warm.

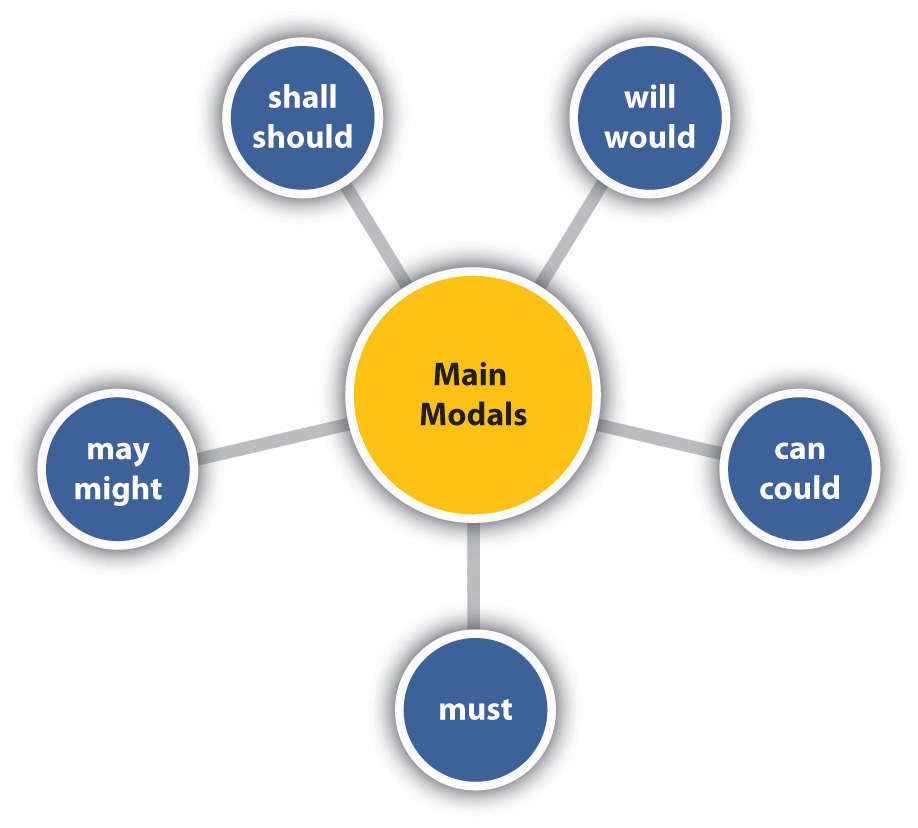

Modal Auxiliary Verbs

The English language includes nine main modal auxiliary verbs that are used with other verbs. These modals, shown in the wheel in four pairs and a single, can refer to past, present, or future tense based on the verbs that are used with them. The modals themselves do not change form to change tense. As shown in the following table, you can use modals to express an attitude in regard to the action or general situation of the sentence.

| Modal Function | Format for Present or Future Tense | Format for Past Tense |

|---|---|---|

| Advisability | or + base verb | or + + past participle |

| You the time to visit Yellowstone. | You the time to visit Yellowstone. | |

| Capability | , , , or + base verb | , , + base verb or past participle |

| Aisha you who was at the party. | Saul on the beam without falling off. | |

| Deduction | , + base verb | + + |

| Hank Spanish and French. | Lucy through the night. | |

| Forbiddance | + not + base verb | N/A |

| You his food. | ||

| Expectation | + base verb | + have + past participle |

| The sun about 7:15 today. | The boys their ball game by now. | |

| Intention | or + base verb | + base verb |

| I you at the theater. | I said I sometime today. | |

| Necessity | or + base verb | + base verb |

| I cleaning before they arrive. | Greg gas before we started the trip. | |

| Past habit | N/A | or + base verb |

| When I worked there, I at Marvy’s every day. | ||

| Permission request | , , , or + base verb (in question format) | or + base verb |

| I with you? | My parents said I their car next week. | |

| Polite request | or + base verb (in question format) | N/A |

| you please me page 45? | ||

| Possibility/uncertainty | or + base verb | + + past participle |

| Alice at work by 6:00 a.m. | I don’t remember, but I the one sitting next to him that night. | |

| Speculation | , , or + base verb | , , or + + past participle |

| If he conditions enough, he his race. | There some real money in that deal we almost made. |

Gerunds and Infinitives

Gerunds are nouns formed by adding – ing to a verb, such as running . Infinitives are nouns formed from the “to” form of a verb, such as to run . These two noun forms are called verbals, because they are formed from verbs. Experience with English will teach you which form to use in which situation. In the meantime, the following lists provide a brief overview.

Verbs That Should Be Followed Only by Gerunds and Not by Infinitives

These Verbs Could Fill This Blank: _______ Walking

Verbs That Should Be Followed Only by Infinitives and Not by Gerunds

These Verbs Could Fill This Blank: ________ to Walk

Verbs That Can Be Followed by Either Gerunds or Infinitives

These Verbs Could Fill Either of These Blanks: ________ Walking or ________ to Walk

- can(’t) afford

- can(’t) bear

Forming Participles

Participles are verb forms that combine with auxiliary verbs to create different tenses.

To form perfect tenses , use had , has , or have with the past participle.

Example: My dog has eaten twice today.

To form progressive tenses , use a form of the verb to be with the present participle, or gerund.

Example: My dog is eating a treat.

To write in passive voice , use a form of the verb to be with the past participle.

Example: The treat was eaten by my dog.

Adverbs and Adjectives

Adverbs often end in – ly and modify verbs, other adverbs, and adjectives. As a rule, you should place an adverb next to or close to the word it modifies, although adverbs can be placed in different positions within a sentence without affecting its meaning.

Before the verb: “He slowly walked to the store.”

After the verb: “He walked slowly to the store.”

At the beginning of the sentence: “ Slowly , he walked to the store.”

At the end of the sentence: “He walked to the store slowly .”

Between an auxiliary and main verb: “He was slowly walking to the store.”

Some adverbs, however, have a different meaning based on where they are placed. You should check to make sure that your placement carries the intended meaning.

“She only loved him.”

Translation: “The only emotion she felt toward him was love.”

“ Only she loved him.”

Translation: “The only person who loved him was her.”

“She loved only him.” or “She loved him only .”

Translation: “The only person she loved was him.”

Some adverbs simply do not work between the verb and the direct object in a sentence.

Acceptable adverb placement: She barely heard the noise.

Unacceptable adverb placement: She heard barely the noise.

Adjectives modify nouns and in some more heavily inflected languages, the endings of adjectives change to agree with the number and gender of the noun. In English, adjectives do not change in this way. For example, within the following sentences, note how the spelling of the adjective “eager” remains the same, regardless of the number or the gender of the noun it modifies.

The eager boy jumped the starting gun.

The eager boys lined up.

The eager girls eyed the starter.

As in these sentences, adjectives usually are placed before a noun. The noun can be the subject, as in the preceding example, or a direct object, as in the following sentence.

Adjectives can also be placed after a linking verb. The adjective still modifies a noun but is not placed next to the noun, as in the following example.

When two or more adjectives are used to modify a single noun, they should be used in a set order. Even though the table shows ten levels within the hierarchy, you should limit your adjectives per noun to two or three.

Hierarchical Order of Adjectives

| The | pretty | small | thin | young | white | French | Methodist | plastic | girl |

When using an adverb and adjective together with a noun, you should typically place the adverb first, followed by the adjective, and then the noun.

Irregular Adjectives

In English, adjectives have comparative and superlative forms that are used to more exactly describe nouns.

Joey is tall , Pete is taller than Joey, and Malik is the tallest of the three boys.

One common way to form the comparative and superlative forms is to add – er and – est , respectively, as shown in the preceding example. A second common method is to use the words more and most or less and least , as shown in the following example.

Some adjectives do not follow these two common methods of forming comparatives and superlatives. You will simply have to learn these irregular adjectives by heart. Notice that some are irregular when used with a certain meaning and not when used with a different meaning.

Sample Adjectives That Form Superlatives Using Irregular Patterns

| much (noncount nouns) | more | most |

| many (count nouns) | more | most |

| little (size) | littler | littlest |

| little (number) | less | least |

| old (people and things) | older | oldest |

| old (family members) | elder | eldest |

Some adjectives’ comparatives and superlatives can be formed with either – er and – est or with more and most (or less and least ). In these cases, choose the version that works best within a given sentence.

Sample Adjectives That Can Form Superlatives Using – er and – est or More and Most

| clever | cleverer | cleverest |

| clever | more clever | most clever |

| gentle | gentler | gentlest |

| gentle | more gentle | most gentle |

| friendly | friendlier | friendliest |

| friendly | more friendly | most friendly |

| quiet | quieter | quietest |

| quiet | more quiet | most quiet |

| simple | simpler | simplest |

| simple | more simple | most simple |

Some adjectives do not have comparative and superlative forms since the simplest form expresses the only possible form.

Sample Adjectives That Do Not Have Comparative and Superlative Forms

Indefinite adjectives.

Indefinite adjectives give nonspecific information about a noun. For example, the indefinite article few indicates some, but not an exact amount. Indefinite adjectives are easily confused with indefinite pronouns since they are the same words used differently. An indefinite pronoun replaces a noun. An indefinite adjective precedes a noun or pronoun and modifies it. It is important for you to understand the difference between indefinite adjectives and pronouns to assure you are saying what you mean. Some common indefinite adjectives include all , any , anything , each , every , few , many , one , several , some , somebody , and someone .

Indefinite adjective: We are having some cake for dessert.

Indefinite pronoun: I like cake. I’ll have some , please.

Indefinite adjective: You can find a state name on each quarter.

Indefinite pronoun: I have four Illinois quarters, and each is brand new.

Predicate Adjectives

Since linking verbs express a state of being instead of an action, adjectives are used after them instead of adverbs. An adjective that follows a linking verb is referred to as a predicate adjective . Be careful not to use an adverb simply because of the proximity to the verb.

Correct (adjective follows linking verb): Kelly is selfish.

Incorrect (adverb follows linking verb): Kelly is selfishly.

Correct (adjective follows linking verb): Beth seems eager.

Incorrect (adverb follows linking verb): Beth seems eagerly.

Linking Verbs That Can Be Followed by Adjectives

Clauses and phrases.

Clauses include both subjects and verbs that work together as a single unit. When they form stand-alone sentences, they’re called independent clauses. An independent clause can stand alone or can be used with other clauses and phrases. A dependent clause also includes both a subject and a verb, but it must combine with an independent clause to form a complete sentence.

| Types of Dependent Clauses | Descriptions | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Adverb clause | Serves as an adverb; tells when, how, why, where, under what condition, to what degree, how often, or how much | , she plastered her body with sunscreen. |

| Noun clause | Serves as a noun when attached to a verb | seemed quite likely. |

| She thought . | ||

| Adjective clause (also called a relative clause) | Begins with a relative pronoun ( , , , , ) or a relative adverb ( , , ); functions as an adjective; attaches to a noun; has both a subject and a verb; tells what kind, how many, or which one | The day was an unlucky day.* |

| The house is gone. | ||

| Appositive clause | Functions as an appositive by restating a noun or noun-related verb in clause form; begins with ; typical nouns involved include possibilities such as assumption, belief, conviction, idea, knowledge, and theory | The idea is crazy. |

| *In some instances, the relative pronoun or adverb can be implied (e.g., “The day was an unlucky day”). | ||

Phrases are groups of words that work together as a single unit but do not have a subject or a verb. English includes five basic kinds of phrases.

| Types of Phrases | Descriptions | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Noun phrase | Multiple words serving as a noun | Darcy ate . |

| Verb phrase | Used as the verb in sentences that are in the progressive and perfect tenses | The class a half-hour earlier. |

| Prepositional phrase | Begins with a preposition | Work will be easier . |

| Adjective phrase | Functions as an adjective; might include prepositional phrases and/or nouns | My brother is . |

| Adverb phrase | Functions as an adverb; might include prepositional phrases and/or multiple adverbs | Let’s go walking . |

| Ignacia walked . |

Relative Pronouns and Clauses

An adjective clause gives information about a preceding noun in a sentence. Look at the following examples.

The car that Richie was driving was yellow.

Des Moines, where I live , is in Iowa.

Mr. Creeter, whose brother I know , is the new math teacher.

Like many other adjective clauses, these begin with a relative adjective ( which , who , whom , whose , that ) or a relative adverb ( when or where ). When you use a relative clause to describe a noun, make sure to begin it with one of the seven relative adjectives and adverbs listed in the previous sentence.

Prepositions and Prepositional Phrases

Prepositions are words that show the relationships between two or more other words. Choosing correct prepositions can be challenging, but the following examples will help clarify how to use some of the most common prepositions.

| Types of Prepositions | Examples of Prepositions | How to Use | Prepositions Used in Sentences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time | at | Use with hours of the day and these words that indicate time of day: , , , and | We will eat . |

| We will eat . | |||

| by | Use with time words to indicate a particular time | I’ll be there . | |

| I’ll be finished . | |||

| in | Use with and these time-of-day words: , , and | We’ll start . | |

| Use on its own with months, seasons, and years | The rainy season starts . | ||

| on | Use with days of the week | I’ll see you . | |

| Location | at | Use to indicate a particular place | I’ll stop . |

| in | Use when indicating that an item or person is within given boundaries | My ticket is . | |

| by | Use to mean “near a particular place” | My desk is . | |

| on | Use when indicating a surface or site on which something rests or is located | Place it , please. | |

| My office is . | |||

| Logical relationships | of | Use to indicate part of a whole | I ate half . |

| Use to indicate contents or makeup | I brought a bag . | ||

| for | Use to show purpose | Jake uses his apron . | |

| State of being | in | Use to indicate a state of being | I am afraid that I’m . |

Omitted Words

Some languages, especially those that make greater use of inflection, do not include all the sentence parts that English includes. Take special care to include those English parts that you might not be used to including in your native language. The following table shows some of these words that are needed in English but not in other languages.

| Sentence Parts | Language Issues |

|---|---|

| Articles | Neither Chinese nor Arabic includes articles, such as and , so people with Chinese or Arabic as a first language have to take great care to learn to use articles correctly. |

| Verbs | Many languages have verb tense setups that vary from English, so most new English learners have to be very careful to include auxiliary verbs properly. For example, Arabic does not include the verb “to be,” so native speakers of Arabic who learn English have to take special care to learn the usage of “to be.” An Arabic speaker might say, “The girl happy,” instead of, “The girl is happy.” |

| Subjects | Spanish and Japanese do not include a subject in every sentence, but every English sentence requires a subject (except in commands where the subject is understood: “Go get the box”). |

| Expletives | Inverted English sentences can cause problems for many new English speakers. For example, you could say, “An apple is in the refrigerator.” But in typical English, you would more likely say, “There is an apple in the refrigerator.” This version is an inverted sentence, and “there” is an expletive. Many new English learners might invert the sentence without adding the expletive and say, “Is an apple in the refrigerator.” |

| Plurals | Neither Chinese nor Thai includes plurals, but English does. So many new English learners have to take great care to differentiate between singular and plural forms and to use them at the appropriate times. |

| Subject pronouns | In Spanish, the subject pronoun is often not used, so Spanish speakers learning English will often omit the subject pronoun, saying, “Am hungry,” instead of, “I am hungry.” |

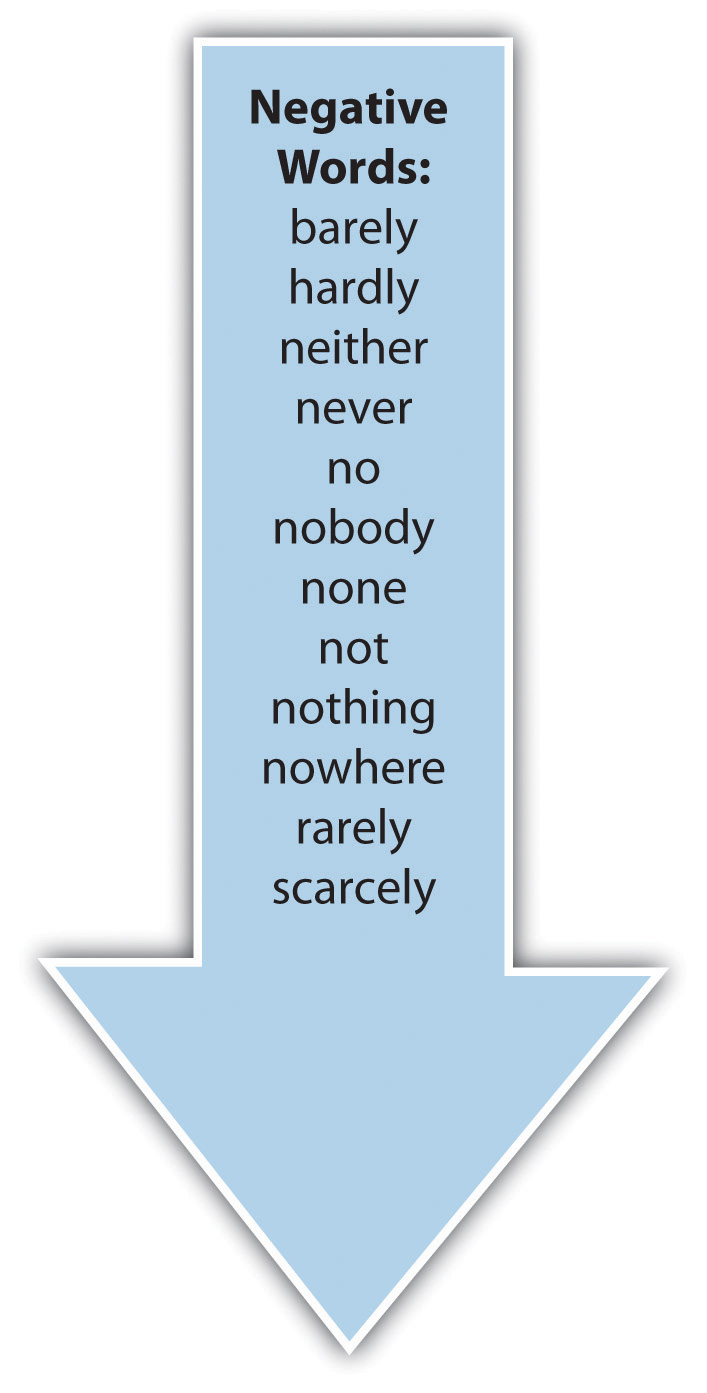

Not and Other Negative Words

To form a negative in English, you have to add a negative word to the sentence. Some of the negative words in English are shown in the blue arrow. Typically, you should place the negative word before the main verb.

I was barely awake when I heard you come home.

Kurt is not going with us.

In casual English, it is common to form contractions, or shortened combined words, with the auxiliary or linking verb and the word not . Contractions are typically not acceptable in very formal writing but are becoming more and more common in certain academic and public contexts.

I haven’t heard that before.

Jill isn’t my cousin.

Using two negative words in the same sentence changes the meaning of the negative words to positive, thus supporting the common saying “Two negatives make a positive.” Think of it as being similar to multiplying two negative numbers and getting a positive number. Double negatives are often used in extremely casual talk but never in professional or academic settings.

Correct: I didn’t hear anything.

Incorrect: I didn’t hear nothing. (The two negatives change to a positive, so the sentence technically means “I heard something.”)

Idioms are informal, colorful language. Although their intent is to add interest to the English language, they also add a lot of confusion since their intended meanings are not aligned with their literal meanings. In time, you will learn the idioms that your acquaintances use. Until then, reading lists of idioms, such as the following, might prove helpful. Just remember that when a person says something that seems to make no sense at all, an idiom might be involved. Also, keep in mind that this list is just a very small sampling of the thousands of idiomatic expressions that occur in English, as happens with any language.

| Idiom | Intended Meaning |

|---|---|

| A little bird told me. | I know some information, and I’d rather not say where I heard it. |

| Don’t count your chickens before they hatch. | Don’t decide before you have all the facts. |

| Don’t jump out of your skin. | Don’t get overly excited. |

| Go fly a kite. | What you are saying doesn’t make sense. |

| Hank’s got some major-league problems. | Hank has some serious problems. |

| Nothing ventured, nothing gained. | You can’t succeed if you don’t try. |

| People who live in glass houses should not throw stones. | You should not criticize others for faults that you also have, or since you aren’t perfect, you should not criticize others. |

| They are joined at the hip. | They are always together and/or think alike. |

| We’ve got it made in the shade. | Everything is working out just right. |

| What does John Q. Public say? | What does the average person think? |

| You’re crazy. | Your words do not make sense. |

Spelling Tips

Spelling is a vital part of your written English skills. Your spelling needs to include both an understanding of general spelling rules and a mastery of common words that you will use often. The following are some of the most common words you will need to spell listed in categories.

| Days and Months | Time | Directions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grocery Lists | General Shopping Lists | Family Words | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Services | Words for Packing to Move | Math Words | Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Holidays | Common Names | |

|---|---|---|

American Writing Styles, Argument, and Structure

Your original language has its own structures, formats, and cultural assumptions that are likely natural to you but perhaps different from those of English. The following broad guidelines underlie basic American English and US academic writing.

- Citing sources: Some languages and cultures do not consider citing sources of ideas to be of paramount importance. In US academic situations, however, failing to cite sources of ideas and text is referred to as plagiarism and can result in serious ramifications, including failing grades, damaged reputations, school expulsions, and job loss.

- Introducing the topic early: Unlike some languages, American English typically presents the topic early in a paper.

- Staying on topic: Although some languages view diversions from the topic as adding interest and depth, American English is focused and on topic.

- Writing concisely: Some languages hold eloquent, flowing language in high esteem. Consequently, texts in these languages are often long and elaborate. American English, on the other hand, prefers concise, to-the-point wording.

- Constructing arguments: US academic writing often involves argument building. To this end, writers use transitions to link ideas, evidence to support claims, and relatively formal writing to ensure clarity.

Attribution

- Content and images adapted from “ Chapter 21: Appendix A” and licensed under CC BY NC SA .

The RoughWriter's Guide Copyright © 2020 by Dr. Karen Palmer is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Tips for Non-Native English Writers

Read informative materials.

Make a habit of reading books, magazines, encyclopedias, academic journals – anything that can provide you with information and improve your grammar and vocabulary. The idea is to increase your knowledge with spelling usage, grammar and sentence structure. The more you read informative materials, the sooner you will understand the rules of spelling and sentence composition. Highlight words, phrases and sentences that you do not know and find their explanation in a dictionary or grammar book.

Build Your Vocabulary

Maintain a list of your own vocabulary as you read materials. Get a pen and notepad and write down words, sentences, phrases and expressions. Creating your own dictionary will allow you to refer to words and phrases that you use in your daily writing task as well as boost your confidence every time you write down the next entry in your robust list of words.

Acquire English Speaking Skills

Unless you are a good English speaker, you are not going to be a competent writer. Engage in conversation with your family, friends and colleagues and get connected with native English speakers through online chat rooms, forums and blogs. Talking with native speakers of English will allow you to speak more fluently in English. So ultimately, you will be more in control of your English writing tasks if it involves interviews and surveys in English language.

Interact With the Online Community

Maintain a personal blog where you can share your knowledge, opinions and comments on a specific topic. This is a great way to improve your writing skills while at the same time helping you connect with your target audience. Active internet readers love to read blogs and some of them are professional writers. So you will also have a chance to connect with a number of professional writers and bloggers who are native English speakers.

Writing is Rewriting

Unless you are good at revising your work, you cannot qualify as a competent writer. So edit every assignment thoroughly and divide every writing task into drafting and revising. First you will draft your initial ideas, and then revise them to make your final draft organized, polished and free from all errors related to grammar, spelling and punctuation. Always keep a grammar reference book and dictionary available while you edit or rewrite your work. Editing requires long hours of revision, rewording and rephrasing. Keeping the learning materials at hand will help you do the revisions in a time-efficient way.

Get Feedback from Native English Speakers

Get help from native English speakers while you write your projects. Ask for their feedback on verb usage, word selection and use of idioms. A native English speaker can also help you with the content, style and tone of your writing.

Appreciate Positive Criticism

Be open to constructive suggestions and feedback. Learning is all about accepting your mistakes in a positive spirit. Do a regular reality check and assess your writing skills based on reviews and analysis of others. You cannot improve as a writer unless you begin to be honest with yourself and identify your weak points.

You may also like:

- I Don’t Understand, Do You?

- Listen&Learn: The Berlin Wall

- 9 Online Games for English Learners

18 comments

Very helpful informative trip for everyone.

Thank you very much for such an informative article.

thanks so much for us this chance to improve oulearning skills in English language.

Finally,I have got the website for Learning English language after so much searching.Every thing I want to learn is in website..GOOD!

Very helpful article for me…thank you

I love the author of this book is names :Raghad Saleh she’s a perfect and great .View .the book are actually perfect and super

This website is very helpful! I couldn’t imagine how can I improve my English skills without using this website. English Club is the best source for us to gained knowledge about English. I have studied English using this website almost two weeks ago, and it helps me a lot!. The explanations to every material are very easy to understand, especially for beginning learners like me!. Last but not least, I wanna say thank you to all English Club’s team who work very hard to make this amazing website! I really hope this website could be develop better in the future :)

Dear, Cheryl, I’m still waiting for a feedback from you. please, Cheryl, I wish you could react to this my piece of writing or comment on your article.

Dear Cheryl. I’m happy to join Englishclub. I’m a newcomer. Please, find her my full name: Fist name Emile; Second name: Boyo;last name: PARE. Call me Emile in messages addressed to me. Cheryl, is it possible to give me ideas on how to help beginning learners involve in the writing skill? When, I say “beginning leaners” I mean REAL beginners” because we’re in a francophone country, and it ‘s the learners’contact with the English language. Can you help, Cheryl? Thanks. Emile

Very informative and help me in my writing skill. I understand almost all the words used in this article which means I know a lot of vocabaries, but when it comes to the time to express my idea in written form I got stuck. All the vocabularies I have vanish

The article is very helpful to me。I can adopt some useful sentence and idea。As a primary English learner,it is difficult for me to understand some words,but I can guess it according to the whole sentence。Cheer up!

good suggestion

Very informative and interesting tips. Thanks

i need someone to help me for speaking in english