- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

What is Transcendentalism?

- When did American literature begin?

- Who are some important authors of American literature?

- What are the periods of American literature?

Transcendentalism

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Humanities LibreTexts - Transcendentalism

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Transcendentalism

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy - American Transcendentalism

- Khan Academy - Transcendentalism (article)

- Digital History - American Transcendentalism

- The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History - Transcendentalism and Social Reform

- Transcendentalism - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- transcendentalism - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

Transcendentalism is a 19th-century movement of writers and philosophers in New England who were loosely bound together by adherence to an idealistic system of thought based on a belief in the essential unity of all creation, the innate goodness of humanity, and the supremacy of insight over logic and experience for the revelation of the deepest truths.

Which authors were attracted to Transcendentalism?

Transcendentalism attracted such diverse and highly individualistic figures as Ralph Waldo Emerson , Henry David Thoreau , Margaret Fuller , Orestes Brownson , Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, and James Freeman Clarke , as well as George Ripley, Bronson Alcott, the younger W.E. Channing , and W.H. Channing.

What inspired Transcendentalism?

The 19th-century Transcendentalism movement was inspired by German transcendentalism, Platonism and Neoplatonism, the Indian and Chinese scriptures, and also by the writings of such mystics as Emanuel Swedenborg and Jakob Böhme.

Transcendentalism , 19th-century movement of writers and philosophers in New England who were loosely bound together by adherence to an idealistic system of thought based on a belief in the essential unity of all creation, the innate goodness of humanity, and the supremacy of insight over logic and experience for the revelation of the deepest truths . German transcendentalism (especially as it was refracted by Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Thomas Carlyle ), Platonism and Neoplatonism , the Indian and Chinese scriptures, and the writings of such mystics as Emanuel Swedenborg and Jakob Böhme were sources to which the New England Transcendentalists turned in their search for a liberating philosophy .

Eclectic and cosmopolitan in its sources and part of the Romantic movement, New England Transcendentalism originated in the area around Concord , Massachusetts , and from 1830 to 1855 represented a battle between the younger and older generations and the emergence of a new national culture based on native materials. It attracted such diverse and highly individualistic figures as Ralph Waldo Emerson , Henry David Thoreau , Margaret Fuller , Orestes Brownson , Elizabeth Palmer Peabody , and James Freeman Clarke , as well as George Ripley , Bronson Alcott , the younger W.E. Channing , and W.H. Channing. In 1840 Emerson and Margaret Fuller founded The Dial (1840–44), the prototypal “little magazine” wherein some of the best writings by minor Transcendentalists appeared. The writings of the Transcendentalists and those of contemporaries such as Walt Whitman , Herman Melville , and Nathaniel Hawthorne , for whom they prepared the ground, represent the first flowering of the American artistic genius and introduced the American Renaissance in literature ( see also American literature: American Renaissance ).

In their religious quest, the Transcendentalists rejected the conventions of 18th-century thought, and what began in a dissatisfaction with Unitarianism developed into a repudiation of the whole established order. They were leaders in experimental schemes for living (Thoreau at Walden Pond , Alcott at Fruitlands, Ripley at Brook Farm ); women’s suffrage ; better conditions for workers; temperance for all; modifications of dress and diet; the rise of free religion ; educational innovation; and other humanitarian causes.

Heavily indebted to the Transcendentalists’ organic philosophy, aesthetics , and democratic aspirations were the pragmatism of William James and John Dewey , the environmental planning of Benton MacKaye and Lewis Mumford , the architecture (and writings) of Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright , and the American “modernism” in the arts promoted by Alfred Stieglitz .

Advertisement

What Is Transcendentalism and How Did It Change America?

- Share Content on Facebook

- Share Content on LinkedIn

- Share Content on Flipboard

- Share Content on Reddit

- Share Content via Email

Key Takeaways

- Transcendentalism, a mid-19th century New England philosophy, emphasized spiritual self-reliance and individualism, influencing movements for racial justice, women's rights and environmental protection in America.

- Rooted in European Romanticism and American ideals of equality, transcendentalists like Emerson and Thoreau advocated for social reform, abolition of slavery, and equality for all.

- The movement's impact extended to education, feminism and the abolitionist movement, with its ideas continuing to inspire activism and reform efforts in modern times.

Today, a lot of Americans feel strongly about issues such racial justice, women's rights and protecting the environment, and many believe in the power of nonviolent civil disobedience to achieve progress towards a better, fairer world. And while not all of them realize it, in many ways they take after a group of mid-19th century New England intellectuals such as Ralph Waldo Emerson , Henry David Thoreau and Margaret Fuller, Frederic Henry Hedge, among others, who espoused a philosophy known as transcendentalism .

What Is Transcendentalism?

Individualism and equality for all, finding community in the transcendental club & brook farm, henry david thoreau and the transcendental life, transcendentalism, feminism and the abolitionist movement.

The transcendentalist movement, which emerged in the mid-1830s early nineteenth century, had a straightforward idea at its core. The New England transcendentalism adherents argued that every person possessed the light of Divine truth and should look within himself or herself to find it, rather than simply conform to whatever the powers that be wanted them to think. But from that notion of spiritual self-reliance, a lot of other ideas blossomed, from reverence for nature to the view that everyone in America was entitled to freedom and equality. That led transcendentalists to become an important part of other activist movements in America that sought to abolish slavery and achieve women's suffrage.

It was inspired in part by thinkers on the other side of the Atlantic, like the new Biblical Criticism in Germany touted in the writings of Herder and English and German Romanticism. The actual name of the movement "transcendental," came from the Critique of Practical Reason (1788) by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant. Emerson was a great admirer of William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, both of whom he met when he traveled to Europe and helped shape his future writings. Frederick Henry Hedge, a Unitarian minister who studied in Germany and knew the German language well brought German philosophy to Americans through Hedge's Club to begin discussions of current topics through a German philosophers lens.

These emerging ideas eventually transferred over to the eastern United States, "Transcendentalism became the first distinctly American philosophy, because it fused several different currents, all of which converged only here in the U.S.," Laura Dassow Walls explains in an email. She's the William P. and Hazel B. White Professor of English at the University of Notre Dame, and author of the acclaimed 2017 biography, " Henry David Thoreau: A Life ."

"So, even though the underlying philosophy first emerged in Europe, it was in America that it took hold as a philosophy one could actually commit to and live by," she says. Emerson urged in his essay "The American Scholar" for Americans to stop looking to Europe for inspiration and imitation and to be themselves.

According to Walls, one of transcendentalism's key influences was the religious faith of New England's Puritans , who believed that every person stands before God and must read the Bible for himself or herself. "This gave us the bedrock notion of individualism ," she says.

Another important ingredient was the American Revolution , which promoted equality as an American ideal — even if the new country didn't actually afford that status to a lot of its people, including women and Blacks. "The transcendentalists, whose parents had grown up fighting the Revolution, believed it was their turn to continue the Revolution, that is, to continue the political revolution by igniting it as an intellectual revolution," Walls says. When the United States government under President Van Buren wanted to remove Cherokee from their native lands, Emerson wrote them in protest. He wanted social reform that protected the rights of all.

Those ideas mixed together with another rising early 1880s influence — European Romanticism , a literary and artistic movement that emphasized feeling and emotion rather than the Enlightenment 's emphasis on reason and order.

"All through the war years — the American Revolution , the Napoleonic Wars, the War of 1812 — Americans found it virtually impossible to go to Europe or even to access European books," Walls says. "But after the Paris peace treaty of 1815, suddenly travel to Europe was wide open again. A whole generation of ambitious young American men sailed to Europe to continue their education at European universities, above all in Germany. The books and ideas and teachings they brought back with them — Kant , Goethe , the Humboldt brothers , Samuel Taylor Coleridge , Wordsworth , Byron and Shelley , and on and on — infused American colleges and universities with an exciting new wave of European literature and philosophy ." It was "a wave which swiftly spread into the popular imagination, inspiring a widespread confidence that a new age was born, an age in which the individual could intuit truth for him- or herself by an inward search for meaning."

A small group interested in these ideas like George Putnam, Amos Bronson Alcott, Frederic Henry Hedge, and more began meeting together in the mid-1830s, first at a hotel and then in the Boston home of a minister named George Ripley , forming what became known as the Transcendental Club . The group eventually published a magazine, The Dial , which was edited by Fuller. Elizabeth Palmer Peabody was the business manager of the magazine and in 1860 established the first English-language kindergarten in the USA.

Later, some of the transcendentalists even created a short-lived utopian community in Boston based upon their ideas — Brook Farm , whose residents shared the agricultural work and operated a school.

While the transcendentalists were a rebellious fringe, a lot of their transcendental philosophy ideas eventually became an accepted part of the American mainstream. "As Emerson said, 'In self-trust, all the virtues are comprehended,'" Walls explains. "This notion of self-trust became the foundation for American self-reliance, another term coined by Emerson."

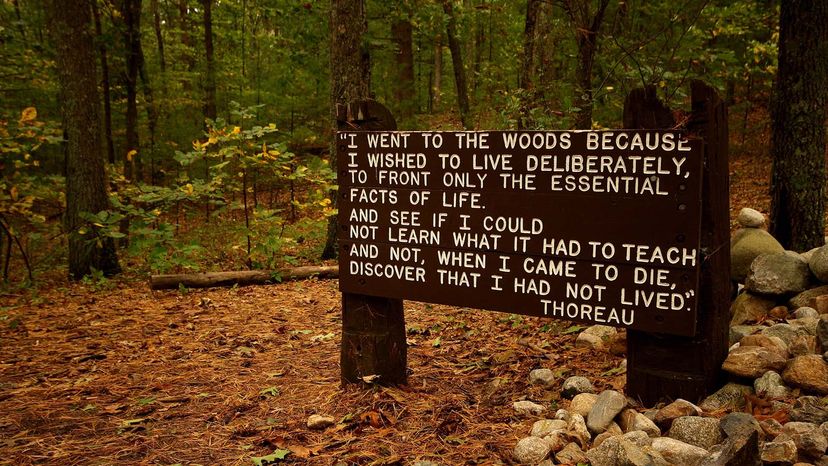

Thoreau , former schoolmaster turned poet and philosopher, bought into transcendentalist philosophy ideas and endeavored to live them. As this article from the Constitutional Rights Foundation details, in 1845, he built a cottage on Walden Pond, on property owned by Emerson, and spent several years living off the land, meditating and contemplating nature. Thoreau stopped paying his taxes in protest against legal slavery in the U.S. and the U.S. war against Mexico in 1846 . That led to him being arrested by the local constable for tax delinquency. He spent a night in jail before a benefactor paid off his debt. The experience led Thoreau to publish his influential essay " Civil Disobedience ," in which he argued that people should defy the government rather than support policies they saw as unjust. Thoreau advocated nonviolent action but later a letter in support of violent actions of John Brown, who murdered unarmed pro-slavery settlers in Kansas.

"Let every man make known what kind of government would command his respect, and that will be one step toward obtaining it," Thoreau wrote.

"Thoreau gave us the classic examples — first in his uniquely individualist form of social protest, civil disobedience, and then in pursuing his Utopian search for truth by living in solitude at Walden Pond — striking out alone to 'enjoy an original relation to the universe' as Emerson said," Walls says. "It's good to remember that this 'original relation' included the universe of human history — world literature, the world's religions, modern science, philosophy all the way back to the ancient Greeks, Plato above all — but also, famously, the universe of the outer world, or nature, which the transcendentalists regarded as the embodiment of divine reason, hence the key to universal meaning."

According to Walls, the transcendentalists "interpreted truth not as something that one could find, single and static, but as something one lived, dynamic and always evolving and changing."

That unending search for the truth also led the movement's members to become activists in big causes of their day. The transcendentalist belief that every person carries God within him or her meant that politics, economics, organized religion and the schools, with their tendency to sort people into hierarchical ranks, needed to be overhauled or at least reformed.

"The American educational system was their first target — education should be free to all, of all ages, men and women alike, and all ethnicities, races and creeds," Walls says. "Many of the transcendentalists were teachers, and several — Bronson Alcott , Elizabeth Peabody [and] Thoreau — founded innovative, progressive schools, which embraced literacy and education for everyone, including women and African Americans." Their ideas still influence education today as we all deserve access to education as human beings.

Transcendentalists also took up the fight against slavery — "led, notably, by women, who took up the cause starting in the 1830s by founding anti-slavery societies at the local level and organizing anti-slavery activism at all levels, local, regional and national," Walls explains. Emerson and Thoreau gave speeches against slavery. Another transcendentalist minister, Theodore Parker, not only preached abolitionist sermons but actually formed a vigilance committee to protect free Blacks in Boston from southern slave-catchers. "Thoreau daringly acted as a conductor on the Underground Railroad , and went on to inspire the northern movement in support of John Brown ," Walls notes.

Members of the American transcendentalism movement also were early advocates of equality for women. Margaret Fuller's 1845 book " Woman in the Nineteenth Century " contained what for the time was a daring proclamation: "What woman needs is not as a woman to act or rule, but as a nature to grow, as an intellect to discern, as a soul to live freely and unimpeded, to unfold such powers as were given her when we left our common home." Fuller's influence was felt a few years later in the Seneca Falls Convention , the 1848 conference that's widely recognized as the beginning of the women's rights movement.

The transcendentalist movement eventually began to fade in prominence, but its ideas never really went away and manifesting into later reform movements. In the 1960s and 1970s, for example, there was a resurgence of enthusiasm for Thoreau, as antiwar activists and hippies found that his ideas about resisting the power structure were relevant to them. Today, when climate activists argue that environmental protection and social justice for poor people and minority communities aren't separate issues but are actually inseparably linked, they're drawing upon Thoreau's belief that we need to get off the shoulders of others, Walls explains.

"Interest in Thoreau's ideas is stronger today than ever before; certainly students in my own classes resonate to his message more urgently than ever," Walls says. "They identify with Thoreau's fear that we're living lives of 'quiet desperation,' and many respond with intense hope to the solutions he offers. For one reason, his is an individualist form of hope; you can take on his ethical project by yourself, on your own, no matter who you are or where you live. In other words, he offers a sense that even today we can exert at least some control over our lives, learn to live by a higher ethical standard and so at the least make our own lives better — a place to start the ethical project of making all lives better."

Walden Pond, where Henry Thoreau lived for two years, also was the place where Boston entrepreneur Frederic "Ice King" Tudor harvested ice, cutting blocks and shipping them to faraway countries, according to the New England Historical Society . "Thus it appears that the sweltering inhabitants of Charleston and New Orleans, or Madras and Bombay and Calcutta, drink at my well," Thoreau wrote in 1854.

Frequently Asked Questions

How did transcendentalism influence later social reform movements, what role did women play in the transcendentalist movement.

Please copy/paste the following text to properly cite this HowStuffWorks.com article:

Philosophy Buzz

All About Philosophy

Transcendentalism – Beliefs, Principles, Quotes & Leading Figures

Transcendentalism is a philosophical movement that developed in the late 1820s and 1830s in the eastern United States.

It is grounded in the belief that individuals can transcend the physical world to reach a deeper spiritual experience through intuition and the contemplation of the natural world.

Table of Contents

Transcendentalism Meaning

At its core, transcendentalism posits that people have knowledge about themselves and the world around them that “transcends” or goes beyond what they can see, hear, touch, or feel.

World Philosophies – Unlock New Perspective for Self-Discovery, Wisdom & Personal Transformation

Available on Amazon

This idea is rooted in the inherent goodness of both people and nature.

Transcendentalists argue that society and its institutions—particularly organized religion and political parties—ultimately corrupt the purity of the individual.

They have faith that people are at their best when truly “self-reliant” and independent.

How Are Romanticism and Transcendentalism Connected?

Romanticism and Transcendentalism are closely connected, as both philosophies emphasize the importance of the individual and the individual’s relationship with the natural world.

The difference between the two lies in their view of nature.

Romanticism generally portrays nature as dark and mysterious, while Transcendentalism sees nature as a divine and universal symbol of metaphysical truth.

Beliefs & Principles of Transcendentalism

Transcendentalism holds several fundamental beliefs.

World Philosophy in a Flash – Guide to Eastern & Western Philosophies Across Cultures and Time

First, it posits that the individual is the spiritual center of the universe.

Second, not only can all individuals access an ‘inner light’ to gain an understanding of the world, but such insights transcend sensory experience and rationality.

Transcendentalists also believe in the inherent goodness of people and nature.

Lastly, they have a deep faith in self-reliance and individual intuition, both of which are pathways to achieving personal independence and realizing one’s relationship to the universe.

What is Transcendentalism? (Transcendentalism Defined, Meaning of Transcendentalism)

Tenets of Transcendentalism

Transcendentalism’s basic tenets include individualism , self-reliance, and the belief in a higher reality than that perceived by the senses.

The movement emphasizes personal intuition, freedom from social conventions, and a simple, mindful lifestyle.

It also promotes a deep connection with nature, viewing it as a direct expression of the divine.

In essence, Transcendentalists advocate for a spiritual understanding that transcends logical reasoning and empirical proof, hailing intuition and self-exploration as the means to attain such insight.

Leading Figures

Two of the leading figures of Transcendentalism were Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau.

Emerson, a former Unitarian minister, was a prolific writer and speaker, known for his essays like “Self-Reliance” and “Nature.”

His ideas and eloquent expression of Transcendentalist beliefs helped the movement gain significant influence in the mid-19th century.

Thoreau, a student and friend of Emerson, is best known for his work “Walden,” a reflection upon simple living in natural surroundings.

He embodied the Transcendentalist belief in personal freedom and non-conformity.

Ralph Waldo Emerson Transcendentalism

Ralph Waldo Emerson was a central figure in the Transcendentalist movement.

His essay , “Nature,” published in 1836, is considered the movement’s seminal work.

In it, Emerson promotes the belief that individuals can directly experience God and truth through nature.

He emphasized the idea of self-reliance, asserting that each person should avoid conformity and false consistency, and follow their own instincts and ideas.

Henry David Thoreau Transcendentalism

Henry David Thoreau is another prominent figure in the Transcendentalist movement.

He expanded upon Emerson’s ideas, particularly the relationship between the self and nature.

Thoreau’s famous work “Walden” records his experiences living in solitude for two years near Walden Pond in Massachusetts.

His writings promote individualism, simplicity, and a close connection with nature, embodying the ideals of Transcendentalism.

Summary of Transcendentalism Literature

Transcendentalism significantly influenced American literature.

Prominent works such as Emerson’s “Nature” and Thoreau’s “Walden” are key texts in this philosophical movement.

These pieces illustrate the movement’s core beliefs in the inherent goodness of nature and individuals, the corruption of society, the importance of self-reliance, and the spiritual insights gained through personal intuition and nature contemplation.

In a broader sense, the literature of Transcendentalism represented a counter-culture to the prevailing societal norms of the time , emphasizing spiritual over material wealth.

American Transcendentalism

American transcendentalism was a philosophical and literary movement that emerged in the 19th century, primarily in New England, United States.

It was a response to the intellectual and spiritual climate of the time , which emphasized reason and scientific inquiry, often at the expense of individuality and spirituality.

Key figures associated with American transcendentalism include Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Margaret Fuller.

Transcendentalists believed in the inherent goodness of both humans and nature, and they emphasized the importance of intuition, self-reliance, and the connection between the individual and the divine.

They sought to transcend the limitations of the material world and traditional religious institutions through direct spiritual experiences and a deep appreciation of nature.

They believed that through self-exploration and self-expression, individuals could discover profound truths and achieve personal fulfillment.

The writings of American transcendentalists encompassed a wide range of subjects, including nature, social and political issues, individualism, and the potential for personal growth.

Some of the notable works associated with this movement include Emerson’s essay “Nature,” Thoreau’s book “Walden,” and Fuller’s book “Woman in the Nineteenth Century.”

American transcendentalism had a lasting impact on American literature, philosophy, and culture, and it played a significant role in shaping the development of individualism and intellectual thought in the United States.

Anti-Transcendentalism

Anti-transcendentalism, also known as dark romanticism or Gothic literature, was a literary movement that emerged as a reaction against the optimistic beliefs of transcendentalism.

It arose in the mid-19th century, overlapping with the transcendentalist movement but offering a contrasting perspective.

Anti-transcendentalists believed in the inherent darkness, sinfulness, and limitations of human nature.

They rejected the transcendentalist notion of inherent human goodness and the idea that individuals could achieve transcendence through personal growth and spiritual experiences.

Instead, anti-transcendentalists focused on the darker aspects of human existence, exploring themes such as the grotesque, the macabre, the supernatural, and the destructive forces of nature and society.

Prominent anti-transcendentalist authors include Nathaniel Hawthorne, Edgar Allan Poe, and Herman Melville.

Their works often delved into the complexities of the human psyche, explored the consequences of moral ambiguity and guilt, and highlighted the conflict between human desires and social expectations.

Examples of anti-transcendentalist literature include Hawthorne’s “The Scarlet Letter,” Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher,” and Melville’s “Moby-Dick.”

In contrast to the optimistic and idealistic worldview of the transcendentalists, anti-transcendentalism offered a more skeptical, pessimistic, and introspective perspective on the human condition, examining the inherent flaws and potential darkness within individuals and society.

Overall, while American transcendentalism focused on the potential for spiritual growth and the innate goodness of individuals, anti-transcendentalism explored the darker aspects of human nature and the limitations of human existence.

FAQs – Transcendentalism

1. what is transcendentalism.

Transcendentalism is a philosophical and literary movement that emerged in the United States in the mid-19th century, particularly in New England.

The movement centered on the belief in inherent goodness of both people and nature, emphasizing individualism, self-reliance, and the importance of personal connection with nature and the universe over organized institutions and religious doctrine.

2. Who were some of the key figures in the Transcendentalist movement?

Some of the key figures in the Transcendentalist movement were Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Margaret Fuller, and Amos Bronson Alcott.

These individuals were noted for their writings and lectures, which profoundly influenced American thought and literature during their time and continue to do so today.

3. What are the core beliefs of Transcendentalism?

The core beliefs of Transcendentalism include the inherent goodness of nature and humanity, the primacy of individual thought and emotion over societal norms or organized religious doctrine, and the belief that people are at their best when they are self-reliant and independent.

They also believed in the existence of an “Over-Soul,” a universal spirit to which all beings are connected.

4. How did Transcendentalists view nature?

Transcendentalists viewed nature as a direct connection to the divine or the universal spirit.

They believed that by immersing oneself in nature, an individual could gain profound insight and wisdom, and could escape from the corruption and materialism of society.

5. What impact did Transcendentalism have on American literature?

Transcendentalism had a profound impact on American literature, with works like Emerson’s “Nature” and Thoreau’s “Walden” being seminal texts in American literary history .

The movement influenced subsequent literary and philosophical movements, such as realism and romanticism, and shaped the themes of individualism and nature in much of American literature.

6. How does Transcendentalism relate to religion?

Transcendentalists often challenged the established religious institutions of their time, preferring personal spiritual experiences over organized doctrine.

They believed that individuals could directly experience the divine through nature and introspection, without the need for churches or religious intermediaries.

7. How is Transcendentalism relevant today?

Transcendentalism’s emphasis on individuality, self-reliance, and personal connection with nature continues to resonate in today’s society.

These ideas can be seen in movements that advocate for environmental protection, individual rights, and mindfulness practices, demonstrating that Transcendentalist philosophy still holds relevance in contemporary thought.

8. What was the relationship between Transcendentalism and the social reform movements of the 19th century?

Many Transcendentalists were deeply involved in social reform movements of their time.

For instance, they played active roles in the abolitionist movement, women’s suffrage, and educational reform.

They believed that their ideals of individual freedom and inherent goodness could extend to societal structures, prompting societal change.

9. How does Transcendentalism differ from Romanticism?

While both Transcendentalism and Romanticism value individualism and nature, they differ in their views of humanity and society.

Romanticism often portrays a more pessimistic view of humanity, emphasizing emotions, including fear and awe.

On the other hand, Transcendentalism typically holds an optimistic view of human nature and its potential, emphasizing self-reliance and individual agency.

10. How can I see Transcendentalist ideas in everyday life?

Transcendentalist ideas can be observed and applied in various aspects of everyday life.

Here are some ways you can see Transcendentalist principles reflected in your day-to-day experiences:

Connection with nature

Transcendentalists placed great importance on the relationship between humans and the natural world.

You can experience Transcendentalist ideas by spending time in nature, appreciating its beauty , and seeking solace and inspiration from it.

Take walks in parks or forests, go hiking, or simply spend time in your backyard or a nearby green space.

Individuality and self-reliance

Transcendentalists emphasized the importance of individuality and self-reliance.

You can embody these ideas by cultivating your unique qualities and expressing your individuality rather than conforming to societal norms.

Trust your own instincts, make independent decisions, and have the courage to follow your own path, even if it goes against the grain.

Simplifying your life

Transcendentalists believed in living a simple and deliberate life, free from unnecessary material possessions and distractions.

You can incorporate this idea into your daily routine by decluttering your living space, minimizing your consumption, and focusing on what truly matters to you.

Consider embracing minimalist principles and prioritizing experiences and relationships over material possessions.

Inner reflection and contemplation

Transcendentalists encouraged introspection and self-reflection as a means of attaining deeper understanding and connecting with the divine.

Take time each day to engage in practices like journaling, meditation, or mindfulness.

This can help you explore your thoughts, feelings, and beliefs, and gain clarity about your purpose and values.

Social and environmental activism

Transcendentalism also had a strong social justice component.

Many Transcendentalists advocated for causes such as abolitionism and women’s rights.

You can apply Transcendentalist principles by engaging in activism and working towards positive social change.

Stand up for justice, equality, and the rights of all individuals, and contribute to efforts that protect and preserve the environment.

Transcendentalism is a philosophy that encourages personal interpretation and individual experience.

Therefore, you may find other ways to see Transcendentalist ideas in your daily life that are meaningful and relevant to you.

Related Posts

Belief vs. Value

Belief vs. Faith

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Transcendentalism

I. definition.

Transcendentalism was a short-lived philosophical movement that emphasized transcendence , or “going beyond.” The Transcendentalists believed in going beyond the ordinary limits of thought and experience in several senses:

- transcending society by living a life of independence and contemplative self-reliance, often out in nature

- transcending the physical world to make contact with spiritual or metaphysical realities

- transcending traditional religion by blazing one’s own spiritual trail

- even transcending Transcendentalism itself by creating new philosophical ideas based on individual instinct and experience

II. Transcendentalism vs. Empiricism vs. Rationalism

When the Transcendentalists first came on the scene, philosophy was split between two major schools of thought: empiricism and rationalism . Transcendentalism rejected both schools, arguing that they were both too narrow-minded and failed to account for different kinds of transcendence.

| Main Arguments | Transcendentalist Critique | |

| We only (or at least mainly) understand the world through experience and the senses. Philosophy and science should proceed by carefully observing the world, building up a supply of concrete facts, and then analyzing those facts. The human mind is above all an organ of perception. The best form of reasoning is inductive. | The senses only tell us about the physical world, but the most important realities are those that lie beyond the physical world – things that we cannot see, feel, or hear, but must sense through our spirituality. If we place too much trust in the senses, we will end up forgetting that these other realities even exist, and this will cause both philosophical errors and spiritual pain. | |

| We only (or at least mainly) understand the world through logical deduction from a set of basic, immutable truths. Philosophy and science should proceed by working out what the fundamental truths of reality are, and then working downwards in logical, mathematical steps from there. The human mind is above all an organ of thought. The best form of reasoning is deductive | Rationality is always imperfect. What we think of as “logic” is really just a heavily formalized version of instinct or . While some logic is helpful in clearing up our thoughts, we shouldn’t be too dependent on it. After all, the real world is messy and constantly changing, and logic tries to make things appear clean and constant. This is a helpful illusion sometimes, but an illusion nonetheless. |

III. Quotes About Transcendentalism

“Go alone…refuse the good models, even those most sacred in the imagination of men, and dare to love God without mediator or veil.” ( Ralph Waldo Emerson )

Probably no one is more strongly associated with transcendentalism than the American essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emerson wrote fiery essays arguing for independence, self-reliance, and going beyond the boundaries of society. In this short quotation, Emerson expresses two of his central ideas: first, that you should follow your own path rather than imitating others, no matter how noble or admirable they may be; and second, traditional religious organizations are unnecessary in our spiritual path and we should seek an independent, one-to-one relationship with God.

“The reason I talk to myself is because I’m the only one whose answers I accept.” (George Carlin)

Stand-up legend George Carlin brought a strong Emersonian flavor to his comedy, a style that continues to be popular with modern stand-up comics. Like Emerson, Carlin hated social rules and was constantly pushing limits – using cursewords in his routines and talking about taboo subjects like race and sexuality at a time when standup comics almost never dared to broach these uncomfortable topics. Emerson would have liked the quote, which celebrates both social awkwardness (talking to yourself) and independent thinking.

IV. The History and Importance of Transcendentalism

Transcendentalism was America’s first major intellectual movement. It arose in the Eastern U.S. in the 1820s, when America had fully established its independence from Britain. At that time, the country was led by the first generation to have been born after the Revolutionary War – a generation that had never known anything other than independence. People in this generation couldn’t understand their parents’ reverence for European culture and philosophy, a reverence that was still strong in spite of the Americans’ desire for political independence. To them, America was its own nation, on its own continent, with its own laws and customs, and it needed to have its own art, culture, and philosophy as well – even its own religion! Transcendentalism was designed to fill all of these roles.

Although Transcendentalism didn’t grow into a flourishing philosophical school as its founders hoped (more on that in section 6), Transcendentalist ideas heavily influenced other movements and continue to have echoes today. The Transcendentalist movement was the main inspiration for William James and other founders of the Pragmatist school, which has been by far America’s most significant contribution to global philosophy.

The Transcendentalists even influenced European philosophy – Nietzsche, a revered if eccentric German philosopher, cited Transcendentalists as one of his main influences. Ironically, this means that the American thinkers were a strong philosophical inspiration to German nationalism and even Nazism, with their themes of strong individual leadership, rejecting traditional religion and morality, and breaking down limits so as to usher in a glorious future. Clearly, Emerson and Nietzsche would have strongly disapproved of Hitler and the Third Reich, but it goes to show how philosophers’ ideas can have unexpected consequences when they enter the realms of society, culture, and politics.

V. Transcendentalism in Popular Culture

There are many Transcendentalist themes in the sci-fi action movie Equilibrium starring Christian Bale. In the movie, John Preston is a Cleric, a law-enforcement officer required to take an emotion-suppressing pill every day so that he can carry out his duties without the interference of feelings. But when he misses his dose, Preston becomes increasingly aware of flaws in the system.

The film is Transcendentalist in a couple of ways: first, the emphasis on emotions rather than logic and duty. Preston’s moral awakening comes when he gets in touch with his emotions, which suggests that true morality is an emotional experience. Second, Preston ends up rejecting authority, social expectations, and the whole system that he’s been raised in. That makes him a very Emersonian sort of hero.

Many video games have “ranger” or “druid” characters (e.g. Dota 2, Warcraft, or Neverwinter Nights), and they often seem a little like transcendentalists. They live out in nature, or on the fringes of society, surviving by their own skills and living by their own rules – transcending the limits of civilization. In some cases, they also have spiritual or magical abilities that allow them to transcend the ordinary, physical world.

VI. Controversies

Is transcendentalism philosophy.

Transcendentalism never really caught on in professional philosophy, possibly because of the structure of its arguments. As we saw in section 2, transcendentalism rejected both rationalism and empiricism, pointing out the limitations in both logic and observation. But logic and observation are our main ways of attaining the truth, and if you push back against both of them, then what is the foundation of your own argument ?

In other words, Transcendentalism was based on an intuition, a feeling – several philosophers got together and had similar feelings about society, religion, and truth, but what they didn’t have was a set of arguments . As a result, they were not able to persuade new followers other than those who already shared their feelings. The Transcendentalists were brilliant writers, crafting expressive essays and compelling poetry, but they did not write philosophical arguments in the traditional sense.

As a result, some people have argued that Transcendentalism was more of a literary or artistic movement than a philosophical one. Whether or not that’s true really comes down to your definition – if you see philosophy as defined by a method of argument, then Transcendentalism isn’t philosophy. If you see philosophy as defined by an interest in musing about life, then Transcendentalism definitely belongs.

a. Logic and duty

b. Religion and community

c. Emotions and independence

d. All of the above

a. Ralph Waldo Emerson

b. Confucius

c. Socrates

a. Logic / Rationality

b. Empirical observation

Ralph Waldo Emerson and the Transcendentalism Movement

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803 – 1882)

On May 25 , 1803 , American essayist , lecturer , and poet Ralph Waldo Emerson was born, who led the Transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century . He was seen as a champion of individualism and a prescient critic of the countervailing pressures of society . He disseminated his philosophical thoughts through dozens of published essays and more than 1,500 public lectures.

“He who is in love is wise and is becoming wiser, sees newly every time he looks at the object beloved, drawing from it with his eyes and his mind those virtues which it possesses.” – Ralph Waldo Emerson, Address on The Method of Nature (1841)

Ralph Waldo Emerson – Early Years

Ralph Waldo Emerson was born in a vicarage as the son of William Emerson (1769-1811) and Ruth Haskins (1768-1853). He was the third of eight children. Emerson’s father was a Unitarian pastor and died at the age of 42 when Emerson was eight years old. After his father’s death, Emerson’s intellectual education lay with his aunt Mary Moody Emerson. Ralph Waldo Emerson enrolled at Harvard College at the age of 14 and throughout his time at the institute, he took jobs as teacher and was known for his activities as class poet reading various works to his classmates. Also from early age on, Emerson started to create a list of read books and poems with personal journal entries he named ‘Wide World’. Waldo Emerson moved to Floria, which critically influenced his future being. He met Prince Achille Murat with whom he had long discussions of philosophy, politics, religion and society, agreeing on many topics. Also, Emerson began writing his own poetry very intensively and made first contacts to slavery, which had a long lasting effect on the student Emerson. After the death of his wife he went on a trip to Europe, where he met Thomas Carlyle , William Wordsworth [ 8 ] and Samuel Taylor Coleridge [ 7 ] between 1832 and 1833. On this journey Emerson also became acquainted with German idealism and Indian philosophies, which would later leave traces in his work.

He began thinking of becoming a lecturer in the 1830’s and started his career in Boston. The content of this lecture later formed the fundamentals of his famous essay ‘ Nature ‘, published in 1836 at the age of 33. In this collection of essays he represented his belief that people should live in a simple way and in harmony with nature. In Nature he saw the true source of divine revelation. At the same time, he emphasized the importance of the creative activity of man as a driving force for a fundamental renewal and source of freedom and self-determination of the individual. So Nature ended with Emerson’s famous appeal: Build, therefore, your own world! Emerson no longer understood the divine as an external or higher power, but saw it as transferred into man himself. In Nature he developed one of the basic figures of his thinking, the transcendentalist triad, which includes self, nature and oversoul. According to Emerson, the Over-Soul is not an autonomous entity detached from the world of phenomena, but as effective in this as it is in the human mind. According to Emerson, man can therefore participate directly in the divine both through observation of nature and introspection. The essay is known to have had a great impact on Henry David Thoreau .[ 5 ] It essentially influenced his writing, especially his book Walden , published in 1854. Emerson became Thoreau’s mentor and together they became two of the most important transcendentalists of all times.

The American Scholar

“Every revolution was first a thought in one man’s mind and when the same thought occurs in another man, it is the key to that era.” – Ralph Waldo Emerson, Essays: First Series (1841)

After the success of ‘ Nature ‘, Emerson delivered his famous speech ‘ The American Scholar ‘, which depicted the foundation for both, his philosophical and literary career. Emerson and befriended intellectuals hosted several gatherings, which formed the Transcendental Club. In later years, the movement established a journal, of which Margaret Fuller was occupied as an editor. His works began to become more successful from 1850, including Conduct Of Life (1860) and Society And Solitude (1870). In 1864 he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Invitations to lectures, the award of honorary doctorates and the election to the Supervisory Board of Harvard University, which had suspended him at a young age, also showed the later academic recognition of Emerson.

Doubts on Christianity

“These roses under my window make no reference to former roses or to better ones; they are for what they are; they exist with God to-day. There is no time to them. There is simply the rose; it is perfect in every moment of its existence.” – Ralph Waldo Emerson, Essays: First Series (1841)

A setback to Emerson’s career as a lecturer depicted his speech at Harvard. In it he openly made his doubts on Christianity clear, for which he was proclaimed an atheist. Indeed, Waldo Emerson used to be a great Christian believer as well, but after his first wife passed away he began questioning the Church’s methods and began to turn away from his original religion. However, he recovered from this provocative lecture and gave many more until a fire at his home occurred in later years. Emerson’s health began to decline and from then on he only lectured in front of small, familiar groups. Still, he kept publishing poetry and anthologies like ‘ Parnassus ‘.

Against Slavery

Later years.

Starting in 1867, Emerson’s health began declining; he wrote much less in his journals. Beginning as early as the summer of 1871 or in the spring of 1872, he started experiencing memory problems and suffered from aphasia. By the end of the decade, he forgot his own name at times and, when anyone asked how he felt, he responded, “ Quite well; I have lost my mental faculties, but am perfectly well “. After the fire in his house in 1872, Ralph Waldo Emerson began to withdraw more and more from public life. I n late 1874, Emerson published an anthology of poetry called Parnassus . He died in Concord, Massachusetts on April 27, 1882 at age 78.

References and Further Reading:

- [1] American Transcendentalism Website

- [2] Emerson & Thoreau

- [3] Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy : “ Ralph Waldo Emerson

- [4] Reading Ralph Waldo Emerson, a blog featuring excerpts from Emerson’s journals

- [5] Never Stop Looking into Nature – Henry David Thoreau , SciHi Blog

- [6] The Assassination of a President , SciHi Blog

- [7] Samuel Taylor Coleridge and English Literary Romanticism , SciHi Blog

- [8] William Wordsworth and the Romantic Age of English Literature , SciHi Blog

- [9] Ralph Waldo Emerson at Wikidata

- [10] Emerson and Concord: America Discovers Idealism, AN evening with Robert Richardson , Concord Museum @ youtube

- [11] Porte, Joel; Morris, Saundra, eds. (1999). The Cambridge Companion to Ralph Waldo Emerson . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- [12] McAleer, John (1984). Ralph Waldo Emerson: Days of Encounter . Boston: Little, Brown.

- [13] Gura, Philip F. (2007). American Transcendentalism: A History . New York: Hill and Wang.

- [14] Timeline for Ralph Waldo Emerson, via Wikidata

Harald Sack

Related posts, sidney fox and his research for the origins of life, frederick william twort and the bacteriophages, egon friedell’s fascinating cutural histories, h.p. lovecraft and the inconceivable terror, one comment.

brilliant!!!!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Further Projects

- February (28)

- January (30)

- December (30)

- November (29)

- October (31)

- September (30)

- August (30)

- January (31)

- December (31)

- November (30)

- August (31)

- February (29)

- February (19)

- January (18)

- October (29)

- September (29)

- February (5)

- January (5)

- December (14)

- November (9)

- October (13)

- September (6)

- August (13)

- December (3)

- November (5)

- October (1)

- September (3)

- November (2)

- September (2)

Legal Notice

- Privacy Statement

- Biographies

- Special Features

- Denominational Administration & Governance

Religious Education

- Related Organizations

- General Assembly Minutes

Transcendentalism and Ralph Waldo Emerson

The Living Legacy of Ralph Waldo Emerson

“Mind is the only reality. The real person is what he thinks. The material world is a shadow of the idea. I am only a reflection of what I think.” —Ralph Waldo Emerson

On September 8, 1836, while attending Harvard’s bicentennial celebration, Emerson met at Willard’s Hotel in Cambridge with his friends Henry Hedge, George Putnam (a Unitarian minister), and George Ripley to plan a symposium for people who, like themselves, found the present state of thought in America unsatisfactory. They were also moved by the stale intellectual climate of Harvard and Cambridge. President Quincy had his eye on the past; theirs was on the present and future. Almost two weeks later, on September 19, the first meeting of what came to be known as the Transcendental Club was born out of protest.

The movement took its name from the German philosopher Kant. It held that there are moral laws which transcend man—that there are absolute truths. Beauty, goodness, wisdom are to the philosopher precisely what heat, motion, and chemical actions are to the physicist. Transcendentalists believed that religion is a primary sentiment in human nature, not merely dependent on certain facts of history. It is poetic, generous, devout, open to all the humanities and sciences, literature, and sympathies of philosophy.

Basically, they held that there are three primary ideas we know intuitively: the ideas of God, duty, and immortality. These need no confirmation from any book or miracles, but are affirmed by humankind’s own divine nature. God is not a being apart from the universe, but everywhere, especially in humans, insofar as our thoughts are infinite. As we reason, God is absolute Reason. “Stand aside,” said Emerson, “and let God think—that is, let the divine within you show through. Duty is taught by the voice within. We know, when we use our highest Reason, what we ought to do. We need no Ten Commandments for that. Men may shirk duty in perilous times, but they still know what their duty is.”

The Transcendental Club’s magazine, The Dial , first appeared in 1840 with Margaret Fuller as editor and George Ripley her assistant. Emerson contributed and edited essays, and became its editor in 1842. Through this vehicle, he encouraged many promising thinkers and writers. His influence on the movement was central.

“Such is the saturation of things with the moral law, that you cannot escape from it. You may kill the preachers of it, but innumerable preaches survive: the violets and roses and grass preach it, rain and snow and wind and frost, moon and tides, every change and every cause in nature is nothing but a disguised missionary.” —Ralph Waldo Emerson

Collections

Denominational Administration

Search by Category

Search by tag.

- Book Reviews

- Cambridge & Harvard

- Congregational Polity

- Liturgy & Holidays

- Lectures & Sermons

- Poetry, Prayers & Visual Arts

- Religion & Culture

- Social Reform

- Theology & Philosophy

- Women & Religion

- About Harvard Square Library

Transcendentalism

Transcendentalism is an American literary, political, and philosophical movement of the early nineteenth century, centered around Ralph Waldo Emerson. Other important transcendentalists were Henry David Thoreau, Margaret Fuller, Amos Bronson Alcott, Frederic Henry Hedge, and Theodore Parker. Stimulated by English and German Romanticism, the Biblical criticism of Herder and Schleiermacher, and the skepticism of Hume, the transcendentalists operated with the sense that a new era was at hand. They were critics of their contemporary society for its unthinking conformity, and urged that each individual find, in Emerson's words, “an original relation to the universe” (O, 3). Emerson and Thoreau sought this relation in solitude amidst nature, and in their writing. By the 1840s they, along with other transcendentalists, were engaged in the social experiments of Brook Farm, Fruitlands, and Walden; and, by the 1850's in an increasingly urgent critique of American slavery.

1. Origins and Character

2. high tide: the dial , fuller, thoreau, 3. social and political critiques, bibliography, other internet resources, related entries.

What we now know as transcendentalism first arose among the liberal New England Congregationalists, who departed from orthodox Calvinism in two respects: they believed in the importance and efficacy of human striving, as opposed to the bleaker Puritan picture of complete and inescapable human depravity; and they emphasized the unity rather than the “Trinity” of God (hence the term “Unitarian,” originally a term of abuse that they came to adopt.) Most of the Unitarians held that Jesus was in some way inferior to God the Father but still greater than human beings; a few followed the English Unitarian Joseph Priestley (1733–1804) in holding that Jesus was thoroughly human, although endowed with special authority. The Unitarians' leading preacher, William Ellery Channing (1780–1842), portrayed orthodox Congregationalism as a religion of fear, and maintained that Jesus saved human beings from sin, not just from punishment. His sermon “Unitarian Christianity” (1819) denounced “the conspiracy of ages against the liberty of Christians” (P, 336) and helped give the Unitarian movement its name. In “Likeness to God” (1828) he proposed that human beings “partake” of Divinity and that they may achieve “a growing likeness to the Supreme Being” (T, 4).

The Unitarians were “modern.” They attempted to reconcile Locke's empiricism with Christianity by maintaining that the accounts of miracles in the Bible provide overwhelming evidence for the truth of religion. It was precisely on this ground, however, that the transcendentalists found fault with Unitarianism. For although they admired Channing's idea that human beings can become more like God, they were persuaded by Hume that no empirical proof of religion could be satisfactory. In letters written in his freshman year at Harvard (1817), Emerson tried out Hume's skeptical arguments on his devout and respected Aunt Mary Moody Emerson, and in his journals of the early 1820's he discusses with approval Hume's Dialogues on Natural Religion and his underlying critique of necessary connection. “We have no experience of a Creator,” Emerson writes, and therefore we “know of none” (JMN 2, 161).

Skepticism about religion was also engendered by the publication of an English translation of F. D. E. Schleiermacher's Critical Essay Upon the Gospel of St. Luke (1825), which introduced the idea that the Bible was a product of human history and culture. Equally important was the publication in 1833 — some fifty years after its initial appearance in Germany — of James Marsh's translation of Johann Gottfried van Herder's Spirit of Hebrew Poetry (1782). Herder blurred the lines between religious texts and humanly-produced poetry, casting doubt on the authority of the Bible, but also suggesting that texts with equal authority could still be written. It was against this background that Emerson asked in 1836, in the first paragraph of Nature : “Why should we not have a poetry and philosophy of insight and not of tradition, and a religion by revelation to us, and not the history of theirs” (O, 5). The individual's “revelation” — or “intuition,” as Emerson was later to speak of it — was to be the counter both to Unitarian empiricism and Humean skepticism.

An important source for the transcendentalists' knowledge of German philosophy was Frederic Henry Hedge (1805–90). Hedge's father Levi Hedge, a Harvard professor of logic, sent him to preparatory school in Germany at the age of thirteen, after which he attended the Harvard Divinity School. Ordained as a Unitarian minister, Hedge wrote a long review of the work of Samuel Taylor Coleridge for the Christian Examiner in 1833. Noting Coleridge's fondness for “German metaphysics” and his immense gifts of erudition and expression, he laments that Coleridge had not made Kant and the post-Kantians more accessible to an English-speaking audience. This is the task — to introduce the “transcendental philosophy” of Kant, (T, 87) — that Hedge takes up. In particular, he explains Kant's idea of a Copernican Revolution in philosophy: “[S]ince the supposition that our intuitions depend on the nature of the world without, will not answer, assume that the world without depends on the nature of our intuitions.” This “key to the whole critical philosophy,” Hedge continues, explains the possibility of “a priori knowledge” (T, 92). Hedge organized what eventually became known as the Transcendental Club, by suggesting to Emerson in 1836 that they form a discussion group for disaffected young Unitarian clergy. The group included George Ripley and Bronson Alcott, had some 30 meetings in four years, and was a sponsor of The Dial and Brook Farm. Hedge was a vocal opponent of slavery in the 1830's and a champion of women's rights in the 1850's, but he remained a Unitarian minister, and became a professor at the Harvard Divinity School.

Another source for the transcendentalists' knowledge of German philosophy was Madame de Staël (Anne-Louise-Germaine Necker) (1766–1817), whose De l'Allemagne ( On Germany ) was a favorite of the young Emerson. In a sweeping survey of European metaphysics and political philosophy, de Staël praises Locke's devotion to liberty, but sees him as the originator of a sensationalist school of epistemology that leads to the skepticism of Hume. She finds an attractive contrast in the German tradition that begins with Leibniz and culminates in Kant, which asserts the power and authority of the mind.

Equally important for the emerging philosophy of transcendentalism was the work of James Marsh (1794–1842), a graduate of Andover and the president of the University of Vermont. Marsh was convinced that German philosophy held the key to a reformed theology. His American edition of Coleridge's Aids to Reflection (1829) introduced Coleridge's version — much indebted to Schelling — of Kantian terminology, terminology that runs throughout Emerson's early work. In Nature , for example, Emerson writes: “The Imagination may be defined to be, the use which the Reason makes of the material world” (O, 25).

German philosophy and literature was also championed by Thomas Carlyle, whom Emerson met on his first visit to Europe in 1831. Carlyle's philosophy of action in such works as Sartor Resartus resonates with Emerson's idea in “The American Scholar” that action — along with nature and “the mind of the Past” (O, 39) is essential to human education. Along with his countrymen Coleridge and Wordsworth, Carlyle embraced a “natural supernaturalism,” the view that nature, including human beings, has the powers, status, and authority traditionally attributed to an independent deity.

Piety towards nature was also a main theme of William Wordsworth, whose poetry was in vogue in America in the 1820's. Wordsworth's depiction of an active and powerful mind cohered with the shaping power of the mind that his collaborator in the Lyrical Ballads , Samuel Taylor Coleridge, traced to Kant. The idea of such power pervades Emerson's Nature , where he writes of nature as “obedient” to spirit and counsels each of us to “Build … your own world.”

Emerson's sense that men and women were, as he put it in Nature , gods “in ruins,” led to one of transcendentalism's defining events, his delivery of an “Address” at the Harvard Divinity School graduation in 1838. Emerson portrayed the contemporary church that the graduates were about to lead as an “eastern monarchy of a Christianity” that had become an “injuror of man” (O, 58). Jesus, in contrast, was a “friend of man.” Yet he was just one of the “true race of prophets,” whose message is not so their own greatness, as the “greatness of man” (O, 57). Emerson rejects the Unitarian argument that miracles prove the truth of Christianity, not simply because the evidence is weak, but because proof of the sort they envision embodies a mistaken view of the nature of religion: “conversion by miracles is a profanation of the soul.” Emerson finds evidence for religion more direct than testimony in a “perception” that produces a “religious sentiment” (O, 55).

The “Address” drew a quick and angry response from Andrews Norton (1786–1853) of the Harvard Divinity School, often known as the “Unitarian Pope.” In “The New School in Literature and Religion” (1838), Norton complains of “a restless craving for notoriety and excitement,” which he traces to German “speculatists” and “barbarians” and “that hyper-Germanized Englishman, Carlyle.” Emerson's “Address,” he concludes, is at once “an insult to religion” (T, 248) and “an incoherent rhapsody” (T, 249).

An earlier transcendentalist scandal surrounded the publication of Amos Bronson Alcott's Conversations with Children Upon the Gospels (1836). Alcott (1799–1888) was a self-taught educator from Connecticut who established a series of schools that aimed to “draw out” the intuitive knowledge of children. He found anticipations of his views about a priori knowledge in the writings of Plato and Kant, and support in Coleridge's Aids to Reflection for the idea that idealism and materiality could be reconciled. Alcott replaced the hard benches of the common schools with more comfortable furniture that he built himself, and left a central space in his classrooms for dancing. The Conversations with Children Upon the Gospels , based on a school Alcott (and his assistant Elizabeth Peabody) ran in Boston, argued that evidence for the truth of Christianity could be found in the unimpeded flow of children's thought. What people particularly noticed about Alcott's book, however, were its frank discussions of conception, circumcision, and childbirth. Rather than gaining support for his school, the publication of the book caused many parents to withdraw their children from it, and the school — like many of Alcott's projects, failed.

Surveying the scene in his 1842 lecture, “The Transcendentalist,” Emerson begins with a philosophical account, according to which what are generally called “new views” are not really new, but rather part of a broad tradition of idealism. It is not a skeptical idealism, however, but an anti-skeptical idealism deriving from Kant:

It is well known to most of my audience, that the Idealism of the present day acquired the name of Transcendental, from the use of that term by Immanuel Kant, of Konigsberg [sic], who replied to the skeptical philosophy of Locke, which insisted that there was nothing in the intellect which was not previously in the experience of the senses, by showing that there was a very important class of ideas, or imperative forms, which did not come by experience, but through which experience was acquired; that these were intuitions of the mind itself; and he denominated them Transcendental forms (O, 101–2).

Emerson shows here a basic understanding of three Kantian claims, which can be traced throughout his philosophy: that the human mind “forms” experience; that the existence of such mental operations is a counter to skepticism; and that “transcendental” does not mean “transcendent” or beyond human experience altogether, but something through which experience is made possible. Emerson's idealism is not purely Kantian, however, for (like Coleridge's) it contains a strong admixture of Neoplatonism and post-Kantian idealism. Emerson thinks of Reason, for example, as a faculty of “vision,” as opposed to the mundane understanding, which “toils all the time, compares, contrives, adds, argues….” ( Letters , vol. 1, 413). For many of the transcendentalists the term “transcendentalism” represented nothing so technical as an inquiry into the presuppositions of human experience, but a new confidence in and appreciation of the mind's powers, and a modern, non-doctrinal spirituality. The transcendentalist, Emerson states, believes in miracles, conceived as “the perpetual openness of the human mind to new influx of light and power…” (O, 100).

Emerson keeps his distance from the transcendentalists in his essay by speaking always of what “they” say or do, despite the fact that he was regarded then and is regarded now as the leading transcendentalist. He notes with some disdain that the transcendentalists are “'not good members of society,” that they do not work for “the abolition of the slave-trade” (though both these charges have been leveled at him). He closes the essay nevertheless with a defense of the transcendentalist critique of a society pervaded by “a spirit of cowardly compromise and seeming, which intimates a frightful skepticism, a life without love, and an activity without an aim” (O, 106). This critique is Emerson's own in such writings as “Self-Reliance,” and “The American Scholar”; and it finds a powerful and original restatement in the “Economy” chapter of Thoreau's Walden .

The transcendentalists had several publishing outlets: at first The Christian Examiner , then, after the furor over the “Divinity School Address,” The Western Messenger (1835–41) in St Louis, then the Boston Quarterly Review (1838–44). The Dial (1840–4) was a special case, for it was planned and instituted by the members of the Transcendental Club, with Margaret Fuller (1810–50) as the first editor. Emerson succeeded her for the magazine's last two years. The writing in The Dial was uneven, but in its four years of existence it published Fuller's “The Great Lawsuit” (the core of her Woman in the Nineteenth Century ) and her long review of Goethe's work; prose and poetry by Emerson; Alcott's “Orphic Sayings” (which gave the magazine a reputation for silliness); and the first publications of a young friend of Emerson's, Henry David Thoreau (1817–62). After Emerson became editor in 1842 TheDial published a series of “Ethnical Scriptures,” translations from Chinese and Indian philosophical works.

Margaret Fuller was the daughter of a Massachusetts congressman who provided tutors for her in Latin, Greek, chemistry, philosophy and, later, German. Exercising what Barbara Packer calls “her peculiar powers of intrusion and caress” (P, 443), Fuller became friends with many of the transcendentalists, including Emerson. She organized a series of popular “conversations” for women in Boston in the winters of 1839–44, journeyed to the Midwest in the summer of 1843, and published her observations as Summer on the Lakes . After this publishing success, Horace Greeley, a friend of Emerson's and the editor of the New York Tribune , invited her to New York to write for the Tribune . Fuller abandoned her previously ornate and pretentious style, issuing pithy reviews and forthright criticisms: for example, of Longfellow's poetry and Carlyle's attraction to brutality. Fuller was in Europe from 1846–9, sending back hundreds of pages for the Tribune . On her return to America with her husband and son, she drowned in a hurricane off the coast of Fire Island, New York.

Woman in the Nineteenth Century (1845 ), a revision of her “Great Lawsuit” manifesto in The Dial , is Fuller's major philosophical work. She holds that masculinity and femininity pass into one another, that there is “no wholly masculine man, no purely feminine woman” (T, 418). Women are treated as dependents, however, and their self-reliant impulses are often held against them. What they most want is the freedom to unfold their powers, a freedom Fuller holds to be necessary not only for their self-development, but for the renovation of society. Like Thoreau and Emerson, she calls for periods of withdrawal from a society whose members are in various states of “distraction” and “imbecility,” and a return only after “the renovating fountains” of individuality have risen up. Such individuality is necessary in particular for the proper constitution of that form of society known as marriage. “Union,” she holds, “is only possible to those who are units” (T, 419).

Henry Thoreau studied Latin, Greek, Italian, French, German, and Spanish at Harvard, where he heard Emerson's “The American Scholar” as the commencement address in 1837. He first published in The Dial when Emerson commissioned him to review a series of reports on wildlife by the state of Massachusetts, but he cast about for a literary outlet after The Dial’ s failure in 1844. In 1845, his move to Walden Pond allowed him to complete his first book, A Week on the Concord and the Merrimac Rivers . He also wrote a first draft of Walden , which eventually appeared in 1854.

Nature comes to even more prominence in Walden than in Emerson's Nature , which it followed by eighteen years. Nature becomes particular: this tree, this bird, this state of the pond on a summer evening or winter morning become Thoreau's subjects. Thoreau takes a receptive stance. He finds himself “neighbor to” rather than a hunter of birds; and a dweller in a house that is no more and no less than a place where he properly sits. From the right perspective, Thoreau finds, he can possess and use a farm with more satisfaction than the farmer, who is preoccupied with feeding his family and expanding his operations. In Walden 's opening chapter, “Economy,” Thoreau considers the trade-offs we make in life, and he asks, as Plato did in The Republic , what are life's real necessities. Like the Roman philosophers Marcus Porcius Cato and Marcus Varro he seeks a “life of simplicity, independence, magnanimity, and trust” (W, 15). Instead, he finds that “the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation” (W, 8). Thoreau's “experiment” at Walden shows that a life of simplicity and independence can be achieved today (W, 17). If Thoreau counsels simple frugality — a vegetarian diet for example, and a dirt floor — he also counsels a kind of extravagance, a spending of what you have in the day that shall never come again. True economy, he writes, is a matter of “improving the nick of time” (W, 17).

Thoreau went to Walden Pond on the anniversary of America's declared independence from Britain — July 4, 1845, declaring his own independence from a society that is “commonly too cheap.” It is not that he is against all society, but that he finds we meet too often, before we have had the chance to acquire any “new value for each other” (W, 136). Thoreau welcomes those visitors who “speak reservedly and thoughtfully” (W, 141), and who preserve an appropriate sense of distance; he values the little leaves or acorns left by visitors he never meets. Thoreau lived at Walden for just under three years, a time during which he sometimes visited friends and conducted business in town (it was on one such visit, to pick up a mended shoe, that he was arrested for tax avoidance).

At the opening of Walden's chapter on “Higher Laws” Thoreau confesses to once having desired to slaughter a woodchuck and eat it raw, just to get at its wild essence. He values fishing and hunting for their taste of wildness, though he finds that in middle age he has given up eating meat. He finds wildness not only in the woods, but in such literary works as Hamlet and the Iliad; and even in certain forms of society: “The wildness of the savage is but a faint symbol of the awful ferity with which good men and lovers meet” (“Walking” (1862), p. 621). The wild is not always consoling or uplifting, however. In The Maine Woods , Thoreau records a climb on Mount Ktaadn in Maine when he confronted the alien materiality of the world; and in Cape Cod (1865), he records the foreignness, not the friendliness, of nature: the shore is “a wild, rank place, and there is no flattery in it” (Packer, “The Transcendentalists,” 577).

Although Walden initiates the American tradition of environmental philosophy, it is equally concerned with reading and writing. In the chapter on “Reading,” Thoreau speaks of books that demand and inspire “reading, in a high sense” (W, 104). He calls such books “heroic,” and finds them equally in literature and philosophy, in Europe and Asia: “Vedas and Zendavestas and Bibles, with Homers and Dantes and Shakespeares…” (W, 104). Thoreau suggests that Walden is or aspires to be such a book; and indeed the enduring construction from his time at Walden is not the cabin he built but the book he wrote.

Thoreau maintains in Walden that writing is “the work of art closest to life itself” (W, 102). In his search for such closeness, he began to reconceive the nature of his journal. Both he and Emerson kept journals from which their published works were derived. But in the early 1850s, Thoreau began to conceive of the journal as a work in itself, “each page of which should be written in its own season & out of doors or in its own locality wherever it may be” (J, 67). A journal has a sequence set by the days, but it may have no order; or what order it has emerges in the writer's life as he meets the life of nature. With its chapters on “Reading,” “Solitude,” “Economy,” “Winter,” and “Spring,” Walden is more “worked up” than the journal; in this sense, Thoreau came to feel, it is less close than the journal to the nature it records.

The transcendentalists operated from the start with the sense that the society around them was seriously deficient: a “mass” of “bugs or spawn” as Emerson put it in “The American Scholar”; slavedrivers of themselves, as Thoreau says in Walden . Thus the attraction of alternative life-styles: Alcott's ill-fated Fruitlands; Brook Farm, planned and organized by the Transcendental Club; and Thoreau's cabin at Walden. As the nineteenth century came to its mid-point, the transcendentalists' dissatisfaction with their society became focused on policies and actions of the United States government: the treatment of the Native Americans, the war with Mexico, and, above all, the continuing and expanding practice of slavery.

Emerson's 1838 letter to President Martin Van Buren is an early expression of the depth of his despair at actions of his country, in this case the ethnic cleansing of American land east of the Mississippi. The 16,000 Cherokees lived in what is now Kentucky and Tennessee, and in parts of the Carolinas, Georgia, and Virginia. They were one of the more assimilated tribes, who owned property, drove carriages, used plows and spinning wheels, and even owned slaves. Wealthy Cherokees sent their children to elite academies or seminaries. The Cherokee chief refused to sign a removal agreement with the government of Andrew Jackson, but the government found a minority faction to agree to removal of the tribe to territories west of the Mississippi. Despite the opposition of the Supreme Court under Chief Justice John Marshall, the Cherokees — many of whom died along the way — were removed under President Van Buren in 1835. In his letter, Emerson called this “a crime that really deprives us as well as the Cherokees of a country; for how could we call the conspiracy that should crush these poor Indians our Government, or the land that was cursed by their parting and dying imprecations our country, any more?” (A, 3).