- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

Chinese calligraphy

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Asia Society - Center for Global Education - Chinese Calligraphy

- China Online Museum - Chinese Calligraphy

Chinese calligraphy , the stylized artistic writing of Chinese characters, the written form of Chinese that unites the languages (many mutually unintelligible) spoken in China . Because calligraphy is considered supreme among the visual arts in China, it sets the standard by which Chinese painting is judged. Indeed, the two arts are closely related.

The early Chinese written words were simplified pictorial images, indicating meaning through suggestion or imagination. These simple images were flexible in composition , capable of developing with changing conditions by means of slight variations.

The earliest known Chinese logographs are engraved on the shoulder bones of large animals and on tortoise shells. For this reason the script found on these objects is commonly called jiaguwen , or shell-and-bone script. It seems likely that each of the ideographs was carefully composed before it was engraved. Although the figures are not entirely uniform in size, they do not vary greatly in size. They must have evolved from rough and careless scratches in the still more distant past. Since the literal content of most jiaguwen is related to ancient religious, mythical prognostication or to rituals, jiaguwen is also known as oracle bone script. Archaeologists and paleographers have demonstrated that this early script was widely used in the Shang dynasty ( c. 1600–1046 bce ). Nevertheless, the 1992 discovery of a similar inscription on a potsherd at Dinggongcun in Shandong province demonstrates that the use of a mature script can be dated to the late Neolithic Longshan culture ( c. 2600–2000 bce ).

It was said that Cangjie, the legendary inventor of Chinese writing , got his ideas from observing animals’ footprints and birds’ claw marks on the sand as well as other natural phenomena. He then started to work out simple images from what he conceived as representing different objects such as those that are given below:

Jiaguwen was followed by a form of writing found on bronze vessels associated with ancestor worship and thus known as jinwen (“metal script”). Wine and raw or cooked food were placed in specially designed cast bronze vessels and offered to the ancestors in special ceremonies. The inscriptions, which might range from a few words to several hundred, were incised on the insides of the vessels. The words could not be roughly formed or even just simple images; they had to be well worked out to go with the decorative ornaments outside the bronzes, and in some instances they almost became the chief decorative design themselves. Although they preserved the general structure of the bone-and-shell script, they were considerably elaborated and beautified. Each bronze or set of them may bear a different type of inscription, not only in the wording but also in the manner of writing. Hundreds were created by different artists. The bronze script—which is also called guwen (“ancient script”), or dazhuan (“large seal”) script—represents the second stage of development in Chinese calligraphy.

When China was united for the first time, in the 3rd century bce , the bronze script was unified and regularity enforced. Shihuangdi , the first emperor of Qin , gave the task of working out the new script to his prime minister , Li Si , and permitted only the new style to be used. The following words can be compared with similar words in bone-and-shell script:

This third stage in the development of Chinese calligraphy was known as xiaozhuan (“small seal”) style. Small-seal script is characterized by lines of even thickness and many curves and circles. Each word tends to fill up an imaginary square, and a passage written in small-seal style has the appearance of a series of equal squares neatly arranged in columns and rows, each of them balanced and well-spaced.

This uniform script had been established chiefly to meet the growing demands for record keeping. Unfortunately, the small-seal style could not be written speedily and therefore was not entirely suitable, giving rise to the fourth stage, lishu , or official style. (The Chinese word li here means “a petty official” or “a clerk”; lishu is a style specially devised for the use of clerks.) Careful examination of lishu reveals no circles and very few curved lines. Squares and short straight lines, vertical and horizontal, predominate. Because of the speed needed for writing, the brush in the hand tends to move up and down, and an even thickness of line cannot be easily achieved.

Lishu is thought to have been invented by Cheng Miao (240–207 bce ), who had offended Shihuangdi and was serving a 10-year sentence in prison. He spent his time in prison working out this new development, which opened up seemingly endless possibilities for later calligraphers. Freed by lishu from earlier constraints, they evolved new variations in the shape of strokes and in character structure. The words in lishu style tend to be square or rectangular with a greater width than height. While stroke thickness may vary, the shapes remain rigid; for instance, the vertical lines had to be shorter and the horizontal ones longer. As this curtailed the freedom of hand to express individual artistic taste, a fifth stage developed— zhenshu ( kaishu ), or regular script. No individual is credited with inventing this style, which was probably created during the period of the Three Kingdoms and Xi Jin (220–317). The Chinese write in regular script today; in fact, what is known as modern Chinese writing is almost 2,000 years old, and the written words of China have not changed since the first century of the Common Era.

“Regular script” means “the proper script type of Chinese writing” used by all Chinese for government documents, printed books, and public and private dealings in important matters ever since its establishment. Since the Tang period (618–907 ce ), each candidate taking the civil service examination was required to be able to write a good hand in regular style. This imperial decree deeply influenced all Chinese who wanted to become scholars and enter the civil service. Although the examination was abolished in 1905, most Chinese up to the present day try to acquire a hand in regular style.

In zhenshu each stroke, each square or angle, and even each dot can be shaped according to the will and taste of the calligrapher. Indeed, a word written in regular style presents an almost infinite variety of problems of structure and composition, and, when executed, the beauty of its abstract design can draw the mind away from the literal meaning of the word itself.

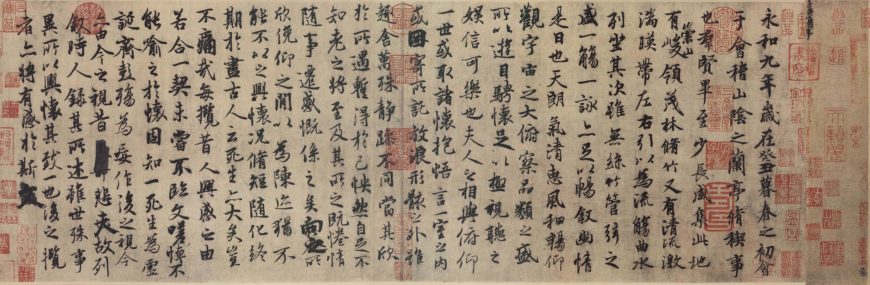

The greatest exponents of Chinese calligraphy were Wang Xizhi and his son Wang Xianzhi in the 4th century. Few of their original works have survived, but a number of their writings were engraved on stone tablets and woodblocks, and rubbings were made from them. Many great calligraphers imitated their styles, but none ever surpassed them for artistic transformation.

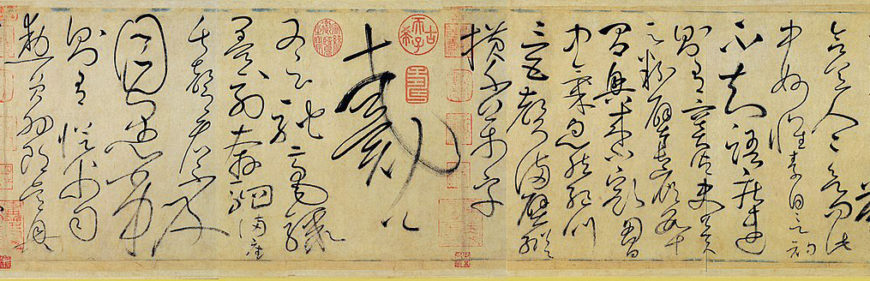

Wang Xizhi not only provided the greatest example in the regular script, but he also relaxed the tension somewhat in the arrangement of the strokes in the regular style by giving easy movement to the brush to trail from one word to another. This is called xingshu , or running script. This, in turn, led to the creation of caoshu , or grass script, which takes its name from its resemblance to windblown grass—disorderly yet orderly. The English term cursive writing does not describe grass script, for a standard cursive hand can be deciphered without much difficulty, but grass style greatly simplifies the regular style and can be deciphered only by seasoned calligraphers. It is less a style for general use than for that of the calligrapher who wishes to produce a work of abstract art .

Technically speaking, there is no mystery in Chinese calligraphy. The tools for Chinese calligraphy are few—an ink stick, an ink stone, a brush, and paper (some prefer silk). The calligrapher, using a combination of technical skill and imagination, must provide interesting shapes to the strokes and must compose beautiful structures from them without any retouching or shading and, most important of all, with well-balanced spaces between the strokes. This balance needs years of practice and training.

The fundamental inspiration of Chinese calligraphy, as of all arts in China, is nature. In regular script each stroke, even each dot, suggests the form of a natural object. As every twig of a living tree is alive, so every tiny stroke of a piece of fine calligraphy has the energy of a living thing. Printing does not admit the slightest variation in the shapes and structures, but strict regularity is not tolerated by Chinese calligraphers, especially those who are masters of the caoshu . A finished piece of fine calligraphy is not a symmetrical arrangement of conventional shapes but, rather, something like the coordinated movements of a skillfully composed dance—impulse, momentum, momentary poise, and the interplay of active forces combining to form a balanced whole.

Chinese calligraphy, an introduction

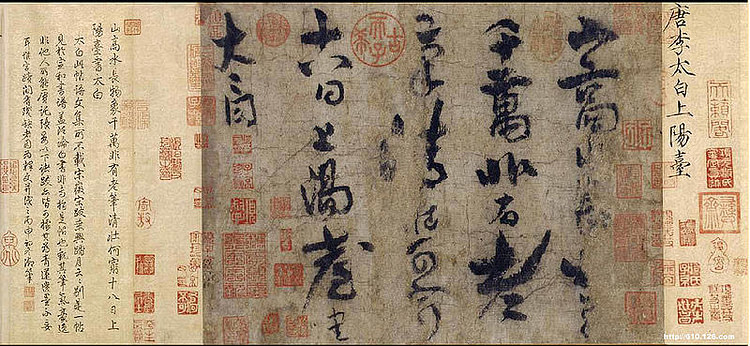

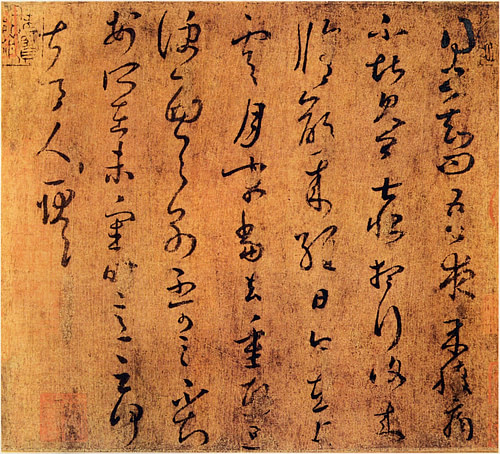

Main text of a Tang Dynasty copy of Wang Xizhi’s Lantingji Xu (Orchid Pavilion Preface) by Feng Chengsu (馮承素). Throughout Chinese history, many copies were made of the Lantingji Xu , which described the beauty of the landscape around the Orchid Pavilion and the get-together of Wang Xizhi and his friends. The original is lost. This Tang copy made between 627–650 is considered the best of the copies that has survived (Palace Museum in Beijing)

Art of the line

Calligraphy is the world’s oldest abstract art—the art of the line. This basic visual element can also hold a symbolic charge. Nowhere has the symbolic power of the line manifested itself more fully than in Chinese calligraphy, a tradition that spans over 3,000 years. The aesthetics of calligraphy are important to the history of art in East Asia, where during much of its premodern era classical Chinese was the lingua franca (or common language).

Chinese calligrapher at Lunar New Year event, Trammell & Margaret Crow Collection of Asian Art, Dallas, Texas, 2 February 2013 (photo: Joe Mabel , CC BY-SA 3.0)

Knowing how to read and write Chinese characters is not a prerequisite for appreciating the unique charm of calligraphy. The characters are fundamentally ideographic in nature, meaning they can symbolize the idea of a thing rather than transcribe its pronunciation. A calligrapher wields a pliant brush, dips its tip fashioned with animal hair into ink made from grinding on an ink stone with water, and writes on paper or silk that could have different absorbency rates depending on how it has been treated. Brush, ink, ink stone, and paper are collectively referred to as the “Four Treasures of the Study” 文房四寶 .

A capable calligrapher can achieve a surprisingly wide and rich array of artistic effects that eloquently convey the personality of the artist and the ambience of the moment of inspiration. The responsiveness of the pliant brush lends itself to registering the subtle changes in pressure, direction, and speed in the force transmitted from the shoulder of the calligrapher, to his arm, wrist, and finally fingertips. This accounts for calligraphic brushstrokes’ unique facility in capturing with great vividness and immediacy the kinetic energy that coursed through the calligrapher’s body during the creation process.

The 5 major calligraphic scripts that developed in China. This diagram shows the character for dragon ( long ) ( Asian Art Museum )

The vocabulary of calligraphy

There are five major script types used today in China. In the general order of their appearance, there are: seal script, clerical script, cursive script, running script, and standard script. Each script type has its own defining visual traits and lends itself to different kinds of textual content and function. Being able to recognize these five script types constitutes the first step in understanding Chinese calligraphy and its nuanced visual vocabulary. As the calligrapher chooses the script type that best suits the occasion of writing and his mood, being able to discern the differences between these types amounts to possessing the key to deciphering the calligrapher’s mind at the moment of creation. An additional reason is that calligraphies had been historically categorized by script type rather than by the content of the text, a fact that highlights the primacy of the visual form in the critical conversations associated with this art.

It is also possible to have more than one script type in the same work of art, usually in the form of colophons (on handscrolls) or inscriptions (on hanging scrolls), as the calligrapher who appended his comments to the original work felt compelled to use a particular type of script.

Seal script title at the start of The Night Revels of Han Xizai 韓熙載夜宴圖, handscroll by Gu Hongzhong 顧閎中. Five Dynasties period, 10th century ( Palace Museum , Beijing)

Seal script —the first script type to emerge in this sequence—was solidified during the Qin dynasty (221–207 B.C.E.). The seal script signified authority, permanence, and orthodoxy, qualities befitting of the first imperial dynasty that unified China and standardized the writing system. Arranged in orderly columns, each character fits in an imaginary square. The strokes are of relatively even thickness, and the speed of execution is steady and slow. The solemnity of the seal script made it (and still makes it) a popular choice for commemorative titles carved onto the head of stone steles for public display or in frontispieces that announce the title of a handscroll painting. Even though this script type was most associated with the short-lived Qin dynasty, it served as the script of choice for titles of artworks such as a 10th-century masterpiece, called T he Night Revels of Han Xizai, that documented a sumptuous party at a court minister’s house.

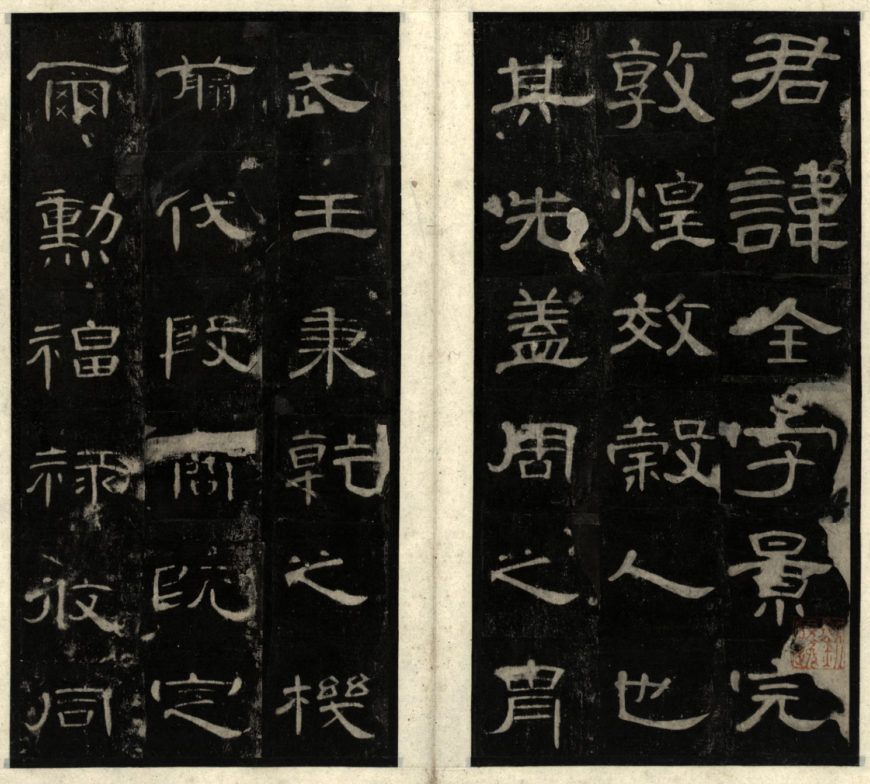

An example of clerical script. Rubbing of the Cao Quan stele (Cao Quan bei 曹全碑), detail, Eastern Han dynasty, 185 C.E. ( National Library of China )

Clerical script reached its height in the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 C.E.). The character in general has a squatter silhouette when compared to its predecessor the seal script, introducing the possibility for greater rhythm in the composition. The strokes start displaying modulations and inflections (note the elegant flaring brush movement in the horizontal strokes), reflective of the different amount of pressure in the brush. This marks the calligrapher’s conscious exploration of the brush’s expressive potential. Clerical script takes less time to write than seal script, and it likely emerged out of a need for more efficient record keeping demanded by an expanding empire (the territory of the Han dynasty was much larger than that under the Qin). The name for the script also suggests that it was initially used by government clerks. The clerical script is popular for commemorative texts carved into stone steles, such as we see on the Cao Quan stele.

An example of cursive script. Huaisu 懷素, Autobiography (Zixu tie自敘帖), detail, Tang dynasty, 8th century (National Palace Museum of Taipei)

Cursive script is the most expressive of all five script types; it affords a calligrapher remarkable freedom thanks to this script’s relaxation of the orthographic constraints of the seal and clerical scripts. Essentially an informal shorthand of the more complex forms of characters, cursive script was widely seen in epistolary writing (correspondence by letter), due to the expedient nature of its execution . Because the characters are more simplified, more freedom is allowed on the calligrapher’s part to improvise and to take more liberty with the shape of the character. Since its maturation in the 4th century, the cursive script has been the choice for many master calligraphers to demonstrate their individuality. Calligraphy done in cursive script readily reveals the speed in which each character was brushed, sometimes so fast that two or more characters are interconnected by ligatures (the fusion of the final stroke of the first character into the first stroke of the second). Some of the most renowned cursive calligraphers were Buddhist monks who often were most inspired in a state of inebriation. Historically, some of the most famous cursive calligraphers were Chan monks, as the expressivity of the cursive script lends itself well to the unrestricted spirit associated with Chan Buddhists. Buddhist monasteries were important centers of learning in premodern China.

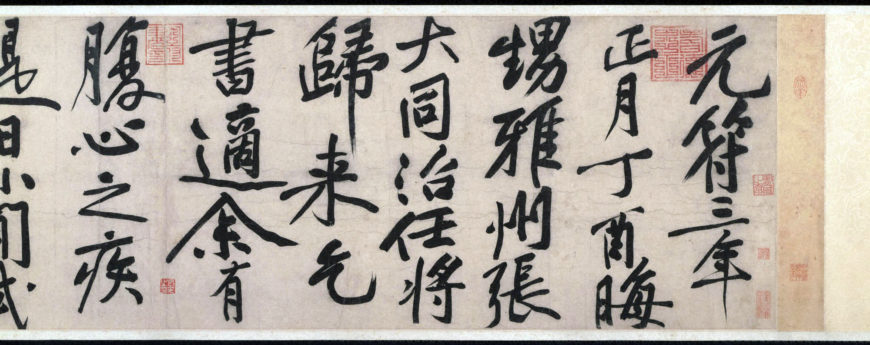

A example of running script. Huang Tingjian 黃庭堅, detail of scroll for Zhang Datong (Zhang Datong tie 張大同帖), (1045–1105), Northern Song dynasty ( Princeton Art Museum Collection )

Running script combines the legibility of standard script and the expressivity of cursive script. The Song dynasty (960–1279 C.E.) with its literati calligraphers (scholar officials who obtained government posts after passing the civil service examination) saw a flowering of calligraphy in running script. This script became the preferred one for the greatest Song calligraphers because it lends itself to the trend at the time towards more personal—even idiosyncratic—styles. Calligraphy in this script type allows a wide range of speed in the execution of the strokes, and gives the calligrapher an opportunity to demonstrate familiarity with great calligraphers of the past. The Chinese calligrapher derives artistic legitimacy by demonstrating mastery of a repertoire of calligraphic styles that constitute the canon of Chinese calligraphy.

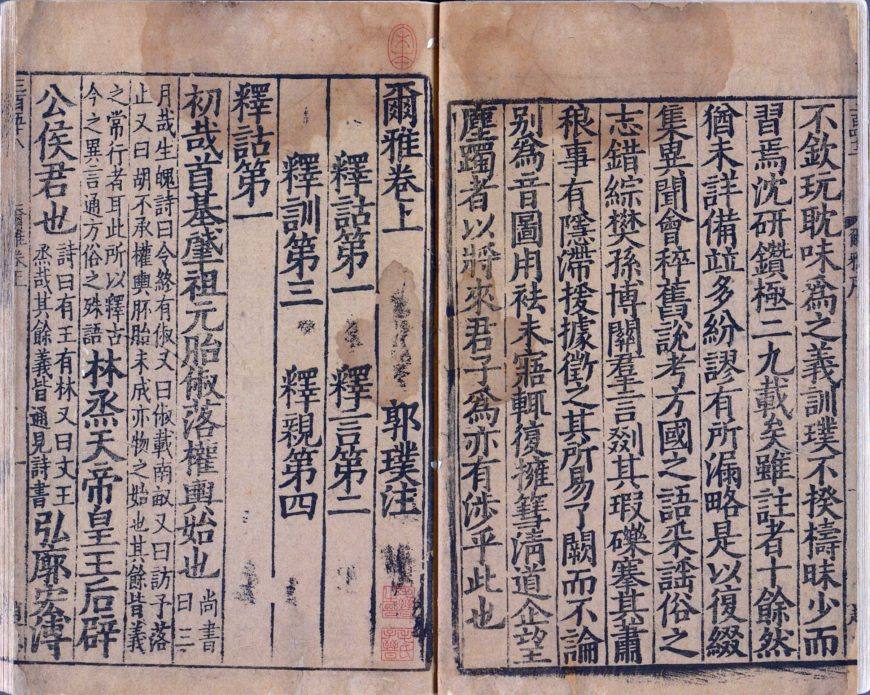

An example of standard script. Erh-ya , annotated by Kuo P’u (Chin Dynasty), Southern Song (1127-1279) (Imprint by the Directorate of Education, National Palace Museum, Taipei )

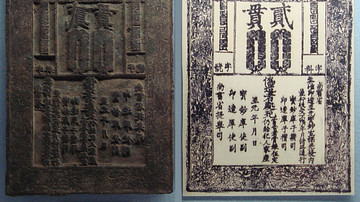

Standard script —the script type that most learners of Mandarin today encounter first during their studies—appeared the latest in the evolutionary sequence of Chinese calligraphy. Standard script reached its zenith during the Tang dynasty (618–907 C.E.) and it is associated with the moral uprightness of the calligrapher, due to its emphasis on the balance around a central axis in its form. It is the ubiquitous script for almost all kinds of printed media in the Chinese language, because it is the most legible of all five script types. Each character can be assembled using a standardized repertoire of brushstrokes that consist mainly of orthogonal (at right angles) strokes, making it fairly easy to reproduce texts in this script type using woodblock printing technology. The world’s earliest extant example of this technology was printed in China in the 7th century, and later during the 11th century (in the Northern Song dynasty) movable-type printing was invented. It is fair to say that the standard script made a unique contribution to the dissemination of knowledge in premodern East Asia.

An important distinction needs to be made between the script type and the style, as within each script type calligraphers further formulate their distinct personal styles.

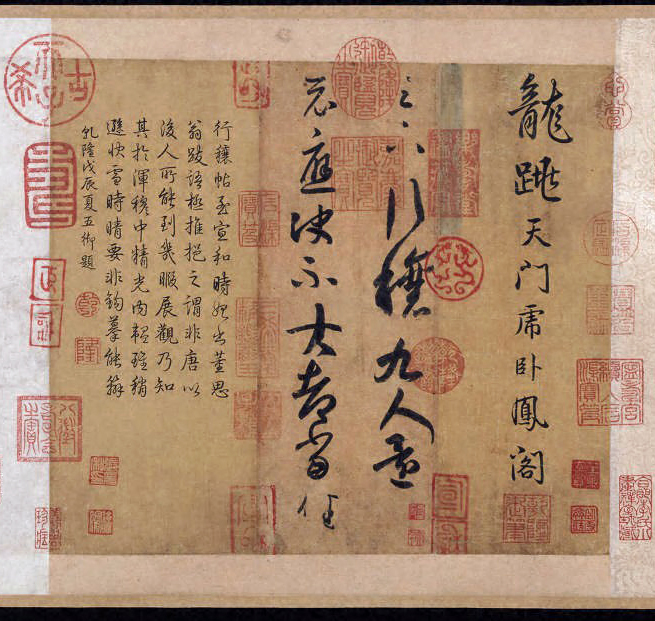

The Crown Jewel of Chinese Calligraphy: Wang Xizhi’s 王羲之 Ritual to Pray for Good Harvest (Xingrang tie 行穰帖 )

Wang Xizhi 王羲之 (303–361) is the most revered calligrapher in the history of East Asia. His works have been venerated since his lifetime. The Ritual to Pray for Good Harvest , currently in the collection of Princeton University Art Museum, is a 7 th -century traced copy of a 4 th -century letter by Wang Xizhi. The calligraphy (the central two lines) has been long celebrated as the crown jewel of Chinese calligraphy: done in cursive, the characters are rhythmic, fluid, and dynamic. The inscriptions in running script that flank Wang Xizhi’s calligraphy were brushed by the Qianlong Emperor (1711–1799), a Manchu ruler of China who upheld these two brief lines of fifteen characters as one of the three best works of calligraphy in his massive and prestigious collection of Chinese art. In so doing, the Qianlong Emperor joined the long list of Chinese emperors who treasured Wang Xizhi’s calligraphy. By endorsing Wang’s calligraphy and the immense cultural capital that this work represents in Chinese history, the Qianlong Emperor, as someone who was ethnically non-Han (he was Manchu), asserted the legitimacy of his rule over China.

Wang Xizhi 王羲之(303–361), detail of Ritual to Pray for Good Harvest (Xingrang tie 行穰帖), 7th-century traced copy of the 4th-century original (Princeton University Art Museum)

Similar to the French saying “Le style c’est l’homme même” (“The style is the man himself”), Chinese have long believed that a man’s calligraphy is capable of revealing his moral qualities and temperaments. An important reason why the Ritual to Pray for Good Harvest has been so treasured in China by generations of collectors is the reputation of Wang Xizhi as an upright scholar and virtuous statesman with a good pedigree. In a world before Instagram and Facebook, a public figure’s image is strongly intertwined with how his calligraphy looks. This is clearly demonstrated by the abiding fascination with Wang Xizhi’s works shared by both Chinese and Japanese emperors, whose unrelenting promotions elevated the Wang Xizhi style as a model with which all later calligraphers felt the need to reckon.

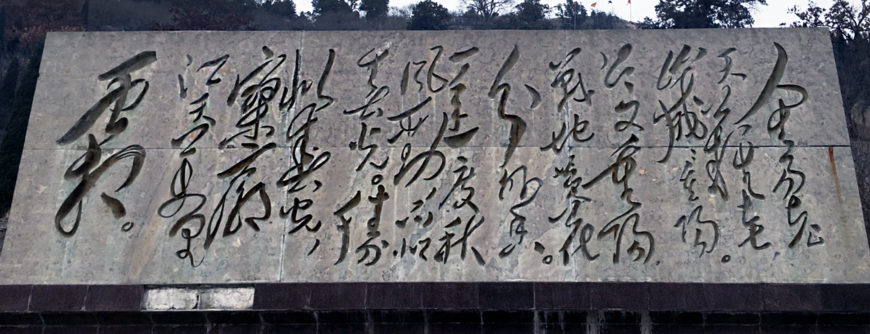

Stone slab with Mao’s calligraphy, China (photo: Xaiohan Du)

On a hiking trip near my hometown in China a few summers ago I encountered this heavy stone slab on which calligraphy has been incised. The calligrapher did not include his name; however, it would not have been necessary—any educated Chinese person would be able to recognize at first glance that this powerful calligraphy in the wild cursive script is brushed by none other than Chairman Mao, thanks to the ubiquitous reproduction of Mao’s calligraphy in textbooks and on major public monuments throughout China. Mao’s unbridled calligraphy could not be further away from the elegant and balanced style of Wang Xizhi, befitting perhaps of his larger-than-life persona and overly romantic vision for China in mid-20 th century. The expressive power of this ancient art of the line continues to occupy a very special place in the visual environment in East Asia.

Appreciating Chinese Calligraphy, Asian Art Museum (2008)

Additional resources.

Link to Wang Xizhi’s Ritual to Pray for a Good Harvest (Princeton University Art Museum).

Fu Shen et al., Traces of the Brush: Studies in Chinese Calligraphy .

Lothar Ledderose, Mi Fu and the Classical Tradition of Chinese Calligraphy ( Princeton University Press, 1979).

Robert E. Harrist, JR. “A Letter from Wang Hsi-chih and the Cultures of Chinese Calligraphy,” in The Embodied Image: Chinese Calligraphy from the John B. Elliott Collection ( Princeton University in association with Harry N. Abrams, 1999).

Cite this page

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

Ancient Chinese Calligraphy

Calligraphy established itself as the most important ancient Chinese art form alongside painting, first coming to the fore during the Han dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE). All educated men and some court women were expected to be proficient at it, an expectation which remained well into modern times. Far more than mere writing , good calligraphy exhibited an exquisite brush control and attention to composition, but the actual manner of writing was also important with rapid, spontaneous strokes being the ideal. The brushwork of calligraphy, its philosophy , and materials would influence Chinese painting styles, especially landscape painting, and many of the ancient scripts are still imitated today in modern Chinese writing .

The highly flexible brushes used in calligraphy were made from animal hair (or more rarely a feather) cut to a tapering end and tied to a bamboo or wood handle. The ink used was made by the writer himself by rubbing a dried cake of animal or vegetable matter mixed with minerals and glue against a wet stone. Wood, bamboo, silk (from c. 300 BCE), and then paper (from c. 100 CE) were the most common writing surfaces, but calligraphy could also appear on such everyday objects as fans, screens, and banners. The best material was paper, though, and the invention of finer quality paper - credited to Cai Lun in 105 CE - helped the development of more artistic styles of calligraphy because its absorbency captured every nuance of the brushstroke.

Methods of Application

A connoisseurship quickly developed, and calligraphy became one of the six classic and ancient arts alongside ritual, music , archery, charioteering, and numbers. Accomplished Chinese calligraphers were expected to use varying thicknesses of brushstroke, their subtle angles, and their fluid connection to each other - all precisely arranged in imaginary spaces on the page - to create an aesthetically pleasing whole.

The historian R. Dawson gives the following description of the attraction of calligraphy created with an expert brush compared to the printed version:

The printed characters are like figures in a Victorian photograph, standing stiffly to attention; but the brush-written ones dance down the pages with the grace and vitality of the ballet. The beautiful shapes of Chinese calligraphy were in fact compared with natural beauties, and every stroke was thought to be inspired by a natural object and to have the energy of a living thing. Consequently Chinese calligraphers sought inspiration by watching natural phenomena. The most famous of all, Wang Xizhi, was fond of watching geese because the graceful and easy movement of their necks reminded him of wielding the brush, and the monk Huai-su was said to have appreciated the infinite variety possible in the cursive style of calligraphy known as grass- script by observing summer clouds wafted by the wind. (201-202)

Calligraphy Scripts

There were five main scripts in ancient Chinese calligraphy:

- Seal script ( zhuan shu ) - in use from c. 1200 BCE

- Clerical script ( li shu ) - from c. 200 BCE

- Regular script ( kai shu , zhen shu or zheng shu ) - from c. 200-400 CE

- Cursive script ( xing shu ) - from the 4th century CE

- Drafting script - ( cao shu ) - from the 7th century CE

Seal script, as its name suggests, was a formal style used for seals and other official documents because it has strokes of an even thickness and fewer direction changes, which made it easier for carvers to reproduce. Clerical script with its heavy stroke endings was also formal and reserved for record keeping by clerks and officials. Later, it became the common script for inscriptions. Both Seal and Clerical script were revived as artistic scripts in the 17th and 18th centuries CE. Regular script was the standard form for printing and remains the most commonly used today. The more flamboyant Cursive script was the most popular choice for artistic expression and used too in the notes added to paintings. Finally, Drafting script, sometimes also called Grass script, was so called because it was the quickest to produce and 'wildest' in that the artist stretched convention to its limits so that some characters become difficult to recognise immediately.

Despite these broad types, each calligrapher's writing style was, of course, his or her own. A calligrapher might aim for precision over spontaneity, prefer flamboyance to grace or concentrate on the spaces left blank within the composition. Besides aesthetic results writing was also judged for other purposes, as the historian M. Dillon here explains:

As a person's writing was regarded as a clue to temperament, moral worth, and learning, emperors of the Tang and Song dynasties often selected their ministers on the basis of the quality of their calligraphy…The life of the calligraphic tradition was sustained by the notion that calligraphy could convey the spontaneous feelings of the truly perceptive individual through an outflowing of spirit at a particular instant. (37)

Famous Calligraphers

Just like in any other art, the most gifted practitioners of calligraphy became famous for their work and their scripts were copied and used in such innovations as printed books. The most revered of all Chinese calligraphers, as mentioned already, was Wang Xizhi (c. 303 - c. 365 CE), although he was a student of Lady Wei (272-349 CE). No examples of either figure's writing survive, except possibly in extant copies of Xizhi's. Wang Xizhi's son, Wang Xianzhi (344-388 CE), was another famous practitioner, the pair often referred to as 'the two Wangs'. Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322 CE) was another celebrated calligrapher who produced such precise characters placed neatly into square boxes on his paper that printers used his script for their own type blocks.

Examples of the scripts and styles created by these masters were often copied onto wood or stone to preserve them and from which ink rubbings ( bei ) were made. Thus, the paper copies could be distributed and the scripts could be imitated by lesser calligraphers everywhere. Such copies were also useful to emperors who wished to promote one style over another during their reign, and they have become an invaluable record of the evolution of Chinese calligraphy which continues to be consulted and imitated today.

Examples of famous calligraphy survive in the form of letters, introductions to books, pieces of prose, religious texts, notes made on paintings, and engraved stele, tombstones and tablets, where the stonemason faithfully copied the work of a noted calligrapher. Examples of fine calligraphy by famous writers were even collected in ancient times, especially in the libraries of emperors or even buried with them in their tombs. So valued were these pieces that forgeries were made and sold as genuine to collectors. As another indicator of the value put on examples of calligraphy by great past masters, the actual meaning of the text is often irrelevant to prices and collectibility. There are many scraps ( tie ) which may be very old and highly valued but are, in fact, merely comments on the weather or a note for a gift of oranges.

Influence on Painting

The techniques and conventions of writing would influence painting where critics looked for the artist's forceful use of brushstrokes, their spontaneity, and their variation to produce the illusion of depth. Another influence of calligraphy skills on painting was the importance given to composition and the use of blank space. Finally, calligraphy remained so important that it even appeared on paintings to describe and explain what the viewer was seeing, indicate the title (although by no means all paintings were given a title by the original artist) or record the place it was created and the person it was intended for. Eventually, such notes and even poems became an integral part of the overall composition and an inseparable part of the painting itself.

There was a fashion, too, for adding more inscriptions by subsequent owners and collectors, even adding extra portions of silk or paper to the original piece to accommodate them. From the 7th century CE, owners frequently added their own seal in red ink, for example, and if a piece changed hands, then the new owner would add their seal so that the history of the work's ownership can sometimes be traced back hundreds of years. Chinese paintings, it seems, were meant to be perpetually handled and embellished with fine calligraphy.

Subscribe to topic Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- Clunas, C. Art in China. Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Dawson, R. The Chinese Experience. Phoenix Press - Orion, 2017.

- Dillon, M. China. Routledge, 1998.

- Rossabi, M. A History of China. Wiley-Blackwell, 2013.

- Tregear, M. Chinese Art. Thames & Hudson, 1997.

- Watson, W. The Arts of China to A.D. 900. Yale University Press, 2000.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language!

Related Content

Ancient Chinese Art

Ancient China

Chinese Writing

Paper in Ancient China

The Art of the Tang Dynasty

Free for the world, supported by you.

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

Recommended Books

| , published by Oxford University Press (2009) |

| , published by Tuttle Publishing (2022) |

| , published by Artpower International (2022) |

| , published by Artpower International (2021) |

External Links

Cite this work.

Cartwright, M. (2017, October 16). Ancient Chinese Calligraphy . World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/Chinese_Calligraphy/

Chicago Style

Cartwright, Mark. " Ancient Chinese Calligraphy ." World History Encyclopedia . Last modified October 16, 2017. https://www.worldhistory.org/Chinese_Calligraphy/.

Cartwright, Mark. " Ancient Chinese Calligraphy ." World History Encyclopedia . World History Encyclopedia, 16 Oct 2017. Web. 21 Jun 2024.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Mark Cartwright , published on 16 October 2017. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Calligraphy

Introduction, general overviews.

- Reference Works

- Premodern Chinese Translations and Guides

- Modern Chinese and Japanese

- American and European

- Origins of Writing

- Applied Study of Calligraphy

- Translations of Premodern Texts

- Anthologies of Premodern Texts

- Illustrated Surveys

- Aesthetic and Critical Terminology

- Material Culture

- Stone Engravings

- Ink Rubbings

- Qin Dynasty, Han Dynasty, and Three Kingdoms Period, 221 bce –280 ce

- The Orchid Pavilion Preface ( Lanting xu ) and the Modern Controversy

- Tang Dynasty, 618–907

- Song Dynasty, 960–1279

- Song-Dynasty Imperial Calligraphy

- Yuan Dynasty, 1279–1368

- Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644

- Qing Dynasty, 1644–1911

- 20th-Century and Modern Calligraphy

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Landscape Painting

- Literati Culture

- Su Shi (Su Dongpo)

- The Chinese Script

- Traditional Chinese Poetry

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Sino-Russian Relations Since the 1980s

- Sino-Soviet Relations, 1949–1991

- Taiwan’s Miracle Development: Its Economy over a Century

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Calligraphy by Amy McNair LAST REVIEWED: 15 January 2019 LAST MODIFIED: 15 January 2019 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199920082-0026

Calligraphy is the art of writing characters with a brush and ink. Yet, the word “calligraphy,” from the Greek kalligraphía (beautiful writing), is something of a mistranslation of the Chinese term shufa (書法), which means “model writing,” or writing that is good enough to serve as a model. Calligraphy has no referent in nature, so all writing is modeled on that of another. Traditional calligraphers were less interested in mere beauty than in the ability of the gesture and the line to create images of aesthetic power and movement and in the paramount issue of upon whose writing they were modeling theirs. The precise moment Chinese characters were born is unknown, but a fully developed system was in use by c . 1200 BCE , as seen on scripts on the incised oracle bones ( jiaguwen 甲骨文) and inscriptions cast into ritual bronze vessels ( guwen 古文) of the Shang dynasty. Over the next millennium, five major script types evolved. The archaic scripts gave way to the “large” seal script ( zhuan 篆) of the Zhou dynasty and the “small” seal script of the Qin. In Qin the clerical script ( li 隸) came into being and flourished during the succeeding Han, whereas by the end of the 2nd century the modern script types of regular ( kai 楷 or zhen 真), running ( xing 行), and cursive ( cao 草) all had developed. Seal and clerical were relegated to decorative and monumental functions until they were revived as antiquarian modes in later times. Although mythic names are associated with the creation of each script type, there were no signed works of calligraphy until the Han dynasty. Since that time, when it began to be seen as expressive of its writer’s personality and character, calligraphy has been accorded the supreme position among the arts. Calligraphers could practice their art purely for their own pleasure or self-expression, or their work could be done for payment or in exchange for goods and services. Calligraphy had a rich tradition until the 20th century, and after China’s turmoil ended in the late 1970s, the amateur scene burgeoned again. In the late 20th century, Chinese calligraphy made a place for itself in the international art world, particularly through the incorporation of nonsense characters in multimedia installations. Critical texts that assessed famous calligraphers appeared in the 4th century, and histories of calligraphy have been written continually from the 5th century to the early 21st century. Japanese scholars have produced excellent research in the 20th and early 21st centuries, and researchers in the West have been writing on calligraphy history since the 1970s.

Each of these overviews has its own approach and strengths. Chiang 1973 lays out traditional Chinese beliefs about aesthetics and techniques. Fong 1999 narrates the history of early calligraphy as a series of great changes in the manner of European art history. Fu 1977 describes techniques of writing and copying, the qualities of each script type, and formats incorporating calligraphy and painting, from the perspective of a practicing calligrapher. Nakata 1983 is organized by type and format of calligraphic writing. Nakata 1970–1972 is devoted to monographic treatments of the most-famous calligraphers. Ouyang 2008 is a reliable college textbook. Tseng 1993 is interesting in that it presents the history of calligraphy from a traditional viewpoint, but it suffers from credulity in the many myths concerning calligraphers and their practices.

Chiang, Yee. Chinese Calligraphy: An Introduction to Its Aesthetic and Technique . 3d ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1973.

Originally published in 1938. Engaging explanation of aesthetics and techniques. Chapter on origin of Chinese characters is not scientific but is an accurate portrayal of traditional Chinese cultural beliefs about writing. Other chapters explain how to use the brush, names of and techniques for producing the individual strokes, principles of composition of characters, and aesthetic principles underlying creativity as seen from Eastern and Western perspectives.

Fong, Wen C. “Chinese Calligraphy: Theory and History.” In The Embodied Image: Chinese Calligraphy from the John B. Elliott Collection . Edited by Robert E. Harrist Jr. and Wen C. Fong, 29–84. Princeton, NJ: Art Museum, Princeton University, 1999.

Survey of the 4th to 18th centuries by the foremost American scholar, employing traditional theoretical approaches of stylistic analysis, personal expression, and history of thought. Using early critical writings and close comparison of individual characters, the author lays out “four calligraphic revolutions”: invention of running script in the Jin dynasty, state-sponsored regular script in the Tang dynasty, individualist styles in the Song dynasty, and revival of regular script in the Yuan dynasty.

Fu, Shen C. Y. Traces of the Brush: Studies in Chinese Calligraphy . New Haven, CT: Yale University Art Gallery, 1977.

Well-illustrated catalogue of an exhibition of calligraphy from two dozen institutions and collectors, mostly American. The author considers techniques and examples of reproduction and forgery; characteristics and famous masters of seal, clerical, cursive, running, and regular script; and formats that integrate calligraphy with painting: hand scroll, colophon, frontispiece, hanging scroll, and album leaf.

Nakata Yūjirō 中田勇次郎. Shodō geijutsu (書道藝術). 24 vols. Tokyo: Chūō kōronsha, 1970–1972.

English translation: Calligraphic arts. Volumes 1 through 10 contain a chronological survey of two dozen canonical Chinese calligraphers, according to the Japanese perspective. For example, Zhang Jizhi is prominent because his connections to Zen in Japan make him of greater importance than in China. Good illustrations, some in color. Includes bibliographic references and an index.

Nakata, Yūjirō, ed. Chinese Calligraphy . Translated by Jeffrey Hunter. History of the Art of China. New York: Weatherhill, 1983.

Brief essays by Nakata (b. 1905–d. 1998) and other important Japanese historians of Chinese calligraphy trace individual formats and types, such as wooden tablets and silk writings, stone inscriptions, Buddhist manuscripts, Chan calligraphy, and separate dynastic periods. Nearly one hundred works, held mainly in Japanese collections, are illustrated in color and explained in detail.

Ouyang Zhongshi. Chinese Calligraphy . Translated and edited by Wang Youfen. Culture and Civilization of China. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008.

A chronological survey of famous calligraphers and masterpieces, from the earliest writings through the 20th century, using mainly works in mainland Chinese collections. Authors are mostly renowned experts from the People’s Republic of China (PRC), so the text has a Marxist-Leninist emphasis on material qualities and social uses of calligraphy, combined with traditional prominence of artists’ biographies.

Tseng Yuho. A History of Chinese Calligraphy . Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 1993.

On the basis of the knowledge of a practicing artist with a traditional education in the history of calligraphy rather than new research, this survey is organized around development of the various script types, including seal, clerical, regular, running, and cursive, as well as talismanic and magic writing.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Chinese Studies »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- 1989 People's Movement

- Agricultural Technologies and Soil Sciences

- Agriculture, Origins of

- Ancestor Worship

- Anti-Japanese War

- Architecture, Chinese

- Assertive Nationalism and China's Core Interests

- Astronomy under Mongol Rule

- Book Publishing and Printing Technologies in Premodern Chi...

- Buddhist Monasticism

- Buddhist Poetry of China

- Budgets and Government Revenues

- Calligraphy

- Central-Local Relations

- Chiang Kai-shek

- Children’s Culture and Social Studies

- China and Africa

- China and Peacekeeping

- China and the World, 1900-1949

- China's Agricultural Regions

- China’s Soft Power

- China’s West

- Chinese Alchemy

- Chinese Communist Party Since 1949, The

- Chinese Communist Party to 1949, The

- Chinese Diaspora, The

- Chinese Nationalism

- Chinese Script, The

- Christianity in China

- Classical Confucianism

- Collective Agriculture

- Concepts of Authentication in Premodern China

- Confucius Institutes

- Consumer Society

- Contemporary Chinese Art Since 1976

- Criticism, Traditional

- Cross-Strait Relations

- Cultural Revolution

- Daoist Canon

- Deng Xiaoping

- Dialect Groups of the Chinese Language

- Disability Studies

- Drama (Xiqu 戏曲) Performance Arts, Traditional Chinese

- Dream of the Red Chamber

- Early Imperial China

- Economic Reforms, 1978-Present

- Economy, 1895-1949

- Emergence of Modern Banks

- Energy Economics and Climate Change

- Environmental Issues in Contemporary China

- Environmental Issues in Pre-Modern China

- Establishment Intellectuals

- Ethnicity and Minority Nationalities Since 1949

- Ethnicity and the Han

- Examination System, The

- Fall of the Qing, 1840-1912, The

- Falun Gong, The

- Family Relations in Contemporary China

- Fiction and Prose, Modern Chinese

- Film, Chinese Language

- Film in Taiwan

- Financial Sector, The

- Five Classics

- Folk Religion in Contemporary China

- Folklore and Popular Culture

- Foreign Direct Investment in China

- Gender and Work in Contemporary China

- Gender Issues in Traditional China

- Great Leap Forward and the Famine, The

- Guomindang (1912–1949)

- Han Expansion to the South

- Health Care System, The

- Heritage Management

- Heterodox Sects in Premodern China

- Historical Archaeology (Qin and Han)

- Hukou (Household Registration) System, The

- Human Origins in China

- Human Resource Management in China

- Human Rights in China

- Imperialism and China, c. 1800–1949

- Industrialism and Innovation in Republican China

- Innovation Policy in China

- Intellectual Trends in Late Imperial China

- Islam in China

- Jesuit Missions in China, from Matteo Ricci to the Restora...

- Journalism and the Press

- Judaism in China

- Labor and Labor Relations

- Language, The Ancient Chinese

- Language Variation in China

- Late Imperial Economy, 960–1895

- Late Maoist Economic Policies

- Law in Late Imperial China

- Law, Traditional Chinese

- Li Bai and Du Fu

- Liang Qichao

- Literature Post-Mao, Chinese

- Literature, Pre-Ming Narrative

- Liu, Zongzhou

- Local Elites in Ming-Qing China

- Local Elites in Song-Yuan China

- Macroregions

- Management Style in "Chinese Capitalism"

- Marketing System in Pre-Modern China, The

- Marxist Thought in China

- May Fourth Movement

- Media Representation of Contemporary China, International

- Medicine, Traditional Chinese

- Medieval Economic Revolution

- Middle-Period China

- Migration Under Economic Reform

- Ming and Qing Drama

- Ming Dynasty

- Ming Poetry 1368–1521: Era of Archaism

- Ming Poetry 1522–1644: New Literary Traditions

- Ming-Qing Fiction

- Modern Chinese Drama

- Modern Chinese Poetry

- Modernism and Postmodernism in Chinese Literature

- Music in China

- Needham Question, The

- Neo-Confucianism

- Neolithic Cultures in China

- New Social Classes, 1895–1949

- One Country, Two Systems

- One-Child Policy, The

- Opium Trade

- Orientalism, China and

- Palace Architecture in Premodern China (Ming-Qing)

- Paleography

- People’s Liberation Army (PLA), The

- Philology and Science in Imperial China

- Poetics, Chinese-Western Comparative

- Poetry, Early Medieval

- Poetry, Traditional Chinese

- Political Art and Posters

- Political Dissent

- Political Thought, Modern Chinese

- Polo, Marco

- Popular Music in the Sinophone World

- Population Dynamics in Pre-Modern China

- Population Structure and Dynamics since 1949

- Porcelain Production

- Post-Collective Agriculture

- Poverty and Living Standards since 1949

- Printing and Book Culture

- Prose, Traditional

- Qing Dynasty up to 1840

- Regional and Global Security, China and

- Religion, Ancient Chinese

- Renminbi, The

- Republican China, 1911-1949

- Revolutionary Literature under Mao

- Rural Society in Contemporary China

- School of Names

- Silk Roads, The

- Sino-Hellenic Studies, Comparative Studies of Early China ...

- Sino-Japanese Relations Since 1945

- Social Welfare in China

- Sociolinguistic Aspects of the Chinese Language

- Sun Yat-sen and the 1911 Revolution

- Taiping Civil War

- Taiwanese Democracy

- Technology Transfer in China

- Television, Chinese

- Terracotta Warriors, The

- Tertiary Education in Contemporary China

- Texts in Pre-Modern East and South-East Asia, Chinese

- The Economy, 1949–1978

- The Shijing詩經 (Classic of Poetry; Book of Odes)

- Township and Village Enterprises

- Traditional Historiography

- Transnational Chinese Cinemas

- Tribute System, The

- Unequal Treaties and the Treaty Ports, The

- United States-China Relations, 1949-present

- Urban Change and Modernity

- Vernacular Language Movement

- Village Society in the Early Twentieth Century

- Warlords, The

- Water Management

- Women Poets and Authors in Late Imperial China

- Xi, Jinping

- Yan'an and the Revolutionary Base Areas

- Yuan Dynasty

- Yuan Dynasty Poetry

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [81.177.182.154]

- 81.177.182.154

Chinese Calligraphy

Chinese Calligraphy is a traditional form of writing characters from the Chinese language through the use of ink and a brush. It is a tradition that is rooted in China through centuries of practice.

Chinese calligraphy is an art of turning Chinese characters into images through pressure and speed variations of the pointed Chinese brush. It emphasizes the expression of emotions while being a mental exercise to an artist which coordinates the body and the mind to select the best styling for the presentation of the passage content.

In English, "calligraphy" literally means "beautiful writing." It is one of the Chinese traditional arts and a written form that unites the languages spoken in China. It is seen on the walls of offices, shops, hotels, and houses everywhere.

Picasso, the world-famous master of art, once expressed: "If I once lived in China, I must had become a calligrapher rather than a painter".

The History of Chinese Calligraphy

Chinese calligraphy has an extensive history of about 1,000 years. It is a unique artistic form of Chinese cultural treasure and represents Chinese art. It is reputed to be the most ancient artistic type in oriental world history.

Calligraphy initially began due to the need to record ideas and information. The unique forms of calligraphy developed and originated from China, particularly for writing Chinese characters by using ink and a brush. Furthermore, Chinese calligraphy is responsible for the development of numerous forms of art such as ornate paperweights, ink stones, and seal carving.

The revivalist calligraphers of the Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368) such as Zhao Mengfu (1254–1322) further developed the popular classical traditions of the Tang (618–907) and Jin (1115–1234) dynasties.

In the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) , the notions of artistic liberation and freedom from calligraphy rules gained momentum. During this period calligraphers started to form individual paths with their own styles. The most popular calligraphers are such as; Wen Zhengming (文徵明, 1470–1559), Zhang Ruitu (張瑞圖, 1570–1641), Zhu Yunming (祝允明, 1460–1527), and Huang Daozhou (黃道周, 1585–1646).

During the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), scholars started turning to inspiration from the ancient works' rich resources inscribed in clerical and seal script. The Qing scholars were interested in studying these antiquities and becoming familiar with the steles that facilitated the creation of a calligraphy trend, which acted as a complement to the 'Model Book' school. Therefore, the Stele school became a link between the present and the past in the approach to the traditions which the clerical and the seal script began being the Chinese calligraphy innovation sources.

Calligraphy Masters

Zhong Yao (鍾繇,151-230): He is known as the "father of standard script". His famous works include the Xuānshì Biǎo (宣示表), Jiànjìzhí Biǎo (薦季直表), and Lìmìng Biǎo (力命表), which survive through hand copies, including those by Wang Xizhi.

Wang XiZhi (王羲之, 303-361): He was traditionally referred to as the Sage of Calligraphy during the Jin Dynasty. Although none of his work remains today and all of his masterpieces which you see were copied or traced by others

Ouyang Xun (歐陽詢, 557–641): He was a Confucian scholar and calligrapher of the early Tang Dynasty.

Cai Xiang (蔡襄, 1012–1067): He was one of the four best calligraphers during the Song Dynasty (960–1279).

Zhao Mengfu (赵孟頫, 1254–1322): He was a prince and descendant of the Song Dynasty , and a Chinese scholar, painter, and calligrapher during the Yuan Dynasty.

Categories of Chinese Calligraphy

There are five main categories of traditional Chinese calligraphy:

1. Seal script - zhuan shu

Small or large, Chinese seal script is a script that was designed to be engraved. It is the oldest script but it is still used because it has remained to be popular. During some time in the Qing Dynasty, seal script faced a renaissance as an act of rebellion against the invaders because of the desire to understand and rediscover the roots of the Chinese culture. The script uses ancient characters that are difficult to read especially for modern Chinese.

2. Clerical script - li shu (pron. lee shoo)

Also referred to as the chancery script. The script was adopted as a way of simplifying brushstrokes. it is a legible script today despite being established during the Han dynasty.

3. Regular script - kai shu (pron. keye shoo)

Emerging at the end of the Han dynasty, in the 3rd century A.D., regular script was the result of another effort to simplify writing, decreed by the last emperor of this dynasty. It is the easiest to read and is very suitable for learning calligraphy. The brushstrokes are clearly drawn.

4. Running script - xing shu (pron. hsing shoo)

Also known as the semi-cursive script since it is halfway between regular and cursive. Running script and regular script are the most popular styles today. The strokes in each character are connected and simplified, which makes writing faster. However, the characters remain separate from each other.

5. Cursive script - cao shu (pron. tsao shoo)

Literally "grass" or "straw" script, the Chinese also call it "mood writing." All the strokes for a single character are shortened and linked together; most of the time, the characters run into each other, making them practically illegible for modern Chinese.

The other scripts had to follow restrictive rules generally imposed by the imperial authority, although this did not keep artists from excelling. While this style seems surprisingly modern due to the virtuosity and abstract nature of the brushwork, it is not modern at all. It emerged at a time of great social unrest at the beginning of the Han dynasty, around 200 B.C., as a revolt against authority. It was a way for intellectuals to express their desire to depart from the beaten track.

The Four Treasures of the Study

The four components of penmanship in Ancient China, also known as 'the four treasures of study ' were employed by scholars throughout ancient China. Here is a brief insight into the four tools of the trade:

1. Writing Brush

The handles for Chinese brushes are made of hardwood, ivory, porcelain, or bamboo, with the bristles made from rabbit's hair, wools, horsehair, or the hair of wolves, foxes, etc.

It must have a fine texture and the right absorbency. Modern glossy paper is no good.

3. Ink Stick

The ink stick is a block of dried ink dye. It looks like a large black domino and is used by most calligraphers. Ink sticks or pre-made bottled ink can be purchased in bookshops or other vendors.

4. Ink Slab

The flat, hard slab is made from stone or pottery. The ink slab is made from stone or pottery used in Chinese calligraphy and painting for grinding dry ink and mixing with water. In China, there are four famous Chinese ink slabs: Anhui She Ink slab, Gansu Tao Ink slab Gansu, Guangdong Duan Ink Slab and Shanxi Chengni Ink Slab.

Where to See/Learn Calligraphy in China

Museums: The Beijing Capital Museum, China Art Gallery, Beijing Museum of Cultural Relics Exchange, The Imperial City Art Museum and many more exhibition centers.

Bookstores: Books which are devoted to calligraphy can be found in various Beijing bookstores like; The Bookworm, Yansha Books and Wangfujing Foreign Language Bookstore

Temples: Chinese Calligraphy is written on temples like the Temple of Heaven, Lama Temple, Beijing Temple Fair, and the Confucius Temple. In addition, name plaques, shops, main doors or even modern door houses also serve as an ever-present part of Chinese culture. So, on your trip to China makes sure to get yourself one.

Our Top 5 Recommendations for Calligraphy Schools in China

If you are a foreigner in China and you are interested in learning this artistic expression, the best way for you to learn Chinese calligraphy is to find a school in China.

1. Beijing Calligraphy School

This is a new educational organization of self-study examination of higher education for students of Chinese calligraphy majors. It provides various forms and strong faculty force which gathered the elite of Beijing calligraphy education and gets credit for its high quality. Since the year it is found in 2005, it has satisfied the majority of calligraphy lovers' eager to promote the education of calligraphy and improved the popularity and improvement of calligraphy education.

2. Beijing Calligraphy Training College

Located in the Royal Courtyard, near the Forbidden City and Tiananmen Square, it is a Holy Land of China cultural and historical capital. In recent years, the college has trained a large number of outstanding international artists. On behalf of the college, students go abroad for cultural exchanges and hold personal calligraphy and painting exhibitions and trade shows in more than 20 countries, bringing the real value and social and economic benefits to the works.

3. Hangzhou Chuanxiao Calligraphy School

It is the only specialized training school teaching the art of calligraphy in Hangzhou. Since the year 1993, it has been continued to carry forward the art of calligraphy and the universal education of calligraphy, which won the general public approved particularly the majority of the students and parents. Sponsoring more than 10 years, it has been insisting on taking the perfect line, trying to find a new set of calligraphy education models, and is equipped with specially prepared textbooks.

4. Yunying Calligraphy School in Tianjin

Located in Tianjin Nankai Primary School, it covers three learning contents of regular script, running script and grass script with a writing brush and hard pen. Use the works of well-known calligrapher Zhang Tianyun and Zhang Tianying as the main teaching materials and the writings of the ancient tablet as the model. Their teachers are the outstanding ones in the field of Chinese calligraphy.

5. Xizhi Calligraphy and Painting School

It is a pioneer of Chinese calligraphy and painting training education and an outstanding contribution to the inheritance and popularity of Chinese painting and calligraphy. Now it has become a gold brand of national concatenate education and enjoys a good reputation.

Artistic Characters and rules:

Chinese calligraphy serves the purpose of conveying thought but also shows the 'abstract' beauty of the line . Rhythm, line, and structure are more perfectly embodied in calligraphy than in painting or sculpture.

- Every Chinese character is built up in its own square with a variety of structure and composition.

- The drawing consists of only three basic forms: the circle, the triangle, and the square.

- For each character, there is a definite number of strokes and appointed positions for them in relation to the whole. No stroke may be added or deleted for decorative effect.

- Strict regularity is not required.

- The pattern should have a living movement

We Can Help You Learn Calligraphy

Like all our private tours, finding the opportunity to learn calligraphy is fully-customizable to suit your requirements. You can simply tick the boxes and fill in the blanks on our Create My Trip page , and we will design a unique tour for you to include any of the places above.

We offer an introductory class to learn basic Chinese calligraphy in a beautiful Beijing hutong. You will be given a basic introduction to calligraphy and learn how to draw simple characters under the guidance of our teacher. All drawing tools such as brushes, ink, and paper are provided. This class can be tailor-made to suit your experience.

- 11-Day China Classic Tour

- 3-Week Must-See Places China Tour Including Holy Tibet

- 8-Day Beijing–Xi'an–Shanghai Private Tour

- How to Plan Your First Trip to China 2024/2025 — 7 Easy Steps

- 15 Best Places to Visit in China (2024)

- Best (& Worst) Times to Visit China, Travel Tips (2024/2025)

- How to Plan a 10-Day Itinerary in China (Best 5 Options)

- China Weather in January 2024: Enjoy Less-Crowded Traveling

- China Weather in March 2024: Destinations, Crowds, and Costs

- China Weather in April 2024: Where to Go (Smart Pre-Season Pick)

- China Weather in May 2024: Where to Go, Crowds, and Costs

- China Weather in June 2024: How to Benefit from the Rainy Season

- China Weather in July 2024: How to Avoid Heat and Crowds

- China Weather in August 2024: Weather Tips & Where to Go

- China Weather in September 2024: Weather Tips & Where to Go

- China Weather in October 2024: Where to Go, Crowds, and Costs

- China Weather in November 2024: Places to Go & Crowds

- China Weather in December 2024: Places to Go and Crowds

Get Inspired with Some Popular Itineraries

More Travel Ideas and Inspiration

Sign up to our newsletter.

Be the first to receive exciting updates, exclusive promotions, and valuable travel tips from our team of experts.

Why China Highlights

Where Can We Take You Today?

- Southeast Asia

- Japan, South Korea

- India, Nepal, Bhutan, and Sri lanka

- Central Asia

- Middle East

- African Safari

- Travel Agents

- Loyalty & Referral Program

- Privacy Policy

Address: Building 6, Chuangyi Business Park, 70 Qilidian Road, Guilin, Guangxi, 541004, China

Taoism and Chinese Calligraphy Development Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Chinese philosophy and development of chinese calligraphy, taoism and chinese calligraphy, works cited.

Chinese calligraphy is one of the premier practices of Chinese art and is considered an essential feature of Chinese culture. This technique is used by the artists to transmit their thought, and at the same time, present the abstract magnificence of the line. Chinese calligraphy presents rhythm as well as line and structure in a strong and flawless manner. Calligraphy requires a quiet mind and deep concentration. The beauty of calligraphy is realized only when we combine the expressions of the words with the external resemblance (“Calligraphy”, par.1).

In his lecture at Independence High School, Charlotte, U.S, the Director of the Confucius Institute at Pfeiffer University, , Prof. Yan emphasized the need to learn Chinese calligraphy for the proper understanding of traditional Chinese philosophy. According to him, “Both practicing Chinese calligraphy and the ways to appreciate it embody Chinese philosophy” (qtd. in Tu, par.6).

Chinese calligraphy is an expression of the calligrapher’s thoughts, hence, it promotes creativity. It allows the writer to think from different point of views. It also helps in establishing a systematic connection of thoughts (Tu par.7).

Chinese historical records reveal that Chinese calligraphy originated in its real form somewhere between the second and fourth century. Chinese civilization has evolved through several dynasties and Chinese calligraphy has also developed with this course of development. Initially, during the Shang Dynasty period, it emerged in the form of Shell bone writing known as Jiaguwen, and bronze inscriptions called Jinwen.

Later, it evolved to regular hand called Kaishu and running hands called Xingshu during the Three kingdoms period. In course of time, the art converted to the mainstream with the advancement of cursive hand known as Caoshu, running hand referring to Xingshu and regular script known as Kaishu These styles took place of the seal script and the official script. Several calligraphers such as Ouyang Xun, Liu Gongquan emerged with their different styles during this period. Wang Xizhi was the most prominent calligrapher of that time. He inspired several upcoming calligraphers even until the Tang Dynasty with his creative accomplishments.

During Tang Dynasty, this art flourished and significant theories on Chinese calligraphy were published. The succeeding periods of Five Dynasties and Yuan Dynasty had to witness great political turmoil. The disturbances caused by wars and political unrests, definitely, had an adverse impact on the development of calligraphy. However, Ming Dynasty and Qing Dynasty again saw the booming of calligraphy as an art and produced important calligraphic pieces that inspired the later generations of calligraphers (Ren, par.2).

Thus, Chinese calligraphy evolved through several dynasties and established as an art having five main calligraphic styles:

- Seal Script (ZhuanShu): This style is considered to be an early style that resemble with a picture.

- Official Script (Li Shu): It was developed during 722-230BC. The characters are similar to the present Chinese characters.

- Regular Script style (Kai Shu): It is the most common style and is used for printing purposes.

- Running Script style (Xing Shu): This style is applied in handwriting.

- Swift Script style (Cao Shu): This style is also used in handwriting and allows easier and smooth flow in style. The strokes in calligraphy are perpetual and persistent; hence, require cautious planning and assured application (Li 194).

Chinese calligraphy has bloomed through several years and is practised by more people in China when compared to the other forms of art. However, past few decades have witnessed a significant and sweeping change in the art of calligraphy. This ancient valued art has gone through the most vibrant developments.The classic Chinese philosophies mainly, Taoism, Zhuangism, and Confucianism have a great influence on Chinese calligraphy.

The basic principles of Chinese calligraphy represent the Taoist perception. Further, the abstract beauty of Chinese calligraphy is also an interpretation of the basic principles of Taoism. The Confucian line elucidates mainly the social and moral values.Zhuangism underlines the notion that perfection can be attained through practice; however, it also supports the idea of spontaneity and free expression. These ideas have been the prominent basis of interpreting Chinese calligraphy of late (Wu and Murphy 320).

The idea of Tao as the basic principle of calligraphy is to have harmony of the calligrapher and the nature. In the second century, developments in philosophy and literature gave way to the involvement of pure aesthetics in the Chinese calligraphy. It was then considered more than merely a skill and was associated with the aesthetics of the human spirit. Ti’ai Yung was a great scholar and calligraphist of the second century who laid down the principle that calligraphy is stimulated by one’s internal calmness. He said that the desire of creativity or idea of writing comes from within and calligraphy is a medium through which one can release one’s self.

According to him meditation and contemplation help in bringing spontaneity and naturalness to one’s brush- work. Ts’ai Yung’s idea of meditation and contemplation for the utmost accomplishment in art is influenced by the Taoist teachings. According to Chang Yen-Yuan of the Tang Period, Ts’ai was the one, who originated Chinese calligraphy as an art and taught it to his daughter Wen Chi. Thereafter, it was passed on to many teacher- pupil generations. In the seventh century, Yu Shih-nan expanded the Taoist philosophy on calligraphy. According to him, “Calligraphy contains the essence of art. The action of moving the brush follows the principle of wu-wei (non-assertion). Based upon the idea of Yin and Yang (non-action and action), the brush moves and stops” (qtd.in Chang 261).

Harmony of Yin and Yang form the basis of Taoist philosophy.According to Tao percept Yin and Yang (qi) is the foundation of life and keeps it moving. Ying and Yang symbolise that dualities in nature are complimentary to each other.Chinese calligraphy highlights qi in all its strokes and characters that makes the piece of calligraphy vigorous and sprightly. Taoism stresses that a calligrapher requires having qi from the beginning till the execution of the work.

The famous artist XieHo established a new concept of extending qi into qiyun that referred to the rhythmic and lively motion of qi. The theory of qiyun was basically meant for the art of painting, however, it has a significant influence on Chinese calligraphy. The excellence of the calligraphic work is attained by moving one’s mind into the state of tranquillity or xukong. This typical Taoist percept emphasises that the state of tranquillity can be achieved by withdrawing oneself from the worldly affairs (Wu and Murphy, 321).

Chinese philosophy asserts that the calligraphist or any other artist could attain the utmost level of accomplishment through transformation of the mind. According to Yu Shih-nan, “The art of calligraphy is mystical and subtle. It bases itself on the spiritual infusion, not upon artificial exertions. It requires the enlightenment of one’s mind but not sense perception” (qtd.in Chang 261).

Tao is the law of nature that guides the Chinese people to understand the philosophical and secret principles. Chinese writing or calligraphy represents Taoist aesthetic ideology while presenting the distinctive features of Chinese arts. According to Li, those features include, “high symbolism, simplicity, idealism, abstraction, and delicate refinement in cooperative harmony” (192).

Chinese calligraphy requires the calligrapher to establish coordination between his mind and body to implement the best style for presenting the subject. Thus, it benefits the calligrapher with vital mental workout. Li mentions that “A Chinese calligrapher has to sit upright, and has his elbow resting the desk with the arm, the wrist, and full five fingers acting in concert to control the movement of the brush. It is the most relaxing yet highly disciplined exercise, yielding benefits for one’s physical well-being” (194).

Calligraphy is helpful in the refinement of one’s personality. A calligrapher learns several personality traits like self-control, patience and perseverance through the practice of calligraphy. Chinese history provides evidences of Chinese calligraphers who have got benefitted with this art and lived long and vibrant lives. Chinese calligraphy has been a popular art that has not restricted to the Chinese borders. Many other countries of Southeast Asia such as Japan and Korea assimilated Chinese calligraphy into their cultures; however they established their own schools and styles in course of time.The west was also influenced by the sparkle of Chinese calligraphy.

Famous artists such as Picasso and Matisse acknowledged that they were highly impressed by Chinese calligraphy.Picasso went to the extent of saying that he would have grown into a calligrapher rather than a painter, had he initiated with the knowledge of Chinese calligraphy. Henri Matisse’s work also shows influences of Chinese calligraphy and strokes (Li 195).

Calligraphy. 2008. Web.

Chang, Chung-Yuan, Creativity and Taoism , London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. 2011. Print

Li,You-Sheng. A new interpretation of Chinese Taoist philosophy . Canada:Taoist Recovery Center. 2005. Print

Ren, Jessie 2003 . History of Chinese Calligraphy . Web.

Tu Lingli, 2011, Learning Chinese calligraphy and understanding Chinese philosophy . Web.

Wu, Dingbo and Murphy, Patrick D. Handbook of Chinese popular culture . USA: Greenwoood Press. 1994. Print

- Islamic Scripts: Ilkhanid Period

- Chinese Culture: Chinese Calligraphy Art

- Calligraphy Inscription in Islamic Architecture and Art

- Aristotle’s Virtue Theory vs. Buddha’s Middle Path

- Kant's Third Antinomy in Philosophical Thought

- Religious Pluralism and Tolerance

- The Medieval Ages Philosophy

- Clarke's Cosmological Argument

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, August 19). Taoism and Chinese Calligraphy Development. https://ivypanda.com/essays/taoism-and-chinese-calligraphy-development/

"Taoism and Chinese Calligraphy Development." IvyPanda , 19 Aug. 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/taoism-and-chinese-calligraphy-development/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Taoism and Chinese Calligraphy Development'. 19 August.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Taoism and Chinese Calligraphy Development." August 19, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/taoism-and-chinese-calligraphy-development/.

1. IvyPanda . "Taoism and Chinese Calligraphy Development." August 19, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/taoism-and-chinese-calligraphy-development/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Taoism and Chinese Calligraphy Development." August 19, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/taoism-and-chinese-calligraphy-development/.

- China Daily PDF

- China Daily E-paper

- Music&Theater

- Film&TV

- Events&Festivals

- Cultural Exchange

- Living Heritage

Living Heritage: Chinese calligraphy

Chinese calligraphy is an artistic practice of writing Chinese characters, often with a brush and ink on xuan paper. The evolution of Chinese calligraphy began alongside the earliest Chinese characters discovered to date - inscriptions on oracle bones from the Shang Dynasty (c.16th century-11th century BC) in Anyang, Henan province. Over time, calligraphy gradually took shape as a form of art rather than a mere means of record. The five major styles of script, running, cursive, official, seal and regular, were born from such calligraphy.

Calligraphy is a demanding and advanced art. The type of brush, density of ink and texture of paper can all alter the output. From brush inclination and direction to speed of writing, every twist and turn of the wrist is also calculated. Structure of individual characters and spatial layout as a whole determine its quality. Moreover, it is said that the emotions and philosophy of the writer are directly reflected on calligraphy.

Calligraphy is refined art. Lan Ting Xu ( The Orchid Pavilion Preface ), created by Wang Xizhi during the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317-420), is one of the most celebrated masterpieces of Chinese calligraphy. Its elegance and expressive brushwork bestowed it both historical and cultural significance in Chinese literature. Calligraphy is also within reach. Like the spring festival couplets that adorn doors of everyday folks, calligraphy has always been the embodiment of aesthetic appreciation for the Chinese.