Food Insecurity Essay

Food Insecurity Nutrition is important for healthy life. Many people are still hungry around the world even though there is mass production of food. This is because of unhealthy food production. In today’s world we see many obese people because of high intake of high fat and cholesterol containing food . It is important to have a healthy diet/ nutritional intake for individuals to have good foundation for physical and mental health. Now a day’s healthy food is getting more expensive rather than unhealthy food. Poor people are forced to eat unhealthy food, while the rich can afford to eat whatever the please. Food insecurity is caused by individuals not having healthy food for their families due to their low income or political and …show more content…

Even in developed country like The United States of America food security is a major problem. In the article “Association of Household and Community Characteristics with Adult and Child Food Insecurity among Mexican-Origin Households in Colonias along the Texas-Mexico Border” author Sharkey et.al supports that over population of Mexicans, living in colonies along the Texas - Mexico border causes food insecurity. Because of the Overpopulation on the texas-mexico border there is low availability of healthy food, causing people to eat junk food which lacks of nutritional value, and has high amount of sugar, fat, cholesterol. Food insecurity causes health issues such as obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and early mortality among young single mothers. According to author Christine A. Stevens young single mothers are affected by food insecurity in two ways “first, the stress of food insecurity can lead to compounding issues of depression for this mother, second, food choice.” Factors that assist these problems are socioeconomic status and the ability to obtain adequate nutrition . These young single mothers do not have enough money to give nutritional food to their families. With limited money they do not have a choice for nutritional food and according to Stevens are forced to buy “inexpensive, high fat, high carbohydrates food” (Stevens 163). In

Food Insecurity In Australia Essay

The global population is expected to reach 9 billion people by the year 2050 and scientific projections indicate that world is on a trajectory towards an environmental and global food crisis. World Leaders, environmental enthusiasts and aid agencies have cause for alarm as they support urgent policies for change, for without them mankind will face unprecedented food insecurity. In 2015 estimates were that there were “some 795 million people” [World Food Programme, 2015], experiencing food insecurity and 3.1 million children under 5 died through malnutrition, while Australians continue to waste an estimated 361 Kg’s of food per person per yr [PMSEIC, 2010, p.44] All the while the earth groans under the weight of Greenhouse Gas Emissions [GHG], deforestation, soil degradation and

School lunches are often unsung heroes of many modern American households. Frequently overlooked and disregarded because of their stigma, school lunches are a key ingredient that may help make the world a better place. Unknowingly, great numbers of individuals in our communities deal with food insecurities every day of their lives. It baffles me that in an advanced society many people do not have the resources to provide food for themselves or their families. Until it affected me personally, I was unaware nor passionate about the struggles of food insecurity. My passion for solving food insecurity in my local community has led me to gain both experience and leadership through understanding and advocating for those around me.

Listening to conversations about food on campus, I found that there was a common theme last year: it was difficult to find healthy food on campus.

Poverty and Nutrition in America Essay

- 9 Works Cited

For most Americans, the word poverty means insufficient access to to housing, clothing and nutritious food that meet their needs for a healthy life. A consequence of poverty is a low socioeconomic status that leads to being exposed to poor nutrition. Since food and dietary choices are influenced by income, poverty and nutrition go hand in hand. There are many important factors that threaten the nutritional status of poor people. The number one factor is not having enough money to buy food of good quality and quantity. Not having enough money can have a profound impact on the diets of low-income people. Limited financial resources may force low income people to make difficult decisions about what kind and how much food to buy. Limited

Food insecurity is defined as the inadequate access to nutritious food and is simply represented by the orange slice on the plate. The unhealthy products (i.e., processed meat and non-perishable items) further emphasize food insecurity by showing the population’s unhealthy, yet

Food Insecurity : The Lack Of Access For Enough Food For Adequate Nutrition

Food insecurity is defined as “the lack of access to enough food to ensure adequate nutrition.”1 The Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service (ERS) reported that 14.6% of US households were food insecure during at least some portion of 2008 (up 11.1% from 2007), the highest levels recorded since monitoring began in 1995.2 Food insecurity is a concern of under consumption and obesity is a disease of over consumption, yet both outcomes may coexist, seemingly incongruously, within the same household.2 The most popular explanation is that low-cost, energy-dense foods linked to obesity are favored by financially constrained households, who are the most likely to be food insecure.2 Another theory, focusing on environmental context net of individual circumstance, argues that obesity and insecurity are both symptoms of malnutrition, occurring in neighborhoods where nutritious foods are unavailable or unaffordable.2 A separate literature researches environmental roles in poor nutritional outcomes, recent studies link obesity as well as atherosclerosis and diabetes to the food environment, the local context of available food items.2 The theory is that local inaccessibility to healthy foods influences diet composition, a claim supported by evidence.2 Especially in poorer neighborhoods, food options are often limited to fast food restaurants, convenience stores, or grocery stores more poorly stocked both in

Food Insecurity At The United States Essay

Did you know in 2014, 48.1 million households in the United States were food insecure? (Feeding America, 2016) Additionally, household with children reported higher rates of food insecurity compared to households without children. According to new research, a great proportion of college students are suffering from food insecurity (Hughes et al., 2011; Patton-Lopez et al., 2014). According to the United States Department of Agriculture, food insecurity is defined by “the state of being without reliable access to sufficient quantity of affordable nutritious food” (2015). Since 2006, the USDA introduced new terms to categorize food insecurity ranges. Marginal food security is described as “anxiety over food sufficiency or shortage of food in the house. Little or no change in diet” (Gaines et al., n.d.). Low food security “reduced quality, variety, or desirability of diet without reduced food intake. Very low food security “disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake.”

Food Deserts

Food insecurity is a determent to health that has become more prevalent in low-income areas of the country. Food security is an important aspect of public health in which greater evidence is showing that food insecurity as a direct link to poor health. Food insecurity can be define as “the inability to acquire or consume and adequate diet quality or sufficient quantity of

Food insecurity is a major issue in Canada, affecting millions people across the country especially minorities. In 2012, four million Canadians experienced some form of food insecurity (Tarasuk, Mitchell, & Dachner, 2014). This paper aims to focus on how food insecurity affects women and children, and the costs associated with it. The results of food insecurity can be serious mental, and physical health problems for women and children. It shall demonstrate the need for government intervention, job security, prices of food, and public policies to protect low income families. This topic was chosen as it is an issue which often gets overlooked by many middle and upper class Canadians. Often times when people think of starvation, they picture children in Sub-Saharan Africa. The reality is that women and children in Canadian communities are affected by food insecurity daily. Action needs to be taken immediately in order for food insecurity to be fully eradicated, and justice to be achieved.

Food Insecurity In America Essay

People are without food worldwide. When we think of malnutrition and food insecurity we think about poverty stricken nations. The United States of America is not really discussed when it comes to food scarcity, but in reality this problem is prevalent in America and affects more than just homeless people. Some of the people that you least expect have to live without the adequate amount of food for survival. Scarcity of food is ignored by even the government and is embarrassing to those who have to live this struggle. The documentary A Place at the Table presents the food struggle in the U.S. with families who are suffering from a lack of food. This deficiency can cause serious health complications and can affect all aspects of life.

Food Insecurity Affects More Than 48 Million Americans Every Year ( Mcmillan ) Essay

Food insecurity affects more than 48 million Americans every year (McMillan). Those who reside in food insecure homes can generally not afford healthy foods, therefore increasing the incidence of obesity and other resultant chronic disorders. According to The American Journal of Public Health, “Food insecurity has been shown to diminish dietary quality and affect nutritional intake and has been associated with chronic morbidity (e.g., type 2 diabetes, hypertension) and weight gain” (Nguyen, Shuval, Bertmann, & Yaroch, 2015, p. 1453). Those who live without adequate access to nutritional food, such as fresh fruits and vegetables, have higher rates of obesity not because of the amount of food they eat, but the poor nutritional value of affordable meals.

How Does Hugo Chavez Deal With Food Insecurity In Venezuela

According to Derek Byerlee, food security can be defined as “the challenge of meeting food and nutritional needs while protecting environmental services.” Based on the definition given by Byerlee, food insecurity will be the exact opposite. Not meeting the food and nutritional needs of a country. Keep this definition in mind as this word will be mentioned throughout the paper.

Essay on We Can End World Hunger

- 8 Works Cited

Food security is one of the largest problems facing our world today. To be "food secure" a country must have enough

Factors of Food Insecurity

Food Insecurity is defined as access by all people at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life, and at a minimum includes the following: the ready availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods and the assured ability to acquire personally acceptable foods in a socially acceptable way, qualified by their involuntariness and periodicity. Even though food insecurity affects everyone in the household, it may also affect them differently. Food insecurity mostly exists whenever food security is limited. Uncertain or limited availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods results chronic diseases psychological, and suicidal syndrome (Cook & Frank, 2008)

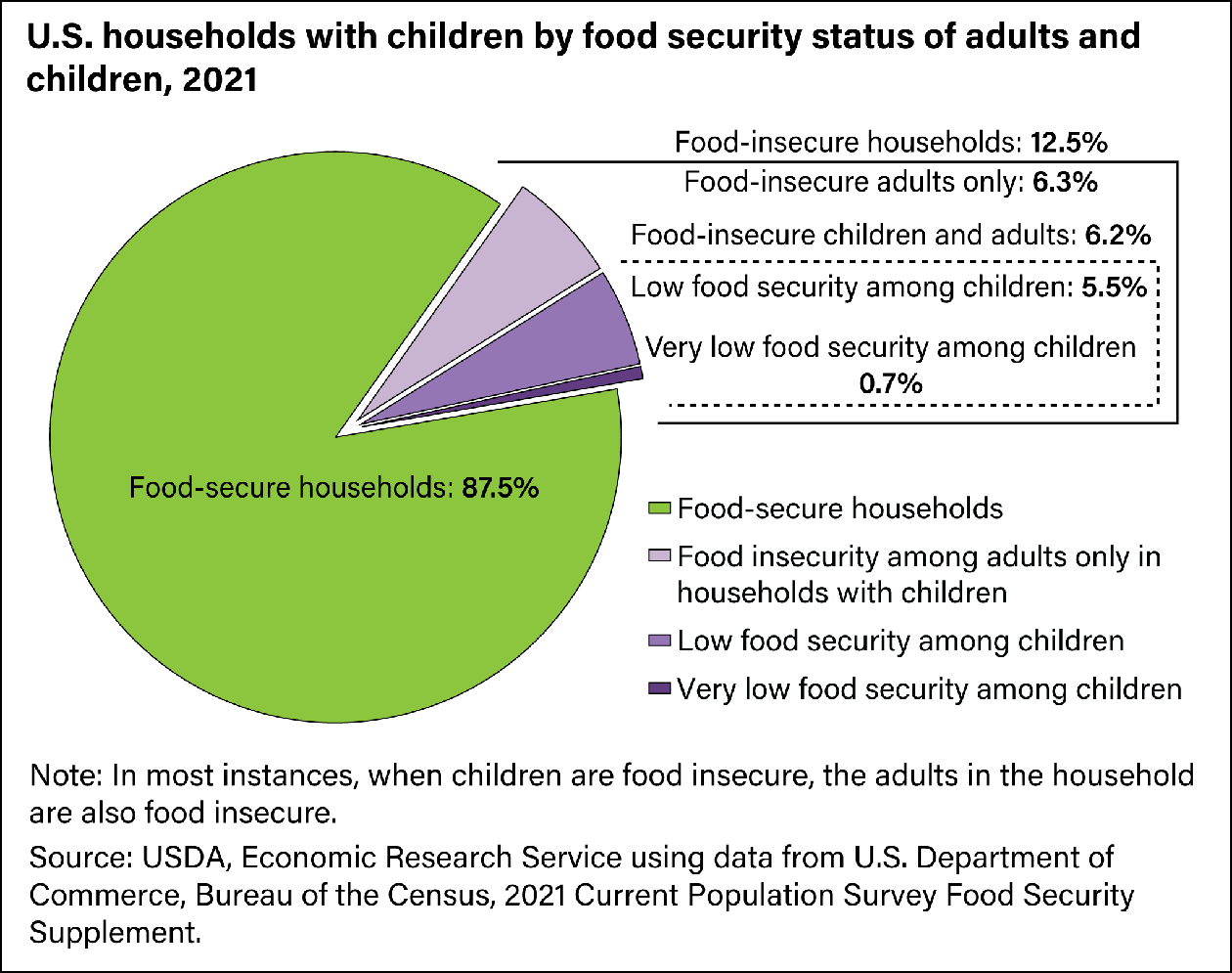

One of most common problems in the world is food insecurity. It is not only happening in the third world countries, but it is also happening in the richest country in world, the USA. Food insecurity occurs when a family does not have enough food for all family members. The USDA confirms that 12.7 percent of U.S households are suffering from food insecurity. Food insecurity can be of two kinds: low food insecurity and very low food insecurity. In low insecurity households, family members just eat enough calories for their body, but their food is not nutritious. Low food insecurity makes up 7.4 percent of 12.7 of food insecurity households in the U.S, (USDA). The other type is very low food insecurity. The family members do not have enough food at specific times in the year because they lack money. This type makes up 4.9 percent out of 12.7 percent in the food insecurity, (USDA). Food insecurity most often happens in the households with children, especially households with children headed by a single man or a single woman. The USDA estimates that households with children headed by single woman have 31.6 percent chance of experiencing low food insecurity, and households with children headed by a single man have 21.7 percent chance for low food insecurity. The South has highest rate of food insecurity with 13.5 percent. The rate of food insecurity in the Northeast (10.8 percent) is lower than Midwest (12.2 percent). The rate of food insecurity according to states in the three

Related Topics

- Food security

Food Insecurity - Essay Examples And Topic Ideas For Free

Food Insecurity refers to the lack of reliable access to sufficient quantities of affordable, nutritious food. Essays could delve into the causes, effects, and possible solutions to food insecurity both in the United States and globally, addressing issues like poverty, agricultural practices, and climate change. A substantial compilation of free essay instances related to Food Insecurity you can find at PapersOwl Website. You can use our samples for inspiration to write your own essay, research paper, or just to explore a new topic for yourself.

Child Food Insecurity

It is wrong to think that child food insecurity, malnourishment, and other food issues are only present in "third-world" countries because in reality, they occur worldwide ("Woodhouse"). They are especially prevalent in the United States ("Morrissey"), which is considered to be one of the most advanced and affluent countries in the world. Children from low-income families feel the greatest effects of food insecurity in the United States because they have minimal access to fresh foods, which is caused by the […]

Food Insecurity on College Campuses: Prevalence, Consequences and Solutions

Food insecurity in the United Sates has become a topic of high concern due to the rapid rate at which it has increased in recent years. Food insecurity is defined as "the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways" (Holben & Marshall 2017). Food insecurity is an issue that must be addressed, as the consequences are devastating for those that are affected. Until recently, […]

Escherichia Coli – an Overview

Escherichia coli is coliform bacterium of the genus Escherichia and is a Gram negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped bacteria. E. coli lives a life of luxury in the lower intestines of warm blooded animals, including humans but when forced out, it lives a life of deprivation and hazard in water, sediment and soil. Most E. coli strain are harmless and are an important part of a healthy human intestinal tract. However, some E. coli are pathogenic cause either diarrhea or illness […]

We will write an essay sample crafted to your needs.

The Effects of Food Insecurity in the Community

Abstract Food insecurity is not having the ability to acquire nutritious foods essential for a healthy diet and life (Feeding America, 2011). This problem is a common issue in the Monterey County Salinas Valley, especially among the Latinos, African Americans, single mothers, senior citizens, and children who live in low-income households (Kresge, 2011). Factors that indicate food insecurity are location, unemployment, availability of nutritious foods, and conditions of markets. Effects of food insecurity are health problems, emotional stress, behavior issues, […]

Food Insecurity Among Asian Americans

This study evaluated the prevalence and burden of food insecurity among disaggregated Asian American populations. In this research, prevalence of food insecurity among Asian American subgroups was assessed, with the primary exposure variable of interest being acculturation. This assessment utilized the California Health Interview Survey, the largest state health survey. The results demonstrated that the highest prevalence of food insecurity was found among Vietnamese (16.42%), while the lowest prevalence was among Japanese (2.28%). A significant relationship was noted between the […]

Poor Nutrition and its Effects on Learning

Nutrition is essential to human welfare, however, numerous number of people are badly affected by poor nutrition especially children. Malnutrition is a major concern which ranges from undernutrition to problems of overweight and obesity. It’s usually caused by deficiency in essential vitamins and nutrients needed for intellectual development and learning. The most critical stage for brain development is mainly from conception to the first 2 years of life. It’s highly important that pregnant mothers are given the necessary vitamins and […]

What is Food Insecurity in America?

Throughout the United States, access to healthy food is a privilege. Cumulative institutionalized racism is deeply embedded in the foundation of the country, throughout historical and present public policies, ultimately manifesting injustice within many entities throughout the nation, specifically the food industry (American Civil Liberties Union). This oppressive industry, which includes fast food corporations and agricultural components, takes advantage of vulnerable minority and low-income populations. They do this in many ways, some of which include manipulating the market, pushing out […]

Food Insecurity at Berkeley

During their time in college, many UC Berkeley undergraduate and graduate students experience some type of basic need insecurity. Contrary to basic needs security, basic needs insecurity refers to the inability to obtain food, housing, and financial stability. Students who face food insecurity undergo the struggles of skipping meals or consuming unhealthy food due to their financial inability to afford healthier or complete meals. According to the “2016 UC Food Access & Security Study”, 48% of undergraduate students across the […]

Hunger in ?olleges

Introduction: The Problem Hunger in colleges is a serious issue that has been existing for years as student's lack access to reliable and affordable food. Food insecurity is "a household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food (USDA)." Students in colleges, not only hunger for knowledge but also for food. The food insecurity issue has the potential of undermining academic success. Most students do not get enough to eat and are hence fatigued and worried. […]

Food Insecurity in African American Elders

Food insecurity occurs when the availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or the ability to acquire them in socially acceptable ways is limited or uncertain. It is a growing problem in older adults (Sengupta, 2016). Nine percent of older persons who live alone are food insecure, and about 15 percent are at risk. This issue is particularly concerning in African American older adults who are at a greater risk compared to their Hispanic and non-Hispanic white counterparts (16.66%, 13.26%, […]

College Food Insecurity: how Big is the Problem?

Working while attending college or university is also associated with food insecurity. 4,5,9 Higher rates of food insecurity have been reported among students working longer hours. 4,5 Rates of food insecurity for students working over 20 hours per week have ranged from 38-46%. 4,5 In addition, university students who live off campus and those who do not have a meal plan tend to have an increased risk for food insecurity as compared to students living on campus and those with […]

Food Insecurity in Mozambique: Going to Bed in Debt and Waking up Hungry

Abstract Food insecurity is a global problem that varies in magnitude on regional and local levels. It is also a problem that does not receive equal representation or efforts between and within nations. Some of the problems facing food insecurities, however, overlap between nations, for example, climate change, distribution of resources, and governmental roles and impacts. When compared to other nations of the world, which may or may not have dire food insecurities, Mozambique has its unique set of challenges, […]

Food Insecurity in the Bronx

The story of Jettie Young illustrates the widespread problem of food insecurity and how it affects individuals from any area or economic background across the United States. When Jettie Young was looking to purchase a house for her small family in Austin, Texas, affordability was foremost on her mind. She and her husband decided on a starter home in the Hornsby Bend area, a neighborhood made up of many families with young children, much like her own. What she did […]

Additional Example Essays

- The Extraordinary Science of Addictive Junk Food

- Junk Food Should be Taxed

- David Zinczenko: “Don't Blame the Eater”

- Fast Food vs Home Cooked

- Why Parents and Schools Shouldn't Ban Junk Food

- Homeschooling vs Public School

- Homeschooling vs Traditional Schooling

- Teaching is my dream job

- Dweck's Fixed and Growth Mindsets

- A Raisin in the Sun Theme

- Why Abortion Should be Illegal

- Death Penalty Should be Abolished

The gap between the poor and the rich across the globe is getting broader. As a result, a vast proportion of the world’s population suffers from malnutrition, or worse, is on the verge of hunger and starvation. The United States is no exception, and the number of undernourished is continuously increasing.

So how are developed and developing countries tackling the problem of poor nutrition and food security? Why has food become a means of getting rich instead of ensuring people’s well-being and safety? Is healthy food a privilege of the wealthy?

To draw attention to the issue, educational institutions often assign argumentative essays about food insecurity in America. College students should express their views on essay topics like food insecurity and scarcity, its causes and effects, GMOs, and sustainability. They can also work on new methods to ensure we produce enough food for everyone.

When writing your research paper, ensure your introduction contains an intriguing thesis statement for food insecurity. For instance, pose a question or challenge an approach in tackling the problem. Once you frame the hook, continue with the body paragraphs to present your views supported by evidence and credible sources. The final section of your manuscript is the conclusion which wraps up your ideas and offers an overview or solution to the issue.

As always, PapersOwl has the best essay examples on food insecurity solutions you can read for free. These ideas will help you outline the perfect cause-and-effect paper. If your work needs improvement, contact the expert team at PapersOwl, and they will be more than happy to assist you.

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Home — Essay Samples — Nursing & Health — Eating Habits — Food Insecurities

Food Insecurities

- Categories: Eating Habits

About this sample

Words: 864 |

Published: Mar 19, 2024

Words: 864 | Pages: 2 | 5 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, causes of food insecurity, consequences of food insecurity, solutions to food insecurity.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Nursing & Health

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

4 pages / 1607 words

4 pages / 1627 words

2 pages / 976 words

2 pages / 1118 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Eating Habits

Godbey, Geoffrey. 'The Role of Food in Social Relationships.' Nutrition Today, vol. 42, no. 6, 2007, pp. 244-247.Kolb, David A., and Roger L. Fry. 'Toward an Applied Theory of Experiential Learning.' Theories of Group Process, [...]

Mattson, M. P., Longo, V. D., & Harvie, M. (2016). Impact of intermittent fasting on health and disease processes. Ageing Research Reviews, 39, 46-58.Antoni, R., Johnston, K. L., Collins, A. L., & Robertson, M. D. (2018). [...]

Fung, Jason, and Jimmy Moore. 'The Complete Guide to Fasting.' Victory Belt Publishing, 2016.Fung, Jason. 'The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight Loss.' Greystone Books, 2016.Mattson, Mark P., Rafael de Cabo, and [...]

As a college student, it can be challenging to balance academics, social life, and self-care. Many students overlook the significance of self-care and healthy eating, which can lead to burnout and other health issues. In this [...]

To have a generally healthy body, you should try to maintain a healthy weight. If you’re overweight, you are not maintaining a generally healthy body. Calories are a unit of measurement. You eat calories from food and that [...]

In Radley Balko’s essay “What You Eat Is Your Business,” he argues that what we put into our bodies is our business, and it is our responsibility to make healthy choices. The widespread epidemic of obesity can only be solved if [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Food Insecurity in the US: The New Face of Hunger Essay

More than 35 million Americans suffered from hunger in 2019 and the ongoing pandemic of COVID-19 increased the number of people who face food insecurity up to 42 million (Feeding America, 2021). To put it more explicitly, every sixth person in the US has no food to eat at least once a year (McMillan, n.d.) These figures are shocking because the US is one of the wealthiest countries in the world. Furthermore, the problem is exacerbated by the fact that food insecurity is experienced not only by the homeless and unemployed but by working American citizens. The current essay discusses the causes of this social crisis and presents several steps that could be taken to tackle this urgent problem.

The modern phenomenon of hunger, or food insecurity, in the US, differs from one that existed in the times of the Great Depression. Ironically, an employed and even obese adult might lack food regularly. Even though this situation sounds illogical, it could be easily explained. The critical reason for food insecurity among citizens who work full-time is that the earnings are not high enough to cover all the bills and food purchases. The reason for obesity among people who struggle with the lack of food is that they could afford only cheap products, most of which are “filling but not nutritious and may actually contribute to obesity” (McMillan, n.d., para. 9). The problem is exacerbated if a person has a family and should feed not only himself or herself but also a spouse and children, as presented in the case of Christina Dreier.

Another side of the malnourishment problem is that fresh and healthy food prices are too high, and people with small wages could afford only cheap fast food full of fat and carbs and lacks fiber, vitamins, and minerals. What is more, poor people might work hard all day long and have no time to cook food at home; they have to eat fast food while walking simply because nearby there are no grocery stores where healthy food can be purchase even if they have money for it (McMillan, n.d.). Such places where people cannot buy food are called food deserts and contribute to food insecurity in the US.

The government does not ignore the situation and implements assistance programs to take care of people who have to choose between paying the bills and purchasing eating products. For example, McMillan (n.d.) presents the case of the Jefferson family that consists of 15 members and lives in a four-bedroom house with desktop computers and TVs in every room. The problem is that only three members of this family receive salaries. Still, this money is not enough to feed all the relatives. For this reason, every month, Jeffersons receive $125 in food stamps (McMillan, n.d.). This case differs from the one mentioned above because the primary problem is not the lack of food per se but the uncertainty of the ability to have the next meal. More precisely, this means that the family of Dreiers has little food to eat because it is too expensive for them. The second family, in its turn, is never sure that the existing supply of food will be enough to feed everyone during the month. That is because ten children are always hungry and sometimes exceed the daily limits of how much could be eaten.

Overall, the major problem is that even though the government indeed tries to solve the issue of hunger through the provision of food stamps, the quality and quantity of such food are depressing. The American government could undertake several steps to fix the problem. Firstly, the government should invest not only in the producers of corn and soy, which are the main components of fast food, but also in manufacturers that grow fruits and vegetables. This strategy will enable the producers of fruits and vegetables to lower their costs in the supermarket and, hence, make them affordable for people with low incomes.

The second strategy that could be recommended to the American administration deals with the problem of low monthly incomes. Currently, the federal minimum wage equals $7.25 per hour. The experience shows that it is too low to help people stay fed with nourishing and healthy products on a daily basis. Consequently, politicians should think about how to raise the minimum wage at least twice. This could be done, for example, through subsidizing companies where the salaries of employees do not exceed the minimal size proclaimed by the federal government.

To conclude, the issue of food insecurity in the US is extremely complex because it is faced not only by the people who live in poverty but also by the representatives of the middle class. This problem is caused by low wages, high prices for fresh food, and the absence of grocery stores in some areas. Even though the government provides food stamps for those who need them, more should be done to eradicate hunger. The US administration should invest more in agriculture and increase the minimum wage.

Feeding America (2021). Hunger in America . Web.

McMillan, T. (n.d.). The new face of hunger. National Geographic Magazine . Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, July 30). Food Insecurity in the US: The New Face of Hunger. https://ivypanda.com/essays/food-insecurity-in-the-us-the-new-face-of-hunger/

"Food Insecurity in the US: The New Face of Hunger." IvyPanda , 30 July 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/food-insecurity-in-the-us-the-new-face-of-hunger/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Food Insecurity in the US: The New Face of Hunger'. 30 July.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Food Insecurity in the US: The New Face of Hunger." July 30, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/food-insecurity-in-the-us-the-new-face-of-hunger/.

1. IvyPanda . "Food Insecurity in the US: The New Face of Hunger." July 30, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/food-insecurity-in-the-us-the-new-face-of-hunger/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Food Insecurity in the US: The New Face of Hunger." July 30, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/food-insecurity-in-the-us-the-new-face-of-hunger/.

- Inadequate Food Choices for Americans in Low-Income Neighborhoods

- Hunger Crisis and Food Security: Research

- “Instead of Coronavirus, the Hunger Will Kill Us”: Article Analysis

- Why Is Africa Poor? Shaxson’s and Collier’s Viewpoints

- How Political Parties Affect Low-Income Areas

- America’s Shame: How Can Education Eradicate Poverty

- Income Inequality Measurements Within Country

- Global Poverty and Ways to Overcome It

What You Need to Know About Food Security and Climate Change

#ShowYourStripes graphic by Professor Ed Hawkins (University of Reading) https://showyourstripes.info/

What is the state of global food security today, and what is the role of climate change?

The number of people suffering acute food insecurity increased from 135 million in 2019 to 345 million in 82 countries by June 2022, as the war in Ukraine, supply chain disruptions, and the continued economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic pushed food prices to all-time highs.

Global food insecurity had already been rising, due in large part to climate phenomena. Global warming is influencing weather patterns, causing heat waves, heavy rainfall, and droughts. Rising food commodity prices in 2021 were a major factor in pushing approximately 30 million additional people in low-income countries toward food insecurity.

At the same time, the way that food is often produced today is a big part of the problem. It’s recently been estimated that the global food system is responsible for about a third of greenhouse gas emissions—second only to the energy sector; it is the number one source of methane and biodiversity loss.

It’s recently been estimated that the global food system is responsible for about a third of greenhouse gas emissions—second only to the energy sector; it is the number one source of methane and biodiversity loss.

Who is most affected by climate impacts on food security?

About 80% of the global population most at risk from crop failures and hunger from climate change are in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia, where farming families are disproportionally poor and vulnerable. A severe drought caused by an El Nino weather pattern or climate change can push millions more people into poverty. This is true even in places like the Philippines and Vietnam, which have relatively high incomes, but where farmers often live at the edge of poverty and food price increases have an outsized impact on poor urban consumers.

How might climate change affect farming and food security in the future?

Up to a certain point, rising temperatures and CO2 can be beneficial for crops. But rising temperatures also accelerate evapotranspiration from plants and soils, and there must also be enough water for crops to thrive.

For areas of the world that are already water-constrained, climate change will increasingly cause adverse impacts on agricultural production through diminishing water supplies, increases in extreme events like floods and severe storms, heat stress, and increased prevalence of pests and diseases.

Above a certain point of warming -- and particularly above an increase of 2 degrees Celsius in average global temperatures – it becomes increasingly more difficult to adapt and increasingly more expensive. In countries where temperatures are already extremely high, such as the Sahel belt of Africa or South Asia, rising temperatures could have a more immediate effect on crops such as wheat that are less heat tolerant.

Without solutions, falling crop yields, especially in the world's most food-insecure regions, will push more people into poverty – an estimated 43 million people in Africa alone could fall below the poverty line by 2030 as a result.

How can agriculture adapt to climate change?

It’s possible to reduce emissions and become more resilient, but doing so often requires major social, economic, and technological change. There are a few key strategies:

Use water more efficiently and effectively, combined with policies to manage demand . Building more irrigation infrastructure may not be a solution if future water supply proves to be inadequate to supply the irrigation systems—which our research has shown may indeed be the case for some countries. Other options include better management of water demand as well as the use of advanced water accounting systems and technologies to assess the amount of water available, including soil moisture sensors and satellite evapotranspiration measurements . Such measures can facilitate techniques such as alternate wetting and drying of rice paddies, which saves water and reduces methane emissions at the same time.

Switch to less-thirsty crops . For example, rice farmers could switch to crops that require less water such as maize or legumes. Doing so would also help reduce methane emissions, because rice is a major source of agri-food emissions. But a culture that has been growing and consuming rice for thousands of years may not so easily switch to another less thirsty, less emitting crop.

Improve soil health . This is hugely important. Increasing organic carbon in soil helps it better retain water and allows plants to access water more readily, increasing resilience to drought. It also provides more nutrients without requiring as much chemical fertilizer -- which is a major source of emissions. Farmers can restore carbon that has been lost by not tilling soil and by using cover crops, particularly with large roots, in the rotation cycle rather than leaving fields fallow. Such nature-based solutions to environmental challenges could deliver 37% of climate change mitigation necessary to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement. But getting farmers to adopt these practices will take time, awareness-raising and training. In places where farm plots are small and farmers can’t afford to let fields lie fallow or even rotate with leguminous crops, improving soil health could pose a challenge.

What is the World Bank doing to help countries build food security in the face of climate change?

The World Bank Group’s Climate Change Action Plan (2021-2025) is stepping up support for climate-smart agriculture across the agriculture and food value chains and via policy and technological interventions to enhance productivity, improve resilience, and reduce GHG emissions. The Bank also helps countries tackle food loss and waste and manage flood and drought risks. For example, in Niger, a Bank-supported project aims to benefit 500,000 farmers and pastoralists in 44 communes through the distribution of improved, drought-tolerant seeds, more efficient irrigation, and expanded use of forestry for farming and conservation agriculture techniques. To date, the project has helped 336,518 farmers more sustainably manage their land and brought 79,938 hectares under more sustainable farming practices.

Website: Climate Explainer Series

Website: Climate Stories: How Countries and Communities Are Shaping A Sustainable Future

Website: Food Security Update

Website: World Bank - Climate Change

Website: World Bank - Agriculture and Food

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

America at Hunger’s Edge

Photographs by Brenda Ann Kenneally Sept. 2, 2020

- Share full article

A shadow of hunger looms over the United States. In the pandemic economy, nearly one in eight households doesn’t have enough to eat. The lockdown, with its epic lines at food banks, has revealed what was hidden in plain sight: that the struggle to make food last long enough, and to get food that’s healthful — what experts call ‘food insecurity’ — is a persistent one for millions of Americans.

Beginning in May, Brenda Ann Kenneally set out across the country, from New York to California , to capture the routines of Americans who struggle to feed their families, piecing together various forms of food assistance, community support and ingenuity to make it from one month to the next.

Food insecurity is as much about the threat of deprivation as it is about deprivation itself: A food-insecure life means a life lived in fear of hunger, and the psychological toll that takes. Like many hardships, this burden falls disproportionately on Black and Hispanic families, who are almost twice as likely to experience food insecurity as white families.

Like so many who live at hunger’s edge, the members of the extended Stocklas family — whom Kenneally has photographed for years — gain and lose food stamps depending on fluctuating employment status in an unstable economy. They often have trouble stretching their funds to the end of the month, so they pool resources to provide family-style dinners for all.

Just days before Kenneally arrived, the governor closed schools statewide, creating a new source of stress for food-insecure families, which often rely on free school lunches to keep their school-age children fed. This made the family’s big collective meals all the more crucial. “Even if it’s just pitching in $10 when we don’t have food stamps,” Kandice Zakrzewski says, “we all pitch in.”

Late last year, Doris Hall, 63, moved back to Gary, her hometown, to look after her great-grandchildren — “so they don’t have to be in daycare,” she says. On weekends, she takes in as many as nine of the children — occasionally all 14 — so that their parents can work.

For lunch, it’s “microwaveable stuff,” like corndogs, hot dogs and chicken nuggets that Hall picks up at the nearby food bank. Dinners vary: spaghetti, chicken, soups, tacos. When she has a rare moment to eat alone, she makes her favorite meal for herself: greens and tacos.

In the face of deprivation, food-insecure families often seize any opportunity to get and store food when it’s available.

Kenneally arrived in Illinois in early June, soon after nationwide unemployment claims filed during the pandemic had topped 40 million.

In Cicero, just west of Chicago, Jennifer Villa, 29, was living in an apartment with a kitchen that needed plumbing repairs. She and her family were already struggling — a disability makes it hard for her to work — and the pandemic had meant less fresh food and even longer pantry lines.

Whenever food deliveries came, Villa’s kids would celebrate. “Oh, Mommy, we’re going to have food tonight,” they would tell her. “We’re not going to go to sleep with no food in our tummy.”

By June, the social upheavals following the killing of George Floyd created even more instability for some families. Kenneally visited Manausha Russ, 28, a few days after protests led to the closure of a nearby Family Dollar, where Russ used to get basics like milk, cereal and diapers. “The stores by my house were all looted,” she says.

Russ lives with her four daughters on the west side of St. Louis. She receives about $635 per month in food stamps, but with the girls at home all day, and her partner, Lamarr, there too, it isn’t always sufficient. “Some days I feel like I have a lot,” she says, “and some days I feel like I don’t have enough.”

In so many places, Kenneally found food-insecure families were helping one another out despite their own hardship. Here, in a condominium complex on the city’s east side, a neighbor picked up free school lunches and distributed them to children in the building, including the Boughton sisters: Brooklyn, 4, on the far right, Chynna, 9, and Katie, 8, seen here with a neighbor’s toddler who has since moved away.

Most of the families Kenneally photographed had struggled to feed themselves adequately for years. But she also met families who had been thrown into food insecurity by the pandemic.

Facing Hunger For The First Time

The federal government’s food-stamp program has been dramatically expanded to confront the economic devastation of the pandemic. But even that hasn’t been enough, as the ranks of the needy grow.

In long conversations around the country this August — at kitchen tables, in living rooms and sitting in cars in slow-moving food lines with rambunctious children in the back — Americans reflected on their new reality. The shame and embarrassment. The loss of choice in something as basic as what to eat. The worry over how to make sure their children get a healthy diet. The fear that their lives will never get back on track.

“Folks who had really good jobs and were able to pay their bills and never knew how to find us,” says Ephie Johnson, the president and chief executive of Neighborhood Christian Charities. “A lot of people had finally landed that job, were helping their family, and able to do a little better. And then this takes you out.”

By late June, Kenneally had reached Mississippi , where the economic toll of Covid-19 was falling hard on some of America’s most chronically impoverished areas, where residents have lived under hunger’s shadow for years. The pandemic dropped the state’s labor participation rate to just 53 percent, the lowest in the nation.

Even before the pandemic, more than half of Mississippi’s seniors — 56 percent — experienced regular shortfalls in food. One in 4 Mississippians is now experiencing food insecurity, according to the nonprofit Feeding America.

The city of Jackson (population 164,000) is often classified as a “food desert” for its high rate of food insecurity and the scarcity of well-stocked stores. Deidre Lyons lives there with her three kids, sister, niece and father. Lyons, 28, receives $524 a month in food stamps, but without access to a car, she can’t easily get to a grocery store to use them.

“My kids, they love to eat,” says Lyons, whose cousin will occasionally drive her to the grocery store when she isn’t caring for her own children. “My kids eat whatever we cook because they aren’t picky eaters. I’m hoping they stay like that.”

The causes of chronic food insecurity are many: unemployment; low wages; unaffordable or unstable housing; rising medical costs; unreliable transportation.

How Hunger Persists In America

Treating hunger as a temporary emergency, instead of a symptom of systemic problems, has always informed the American response to it — and as a result government programs have been designed to alleviate each peak, rather than address the factors that produce them.

Food banks are supposed to fill in the gaps, but more than 37 million Americans are food insecure, according to the U.S.D.A. “We call it an emergency food system, but it’s a 50-year emergency,” says Noreen Springstead, executive director of WhyHunger, which supports grass-roots food organizations.

In early July, the pandemic was cresting in Texas just as Kenneally arrived.

Kelly Rivera, a single mother with three kids who makes $688 every two weeks as a teacher’s aide, goes to the food bank on Wednesdays to supplement what she is able to buy with food stamps. “There are times they give you what you need, and there are times they don’t give you what you need,” she says. “You can’t be picky.”

The family had to wait for hours at the Catholic Charities in 100-degree heat. But Rivera has a message for her struggling neighbors who are too proud to visit food banks: “Don’t be ashamed. That is what the community is there for, to help.”

Some 800 miles west in New Mexico, near the town of Hatch, workers pick onions for $15 a box, which translates to less than a minimum wage for many workers. There are no food pantries nearby, and so the workers are forced to eat extremely simply on their earnings, making nearly everything they eat from scratch.

Juan Pablo Reyes is using the money he made picking onions to help pay for college. “People that work at the bottom of the food chain, cultivating all these different crops, are basically the builders of our country,” he says.

Leaving New Mexico, Kenneally headed west across Arizona. She finished her journey in Southern California at the end of July. The story there was no different than it had been across the country, except that wildfires were also beginning to ravage the state — yet another crisis in a year full of them.

An event planner and hairstylist who has been out of work since early in the pandemic, Alexis Frost Cazimero, 40, now spends her days driving around the county with three of her children — Mason, 6 (not pictured); Carson, 5; and Coco, 1 — collecting food for her family and for neighbors and friends who are unable to leave their homes or reluctant to seek help.

Cazimero says she is grateful she has been able to help others. “Being that person in the community that shares and brings resources to the people that can’t get them brings purpose to my family.”

Kenneally’s photographs reveal the fragility of American life, exposed and exacerbated by the pandemic. They show us how close to the edge so many families live, how vulnerable and insecure their arrangements are, and also how resilient they can be when faced with a crisis.

But nothing stands out from these images more vividly than the children: eating whatever they can, whenever and wherever they can, somehow managing to maintain, in the midst of this historically desperate time, some innocence and some hope.

They are the greatest victims of the food-insecurity crisis. Research has shown long-term links between food insecurity and a wide variety of health issues in children — elevated risks of asthma and other chronic illnesses, lags in educational attainment. And according to a Brookings Institution researcher, the number of U.S. children in need of immediate food assistance is approximately 14 million.

For most of these children, the pandemic did not cause the instability that plagues their lives; when it is over, they will face a crisis no less acute, one that has persisted in this country for generations.

In the richest nation on earth, they live at the edge of hunger.

Kenneally visited many food distribution sites along her journey, including ones run by: the Salvation Army , Catholic Charities , Second Harvest Food Bank of Northwest Pennsylvania , Parma City School District , St . Louis Area Foodbank , Operation Food Search , Neighborhood Christian Centers , Y.M.C.A . of Memphis and t he Mid-South , Stewpot Community Services , Houston Food Bank , Houston Independent School District , Community Food Bank of Southern Arizona and Tucson Interfaith HIV/AIDS Network .

Brenda Ann Kenneally is a multimedia journalist who, over 30 years, has produced participatory media projects with families from her home community, including “Upstate Girls: Unraveling Collar City.” She is currently assembling a multimedia autobiography, charting her experience from being a disenfranchised youth to becoming a Guggenheim fellow and frequent contributor to the magazine. Read more about Kenneally’s journey.

Adrian Nicole LeBlanc , an independent journalist and MacArthur fellow, was embedded in an assisted-living facility as Kenneally began her trip for this issue. They have worked together since 2003.

Tim Arango is a Los Angeles-based national correspondent for The Times. He spent seven years as Baghdad bureau chief and also covered Turkey. Before heading overseas, he had been a media reporter for The Times since 2007.

Additional Reporting by Maddy Crowell , Lovia Gyarkye , Concepción de León , Jaime Lowe , Jake Nevins , Kevin Pang and Malia Wollan .

Photo Editors: Amy Kellner and Rory Walsh .

Design by Aliza Aufrichtig and Eden Weingart .

Explore The New York Times Magazine

Charlamagne Tha God on ‘The Interview’ : The radio host talked to Lulu Garcia-Navarro about how he plans to wield his considerable political influence .

Was the 401(k) a Mistake? : Here’s how an obscure, 45-year-old tax change transformed retirement and left so many Americans out in the cold.

A Third Act for the Ages : Like her character on “Hacks,” Jean Smart is winning late-career success on her own exuberant terms.

The C.E.O.s Who Won’t Quit : What happens to a company — and the economy — when the boss refuses to retire ?

Retiring in Their 30s : Meet the schemers and savers obsessed with ending their careers as early as possible.

Advertisement

- Mission and Vision

- Scientific Advancement Plan

- Science Visioning

- Research Framework

- Minority Health and Health Disparities Definitions

- Organizational Structure

- Staff Directory

- About the Director

- Director’s Messages

- News Mentions

- Presentations

- Selected Publications

- Director's Laboratory

- Congressional Justification

- Congressional Testimony

- Legislative History

- NIH Minority Health and Health Disparities Strategic Plan 2021-2025

- Minority Health and Health Disparities: Definitions and Parameters

- NIH and HHS Commitment

- Foundation for Planning

- Structure of This Plan

- Strategic Plan Categories

- Summary of Categories and Goals

- Scientific Goals, Research Strategies, and Priority Areas

- Research-Sustaining Activities: Goals, Strategies, and Priority Areas

- Outreach, Collaboration, and Dissemination: Goals and Strategies

- Leap Forward Research Challenge

- Future Plans

- Research Interest Areas

- Research Centers

- Research Endowment

- Community Based Participatory Research Program (CBPR)

- SBIR/STTR: Small Business Innovation/Tech Transfer

- Solicited and Investigator-Initiated Research Project Grants

- Scientific Conferences

- Training and Career Development

- Loan Repayment Program (LRP)

- Data Management and Sharing

- Social and Behavioral Sciences

- Population and Community Health Sciences

- Epidemiology and Genetics

- Medical Research Scholars Program (MRSP)

- Coleman Research Innovation Award

- Health Disparities Interest Group

- Art Challenge

- Breathe Better Network

- Healthy Hearts Network

- DEBUT Challenge

- Healthy Mind Initiative

- Mental Health Essay Contest

- Science Day for Students at NIH

- Fuel Up to Play 60 en Español

- Brother, You're on My Mind

- Celebrating National Minority Health Month

- Reaching People in Multiple Languages

- Funding Strategy

- Active Funding Opportunities

- Expired Funding Opportunities

- Technical Assistance Webinars

- Community Health and Population Sciences

- Clinical and Health Services Research

- Integrative Biological and Behavioral Sciences

- Intramural Research Program

- Training and Diverse Workforce Development

- Inside NIMHD

- ScHARe HDPulse PhenX SDOH Toolkit Understanding Health Disparities For Research Applicants For Research Grantees Research and Training Programs Reports and Data Resources Health Information for the Public Science Education

- Understanding Health Disparities Series

Food Accessibility, Insecurity and Health Outcomes

- PhenX SDOH Toolkit

- Understanding Health Disparities

- For Research Applicants

- For Research Grantees

- Research and Training Programs

- Reports and Data Resources

- Health Information for the Public

- Science Education

Go to food and nutrition insecurity scientific resources

Go to food accessibility and insecurity as an SDOH

Go to NIMHD food accessibility/insecurity resources

Having access to nutritious food is a basic human need.

- Food security means having access to enough food for an active, healthy life.

- Nutrition security means consistent access, availability, and affordability of foods and beverages that promote well-being, prevent disease, and, if needed, treat disease.

On the other hand, food and nutrition insecurity is an individual-, household-, and neighborhood-level economic and social condition describing limited or uncertain access to adequate and affordable nutritious foods and is a major public health concern.

Food insecurity and the lack of access to affordable nutritious food are associated with increased risk for multiple chronic health conditions such as diabetes , obesity, heart disease, mental health disorders and other chronic diseases . In 2020, almost 15% of U.S. households were considered food insecure at some point in time, meaning not all household members were able to access enough food to support active, healthy lifestyles. In nearly half of these households, children were also food insecure ( see chart above ), which has implications for human development and school experience . Food insecurity disproportionately affects persons from racial and ethnic minority and socioeconomically disadvantaged populations:

- 20% of Black/African American households were food insecure at some point in 2021 , as were 16% of Hispanic/Latino households when compared to 7% of White households.

- Food insecurity for U.S. Hispanic/Latino adults differs by origin. Current national data is not available but from 2011-2014 food insecurity was highest among those identifying from Puerto Rico (25.3%), followed by Mexico (20.8%) Central and South America (20.7%) and Cuba (12.1%).

- In the past 20 years, American Indian/Alaskan Native (AI/AN) households have also been at least twice as likely to have experienced food insecurity when compared with White households, often exceeding rates of 25% across different regions and AI/AN communities.

- Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (NHPI) adults also experience a high food insecurity prevalence (20.5%) and had significantly higher odds of experiencing low and very low food security compared with White households.

- While national data on specific Asian American national origin populations is not readily available, among Asian Americans living in California from 2001-2012 , food insecurity was highest among Vietnamese households (16.4%), followed by Filipino (8.3%), Chinese (7.6%), Korean (6.7%), South Asian (3.14%), and Japanese households (2.3%), highlighting considerable variation across Asian American communities.

- Food insecurity is inextricably linked to poverty , with 35.3 % of households with incomes below the federal poverty line being food insecure.

- Although the graph below on national trends in food insecurity does not capture the full impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, food insecurity is likely to increase, and racial and ethnic disparities in food insecurity experiences could worsen.

Healthy food accessibility and insecurity is a social determinant of health.

Food and nutrition insecurity are predominantly influenced by the local environment, including surrounding neighborhood infrastructure, accessibility, and affordability barriers. Access to grocery stores that carry healthy food options (such as fresh fruit, vegetables, low-fat fish and poultry) are not located equitably across residential and regional areas in the United States.

Areas that lack access to affordable, healthy foods are known as food deserts . Food deserts are:

- Found in urban or suburban neighborhoods that lack grocery stores (supermarkets or small grocery stores) that offer healthy food options.

- Found in rural areas and neighborhoods where the nearest grocery stores are too far away to be convenient or accessible.

- More prevalent in neighborhoods that are comprised of a majority of racial or ethnic minority residents or in rural AI/AN communities.

- More likely found in areas with a higher percentage of residents experiencing poverty , regardless of urban or rural designation.

Urban, suburban, and rural areas can also be overwhelmed with stores that sell unhealthy calorie-dense and inexpensive junk foods, including soda, snacks, and other high sugar foods. This is known as a food swamp . Food swamps:

- Reduce access to nutritional foods and provide easier access to unhealthy foods .

- Are a predictor of obesity , particularly in communities where residents have limited access to their own or public transportation and experience the greatest income inequality.

Reducing food and nutrition insecurity in the U.S. will require a multifaceted approach that considers, among other possibilities:

- Strategies that engage communities in local health programs; for example, recruiting community partners to assist in addressing gaps between food access and intake .

- Interventions that utilize federal food and nutritional supplemental programs, including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program ( SNAP ) and the Special Supplemental Nutritional Program for Women, Infants, and Children ( WIC ).

- Leveraging local and federal policies targeting food insecurity; for example, retail store interventions , where healthy food placement, promotion and price influence healthier choices; sweetened beverage taxes to reduce the purchase appeal to consumers; and junk food taxes balanced with removal of taxes on water and fruits and vegetables.

NIMHD is studying and addressing issues related to food and nutrition insecurity through a variety of initiatives:

NIH Publication

Research Opportunities to Address Nutrition Insecurity and Disparities Coauthored by Shannon N. Zenk, Lawrence A. Tabak and Eliseo J. Pérez-Stable, JAMA 2022

NIMHD Events on Food Insecurity

Food Insecurity, Neighborhood Food Environment, and Nutrition Health Disparities: State of the Science NIMHD co-sponsored this September 2021 workshop led by the NIH Office of Nutrition Research and its Nutrition and Health Disparities Implementation Working Group

NIMHD Hosts Senior Research Investigators to Present on Food Insecurity and Related Topics:

NIMHD co-sponsored the November 2020 virtual workshop NIH Rural Health Seminar: Challenges in the Era of COVID-19 . This workshop focused on long-standing health disparities and social inequities experienced by rural populations, and featured experts on food insecurity, including:

- Dr. Brenda Eskenazi , Professor in Maternal and Child Health and Epidemiology, Brian and Jennifer Maxwell Endowed Chair in Public Health and Director of the Center for Environmental Research and Children’s Health, University of California, Berkeley, who spoke on the topic of COVID-19 and the impact on health of Californian farmworkers .

- Dr. Alice Ammerman , Mildred Kaufman Distinguished Professor of Nutrition, Director, Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, University of North Carolina, who spoke on interventions to address job loss and food security in rural communities during COVID .

NIMHD Content on Food Insecurity

Nimhd science visioning and research strategies.

As part of the Scientific Visioning Research Process , NIMHD developed a set of 30 strategies to transform minority health and health disparities research . Several of these strategies focus on issues related to food security and accessibility, including:

- Assessing how environment and neighborhood structures such as areas where people have limited access to a variety of healthy and affordable foods (or food deserts) influence health behaviors.

- Promoting multi-sectoral interventions that address the structural drivers of food deserts.

- Promoting interventions that address the social determinants of health within health care systems, including food insecurity.

Publications

Food Insecurity and Obesity: Research Gaps, Opportunities, and Challenges Dr. Derrick Tabor, NIMHD Program Officer, co-authored “Food insecurity and obesity: research gaps, opportunities” in Translational Behavioral Medicine . This review highlights NIH funding for grants related to food insecurity and obesity, identifies research gaps, and presents upcoming research opportunities to better understand the health impact of food insecurity.

NIMHD Research Framework

Native Hawaiian Health Adaptation The NIMHD Research Framework was adapted by Keawe’aimoku Kaholokula, Ph.D., University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, to reflect social and cultural influences of Native Hawaiian health . Ka Mālama Nohona (nurturing environments) to support Native Hawaiian health include strategic goals of food sovereignty and security to promote a strong foundation for healthy living.

NIMHD Articles

NIMHD Research Features

- The Navajo Nation Junk Food Tax and the Path to Food Sovereignty

- Fighting Cancer—and Reducing Disparities—Through Food Policy

- Fresh Food for the Osage Nation: Researchers and a Native Community Work Toward Improved Food Resources and Food Sovereignty

NIMHD Insights Blog

- Amplifying the Voice of Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Communities Amid the COVID-19 Crisis by Joseph Keawe‘aimoku Kaholokula, Ph.D.

- Racism and the Health of Every American by NIMHD Director Eliseo J. Pérez-Stable, M.D.

- The Future of Minority Health and Health Disparities Research by Tany Agurs-Collins, Ph.D., R.D., and Susan Persky, Ph.D.

- Addressing Social Needs and Structural Inequities to Reduce Health Disparities: A Call to Action for Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month by Marshall H. Chin, M.D., M.P.H.

- “Insights” on Simulation Modeling and Systems Science, New Research Funding Opportunity by Xinzhi Zhang, M.D., Ph.D.

NIMHD Funding Resources and Opportunities

Funding opportunity announcements (foas).

NIMHD supports many FOAs that include topics related to food security as an area of research interest:

- Request for Information: Food Is Medicine Research Opportunities

- Notice of Special Interest: Stimulating Research to Understand and Address Hunger, Food and Nutrition Insecurity

- Community Level Interventions to Improve Minority Health and Reduce Health Disparities (R01 Clinical Trial Optional)

- Addressing Health Disparities Among Immigrant Populations through Effective Interventions (R01 Clinical Trial Optional)

- Health Services Research on Minority Health and Health Disparities (R01 Clinical Trial Optional)

- Long-Term Effects of Disasters on Health Care Systems Serving population experiencing health disparities (R01 Clinical Trial Optional)

- Please see our list of Active NIMHD Funding Opportunities for more.

NIMHD-Supported Research Projects

See a list of active NIMHD-supported research projects studying food security and related topics .

NIMHD-Supported, NIH-Wide Initiatives

The PhenX Toolkit provides recommended and established data collection protocols for conducting biomedical research. There are PhenX protocols available for assessing and understanding food insecurity and food swamps .

The Strategic Plan for NIH Nutrition Research is the first NIH-wide strategic plan for nutrition research that highlights crosscutting, innovative opportunities to advance nutrition research from basic science to experimental design to research training. The plan emphasizes the need for studies on minority health and nutrition-related health disparities research.

Additional Resources and Data

The Centers for Disease Control’s Healthier Food Environments: Improving Access to Healthier Foods discusses CDC efforts to improve food access within the community.

The United States Department of Agriculture has two databases that compile national data on food accessibility:

- The Food Access Research Atlas provides food access data for populations within census tracts and mapped overviews of food access for low-income communities.

- The Food Environment Atlas assembles statistics on food environment indicators to stimulate research on the determinants of food choice and diet quality.

The Healthy People initiative provides 10-year, measurable public health objectives and useful tools to help track progress. The Healthy People 2030 includes food insecurity as a social determinant of health.

Page updated April 26, 2023

Page updated February 24, 2023

NIMHD Fact Sheet

Read about what is happening at NIMHD at the News and Events section

301-402-1366

Connect with Us

Subscribe to email updates

Staying Connected

- Funding Opportunities

- News & Events

- HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

- Privacy/Disclaimer/Accessibility Policy

- Viewers & Players

What Causes Food Insecurity and What are Solutions to It?

What is food insecurity.

Imagine the entire state of California not knowing where their next meal will come from. For 38.3 million Americans—just shy of California’s 39.5 million population—this uncertainty is a reality of daily life.

The effects of poverty are greatly varied, but many of them like homelessness, a lack of healthcare, and low wages, all are frequently a focus of public conversation. But several go largely undetected. One of these issues is food insecurity.

According to the USDA , food security “means access by all people at all times to enough food for a healthy life.” However, over 10% of the U.S. population struggle with food insecurity. Of these 38.3 million, 11.7 million of them—more than New York City’s population—are children.

Such figures lead to difficult questions: why do so many families and individuals struggle with food insecurity, and who are they? What are the consequences for our society when so many people go hungry? And finally, what can we do to fix this massive issue? In this article, we’ll get to know food insecurity and what we can do about it.

Let’s start with the term itself:

Giving Food Insecurity a Definition

Going by the USDA's definition of food security as “access by all people at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life.” Food insecurity, therefore, can be understood as any time an individual or family doesn’t experience food security.

Many families and individuals experience food insecurity differently. The USDA gives four general ranges of both food security and food insecurity to understand these differences in experiences:

Food Security:

- High Food Security: The USDA defines high food security as individuals or households that don’t report any difficulties with accessing food or suffering from limitations. These households probably don’t worry about food, at least in any significant way.

- Marginal Food Security: According to the USDA, households with marginal food security have reported their occasional anxiety of having enough food, although they don’t indicate any noteworthy changes to their diet or consumption.

Food Insecurity:

- Low Food Security: Households or individuals with low food security report that they consume lower quality food, less variety of foods, and have a generally less desirable diet, although they don’t necessarily consume less food overall.

- Very Low Food Security: Households with very low food security report that their eating patterns and food intake has been reduced or otherwise interrupted. These are people and families who may take actions such as foregoing meals to stretch their food over a longer period of time.

Essentially, food insecurity occurs when a person or group of people can’t access or afford enough quality food. Food insecurity is not hunger, although hunger may be a symptom of food insecurity.

Who is Food Insecure?

We’ve already briefly touched on how children are impacted greatly by food insecurity—you could populate a city larger than New York with all of America’s food-insecure children—but who are the communities most impacted by food insecurity?

Well, the answer is not so simple. With more than one in ten people in the U.S. being food insecure, you will find food insecurity in every community. However, some communities are more impacted by food insecurity than others. Households composed of Black or Hispanic families or individuals are twice as likely to be food insecure than the national average. Communities of color that have been and are still systematically oppressed and impoverished are the most affected by food insecurity.

What Causes Food Insecurity?

The causes that impact food insecurity are wide in scope, and we won’t be able to cover them all here. They are both historical and present-day, deliberate and unintended, but regardless, they are all real and impact a massive portion of our population here in the U.S.

Geography and urban planning has some impact on food insecurity. A food desert is a popular term used to describe areas where the residents can’t access affordable, healthy foods. This means a majority of the population lives a mile or more from an affordable grocery store in urban areas, and 10 miles in rural areas. For areas that have no public transportation or unreliable transport, individuals who don’t own a car, and individuals who struggle with mobility, healthy, nutritious foods are simply out of reach, both physically and economically.

However, despite their impact, pinning the issue of food insecurity on food deserts conveniently ignores the systemic issues contributing to food insecurity. Most people, even low-income individuals, don’t automatically grocery shop at whichever store is closest to them. They may instead opt for a preferred grocery store or chain with lower prices, or instead choose to shop near their workplace, chaining multiple trips together.

Thus, access, geographic location, and food deserts actually aren’t the main problems facing food-insecure households. The main cause of food insecurity is poverty . While mobility, transportation, and car-centricity are still issues that are deeply connected with poverty, geographic access, as stated by the USDA in a 2014 report , is not “associated with the percentage of households that [are] food insecure.”

The fact is that 38.3 million Americans simply can’t afford food, or enough quality food; living within a mile of a grocery store and having reliable transportation there and back still wouldn’t change that. Low wages and centuries of discrimination have led to a situation where many low-income households spend over a quarter of their income on food , whereas middle and high-income households spend more money, but still a smaller percentage of their income, on food.

The Impact of Food Insecurity

The impacts of food insecurity are wide-ranging. For one thing, considering that food-insecure households spend upwards of 27% of their income on food, it makes budgeting and prioritizing other expenses painfully difficult. When budgeting the cost of food in the face of other necessary expenses like housing, energy, and healthcare, it creates an impossible balancing act: to choose between staying in your apartment, eating, or taking necessary medications.

Medications, too, are related to food insecurity, as food insecurity has ranging health impacts for both children and adults. Food insecure adults may be at higher risk for chronic diseases such as diabetes , obesity , and depression .

Now, food insecurity is not permanent. It can be brief while a member of the household is between jobs, or during times of other financial hardship, or it can last over an extended period of time, particularly in the case of individuals who can’t work due to disabilities. However, children who experience extended food insecurity are even more at risk, as its effects can compound throughout their life and development.

Learning outcomes can also be adversely impacted by food insecurity. Inadequate nutrients from their diets can lead to a weakened immune system in children, which can lead to frequent absences. When food-insecure children are at school, they may be unable to focus, resulting in worse performance and retention. Essentially, when children experience food insecurity, it can set them up for challenges for the rest of their lives.

Solutions to Ending Food Insecurity

Systemic changes.

Continue Modernizing SNAP Benefits: The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, often known as SNAP , provides benefits to households and individuals struggling with food insecurity. However, while crucial to helping millions of families, SNAP benefits need to be modernized. They are still based on the USDA’s Thrifty Food Plan (TFP), which is no longer an accurate measure for food expenditures. The TFP doesn’t even meet all the U.S.’s federal nutrition standards .

SNAP benefits are also equal across the country, regardless of differences in cost of living—a feature that is very beneficial to some, while detrimental to others. Many households living in areas where they must devote a larger portion of their income to expenses like housing often have less money available for food, and SNAP benefits are insufficient in these instances. Additionally, SNAP benefits don’t account for the amount of time it takes to cook and prepare meals, a fact that does a great disservice to the many low-wage workers who need to work long, often odd hours to cover expenses such as rent—they’re already stretched for time.