Essay on Media and Violence

Introduction

Research studies indicate that media causes violence and plays a role in desensitization, aggressive behavior, fear of harm, and nightmares. Examples of media platforms include movies, video games, television, and music. Violence in media has also been associated with health concerns. The youth have been the most common victims of media exposure and thus stand higher chances of exposure to violence (Anderson, 2016). In the contemporary world, violence in media platforms has been growing, reaching heightened levels, which is dangerous for society. When you turn on the television, there is violence, social media platforms; there is violence when you go to the movies; there is violence. Studies indicate that an average person in the United States watches videos for nearly five hours in a day. In addition, three-quarters of television content contain some form of violence, and the games being played today have elements of violence. This paper intends to evaluate the concept of media messages and their influence on violent and deviant behaviors. Television networks and video games will be considered.

The Netflix effect involves the behavior of staying home all day, ordering food, and relaxing the couch to watch Netflix programs (McDonald & Smith-Rowsey, 2016). Netflix and binge-watching have become popular among the younger generation and thus are exposed to different kinds of content being aired. Studies indicate that continuous exposure to violent materials has a negative effect on the aggressive behavior of individuals. Netflix is a global platform in the entertainment industry (Lobato, 2019). Although, the company does not have the rights to air in major countries such as China, India, and Japan, it has wide audience. One of the reasons for sanctions is the issues of content being aired by the platform, which may influence the behaviors of the young generation. The primary goal of Netflix is entertainment; it’s only the viewers who have developed specific effects that affect their violent behaviors through imitation of the content.

Television Networks

Television networks focus on feeding viewers with the latest updates on different happenings across the globe. In other instances, they focus on bringing up advertisements and entertainment programs. There is little room for violent messages and content in the networks unless they are airing movie programs, which also are intended for entertainment. However, there has been evidence in the violence effect witnessed in television networks. Studies called the “Marilyn Monroe effect” established that following the airing of many suicidal cases, there has been a growth in suicides among the population (Anderson, Bushman, Donnerstein, Hummer, & Warburton, 2015). Actual suicide cases increased by 2.5%, which is linked to news coverage regarding suicide. Additionally, some coverages are filled with violence descriptions, and their aftermath with may necessitate violent behaviors in the society. For instance, if televisions are covering mass demonstrations where several people have been killed, the news may trigger other protests in other parts of the country.

Communications scholars, however, dispute these effects and link the violent behaviors to the individuals’ perception. They argue that the proportion of witnessing violent content in television networks is minimal. Some acts of violence are associated with what the individual perceives and other psychological factors that are classified into social and non-social instigators (Anderson et al., 2015). Social instigators consist of social rejection, provocation, and unjust treatment. Nonsocial instigators are physical objects present, which include weapons or guns. Also, there are environmental factors that include loud noises, overcrowding, and heat. Therefore, there is more explanation of the causes of aggressive behaviors that are not initiated by television networks but rather a combination of biological and environmental factors.

Video games

Researchers have paid more attention to television networks and less on video games. Children spend more time playing video games. According to research, more than 52% of children play video games and spend about 49 minutes per day playing. Some of the games contain violent behaviors. Playing violent games among youth can cause aggressive behaviors. The acts of kicking, hitting, and pinching in the games have influenced physical aggression. However, communication scholars argue that there is no association between aggression and video games (Krahé & Busching, 2015). Researchers have used tools such as “Competition Reaction Time Test,” and “Hot Sauce Paradigm” to assess the aggression level. The “Hot Sauce Paradigm” participants were required to make hot sauce tor tasting. They were required to taste tester must finish the cup of the hot sauce in which the tester detests spicy products. It was concluded that the more the hot sauce testers added in the cup, the more aggressive they were deemed to be.

The “Competition Reaction Time Test” required individuals to compete with another in the next room. It was required to press a button fast as soon as the flashlight appeared. Whoever won was to discipline the opponent with loud noises. They could turn up the volume as high as they wanted. However, in reality, there was no person in the room; the game was to let individuals win half of the test. Researchers intended to test how far individuals would hold the dial. In theory, individuals who punish their opponents in cruel ways are perceived to be more aggressive. Another way to test violent behaviors for gamer was done by letting participants finish some words. For instance, “M_ _ _ ER,” if an individual completes the word as “Murder” rather than “Mother,” the character was considered to possess violent behavior (Allen & Anderson, 2017). In this regard, video games have been termed as entertainment ideologies, and the determination of the players is to win, no matter how brutal the game might be.

In this paper, fixed assumptions were used to correlate violent behaviors and media objects. But that was not the case with regards to the findings. A fixed model may not be appropriate in the examination of time-sensitive causes of dependent variables. Although the model is applicable for assessing specific entities in a given industry, the results may not be precise.

Conclusion .

Based on the findings of the paper, there is no relationship between violent behaviors and media. Netflix effect does not influence the behavior of individuals. The perceptions of the viewers and players is what matters, and how they understand the message being conveyed. Individuals usually play video games and watch televisions for entertainment purposes. The same case applies to the use of social media platforms and sports competitions. Even though there is violent content, individuals focus on the primary objective of their needs.

Analysis of sources

The sources have been thoroughly researched, and they provide essential information regarding the relationship between violent behaviors and media messages. Studies conducted by various authors like Krahé & Busching did not establish any relationship between the two variables. Allen & Anderson (2017) argue that the models for testing the two variables are unreliable and invalid. The fixed assumptions effect model was utilized, and its limitations have been discussed above. Therefore, the authors of these references have not been able to conclude whether there is a connection between violence and media messages.

Allen, J. J., & Anderson, C. A. (2017). General aggression model. The International Encyclopedia of Media Effects , 1-15.

Anderson, C. A. (2016). Media violence effects on children, adolescents and young adults. Health Progress , 97 (4), 59-62.

Anderson, C. A., Bushman, B. J., Donnerstein, E., Hummer, T. A., & Warburton, W. (2015). SPSSI research summary on media violence. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy , 15 (1), 4-19.

Krahé, B., & Busching, R. (2015). Breaking the vicious cycle of media violence use and aggression: A test of intervention effects over 30 months. Psychology of Violence , 5 (2), 217.

Lobato, R. (2019). Netflix nations: the geography of digital distribution . NYU Press.

McDonald, K., & Smith-Rowsey, D. (Eds.). (2016). The Netflix effect: Technology and entertainment in the 21st century . Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Cite this page

Similar essay samples.

- Study on Agile Leadership in a Corporation

- Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel Analysis

- The oil industry in Azerbaijan and the need for forecasting activities

- Report on Strategic Warehouse Management

- History and reactions to Aviation Terrorism

- Crime Investigation Assignment

Media Violence and Aggressive Behavior Essay

It is said that television and media brought about new problems that are evident in the modern day and age. Mostly, these influences are harmful in relation to violence and people’s general behavior, which is characterized as careless, destructive and unpredictable.

In reality, there is a great difference and separation between the violence that is seen on TV and that in real life, as people will not become aggressive if their character is not based on aggression.

For a long time, there has been a debate that violence in the media causes more aggressive behavior in the person. There have been numerous studies, but the evidence is somewhat controversial. The majority of people believe that the causation of violent behavior by media is exaggerated. The social theorists suppose that people learn by modeling and imitating behavior.

There have been experiments where such imitation would be tested with children as participants. It has yielded imprecise results (Wells, 1997). Further studies and experimentation have not established any particular correlation because of the control variables being too fluid.

An important concept in movies and media is that they constantly remind the viewer that it is only the authorized people, like police officers and other authorities, are allowed to use violence as a last resource. In many instances, there is added humor, even though it does not diminish the violent and dangerous nature of the situation where a person is killed or their life is threatened.

In general, it is possible to assume that a person might get desensitized towards violence, blood, aggression and criminal behavior. It has been proven that the more a person is confronted with a certain stimuli, the more they will get used to it. This can be seen in many examples from real life (Casey, 2008).

Today, there are movies that show very gruesome and graphic scenes, and it is a fact that many people watch movies like “Saw” and it might make them more used to horror and blood. But people realize that it is a movie and a false, staged situation. A real life occurrence would be very different.

For example, if a movie does not have graphic images or scenes, it might create an idea of violence where people are controlled against their will or held hostage. From one perspective, it is said that the person will learn to like the violence and use it in real life. But a person’s character or individuality cannot learn to like a particular stimulus. If a person does not like to smoke, they will not get used to it by constantly smoking.

Or if someone likes a certain color or smell, a person cannot be made to like or unlike something. In the end, it is possible to see that there must be a link between violence and an already existing personal predisposition to it. The only people who will get affected by graphic violent media are those who require ideas in how to manifest own violent behavior.

From this perspective, it would be better if violence was excluded from media and movies. It can be left simple, as if when a person gets shot or hit, there are no close-ups to show the wound or any blood. It would be useful to promote that the only moral of the movies in relation to violence is that it is unlawful and unwanted by anyone. Most evidence supports the fact that there must be a predisposition towards violence.

It very much depends on an individual. A person who is kind and moral will not resolve to violence because it will conflict with their core moral beliefs, and no matter how often they see violence on the news or in movies, each time they will feel appalled and will not simulate such behavior (Freedman, 2002).

It is clear that a person, who resolved to violence, either grew up in aggressive circumstances where they thought that it was allowed or possible or they have some genetic malfunction. Majority of people are taught that violence is wrong and will not be tolerated by the law and society.

Modern civilized countries take every effort to make this as clear as possible and everyone, even the criminals, know that taking someone’s life or being aggressive towards someone is the highest crime and will be punished. Unfortunately, the evolving technology is becoming a greater part of human life. The 3D or hologram affects, not to mention virtual reality, can stimulate senses in ways that were not possible before.

There is very little evidence as to how the body and genetic information reacts and what it stores. There is a slight chance that a person who watches violence all their life and becomes desensitized to human pain and suffering, will record that information in genes and pass it on to the next generation (Holtzman, 2000).

In any case, there is always a limit as to violence on TV and its nature. The modern society wants to see more blood, which is evident from many movies, and the types of people that watch those movies are of specific character. But the general public seems unharmed by media, as it is too character specific.

Works Cited

Casey, Bernadette. Television studies: the key concepts . New York, NY: Routledge, 2008. Print.

Freedman, Jonathan. Media violence and its effect on aggression: Assessing the scientific evidence. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press, 2002. Print.

Holtzman, Linda. Media messages . Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2000. Print.

Wells, Alan. Mass media & society . London, England: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1997. Print.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, April 28). Media Violence and Aggressive Behavior. https://ivypanda.com/essays/violence-on-tv/

"Media Violence and Aggressive Behavior." IvyPanda , 28 Apr. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/violence-on-tv/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Media Violence and Aggressive Behavior'. 28 April.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Media Violence and Aggressive Behavior." April 28, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/violence-on-tv/.

1. IvyPanda . "Media Violence and Aggressive Behavior." April 28, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/violence-on-tv/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Media Violence and Aggressive Behavior." April 28, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/violence-on-tv/.

- Has 21st Century Media Desensitized Pre-Adults to Sex and Violence ?

- Mark Twain’s Excerpt From “Life on the Mississippi”

- Nature vs. Technology: Traveling Through the Dark by Stafford

- Grand Theft Auto Is Good for You?

- Curse Words Lose Their “Taboo” Status

- Clarisse’s Influence on Montag in "Fahrenheit 451"

- Education Today: Brief Analysis

- War and Violence: Predisposition in Human Beings

- Genetic Predisposition to Breast Cancer: Genetic Testing

- Psychological Determinants of Adolescent Predisposition to Deviant Behavior

- Shadowing a Substance Abuse Counselor

- Trauma and Sexually Abused Child

- Substance Abuse and the Related Problems

- Child Abuse Problem

- Human Trafficking and the Trauma It Leaves Behind

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Gray Matter

Does Media Violence Lead to the Real Thing?

By Vasilis K. Pozios , Praveen R. Kambam and H. Eric Bender

- Aug. 23, 2013

EARLIER this summer the actor Jim Carrey, a star of the new superhero movie “Kick-Ass 2,” tweeted that he was distancing himself from the film because, in the wake of the Sandy Hook massacre, “in all good conscience I cannot support” the movie’s extensive and graphically violent scenes.

Mark Millar, a creator of the “Kick-Ass” comic book series and one of the movie’s executive producers, responded that he has “never quite bought the notion that violence in fiction leads to violence in real life any more than Harry Potter casting a spell creates more boy wizards in real life.”

While Mr. Carrey’s point of view has its adherents, most people reflexively agree with Mr. Millar. After all, the logic goes, millions of Americans see violent imagery in films and on TV every day, but vanishingly few become killers.

But a growing body of research indicates that this reasoning may be off base. Exposure to violent imagery does not preordain violence, but it is a risk factor. We would never say: “I’ve smoked cigarettes for a long time, and I don’t have lung cancer. Therefore there’s no link between smoking cigarettes and lung cancer.” So why use such flawed reasoning when it comes to media violence?

There is now consensus that exposure to media violence is linked to actual violent behavior — a link found by many scholars to be on par with the correlation of exposure to secondhand smoke and the risk of lung cancer. In a meta-analysis of 217 studies published between 1957 and 1990, the psychologists George Comstock and Haejung Paik found that the short-term effect of exposure to media violence on actual physical violence against a person was moderate to large in strength.

Mr. Comstock and Ms. Paik also conducted a meta-analysis of studies that looked at the correlation between habitual viewing of violent media and aggressive behavior at a point in time. They found 200 studies showing a moderate, positive relationship between watching television violence and physical aggression against another person.

Other studies have followed consumption of violent media and its behavioral effects throughout a person’s lifetime. In a meta-analysis of 42 studies involving nearly 5,000 participants, the psychologists Craig A. Anderson and Brad J. Bushman found a statistically significant small-to-moderate-strength relationship between watching violent media and acts of aggression or violence later in life.

In a study published in the journal Pediatrics this year, the researchers Lindsay A. Robertson, Helena M. McAnally and Robert J. Hancox showed that watching excessive amounts of TV as a child or adolescent — in which most of the content contains violence — was causally associated with antisocial behavior in early adulthood. (An excessive amount here means more than two hours per weekday.)

The question of causation, however, remains contested. What’s missing are studies on whether watching violent media directly leads to committing extreme violence. Because of the relative rarity of acts like school shootings and because of the ethical prohibitions on developing studies that definitively prove causation of such events, this is no surprise.

Of course, the absence of evidence of a causative link is not evidence of its absence. Indeed, in 2005, The Lancet published a comprehensive review of the literature on media violence to date. The bottom line: The weight of the studies supports the position that exposure to media violence leads to aggression, desensitization toward violence and lack of sympathy for victims of violence, particularly in children.

In fact the surgeon general, the National Institute of Mental Health and multiple professional organizations — including the American Medical Association, the American Psychiatric Association and the American Psychological Association — all consider media violence exposure a risk factor for actual violence.

To be fair, some question whether the correlations are significant enough to justify considering media violence a substantial public health issue. And violent behavior is a complex issue with a host of other risk factors.

But although exposure to violent media isn’t the only or even the strongest risk factor for violence, it’s more easily modified than other risk factors (like being male or having a low socioeconomic status or low I.Q.).

Certainly, many questions remain and more research needs to be done to determine what specific factors drive a person to commit acts of violence and what role media violence might play.

But first we have to consider how best to address those questions. To prevent and treat public health issues like AIDS, cancer and heart disease, we focus on modifying factors correlated with an increased risk of a bad outcome. Similarly, we should strive to identify risk factors for violence and determine how they interact, who may be particularly affected by such factors and what can be done to reduce modifiable risk factors.

Naturally, debate over media violence stirs up strong emotions because it raises concerns about the balance between public safety and freedom of speech.

Even if violent media are conclusively found to cause real-life violence, we as a society may still decide that we are not willing to regulate violent content. That’s our right. But before we make that decision, we should rely on evidence, not instinct.

Vasilis K. Pozios, Praveen R. Kambam and H. Eric Bender are forensic psychiatrists and the founders of the consulting group Broadcast Thought .

The Facts on Media Violence

By Vanessa Schipani

Posted on March 8, 2018

In the wake of the Florida school shooting, politicians have raised concern over the influence of violent video games and films on young people, with the president claiming they’re “shaping young people’s thoughts.” Scientists still debate the issue, but the majority of studies show that extensive exposure to media violence is a risk factor for aggressive thoughts, feelings and behaviors.

The link between media violence and mass shootings is yet more tenuous. Compared with acts of aggression and violence, mass shootings are relatively rare events, which makes conducting conclusive research on them difficult.

President Donald Trump first raised the issue during a meeting on school safety with local and state officials, which took place a week after the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. The shooter, 19-year-old Nikolas Cruz, reportedly obsessively played violent video games.

Trump, Feb. 22: We have to look at the Internet because a lot of bad things are happening to young kids and young minds, and their minds are being formed. And we have to do something about maybe what they’re seeing and how they’re seeing it. And also video games. I’m hearing more and more people say the level of violence on video games is really shaping young people’s thoughts. And then you go the further step, and that’s the movies. You see these movies, they’re so violent.

Trump discussed the issue again with members of Congress on Feb. 28 during another meeting on school safety. During that discussion, Tennessee Rep. Marsha Blackburn claimed mothers have told her they’re “very concerned” that “exposure” to entertainment media has “desensitized” children to violence.

Iowa Sen. Chuck Grassley also said during the meeting: “[Y]ou see all these films about everybody being blown up. Well, just think of the impact that makes on young people.”

The points Trump and members of Congress raise aren’t unfounded, but the research on the subject is complex. Scientists who study the effect of media violence have taken issue with how the popular press has portrayed their work, arguing that the nuance of their research is often left out.

In a 2015 review of the scientific literature on video game violence, the American Psychological Association elaborates on this point.

APA, 2015: News commentators often turn to violent video game use as a potential causal contributor to acts of mass homicide. The media point to perpetrators’ gaming habits as either a reason they have chosen to commit their crimes or as a method of training. This practice extends at least as far back as the Columbine massacre (1999). … As with most areas of science, the picture presented by this research is more complex than is usually depicted in news coverage and other information prepared for the general public.

Here, we break down the facts — nuance included — on the effect of media violence on young people.

Is Media Violence a Risk Factor for Aggression?

The 2015 report by the APA on video games is a good place to start. After systematically going through the scientific literature, the report’s authors “concluded that violent video game use has an effect on aggression.”

In particular, the authors explain that this effect manifests as an increase in aggressive behaviors, thoughts and feelings and a decrease in helping others, empathy and sensitivity to aggression. Though limited, evidence also suggests that “higher amounts of exposure” to video games is linked to “higher levels of aggression,” the report said.

The report emphasized that “aggression is a complex behavior” caused by multiple factors, each of which increases the likelihood that an individual will be aggressive. “Children who experience multiple risk factors are more likely to engage in aggression,” the report said.

The authors came to their conclusions because researchers have consistently found the effect across three different kinds of studies: cross-sectional studies, longitudinal studies and laboratory experiments. “One method’s limits are offset by another method’s strengths,” the APA report explains, so only together can they be used to infer a causal relationship.

Cross-sectional studies find correlations between different phenomena at one point in time. They’re relatively easy to conduct, but they can’t provide causal evidence because correlations can be spurious . For example, an increase in video game sales might correlate with a decrease in violent crime, but that doesn’t necessarily mean video games prevent violent crime. Other unknown factors might also be at play.

Longitudinal panel studies collect data on the same group over time, sometimes for decades. They’re used to investigate long-term effects, such as whether playing video games as a child might correlate with aggression as an adult. These studies also measure other risk factors for aggression, such as harsh discipline from parents, with the aim of singling out the effect of media violence. For this reason, these studies provide better evidence for causality than cross-sectional studies, but they are more difficult to conduct.

Laboratory experiments manipulate one phenomenon — in this case, exposure to media violence — and keep all others constant. Because of their controlled environment, experiments provide strong evidence for a causal effect. But for the same reason, laboratory studies may not accurately reflect how people act in the real world.

This brings us to why debate still exists among scientists studying media violence. Some researchers have found that the experimental evidence backing the causal relationship between playing video games and aggression might not be as solid as it seems.

Last July, Joseph Hilgard , an assistant professor of psychology at Illinois State University, and others published a study in the journal Psychological Bulletin that found that laboratory experiments on the topic may be subject to publication bias. This means that studies that show the effect may be more likely to be published than those that don’t, skewing the body of evidence.

After Hilgard corrected for this bias, the effect of violent video games on aggressive behavior and emotions did still exist, but it was reduced, perhaps even to near zero. However, the effect on aggressive thoughts remained relatively unaffected by this publication bias. The researchers also found that cross-sectional studies weren’t subject to publication bias. They didn’t examine longitudinal studies, which have shown that youth who play more violent video games are more likely to report aggressive behavior over time.

Hilgard looked at a 2010 literature review by Craig A. Anderson , the director of the Center for the Study of Violence at Iowa State University, and others. Published in Psychological Bulletin, this review influenced the APA’s report.

In response, Anderson took a second look at his review and found that the effect of violent video games on aggression was smaller than he originally thought, but not as small as Hilgard found. For this reason, he argued the effect was still a “societal concern.”

To be clear, Hilgard is arguing that there’s more uncertainty in the field than originally thought, not that video games have no effect on aggression. He’s also not the first to find that research on video games may be suffering from publication bias.

But what about movies and television? Reviews of the literature on these forms of media tend to be less recent, Kenneth A. Dodge , a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University, told us by email.

Dodge, also one of the authors of the 2015 APA study, pointed us to one 1994 review of the literature on television published in the journal Communication Research that concluded that television violence also “increases aggressiveness and antisocial behavior.” Dodge told us he’s “confident” the effect this analysis and others found “would hold again today.”

Dodge also pointed us to a 2006 study that reviewed the literature on violent video games, films, television and other media together. “Most contemporary studies start with the premise that children are exposed [to violence] through so many diverse media that they start to group them together,” said Dodge.

Published in JAMA Pediatrics , the review found that exposure to violent media increases the likelihood of aggressive behavior, thoughts and feelings. The review also found media decreases the likelihood of helping behavior. All of these effects were “modest,” the researchers concluded.

Overall, most of the research suggests media violence is a risk factor for aggression, but some experts in the field still question whether there’s enough evidence to conclusively say there’s a link.

Is Violent Media a Risk Factor for Violence?

There’s even less evidence to suggest media violence is a risk factor for criminal violence.

“In psychological research, aggression is usually conceptualized as behavior that is intended to harm another,” while, “[v]iolence can be defined as an extreme form of physical aggression,” the 2015 APA report explains . “Thus, all violence is aggression, but not all aggression is violence.”

The APA report said studies have been conducted on media violence’s relationship with “criminal violence,” but the authors “did not find enough evidence of sufficient utility to evaluate whether” there’s a solid link to violent video game use.

This lack of evidence is due, in part, to the fact that there are ethical limitations to conducting experiments on violence in the laboratory, especially when it comes to children and teens, the report explains. That leaves only evidence from cross-sectional studies and longitudinal studies. So what do those studies say?

One longitudinal study , published in the journal Developmental Psychology in 2003, found that, out of 153 males, those who watched the most violent television as children were more likely 15 years later “to have pushed, grabbed, or shoved their spouses, to have responded to an insult by shoving a person” or to have been “to have been convicted of a crime” during the previous year. Girls who watched the most violent television were also more likely to commit similar acts as young women. These effects persisted after controlling for other risk factors for aggression, such as parental aggression and intellectual ability.

A 2012 cross-sectional study that Anderson, at Iowa State, and others published in the journal Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice did find that the amount of violent video games juvenile delinquents played correlated with how many violent acts they had committed over the past year. The violent acts included gang fighting, hitting a teacher, hitting a parent, hitting other students and attacking another person.

However, a 2008 review of the literature published in the journal Criminal Justice and Behavior concluded that “ the effects of exposure to media violence on criminally violent behavior have not been established.” But the authors clarify: “Saying that the effect has not been established is not the same as saying that the effect does not exist.”

In contrast to the APA report, Anderson and a colleague argue in a 2015 article published in American Behavioral Scientist that “research shows that media violence is a causal risk factor not only for mild forms of aggression but also for more serious forms of aggression, including violent criminal behavior.”

Why did Anderson and his colleagues come to different conclusions than the APA? He told us that the APA “did not include the research literature on TV violence,” and excluded “several important studies on video game effects on violent behavior published since 2013.”

In their 2015 article, Anderson and his colleague clarify that, even if there is a link, it “does not mean that violent media exposure by itself will turn a normal child or adolescent who has few or no other risk factors into a violent criminal or a school shooter.” They add, “Such extreme violence is rare, and tends to occur only when multiple risk factors converge in time, space, and within an individual.”

Multiple experts we spoke with did point to one factor unique to the United States that they argue increases the risk of mass shootings and lethality of violence in general — access to guns.

For example, Anderson told us by email: “There is a pretty strong consensus among violence researchers in psychology and criminology that the main reason that U.S. homicide rates are so much higher than in most Western democracies is our easy access to guns.”

Dodge, at Duke, echoed Anderson’s point.”The single most obvious and probably largest difference between a country like the US that has many mass shootings and other developed countries is the easy access to guns,” he said.

So while scientists disagree about how much evidence is enough to sufficiently support a causal link between media violence and real world violence, Trump and other politicians’ concerns aren’t unfounded.

Editor’s note: FactCheck.org is also based at the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg Public Policy Center. Hilgard, now at Illinois State, was a post doctoral fellow at the APPC.

Media Violence

About media violence, narrow the topic.

- Articles & Videos

- MLA Citation This link opens in a new window

- APA Citation This link opens in a new window

- Is there a correlation between violence in the media and crime?

- Is the media a scapegoat for societal issues?

- Is television news too violent?

- Will rating television shows have any effect?

- How does the advertisement of violent video games affect children?

- How can parents reduce the time their children spend watching television?

- Has social media and the Internet replaced broadcast television in the overexposure of violence?

- Next: Library Resources >>

- Last Updated: Feb 8, 2024 12:09 PM

- URL: https://libguides.broward.edu/Media_Violence

It is time for action to end violence against women: a speech by Lakshmi Puri at the ACP-EU Parliamentary Assembly

Date: Wednesday, 19 June 2013

Speech by Acting Head of UN Women Lakshmi Puri on Ending Violence against Women and Children at the ACP-EU Parliamentary Assembly on 18 June 2013, in Brussels

Good morning.

Honourable Co-Presidents of the ACP-EU Joint Parliamentary Assembly Ms. Joyce Laboso (congratulations on this new important role) and Mr. Louis Michel, Honourable Members of Parliament, Ladies and Gentlemen,

I thank you for inviting me to address you at this ACP-EU Joint Parliamentary Assembly on a matter that concerns all of us, all 79 African, Caribbean and Pacific nations and 27 European Union Member States represented in this forum, and ALL nations of the world.

It is one of the most pervasive violations of human rights in the world, one of the least prosecuted crimes, and one of the greatest threats to lasting peace and development.

I am talking about violence against women and children. I am honoured to be here, at your request, to address this urgent matter as you join together to advance human rights, democracy and the common values of humanity.

We all know that we have to do much more to respond to the cries for justice of women and children who have suffered violence. We have to do much more to end these horrible abuses and the impunity that allows these human rights violations to continue.

When we started UN Women two-and-a-half years ago, we made ending violence against women and girls one of our top priorities.

I think we can all agree that the time for complacency is long gone, has passed and belongs to another era. The silence on violence against women and children has been broken and now. Now is the time for stronger action.

It is time for action when up to 70 per cent of women in some countries face physical and/or sexual violence in their lifetime.

When one in three girls in developing countries is likely to be married as a child bride; when some 140 million girls and women have suffered female genital mutilation; when millions of women and girls are trafficked in modern-day slavery; and when women’s bodies are a battleground and rape is used as a tactic of war – it is time for action.

This violence against women and children has tremendous costs to communities, nations and societies—for public well-being, health and safety, and for school achievement, productivity, law enforcement, and public programmes and budgets.

If left unaddressed, these human rights violations pose serious consequences for current and future generations and for efforts to ensure peace and security, to reduce poverty and to achieve the Millennium Development Goals and the next generation of development goals we are discussing .

The effects of violence can remain with women and children for a lifetime, and can pass from one generation to another. Studies show that children who have witnessed, or been subjected to, violence are more likely to become victims or abusers themselves.

Violence against women and girls is an extreme manifestation of gender inequality and systemic gender-based discrimination. The right of women and children to live free of violence depends on the protection of their human rights and a strong chain of justice.

Countries that enact and enforce laws on violence against women have less gender-based violence. Today 160 countries have laws to address violence against women. However, in too many cases enforcement is lacking.

For an effective response to this violence, different sectors in society must work together.

A rape survivor must have rapid access to a health clinic that can administer emergency medical care, including treatment to prevent HIV and unintended pregnancies and counseling.

A woman who is beaten by her husband must have someplace to go with her children to enjoy safety, sanity and shelter.

A victim of violence must have confidence that when she files a police report, she will receive justice and the perpetrator will be punished.

And an adolescent boy in school who learns about health and sexuality must be taught that coercion, violence and discrimination against girls are unacceptable.

As the Acting Head of UN Women, I have the opportunity to meet with representatives from around the world, with government officials, civil society groups and members of the business community.

I can tell you that momentum is gathering, awareness is rising and I truly believe that long-standing indifference to violence against women and children is declining.

A recent study published in the American Sociological Review finds that transformation in attitudes are happening around the world.

The study looked at women’s attitudes about intimate partner violence in 26 countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean. It found that during the first decade of the 2000s, in almost every one of these countries, women became more likely to reject intimate partner violence.

The surveys found growing female rejection of domestic violence in 23 of the 26 countries. It found that “women with greater access to global cultural scripts through urban living, education, or access to media were more likely to reject intimate partner violence.”

The study’s author concludes that domestic violence is increasingly viewed as unacceptable due to changes in global attitudes. Yet even with this rising rejection, in nearly half of the countries, 12 of the 26 – more than half of women surveyed – still believe that domestic violence is justified. So even though attitudes are changing, we still have a long way to go to achieve the changes in attitudes that are necessary to end violence against women and children.

I witnessed this myself at the 57th Commission on the Status of Women at United Nations Headquarters in New York this past March. The agreement reached at the Commission on preventing and ending violence against women and girls was hard-won and tensions ran high throughout the final week of the session.

There were many times when it was unclear whether the Commission would end in deadlock, as it did 10 years before on the same theme, or if Member States were going to decide on a groundbreaking agreement.

In the end, thanks to the tireless work of civil society advocates and negotiations into the wee hours of Government delegates and UN Women colleagues, agreement was reached on a historic document that embraces the call of women around the world to break the cycle of violence and to protect the rights of women and girls.

The landmark agreement provides an action plan for Governments. It breaks this down into the four P’s: Protection of human rights, Prosecution of offenders, Prevention of violence, and Provision of Services to survivors.

Protecting human rights

When it comes to protecting rights, Governments are called on to review national legislation, practices and customs and abolish those that discriminate against women. Laws, policies and programmes that explicitly prohibit and punish violence must be put into place, in line with international agreements, and you as Members of Parliament can play a key role.

Based on findings from UN Women’s 2011-2012 Progress of the World’s Women report «In Pursuit of Justice », out of all the ACP countries, 37 have legislation against domestic violence, 34 have legislation against sexual harassment, and just nine have legislation against marital rape.

Providing services When it comes to providing services, the agreement calls for strong action to improve the quality and accessibility of services so that women have prompt access to services regardless of their location, race, age or income.

These include: health-care services including post-rape care, emergency contraception and abortion where legal; immediate and effective police responses, psychological support and counselling; legal advice and protection orders; shelter, telephone hotlines, and social assistance.

Responses must be timely and efficient to end a culture of hopelessness and impunity and foster a culture of justice and support. In almost all of the ACP countries comprehensive multisectoral services need to be put in place and made accessible to all.

Prosecuting offenders

When it comes to the prosecution of offenders, we know that ending impunity means that laws must be enforced.

Women must have access to the police to file a criminal report and receive legal advice and protection orders. The response to violence must be immediate, coordinated and effective so that crimes are punished and justice is secured. This is true for times of peace and conflict. There can be no lasting peace when women suffer sexual violence.

Courts and the justice system must be accessible and responsive to criminal and civil matters relating to violence against women. Women must be informed of their legal rights and supported to navigate the legal system.

And for this, we need more women police officers, prosecutors and judges, because we know that women serving on the frontlines of justice strengthen justice for women and children.

Preventing violence against women

When it comes to preventing violence, we must address the root causes of gender inequality and discrimination.

Evidence shows that where the “gender gap” is greater—in the status of women’s health, participation in the economy, education levels, and representation in politics— women are more likely to be subjected to violence. Especially important is economic empowerment as a prevention strategy

This means that we need to take a long-term, systemic and comprehensive approach that recognizes and protects women’s and children’s full and equal human rights.

We must promote a culture of equality between men and women through institutional and legal reform, education, awareness-raising and the full engagement of men and boys.

Honourable MPs,

Ending violence against women is one of UN Women’s key priorities and a critical part of UN Women’s mission to achieve gender equality and women’s empowerment.

Having said that, I would like to take this opportunity to tell you about UN Women’s role in ending violence against women and some of our achievements.

A top priority right now is working with countries to implement the recent agreement from the Commission on the Status of Women.

I am very pleased that UN Women and the EU have agreed to work on this together. We hope, with your support, to collaborate with more regional and cross-regional bodies and groupings such as the African Union, the Latin American and Caribbean States and the Pacific Forum to follow up on the agreement from the Commission on the Status of Women to end violence against women and girls.

Today UN Women is working in 85 countries, including in many ACP countries, to prevent violence in the first place, to end impunity for these crimes, to increase access to justice and to expand essential services to survivors.

Through our global, regional and national programmes, we support the development of laws, national action plans and policies, and training programmes. We provide funding to NGOs and civil society, contribute to advocacy and awareness-raising efforts, and support local initiatives.

We work together with UNICEF and UN Habitat on the Safe Cities programme to promote the safety of women and girls in public spaces. We now work in over 20 cities around the world, and this number continues to rise. Let me share with you a few exciting examples.

In Kigali, Rwanda, a Safe City Campaign was launched by the mayor’s office and other partners. The city is advocating for reforms to an existing law on gender-based violence to include measures on sexual harassment and violence in public spaces.

In Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, bylaws on local markets now include articles which address women’s safety. Women vendors are returning to the markets following the first phase of physical and social infrastructure improvements, and a focused awareness campaign is underway on sexual harassment and sexual violence.

UN Women also administers the UN Trust Fund to End Violence against Women. This is a leading global fund exclusively dedicated to addressing violence against women and girls. To date, the UN Trust Fund has delivered more than USD 86 million to 351 initiatives in 128 countries and territories, often directly to women’s organizations. The results have demonstrated many good practices that can, and should be, expanded.

Another global programme administered by UN Women is the Secretary-General’s UNiTE Campaign to End Violence against Women. Through strong advocacy, the campaign is mobilizing communities across the globe.

In Africa, the UNiTE Campaign organized the Kilimanjaro Climb hosted by Tanzania under the auspices of the President. This raised awareness of violence against women to the highest levels resulting in strengthened national commitments throughout Africa.

In the Pacific Region, the campaign succeeded in securing the “Pacific Members of Parliament UNiTE statement” – the first of its kind in the region, tabled at the Pacific Island Forum Leaders meeting in the Cook Islands.

In the Caribbean, 15 high-profile local artists produced a series of creative materials as part of the “Caribbean Artists, united to end violence against women” initiative, developed in the framework of the UNiTE Campaign. These materials were officially presented by the Secretary-General of CARICOM, Irwin LaRocque, last year during the gathering of CARICOM Heads of Government. This has contributed to give high visibility and strategically position the issue of violence against women in the region.

And UN Women’s COMMIT initiative has garnered new commitments by 58 Governments to prevent and end violence against women and girls. I applaud the ACP and EU member countries, and the European Union itself, for making commitments and encourage other countries to join them.

We must work together to seize the moment and move quickly so that the momentum is not lost. UN Women stands ready to assist Member States with other UN partners. We have already identified the key priorities and strategies we will be focusing:

First, Getting the Evidence: Data on Violence against Women Despite some progress in this area, there is still an urgent need to strengthen the evidence base as many countries still lack reliable and meaningful data. Actually, earlier this morning the European Women’s Lobby Centre on Violence against Women presented the findings from the 2013 Barometer focusing on rape in the EU.

In cooperation with our UN partners, we plan to build capacity in regions and countries to increase skills in data collection, analysis, dissemination and use, using the UN Statistical Commission Guidelines for obtaining data for the nine core indicators for violence against women.

Second, Strengthening Multi-sectoral Services for Survivors To this end, UN Women is working to devise globally agreed standards and guidelines on the essential services and responses that are required to meet the immediate and mid-term safety, health, and other needs of women and girls subjected to violence. I am very pleased that we are now working in partnership with UNFPA and other UN agencies to deliver this initiative.

Third, Preventing Violence against Women and Girls To this end, we will advocate for and work towards a shared understanding at the global level about what works, and provide guidance to States and other stakeholders on how to develop an holistic framework to prevent violence against women and girls; including by working systematically and consistently with male leaders and men and boys at all levels and by further strengthening women’s economic and political participation.

Fourth, Strengthening Partnerships We will continue to engage civil society and the private sector in ending violence against women and girls, working with survivors to empower them, making sure their experiences are taken into consideration in the development of responses; and working with those women and girls who suffer multiple and intersecting forms of violence who are particularly vulnerable.

Fifth and finally, we will continue to improve the knowledge base for ending violence against women by developing additional modules and updating our virtual knowledge centre.

Honourable Members of Parliament,

I would now like to take a brief moment to discuss the post-2015 development agenda, especially its role in addressing the issue of violence against women. I also had the occasion to deliver a video statement on this in your Women’s Forum which took place past Saturday and which concentrated on the post-2015 framework. I applaud the ACP-EU Joint Parliamentary Assembly for regularly organizing such a Women’s Forum and strengthening this network.

UN Women is calling for a stand-alone goal on gender equality, women’s rights and women’s empowerment and separately and concurrently gender equality mainstreamed across all goals. This is needed to address the structural foundations of gender-based inequality. To this effect, we are calling for the new framework to tackle three core areas: safety, access and voice, so women can live free of violence, enjoy equal access of opportunities and resources; and exercise their voice in leadership and participation.

In developing the post-2015 agenda and the 11th European Development Fund, we seek your support to ensure a strong focus on gender equality, women’s rights and empowerment and ending violence.

I thank you. All of us at UN Women look forward to strengthened collaboration with you and your countries through this forum to end violence against women and children.

- ‘One Woman’ – The UN Women song

- UN Under-Secretary-General and UN Women Executive Director Sima Bahous

- Kirsi Madi, Deputy Executive Director for Resource Management, Sustainability and Partnerships

- Nyaradzayi Gumbonzvanda, Deputy Executive Director for Normative Support, UN System Coordination and Programme Results

- Guiding documents

- Report wrongdoing

- Programme implementation

- Career opportunities

- Application and recruitment process

- Meet our people

- Internship programme

- Procurement principles

- Gender-responsive procurement

- Doing business with UN Women

- How to become a UN Women vendor

- Contract templates and general conditions of contract

- Vendor protest procedure

- Facts and Figures

- Global norms and standards

- Women’s movements

- Parliaments and local governance

- Constitutions and legal reform

- Preguntas frecuentes

- Global Norms and Standards

- Macroeconomic policies and social protection

- Sustainable Development and Climate Change

- Rural women

- Employment and migration

- Facts and figures

- Creating safe public spaces

- Spotlight Initiative

- Essential services

- Focusing on prevention

- Research and data

- Other areas of work

- UNiTE campaign

- Conflict prevention and resolution

- Building and sustaining peace

- Young women in peace and security

- Rule of law: Justice and security

- Women, peace, and security in the work of the UN Security Council

- Preventing violent extremism and countering terrorism

- Planning and monitoring

- Humanitarian coordination

- Crisis response and recovery

- Disaster risk reduction

- Inclusive National Planning

- Public Sector Reform

- Tracking Investments

- Strengthening young women's leadership

- Economic empowerment and skills development for young women

- Action on ending violence against young women and girls

- Engaging boys and young men in gender equality

- Sustainable development agenda

- Leadership and Participation

- National Planning

- Violence against Women

- Access to Justice

- Regional and country offices

- Regional and Country Offices

- Liaison offices

- UN Women Global Innovation Coalition for Change

- Commission on the Status of Women

- Economic and Social Council

- General Assembly

- Security Council

- High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development

- Human Rights Council

- Climate change and the environment

- Other Intergovernmental Processes

- World Conferences on Women

- Global Coordination

- Regional and country coordination

- Promoting UN accountability

- Gender Mainstreaming

- Coordination resources

- System-wide strategy

- Focal Point for Women and Gender Focal Points

- Entity-specific implementation plans on gender parity

- Laws and policies

- Strategies and tools

- Reports and monitoring

- Training Centre services

- Publications

- Government partners

- National mechanisms

- Civil Society Advisory Groups

- Benefits of partnering with UN Women

- Business and philanthropic partners

- Goodwill Ambassadors

- National Committees

- UN Women Media Compact

- UN Women Alumni Association

- Editorial series

- Media contacts

- Annual report

- Progress of the world’s women

- SDG monitoring report

- World survey on the role of women in development

- Reprint permissions

- Secretariat

- 2023 sessions and other meetings

- 2022 sessions and other meetings

- 2021 sessions and other meetings

- 2020 sessions and other meetings

- 2019 sessions and other meetings

- 2018 sessions and other meetings

- 2017 sessions and other meetings

- 2016 sessions and other meetings

- 2015 sessions and other meetings

- Compendiums of decisions

- Reports of sessions

- Key Documents

- Brief history

- CSW snapshot

- Preparations

- Official Documents

- Official Meetings

- Side Events

- Session Outcomes

- CSW65 (2021)

- CSW64 / Beijing+25 (2020)

- CSW63 (2019)

- CSW62 (2018)

- CSW61 (2017)

- Member States

- Eligibility

- Registration

- Opportunities for NGOs to address the Commission

- Communications procedure

- Grant making

- Accompaniment and growth

- Results and impact

- Knowledge and learning

- Social innovation

- UN Trust Fund to End Violence against Women

- About Generation Equality

- Generation Equality Forum

- Action packs

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2.1 Mass Media and Its Messages

Learning objectives.

- Explain the different ways mass media affects culture.

- Analyze cultural messages that the media send.

- Explain the ways new media have affected culture.

When media consumers think of media messages, they may think of televised public service announcements or political advertisements. These obvious examples provide a venue for the transfer of a message through a medium, whether that message is a plea for fire safety or the statement of a political position. But what about more abstract political advertisements that simply show the logo of a candidate and a few simple words? Media messages can range from overt statements to vague expressions of cultural values.

Disagreements over the content of media messages certainly exist. Consider the common allegations of political bias against various news organizations. Accusations of hidden messages or agenda-driven content have always been an issue in the media, but as the presence of media grows, the debate concerning media messages increases. This dialogue is an important one; after all, mass media have long been used to persuade. Many modern persuasive techniques stem from the use of media as a propaganda tool. The role of propaganda and persuasion in the mass media is a good place to start when considering various types of media effects.

Propaganda and Persuasion

Encyclopedia Britannica defines propaganda simply as the “manipulation of information to influence public opinion (Britannica Concise Encyclopedia).” This definition works well for this discussion because the study and use of propaganda has had an enormous influence on the role of persuasion in modern mass media. In his book The Creation of the Media , Paul Starr argues that the United States, as a liberal democracy, has favored employing an independent press as a public guardian, thus putting the media in an inherently political position (Starr, 2004). The United States—in contrast to other nations where media are held in check—has encouraged an independent commercial press and thus given the powers of propaganda and persuasion to the public (Starr, 2004).

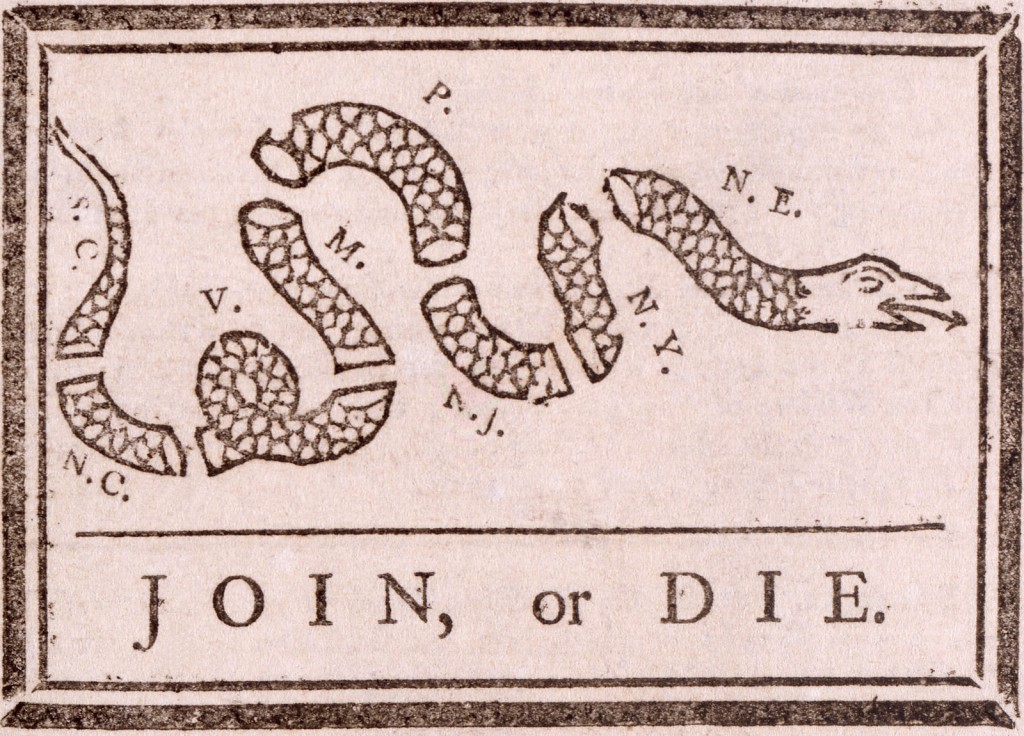

Benjamin Franklin used a powerful image of a severed snake to emphasize the importance of the colonies joining together during the American Revolution.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

Like any type of communication, propaganda is not inherently good or bad. Whether propaganda has a positive or negative effect on society and culture depends on the motivations of those who use it. People promoting movements as wide-ranging as Christianity, the American Revolution, and the communist revolutions of the 20th century have all used propaganda to disseminate their messages (Jowett & O’Donnell, 2006). Newspapers and pamphlets that glorified the sacrifices at Lexington and Concord and trumpeted the victories of George Washington’s army greatly aided the American Revolution. For example, Benjamin Franklin’s famous illustration of a severed snake with the caption “Join or Die” serves as an early testament to the power and use of print propaganda (Jowett & O’Donnell, 2006).

As you will learn in Chapter 4 “Newspapers” , the penny press made newspapers accessible to a mass audience and became a force for social cohesion during the 1830s (Jowett & O’Donnell, 2006). Magazines adopted a similar format later in the 19th century, and print media’s political and social power rose. In an infamous example of the new power of print media, some newspapers encouraged the Spanish-American War of 1898 by fabricating stories of Spanish atrocities and sabotage (Jowett & O’Donnell, 2006). For example, after the USS Maine sunk off the coast of Havana, Cuba, some newspapers blamed the Spanish—even though there was no evidence—fueling the public’s desire for war with Spain.

The present-day, pejorative connotation of propaganda stems from the full utilization of mass media by World War I–era governments to motivate the citizenry of many countries to go to war. Some media outlets characterized the war as a global fight between Anglo civilization and Prussian barbarianism. Although some of those fighting the war had little understanding of the political motivations behind it, wartime propaganda convinced them to enlist (Miller, 2005). As you will read in Chapter 12 “Advertising and Public Relations” , World War I legitimized the advertising profession in the minds of government and corporate leaders because its techniques were useful in patriotic propaganda campaigns. Corporations quickly adapted to this development and created an advertising boom in the 1920s by using World War I propaganda techniques to sell products (Miller, 2005).

In modern society, the persuasive power of the mass media is well known. Governments, corporations, nonprofit organizations, and political campaigns rely on both new and old media to create messages and to send them to the general public. The comparatively unregulated nature of U.S. media has made, for better or worse, a society in which the tools of public persuasion are available to everyone.

Media and Behavior

Although the mass media send messages created specifically for public consumption, they also convey messages that are not properly defined as propaganda or persuasion. Some argue that these messages influence behavior, especially the behavior of young people (Beatty, 2006). Violent, sexual, and compulsive behaviors have been linked to media consumption and thus raise important questions about the effects of media on culture.

Violence and the Media

On April 20, 1999, students Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold entered their Denver-area high school, Columbine High School, armed with semiautomatic weapons and explosives. Over the next few hours, the pair killed 12 classmates and one faculty member before committing suicide (Lamb, 2008). The tragedy and its aftermath captured national attention, and in the weeks following the Columbine High School shootings, politicians and pundits worked to assign blame. Their targets ranged from the makers of the first-person shooter video game Doom to the Hollywood studios responsible for The Matrix (Brook, 1999).

However, in the years since the massacre, research has revealed that the perpetrators were actually attempting a terrorist bombing rather than a first-person shooter style rampage (Toppo, 1999). But did violent video games so desensitize the two teenagers to violence that they could contemplate such a plan? Did movies that glorify violent solutions create a culture that would encourage people to consider such methods? Because modern culture is so immersed in media, the issue becomes a particularly complex one, and it can be difficult to understand the types of effects that violent media produce.

The 1999 Columbine High School shooting led to greater debate and criticism over violent video games.

Mentat Kilbernes – Columbine Massacre RPG – CC BY-NC 2.0.

A number of studies have verified certain connections between violent video games and violent behavior in young people. For example, studies have found that some young people who play violent video games reported angry thoughts and aggressive feelings immediately after playing. Other studies, such as one conducted by Dr. Chris A. Anderson and others, point to correlations between the amount of time spent playing violent video games and increased incidence of aggression (Anderson, 2003). However, these studies do not prove that video games cause violence. Video game defenders argue that violent people can be drawn to violent games, and they point to lower overall incidence of youth violence in recent years compared to past decades (Adams, 2010). Other researchers admit that individuals prone to violent acts are indeed drawn to violent media; however, they claim that by keeping these individuals in a movie theater or at home, violent media have actually contributed to a reduction in violent social acts (Goodman, 2008).

Whether violent media actually cause violence remains unknown, but unquestionably these forms of media send an emotional message to which individuals respond. Media messages are not limited to overt statements; they can also use emotions, such as fear, love, happiness, and depression. These emotional reactions partially account for the intense power of media in our culture.

Sex and the Media

In many types of media, sexual content—and its strong emotional message—can be prolific. A recent study by researchers at the University of North Carolina entitled “Sexy Media Matter: Exposure to Sexual Content in Music, Movies, Television, and Magazines Predicts Black and White Adolescents’ Sexual Behavior” found that young people with heavy exposure to sexually themed media ranging from music to movies are twice as likely to engage in early sexual behavior as young people with light exposure. Although the study does not prove a conclusive link between sexual behavior and sexually oriented media, researchers concluded that media acted as an influential source of information about sex for these youth groups (Dohney, 2006). Researcher Jane Brown thinks part of the reason children watch sexual content is related to puberty and their desire to learn about sex. While many parents are hesitant to discuss sex with their children, the media can act like a “super peer,” providing information in movies, television, music, and magazines (Dohney, 2006). You will learn more about the impact of sexual content in the media in Chapter 14 “Ethics of Mass Media” .

Cultural Messages and the Media

The media sends messages that reinforce cultural values. These values are perhaps most visible in celebrities and the roles that they adopt. Actors such as John Wayne and Marilyn Monroe came to represent aspects of masculinity and femininity that were adopted into mainstream culture during the mid-20th century. Throughout the 1990s, basketball player Michael Jordan appeared in television, film, magazines, and advertising campaigns as a model of athleticism and willpower. Singers such as Bob Dylan have represented a sense of freedom and rebellion against mainstream culture.

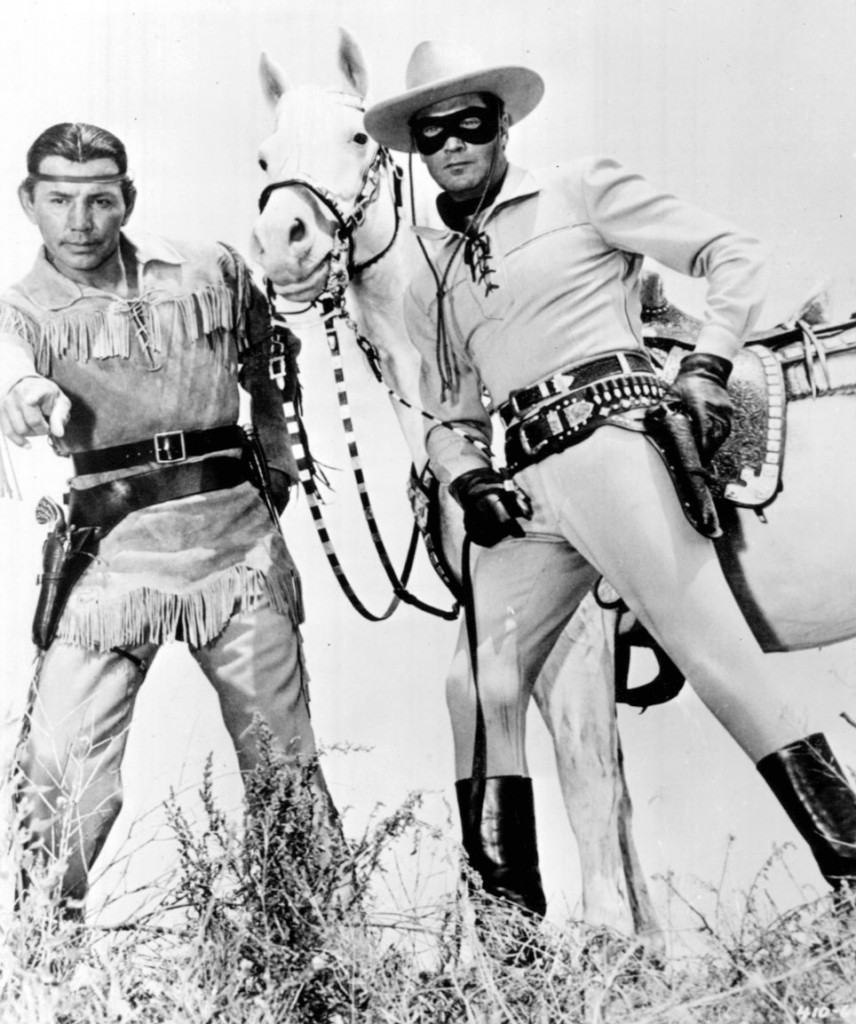

Tonto from The Lone Ranger reinforced cultural stereotypes about Native Americans. Do you think this type of characterization would be acceptable in modern television?

Although many consider celebrity culture superficial and a poor reflection of a country’s values, not all celebrities are simply entertainers. Civil rights leaders, social reformers, and other famous public figures have come to represent important cultural accomplishments and advancements through their representations in the media. When images of Abraham Lincoln or Susan B. Anthony appear in the media, they resonate with cultural and historical themes greatly separated from mere fame.

Celebrities can also reinforce cultural stereotypes that marginalize certain groups. Television and magazines from the mid-20th century often portrayed women in a submissive, domestic role, both reflecting and reinforcing the cultural limitations imposed on women at the time. Advertising icons developed during the early 20th century, such as Aunt Jemima and the Cream of Wheat chef, similarly reflected and reinforced a submissive, domestic servant role for African Americans. Other famous stereotypes—such as the Lone Ranger’s Native American sidekick, Tonto, or Mickey Rooney’s Mr. Yunioshi role in Breakfast at Tiffany’s —also reinforced American preconceptions about ethnic predispositions and capabilities.

Whether actual or fictional, celebrities and their assumed roles send a number of different messages about cultural values. They can promote courageous truth telling, hide and prolong social problems, or provide a concrete example of an abstract cultural value.

New Media and Society

New media—the Internet and other digital forms of communication—have had a large effect on society. This communication and information revolution has created a great deal of anguish about digital literacy and other issues that inevitably accompany such a social change. In his book on technology and communication, A Better Pencil , Dennis Baron discusses this issue:

For Plato, only speech, not writing, can produce the kind of back-and-forth—the dialogue—that’s needed to get at the truth…the text, orphaned by its author once it’s on the page, cannot defend itself against misreading…. These are strong arguments, but even in Plato’s day they had been rendered moot by the success of the written word. Although the literacy rate in classical Greece was well below 10 percent, writing had become an important feature of the culture. People had learned to trust and use certain kinds of writing—legal texts, public inscriptions, business documents, personal letters, and even literature—and as they did so, they realized that writing, on closer examination, turned out to be neither more nor less reliable or ambiguous than the spoken word, and it was just as real (Baron, 2009).

Baron makes the point that all communication revolutions have created upheavals and have changed the standards of literacy and communication. This historical perspective gives a positive interpretation to some otherwise ominous developments in communication and culture.

Information

The Internet has made an incredible amount of new information available to the general public. Both this wealth of information and the ways people process it are having an enormous effect on culture. New perceptions of information have emerged as access to it grows. Older-media consumption habits required in-depth processing of information through a particular form of media. For example, consumers read, watched, or viewed a news report in its entirety, typically within the context of a news publication or program. Fiction appeared in book or magazine form.

Today, information is easier to access, thus more likely to traverse several forms of media. An individual may read an article on a news website and then forward part of it to a friend. That person in turn describes it to a coworker without having seen the original context. The ready availability of information through search engines may explain how a clearly satirical Onion article on the Harry Potter phenomenon came to be taken as fact. Increasingly, media outlets cater to this habit of searching for specific bits of information devoid of context. Information that will attract the most attention is often featured at the expense of more important stories. At one point on March 11, 2010, for example, The Washington Post website’s most popular story was “Maintaining a Sex Life (Kakutani, 2010).”

Another important development in the media’s approach to information is its increasing subjectivity. Some analysts have used the term cyberbalkanization to describe the way media consumers filter information. Balkanization is an allusion to the political fragmentation of Eastern Europe’s Balkan states following World War I, when the Ottoman Empire disintegrated into a number of ethnic and political fragments. Customized news feeds allow individuals to receive only the kinds of news and information they want and thus block out sources that report unwanted stories or perspectives. Many cultural critics have pointed to this kind of information filtering as the source of increasing political division and resulting loss of civic discourse. When media consumers hear only the information they want to, the common ground of public discourse that stems from general agreement on certain principles inevitably grows smaller (Kakutani, 2010).

On one hand, the growth of the Internet as the primary information source exposes the public to increased levels of text, thereby increasing overall literacy. Indeed, written text is essential to the Internet: Web content is overwhelmingly text-based, and successful participation in Internet culture through the use of blogs, forums, or a personal website requires a degree of textual literacy that is not necessary for engagement in television, music, or movies.

Critics of Internet literacy, however, describe the majority of forum and blog posts as subliterate, and argue that the Internet has replaced the printed newspapers and books that actually raised the standards of literacy. One nuanced look at the Internet’s effect on the way a culture processes and perceives information states that literacy will not simply increase or decrease, but will change qualitatively (Choney, 2010). Perhaps the standards for literacy will shift to an emphasis on simplicity and directness, for example, rather than on elaborate uses of language.

President Barack Obama fired General Stanley McChrystal after a controversial Rolling Stone story in which McChrystal spoke poorly of the Obama administration was leaked on the Internet.

Certainly, the Internet has affected the way that cultures consume news. The public expects to receive information quickly, and news outlets respond rapidly to breaking stories. On Monday, June 21, 2010, for example, a spokesperson for Rolling Stone magazine first released quotes from a story featuring General Stanley McChrystal publicly criticizing members of the Obama administration on matters of foreign policy. By that evening, the story had become national news despite the fact Rolling Stone didn’t even post it to its website until Tuesday morning—some time after several news outlets had already posted the entire story on their own sites. Later that same day, McChrystal issued a public apology, and on Wednesday flew to Washington where President Barack Obama fired him. The printed Rolling Stone issue featuring the article hit newsstands Friday, 2 days after McChrystal had been replaced (Timpane, 2010).

Convergence Culture

The term convergence can hold several different meanings. In his book Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide , Henry Jenkins offers a useful definition of convergence as it applies to new media:

“By convergence, I mean the flow of content across multiple media platforms, the cooperation between multiple media industries, and the migratory behavior of media audiences who will go almost anywhere in search of the kinds of entertainment experiences they want (Jenkins, 2006).”

A self-produced video on the YouTube website that gains enormous popularity and thus receives the attention of a news outlet is a good example of this migration of both content and audiences. Consider this flow: The video appears and gains notoriety, so a news outlet broadcasts a story about the video, which in turn increases its popularity on YouTube. This migration works in a number of ways. Humorous or poignant excerpts from television or radio broadcasts are often posted on social media sites and blogs, where they gain popularity and are seen by more people than had seen the original broadcast.

Thanks to new media, consumers now view all types of media as participatory. For example, the massively popular talent show American Idol combines an older-media format—television—with modern media consumption patterns by allowing the home audience to vote for a favorite contestant. However, American Idol segments regularly appear on YouTube and other websites, where people who may never have seen the show comment on and dissect them. Phone companies report a regular increase in phone traffic following the show, presumably caused by viewers calling in to cast their votes or simply to discuss the program with friends and family. As a result, more people are exposed to the themes, principles, and culture of American Idol than the number of people who actually watch the show (Jenkins, 2006).

New media have encouraged greater personal participation in media as a whole. Although the long-term cultural consequences of this shift cannot yet be assessed, the development is undeniably a novel one. As audiences become more adept at navigating media, this trend will undoubtedly increase.

Bert Is Evil

Jughead – evil bert – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.