The Differences Between Communism and Socialism

Public Domain/Wikipedia Commons

- History & Major Milestones

- U.S. Constitution & Bill of Rights

- U.S. Legal System

- U.S. Political System

- Defense & Security

- Campaigns & Elections

- Business & Finance

- U.S. Foreign Policy

- U.S. Liberal Politics

- U.S. Conservative Politics

- Women's Issues

- Civil Liberties

- The Middle East

- Race Relations

- Immigration

- Crime & Punishment

- Canadian Government

- Understanding Types of Government

- B.S., Texas A&M University

The difference between communism and socialism is not conveniently clear-cut. The two terms are often used interchangeably, but these economic and political theories are not the same. Both communism and socialism arose from protests against the exploitation of the working class during the Industrial Revolution.

While applications of their economic and social policies vary, several modern countries—all ideologically opposed to capitalism —are perceived as either communist or socialist. In order to understand contemporary political debates, it's important to know the similarities and differences between communism and socialism.

Communism Vs. Socialism

In both communism and socialism, the people own the factors of economic production. The main difference is that under communism, most property and economic resources are owned and controlled by the state (rather than individual citizens); under socialism, all citizens share equally in economic resources as allocated by a democratically-elected government. This difference and others are outlined in the table below.

Key Similarities

Communism and socialism both grew out of grass-roots opposition to the exploitation of workers by wealthy businesses during the Industrial Revolution . Both assume that all goods and services will be produced by government-controlled institutions or collective organizations rather than by privately-owned businesses. In addition, the central government is mainly responsible for all aspects of economic planning, including matters of supply and demand .

Key Differences

Under communism, the people are compensated or provided for based on their needs. In a pure communist society, the government provides most or all food, clothing, housing and other necessities based on what it considers to be the needs of the people. Socialism is based on the premise the people will be compensated based on their level of individual contribution to the economy. Effort and innovation are thus rewarded under socialism.

Pure Communism Definition

Pure communism is an economic, political, and social system in which most or all property and resources are collectively owned by a class-free society rather than by individual citizens. According to the theory developed by the German philosopher, economist, and political theorist Karl Marx , pure communism results in a society in which all people are equal and there is no need for money or the accumulation of individual wealth. There is no private ownership of economic resources, with a central government controlling all facets of production. Economic output is distributed according to the needs of the people. Social friction between white and blue-collar workers and between rural and urban cultures will be eliminated, freeing each person to achieve his or her highest human potential.

Under pure communism, the central government provides the people with all basic necessitates, such as food, housing, education, and medical care, thus allowing the people to share equally from the benefits of collective labor. Free access to these necessities depends on constant advances in technology contributing to ever-greater production.

Karl Marx and the Origins of Communism

Socialism arose as a response to the struggles of the working class amidst the extreme social and economic changes caused by the Industrial Revolution in Europe and later in the United States. As many workers grew increasingly poor, factory owners and other industrialists accrued massive wealth.

During the first half of the 19th century, early socialist thinkers like Henri de Saint-Simon, Robert Owen and Charles Fourier proposed ways in which society might be reorganized in a manner embracing cooperation and community, rather than the competitiveness inherent in capitalism , where the free market controlled the supply and demand of goods.

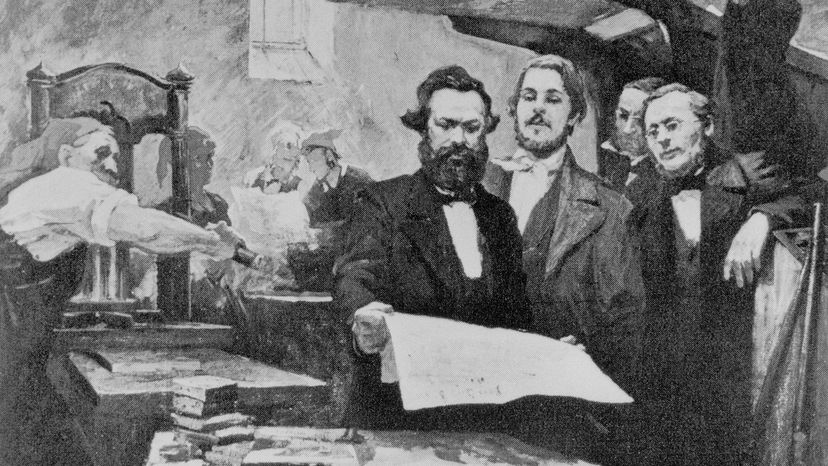

In 1848, the German political philosopher and economist Karl Marx , with his collaborator Friedrich Engels, published The Communist Manifesto , which included a chapter criticizing those earlier socialist models as utterly unrealistic “utopian” dreams.

Marx argued that all history was a history of class struggles, and that the working class, or the “proletariat,” would inevitably triumph over the capital class, or the “bourgeoisie,” and win control over the means of production, forever erasing all classes.

“The modern bourgeois society that has sprouted from the ruins of feudal society has not done away with class antagonisms. It has but established new classes, new conditions of oppression, new forms of struggle in place of the old ones,” wrote Marx and Engels.

Often referred to as “revolutionary socialism,” Communism also originated as a reaction to the Industrial Revolution, and came to be defined by Marx’s theories—taken to their extreme end. Marxists often refer to socialism as an early necessary phase on the way from capitalism to communism. Marx and Engels themselves didn’t consistently or clearly differentiate communism from socialism, which helped ensure lasting confusion between the two terms.

In 1875, Marx coined the phrase used to summarize communism, “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.”

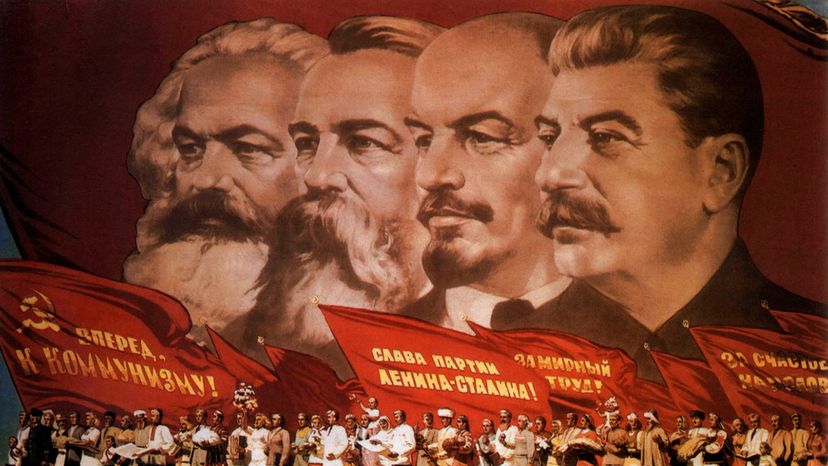

The Communist Manifesto

The ideology of modern communism began to form during the French Revolution fought between 1789 and 1802. In 1848, Marx and Friedrich Engels published their still-influential thesis “ Communist Manifesto .” Rather than the Christian overtones of earlier communist philosophies, Marx and Engels suggested that modern communism demanded a materialistic and purely scientific analysis of the past and future of human society. “The history of all hitherto existing society,” they wrote, “is the history of class struggles .”

The Communist Manifesto depicts the French Revolution as the point at which when the “bourgeoisie,” or merchant class took control of France’s economic “means of production” and replaced the feudal power structure, paving the way for capitalism . According to Marx and Engels, the French Revolution replaced the medieval class struggle between the peasant serfs and the nobility with the modern struggle between the bourgeois owners of capital and the working class “proletariat.”

Pure Socialism Definition

Pure socialism is an economic system under which each individual—through a democratically elected government—is given an equal share of the four factors or economic production: labor, entrepreneurship, capital goods, and natural resources. In essence, socialism is based on the assumption that all people naturally want to cooperate, but are restrained from doing so by the competitive nature of capitalism.

Socialism is an economic system where everyone in society equally owns the factors of production. The ownership is acquired through a democratically elected government. It could also be a cooperative or public corporation in which everyone owns shares. As in a command economy , the socialist government employs centralized planning to allocate resources based on both the needs of individuals and society as a whole. Economic output is distributed according to each individual’s ability and level of contribution.

In 1980, American author and sociologist Gregory Paul paid homage to Marx in coining the phrase commonly used to describe socialism, “From each according to his ability, to each according to his contribution.”

What Is a Social Democracy?

Democratic socialism is an economic, social, and political ideology holding that while both the society and economy should be run democratically, they should be dedicated to meeting the needs of the people as a whole, rather than encouraging individual prosperity as in capitalism. Democratic socialists advocate the transition of society from capitalism to socialism through existing participatory democratic processes, rather than revolution as characterized by orthodox Marxism. Universally-used services such as housing, utilities, mass transit, and health care are distributed by the government, while consumer goods are distributed by a capitalistic free market.

The latter half of the 20th century saw the emergence of a more moderate version of socialist democracy advocating a mixture of socialist and capitalist control of all means of economic production supplemented by extensive social welfare programs to help provide the basic needs of the people.

What Is Green Socialism?

As a recent outgrowth of the environmental movement and the climate change debate, green socialism or “eco-socialism” places its economic emphasis on the maintenance and utilization of natural resources. This is achieved largely through government ownership of the largest, most resource consumptive corporations. The use of “green” resources, such as renewable energy, public transit, and locally sourced food is emphasized or mandated. Economic production focuses on meeting the basic needs of the people, rather than a wasteful excess of unneeded consumer goods. Green socialism often offers a guaranteed minimum livable income to all citizens regardless of their employment status.

Communist Countries

It is difficult to classify countries as being either communist or socialist. Several countries, while ruled by the Communist Party, declare themselves to be socialist states and employ many aspects of socialist economic and social policy. Three countries typically considered communist states—mainly due to their political structure—are Cuba, China, and North Korea.

The Communist Party of China owns and strictly controls all industry, which operates solely to generate profits for the government through its successful and growing export of consumer goods. Health care and primary through higher education are run by the government and provided free of charge to the people. However, housing and property development operate under a highly competitive capitalist system.

The Communist Party of Cuba owns and operates most industries, and most of the people work for the state. Government-controlled health care and primary through higher education are provided free. Housing is either free or heavily subsidized by the government.

North Korea

Ruled by the Communist Party until 1946, North Korea now operates under a “Socialist Constitution of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea.” However, the government owns and controls all farmland, workers, and food distribution channels. Today, the government provides universal health and education for all citizens. Private ownership of property is forbidden. Instead, the government grants people the right to government-owned and assigned homes.

Socialist Countries

Once again, most modern countries that identify themselves to be socialist may not strictly follow the economic or social systems associated with pure socialism. Instead, most countries generally considered socialist actually employ the policies of democratic socialism.

Norway, Sweden, and Denmark all employ similar predominantly socialist systems. The democratically chosen governments of all three countries provide free health care, education, and lifetime retirement income. As a result, however, their citizens pay some of the world’s highest taxes. All three countries also have highly successful capitalist sectors. With most of their needs provided by their governments, the people see little need to accumulate wealth. As a result, about 10% of the people hold more than 65% of each nation’s wealth.

Additional References

- Engels, Frederick (1847). " Principles of Communism .”

- Bukharin, Nikoli. (1920). " The ABCs of Communism .”

- Lenin, Vladimir (1917). " The State and Revolution Chapter 5, Section 3 ."

- "The Difference Between Communism and Socialism." Investopedia (2018).

- Marx, Karl (1875). " The Critique of the Gotha Programme (From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs)"

- Paul, Gregory and Stuart, Robert C. " Comparing Economic Systems in the Twenty-First Century ." Cengage Learning (1980). ISBN: 9780618261819.

- Heilbroner, Robert. " Socialism ." Library of Economics and Liberty.

Kallie Szczepanski contributed to this article.

Pomerleau, Kyle. "How Scandinavian Countries Pay for Their Government Spending." Tax Foundation . 10 June 2015.

Lundberg, Jacob, and Daniel Waldenström. "Wealth Inequality in Sweden: What Can We Learn from Capitalized Income Tax Data?" Institute of Labor Economics, Apr. 2016.

- What Is Communism? Definition and Examples

- What Is Socialism? Definition and Examples

- Socialism vs. Capitalism: What Is the Difference?

- The Main Points of "The Communist Manifesto"

- What Is a Traditional Economy? Definition and Examples

- Command Economy Definition, Characteristics, Pros and Cons

- What Is Anarchy? Definition and Examples

- A Brief Biography of Karl Marx

- What Is Capitalism?

- What You Need to Know About the Paris Commune of 1871

- Understanding Karl Marx's Class Consciousness and False Consciousness

- Karl Marx's Greatest Hits

- Mode of Production in Marxism

- 15 Major Sociological Studies and Publications

- A List of Current Communist Countries in the World

- What Is Social Class, and Why Does it Matter?

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

How Are Socialism and Communism Different?

By: Sarah Pruitt

Updated: November 4, 2020 | Original: October 22, 2019

Both socialism and communism are essentially economic philosophies advocating public rather than private ownership, especially of the means of production, distribution and exchange of goods (i.e., making money) in a society. Both aim to fix the problems they see as created by a free-market capitalist system, including the exploitation of workers and a widening gulf between rich and poor.

But while socialism and communism share some basic similarities, there are also important differences between them.

Karl Marx and the Origins of Communism

Socialism emerged in response to the extreme economic and social changes caused by the Industrial Revolution , and particularly the struggles of workers. Many workers grew increasingly poor even as factory owners and other industrialists accrued massive wealth.

In the first half of the 19th century, early socialist thinkers like Henri de Saint-Simon, Robert Owen and Charles Fourier presented their own models for reorganizing society along the lines of cooperation and community, rather than the competition inherent in capitalism, where the free market controlled the supply and demand of goods.

Then came Karl Marx , the German political philosopher and economist who would become one of the most influential socialist thinkers in history. With his collaborator Friedrich Engels, Marx published The Communist Manifesto in 1848, which included a chapter criticizing those earlier socialist models as utterly unrealistic “utopian” dreams.

Marx argued that all history was a history of class struggles, and that the working class (or proletariat) would inevitably triumph over the capital class (bourgeoisie) and win control over the means of production, forever erasing all classes.

Communism , sometimes referred to as revolutionary socialism, also originated as a reaction to the Industrial Revolution, and came to be defined by Marx’s theories—taken to their extreme end. In fact, Marxists often refer to socialism as the first, necessary phase on the way from capitalism to communism. Marx and Engels themselves didn’t consistently or clearly differentiate communism from socialism, which helped ensure lasting confusion between the two terms.

Key Differences Between Communism and Socialism

Under communism, there is no such thing as private property. All property is communally owned, and each person receives a portion based on what they need. A strong central government—the state—controls all aspects of economic production, and provides citizens with their basic necessities, including food, housing, medical care and education.

By contrast, under socialism, individuals can still own property. But industrial production, or the chief means of generating wealth, is communally owned and managed by a democratically elected government.

Another key difference in socialism versus communism is the means of achieving them. In communism, a violent revolution in which the workers rise up against the middle and upper classes is seen as an inevitable part of achieving a pure communist state. Socialism is a less rigid, more flexible ideology. Its adherents seek change and reform, but often insist on making these changes through democratic processes within the existing social and political structure, not overthrowing that structure.

In his 1875 writing, Critique of the Gotha Program , Marx summarized the communist philosophy in this way: “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.” By contrast, socialism is based on the idea that people will be compensated based on their level of individual contribution to the economy.

Unlike in communism, a socialist economic system rewards individual effort and innovation. Social democracy, the most common form of modern socialism, focuses on achieving social reforms and redistribution of wealth through democratic processes, and can co-exist alongside a free-market capitalist economy.

Socialism and Communism in Practice

Led by Vladimir Lenin , the Bolsheviks put Marxist theory into practice with the Russian Revolution of 1917, which led to the creation of the world’s first communist government. Communism existed in the Soviet Union until its fall in 1991.

Today, communism and socialism exist in China, Cuba, North Korea, Laos and Vietnam—although in reality, a purely communist state has never existed. Such countries can be classified as communist because in all of them, the central government controls all aspects of the economic and political system. But none of them have achieved the elimination of personal property, money or class systems that the communist ideology requires.

Likewise, no country in history has achieved a state of pure socialism. Even countries that are considered by some people to be socialist states, like Norway, Sweden and Denmark, have successful capitalist sectors and follow policies that are largely aligned with social democracy. Many European and Latin American countries have adopted socialist programs (such as free college tuition, universal health care and subsidized child care) and even elected socialist leaders, with varying levels of success.

In the United States, socialism has not historically enjoyed as much success as a political movement. Its peak came in 1912, when Socialist Party presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs won 6 percent of the vote. But at the same time, U.S. programs once considered socialist, such as Medicare and Social Security , have been integrated into American life.

What Is Democratic Socialism?

Democratic socialism, a growing U.S. political movement in recent years, lands somewhere in between social democracy and communism. Like communists, democratic socialists believe workers should control the bulk of the means of production, and not be subjected to the will of the free market and the capitalist classes. But they believe their vision of socialism must be achieved through democratic processes, rather than revolution.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Communism vs. Socialism

In a way, communism is an extreme form of socialism . Many countries have dominant socialist political parties but very few are truly communist. In fact, most countries - including staunch capitalist bastions like the U.S. and U.K. - have government programs that borrow from socialist principles.

Socialism is sometimes used interchangeably with communism but the two philosophies have some stark differences. Most notably, while communism is a political system, socialism is primarily an economic system that can exist in various forms under a wide range of political systems.

In this comparison we look at the differences between socialism and communism in detail.

Comparison chart

Economic differences between socialists and communists.

In a Socialist economy, the means of producing and distributing goods is owned collectively or by a centralized government that often plans and controls the economy. On the other hand, in a communist society, there is no centralized government - there is a collective ownership of property and the organization of labor for the common advantage of all members.

For a Capitalist society to transition, the first step is Socialism. From a capitalist system, it is easier to achieve the Socialist ideal where production is distributed according to people's deeds (quantity and quality of work done). For Communism (to distribute production according to needs ), it is necessary to first have production so high that there is enough for everyone's needs. In an ideal Communist society, people work not because they have to but because they want to and out of a sense of responsibility .

Political differences

Socialism rejects a class-based society. But socialists believe that it is possible to make the transition from capitalism to socialism without a basic change in the character of the state. They hold this view because they do not think of the capitalist state as essentially an institution for the dictatorship of the capitalist class, but rather as a perfectly good piece of machinery which can be used in the interest of whichever class gets command of it. No need, then, for the working class in power to smash the old capitalist state apparatus and set up its own—the march to socialism can be made step by step within the framework of the democratic forms of the capitalist state. Socialism is primarily an economic system so it exists in varying degrees and forms in a wide variety of political systems.

On the other hand, communists believe that as soon as the working class and its allies are in a position to do so they must make a basic change in the character of the state; they must replace capitalist dictatorship over the working class with workers’ dictatorship over the capitalist class as the first step in the process by which the existence of capitalists as a class (but not as individuals) is ended and a classless society is eventually ushered in.

Video: Socialism vs. Communism

The following is a very opinionated video that explains the differences between communism and socialism:

- World Socialist Movement

- Wikipedia: Socialism

- Wikipedia: Communism

Related Comparisons

Share this comparison via:

If you read this far, you should follow us:

"Communism vs Socialism." Diffen.com. Diffen LLC, n.d. Web. 26 Feb 2024. < >

Comments: Communism vs Socialism

Anonymous comments (5).

September 5, 2010, 5:47pm No political system works the way it should because in every system there are always going to be those who have the power and change the system to make themselves more powerful. That is the way of Humanity. Politics is a twin to religion in that no person agrees with every tenet of their party/group/sect and has their own views as to how things should be, or what is the truth. People thrive on conflict/competition and because of that there is no "system" that will work for everyone, or in every situation, because we all seem to "agree to disagree" about almost all issues. Everyone wants more...most cannot be content just being content and need to feel "better" than someone to feel good about their own situation. Political leaders are usually in it for the power that comes with the office, not to really make a change for the good of the many. NO decision is for the good of everyone, except possibly the "keep the stupid from breeding" thing, but, good luck with that! — 98.✗.✗.193

March 23, 2014, 3:51am Socialism is a non-profit system in which people pay only for the cost of something, without paying extra to enrich a shareholder who didn't actually do any work. Imagine replacing corporations with nonprofit cooperatives. The workers benefit, because they keep the money they receive for their labor. The consumers benefit, because they get things at cost. We already do this for certain services, like public roads, police and fire departments, libraries, and public parks. Socialism is compatible with democracy and freedom. Corporate capitalism is an insane system that adds a third party into the transaction who overcharges the consumer, underpays the workers, and pockets billions for himself. Those billionaires use the money they steal to bribe politicians and hire lobbyists who then write the rules to benefit the billionaires and harm you. Billionaires also hire armies of propagandists to get gullible rubes to vote against their own interests, and support policies that give the billionaires more control over the economy. (Some of the comments here are rantings from the brainwashed minions of Roger Ailes.) This is why capitalism is not compatible with democracy and freedom. It degrades into a plutocracy (or oligarchy of the wealthy) in which the masses serve the needs of the elite few. Workers in the US have steadily increased in their productivity since WWII, while their standard of living has decreased. All of the benefit of that extra productively has been siphoned off to create a parasitic class of billionaires. (Billionaires are not something to be proud of, but rather a symptom of a failed economic system in which profits are distributed according to authority, rather than contribution.) Marx believed that socialism was a transition to communism, but he was wrong about that, and many other things. Communist movements have all quickly degraded into facist dictatorships. Stalin for example executed the communists and hijacked the Russian revolution. Communism is not a realistic system for any group larger than a small tribe. — 76.✗.✗.223

March 26, 2010, 2:19pm 24.21.84.143 stated the following on 2009-10-12 23:05:18 "I wish Americans would become more educated and less slaves to the false idea that everyone can be rich. It is entirely illogical and immoral." IT ISN'T "EVERYONE" CAN BE RICH -- IT IS "ANYONE" CAN BE RICH!! THERE ARE NO GUARANTEES - BUT ALL HAVE A CHANCE TO REACH FOR SOMETHING BETTER, AND A GREATER PERCENTAGE WILL SUCCEED UNDER CAPITALISM THAN UNDER SOCIALISM OR COMMUNISM. EACH OF US MUST TAKE RESPONSIBILITY FOR OUR ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL SITUATION - THERE IS NO FREE LUNCH, IN SPITE OF WHAT IS BEING PREACHED TODAY. SOMEONE HAS TO BE PRODUCTIVE IN ORDER TO GENERATE THE WEALTH TO PROVIDE THE BENEFITS! — 64.✗.✗.90

March 30, 2010, 12:58pm "These ideologies are used in powerplays, much like religion and racism, by those that believe they are more intelligent than everyone and want to feed on the labor of others like Clinton, Pelosi and Reid want."...and Nixon, and Reagan, and Bushes, and Greenspan, and Gingrich, and Limbaugh, Beck, Leiberman, Palin, McCain... — 72.✗.✗.130

December 16, 2009, 10:33am @ 98.219.54.147 who says: Which system do you think offers you a better chance? One where an all-powerful government tells you what to do and when and for how long, or you being able to chose your own path through a free-market system. Except that in a Social Democracy, the PEOPLE are the government -- perhaps you are referring to a Social tyranny, and then I'd agree with you. Since I am the vehicle of my own power in a Social Democracy, and I along with a majority favor, say, government building roads, then that is majority rules. There is no big bad bugaboo government because WE are the government. — 71.✗.✗.106

- Capitalism vs Socialism

- Joe Biden vs Donald Trump - On All Issues

- Liberal vs Conservative

- Left Wing vs Right Wing

- Democrat vs Republican

- Communism vs Fascism

- Communism vs Democracy

Edit or create new comparisons in your area of expertise.

Stay connected

© All rights reserved.

Advertisement

What's the Difference Between Socialism and Communism?

- Share Content on Facebook

- Share Content on LinkedIn

- Share Content on Flipboard

- Share Content on Reddit

- Share Content via Email

The Soviet Union was the world's first communist country, so why was its official name the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR)? Are socialism and communism actually the same thing?

Yes and no, says Norman Markowitz , a history professor at Rutgers University who has taught a course on the history of socialism and communism for the past 40 years.

"' The Communist Manifesto ,' published by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in 1848, became the foundation of both socialism and communism," says Markowitz, but there are clearly differences between authoritarian communist regimes like the Soviet Union and China, and far more democratic forms of socialism practiced in countries like Sweden, Canada and Bolivia.

To understand the differences between socialism and communism, we have to start with their common enemy: capitalism.

Capitalism and the Class Struggle

The rise of socialism, communism as 'revolutionary socialism', from marxism to leninism, socialist and communist countries today.

Marx and Engels viewed the entirety of human history as a " history of class struggles ." In ancient Rome, there were patricians, plebeians and slaves. In feudal societies, there were lords, apprentices and serfs. In the 18th century, political and economic revolutions in England, America and France had done away with feudalism and replaced it with capitalism.

"By the 1820s and 1830s, capitalism had produced a world of progress and poverty," says Markowitz, meaning that the Industrial Revolution and the creation of free-market economies had greatly benefited the wealthy classes, who owned the factories and farms (the "means of production"), while leaving the average worker even worse off than the feudal serf.

Marx and Engels divided the modern world into two classes: the bourgeoisie who owned the means of production, and the proletariat or the working class. Capitalism, with its emphasis on cheap labor, had created an ever-widening gulf between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, a problem that could only be fixed by completely dismantling the politico-economic system that created it.

What's important to point out is that Marx and Engels weren't the first to have these ideas. They were the latest in a long line of economic and political theorists who all identified as socialists.

Socialism as a movement began in the early 19th century with thinkers like Henri de Saint-Simon, Robert Owen and Charles Fourier. Disgusted with the inequalities created by capitalism and competition, early socialists proposed the creation of workers' collectives with shared ownership of property, farms and factories.

"From the 1820s through the 1840s, there were various different socialist movements that attracted workers, farmers and alienated intellectuals," says Markowitz, "and all kinds of plans and programs to establish socialist collectives."

Owen, a wealthy Scottish industrialist, even founded such a community called New Harmony in Indiana in 1825, which eventually failed.

Socialism, both then and now, advocates for cooperation rather than competition, by opposing an unrestricted market economy. Under a socialist system, citizens pay high income taxes in exchange for free access to government-run programs and services. In some socialist models, all industry and means of production are state-owned, while other models allow for private ownership of businesses with public control of certain sectors like health care, energy, education and transportation. The goal of socialism is to create a more egalitarian society.

Marx and Engels were fierce critics of the earlier "utopian" forms of socialism that were "doomed to failure," in their words, because they were based on the naive belief that the class struggle could be resolved through peaceful means.

"Marx and Engels believed that eventually the struggle between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat would create a crisis in which the capitalist system would need to be abolished and replaced with a socialist system," says Markowitz. "It wouldn't be a utopian system, but a system in which the working class have the political power."

"The Communist Manifesto" was a socialist call to arms. In it, Marx and Engels argued that the only way to end the class struggles that had defined history was through a socialist revolution. After the revolution, society would be ruled by a " dictatorship of the proletariat ." Under capitalism, the bourgeoisie called the shots, but a government ruled by the workers would put the workers' interests first and not those of a wealthy elite.

For Marx and Engels, communism was the most advanced form of socialism. They saw the evolution of advanced societies as starting with capitalism, moving to socialism and finally reaching the ultimate goal of communism. Under proletariat rule, the communists would abolish private ownership of land, farms and factories, and hand all control over to the state. Housing, medical care and education would all be free, and every worker would have a job.

In a way, Marx and Engel's vision of a truly communist society was also utopian. They believed that at some point the state itself would cease to exist, and the workers would simply share everything. As Marx famously wrote : "From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs."

"In that higher stage of communism, there would be general equality and general abundance," says Markowitz. "People could do whatever they want without harming others. They would be genuinely free."

But Marx and Engel's version of revolutionary socialism, also known as Marxism, was never really put into practice. Instead, the world's first communist revolution happened in an unlikely place, Tsarist Russia, and its political mastermind was Vladimir Lenin .

Lenin was a Marxist, but he put his own twist on communist theory. Lenin was a champion of the workers, but he wasn't confident that a "dictatorship of the proletariat" would spontaneously form after the revolution. In place of a "dictatorship" elected or appointed by the workers, Lenin preferred a dictatorship of the Communist Party .

Under Leninism, all power was put in the hands of a political elite that controlled all aspects of Soviet economic, cultural and intellectual life with the goal of creating a more equitable socialist society. In reality, Leninism slipped into authoritarianism and totalitarianism with violent crackdowns on dissent or opposition.

The ideas put forth in "The Communist Manifesto" inspired generations of political thinkers and economic theorists. Some of those individuals formed socialist political parties to win power by democratic means, while others, like Lenin and Mao Zedong, launched communist revolutions. The result, today, are countries and governments that identify as either socialist or communist or both!

Scandinavia is home to a cluster of democratic socialist countries. Countries like Norway, Sweden, Finland and Denmark have elected socialist democrat parties into power, and their legislatures have passed laws establishing expansive "welfare states." In a socialist welfare state, citizens pay high taxes, but enjoy generous social services including free education (including college), free health care, retirement pensions, paid parental leave, subsidized housing and more.

"While the traditional liberal model of democracy only emphasizes individual liberty, the social democratic model, according to its proponents, stresses both liberal and egalitarian ideals," wrote John Patrick in " Understanding Democracy, A Hip Pocket Guide ." Critics of democratic socialism, he added, would claim that "positive state action to provide egalitarian social programs requires extensive redistribution of wealth and excessive government regulation of the society and economy." This, in turn, would minimize the principles of individual liberty.

It's important to point out that in democratic socialist countries, private ownership of business and free-market capitalism are also allowed to exist. And while socialist parties are currently in power, they are not one-party governments. Other political parties are allowed to campaign and run for office.

That's not the case in so-called communist countries like China, Cuba and Vietnam, and wasn't true in the former Soviet Union, either. Those nations are one-party regimes where the authority of the Communist Party is unquestioned and the party chooses government officials, not the people. While there is no real democracy in these countries, capitalism has made significant inroads, particularly in China and Vietnam.

Meanwhile, just to keep things confusing, all of the countries that we call "communist" still think of themselves as socialist, just different flavors of socialism.

"China is developing its own model of socialism that's very different from the Soviet Union," says Markowitz. "China's model retains power in the hands of a government controlled by the Communist Party, but it's also created a capitalist sector that's become the second biggest economy in the world over the last 40 years."

The truth, says Markowitz, is that there has never been a truly "communist" country in Marx's sense of the word, just as there has never been a true democracy. "These are ideals that one works toward and struggles to achieve."

Socialism hasn't had much success in American politics since Eugene Debs ran for president in the early 20th century, but there are now four members of the House of Representatives who belong to the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), including Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York and Rashida Tlaib from Michigan. The organization has over 92,000 members in the U.S.

Please copy/paste the following text to properly cite this HowStuffWorks.com article:

Communism Vs. Socialism: Peeling Back the Layers of Collective Thought

This spirited essay breaks down the distinctions between communism and socialism, painting them as distinct yet interconnected ideologies aiming for collective prosperity. Communism is portrayed as a radical vision advocating for a classless society, where everything is shared, inspired by figures like Karl Marx. On the other hand, socialism is depicted as a more measured approach that seeks to refine, rather than overhaul, existing structures, promoting public ownership and democratic governance within the framework of a structured society. The essay acknowledges the tumultuous history and diverse outcomes of these ideologies in practice, emphasizing their complex journey from theory to real-world application. It also addresses the contemporary usage of these terms, encouraging a deeper understanding beyond political rhetoric. The piece invites readers to view communism and socialism not just as political labels but as rich, thought-provoking concepts that challenge us to envision and debate different pathways to social justice and collective well-being.

Also at PapersOwl you can find more free essay examples related to Communism.

How it works

Let’s get real about communism and socialism – two terms that often get tossed around like hot potatoes in political chat rooms and dinner table debates. While they both rock the boat of traditional capitalism and share a vibe of collective good, they’re not just two peas in a pod. They’ve got their own flavors, histories, and recipes for shaking up society.

Communism, the brainchild of big thinkers like Karl Marx, dreams of a world where everyone’s on the same level – no class divides, no private property, just one big collective where everything’s shared.

Sounds pretty out there, right? It’s all about flipping the script on the current system, and historically, it’s had its moment with revolutions that tried to turn this vision into reality, though not without a fair share of bumps (or boulders) along the way.

Now, slide over to socialism. It’s like communism’s more chill cousin. Socialism says, “Hey, let’s take things slow.” It’s not about tossing the state or private property out the window but making sure they play nice for the benefit of everyone. It’s about tweaking the system, adding a dash of democracy here, a pinch of public ownership there, all to cook up a society that’s fair but still keeps its structure.

But let’s not sugarcoat it – the journey from theory to practice for both these ideologies has been a wild ride. From the Soviet Union’s take on communism to the cozy welfare states that have a socialist twist, the world’s seen it all. It’s a mixed bag of results that shows just how tricky it is to take these big ideas and make them work in the real, messy world.

And nowadays, ‘communism’ and ‘socialism’ often get thrown around more like political slurs than actual discussion points. But if you dig into their stories, their struggles, and their aspirations, there’s a whole world of thought there. They’re not just political buzzwords; they’re visions of how we might live together, share the wealth, and build a society that’s got each other’s backs.

So next time you hear ‘communism’ or ‘socialism,’ think beyond the red flags and the Cold War vibes. Think about the people, the ideas, and the endless debates on how to make a world that’s a bit fairer, a bit kinder, and a lot more interesting. Whether you’re all in or skeptical, understanding these ideologies is like adding a new lens to your worldview camera – it’s all about getting the bigger picture.

Cite this page

Communism vs. Socialism: Peeling Back the Layers of Collective Thought. (2024, Jan 26). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/communism-vs-socialism-peeling-back-the-layers-of-collective-thought/

"Communism vs. Socialism: Peeling Back the Layers of Collective Thought." PapersOwl.com , 26 Jan 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/communism-vs-socialism-peeling-back-the-layers-of-collective-thought/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Communism vs. Socialism: Peeling Back the Layers of Collective Thought . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/communism-vs-socialism-peeling-back-the-layers-of-collective-thought/ [Accessed: 19 Apr. 2024]

"Communism vs. Socialism: Peeling Back the Layers of Collective Thought." PapersOwl.com, Jan 26, 2024. Accessed April 19, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/communism-vs-socialism-peeling-back-the-layers-of-collective-thought/

"Communism vs. Socialism: Peeling Back the Layers of Collective Thought," PapersOwl.com , 26-Jan-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/communism-vs-socialism-peeling-back-the-layers-of-collective-thought/. [Accessed: 19-Apr-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Communism vs. Socialism: Peeling Back the Layers of Collective Thought . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/communism-vs-socialism-peeling-back-the-layers-of-collective-thought/ [Accessed: 19-Apr-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, socialism vs communism: a comprehensive guide.

General Education

Socialism vs communism: you probably see these terms pop up in many places, from your social media timeline to the evening news. Many times, people use them interchangeably to talk about politics and economics. But these terms actually mean different things! They may seem similar, but there are actually some key differences between socialism and communism (and other similar forms of government!).

So what do these terms really mean? What are the factual differences between socialism vs communism vs Marxism? How do they compare to other political systems, like fascism and capitalism?

We know: these are tough questions! We’ve done the research to bring you credible answers to these complex questions about socialism vs communism and other political systems. In this article, we’ll give you a detailed guide to socialism vs communism, as well as the following:

- A deep dive into socialism, and a deep dive into communism

- A socialism vs communism chart with side-by-side comparisons

- A brief comparison of fascism vs communism vs socialism vs Marxism vs capitalism

When you’re done reading this article, you’ll understand the differences between socialism and communism, how each system works, and how they compare to other government and political systems.

Socialism vs Communism: A Quick Overview

Socialism generally refers to any social, economic, or political system that is based on public, social ownership of property and the means of production (such as mines, mills, and factories) and democratic control of business. The overarching purpose of socialism is to create more equality by ensuring the public--not private citizens--own the means of production.

In other words, socialism takes the aspects of society that affect everyone and brings them under the control of government, such as utilities, education, and healthcare. But the government doesn’t control everything: socialism also allows for private enterprise and business ownership, too.

Socialism is a flexible philosophy that has many forms that range from democratic socialism to communism that differ based on how much control the government exerts over social and economic systems. But the big takeaway is this: all forms of socialism are based on the common idea that the government— and by extension, the citizens the government represents—should own and regulate the aspects of society that provide for basic human needs.

In contrast, communism is a philosophical, social, political, and economic ideology that ultimately aims to establish a society based on the idea that all property, resources, and goods (aka the means of production) should be owned by the public. These things become communally owned--hence the name commun ism--and are distributed by the government since the government represents the people. In a communist society, private property, profit-based economy, and social classes are eliminated, and each individual is provided for according to their needs.

Just like socialism, there are different communist schools of thought that vary based on how many rights citizens have in relation to the government. But one view they all share is that capitalism and its two-class system (i.e. the working class/proletariat and the ownership class/bourgeoisie) is the root cause of society’s problems and inequalities . As a result, communism calls for an overthrow of capitalism and the social class system through social revolution.

The biggest similarity between socialism vs communism is that they are based on a similar core principle: to give power and control back to the working class people that build and sustain society. But while socialism maintains some form of private enterprise and ownership, communism abolishes that system and transfers social ownership to the government. In that way, communism is a more extreme form of socialism .

We’ll dig into more of the differences between these systems a bit later in the article (we’ve even put together a handy table for you). But first, let’s take a more in-depth look at both socialism and communism.

Socialism believes that a society's means of production--like health and education systems--should be owned by the public, rather than by private individuals.

What Is Socialism?

Below, we’ll go into the specifics of socialism, give you a brief history of the term, and provide some examples of socialist governments around the world.

Socialism: Overview and Definition

Socialism is a social, economic, and political doctrine that calls for public rather than private ownership and control of property and natural resources. Those publicly owned resources are then managed and distributed by the government.

Like we mentioned above, there are different types of socialism, and they differ based on how much the government controls and how much is left to private industry. Some socialist systems will only give government ownership of social institutions that are considered basic human rights. Other socialist systems may eliminate the private sector entirely.

But why does socialism advocate for public ownership of property and goods? As an economic theory for how society should be organized, socialism states that the means of producing wealth should be controlled by the workers in a society, not by the elite or ownership classes. Socialists believe that the money made belongs to workers who make the products.

History of the Term

The contemporary term “socialism” has its origins in the early 19th century, coming from the French word socialisme. The word finds its roots in the Latin sociare, which means to combine or to share. It also has ties to the term societas, which is found in Roman and medieval law and refers to a consensual contract of fellowship between free people. These roots reflect the core philosophy of socialism: that the means of production and its profits should be shared among and controlled by the public.

The term “socialism” or “socialized” is often used by modern political parties and the media to describe political platforms, government policies, politicians, or even entire countries. But at its core, socialism is a type of economic system that is designed to eliminate inequality and improve quality of life by placing power in the hands of society’s workers .

Socialism has been around in some form since classical times, and its meaning has changed some over time. Below, we’ll briefly cover the two most important points in the history of socialism, namely socialism in the Industrial Revolution and in the 20th century.

Socialism in the Industrial Revolution

While socialist ideas date back much further, the earliest use of the term “socialism” used to refer to economic reform can be pinpointed in the 1820s and 1830s.

The modern term “socialism” was originally coined by French theorist Henri de Saint-Simon toward the end of the Industrial Revolution between 1820 and 1840. Saint-Simon and other prominent philosophers were the first to critique the poverty and inequality of the capitalist system that was ushered in by the Industrial Revolution. In response, socialist thinkers advocated the transformation of society into small communities without private property.

As a political movement, modern day socialism started with the revolutionary attitude of 18th century philosophers that advocated for the rights of the working class and pushed for social change.

As socialism rose in popularity throughout the end of the 19th century, movements split into two main groups: a reform movement, which advocated a social democratic form of socialism, and a revolutionary movement, which advocated uprising against existing capitalist economies in favor of communism.

Socialism in the 20th Century

During the 20th century, socialism began to spread throughout the world as socialist parties began winning elections.

For example, take Socialist Party of Argentina, which was established in the 1890s. It was the first mass socialist party in Argentina and Latin America. The British Labour Party--also socialist!--first won seats in Parliament in 1902. And in 1904, the first democratically elected socialist took office as the first Labor Party Prime Minister in Australia. These widespread elections of socialist representatives were the first of the kind on an international scale, bringing socialism into view as the most influential secular movement of the 20th century.

Socialism became more prominent following the international conflicts of World War I . In 1917, the Bolshevik Revolution occurred in Russia, led by philosopher Vladimir Lenin . Lenin and the Bolshevik faction of socialists overthrew the Russian monarchy and installed the first ever constitutionally socialists state, known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic.

Around the world, other socialist parties began to gain importance in their national politics. By the 1920s, communism and socialist democracy had become powerful political ideologies. It was also during this time that the key distinction between socialism and communism was solidified. While socialism allowed for, and even encouraged, a private sector within an economy, communism embraced its anti-capitalist foundations.

Denmark is an example of a country with a socialist government.

Examples of Socialist Governments Today

Today, socialist ideals can be implemented in almost any kind of government, because socialism is not tied to a specific form of government or political ideology. Socialism can be incorporated into democratic, republic , capitalist, and other systems of government as part of an economic system, domestic policy, or a political party’s ideology. In other words, a government doesn’t need to be set up in a special way for it to be “socialist .”

It’s important to recognize that “socialist” can be used to refer to a philosophy, form of government, political party, and economic system. This is why it isn’t necessarily accurate to refer to a country as socialist. In most cases, it’s probably more accurate to call a country’s economy socialist, or to say that a socialist political party is in power in a particular country. Some countries might have socialism heavily embedded in one aspect of their societal structure, but not necessarily in others.

Here are a few countries that incorporate socialism into their governing structure but still allow for private enterprise and ownership:

- Germany

- Iceland

We can look more closely at one country that combines both socialist and capitalist structures: Denmark. This will help you understand what aspects of socialism look like in practice.

Denmark follows the Nordic Model , which refers to the economic and social policies common to the Nordic countries of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden.

Denmark’s version of the Nordic Model fits the description of democratic socialism for two main reasons. First, it supports a comprehensive welfare state where things like healthcare and higher education are owned by the people and run by elected government officials. But Denmark also operates a capitalist, market-based economy that relies on private enterprise.

Denmark’s robust social benefits are funded by taxpayers and administered by the government. Denmark’s social benefits include free education, universal healthcare, and public pension plans for retirees. Additionally, 66 percent of Danish workers belong to a labor union, and in 2014, Denmark was the only nation to receive a perfect score for protecting workers’ rights on the International Trade Union Confederation's Global Rights Index. Because of these policies, Denmark is known for its high standards of living and low income disparity.

At the same time, Denmark has a capitalist economy. Private ownership and free trade--trademarks of capitalist economies--are heavily supported. Denmark offers strong property rights for its citizens and allows companies to do business without overwhelming government oversight.

So Denmark combines socialist policies that promote social equality with capitalist economic systems like those you would find in countries like the United States! The result is that Denmark has a low concentration of top incomes and low levels of inequality. It also ranks high globally for healthy life expectancy, generosity, and freedom from corruption. Denmark is consistently in the top 10 of countries on the World Happiness Report .

Communism believes that all aspects of society should be owned by the public so that everyone is provided for equally.

What Is Communism?

Now let’s take a closer look at communism. Like we mentioned earlier, communism falls under the umbrella of socialism because it also argues that the public should own and control a country’s means of production. Just like socialism, communism believes this philosophy lowers inequality and increases people’s quality of life.

However, communism takes this concept one step further in its belief that capitalist and class systems should be completely rejected in favor of total public ownership. In other words: the public should own everything to ensure a fair distribution of wealth, goods, and services. The government--which represents the public’s interests--manages these institutions, which include everything from schools, to hospitals, to copyrights or trademarks . Doing so eliminates inequality perpetuated by a class system where the workers’ labor builds the wealth of a very few.

To help clarify these differences, we’ll take a deeper dive into communism as an ideology, give you the history of the term, and provide some examples of communist governments today.

Overview of Communism and Definition

Communism is a social, economic, and political doctrine that aims to establish a society based on collective ownership. As an economic theory for how society should be organized, communism states that the socioeconomic order must be structured upon the ideas of common ownership of the means of production and the absence of social classes, money, and the state.

The goal of communism is total equality between citizens, which is maintained by the government. Because the government represents the people, it is able to distribute the country’s collective resources in a way that ensures everyone has equal access to the things they need.

Communists believe that capitalism is the root cause of society’s inequalities , and that it has divided society into two diametrically opposed classes: the ruling class, or the bourgeoisie, and the working class, or the proletariat . According to communism, true equality can only happen when the working class rises up to overthrow the ruling class...and capitalism is abolished.

The contemporary term “communism” is derived from the French communisme which developed out of the Latin roots communis , or “for the community,” and the suffix isme, or “as a state or doctrine . ” Thus, communism can be understood to mean “the state of being of or for the community.”

Because of this broad definition, communism can describe many different social systems , from the state system of entire countries to the organizing ideology of small, informal communities. For instance, some medieval Christian monastic communities shared their land and resources and were considered communist!

Today, the term “communism” or “communist” is often used by political parties and the media to describe economic and political organizations that are Marxist, totalitarian, or authoritarian. While sometimes these descriptions are apt, like in the case of Nazi Germany or Stalinist Russia, the term “communist” can also be used as a misnomer applied to people or ideas that challenge capitalist ideologies. So for example, sometimes concepts like the Affordable Care Act are labeled “communist” not because they are actually communist, but because they advocate for a less capitalist approach to an industry or service.

Now let’s take a closer look at the history of communism. In the next sections, we’ll briefly cover the following important stages in the development of communism:

- Early communism

- Marxist communism

- 20th century communism

Early Communism

The idea of a class-free, egalitarian society first emerged in ancient Greece . The Greek philosopher Plato incorporated communist ideals into The Republic , his famous dialogues on what makes a just society. The Republic describes an ideal society in which the ruling class serves the interests of the whole community.

Many of the earliest communist communities were based on the teachings of the Christian scriptures . Their model of communist living is outlined in the Christian Bible, which describes the early church in Jerusalem's communal ownership of land and possessions.

Communism also popped up in Puritan communities during the 17th century in England. This group, called “the Diggers,” supported the abolition of private ownership of land . Unlike modern forms of communism, which focus on urban and industrial life, communities like the Diggers were concerned with promoting communal ownership and use of land in agrarian and rural societies.

The French Revolution was one of the final major turning points in the development of communism before the 20th century. During this period, the French aristocracy lived lavish lives while the French working class suffered through unemployment, homelessness, and soaring food prices. The working class rose up against the monarchy, advocating for the abolishment of the aristocracy and equal redistribution of wealth among the French people.

Inspired by the revolutionary spirit and successful uprisings of the French people, communist ideas took root across Europe and East Asia in the 19th century and beyond.

Communism vs Socialism vs Marxism

In the 1830s and 1840s, the communist ideas of German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels became popular with socialist thinkers and revolutionaries throughout Europe.

Marx and Engels were deeply disturbed by what they saw as the injustices of a society divided by class. They claimed that the subjugation of the proletariat/working class was inevitable under capitalism because in capitalist societies, the people who own systems of production end up controlling most of the wealth. Marx and Engels argued that under capitalism, the ruling class--made up of people like industry moguls and factory owners--would become richer while the working class struggled to make ends meet. If capitalism were replaced by communism, they maintained, these structural and systemic issues would be solved.

Marx and Engels wrote and distributed The Communist Manifesto in order to advance their vision of a revolutionary socialism that would unseat capitalism. Their purpose in writing the manifesto wasn’t to describe an ideal communist society, but to argue that the collapse of capitalism and uprising of the working classes were inevitable. To them, communism was the next step toward a more equal society.

It’s important to recognize that Karl Marx didn’t create communism. Marxism (this variety of communism) is popular, but it’s not the only type of communism out there. Leninism , Maoism , and anarchist communism are all different communist schools of thought, too.

However, Marx’s take on communism became very popular at the beginning of the 20th century, and many well-known revolutions of that period were rooted in Marx’s communist ideology. Because of this, Marx became one of the most influential proponents of communism during the 20th century, and that legacy still influences many people’s understanding of communism today.

20th Century Communism

After World War I, communism started to spread internationally. Revolutions based on communist thought occurred during this time, and the first communist governments were instituted in Europe and other parts of the world.

For example, Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin led the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 to overthrow the Russian monarchy. Lenin was a major supporter of Marx’s views of socialism and communism, and this perspective shaped his revolutionary ideas and the government he installed in Russia after the revolution.

Lenin believed that communism was the ideal way to run a society. So in 1918, Lenin’s political party--which was now in power--renamed itself the All-Russian Communist Party. This was the beginning of the Soviet Union , the most well-known communist state of the 20th century.

The emergence of the Soviet Union as the world's first communist state led to communism's widespread association with Marxism, Leninism, and the Soviet economic model . Other countries’ communist governments were modeled after the Soviet Union during the mid-20th century. These communist states included Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Poland, Hungary, Albania, and Romania.

The Soviet Union was the premier communist superpower on the global stage for most of the 20th century . Because of the Soviet Union’s influence, communism was increasingly viewed as a threat to capitalism until the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. The ongoing conflict between the Soviet Union and the United States during the Cold War plays a significant role in shaping people’s perceptions of communism today.

China is an example of a modern country that has a (mostly) communist government.

Examples of Communist Governments Today

There are several communist governments in the world today. These countries typically have a communist political party in power, and the government controls all aspects of the economic and political system.

One thing to keep in mind: there’s never really been a purely communist state. All of the communist governments that have existed have not accomplished the elimination of personal property, money, or class systems. This means they’ve never achieved the ultimate goal of communist ideology and, thus, can’t be considered purely communist states.

However, there are countries whose most prominent governing ideologies are communist. Today, communism exists in the following five countries:

- China, or the People’s Republic of China

- Cuba, or Republic of Cuba

- Laos, or Lao People’s Democratic Republic

- Vietnam, or Socialist Republic of Vietnam

- North Korea, or Democratic People’s Republic of Korea

We can look more closely at one country that has a communist government and a socialist market economy: China, or the People’s Republic of China. This will help you visualize what a communist government looks like in action.

In 1949, Mao Zedong took control over China and proclaimed the nation a communist country , calling it the People's Republic of China . China has been called "Red China" ever since due to the Communist Party's control, and the country remains communist today.

But China is not a purely communist country . It has other political parties besides the ruling Communist Party of China (CPC) that aren’t expressly communist. China also holds local, open elections throughout the country. Because of the CPC’s long legacy, though, it rarely faces opposition from other political parties during elections.

Because China’s government is run by a largely unopposed communist party, a significant portion of its economy is government-controlled. However, China has opened up its economy in recent years and transitioned from a socialist economy to a socialist market economy, where private enterprise is allowed but heavily regulated by the government.

Unlike a pure communist state, China’s constitution recognizes private property as of 2004. Privately-owned firms generate a significant percentage of China’s GDP, and investors and entrepreneurs can take profits within parameters set by the state. China’s economy also supports international trade. Today, China is the second largest economy in the world.

Socialism vs Communism Chart: Key Points Comparison

Now that we’ve done a deep dive into the meaning and history of socialism vs communism, let’s condense these philosophies down to their core differences. Check out our Socialism vs Communism chart for a side-by-side comparison of these systems below.

Socialism and communism are just two types of governments. Here's how they stack up to some other well-known government systems.

Socialism vs Other Major Political Systems

You now understand the differences between socialism vs communism, but did you know that these philosophies are often confused with other social and political movements? We’ll briefly clarify the differences between socialism, communism, and three other prominent philosophies: Marxism, fascism, and capitalism.

Let’s start with communism vs socialism vs Marxism. Marxism refers to the communist political and economic theories of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Marxism argues for the dissolution of capitalism--including private ownership, social systems, and money--to eliminate inequality and improve people’s quality of life.

Marxism is a type of communism, but it’s not the only type out there. Communist systems like Leninism, Maoism, and Marxism are slightly different from one another, usually on the basis of how much--or what type--of control government should have over distributing communal property.

Fascism

What about fascism vs communism vs socialism? Fascism is a political ideology that promotes authoritarianism and ultra-nationalism. Fascist states are run by dictators, which are individual people who run the entirety of the government according to their will. Dictators and fascist leaders forcibly suppress opposition and maintain tight control of society and the economy, usually through increased militarization.

Actually, neither communism nor socialism are considered fascist. That’s because fascism is all about giving power to one individual who controls everything, whereas socialism and communism want to distribute power to every citizen through collective ownership.

Having said that, many people mistakenly assume that both socialist and communist governments are always fascist . That’s due in part to two reasons. The first is that the Nazi party in Germany called itself the “National Socialist German Workers' Party.” Unfortunately, that means some people automatically assume all socialism is akin to Nazism, which isn’t true. (In fact, Nazis are in many ways opposed to socialism, which advocates that everyone should be equal regardless of race or class.)

The second reason has to do with the history of communism globally. Many--but not all!--communist governments have been authoritarian, meaning that one appointed leader wields governmental power and makes decisions for the entire nation. This isn’t an inherent characteristic of communism, but the history of authoritarian communist governments means that people sometimes believe that communism and fascism go hand in hand.

Finally , capitalism is an economic system based on private rather than state control of a country's trade and industry for profit. Countries that have a capitalist system can coexist with elements of socialism, but the free market remains mostly unhindered by socialist policies. In other words, the government controls little--if any!--of the country’s economic structures. Instead, it’s up to private enterprise to maintain the means of production.

In most cases, communism is incompatible with capitalism because the ultimate goal of communism is abolishing capitalism. But countries that embrace socialist social ideals can also have capitalist economies. France, Australia, and New Zealand are examples of countries that do this.

What's Next?

If you’re interested in government, don’t miss our article on democracies vs republics. We’ll explain all the key differences to help you understand the ins and outs of these governing systems.

There’s a lot more to learn about how the U.S. government works, too. For instance, did you know that the U.S. government is set up based on a checks and balances system? You can learn more about this balancing mechanism here. If you’re interested in a specific example of how this works, don’t miss our explainer on how the executive branch checks the judicial branch of government.

If you’ve found this article because you’re prepping for your AP Government exam, we have lots more resources for you on our blog. Here’s a huge list of awesome study resources, and our experts can even help you figure out how to answer those pesky FRQs.

Ashley Sufflé Robinson has a Ph.D. in 19th Century English Literature. As a content writer for PrepScholar, Ashley is passionate about giving college-bound students the in-depth information they need to get into the school of their dreams.

Student and Parent Forum

Our new student and parent forum, at ExpertHub.PrepScholar.com , allow you to interact with your peers and the PrepScholar staff. See how other students and parents are navigating high school, college, and the college admissions process. Ask questions; get answers.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Socialism is a rich tradition of political thought and practice, the history of which contains a vast number of views and theories, often differing in many of their conceptual, empirical, and normative commitments. In his 1924 Dictionary of Socialism , Angelo Rappoport canvassed no fewer than forty definitions of socialism, telling his readers in the book’s preface that “there are many mansions in the House of Socialism” (Rappoport 1924: v, 34–41). To take even a relatively restricted subset of socialist thought, Leszek Kołakowski could fill over 1,300 pages in his magisterial survey of Main Currents of Marxism (Kołakowski 1978 [2008]). Our aim is of necessity more modest. In what follows, we are concerned to present the main features of socialism, both as a critique of capitalism, and as a proposal for its replacement. Our focus is predominantly on literature written within a philosophical idiom, focusing in particular on philosophical writing on socialism produced during the past forty-or-so years. Furthermore, our discussion concentrates on the normative contrast between socialism and capitalism as economic systems. Both socialism and capitalism grant workers legal control of their labor power, but socialism, unlike capitalism, requires that the bulk of the means of production workers use to yield goods and services be under the effective control of workers themselves, rather than in the hands of the members of a different, capitalist class under whose direction they must toil. As we will explain below, this contrast has been articulated further in different ways, and socialists have not only made distinctive claims regarding economic organization but also regarding the processes of transformation fulfilling them and the principles and ideals orienting their justification (including, as we will see, certain understandings of freedom, equality, solidarity, and democracy). [ 1 ]

1. Socialism and Capitalism