- Privacy Policy

Home » Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

A case study is a research method that involves an in-depth examination and analysis of a particular phenomenon or case, such as an individual, organization, community, event, or situation.

It is a qualitative research approach that aims to provide a detailed and comprehensive understanding of the case being studied. Case studies typically involve multiple sources of data, including interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts, which are analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory. The findings of a case study are often used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Types of Case Study

Types and Methods of Case Study are as follows:

Single-Case Study

A single-case study is an in-depth analysis of a single case. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand a specific phenomenon in detail.

For Example , A researcher might conduct a single-case study on a particular individual to understand their experiences with a particular health condition or a specific organization to explore their management practices. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a single-case study are often used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Multiple-Case Study

A multiple-case study involves the analysis of several cases that are similar in nature. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to identify similarities and differences between the cases.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a multiple-case study on several companies to explore the factors that contribute to their success or failure. The researcher collects data from each case, compares and contrasts the findings, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as comparative analysis or pattern-matching. The findings of a multiple-case study can be used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Exploratory Case Study

An exploratory case study is used to explore a new or understudied phenomenon. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to generate hypotheses or theories about the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an exploratory case study on a new technology to understand its potential impact on society. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as grounded theory or content analysis. The findings of an exploratory case study can be used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Descriptive Case Study

A descriptive case study is used to describe a particular phenomenon in detail. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to provide a comprehensive account of the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a descriptive case study on a particular community to understand its social and economic characteristics. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a descriptive case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Instrumental Case Study

An instrumental case study is used to understand a particular phenomenon that is instrumental in achieving a particular goal. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand the role of the phenomenon in achieving the goal.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an instrumental case study on a particular policy to understand its impact on achieving a particular goal, such as reducing poverty. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of an instrumental case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Case Study Data Collection Methods

Here are some common data collection methods for case studies:

Interviews involve asking questions to individuals who have knowledge or experience relevant to the case study. Interviews can be structured (where the same questions are asked to all participants) or unstructured (where the interviewer follows up on the responses with further questions). Interviews can be conducted in person, over the phone, or through video conferencing.

Observations

Observations involve watching and recording the behavior and activities of individuals or groups relevant to the case study. Observations can be participant (where the researcher actively participates in the activities) or non-participant (where the researcher observes from a distance). Observations can be recorded using notes, audio or video recordings, or photographs.

Documents can be used as a source of information for case studies. Documents can include reports, memos, emails, letters, and other written materials related to the case study. Documents can be collected from the case study participants or from public sources.

Surveys involve asking a set of questions to a sample of individuals relevant to the case study. Surveys can be administered in person, over the phone, through mail or email, or online. Surveys can be used to gather information on attitudes, opinions, or behaviors related to the case study.

Artifacts are physical objects relevant to the case study. Artifacts can include tools, equipment, products, or other objects that provide insights into the case study phenomenon.

How to conduct Case Study Research

Conducting a case study research involves several steps that need to be followed to ensure the quality and rigor of the study. Here are the steps to conduct case study research:

- Define the research questions: The first step in conducting a case study research is to define the research questions. The research questions should be specific, measurable, and relevant to the case study phenomenon under investigation.

- Select the case: The next step is to select the case or cases to be studied. The case should be relevant to the research questions and should provide rich and diverse data that can be used to answer the research questions.

- Collect data: Data can be collected using various methods, such as interviews, observations, documents, surveys, and artifacts. The data collection method should be selected based on the research questions and the nature of the case study phenomenon.

- Analyze the data: The data collected from the case study should be analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, or grounded theory. The analysis should be guided by the research questions and should aim to provide insights and conclusions relevant to the research questions.

- Draw conclusions: The conclusions drawn from the case study should be based on the data analysis and should be relevant to the research questions. The conclusions should be supported by evidence and should be clearly stated.

- Validate the findings: The findings of the case study should be validated by reviewing the data and the analysis with participants or other experts in the field. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Write the report: The final step is to write the report of the case study research. The report should provide a clear description of the case study phenomenon, the research questions, the data collection methods, the data analysis, the findings, and the conclusions. The report should be written in a clear and concise manner and should follow the guidelines for academic writing.

Examples of Case Study

Here are some examples of case study research:

- The Hawthorne Studies : Conducted between 1924 and 1932, the Hawthorne Studies were a series of case studies conducted by Elton Mayo and his colleagues to examine the impact of work environment on employee productivity. The studies were conducted at the Hawthorne Works plant of the Western Electric Company in Chicago and included interviews, observations, and experiments.

- The Stanford Prison Experiment: Conducted in 1971, the Stanford Prison Experiment was a case study conducted by Philip Zimbardo to examine the psychological effects of power and authority. The study involved simulating a prison environment and assigning participants to the role of guards or prisoners. The study was controversial due to the ethical issues it raised.

- The Challenger Disaster: The Challenger Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion in 1986. The study included interviews, observations, and analysis of data to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

- The Enron Scandal: The Enron Scandal was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Enron Corporation’s bankruptcy in 2001. The study included interviews, analysis of financial data, and review of documents to identify the accounting practices, corporate culture, and ethical issues that led to the company’s downfall.

- The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster : The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the nuclear accident that occurred at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan in 2011. The study included interviews, analysis of data, and review of documents to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

Application of Case Study

Case studies have a wide range of applications across various fields and industries. Here are some examples:

Business and Management

Case studies are widely used in business and management to examine real-life situations and develop problem-solving skills. Case studies can help students and professionals to develop a deep understanding of business concepts, theories, and best practices.

Case studies are used in healthcare to examine patient care, treatment options, and outcomes. Case studies can help healthcare professionals to develop critical thinking skills, diagnose complex medical conditions, and develop effective treatment plans.

Case studies are used in education to examine teaching and learning practices. Case studies can help educators to develop effective teaching strategies, evaluate student progress, and identify areas for improvement.

Social Sciences

Case studies are widely used in social sciences to examine human behavior, social phenomena, and cultural practices. Case studies can help researchers to develop theories, test hypotheses, and gain insights into complex social issues.

Law and Ethics

Case studies are used in law and ethics to examine legal and ethical dilemmas. Case studies can help lawyers, policymakers, and ethical professionals to develop critical thinking skills, analyze complex cases, and make informed decisions.

Purpose of Case Study

The purpose of a case study is to provide a detailed analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. A case study is a qualitative research method that involves the in-depth exploration and analysis of a particular case, which can be an individual, group, organization, event, or community.

The primary purpose of a case study is to generate a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case, including its history, context, and dynamics. Case studies can help researchers to identify and examine the underlying factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and detailed understanding of the case, which can inform future research, practice, or policy.

Case studies can also serve other purposes, including:

- Illustrating a theory or concept: Case studies can be used to illustrate and explain theoretical concepts and frameworks, providing concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Developing hypotheses: Case studies can help to generate hypotheses about the causal relationships between different factors and outcomes, which can be tested through further research.

- Providing insight into complex issues: Case studies can provide insights into complex and multifaceted issues, which may be difficult to understand through other research methods.

- Informing practice or policy: Case studies can be used to inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

Advantages of Case Study Research

There are several advantages of case study research, including:

- In-depth exploration: Case study research allows for a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. This can provide a comprehensive understanding of the case and its dynamics, which may not be possible through other research methods.

- Rich data: Case study research can generate rich and detailed data, including qualitative data such as interviews, observations, and documents. This can provide a nuanced understanding of the case and its complexity.

- Holistic perspective: Case study research allows for a holistic perspective of the case, taking into account the various factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the case.

- Theory development: Case study research can help to develop and refine theories and concepts by providing empirical evidence and concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Practical application: Case study research can inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

- Contextualization: Case study research takes into account the specific context in which the case is situated, which can help to understand how the case is influenced by the social, cultural, and historical factors of its environment.

Limitations of Case Study Research

There are several limitations of case study research, including:

- Limited generalizability : Case studies are typically focused on a single case or a small number of cases, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The unique characteristics of the case may not be applicable to other contexts or populations, which may limit the external validity of the research.

- Biased sampling: Case studies may rely on purposive or convenience sampling, which can introduce bias into the sample selection process. This may limit the representativeness of the sample and the generalizability of the findings.

- Subjectivity: Case studies rely on the interpretation of the researcher, which can introduce subjectivity into the analysis. The researcher’s own biases, assumptions, and perspectives may influence the findings, which may limit the objectivity of the research.

- Limited control: Case studies are typically conducted in naturalistic settings, which limits the control that the researcher has over the environment and the variables being studied. This may limit the ability to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Time-consuming: Case studies can be time-consuming to conduct, as they typically involve a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific case. This may limit the feasibility of conducting multiple case studies or conducting case studies in a timely manner.

- Resource-intensive: Case studies may require significant resources, including time, funding, and expertise. This may limit the ability of researchers to conduct case studies in resource-constrained settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 1: The Basics

- Introduction and overview

- What is qualitative research?

- What is qualitative data?

- Examples of qualitative data

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- Mixed methods

- Qualitative research preparation

- Theoretical perspective

- Theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

Research question

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

Data collection

- Qualitative research methods

- Focus groups

- Observational research

What is a case study?

Applications for case study research, what is a good case study, process of case study design, benefits and limitations of case studies.

- Ethnographical research

- Ethical considerations

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Power dynamics

- Reflexivity

Case studies

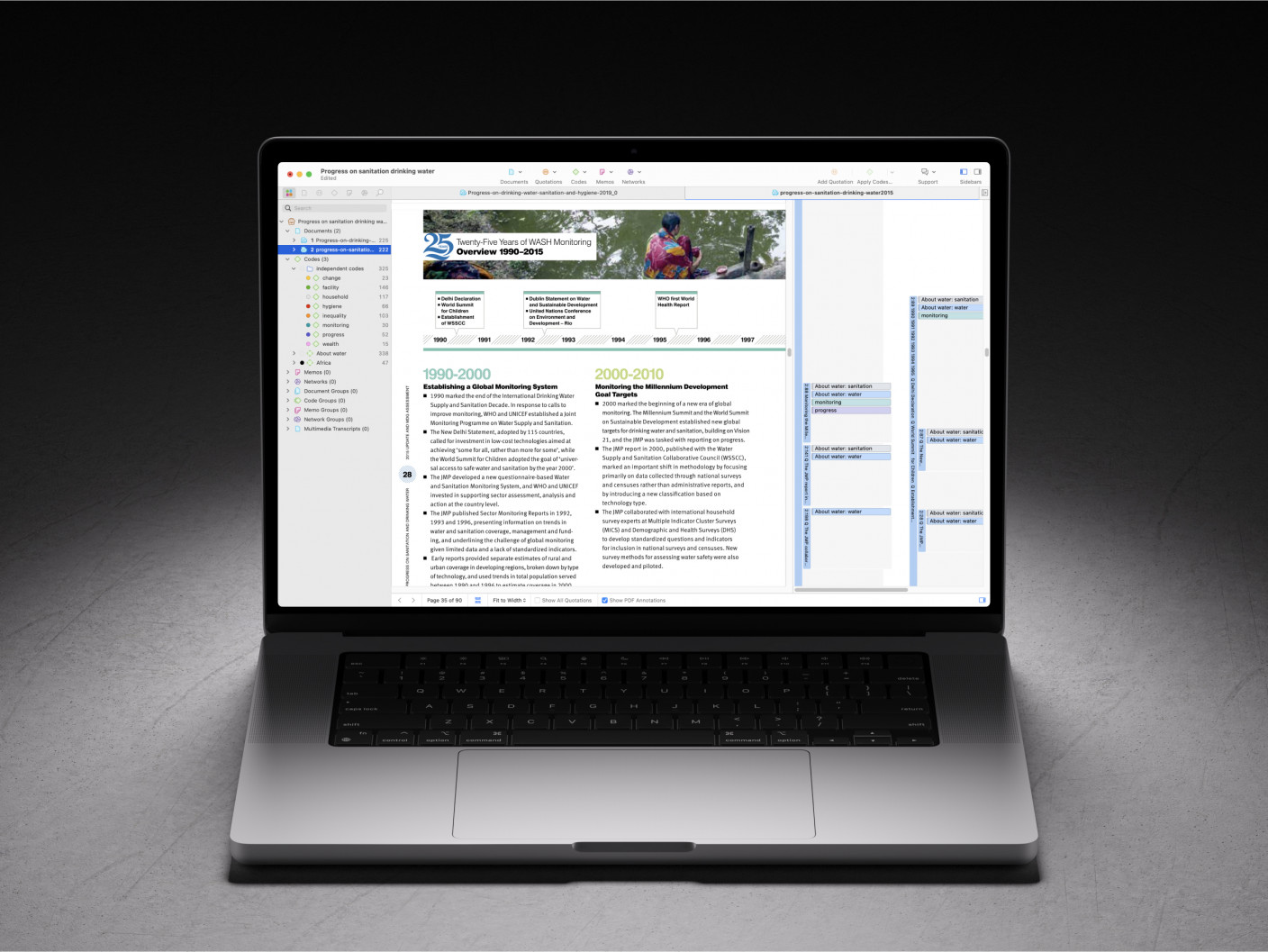

Case studies are essential to qualitative research , offering a lens through which researchers can investigate complex phenomena within their real-life contexts. This chapter explores the concept, purpose, applications, examples, and types of case studies and provides guidance on how to conduct case study research effectively.

Whereas quantitative methods look at phenomena at scale, case study research looks at a concept or phenomenon in considerable detail. While analyzing a single case can help understand one perspective regarding the object of research inquiry, analyzing multiple cases can help obtain a more holistic sense of the topic or issue. Let's provide a basic definition of a case study, then explore its characteristics and role in the qualitative research process.

Definition of a case study

A case study in qualitative research is a strategy of inquiry that involves an in-depth investigation of a phenomenon within its real-world context. It provides researchers with the opportunity to acquire an in-depth understanding of intricate details that might not be as apparent or accessible through other methods of research. The specific case or cases being studied can be a single person, group, or organization – demarcating what constitutes a relevant case worth studying depends on the researcher and their research question .

Among qualitative research methods , a case study relies on multiple sources of evidence, such as documents, artifacts, interviews , or observations , to present a complete and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. The objective is to illuminate the readers' understanding of the phenomenon beyond its abstract statistical or theoretical explanations.

Characteristics of case studies

Case studies typically possess a number of distinct characteristics that set them apart from other research methods. These characteristics include a focus on holistic description and explanation, flexibility in the design and data collection methods, reliance on multiple sources of evidence, and emphasis on the context in which the phenomenon occurs.

Furthermore, case studies can often involve a longitudinal examination of the case, meaning they study the case over a period of time. These characteristics allow case studies to yield comprehensive, in-depth, and richly contextualized insights about the phenomenon of interest.

The role of case studies in research

Case studies hold a unique position in the broader landscape of research methods aimed at theory development. They are instrumental when the primary research interest is to gain an intensive, detailed understanding of a phenomenon in its real-life context.

In addition, case studies can serve different purposes within research - they can be used for exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory purposes, depending on the research question and objectives. This flexibility and depth make case studies a valuable tool in the toolkit of qualitative researchers.

Remember, a well-conducted case study can offer a rich, insightful contribution to both academic and practical knowledge through theory development or theory verification, thus enhancing our understanding of complex phenomena in their real-world contexts.

What is the purpose of a case study?

Case study research aims for a more comprehensive understanding of phenomena, requiring various research methods to gather information for qualitative analysis . Ultimately, a case study can allow the researcher to gain insight into a particular object of inquiry and develop a theoretical framework relevant to the research inquiry.

Why use case studies in qualitative research?

Using case studies as a research strategy depends mainly on the nature of the research question and the researcher's access to the data.

Conducting case study research provides a level of detail and contextual richness that other research methods might not offer. They are beneficial when there's a need to understand complex social phenomena within their natural contexts.

The explanatory, exploratory, and descriptive roles of case studies

Case studies can take on various roles depending on the research objectives. They can be exploratory when the research aims to discover new phenomena or define new research questions; they are descriptive when the objective is to depict a phenomenon within its context in a detailed manner; and they can be explanatory if the goal is to understand specific relationships within the studied context. Thus, the versatility of case studies allows researchers to approach their topic from different angles, offering multiple ways to uncover and interpret the data .

The impact of case studies on knowledge development

Case studies play a significant role in knowledge development across various disciplines. Analysis of cases provides an avenue for researchers to explore phenomena within their context based on the collected data.

This can result in the production of rich, practical insights that can be instrumental in both theory-building and practice. Case studies allow researchers to delve into the intricacies and complexities of real-life situations, uncovering insights that might otherwise remain hidden.

Types of case studies

In qualitative research , a case study is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Depending on the nature of the research question and the specific objectives of the study, researchers might choose to use different types of case studies. These types differ in their focus, methodology, and the level of detail they provide about the phenomenon under investigation.

Understanding these types is crucial for selecting the most appropriate approach for your research project and effectively achieving your research goals. Let's briefly look at the main types of case studies.

Exploratory case studies

Exploratory case studies are typically conducted to develop a theory or framework around an understudied phenomenon. They can also serve as a precursor to a larger-scale research project. Exploratory case studies are useful when a researcher wants to identify the key issues or questions which can spur more extensive study or be used to develop propositions for further research. These case studies are characterized by flexibility, allowing researchers to explore various aspects of a phenomenon as they emerge, which can also form the foundation for subsequent studies.

Descriptive case studies

Descriptive case studies aim to provide a complete and accurate representation of a phenomenon or event within its context. These case studies are often based on an established theoretical framework, which guides how data is collected and analyzed. The researcher is concerned with describing the phenomenon in detail, as it occurs naturally, without trying to influence or manipulate it.

Explanatory case studies

Explanatory case studies are focused on explanation - they seek to clarify how or why certain phenomena occur. Often used in complex, real-life situations, they can be particularly valuable in clarifying causal relationships among concepts and understanding the interplay between different factors within a specific context.

Intrinsic, instrumental, and collective case studies

These three categories of case studies focus on the nature and purpose of the study. An intrinsic case study is conducted when a researcher has an inherent interest in the case itself. Instrumental case studies are employed when the case is used to provide insight into a particular issue or phenomenon. A collective case study, on the other hand, involves studying multiple cases simultaneously to investigate some general phenomena.

Each type of case study serves a different purpose and has its own strengths and challenges. The selection of the type should be guided by the research question and objectives, as well as the context and constraints of the research.

The flexibility, depth, and contextual richness offered by case studies make this approach an excellent research method for various fields of study. They enable researchers to investigate real-world phenomena within their specific contexts, capturing nuances that other research methods might miss. Across numerous fields, case studies provide valuable insights into complex issues.

Critical information systems research

Case studies provide a detailed understanding of the role and impact of information systems in different contexts. They offer a platform to explore how information systems are designed, implemented, and used and how they interact with various social, economic, and political factors. Case studies in this field often focus on examining the intricate relationship between technology, organizational processes, and user behavior, helping to uncover insights that can inform better system design and implementation.

Health research

Health research is another field where case studies are highly valuable. They offer a way to explore patient experiences, healthcare delivery processes, and the impact of various interventions in a real-world context.

Case studies can provide a deep understanding of a patient's journey, giving insights into the intricacies of disease progression, treatment effects, and the psychosocial aspects of health and illness.

Asthma research studies

Specifically within medical research, studies on asthma often employ case studies to explore the individual and environmental factors that influence asthma development, management, and outcomes. A case study can provide rich, detailed data about individual patients' experiences, from the triggers and symptoms they experience to the effectiveness of various management strategies. This can be crucial for developing patient-centered asthma care approaches.

Other fields

Apart from the fields mentioned, case studies are also extensively used in business and management research, education research, and political sciences, among many others. They provide an opportunity to delve into the intricacies of real-world situations, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of various phenomena.

Case studies, with their depth and contextual focus, offer unique insights across these varied fields. They allow researchers to illuminate the complexities of real-life situations, contributing to both theory and practice.

Whatever field you're in, ATLAS.ti puts your data to work for you

Download a free trial of ATLAS.ti to turn your data into insights.

Understanding the key elements of case study design is crucial for conducting rigorous and impactful case study research. A well-structured design guides the researcher through the process, ensuring that the study is methodologically sound and its findings are reliable and valid. The main elements of case study design include the research question , propositions, units of analysis, and the logic linking the data to the propositions.

The research question is the foundation of any research study. A good research question guides the direction of the study and informs the selection of the case, the methods of collecting data, and the analysis techniques. A well-formulated research question in case study research is typically clear, focused, and complex enough to merit further detailed examination of the relevant case(s).

Propositions

Propositions, though not necessary in every case study, provide a direction by stating what we might expect to find in the data collected. They guide how data is collected and analyzed by helping researchers focus on specific aspects of the case. They are particularly important in explanatory case studies, which seek to understand the relationships among concepts within the studied phenomenon.

Units of analysis

The unit of analysis refers to the case, or the main entity or entities that are being analyzed in the study. In case study research, the unit of analysis can be an individual, a group, an organization, a decision, an event, or even a time period. It's crucial to clearly define the unit of analysis, as it shapes the qualitative data analysis process by allowing the researcher to analyze a particular case and synthesize analysis across multiple case studies to draw conclusions.

Argumentation

This refers to the inferential model that allows researchers to draw conclusions from the data. The researcher needs to ensure that there is a clear link between the data, the propositions (if any), and the conclusions drawn. This argumentation is what enables the researcher to make valid and credible inferences about the phenomenon under study.

Understanding and carefully considering these elements in the design phase of a case study can significantly enhance the quality of the research. It can help ensure that the study is methodologically sound and its findings contribute meaningful insights about the case.

Ready to jumpstart your research with ATLAS.ti?

Conceptualize your research project with our intuitive data analysis interface. Download a free trial today.

Conducting a case study involves several steps, from defining the research question and selecting the case to collecting and analyzing data . This section outlines these key stages, providing a practical guide on how to conduct case study research.

Defining the research question

The first step in case study research is defining a clear, focused research question. This question should guide the entire research process, from case selection to analysis. It's crucial to ensure that the research question is suitable for a case study approach. Typically, such questions are exploratory or descriptive in nature and focus on understanding a phenomenon within its real-life context.

Selecting and defining the case

The selection of the case should be based on the research question and the objectives of the study. It involves choosing a unique example or a set of examples that provide rich, in-depth data about the phenomenon under investigation. After selecting the case, it's crucial to define it clearly, setting the boundaries of the case, including the time period and the specific context.

Previous research can help guide the case study design. When considering a case study, an example of a case could be taken from previous case study research and used to define cases in a new research inquiry. Considering recently published examples can help understand how to select and define cases effectively.

Developing a detailed case study protocol

A case study protocol outlines the procedures and general rules to be followed during the case study. This includes the data collection methods to be used, the sources of data, and the procedures for analysis. Having a detailed case study protocol ensures consistency and reliability in the study.

The protocol should also consider how to work with the people involved in the research context to grant the research team access to collecting data. As mentioned in previous sections of this guide, establishing rapport is an essential component of qualitative research as it shapes the overall potential for collecting and analyzing data.

Collecting data

Gathering data in case study research often involves multiple sources of evidence, including documents, archival records, interviews, observations, and physical artifacts. This allows for a comprehensive understanding of the case. The process for gathering data should be systematic and carefully documented to ensure the reliability and validity of the study.

Analyzing and interpreting data

The next step is analyzing the data. This involves organizing the data , categorizing it into themes or patterns , and interpreting these patterns to answer the research question. The analysis might also involve comparing the findings with prior research or theoretical propositions.

Writing the case study report

The final step is writing the case study report . This should provide a detailed description of the case, the data, the analysis process, and the findings. The report should be clear, organized, and carefully written to ensure that the reader can understand the case and the conclusions drawn from it.

Each of these steps is crucial in ensuring that the case study research is rigorous, reliable, and provides valuable insights about the case.

The type, depth, and quality of data in your study can significantly influence the validity and utility of the study. In case study research, data is usually collected from multiple sources to provide a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case. This section will outline the various methods of collecting data used in case study research and discuss considerations for ensuring the quality of the data.

Interviews are a common method of gathering data in case study research. They can provide rich, in-depth data about the perspectives, experiences, and interpretations of the individuals involved in the case. Interviews can be structured , semi-structured , or unstructured , depending on the research question and the degree of flexibility needed.

Observations

Observations involve the researcher observing the case in its natural setting, providing first-hand information about the case and its context. Observations can provide data that might not be revealed in interviews or documents, such as non-verbal cues or contextual information.

Documents and artifacts

Documents and archival records provide a valuable source of data in case study research. They can include reports, letters, memos, meeting minutes, email correspondence, and various public and private documents related to the case.

These records can provide historical context, corroborate evidence from other sources, and offer insights into the case that might not be apparent from interviews or observations.

Physical artifacts refer to any physical evidence related to the case, such as tools, products, or physical environments. These artifacts can provide tangible insights into the case, complementing the data gathered from other sources.

Ensuring the quality of data collection

Determining the quality of data in case study research requires careful planning and execution. It's crucial to ensure that the data is reliable, accurate, and relevant to the research question. This involves selecting appropriate methods of collecting data, properly training interviewers or observers, and systematically recording and storing the data. It also includes considering ethical issues related to collecting and handling data, such as obtaining informed consent and ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of the participants.

Data analysis

Analyzing case study research involves making sense of the rich, detailed data to answer the research question. This process can be challenging due to the volume and complexity of case study data. However, a systematic and rigorous approach to analysis can ensure that the findings are credible and meaningful. This section outlines the main steps and considerations in analyzing data in case study research.

Organizing the data

The first step in the analysis is organizing the data. This involves sorting the data into manageable sections, often according to the data source or the theme. This step can also involve transcribing interviews, digitizing physical artifacts, or organizing observational data.

Categorizing and coding the data

Once the data is organized, the next step is to categorize or code the data. This involves identifying common themes, patterns, or concepts in the data and assigning codes to relevant data segments. Coding can be done manually or with the help of software tools, and in either case, qualitative analysis software can greatly facilitate the entire coding process. Coding helps to reduce the data to a set of themes or categories that can be more easily analyzed.

Identifying patterns and themes

After coding the data, the researcher looks for patterns or themes in the coded data. This involves comparing and contrasting the codes and looking for relationships or patterns among them. The identified patterns and themes should help answer the research question.

Interpreting the data

Once patterns and themes have been identified, the next step is to interpret these findings. This involves explaining what the patterns or themes mean in the context of the research question and the case. This interpretation should be grounded in the data, but it can also involve drawing on theoretical concepts or prior research.

Verification of the data

The last step in the analysis is verification. This involves checking the accuracy and consistency of the analysis process and confirming that the findings are supported by the data. This can involve re-checking the original data, checking the consistency of codes, or seeking feedback from research participants or peers.

Like any research method , case study research has its strengths and limitations. Researchers must be aware of these, as they can influence the design, conduct, and interpretation of the study.

Understanding the strengths and limitations of case study research can also guide researchers in deciding whether this approach is suitable for their research question . This section outlines some of the key strengths and limitations of case study research.

Benefits include the following:

- Rich, detailed data: One of the main strengths of case study research is that it can generate rich, detailed data about the case. This can provide a deep understanding of the case and its context, which can be valuable in exploring complex phenomena.

- Flexibility: Case study research is flexible in terms of design , data collection , and analysis . A sufficient degree of flexibility allows the researcher to adapt the study according to the case and the emerging findings.

- Real-world context: Case study research involves studying the case in its real-world context, which can provide valuable insights into the interplay between the case and its context.

- Multiple sources of evidence: Case study research often involves collecting data from multiple sources , which can enhance the robustness and validity of the findings.

On the other hand, researchers should consider the following limitations:

- Generalizability: A common criticism of case study research is that its findings might not be generalizable to other cases due to the specificity and uniqueness of each case.

- Time and resource intensive: Case study research can be time and resource intensive due to the depth of the investigation and the amount of collected data.

- Complexity of analysis: The rich, detailed data generated in case study research can make analyzing the data challenging.

- Subjectivity: Given the nature of case study research, there may be a higher degree of subjectivity in interpreting the data , so researchers need to reflect on this and transparently convey to audiences how the research was conducted.

Being aware of these strengths and limitations can help researchers design and conduct case study research effectively and interpret and report the findings appropriately.

Ready to analyze your data with ATLAS.ti?

See how our intuitive software can draw key insights from your data with a free trial today.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 30 January 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organisation, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating, and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyse the case.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

Unlike quantitative or experimental research, a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

If you find yourself aiming to simultaneously investigate and solve an issue, consider conducting action research . As its name suggests, action research conducts research and takes action at the same time, and is highly iterative and flexible.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience, or phenomenon.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews, observations, and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data .

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis, with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results , and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyse its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, January 30). Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved 6 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/case-studies/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, correlational research | guide, design & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, descriptive research design | definition, methods & examples.

Research Writing and Analysis

- NVivo Group and Study Sessions

- SPSS This link opens in a new window

- Statistical Analysis Group sessions

- Using Qualtrics

- Dissertation and Data Analysis Group Sessions

- Defense Schedule - Commons Calendar This link opens in a new window

- Research Process Flow Chart

- Research Alignment Chapter 1 This link opens in a new window

- Step 1: Seek Out Evidence

- Step 2: Explain

- Step 3: The Big Picture

- Step 4: Own It

- Step 5: Illustrate

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review This link opens in a new window

- Systematic Reviews & Meta-Analyses

- How to Synthesize and Analyze

- Synthesis and Analysis Practice

- Synthesis and Analysis Group Sessions

- Problem Statement

- Purpose Statement

- Conceptual Framework

- Theoretical Framework

- Quantitative Research Questions

- Qualitative Research Questions

- Trustworthiness of Qualitative Data

- Analysis and Coding Example- Qualitative Data

- Thematic Data Analysis in Qualitative Design

- Dissertation to Journal Article This link opens in a new window

- International Journal of Online Graduate Education (IJOGE) This link opens in a new window

- Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning (JRIT&L) This link opens in a new window

Writing a Case Study

What is a case study?

A Case study is:

- An in-depth research design that primarily uses a qualitative methodology but sometimes includes quantitative methodology.

- Used to examine an identifiable problem confirmed through research.

- Used to investigate an individual, group of people, organization, or event.

- Used to mostly answer "how" and "why" questions.

What are the different types of case studies?

Note: These are the primary case studies. As you continue to research and learn

about case studies you will begin to find a robust list of different types.

Who are your case study participants?

What is triangulation ?

Validity and credibility are an essential part of the case study. Therefore, the researcher should include triangulation to ensure trustworthiness while accurately reflecting what the researcher seeks to investigate.

How to write a Case Study?

When developing a case study, there are different ways you could present the information, but remember to include the five parts for your case study.

Was this resource helpful?

- << Previous: Thematic Data Analysis in Qualitative Design

- Next: Journal Article Reporting Standards (JARS) >>

- Last Updated: May 3, 2024 8:12 AM

- URL: https://resources.nu.edu/researchtools

Case Study vs. Survey

What's the difference.

Case studies and surveys are both research methods used in various fields to gather information and insights. However, they differ in their approach and purpose. A case study involves an in-depth analysis of a specific individual, group, or situation, aiming to understand the complexities and unique aspects of the subject. It often involves collecting qualitative data through interviews, observations, and document analysis. On the other hand, a survey is a structured data collection method that involves gathering information from a larger sample size through standardized questionnaires. Surveys are typically used to collect quantitative data and provide a broader perspective on a particular topic or population. While case studies provide rich and detailed information, surveys offer a more generalizable and statistical overview.

Further Detail

Introduction.

When conducting research, there are various methods available to gather data and analyze it. Two commonly used methods are case study and survey. Both approaches have their own unique attributes and can be valuable in different research contexts. In this article, we will explore the characteristics of case study and survey, highlighting their strengths and limitations.

A case study is an in-depth investigation of a particular individual, group, or phenomenon. It involves collecting detailed information about the subject of study through various sources such as interviews, observations, and document analysis. Case studies are often used in social sciences, psychology, and business research to gain a deep understanding of complex issues.

One of the key attributes of a case study is its ability to provide rich and detailed data. Researchers can gather extensive information about the subject, including their background, experiences, and perspectives. This depth of data allows for a comprehensive analysis and interpretation of the case, providing valuable insights into the phenomenon under investigation.

Furthermore, case studies are particularly useful when studying rare or unique cases. Since case studies focus on specific individuals or groups, they can shed light on situations that are not easily replicated or observed in larger populations. This makes case studies valuable in exploring complex and nuanced phenomena that may not be easily captured through other research methods.

However, it is important to note that case studies have certain limitations. Due to their in-depth nature, case studies are often time-consuming and resource-intensive. Researchers need to invest significant effort in data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Additionally, the findings of a case study may not be easily generalized to larger populations, as the focus is on a specific case rather than a representative sample.

Despite these limitations, case studies offer a unique opportunity to explore complex issues in real-life contexts. They provide a detailed understanding of individual experiences and can generate hypotheses for further research.

A survey is a research method that involves collecting data from a sample of individuals through a structured questionnaire or interview. Surveys are widely used in social sciences, market research, and public opinion studies to gather information about a larger population. They aim to provide a snapshot of people's opinions, attitudes, behaviors, or characteristics.

One of the main advantages of surveys is their ability to collect data from a large number of respondents. By reaching out to a representative sample, researchers can generalize the findings to a larger population. Surveys also allow for efficient data collection, as questionnaires can be distributed electronically or in person, making it easier to gather a wide range of responses in a relatively short period.

Moreover, surveys offer a structured approach to data collection, ensuring consistency in the questions asked and the response options provided. This allows for easy comparison and analysis of the data, making surveys suitable for quantitative research. Surveys can also be conducted anonymously, which can encourage respondents to provide honest and unbiased answers, particularly when sensitive topics are being explored.

However, surveys also have their limitations. One of the challenges is the potential for response bias. Respondents may provide inaccurate or socially desirable answers, leading to biased results. Additionally, surveys often rely on self-reported data, which may be subject to memory recall errors or misinterpretation of questions. Researchers need to carefully design the survey instrument and consider potential biases to ensure the validity and reliability of the data collected.

Furthermore, surveys may not capture the complexity and depth of individual experiences. They provide a snapshot of people's opinions or behaviors at a specific point in time, but may not uncover the underlying reasons or motivations behind those responses. Surveys also rely on predetermined response options, limiting the range of possible answers and potentially overlooking important nuances.

Case studies and surveys are both valuable research methods, each with its own strengths and limitations. Case studies offer in-depth insights into specific cases, providing rich and detailed data. They are particularly useful for exploring complex and unique phenomena. On the other hand, surveys allow for efficient data collection from a large number of respondents, enabling generalization to larger populations. They provide structured and quantifiable data, making them suitable for statistical analysis.

Ultimately, the choice between case study and survey depends on the research objectives, the nature of the research question, and the available resources. Researchers need to carefully consider the attributes of each method and select the most appropriate approach to gather and analyze data effectively.

Comparisons may contain inaccurate information about people, places, or facts. Please report any issues.

Using Systems Thinking for Translating Evidence into Practice: A Case Study of Embedding Shared Decision Making within a Federally Qualified Health Center Network

The following is a mixed-methods case study that examines how Access Community Health Network (ACCESS), a large federally qualified health center located in the Chicago metropolitan area, used a systems approach to incorporate Shared Decision Making into its practice model. Using both qualitative and quantitative methods including a survey of ACCESS staff and providers, as well as interviews with a range of providers and leadership, the study sought to answer the question: How successfully has ACCESS, as a complex primary care system, made Shared Decision Making an integral part of its Patient Centered Medical Home practice model?

With a high degree of consistency across both the survey and interview data, the study concludes that ACCESS has successfully shifted its culture towards Shared Decision Making and, over the course of the past several years, made it a part of its PCMH practice model. At the same time, there are still areas for improvement and ways that ACCESS can further embed SDM within its practice model. Opportunities exist to use this study as a foundation for further exploring the impact of SDM on patients and health outcomes (not a part of this study). Further, the results can be used by other complex health systems as a model for how to successfully integrate and translate best practice or innovation into care models.

Usage metrics

- Decision making

- Open access

- Published: 11 May 2024

Does a perceptual gap lead to actions against digital misinformation? A third-person effect study among medical students

- Zongya Li ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4479-5971 1 &

- Jun Yan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9539-8466 1

BMC Public Health volume 24 , Article number: 1291 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

We are making progress in the fight against health-related misinformation, but mass participation and active engagement are far from adequate. Focusing on pre-professional medical students with above-average medical knowledge, our study examined whether and how third-person perceptions (TPP), which hypothesize that people tend to perceive media messages as having a greater effect on others than on themselves, would motivate their actions against misinformation.

We collected the cross-sectional data through a self-administered paper-and-pencil survey of 1,500 medical students in China during April 2022.

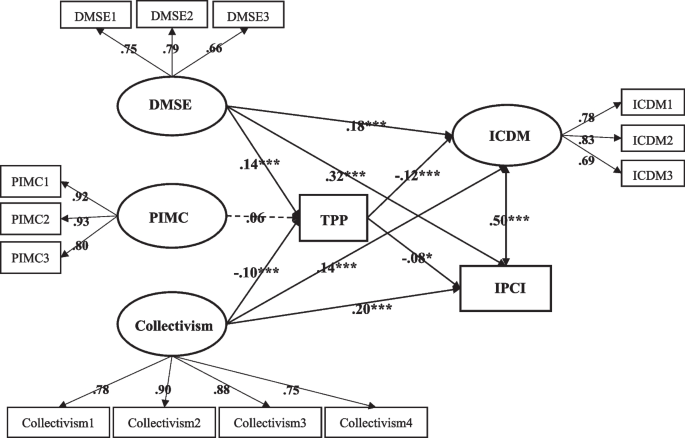

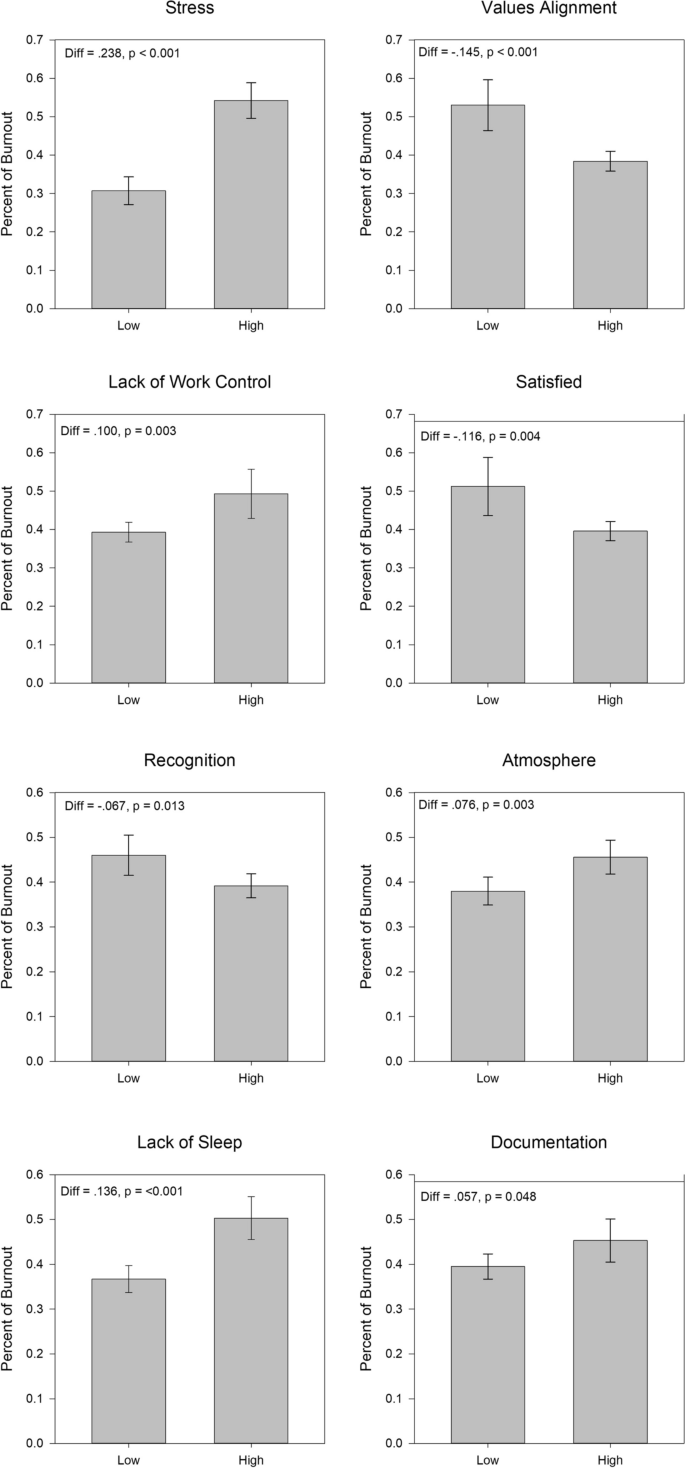

Structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis, showed that TPP was negatively associated with medical students’ actions against digital misinformation, including rebuttal of misinformation and promotion of corrective information. However, self-efficacy and collectivism served as positive predictors of both actions. Additionally, we found professional identification failed to play a significant role in influencing TPP, while digital misinformation self-efficacy was found to broaden the third-person perceptual gap and collectivism tended to reduce the perceptual bias significantly.

Conclusions

Our study contributes both to theory and practice. It extends the third-person effect theory by moving beyond the examination of restrictive actions and toward the exploration of corrective and promotional actions in the context of misinformation., It also lends a new perspective to the current efforts to counter digital misinformation; involving pre-professionals (in this case, medical students) in the fight.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The widespread persistence of misinformation in the social media environment calls for effective strategies to mitigate the threat to our society [ 1 ]. Misinformation has received substantial scholarly attention in recent years [ 2 ], and solution-oriented explorations have long been a focus but the subject remains underexplored [ 3 ].

Health professionals, particularly physicians and nurses, are highly expected to play a role in the fight against misinformation as they serve as the most trusted information sources regarding medical topics [ 4 ]. However, some barriers, such as limitations regarding time and digital skills, greatly hinder their efforts to tackle misinformation on social media [ 5 ].

Medical students (i.e., college students majoring in health/medical science), in contrast to medical faculty, have a greater potential to become the major force in dealing with digital misinformation as they are not only equipped with basic medical knowledge but generally possess greater social media skills than the former generation [ 6 ]. Few studies, to our knowledge, have tried to explore the potential of these pre-professionals in tackling misinformation. Our research thus fills the gap by specifically exploring how these pre-professionals can be motivated to fight against digital health-related misinformation.

The third-person perception (TPP), which states that people tend to perceive media messages as having a greater effect on others than on themselves [ 7 ], has been found to play an important role in influencing individuals’ coping strategies related to misinformation. But empirical exploration from this line of studies has yielded contradictory results. Some studies revealed that individuals who perceived a greater negative influence of misinformation on others than on themselves were more likely to take corrective actions to debunk misinformation [ 8 ]. In contrast, some research found that stronger TPP reduced individuals’ willingness to engage in misinformation correction [ 9 , 10 ]. Such conflicting findings impel us to examine the association between the third-person perception and medical students’ corrective actions in response to misinformation, thus attempting to unveil the underlying mechanisms that promote or inhibit these pre-professionals’ engagement with misinformation.

Researchers have also identified several perceptual factors that motivate individuals’ actions against misinformation, especially efficacy-related concepts (e.g., self-efficacy and health literacy) and normative variables (e.g., subjective norms and perceived responsibility) [ 3 , 8 , 9 ]. However, most studies devote attention to the general population; little is known about whether and how these factors affect medical students’ intentions to deal with misinformation. We recruited Chinese medical students in order to study a social group that is mutually influenced by cultural norms (collectivism in Chinese society) and professional norms. Meanwhile, systematic education and training equip medical students with abundant clinical knowledge and good levels of eHealth literacy [ 5 ], which enable them to have potential efficacy in tackling misinformation. Our study thus aims to examine how medical students’ self-efficacy, cultural norms (i.e., collectivism) and professional norms (i.e., professional identification) impact their actions against misinformation.

Previous research has found self-efficacy to be a reliable moderator of optimistic bias, the tendency for individuals to consider themselves as less likely to experience negative events but more likely to experience positive events as compared to others [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. As TPP is thought to be a product of optimistic bias, accordingly, self-efficacy should have the potential to influence the magnitude of third-person perception [ 14 , 15 ]. Meanwhile, scholars also suggest that the magnitude of TPP is influenced by social distance corollary [ 16 , 17 ]. Simply put, individuals tend to perceive those who are more socially distant from them to be more susceptible to the influence of undesirable media than those who are socially proximal [ 18 , 19 , 20 ]. From a social identity perspective, collectivism and professional identification might moderate the relative distance between oneself and others while the directions of such effects differ [ 21 , 22 ]. For example, collectivists tend to perceive a smaller social distance between self and others as “they are less likely to view themselves as distinct or unique from others” [ 23 ]. In contrast, individuals who are highly identified with their professional community (i.e., medical community) are more likely to perceive a larger social distance between in-group members (including themselves) and out-group members [ 24 ]. In this way, collectivism and professional identification might exert different effects on TPP. On this basis, this study aims to examine whether and how medical students’ perceptions of professional identity, self-efficacy and collectivism influence the magnitude of TPP and in turn influence their actions against misinformation.

Our study builds a model that reflects the theoretical linkages among self-efficacy, collectivism, professional identity, TPP, and actions against misinformation. The model, which clarifies the key antecedents of TPP and examines the mediating role of TPP, contribute to the third-person effect literature and offer practical contributions to countering digital misinformation.

Context of the study

As pre-professionals equipped with specialized knowledge and skills, medical students have been involved in efforts in health communication and promotion during the pandemic. For instance, thousands of medical students have participated in various volunteering activities in the fight against COVID-19, such as case data visualization [ 25 ], psychological counseling [ 26 ], and providing online consultations [ 27 ]. Due to the shortage of medical personnel and the burden of work, some medical schools also encouraged their students to participate in health care assistance in hospitals during the pandemic [ 28 , 29 ].

The flood of COVID-19 related misinformation has posed an additional threat to and burden on public health. We have an opportunity to address this issue and respond to the general public’s call for guidance from the medical community about COVID-19 by engaging medical students as a main force in the fight against coronavirus related misinformation.

Literature review

The third-person effect in the misinformation context.

Originally proposed by Davison [ 7 ], the third-person effect hypothesizes that people tend to perceive a greater effect of mass media on others than on themselves. Specifically, the TPE consists of two key components: the perceptual and the behavioral [ 16 ]. The perceptual component centers on the perceptual gap where individuals tend to perceive that others are more influenced by media messages than themselves. The behavioral component refers to the behavioral outcomes of the self-other perceptual gap in which people act in accordance with such perceptual asymmetry.

According to Perloff [ 30 ], the TPE is contingent upon situations. For instance, one general finding suggests that when media messages are considered socially undesirable, nonbeneficial, or involving risks, the TPE will get amplified [ 16 ]. Misinformation characterized as inaccurate, misleading, and even false, is regarded as undesirable in nature [ 31 ]. Based on this line of reasoning, we anticipate that people will tend to perceive that others would be more influenced by misinformation than themselves.

Recent studies also provide empirical evidence of the TPE in the context of misinformation [ 32 ]. For instance, an online survey of 511 Chinese respondents conducted by Liu and Huang [ 33 ] revealed that individuals would perceive others to be more vulnerable to the negative influence of COVID-19 digital disinformation. An examination of the TPE within a pre-professional group – the medical students–will allow our study to examine the TPE scholarship in a particular population in the context of tackling misinformation.

Why TPE occurs among medical students: a social identity perspective

Of the works that have provided explanations for the TPE, the well-known ones include self-enhancement [ 34 ], attributional bias [ 35 ], self-categorization theory [ 36 ], and the exposure hypothesis [ 19 ]. In this study, we argue for a social identity perspective as being an important explanation for third-person effects of misinformation among medical students [ 36 , 37 ].

The social identity explanation suggests that people define themselves in terms of their group memberships and seek to maintain a positive self-image through favoring the members of their own groups over members of an outgroup, which is also known as downward comparison [ 38 , 39 ]. In intergroup settings, the tendency to evaluate their ingroups more positively than the outgroups will lead to an ingroup bias [ 40 ]. Such an ingroup bias is typically described as a trigger for the third-person effect as individuals consider themselves and their group members superior and less vulnerable to undesirable media messages than are others and outgroup members [ 20 ].

In the context of our study, medical students highly identified with the medical community tend to maintain a positive social identity through an intergroup comparison that favors the ingroup and derogates the outgroup (i.e., the general public). It is likely that medical students consider themselves belonging to the medical community and thus are more knowledgeable and smarter than the general public in health-related topics, leading them to perceive the general public as more vulnerable to health-related misinformation than themselves. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1: As medical students’ identification with the medical community increases, the TPP concerning digital misinformation will become larger.

What influences the magnitude of TPP

Previous studies have demonstrated that the magnitude of the third-person perception is influenced by a host of factors including efficacy beliefs [ 3 ] and cultural differences in self-construal [ 22 , 23 ]. Self-construal is defined as “a constellation of thoughts, feelings, and actions concerning the relationship of the self to others, and the self as distinct from others” [ 41 ]. Markus and Kitayama (1991) identified two dimensions of self-construal: Independent and interdependent. Generally, collectivists hold an interdependent view of the self that emphasizes harmony, relatedness, and places importance on belonging, whereas individualists tend to have an independent view of the self and thus view themselves as distinct and unique from others [ 42 ]. Accordingly, cultural values such as collectivism-individualism should also play a role in shaping third-person perception due to the adjustment that people make of the self-other social identity distance [ 22 ].

Set in a Chinese context aiming to explore the potential of individual-level approaches to deal with misinformation, this study examines whether collectivism (the prevailing cultural value in China) and self-efficacy (an important determinant of ones’ behavioral intentions) would affect the magnitude of TPP concerning misinformation and how such impact in turn would influence their actions against misinformation.

The impact of self-efficacy on TPP

Bandura [ 43 ] refers to self-efficacy as one’s perceived capability to perform a desired action required to overcome barriers or manage challenging situations. He also suggests understanding self-efficacy as “a differentiated set of self-beliefs linked to distinct realms of functioning” [ 44 ]. That is to say, self-efficacy should be specifically conceptualized and operationalized in accordance with specific contexts, activities, and tasks [ 45 ]. In the context of digital misinformation, this study defines self-efficacy as one’s belief in his/her abilities to identify and verify misinformation within an affordance-bounded social media environment [ 3 ].

Previous studies have found self-efficacy to be a reliable moderator of biased optimism, which indicates that the more efficacious individuals consider themselves, the greater biased optimism will be invoked [ 12 , 23 , 46 ]. Even if self-efficacy deals only with one’s assessment of self in performing a task, it can still create the other-self perceptual gap; individuals who perceive a higher self-efficacy tend to believe that they are more capable of controlling a stressful or challenging situation [ 12 , 14 ]. As such, they are likely to consider themselves less vulnerable to negative events than are others [ 23 ]. That is, individuals with higher levels of self-efficacy tend to underestimate the impact of harmful messages on themselves, thereby widening the other-self perceptual gap.

In the context of fake news, which is closely related to misinformation, scholars have confirmed that fake news efficacy (i.e., a belief in one’s capability to evaluate fake news [ 3 ]) may lead to a larger third-person perception. Based upon previous research evidence, we thus propose the following hypothesis:

H2: As medical students’ digital misinformation self-efficacy increases, the TPP concerning digital misinformation will become larger.

The influence of collectivism on TPP

Originally conceptualized as a societal-level construct [ 47 ], collectivism reflects a culture that highlights the importance of collective goals over individual goals, defines the self in relation to the group, and places great emphasis on conformity, harmony and interdependence [ 48 ]. Some scholars propose to also examine cultural values at the individual level as culture is embedded within every individual and could vary significantly among individuals, further exerting effects on their perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors [ 49 ]. Corresponding to the construct at the macro-cultural level, micro-psychometric collectivism which reflects personality tendencies is characterized by an interdependent view of the self, a strong sense of other-orientation, and a great concern for the public good [ 50 ].

A few prior studies have indicated that collectivism might influence the magnitude of TPP. For instance, Lee and Tamborini [ 23 ] found that collectivism had a significant negative effect on the magnitude of TPP concerning Internet pornography. Such an impact can be understood in terms of biased optimism and social distance. Collectivists tend to view themselves as an integral part of a greater social whole and consider themselves less differentiated from others [ 51 ]. Collectivism thus would mitigate the third-person perception due to a smaller perceived social distance between individuals and other social members and a lower level of comparative optimism [ 22 , 23 ]. Based on this line of reasoning, we thus propose the following hypothesis:

H3: As medical students’ collectivism increases, the TPP concerning digital misinformation will become smaller.

Behavioral consequences of TPE in the misinformation context

The behavioral consequences trigged by TPE have been classified into three categories: restrictive actions refer to support for censorship or regulation of socially undesirable content such as pornography or violence on television [ 52 ]; corrective action is a specific type of behavior where people seek to voice their own opinions and correct the perceived harmful or ambiguous messages [ 53 ]; promotional actions target at media content with desirable influence, such as advocating for public service announcements [ 24 ]. In a word, restriction, correction and promotion are potential behavioral outcomes of TPE concerning messages with varying valence of social desirability [ 16 ].

Restrictive action as an outcome of third-person perceptual bias (i.e., the perceptual component of TPE positing that people tend to perceive media messages to have a greater impact on others than on themselves) has received substantial scholarly attention in past decades; scholars thus suggest that TPE scholarship to go beyond this tradition and move toward the exploration of corrective and promotional behaviors [ 16 , 24 ]. Moreover, individual-level corrective and promotional actions deserve more investigation specifically in the context of countering misinformation, as efforts from networked citizens have been documented as an important supplement beyond institutional regulations (e.g., drafting policy initiatives to counter misinformation) and platform-based measures (e.g., improving platform algorithms for detecting misinformation) [ 8 ].

In this study, corrective action specifically refers to individuals’ reactive behaviors that seek to rectify misinformation; these include such actions as debunking online misinformation by commenting, flagging, or reporting it [ 3 , 54 ]. Promotional action involves advancing correct information online, including in response to misinformation that has already been disseminated to the public [ 55 ].

The impact of TPP on corrective and promotional actions

Either paternalism theory [ 56 ] or the protective motivation theory [ 57 ] can act as an explanatory framework for behavioral outcomes triggered by third-person perception. According to these theories, people act upon TPP as they think themselves to know better and feel obligated to protect those who are more vulnerable to negative media influence [ 58 ]. That is, corrective and promotional actions as behavioral consequences of TPP might be driven by a protective concern for others and a positive sense of themselves.

To date, several empirical studies across contexts have examined the link between TPP and corrective actions. Koo et al. [ 8 ], for instance, found TPP was not only positively related to respondents’ willingness to correct misinformation propagated by others, but also was positively associated with their self-correction. Other studies suggest that TPP motivates individuals to engage in both online and offline corrective political participation [ 59 ], give a thumbs down to a biased story [ 60 ], and implement corrective behaviors concerning “problematic” TV reality shows [ 16 ]. Based on previous research evidence, we thus propose the following hypothesis:

H4: Medical students with higher degrees of TPP will report greater intentions to correct digital misinformation.

Compared to correction, promotional behavior has received less attention in the TPE research. Promotion commonly occurs in a situation where harmful messages have already been disseminated to the public and others appear to have been influenced by these messages, and it serves as a remedial action to amplify messages with positive influence which may in turn mitigate the detrimental effects of harmful messages [ 16 ].

Within this line of studies, however, empirical studies provide mixed findings. Wei and Golan [ 24 ] found a positive association between TPP of desirable political ads and promotional social media activism such as posting or linking the ad on their social media accounts. Sun et al. [ 16 ] found a negative association between TPP regarding clarity and community-connection public service announcements (PSAs) and promotion behaviors such as advocating for airing more PSAs in TV shows.

As promotional action is still underexplored in the TPE research, and existing evidence for the link between TPP and promotion is indeed mixed, we thus propose an exploratory research question:

RQ1: What is the relationship between TPP and medical students’ intentions to promote corrective information?

The impact of self-efficacy and collectivism on actions against misinformation