- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

ChangeManagement →

No results found in working knowledge.

- Were any results found in one of the other content buckets on the left?

- Try removing some search filters.

- Use different search filters.

JavaScript seems to be disabled in your browser. For the best experience on our site, be sure to turn on Javascript in your browser.

Hello! You are viewing this site in ${language} language. Is this correct?

Explore the Levels of Change Management

9 Successful Change Management Examples For Inspiration

Updated: February 9, 2024

Published: January 3, 2024

Welcome to our guide on change management examples, pivotal for steering through today's dynamic business terrain. Immerse yourself in the transformative power of change management, a tool for resilience, growth, innovation, and employee morale enhancement.

This guide equips you with strategies to promote an innovative, adaptable work environment and boost employee morale for lasting organizational success.

Uncover diverse types of change management with Prosci's established methodology and explore real-world examples that illustrate these principles in action.

What is Change Management?

Change management is a strategy for guiding an organization and its people through change. It goes beyond top-down orders, involving employees at all levels. This people-focused approach encourages everyone to participate actively, helping them adapt and use changes in their everyday work.

Effective change management aligns closely with a company's culture, values, and beliefs.

When change fits well with these cultural aspects, it feels more natural and is easier for employees to adopt. This contributes to smoother transitions and leads to more successful and lasting organizational changes.

Why is Change Management Important?

Change management is pivotal in guiding organizations through transitions, ensuring impactful and long-lasting results.

For example, a $28B electronic components and services company with 18,000 employees realized the importance of enhancing its processes. They knew to adopt more streamlined, efficient approaches, known as Lean initiatives .

However, they encountered challenges because they needed a more structured method for effectively managing the human aspects of these changes.

The company formed a specialized group focused on change to address their challenges and initiate key projects. These projects aligned with their culture of innovation and precision, which helped ensure that the changes were well-received and effectively implemented within the organization.

Matching change management to an organization's unique style and structure contributes to more effective transformations and strengthens the business for future challenges.

What Are the Main Types of Change Management?

Discover Prosci's change management models: from individual application and organizational strategies to enterprise-wide integration and effective portfolio management, all are vital for transformative success.

Individual change management

At Prosci, we understand that change begins with the individual.

The Prosci ADKAR ® Model ( Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability and Reinforcement ) is expertly designed to equip change leaders with tools and strategies to engage your team.

This model is a framework that will guide and support you in confidently navigating and adapting to new changes.

Organizational change management

In organizational change management , we focus on the core elements of your company to fully understand and address each aspect of the change.

Our approach involves creating tailored strategies and detailed plans that benefit you and manage you to manage challenges effectively, which include:

- Clear communication

- Strong leadership support

- Personalized coaching

- Practical training

Our strategies are specifically aimed at meeting the diverse needs within your organization, ensuring a smooth and well-supported transition for everyone involved.

Enterprise change management capability

At the enterprise level, change management becomes an embedded practice, a core competency woven throughout the organization.

When you implement change capabilities:

- Employees know what to ask during change to reach success

- Leaders and managers have the training and skills to guide their teams during change

- Organizations consistently apply change management to initiatives

- Organizations embed change management in roles, structures, processes, projects and leadership competencies

It's a tactical effort to integrate change management into the very DNA of an organization—nurturing a culture that's ready and able to adapt to any change.

Change portfolio management

While distinct from project-level change management, managing a change portfolio is vital for an organization to stay flexible and responsive.

9 Dynamic Change Management Success Stories to Revolutionize Your Business

Prosci case studies reveal how diverse organizations spanning different sectors address and manage change. These cases illustrate how change management can provide transformative solutions from healthcare to finance:

1. Hospital system

A major healthcare organization implemented an extensive enterprise resource planning (ERP) system and adapted to healthcare reform. This case study highlights overcoming significant challenges through strategic change management:

Industry: Healthcare Revenue: $3.7 billion Employees: 24,000 Facilities: 11 hospitals

Major changes:

- Implemented a new ERP system across all hospitals

- Prepared for healthcare reform

Challenges:

- Managing significant, disruptive changes

- Difficulty in gaining buy-in for change management

- Align with culture: Strategically implemented change management to support staff, reflecting the hospital's core value of caring for people

- Focus on a key initiative: Applied change management in the electronic health record system implementation

- Integrate with existing competencies: Recognized change leadership as crucial at various leadership levels

This example shows that when change management matches a healthcare organization's values, it can lead to successful and smooth transitions.

2. Transportation department

A state government transportation department leveraged change management to effectively manage business process improvements amid funding and population challenges. This highlights the value of comprehensive change management in a public sector setting:

Industry: State Government Transportation Revenue: $1.3 billion Employees: 3,000 Challenges:

- Reduced funding

- Growing population

- Increasing transportation needs

Initiative:

- Major business process improvement

Hurdles encountered:

- Change fatigue

- Need for widespread employee adoption

- Focus on internal growth

- Implemented change management in process improvement

This department's experience teaches us the vital role of change management in successfully navigating government projects with multiple challenges.

3. Pharmaceuticals

A global pharmaceutical company navigated post-merger integration challenges. Using a proactive change management approach, they addressed resistance and streamlined operations in a competitive industry:

Industry: Pharma (Global Biopharmaceutical Company) Revenue: $6 billion Number of employees: 5,000

Recent activities: Experienced significant merger and acquisition activity

- Encountered resistance post-implementation of SAP (Systems, Applications and Products in Data Processing)

- They found themselves operating in a purely reactive mode

- Align with your culture: In this Lean Six Sigma-focused environment, where measurement is paramount, the ADKAR Model's metrics were utilized as the foundational entry point for initiating change management processes.

This company's journey highlights the need for flexible and responsive change management.

4. Home fixtures

A home fixtures manufacturing company’s response to the recession offers valuable insights on effectively managing change. They focused on aligning change management with their disciplined culture, emphasizing operational efficiency:

Industry: Home Fixtures Manufacturing Revenue: $600 million Number of employees: 3,000

Context: Facing the lingering effects of the recession

Necessity: Need to introduce substantial changes for more efficient operations

Challenge: Change management was considered a low priority within the company

- Align with your culture: The company's culture, characterized by discipline in projects and processes, ensured that change management was implemented systematically and disciplined.

This company’s experience during the recession proves that aligning change with company culture is key to overcoming tough times.

5. Web services

A web services software company transformed its culture and workspace. They integrated change management into their IT strategy to overcome resistance and foster innovation:

Industry : Web Services Software Revenue : $3.3 billion Number of employees : 10,000

Initiatives : Cultural transformation; applying an unassigned seating model

Challenges : Resistance in IT project management

- Focus on a key initiative: Applied change management in workspace transformation

- Go where the energy is: Establishing a change management practice within its IT department, developing self-service change management tools, and forming thoughtful partnerships

- I ntegrate with existing competencies: "Leading change" was essential to the organization's newly developed leadership competency model.

This case demonstrates the importance of weaving change management into the fabric of tech companies, especially for cultural shifts.

6. Security systems

A high-tech security company effectively managed a major restructuring. They created a change network that shifted change management from HR to business processes:

Industry : High-Tech (Security Systems) Revenue : $10 billion Number of employees: 57,000

Major changes : Company separation; division into three segments

Challenge : No unified change management approach

- Formed a network of leaders from transformation projects

- Go where the energy is: Shifted change management from HR to business processes

- Integrate with existing competencies: Included principles of change management in the training curriculum for the project management boot camp.

- Treat growing your capability like a change: Executive roadshow launch to gain support for enterprise-wide change management

This company’s innovative approach to restructuring shows h ow reimagining change management can lead to successful outcomes.

7. Clothing store

A major clothing retailer’s journey to unify its brand model. They overcame siloed change management through collaborative efforts and a community-driven approach:

Industry : Retail (Clothing Store) Revenue : $16 billion Number of employees : 141,000

Major change initiative : Strategic unification of the brand operating model

Historical challenge : Traditional management of change in siloes

- Build a change network : This retailer established a community of practice for change management, involving representatives from autonomous units to foster consensus on change initiatives.

The story of this retailer illustrates how collaborative efforts in change management can unify and strengthen a brand in the retail world.

A major Canadian bank initiative to standardize change management across its organization. They established a Center of Excellence and tailored communities of practice for effective change:

Industry : Financial Services (Canadian Bank) Revenue : $38 billion Number of employees : 78,000

Current state : Absence of enterprise-wide change management standards

Challenge :

- Employees, contractors, and consultants using individual methods for change management

- Reliance on personal knowledge and experience to deploy change management strategies

- Build a change network: The bank established a Center of Excellence and created federated communities of practice within each business unit, aiming to localize and tailor change management efforts.

This bank’s journey in standardizing change management offers valuable insights for large organizations looking to streamline their processes.

9. Municipality

You can learn from a Canadian municipality’s significant shift to enhance client satisfaction. They integrated change management across all levels to achieve profound organizational change and improved public service:

Industry : Municipal Government (Canadian Municipality) Revenue : $1.9 billion Number of employees : 3,000

New mandate:

- Implementing a new deliberate vision focusing on each individual’s role in driving client satisfaction

Nature of shift :

- A fundamental change within the public institution

Scope of impact :

- It affected all levels, from leadership to front-line staff

Solution :

- Treat growing your capability like a change: Change leaders promoted awareness and cultivated a desire to adopt change management as a standard enterprise-wide practice.

The municipality's strategy shows us how effective change management can significantly improve public services and organizational efficiency.

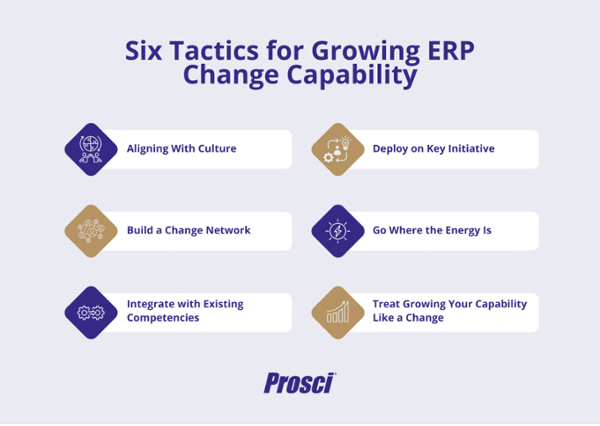

6 Tactics for Growing Enterprise Change Management Capability

Prosci's exploration with 10 industry leaders uncovered six primary tactics for enterprise change growth , demonstrating a "universal theme, unique application" approach.

This framework goes beyond standard procedures, focusing on developing a deep understanding and skill in managing change. It offers transformative tactics, guiding organizations towards excelling in adapting to change. Here, we uncover these transformative tactics, guiding organizations toward mastery of change.

1. Align with Your culture

Organizational culture profoundly influences how change management should be deployed.

Recognizing whether your organization leans towards traditional practices or innovative approaches is vital. This understanding isn't just about alignment; it's an opportunity to enhance and sometimes shift your cultural environment.

When effectively combined with an organization's unique culture, change management can greatly enhance key initiatives. This leads to widespread benefits beyond individual projects and promotes overall growth and development within the organization.

Embrace this as a fundamental tool to strengthen and transform your company's cultural fabric.

2. Focus on key initiatives

In the early phase of developing change management capabilities, selecting noticeable projects with executive backing is important.

This helps demonstrate the real-world impact of change management, making it easier for employees and leadership to understand its benefits. This strategy helps build support and maintain the momentum of change management initiatives within your organization.

Focus on capturing and sharing these successes to encourage buy-in further and underscore the importance of change management in achieving organizational goals.

3. Build a change network

Building change capability isn't just about a few advocates but creating a network of change champions across your organization.

This network, essential in spreading the message and benefits of change management, varies in composition but is universally crucial. It could include departmental practitioners, business unit leaders, or a mix of roles working together to enhance awareness, credibility, and a shared purpose.

Our Best Practices in Change Management study shows that 45% of organizations leverage such networks. These groups boost the effectiveness of change management and keep it moving forward.

4. Go where the energy is

To build change capabilities throughout an organization effectively, the focus should be on matching the organization's current readiness rather than just pushing new methods.

Identify and focus on parts of your organization that are ready for change. Align your change initiatives with these sectors. Involve senior leaders and those enthusiastic about change to naturally generate demand for these transformations.

Showcasing successful initiatives encourages a collaborative culture of change, making it an organic part of your organization's growth.

5. Integrate with existing competencies

Change management is a vital skill across various organizational roles.

Integrating it into competency models and job profiles is increasingly common, yet often lacks the necessary training and tools.

When change management skills expand beyond the experts, they become an integral part of the organization's culture—nurturing a solid foundation of effective change leadership.

This approach embeds change management deeper within the company and cultivates leaders who can support and sustain this essential practice.

6. Treat growing your capability like a change

Growing change capability is a transformative journey for your business and your employees. It demands a structured, strategic approach beyond telling your network that change is coming.

Applying the ADKAR Model universally and focusing on your organization's unique needs is pivotal. It's about building awareness, sparking a desire for change across the enterprise, and equipping employees with the knowledge and skills for effective, lasting change.

Treating capability-building like a change ensures that change management becomes a core part of your organization's fabric, benefitting every team member.

These six tactics are powerful tools for enhancing your organization's ability to adapt and remain resilient in a rapidly changing business environment.

Comprehensive Insights From Change Management Examples

These diverse change management examples provide field-tested savvy and offer a window into how varied organizations successfully manage change.

Case studies , from healthcare reform to innovative corporate restructuring, exemplify how aligning with organizational culture, building strong change networks, and focusing on tactical initiatives can significantly impact change management outcomes.

This guide, enriched with real-world applications, enhances understanding and execution of effective change management, setting a benchmark for future transformations.

To learn more about partnering with Prosci for your next change initiative, discover Prosci's Advisory services and enterprise training options and consider practitioner certification .

Founded in 1994, Prosci is a global leader in change management. We enable organizations around the world to achieve change outcomes and grow change capability through change management solutions based on holistic, research-based, easy-to-use tools, methodologies and services.

See all posts from Prosci

You Might Also Like

Enterprise - 8 MINS

What Is Change Management in Healthcare?

20 Change Management Questions Employees Ask and How To Answer Them

Subscribe here.

Change Management

Whether balancing budgets, reorganizing an agency, or implementing social programs, public sector leaders frequently encounter the complexity of change. The teaching cases in this section allow students to discuss outcomes and engage in problem solving in situations where protagonists wish to enact change or must guide their colleagues or constituents through change that is already occurring.

Charting a Course for Boston: Organizing for Change

Publication Date: March 5, 2024

Boston Mayor-elect Michelle Wu was elected on the promise of systemic change. Four days after her November 2021 victory—and just eleven days before taking office—she considered how to get started delivering on her sweeping agenda. Wu...

Mayor Curtatone’s Culture of Curiosity: Building Data Capabilities at Somerville City Hall Epilogue

Publication Date: February 21, 2024

This epilogue accompanies HKS Case 2255.0. A practitioner guide, HKS Case 2255.4, accompanies this case. For sixteen years, longer than any mayor in the city’s history, Mayor Joseph Curtatone has led his hometown of Somerville,...

Mayor Curtatone’s Culture of Curiosity: Building Data Capabilities at Somerville City Hall Practitioner Guide

This practitioner guide accompanies HKS Case 2255.0. An epilogue, HKS Case 2255.1, follows this case. For sixteen years, longer than any mayor in the city’s history, Mayor Joseph Curtatone has led his hometown of Somerville,...

Mayoral Transitions: How Three Mayors Stepped into the Role, in Their Own Words

Publication Date: February 29, 2024

New mayors face distinct challenges as they assume office. In these vignettes depicting three types of mayoral transitions, explore how new leaders can make the most of their first one hundred days by asserting their authority and...

Mayor Curtatone’s Culture of Curiosity: Building Data Capabilities at Somerville City Hall

For sixteen years, longer than any mayor in the city’s history, Mayor Joseph Curtatone has led his hometown of Somerville, Massachusetts. The case begins in January 2020 when the mayor is looking ahead at his recently won,...

Confronting Constraints: Shashi Verma & Transport for London Tackle a Tough Contract Sequel

Publication Date: December 19. 2023

This sequel accompanies HKS Case 2275.0, "Conflicting Constraints: Shashi Verma &Transport for London Tackle a Tough Contract." The case introduces Shashi Verma (MPP 97) in 2006, soon after he has received a plum appointment: Director...

Confronting Constraints: Shashi Verma & Transport for London Tackle a Tough Contract

The case introduces Shashi Verma (MPP 97) in 2006, soon after he has received a plum appointment: Director of Fares and Ticketing for London's super agency, Transport for London. The centerpiece of the agency's ticketing operation was the Oyster...

Shoring Up Child Protection in Massachusetts: Commissioner Spears & the Push to Go Fast

Publication Date: July 13, 2023

In January 2015, when incoming Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker chose Linda Spears as his new Commissioner of the Department of Children and Families, he was looking for a reformer. Following the grizzly death of a child under DCF...

Evelyn Diop

Publication Date: May 30, 2023

Evelyn is a seasoned nonprofit fundraising professional with roots in the corporate world, who thrives when faced with a strategic challenge. While she had been successfully leading change as a chief development officer (CDO) at...

Confronting the Unequal Toll of Highway Expansion: Oni Blair, LINK Houston, & the Texas I-45 Debate (A)

Publication Date: April 6, 2023

In this political strategy case, Oni K. Blair, newly appointed executive director of a Houston nonprofit advocating for more equitable transportation resources, faces a challenge: how to persuade a Texas state agency to substantially...

Confronting the Unequal Toll of Highway Expansion: Oni Blair, LINK Houston, & the Texas I-45 Debate (B)

Architect, Pilot, Scale, Improve: A Framework and Toolkit for Policy Implementation

Publication Date: May 12, 2021

Successful implementation is essential for achieving policymakers’ goals and must be considered during both design and delivery. The mission of this monograph is to provide you with a framework and set of tools to achieve success. The...

Related Expertise: Organizational Culture , Business Strategy , Change Management

Five Case Studies of Transformation Excellence

November 03, 2014 By Lars Fæste , Jim Hemerling , Perry Keenan , and Martin Reeves

In a business environment characterized by greater volatility and more frequent disruptions, companies face a clear imperative: they must transform or fall behind. Yet most transformation efforts are highly complex initiatives that take years to implement. As a result, most fall short of their intended targets—in value, timing, or both. Based on client experience, The Boston Consulting Group has developed an approach to transformation that flips the odds in a company’s favor. What does that look like in the real world? Here are five company examples that show successful transformations, across a range of industries and locations.

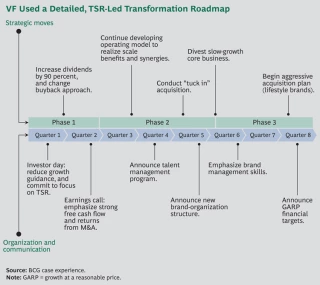

VF’s Growth Transformation Creates Strong Value for Investors

Value creation is a powerful lens for identifying the initiatives that will have the greatest impact on a company’s transformation agenda and for understanding the potential value of the overall program for shareholders.

VF offers a compelling example of a company using a sharp focus on value creation to chart its transformation course. In the early 2000s, VF was a good company with strong management but limited organic growth. Its “jeanswear” and intimate-apparel businesses, although responsible for 80 percent of the company’s revenues, were mature, low-gross-margin segments. And the company’s cost-cutting initiatives were delivering diminishing returns. VF’s top line was essentially flat, at about $5 billion in annual revenues, with an unclear path to future growth. VF’s value creation had been driven by cost discipline and manufacturing efficiency, yet, to the frustration of management, VF had a lower valuation multiple than most of its peers.

With BCG’s help, VF assessed its options and identified key levers to drive stronger and more-sustainable value creation. The result was a multiyear transformation comprising four components:

- A Strong Commitment to Value Creation as the Company’s Focus. Initially, VF cut back its growth guidance to signal to investors that it would not pursue growth opportunities at the expense of profitability. And as a sign of management’s commitment to balanced value creation, the company increased its dividend by 90 percent.

- Relentless Cost Management. VF built on its long-known operational excellence to develop an operating model focused on leveraging scale and synergies across its businesses through initiatives in sourcing, supply chain processes, and offshoring.

- A Major Transformation of the Portfolio. To help fund its journey, VF divested product lines worth about $1 billion in revenues, including its namesake intimate-apparel business. It used those resources to acquire nearly $2 billion worth of higher-growth, higher-margin brands, such as Vans, Nautica, and Reef. Overall, this shifted the balance of its portfolio from 70 percent low-growth heritage brands to 65 percent higher-growth lifestyle brands.

- The Creation of a High-Performance Culture. VF has created an ownership mind-set in its management ranks. More than 200 managers across all key businesses and regions received training in the underlying principles of value creation, and the performance of every brand and business is assessed in terms of its value contribution. In addition, VF strengthened its management bench through a dedicated talent-management program and selective high-profile hires. (For an illustration of VF’s transformation roadmap, see the exhibit.)

The results of VF’s TSR-led transformation are apparent. 1 1 For a detailed description of the VF journey, see the 2013 Value Creators Report, Unlocking New Sources of Value Creation , BCG report, September 2013. Notes: 1 For a detailed description of the VF journey, see the 2013 Value Creators Report, Unlocking New Sources of Value Creation , BCG report, September 2013. The company’s revenues have grown from $7 billion in 2008 to more than $11 billion in 2013 (and revenues are projected to top $17 billion by 2017). At the same time, profitability has improved substantially, highlighted by a gross margin of 48 percent as of mid-2014. The company’s stock price quadrupled from $15 per share in 2005 to more than $65 per share in September 2014, while paying about 2 percent a year in dividends. As a result, the company has ranked in the top quintile of the S&P 500 in terms of TSR over the past ten years.

A Consumer-Packaged-Goods Company Uses Several Levers to Fund Its Transformation Journey

A leading consumer-packaged-goods (CPG) player was struggling to respond to challenging market dynamics, particularly in the value-based segments and at the price points where it was strongest. The near- and medium-term forecasts looked even worse, with likely contractions in sales volume and potentially even in revenues. A comprehensive transformation effort was needed.

To fund the journey, the company looked at several cost-reduction initiatives, including logistics. Previously, the company had worked with a large number of logistics providers, causing it to miss out on scale efficiencies.

To improve, it bundled all transportation spending, across the entire network (both inbound to production facilities and out-bound to its various distribution channels), and opened it to bidding through a request-for-proposal process. As a result, the company was able to save 10 percent on logistics in the first 12 months—a very fast gain for what is essentially a commodity service.

Similarly, the company addressed its marketing-agency spending. A benchmark analysis revealed that the company had been paying rates well above the market average and getting fewer hours per full-time equivalent each year than the market standard. By getting both rates and hours in line, the company managed to save more than 10 percent on its agency spending—and those savings were immediately reinvested to enable the launch of what became a highly successful brand.

Next, the company pivoted to growth mode in order to win in the medium term. The measure with the biggest impact was pricing. The company operates in a category that is highly segmented across product lines and highly localized. Products that sell well in one region often do poorly in a neighboring state. Accordingly, it sought to de-average its pricing approach across locations, brands, and pack sizes, driving a 2 percent increase in EBIT.

Similarly, it analyzed trade promotion effectiveness by gathering and compiling data on the roughly 150,000 promotions that the company had run across channels, locations, brands, and pack sizes. The result was a 2 terabyte database tracking the historical performance of all promotions.

Using that information, the company could make smarter decisions about which promotions should be scrapped, which should be tweaked, and which should merit a greater push. The result was another 2 percent increase in EBIT. Critically, this was a clear capability that the company built up internally, with the objective of continually strengthening its trade-promotion performance over time, and that has continued to pay annual dividends.

Finally, the company launched a significant initiative in targeted distribution. Before the transformation, the company’s distributors made decisions regarding product stocking in independent retail locations that were largely intuitive. To improve its distribution, the company leveraged big data to analyze historical sales performance for segments, brands, and individual SKUs within a roughly ten-mile radius of that retail location. On the basis of that analysis, the company was able to identify the five SKUs likely to sell best that were currently not in a particular store. The company put this tool on a mobile platform and is in the process of rolling it out to the distributor base. (Currently, approximately 60 percent of distributors, representing about 80 percent of sales volume, are rolling it out.) Without any changes to the product lineup, that measure has driven a 4 percent jump in gross sales.

Throughout the process, management had a strong change-management effort in place. For example, senior leaders communicated the goals of the transformation to employees through town hall meetings. Cognizant of how stressful transformations can be for employees—particularly during the early efforts to fund the journey, which often emphasize cost reductions—the company aggressively talked about how those savings were being reinvested into the business to drive growth (for example, investments into the most effective trade promotions and the brands that showed the greatest sales-growth potential).

In the aggregate, the transformation led to a much stronger EBIT performance, with increases of nearly $100 million in fiscal 2013 and far more anticipated in 2014 and 2015. The company’s premium products now make up a much bigger part of the portfolio. And the company is better positioned to compete in its market.

A Leading Bank Uses a Lean Approach to Transform Its Target Operating Model

A leading bank in Europe is in the process of a multiyear transformation of its operating model. Prior to this effort, a benchmarking analysis found that the bank was lagging behind its peers in several aspects. Branch employees handled fewer customers and sold fewer new products, and back-office processing times for new products were slow. Customer feedback was poor, and rework rates were high, especially at the interface between the front and back offices. Activities that could have been managed centrally were handled at local levels, increasing complexity and cost. Harmonization across borders—albeit a challenge given that the bank operates in many countries—was limited. However, the benchmark also highlighted many strengths that provided a basis for further improvement, such as common platforms and efficient product-administration processes.

To address the gaps, the company set the design principles for a target operating model for its operations and launched a lean program to get there. Using an end-to-end process approach, all the bank’s activities were broken down into roughly 250 processes, covering everything that a customer could potentially experience. Each process was then optimized from end to end using lean tools. This approach breaks down silos and increases collaboration and transparency across both functions and organization layers.

Employees from different functions took an active role in the process improvements, participating in employee workshops in which they analyzed processes from the perspective of the customer. For a mortgage, the process was broken down into discrete steps, from the moment the customer walks into a branch or goes to the company website, until the house has changed owners. In the front office, the system was improved to strengthen management, including clear performance targets, preparation of branch managers for coaching roles, and training in root-cause problem solving. This new way of working and approaching problems has directly boosted both productivity and morale.

The bank is making sizable gains in performance as the program rolls through the organization. For example, front-office processing time for a mortgage has decreased by 33 percent and the bank can get a final answer to customers 36 percent faster. The call centers had a significant increase in first-call resolution. Even more important, customer satisfaction scores are increasing, and rework rates have been halved. For each process the bank revamps, it achieves a consistent 15 to 25 percent increase in productivity.

And the bank isn’t done yet. It is focusing on permanently embedding a change mind-set into the organization so that continuous improvement becomes the norm. This change capability will be essential as the bank continues on its transformation journey.

A German Health Insurer Transforms Itself to Better Serve Customers

Barmer GEK, Germany’s largest public health insurer, has a successful history spanning 130 years and has been named one of the top 100 brands in Germany. When its new CEO, Dr. Christoph Straub, took office in 2011, he quickly realized the need for action despite the company’s relatively good financial health. The company was still dealing with the postmerger integration of Barmer and GEK in 2010 and needed to adapt to a fast-changing and increasingly competitive market. It was losing ground to competitors in both market share and key financial benchmarks. Barmer GEK was suffering from overhead structures that kept it from delivering market-leading customer service and being cost efficient, even as competitors were improving their service offerings in a market where prices are fixed. Facing this fundamental challenge, Barmer GEK decided to launch a major transformation effort.

The goal of the transformation was to fundamentally improve the customer experience, with customer satisfaction as a benchmark of success. At the same time, Barmer GEK needed to improve its cost position and make tough choices to align its operations to better meet customer needs. As part of the first step in the transformation, the company launched a delayering program that streamlined management layers, leading to significant savings and notable side benefits including enhanced accountability, better decision making, and an increased customer focus. Delayering laid the path to win in the medium term through fundamental changes to the company’s business and operating model in order to set up the company for long-term success.

The company launched ambitious efforts to change the way things were traditionally done:

- A Better Client-Service Model. Barmer GEK is reducing the number of its branches by 50 percent, while transitioning to larger and more attractive service centers throughout Germany. More than 90 percent of customers will still be able to reach a service center within 20 minutes. To reach rural areas, mobile branches that can visit homes were created.

- Improved Customer Access. Because Barmer GEK wanted to make it easier for customers to access the company, it invested significantly in online services and full-service call centers. This led to a direct reduction in the number of customers who need to visit branches while maintaining high levels of customer satisfaction.

- Organization Simplification. A pillar of Barmer GEK’s transformation is the centralization and specialization of claim processing. By moving from 80 regional hubs to 40 specialized processing centers, the company is now using specialized administrators—who are more effective and efficient than under the old staffing model—and increased sharing of best practices.

Although Barmer GEK has strategically reduced its workforce in some areas—through proven concepts such as specialization and centralization of core processes—it has invested heavily in areas that are aligned with delivering value to the customer, increasing the number of customer-facing employees across the board. These changes have made Barmer GEK competitive on cost, with expected annual savings exceeding €300 million, as the company continues on its journey to deliver exceptional value to customers. Beyond being described in the German press as a “bold move,” the transformation has laid the groundwork for the successful future of the company.

Nokia’s Leader-Driven Transformation Reinvents the Company (Again)

We all remember Nokia as the company that once dominated the mobile-phone industry but subsequently had to exit that business. What is easily forgotten is that Nokia has radically and successfully reinvented itself several times in its 150-year history. This makes Nokia a prime example of a “serial transformer.”

In 2014, Nokia embarked on perhaps the most radical transformation in its history. During that year, Nokia had to make a radical choice: continue massively investing in its mobile-device business (its largest) or reinvent itself. The device business had been moving toward a difficult stalemate, generating dissatisfactory results and requiring increasing amounts of capital, which Nokia no longer had. At the same time, the company was in a 50-50 joint venture with Siemens—called Nokia Siemens Networks (NSN)—that sold networking equipment. NSN had been undergoing a massive turnaround and cost-reduction program, steadily improving its results.

When Microsoft expressed interest in taking over Nokia’s device business, Nokia chairman Risto Siilasmaa took the initiative. Over the course of six months, he and the executive team evaluated several alternatives and shaped a deal that would radically change Nokia’s trajectory: selling the mobile business to Microsoft. In parallel, Nokia CFO Timo Ihamuotila orchestrated another deal to buy out Siemens from the NSN joint venture, giving Nokia 100 percent control over the unit and forming the cash-generating core of the new Nokia. These deals have proved essential for Nokia to fund the journey. They were well-timed, well-executed moves at the right terms.

Right after these radical announcements, Nokia embarked on a strategy-led design period to win in the medium term with new people and a new organization, with Risto Siilasmaa as chairman and interim CEO. Nokia set up a new portfolio strategy, corporate structure, capital structure, robust business plans, and management team with president and CEO Rajeev Suri in charge. Nokia focused on delivering excellent operational results across its portfolio of three businesses while planning its next move: a leading position in technologies for a world in which everyone and everything will be connected.

Nokia’s share price has steadily climbed. Its enterprise value has grown 12-fold since bottoming out in July 2012. The company has returned billions of dollars of cash to its shareholders and is once again the most valuable company in Finland. The next few years will demonstrate how this chapter in Nokia’s 150-year history of serial transformation will again reinvent the company.

Managing Director & Senior Partner

San Francisco - Bay Area

Managing Director & Senior Partner, Chairman of the BCG Henderson Institute

ABOUT BOSTON CONSULTING GROUP

Boston Consulting Group partners with leaders in business and society to tackle their most important challenges and capture their greatest opportunities. BCG was the pioneer in business strategy when it was founded in 1963. Today, we work closely with clients to embrace a transformational approach aimed at benefiting all stakeholders—empowering organizations to grow, build sustainable competitive advantage, and drive positive societal impact.

Our diverse, global teams bring deep industry and functional expertise and a range of perspectives that question the status quo and spark change. BCG delivers solutions through leading-edge management consulting, technology and design, and corporate and digital ventures. We work in a uniquely collaborative model across the firm and throughout all levels of the client organization, fueled by the goal of helping our clients thrive and enabling them to make the world a better place.

© Boston Consulting Group 2024. All rights reserved.

For information or permission to reprint, please contact BCG at [email protected] . To find the latest BCG content and register to receive e-alerts on this topic or others, please visit bcg.com . Follow Boston Consulting Group on Facebook and X (formerly Twitter) .

Subscribe to our Business Transformation E-Alert.

Purdue Polytechnic Institute

Global mobile menu.

- Departments

- Statewide Locations

Managing Change in Uncertain Times: A Case Study

Change management, defined as the methods and processes by which a company effects and adapts to change, has long been vital to the functioning of successful organizations. As John C. Maxwell said , “change is inevitable, growth is optional.” All organizations undergo changes during their lifespans, but not all organizations are able to effectively respond to change or harness it for success.

This fact was made painfully apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic. After businesses were forced to shut down in-person operations, many suffered catastrophic losses. The airline industry, travel and leisure industry, oil and gas industry, and restaurant industry were among the hardest hit . Thousands of businesses were forced to close for good, and thousands more suffered through significant profit loss, layoffs and downsizing. Still, some businesses made vital adaptations that carried them through the worst of the pandemic. Many restaurants, for example, shifted from traditional, in-person service and poured resources into curbside, takeout and delivery services, using technology to communicate with their customers and remain up and running. These adaptations built on services that the restaurants already offered, making the changes easier to implement and accept.

A Case Study in Change: Delta Airlines

Unlike restaurants, airlines did not have much existing infrastructure to carry them through a global pandemic. Airlines profit based on the tickets they book, and if nobody is willing to fly, airlines can’t just pivot to a “take-out” travel option. After the pandemic hit, airlines were faced with a crucial ultimatum: find an innovative solution or suffer catastrophic losses. Delta Airlines, one of the oldest and largest airlines in the country, decided to tackle the change head-on and immediately started working on a change management plan.

Delta structured changes to its operations around what would make customers more comfortable and ultimately found that customers were willing to pay for some extra peace of mind. Implementing the change was made easier by quick and effective communication across all levels of operation. Flight attendants, gate staffers and corporate communications professionals were given the tools they needed to communicate the company’s safety plan to prospective passengers and execute the new seating rules. As the immediate changes took effect and began yielding results, Delta worked on making the changes more efficient and seamless, refining its process every step of the way.

The Science of Change Management

Delta’s quick and effective response to a major change in business operations helped usher it through the worst of the pandemic without suffering bigger losses. Innovative research on best practices in change management is poised to help other businesses do the same. According to the Change Management Review , using technological and organizational tools to manage “the human side of change” is particularly important. Consider, many businesses were forced to move their operations online after the start of COVID-19, and this change affected employees most of all. The businesses who fared best after moving online were the ones who assisted their employees in adapting to the change by providing opportunities for virtual team building, socialization, and mental wellness checkups, for instance. By considering the effects of change on their employees, these businesses took a proactive approach to getting their teams through a daunting and sudden transition.

David Michels and Kevin Murphy, two industry experts who research change management, have helped quantify what exactly makes some organizations excel at handling change. According to their study , there are nine organizational elements that contribute to an organization’s ability to manage change:

- Purpose and direction – the qualities that help organizations lead change.

- Connection, capacity, and choreography – the qualities that help organizations accelerate change.

- And scaling, development, action, and flexibility – the qualities that help organizations organize change.

Michels and Murphy also developed categories identifying the challenges many organizations face when dealing with change. They determined that organizations struggling with change were either:

- In search of focus, meaning they struggle to lead change, identify ambitions and map agendas.

- Stuck and skeptical, meaning they struggle to move beyond small-level changes and avoid big decision making.

- Aligned but constrained, meaning they struggle with change because of organizational barriers.

- And struggling to keep up, meaning they struggle with organizational fatigue and burnout.

This kind of change management research gives organizations the opportunity to critically evaluate their responses to change and map effective plans for dealing with change in the future. Even without the pandemic factor, being able to change and grow is of primary importance in a world of fast-paced technological advancement and global communication. Change management specialists are in high demand in every industry, with 12% projected job growth (U.S Bureau of Labor Statistics) and a median salary of $128,992 (Salary.com).

Purdue Prepares Project Managers to Master Change

Purdue University’s 100% online Master of Science in IT Project Management prepares students for project management careers in the fast-growing information technology field. Students develop mastery of project management processes and procedures using program materials included in the Body of Knowledge developed by the Project Management Institute (PMI®). Courses are taught by industry experts in high-demand specialization areas such as change management, risk management and security management.

Since the program is entirely online, working professionals can arrange their plan of study around their busy schedules and take classes from anywhere. The program is specifically tailored to industry-experienced go-getters who want to break into the IT field or advance their careers by developing project management expertise.

Professionals who want to grow their expertise without committing to a master’s degree can choose to complete a four-course graduate certificate in Managing Information Technology Projects. The credits from the graduate certificate can be applied towards the master’s degree if a student chooses to pursue the master’s after completing the certificate.

Learn more about the program and graduate certificate on the course’s website .

About the author.

Rachel (RM) Barton

Thank you! We will contact you in the near future.

Thanks for your interest, we will get back to you shortly

- Change Management Tools

- Organizational Development

- Organizational Change

Home » Change Management » Amazon: The Ultimate Change Management Case Study

Amazon: The Ultimate Change Management Case Study

Amazon’s innovations have helped it become extremely successful, making it an excellent change management case study.

Since it was formed, Amazon has innovated across countless areas and industries, including:

- Warehouse automation

- The web server industry

- Streaming video and on-demand media

- Electronic books

Considering that Amazon started as an online bookstore, these accomplishments are quite impressive.

Examining Amazon as a change management highlights a few important business lessons:

- Innovation fuels success, especially in today’s digital economy

- Speed is the ultimate weapon

- Those who resist organizational change can easily get left behind

Below, we’ll examine some of Amazon’s changes … and hopefully discover a few reasons why it has become so successful.

Let’s get started.

Below are 10 ways Amazon has changed its business, transforming itself far beyond a mere online bookseller.

In no particular order…

1. Amazon Web Services

When Amazon Web Services (AWS) started out, most developers didn’t take it seriously.

A decade later, it was the go-to cloud server company in the world.

In fact, Bezos has even said that AWS was the biggest part of the company.

Since it has more capacity than its nearest 14 competitors combined, this shouldn’t come as a surprise.

2. Whole Foods

After acquiring Whole Foods , Amazon began making changes to the grocery store chain.

A few of these include:

- Adding Amazon products to the shelves

- Integrating Whole Foods and Amazon Prime

- Internal restructuring

Other programs include food delivery from Whole Foods, rewards for customers using Amazon credit cards, and discounts for Prime members.

3. Delivery

Amazon has drastically innovated product delivery.

For instance, customers with Prime memberships can enjoy free two-day delivery.

In certain cities , Prime members can also get free same-day or one-day delivery.

And with its drone delivery program on the horizon, customers may be able to receive orders in 30 minutes or less .

4. Warehouse Automation

Amazon warehouses have undergone major technological transformations.

Currently, Amazon warehouses uses robots to collect and transport many of its products.

In coming years, though, even more of the company’s 200,000+ warehouse workers could be replaced by robots .

In 2016 alone, it increased robot workers by 50% .

5. TV and Prime Video

Another innovation of the former bookseller is its foray into TV, movies, and video.

Amazon began by selling videos and DVDs. Now it streams, rents, and sells digital copies of videos.

On top of that, the company has joined YouTube, Netflix, and other tech giants by producing its own movies and TV shows.

6. Amazon in Other Countries

Change managers would also be interested in how Amazon adapts itself to other countries’ economies.

In India, for instance, Amazon has been forced to adopt unique measures.

These include:

- Using mom-n-pop stores as delivery locations

- Hiring bicycle or motorcycle couriers for last-mile deliveries

- Creating mobile tea carts that serve tea and teach business owners about e-commerce

These types of innovations are necessary to succeed in other countries.

Failure to adapt to these changes often proves disastrous, which is a major reason why Google China failed .

7. Amazon Go

Amazon isn’t just an online retailer … it has now opened up physical grocery stores.

However, as with all of its business ventures, it aims to disrupt, transform, and dominate retail grocery stores.

In this case, Amazon wants to create grocery stores with zero clerks .

Amazon Go is a venture that promises no checkout lines, no hassle, and ultra-convenience.

8. Kindle and E-Books

Everyone knows that Kindle has been one of Amazon’s biggest innovations.

This product has single-handedly revolutionized the book publishing industry.

For better or for worse, Kindle has changed the way books are read, sold, and distributed.

Some estimates have placed Kindle e-book revenue at over half a billion dollars per year.

9. Affiliate Marketing

Early on in Amazon’s career, it opened its doors to online sales associates.

Members of Amazon Associates can earn revenue by sending web visitors to the sales giant.

According to Amazon, there are over 900,000 global members – all working to promote the company’s products and online presence.

10. Blue Origin

Technically speaking, Blue Origin is a different company from Amazon.

However, it’s worth noting that Amazon and Jeff Bezos can hardly be separated.

Without the famous founder’s extreme drive and vision, Amazon wouldn’t be what it is today.

And without his willingness to innovate, he never would have founded Blue Origin.

Like Elon Musk’s SpaceX, Blue Origin literally aims for the stars.

Its mission and goal – “millions of people living and working in space.”

Conclusion: Amazon Proves that Change Drives Success

It’s safe to say that Amazon’s defining trait has been its willingness to change.

What started as an online bookstore has become a multi-industry behemoth.

It has crushed companies that don’t innovate … it has revolutionized several industries … and it shows no signs of slowing.

The biggest lesson from this change management case study?

Innovation and change drive success .

If you liked this article, you may also like:

Workplace diversity training: Effective training...

What is cultural change?

WalkMe Team

WalkMe spearheaded the Digital Adoption Platform (DAP) for associations to use the maximum capacity of their advanced resources. Utilizing man-made consciousness, AI, and context-oriented direction, WalkMe adds a powerful UI layer to raise the computerized proficiency, everything being equal.

Join the industry leaders in digital adoption

By clicking the button, you agree to the Terms and Conditions. Click Here to Read WalkMe's Privacy Policy

Case study: examining failure in change management

Journal of Organizational Change Management

ISSN : 0953-4814

Article publication date: 21 February 2020

Issue publication date: 22 April 2020

This case study aims to shed light on what went wrong with the introduction of new surgical suture in a Dutch hospital operating theatre following a tender. Transition to working with new surgical suture was organized in accordance with legal and contractual provisions, and basic principles of change management were applied, but resistance from surgeons led to cancellation of supplies of the new suture.

Design/methodology/approach

Researchers had access to all documents relevant to the tendering procedure and crucial correspondence between stakeholders. Seventeen in-depth, 1 h interviews were conducted with key informants who were targeted through maximum variation sampling. Patients were not interviewed. The interviews were recorded, transcribed and analysed by discourse analysis. A trial session and workshop were participatively observed. A cultural psychological perspective was adopted to gain an understanding of why certain practices appear to be resistant to change.

For the cardiothoracic surgeons, suture was more than just stitching material. Suture as a tactile element in their day-to-day work environment is embedded within a social arrangement that ties elements of professional accountability, risk avoidance and direct patient care together in a way that makes sense and feels secure. This arrangement is not to be fumbled with by outsiders.

Practical implications

By understanding the practical and emotional stakes that medical professionals have in their work, lessons can be learned to prevent failure of future change initiatives.

Originality/value

The cultural psychological perspective adopted in this study has never been applied to understanding failed change in a hospital setting.

- Operating theatre

- Cultural psychological perspective

- Failed change

- Surgical suture

Graamans, E. , Aij, K. , Vonk, A. and ten Have, W. (2020), "Case study: examining failure in change management", Journal of Organizational Change Management , Vol. 33 No. 2, pp. 319-330. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-06-2019-0204

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2020, Ernst Graamans, Kjeld Aij, Alexander Vonk and Wouter ten Have

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode .

Introduction

In the Netherlands, and more broadly in Europe, the cost of health care is rising and is expected to continue to rise ( Jenkner and Leive, 2010 ; Mot et al. , 2016 ). In light of this development, the challenge for those managing healthcare institutions is to spend smartly and cut costs where possible, while at the same time meeting changing patient demands (e.g. Dent and Pahor, 2015 ; Thistlethwaite and Spencer, 2008 ). The fact that managing the work and practices of medical professionals has always been difficult (e.g. Andri and Kyriakidou, 2014 ; Kennerley, 1993 ; Kirkpatrick et al. , 2005 ) adds to the complexity of meeting this challenge. Furthermore, health workers increasingly are held accountable for and are expected to be transparent about the outcomes of their work (e.g. Exworthy et al. , 2019 ; Genovese et al. , 2017 ). Although this trend is generally expected to lead to improved results, for medical professionals it also creates a sense of being under constant scrutiny. The emotions and feelings that are triggered in these kinds of processes have a substantial impact, which is acknowledged by both management practitioners and social scientists working in health care (e.g. Kent, 2006 ; Mark, 2005 ; Sebrant, 2014 ). In this case study, emotions and feelings are addressed by adopting a specific cultural psychological perspective. Cultural psychologists Paul Voestermans and Theo Verheggen (2013) call for more detailed psychological investigations into how people acquire embodied skills and mannerisms that are in line with professional demands, preferences and tastes. When emotions and feelings are felt or displayed, this is seen as an indication that something “real” is at stake that deeply involves professionals into their group, department or speciality. This paper demonstrates that this deep involvement can affect the success or failure of a change initiative, in this case the introduction of new surgical suture material in the operating theatre. This affective aspect may be underestimated in change management or only addressed in rather abstract fashion; by prematurely explaining resistance to change with the help of notions as professional autonomy, entitlement, stubbornness, culture and so on. The epistemological problem of discursively turning a descriptive label into an explanation or operational determinant of behaviour has been addressed particularly by discursive psychologists (e.g. Potter and Wetherell, 1987 , 1995a ) and cultural psychologists (e.g. Valsiner, 2014 ; Verheggen, 2005 ; Verheggen and Baerveldt, 2007 ). Although the concerns in this paper are practical and empirical, they can be traced back to the same problem. In management practice, and especially in the management of medical professionals, certain abstract characterizations of behaviour and change resistance can become problematic when they are no longer just employed as general, imprecise descriptions, but are reified and employed as stopgaps. As such, they preclude deeper and more detailed investigations into what is at stake for the people behind these abstractions. The added value of the approach adopted in this case study is that it does not need the reification and superimposition of notions such as shared values, culture or even professional autonomy, but allows for more holistic, or contextualized investigations into the social patterning of behaviour within professional groups or specialities. Truly delving into the tenacity of certain medical professional practices goes further than positing professional autonomy or entitlement as a cause, for instance. Earlier, this particular cultural psychological approach has successfully been adopted to describe psychological dynamics within the boardroom of a large healthcare organization ( Graamans et al. , 2014 ) and, more recently, to better understand and contribute to more effective interventions against the culturally embedded practice of female circumcision ( Graamans et al. , 2019a , 2019b ).

The case: resistance to new surgical suture in the operating theatre of a Dutch hospital

At the end of 2014, a large university hospital in the Netherlands launched a procurement tender exercise for surgical suture material. The rationale for hospital management to initiate this procedure was cost-cutting and standardization. The award criteria were focussed on the most economically advantageous tender. There were different suppliers on the market that were able to produce and deliver high-quality surgical suture material for a lower price than was currently being paid. Consequently, the tender was awarded to a new supplier. The top managers and purchasing manager who initiated the tender trod carefully and implemented this relatively small-scale change initiative according to some basic change management principles (e.g. Kotter, 2012 ): they built a guiding coalition that incorporated renowned medical specialists, they consulted department heads and they communicated the change to surgeons through different channels. Furthermore, it was recorded in the tender that the new supplier should provide value-adding services such as e-learning modules for surgeons, facilitate lengthy trial-use periods and offer workshops and support to the operating theatre. Hospital management conceived this first initiative as a test case for more extensive cost-cutting operations that were to follow. This project was supposed to be relatively easy, both in scale and in complexity. However, in the preparations ahead of the trial phase, a concern was raised by the cardiac surgeons to one part of the tender package involving sutures specifically used for cardiac surgery. Nevertheless, surgeons were forced to participate in testing the products supplied in the whole tender, including those products used in their specific specialities. Meanwhile, the initiators of the project felt that careful preparations of the testing phase had been made.

So, what went wrong? In mid-2015 – when this research project started – hospital management eventually met with fierce resistance from some of the hospital's cardiothoracic surgeons. They adamantly refused to work with the new suture material. The resistance took the form of surgeons expressing anger at management, stockpiling their own supplies of surgical suture, refusing to operate, holding managers accountable for patient deaths that could arise from use of the new suture and threatening to go to the press if such a thing indeed were to happen. Hospital management had anticipated some resistance, but not of this intensity. The end result was that the contract was eventually cancelled for sutures specifically used in cardiac surgery.

This research paper sets out to answer the following question: why are some medical professional practices so difficult to change, and what can we learn from this failed test case?

Theoretical background

As mentioned earlier, to better understand the entrenched nature of professional practices and the emotional stakes involved, we adopted a particular cultural psychological perspective. Following Voestermans' and Verheggen's approach ( 2013 ), we explicitly take the position that people are embodied and expressive beings who over time attune their emotions, feelings, preferences and tastes to the groups they belong to. People naturally feel more compelled to act in accordance with these preferences than to act upon abstract ideas, rules and protocols superimposed upon them from outside their group. Evidently, medical professionals are not exempt from feeling more compelled to act in accordance with these preferences just because they are a highly educated group of people. To the contrary, as a result of being members of their professional group for so long – through medical school, surgical residency, PhD studies and so on – they have learned to coordinate their actions on the basis of complex sets of agreements, conventions and arrangements that characterize their professional group.

Whereas agreements are easy to articulate, such as taking an oath, Voestermans and Verheggen (2013) reserve the term “arrangement” for the way members of exclusive and often elite groups coordinate their behaviour almost automatically within their own specifically cultivated environments, following deeply embodied patterns. These patterns and practices are group-typical due to the mutual attunement of emotions, feelings, preferences and taste that has taken place over time. The resulting automaticity makes that they do not need articulation, whereas practices based on agreements do. Evidently, medical professionals have practices founded on highly specialized scholarship and evidence-based research. But it is a mistake to think of their work as a purely cognitive, rather mechanistic affair. These practices are enacted and reenacted in the minutest interactions on an ongoing basis, and get more refined over time, until at one point they are felt and experienced more than that they are talked about . It is predicted that groups formed on the basis of such arrangements are particularly difficult to change. The apprehension that is triggered by attempts to change even the smallest element of such an arrangement is immediately felt.

Data collection

Data collection took place in a year starting from mid-2015. In total, 17 in-depth interviews were conducted that each lasted approximately 1 h. The respondents were targeted through maximum variation sampling until saturation was achieved and are listed in Table I . Patients were excluded beforehand. The interviews were audio-recorded after verbal consent was given. All but one interviewee agreed to be audio-recorded. This interviewee was comfortable, though, with the interviewer (EG) taking notes. The interviews were transcribed and anonymized. Apart from formal interviewing, extensive informal conversations on the topic took place with surgeons from different medical specialities.

Field notes were made on the observations of a trial session and a workshop facilitated by the new supplier. These notes were divided into four categories: observational notes, theoretical notes, methodological notes and reflective notes ( Baarda et al. , 2013 ).

Data analysis

To gain an understanding of the different positions people can take up in relation to the introduction of new surgical suture and underlying social arrangements, the interview transcripts were analysed by means of discourse analysis following the example and guidelines of critical psychologist Carla Willig (1998 , 2008) . Her particular approach to discourse analysis was chosen because it allows for a discursive psychological reading of the interview transcripts whereby interviewees as active agents justify, blame, excuse, request or obfuscate to achieve some objective: the “action orientation” of talking ( Edwards and Potter, 1992 , 2001 ; Potter and Wetherell, 1995b ). Her approach also allows for a more Foucauldian, or post-structuralist reading whereby inferences are made on how the discourses interviewees draw upon delimit and facilitate behavioural opportunities and experience ( Davies and Harré, 1990 , 1999 ; Henriques et al. , 1984 ; Parker, 1992 ). The latter approach assumes that discourses, on the one hand, and practices, on the other, are closely tied and reinforce each other. Discourse from this perspective is not so much a matter of talking about things, but is conceived as an expressive practice in itself. Conceptualized as such discourses can hint at underlying social arrangements in which certain practices, such as operating with tangible surgical suture material, are performed. To come to such a conclusion with a greater amount of certainty, we contend, the inferences made on the basis of discourse analysis must always be triangulated with data from participant observations and cross-checked with key informants.

In October 2017, the findings were tentatively fed back to the management board in a plenary session and to department heads in several individual conversations. Extensive peer debriefing sessions within our multi-disciplinary research team in which both the medical professional and managerial perspectives were represented by its members took place to help with cross-checking and interpreting the data.

Conducting discourse analysis ( Willig, 2008 ) on the interview transcripts revealed several discourses that interviewees drew upon when they talked about the transition to working with the new surgical suture and surgical suture more generally. The main constructions, discourses and implications in relation to the interviewees themselves – in discourse analytic terms called “subject positions” – are summarized in Table II .

Economic/managerial discourse

We are confronted with an enormous challenge. We have to drastically cut costs. This was an important test case, because more and bigger cuts are pending. This appeared to us as an easy win. However, … [1] . (Head of operating theatres)

Not only with surgical suture, but in general medical specialists resist change. That is because these suppliers have a powerful and very effective sales force. It is what we call vendor lock-in . (Purchasing manager)

I get that those boys [cardiothoracic surgeons] … what they are doing is very precise and technical. And surgical suture and needles are of crucial importance. On the other hand, there are always these sentiments. I mean, there are many medical centres, also abroad, where cardiothoracic surgeons suture with XXX [brand name of new supplier] and it is not turned into a complicated affair. But you cannot take away these sentiments just like that. We took note of these feelings, and nudged our staff to give it [the new surgical suture] a try and comply as much as possible. But to be honest, according to me at cardiac surgery there is a lot of emotion involved surrounding suture, … and it is not working for me. (Department head, surgery)

The initiator – the manager that came up with the idea to supposedly cut costs – does not know that suture curls and curls more-or-less depending on the brand. He does not know whether needles are round or angular. And he doesn't care. But for my work this is very relevant. It has nothing to do with professional autonomy. (Cardiothoracic surgeon)

One might argue with this cardiothoracic surgeon that this is exactly what the notion of professional autonomy refers to; in this case, the autonomy to decide for yourself, as a medical professional, which materials to work with. But that is not the point this cardiothoracic surgeon is making per se . Apparently, in the daily jargon of healthcare managers, the notion of professional autonomy is employed as a stopgap explanation for resistance so often that this surgeon anticipated its negative connotation related to changing surgical suture and change more general. For him at least, the superimposition of professional autonomy as an explanation does not do justice to how he relates to the issue of changing surgical suture. For him it is not an abstract affair, but genuinely felt, both in a tactile and in an emotional sense. Also note that academic definitions of professional autonomy (conceptual) do not always correspond to how such notions are employed in daily usage (performative). The cardiothoracic surgeons spoken to frequently drew upon a competitive/professional discourse in relation to surgical suture, enriched with examples and in far less abstract manner than those that posited professional autonomy as the main cause of change resistance.

Competitive/professional discourse

He [Roger Federer] goes down in the history books as the best professional tennis player ever. And that is because he has spent endless hours on the court practising and refining his skills. His tennis racket has become a natural extension of his arm. His tennis racket is his instrument. My instrument is my suture … suture and needles. (Cardiothoracic surgeon)

I didn't just go to medical school. After that I have done my residency, with a Ph.D., et cetera . All in all an extra 10 years. Everything that you are supposed to do, I did that, to become the best possible professional and to be able to deliver the best possible care for the patient. This is not some quick course. This is really … six years of medical school and then postgraduate for another six years. That isn't nothing. You have to be motivated, driven and persistent. And you hope to end up working for an institution that enables you to profess your passion. (Cardiothoracic surgeon)

It is important to note that the cardiothoracic surgeons quoted here did not exclusively drew upon this competitive/professional discourse that implies sacrifice, persistence and drive. But when they did, they challenged the economic/managerial discourse without actually talking about finances. In a way, to put it bluntly, money from this perspective should not be an object, or, at least, it should never be a priority.

Discourse on patient care

Let's say … I am going to operate your father with XXX [brand name of new supplier], but I am not used to working with that suture. It curls more and the needles go blunt quicker and the needles are square and therefore more difficult to position in the needle holder. So I need to focus more and I need to stress … I need to work [with the utmost precision]. Well, I am curious whether that manager would let me operate on his father. (Cardiothoracic surgeon)

Surgical suture was constructed as a lifeline on which the cardiothoracic surgeon relies on behalf of the patient. Replacing surgical suture is perceived as an unacceptable potential cause of failure. So whereas the competitive/professional discourse places the concerns and aspirations of the medical professional front and centre, this discourse on patient care places the concerns of the patient front and centre by means of the medical professional as his advocate. Implicit in both discourses, though, is that money should not be an object. As such, these discourses are counter-discourses to the economic/managerial discourse that legitimizes replacing surgical suture by that of a cheaper brand.

Discourse on safety and quality

So many things can go wrong. So changing surgical suture presents an additional risk. We prefer to operate a patient's heart only once and then never again. (Cardiothoracic surgeon)

If medical specialists use the argument of safety, patient safety, then you are finished. As an executive it is over. You start thinking, what if he is right; and I force him to work with this suture and something goes horribly wrong. He only has to say: “I told you it wasn't safe!” And then you, as an executive, are gone. Of course, you have to challenge and not be naive, but ultimately it is a show stopper … that safety argument. Another factor was, that my colleague in the Executive Board and I are not [cardiothoracic] surgeons. So we could not weigh in from our own experience. (Chairman of the Board)