The methodologies of the marketing literature: mechanics, uses and craft

- Theory/Conceptual

- Published: 08 November 2021

- Volume 11 , pages 416–431, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Terry Clark 1 &

- Thomas Martin Key ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7338-627X 2

924 Accesses

4 Citations

7 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Of the three scholastic modes with which to develop ideas and create knowledge in research: logic, empirics, and the literature , the latter is perhaps one of the least understood and studied. This paper is a first-of-its-kind delve into what the literature is, how it is used, and its impact as a foundation for theory and conceptual work in the discipline of marketing. We create a novel approach that provides a framework to understand the way literature functions in the research process and expose the hidden mechanics of how it creates and ties together various forms of meaning through what we call, citation-based reasoning. It is through this lens that we conclude with insights for how a deeper understanding of the literature can stoke continued impact in the marketing discipline, especially for theory building and conceptual development.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Contours of the marketing literature: Text, context, point-of-view, research horizons, interpretation, and influence in marketing

Marketing’s theoretical and conceptual value proposition: opportunities to address marketing’s influence.

A Backward Glance of who and what Marketing Scholars have Been Researching, 1977–2002

Journal of Retailing ( from 1925); Journal of Marketing ( from 1936); Journal of Advertising Research ( from 1960); Journal of Marketing Research ( from 1964); and Journal of Consumer Research ( from 1974).

Journal of Marketing, Journal of Marketing Research, Journal of Consumer Research, Marketing Science, International Journal of Research in Marketing, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science and Journal of Retailing .

AMS Review, Journal of Advertising, Journal of Consumer Psychology, Journal of Innovation and New Product Management, Journal of Interactive Marketing, Journal of International Marketing, Journal of Macromarketing, Journal of Marketing Management, Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, Journal of Public Policy.

And Marketing, Journal of Strategic Marketing, European Journal of Marketing, Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, and Quantitative Marketing and Economics.

Management Science, Journal of Business Research, and Journal of International Business Studies.

Business Horizons, California Management Review, Harvard Business Review , and MIT Sloan Management Review .

Journal of Marketing , Journal of Marketing Research , Marketing Science , Journal of Consumer Research and Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science .

Accounting Organization and Society, The Accounting Review, Journal of Accounting Research and Journal of Accounting and Economics.

Journal of Finance, Journal of Financial Economics, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis and Review of Financial Studies.

Academy of Management Review, Academy of Management Journal, Administrative Science Quarterly and Strategic Management Journal.

And JMR ’s stated mission seems to corroborate this view “ JMR seeks papers that make methodological, substantive, and/or theoretical contributions…Authors seeking to make a methodological contribution should compare their proposed new methods to established methods…Papers that review methods to stimulate further research are also welcome” ( https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/journal-of-marketing-research/journal203574 ).

Andrews, J. C., Durvasula, S., & Akhter, S. H. (1990). A framework for conceptualizing and measuring the involvement construct in advertising research. Journal of Advertising, 19 (4), 27–40.

Article Google Scholar

Alonso, A. (2020). Once upon a time there was… a Scientific Journal (Part I), Fundación Arquia Blog , April 2, https://blogfundacion.arquia.es/en/2020/04/once-upon-a-time-there-was-a-scientific-journal-i/ accessed 2/14/2021.

Ataman, B. M., Van, H. J., Heerde, H., & Mela, C. F. (2010). The long-term effect of marketing strategy on brand sales. Journal of Marketing Research, 47 (5), 866–882.

Bartlett, T. (2021). Do we really need more controversial ideas?, Chronicle of Higher Education , May 17th, https://www.chronicle.com/article/do-we-really-need-more-controversial-ideas

Bartels, R. (1951). Can marketing be a science? Journal of Marketing, 15 (3), 319–328.

Baumgartner, H., & Pieters, R. (2003). The structural influence of marketing journals: a citation analysis of the discipline and Its subareas over time. Journal of Marketing, 67 (2), 123–139.

Bergkvist, L. (2020). Measure proliferation in advertising research: Are standard measures the solution. International Journal of Advertising , 40 (2), 311–323.

Bergkvist, L., & Eisend, M. (2021). The dynamic nature of marketing constructs. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 49, 521–541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-020-00756-w

Brown, L. O. (1948). Toward a profession of marketing. Journal of Marketing , 13 (1), 27–31

Bruner, G. (2003). Combating scale proliferation. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 11 , 362–372. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jt.5740091

Caporin, M., & Sartore, D. (2006). Methodological aspects of time series back-calculation. Working Papers , Department of Economics Ca’ Foscari University of Venice No. 56/WP/2006

Chabowski, B. R., & Mena, J. A. (2017). A review of global competitiveness research: Past advances and future directions. Journal of International Marketing, 25 (4), 1–24.

Chabowski, B. R., Samiee, S., Tomas, G., & Hult, M. (2013). A bibliometric analysis of the global branding literature and a research agenda. Journal of International Business Studies, 44 (6), 622–634.

Clark, T. & Carol, A. (2011). Shelby hunt and the great revolution in Marketing Legends, Volume 2, Marketing Theory: Philosophy of Science Foundations of Marketing , Jagdip Singh editor, Sage Publications, 141–147.

Clark, T., Key, T. M., Hodis, M., & Rajaratnam, D. (2014). The intellectual ecology of mainstream marketing research: An inquiry into the place of Marketing in the Family of business disciplines. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Sciences, 42 (3), 223–241.

Desai, P. S., Kalra, A., & Murthi, B. P. S. (2008). When Old Is Gold: The Role of Business Longevity in Risky Situations. Journal of Marketing, 72 (1), 95–107.

Google Scholar

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18 (1), 39–50.

Fuller, S. (2005). The Intellectual . Icon Books Ltd.

Gordon, R. A., & Howell, J. E. (1959). Higher Education for Business . Columbia University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Gu, X., & Blackmore, K. (2017). Characterisation of academic journals in the digital age. Scientometrics, 110, 1333–1350.

Hult, G., Tomas, M., Neese, W. T., & Bashaw, R. E. (1997). Faculty perceptions of marketing journals. Journal of Marketing Education, 19 (Spring), 37–52.

Hunt, S. D. (1971). The morphology of theory and the general theory of marketing. Journal of Marketing, 53 (2), 65–68.

Hunt, S. D. (1976). The nature and scope of marketing. Journal of Marketing, 40 (3), 17–26.

Hunt, S. D. (2018). Advancing marketing strategy in the marketing discipline and beyond: From promise, to neglect, to prominence, to fragment (to promise?). Journal of Marketing Management, 34 (1–2), 16–51.

Hunt, S. D. (2020). AMS Review, 10, 183–188.

Jaakkola, E. (2020). Designing conceptual articles: Four approaches. AMS Review, 10 (1), 18–26.

Jacoby, J. (1978). Consumer research: a state of the art review. Journal of Marketing, 42 (2), 87–96.

Kanetkar, V., Weinberg, C., & Weiss, D. (1992). Price sensitivity and television advertising exposures: Some empirical findings. Marketing Science , 11(4), 359–371

Kohli, A. K., & Jaworski, B. J. (1990). Market orientation: The construct, research propositions, and managerial implications. Journal of Marketing, 54 (2), 1–18.

Kollat, D. T., Blackwell, R. D., & Engel, J. F. (1972). The current status of consumer behavior research: Developments during the 1968–1972 period, in SV - proceedings of the third annual conference of the association for consumer research, eds. M. Venkatesan, Chicago, IL : Association for Consumer Research, Pages: 576–585.

Lander, L. J., & Parkin, T. R. (1966). Counterexample to euler’s conjecture on sums of like powers. Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, 72 (6), 1079.

Lehmann, D. R. (2005). Journal evolution and the development of marketing. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 24 (1), 137–142.

Lipstein, B. (1965). A mathematical model of consumer behavior. Journal of Marketing Research, 2 (3), 259–265.

Markus, L. M., & Saunders, C. (2007). Editor's comments: Looking for a few good concepts...and theories...for the information systems field. MIS Quarterly , 31(1), iii-vi.

MacInnis, D. J. (2011). A framework for conceptual contributions in marketing. Journal of Marketing, 75 (4), 136–154.

McNeely, I. F., & Wolverton, L. ( 2008). Reinventing Knowledge: From Alexandria to the Internet , W. W. Norton & Company

Mitra, A., & Lynch, J. G. (1995). Toward a reconciliation of market power and information theories of advertising effects on price elasticity. Journal of Consumer Research, 21, 644–659.

Palmatier, R. W., Houston, M. B., & Hulland, J. (2018). Review articles: Purpose, process, and structure. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46 (1), 1–5.

Reibstein, D. J., Day, G., & Wind, J. (2009). Guest editorial: Is marketing academia losing its way? Journal of Marketing., 73 (4), 1–3.

Seggie, S. H., & Griffith, D. A. (2009). What does it take to get promoted in marketing academia? Understanding exceptional publication productivity in the leading marketing journals. Journal of Marketing, 73 (1), 122–132.

Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 104, 333–339.

Summers, E. (1983). Bradford’s law and the retrieval of reading research journal literature. Reading Research Quarterly, 19 (1), 102–109. https://doi.org/10.2307/747340 .

Theoharakis, V., & Hirst, A. (2002). Perceptual differences of marketing journals: a worldwide perspective. Marketing Letters, 13 (4), 389–402.

Varadarajan, R. (2020). Relevance, rigor and impact of scholarly research in marketing, state of the discipline and outlook. AMS Rev, 10 , 199–205.

Vargo, S. L., & Koskela-Huotari, K. (2020). Advancing conceptual-only articles in marketing. AMS Review, 10, 1–5.

Waerden, B. L. (1975). Science Awakening, Noordhoff International.

Wilkie, W. L., & Moore, E. S. (2003). Scholarly research in marketing: Exploring the “4 eras” of thought development. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 22 (2), 116–146.

Yadav, M. S. (2010). The decline of conceptual articles and implications for knowledge development. Journal of Marketing, 74 (1), 1–19.

Yadav, M. S. (2020). Reimagining marketing doctoral programs. AMS Review, 10, 56–64.

Zeithaml, V., Parasuraman, A., & Berry, L. (1990). Delivering Quality Service: Balancing Customer Perceptions and Expectations . The Free Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Marketing, College of Business, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL, 62901, USA

Terry Clark

Department of Marketing, Strategy, and International Business, College of Business and Administration, University of Colorado, Colorado Springs, Colorado Springs, CO, 80918, USA

Thomas Martin Key

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Terry Clark .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

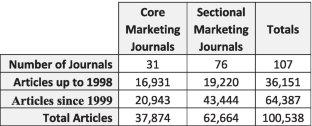

Marketing core journals

Appendix ii, marketing sectional journals, rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Clark, T., Key, T.M. The methodologies of the marketing literature: mechanics, uses and craft. AMS Rev 11 , 416–431 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13162-021-00210-2

Download citation

Received : 20 May 2021

Accepted : 10 October 2021

Published : 08 November 2021

Issue Date : December 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13162-021-00210-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Marketing literature

- Theory development

- Research craft

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

How to Read the Literary Market: An Introduction

Understood as a modern institution, literature is historically bound to the extension of market rationality. The commodification of literature since the late eighteenth century has changed the ways in which we handle literary works: rather than just perused by individual readers, books are promoted, traded, consumed, and legally protected. Over the past three decades, scholars have focused increased attention on how to conceptualize this encroachment of market principles into the sphere of culture ( Agnew 1986; Bourdieu 1996; Woodmansee 1994 ). They have shown that concepts like ‘the fine arts’, ‘high literature’, and ‘aesthetic autonomy’ have evolved not in opposition but rather as historical responses to and functions of the commercialization and professionalization of culture. In so doing they have reflected upon an array of intersecting cultural developments such as the specialization of the poet as professional writer and distributor of a marketable commodity and the diversification of literary practice across artistic and commercial spaces. What conjoins these projects is the broad question of how to read the literary market.

Many approaches toward literary market economies have pursued the aim of identifying the absent causes that determine literary production and consumption. This objective informed the works of marketplace critics of the 1980s (e.g., Gilmore 1985; Michaels 1987 ) but has also inspired the bulk of the more recent “New Economic Criticism” (e.g., McClanahan 2016; Poovey 2008 ). These branches of revisionist scholarship revolve around the social and economic, the material and ideological implications and constraints conditioning the production, reception, and distribution of literature. They emphasize literature’s crucial function as a site of political resistance and complicity, albeit by positing a rather static causality between the social and the cultural, politics and literature.

A number of competing contemporary approaches stemming from the resurgence of the sociology of literature have provided alternatives to the premises established by economic literary criticism. This development deserves a word of explanation. For what literary scholars think is sociology differs notably from how sociologists would identify their own discipline. Moreover, “‘sociology of literature’ has always named a polyglot and rather incoherent set of enterprises. It is scattered across so many separate domains and subdomains of scholarly research, each with its own distinct agendas of theory and method, that it scarcely even rates the designation of a ‘field’” ( English 2010 , v). For example: Birmingham School cultural materialism does champion a broad sociological interest in the life worlds of readers and writers. But that type of work is only peripherally relatable to some of the projects that sailed under New Historicist flags in the 1980s, although scholars in the wake of Stephen Greenblatt had a similarly committed interest in the social. Likewise, the reception of Michel Foucault’s bio-political writings of the 1970s and early 1980s encouraged a good deal of critics to inquire into the social and discursive foundations of power regimes. But that interest remained insular, almost disconnected from projects designed in pursuit of site-specific, empirical analyses of social power.

This sense of diversity notwithstanding, there is a set of vaguely identifiable thematic concerns and methodological premises at the center of sociological literary scholarship. When literary scholars turn into sociologists they typically focus on different actors in the literary market: publishing houses, agencies, and retailers; they look at matters of literacy and reading techniques, the interrelations of publishers, authors, and readers, and the history of production technology, treating the book and the literary text as objects of commerce and trade, and as cornerstones in the diverse constructions of socio-historical and cultural identities. These issues, to be sure, have troubled literary scholars since the beginnings of academic English studies in the early twentieth century, but they have never been clustered exclusively within a subfield called ‘sociology of literature’ or ‘marketplace criticism.’ In part this has to do with the evolution of literary theory during the post-45 period on both sides of the Atlantic, wherein Marxism was long considered to be the go-to paradigm for all things social. And while the continued interest in Pierre Bourdieu’s cultural sociology has helped to reintegrate sociological study into the domains of the English department since the 1990s, this interest has turned the field of literary production into a somewhat predictable metaphor customarily used to describe various forms of capital exchange (and barely anything else).

Focusing on these putative limitations, a number of recent studies have pointed out that the bulk of Bourdieu-derived scholarship still rests on the opposition between aesthetic and economic value, arguing that modern literature is marked by the tension of withdrawing from the mechanisms of the market and, at the same time, being shaped by it ( English 2005; Griem 2017; Leypoldt 2014; Theisohn and Weder 2013 ). In seeking to circumnavigate such binary models of the literary field, these critics have brought back to the forefront of scholarship questions of aesthetic experience, affect, or singularity, and thus re-conceptualized the market as a social institution – and a Latourian actor-network ( Felski 2015 ) – irreducible to its function of monetary allocation (e.g., Sklansky 2017 ). Following these interventions, aesthetic and economic value are neither irreconcilable nor indistinguishable, and questions about the form, appearance, and experience are put in fruitful dialogue with questions about the commodification and marketability of literary works.

Moreover, there has been a strong comeback of studies in the history of the book that in many ways complements the symbolic readings of the literary market both in terms of its transatlantic dimension and in its historical evolution. While there were incipient forms of what we now understand to be a literary market in eighteenth-century Britain ( Siskin 1998 ), the idea of a professionalized literary field did not become plausible on US soil before the 1840s. And even then, there remained a tremendous influence of British and continental European publishing on American authors, publishers, and retailers as the American market was constrained by rigid copyright laws ( McGill 2010 ). As Joseph Rezek has argued, conceiving of literary history in national terms denies the material and economic realities of early nineteenth-century literature: “British and American publishing were not separate affairs in the early nineteenth century” ( Rezek 2015 , 25). Literary practitioners at the time were aware that the literary marketplace of the early nineteenth century spanned the Atlantic. And they also knew how incoherently and unpredictably this market evolved across nation-states and institutions. For example: Boston, New York, and Philadelphia developed relatively early into powerful publishing centers in the US, not least because of their favorable geographical locations in the Northeast. But the Midwest and the Southern colonies, lacking stable trade routes to Europe, remained isolated as literary regions for the better part of the nineteenth century. Similar discontinuities can be observed in the case of London’s ascent into “world literary space” ( Casanova 2004 ), to borrow Pascale Casanova’s term, and the consequent emergence of an Anglo-European literary periphery in the eighteenth century. Given these contexts, any inquiry into the relationship between economy and literature must take account of this complex history, rather than simply assume that a literary market and its variously entangled hierarchies of value have always been there.

This special issue creates a critical forum on theories, methods, and techniques currently used for scholarly work at the intersection of culture and the economy. Reflecting the issue’s concerns with literature and the market, the articles cover a wide historical scope, ranging from the nineteenth century to the present. And by conjoining theoretical and historical concerns, they highlight the aesthetic, cultural-sociological, and narrative dimensions of literature and the market. Among other issues, the contributors focus on particular theoretical trajectories to refine our understanding of the relation between literature and the market, and they discuss the methods of analysis that are most promising for the study of modern literature and its integral role within market society. At the same time, most of the contributors relate their arguments to concrete sites of literary practice so as to maintain that any theoretical argument about the literary market can only make sense on the grounds of the market’s empirical foundations. Understood as social practices, reading and writing are never context-free.

This special issue’s methodological intervention grows out of a literal understanding of its title, “How to Read the Literary Market.” We move beyond an understanding of the literary market as a context or institutional setting that must be analyzed with extra-literary means, as if the market remained external to the literary text. Rather, works of literature themselves can be instructive for how to read (i.e., to form, comprehend, and reform) dynamics of the literary market. A number of our contributions therefore explore literary texts that highlight and draw on market dynamics and their effects on literary aesthetics and narrative structures. Accordingly, the essays assembled here seek to show that a sociology of literature must not only reflect upon the social and economic forces emerging from and around literature, but that it needs to tackle the very questions literary texts pose vis-à-vis the social; questions, that is, which target issues of race, class, gender, and the issue of creative production itself.

Considering the meaning and the status of the ‘literary’ within the framework of the literary market, Tim Lanzendörfer’s essay is both a critical reflection of the historically established and culturally inherent conflicts between ‘high’ and ‘low,’ avant-gardist and commercial, autonomous and complicit, and thereby an inquiry into this issue’s larger methodological interest. Philipp Löffler, in turn, offers a more specific account of central developments in the antebellum book market, focusing on two case studies: Nathaniel Hawthorne’s ascent into the literary establishment of the 1840s – based mainly on the promotion of his short fiction – and the attempts to advertise Harriet Beecher-Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin across socially and politically diverse readerships in the South and the North.

Nicola Glaubitz’s essay explicitly asks “How Useful is Bourdieu’s Notion of Capital for Describing Literary Markets?” Her answer – “Yes, Bourdieu’s notion of capital is useful” – is grounded in a careful analysis of three major critical works indebted to Bourdieu’s work: John Guillory’s Cultural Capital (1993); James English’s The Economy of Prestige (2005); and Clayton Childress’s Under the Cover (2017). Julika Griem integrates conceptions of literary markets, marketing, and marketability into the study of literature. By combining textual and sociological analysis, Griem turns to spatial and spatializing strategies on various levels of literary communication, relating Bourdieu’s sociology of literature to more recent studies on literary ecologies and consumer culture by David Alworth and Jim Collins.

The essays by Florian Sedlmeier and Stefanie Mueller explore the relationship between African American writing and the sociocultural implications of the literary market. Sedlmeier’s essay confronts Pierre Bourdieu’s notions of literary capital with William Dean Howells’s criticism of African American writers. The lens of Bourdieu, Sedlmeier argues, allows us to see the tension between the possibility of converting cultural difference into literary capital and the necessity to maintain a universal notion of literary capital, with which Howells endowed writers such as Paul Dunbar and Charles Chesnutt. In her essay “‘No more little boxes’ – Poetic Positionings in the Literary Field,” Stefanie Mueller analyzes Thomas Sayers Ellis’s poem “Skin, Inc.” (2010). In her close reading, Mueller shows that Ellis uses the metaphor of incorporation in terms of its economic and its formal affordances. Also drawing on Bourdieu’s work, Mueller thinks of the poem as a form of poetic position-taking in the early twenty-first-century United States. While she explores the literary marketplace as presented in Ellis’s poem, Mueller draws particular attention to the role of race in the US literary field, in particular with regard to what has been labeled a ‘post-soul aesthetic.’

The editors would like to thank Eleni Patrika and Aiden John for diligently formatting the issue.

Agnew, J.-C. 1986. Worlds Apart: The Market and the Theater in Anglo-American Thought . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/CBO9780511571404 Search in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, P. 1996. Rules of Art . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. 10.1515/9781503615861 Search in Google Scholar

Casanova, P. 2004 [1999]. The World-Republic of Letters. Trans. Malcolm DeBevoise . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Search in Google Scholar

English, J. 2005. The Economy of Prestige: Prizes, Awards, and the Circulation of Cultural Value . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 10.4159/9780674036536 Search in Google Scholar

English, J. 2010. “Everywhere and Nowhere: The Sociology of Literature after ‘The Sociology of Literature’.” New Literary History 41: v–xxiii. 10.1353/nlh.2010.0005 Search in Google Scholar

Felski, R. 2015. “Latour and Literary Studies.” PMLA 130: 737–42, https://doi.org/10.1632/pmla.2015.130.3.737 . Search in Google Scholar

Gilmore, M. T. 1985. American Romanticism and the Marketplace . Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. 10.7208/chicago/9780226293943.001.0001 Search in Google Scholar

Griem, J. 2017. “Literatur und Ökonomie.” In: Handbuch zur Materialität der Literatur , edited by S. Scholz. Stuttgart: Metzler. Search in Google Scholar

Leypoldt, G. 2014. “Singularity and the Literary Market.” New Literary History 45: 71–88, https://doi.org/10.1353/nlh.2014.0000 . Search in Google Scholar

McClanahan, A. 2016. Dead Pledges: Debt, Crisis, and Twenty-First-Century Culture . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. 10.11126/stanford/9780804799058.001.0001 Search in Google Scholar

McGill, M. 2010. “Copyright.” In A History of the Book in America , Vol. 2, edited by R. A. Gross and M. Kelley. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 198–210. Search in Google Scholar

Michaels, W. B. 1987. The Gold Standard and the Logic of Naturalism . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Search in Google Scholar

Poovey, M. 2008. Genres of the Credit Economy: Mediating Value in Eighteenth-and Nineteenth-Century Britain . Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. 10.7208/chicago/9780226675213.001.0001 Search in Google Scholar

Rezek, J. 2015. London and the Making of Provincial Literature: Aesthetics and the Transatlantic Book Trade, 1800–1850 . Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. 10.9783/9780812291629 Search in Google Scholar

Siskin, C. 1998. The Work of Writing: Literature and Social Change in Britain, 1700–1830 . Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. Search in Google Scholar

Sklansky, J. 2017. Sovereign of the Market: The Money Question in Early America . Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. 10.7208/chicago/9780226480473.001.0001 Search in Google Scholar

Theisohn, P., and C. Weder, eds. 2013. Literaturbetrieb: Zur Poetik einer Produktionsgemeinschaft . Paderborn: Wilhelm Fink. Search in Google Scholar

Woodmansee, M. 1994. The Author, Art, and the Market: Rereading the History of Aesthetics . New York, NY: Columbia University Press. Search in Google Scholar

© 2020 Dustin Breitenwischer et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- X / Twitter

Supplementary Materials

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

Journal and Issue

Articles in the same issue.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

A qualitative analysis of the marketing analytics literature: where would ethical issues and legality rank?

Imran bashir dar.

1 Department of Technology Management, Faculty of Management Sciences, International Islamic University, Islamabad, Pakistan

Muhammad Bashir Khan

Abdul zahid khan, bahaudin g. mujtaba.

2 Management and Human Resources, Huizenga College of Business and Entrepreneurship, Nova Southeastern University, 3301 College Avenue, Fort Lauderdale, FL 33314-7796 USA

In response to the concerns of global data-driven disruption in marketing, this qualitative study explores the issues and challenges, which could unlock the potential of marketing analytics. This might pave the way, not only for academia–practitioner gap mitigation but also for a better human-centric understanding of utilising the technologically disruptive marketing trends, rather making them a foe. The plethora of marketing issues and challenges were distilled into 45 segments, and a detailed tabulation of the significant ones has been depicted for analysis and discussion. Furthermore, the conceptually thick five literary containers were developed, by coupling the constructs as per similarity in their categorical nature and connections. The ‘ethical issues and legality’ was identified as on the top, which provided literary comprehension and managerial implication for marketing analytics conceptualisation in the fourth industrial revolution era.

Introduction

The three dominant approaches (institutional, functional, commodity) used in past decades for dealing with overall marketing science concepts seem to be losing their viability with speed (Shepherd 1955 ), parallel to the availability of digital business avenues and diversity in sources of data (Hauser 2007 ; Dasan 2013 ; Wedel and Kannan 2016 ). Therefore, the analytics approach, with a problem-solving thinking frame, though had been discussed in the 1950s, is being observably adapted, and outcomes in terms of causation are continuously being gauged. Thoughtfully, academia has been left behind in this case, where now curriculum innovation (Wilson et al. 2018 ) and a shift of practices to gain academic coherence is being reportedly welcomed (Davenport and Harris 2017 ).

As per the field of Marketing, the mapping and quantification of causality are becoming the core of Marketing science, which is mastered by Marketing Analytics with a focus on action ability and informed decisions that have strategic value while not overlooking hard-data evidence (Grigsby 2015 , pp. 15–16; Rackley 2015 , pp. 1–30). Informed decisions, for the survival of any organisation, must get into action to create readiness for change (reaction) as per the evolution in the outer environment. The same is true for the biologically continued existence of organisms and for simple things as driving a car without a dashboard (Rackley 2015 , pp. 1–6). Even during the coronavirus pandemic situation, the thorniest question for board rooms today is the usage of disruptive technologies to sustain marketing efforts that could bear fruit (Balis 2020 ; Shah and Shah 2020 ; Waldron and Wetherbe 2020 ).

In terms of defining the concept of marketing analytics, there are many notable research endeavours, from the start of the new millennium, each having its analytical grounds (Davenport and Harris 2017 ). The researchers confined themselves to the sense that could glue the understanding blocks of academia and practitioners. So, marketing analytics has been sensed as exposing oneself to the descriptive, diagnostic, predictive, and prescriptive stages for insightful data reservoirs, for functional intimacy of marketing science in the contemporary world to sustain the competition and get better results through smarter decisions (Davenport and Harris 2017 ; Davenport et al. 2010 ; Davenport 2006 ; Farris et al. 2010 ).

Talking about issues and challenges, marketing analytics is research heaven for academia but a trap for the practitioners, as it has emerged from the process of convergence and divergence of multifaceted business areas (Mahidhar and Davenport 2018 ; Davenport and Kim 2013 ; Davenport and Harris 2007 ). Moreover, it is a continuous struggle to know about the customers before they know about themselves, and it could be done by marketing analytics (Davenport and Harris 2017 ; Farris et al. 2010 ). This can pave the way for a culture that would be conducive for marketing analytics in the corporate world. Marketing analytics is shifting from being merely a buzzword to full-fledge research area that is termed to be multidimensionally nascent, which is apparent by various systematic literature reviews on the subject concerned in connection to data-rich environments (Wedel and Kannan 2016 ), web analytics and key performance indicators (Saura et al. 2017 ), social media metrics (Misirlis and Vlachopoulou 2018 ), defining the field and convergence status (Krishen and Petrescu 2018 ), data mining (Dam et al. 2019 ), links to other fields and methods (France and Ghose 2019 ), research and practice environments (Iacobucci et al. 2019 ), and prescriptive analytics (Lepenioti et al. 2020 ).

Presently, senior marketing professionals are worried about their ability to measure these factors (Mahidhar and Davenport 2018 ). The data reservoirs are available, but the aligned mechanism for converting the data into actionable insights is observed to be a big missing link (Farris et al. 2010 ), which could result in analytically strategical misfit from consumer and marketing perspective (Zhang et al. 2010 ). Therefore, marketing analytics could be a threat to almost all the business models for pre-data backed economy, held globally. This may be termed as sustainable disruption, which means a continuous rigorous change (Davenport and Kim 2013 , pp 105–110). Moreover, it is evident that the improvement in technology has been phenomenal in the past century; still, the remarks of Peter Drucker are relevant in terms of computer and man, so the study of the issues and challenges would be necessary to mitigate any risks of failure (Guercini 2020 ). Therefore, despite the plethora of books and articles on the problem area concerned, a lack of research is apparent in terms of exhaustively studying the marketing analytics issues and challenges.

Procedural genesis for systematic literature review (SLR)

As pointed out by connection between decades of research that the view about systematic literature review (SLR) has been evolving and enriching itself (Webster and Watson 2002 ). Therefore, confining to a step-by-step approach and sticking to a set pattern defined by past research, which have been cited by the majority of the researches, were followed by the researchers for a line of action that could result in a significant research outcome (Levy and Ellis 2006 ; Okoli and Schabram 2010 ). The steps were grouped into three levels as input planning, process execution, and outcome reporting, by following the steps as reflected in Fig. 1 .

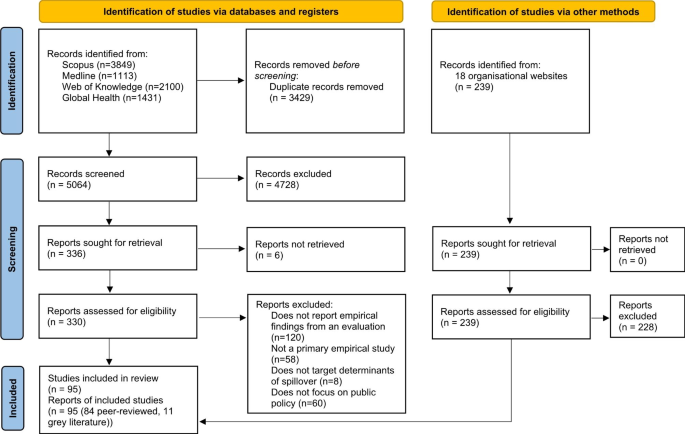

PRISMA statement

PRISMA, “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses”, is one of the most endorsed ways for diagrammatically reporting the quality and rigour of systematic literature reviews. Therefore, the researchers applied the guidelines by Moher et al. ( 2009 ), with 62,621 citations, known as the “PRISMA Statement”.

Apart from reporting the systematic review, AMSTAR “measurement tool for assessment of systematic reviews” was studied (Shea et al. 2009 ), cited 1506 times, to enhance the quality of this study in terms of methodological validity and reliability. Additionally, the structure of “PICOS”, “participants, interventions, comparators, outcomes, and study design” was followed to clarify the scope of this study in terms of the multiple interventions and criteria (Smith et al. 2011 ; Van den Bosch and Sang 2017 ). Therefore, the quality assessment and enhancement of reporting, methodological aspects, and scope were exhausted through applying PRISMA, learning from the AMSTAR tool and following PICOS. The researchers did their best in not compromising on any level and dimension for developing a valuable and comprehensive systematic literature review study.

SLR process step by step

The PRISMA statement has four dimensions: (i) Identification, (ii) Screening, (iii) Eligibility, and (iv) Included, as reflected in Fig. 1 . These dimensions are further bifurcated into five steps. First, research questions were developed based on the current basic understanding of the problem from the call for papers and impactful recent research reservoir available from various databases and high-quality journals. The backward search in terms of the references, authors, and keywords was done to see through the results for any missing piece of research work, based on which the present work has been carried out (Webster and Watson 2002 ). Additionally, the forward search was done to review the further contribution of authors and its relevance to the problem. Moreover, the forward reference search was exercised to check the selected being cited by other researchers. This exercise of backward and forward search equipped the researchers with a basic picture of the theoretical contributions in terms of the problem at hand (Fig. 2 ).

Explored marketing analytics issues and challenges (MAICs)

The second step to identify the related studies by applying multiple metrics (Harzing 2007 ) . Third, the search metrics were accompanied by time frame and other restrictions, along with key search terms for exploring the digitally available research reservoirs. The fourth step has been inclusion and exclusion process application on the filtered body of quality research work. At this stage, the spearhead inspection of the literary reservoir is executed in terms of problem and research questions relevancy. The fifth step is to synthesise the finalised stream of research work, having a significant contribution in the problem area.

Research questions

This research study is aimed to address the proceeding research questions:

What sort of issues and challenges related to marketing analytics implementation were identified by the past research?

What are the most critical/highly ranked issues and challenges of marketing analytics (2000 to 2020)?

Criterion based exhaustive literature exploration

The level of exhaustiveness is measured by observation of search outcomes through “Publish or Perish 7” (PoP7) software sourced from Harzing ( 2007 ), accompanied with backward and forward searches, through different keywords relating to various dimensions of the research questions being considered. Once the output gets repeatedly and notably similar to previous search exercises, then the reliable maturity level could be achieved. For this purpose, a wide variety of carefully selected keywords, based on topic/area, marketing analytics, in this case, are used in a variety of combination through applying Boolean operators like OR/NOT/AND to enhance the “search reach” and enrich “search depth” (Webster and Watson 2002 ; Hedges and Cooper 2009 ; Baker 2016 ). The relevancy of the keywords was adapted by first searching for the highly cited articles discussing “marketing analytics” and fetching keywords for issues and challenges from them. Afterwards, those keywords, such as “marketing analytics” AND “barrier” OR “challenge”, “strategy”, “issue”, “failure”, “success”, “implementation”, “performance”, “measurement”, “understanding”, “problem”, “application”, “operation”, “process”, “execution”, “acceptance”, “critical success factors”, “marketing analytics implementation challenges”, and “marketing analytics implementation issues and challenges”. Total papers (deleting all duplications, excluding other material) extracted were 854 from which only 73 highly cited articles were selected. Notably, even after searching through coupling the issues and challenges keywords with “marketing analytics”, the filters of the rigorous study were plugged in to go beyond search metrics.

Databases and digitalised reservoirs

For furthering the research process, decision making for the selection of databases has been projected by backward and forward search, which presented the journals and publishers having the most relevant and impactful number of articles. Therefore, the question of “where” and “how” has been addressed for the readiness of review (Levy and Ellis 2006 ). The databases below are the filtered reservoirs, as per citations and relevancy of the articles related to the issues and challenges, and availability at the university library or beyond it:

- Harvard Business Press

- Taylor & Francis

- Wiley Online Library

- Journals of American Marketing Association (AMA)

- INFORMS PubsOnline

- Ingenta Connect

Filtration and extraction of research articles

The amalgamation of the research articles through strict numerous restrictions has been ground into final filtration by exploring the content in them in terms of the problem area, marketing analytics issues, and challenges, as per the past research available. The articles that notably and chiefly discussed the issues and challenges were extracted after review, and the remaining studies were abandoned (Levy and Ellis 2006 ; Hedges and Cooper 2009 ). The numbers of the selected papers for review were narrowed by exerting the following metrics:

- (i) As reflected in the step three of PRISMA statement, the papers having relevant and quality research (peer-reviewed, impact factor journals and high citations) were selected

- (ii) The research papers or conference papers that are not peer reviewed, duplicates, and nonrelevant papers were discarded

- (iii) Articles written in English language, published within the time frame of 2000–2020, discussing the issues and challenges of marketing analytics in a reasonable manner were included (Levy and Ellis 2006 ; Okoli and Schabram 2010 ).

The researcher for point (i) first checked the relevancy of the research paper or conference paper and whether they are peer reviewed or not. This does not mean that the researchers filtered the relevant research papers or conference papers that were peer reviewed and were not impact factor or highly cited. Actually, the fifth stage of “PRISMA Statement” steered the researchers to finalise and extract the articles having significant contribution, which resulted in terms of impact factor journal articles mostly that were eventually highly cited as well. It can be tracked from the results reflected in “Table 6 —ScientoMetrics-Quartile Analytics” that 92% of the finalised papers are categorised within Q1 to Q3, whereas 80% are from Q1.

ScientoMetrics-quartile analytics

This extensive exercise paved the way for finalised selection of 59 papers (only a handful) from 73 highly cited, based on the original result of 997 that were selected, as detailed in Tables Tables1 1 and and2 2 (Table (Table3 3 ).

Sum of holistic search by research databases

The bold values signify the numeric result in terms of frequency for the research papers observed as per the captioned criteria

Research articles filtered/finalised by research databases

Theoretical mapping of marketing analytics (2000–2020)

Synthesise and evaluation

The papers discussing marketing analytics issue and challenges identified in Table Table2 2 pave the way for detailed synthesis as per research question 1. Table Table4 4 projects the issues and challenges of marketing analytics for the previous two decades. The papers have been organised in terms of their publication year and details about the specific qualitative and quantitative method that is provided as well.

Marketing analytics issues and challenges (2000–2020)

The exhaustive search for the marketing issues and challenges from the relevant, impactful, and having significant contribution reflected, along with the overall literature synthesis, reflected the list of 45 marketing analytics issues and challenges, captioned as Marketing Analytics Issues and Challenges (MAICs 1–45), in Table Table5. 5 . From these MAICs, the non-significant ones have been dropped, which can be traced from the numbering of the issues and challenges accordingly, in Table Table4. 4 . The citations and journal information about the finalised 59 research papers are tabulated in Appendix. Moreover, Table Table6 6 (ScientoMetrics-Quartile Analytics) shows the impact of the journals in which the papers have been published, ranging from Q1 to Q3.

List of the marketing analytics issues & challenges (MAICs)

Analysis and discussion

The exhaustive study of the finalised articles in terms of the issues and challenges reflected that the ethical issues and legality dimension are at the top in terms of frequency-based ranking. The ethical issues and legality involve the legal implementation of consumer rights protection in terms of privacy and usage of customer personal data. Moreover, the impact of organisational operations on consumers has to be made transparent enough so that user consent would be sought. Other issues and concerns related to implementation are concerned with the marketing analytics ecosystem.

By following the mapping and classification style of previous studies (Adams et al. 2016 ; Bembom and Schwens 2018 ; Bocconcelli et al. 2018 ; Ceipek et al. 2019 ; Klang et al. 2014 ; Nguyen et al. 2018 ; Popay et al. 2006 ; Tranfield et al. 2003 ; Zahoor et al. 2020 ), the theoretical categorisation depicts that the five literary grounds titled as RBT/RBV, Upper Echelons Theory, Organisational Learning theory, Dynamic Capability Theory/DCV, and Institutional Theory are the most influential ones in terms of constructs projected and notable research studies. This projects that the marketing analytics can be better explained by utilisation of the theoretical paradigm provided by the above, which could pave the way for further deeper studies.

Apart from the above-tabulated theories, many other theories have been employed, which include Complexity Theory (Xu et al. 2016 ; Vargo and Lusch 2017 ), Knowledge-Based View (Côrte-Real et al. 2017 ), SERVQUAL Model (Lemon and Verhoef 2016 ), Relationship Marketing Theory (Lemon and Verhoef 2016 ), Motivation-Hygiene Theory (Rutter et al. 2016 ), Supply Chain Management Theory (Schoenherr and Speier‐Pero 2015 ), Marketing Performance Measurement Theory (Järvinen and Karjaluoto 2015 ), Marketing Capability Theory (Mu 2015 ), Knowledge Management Theory (Holsapple et al. 2014 ), and Reciprocal Action Theory as well as Social Identity Theory (Chan et al. 2014 ).

Table Table6 6 depicts that 92% of the total articles (54 articles) are part of Q1–Q3 journals, where 47 studies are from Q1 journals, which means that 80% of the detail in Table Table4 4 is composed of the best available past studies based on the latest scientometrics.

For RQ2, the researchers classified the issues and challenges into the five themes depicting the core learning from this study that would pave the way for further studies:

Customer-centric strategic structures & customer engagement

The element of co-creation is apparent where organisations have to behave proactively to know what the customers want before they do, and to make them partners in seeking a competitive advantage. Consumer-based structures are being observed as the way forward for structural capitalisation that could support the information value chain (Mikalef et al. 2018 ; Sheng et al. 2017 ).

Integrated marketing communication (IMC) channels are the gateway for developing an ecosystem of customer relationship management so that targeted consumer engagement could be done for mental programming for description, diagnosis, prediction, and personalised prescription of customer lifetime experience management (Lemon and Verhoef 2016 ; Mikalef et al. 2018 ). Furthermore, for the sake of quant, the process of metrics alignment for not falling into the vicious trap of GIGO (garbage in, garbage out) marketing performance measures could be done when academia joins hands with practitioners and the foggy gap between two is cleared (Sheng et al. 2017 ). Furthermore, customer engagement in this age of personalisation is to go beyond purchase and build a platform through value exchange from and to marketer versus consumer, while assessing the psychological state of the customer in terms of participating in different initiatives of the marketer (Lemon and Verhoef 2016 ). Therefore, paving the way forward for the co-production of values through engagement platforms that are a mix of brick-n-mortar. This cycle of knowledge creation needs a mechanism of data insight extraction for actionable decision making (Xu et al. 2016 ).

For this purpose, the pre-analytics age conventional marketing strategies may not be that relevant for online brand communities, social networking sites, and consumer-based business structuring, where beyond text communication tools could be used and customers could be rewarded on their category of user (Chan et al. 2014 ). For the same reason, the concept of sharing economy and alignment of co-creation metrics to it have been considered as the key to unlocking future research and field opportunities (Kannan 2017 ).

Marketing analytics sticky culture & management practices

The system propelled culture accompanied by resource-based view (RBV) has been depicted to possess the operational grip for conversion into organisational capability. The management practices revolving around RBV categorise each factor into the classification of resources that involve data reservoirs, infrastructural foundation, and information systems installations. Process-oriented benchmarking is rehearsed, and metrics are prioritised accordingly (Mikalef et al. 2018 ). The marketing analytics sticky culture is sourced from the data-driven organisational culture where people, irrespective of their authority and hierarchical managerial positions, do indulge in decision-making practices that are backed by the informational projections extracted from data. Moreover, the data-driven management practices do mitigate silos decisions and propagate interdependency of actions (Wang and Hajli 2017 ).

In this jigsaw of data-driven marketing analytics, sticky analytics culture, and management practices, the issue of ethical consideration for usage of customer data and mix of customer consent versus reward is a nascent one that calls for further research (Martin and Murphy 2017 ).

Shifting the paradigm from RBV to knowledge-based view (KBV), Côrte-Real et al. ( 2017 ) are of the view that data analytics reservoirs are a network of knowledge-steered value chains that are not restricted to organisational boundaries and customer–marketer exchange mediums. These external value chains of knowledge that could promise operational agility and widening the business canvas are the next big thing to explore for competitive sustainability.

The ecosystem of marketing analytics is a whirl of RBV and KBV paradigms of industrialisation 4.0 where each function of marketing has its own set of analytical measurements for performance management. Therefore, further spearhead mapping of marketing-mix investment portfolios in high-tech or IT conducive environments is imperative (Lemon and Verhoef 2016 ; Wedel and Kannan 2016 ; Sheng et al. 2017 ).

As a crux, the aggressive proactive management practices for crafting system-oriented analytics sticky culture are necessary, which could integrate relevant management practices with overall business objectives (Mikalef et al. 2018 ; Chen et al. 2012 ). This would make insightful data utilisation that a management strategic priority would reflect the organisational agility phase. Moreover, an inclusively developed reservoir of management learning behaviours to re-adjust, re-align, and re-do practices could develop an indigenous culture. This could help the organisation to have capabilities that are hard to copy (Kannan 2017 ; Sheng et al. 2017 ).

Geo-location-based sense, data mining, and content management

The geo-location-based sense through social media management while taking care of the ethical issues and legality issues is vital to utilise the value from social mediums. Data-backed sense of social issues is a plus in this arena. The market strategies are to be ground in marketing core objectives, where knowledge sharing and change readiness are top of the line for the fifth revolution, marked by personalisation. The IT resource management for this shift is a major barrier that creates big data issues. This connects to the dearth of need analysis in terms of skill requirement and training/curriculum correspondents to analytics techniques and technological issues that disturb the customer experience management agenda (Wang and Hajli 2017 ; Bradlow et al. 2017 ; Martin and Murphy 2017 ; Sheng et al. 2017 ).

Surprisingly, Mobile analytics, as being the portable platform, has raised the bar for platform-free content management, where user-generated content is much valued for better acceptability. The disruption is caused in terms of customer privacy and security issues, where the race for EWOM & ROI has eroded societal sense. Therefore, counter disruptive technologies are imperative for governance, to develop dynamic capabilities for future marketing analytics (Mikalef et al. 2018 ; Sheng et al. 2017 ; Wedel and Kannan 2016 ; Chen et al. 2012 ).

Insightful data utilisation & performance measures

The need analysis of the business competition in terms of dynamic market capabilities and disruptive technological change sets the stage for alignment of the data management and valuation strategies (Mikalef et al. 2018 ). These strategies reflect the operations for data utilisation for the actionable insights as per the impact metrics defined for the communication channels where consumers exercise their consumer power. The digital orientation of marketing mix is exercised for mapping of the gaps in talent requirement, organisational agility, actionable metrics, and sharing the profits from marketing analytics with customers (Leeflang et al. 2014 ; Bradlow et al. 2017 ).

For this purpose, rigorous extraction and utilisation of data insights have been done through a deeper study of marketing data analytics for tracking the business process transformations that may indicate the untapped value reservoirs of “blue ocean” customer profits (Wang and Hajli 2017 ). Martin and Murphy ( 2017 ) stressed forwarding of profitability share to the customer through reward mechanism in this situation for a long-term relationship and value creation in marketing analytics age (Sheng et al. 2017 ). Wedel and Kannan ( 2016 ) presented the novel research methods for marketing analytics and depicted the connection between privacy and data security, marketing mix, and personalisation. Moreover, the future buying patterns of customers and exploration of developing service instruments in accordance calls for the usage of smart data snatching tools that could seamlessly apply metrics for customer tracking (Bradlow et al. 2017 ). The performance measures attached to this exercise may involve the issues of customer privacy and data security that needs to be vigilantly handled. The area of customer data security and privacy embedded with legal issues is a nascent marketing analytics arena that calls for further empirical research.

Besides, the marketing analytics heterogeneity enrichment is being in limelight through work on content marketing, web analytics, automation of marketing processes, and development of marketing analytics curriculum based on empiricism, as per pressing demand for unfathomable insight of related performance measures (Järvinen and Taiminen 2016 ; Schoenherr and Speier‐Pero 2015 ).

Ethical issues & legality

The most unique challenge for marketing analytics is composed of dimensions of business ethics and legality. The ethical issues involve intentional or unintentional customer privacy invasion through digitalised seamless data extraction and scanning mechanisms that could lead the company into a troublesome situation in terms of customer data privacy and security (Mikalef et al. 2018 ; Sheng et al. 2017 ).

With a balance between the customer privacy dynamics and organisational need, a reward system is a key to refrain from any conflicting situation. For this purpose, metrics must be aligned with the ethical consideration and legality issues. Moreover, the area of ethical issues and legality is complex as well as nascent in terms of research work. Therefore, demand for further research in terms of legal applications ranging from operations of web analytics to mobile analytics as privacy and protection of data is empirically evident (Sheng et al. 2017 ).

There are a variety of opinions and views floated by researchers in this regard. The performance benchmarks should be aligned with organisational dynamic capabilities (Mikalef et al. 2018 ) and the ecosystem for modulation of the customer-centric sharing economy (Kannan 2017 ) may be devised for customer profitability enhancement (Wang and Hajli 2017 ). Bradlow et al ( 2017 ) talked about customer tracking and ethical considerations. Martin and Murphy ( 2017 ) portrayed the ethical and legal dimensions of analytics in terms of data privacy, level of usage and sharing, and access nature. Côrte-Real et al. ( 2017 ) depicted the KBV perspective of analytics and data dynamics that broaden the scope of legal operations as the external channels of knowledge require legal scrutiny. Sheng et al. ( 2017 ) discussed convergence and divergence of various fields in connection in this regard. Lemon and Verhoef ( 2016 ) along with Wedel and Kannan ( 2016 ) talked about customer purchase behaviour tracking, personalisation, and ethical issues and legality mix in terms of marketing analytics. Schoenherr and Speier‐Pero ( 2015 ) depicted the curriculum development, empiricism, and legality depth. Mu ( 2015 ) researched marketing capability, product innovation, and novel legal complexities. Leeflang et al. ( 2014 ) studied the ethically and legality-wise proactive practices of professional marketers in the digitalised era. Furthermore, Chen et al. ( 2012 ) mobile analytics and technical areas connected with ethics and legality for preparing for the back-end processes.

The literacy thick encapsulation of 45 marketing analytics issues and challenges has been done based on theoretical significance and empirical sense into five construct-bonded layers that are customer-centric strategic structures and customer engagement, marketing analytics sticky culture, and management practices geo-location-based sense and data mining as well as content management, insightful data utilisation and performance measures, and ethical issues and legality. Together, they reflect the patterns in the high-quality literature spanning around two decades.

Moreover, all the marketing issues and challenges have been further classified into the process, people, outcome, and strategy as per the nature of the constructs explored from the literature. This further comprehends that the plethora of issues and challenges are triggered by these channels. Therefore, further research in terms of process-driven, people perspective, outcome-oriented, strategy-specified avenues of marketing analytics may support enrichment to this field brought by the fourth industrial revolution.

Limitations

The search metrics and selection process of the quality papers between the periods 2000 and 2020 have limitations as the canvas is not so wide to cater for the concept of marketing analytics issues and challenges from inception to conception, as in the case of meta-analysis. The trend of papers does reflect that the research problem is new and much of the research has been done in between the two decades, yet the systematic literature review has its limited grounds in terms of other research methodologies. So, widening the canvas of research in terms of the research period, research design, and other factors would provide deeper insight for the academic and practitioner community.

Core implications

Ethical and legal issues have been the most prominent ones, which depict that the legal acumen capability is the steering point for any company to save itself from any business-related challenges. The intangibles are the “new tangibles” for dealing with marketing analytics issues and challenges as companies have to work on their dynamic as well as inclusive capabilities of breeding co-creation culture through customer-centric strategic structures and customer engagement. This is marked by the alignment of performance measures with rigorous utilisation of actionable data insights.

Further research considerations

Marketing analytics demands a shift in the operational capabilities of the companies in terms of people, process, strategy, and outcomes. These dimensions call for further research in terms of each of the significant issues and challenges in heterogeneous industries, while setting the research canvas to regional alliances and international ones as well. This will provide a fruitful mapping reservoir for regional and international comparative analysis across various industries. Moreover, the SLRs in the area projected that areas and the learning from this study project that

- The convergence of stages of analytics (Descriptive, Diagnostic, Predictive, Prescriptive) and marketing science is a high call to check the issues and challenges at each stage.

- The reasons for significant issues and challenges, along with their remedies and territorial best practices, are composed of the broad range of research work yet to be done

- Mix methodology research has to be adapted for looking at the phenomena and defining its constructs; afterwards, those constructs should be converted into variables by scale development. Furthermore, the development of indigenous scales for each of the issues and challenges in terms of countries will provide better inclusive measurement yardsticks, which is the need of the fourth industrial revolution.

Domain classification of issues and challenges

- A systematic literature review for issues and challenges in terms of marketing metrics has been depicted by the present study.

- The common issues and challenges of marketing intelligence and marketing analytics are a vital area that would pave the way for 4.0 readiness by the developing economies.

Biographies

is a PhD Scholar at Faculty of Management Sciences, International Islamic University, Islamabad, Pakistan. He is a permanent Faculty member at Foundation University, Islamabad, Pakistan. He has taught in various public and private universities. His research interests are marketing intelligence and analytics. He has field experience in Marketing and Educational Logistics & Supply Chain Management.

is an Ex Dean at Faculty of Management Sciences, International Islamic University, Islamabad, Pakistan. He is an Ex Vice President Academics in the same university. He has more than 30 years of university teaching experience. He is research expertise in organisational behaviour and marketing science.

Abdul Zahid Zahid

is a Chairman for Department of Technology Management, International Islamic University, Islamabad, Pakistan. His research publications in reputable journals are Knowledge Management, Technology Management, Information Science, Computer and Society, and Information Systems. He has more than 20 years of university teaching experience.

is a Professor of Human Resources Management at Nova Southeastern University in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida. He is the author and co-author of several professional and academic books dealing with diversity, ethics, and management, as well as numerous academic journal articles. During the past twenty-five years, he has had the pleasure of working with human resource professionals in the United States, Canada, Brazil, Bahamas, Afghanistan, Pakistan, St. Lucia, Grenada, Malaysia, Japan, Vietnam, China, India, Thailand, and Jamaica. This diverse exposure has provided him many insights in ethics, culture, and management from the perspectives of different firms, people groups, and countries. Bahaudin can be reached at: [email protected]

Declarations

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Imran Bashir Dar, Email: [email protected] .

Muhammad Bashir Khan, Email: moc.evil@rihsabdhomrd , Email: [email protected] .

Abdul Zahid Khan, Email: [email protected] .

Bahaudin G. Mujtaba, Email: ude.avon@abatjum , Email: ude.avon@abaatjum , https://www.nova.edu .

- Adams R, Jeanrenaud S, Bessant J, Denyer D, Overy P. Sustainability-oriented innovation: A systematic review. International Journal of Management Reviews. 2016; 18 (2):180–205. doi: 10.1111/ijmr.12068. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Amado A, Cortez P, Rita P, Moro S. Research trends on Big Data in marketing: A text mining and topic modeling based literature analysis. European Research on Management and Business Economics. 2018; 24 (1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.iedeen.2017.06.002. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Archak N, Ghose A, Ipeirotis PG. Deriving the pricing power of product features by mining consumer reviews. Management Science. 2011; 57 (8):1485–1509. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.1110.1370. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baker JD. The purpose, process, and methods of writing a literature review. AORN Journal. 2016; 103 (3):265–269. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2016.01.016. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Balis, J. 2020. Brand marketing through the coronavirus crisis. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved February 12, 2020, from https://hbr.org/2020/04/brand-marketing-through-the-coronavirus-crisis

- Baltes LP. Content marketing-the fundamental tool of digital marketing. Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Brasov. Economic Sciences. Series. 2015; 8 (2):111–118. [ Google Scholar ]

- Banerjee A, Bandyopadhyay T, Acharya P. Data analytics: Hyped up aspirations or true potential? Vikalpa. 2013; 38 (4):1–12. doi: 10.1177/0256090920130401. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barger VA, Labrecque L. An integrated marketing communications perspective on social media metrics. International Journal of Integrated Marketing Communications. 2013; 2 :64–76. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bembom M, Schwens C. The role of networks in early internationalizing firms: A systematic review and future research agenda. European Management Journal. 2018; 36 (6):679–694. doi: 10.1016/j.emj.2018.03.003. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bocconcelli R, Cioppi M, Fortezza F, Francioni B, Pagano A, Savelli E, Splendiani S. SMEs and marketing: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Management Reviews. 2018; 20 (2):227–254. doi: 10.1111/ijmr.12128. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bradlow ET, Gangwar M, Kopalle P, Voleti S. The role of big data and predictive analytics in retailing. Journal of Retailing. 2017; 93 (1):79–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jretai.2016.12.004. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Breugelmans E, Bijmolt TH, Zhang J, Basso LJ, Dorotic M, Kopalle P, Wünderlich NV. Advancing research on loyalty programs: A future research agenda. Marketing Letters. 2015; 26 (2):127–139. doi: 10.1007/s11002-014-9311-4. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ceipek R, Hautz J, Mayer MC, Matzler K. Technological diversification: A systematic review of antecedents, outcomes and moderating effects. International Journal of Management Reviews. 2019; 21 (4):466–497. doi: 10.1111/ijmr.12205. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chan TK, Zheng X, Cheung CM, Lee MK, Lee ZW. Antecedents and consequences of customer engagement in online brand communities. Journal of Marketing Analytics. 2014; 2 (2):81–97. doi: 10.1057/jma.2014.9. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chang RM, Kauffman RJ, Kwon Y. Understanding the paradigm shift to computational social science in the presence of big data. Decision Support Systems. 2014; 63 (7):67–80. doi: 10.1016/j.dss.2013.08.008. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen H, Chiang RH, Storey VC. Business intelligence and analytics: From big data to big impact. MIS Quarterly. 2012; 36 (4):1165–1188. doi: 10.2307/41703503. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Côrte-Real N, Oliveira T, Ruivo P. Assessing business value of Big Data analytics in European firms. Journal of Business Research. 2017; 70 (1):379–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.08.011. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dam NAK, Le Dinh T, Menvielle W. Marketing Intelligence from Data Mining Perspective. International Journal of Innovation, Management and Technology. 2019; 10 (5):184–190. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dasan P. Small & medium enterprise assessment in Czech Republic & Russia using marketing analytics methodology. Central European Business Review. 2013; 2 (4):39–49. doi: 10.18267/j.cebr.63. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Davenport TH. Competing on analytics. Harvard Business Review. 2006; 84 (1):98. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Davenport TH, Harris JG. Competing on Analytics. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- Davenport T, Harris J. Competing on analytics: Updated, with a new introduction: The new science of winning. Boston: Harvard Business Press; 2017. [ Google Scholar ]

- Davenport TH, Harris JG, Morison R. Analytics at work: Smarter decisions, better results. Boston: Harvard Business Press; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Davenport TH, Kim J. Keeping up with the quants: Your guide to understanding and using analytics. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press; 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- Duan L, Xiong Y. Big data analytics and business analytics. Journal of Management Analytics. 2015; 2 (1):1–21. doi: 10.1080/23270012.2015.1020891. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dwivedi YK, Kapoor KK, Chen H. Social media marketing and advertising. The Marketing Review. 2015; 15 (3):289–309. doi: 10.1362/146934715X14441363377999. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Farris PW, Bendle N, Pfeifer PE, Reibstein D. Marketing metrics: The definitive guide to measuring marketing performance. London: Pearson Education; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- France SL, Ghose S. Marketing analytics: Methods, practice, implementation, and links to other fields. Expert Systems with Applications. 2019; 119 (5):456–475. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2018.11.002. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frizzo-Barker J, Chow-White PA, Mozafari M, Ha D. An empirical study of the rise of big data in business scholarship. International Journal of Information Management. 2016; 36 (3):403–413. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2016.01.006. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- George G, Osinga EC, Lavie D, Scott BA. Big data and data science methods for management research. Academy of Management Journal. 2016; 59 (5):1493–1507. doi: 10.5465/amj.2016.4005. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Germann F, Lilien GL, Rangaswamy A. Performance implications of deploying marketing analytics. International Journal of Research in Marketing. 2013; 30 (2):114–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ijresmar.2012.10.001. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ghose A, Han SP. Estimating demand for mobile applications in the new economy. Management Science. 2014; 60 (6):1470–1488. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.2014.1945. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ghose A, Ipeirotis PG, Li B. Designing ranking systems for hotels on travel search engines by mining user-generated and crowdsourced content. Marketing Science. 2012; 31 (3):493–520. doi: 10.1287/mksc.1110.0700. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ghose A, Yang S. An empirical analysis of search engine advertising: Sponsored search in electronic markets. Management Science. 2009; 55 (10):1605–1622. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.1090.1054. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goldfarb A, Tucker C. Online display advertising: Targeting and obtrusiveness. Marketing Science. 2011; 30 (3):389–404. doi: 10.1287/mksc.1100.0583. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goldfarb A, Tucker CE. Privacy regulation and online advertising. Management Science. 2011; 57 (1):57–71. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.1100.1246. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Grigsby M. Marketing analytics: A practical guide to real marketing science. London: Kogan Page Publishers; 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- Guercini S. Editoriale: The actor or the machine? The strategic marketing decision-maker facing digitalization. Micro & Macro Marketing. 2020; 29 (1):3–7. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hanssens DM, Pauwels KH. Demonstrating the value of marketing. Journal of Marketing. 2016; 80 (6):173–190. doi: 10.1509/jm.15.0417. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Harrigan P, Hulbert B. How can marketing academics serve marketing practice? The new marketing DNA as a model for marketing education. Journal of Marketing Education. 2011; 33 (3):253–272. doi: 10.1177/0273475311420234. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Harris L, Rae A. Social networks: The future of marketing for small business. Journal of Business Strategy. 2009; 30 (5):24–31. doi: 10.1108/02756660910987581. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Harris L, Rae A. Building a personal brand through social networking. Journal of Business Strategy. 2011; 32 (5):14–21. doi: 10.1108/02756661111165435. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Harzing, A.W. 2007. Publish or perish [computer software] https://harzing.com/resources/publish-or-perish . Accessed 19 Feb 2020.

- Hauser WJ. Marketing analytics: The evolution of marketing research in the twenty-first century. Direct Marketing: An International Journal. 2007; 1 (1):38–54. doi: 10.1108/17505930710734125. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hedges, L. V., and Cooper, H. 2009. Research synthesis as a scientific process. The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis , 1 . Russell Sage Foundation. New York

- Hofacker CF, Malthouse EC, Sultan F. Big data and consumer behavior: Imminent opportunities. Journal of Consumer Marketing. 2016; 33 (2):89–97. doi: 10.1108/JCM-04-2015-1399. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Holsapple C, Lee-Post A, Pakath R. A unified foundation for business analytics. Decision Support Systems. 2014; 64 (8):130–141. doi: 10.1016/j.dss.2014.05.013. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]