An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Health Serv Res

A systematic scoping review of change management practices used for telemedicine service implementations

1 UQ Business School, The University of Queensland, Colin Clark Building 39 Blair Drive, St Lucia, Brisbane, QLD 4072 Australia

Nicole Gillespie

Melinda martin-khan.

2 Centre for Health Services Research, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia

Associated Data

Not applicable

Telemedicine improves access to health care services enabling remote care diagnosis and treatment of patients at a distance. However, the implementation of telemedicine services often pose challenges stemming from the lack of attention to change management (CM). Health care practitioners and researchers agree that successful telemedicine services require significant organizational and practice change. Despite recognizing the importance of the “people-side” of implementation, research on what constitutes best practice CM strategies for telemedicine implementations remains fragmented, offering little cohesive insight into the specific practices involved in the change process. We conducted a systematic scoping review of the literature to examine what and how CM practices have been applied to telemedicine service implementation, spanning a variety of health care areas and countries.

Three bibliographic databases (CINAHL, PubMed, and ISI Web of Science) and four specialist telehealth journals were searched. To keep the review manageable and relevant to contemporary telemedicine technologies and contexts, the search was limited to articles published from 2008 to 2019. Forty-eight articles were selected for inclusion.

From the 48 articles, 16 CM practices were identified relating to either strategic or operational aspects of telemedicine implementations. We identify the key CM practices that are recognized in the broader CM literature as essential for successful and sustained change but are not commonly reported in telemedicine implementation studies. We draw on the CM literature to provide a comprehensive process-based, researched-informed, organizing framework to guide future telemedicine service implementations and research.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that the slow rate of adoption of telemedicine may be due to a piecemeal approach to the change process, and a lack of understanding of how to plan, manage and reinforce change when implementing telemedicine services.

Over the past few decades, health care organizations have been undergoing significant organizational and practice change to incorporate information communication technologies (ICTs), with the aim of reducing costs, improving quality, increasing efficiency and effectiveness and raising patient or client satisfaction [ 1 , 2 ]. The incorporation of telemedicine services is a prominent example of such change. Telemedicine is the delivery of health care services using ICTs as a substitute for traditional face-to-face interactions between patient and provider, enabling the remote care, diagnosis and treatment of patients at a distance [ 3 ]. Telemedicine is increasingly valued for providing health care services to patients, either for those with limited access to specialist assessment or management of care needs due to remoteness, convenience or managing patient flow [ 4 ].

The use of telemedicine has increased significantly over time [ 5 ], however, research on telemedicine uptake indicates it still remains low as a percentage of all care, with high rates of non-participation by different stakeholders [ 6 , 7 ]. While limited reimbursement and current licensure laws pose barriers to the widespread use of telemedicine [ 8 , 9 ] slow adoption has also been attributed to human factors [ 10 , 11 ], organizational issues [ 12 , 13 ] and cultural barriers [ 14 ]. The success of telemedicine rests not only on resolving technical, regulatory and financial issues but also on the management of human and organizational change [ 15 ]. Successful long- term implementation requires sustained resolution of all these factors concurrently.

Change management (CM) is often recognized as integral to the implementation of telemedicine [ 16 , 17 ], yet is often approached in an ad-hoc, sporadic and reactive way, and reported as “lessons learned” when retrospectively evaluating a service implementation [ 15 , 18 , 67 ]. CM takes a systematic approach based on “an enabling framework for managing the people side of change” [ 19 ] that involves a set of processes, practices and deliberate activities intended to facilitate and guide an organization to move from its present state to a desired future state [ 20 ].

Researchers studying telemedicine implementation typically frame their understanding of the challenges and factors influencing uptake by identifying and listing “barriers” and “enablers” [ 21 , 22 ]. For example, some enablers cited are the development of organizational protocols, adequate funding and support, user training plans and change management plans [ 16 ]. Common barriers reported are lack of technological compatibility, resistance to change, lack of adequate reimbursement, lack of usability and medico-legal and liability concerns [ 8 , 16 ]. The assumption underlying this work is that telemedicine adoption can be achieved by increasing the enablers and reducing the barriers [ 22 ]. Yet, many barriers to telemedicine remain stable over time, with studies continuing to report the same barriers with little signs of improvement [ 23 ].

Some authors have focused on tools to assess telemedicine ‘readiness’ [ 24 ] or constructed models to explain clinician ‘acceptance’, recognising that clinician acceptance has the greatest influence on uptake and sustainability [ 25 ]. While these current telemedicine change acceptance and readiness tools and models are helpful, a limitation is that they do not account for or guide the process of change involved in implementing and adopting telemedicine services. Furthermore, because most telemedicine studies reported in the literature involve trials, feasibility studies or pilots [ 17 , 23 , 26 ], the focus is on short-term adoption and project management, or the technical side of implementing telemedicine services (i.e., technical aspects that show how to design, develop and deliver a service) [ 23 ].

As telemedicine is a “key solution to resolve both contemporary and future challenges in health care and social care” [ 17 ], there exists a number of guidelines, implementation resources and tool kits aimed to facilitate the implementation of telemedicine solutions [ 17 , 27 ]. For example, a ‘MOMENTUM’ report put together by various European interest groups and stakeholders, identifies 18 critical successful factors to guide the deployment of telemedicine in routine delivery of health services on a large scale [ 17 ]. Similar to most guidelines and recommendations, ‘preparing and implementing a CM plan’ is considered a critical success factor. However, due to limited understanding of what CM is and how to apply it, CM plans are often poorly executed or not implemented at all.

While the importance of CM for successful telemedicine implementation is known [ 13 , 16 , 17 , 28 ], the literature on CM application in telemedicine remains fragmented, lacking consolidated detail about how they are applied, the frequency of practices used, and the outcomes produced when guiding and implementing change. In other words, the literature on telemedicine services lacks an integrated framework that provides cohesive learning and insight about CM practices reported in telemedicine implementation studies. Such a review and synthesis of extant literature is important for informing and advancing theory, research and practice on the effective implementation of telemedicine services.

Therefore, this study aims to: (1) identify what CM practices have been applied to the implementation of telemedicine services; (2) identify the frequency of the CM practices reported; (3) provide a CM practice framework specific for telemedicine implementations and; (4) identify the gaps in the current CM approach to implementing telemedicine, as reported by existing literature, by comparing it to the broader CM literature.

To assess the CM practices used for implementing telemedicine services we conducted a scoping study of the avaliable research literature. While keeping our search broad, we aimed to conduct a comprehensive, reproducible, and systematic search of published literature. Scoping reviews involve five steps or stages: (1) identifying the research question/s; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting the data; and (5) collating, summarizing and reporting the results [ 29 ]. We followed Arksey and O’Malley’s [ 29 ] approach guided by Tricco and colleagues’ PRISMA-ScR checklist (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) [ 30 ]. As scoping reviews are not eligible for registration or inclusion in databases of systematic review protocols [ 31 ], we first reviewed existing telemedicine literature to find that no other published scoping or systematic review focused on our topic of interest. Performing a scoping study was a useful way of mapping key concepts that underpinned our research topic that had not been comprehensively reviewed [ 32 , 33 ].

Identifying relevant studies

We conducted a search of the peer-reviewed literature using three electronic bibliographic databases: CINAHL, PubMed, and ISI Web of Science. In addition, we searched the four most cited telehealth journals: Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, Telemedicine Journal and e-Health, Telemedicine and e-Health, and Telemedicine Journal (the last three journals all sourced via Mary Ann Liebert Publishers Journals database) . Reference lists of included articles were also systematically searched, for additional relevant studies. The search strategy, terms and database selection were reviewed and determined in consultation with a university librarian (with expertise in literature reviews and searches), and the third author (an experienced health scientist and health administrator). When applicable, expanders were used to broaden the scope of our search. A broad range of search terms associated with our topic were used, guided in part by the MeSH heading terms (and associated entry terms) of Telemedicine, Change Management and Pilot Projects. Table 1 outlines the search strategy and terms used for each database and journal. During pilot testing of the search strategy, some terms or phrases (such as “attitude” and “attitude to change”) were removed from the final search because the term was either not useful (i.e., did not generate any additional studies) or could not be found in some databases.

Search strategy by database and journals

To keep the review manageable and reflective of current issues concerning contemporary technology, telemedicine services and organizational contexts, the search was limited to articles published between January 2008 and June 2019. We also applied limiters in order to select papers written in the English language and that were peer-reviewed. Articles obtained through our search were imported and stored in Endnote (a reference management software used to manage references) for screening.

Study selection

Peer-reviewed, empirical articles were reviewed if they met the following criteria: (1) examined health care services using ICTs (e.g., videoconference or store-and-forward systems) that enable virtual interactions between patient and provider (e.g., medical and allied health practitioners) for remote care, diagnosis and/or treatment of patients at a distance; (2) reported or described the evaluation of pilot studies and/or implemented telemedicine services and; (3) referred to the use of CM strategies during the implementation and adoption of services. Literature reviews, systematic reviews, conceptual papers and discussion pieces were excluded; however, their reference lists were reviewed for relevant empirical studies. Similarly, reference lists of articles mentioning some form of telemedicine service were also reviewed for additional sources. Conference and poster abstracts and news articles were excluded during the screening process. Team discussions with all authors were held throughout the review process to discuss decisions regarding the study inclusion and exclusion list, which was refined accordingly based on the abstracts and full articles retrieved from the search.

During the identification process, the first author JK independently reviewed titles, abstracts and full articles by categorizing each article into an ‘included’ or ‘excluded’ group. Papers that clearly met the inclusion criteria based on title and abstract review were subjected to a full text review and on this basis sorted into the included or excluded group. Articles that did not clearly meet the inclusion criteria or where the reviewer was uncertain about its eligibility were set aside for team discussions with all authors. Specifically, questions and challenges regarding article eligibility and uncertainty in the application of the inclusion criteria were resolved through further review and discussion by the authors until consensus was reached. Several team meetings were held throughout the review process to resolve ambiguity related to study selection and to ensure that full articles were relevant for inclusion.

Data charting process

Following the framework of Arksey and O’Malley [ 29 ], we extracted data to inform our research aims using NVivo 12, a qualitative data analysis software designed to help organize, store and analyse data. Included articles were imported into NVivo. General information about each article was then charted [ 29 ] and was categorized into specific ‘codes’ or categories. Data included the author(s), year of publication, type of telemedicine service, modality (e.g., video conference) and country of implementation, as well the outcome of the implementation (e.g., successful or not successful). The frequency of CM practices reported for each study was also recorded.

We then analyzed the included articles that reported specific CM practices used when implementing telemedicine services. We extracted CM activities relating to the facilitation of telemedicine implementation, which corresponded with the 10 change steps commonly associated with prescriptive change models [ 20 ]. Each identified CM activity was then clustered and coded into broader categories, resulting in a total of 16 specific change practices. Guided by the causal model of organizational change developed by Burke and Litwin (1992), we noted that CM practices identified in our analysis related to either transformational factors of change involved with strategy and leadership or; transactional factors concerned with the day-to-day operations of a change [ 34 ]. As such, we further categorized these practices as: 1) strategic practices : practices used to direct and promote change and build alliances when implementing telemedicine services; or 2) operational practices : practices used to manage the impact of the change on the day-to-day operations of telemedicine services.

In line with the recommendations from Arksey and O’Malley [ 29 ], we did not assess the methodological quality of the included studies. Scoping reviews are less restrictive than systematic reviews enabling a broader range of study designs to be included, rather than limiting inclusion based on research quality [ 29 , 33 ]. Importantly, given the heterogeneity of the existing evidence base of the field, and the fact that the large majority of studies are written as programme descriptions and case reports, a formal quality criteria could not be applied [ 35 ].

Synthesis of results

Guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s approach [ 29 ], an analytical framework was used to collate and present our findings. First, we created a data table (i.e., Table 2 ) for our study characteristics (i.e., author(s), year of publication etc.).

Characteristics of selected studies

Abbreviations : VC Videoconferencing systems, S Successful, S&F Store and forward systems, NS Not successful, RM Remote monitoring, NR Not reported, T Telephone

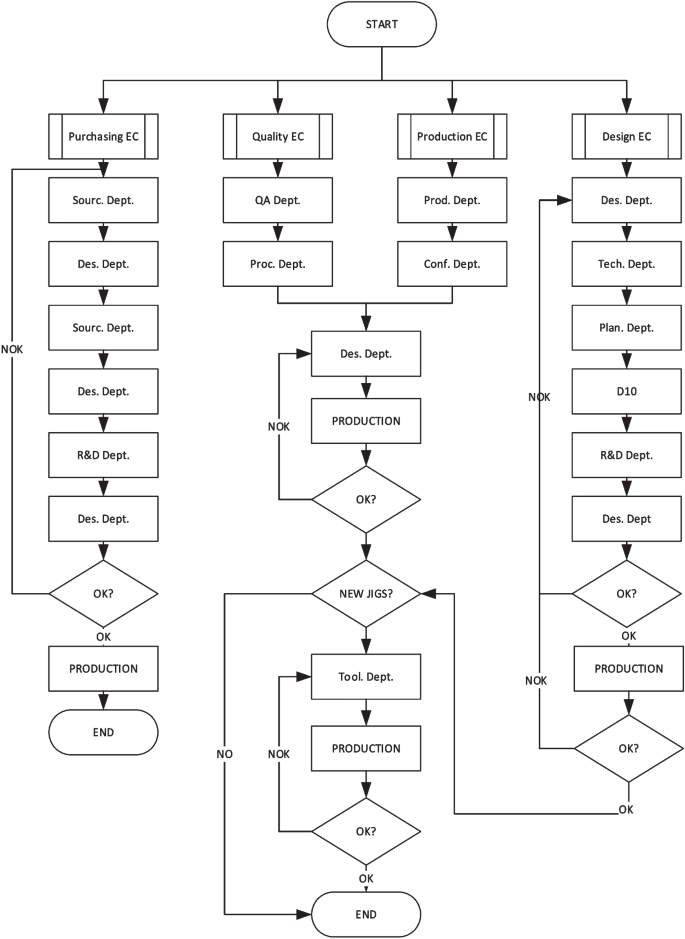

Second, we developed a figure that captured a consolidated overview of the CM practices that were identified in our review and matched each one to a corresponding change step commonly associated with established prescriptive change models. We then organized the CM practices further to show whether they were associated with either strategic or operational practices. A process approach for organizational change [ 20 ] was then depicted, by organizing the change steps and strategic and operational CM practices using the Prosci 3-Phase Change Process – preparing for change , managing change and reinforcing change [ 19 ]. Figure 1 helped us to identify which CM practice/s had been commonly neglected, thus identifying gaps in the current approach to implementing telemedicine, as reported in the existing literature (i.e., addressing research aims three and four).

Change management process and practices reported in telemedicine service implementation studies. *Adapted from [ 20 ]

Third, we produced another table that provided examples associated with each CM practice identified in our review to show how a specific practice was used. We also included the studies which referenced each CM practice to show the frequency of the CM practice reported in literature. Table 3 thus addressed aims one and two.

Summary table of change management practices reported in telemedicine literature with examples and related articles that refer to its application

Article numbers presented in this table aligns with the studies identified in this review listed in Table 2

Collectively, this approach provided a consolidated overview of what is known about CM practices for implementing telemedicine services.

Main characteristics of the selected articles in review

The database search resulted in 798 articles. Additional articles ( n = 9) identified through other sources (e.g., reference lists) were added. As shown in Fig. 2 , after removal of duplicates, the number of articles reduced to 657 articles. If the abstract met the eligibility criteria or if the relevance of the study was unclear from the abstract, then a full-text review was completed. A total of 231 full-text articles were reviewed and 183 of these articles were excluded, retaining 48 articles for analysis. The selected studies were then stored, coded and managed using NVivo 12. As explained in detail in Fig. 2 , common reasons for study exclusion included: (1) articles focused on social or economic changes, or individual-level or patient changes in health behaviors, and patient or clinical outcomes; (2) articles that explored change recipients’ perspectives and experiences regarding the barriers or challenges before and during the implementation process with no mention of how these barriers were addressed by using change management practices; (3) guidelines, recommendations or specific strategies that were mentioned in hindsight or as ‘lessons learned’, thus not a ‘tried and tested’ CM practice or applied in practice during an implementation of a telemedicine service, which was the focus of our review.

Schema portraying results of the literature search and selection for inclusion

The majority of telemedicine service implementations reported in the literature were from the United States of America (46%), followed by Australia (17%), Asia (10%), Europe (8%) and the rest from South America, Canada and Africa (6% each). Most studies were based on real-time telemedicine, such as videoconferencing (VC) systems (54%). Others delivered services through a mix of VC and store-and-forward (S&F) systems (17%), VC and remote monitoring (RM) (8%) and VC and phone (1 study). While the rest used RM only (4%), S&F delivery only (13%) and phone only (1 study). The selected articles identified in this review reported on a range of specialist services, with 12 studies focusing specifically on mental health services (e.g., psychiatric and neurological services), while other articles focused on primary care, palliative care, surgical care, intensive care, nephrology, pathology, pediatrics, dermatology and geriatric care services. Table 2 shows a summary of study characteristics.

The most CM practices mentioned in a single study was 13/16 [ 55 ]; two studies included 12/16 CM practices [ 37 , 65 ]; seven studies reported between 10 and 11 practices, 15 studies mentioned six to nine practices; while the remaining studies ( N = 23) reported one to five practices used to implement change (see Table 2 ).

Of the 48 studies included in this review, 32 (84%) articles reported successful outcomes, suggesting that telemedicine services were successful and ongoing during the time of the study and/or services had since expanded to other regions or sites. Five studies (13%) did not report on success or whether trials progressed past the pilot stage or evolved to an ongoing service. Only two studies in this review reported a non-successful outcome due to poor uptake of services and a depletion of funding, resulting in declined use by both clinicians and patients [ 65 , 73 ] (see Table 2 ).

Change management practices identified in review

Phase 1. preparing for change – strategic practices.

Our review identified five strategic practices that are important during the preparatory phase of the change process. These practices centred on selecting and supporting a guiding change coalition and formulating a clear compelling vision.

Establish plans

Fourteen of 48 studies reported on the importance of planning for the establishment of telemedicine services. Strategic planning involved the collaboration of a number of key stakeholders (i.e., clinicians, nursing staff, management, technical staff, implementers) through regular ongoing meetings [ 64 ]. Provider (e.g., clinicians and nurses) participation in the planning and design of the system was a major contributor to successful implementation, partly because it facilitated ownership of the program during the planning stage [ 59 ].

Gain leadership and management support and commitment

In 31 % ( N = 15/48) of studies, leadership or management support and commitment were identified as vital factors for success and sustainability [ 55 , 58 , 76 ]. Obtaining management support for a telemedicine program and formal commitment from leaders was important as part of the preparation for change, especially before allocating resources for implementation [ 62 , 75 ]. The alignment between administrative and clinical leadership was also deemed important for success [ 82 ]. Engaging in frequent communication with leaders throughout the change process is reported to be critical to maintain implementation “buy-in” and also helped tailor implementation strategies [ 60 ].

Identify champions

Telemedicine champions are described as “enthusiastic individuals who initiate and promote the uptake of telehealth services” [ 22 ]. A little under a third ( N = 15/48) of the studies in our review reported that telemedicine champions are essential to securing successful telemedicine participation and uptake. These telemedicine champions played a role in promoting (e.g., awareness and education through example) [ 37 , 55 ] and legitimized telemedicine, as well as building relationships with various stakeholders [ 58 , 59 , 74 ]. Selecting key staff members who were willing to actively participate in telemedicine programs and fundamentally believe in the concept of telemedicine was found to influence other people as well as support buy-in [ 59 ]. However, a few studies reported a drop in telemedicine activity when these champions left the role or organization [ 37 ], suggesting that the reliance on a sole champion in uptake may be detrimental to the long-term development and sustainability of telemedicine services [ 45 ].

Engage partners and stakeholders

Clinical providers, staff and administrators in health organizations typically have high workloads and multiple competing priorities, which influenced their engagement in new projects [ 49 ]. Yet, engaging key stakeholders at the beginning of a telemedicine implementation project, and bringing them together to understand the current need for, and challenges of, implementing telemedicine services was a necessity [ 38 , 44 , 48 , 49 ]. Half ( N = 24/48) of the articles in our review identified the involvement or engagement of key partners and stakeholders during the establishment of telemedicine projects or services. Engaging stakeholders (i.e., nurses, clinicians) in the design process of the system also facilitated ownership of the service [ 48 ]. Frequent communication with sites through emails, regular phone calls, in-person visits and attending formal and informal community conferences was found to help gain stakeholder involvement in new services [ 49 ]. Engagement involved building relationships, collaborations and alliances with a range of stakeholders including local communities, outlying clinics, external partners (e.g., regional and national health authorities or government agencies) and telemedicine experts [ 44 , 48 , 59 , 67 , 74 ].

Develop and articulate a clear, simple vision

Six studies mentioned developing a specific vision for the telemedicine service. One study reported having a long-term vision for a pilot project [ 38 ], others mentioned having a clear and simple vision as a key factor for successful implementation of telemedicine [ 55 , 66 ]. Having a vision shared by different partners and stakeholders also helped facilitate the change [ 79 ].

Phase 1. Preparing for change – operational practices

In addition to these strategic practices, four operational practices have been identified as important for optimal telemedicine implementation. The first two practices provide an understanding of how to assess the opportunity or problem motivating the change; while the next two practices relate to the operational side of selecting and supporting a guiding change coalition.

Conduct a needs assessment

Fifteen studies reported the importance of conducting a needs assessment before tackling a complex intervention such as telemedicine. Understanding the characteristics, needs and expectations of telemedicine was important for designing a telemedicine solution that is compatible with end users, providers and the organization [ 44 , 49 ]. Paying attention to the context and needs of clinics and providers was important when tailoring the implementation strategy [ 60 , 72 ]. This process involved engaging stakeholders [ 81 ], as well as evaluating organizational readiness and the readiness of each partnering site, which provided the groundwork for understanding the needs of the organization [ 37 , 72 ].

Assess compatibility of telemedicine equipment and applications

Ten studies reported the importance of assessing the compatibility of telemedicine when implementing new services. This practice took into account the other services being provided, the existing infrastructure and technology and the appropriate location for the equipment, as well as assessing the compatibility of telemedicine solutions with local work practices and processes [ 42 , 45 , 55 , 67 , 75 ]. This practice was found to be key determinants of the acceptance and effective integration of telemedicine into usual work processes [ 42 ].

Assign coordinating roles

Poor coordination and scheduling between local and distant sites are frequent and serious issues that undermine the establishment of telemedicine services [ 57 ]. Having assigned telemedicine coordinators at both participating telemedicine sites to aid connections during clinics significantly contributed to the success and greater use of telemedicine initiatives [ 37 , 71 ]. Twenty studies identified the importance of coordinators for facilitating telemedicine services. Coordinators played an important role in preparing the organization for change [ 43 , 51 ], scheduling and integrating telemedicine activities into clinical workflow patterns [ 56 ], liaising with participating stakeholders [ 49 ], troubleshooting technical issues [ 18 , 56 ] and overseeing quality control of the service [ 56 ]. Frequent communication with telemedicine coordinators was shown to be vital in sustaining a telemedicine program, with one study reporting that telemedicine services ceased when the coordinator left [ 37 ]. Successful long-standing telemedicine programs normally included formally defined role descriptions that clearly specify telemedicine work duties, indicating that telemedicine is a formal part of regular work routines [ 44 ].

Ensure adequate resources

Workplace readiness for a new telemedicine system requires having adequate resources to support the telemedicine services. Fifteen of 48 studies identified the need for additional resources when integrating telemedicine services into existing practices. Studies often reported that telemedicine consultations require more resources than conventional consultations [ 42 , 55 ], including additional time for nurses to prepare and participate in teleconsultations. In most cases, it was necessary to complete a formal workflow analysis to assign the appropriate number of staff members to support a new telemedicine service. This included technical support [ 45 , 61 ], help-desk support [ 80 ] and administrative support [ 55 ].

Phase 2. Managing change – strategic practices

Five strategic practices were identified for managing the change. These practices focused on communicating the vision about a telemedicine service, mobilizing energy for change, empowering others to act and monitoring and strengthening the change process.

Communicate changes and understanding of telemedicine

Almost 50 % of the reviewed articles identified communication and/or dissemination of information about the changes and the benefits and limitations of telemedicine which was required in establishing a new service. Communication included sharing successful examples of telemedicine programs by conducting demonstrations or presentations to key stakeholders [ 36 , 59 ] to convey the benefits and limitations of it [ 40 , 42 ]. Participants of telemedicine projects also reported that providing information such as background information, clinical protocols and contact information as to be very useful for planning and implementing telemedicine clinics [ 42 ]. Raising community or population awareness was another suggested communication strategy to address resistance and sustain telemedicine services [ 40 , 45 , 68 ]. Understanding and realizing the benefits and advantages of telemedicine was understood to contribute to the success of a telemedicine program [ 40 , 42 ].

Gain stakeholder trust, acceptance and buy-in

Half of the telemedicine studies ( N = 24/48) reported provider, patient/user and community trust, acceptance and buy-in as key elements in establishing services, which directly impacted on the success or failure of a telemedicine service [ 54 , 57 ]. Trust was relevant in multiple referents including in the technology being used [ 42 ], the trusting relationships amongst those providing the service, as well as trust of users and patients in the service [ 55 , 61 ]. Establishing face-to-face relationships with rural community providers through site visits and starting conversations and talking through concerns about telemedicine generated trust among stakeholders [ 61 , 62 , 70 ]. Similarly, meetings with management, clinical and evaluation staff to address concerns and issues about the change were also useful practices to gain acceptance, trust and buy-in [ 43 , 60 ]. Site visits also enhanced specialists’ understanding of the local clinical context [ 70 ] by learning about the cultural needs, historical, legal and political issues unique to specific communities [ 42 , 49 ]. As confidence and familiarity was gained with the system, providers and patients were more likely to accept telemedicine as another modality for clinical consultations [ 37 , 41 , 42 ].

(Continue to) Engage partners and stakeholders

A few studies ( N = 7/48) noted that ongoing engagement of key stakeholders throughout the change process was important to re-affirm the true value of the project, to gain regular feedback and provided an opportunity to discuss the challenges involved [ 43 , 49 , 64 , 81 ].

Facilitate ownership of the service

A small number of studies ( N = 8/48) identified the importance of ensuring ownership of a telemedicine service. One study noted that providing hospitals with the freedom of when and how the telemedicine service would be utilized, facilitated local ownership of the program [ 43 ]. Empowering others by engaging them in a shared leadership role also facilitated the ownership of a service [ 66 ].

Monitor change and maintain flexibility

Continuous or periodic feedback through reporting systems or regular meetings was identified as important for monitoring the change and refining the service offering ( N = 23/48). These practices enabled clinical teams involved in telemedicine to tailor the services to meet clinical needs and continuously improve the program [ 75 , 81 ]. Paying attention to the context and needs of clinics and providers was important when tailoring the implementation strategy and facilitated the adjustment of resources [ 60 ]. Maintaining flexibility involved an iterative process between the stakeholders (e.g., facilitators, providers and coordinators) to tailor the service [ 60 , 63 ]. These practices involved trial-and-error (e.g. what technologies to use and different clinic work pathways) and acceptance of mistakes when implementing a plan [ 63 , 78 ].

Phase 2. Managing change – operational practices

Two operational practices have been identified as crucial for managing the change, which related to developing and promoting change-related knowledge and ability. Providing training and education, as well as developing work protocols and processes facilitated work related changes.

Provide training and education

Providing training and education was identified as central to successful telemedicine adoption in the majority ( N = 33/48) of articles reviewed. Training was normally delivered during the implementation of telemedicine to ensure maximum utility [ 50 , 56 , 78 ]. Training included how to use and troubleshoot equipment [ 46 , 49 ] and how to perform consultations through the technology [ 52 , 80 ]. Ongoing training and regular site checks were required to maintain telemedicine programs, especially in facilities with high staff turnover [ 41 , 53 , 67 ]. When dealing with rural and remote communities, cultural factors and communications styles also informed the training initiatives for providers [ 49 ].

Develop new work processes, protocols and procedures

The majority of articles ( N = 31/48) also identified the need to develop new workflow processes, guidelines, and clinical protocols when implementing telemedicine services [ 40 , 42 , 43 , 47 ]. These studies highlighted that it was necessary to customize or change existing workflow to accommodate the use of telemedicine [ 36 , 49 , 68 ]. Clear communication of protocols and guidelines between sites [ 57 ] and having adequate telemedicine information to develop clear precise operating procedures [ 42 , 44 ] were considered critical to success. Linkages between traditional and new work models of service delivery contributed to the integration of telemedicine [ 45 ].

Phase 3. Reinforcing change – strategic practices

Two strategic practices were identified in this review to help sustain long-term change. These included practices that related to institutionalizing the change.

This practice ( N = 7/48) emphasized the need to continue engaging partners and stakeholder throughout the change process. Preparing interim reports about the telemedicine services (e.g., number of consultations) [ 38 ], having ongoing meetings to discuss the progress of the program [ 49 , 81 ], as well as providing ongoing training and education [ 67 ] were ways to continue engaging stakeholders to reinforce the change.

Evaluate the changes and maintain flexibility

To ensure the sustainability of telemedicine programs, a number of studies ( N = 14/48) reported the need to evaluate the service after the preliminary implementation stage. Obtaining ongoing feedback from users helped refine the usability of telemedicine and the maintenance of compatibility of the technology and applications with the organisational needs in the long term [ 77 ]. Evaluating the change was done through provider and patient/staff feedback and satisfaction ratings, reviewing work-flow output, evaluating patient outcomes, quantification of the efficiency and assessing the capacity of telemedicine operations, as well as conducting a cost analysis [ 38 , 39 , 49 , 57 ].

Figure 1 shows our CM practice framework, which captures a consolidated overview of the CM practices identified in our review. It depicts a process approach in preparing, managing and reinforcing change, which shows the ongoing work and process to sustain a new telemedicine service through a suite of CM practices used by various health care practitioners.

This scoping review brings together for the first time a comprehensive picture of the different ways practitioners have applied CM practices when implementing telemedicine services. Table 3 presents a summary of CM practices and examples reported in the telemedicine literature in this review, as well as the identified articles that mention the application of CM practices.

Through our review, we draw out three key insights that contribute to the literature on telemedicine implementation. First, most practitioners only considered CM practices retrospectively after particular issues had emerged, indicating a reactive orientation to dealing with implementation issues. A reason behind this may be the lack of appreciation and understanding of the complexity of CM processes and the practices that support it, as well as limited knowledge about how to lead, plan and implement organizational change [ 34 ]. People normally underestimate the work involved in implementing change and it often falls to busy front-line health care practitioners to facilitate change [ 83 ]. Recognizing the amount of work and tasks required to undertake change and having a dedicated coordinator with the necessary CM skills and knowledge to facilitate and implement change is important to ensure full time attention and dedication to the change process [ 20 , 83 ]. In line with the broader CM literature, we advocate for a more proactive approach to implementing change. Those responsible for the change need to understand “how” to implement change, not just “what” needs to be changed [ 34 ].

Second, most studies identified the application of operational practices, such as developing new work processes, protocols and guidelines (69%), as well as providing training and education (72%). Training aligns with one of the most commonly used and mentioned CM activities, as reported in several MOMENTUM in-depth telemedicine cases [ 17 ]. This highlights the extent to which work practices and routines are impacted by the introduction of telemedicine. Integrating telemedicine is often challenging and disruptive to existing practices [ 16 ]. These disruptions place new demands on the organization and the people involved in delivering the telemedicine services, who often report that telemedicine consultations require more resources (e.g., time, new roles) than conventional consultations [ 84 ]. However, our review identified that only a quarter of studies reported on ensuring sufficient resources for telemedicine implementations. Adequate resourcing and support are essential to both drive and sustain change [ 17 , 85 , 86 ], however such resourcing is often difficult to obtain in the context of health care organisations with constrained resources [ 83 ]. Resources to sustain a service normally include an initial investment for the early deployment of a service and resources for on-going operations [ 17 ]. To ensure sustainable change, trade-offs may have to be made, such as the redeployment or redirection of scarce resources toward the new work activities of telemedicine services [ 85 ].

Third, we note that several studies in our review focus on either strategic or operational practices, but rarely include both, indicating scope to apply a more holistic CM approach when implementing telemedicine. When insufficient focus is given to strategic factors, efforts will be wasted on operational issues with little alignment between management practices to reconfigure work processes and address the changes in day-to-day operations [ 34 ]. Similarly, when too much focus is given to operational factors at the expense of strategic considerations, it is unlikely the required assistance, commitment and acceptance from stakeholders, sites and partners, will be achieved [ 20 ]. Without a critical mass of support for the operational change [ 87 ], implementation is unlikely to be successful. A combination of both strategic and operational practices is required to guide and support people throughout the process of change and ensure the sustainability of implemented services.

CM practices that are not commonly reported in telemedicine studies

Based on current CM literature and models [ 20 , 88 , 89 ], the following CM practices have not been commonly reported in telemedicine implementation studies: 1) anticipate, and identify gaps and areas of resistance; 2) integrate change management plan into a project plan and; 3) celebrate success and short-term wins.

Resistance to adopting telemedicine services is a common barrier found in implementation studies of telemedicine [ 8 , 25 , 90 ], yet there is very little reported about how to effectively deal with resistance. It is vital for a CM strategy to include activities that anticipate, work through and manage resistance across each of the three phases of the CM process [ 88 , 91 ] (see Fig. 1 ). CM plans have to be tailored to the types of resistance encountered, which requires assessing who might resist the change and for what reasons [ 88 , 91 ]. According to Kotter & Schlesinger the four most common reasons why people resist change are: 1) people believe that the change will result in them losing something of value; 2) lack of trust and awareness about the implications of the change; 3) having a different assessment of the change (e.g., a belief that the change will incur more costs than benefits for themselves and the organization) and; 4) low tolerance for change [ 88 ]. Some ways to overcome resistance have already been identified in this review, such as training and education, engaging stakeholders and management support to facilitate the change process. However, these are often only applied in the initial phases of the implementation. Few managers realize that these CM practices need to be used to address resistance throughout the course of the change process.

The change management literature identifies other ways of dealing with resistance, such as leveraging and engaging senior leaders throughout all phases of the change process [ 34 ], influencing their direct reports and thus acquiring organizational commitment and support. While gaining leadership support was identified in a little over a quarter of the articles on telemedicine implementation in our review, the role of leadership was largely restricted to the initial first phase of the implementation process. Yet leaders play a crucial role in persuading and directing people throughout the change process [ 17 , 92 , 93 ], which starts by setting the stage for acceptance, framing the preliminary plan, managing the mood of the organization and reinforcing new behaviors and routines [ 93 ]. The CM literature makes clear that leaders need to play a visible role in guiding and supporting the change throughout all phases of the process [ 86 ]. According to Prosci’s benchmarking reports since 1998, active and visible leadership or sponsorship is the strongest contributor to the success of change initiatives [ 94 ]. Similarly, the MOMENTUM report highlights the importance of leadership through a ‘champion’ as a critical success factor [ 17 ]. Successful champions are normally in a position of authority or influence in the organization and can mobilize resources to implement and sustain a telemedicine service [ 17 ].

Creating a CM plan and strategy is a key practice identified in telemedicine review studies [ 16 ]. However, integrating CM and project management is rarely considered in telemedicine implementation projects. Project management and CM have different methodologies that are complementary and mutually supportive of each other, with each contributing to a higher likelihood of successful implementation of projects [ 89 , 95 ]. When project management and CM are integrated the efforts of both can be focused on a single objective, risks can be more proactively identified and mitigated, project activities (i.e., technical and people) can be aligned and lastly, the flow of information can be more effectively used and managed (e.g., feedback about usage and adoption) [ 89 ].

Celebrating success and recognizing short-term or small wins are recognized as success factors prescribed in common models of change and an important step for reinforcing change [ 19 , 20 ], yet rarely considered when establishing telemedicine services based on our review. These CM practices help maintain morale and encourages progress toward longer term change objectives, builds support and provide positive and public acknowledgement to reinforce change [ 19 , 96 ]. Recognizing short-term wins can also help convince those who are skeptical about the change that it is viable and may prompt others to buy-in [ 20 , 96 ].

Our review has some limitations related to our search strategy. First, we focused on articles published within the past 10 years in recognition of the fast-moving nature of technology to support telemedicine. While this ensures our review reflects current practice, there may have been other CM practices reported in earlier studies that are not represented in this review. Second, given that the last database search was conducted in June 2019, articles published since then will not be included. Third, our search may not have identified all relevant published studies or all CM activities, particularly where authors did not report all practices used during the implementation of telemedicine. Fourth, there may be articles relevant to our review within the grey literature, which were excluded as our search focused only on peer-reviewed studies. Fifth, while we followed Arksey and O’Malley’s framework for scoping reviews by adopting a broad search during study identification, there are additional search terms that could have been incorporated, which may have yielded further relevant studies. Sixth, limiting our search to include English-only articles may have resulted to excluding some relevant studies.

Finally, given limited resources and having initially commenced this scoping review during the doctoral dissertation of the first author, only one reviewer was systematically involved in all aspects of the search process but this was complemented by team discussions throughout the screening phase to assess abstracts, which did not clearly meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as full-text eligibility. Nonetheless, dependence on one reviewer may have led to some studies being missed. Given the clarity of our research aims and a defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, the reviewer’s dependence on interpretation regarding eligibility of studies would have been lessened [ 97 ]. While single screening has been used for some systematic reviews [ 97 ] and other scoping reviews (e.g., [ 98 , 99 ]), we recognize that a dual approach in the screening and study identification process would have strengthened the results [ 100 ]. We are confident, given the broad inclusion criteria and the methodology described, that we have provided a more comprehensive and broader overview of what and how CM practices have been used in telemedicine implementation than has existed previously and drawn out important insights and learnings.

Given the high volume of published telemedicine case reports, we were expecting a higher number of studies to report on the CM practices and strategies used during implementation. Yet what we found was that, while many studies report on the challenges or barriers encountered when implementing change or the CM practices that would have been beneficial to use in hindsight, only 48 studies reported on the practices and strategies actually used to facilitate implementation and adoption of telemedicine services.

Based on our scoping review, we suggest a need for a process-based approach which comprehensively deploys a combination of strategic and operational practices when managing change efforts. Instead of focusing on barriers and facilitators of change, we encourage future telemedicine [ 8 ] research to examine the change processes and practices used to achieve successful implementation, particularly those practices that address the cultural and people issues, given many barriers to adoption center around attitudes and behaviors towards change [ 8 , 23 ]. This scoping review is a starting point for approaching the implementation of telemedicine as a process of change and we hope it will encourage future telemedicine research to explore and recognize the importance of effective CM practices not only in telemedicine services, but also in the implementation of other health care service projects more broadly.

Acknowledgements

Abbreviations, authors’ contributions.

JK conceptualized and wrote this paper, as well as conducted the review and screening process, with the input and guidance of the other two authors. NG contributed to the refinement of the research aims, interpretation and presentation of the findings, and the conceptualization and development of the practice framework (Fig. 1 ) and summary table (Table 3 ) and provided important insights for the discussion and conclusion sections. MMK contributed to the development of the search strategy and inclusion and exclusion criteria. All authors contributed to reading, revising and approving the manuscript.

Authors’ information

JK is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at UQ Business School, The University of Queensland (UQ). She holds a Ph. D in Business (Management/Strategy) and an MBA, both obtained from UQ. Her doctoral studies focused on the adoption and implementation process of telemedicine services in residential aged care facilities. Her research takes a practice theory approach when studying change processes in various professional contexts such as health care services.

NG is Professor of Management and KPMG Chair in Organizational Trust at UQ Business School, the University of Queensland, and an International Research Fellow at the University of Oxford. Her health-oriented research focuses on trust in healthcare organizations and their services, the implementation and adoption of technology-enabled health services (particularly telemedicine) and preserving trust during organizational change and technological disruption. She has served as a Chief Investigator on multiple grants investigating these issues, including the UQ Centre for Research Excellence in Telehealth.

MMK is a Health Scientist and Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Health Services Research working in the Ageing and Geriatric Medicine Program and Telehealth Program. She is an Adjunct Professor in the School of Nursing at the University of Northern British Columbia Canada. She holds a Ph. D in the field of medicine, which involved validating the accuracy of cognitive assessment by videoconferencing for the diagnosis of dementia. Her research focus is the quality of care delivered by health care services across sectors with a particular emphasis on patients with complex conditions and challenges accessing care (older adults, patients with dementia, rural patients).

This work was supported by two research grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council: The Centre for Research Excellence in Telehealth (APP1061183; awarded to the second author) and a Partnership Project (APP1116052; awarded to the second author). These grants supported a PhD scholarship and Postdoctoral Research Fellowship awarded to the first author.

Availability of data and materials

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

LITERATURE REVIEW ON CHANGE MANAGEMENT

Related Papers

South Asian research journal of humanities and social sciences

Prof. Nwachukwu P . Ololube

William Makumbe

The purpose of this study was to bring together and a nalyze significant writings on change management in order to establish key variables in effective change management. Whilst there are many change models that have prescribed stages involved in implementi ng successful change management, a synthesis of the actual key variables that act as a bedrock in effective organisation change is missing in literature. The literature review undertaken in this study therefore sought to summarise the models by explaining the key predictors of effective change management. This article argues that Change leadership, communication, employee engagement and employee commitment are key variables in successful organisation change implementation.

elijah njuguna

Organizations are continually confronting challenges to remain competitive and successful, which compels organizations to regularly re-evaluate their strategies, structures, policies, operations, processes and culture. Managing change effectively is however a main challenge in the change management domain because of massive human involvement. Thus, managers and change agents are eager to know how to encourage and effectively prepare employees for change situation. This paper carries out a critical review on change management on employees performance. The paper reviews the origin of change management concept on employees performance from academic and management perspective, factors influencing the growth and adoption of the change management on employees’ performance concept, theoretical framework of change management on employees performance and the empirical studies on change management on employees performance. The paper also identifies the research gaps identified in the concept....

David Aninkan

For any organisation to remain afloat, it must always position itself to competitively struggle for the limited resources from the ever changing and dynamic environment; by not only responding to change but looking out for change. Organisational Change, change management and resistance to change; are tripartite concepts in which no one can be conveniently treated singularly without mentioning the other ones. The methodology adopted in the study is exploratory approach. It examined the literature to present how change management determines the level of change resistance and the eventual organisational change. The paper commenced with the conceptual literature, to the theoretical literature, empirical literature, findings from the literature, the conceptual framework, and the conclusion. Recommendations were made for organisations to avail themselves of the services of experts in human capital management, to handle change implementation programmes for them. Keywords: Organisationa...

Karyn S Krawford

Introduction This case study focuses on a fast growing online business services startup platform in Australia. It operates as its own functioning business unit under the umbrella of News Ltd, who own a cluster of individual digital companies also known as Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation, one of the world’s largest global media companies. This case study examines a change that occurred when almost the entire senior management staff level was replaced including the CEO two years ago. Organisational change is something that occurs throughout an organisation’s life cycle and effects the entire organisation rather than one part of it. Employing a new person is one example. Change is increasing due to a number of forces including globalisation led by rapidly advancing technologies, cultural diversity, environmental resources and the economy; therefore the ability to recognise the need for change as well as implement change strategies effectively, in a proactive response to internal and external pressures is essential to organisational performance. Internal changes can include organisational structure, process and HR requirements and external changes involve government legislation, competitor movements and customer demand (Wood et al, 2010). Change does not need to be a painful process, as it may seem when observing the amount of failed change management initiatives with reports as low as 10% of researched success rates (Oakland & Tanner, 2007), when successful change management strategies are utilised and planned, including effective communication strategies, operational alignment, readiness to change and implementation, which all lower and overcome resistance (Wood et al, 2010). There is a great amount of literature on the negative aspects and difficult management with employees resisting change, however Wood et al (2010) challenge this notion by questioning the change management process as people do not resist change itself but aspects of the change that affects them personally such as fear of the unknown, status, remuneration and comfort. Resistance to these changes is a healthy reaction and can be managed effectively in the beginning by ensuring communication and using one of the change initiatives described here .

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences

Baharudin Kadir

As organizations are facing challenges in the globalization era, changes within the management in the organization must be made to ensure it can position itself in the competitive and ever changing environment. A well planned change management is crucial to ensure that change can be made to the entire organization and effectively implemented. Change management is widely known in the private sector, however, it is progressively rising in the public sector. Organizational change must be driven by a good leadership so that it is effectively and efficiently administered. This paper aimed to evaluate how prior researches had been dealing with change management in recent years taking in account of leadership styles of the managers. Well-known literatures will be discussed to outline the importance of effective leadership style for managing organizational change. The overall view from the past studies show that a good manager has the ability to drive the employees to accept change initiati...

Rune Todnem By

It can be argued that the successful management of change is crucial to any organisation in order to survive and succeed in the present highly competitive and continuously evolving business environment. However, theories and approaches to change management currently available to academics and practitioners are often contradictory, mostly lacking empirical evidence and supported by unchallenged hypotheses concerning the nature of contemporary organisational change management. The purpose of this article is, therefore, to provide a critical review of some of the main theories and approaches to organisational change management as an important first step towards constructing a new framework for managing change. The article concludes with recommendations for further research.

In the competitive business environment, the ability for a company to adapt the change management has become a challenge for survival. The agenda of this paper is to review the change management for BBC Worldwide. The report will be analyzing the triggers point and various causes that influence the change experience for the organization. The report will also identify the importance of the cultural and social dimension in relation of the organization change.

International Journal of Innovative Research and Development

Romanian Statistical Review Supplement

Liviu Tudor

RELATED PAPERS

Sol Schaefer

Wildan Wildan

Giulio Fracasso

Social Media + Society

IJEAB JOURNAL , Prof. Dorcas Isutsa

Fateme Jafari

The Spine Journal

Scientific reports

James Wickham

Luís Miguel

Frontiers in Plant Science

Stefan Little

Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü Dergisi

nurcan baykuş savaşaneril

SITI AMINAH

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Nicos Nicola

Sociobiology

Carlos Espinosa Vergara

2006 IEEE International Conference on Electro/Information Technology

eduardo rivera

Jurnal Ilmiah Teknik Industri

Winda Halim

Bozok tıp dergisi

Information Technologies and Learning Tools

Oleksii S . Voronkin

IEEE Access

RePEc: Research Papers in Economics

Maureen Rosellon

Ariadna Serón Navas

2009 International Conference on Parallel Processing Workshops

npj Computational Materials

Robert Ritchie

Sultan I. Mustafa, Sultan II. Osman, Sultan IV. Murad Dönemleri ve Bursa

Ismail Yasayanlar

Irish Historical Studies

Andrew G. Newby

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Towards a Universal Model of Engineering Change Management

- Open access

- Published: 10 November 2023

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Jakub Tryczak ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0000-8737-0060 1 ,

- Anna Lis ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1527-7796 2 ,

- Paweł Ziemiański ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4391-9282 2 &

- Jacek Czyżewicz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4338-6815 3

794 Accesses

Explore all metrics

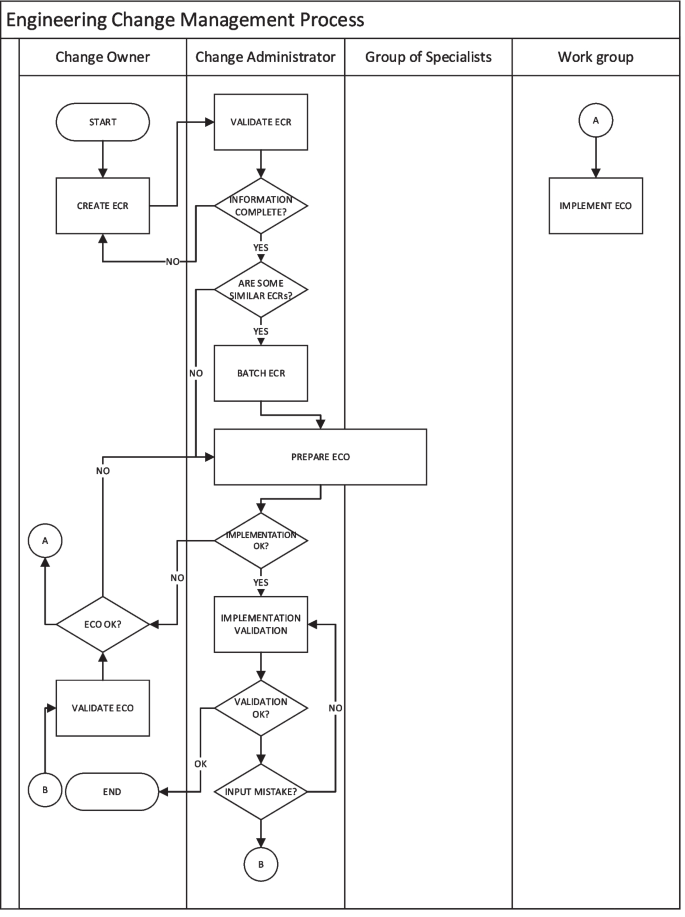

The paper deals with the issue of engineering change management (ECM). ECM has received much less attention in the literature than general change management. Moreover, due to their specifics (complexity and multifaceted nature), hitherto developed ECM models are difficult to implement in companies. The paper aims to develop a simplified, universal, and hence easily applicable model of ECM. We based our assumptions on a case study of a manufacturing company with low-volume production, representing a high-mix type, posing the following research question: how to improve the ECM process to make it simpler and more quickly adaptable in companies with the analyzed type of production when compared to the existing models? To answer this question, an exploratory qualitative study was conducted in late 2021/early 2022 using in-depth personal interviews. The research sample included 31 employees involved in ECM processes. Conventional qualitative content analysis was the primary technique for analyzing and interpreting the data. The study identified gaps and bottlenecks in the existing ECM model. On this basis, a proposal for a new ECM model was developed, distinguished by its simplicity and versatility (it can be implemented in companies operating in various industries). Particular emphasis was placed on ensuring the flow of information and circulation of technical documentation between the departments involved and clarifying the role of the change administrator. The paper sheds new light on how to implement engineering changes in organizations and has considerable application value.

Similar content being viewed by others

Engineering Change Management in the Engineer-to-Order Production Environment: Insights from Two Case Studies

Characterising the Industrial Context of Engineering Change Management

Comparison of Seven Company-Specific Engineering Change Processes

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Change management and engineering change management (ECM) processes have become increasingly important in manufacturing companies. While the change management process is well grounded in the literature, the engineering change management process needs more focus because of its relative newness. As the available databases (Web of Science, Scopus, ProQuest) show, between 2019 and 2022, over 700 publications concerning change management were released each year. Most of them covered topics of organizational and social changes (Todnem, 2005 ; Galli, 2018 ; Hughes, 2007 ). The engineering change management process has received considerably less attention. As will be shown in the literature review, several researches describe ECM models in manufacturing companies. More so, each describes a different type of production and covers different aspects of management — either managing stakeholders or fulfilling a market gap (Masmoudi et al., 2017 ), which limits their universality. Moreover, previous publications on ECM describe it as an overly complicated process involving a significant number of people (Maceika & Toločka, 2021 ; Sjögren et al., 2019 ; Reddi & Moon, 2011 ; Pikosz & Malmqvist, 1998 ; Tavčar & Duhovnik, 2005 ). The complexity of this process is likely to be too high for the actual company’s needs. In many cases, a triumph of form over content takes place as a proposed process requires connecting many departments and stakeholders with their particular interests and creates overly complicated dependencies and linkages. It is possible to simplify this process and make it easier to implement. Preparing an audit that allows to clarify the actual process is a necessary starting point. Devoid of its complexity, the process can allow process owners to avoid mistakes and misunderstandings.

The present paper intends to fill a gap in the literature. In the present article, we aim to show that the ECM process can be simple and universal, which, in manufacturing companies, requires establishing the role of an engineering change administrator (Mo & Caporaso, 2021 ). The sources of the engineering change management process should be distinguished depending on the location of the change — it might concern a new product or changes introduced in an existing one. The present article focuses on the latter — modifying an existing product. In our paper, we refer to the results of an exploratory study aimed at answering the following research question: How to improve the ECM process to make it simpler and quickly adaptable in manufacturing companies with low-volume and high-mix type of production? We based our assumptions on a case study of a manufacturing company with low-volume and high-mix type of production. Our intention is to create a universal ECM model, especially for enterprises with the type of production described.

The article is divided into five parts. The first part includes the literature review on the topics of change management and engineering change management. The second includes the research methodology employed in the conducted study, and it is followed by the description of the research results presented in the third part. In the fourth part, the authors discuss and propose a universal and simplified model of planned engineering change. Finally, the fifth part includes discussion, practical implications, further directions of research development, research limitations, and conclusions.

Literature Review

In order to identify scientific papers closely related to the research topic and identify the most important findings in the analyzed area, we conducted a traditional literature review. In doing so, we relied on Web of Science, Scopus, and ProQuest databases, performing searches by query: (engineering change OR engineering change management OR technical change) AND (change management OR change management process). Searches were further narrowed to publicly available articles, published in English and related to the discipline of management.

As determined by the literature review, change management is a process of continuously renewing a direction and structure and adjusting for internal and external clients (Moran & Brightman, 2001 ; Yin et al., 2022 ). Todnem ( 2005 ) asserted that in the change management literature, there was a general consensus regarding two aspects. Firstly, in the current business environment, the magnitude and pace of changes are greater than before (Burnes, 2004 ; Carnall, 2003 ; Kotter, 1996 ; Luecke, 2003 ; Schuh et al., 2017 ). Secondly, change can be triggered by external or internal factors and can take a different form in different organizations or industries (Burnes, 2004 ; Carnall, 2003 ; Kotter, 1996 ; Luecke, 2003 ). The purpose of this process is a transformation from the actual state to the target state. On this path, a few steps should be considered, which are covered in change management models.

Among the most popular change management models are Kurt Lewin’s change management model, Kotter’s 8-step change management model, ADKAR change management model, and the McKinsey 7-S change management model. Lewin’s model ( 1951 ) proposed only three main phases of change management: unfreezing, transition, and refreezing. Kotter’s model includes the sense of urgency creation, core coalition creation, strategic vision development, vision plan sharing, employee empowering, short-term wins gathering, gains and producing changes consolidation, and changes initiation. It is important to emphasize that the model proposed by Kotter ( 1996 ) was the first one that depicted change as a circular rather than a linear process. The name of the next model, ADKAR, is the acronym for Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, and Reinforcement, which are the phases of the change management process that describe the appropriate approach and reacting to employees’ needs. The McKinsey 7-S model describes a group of interrelated factors influencing the company’s ability to introduce changes: strategy, structure, systems, skills, staff, style, and shared values (Singh, 2013 ).

Engineering changes are changes or/and modifications in fits, functions, materials, dimensions, etc., of a product and its components introduced after it is released (Huang et al., 2003 ; Sonzini et al., 2015 ). The process of introducing planned engineering changes has its purpose in production standardization, product quality improvement, or modification of one of the components (Tavčar & Duhovnik, 2005 ). Furthermore, the process of engineering change management supports production management departments in ensuring a fluent flow of documentation (Knaus, 2022 ). The main purpose of this process is to clarify communication between departments and efficiently prepare change of documentation by establishing communication channels and providing an appropriate information-gathering system (Tavčar & Duhovnik, 2005 ). While ECM may not be equally important for all types of organizations, it is crucial for manufacturing companies (Tavčar & Duhovnik, 2005 ). To gain as much market share as possible, they prepare many types and modifications of their products that require appropriate technical documentation.

ECM is a particular type of change management. Its primary purpose is the management of technical documentation and information flow in technical departments related to the production department and product manufacturing. Engineering changes are intended to correct engineering failures, exploit new market opportunities, reduce production costs, or increase advantage over competitors (Reddi & Moon, 2011 ). Balakrishnan and Chakravarty ( 1996 ) suggest that the positive and negative effects of engineering changes should be analyzed. The former category includes the effects of changes related to the company’s position on the market as they allow increasing advantage over competitors. However, certain consequences of engineering changes for the manufacturing company can be negative as they are connected with increased costs and additional workload.

Several systematic literature reviews on ECM have been conducted. They were performed by the following authors: Wright ( 1997 ), Jarratt et al. ( 2011 ), Hamraz et al. ( 2013 ), and Ullah et al. ( 2016 ). Wright ( 1997 ) prepared an analysis of specific engineering change topics covered in publications between 1980 and 1995. He noticed two main perspectives in analyzing the ECM process: engineering change tools and engineering change methods. Further considerations allowed him to divide those perspectives into subareas. The perspective pertaining to tools was divided into the subareas of data storage (covered in four publications) and design aids (covered in four publications), whereas the perspective pertaining to methods was divided into five subareas: elements of control (covered in eight publications), the effect on customer (covered in two publications), implications for a new product (covered in one publication), single company case studies (covered in three publications), and case studies covering two companies (included in four publications) (Hamraz et al., 2013 ).

In their analysis, Jarratt et al. ( 2011 ) identified five topics. They include a generic outlining of the process, its context and other related activities (the first topic), the nature of the change process, and challenges that arise from change propagation (the second topic). The third describes tools for designers in ECM. The fourth topic includes product-focused aspects, whereas the last describes the connection between the product or process and selecting the appropriate strategies and methods.

Hamraz et al. ( 2013 ) divided the research about ECM into four main groups, each consisting of additional subgroups. The first group concerns the pre-change stage and includes people-oriented, process-oriented, and product-oriented aspects, documents, and considerations. The second group is focused on the stage of introducing the actual change and concerns organizational issues, strategic guidelines, ECM systems and processes, methods, and IT tools. The third group describes research that analyses the engineering change impact: delays, cost, quality, pre-manufacturing stage, manufacturing, post-manufacturing stage, and general effects. Finally, the last group involves general studies. In their considerations, Ullah et al. ( 2016 ) organized publications on ECM differently, according to the adopted definition of EC, product architecture, change propagation, engineering change process, and tools that support engineers in the ECM process. Furthermore, several different types of engineering changes and their causes can be found in the literature, including customer specification changes, misunderstanding between customer specification and technical requirements, production problems, problems that are a result of prototyping, quality issues, and development for future use (Pikosz & Malmqvist, 1998 ; Maceika & Toločka, 2021 ).

ECM process does not only apply to the existing product. It also concerns new product development (Balakrishnan & Suresh, 2019 ). In this case, engineering change orders (ECO) can generate considerable costs (Clark & Fujimoto, 1991 ) and have the characteristics of a “snowball effect” (Terwiesch & Loch, 1999 ). Costs are generated because of multiple iterations, a growing number of stakeholders, and different expectations toward the new product. An additional aspect of the ECM process is the accompanying rush, which can result in wrong decisions (Dostaler, 2010 ). Dostaler ( 2010 ) identified several factors limiting the number of ECOs, such as an additional person from the manufacturing department in a design team, good communication, and project leadership (Wheelwright & Clark, 1992 ). The process of ECM is vital because it influences the lead time and production costs related to manufacturing new products (Reddi & Moon, 2011 ). When a few companies from the same group work on the same product, the quantity of their customer–supplier relations increases significantly. In that case, the ECM process is essential for effective cooperation. It structures communication and introduces standards pertaining to collaboration with different stakeholders (Reddi & Moon, 2011 ). ECM is crucial when the number of collaborators increases, particularly in the case of platform-based development. It is vital due to requirements related to managing changes in elements and standardizing engineering systems used for data sharing (Bergsjö et al., 2015 ).