Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Empathy Defined

What is empathy.

The term “empathy” is used to describe a wide range of experiences. Emotion researchers generally define empathy as the ability to sense other people’s emotions, coupled with the ability to imagine what someone else might be thinking or feeling.

Contemporary researchers often differentiate between two types of empathy : “Affective empathy” refers to the sensations and feelings we get in response to others’ emotions; this can include mirroring what that person is feeling, or just feeling stressed when we detect another’s fear or anxiety. “Cognitive empathy,” sometimes called “perspective taking,” refers to our ability to identify and understand other people’s emotions. Studies suggest that people with autism spectrum disorders have a hard time empathizing .

Empathy seems to have deep roots in our brains and bodies, and in our evolutionary history . Elementary forms of empathy have been observed in our primate relatives , in dogs , and even in rats . Empathy has been associated with two different pathways in the brain, and scientists have speculated that some aspects of empathy can be traced to mirror neurons , cells in the brain that fire when we observe someone else perform an action in much the same way that they would fire if we performed that action ourselves. Research has also uncovered evidence of a genetic basis to empathy , though studies suggest that people can enhance (or restrict) their natural empathic abilities.

Having empathy doesn’t necessarily mean we’ll want to help someone in need, though it’s often a vital first step toward compassionate action.

For more: Read Frans de Waal’s essay on “ The Evolution of Empathy ” and Daniel Goleman’s overview of different forms of empathy , drawing on the work of Paul Ekman.

What are the Limitations?

When Empathy Hurts, Compassion Can Heal

A new neuroscientific study shows that compassion training can help us cope with other…

Does Empathy Reduce Prejudice—or Promote It?

Rodolfo Mendoza-Denton explains how to make sense of conflicting scientific evidence.

How to Avoid the Empathy Trap

Do you prioritize other people's feelings over your own? You might be falling into the…

Featured Articles

One Skill That Can Help Students Bridge Political Divides

Here's how one teacher has tried to help students envision better outcomes for everyone, a skill researchers call "moral imagination."

Who Finds Joy in Other People’s Joy?

Who feels good when a good thing happens for someone else? Our GGSC sympathetic joy quiz results suggest it has almost nothing to do with money or…

How Accurate Are Media Portrayals of Foster Families?

Movies and TV often paint the youth foster system in a negative light. But do people who went through the system agree?

Can Artificial Intelligence Help Human Mental Health?

A conversation with UC Berkeley School of Public Health professor Jodi Halpern about AI ethics, empathy, and mental health.

The Best Greater Good Articles of 2023

We round up the most-read and highly rated Greater Good articles from the past year.

Our Favorite Books of 2023

Greater Good’s editors pick the most thought-provoking, practical, and inspirational science books of the year.

Why Practice It?

Empathy is a building block of morality—for people to follow the Golden Rule, it helps if they can put themselves in someone else’s shoes. It is also a key ingredient of successful relationships because it helps us understand the perspectives, needs, and intentions of others. Here are some of the ways that research has testified to the far-reaching importance of empathy.

- Seminal studies by Daniel Batson and Nancy Eisenberg have shown that people higher in empathy are more likely to help others in need, even when doing so cuts against their self-interest .

- Empathy is contagious : When group norms encourage empathy, people are more likely to be empathic—and more altruistic.

- Empathy reduces prejudice and racism : In one study, white participants made to empathize with an African American man demonstrated less racial bias afterward.

- Empathy is good for your marriage : Research suggests being able to understand your partner’s emotions deepens intimacy and boosts relationship satisfaction ; it’s also fundamental to resolving conflicts. (The GGSC’s Christine Carter has written about effective strategies for developing and expressing empathy in relationships .)

- Empathy reduces bullying: Studies of Mary Gordon’s innovative Roots of Empathy program have found that it decreases bullying and aggression among kids, and makes them kinder and more inclusive toward their peers. An unrelated study found that bullies lack “affective empathy” but not cognitive empathy, suggesting that they know how their victims feel but lack the kind of empathy that would deter them from hurting others.

- Empathy reduces suspensions : In one study, students of teachers who participated in an empathy training program were half as likely to be suspended, compared to students of teachers who didn’t participate.

- Empathy promotes heroic acts: A seminal study by Samuel and Pearl Oliner found that people who rescued Jews during the Holocaust had been encouraged at a young age to take the perspectives of others.

- Empathy fights inequality. As Robert Reich and Arlie Hochschild have argued, empathy encourages us to reach out and want to help people who are not in our social group, even those who belong to stigmatized groups , like the poor. Conversely, research suggests that inequality can reduce empathy : People show less empathy when they attain higher socioeconomic status.

- Empathy is good for the office: Managers who demonstrate empathy have employees who are sick less often and report greater happiness.

- Empathy is good for health care: A large-scale study found that doctors high in empathy have patients who enjoy better health ; other research suggests training doctors to be more empathic improves patient satisfaction and the doctors’ own emotional well-being .

- Empathy is good for police: Research suggests that empathy can help police officers increase their confidence in handling crises, diffuse crises with less physical force, and feel less distant from the people they’re dealing with.

For more: Learn about why we should teach empathy to preschoolers .

How Do I Cultivate It?

Humans experience affective empathy from infancy, physically sensing their caregivers’ emotions and often mirroring those emotions. Cognitive empathy emerges later in development, around three to four years of age , roughly when children start to develop an elementary “ theory of mind ”—that is, the understanding that other people experience the world differently than they do.

From these early forms of empathy, research suggests we can develop more complex forms that go a long way toward improving our relationships and the world around us. Here are some specific, science-based activities for cultivating empathy from our site Greater Good in Action :

- Active listening: Express active interest in what the other person has to say and make him or her feel heard.

- Shared identity: Think of a person who seems to be very different from you, and then list what you have in common.

- Put a human face on suffering: When reading the news, look for profiles of specific individuals and try to imagine what their lives have been like.

- Eliciting altruism: Create reminders of connectedness.

And here are some of the keys that researchers have identified for nurturing empathy in ourselves and others:

- Focus your attention outwards: Being mindfully aware of your surroundings, especially the behaviors and expressions of other people , is crucial for empathy. Indeed, research suggests practicing mindfulness helps us take the perspectives of other people yet not feel overwhelmed when we encounter their negative emotions.

- Get out of your own head: Research shows we can increase our own level of empathy by actively imagining what someone else might be experiencing.

- Don’t jump to conclusions about others: We feel less empathy when we assume that people suffering are somehow getting what they deserve .

- Show empathic body language : Empathy is expressed not just by what we say, but by our facial expressions, posture, tone of voice, and eye contact (or lack thereof).

- Meditate: Neuroscience research by Richard Davidson and his colleagues suggests that meditation—specifically loving-kindness meditation, which focuses attention on concern for others—might increase the capacity for empathy among short-term and long-term meditators alike (though especially among long-time meditators).

- Explore imaginary worlds: Research by Keith Oatley and colleagues has found that people who read fiction are more attuned to others’ emotions and intentions.

- Join the band: Recent studies have shown that playing music together boosts empathy in kids.

- Play games : Neuroscience research suggests that when we compete against others, our brains are making a “ mental model ” of the other person’s thoughts and intentions.

- Take lessons from babies: Mary Gordon’s Roots of Empathy program is designed to boost empathy by bringing babies into classrooms, stimulating children’s basic instincts to resonate with others’ emotions.

- Combat inequality: Research has shown that attaining higher socioeconomic status diminishes empathy , perhaps because people of high SES have less of a need to connect with, rely on, or cooperate with others. As the gap widens between the haves and have-nots, we risk facing an empathy gap as well. This doesn’t mean money is evil, but if you have a lot of it, you might need to be more intentional about maintaining your own empathy toward others.

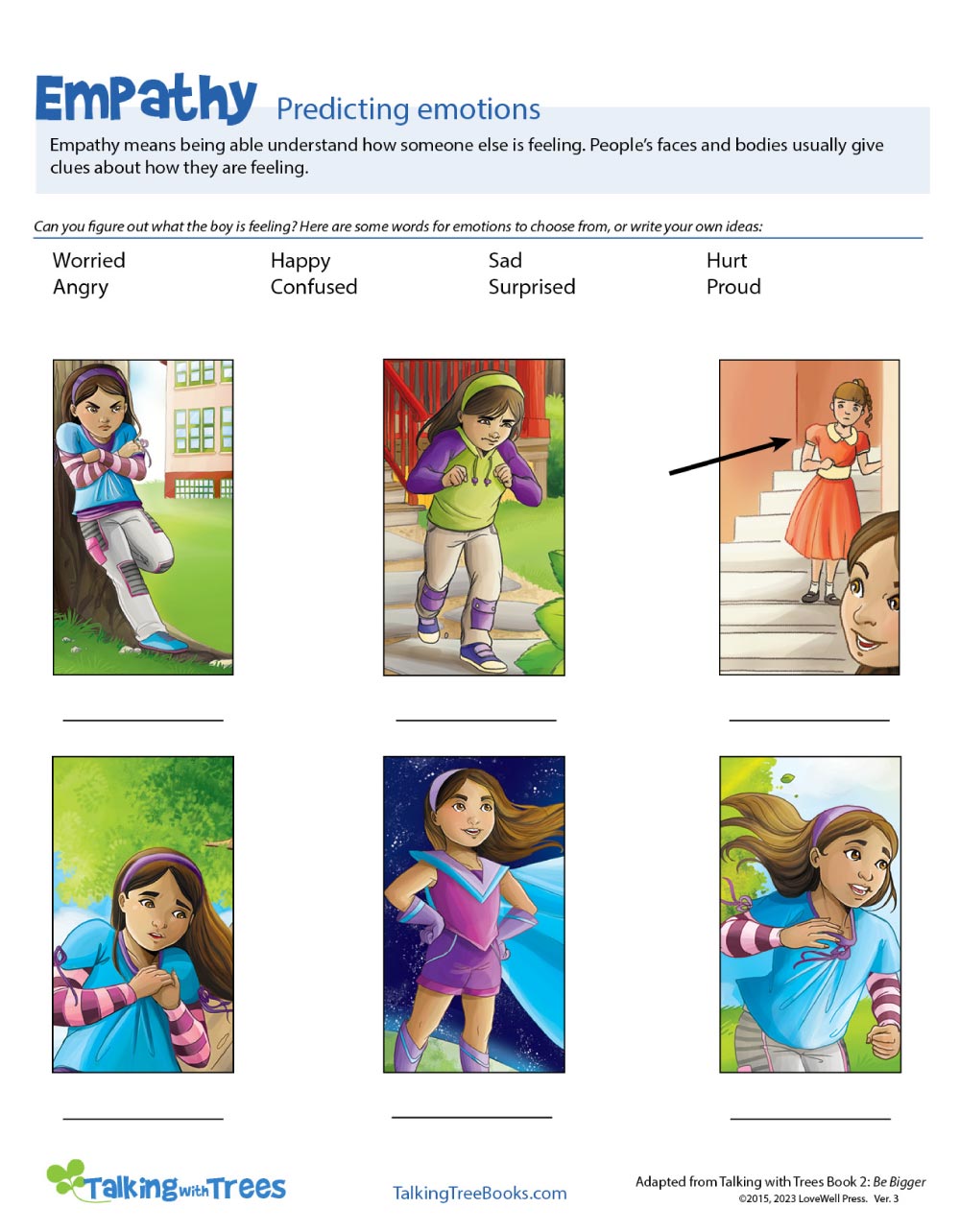

- Pay attention to faces: Pioneering research by Paul Ekman has found we can improve our ability to identify other people’s emotions by systematically studying facial expressions. Take our Emotional Intelligence Quiz for a primer, or check out Ekman’s F.A.C.E. program for more rigorous training.

- Believe that empathy can be learned : People who think their empathy levels are changeable put more effort into being empathic, listening to others, and helping, even when it’s challenging.

For more : The Ashoka Foundation’s Start Empathy initiative tracks educators’ best practices for teaching empathy . The initiative gave awards to 14 programs judged to do the best job at educating for empathy . The nonprofit Playworks also offers eight strategies for developing empathy in children .

What Are the Pitfalls and Limitations of Empathy?

According to research , we’re more likely to help a single sufferer than a large group of faceless victims, and we empathize more with in-group members than out-group members . Does this reflect a defect in empathy itself? Some critics believe so , while others argue that the real problem is how we suppress our own empathy .

Empathy, after all, can be painful. An “ empathy trap ” occurs when we’re so focused on feeling what others are feeling that we neglect our own emotions and needs—and other people can take advantage of this. Doctors and caregivers are at particular risk of feeling emotionally overwhelmed by empathy.

In other cases, empathy seems to be detrimental. Empathizing with out-groups can make us more reluctant to engage with them, if we imagine that they’ll be critical of us. Sociopaths could use cognitive empathy to help them exploit or even torture people.

Even if we are well-intentioned, we tend to overestimate our empathic skills. We may think we know the whole story about other people when we’re actually making biased judgments—which can lead to misunderstandings and exacerbate prejudice.

Understanding others’ feelings: what is empathy and why do we need it?

Senior Lecturer in Social Neuroscience, Monash University

Disclosure statement

Pascal Molenberghs receives funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC Discovery Early Career Research Award: DE130100120) and Heart Foundation (Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship: 1000458).

Monash University provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

This is the introductory essay in our series on understanding others’ feelings. In it we will examine empathy, including what it is, whether our doctors need more of it, and when too much may not be a good thing.

Empathy is the ability to share and understand the emotions of others. It is a construct of multiple components, each of which is associated with its own brain network . There are three ways of looking at empathy.

First there is affective empathy. This is the ability to share the emotions of others. People who score high on affective empathy are those who, for example, show a strong visceral reaction when watching a scary movie.

They feel scared or feel others’ pain strongly within themselves when seeing others scared or in pain.

Cognitive empathy, on the other hand, is the ability to understand the emotions of others. A good example is the psychologist who understands the emotions of the client in a rational way, but does not necessarily share the emotions of the client in a visceral sense.

Finally, there’s emotional regulation. This refers to the ability to regulate one’s emotions. For example, surgeons need to control their emotions when operating on a patient.

Another way to understand empathy is to distinguish it from other related constructs. For example, empathy involves self-awareness , as well as distinction between the self and the other. In that sense it is different from mimicry, or imitation.

Many animals might show signs of mimicry or emotional contagion to another animal in pain. But without some level of self-awareness, and distinction between the self and the other, it is not empathy in a strict sense. Empathy is also different from sympathy, which involves feeling concern for the suffering of another person and a desire to help.

That said, empathy is not a unique human experience. It has been observed in many non-human primates and even rats .

People often say psychopaths lack empathy but this is not always the case. In fact, psychopathy is enabled by good cognitive empathic abilities - you need to understand what your victim is feeling when you are torturing them. What psychopaths typically lack is sympathy. They know the other person is suffering but they just don’t care.

Research has also shown those with psychopathic traits are often very good at regulating their emotions .

Why do we need it?

Empathy is important because it helps us understand how others are feeling so we can respond appropriately to the situation. It is typically associated with social behaviour and there is lots of research showing that greater empathy leads to more helping behaviour.

However, this is not always the case. Empathy can also inhibit social actions, or even lead to amoral behaviour . For example, someone who sees a car accident and is overwhelmed by emotions witnessing the victim in severe pain might be less likely to help that person.

Similarly, strong empathetic feelings for members of our own family or our own social or racial group might lead to hate or aggression towards those we perceive as a threat. Think about a mother or father protecting their baby or a nationalist protecting their country.

People who are good at reading others’ emotions, such as manipulators, fortune-tellers or psychics, might also use their excellent empathetic skills for their own benefit by deceiving others.

Interestingly, people with higher psychopathic traits typically show more utilitarian responses in moral dilemmas such as the footbridge problem. In this thought experiment, people have to decide whether to push a person off a bridge to stop a train about to kill five others laying on the track.

The psychopath would more often than not choose to push the person off the bridge. This is following the utilitarian philosophy that holds saving the life of five people by killing one person is a good thing. So one could argue those with psychopathic tendencies are more moral than normal people – who probably wouldn’t push the person off the bridge – as they are less influenced by emotions when making moral decisions.

How is empathy measured?

Empathy is often measured with self-report questionnaires such as the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) or Questionnaire for Cognitive and Affective Empathy (QCAE).

These typically ask people to indicate how much they agree with statements that measure different types of empathy.

The QCAE, for instance, has statements such as, “It affects me very much when one of my friends is upset”, which is a measure of affective empathy.

Cognitive empathy is determined by the QCAE by putting value on a statement such as, “I try to look at everybody’s side of a disagreement before I make a decision.”

Using the QCAE, we recently found people who score higher on affective empathy have more grey matter, which is a collection of different types of nerve cells, in an area of the brain called the anterior insula.

This area is often involved in regulating positive and negative emotions by integrating environmental stimulants – such as seeing a car accident - with visceral and automatic bodily sensations.

We also found people who score higher on cognitive empathy had more grey matter in the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex.

This area is typically activated during more cognitive processes, such as Theory of Mind, which is the ability to attribute mental beliefs to yourself and another person. It also involves understanding that others have beliefs, desires, intentions, and perspectives different from one’s own.

Can empathy be selective?

Research shows we typically feel more empathy for members of our own group , such as those from our ethnic group. For example, one study scanned the brains of Chinese and Caucasian participants while they watched videos of members of their own ethnic group in pain. They also observed people from a different ethnic group in pain.

The researchers found that a brain area called the anterior cingulate cortex, which is often active when we see others in pain, was less active when participants saw members of ethnic groups different from their own in pain.

Other studies have found brain areas involved in empathy are less active when watching people in pain who act unfairly . We even see activation in brain areas involved in subjective pleasure , such as the ventral striatum, when watching a rival sport team fail.

Yet, we do not always feel less empathy for those who aren’t members of our own group. In our recent study , students had to give monetary rewards or painful electrical shocks to students from the same or a different university. We scanned their brain responses when this happened.

Brain areas involved in rewarding others were more active when people rewarded members of their own group, but areas involved in harming others were equally active for both groups.

These results correspond to observations in daily life. We generally feel happier if our own group members win something, but we’re unlikely to harm others just because they belong to a different group, culture or race. In general, ingroup bias is more about ingroup love rather than outgroup hate.

Yet in some situations, it could be helpful to feel less empathy for a particular group of people. For example, in war it might be beneficial to feel less empathy for people you are trying to kill, especially if they are also trying to harm you.

To investigate, we conducted another brain imaging study . We asked people to watch videos from a violent video game in which a person was shooting innocent civilians (unjustified violence) or enemy soldiers (justified violence).

While watching the videos, people had to pretend they were killing real people. We found the lateral orbitofrontal cortex, typically active when people harm others, was active when people shot innocent civilians. The more guilt participants felt about shooting civilians, the greater the response in this region.

However, the same area was not activated when people shot the soldier that was trying to kill them.

The results provide insight into how people regulate their emotions. They also show the brain mechanisms typically implicated when harming others become less active when the violence against a particular group is seen as justified.

This might provide future insights into how people become desensitised to violence or why some people feel more or less guilty about harming others.

Our empathetic brain has evolved to be highly adaptive to different types of situations. Having empathy is very useful as it often helps to understand others so we can help or deceive them, but sometimes we need to be able to switch off our empathetic feelings to protect our own lives, and those of others.

Tomorrow’s article will look at whether art can cultivate empathy.

- Theory of mind

- Emotional contagion

- Understanding others' feelings

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Communications and Engagement Officer, Corporate Finance Property and Sustainability

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Empathy?

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Verywell / Bailey Mariner

Empathy is the ability to emotionally understand what other people feel, see things from their point of view, and imagine yourself in their place. Essentially, it is putting yourself in someone else's position and feeling what they are feeling.

Empathy means that when you see another person suffering, such as after they've lost a loved one , you are able to instantly envision yourself going through that same experience and feel what they are going through.

While people can be well-attuned to their own feelings and emotions, getting into someone else's head can be a bit more difficult. The ability to feel empathy allows people to "walk a mile in another's shoes," so to speak. It permits people to understand the emotions that others are feeling.

Press Play for Advice on Empathy

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast , featuring empathy expert Dr. Kelsey Crowe, shares how you can show empathy to someone who is going through a hard time. Click below to listen now.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

Signs of Empathy

For many, seeing another person in pain and responding with indifference or even outright hostility seems utterly incomprehensible. But the fact that some people do respond in such a way clearly demonstrates that empathy is not necessarily a universal response to the suffering of others.

If you are wondering whether you are an empathetic person, here are some signs that show that you have this tendency:

- You are good at really listening to what others have to say.

- People often tell you about their problems.

- You are good at picking up on how other people are feeling.

- You often think about how other people feel.

- Other people come to you for advice.

- You often feel overwhelmed by tragic events.

- You try to help others who are suffering.

- You are good at telling when people aren't being honest .

- You sometimes feel drained or overwhelmed in social situations.

- You care deeply about other people.

- You find it difficult to set boundaries in your relationships.

Are You an Empath? Take the Quiz!

Our fast and free empath quiz will let you know if your feelings and behaviors indicate high levels of traits commonly associated with empaths.

Types of Empathy

There are several types of empathy that a person may experience. The three types of empathy are:

- Affective empathy involves the ability to understand another person's emotions and respond appropriately. Such emotional understanding may lead to someone feeling concerned for another person's well-being, or it may lead to feelings of personal distress.

- Somatic empathy involves having a physical reaction in response to what someone else is experiencing. People sometimes physically experience what another person is feeling. When you see someone else feeling embarrassed, for example, you might start to blush or have an upset stomach.

- Cognitive empathy involves being able to understand another person's mental state and what they might be thinking in response to the situation. This is related to what psychologists refer to as the theory of mind or thinking about what other people are thinking.

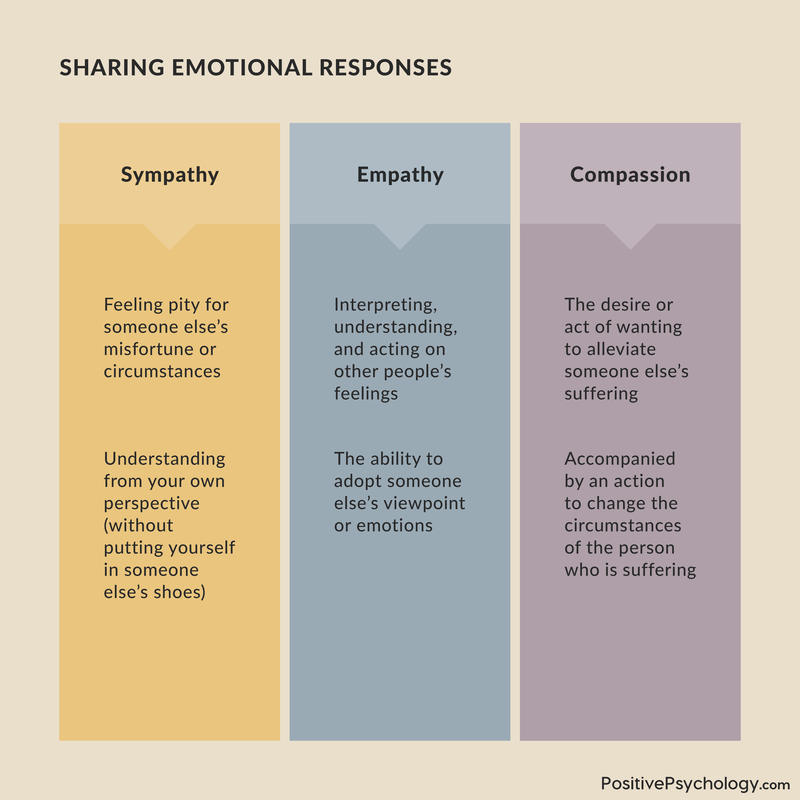

Empathy vs. Sympathy vs. Compassion

While sympathy and compassion are related to empathy, there are important differences. Compassion and sympathy are often thought to be more of a passive connection, while empathy generally involves a much more active attempt to understand another person.

Uses for Empathy

Being able to experience empathy has many beneficial uses.

- Empathy allows you to build social connections with others . By understanding what people are thinking and feeling, you are able to respond appropriately in social situations. Research has shown that having social connections is important for both physical and psychological well-being.

- Empathizing with others helps you learn to regulate your own emotions . Emotional regulation is important in that it allows you to manage what you are feeling, even in times of great stress, without becoming overwhelmed.

- Empathy promotes helping behaviors . Not only are you more likely to engage in helpful behaviors when you feel empathy for other people, but other people are also more likely to help you when they experience empathy.

Potential Pitfalls of Empathy

Having a great deal of empathy makes you concerned for the well-being and happiness of others. It also means, however, that you can sometimes get overwhelmed, burned out , or even overstimulated from always thinking about other people's emotions. This can lead to empathy fatigue.

Empathy fatigue refers to the exhaustion you might feel both emotionally and physically after repeatedly being exposed to stressful or traumatic events . You might also feel numb or powerless, isolate yourself, and have a lack of energy.

Empathy fatigue is a concern in certain situations, such as when acting as a caregiver . Studies also show that if healthcare workers can't balance their feelings of empathy (affective empathy, in particular), it can result in compassion fatigue as well.

Other research has linked higher levels of empathy with a tendency toward emotional negativity , potentially increasing your risk of empathic distress. It can even affect your judgment, causing you to go against your morals based on the empathy you feel for someone else.

Impact of Empathy

Your ability to experience empathy can impact your relationships. Studies involving siblings have found that when empathy is high, siblings have less conflict and more warmth toward each other. In romantic relationships, having empathy increases your ability to extend forgiveness .

Not everyone experiences empathy in every situation. Some people may be more naturally empathetic in general, but people also tend to feel more empathetic toward some people and less so toward others. Some of the factors that play a role in this tendency include:

- How you perceive the other person

- How you attribute the other individual's behaviors

- What you blame for the other person's predicament

- Your past experiences and expectations

Research has found that there are gender differences in the experience and expression of empathy, although these findings are somewhat mixed. Women score higher on empathy tests, and studies suggest that women tend to feel more cognitive empathy than men.

At the most basic level, there appear to be two main factors that contribute to the ability to experience empathy: genetics and socialization. Essentially, it boils down to the age-old relative contributions of nature and nurture .

Parents pass down genes that contribute to overall personality, including the propensity toward sympathy, empathy, and compassion. On the other hand, people are also socialized by their parents, peers, communities, and society. How people treat others, as well as how they feel about others, is often a reflection of the beliefs and values that were instilled at a very young age.

Barriers to Empathy

Some people lack empathy and, therefore, aren't able to understand what another person may be experiencing or feeling. This can result in behaviors that seem uncaring or sometimes even hurtful. For instance, people with low affective empathy have higher rates of cyberbullying .

A lack of empathy is also one of the defining characteristics of narcissistic personality disorder . Though, it is unclear whether this is due to a person with this disorder having no empathy at all or having more of a dysfunctional response to others.

A few reasons why people sometimes lack empathy include cognitive biases, dehumanization, and victim-blaming.

Cognitive Biases

Sometimes the way people perceive the world around them is influenced by cognitive biases . For example, people often attribute other people's failures to internal characteristics, while blaming their own shortcomings on external factors.

These biases can make it difficult to see all the factors that contribute to a situation. They also make it less likely that people will be able to see a situation from the perspective of another.

Dehumanization

Many also fall victim to the trap of thinking that people who are different from them don't feel and behave the same as they do. This is particularly common in cases when other people are physically distant.

For example, when they watch reports of a disaster or conflict in a foreign land, people might be less likely to feel empathy if they think that those who are suffering are fundamentally different from themselves.

Victim Blaming

Sometimes, when another person has suffered a terrible experience, people make the mistake of blaming the victim for their circumstances. This is the reason that victims of crimes are often asked what they might have done differently to prevent the crime.

This tendency stems from the need to believe that the world is a fair and just place. It is the desire to believe that people get what they deserve and deserve what they get—and it can fool you into thinking that such terrible things could never happen to you.

Causes of Empathy

Human beings are certainly capable of selfish, even cruel, behavior. A quick scan of the news quickly reveals numerous unkind, selfish, and heinous actions. The question, then, is why don't we all engage in such self-serving behavior all the time? What is it that causes us to feel another's pain and respond with kindness ?

The term empathy was first introduced in 1909 by psychologist Edward B. Titchener as a translation of the German term einfühlung (meaning "feeling into"). Several different theories have been proposed to explain empathy.

Neuroscientific Explanations

Studies have shown that specific areas of the brain play a role in how empathy is experienced. More recent approaches focus on the cognitive and neurological processes that lie behind empathy. Researchers have found that different regions of the brain play an important role in empathy, including the anterior cingulate cortex and the anterior insula.

Research suggests that there are important neurobiological components to the experience of empathy. The activation of mirror neurons in the brain plays a part in the ability to mirror and mimic the emotional responses that people would feel if they were in similar situations.

Functional MRI research also indicates that an area of the brain known as the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) plays a critical role in the experience of empathy. Studies have found that people who have damage to this area of the brain often have difficulty recognizing emotions conveyed through facial expressions .

Emotional Explanations

Some of the earliest explorations into the topic of empathy centered on how feeling what others feel allows people to have a variety of emotional experiences. The philosopher Adam Smith suggested that it allows us to experience things that we might never otherwise be able to fully feel.

This can involve feeling empathy for both real people and imaginary characters. Experiencing empathy for fictional characters, for example, allows people to have a range of emotional experiences that might otherwise be impossible.

Prosocial Explanations

Sociologist Herbert Spencer proposed that empathy served an adaptive function and aided in the survival of the species. Empathy leads to helping behavior, which benefits social relationships. Humans are naturally social creatures. Things that aid in our relationships with other people benefit us as well.

When people experience empathy, they are more likely to engage in prosocial behaviors that benefit other people. Things such as altruism and heroism are also connected to feeling empathy for others.

Tips for Practicing Empathy

Fortunately, empathy is a skill that you can learn and strengthen. If you would like to build your empathy skills, there are a few things that you can do:

- Work on listening to people without interrupting

- Pay attention to body language and other types of nonverbal communication

- Try to understand people, even when you don't agree with them

- Ask people questions to learn more about them and their lives

- Imagine yourself in another person's shoes

- Strengthen your connection with others to learn more about how they feel

- Seek to identify biases you may have and how they affect your empathy for others

- Look for ways in which you are similar to others versus focusing on differences

- Be willing to be vulnerable, opening up about how you feel

- Engage in new experiences, giving you better insight into how others in that situation may feel

- Get involved in organizations that push for social change

A Word From Verywell

While empathy might be lacking in some, most people are able to empathize with others in a variety of situations. This ability to see things from another person's perspective and empathize with another's emotions plays an important role in our social lives. Empathy allows us to understand others and, quite often, compels us to take action to relieve another person's suffering.

Reblin M, Uchino BN. Social and emotional support and its implication for health . Curr Opin Psychiatry . 2008;21(2):201‐205. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f3ad89

Cleveland Clinic. Empathy fatigue: How stress and trauma can take a toll on you .

Duarte J, Pinto-Bouveia J, Cruz B. Relationships between nurses' empathy, self-compassion and dimensions of professional quality of life: A cross-sectional study . Int J Nursing Stud . 2016;60:1-11. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.02.015

Chikovani G, Babuadze L, Iashvili N, Gvalia T, Surguladze S. Empathy costs: Negative emotional bias in high empathisers . Psychiatry Res . 2015;229(1-2):340-346. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.001

Lam CB, Solmeyer AR, McHale SM. Sibling relationships and empathy across the transition to adolescence . J Youth Adolescen . 2012;41:1657-1670. doi:10.1007/s10964-012-9781-8

Kimmes JG, Durtschi JA. Forgiveness in romantic relationships: The roles of attachment, empathy, and attributions . J Marital Family Ther . 2016;42(4):645-658. doi:10.1111/jmft.12171

Kret ME, De Gelder B. A review on sex difference in processing emotional signals . Neuropsychologia . 2012; 50(7):1211-1221. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.12.022

Schultze-Krumbholz A, Scheithauer H. Is cyberbullying related to lack of empathy and social-emotional problems? Int J Develop Sci . 2013;7(3-4):161-166. doi:10.3233/DEV-130124

Baskin-Sommers A, Krusemark E, Ronningstam E. Empathy in narcissistic personality disorder: From clinical and empirical perspectives . Personal Dis Theory Res Treat . 2014;5(3):323-333. doi:10.1037/per0000061

Decety, J. Dissecting the neural mechanisms mediating empathy . Emotion Review . 2011; 3(1): 92-108. doi:10.1177/1754073910374662

Shamay-Tsoory SG, Aharon-Peretz J, Perry D. Two systems for empathy: A double dissociation between emotional and cognitive empathy in inferior frontal gyrus versus ventromedial prefrontal lesions . Brain . 2009;132(PT3): 617-627. doi:10.1093/brain/awn279

Hillis AE. Inability to empathize: Brain lesions that disrupt sharing and understanding another's emotions . Brain . 2014;137(4):981-997. doi:10.1093/brain/awt317

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Learn How to Write a Perfect Empathy Essay

Are you having a hard time, finding good tips and tricks on writing an empathy essay? Of course, writing it gets easy when you have the proper guidelines. Such as the professional research paper writers have for you in this interesting blog post.

Writing an empathy essay is like delving into understanding emotions, seeing things from other’s perspectives, and showing care and understanding. It talks about how empathy shapes relationships, impacts society, and why it’s vital for a kinder world.

No need to fret, as this blog post is like a friendly guide for beginners that will help them understand everything about writing an empathy essay. So, without further ado, let’s get started.

Table of Contents

What is an Empathy Essay?

An empathy essay or emotions essay revolves around the exploration and analysis of empathy as a concept, trait, or practice. It’s about exploring and analyzing what empathy is all about, whether it’s a concept, a trait, or something you have to practice. You know, getting into the nitty-gritty of understanding emotions, different perspectives, and how we can relate to other people’s experiences.

The point of this essay is to show how empathy is super important in relationships, connections between people, and even in society as a whole. It’s all about showing how empathy plays a big role and why it’s so important.

Key elements in empathy writing include a clear definition and explanation of empathy, supported by relatable anecdotes or case studies to illustrate its application. It should delve into empathy’s psychological and societal implications, discussing its effects on individual well-being, relationships, and society at large. Moreover, the empathy essays require a balanced exploration of challenges and complexities related to empathy, such as cultural differences, biases, and the boundaries of empathy in various situations.

Students might find it useful to consider a professional paper writing service for an empathy essay due to various reasons. These services often provide access to experienced writers who specialize in crafting well-researched and structured essays. Professional writers can offer a fresh perspective, present nuanced arguments, and ensure the essay meets academic standards.

Why Empathy Essay Writing is Challenging for Some Students?

Writing an essay with empathy can pose challenges for students due to several reasons.

Complex Nature of Empathy

Understanding empathy involves navigating emotional intelligence, perspective-taking, and compassionate understanding, which can be challenging to articulate coherently.

Subjectivity and Personal Experience

Expressing subjective feelings and personal experiences while maintaining objectivity in empathic writing can be difficult for students.

Navigating Sensitivity

Addressing sensitive topics and human complexities while maintaining a respectful and empathetic tone in writing can be demanding.

Handling Diverse Perspectives

Grasping and objectively presenting diverse perspectives across different cultural and social contexts can pose a challenge.

Time Constraints and Academic Pressures

Juggling multiple assignments and deadlines might limit the time and focus students can dedicate to thoroughly researching and crafting an empathy essay.

Expert Tips on Writing a Perfect Empathy Essay

Here are some tips with corresponding examples for writing an empathy essay:

Start with a Compelling Story

Begin your essay with a narrative that illustrates empathy in action. For instance, recount a personal experience where you or someone else demonstrated empathy. For instance:

Example: As a child, I vividly recall a moment when my grandmother’s empathetic nature became evident. Despite her own struggles, she always took time to comfort others, such as when she helped a neighbor through a difficult loss.

Define Empathy Clearly

Define empathy and its various dimensions using simple language.

Example: Empathy goes beyond sympathy; it’s about understanding and feeling what someone else is experiencing. It involves recognizing emotions and responding with care and understanding.

Use Real-life Examples

For achieving empathy in writing, incorporate real-life instances or case studies to emphasize empathy’s impact.

Example: Research shows how empathy in healthcare professionals led to improved patient outcomes. Doctors who showed empathy were found to have patients with higher satisfaction rates and better recovery.

Explore Perspectives

Discuss different perspectives on empathy and its challenges.

Example: While empathy is crucial, cultural differences can sometimes pose challenges. For instance, what’s considered empathetic in one culture might differ in another, highlighting the need for cultural sensitivity.

Highlight Benefits

Explain the positive outcomes of empathy in various contexts.

Example: In workplaces, empathy fosters a more cohesive team environment. A study by the researcher found that leaders who display empathy tend to have more engaged and motivated teams.

Acknowledge Challenges

Address the complexities or limitations of empathy.

Example: Despite its benefits, there are challenges in maintaining boundaries in empathetic relationships. It’s important to balance being empathetic and avoiding emotional burnout.

Conclude with Impact

Wrap up by emphasizing the broader impact of empathy.

Example: Ultimately, fostering empathy creates a ripple effect, contributing to a more compassionate and understanding society, where individuals feel seen, heard, and supported.

Steps of Writing an Empathy Essay

Here are the steps for writing an empathy essay. You’ll notice that most of the steps are the same as writing a research paper or any such academic task.

Understanding the Topic

Familiarize yourself with the concept of empathy and its various dimensions. Define what empathy means to you and what aspects you aim to explore in your essay.

Gather information from credible sources, including academic articles, books, and real-life examples that illustrate empathy’s role and impact. Take notes on key points and examples that you can incorporate into your essays on empathy

Create an outline that includes an introduction (with a thesis statement defining the scope of your essay), body paragraphs discussing different aspects of empathy (such as its definition, importance, challenges, and benefits), and a conclusion summarizing the main points.

Introduction

Start your essay with a compelling hook or anecdote related to empathy. Introduce the topic and provide a clear thesis statement outlining what you’ll discuss in the essay.

Body Paragraphs

Each paragraph should focus on a specific aspect of empathy supported by evidence or examples. Discuss empathy’s definition, its significance in different contexts (personal, societal, professional), challenges in practicing empathy, benefits, and potential limitations.

Use Examples

Incorporate real-life examples or case studies to illustrate your points and make them relatable to the reader.

Address Counterarguments

Acknowledge differing perspectives or potential counterarguments related to empathy and address them thoughtfully within your essay.

Summarize the main points discussed in the essay. Restate the significance of empathy and its impact, leaving the reader with a lasting impression or call to action.

Edit and Revise

Review your essay for coherence, clarity, and consistency. Check for grammar, punctuation, and spelling errors. Ensure that your ideas flow logically and that your essay effectively communicates your thoughts on empathy.

Make any necessary revisions based on feedback or additional insights. Ensure that your essay meets the guidelines and requirements if it’s for a specific assignment. Then, finalize and submit your empathy essay.

Final Thoughts

In this blog post, we’ve tried to make writing an empathy essay easier for students. We’ve explained it step by step, using easy examples and clear explanations. The goal is to help students understand what empathy is and how to write about it in an essay.

The steps we’ve shared for writing an empathy essay are straightforward. They start with understanding the topic and doing research, then move on to outlining, writing, and polishing the essay. We’ve highlighted the importance of using personal stories, real-life examples, and organizing ideas well.

Students can benefit from our assignment writing service for their empathy essays. Our experienced writers can provide expert help, ensuring the essays meet academic standards and are well-written. This support saves time and helps students focus on other schoolwork while getting a top-notch empathy essay.

Order Original Papers & Essays

Your First Custom Paper Sample is on Us!

Timely Deliveries

No Plagiarism & AI

100% Refund

Try Our Free Paper Writing Service

Related blogs.

Connections with Writers and support

Privacy and Confidentiality Guarantee

Average Quality Score

Empathy 101: 3+ Examples and Psychology Definitions

Has a book, film, or photograph ever driven you to tears?

Or have you ever felt driven to ease someone else’s emotions?

If you have answered yes to at least one of these, then you have experienced empathy.

Empathy is a complex psychological process that allows us to form bonds with other people. Through empathy, we cry when our friends go through hard times, celebrate their successes, and rage during their times of hardship. Empathy also allows us to feel guilt, shame, and embarrassment, as well as understand jokes and sarcasm.

In this article, we explore empathy, its benefits, and useful ways to measure it. We also look at empathy fatigue – a common experience among clinicians and people in the caring professions – and provide beneficial resources.

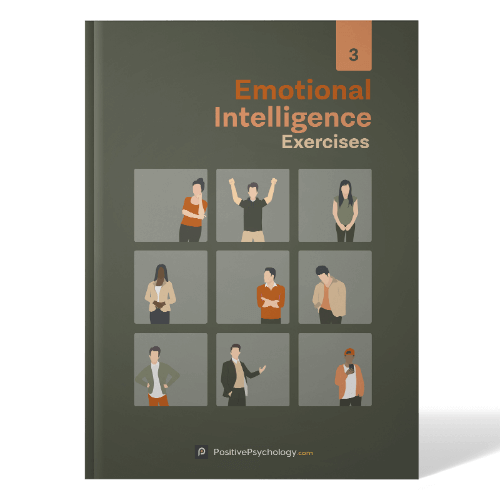

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Emotional Intelligence Exercises for free . These science-based exercises will not only enhance your ability to understand and work with your emotions but will also give you the tools to foster the emotional intelligence of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains

What is empathy in psychology, the empathy quotient, 7 real-life examples, is it important 3+ benefits of empathy, empathy vs sympathy and compassion, assessing empathy: 4 helpful questionnaires, a note on empathy fatigue, positivepsychology.com resources, a take-home message.

In psychology, empathy is loosely defined as an ability to understand and experience someone else’s feelings and to adopt someone else’s viewpoint (Colman, 2015). The term ‘empathy’ comes from the German word Einfuhlung, which means “projecting into” (Ganczarek, Hünefeldt, & Belardinelli, 2018) and may explain why empathy is considered the ability to place yourself in someone else’s shoes.

Difficulties with defining empathy

Defining empathy clearly and exhaustively enough to be studied in psychology is difficult. For example, is empathy the ability to understand or feel or share or interpret someone else’s feelings?

Each of these verbs differs slightly, providing a different meaning to empathy. As a result, the underlying psychological mechanism and part of the brain responsible for empathy also differ.

Part of the difficulty defining empathy is that it comprises multiple components. For example, Hoffman (1987) argued that empathy in children develops across four different stages and that each stage lays down the foundation for the next.

These four stages are:

- Global empathy or ‘emotion contagion,’ where one person’s emotion evokes the same emotional reaction in another person (or the observer).

- Attention to others’ feelings, where the observer is aware of another person’s feelings but doesn’t mirror them.

- Prosocial actions, where the observer is aware of another person’s feelings and behaves in a way to comfort the other person.

- Empathy for another’s life condition, where the observer feels empathy toward someone else’s broader life situation, rather than their immediate situation right at this instance.

Fletcher-Watson and Bird (2020) provide an excellent overview of the challenges associated with defining and studying empathy. They argue that empathy results from a four-step process:

- Step 1: Noticing/observing someone’s emotional state

- Step 2: Correctly interpreting that emotional state

- Step 3: ‘Feeling’ the same emotion

- Step 4: Responding to the emotion

Empathy is not achieved if any of these four steps fail.

This multi-component conception of empathy is echoed across other research. For example, Decety and Cowell (2014) also posit that empathy arises from multiple processes interacting with each other.

These processes are:

- Emotional: The ability to share someone else’s feelings

- Motivational: The need to respond to someone else’s feelings

- Cognitive: The ability to take someone else’s viewpoint

Part of this confusion stems from their corresponding definitions.

Empathy is the ability to share someone else’s emotions and perspectives. Emotional intelligence is the ability to understand, interpret, and manage other people’s emotions, as well as your own. This last inclusion – your own emotions – is what distinguishes emotional intelligence from empathy.

The Empathy Quotient is a measurement of empathy (Baron-Cohen & Wheelwright, 2004). It is akin to the Intelligence Quotient (IQ) but is a measure of empathy rather than intelligence. Like IQ, higher scores of the Empathy Quotient are meant to represent higher abilities of empathy.

Importantly, the Empathy Quotient differs from the Emotional Quotient. Emotional Quotient is measured using the BarOn Emotional Quotient-Inventory (Bar-On, 2004) and aims to measure emotional intelligence rather than empathy. It’s easy to confuse them because “EQ” is used to refer to both.

To determine whether the Empathy Quotient is a suitable test of empathy, Baron-Cohen and Wheelwright (2004) administered the measurement to a group of neurotypical people and a group of people diagnosed with Asperger syndrome and compared their scores.

On average, individuals with Asperger syndrome scored significantly lower than neurotypical people. From this study, a score of 30 was determined to be a critical cut-off mark. Scores less than 30 were typically found among the participants with Asperger syndrome. Furthermore, the test-retest reliability of the Empathy Quotient was high, suggesting that the test reliably measures empathy.

Download 3 Free Emotional Intelligence Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients understand and use emotions advantageously.

Download 3 Free Emotional Intelligence Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

Since empathy is so complex and involved in so many social interactions, there are many examples of empathy in the real world.

In a discussion with a friend, have you ever felt so moved that you experienced the same emotion that they did? Or maybe a friend shared a cringe-worthy story of sheer humiliation, and that feeling was mirrored in you.

These situations when you experienced the same emotions as your friends are examples of empathy. Other examples of empathy include understanding someone else’s point of view during an argument, feeling guilty when you realize why someone might have misunderstood what you said, or realizing something you said was a faux pas . These scenarios require you to take someone else’s viewpoint.

Some of the best examples of empathy can be found in the work by Oliver Sacks and Atul Gawande. Sacks was a neurologist who had a profound impact through his thoughtful, patient-driven books on the field of psychiatry and neuropsychology.

Atul Gawande is a surgeon who worked with the World Health Organization and has published several books on improving healthcare and healthcare systems. Both authors address their patients in a sensitive, thoughtful manner that evokes a lot of empathy in the reader.

The following books are highly recommended:

- Awakenings by Oliver Sacks

- The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat by Oliver Sacks

- Being Mortal by Atul Gawande

We participate in many scenarios in which we convey and receive information with other people, verbally and nonverbally.

Regardless of whether or not these interactions are important, we have to perceive, interpret, and respond to numerous cues.

Empathy is more than ‘just’ the ability to feel what someone else is feeling. Empathy is an essential skill that allows us to effectively engage with other people in social contexts (Baron-Cohen & Wheelwright, 2004).

Without empathy, we would struggle to:

- understand other people’s feelings, motivations, and behaviors;

- respond appropriately to someone else’s feelings; and

- understand social interactions that rely on subtle behaviors, cues, and social norms, such as jokes, faux pas, and sarcasm.

The ability to respond appropriately to someone else’s emotions is extremely important for forming bonds. Empathy underlines the bond that forms between parent and child (Decety & Cowell, 2014).

Some researchers even consider some aspects of empathy to be a defining feature of humans. Our ability to consider another person’s viewpoint is considered uniquely human (Decety & Cowell, 2014).

Jean Decety and Jason Cowell (2014) argue that empathy is one process that contributes to understanding and engaging in complex social behavior, such as prosocial behavior, which includes volunteering as well as providing care for people who are terminally ill.

Earlier in this article, we mentioned the studies by Baron-Cohen and Wheelwright (2004) in which they compared Empathy Quotient scores between people with Asperger syndrome and neurotypical people.

People on the autism–Asperger spectrum are believed to have a diminished capacity for empathy and, as a result, struggle with social contexts. However, their lower empathy scores do not mean that they are without feeling or should be considered psychopaths (who also have lower scores of empathy).

People on the autism spectrum often report that their intention is not to hurt other people’s feelings, and they feel guilty if they caused someone else’s hurt feelings (Baron-Cohen & Wheelwright, 2004).

Furthermore, people on the autism spectrum often report that they want human connections; however, they struggle to make them because they are not aware of how their behavior affects how other people perceive them (Baron-Cohen & Wheelwright, 2004). This shows how important empathy is in developing relationships and interpreting subtle social cues.

The three terms – empathy, sympathy, and compassion – are often confused with each other, because they are often used when referring to someone else’s feelings. For example, in response to a friend’s bad news, do you feel empathy, sympathy, or compassion? The terms are used in similar contexts, but they refer to different behaviors.

- From the definitions provided above, empathy involves interpreting, understanding, feeling, and acting on other people’s feelings. Empathy is a multidimensional process and relies on affective, cognitive, behavioral, and moral components (Jeffrey, 2016). Remember, empathy is the ability to adopt someone else’s viewpoint or to put yourself into someone else’s shoes.

- Sympathy is the feeling of pity for someone else’s misfortune or circumstances.

- Compassion is the desire and act of wanting to alleviate someone else’s suffering. Compassion includes the affective components of empathy and sympathy, but it is accompanied by an action to change the circumstances of the person who is suffering (Sinclair et al., 2017). A compassionate act can also result in our suffering alongside the other person; this is referred to as co-suffering. Compassion is also linked to altruistic behavior (Jeffrey, 2016).

Examples of Empathy vs Sympathy vs Compassion

To further cement the difference between these three terms, consider the following examples:

Emma relays a recent event where she was extremely embarrassed. As she retells the story, her friend, Tamika, groans and mutters “Oh my word, I would feel so embarrassed. I would want the world to swallow me whole!”

In this example, Tamika doesn’t actually want to disappear into a hole. Instead, she’s correctly understanding and interpreting the situation that Emma found herself in. She is most likely experiencing empathy for Emma’s situation. She is not feeling pity, nor is she acting compassionately.

Jerome’s mother recently suffered a near-fatal heart attack. He listens to his mother retell her sisters about her experience. As she recounts her experience, she starts crying, because she was so afraid, and she realized that she might never see her loved ones again. Jerome starts crying as he listens to his mother.

In this example, Jerome is feeling sympathy (pity) for his mother and what she went through.

On his route to university, Jamal sees the same homeless man every day. The homeless man sits in the same place, regardless of the weather, with a sign next to him that asks for assistance. Jamal decides to donate some of his clothing to the homeless man.

Jamal’s behavior is an act of compassion . By donating his clothing, he is trying to alleviate the homeless man’s suffering. He may also be experiencing sympathy towards the man, but the act of trying to change the man’s situation is an act of compassion.

Use these questionnaires to determine what your current level of empathy is.

Empathy Quotient

The Empathy Quotient, including the entire questionnaire, its psychometric properties, and the scoring, is described in the original paper by Baron-Cohen and Wheelwright (2004). Professor Simon Baron-Cohen works with the Autism Research Centre (ARC), and the 60-item Empathy Quotient, as well as the scoring matrix, is available from the ARC website .

The Empathy Questionnaire (EmQue)

The Empathy Questionnaire (EmQue), designed by Rieffe, Ketelaar, and Wiefferink (2010), measures empathy in young children (average age of around 30 months) and reflects Hoffman’s (1987) theory of how empathy developed in children.

The questionnaire comprises three subscales, which map onto the first three stages of empathy development posited by Hoffman (1987). The questionnaire correlates well with other measures that aim to capture similar constructs. You can access this questionnaire on the Academia website .

The Empathy Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents (EmQue-CA)

A similar version of the EmQue also exists for older children. This version is known as the Empathy Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents (EmQue-CA; Overgaauw, Rieffe, Broekhof, Crone, & Güroğlu, 2017).

Unlike the EmQue, the EmQue-CA is a self-report measure. In other words, the adolescents and children must answer how much they agree with each statement, rather than their parents observing their behaviors.

The final version of the EmQue-CA measures the following three subscales: affective empathy, cognitive empathy, and intention to comfort. The 14 questions and the psychometric properties of the questionnaire are reported in the original paper, which can be accessed on the Frontiers in Psychology website as a free downloadable PDF .

The Toronto Empathy Questionnaire (TEQ)

The Toronto Empathy Questionnaire (TEQ) was developed by refining a collection of questionnaires that measure empathy into a core set of questions (Spreng, McKinnon, Mar, & Levine, 2009).

Researchers collected questions from multiple empathy questionnaires, administered these questions to a large sample of students, and then using exploratory factor analysis, refined the questions to a core set of 16.

The questionnaire and scoring rules are described in the appendix of the original paper (Spreng et al., 2009), which can be accessed on the Measurement Instrument Database for the Social Sciences .

Finally, the TEQ and the Empathy Quotient have a strong, positive correlation, confirming that the questions in both measure the same psychological construct.

Empathy is often confused with sympathy, which involves a lack of truly understanding another person’s experience.

For instance, if your friend recently lost their job, expressing sympathy would include feeling sorry for them and wishing them luck finding another job.

In contrast, empathy entails relating to your friend’s frustrations and fears about unemployment and actively experiencing those negative emotions by putting yourself in their shoes.

An example of compassion would be assisting your friend in applying for other jobs and updating their resume.

While empathy and sympathy drive acts of compassion, compassion stands out due to its proactive nature of motivating individuals to alleviate suffering.

Recognizing the distinctions between sympathy, empathy, and compassion can help you adjust your emotional responses when someone is going through hardship, enabling you to provide better support.

Feeling empathy is a very useful skill, especially for health professionals such as clinicians, therapists, and psychologists. But the ability to feel empathy for other people comes at the cost of empathy fatigue.

Empathy fatigue refers to the feeling of exhaustion that health professionals experience in response to constantly revisiting their emotional wounds through their clients’ experience (Stebnicki, 2000). For example, a therapist whose client is going through bereavement may be reminded of their own grief and trauma.

By being emotionally available for their client through emotional and stressful periods, the therapist experiences fatigue at a psychological, emotional, and physiological level (Stebnicki, 2000).

Besides manifesting as a sense of fatigue, we can consider empathy fatigue as a form of re-trauma, and as a result, the symptoms resemble that of secondary traumatic stress disorder.

Empathy fatigue in the clinical domain is also referred to as ‘counselor impairment’ because the clinician’s ability to perform their job is impaired (Stebnicki, 2007). An outcome of empathy fatigue is burnout, with a particularly sudden onset (Stebnicki, 2000).

Stebnicki (2007) provides a comprehensive list of strategies that clinicians can use to prevent empathy fatigue:

- Self-awareness of the symptoms of empathy fatigue

- Self-care strategies and lifestyle behaviors that protect the clinician from empathy fatigue

- Using a support group and supervisor during periods of empathy fatigue

Finally, PositivePsychology.com’s post detailing self-care for therapists can be easily adapted to other industries. For example, these tips could be incorporated into a wellness session in the workplace to help prevent empathy fatigue.

17 Exercises To Develop Emotional Intelligence

These 17 Emotional Intelligence Exercises [PDF] will help others strengthen their relationships, lower stress, and enhance their wellbeing through improved EQ.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

Below is a list of four items, each targeting a different aspect of empathy.

To help children better understand what is meant by empathy, we recommend the What is Empathy? worksheet. In this worksheet, children are asked to recall scenarios when they experienced a similar emotion as someone else. Children are also asked to think of reasons why empathy is a good thing and how they can improve their sense of empathy.

To practice looking at things from a fresh perspective, we recommend the 500 Years Ago Worksheet and the Trading Places Worksheet. Both worksheets can be used in group exercises, but only the second one is also appropriate for individual clients.

In five steps, the Listening Accurately Worksheet lays out an easy-to-follow guide to better develop empathy through active listening .

This worksheet is especially useful for clinicians and health professionals but is also very appropriate for anyone working in a profession where they need to communicate with other people constantly.

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others develop emotional intelligence, this collection contains 17 validated EI tools for practitioners. Use them to help others understand and use their emotions to their advantage.

If we show a little tolerance and humility, and if we are willing to stand in the other person’s shoes — as my mom would say — just for a moment, stand in their shoes. Because here’s the thing about life: there’s no accounting for what fate will deal you. Some days, when you need a hand. There are other days when we’re called to lend a hand.

U.S. President Joseph R. Biden, Jr., Inauguration speech

And that is what empathy is: being able to put yourself in someone else’s shoes. Humans are social creatures, and empathy is an important skill. Without empathy, we will struggle to connect and form bonds. Underdeveloped empathy results in awkward social interactions, which can also weaken social bonds.

No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.

By connecting, by understanding, by having empathy, we can all stand together, lend a hand when needed, and be given a hand when we, in turn, may need it.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Emotional Intelligence Exercises for free .

- Bar-On, R. (2004). The Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i): Rationale, description and summary of psychometric properties. In G. Geher (Ed.), Measuring emotional intelligence: Common ground and controversy (pp. 115–145). Nova Science Publishers.

- Baron-Cohen, S., & Wheelwright, S. (2004). The Empathy Quotient: An investigation of adults with Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism, and normal sex differences. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders , 34 (2), 163–175.

- Colman, A. M. (2015). A dictionary of psychology . Oxford University Press.

- Decety, J., & Cowell, J. M. (2014). The complex relation between morality and empathy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences , 18 , 337–339.

- Fletcher-Watson, S., & Bird, G. (2020). Autism and empathy: What are the real links? Autism , 24 (1), 3–6.

- Ganczarek, J., Hünefeldt, T., & Belardinelli, M. O. (2018). From “Einfühlung” to empathy: Exploring the relationship between aesthetic and interpersonal experience. Cognitive Processing , 19 (4), 141–145.

- Gawande, A. (2017). Being mortal: Medicine and what matters in the end. Picador.

- Hoffman, M. L. (1987). The contribution of empathy to justice and moral judgment. In N. Eisenberg & J. Strayer (Eds.), Cambridge studies in social and emotional development. Empathy and its development (pp. 47–80). Cambridge University Press.

- Jeffrey, D. (2016). Empathy, sympathy and compassion in healthcare: Is there a problem? Is there a difference? Does it matter? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine , 109 (12), 446–452.

- John Donne. (2020, October 17). Wikiquote . Retrieved January 20, 2021, from https://en.wikiquote.org/w/index.php?title=John_Donne&oldid=2878168

- Overgaauw, S., Rieffe, C., Broekhof, E., Crone, E. A., & Güroğlu, B. (2017). Assessing empathy across childhood and adolescence: Validation of the Empathy Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents (EmQue-CA). Frontiers in Psychology , 8 , Article 870.

- Rieffe, C., Ketelaar, L., & Wiefferink, C. H. (2010). Assessing empathy in young children: Construction and validation of an Empathy Questionnaire (EmQue). Personality and Individual Differences , 49 (5), 362–367.

- Sacks, O. (1998). The man who mistook his wife for a hat: And other clinical tales. Touchstone.

- Sacks, O. W. (2011). Awakenings (New ed.). Picador.

- Sinclair, S., Beamer, K., Hack, T. F., McClement, S., Raffin Bouchal, S., Chochinov, H. M., & Hagen, N. A. (2017). Sympathy, empathy, and compassion: A grounded theory study of palliative care patients’ understandings, experiences, and preferences. Palliative Medicine , 31 (5), 437–447.

- Spreng, R. N., McKinnon, M. C., Mar, R. A., & Levine, B. (2009). The Toronto Empathy Questionnaire: Scale development and initial validation of a factor-analytic solution to multiple empathy measures. Journal of Personality Assessment , 91 (1), 62–71.

- Stebnicki, M. A. (2000). Stress and grief reactions among rehabilitation professionals: Dealing effectively with empathy fatigue. Journal of Rehabilitation , 66 (1).

- Stebnicki, M. A. (2007). Empathy fatigue: Healing the mind, body, and spirit of professional counselors. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation , 10 (4), 317–338.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Im positive that the origin of the word ’empathy’ comes from Greek, with ‘pathos’ being an umbrella word for emotions (sympathy, apathy, antipathy, and from there passion, compassion etc).

It’s important to mention that empathy is not a sign of a weak personality. I did a huge work before I could finally cry when touched by my friend’s story. Because “men shouldn’t show their tears in public.” But don’t you dare tell me how I should react! 😀

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

What Is Compassion Fatigue? 24 Causes & Symptoms Explained

Are you in a caring profession? If so, do you ever feel preoccupied with the suffering of the people you work with? In a helping [...]

How to Prevent and Treat Compassion Fatigue + Tests

The wide range of circumstances experienced by counselors and therapists leaves them open and vulnerable to experiencing compassion fatigue (Negash & Sahin, 2011). Such a [...]

Living With the Inner Critic: 8 Helpful Worksheets (+ PDF)

We all know this voice in our head that constantly criticizes, belittles, and judges us. This voice has many names: inner critic, judge, saboteur, the [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (58)

- Compassion (25)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (29)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (15)

- Positive Psychology (34)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (43)

- Resilience & Coping (37)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (63)

Download 3 Free Self-Compassion Tools Pack (PDF)

3 Self-Compassion Tools (PDF)

Despite its linguistic roots in ancient Greek, the concept of empathy is of recent intellectual heritage. Yet its history has been varied and colorful, a fact that is also mirrored in the multiplicity of definitions associated with the empathy concept in a number of different scientific and non-scientific discourses. In its philosophical heyday at the turn of the 19 th to the 20 th century, empathy had been hailed as the primary means for gaining knowledge of other minds and as the method uniquely suited for the human sciences, only to be almost entirely neglected philosophically for the rest of the century. Only recently have philosophers become again interested in empathy in light of the debate about our folk psychological mindreading capacities. In the second half of the last century, the task of addressing empathy was mainly left to psychologists who thematized it as a psychological phenomenon and process to be studied by the method of the empirical sciences. Particularly, it has been studied by social psychologists as a phenomenon assumed to be causally involved in creating prosocial attitudes and behavior. Nevertheless, within psychology it is at times difficult to find agreement of how exactly one should understand empathy; a fact of which psychologists themselves have become increasingly aware. The purpose of this entry is to clarify the concept of empathy by surveying its history in various philosophical and psychological discussions and by indicating why empathy was and should be regarded to be of such central importance in understanding human agency in ordinary contexts, in the human sciences and for the constitution of ourselves as social and moral agents.

1. Historical Introduction

- 2.1 Mirror Neurons, Simulation, and the Philosophical Revival of Empathy

3.1. The Critique of Empathy in the Context of a Hermeneutic Conception of the Human Sciences

3.2. the critique of empathy within the context of a naturalist conception of the human sciences, 4. empathy as a topic of scientific exploration in psychology, 5.1. empathy and altruistic motivation, 5.2. empathy, moral development, and moral agency, 6. conclusion, bibliography, other internet resources, related entries.

The psychologist Edward Titchener (1867-1927) introduced the term “empathy” in 1909 into the English language as the translation of the German term “Einfühlung” (or “feeling into”), a term that by the end of the 19 th century was in German philosophical circles understood as an important category in philosophical aesthetics. Even in Germany its use as a technical term of philosophical analysis did not have a long tradition. Various philosophers certainly speak throughout the 19 th century and the second half of the 18 th century in a more informal manner about our ability to “feel into” works of arts and into nature. Particularly important here is the fact that romantic thinkers, such as Herder and Novalis, viewed our ability to feel into nature as a vital corrective against the modern scientific attitude of merely dissecting nature into its elements; instead of grasping its underlying spiritual reality through a process of poetic identification. But in using mainly the verbal form in referring to our ability to feel into various things they do not treat such an ability as a topic that is worthy of sustained philosophical reflection and analysis. Robert Visher was the first to introduce the term “Einfühlung” in a more technical sense—and in using the substantive form he indicates that it is a worthy object of philosophical analysis—in his “On the Optical Sense of Form: A contribution to Aesthetics” (1873).

It was however Theodor Lipps (1851-1914) who scrutinized empathy in the most thorough manner. Most importantly, Lipps not only argued for empathy as a concept that is central for the philosophical and psychological analysis of our aesthetic experiences. His work transformed empathy from a concept of philosophical aesthetics into a central category of the philosophy of the social and human sciences. For him, empathy not only plays a role in our aesthetic appreciation of objects. It has also to be understood as being the primary basis for recognizing each other as minded creatures. Not surprisingly, it was Lipps's conception of empathy that Titchener had in mind in his translation of “Einfühlung” as “empathy.”