To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, conducting content‐analysis based literature reviews in supply chain management.

Supply Chain Management

ISSN : 1359-8546

Article publication date: 3 August 2012

Inconsistent research output makes critical literature reviews crucial tools for assessing and developing the knowledge base within a research field. Literature reviews in the field of supply chain management (SCM) are often considerably less stringently presented than other empirical research. Replicability of the research and traceability of the arguments and conclusions call for more transparent and systematic procedures. The purpose of this paper is to elaborate on the importance of literature reviews in SCM.

Design/methodology/approach

Literature reviews are defined as primarily qualitative synthesis. Content analysis is introduced and applied for reviewing 22 literature reviews of seven sub‐fields of SCM, published in English‐speaking peer‐reviewed journals between 2000 and 2009. A descriptive evaluation of the literature body is followed by a content analysis on the basis of a specific pattern of analytic categories derived from a typical research process.

Each paper was assessed for the aim of research, the method of data gathering, the method of data analysis, and quality measures. While some papers provide information on all of these categories, many fail to provide all the information. This questions the quality of the literature review process and the findings presented in respective papers.

Research limitations/implications

While 22 literature reviews are taken into account in this paper as the basis of the empirical analysis, this allows for assessing the range of procedures applied in previous literature reviews and for pointing to their strengths and shortcomings.

Originality/value

The findings and subsequent methodological discussions aim at providing practical guidance for SCM researchers on how to use content analysis for conducting literature reviews.

- Supply chain management

- Literature review

- Research process

- Content analysis

- Replicability

- Research results

- Research methods

Seuring, S. and Gold, S. (2012), "Conducting content‐analysis based literature reviews in supply chain management", Supply Chain Management , Vol. 17 No. 5, pp. 544-555. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598541211258609

Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2012, Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

A Content-Analysis Based Literature Review in Blockchain Adoption within Food Supply Chain

Affiliations.

- 1 Blockchain Research Center of China, Southwestern University of Finance and Economics, Chengdu 611130, China.

- 2 Southampton Business School, University of Southampton, Highfield, Southampton SO17 1BJ, UK.

- 3 School of Electromechanical Engineering, Guangdong University of Technology, Guangzhou 510006, China.

- PMID: 32182951

- PMCID: PMC7084604

- DOI: 10.3390/ijerph17051784

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), one out of 10 people get sick from eating contaminated food. Complex food production process and globalization make food supply chain more delicate. Many technologies have been investigated in recent years to address food insecurity and achieve efficiency in dealing with food recalls. One of the most promising technologies is Blockchain, which has already been used successfully in financial aspects, such as bitcoin, and it is attracting interests from food supply chain organizations. As blockchain has characteristics, such as decentralization, security, immutability, smart contract, it is therefore expected to improve sustainable food supply chain management and food traceability. This paper applies a content-analysis based literature review in blockchain adoption within food supply chain. We propose four benefits. Blockchain can help to improve food traceability, information transparency, and recall efficiency; it can also be combined with Internet of things (IoT) to achieve better efficiency. We also propose five potential challenges, including lack of deeper understanding of blockchain, technology difficulties, raw data manipulation, difficulties of getting all stakeholders on board, and the deficiency of regulations.

Keywords: blockchain; food supply chain.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Blockchain*

- Food Supply*

- Open access

- Published: 29 April 2024

Development and psychometric evaluation of "Caring Ability of Mother with Preterm Infant Scale" (CAMPIS): a sequential exploratory mixed-method study

- Saleheh Tajalli ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2045-6430 1 ,

- Abbas Ebadi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2911-7005 2 ,

- Soroor Parvizy ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9361-9923 3 , 4 &

- Carole Kenner ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1573-5240 5

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 297 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Caring ability is one of the most important indicators regarding care outcomes. A valid and reliable scale for the evaluation of caring ability in mothers with preterm infants is lacking.

The present study was conducted with the aim of designing and psychometric evaluation of the tool for assessing caring ability in mothers with preterm infants.

A mixed-method exploratory design was conducted from 2021 to 2023. First the concept of caring ability of mothers with preterm infants was clarified using literature review and comparative content analysis, and a pool of items was created. Then, in the quantitative study, the psychometric properties of the scale were evaluated using validity and reliability tests. A maximum likelihood extraction with promax rotation was performed on 401 mothers with the mean age of 31.67 ± 6.14 years to assess the construct validity.

Initial caring ability of mother with preterm infant scale (CAMPIS) was developed with 64 items by findings of the literature review, comparative content analysis, and other related questionnaire items, on a 5-point Likert scale to be psychometrically evaluated. Face, content, and construct validity, as well as reliability, were measured to evaluate the psychometric properties of CAMPIS. So, the initial survey yielded 201 valid responses. The three components: 'cognitive ability'; knowledge and skills abilities'; and 'psychological ability'; explained 47.44% of the total observed variance for CAMPIS with 21 items. A subsequent survey garnered 200 valid responses. The confirmatory factor analysis results indicated: χ2/df = 1.972, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.933, and incremental fit index (IFI) = 0.933. These results demonstrate good structural, convergent, discriminant validity and reliability. OMEGA, average inter-item correlation (AIC), intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) for the entire scale were at 0.900, 0.27 and 0.91 respectively.

Based on the results of the psychometric evaluation of CAMPIS, it was found that the concept of caring ability in the Iranian mothers with preterm infants is a multi-dimensional concept, which mainly focuses on cognitive ability, technical ability, and psychological ability. The designed scale has acceptable validity and reliability characteristics that can be used in future studies to assess this concept in the mothers of preterm infants.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

In recent years, the technology advancements in the field of caring for mothers during pregnancy and delivery, and their infants resulted in increased survival of preterm infants [ 1 ]. According to the assessment of the world health organization (WHO), the prevalence of preterm birth globally is 10.6% [ 2 ].

Preterm birth is often an unexpected event for women [ 3 ], and hospitalization in the NICU is considered unavoidable [ 4 ]. The birth of a preterm infant and hospital stay in the NICU is very stressful for parents. The source of this stress includes the medical condition and parental separation from their infant. Mother-infant separation often results in the feelings of anxiety, fear, depression thus potentially decreasing the mother’s sensitivity to infant cues, which in turn, may delay infant development [ 5 ]. Many mothers experience acute stress disorder, which can last from 3 days to 1 month. It can be associated with symptoms such as troublesome memories, frequent and annoying restlessness and sadness, as well as post-traumatic stress [ 6 ].

The feeling of loss is a source of suffering and grief for the mothers of preterm infants. In the initial days following birth, the primary focus of parents is often on the infant's chances for survival. However, as time passes, this preoccupation can evolve into a potential cause of grief, anxiety, and feelings of culpability (related to an incomplete pregnancy)[ 6 ]. Therefore, in some cases, the mothers cannot focus on their preterm infants. Becoming a mother requires reorganizing and changing one’s personal identity. Mothers must change their identity from being a daughter and a wife in the generation to which they belong to being a mother for the next generation. They start this process from the pregnancy period, initially fantasizing about motherhood [ 7 ]. However, at the end of the pregnancy period, with the birth of a preterm infant, this process stops. In fact, preterm birth is a sudden stop in the process of mother's self-representation [ 8 ]. Consequently, the experience of transitioning into motherhood for women who give birth prematurely may differ from that of others. This is due to the fact that the psychological readiness and preparation required for assuming the role of a mother comes to an abrupt halt upon the premature birth of their infant. As a result, these women are forced to quickly adapt to their new circumstances [ 9 ].

Review of literature shows caring ability concept have three dimensions: cognitive, knowledge and patience [ 10 ]. Published caring ability scales evaluate ability of take care in informal caregiver of patient with cancer named ‘caring ability of family caregivers of patients with cancer scale (CAFCPCS)’ [ 11 ] or professional care giver named ‘The caring ability inventory’[ 10 ]. Also, published tools, focused on others aspects of take caring ability. So family empowerment tool named ‘Family Empowerment Scale’ [ 12 ], asses the empowerment of family members of patients with chronic disease as an outcome of taking care empowerment. The parent Engagement tool is another scale named ‘parent risk evaluation and engagement model and instrument (PREEMI)’ that evaluates parent risk evaluation and engagement of mothers with preterm infants [ 13 ]. The discharge preparedness scales were ‘perceived readiness for discharge after birth scale (PRDBS) and ‘Parent discharge readiness’ [ 14 ], that evaluate readiness for discharge. These evaluate postpartum mother’s perceptions of readiness for discharge from the hospital that was adapted from a scale measuring adult and elderly postsurgical patients’ perceptions of their readiness for discharge. Also assert for readiness is different from the ability to continue taking care after discharge. The scales 'Perceived maternal parenting self‐efficacy (PMP S‐E)' and 'Self‐efficacy in infant care scale' [ 15 , 16 ] were developed to assess the caregiver's belief in their ability to effectively care for their child, with a specific emphasis on self-confidence. These scales aim to provide a means of measuring the caregiver's expectations regarding the outcomes of their caregiving efforts. Although our previous study show a mother with optimal caring ability has sufficient cognitive ability, technical ability, and psychological ability [ 17 ]. This is a clear gap in the designed scale that could be overcome by a new scale that focuses take caring ability of mother with preterm infants. To sum up, there is no scale developed for the caring ability of mothers with preterm infants; therefore, the purpose of this study is to examine the real-life experiences of mothers with preterm infants and other professional and family. Caregivers, who have directly experienced taking care of preterm infants in order to then, design and perform the psychometric evaluation of a tool to assess the caring ability of mothers with preterm infants.

The purpose of this study was to develop a preterm caring ability scale and to examine its psychodynamic properties in mother of preterm infants with gestational age less than 32 weeks.

This study utilized a mixed-method exploratory design to develop and psychometric evaluate the caring ability of mother with preterm infant scale (CAMPIS) from July 2021 to October 2023. The research involved both mothers and professionals caring for preterm infants. The research consisted of two main phases: first, a qualitative study was conducted to generate the scale items, followed by a quantitative approach to evaluate the psychometric properties of the scale.

First step: qualitative study and item generation

The purpose of this step was to explain the concept of caring ability in the mothers of preterm infants, and to create a set of items to design the target scale. This step involved the identification of concepts through literature review published from 1995 to 2020 [ 17 ] .

In the second step, 18 semi-structured individual interviews of 60–80 min were organized to understand better the caring ability of mother with preterm infant concept. The face-to-face semi-structured interviews were conducted in a serene setting, either in the hospital room or the participants' home, as per their request and preference. The interviews involved mothers, grandmothers, and fathers, and were carried out without the presence of any other individuals. Due to the coronavirus social distance limitation, the interviews with the physicians and the nurses were conducted online and also recorded via Skyroom software.

We decided to finish the interview, when we interviewed the 18 participants, the information he/she provided is similar to those provided by the former ten participants (data saturation). Totally, 11 mothers, 2 fathers, 2 grandmothers of preterm infants, 1 neonatal nurse, and 2 neonatologists working in these wards participated in the present study. The participants were residents in the NICU in 5 hospitals in Tehran, Iran, representing a range of ages, genders, and caring role. The interview process started with a general question such as "Would you please explain mothers’ ability to take care of a preterm infant?", "In which situations do you feel she are more capable?", and "Which factors decreased her ability?" Then, based on the participant’s responses, the interviews continued with exploratory questions such as "Could you please explain more? or “Could you give an example in this regard?".

All participants were interviewed individually and each interview lasted between 60 and 80 min. The texts of the interviews were analyzed using the using Lindgern et al. [ 18 ] approach by MAXQDA software version 10. Qualitative interview resulted in initial items generation.

Second step: quantitative study and CAMPIS psychometric properties evaluation

Face validity.

Face validity was evaluated through qualitative and quantitative approaches. In the qualitative approach, the scale was sent to 10 mothers of preterm infants, they were asked to evaluate the scale in terms of difficulty, relevance, and ambiguity. The participants assessed the items based on their own judgment, ensuring that they were able to understand them. In order to further evaluate the suitability of the items, five additional mothers were included in the quantitative approach. These mothers were asked to rate the items on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from completely suitable to not suitable at all. The impact score was calculated through the following equation: impact score = frequency (%) × appropriateness. A score above 1.5 was considered acceptable [ 19 ].

Content validity

The content validity of CAMPIS was evaluated through quantitative and qualitative approaches. In the qualitative approach, the scale was distributed among 22 neonatal nursing specialists, neonatal subspecialists, and scale development specialists to evaluate the items in terms of grammar and wording, item allocation, and scaling.

Then the content validity of the scale was modified by measuring content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI) to ensure that the scale measures the intended construct in two separate stages. So, the 26 specialists, as highly knowledgeable about the mother of preterm infant or scale development, were asked to evaluate the items regarding necessity and relevancy. In CVR, 12 specialists evaluated the necessity of CAMPIS on a 3-point Likert scale (1 = not necessary, 2 = useful but not necessary, and 3 = necessary). CVR was calculated through the following formula: [ne – (N/2)]/(N/2), where “ne” is the number of the experts who rate the items as “essential”, and N is the total number of the items. The result was interpreted using Lawshe's content validity ratio [ 20 ].

Following the implementation of the required modifications based on the feedback provided by experts, the effectiveness of CAMPIS was further evaluated by 14 additional specialists in terms of the CVI. This evaluation was conducted using a four-point Likert scale, where a score of 1 indicated irrelevance, 2 denoted relative relevance, 3 represented relevance, and 4 signified complete relevance. The I-CVI, Kappa statistic, and S-CVI/Ave were computed to assess the content validity index at both the item-level and scale-level. A Kappa value exceeding 0.75 was deemed indicative of excellent agreement [ 19 ].

Item analysis

Before construct validity of the structure, the items were analyzed to identify the possible problems. At this step, 48 mothers of preterm infants, with the mean age of 31.88 ± 5.9 years, were selected through convenience sampling and enrolled. They were asked to identify that there were problems such as inappropriate reverse questions. Also they were asked to completed the hardcopy of CAMPIS and item-total correlations was evaluated for some items. A correlation coefficient lower than 0.32 or above 0.9 was considered as the criteria for removing the items [ 19 ].

Participants

The sample included the mothers of the preterm infants with a gestational age < 34 weeks. The criteria for entering the study consisted of the infant’s having been hospitalized in the NICU for more than two weeks, the infant’s not suffering from any major congenital anomalies, giving consent to participate in the study, and being able to use social networks such as WhatsApp. Based on the rule of thumb, that is, which considers 200 participants as an appropriate sample size [ 19 ], 401 mothers were considered for two phases at this step: 201 for the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) assessment, and 200 for the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

The participants were selected using convenience sampling through being in the hospital on the day of discharge, membership in the social groups related to following up mothers with preterm infants discharged from the NICU, and recommendations. In this step, data was collected online. For this purpose, an online questionnaire was created through the Porsline form, and its URL link ( https://survey.porsline.ir/s/d8uW4Jp ) was sent to the participants through the Telegram or WhatsApp social network applications (as the most common social networks among Iranian users).

The questionnaire used in this step included two parts. The first part was related to the infant's demographic characteristics, such as the infant's gender, and gestational age, and the mother's demographic characteristics, such as the mother's age, the infant's age, the mother's education, mothers' parity, assisted reproductive methods, the type of delivery, and previous experience in caring for infants. The second part included initial CAMPIS, with 38 items, for measuring the concept of the caring ability of mothers with preterm infants, on a five-point Likert scale (1 = never to 5 = always).

Construct validity

The construct validity of this scale was evaluated using EFA and CFA by SPSS 26 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). According to normal distribution of variables (skewness of ± 3, kurtosis of ± 7 and Mardia's coefficient less than 20) EFA was evaluated through Maximum likelihood factor analysis using Promax rotation. In addition, Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett tests were used to estimate the adequacy and the appropriateness of the sample. KMO values higher than 0.9 were interpreted as excellent [ 19 ]. In order to extract the factors according to Thompson and Daniel recommendation [ 21 ] multivariate approach was used to identify the number of factors to extract in the EFA.

Then the factors were analyzed using the method of maximum likelihood analysis, which is one of the most common methods of data reduction. At first, 5 factors had an eigenvalue greater than 1, but considering that 3 factors explained an eigenvalue greater than 1.5 and a variance greater than 5%.

To extract the factor structure, exploratory graph analysis was used. The actual values of the matrix were compared with the randomly generated matrix. The number of the components which have a higher variance in comparison with the components obtained from random data, after successive repetitions, is considered as the correct number of factors for extraction [ 22 ]. A factor loading of approximately 0.3 was considered to determine the presence of an item in a latent factor, and the items with communalities < 0.2 were excluded from EFA. The factor loading was estimated using the following formula: CV = 5.152 ÷ √ (n—2), where CV is the number of the extractable factors, and N is the sample size.

In the next step, the factor structure determined by EFA was evaluated by CFA. For this purpose, CFA was evaluated using Maximum likelihood factor analysis and the most common goodness-of-fit indices using SPSS/AMOS 26 software [ 22 ].

To discuss the fitness of the model on CFA, we can consider the various criteria for model fit indices. It has been suggested that Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) values less than 0.05 are good, and values between 0.05 and 0.08 are acceptable [ 23 ]. Therefore, the RMSEA value of 0.059 in this sample indicates an acceptable fit. The goodness of fit index (GFI) value of this sample, 0.88, is below 0.9, but the GFI is known depending on the sample size [ 24 ]. The frequency interference index (RFI) value, 0.085, is close to 0.9, which shows a relatively good fit [ 25 ]. The other fit indices, comparative fit index (CFI), incremental fit index (IFI), and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), should be over 0.9 and parsimonious normed fit index (PNFI) should be over 0.5 for a good fit [ 25 ].

Reliability

The reliability was evaluated using internal consistency, stability, and absolute reliability approaches with SPSS 26. The internal consistency was evaluated using, McDonald's omega (Ω), and average inter-item correlation (AIC). The McDonald Omega of 0.7 or above, and the AIC of 0.2 to 0.4 were considered as acceptable criteria to evaluate the internal consistency. The consistency of CAMPIS was evaluated through calculating intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) using a two-way random effects model [ 19 ]. The retest method with a time interval of 72 h (the day before discharge and 72 h after discharge) was used in 48 mothers with preterm infants. An ICC value > 0.8 is considered as the acceptable value for stability. In addition, the absolute reliability was evaluated using the standard error of measurement with the formula Standard Error of Measurement (SEM) = SD √ (1- ICC).

Finally, the responsiveness was evaluated using minimum detectable change (MDC) with the formula MDC = SEM × Z × √ 2, and minimal important change (MIC) with the following formula: MIC = SD × 0.5. If the MIC is smaller than the MDC, the scale is responsive. Besides, the interpretability was evaluated through calculating the MDC and testing the hypothesis [ 22 ].

Ethical consideration

The present study was extracted from the nursing Ph.D. thesis fund by Nursing Care Research Center (NCRC), School of Nursing and Midwifery, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. All ethical considerations of the study were approved by the ethics committee at the University of Medical Sciences (IR. IUMS. REC.1398.1407).

In qualitative step a total of 43 articles were selected in the study after reviewing 23291 extracted articles. We explored attribute of take caring ability concept. Findings showed a mother with optimal caring ability has sufficient knowledge, high skills, a sense of sufficient self-efficacy [ 17 ]. This step resulted in 69 initial items generation.

Using the findings of the literature review, comparative content analysis, and other related questionnaire items, the research teammates designed the initial items to measure the caring ability of mothers with preterm infants. An example of item generation has been presented in Table 1 . Then all the initial items (n: 104) were reviewed, and the generation of items was completed. In the selection of items, the focus was mainly on the features of the concept. The items of the pool were examined during joint meetings with the research team, and the items that were not in line with the purpose of this study were omitted according to experts’ opinions. First, repetitive descriptive items were deleted. For example, “I have access to healthcare providers and whenever I have questions, I can ask them” and “A healthcare provider answers my questions regarding the care of my child all day long 7 days a week.” This step resulted in 71 items. In the next step, the items with similar descriptions items were combined. For example, “I simply understand my child's needs.” and “When my child severely cries, I can figure out what my child wants.”

Therefore, at this step, CAMPIS was developed with 64 items, descriptions about behaviors and attitudes, on a 5-point Likert scale (always, most of the time, sometimes, rarely, never) to be psychometrically evaluated. Face, content, and construct validity, as well as reliability, were measured to evaluate the psychometric properties of CAMPIS.

In quantitative study and CAMPIS psychometric properties evaluation phase the impact score evaluation of face validity step, score of all items were above 1.5, and was considered appropriate. According to degree of mothers’ judgement all items of CAMPIS were appropriate to assessment of take caring ability. Therefore, no item was deleted.

During the process of content validity, some items were modified according to panelist feedbacks. While evaluating content validity, in the qualitative approach, 8 items were merged into one item based on the suggestion of the expert panel. Regarding number of participants for CVR were 12, the minimum acceptable CVR score was 0.56. In this step, the CVRs of 7 items were less than 0.56 and removed. In the CVI assessment, the I-CVI for all the items was in the range of 0.83–1, the modified Kappa was in the range of 0.84–1, and the total S-CVI/Ave and S-CVI/UA were 0.93 and 0.40 respectively. In content validity step according to the results, the Kappa values of 8 items were lower than 0.75, so they were removed. Therefore, 23 items were eliminated and the total number of CAMPIS was reduced from 64 to 41 items in content validity evaluation step.

In the item analysis step, the item-total correlation for 3 items was 0.32 or less, therefore were removed. The final CAMPIS with 38 items entered the factor analysis step.

In construct validity step, totally 401 mothers with a gestational age of 34 weeks or less participated in the present study. Their infants did not have any major surgical problems/anomalies, and had been hospitalized in the NICU for more than two weeks. The mean age of the mothers was 31.77 ± 6.02 years, with the minimum age of 16 and the maximum of 53 years. Out of 401 mothers, 204 (50.87%) had other children. All of them were married and lived with their spouses. The details of the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants have been shown in Table 2 .

In the construct validity phase, based on the results, the sample’s KMO and Bartlett's values were sufficient and appropriate, 0.897 and 1758.593, respectively ( P ≤ 0.001). In this step, 17 items were removed as their shared values were less than 0.2 and their factor loadings were less than 0.3. After Promax rotation, 3 factors (totally 21 items) were extracted: cognitive ability (9 items), technical ability (7 items), and psychological ability (5 items). These factors respectively explained 30.59, 9.62, and 7.28% of the total variance (47.44%) of the concept of the caring ability of mothers with preterm infants. The details of the factor analysis result have been presented in Table 3 .

Based on CFA indices, this sample has an acceptable fit to the 3 factors model and all of these indices in our study are excellent. The results of model fit indices have been given in Table 4 .

Prior to modeling modification, the goodness of fit measures for the CFA-generated 3-factor model indicated that the model fit but not optimally. To improve the factor structure model, we identified the following item content redundancies: Item 24 (If I see signs of an feeding difficulties, I know what to do) is related to Item 23 (I can recognize the signs and symptoms of shortness of breath and cyanosis), and item 8 (Given that my baby was born preterm, I am aware of the differences in growth and development with other babies.) is related to item 7 (I have enough information about my baby being preterm and its complications.).

Also, item 18 (I'm afraid my baby might be harmed.) is related to item 17 (I do not sleep well because I am worried about my baby's health.) Given the similarities of conceptual meaning, these correlated error terms indicated that these variables may share specific variances.

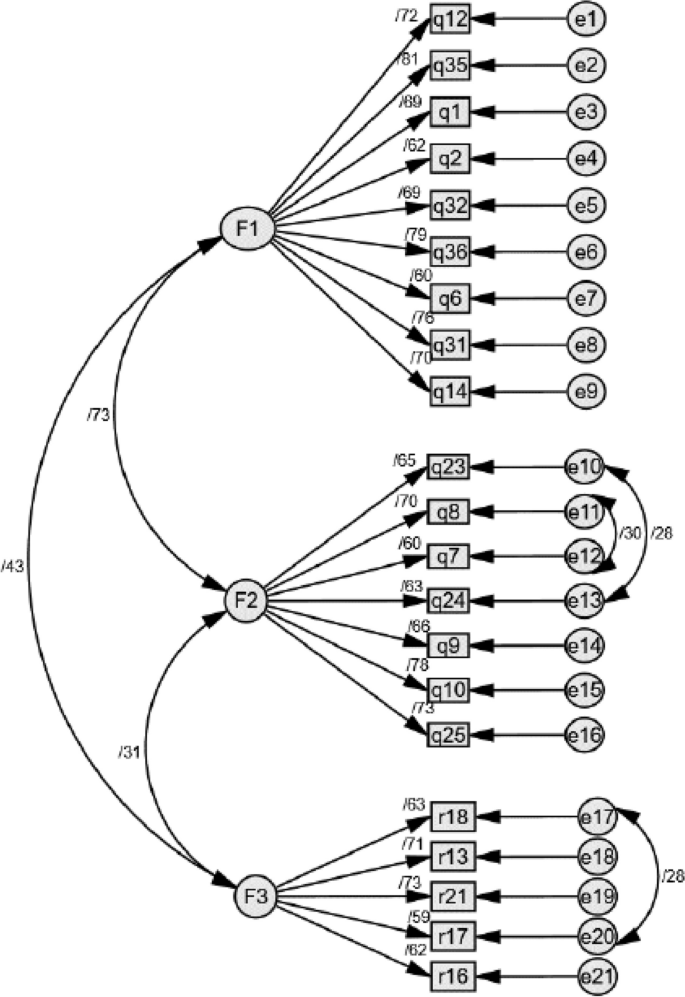

As shown in Fig. 1 , the aforementioned changes improved the goodness of fit of the model. This indicated the model of the caring ability of mothers with preterm infants fits the data (Fig. 1 ).

The results of CFA showed that a three-factor model of the care ability of the mothers with preterm infants indicated that the model fitted well. F1: Cognitive Ability; F2: Knowledge and Skills Abilities; F3: Psychological Ability

The retest method with a time interval of 72 h (the day before discharge and 72 h after discharge) was used in 48 mothers with preterm infants. An ICC value > 0.8 is considered as the acceptable value for stability. In addition, the absolute reliability was evaluated using the standard error of measurement with the formula Standard Error of Measurement (SEM) = SD √ (1- ICC). The details of the responsiveness are reported in Fig. 1 .

The results of McDonald Omega coefficient (ω = 0.90), and AIC (0.27) for the 3 factors were excellent. Based on the result, the ICC was 0.91 in the confidence interval of 0.84%-0.95%, which shows that the tool has acceptable measurement stability over time. Based on the SEM results, the absolute reliability was 3.18. This value shows that the scale scores of an individual vary ± 3.18 in repeated tests (Table 5 ). Based on the results, MDC = 8.78, MDC% = 11.79 and MIC = 0.50, this scale is responsive and interpretable.

The study’s results demonstrated that the concept of caring ability in mothers with preterm infants has three dimensions: cognitive ability, knowledge and skills abilities, and psychological ability. Therefore, CAMPIS is a valid and reliable scale to assess this concept in mothers with preterm infants. This scale includes 21 items, and three factors, cognitive, knowledge and skills, and psychological abilities, which explained 47.44% of the total variance of this concept. The CAMPIS model obtained through EFA was confirmed using CFA.

CAMPIS has three factors: "cognitive ability ", "knowledge and skills abilities" and "psychological ability". The first factor extracted from the scale was "cognitive ability". This factor includes 9 items regarding perception skills, cognitive skills, decision-making skills, movement skills, and attitude, which were extracted with the highest variance (30.59%). Cognitive abilities are the skills that a person needs to do anything from the simplest to the most complex, including perception skills, decision-making skills, movement skills, language skills, and social skills [ 26 ]. Cognitive abilities are the link between behavior and the brain structure, which include a wide range of abilities including planning, paying attention, problem solving, performing tasks simultaneously, and cognitive flexibility [ 27 ]. In this scale, cognitive ability was defined as the ability of a mother with a preterm baby to use skills which help her process information, think, reason, and solve problems faster and more efficiently. By developing cognitive skills, a person can go through the process of reasoning, decision making, and taking action. In this way, she can make sure that she can perceive the new situation, and perform her role effectively. The findings of a study conducted in 2004 showed that the mother’s possessing the desired attitudinal-cognitive ability had a significant impact on the infant’s health [ 28 ].

The second factor extracted from the scale was "technical ability". This factor includes 7 items regarding care knowledge and skills, as well as the ability to apply them; it was extracted with an acceptable variance (9.62%). In the science of care, knowledge is defined as the caregiver's awareness of the care recipient’s needs, strengths, and weaknesses as a unique member [ 10 ]. Moreover, in a study conducted by Galvin et al. in 2017, which was conducted with the aim of investigating the analytical features of the concept of readiness for discharge from the hospital, having sufficient knowledge and skills was mentioned as one of the characteristics of readiness for discharge [ 29 ]. In this scale, knowledge-skill ability is defined as that the mother’s awareness of the tasks that she must know how to perform in order to provide effective, efficient, and reliable care for her infant. The mothers of preterm infants often have poor knowledge regarding infant care after discharge [ 30 ], while the main factor which shows the mother's ability to provide care for the infant is having sufficient knowledge and skills. The mother should know what, how, why, and when to provide care for her infant [ 30 ].

The lived experience of the parents with preterm infants showed that in most cases, they are not prepared for the infant’s birth. The birth of a preterm infant puts them in a special situation which requires new care skills [ 31 ]. The parents need to acquire these skills that are a prelude to the discharge and transfer of the infant to home [ 32 ]. Providing quality care for complex disorders requires specialized caregiving knowledge and skills. When there is a deficiency in these areas, negative psychological impact on the parents and their relationship with their infant can ensue [ 33 ]. Studies have shown that having sufficient preparation for discharge and transitional care can help the families of preterm infants with a successful transition from the hospital to the family, reducing the rehospitalization rates [ 34 ]. To this end, health care professionals should provide the parents with useful information regarding illness management, strengthen their relationships with the hospital staff, encourage sharing experiences and emotions, and perform home visits [ 35 ]. The empowerment method should be appropriate to the caregiver's conditions. It should predict the caregiver's psychological condition as well as his/her emotional and behavioral responses. It should be used to train and support the caregiver in decision-making and managing the caregiving situation, considering his/her experiences, social status, cultural level, and beliefs [ 36 ].

The third factor extracted from the scale was "psychological ability". This factor includes 5 items regarding the psychological characteristics of the mothers taking care of preterm infants, with an acceptable variance (7.28%). An individual who is aware of his/her abilities and need for self-dependence, to manage care after discharge, has good psychological ability [ 29 ]. It is necessary to achieve psychological ability for an individual to deal with post-discharge challenges and have control over the situation [ 37 ]. In the present study, the mother's psychological ability is defined as her possessing the psychological characteristics and mental makeup to feel ready to continue care provision after discharge from the NICU, and to be able to fulfill her caring role successfully. During a traumatic event such as an infant's hospitalization in the NICU, the mothers try to improve their psychological ability [ 38 ].

The most mothers of preterm infants are not psychologically prepared for delivery and motherhood [ 39 ]. Preterm birth is considered a sudden and unpredictable event, which is accompanied by a feeling of shock and helplessness. The mothers of preterm infants often describe these conditions using terms such as falling to the bottom of a deep well, and being stuck in a whirlwind and storm happening around them; they admit they do not have enough control over what is happening, and lack the ability to take care of their infants [ 40 ]. Hospitalization in the NICU and mother-infant separation cause a feeling of inadequacy in the mother [ 41 ], which can subsequently affect her psychological ability. This maybe cause using different methods to deal with it. Using ineffective coping methods regarding changes in lifestyle and playing one’s role impacts on mother's caretaking tasks. If the use of ineffective coping methods is not recognized at the right time, and if appropriate measures are not taken, then the nursing diagnosis of coping disability disorder will be imminent [ 42 ]. Improved mental health and sufficient psychological ability are an important prerequisite for behavior change, which acts as a link between awareness and action. It can have a moderating role in empowering individuals, leading to positive thoughts, greater self-esteem and goals, more positive emotions and desirable behaviors [ 43 ]. Therefore, it is very important to measure the psychological ability of the mother in order for her to acquire the ability to provide quality care for the preterm infant.

Being aware of the caring ability of their mothers, as the main care givers, and designing an intervention to improve their caring ability can prevent negative side effects and help to improve the quality of care. The present study was conducted with the aim of designing and psychometric evaluation of the tool for assessing caring ability in mothers with preterm infants. Since one of the main goals of psychometric evaluation and factor analysis is to maximizing the explained variance by the model, in this research, the variance was 47.44%. Among the scales designed to measure caring ability, regardless of factor analysis extraction method, only one scale, the caring ability scale of the caregivers of cancer patients (67.7%), explains variance more than CAMPIS does [ 11 ].

In addition, this CAMPIS had very good internal consistency based on the results of Cronbach's alpha, AIC, and McDonald omega. It should be noted that one of the advantages of this scale is having strong stability based on the ICC value. Another advantage of this study was the assessment of measurement error, responsiveness, and interpretation of the CAMPIS. The results showed that the CAMPIS has the minimum amount of SEM, responsiveness, and interpretability. SEM shows the accuracy of the measurement for each individual, and it is important that this value be small. Responsiveness refers to the ability of a scale to reflect changes in an individual's position over a period. Finally, interpretability refers to the scale's ability to show the significance of changes. These characteristics are an important and necessary part of consensus-based standards for the selection of health measurement tools, which have not been reported in the previous studies on the psychometric characteristics of caring ability.

CAMPIS measures the caring ability of the mother of a preterm infant in the three factors namely ‘Cognitive Ability’ (items: 1–9), ‘knowledge and skills abilities' (items: 10–16), and ‘Psychological Ability’ (items: 17–21). The answer to the items is based on a five-point Likert scale (always (5), most of the time (4), sometimes (3), rarely (2), never (1)). Scoring of items 17,18,19,20 and 21 is reverse so (always (1), most of the time (2), sometimes (3), rarely (4), never (5)). To have an overall score: Sum cognitive ability + sum knowledge and skills abilities + sum psychological ability = Total score. The best way is to calculate the average score for every scale, and compare the results with the average score. In our studies we set the average score for cognitive ability from 9–45, knowledge and skills abilities 7–35, psychological ability 5–25, and overall score 21–105 (Additional file 1 : Appendix A). CAMPIS, is a useful scale for professional caregivers and researchers, thanks to its brief items, good variance, reliability, as well as exclusively belonging to this group.

The findings of this study demonstrated that CAMPIS is a reliable and valid scale with 21 items, which includes the 3 dimensions of attitudinal-cognitive ability, knowledge-skill ability, and psychological ability for measuring the concept of tenacity in family caregivers. Although the exclusiveness of CAMPIS to evaluate the caring ability of mothers with preterm infants is one of the points of strengths in this study, but considering that the samples were selected from the population of Iranian mothers with preterm infants with a gestational age of 34 weeks or less. It should be used with caution in mothers with preterm infants with a gestational age over 34 weeks. Therefore, one of the important limitations was the concern about the generalizability of the findings.

Limitations and strength

In the construct validity step, data collection was done online. Although the use of online questionnaires, especially during the period of social restrictions due to COVID-19 pandemic, has many advantages, such as the possibility of eliminating the missing data, speeding up the data collection process, and the possibility of collecting data from other provinces and counties. There are also some limitations like self-selection bias, and the lack of interaction with the participants. Furthermore, some qualified mothers were excluded from the study due to illiteracy, the lack of internet access, and the inability to use the phone/laptop to access social networks.

During the item generation step, we considered the different directions of items, but during data reduction, opposite directions were removed. Finally, all items of each factor of CAMPIS have oriented in the same direction, and it is imaginable to create a possibility for response tendency.

One of the problems of self-report scales is that they are subject to the respondent's interpretation of the items, which may not be what the scale designer has intended. In order to reduce this potential problem, continuous testing and modification of the scale has been done. Since ability is a personal matter, the participants were asked not to reveal their names, cities, and the name of the hospitals where their infants were hospitalized. This study has points of strength. One of them is the evaluation of SEM, ICC, responsiveness, and interpretability as important and required items of the COSMIN checklist, which had not been reported previously regarding caring ability scales, but were evaluated in this study.

Availability of data and materials

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Request access to other supplementary material can be directed to the first or corresponding author.

Abbreviations

Caring Ability of Mother with Preterm Infant Scale

Exploratory factor analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

World Health Organization

Content validity ratio

Content validity index

Item-level content validity index,

Scale-level content validity index average

Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin

Average Inter-Item Correlation

Intraclass correlation coefficients

Minimum Detectable Change Analysis

Minimal Important Change

Comparative Fit Index

Incremental Fit Index

Frequency Interference Index

Parsimonious Normed Fit Index

Tucker-Lewis Index

Goodness of Fit Index

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation

Confidence Interval

Standard Error of Measurement

Cao Y, Jiang S, Sun J, Hei M, Wang L, Zhang H, et al. Assessment of neonatal intensive care unit practices, morbidity, and mortality among very preterm infants in China. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(8):e2118904-e.

Article Google Scholar

Chawanpaiboon S, Vogel JP, Moller A-B, Lumbiganon P, Petzold M, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(1):e37–46.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Lasiuk GC, Comeau T, Newburn-Cook C. Unexpected: an interpretive description of parental traumas’ associated with preterm birth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13(1):1–10.

Google Scholar

Howson C, Merialdi M, Lawn J, Requejo J, Say L. March of dimes white paper on preterm birth: the global and regional toll. March of dimes foundation. 2009:13.

Gerstein ED, Njoroge WF, Paul RA, Smyser CD, Rogers CE. Maternal depression and stress in the neonatal intensive care unit: associations with mother− child interactions at age 5 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58(3):350-8. e2.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Fowler N, Vo PT, Sisk CL, Klump KL. Stress as a potential moderator of ovarian hormone influences on binge eating in women. F1000Research. 2019;8.

Stern DN, Bruschweiler-Stern N. The birth of a mother: How the motherhood experience changes you forever: Basic Books; 1998.

Slade A, Cohen LJ, Sadler LS, Miller M. The psychology and psychopathology of pregnancy. Handbook of Infant Mental Health. 2009;3:22–39.

Spinelli M, Frigerio A, Montali L, Fasolo M, Spada MS, Mangili G. ‘I still have difficulties feeling like a mother’: the transition to motherhood of preterm infants mothers. Psychol Health. 2016;31(2):184–204.

Nkongho NO. The caring ability inventory. Measure Nurs Outcomes. 2003;3:184–98.

Nemati S, Rassouli M, Ilkhani M, Baghestani AR, Nemati M. Development and validation of ‘caring ability of family caregivers of patients with cancer scale (CAFCPCS).’ Scand J Caring Sci. 2020;34(4):899–908.

Koren PE, DeChillo N, Friesen BJ. Measuring empowerment in families whose children have emotional disabilities: a brief questionnaire. Rehabil Psychol. 1992;37(4):305.

Samra HA, McGrath JM, Fischer S, Schumacher B, Dutcher J, Hansen J. The NICU parent risk evaluation and engagement model and instrument (PREEMI) for neonates in intensive care units. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2015;44(1):114–26.

Smith V, Young S, Pursley D, McCormick M, Zupancic J. Are families prepared for discharge from the NICU? J Perinatol. 2009;29(9):623–9.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Barnes CR, Adamson-Macedo EN. Perceived maternal parenting self-efficacy (PMP S-E) tool: development and validation with mothers of hospitalized preterm neonates. J Adv Nurs. 2007;60(5):550–60.

Prasopkittikun T, Tilokskulchai F, Sinsuksai N, Sitthimongkol Y. Self-efficacy in infant care scale: development and psychometric testing. Nurs Health Sci. 2006;8(1):44–50.

Tajalli S, Ebadi A, Parvizy S, Kenner C. Maternal caring ability with the preterm infant: a Rogerian concept analysis. Nurs Forum. 2022;57(5):920–31.

Lindgren B-M, Lundman B, Graneheim UH. Abstraction and interpretation during the qualitative content analysis process. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;108:103632.

Sharif Nia H, Zareiyan A, Ebadi A. Test Development Process in Health Sciences; Designing and Psychometric properties. Tehran: Jame-e-negar; 2022.

Lawshe CH. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers Psychol. 1975;28(4):563–75.

Thompson B, Daniel LG. Factor analytic evidence for the construct validity of scores: A historical overview and some guidelines. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Sage CA; 1996. p. 197–208.

Pahlevan Sharif S, Sharif NH. Factor analysis and structural equation modeling with SPSS and AMOS. Tehran: Jame-e-Negar; 2020.

Fabrigar L, Wegener Dt, MacCullum R. Strahan, e. J. Evaluating the use of factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Methods. 1999;4:272-99.

Mulaik SA, James LR, Van Alstine J, Bennett N, Lind S, Stilwell CD. Evaluation of goodness-of-fit indices for structural equation models. Psychol Bull. 1989;105(3):430.

Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1990;107(2):238.

Benjamin DJ, Brown SA, Shapiro JM. Who is ‘behavioral’? Cognitive ability and anomalous preferences. J Eur Econ Assoc. 2013;11(6):1231–55.

Ones DS, Dilchert S, Viswesvaran C, Salgado JF. Cognitive abilities: Taylor & Francis Group; 2010. 255–75 p.

Rubalcava LN, Teruel GM. The role of maternal cognitive ability on child health. Econ Hum Biol. 2004;2(3):439–55.

Galvin EC, Wills T, Coffey A. Readiness for hospital discharge: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73(11):2547–57.

Hochreiter D, Kuruvilla D, Grossman M, Silberg J, Rodriguez A, Lary L, et al. Improving guidance and maternal knowledge retention after well-newborn unit discharge. Hosp Pediatr. 2022;12(2):148–56.

Amorim M, Alves E, Kelly-Irving M, Silva S. Needs of parents of very preterm infants in Neonatal Intensive Care Units: a mixed methods study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2019;54:88–95.

Jing L, Bethancourt C-N, McDonagh T. Assessing infant and maternal readiness for newborn discharge. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2017;29(5):598–605.

Hellesø R, Eines J, Fagermoen MS. The significance of informal caregivers in information management from the perspective of heart failure patients. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(3–4):495–503.

Boykova M, Kenner C. Transition from hospital to home for parents of preterm infants. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2012;26(1):81–7.

Lundqvist P, Weis J, Sivberg B. Parents’ journey caring for a preterm infant until discharge from hospital-based neonatal home care—A challenging process to cope with. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(15–16):2966–78.

Hamilton DL. Personality attributes associated with extreme response style. Psychol Bull. 1968;69(3):192.

Carroll Á, Dowling M. Discharge planning: communication, education and patient participation. Br J Nurs. 2007;16(14):882–6.

Aftyka A, Rozalska-Walaszek I, Rosa W, Rybojad B, Karakuła-Juchnowicz H. Post-traumatic growth in parents after infants’ neonatal intensive care unit hospitalisation. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(5–6):727–34.

Rossman B, Greene MM, Meier PP. The role of peer support in the development of maternal identity for “NICU moms”. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2015;44(1):3–16.

O’Donovan A, Nixon E. “Weathering the storm:” Mothers’ and fathers’ experiences of parenting a preterm infant. Infant Ment Health J. 2019;40(4):573–87.

Kestler-Peleg M, Lavenda O, Stenger V, Bendett H, Alhalel-Lederman S, Maayan-Metzger A, et al. Maternal self-efficacy mediates the association between spousal support and stress among mothers of NICU hospitalized preterm babies. Early Human Dev. 2020;146:105077.

Ackley BJ, Ladwig GB, Makic MBF, Martinez-Kratz M, Zanotti M. Nursing Diagnosis Handbook, Revised Reprint with 2021–2023 NANDA-I® Updates-E-Book: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2021.

Karademas EC. Self-efficacy, social support and well-being: The mediating role of optimism. Personality Individ Differ. 2006;40(6):1281–90.

Download references

Acknowledgements

This article extracted from Ph.D. thesis of the first author, which was financially supported by the Nursing and Midwifery Care Research Center in ……… University of Medical Sciences (NCRC-1407). The authors would like to extend their sincere thanks to mothers, healthcare providers and other participants who shared their experiences with us.

Clinical trial registration

Not applicable.

Preprint disclosure

Saleheh Tajalli, Abbas Ebadi and Carole Kenner have no funding to disclose. Soroor Parvizy is supported by a grant from the vice chancellor of research from Nursing and Midwifery Care Research Center in Iran University of Medical Sciences under Grant number [1398–12-27–1407] CRediT.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Nursing and Midwifery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Saleheh Tajalli

Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Life Style Institute, Nursing Faculty, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Abbas Ebadi

Nursing and Midwifery Care Research Center, Pediatric Nursing Department, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Soroor Parvizy

Center for Educational Research in Medical Sciences (CERMS), Department of Medical Education, School of Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

School of Nursing and Health Sciences, The College of New Jersey, Ewing, NJ, USA

Carole Kenner

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

S.T: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. S.P: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Validation, Funding acquisition. A.E: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing review & editing, Resources. C.K: Writing -review & editing, Resources. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Abbas Ebadi or Soroor Parvizy .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent to participate and publication.

All parents of neonate in the study were informed of the study objectives and signed a written informed consent form.

Consent for publication

Consent to publish was obtained from the study participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: appendix a..

The last version of "Caring Ability of Mother with Preterm Infant Scale" (CAMPIS).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Tajalli, S., Ebadi, A., Parvizy, S. et al. Development and psychometric evaluation of "Caring Ability of Mother with Preterm Infant Scale" (CAMPIS): a sequential exploratory mixed-method study. BMC Nurs 23 , 297 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-01960-7

Download citation

Received : 24 November 2023

Accepted : 22 April 2024

Published : 29 April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-01960-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Caring ability

- Maternal caregiving

- Preterm infant

- Psychometric

BMC Nursing

ISSN: 1472-6955

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 06 March 2024

Innovation dynamics within the entrepreneurial ecosystem: a content analysis-based literature review

- Rishi Kant Kumar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5681-0203 1 ,

- Srinivas Subbarao Pasumarti 2 ,

- Ronnie Joshe Figueiredo 3 ,

- Rana Singh 1 ,

- Sachi Rana 4 ,

- Kumod Kumar 1 &

- Prashant Kumar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9160-5811 5

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 366 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1781 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Business and management

Entrepreneurial ecosystems (EEs) delineate concepts from varied streams of literature originating from multiple stakeholders and are diagnosed by different levels of analysis. Taking up a sample of 392 articles, this study examines how innovation fosters the emergence of self-operative and self-corrective entrepreneurial ecosystems in the wake of automatic market disruptions. It also finds that measures lending vitality and sustainability to economic systems across the world through a mediating role played by governments, along with synergies exhibited by academia and “visionpreneurs” at large, give rise to aspiring entrepreneurs. The study also aligns past practices with trending technologies to enrich job markets and strengthen entrepreneurial networks through spillover and speciation. The research offers valuable insights into entrepreneurial ecosystems’ practical policy implications and self-regulating mechanisms, and it suggests that governments overseeing these entrepreneurial ecosystems should identify and nurture the existing strengths within them. Additionally, entrepreneurial ecosystems can benefit from government support through subsidies and incentives to encourage growth. In collaboration with university research, specialized incubation centers can play a pivotal role in creating new infrastructures that foster current and future entrepreneurial development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Changing entrepreneurial attitudes for mitigating the global pandemic’s social drama

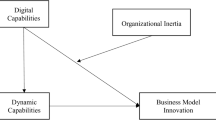

The impact of digital capabilities and dynamic capabilities on business model innovation: the moderating effect of organizational inertia

Digital transformation, entrepreneurship, and disruptive innovation: evidence of corporate digitalization in China from 2010 to 2021

Introduction.

Innovation provides a gateway to products/services in varied market dynamism by transcending time horizons. Innovations work on the back and call of automatic disruptions that happen in markets through the mediating role of governments, institutions, and academicians, leading to “self-operative” and “self-corrective ecosystems.” Most of the time, innovative processes are self-corrective and operate without much effort. As innovations in products keep evolving, they rekindle customers’ interest and increase the prospects of products for better sales and a long-life cycle (for example, entrepreneurs may offer new features or new looks to older products). To undertake this sort of initiative, commercial freedoms must be guaranteed, which can be used to create, deploy, and protect intangible assets (Teece, 2007 ; Sprinkle, 2003 ). Thus, innovations together with entrepreneurial networks or ecosystems provide dynamic capabilities to the economy by imparting continuity. In that process, entrepreneurs, through their better learning skills and novel methods, create opportunities in changing markets (Garnsey and Leong, 2008 ; Garnsey et al., 2008 ; Kantarelis, 2009 ; Levinson, 2010 ; Biggs et al., 2010 ), as markets are always fueled by disruptions in entrepreneurial ventures, and old products must be replaced by newer ones.

Further, synergy between entrepreneurial ecosystems and research plays a pivotal role in fostering disruptive innovations within contemporary markets. This collaboration, exemplified by the establishment of “spin-off companies” from academic research, is instrumental in guiding aspiring talent and cultivating growth in local economies. However, despite this symbiosis, a notable gap exists in knowledge spillovers between universities and their surrounding entrepreneurial and innovation ecosystems. To address this, collaborative and interactive research is recommended, as proposed by Mehta et al. ( 2016 ). Such initiatives not only facilitate self-operative and self-corrective entrepreneurial ecosystems but also contribute to knowledge spillovers that fuel product development and speciation. The interconnected processes of institutionalizing methods, policy entrepreneurship, and knowledge spillovers underscore the intricate relationship between academia, institutional research, and market dynamics, emphasizing the need for cohesive strategies to bridge existing gaps and maximizing the impact of disruptive tendencies in entrepreneurship. This mechanism can receive a boost with the assistance of sustainable innovation of society through “social entrepreneurship education (SEE) programs” (Kim et al., 2020 ), which can be designed and operated to cultivate social entrepreneurial abilities and contribute to the development of innovation hubs for entrepreneurial ecosystems (EEs). For example, a study by Igwe et al. ( 2020 ) focused on frugal innovations and informal entrepreneurship, which could lead to the creation of fresh, innovative tendencies in informal sectors of different nations.

So, looking forward, the relevance for the development of entrepreneurial networks (Teece, 2007 ), where innovation can accentuate the need for the intersection of researchers, entrepreneurship, and regional economic development while holding entrepreneurship as a key mechanism. Although there has been much innovative research done in recent years using a systematic literature review approach, it was observed that existing literature typically lacked the required comprehensive theoretical foundations; more work can contribute to the development of suitable theoretical methodologies for practical results in economic development. For example, past literature is focused on intervention of innovation with digital entrepreneurship (Satalkina and Steiner, 2020 ), social entrepreneurship (Fauzi et al., 2022 ). In a similar way, Montes-Martínez and Ramírez-Montoya ( 2022 ) oriented their research towards finding the relationship between educational and social entrepreneurship innovations using a systematic mapping technique and suggested a potential research gap in this area by collating the number of articles published and geographical contributions. Further, the literature also talked about sustainable entrepreneurship (Thananusak, 2019 ), technological innovation and entrepreneurship in management science (Shane and Ulrich, 2004 ), or the role of open innovation in entrepreneurship (Portuguez-Castro, 2023 ).

Conversely, most of these studies deliberated on the genesis, development, and operation of innovative entrepreneurial ecosystems and subsidiary literature contributing to their existence and growth, then those for laying down foundations for newer tendencies the world is witnessing and vying to enable and sustain them during the times of “Contaminant Economic Trends” (abrupt economic disruptions due to the advent of some natural, environmental, or manmade phenomenon such as COVID-19). It is essential to combine and progress research in several important areas to fill the current gaps in the literature on innovation and entrepreneurship. First, a thorough investigation of information effects is necessary for the present connection between innovation and entrepreneurial ecosystems, especially through subsidiaries businesses. Mehta et al. ( 2016 ) support collaborative research, but more research is required to understand the mechanisms and obstacles preventing knowledge transfer from institutions to entrepreneurial ecosystems. This research aims to examine the following research questions:

What are the key thematic progressions in innovation research within the field of entrepreneurial ecosystems?

What conceptual models can be recommended based on the existing literature to guide and inform future research endeavors at the intersection of innovation and entrepreneurial ecosystems?

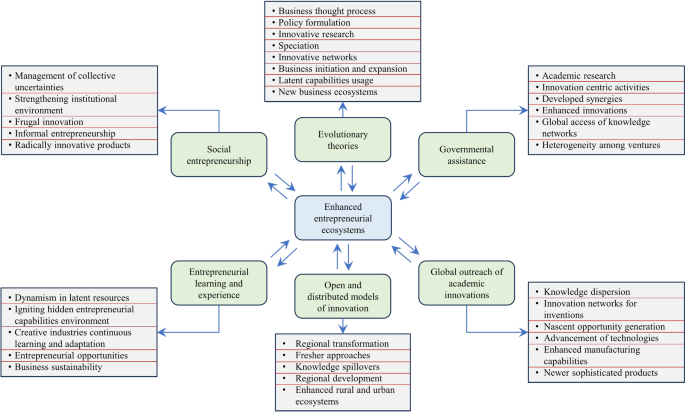

To examine the research questions, we applied the text mining approach of the content analysis method on the articles collected on the keywords related to innovation and entrepreneurship for a selected period. This study also aims to fill this gap by designing a model of EE offering multidimensional insights into recent developments in the field of entrepreneurial ecosystems. This study contributes theoretically by synthesizing insights from a systematic literature review to construct a comprehensive model elucidating the intricate dynamics influencing entrepreneurial ecosystems. Identified decisive components—namely, “Evolutionary Theories,” “Governmental Assistance,” “Global Outreach of Academic Innovations,” “Open and Distributed Models of Innovation,” “Entrepreneurial Learning Experience,” and “Social Entrepreneurship”—provide a nuanced understanding of factors shaping enhanced entrepreneurial landscapes. The structured model unveils the synergies underpinning ecosystem development across diverse nations and economies amid economic uncertainties. Moreover, the study posits that government policies, such as subsidized infrastructural support, play a pivotal role in fostering entrepreneurial growth, thereby contributing novel perspectives to the scholarly discourse on entrepreneurial ecosystem evolution.

From this point forward, the paper progresses as follows: Section “Theoretical background and analysis” explains the meaning of innovation and its place in entrepreneurship development and entrepreneurial ecosystem networks; Section “Methodology” reviews prior literature on innovation in the entrepreneurship context; Section “Results” discusses the methodology adopted for the present study and delves into the methods of data collection and analysis for present research; Section “Discussion” discusses the results and analysis done in the present study; Section “Implications, Limitations, and Future Trends” delineates the theoretical implications of the present research and proposes a conceptual model for better innovation in entrepreneurship; and Section “Conclusion” takes up the conclusion part of the study.

Theoretical background and analysis

Past research has mainly focused on developing entrepreneurial ecosystems and their genesis. They hardly focused on what is mainly lacking in the growth process of these ecosystems and why academic knowledge fully fails to translate into entrepreneurial achievements. Moreover, past studies have explored and delineated the extant ecosystems with their peculiarities without looking deep down into the self-operative and self-corrective mechanisms of entrepreneurial ecosystems, which have their own strengths that make them resilient to economic turbulences. The present study highlights this mechanism and forwards a model that explains the process of enhanced ecosystems.

What is innovation?

As per the Schumpeterian view, the practical implementation of ideas for developing new goods and services is innovation (Mehmood et al., 2019 ). ISO TC 279, in the standard of ISO 56000:2020, states that innovation is “a new or changed entity realizing or redistributing value” (ISO, 2020). Definitions of innovations focus on newness, improvement, and the spread of ideas or technologies, products, processes, services, technologies, and artworks (Lijster, 2018 ). Business models that are brought forward by innovators to the market, governments (Bhasin, 2012 ), and society are certain modes through which innovation takes place.

Innovation and entrepreneurship

The advancement of entrepreneurial innovation has necessitated an increased demand for policy interventions that encourage and complement entrepreneurial ecosystems. These interventions are crucial for managing and containing emerging disruptions by introducing effective strategies. The goal is to harness these disruptions for the development of newer and improved entrepreneurial ecosystems, ultimately bringing greater benefits to entrepreneurial ventures. By employing business strategies in indigenous markets, entrepreneurs can carve out niches to meet existing demands and expand into international markets (Sprinkle, 2003 ).

This approach not only enhances enterprise performance in an open economy but also stimulates rapid innovation and disperses dynamic capacities across enterprises, entities, and institutions. According to Teece ( 2007 ), it establishes micro-foundations for entrepreneurial ecosystems, contributing to the formation of innovative networks that support emerging industries (Garnsey and Leong, 2008 ). Additionally, it generates conceptual dimensions by developing complementarities that assist in the adoption of compatible applications (Garnsey et al., 2008 ).

For instance, recent literature on entrepreneurial practices during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and post-pandemic business activities catalyzed by the digital revolution highlights the acceleratory role of digitization in expanding the business world. This digital transformation has led to the development of novel social innovations, transforming entrepreneurial practices and liberating the workforce from being “cabin cooped in individuals” to “flexible timers.” These social disruptors have also prompted the exploration of groundbreaking approaches for assessing nuances that emphasize sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems. Lastly, we present the core concepts related to these domains in Table 1 .

Methodology

Many researchers have applied different methodologies for literature review, such as theory-based review (Debellis et al., 2021 ); framework-based systematic review (Rosado-Serrano et al., 2018 ); theme-based structured review (Pansari and Kumar, 2017 ); techno-commercial literature review (Chatterjee et al., 2018 ; Kumar et al., 2020 ); and literature review based on text mining (Kumar et al., 2019 ). As for article selection, researchers indicate selecting a database such as Scopus or Web of Science (Kumar et al., 2023 ; Donthu et al., 2021 ), with which researchers get a better grasp of a specific domain of research (Alvesson & Sandberg, 2020 ) and set the stage for future research (Elsbach & Knippenberg, 2020 ). By looking at our research questions, we have employed content analysis with a text mining approach in this study, which presents thematic analysis and helps present contextual analysis.

Database preparation

The present study seeks to explore the themes underlying the domain of innovation in entrepreneurial ecosystems. Considering the methodology followed by Akter and Wamba ( 2016 ), we searched keywords such as “business entrepreneurship,” “entrepreneurial ecosystem,” and “entrepreneurial networks” on Scopus in the abstract, title, and keywords fields to search relevant documents. There were 2136 articles matching the keywords in January 2023; following this, a search for “innovation” yielded 772 documents. The final filter was performed to select articles and reviews only, which left us with a batch of 392 documents belonging to different subject areas like business management (34.6%), followed by Social Sciences (17.0%), Economics (14.4%), Engineering (7.7%), Environmental Sciences (6.4%), Computer Sciences (3.1%), Decision Sciences (3.1%), Energy (2.7%), Psychology (1.9%), Biochemistry (1.7%), and others (7.4%). All 392 articles’ abstracts were subjected to content analysis (text mining) after selecting the timeframes outlining the extracted themes to showcase the changes in the research.

Different approaches exist for selecting time duration: while Leone et al. ( 2012 ) proposed three years, Kumar et al. ( 2019 ) suggested five years for getting ideal time durations. In this study, the initial timeframe covered research for 13 years (2003–15) as in these years there were very few publications. Afterward, two sets of two-year durations of 2016–17 and 2018–19 were included, followed by three sets of single-year durations (2020, 2021, and 2022). We initially categorized articles by year but found that there were relatively few articles published in the earlier years, with a significant increase after 2010. Consequently, selecting either a 3-year or 5-year timeframe would have resulted in sample size variation by including the number of articles in each timeframe. To address this, we segmented the articles into eight periods, each containing over 40 articles in each timeframe. The year selection was done to reduce the redundancy found during the content analysis of the abstracts.

Analysis method

Looking toward our first research question of key thematic progressions in the selected domain, we applied the content analysis method to the abstract of 392 articles. In the content analysis approach, text mining (Kumar et al., 2019 , Tiwary et al., 2021 ) is a natural language processing (NLP) technique used to explore valuable insights and uncover relationships from unstructured text data. Text mining provides various benefits due to its feature of processing and analyzing large volumes of data quickly, which allows researchers to find trends and patterns effectively, which could be difficult using human approaches. Furthermore, text mining makes it possible to generate useful numerical indices that support the quantification and methodical examination of word clusters, thereby improving the accuracy and effectiveness of content analysis techniques. Text mining is being used in academic research to speed up the analytical process and improve the quality and scope of insights obtained from unstructured textual material (Karami et al., 2020 ; Gurcan and Cagiltay, 2023 ). We applied text mining to capture the themes that emerged from the articles and to create meaningful numeric indices to analyze word clusters (Feldman & Sanger, 2007 ). As for text mining, we used the widely accepted bibliometric tool “VOSViewer” (Van Eck and Waltman, 2010 ) to analyze the abstract by creating a term co-occurrence map.

Following our RQ1 of exploring maturity and themes of innovations in entrepreneurial ecosystems, we first analyzed all the articles published annually as per maturity and research exploration. We present the results from each year group below separately:

Theme that emerged during the year 2003–2015

Conceptual visualization.

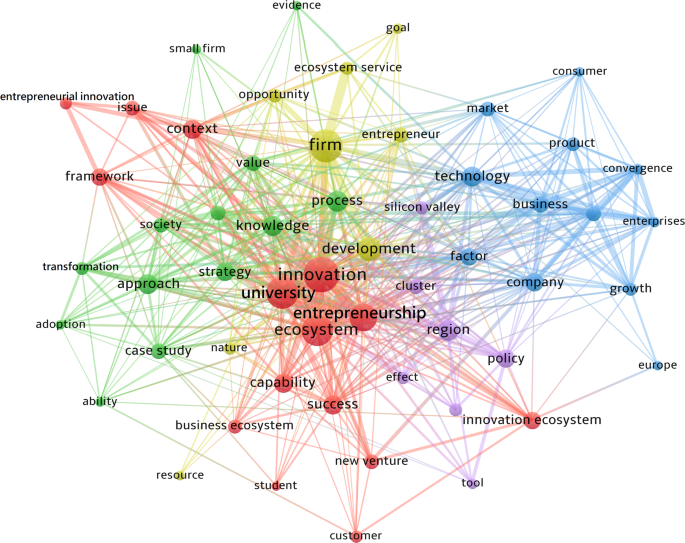

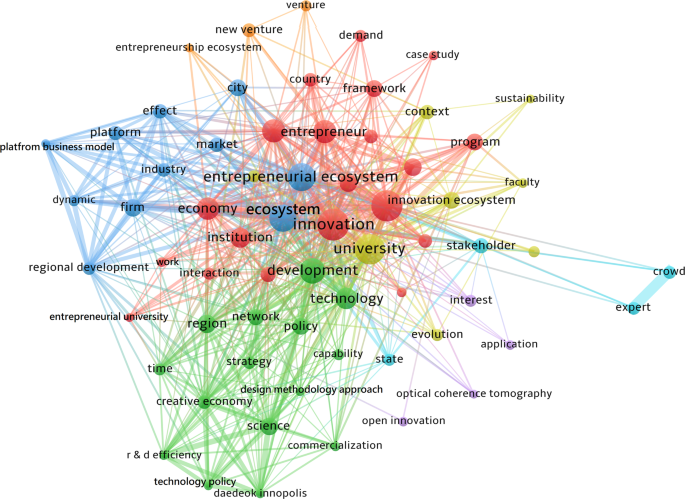

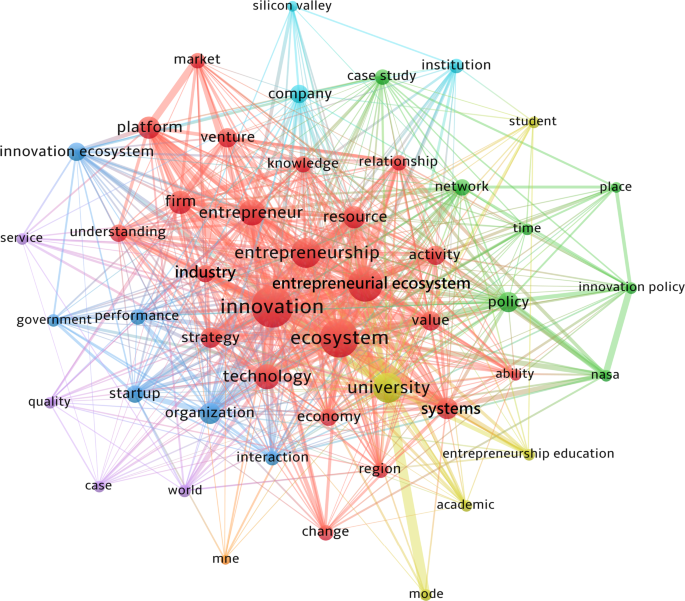

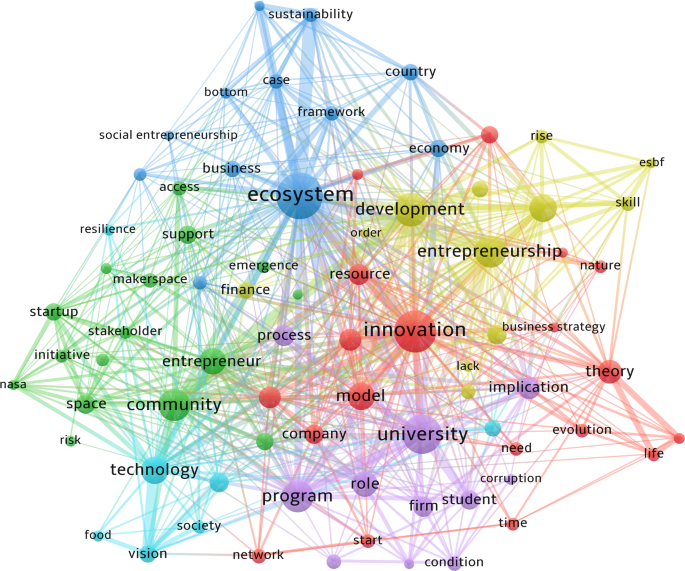

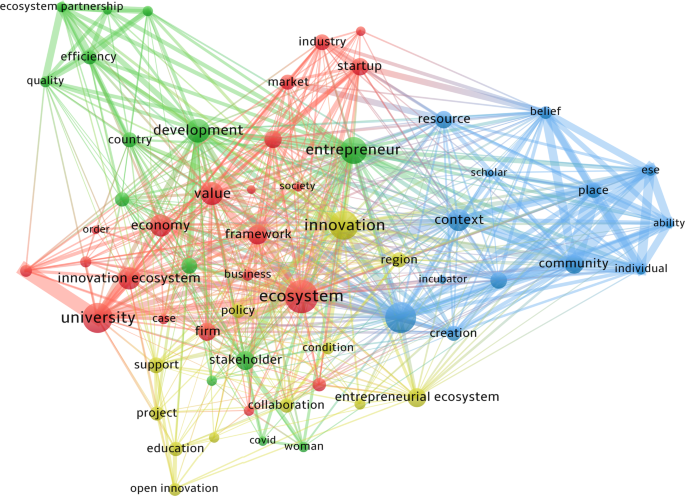

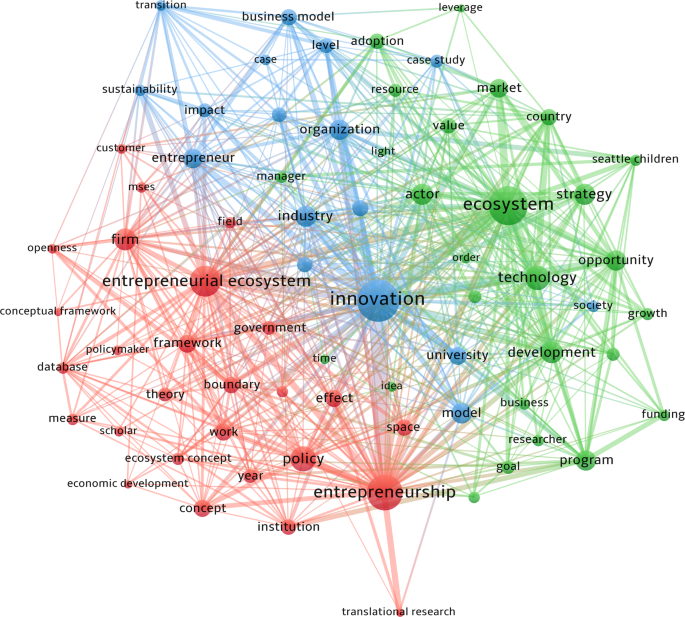

During this period, the focus was on exploring themes that were categorized under specific clusters (see Fig. 1 ), “business ecosystem, capability, customer, development, ecosystem service, entrepreneur, Europe, firm, goal, innovation ecosystem, new venture, opportunity, resource, student, success.” These word clusters indicate entrepreneurial symphony , especially capturing nurturing success in the business ecosystem . Further, a cluster containing words like “adoption, case study, culture, ecosystem, emergence, knowledge, phenomenon, small firm, society, strategy, transformation, value” indicates its connection with Cultural Catalysts , unveiling small firm transformation through ecosystem adoption . The third theme under these years contains words like “entrepreneurial innovation, entrepreneurship framework, government, innovation, issue, policy, region, Silicon Valley, university,” indicating its connection with Elevate by Innovation by crafting a robust entrepreneurship framework for regional growth and navigating government policies . The last theme under these years contains words such as “business, case, company, consumer, convergence, enterprises, factor, growth, medium, product, technology” grouping theme under TechConverge Enterprises , which navigates business growth through consumer-centric mediums and product innovation .

Theme of study during the years 2003–2015.