OCR homepage

Administration

- Active Results

- Interchange

- Submit for Assessment

- Teach Cambridge

- ExamBuilder

- Online Support Centre

Main navigation

As and a level religious studies - h173, h573.

If you are delivering this qualification, go to Teach Cambridge for complete planning, teaching and assessment support materials.

Our A Level in Religious Studies provides a coherent and thought-provoking programme of study. Students develop their understanding and appreciation of religious beliefs and teachings, as well as the disciplines of ethics and the philosophy of religion.

Specification code: H573 Qualification number: 601/8868/6 This qualification is available in English only

Our AS Level in Religious Studies provides a coherent and thought-provoking programme of study. Students develop their understanding and appreciation of religious beliefs and teachings, as well as the disciplines of ethics and the philosophy of religion.

Specification code: H173 Qualification number: 601/8869/8 This qualification is available in English only

Resource materials

Information, getting started, case studies and support

Example planning guides, teaching activities and more.

Practice papers, example answers, past papers and mark schemes

Upcoming professional development

Starting to teach: a level religious studies h573 (webinar).

CPD course • Online webinar • FREE • AS and A Level Religious Studies - H173, H573

Date: 19 Jun 2024 4pm-5pm

Ready to choose this qualification?

OCR A-Level RS Past Papers

This section includes recent A-Level Religious Studies (RS) (H573) and AS-Level Religious Studies (RS) (H173) past papers from OCR. You can download each of the OCR A-Level Religious Studies (RS) past papers and marking schemes by clicking the links below.

June 2022 OCR Religious Studies A-Level Past Papers (H573)

A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/01) Philosophy of Religion

A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/02) Religion and Ethics

A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/03) Developments in Christian Thought

A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/04) Developments in Islamic Thought

A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/05) Developments in Jewish Thought

A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/06) Developments in Buddhist Thought

A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/07) Developments in Hindu Thought

Download ALevel Past Papers - Download ALevel Mark Schemes

November 2021 OCR Religious Studies A-Level Past Papers (H573)

November 2021 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/01) Philosophy of Religion

November 2021 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/02) Religion and Ethics

November 2021 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/03) Developments in Christian Thought

November 2021 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/04) Developments in Islamic Thought

November 2021 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/05) Developments in Jewish Thought

November 2021 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/06) Developments in Buddhist Thought

November 2021 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/07) Developments in Hindu Thought

November 2020 OCR Religious Studies A-Level Past Papers (H573)

November 2020 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/01) Philosophy of Religion

November 2020 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/02) Religion and Ethics

November 2020 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/03) Developments in Christian Thought

November 2020 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/04) Developments in Islamic Thought

November 2020 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/05) Developments in Jewish Thought

November 2020 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/06) Developments in Buddhist Thought

November 2020 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/07) Developments in Hindu Thought

November 2020 OCR Religious Studies AS-Level Past Papers (H173)

November 2020 AS-Level: Religious Studies (H173/01) Philosophy of Religion

November 2020 AS-Level: Religious Studies (H173/02) Religion and Ethics

November 2020 AS-Level: Religious Studies (H173/03) Developments in Christian Thought

November 2020 AS-Level: Religious Studies (H173/04) Developments in Islamic Thought

November 2020 AS-Level: Religious Studies (H173/05) Developments in Jewish Thought

November 2020 AS-Level: Religious Studies (H573/06) Developments in Buddhist Thought

November 2020 AS-Level: Religious Studies (H173/07) Developments in Hindu Thought

Download AS Past Papers - Download AS Mark Schemes

June 2019 OCR Religious Studies A-Level Past Papers (H573)

June 2019 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/01) Philosophy of Religion

June 2019 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/02) Religion and Ethics

June 2019 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/03) Developments in Christian Thought

June 2019 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/04) Developments in Islamic Thought

June 2019 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/05) Developments in Jewish Thought

June 2019 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/06) Developments in Buddhist Thought

June 2019 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/07) Developments in Hindu Thought

June 2019 OCR Religious Studies AS-Level Past Papers (H173)

June 2019 AS-Level: Religious Studies (H173/01) Philosophy of Religion

June 2019 AS-Level: Religious Studies (H173/02) Religion and Ethics

June 2019 AS-Level: Religious Studies (H173/03) Developments in Christian Thought

June 2019 AS-Level: Religious Studies (H173/04) Developments in Islamic Thought

June 2019 AS-Level: Religious Studies (H173/05) Developments in Jewish Thought

June 2019 AS-Level: Religious Studies (H573/06) Developments in Buddhist Thought

June 2019 AS-Level: Religious Studies (H173/07) Developments in Hindu Thought

June 2018 OCR Religious Studies A-Level Past Papers (H573)

June 2018 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/01) Philosophy of Religion Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

June 2018 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/02) Religion and Ethics Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

June 2018 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/03) Developments in Christian Thought Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

June 2018 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/04) Developments in Islamic Thought Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

June 2018 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/05) Developments in Jewish Thought Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

June 2018 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/06) Developments in Buddhist Thought Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

June 2018 A-Level: Religious Studies (H573/07) Developments in Hindu Thought Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

June 2018 OCR Religious Studies AS-Level Past Papers (H173)

June 2018 AS-Level: Religious Studies (H173/01) Philosophy of Religion Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

June 2018 AS-Level: Religious Studies (H173/02) Religion and Ethics Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

June 2018 AS-Level: Religious Studies (H173/03) Developments in Christian Thought Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

June 2018 AS-Level: Religious Studies (H173/04) Developments in Islamic Thought Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

June 2018 AS-Level: Religious Studies (H173/05) Developments in Jewish Thought Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

June 2018 AS-Level: Religious Studies (H573/06) Developments in Buddhist Thought Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

June 2018 AS-Level: Religious Studies (H173/07) Developments in Hindu Thought Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

June 2017 OCR Religious Studies A-Level Past Papers (H172, H572)

Unit G581: Philosophy of Religion - Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

Unit G582: Religious Ethics - Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

Unit G583: Jewish Scriptures - Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

Unit G584: New Testament - Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

Unit G585: Developments in Christian Theology - Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

Unit G586: Buddhism - Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

Unit G587: Hinduism - Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

Unit G588: Islam - Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

Unit G589: Judaism - Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

OCR Religious Studies A-Level Past Papers (H172, H572)

OCR A-Level RS June 2016

Unit G571: Philosophy of Religion - Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

Unit G572: Religious Ethics - Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

Unit G573: Jewish Scriptures - Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

Unit G574: New Testament - Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

Unit G575: Developments in Christian Theology - Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

Unit G576: Buddhism - Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

Unit G577: Hinduism - Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

Unit G578: Islam - Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

Unit G579: Judaism - Download Past Paper - Download Mark Scheme

OCR A-Level RS June 2015

OCR A-Level RS June 2014

For more A-Level RS past papers from other exam boards click here .

- International

- Schools directory

- Resources Jobs Schools directory News Search

FREE OCR Religious Studies A Level: 40/40 Plato & Aristotle full essay plans

Subject: Religious education

Age range: 16+

Resource type: Assessment and revision

Last updated

10 April 2024

- Share through email

- Share through twitter

- Share through linkedin

- Share through facebook

- Share through pinterest

These notes provide everything you need to get 40/40 in Ancient Philosophical Influences: Plato and Aristotle questions. The plans are clear, easy to read and colour-coded so you can see AO1 and AO2. I’ve been tutoring OCR RS A Level for over a decade, and I have a degree in Theology from Cambridge.

I’m offering them for free as a sample of my wider set of essay plans for OCR RS.

These aren’t textbook-style notes explaining the thinkers. They cut straight to the point and give you 40/40 essays for all possible questions on Plato versus Aristotle for the OCR A Level.

These plans use a structure of six paragraphs, with two AO1 and four AO2. You could, instead, have paragraphs that mix AO1 and AO2. Whatever you do, two thirds of your essay should be AO2 because two thirds of the marks are AO2.

There are many other strengths and weaknesses of these theories, this is just one way of writing 40/40 essays. You may have to adapt a plan to the exact wording of the question set, but in OCR RS there are a small number of possible question themes and these plans cover all those themes, if not the exact wording of every possible question.

With Plato and Aristotle, you may get a question focusing on just one of them, or a question that mentions both. In either case, you can use a plan in which they argue with each other, as they are the main rival theories to each other.

There are three plans — one supporting Plato against Aristotle, one supporting Aristotle against Plato, and one for the narrower question on the Form of the Good vs the Prime Mover.

Creative Commons "Sharealike"

Your rating is required to reflect your happiness.

It's good to leave some feedback.

Something went wrong, please try again later.

Detailed essay plans with excellent A02 evaluation. I learnt a few new things about Plato and Aristotle that I did not know. My Year 13's loved this as a revision resources, thank you James. Any plans for more please? Also are you a member of the FB OCR group?

jamesjmoran

Thank you! I will be making more before the 2024 exams. And I'll join the Facebook group and perhaps find you on there!

Empty reply does not make any sense for the end user

Report this resource to let us know if it violates our terms and conditions. Our customer service team will review your report and will be in touch.

Not quite what you were looking for? Search by keyword to find the right resource:

OCR Religious Studies – Philosophy of Religion

The Philosophy of Religion exam paper in OCR A Level Religious Studies (H573/01) contains essay questions on the following topics:

- Ancient philosophical influences ( Plato and Aristotle )

- The nature of the soul, mind, and body (including dualism vs. materialism )

- The nature of God (i.e. as omnipotent , omniscient , omnibenevolent , etc.)

- Arguments for God’s existence (i.e. teleological , cosmological , and ontological )

- The problem of evil (including the logical and evidential versions and theodicies )

- Religious experience (including different explanations of religious experience )

- Religious language (including apophatic vs. cataphatic and 20th Century perspectives )

Ancient philosophical influences

Plato and Aristotle were ancient Greek philosophers who arrived at different conclusions about the fundamental nature of reality and how we can gain knowledge:

- Plato emphasises the role of a priori reason (rationalism)

- Aristotle emphasises the role of a posteriori observation (empiricism)

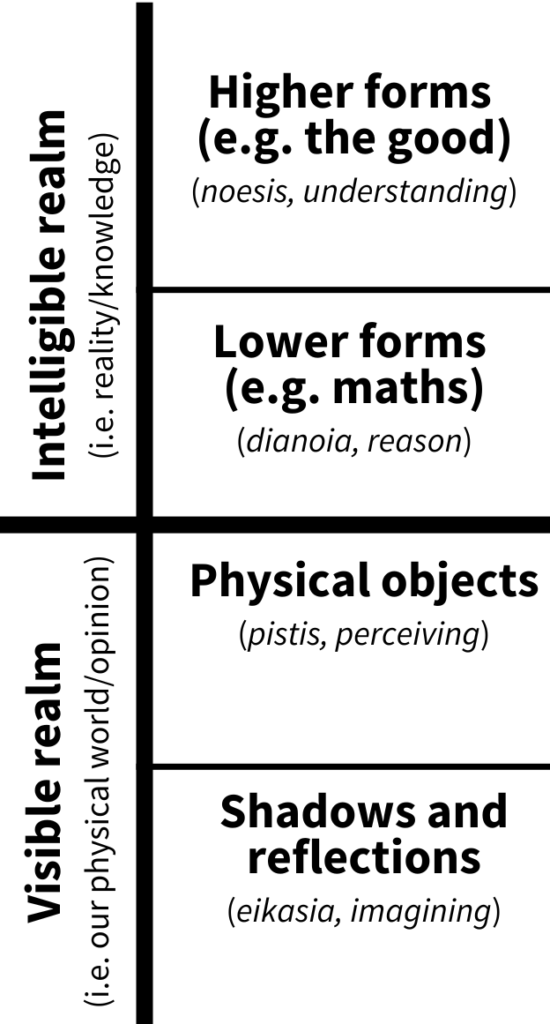

The theory of the Forms

Plato saw the physical world we inhabit as a kind of shadow or illusion – a poor representation of the true nature of reality. Physical things come and go, but Plato believed the true nature of reality must be eternal and unchanging. This eternal and unchanging reality is the world of the Forms .

For example, when you look at a beautiful painting, you experience a particular thing. But these particulars are just inaccurate and incomplete reflections of the Forms in which they participate – in the case of the painting, the Form of beauty .

Another example: You draw a triangle on a piece of paper. But however precisely you draw it, this particular triangle will never be a perfect triangle – only the Form of the triangle has perfectly straight sides and angles that add up to exactly 180°.

Basically, the world of the Forms is a world of perfect, eternal, and unchanging abstract objects, and this world of Forms is what reality is according to Plato.

- At the top of this hierarchy is the Form of the good.

- Beneath this are other higher Forms, such as justice and beauty, which partake in the Form of the good. For example, justice is a good thing, so partakes in the Form of the good, but is not goodness itself .

- Beneath these are the lower Forms, such as shapes and numbers.

- Lower still are actual physical objects – the world of appearances. These aren’t even Forms, they’re just temporary particulars that partake in the Forms. For example, a table is just a temporary particular that partakes in the Forms of tableness, squareness, etc.

Our senses (e.g. sight and sound) tell us about the physical world, but this isn’t knowledge according to Plato because it’s just perceptions of a temporary and changing realm. Our physical reality imperfectly reflects and distorts the Forms, which are the true nature of reality. To acquire proper knowledge of reality, according to Plato, we must use a priori methods (i.e. reason and understanding) to comprehend the world of the Forms.

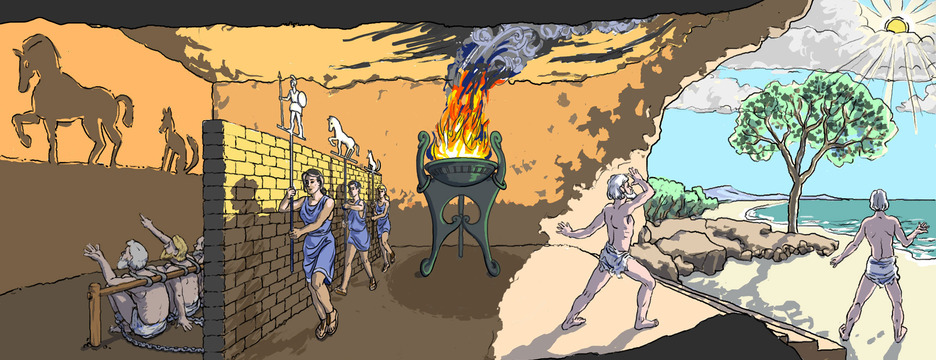

The allegory of the cave

Plato’s allegory of the cave illustrates the difference between:

- False knowledge of our physical world (i.e. appearances), and

- True knowledge of the world of the Forms (i.e. reality)

The allegory is as follows:

- Prisoners (who represent ordinary people ) are chained facing a wall in a cave, their heads tied so they can’t turn around.

- Behind them is a fire, and people parade objects in front of the fire, which cast shadows on the wall (these shadows represent our perceptions of the physical world ).

- The prisoners think these shadows are reality, because that’s all they ever experience.

- But one day, a prisoner is freed (this freed prisoner represents the philosopher ). Once he gets used to the brightness, he sees the fire and the real objects that cast the shadows.

- The freed prisoner then goes outside the cave. At first it’s so bright that he can only look at the shadows cast by objects. But once accustomed to the light, he is able to look at the objects (these real objects represent the Forms ) and, eventually, the sun itself (the sun represents the Form of the good ).

- If the freed prisoner were returned to the cave, his eyes would no longer be used to the darkness and he’d be unable to discern the shadows on the cave wall. If he told the other prisoners what he saw when he left the cave and how the shadows are not real, the other prisoners would think he’d been harmed from leaving the cave and had gone mad.

In addition to illustrating the difference between reality ( the Forms ) and appearances (the physical world), the allegory also illustrates the role of the philosopher: Once he sees the real world, he can’t go back to seeing the shadows. The philosopher sees it as their duty to educate the people still chained in the cave, but faces persecution for telling the truth (as did Plato’s teacher Socrates, who was sentenced to death for his teachings).

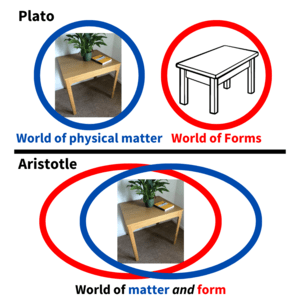

Where Plato rejects observation and experience as sources of knowledge ( for him this is like looking at shadows on the cave wall rather than actual objects ), Aristotle argues that a posteriori observation and experience enable us to work out the general principles that underlie change. By understanding the causes of change, we can understand the essence of things (their forms) and gain knowledge of reality.

The four causes

Aristotle believed that things naturally tend towards their telos (i.e. their purpose): They go from potentiality to actuality . For example, a seed may actually be a seed now, but it is potentially a tree. The seed tends towards its telos, which is to fulfil its potential and become an actual tree.

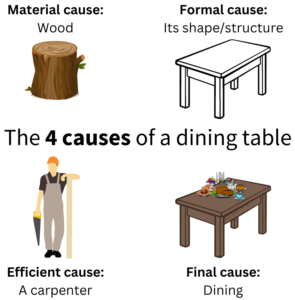

Aristotle identifies 4 causes (sometimes called the 4 explanations ) that underlie this change from potentiality to actuality:

- Material cause: What something is made from. For example, the material cause of a table might be wood or metal.

- Formal cause: The shape or arrangement of something. For example, the formal cause of a table might be its flat shape and legs.

- Efficient cause/agentic cause: Something apart from the thing that creates that thing. For example, the efficient cause of a table might be a carpenter who carved it from wood.

- Final cause: The purpose or ‘telos’ of something. For example, the final cause of a dining table would be to serve as a platform from which people eat their food.

These 4 causes underlie all change (the movement from potentiality to actuality ). By understanding these causes, we can understand the essence of things (i.e. their form) and gain knowledge.

The prime mover

Aristotle applied the 4 causes to the universe itself . He concluded that the final cause of the universe must be a prime mover .

Aristotle believed the default state of matter is rest. For example, if you roll a ball along the ground, it eventually stops moving and returns to rest. But things in our world are constantly moving and don’t stop. For example, the stars in the sky don’t just stop moving and return to rest – they keep moving forever. So how is motion within the universe sustained if the default state of things is to stop moving and return to rest?

Aristotle’s answer is that there must be something – a prime mover – that keeps this motion going:

- This prime mover can’t be moved by something else, because then this something else would need an explanation of what moves it, and so on for infinity. So, the prime mover must be unmoved and eternal .

- The prime mover is pure actuality and so never changes.

- The prime mover doesn’t cause this motion by pushing objects (so the prime mover is not the efficient cause of the universe). Instead, everything is naturally drawn towards the prime mover because things are naturally drawn towards their purpose/telos. It is this natural attraction of things towards the prime mover that sustains motion within the universe.

- This prime mover can’t be made of matter, because matter is subject to change. So, the prime mover is not a physical substance but a mind .

- But since the prime mover is unchanging, this mind can’t be thinking about anything outside itself because these thoughts would mean changes in the mind. So instead, the mind of the prime mover is eternally experiencing itself .

Note: This is basically an early version of the cosmological argument (see below).

The nature of soul, mind, and body

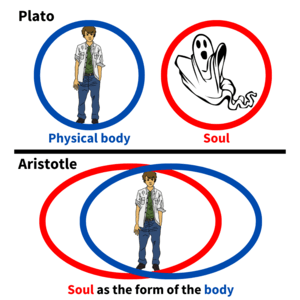

Plato vs. Aristotle on the soul

- Plato thinks the soul is separate from the physical body and made of completely different stuff (a view in line with dualism )

- Aristotle thinks the soul is inextricably linked with the physical body and so made from the same stuff (a view in line with materialism )

Plato’s view of the soul

According to Plato, just as reality consists of two parts – the unchanging and eternal world of the Forms and the temporary physical world of appearances – so too does a human being: There is the unchanging and eternal soul , which is separate from the changing and temporary body .

Plato saw the soul as originating in the world of the Forms. In the world of the Forms, the soul is eternal, unchanging, and possesses knowledge . However, the appetites/desires of the soul draw it to the physical world and into a temporary physical body. This physical body acts as a kind of prison for the soul. The body’s senses (e.g. eyesight, hearing) obscure the true nature of reality and can only give rise to opinion , not knowledge. But through reason, we are able to remember the world of the Forms and gain knowledge ( Plato uses Meno’s slave as an example to prove this – see the AQA philosophy notes for more detail ) . So, for Plato, all learning is just remembering things from the world of the Forms. When we die, the soul is freed from the prison of the body and returns to the world of the Forms.

Aristotle’s view of the soul

As we saw above , Aristotle rejects Plato’s separation of form from matter, but not the idea of form itself . For Aristotle, a thing’s form is its essence – and this essence exists within the object itself. For example, the essence of a table is its shape – a flat platform on which you can put things. This form exists within the object and not in a separate abstract world of Forms. Similarly, the essence of a human being is its soul – and this soul isn’t something that exists separate from the physical body.

Aristotle gives a couple of examples to illustrate this relationship: If the body was an axe , the soul would be its ability to cut things . If the body was an eye , the soul would be its ability to see things . Notice how these functions (cutting and seeing) are not the same thing as the physical object but are nevertheless inseparable from it. Likewise, the soul is not the same thing as the body, but is inseparable from it.

So, for Aristotle, the soul of a human being is its essence. This includes things like abilities (e.g. jiujitsu or carpentry) and personality (e.g. funny or angry).

Metaphysics of consciousness

In modern philosophy, the debate about souls has shifted more towards a debate about minds and consciousness .

This raises the question of what the conscious mind actually is . Broadly, there are two types of response:

- Substance dualists say the mind is a non-physical thing that can exist completely separate from the body

- Materialists say the mind is a physical thing

Substance dualism

For a more in-depth explanation, see the substance dualism notes for AQA philosophy.

Substance dualism is the view that the mind is a non-physical substance that is completely separate from the physical body.

Plato’s account of the soul above is along these lines. But the most famous substance dualist is probably Rene Descartes . Descartes gives several arguments for substance dualism, such as:

The cogito argument

Descartes’ cogito argument – I think, therefore I am – can be used to support substance dualism.

In this argument, Descartes doubts everything that is possible to doubt due to the possibility that an incredibly powerful evil demon could be deceiving him without his knowledge. It’s possible that, in reality, Descartes does not have a body at all and that his perceptions of hands and feet and legs and so on are just illusions created by this evil demon. However, even if such an extreme scenario were true, Descartes realises he cannot doubt the existence of his mind because there would have to be a mind for the evil demon to be deceiving in the first place! And so, the fact that Descartes is able to doubt the existence of his mind proves his mind must exist.

Descartes argues that the essence of the mind is a thinking thing – and this essence is not physical. In contrast, the essence of the body is a physical thing that does not think. These different essences suggest the mind and body are separate substances that could exist without each other.

For a more detailed explanation of this last point, see the conceivability argument .

The indivisibility argument

Descartes’ divisibility argument suggests that mind (i.e. mental stuff) and body (i.e. physical stuff) have different properties and so cannot be the same thing:

- My body is a divisible substance (e.g. you could chop my leg off)

- My mind is an indivisible substance (e.g. you can’t chop a thought in half)

- Therefore, my mind and body are different substances

For a more detailed explanation of the indivisibility argument and responses, click here .

Materialism

For a more in-depth explanation, see the physicalism notes for AQA philosophy.

Materialism (sometimes called physicalism ) is the view that everything that exists is physical or somehow related to the physical – and this includes the mind. In other words, consciousness can be explained entirely in physical terms.

Arguments for materialism include:

Two meanings of ‘soul’ (Dawkins)

Richard Dawkins distinguishes between two uses of the word ‘soul’:

- Soul 1: A non-physical entity that contains a person’s essence and is separate from their physical body (like how Descartes or Plato conceive of soul).

- Soul 2: A metaphorical way of speaking about a person’s essence (e.g. their core personality, mind, and values).

Dawkins says it’s fine to use ‘soul’ in the soul 2 sense. For example, you might describe an evil murderer as ‘soulless’, or talk about how a really great piece of music touched your ‘soul’.

But the notion of soul 1 should be rejected, he says. Dawkins sees soul 1 as an out-dated concept used to explain consciousness in times when we didn’t know better. Nowadays, modern science has replaced the need for soul 1 and we should explain consciousness in physical terms (e.g. biological processes in the brain). It’s like how, in ancient times, illnesses might have been explained by evil spirits but these explanations got replaced by scientific ones.

Category mistake (Ryle)

A category mistake is when one concept is confused for another. For example, to ask “how much does the number 3 weigh?” confuses the concept of number with the concept of things that have weight.

Gilbert Ryle thinks substance dualists make a similar category mistake when they talk about the mind as the kind of thing that exists independently of the physical body. He gives the following analogy to illustrate this:

- Someone asks you “what is Oxford University?”

- So you show them all the lecture halls, libraries, labs, teachers, and so on

- After showing them all this, they say “you’ve shown me the lecture halls, libraries, and labs, but what is the university ?”

To ask this question is to make the category mistake that Oxford University is a single thing independent of all the buildings etc. Likewise, Ryle says it’s a category mistake to think the mind is a single thing that exists independently of the physical body and behaviours.

For a more in-depth explanation, see the behaviourism notes for AQA philosophy.

Interaction issues for dualism (Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia)

If substance dualism is true, it’s hard to see how the mind interacts with the body (e.g. how your thought “I’m hungry” can cause you to move your physical body to the fridge to get some food) given that they are two completely different kinds of substance. Materialism doesn’t face this problem – it’s just physical stuff (mind) interacting with other physical stuff (body).

Descartes’ student, Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, made the following argument along these lines, which can also be used to support materialism:

- Physical things (e.g. the body) only move if pushed

- Only physical things can push physical things

- So, if substance dualism is true and the mind is a non-physical thing, the mind cannot move the body

- But the mind can move the body

- So, substance dualism is false (and materialism is true)

For a more in-depth explanation, see the interaction issues for dualism notes for AQA philosophy.

The nature of God

For a more in-depth explanation, see the concept of God notes for AQA philosophy.

God is typically understood to have the following divine characteristics:

Omnipotence

Omniscience, omnibenevolence.

- An eternal relationship to time

This topic looks at what these characteristics mean and whether it is possible for a being to possess them.

Omnipotence means God is all-powerful/the most powerful being possible/can do anything.

This might sound simple at first, but there is disagreement about what it means to say God can do anything .

God can do the impossible

This interpretation of omnipotence says God can do literally anything – even things that are impossible.

Here, we don’t just mean that God can do what’s physically impossible – like making gravity repel rather than attract objects, or making time flow backwards – we mean God can also do what’s logically impossible. In other words, God could make contradictions true. For example, God could make a 4-sided triangle, or make it so that 1+1=7. Such things might seem hard to imagine, but Descartes argues that finite human imagination is not an accurate guide to God’s infinite power.

However, this interpretation of omnipotence creates potential problems, such as:

- Self-contradictory: If God can do what’s logically impossible (e.g. make a 4-sided triangle), then it isn’t logically impossible at all!

- God becomes arbitrary: If God isn’t bound by any rules – even the rules of logic – then why choose to behave one way over the other?

- The problem of the stone : Could God create a stone so heavy He couldn’t lift it? Yes, according to this definition of omnipotence, God could create such a stone (because God can do literally anything). But then this would mean God couldn’t lift it (which would contradict God’s omnipotence)! This shows it is hard to make sense of a being that can do literally anything – including the impossible.

God can do anything logically possible

This interpretation of omnipotence says God can do anything that’s logically possible . In other words, God can do anything that does not involve a logical contradiction.

So, God can do anything physically (or metaphysically ) possible: He can make and destroy universes, change the laws of physics, resurrect the dead, and more. But God’s omnipotence does not mean He can violate the laws of logic and make a 4-sided triangle, for example. This is the approach taken by St. Thomas Aquinas, who argued that to say God can’t do the logically impossible does not impose any real limit on God’s power because what’s logically impossible isn’t anything at all – it’s meaningless .

Divine self-limitation

Another approach to omnipotence says that any limitations to God’s power are self-imposed .

For example, it may be that God really could do the impossible if He chose to, but that God decided to create and follow the laws of logic in order to provide consistency and order for the universe. Without the rules and structure of logic, everything would be too chaotic and nothing would make any sense (including human life), so God chooses to follow the rules of logic.

Eternal (or everlasting)

God is said to be eternal . This means God is timeless/exists outside of time. From this eternal perspective, what we call the ‘past’, ‘present’, and ‘future’ all exist within an eternal present. In other words, God perceives all moments in time simultaneously .

Anselm’s 4-dimensionalist approach builds on Boethius’ understanding of eternity. Physical space has 3 dimensions: Length, width, and depth. And we can think of time as a 4th dimension: All the 3 dimensions of physical space are contained within the present moment in time. Similarly, just as all 3 dimensions of space are present within the 4th dimension of time, all 4 dimensions are present within God. In other words, all of time is present within God in an eternal 5th dimension.

Everlasting

An alternative approach describes God’s relationship with time as everlasting rather than eternal. According to this view, God exists within time rather than outside of time. God existed at the beginning of time, can remember everything that has happened since, and will continue to exist forever.

Richard Swinburne argues that the everlasting interpretation of God is more consistent with the God of the Bible. In the Bible, God regularly intervenes in human affairs. For example, in Isaiah 38, Hezekiah is terminally ill and prays to God, who hears the prayer and extends his life by 15 years. Such a sequence of events only makes sense if God exists and can act within time.

Swinburne further argues that an eternal God would be unchanging and cold. It is only an everlasting God that would be capable of forming relationships with human beings and loving them, in line with the conception of God as omnibenevolent .

Omniscience means God is all-knowing/knows everything. Like omnipotence , God’s omniscience is interpreted in different ways:

- God knows literally everything (including e.g. the future)

- God knows everything that is possible to know

Many religions claim human beings have free will – the ability to freely choose or not choose their actions. One motivation for this claim is that if humans didn’t have free will, it would seemingly be unfair for God to reward or punish them them (e.g. through heaven and hell ), which would undermine God’s omnibenevolence .

However, free will raises another potential inconsistency: How do we reconcile free will with the claim that God is omniscient ?

- If God knows everything, then God knows what I’m going to do next

- If God already knows what action I’m going to do next, then it must be true that I do that action

- And if it must be true that I do that action, then I don’t have a free choice to do something different

So, this suggests either that we don’t have free will, or that God is not omniscient .

Potential ways to resolve this conflict differ depending on God’s relationship to time :

- Response: It is possible to know the future. For example, if you know your friend well, you can predict what food they’ll order at the restaurant. Plus, there are many examples of prophecies in the Bible (e.g. the coming of Jesus) that suggest God does know the future.

- Eternal : If God is eternal and exists outside of time, then what we call the ‘future’ is like the present to God. So, God could be observing – and thus know – our future actions as we freely choose them like how we observe other humans make free choices in the present ( see the AQA notes here for more ) .

Benevolence means someone has a disposition towards doing good. And so, God’s omni benevolence means God is perfectly disposed towards doing good.

Omnibenevolence is typically understood to mean two subtly different things:

- Emotional sense: God is perfectly loving , i.e. this is how God feels towards human beings and everything. In the Bible, this perfect love is illustrated by Jesus’ teaching to love your neighbour and even to love your enemies.

- Moral sense: God is perfectly good in a moral sense, i.e. God always acts in accordance with justice, what is right, and what is fair.

However, God’s omnibenevolence raises potential issues. For example:

- The euthyphro dilemma (see AQA notes for more) : Is God good because 1. He follows the moral law, or 2. He created the moral law? Option 1 challenges God’s omnipotence , because it suggests God is bound by rules outside of Himself. But if God creates the moral law (option 2), then in what sense is it meaningful to say God is ‘good’ when ‘good’ could have been whatever arbitrary thing God wanted! This challenges God’s omnibenevolence .

- The problem of evil: If God is perfectly good, why does He allow evil and suffering? For more on this, see below .

- The problem of hell: Many religions believe in hell as a place of eternal punishment for sins committed on earth. One reason hell may be in tension with God’s omnibenevolence is that this punishment is disproportionate and unjust. However bad someone’s sins were on earth, these sins will be finite in nature, but the punishment is infinite. The problem of hell may also be linked to God’s omniscience : An omniscient God would already know if someone was destined for hell even before they were born, in which case why create them just to suffer?

Arguments for God’s existence

The 3 classic types of argument for God’s existence are known as:

Teleological arguments

Cosmological arguments, ontological arguments.

The syllabus categorises them as arguments based on a posteriori observation ( teleological and cosmological ) and arguments based on a priori reason ( ontological ). And so, in addition to evaluating the specific arguments, you can also evaluate the general method.

Arguments based on observation

Teleological arguments and cosmological arguments argue that God exists based on a posteriori observations.

For a more in-depth explanation, see the teleological argument notes for AQA philosophy.

Teleological arguments are also known as arguments from design. These arguments observe that parts of nature (e.g. the human eye) appear so complex and perfectly suited for their purpose that they can only be explained with reference to an intelligent designer: God.

Aquinas’ 5th way

St. Thomas Aquinas gave 5 arguments for God’s existence, known as the 5 ways . The 5th way is a version of the teleological argument:

“We see that things which lack intelligence, such as natural bodies, act for an end, and this is evident from their acting always, or nearly always, in the same way, so as to obtain the best result. Hence it is plain that not fortuitously, but designedly, do they achieve their end. Now whatever lacks intelligence cannot move towards an end, unless it be directed by some being endowed with knowledge and intelligence; as the arrow is shot to its mark by the archer. Therefore some intelligent being exists by whom all natural things are directed to their end; and this being we call God.” – Aquinas, Summa Theologica , Part 1 Question 3

- For example, plants grow towards the sun so as to get more light so they can photosynthesise

- These actions always (or almost always) achieve the best result

- This can’t just be explained by luck, there must be an intelligence guiding these actions (like how an arrow won’t find its way to a target by luck, it has to be guided by the intelligence of an archer)

- This intelligence that guides these actions is God .

Paley’s teleological argument

William Paley considers the difference between things that are designed and things that aren’t designed .

The difference between the watch and the stone, Paley says, is that the watch has many parts (e.g. springs and cogs) organised for a purpose (i.e. to tell the time). This is the key hallmark of design .

Like the watch, aspects of nature have this hallmark of design. For example, the many feathers and shape of a bird’s wing are organised for the purpose of flight. The many parts of the human eye are organised for the purpose of sight. And since design can only be explained by a designer , nature must have a designer: God .

For a more in-depth explanation, see the cosmological argument notes for AQA philosophy.

Cosmological arguments start from the observation that everything has an explanation. For example, your existence can be explained by your parents, and their existence can be explained by their parents, and so on. Cosmological arguments seek an explanation of the existence of the universe itself. The argument is that the universe depends on something else to exist: God.

We saw Aquinas’ 5th way above , which is a teleological argument , but ways 1-3 are versions of the cosmological argument.

Ways 1 and 2 are very similar in structure, with one using the concepts of mover and movement , and the other using the concepts of cause and effect .

Aquinas’ 3rd Way (argument from contingency ) is a little different. Rather than talking about motion or cause and effect, it uses the concepts of necessity and contingency :

Using these concepts, the argument can be summarised as:

- Everything that exists contingently did not exist at some point

- And so, if everything that exists exists contingently, there would be a point at which nothing existed

- But if nothing existed, then nothing could begin to exist

- But since things did begin to exist, there was never a point at which nothing existed

- Therefore, there must be something that does not exist contingently, but that exists necessarily

- This necessary being is God

Arguments based on reason

Ontological arguments differ from cosmological arguments and teleological arguments in that they are based on a priori reason alone.

For a more in-depth explanation, see the ontological argument notes for AQA philosophy.

Ontological arguments argue that God exists based on the definition of ‘God’.

Anselm’s ontological argument

St. Anselm says God is ‘a being greater than which cannot be conceived’ . Using this definition, he deduces God’s existence in an argument that can be summarised as:

- God is, by definition, the greatest conceivable being

- It is greater to exist in reality than to exist only in the mind

- (because if God only existed in the mind, then He wouldn’t be the greatest conceivable being because we could conceive of a greater being: The one that exists in reality)

In the next chapter, Anselm expands on this definition of God:

“O Lord, my God,… thou canst not be conceived not to exist … And, indeed, whatever else there is, except thee alone, can be conceived not to exist . To thee alone, therefore, it belongs to exist more truly than all other beings, and hence in a higher degree than all others.” – St. Anselm, Proslogium , Chapter 3

Here, Anselm contrasts God’s necessary existence – “thou canst not be conceived not to exist” – with the mere contingent existence of things which “ can be conceived not to exist”. So, a bit like in Aquinas’ 3rd way above , Anselm believes God not only exists, but exists necessarily.

The problem of evil

For a more in-depth explanation, see the problem of evil notes for AQA philosophy.

The problem of evil is an argument that God does not exist because of the existence of evil and suffering in our world. Responses to the problem of evil are known as theodicies .

Versions of the problem of evil

There are two versions of the problem of evil:

- The logical problem of evil says God is logically inconsistent with the existence of any evil

- The evidential problem of evil says God’s existence is logically consistent with some evil but that if God existed there would be less evil and it would be more fairly distributed

The logical problem of evil

“Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is not omnipotent. Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent. Is he both able and willing? Then whence cometh evil? Is he neither able nor willing? Then why call him God?” – Epicurus

The logical problem of evil says, a priori , that God’s existence is logically incompatible with the existence of any evil.

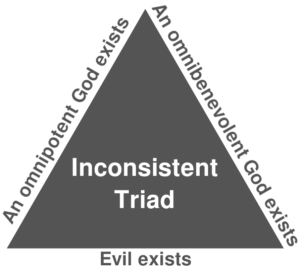

- An omnipotent God exists

- An omnibenevolent God exists

- Evil exists

The reasoning for this is that if 1 were true, God would be powerful enough to get rid of all evil. Plus, if 2 were true, God would want to get rid of all evil. So, if 1 and 2 were both true, evil would not exist because God would just eliminate it. However, evil does exist – people steal, get murdered, etc. – so either God is unwilling (not omnibenevolent) or unable (not omnipotent) to eliminate evil.

The evidential problem of evil

The evidential problem of evil allows that it is logically possible that an omnipotent and omnibenevolent God would allow some evil to exist (e.g. because of free will or soul making ), but argues that the unnecessary amount of evil in our world and unfair ways evil is distributed suggest God does not exist.

For example, we might accept that God would allow the evil of stealing because of the greater good of giving humans free will. But would an omnipotent and omnibenevolent God allow innocent babies to be born with painful congenital diseases? This seems unfair and has nothing to do with free will. There’s also pointless evils. For example, a deer gets burned in a forest fire in the middle of nowhere and dies a slow and painful death – and no one even knows about it. It seems God could easily have eliminated such pointless suffering without sacrificing some greater good.

If God is omnibenevolent, He wants to maximise good and minimise evil. And while it’s logically possible there is some mysterious and unknowable reason why our world is the most effective way to maximise good, the evidential problem of evil suggests this is highly unlikely . This is strong a posteriori evidence against God’s existence.

A theodicy is an explanation of why an omnipotent and omnibenevolent God would allow evil. In other words, theodicies are responses to the problem of evil:

- The Augustinian theodicy says evil is the result of the free will of humans to disobey God

- The Irenaean theodicy says evil is necessary for spiritual and moral development

The Augustinian Theodicy: Free will

St. Augustine explained the existence of evil as the result of free will . This is sometimes called the soul- deciding theodicy . According to Augustine, God is perfect and can only do good. However, evil and suffering occur because humans (and angels) use their free will to disobey God’s perfection. So, evil is not a thing itself, but a privation (lack) of good .

The Augustinian theodicy comes from the Biblical story of the Fall in the book of Genesis. According to this story, God initially made a perfect world without evil (the Garden of Eden) along with the first humans: Adam and Eve. God commanded Adam and Eve not to eat from the tree of knowledge, but a serpent (Satan) tempts them to disobey. Adam and Eve give in to temptation (because they have free will) and eat from the tree of knowledge, after which God banishes them from the Garden of Eden into a fallen world – our world – that contains evil.

“For God doth know that in the day ye eat thereof, then your eyes shall be opened, and ye shall be as gods, knowing good and evil.” – Genesis, chapter 3 verse 5 (KJV)

As descendants of Adam and Eve, all humans inherited their sinful nature (you can think of it like a sin gene ). This is known as original sin . Because of this original sin, all humans deserve to be punished.

The Irenaean Theodicy: Soul-making

John Hick explains the existence of evil as necessary for spiritual development . This is known as the soul- making theodicy .

The soul-making theodicy originates in the philosophy of Irenaeus (which is why it’s also referred to as the Irenaean theodicy ). According to Irenaeus, God’s ultimate plan for humanity is spiritual development. God deliberately made humanity spiritually immature and deliberately made the world a difficult environment. This difficult environment requires humans to make moral decisions, which enables them to learn and mature spiritually. God made humans in His image – with the free will to choose between good and bad – and God’s long-term plan is that creation will grow to his likeness and perfection, freely choosing the good over the bad.

“And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness.” – Genesis, chapter 1 verse 26 (KJV)

Free will is a big part of the soul-making theodicy. God could have just made humanity perfectly good from the get-go, but that would effectively remove free will. True goodness – goodness in God’s likeness – must be freely chosen.

Hick builds on this idea. Hick argues that God created an epistemic distance between Himself and humanity. This epistemic distance is a gap between humans and God – it means we can never know of God’s existence with 100% certainty. The reason for this again comes back to free will: If God made his existence and character obvious, we would have no choice but to follow Him (Peter Vardy likens this to a king forcing a peasant girl to marry him due to his authority even though she doesn’t love him). Instead, what God wants is a genuine and freely chosen decision to follow in God’s ways and choose good (to continue Vardy’s analogy, this is like marrying someone because you genuinely love them).

According to the soul-making theodicy, hell exists for further soul-making. It is not a place of eternal punishment but is instead a place where souls continue to exercise free will in the face of evil and which, eventually, they can escape from. Hick thus believes in universal salvation : The idea that everyone will go to heaven (eventually).

Religious experience

A religious experience is a subjective encounter that the experiencing person interprets as in some way religiously significant (e.g. as an encounter with God). The syllabus mentions two types of religious experience:

- Mystical experiences are experiences totally unlike ordinary perceptions. They can be hard to describe but common themes of mystical experiences include a feeling of experiencing the infinite and of experiencing unity with all things. This is often accompanied with strong feelings of ecstasy.

- Conversion experiences are experiences that lead someone to immediately and completely change their way of life. The classic example of this is Saul in the Bible. Saul initially persecuted Christians but, following a conversion experience where he met Jesus, converted to Christianity and became Paul the Apostle and founded several Christian communities.

This topic considers how these experiences should be understood and what conclusions, if any, we can draw from them.

William James: Features of religious experience

William James was a philosopher and psychologist. In his book, The Varieties of Religious Experience , James studied religious experiences across different cultures.

James identifies 4 features common to mystical religious experiences:

- Ineffable: The experience is indescribable . The subject can’t adequately put the experience into words.

- Noetic: The subject feels they gained knowledge or insight from the experience. In the case of religious experience, this is like direct knowledge of God that is deeper than can be reached by the intellect.

- Transient: The experience itself is short-lived in duration – usually less than half an hour (but the after-effects may be long-lasting or even permanent).

- Passive: The experience happens to the subject, it’s not something they actively make happen and is beyond their control.

Explanations of religious experience

The syllabus mentions the following explanations of religious experience:

Union with a greater power

Psychological explanations, physiological explanations.

Union with a greater power is the supernatural explanation that is used as evidence of God’s existence. This can be contrasted with the other two explanations – psychological and physiological – that say religious experiences have a natural explanation and so are not evidence of God’s existence.

William James’ conclusions

“I feel bound to say that religious experience, as we have studied it, cannot be cited as unequivocally supporting the infinitist belief. The only thing that it unequivocally testifies to is that we can experience union with something larger than ourselves and in that union find our greatest peace.” – William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience, Postscript

From his studies, James concluded that religious experience proves the possibility of union with a greater power .

It is important to note that this is not the same thing as proving God exists – as James himself points out. However, James does take religious experience to prove the existence of a spiritual dimension to reality. He concludes that the similarities between religious experiences across cultures suggests there is some truth to be found in all religions – an idea known as pluralism .

James believed all mystical religious experiences tap into this same spiritual reality, which is the core of of religion. Different cultures then develop their own beliefs and practices around these experiences – different religions. Studying these religious practices , for James, is ‘second-hand’ religion and less important than the direct mystical experience, which is first-hand contact with God or a greater spiritual power.

Swinburne’s principles of credulity and testimony

- Principle of credulity: We should accept our own perceptions as accurate unless there is good reason not to (e.g. you’re high on drugs). In other words: If you saw it, it’s probably real.

- Principle of testimony: We should accept others’ accounts of their experiences as accurate unless there is clear evidence against them (e.g. they’re a known liar or mentally ill). In other words: If someone says they saw something, it’s probably real.

Applied to religious experience, Swinburne would argue that if someone claims to have had an experience of God or ‘union with a higher power’, the principle of testimony says we should take this account at face value and accept it as accurate – unless there is good reason not to.

Natural explanations

Psychological explanations explain religious experiences as the result of mental processes , such as illusions and hallucinations.

Sigmund Freud, for example, believed religion to be a man-made psychological fantasy. He saw the mind as composed of different parts – conscious and subconscious – that interact with each other. According to Freud, religion fulfils several useful psychological purposes, such as:

- Fear of death: The religious belief in life after death alleviates the unpleasant fear of death.

- Guilt: The religious belief in God’s forgiveness (e.g. in the story of Jesus) alleviates the unpleasant feelings of guilt for bad things we’ve done.

- Safety: As children, our parents provide us with a sense of safety and security in a dangerous world. As adults, the world is still dangerous, but God provides that same feeling of safety and security (Freud would point to how God is referred to as ‘the Father’ as evidence for this).

Applied to religious experience, Freud would say such experiences are merely illusions that result from a person’s beliefs, fears, and desires surrounding religion. The subconscious forces of the mind are so powerful that they may cause someone to hallucinate a religious experience – a bit like in a dream – but such experiences are entirely a creation of the mind and do not reflect reality.

Physiological explanations try to explain religious experience by identifying the underlying physical processes that cause them, such as brain states and chemical factors.

Medical researchers Newburg and D’Aquili studied mystical experiences in an attempt to identify the underlying neural mechanisms. For example, through brain scans of monks and nuns engaging in religious practices (e.g. meditation and prayer), they identified areas of the brain – which they call the ‘causal operator’ and ‘holistic operator’ – which show increased activity during religious experience.

Similarly, Michael Persinger used a device – nicknamed the ‘ God helmet ‘ – to stimulate areas of the brain associated with religious experience via magnetic fields. According to Persinger, over 80% of participants felt they experienced a ‘presence’ with them, with some participants having perceptions of what felt to them like God.

Religious language

The religious language topic covers 2 different debates:

- The apophatic vs. cataphatic vs. symbolic debate is about how we can describe God when God is, by definition, far beyond human understanding.

- The 20th Century debate is about whether ‘God exists’ is a meaningful or meaningless statement, and whether it is the kind of statement that is capable of being true or false.

Negative vs. analogical vs. symbolic

Religions and sacred texts often talk about God as ‘infinite’, ‘eternal’, and ‘beyond understanding’. However, as finite and temporal beings, it is unclear whether we can even make make sense of such descriptions. In some Islamic traditions, for example, it is forbidden to depict or even imagine God because God is beyond human comprehension and so any representations will be inaccurate. So, this topic is about how we should describe and think of God, when God is beyond human understanding:

- The apophatic way (via negativa) says we can only describe what God is not .

- The cataphatic way (via positiva) says we can describe what God is – for example by making analogies with things in our own world.

- The symbolic way says words used to describe God are symbolic, not literal.

The apophatic way (via negativa)

Pseudo-Dionysus argued that positive descriptions of God create an anthropomorphic (i.e. human) and inaccurate idea of God. If we think of God’s power, for example, we will inevitably think of powerful human beings (e.g. presidents or business leaders) and this will create a picture of God’s power as somehow similar. However, God’s power is beyond human comprehension and so such comparisons are inaccurate – it is only appropriate to think of God’s power in an apophatic way.

The cataphatic way (via positiva)

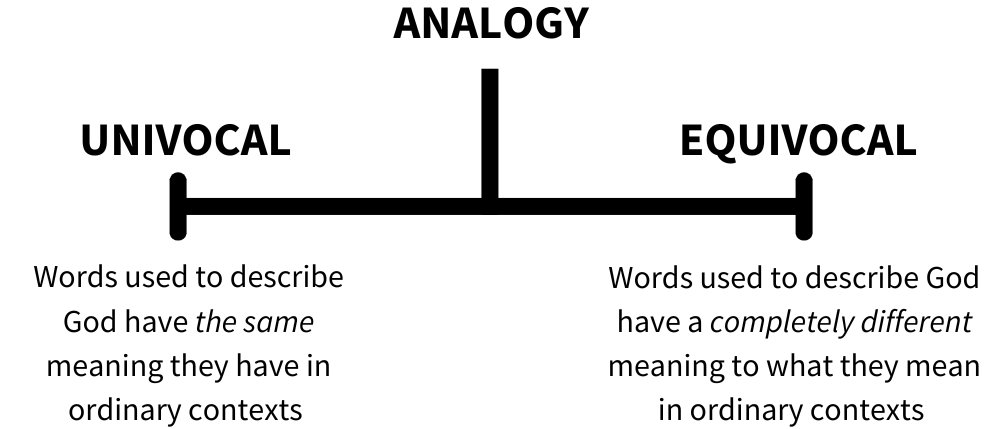

St. Thomas Aquinas argued that, by analogy (i.e. comparison), we can understand God’s positive qualities – at least partially .

Positive words used to describe God, such as ‘powerful’ and ‘loving’, are not univocal – they don’t have the same meaning as when we describe human beings – because human beings aren’t the same as God. But nor do these words have a completely different meaning either – they’re not equivocal – because humans were made in God’s image .

So, Aquinas advocates for a middle ground: Analogy . Words used to describe God resemble words used to describe human beings:

- Analogy of attribution: We can say there is a causal relationship between properties of human beings and properties of God. Aquinas illustrates this with an example using the medical understanding of his day: A healthy cow will produce healthy urine, and so we can get an idea of the cow’s health from the cow’s urine . Similarly, as God is the cause of human beings, we can get a vague idea of God’s power and love from looking at human examples of power and love.

- Analogy of proportion: We should understand the extent to which something has a property in proportion to the kind of thing it is. For example, we might call a 3 year old who can read a book ‘clever’, but we wouldn’t apply the same standard of ‘clever’ to a 20 year old PhD student. As God is infinite , we should understand God’s properties – power, love, knowledge, etc. – in proportion to that.

The symbolic way

The symbolic way of talking about God says that words used to talk about God should not be understood literally as descriptions, but symbolically .

Paul Tillich argues that literal language is unable to adequately express God. Literal language describes things in our empirical world that we can understand – but God is beyond the physical world and beyond our understanding. So, the meaning of religious language is almost entirely symbolic.

“That which is the true ultimate transcends the realm of finite reality infinitely. Therefore, no finite reality can express it directly and properly…. Whatever we say about that which concerns us ultimately, whether or not we call it God, has a symbolic meaning… If faith calls God “almighty,” it uses the human experience of power in order to symbolize the content of its infinite concern, but it does not describe a highest being…” – Paul Tillich, Dynamics of Faith

According to Tillich, religious language taps into “hidden depths of our being” a bit like how art and music “reveal elements of reality which cannot be approached scientifically” . As such, the meaning of religious language is to point to a higher reality that cannot be expressed literally. When people hear religious statements, such as “God loves us”, these symbolic expressions connect them to a spiritual reality beyond what is or can be expressed in literal or scientific language.

Symbolic religious language not only points to this higher spiritual reality, it also participates in it. Tillich differentiates between signs and symbols . A sign simply points to something (e.g. an arrow pointing to a McDonalds) whereas a symbol points to and participates in the thing (e.g. a nation’s flag represents the nation itself – disrespect towards the flag is seen as disrespect towards the nation).

Religious language is similarly symbolic: The cross, for example, does not only point to God but also represents Jesus’ sacrifice. By representing and participating in this spiritual reality, religious language connects us to something beyond the physical world in a way that literal language is unable to.

20th Century perspectives

For a more in-depth explanation, see the religious language notes for AQA philosophy.

The 20th Century debate concerning religious language is about what people mean when they make religious claims such as “God loves us”, “God answers prayers”, and “God exists”. Are such claims even meaningful?

At first, it might seem obvious that such claims are meaningful. When religious people say “God exists”, they are describing the world and expressing a belief. In the language of philosophy, they are making a cognitive statement that they believe to be true . However, some philosophers disagree with this analysis of religious language:

- The logical positivists say “God exists” is meaningless because it can’t be verified .

- Falsificationism says “God exists” is meaningless because it can’t be falsified .

- Wittgenstein takes a non-cognitive approach, arguing that “God exists” is not a description of the world that is either true or false. Instead, the religious believer is doing something like expressing their commitment to a particular – religious – way of life.

Logical positivism

The key view of logical positivism is the idea that for a statement to be meaningful and capable of being true or false, it must be verifiable .

AJ Ayer was a key figure in the logical positivist movement. Ayer’s verification principle says that a statement is only meaningful if it is either:

- An analytic truth, i.e. logical truths, such as mathematical statements (e.g. “1+1=2”), and things that are true by definition (e.g. “triangles have 3 sides”).

- Verifiable, i.e. there must be some observation or test (at least in principle) that would prove the statement is true. For example, even if the technology didn’t exist yet, you could in principle verify the statement “there is water on Mars” by sending a space ship to Mars and finding water there.

Applied to religious language, Ayer’s verification principle says that it is meaningless . There is no experiment or test, for example, that could verify God’s existence.

Falsificationism

Karl Popper argued that meaningful scientific claims must be falsifiable : There must be some possible observation or test that could in principle disprove the claim.

For example, “water boils at 100°c” could be falsified by heating some water to 999°c without it boiling and so is a meaningful claim. In contrast, there is no test that could disprove the claim “everything in the universe doubles in size every 10 seconds” because any measurement device used to prove the claim would also double in size. Thus, “everything in the universe doubles in size every 10 seconds” would be meaningless according to Popper.

Anthony Flew applied this idea of falsification to religious language. He gave the following analogy intended to illustrate how God’s existence is unfalsifiable and thus meaningless:

- Two explorers find a clearing in a jungle. Both weeds (these represent evil ) and flowers

- (these represent good ) grow here.

- Explorer A says the clearing is the work of a gardener (who represents God ). Explorer B ( atheist ) disagrees.

- To settle the argument, they keep watch for the gardener.

- After a few days, they haven’t seen him, but Explorer A says it’s because the gardener is invisible .

- So, they set up an electric fence and guard dogs to catch the gardener instead.

- But, after a few more days, they still haven’t detected the gardener.

- Explorer A then says that not only is the gardener invisible, he’s also intangible , makes no sound, has no smell, etc.

- Explorer B asks: What is the meaningful difference between this claim and the claim that the gardener doesn’t even exist?

In other words, Explorer A’s theory is unfalsifiable – nothing could possibly prove it wrong. Every time they put the theory to the test with observations, Explorer A come up with a reason why those observations don’t disprove it. And so, because it is unfalsifiable, Explorer A’s theory is meaningless .

Flew says it’s a similar thing with belief in God: We can’t see God, hear God, touch God, etc. We can’t even use the problem of evil as evidence against God’s existence because the religious believer just creates reasons why an omnipotent and omnibenevolent God would allow evil. Flew argues that because the religious believer accepts no observations count as evidence against belief in God, the religious believer’s hypothesis is unfalsifiable and meaningless.

Language games and form of life (Wittgenstein)

Ludwig Wittgenstein’s later philosophy argues that the meaning of words is not some static thing that is the same in all contexts. Instead, meaning comes from how words are used – and the same words may be used differently in different contexts and by different people.

Just as different games have different rules, different contexts give rise to different language games . Compare, for example:

- “The bus passes the bus stop”

- “The peace of the Lord passes all understanding”

Although these two statements have the same structure on the surface , they clearly mean two completely different things – they’re ‘moves’ within two different language games.

Verificationists like Ayer analyse “God exists” within the language game of science – they treat it like a hypothesis that can be empirically proved or disproved. But Wittgenstein would argue religious believers aren’t playing the scientific language game when they say “God exists” – they’re playing the religious language game. And so, to analyse “God exists” within the scientific language game is to misunderstand what it means.

For Wittgenstein, the proper way to understand religious language is as a form of life . This is a bit like a wider language game – it’s someone’s foundational way of seeing the world:

“It strikes me that a religious belief could only be something like a passionate commitment to a system of reference. Hence, although it’s belief , it’s really a way of living, or a way of assessing life. It’s passionately seizing hold of this interpretation.” – Wittgenstein, Culture and Value

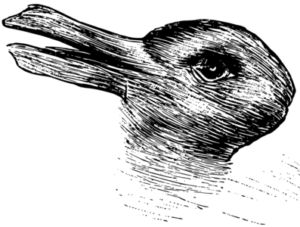

It’s a bit like the duck-rabbit picture above: It’s not like the duck is ‘right’ and the rabbit is ‘wrong’ or vice versa – they’re two different ways of seeing the same thing. Likewise, it’s not like “God exists” is ‘right’ and “God does not exist” is ‘wrong’ – they’re two different interpretations of the world that reflect different forms of life.

Non-cognitivism

Wittgenstein’s analysis of religious language is interpreted by some as non-cognivitist .

Non-cognitivist interpretations of religious language say “God exists” is not a description of the world that is either true or false. Instead, it is something non -cognitive – it is neither true or false.

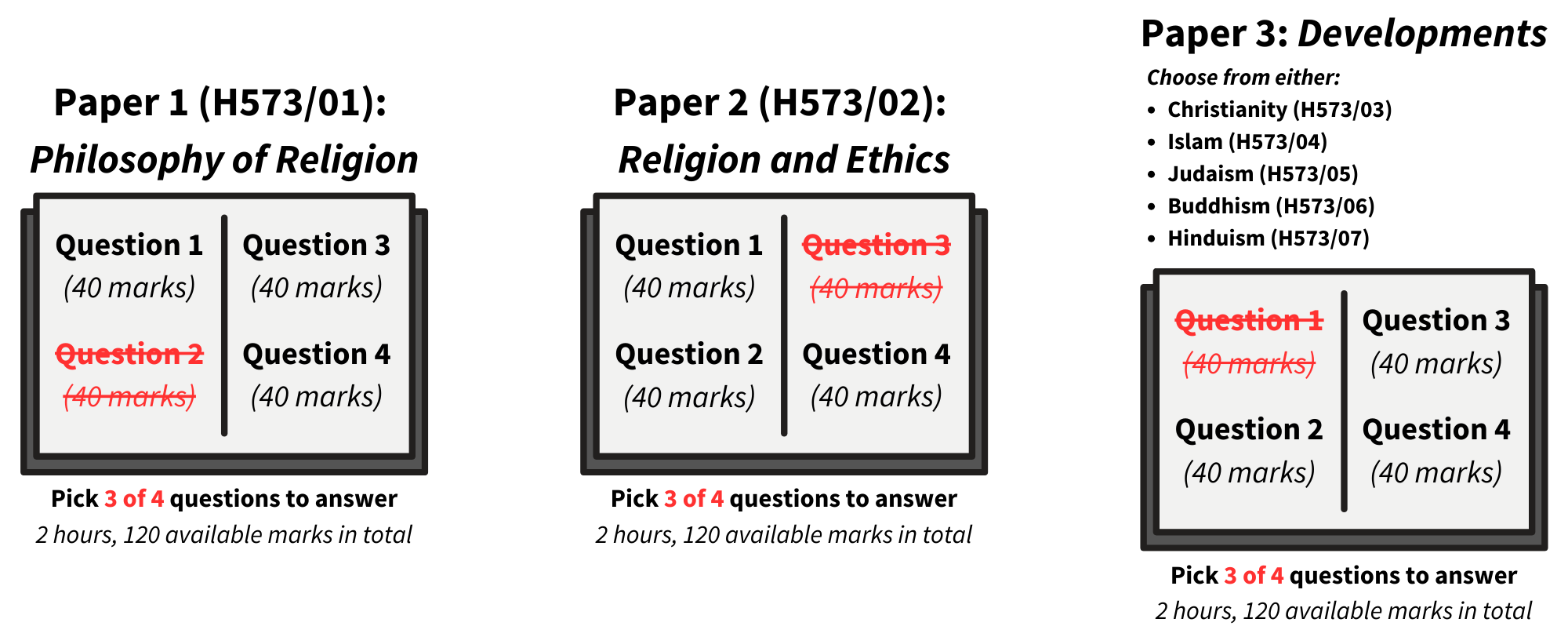

The OCR Religious Studies A Level is assessed via 3 exam papers:

Paper 2: Religion and Ethics>>>

Paper 3: developments in religious thought >>>.

A Level Philosophy & Religious Studies

This page: full notes A* summary notes C/B summary notes

Theories on the value of life.

Euthanasia being morally acceptable or not will depend on which view of the value of life is correct and, if relevant to the theory, on the particular type of euthanasia or situation involved.

The Sanctity of life

The conservative, sometimes also called the ‘strong’ sanctity of life view, claims that because God created human life, only God has the right to end it. Humans were created in God’s image, further suggesting that human life is especially valuable

Both conservative Catholics and protestants believe that the strong sanctity of life principle is justified by the Bible. Catholics would also think that Natural Law ethics provides justification for the conservative sanctity of life principle.

The sixth of the ten commandments is “thou shalt not murder”

“Your body is a temple of the holy spirit, who lives in you and was given to you by God. You do not belong to yourself” (1 Corinthians 6:19).

This quote clearly shows there is something sacred about the body such that destroying it would be like destroying a temple. It was given to us by God, implying a gift, and then very straightforwardly and clearly states that we do not belong to ourselves. We essentially do not have the right to take our own life.

“Whoever sheds human blood, by humans shall their blood be shed; for in the image of God has God made mankind.” Genesis 9:6.

This quote shows that the ultimate penalty is deserved for those who take life. The value of life is explained through its link to our being created in God’s image.

The weak sanctity of life view. Proponents of the weak sanctity of life principle criticise the strong version by pointing out that although the sanctity of life is found in the Bible, it is only one of many biblical principles and themes. So, although sanctity of life is important in judging the value of life, there are other principles that should also be included, such as Jesus’ emphasis on compassion. The problem with the strong sanctity of life view is that it allows unnecessary suffering and is uncompassionate, seeming to ignore the demands of compassion. In some cases, then, compassion for the quality of life might outweigh the sanctity of life.

However, although the Bible does have the theme of compassion, that doesn’t mean it can be used to overrule the sanctity of life. The Bible clearly is against killing. There is no exception mentioned for the sake of compassion. Although the Bible says to be compassionate, it doesn’t follow that it is Biblical to go against the sanctity of life when it would be compassionate to do so.

Quality of life

Quality of life refers to how happy or unhappy a life is. Proponents of the quality of life in relation to euthanasia regard it as a valid ethical consideration because they think that life has to be of a certain quality in order for it to count as worth living.

Peter Singer believes the quality of life to be an important factor in euthanasia. He goes as far as recommending non-voluntary euthanasia for babies whose potential quality of life is low, such as due to being born with an incurable condition like spine abifida.

Peter Singer’s criteria for personhood are rationality and self-consciousness. He distinguishes between ‘humans’ (members of our species) and ‘persons’ (rational self-conscious beings). Not all humans are persons. Singer argued that belief in the sanctity of life of members of our species (humans) was based on ‘Christian domination of European thought’, especially belief in an afterlife and that God had ownership of us, his creation. He proposes that since Christian theological tenants are no longer accepted, we should re-evaluate Christian ethical precepts too.

Singer argues that if we think about what we find wrong with killing someone, it is that it deprives them of the life they want to continue live. A consequence is that if euthanasia is voluntarily asked for by a competent adult, then it would not be wrong because they don’t want to continue living their life. In the case of non-voluntary euthanasia for babies or patients in a vegetative state, they have no sense or conception of their life, let alone their life continuing. So, it’s not morally wrong to kill them because it doesn’t deprive them of anything that they are able to have a preference to not be deprived of.

The slippery slope & effect on vulnerable people. Archbishop Anthony Fisher makes the slippery slope argument against the quality-of-life view, arguing that wherever euthanasia is legalised, it is extended to more and more people. He points out that in Holland euthanasia was legalised for the terminally ill but 10 year later was legalised for babies in cases of severe illness.

Fisher further argues that if Euthanasia is allowed for quality of life, then some elderly or otherwise vulnerable people might be tempted to die because they feel like a burden. Western culture values success, self-sufficiency, productivity and beauty. Those who fall short can feel miserable as a result. If we allow euthanasia, such people might feel encouraged to die because they feel like failures.

Adding to Fisher’s argument, In 2022 in Canada there was a controversy over two high profile cases of people with medical conditions for which they received insufficient financial support applying for euthanasia. One called Denise saying they have applied for euthanasia “because of abject poverty”.

The valid ethical approach would be changing our society, not allowing euthanasia. Those who advocate for euthanasia think they stand for compassion, not realising they are the unwitting executioners for our merciless success-driven society.

Singer responds that people who receive euthanasia in Oregon are disproportionately white, educated and not particularly elderly, so euthanasia does not especially target vulnerable people.

Singer adds that there is no creep of euthanasia becoming more widespread. He points out how in Oregon only one in three thousand deaths are by euthanasia. Genetic screening allowing mothers to know if their baby has a condition before its born and aborting it meant the post-birth non-voluntary euthanasia numbers dropped from 15 in 2005 to 2 in 2010.

We can conclude that Fisher’s points are not criticisms of euthanasia per se . They highlight the problem with allowing euthanasia in a society which lacks proper support for those who need it. Arguably it at most suggests that euthanasia must be combined with proper support for the vulnerable, not that euthanasia cannot be justified.

Autonomy is the freedom of people to make their own choices. This isn’t directly a view on the value of life, but it is the view that the decision about whether a life is valuable ought morally to be up to the individual whose life it is. There are two approaches to autonomy: deontological and consequentialist.

The deontological (absolutist) view of autonomy. Nozick is a libertarian, meaning he thinks people have an absolute right to do whatever they want, so long as they are not harming others, no matter the situation. He argued for the principle of ‘self-ownership’, meaning we essentially have property rights over our own lives and bodies. This results in a deontological view of autonomy regarding euthanasia. If a person wants to die and receive help from others (making it euthanasia) then that is their right.

However, Nozick’s approach seems to have enormous downsides. People will choose euthanasia for short-sighted reasons such as when in the temporary grip of negative emotion. Singer takes a more consequentialist view of the value of autonomy. He’s not an absolutist about autonomy as he says he doesn’t want to make it easy for people to end their lives when they have a treatable condition or when they might easily recover. He gives the example of a young person wanting euthanasia due to depression over relationship issues. Singer argues we can ‘safely predict’ that they will come to view their life as worth living again and the value of that ‘overrides’ the temporary violation of their autonomy when denying them euthanasia.

The consequentialist view of autonomy. Singer’s consequentialist approach to autonomy was influenced by Mill. Mill did not comment on euthanasia directly, but his philosophy formed the basis for justifying the autonomy principle. Mill developed political liberalism. Before the enlightenment, religion told people what to do. Mill thought that people would be happier if granted individual freedom. Individual people are in the best position to judge what is best for them and have the greatest motivation to ensure they live the best lives possible. This shows that euthanasia should be left to the autonomy of a competent adult.