- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Sociology

Discourse Community Essay Examples

Discourse community essay is an essential part of academic writing that requires students to explore a specific group’s communication methods and practices. To write a successful discourse community essay, you need to understand the group’s language, values, and beliefs. Here are some tips on how to write a discourse community essay that stands out.

Firstly, before writing, conduct thorough research on the discourse community you wish to write about. Understanding the group’s communication methods, practices, and language is essential. Take time to observe the community’s communication methods and the roles of its members. Conduct interviews with members of the group to gain insights into their communication practices and understand their perspectives.

Next, brainstorm discourse community essay topic ideas that align with your research. This should help you identify the unique aspects of the discourse community that you would like to focus on in your essay. Ensure that your essay is well-structured and well-researched to make it informative and easy to read. You can also use the research to draw comparisons and contrasts between the discourse community you are writing about and other groups.

To make your essay stand out, include relevant discourse community essay examples to illustrate the communication methods and practices you are discussing. This will give your readers a better understanding of the group you are writing about and make your essay more engaging. You can also include personal experiences or stories that relate to the discourse community to make your essay more relatable.

In conclusion, writing a discourse community essay requires a lot of research and attention to detail. However, with the right approach and techniques, you can produce a well-structured and informative essay that highlights the unique communication practices of the group. Always remember to include relevant examples and personal experiences to make your essay more engaging.

The Soccer Discourse Community: Passion, Identity, and Global Connection

Soccer, known as football to most of the world, is more than just a sport; it is a universal language that transcends geographical borders and cultural differences. Within the realm of this beloved game lies a dynamic and tightly-knit soccer discourse community. This essay explores...

- Discourse Community

The Nursing Discourse Community: Shared Knowledge and Collaboration

Nursing is a noble and demanding profession that thrives on collaboration, empathy, and the exchange of knowledge. Within the vast healthcare landscape, the concept of a nursing discourse community emerges as a dynamic network of professionals who share a common language, values, and goals. This...

Highly Resistant Hegemonic Discourses in the Sport

This essay will look at highly resistant hegemonic discourses in sport that relate to ethnicity and race, and whether these discourses have been successfully challenged by the promotion of alternative discourses in recent years. Therefore, both the highly resistant discourses and the new alternative discourses...

- Discourse Analysis

The Discourse Community Analysis Of A Football Team

I came to UC Merced and joined Writing 001 with no knowledge of what a discourse could be. Now in Lovas’s class reading “Superman and Me” by Sherman Alexie. I had no idea what a discourse community was, the idea of this is very well...

K-Pop: Unveiling Its Discourse Community and Influence

The major difference between humans and animals is the ability to communicate with each other. Throughout the course of human development, people need a way for mass communication to reach a final decision or to represent a certain point of view or belief. This can...

Stressed out with your paper?

Consider using writing assistance:

- 100% unique papers

- 3 hrs deadline option

Exploring the Discourse Community of Personal trainers or Fitness instructors

Introduction As a newly certified Coach and professional personal trainer, I am writing this report for the new comer to the discourse community of personal trainer. What is the history of this community? What are its primary mechanisms of intercommunication? What kind of threshold levels...

The Communities That I Belong To

The concept of a discourse community is ambiguous in nature. Despite that, one thing can be said for sure—that most of us, in one way or another, belong to one. As defined by John Swales, discourse communities are people who use communication to reach a...

- Intercultural Communication

The Goals of the Sociology Discourse Community and the Issues within It

Introduction Discourse community is defined in the Genre Analysis as the “Increasingly common assumption that discourse operates within conventions defined by communities, be they academic disciplines or social groups”. (Herzberg Pg. 21). As this is a very simple break down of the term discourse community,...

- Interpersonal Communication

The Key Role of Functionalism in a Societal Equilibrium

Functionalism emphasizes a societal equilibrium. To put it into perspective if something happens to disrupt the order and the flow of the system, a set of interconnected parts which together form a whole, society must adjust to achieve a stable state. Functionalism is a top...

- Emile Durkheim

- Functionalism

The Theoretical and Practical Application of the Functionalism Theory

Functionalism became the most well known within the end of the 20th century. (Knox (2007) pg. 2) Although, functionalism has several antecedents in ancient philosophy and early theories of A.I and technology as well. The first view that one can possible argue to be a...

Conversation as a Target of Discourse and Disciple Analysis

Discourse as Nunan (1993) defines it is ‘a stretch of language consisting of several sentences which are perceived as related in some way’; Within the definition of discourse, it can be found that discourse refers as much spoken as written kind of languages. However, many...

- Anthropology

- Conversation

A Study of Discourse Community Through BLM Movement

A discourse community is a group of people who share a set of goals, which are basic values and assumptions, and ways of communicating about those goals. The ability to communicate is very important to a discourse community. It is important because without communication the...

- Black Lives Matter

Analysis of Nursing Community According to Swales' Characteristics of Discourse Community

A discourse community is people with similar interest and goals in life, who share a language that helps them discuss and accomplish these interests and goals. In the nursing community, many code words are used for different events and situations. All nurses maintain the same...

School Theatre as an Example of Discourse Community

Everyone has successfully been able to join a discourse community. School clubs, sports teams, teachers, a job, a group of friends, or even a family can be classified into two words discourse community. According to James Paul Gee, “a discourse is a sort of identity...

Music in My Life: Being a Part of Musical Discourse

A discourse community is defined as “A group of people who share a set of discourses, understood as basic values and assumptions, and ways of communicating about those goals. ” An easier way of wording the definition comes from Linguist John Swales and he defines...

- Music Industry

Best topics on Discourse Community

1. The Soccer Discourse Community: Passion, Identity, and Global Connection

2. The Nursing Discourse Community: Shared Knowledge and Collaboration

3. Highly Resistant Hegemonic Discourses in the Sport

4. The Discourse Community Analysis Of A Football Team

5. K-Pop: Unveiling Its Discourse Community and Influence

6. Exploring the Discourse Community of Personal trainers or Fitness instructors

7. The Communities That I Belong To

8. The Goals of the Sociology Discourse Community and the Issues within It

9. The Key Role of Functionalism in a Societal Equilibrium

10. The Theoretical and Practical Application of the Functionalism Theory

11. Conversation as a Target of Discourse and Disciple Analysis

12. A Study of Discourse Community Through BLM Movement

13. Analysis of Nursing Community According to Swales’ Characteristics of Discourse Community

14. School Theatre as an Example of Discourse Community

15. Music in My Life: Being a Part of Musical Discourse

- National Honor Society

- Gender Roles

- Cultural Identity

- Gender Stereotypes

- Body Language

- Physical Appearance

- Arranged Marriage

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

1b. Discourse Communities

Overview + objectives.

Image Attribution: Saying hello in different languages by 1940162 Hari chandana C is licenced under a CC BY 4.0 licence , via Wikimedia Commons

The first major concept we discuss that will be the foundation of your reading and writing in Writing 121 is discourse community . Considering your discourse community can give your writing its audience, context, and purpose, which are crucial for motivating your writing. In this chapter, we will:

- Define discourse community

- Identify the various discourse communities of which you are a part

- Understand how a discourse community shapes your writing

- Consider ways to craft a unique voice within a discourse community

- Reflect on how knowledge of discourse community can improve your writing

What is a discourse community?

To define this concept, let’s break it down into its separate parts: discourse and community . We’ll start with the simpler word, community . A community is simply a group of people who are joined together by something they have in common. It could be a shared interest, such as a gaming community, a set of beliefs, such as a religious community, a similar geographical location, such as a local community, or a profession, such as the academic community. A family is a type of community. Your friends also form a community. Take a moment and think of the various communities to which you belong. What binds individuals together in these communities? Do members of these communities engage with each other virtually or in real life?

Next let’s look at the other word in this term, discourse . The word in its original usage meant reasoned argument or thought. However, in contemporary usage we sometimes think of it generally as any written or spoken communication, a conversation. We more often use it to refer to written or spoken communication related to a particular intellectual or social activity, such as scientific discourse or political discourse. In this sense, a synonym for discourse might be language . A discourse is defined by its unique language, vocabulary, themes, ideas, values, and beliefs. Think about your major. What are the unique characteristics of the discourse in your disciplinary or professional field?

Now let’s put our two words together, discourse community . Any guesses on what it means? If you are thinking that it is a group of people—real, imaginary, virtual, or otherwise—with shared interests, goals, language, and ways of communicating, then, yes, you’ve got it!

Image Attribution: Your WR 121 discourse community Discussion icons created by Freepik – Flaticon .

What does a discourse community look like?

Let’s work through a few examples. The following are five lists of words. Do you recognize any of the groups of words and what they have in common?

- CPA, general ledger, liabilities, return on investment, owner’s equity, net income, expenses (fixed, variable, accrued, operation)

- ISO, aperture, depth of field, autofocus, exposure, shutter speed

- gracias, de nada, salud, buen provecho, estadounidense, te quiero

- iron throne, direwolf, Khaleesi, the Wall, Valyrian steel, Night Walkers

- once a Duck always a Duck, show your “O,” Carson, EMU, it never rains in Autzen Stadium, Arts and Letters, Social Science, and Science groups

If you are a business major and have taken an accounting class, you’ve likely learned about the set of words in #1. If you are a photographer, you probably know the terminology in #2. If you speak Spanish, then you understand the words in #3. If you’re a Game of Thrones fan, then you recognize the words in #4. And if you are a UO student, then the words in #5 should seem familiar to you. Sco Ducks!

So you can see that discourse, or language, is one way that a community is bound together. It shapes it, strengthens it, and even defines it. The members of the community generally agree on what the terms mean; however, that is not always the case, as we will explore later in the course.

But what if you didn’t know a group of words? Let’s say you are in a conversation with a group of people using the technical terms in #2, but your only camera is your iPhone. Or perhaps you are reading an article that is in Spanish, but you don’t know that language. How would you feel? You would probably feel confused, frustrated, and excluded.

Because language and modes of communication differ among various groups, a discourse community can exclude others as much as it brings people together. Think about one of the communities to which you belong. What is the discourse of that group? What is the shared language and terminology? What are the primary ways of communicating between members of the community? How do members communicate their ideas or activities with those outside of the community?

What is a discourse community to which you belong and. . .

- What are the unique characteristics of communicating within this community?

- How has it shaped the way you think and write?

- Is it possible to assert your unique voice within that community? How so or why not?

Images (above, from left to right):

- Balance sheet: RODNAE Productions from Pexels

- Photography: Pxhere

- Dany: Creative Commons

- Puddles the Duck by Brian licensed under a CC BY SA 4.0 license via Wikimedia Commons

How does the discourse community shape your writing?

Image Attribution: Workshop by fauxels via Pexe l.

In his book on academic writing, The Shape of Reason , John Gage defines a discourse community as “any kind of community in which the members attempt to achieve cooperation and assert their individuality through the use of language. We are all members of discourse communities, each of which uses language in different ways” (2).

What keywords can you pull out of this definition? I identify the following keywords: cooperation , individuality , and language . A community generally assumes members who cooperate with each other. The group has a common goal or set of goals and its members want to work or live together to achieve those goals. They use a common language and mode of communication to maintain and strengthen the community. For an individual to thrive within this community, understanding and being able to use that common language and mode of communication are essential. When we as individuals have thoughts, ideas, or actions we would like to share with others in the community, we want to convey those thoughts, ideas, or actions in a way that others can understand and engage with them. No one likes to feel misunderstood. In this way, a discourse community influences how we communicate our individuality to the group.

We can illustrate how discourse community shapes your writing with a few examples. It is probably easy and fun for you to write and send texts to your friends. What kind of language do you use when texting? If your friend’s primary language is English, then you’ll probably use English in your texts. You’ll probably also use textspeak abbreviations like “lol” and “idk.” You might even use some visual language, such as emoji or gifs. If your friend does not speak English, does not know what the abbreviations stand for, or is unfamiliar with emoji, then they will not understand your message. Now, let’s say you are sending an email to your professor. Would you use the same discourse that you use when texting your friend? Probably not. In other words: an awareness of discourse community probably already shapes how you communicate your ideas.

This is all well and good when you feel confident about your membership in a community. But what about when you are new to a community? How do you learn that community’s discourse? Or what if you struggle to feel like you truly belong in a community? How do these things affect how you communicate and interact with the group? As you become more familiar with a community’s discourse, your written communication with the group will also improve. However, do you think it is possible to assert your unique voice and identity within the limits of a community’s discourse?

Let’s consider the university as a discourse community. The university comprises intellectuals (including you!) in various academic disciplines. Each academic discipline has its own discourse, but for the most part all academic disciplines communicate and share knowledge, as well as debate theories and ideas, through discussion and writing. What characterizes academic discourse ? What is academic writing ? Who gets to speak and write in this community?

Once you have read the sections on discourse community and thought about the various communities of which you are a part and the discourses used in these communities, you’re ready to get to know your WR 121 discourse community. What can you learn about your peers and instructor? What languages do they speak? What common goals do you all share? Do you agree on what effective writing looks like? What support will you offer each other as you work on your writing this term?

Acknowledgment:

Gage, John. The Shape of Reason , 4th Edition. New York: Pearson, 2006: 2.

Writing as Inquiry Copyright © 2021 by Kara Clevinger and Stephen Rust is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7 Understanding Discourse Communities

This chapter uses John Swales’ definition of discourse community to explain to students why this concept is important for college writing and beyond. The chapter explains how genres operate within discourse communities, why different discourse communities have different expectations for writing, and how to understand what qualifies as a discourse community. The article relates the concept of discourse community to a personal example from the author (an acoustic guitar jam group) and an example of the academic discipline of history. The article takes a critical stance regarding the concept of discourse community, discussing both the benefits and constraints of communicating within discourse communities. The article concludes with writerly questions students can ask themselves as they enter new discourse communities in order to be more effective communicators.

Last year, I decided that if I was ever going to achieve my lifelong fantasy of being the first college writing teacher to transform into an international rock star, I should probably graduate from playing the video game Guitar Hero to actually learning to play guitar. [1] I bought an acoustic guitar and started watching every beginning guitar instructional video on YouTube. At first, the vocabulary the online guitar teachers used was like a foreign language to me—terms like major and minor chords, open G tuning, and circle of fifths. I was overwhelmed by how complicated it all was, and the fingertips on my left hand felt like they were going to fall off from pressing on the steel strings on the neck of my guitar to form chords. I felt like I was making incredibly slow progress, and at the rate I was going, I wouldn’t be a guitar god until I was 87. I was also getting tired of playing alone in my living room. I wanted to find a community of people who shared my goal of learning songs and playing guitar together for fun.

I needed a way to find other beginning and intermediate guitar players, and I decided to try a social media website called “Meetup.com.” It only took a few clicks to find the right community for me—an “acoustic jam” group that welcomed beginners and met once a month at a music store near my city of Sacramento, California. On the Meetup.com site, it said that everyone who showed up for the jam should bring a few songs to share, but I wasn’t sure what kind of music they played, so I just showed up at the next meet-up with my guitar and the basic look you need to become a guitar legend: two days of facial hair stubble, black t-shirt, ripped jeans, and a gravelly voice (luckily my throat was sore from shouting the lyrics to the Twenty One Pilots song “Heathens” while playing guitar in my living room the night before).

The first time I played with the group, I felt more like a junior high school band camp dropout then the next Jimi Hendrix. I had trouble keeping up with the chord changes, and I didn’t know any scales (groups of related notes in the same key that work well together) to solo on lead guitar when it was my turn. I had trouble figuring out the patterns for my strumming hand since no one took the time to explain them before we started playing a new song. The group had some beginners, but I was the least experienced player.

perienced player. It took a few more meet-ups, but pretty soon I figured out how to fit into the group. I learned that they played all kinds of songs, from country to blues to folk to rock music. I learned that they chose songs with simple chords so beginners like me could play along. I learned that they brought print copies of the chords and lyrics of songs to share, and if there were any difficult chords in a song, they included a visual of the chord shape in the handout of chords and lyrics. I started to learn the musician’s vocabulary I needed to be familiar with to function in the group, like beats per measure and octaves and the minor pentatonic scale . I learned that if I was having trouble figuring out the chord changes, I could watch the better guitarists and copy what they were doing. I also got good advice from experienced players, like soaking your fingers in rubbing alcohol every day for ninety seconds to toughen them up so the steel strings wouldn’t hurt as much. I even realized that although I was an inexperienced player, I could contribute to the community by bringing in new songs they hadn’t played before.

Okay, at this point you may be saying to yourself that all of this will make a great biographical movie someday when I become a rock icon (or maybe not), but what does it have to do with becoming a better writer?

You can write in a journal alone in your room, just like you can play guitar just for yourself alone in your room. But most writers, like most musicians, learn their craft from studying experts and becoming part of a community. And most writers, like most musicians, want to be a part of community and communicate with other people who share their goals and interests. Writing teachers and scholars have come up with the concept of “discourse community” to describe a community of people who share the same goals, the same methods of communicating, the same genres, and the same lexis (specialized language).

What Exactly Is a Discourse Community?

John Swales, a scholar in linguistics, says that discourse communities have the following features (which I’m paraphrasing):

- A broadly agreed upon set of common public goals

- Mechanisms of intercommunication among members

- Use of these communication mechanisms to provide information and feedback

- One or more genres that help further the goals of the discourse community

- A specific lexis (specialized language)

- A threshold level of expert members (24-26)

I’ll use my example of the monthly guitar jam group I joined to explain these six aspects of a discourse community.

A Broadly Agreed Set of Common Public Goals

The guitar jam group had shared goals that we all agreed on. In the Meetup.com description of the site, the organizer of the group emphasized that these monthly gatherings were for having fun, enjoying the music, and learning new songs. “Guitar players” or “people who like music” or even “guitarists in Sacramento, California” are not discourse communities. They don’t share the same goals, and they don’t all interact with each other to meet the same goals.

Mechanisms of Intercommunication among Members

The guitar jam group communicated primarily through the Meetup.com site. This is how we recruited new members, shared information about when and where we were playing, and communicated with each other outside of the night of the guitar jam. “People who use Meetup.com” are not a discourse community, because even though they’re using the same method of communication, they don’t all share the same goals and they don’t all regularly interact with each other. But a Meetup.com group like the Sacramento acoustic guitar jam focused on a specific topic with shared goals and a community of members who frequently interact can be considered a discourse community based on Swales’ definition.

Use of These Communication Mechanisms to Provide Information and Feedback

Once I found the guitar jam group on Meetup.com, I wanted information about topics like what skill levels could participate, what kind of music they played, and where and when they met. Once I was at my first guitar jam, the primary information I needed was the chords and lyrics of each song, so the handouts with chords and lyrics were a key means of providing critical information to community members. Communication mechanisms in discourse communities can be emails, text messages, social media tools, print texts, memes, oral presentations, and so on. One reason that Swales uses the term “discourse” instead of “writing” is that the term “discourse” can mean any type of communication, from talking to writing to music to images to multimedia.

One or More Genres That Help Further the Goals of the Discourse Community

One of the most common ways discourse communities share information and meet their goals is through genres. To help explain the concept of genre, I’ll use music since I’ve been talking about playing guitar and music is probably an example you can relate to. Obviously there are many types of music, from rap to country to reggae to heavy metal. Each of these types of music is considered a genre, in part because the music has shared features, from the style of the music to the subject of the lyrics to the lexis. For example, most rap has a steady bass beat, most rappers use spoken word rather singing, and rap lyrics usually draw on a lexis associated with young people. But a genre is much more than a set of features. Genres arise out of social purposes, and they’re a form of social action within discourse communities. The rap battles of today have historical roots in African oral contests, and modern rap music can only be understood in the context of hip hop culture, which includes break dancing and street art. Rap also has social purposes, including resisting social oppression and telling the truth about social conditions that aren’t always reported on by news outlets. Like all genres, rap is not just a formula but a tool for social action.

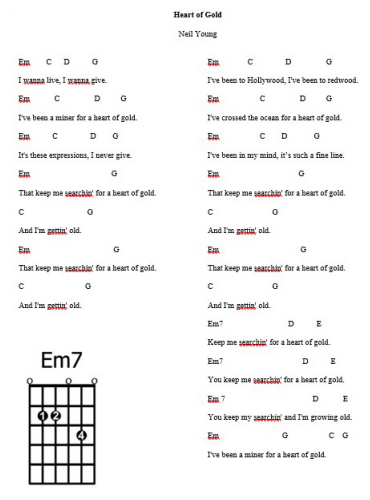

The guitar jam group used two primary genres to meet the goals of the community. The Meetup.com site was one important genre that was critical in the formation of the group and to help it recruit new members. It was also the genre that delivered information to the members about what the community was about and where and when the community would be meeting. The other important genre to the guitar jam group were the handouts with song chords and lyrics. I’m sharing an example of a song I brought to the group to show you what this genre looks like.

This genre of the chord and lyrics sheet was needed to make sure everyone could play along and follow the singer. The conventions of this genre—the “norms”—weren’t just arbitrary rules or formulas. As with all genres, the conventions developed because of the social action of the genre. The sheets included lyrics so that we could all sing along and make sure we knew when to change chords. The sheets included visuals of unusual chords, like the Em7 chord (E minor seventh) in my example, because there were some beginner guitarists who were a part of the community. If the community members were all expert guitarists, then the inclusion of chord shapes would never have become a convention. A great resource to learn more about the concept of genre is the essay “Navigating Genres” by Kerry Dirk in volume 1 of Writing Spaces .

A Specific Lexis (Specialized Language)

To anyone who wasn’t a musician, our guitar meet-ups might have sounded like we were communicating in a foreign language. We talked about the root note of scale, a 1/4/5 chord progression, putting a capo on different frets, whether to play solos in a major or minor scale, double drop D tuning, and so on. If someone couldn’t quickly identify what key their song was in or how many beats per measure the strumming pattern required, they wouldn’t be able to communicate effectively with the community members. We didn’t use this language to show off or to try to discourage outsiders from joining our group. We needed these specialized terms—this musician’s lexis—to make sure we were all playing together effectively.

A Threshold Level of Expert Members

If everyone in the guitar jam was at my beginner level when I first joined the group, we wouldn’t have been very successful. I relied on more experienced players to figure out strumming patterns and chord changes, and I learned to improve my solos by watching other players use various techniques in their soloing. The most experienced players also helped educate everyone on the conventions of the group (the “norms” of how the group interacted). These conventions included everyone playing in the same key, everyone taking turns playing solo lead guitar, and everyone bringing songs to play. But discourse community conventions aren’t always just about maintaining group harmony. In most discourse communities, new members can also expand the knowledge and genres of the community. For example, I shared songs that no one had brought before, and that expanded the community’s base of knowledge.

Why the Concept of Discourse Communities Matters for College Writing

When I was an undergraduate at the University of Florida, I didn’t understand that each academic discipline I took courses in to complete the requirements of my degree (history, philosophy, biology, math, political science, sociology, English) was a different discourse community. Each of these academic fields had their own goals, their own genres, their own writing conventions, their own formats for citing sources, and their own expectations for writing style. I thought each of the teachers I encountered in my undergraduate career just had their own personal preferences that all felt pretty random to me. I didn’t understand that each teacher was trying to act as a representative of the discourse community of their field. I was a new member of their discourse communities, and they were introducing me to the genres and conventions of their disciplines. Unfortunately, teachers are so used to the conventions of their discourse communities that they sometimes don’t explain to students the reasons behind the writing conventions of their discourse communities.

It wasn’t until I studied research about college writing while I was in graduate school that I learned about genres and discourse communities, and by the time I was doing my dissertation for my PhD, I got so interested in studying college writing that I did a national study of college teachers’ writing assignments and syllabi. Believe it or not, I analyzed the genres and discourse communities of over 2,000 college writing assignments in my book Assignments Across the Curriculum . To show you why the idea of discourse community is so important to college writing, I’m going to share with you some information from one of the academic disciplines I studied: history. First I want to share with you an excerpt from a history course writing assignment from my study. As you read it over, think about what it tells you about the conventions of the discourse community of history.

Documentary Analysis

This assignment requires you to play the detective, combing textual sources for clues and evidence to form a reconstruction of past events. If you took A.P. history courses in high school, you may recall doing similar document-based questions (DBQs).

In a tight, well-argued essay of two to four pages, identify and assess the historical significance of the documents in ONE of the four sets I have given you.

You bring to this assignment a limited body of outside knowledge gained from our readings, class discussions, and videos. Make the most of this contextual knowledge when interpreting your sources: you may, for example, refer to one of the document from another set if it sheds light on the items in your own.

Questions to Consider When Planning Your Essay

- What do the documents reveal about the author and his audience?

- Why were they written?

- What can you discern about the author’s motivation and tone? Is the tone revealing?

- Does the genre make a difference in your interpretation?

- How do the documents fit into both their immediate and their greater historical contexts?

- Do your documents support or contradict what other sources (video, readings) have told you?

- Do the documents reveal a change that occurred over a period of time?

- Is there a contrast between documents within your set? If so, how do you account for it?

- Do they shed light on a historical event, problem, or period? How do they fit into the “big picture”?

- What incidental information can you glean from them by reading carefully? Such information is important for constructing a narrative of the past; our medieval authors almost always tell us more than they intended to.

- What is not said, but implied?

- What is left out? (As a historian, you should always look for what is not said, and ask yourself what the omission signifies.)

- Taken together, do the documents reveal anything significant about the period in question? (Melzer 3-4)

This assignment doesn’t just represent the specific preferences of one random teacher. It’s a common history genre (the documentary analysis) that helps introduce students to the ways of thinking and the communication conventions of the discourse community of historians. This genre reveals that historians look for textual clues to reconstruct past events and that historians bring their own knowledge to bear when they analyze texts and interpret history (historians are not entirely “objective” or “neutral”). In this documentary analysis genre, the instructor emphasizes that historians are always looking for what is not said but instead is implied. This instructor is using an important genre of history to introduce students to the ways of analyzing and thinking in the discourse community of historians.

Let’s look at another history course in my research. I’m sharing with you an excerpt from the syllabus of a history of the American West course. This part of the syllabus gives students an overview of the purpose of the writing projects in the class. As you read this overview, think about the ways this instructor is portraying the discourse community of historians.

A300: History of the American West

A300 is designed to allow students to explore the history of the American West on a personal level with an eye toward expanding their knowledge of various western themes, from exploration to the Indian Wars, to the impact of global capitalism and the emergence of the environmental movement. But students will also learn about the craft of history, including the tools used by practitioners, how to weigh competing evidence , and how to build a convincing argument about the past.

At the end of this course students should understand that history is socially interpreted, and that the past has always been used as an important means for understanding the present. Old family photos, a grandparent’s memories, even family reunions allow people to understand their lives through an appreciation of the past. These events and artifacts remind us that history is a dynamic and interpretive field of study that requires far more than rote memorization. Historians balance their knowledge of primary sources (diaries, letters, artifacts, and other documents from the period under study) with later interpretations of these people, places, and events (in the form of scholarly monographs and articles) known as secondary sources . Through the evaluation and discussion of these different interpretations historians come to a socially negotiated understanding of historical figures and events.

Individual Projects

More generally, your papers should:

- Empathize with the person, place, or event you are writing about. The goal here is to use your understanding of the primary and secondary sources you have read to “become” that person–i.e. to appreciate their perspectives on the time or event under study. In essence, students should demonstrate an appreciation of that time within its context.

- Second, students should be able to present the past in terms of its relevance to contemporary issues. What do their individual projects tell us about the present? For example, what does the treatment of Native Americans, Mexican Americans, and Asian Americans in the West tell us about the problem of race in the United States today?

- Third, in developing their individual and group projects, students should demonstrate that they have researched and located primary and secondary sources. Through this process they will develop the skills of a historian, and present an interpretation of the past that is credible to their peers and instructors.

Just like the history instructor who gave students the documentary analysis assignment, this history of the American West instructor emphasizes that the discourse community of historians doesn’t focus on just memorizing facts, but on analyzing and interpreting competing evidence. Both the documentary analysis assignment and the information from the history of the American West syllabus show that an important shared goal of the discourse community of historians is socially constructing the past using evidence from different types of artifacts, from texts to photos to interviews with people who have lived through important historical events. The discourse community goals and conventions of the different academic disciplines you encounter as an undergraduate shape everything about writing: which genres are most important, what counts as evidence, how arguments are constructed, and what style is most appropriate and effective.

The history of the American West course is a good example of the ways that discourse community goals and values can change over time. It wasn’t that long ago that American historians who wrote about the West operated on the philosophy of “manifest destiny.” Most early historians of the American West assumed that the American colonizers had the right to take land from indigenous tribes—that it was the white European’s “destiny” to colonize the American West. The evidence early historians used in their writing and the ways they interpreted that evidence relied on the perspectives of the “settlers,” and the perspectives of the indigenous people were ignored by historians. The concept of manifest destiny has been strongly critiqued by modern historians, and one of the primary goals of most modern historians who write about the American West is to recover the perspectives and stories of the indigenous peoples as well as to continue to work for social justice for Native Americans by showing how historical injustices continue in different forms to the present day. Native American historians are now retelling history from the perspective of indigenous people, using indigenous research methods that are often much different than the traditional research methods of historians of the American West. Discourse community norms can silence and marginalize people, but discourse communities can also be transformed by new members who challenge the goals and assumptions and research methods and genre conventions of the community.

Discourse Communities from School to Work and Beyond

Understanding what a discourse community is and the ways that genres perform social actions in discourse communities can help you better understand where your college teachers are coming from in their writing assignments and also help you understand why there are different writing expectations and genres for different classes in different fields. Researchers who study college writing have discovered that most students struggle with writing when they first enter the discourse community of their chosen major, just like I struggled when I first joined the acoustic guitar jam group. When you graduate college and start your first job, you will probably also find yourself struggling a bit with trying to learn the writing conventions of the discourse community of your workplace. Knowing how discourse communities work will not only help you as you navigate the writing assigned in different general education courses and the specialized writing of your chosen major, but it will also help you in your life after college. Whether you work as a scientist in a lab or a lawyer for a firm or a nurse in a hospital, you will need to become a member of a discourse community. You’ll need to learn to communicate effectively using the genres of the discourse community of your workplace, and this might mean asking questions of more experienced discourse community members, analyzing models of the types of genres you’re expected to use to communicate, and thinking about the most effective style, tone, format, and structure for your audience and purpose. Some workplaces have guidelines for how to write in the genres of the discourse community, and some workplaces will initiate you to their genres by trial and error. But hopefully now that you’ve read this essay, you’ll have a better idea of what kinds of questions to ask to help you become an effective communicator in a new discourse community. I’ll end this essay with a list of questions you can ask yourself whenever you’re entering a new discourse community and learning the genres of the community:

- What are the goals of the discourse community?

- What are the most important genres community members use to achieve these goals?

- Who are the most experienced communicators in the discourse community?

- Where can I find models of the kinds of genres used by the discourse community?

- Who are the different audiences the discourse community communicates with, and how can I adjust my writing for these different audiences?

- What conventions of format, organization, and style does the discourse community value?

- What specialized vocabulary (lexis) do I need to know to communicate effectively with discourse community insiders?

- How does the discourse community make arguments, and what types of evidence are valued?

- Do the conventions of the discourse community silence any members or force any members to conform to the community in ways that make them uncomfortable?

- What can I add to the discourse community?

Works Cited

Dirk, Kerry. “Navigating Genres.” Writing Spaces , vol. 1, edited by Charles Lowe and Pavel Zemliansky, Parlor Press, 2010, pp. 249–262.

Guitar Hero . Harmonics, 2005.

Meetup.com . WeWork Companies Inc., 2019. www.meetup.com.

Melzer, Daniel. Assignments Across the Curriculum: A National Study of College Writing . Logan, UT: Utah State UP, 2014.

Swales, John. Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings . Boston: Cambridge UP, 1990.

Twenty One Pilots. “Heathens.” Suicide Squad: The Album , Atlantic Records, 2016.

Young, Neil. “Heart of Gold.” Harvest , Reprise Records, 1972.

Teacher Resources for Understanding Discourse Communities by Dan Melzer

Overview and teaching strategies.

This essay can be taught in conjunction with teaching students about the concept of genre and could be paired with Kerry Dirk’s essay “Navigating Genres” in Writing Spaces , volume 1. I find that it works best to scaffold the concept of discourse community by moving students from reflecting on the formulaic writing they have learned in the past, like the five-paragraph theme or the Shaffer method, to introducing them to the concept of genre and how genres are not formulas or formats but forms of social action, and then to helping students understand that genres usually operate within discourse communities. Most of my students are unfamiliar with the concept of discourse community, and I find that it is helpful to relate this concept to discourse communities students are already members of, like online gaming groups, college clubs, or jobs students are working or have worked. I sometimes teach the concept of discourse community as part of a research project where students investigate the genres and communication conventions of a discourse community they want to join or are already a member of. In this project students conduct primary and secondary research and rhetorically analyze examples of the primary genres of the discourse community. The primary research might involve doing an interview or interviews with discourse community members, conducting a survey of discourse community members, or reflecting on participant-observer research.

Inevitably, some students have trouble differentiating between a discourse community and a group of people who share similar characteristics. Students may assert that “college students” or “Facebook users” or “teenage women” are a discourse community. It is useful to apply Swales’ criteria to broader groups that students imagine are discourse communities and then try to narrow down these groups until students have hit upon an actual discourse community (for example, narrowing from “Facebook users” to the Black Lives Matter Sacramento Facebook group). In the essay, I tried to address this issue with specific examples of groups that Swales would not classify as a discourse community.

Teaching students about academic discourse communities is a challenging task. Researchers have found that there are broad expectations for writing that seem to hold true across academic discourse communities, such as the ability to make logical arguments and support those arguments with credible evidence, the ability to use academic vocabulary and write in a formal style, and the ability to carefully edit for grammar, syntax, and citation format. But research has also shown that not only do different academic fields have vastly different definitions of how arguments are made, what counts as evidence, and what genres, styles, and formats are valued, but even similar types of courses within the same discipline may have very different discourse community expectations depending on the instructor, department, and institution. In teaching students about the concept of discourse community, I want students to leave my class understanding that: a) there is no such thing as a formula or set of rules for “academic discourse”; b) each course in each field of study they take in college will require them to write in the context of a different set of discourse community expectations; and c) discourse communities can both pass down community knowledge to new members and sometimes marginalize or silence members. What I hope students take away from reading this essay is a more rhetorically sophisticated and flexible sense of the community contexts of the writing they do both in and outside of school.

- The author begins the essay discussing a discourse community he has recently become a member of. Think of a discourse community that you recently joined and describe how it meets Swales’ criteria for a discourse community.

- Choose a college class you’ve taken or are taking and describe the goals and expectations for writing of the discourse community the class represents. In small groups, compare the class discourse community you described with two of your peers’ courses. What are some of the differences in the goals and expectations for writing?

- Using Swales’ criteria for a discourse community, consider whether the following are discourse communities and why or why not: a) students at your college; b) a fraternity or sorority; c) fans of soccer; d) a high school debate team.

- The author of this essay argues that discourse communities use genres for social actions. Consider your major or a field you would like to work in after you graduate. What are some of the most important genres of that discourse community? In what ways do these genres perform social actions for members of the discourse community?

The following are activities that can provide scaffolding for a discourse community analysis project. To view example student discourse community analysis projects from the first-year composition program that I direct at the University of California, Davis, see our online student writing journal at fycjournal.ucdavis.edu .

Introducing the Concept of Discourse Community

To introduce students to the concept of discourse community, I like to start with discourse communities they can relate to or that they themselves are members of. A favorite example for my students is the This American Life podcast episode that explores the Instagram habits of teenage girls, which can be found at https://www.thisamericanlife.org/573/status-update . Other examples students can personally connect to include Facebook groups, groups on the popular social media site Reddit, fan clubs of musical artists or sports teams, and campus student special interest groups. Once we’ve discussed a few examples of discourse communities they can relate to on a personal level, I ask them to list some of the discourse communities they belong to and we apply Swales’ criteria to a few of these examples as a class.

Genre Analysis

One goal of my discourse community analysis project is to help students see the relationships between genres and the broader community contexts that genres operate in. However, thinking of writing in terms of genre and discourse community is a new approach for most of my students, and I provide them with heuristic questions they can use to analyze the primary genres of the discourse community they are focusing on in their projects. These questions include:

- Who is the audience(s) for the genre, and how does audience shape the genre?

- What social actions does the genre achieve for the discourse community?

- What are the conventions of the genre?

- How much flexibility do authors have to vary the conventions of the genre?

- Have the conventions of the genre changed over time? In what ways and why?

- To what extent does the genre empower members of the discourse community to speak, and to what extent does the genre marginalize or silence members of the discourse community?

- Where can a new discourse community member find models of the genre?

Research Questions about the Discourse Community

You could choose to have the focus of students’ discourse community projects be as simple as arguing that the discourse community they chose meets Swales’ criteria and explaining why. If you want students to dig a little deeper, you can ask them to come up with research questions about the discourse community they are analyzing. For example, students can ask questions about how the genres of the discourse community achieve the goals of the community, or how the writing conventions of the discourse community have changed over time and why they have changed, or how new members are initiated to the discourse community and the extent to which that initiation is effective. Some of my students are used to being assigned research papers in school that ask them to take a side on a pro/ con issue and develop a simplistic thesis statement that argues for that position. In the discourse community analysis project, I push them to think of research as more sophisticated than just taking a position and forming a simplistic thesis statement. I want them to use primary and secondary research to explore complex research questions and decide which aspects of their data and their analysis are the most interesting and useful to report on in their projects.

- This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) and are subject to the Writing Spaces Terms of Use. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ , email [email protected] , or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. To view the Writing Spaces Terms of Use, visit http://writingspaces.org/terms-of-use . ↵

Understanding Discourse Communities Copyright © 2020 by Dan Melzer is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- University of Memphis Libraries

- Research Guides

ENGL 1010: English Composition 1010

Discourse communities.

- Literacy Narrative

- Autoethnography

- Secondary Sources

- Citations and Writing Help

- Resources for Instructors

- Dual Enrollment

Get Help at McWherter Library

Ned R. McWherter Library 3785 Norriswood Ave., Memphis, TN 38152

Ask a Librarian

Hours / Events

What is a discourse community?

Collection of people or groups that work towards a common goal through communication. This group develops a process for communication, a unique vocabulary of jargon, and a power structure tied to the source of their community. John Swales maintains that genres both “belong” to discourse communities and help to define them (Borg, 2003). He outlined six characteristics of discourse communities: 1) common public goals; 2) methods of communicating among members; 3) participatory communication methods; 4) genres that define the group; 5) a lexis; and 6) a standard of knowledge needed for membership (Swales, 471-473).

- Genre Across Borders

What people are in discourse communities?

Any group that works meets Swales's criteria share a discourse community. Basketball teams, Taco Bell employees, librarians, urban planners, teachers, runners, superfans of Beyonce - all share unique vocabulary and create individual discourse communities.

You can be in more than one discourse community simultaneously.

For example, a teacher who is an avid kickball player in a kickball league and is also involved in grassroots voter-turnout organization is part of (at least) three discourse communities:

- the community of teachers that shares the discourse of learning and pedagogy (grading rubrics, classroom engagement)

- the kickball league, which shares the discourse of the sport (the rules of the game, kicking strategy)

- the voter outreach community, which shares the discourse of grassroots activism (canvassing, polling, lobbying)

How to Explore Discourse Communities

You don't need academic articles to explore discourse communities. You just need to be a little creative.

Ways to Find Communication Among Discourse Communities

- For example, attend a meeting of your community.

- Interview a member or group of members of a particular community to ask about their lexicon, shared goals, and power structure.

- Message boards

- Official communication, such as media releases

- Publicly available listservs

- Social media such as Facebook or Twitter conversations

- Community publications like newsletters, magazines, or trade publications

- Try Reddit. There's a community for everything.

Best Practices in Primary Field Research

- What is Primary Research and How do I get Started? Primary research is any type of research that you collect yourself. Examples include surveys, interviews, observations, and ethnographic research. A good researcher knows how to use both primary and secondary sources in their writing and to integrate them in a cohesive fashion.

- Library of Congress: Getting Started with Primary Sources Citing a variety of primary research sources in MLA.

- How to Cite a Tweet in MLA

- How to Cite an Email Message in MLA

- How to cite an interview in a bibliography using MLA

- << Previous: Literacy Narrative

- Next: Autoethnography >>

- Last Updated: Apr 11, 2024 3:44 PM

- URL: https://libguides.memphis.edu/engl1010

English Composition 2089: Researching Discourse

- Get Help Here!

What Is Discourse?

Discourse analysis, discourse communities, examples of discourse communities, tips on choosing a discourse community to analyze.

- Discourse Community Analysis/Ethnography

- Analyzing Multiple Discourses

- Research Refresher--Finding articles, books, and more!

- How Do I Find Different Genres?

- How Do I Find Images and Media?

- Popular Music Criticism

- Citing Your Sources

- Recast Content in a Different Genre

Essentially, discourse is an act of communication between a composer and audience for a particular purpose. This communication can take a variety of forms.

Here are some common forms of discourse:

- newspaper article

- scholarly journal article

- radio or TV broadcast

- published report

However, also think beyond textual discourses, for example:

- advertisement

- emojis or memes

- architecture or design, e.g. 9/11 Memorial

- clothing styles

You are encouraged to think expansively about what counts as a discourse so that your work in English 2089 reflects the diversity and richness of 21st century discourses and communication practices.

When considering any form of discourse, in addition to understanding WHAT is being said, also focus on WHO is creating the text, WHY they are doing so, and HOW the resulting discourse impacts or has impacted the issue.

Ask yourself the following questions to ANALYZE discourse:

- Who is the intended audience?

- What is the purpose of the information presented? (inform, persuade, entertain)

- What types of evidence are used to support the claims of the information?

- How is information shaped by a particular genre? (Consider the audience, layout, space, style, conventions, etc).

- How literate, biased, and/or credible are those producing this discourse?

- To what degree is the discourse mainstream (understood by the broad audience) or considered non-traditional or even avant-garde?

Analyzing the discourse on an issue is different from arguing a position on an issue. See the chart below for an example of these differences:

A discourse community is a "social group that communicates at least in part via written texts and shares common goals, values, and writing standards, a specialized vocabulary, and specialized genres." Anne Beaufort, College Writing and Beyond .

Different discourse communities will often discuss the same topic in very different ways. The concept map below shows some discourse communities involved in conversations related to obesity.

Professional:

- emergency room nurses

- prison guards

- political aides

Be careful to sufficiently narrow your focus so you are not trying to analyze a community with millions of members who have vastly different discourse practices (i.e. “scientists” or “business people”)

- activist organizations (PETA, NRA, Sierra Club)

- a specific ethnic group (Amish, Native Americans living on reservations, Cajun)

- a campus club or organization

- charity organizations

Be sensitive to stereotypes if you analyze a community associated with race, religion, etc.

- the PTA or similar school groups

- political action groups

- fan groups (Trekkies, Potterites, the BeyHive)

- Civil War re-enactors

- game clubs (Dungeons & Dragons, Magic Cards, etc.)

- Choose communities that are in conversation on a particular topic or problem.

- Select key communities that represent various perspectives on a topic.

- Choose an organized or connected community that has a common purpose; for example, the animal rights group PETA.

- Be specific: instead of Cincinnati Reds fans, choose members of the RedsZone or the Rosie Reds.

- Focus on the discourse of an entire community, not on a specific person.

- << Previous: Get Help Here!

- Next: Discourse Community Analysis/Ethnography >>

- Last Updated: Mar 11, 2024 11:30 AM

- URL: https://guides.libraries.uc.edu/2089

University of Cincinnati Libraries

PO Box 210033 Cincinnati, Ohio 45221-0033

Phone: 513-556-1424

Contact Us | Staff Directory

University of Cincinnati

Alerts | Clery and HEOA Notice | Notice of Non-Discrimination | eAccessibility Concern | Privacy Statement | Copyright Information

© 2021 University of Cincinnati

How to Write the Community Essay – Guide with Examples (2023-24)

September 6, 2023

Students applying to college this year will inevitably confront the community essay. In fact, most students will end up responding to several community essay prompts for different schools. For this reason, you should know more than simply how to approach the community essay as a genre. Rather, you will want to learn how to decipher the nuances of each particular prompt, in order to adapt your response appropriately. In this article, we’ll show you how to do just that, through several community essay examples. These examples will also demonstrate how to avoid cliché and make the community essay authentically and convincingly your own.

Emphasis on Community

Do keep in mind that inherent in the word “community” is the idea of multiple people. The personal statement already provides you with a chance to tell the college admissions committee about yourself as an individual. The community essay, however, suggests that you depict yourself among others. You can use this opportunity to your advantage by showing off interpersonal skills, for example. Or, perhaps you wish to relate a moment that forged important relationships. This in turn will indicate what kind of connections you’ll make in the classroom with college peers and professors.

Apart from comprising numerous people, a community can appear in many shapes and sizes. It could be as small as a volleyball team, or as large as a diaspora. It could fill a town soup kitchen, or spread across five boroughs. In fact, due to the internet, certain communities today don’t even require a physical place to congregate. Communities can form around a shared identity, shared place, shared hobby, shared ideology, or shared call to action. They can even arise due to a shared yet unforeseen circumstance.

What is the Community Essay All About?

In a nutshell, the community essay should exhibit three things:

- An aspect of yourself, 2. in the context of a community you belonged to, and 3. how this experience may shape your contribution to the community you’ll join in college.

It may look like a fairly simple equation: 1 + 2 = 3. However, each college will word their community essay prompt differently, so it’s important to look out for additional variables. One college may use the community essay as a way to glimpse your core values. Another may use the essay to understand how you would add to diversity on campus. Some may let you decide in which direction to take it—and there are many ways to go!

To get a better idea of how the prompts differ, let’s take a look at some real community essay prompts from the current admission cycle.

Sample 2023-2024 Community Essay Prompts

1) brown university.

“Students entering Brown often find that making their home on College Hill naturally invites reflection on where they came from. Share how an aspect of your growing up has inspired or challenged you, and what unique contributions this might allow you to make to the Brown community. (200-250 words)”

A close reading of this prompt shows that Brown puts particular emphasis on place. They do this by using the words “home,” “College Hill,” and “where they came from.” Thus, Brown invites writers to think about community through the prism of place. They also emphasize the idea of personal growth or change, through the words “inspired or challenged you.” Therefore, Brown wishes to see how the place you grew up in has affected you. And, they want to know how you in turn will affect their college community.

“NYU was founded on the belief that a student’s identity should not dictate the ability for them to access higher education. That sense of opportunity for all students, of all backgrounds, remains a part of who we are today and a critical part of what makes us a world-class university. Our community embraces diversity, in all its forms, as a cornerstone of the NYU experience.

We would like to better understand how your experiences would help us to shape and grow our diverse community. Please respond in 250 words or less.”

Here, NYU places an emphasis on students’ “identity,” “backgrounds,” and “diversity,” rather than any physical place. (For some students, place may be tied up in those ideas.) Furthermore, while NYU doesn’t ask specifically how identity has changed the essay writer, they do ask about your “experience.” Take this to mean that you can still recount a specific moment, or several moments, that work to portray your particular background. You should also try to link your story with NYU’s values of inclusivity and opportunity.

3) University of Washington

“Our families and communities often define us and our individual worlds. Community might refer to your cultural group, extended family, religious group, neighborhood or school, sports team or club, co-workers, etc. Describe the world you come from and how you, as a product of it, might add to the diversity of the UW. (300 words max) Tip: Keep in mind that the UW strives to create a community of students richly diverse in cultural backgrounds, experiences, values and viewpoints.”

UW ’s community essay prompt may look the most approachable, for they help define the idea of community. You’ll notice that most of their examples (“families,” “cultural group, extended family, religious group, neighborhood”…) place an emphasis on people. This may clue you in on their desire to see the relationships you’ve made. At the same time, UW uses the words “individual” and “richly diverse.” They, like NYU, wish to see how you fit in and stand out, in order to boost campus diversity.

Writing Your First Community Essay

Begin by picking which community essay you’ll write first. (For practical reasons, you’ll probably want to go with whichever one is due earliest.) Spend time doing a close reading of the prompt, as we’ve done above. Underline key words. Try to interpret exactly what the prompt is asking through these keywords.

Next, brainstorm. I recommend doing this on a blank piece of paper with a pencil. Across the top, make a row of headings. These might be the communities you’re a part of, or the components that make up your identity. Then, jot down descriptive words underneath in each column—whatever comes to you. These words may invoke people and experiences you had with them, feelings, moments of growth, lessons learned, values developed, etc. Now, narrow in on the idea that offers the richest material and that corresponds fully with the prompt.

Lastly, write! You’ll definitely want to describe real moments, in vivid detail. This will keep your essay original, and help you avoid cliché. However, you’ll need to summarize the experience and answer the prompt succinctly, so don’t stray too far into storytelling mode.

How To Adapt Your Community Essay

Once your first essay is complete, you’ll need to adapt it to the other colleges involving community essays on your list. Again, you’ll want to turn to the prompt for a close reading, and recognize what makes this prompt different from the last. For example, let’s say you’ve written your essay for UW about belonging to your swim team, and how the sports dynamics shaped you. Adapting that essay to Brown’s prompt could involve more of a focus on place. You may ask yourself, how was my swim team in Alaska different than the swim teams we competed against in other states?

Once you’ve adapted the content, you’ll also want to adapt the wording to mimic the prompt. For example, let’s say your UW essay states, “Thinking back to my years in the pool…” As you adapt this essay to Brown’s prompt, you may notice that Brown uses the word “reflection.” Therefore, you might change this sentence to “Reflecting back on my years in the pool…” While this change is minute, it cleverly signals to the reader that you’ve paid attention to the prompt, and are giving that school your full attention.

What to Avoid When Writing the Community Essay

- Avoid cliché. Some students worry that their idea is cliché, or worse, that their background or identity is cliché. However, what makes an essay cliché is not the content, but the way the content is conveyed. This is where your voice and your descriptions become essential.

- Avoid giving too many examples. Stick to one community, and one or two anecdotes arising from that community that allow you to answer the prompt fully.

- Don’t exaggerate or twist facts. Sometimes students feel they must make themselves sound more “diverse” than they feel they are. Luckily, diversity is not a feeling. Likewise, diversity does not simply refer to one’s heritage. If the prompt is asking about your identity or background, you can show the originality of your experiences through your actions and your thinking.

Community Essay Examples and Analysis

Brown university community essay example.

I used to hate the NYC subway. I’ve taken it since I was six, going up and down Manhattan, to and from school. By high school, it was a daily nightmare. Spending so much time underground, underneath fluorescent lighting, squashed inside a rickety, rocking train car among strangers, some of whom wanted to talk about conspiracy theories, others who had bedbugs or B.O., or who manspread across two seats, or bickered—it wore me out. The challenge of going anywhere seemed absurd. I dreaded the claustrophobia and disgruntlement.

Yet the subway also inspired my understanding of community. I will never forget the morning I saw a man, several seats away, slide out of his seat and hit the floor. The thump shocked everyone to attention. What we noticed: he appeared drunk, possibly homeless. I was digesting this when a second man got up and, through a sort of awkward embrace, heaved the first man back into his seat. The rest of us had stuck to subway social codes: don’t step out of line. Yet this second man’s silent actions spoke loudly. They said, “I care.”

That day I realized I belong to a group of strangers. What holds us together is our transience, our vulnerabilities, and a willingness to assist. This community is not perfect but one in motion, a perpetual work-in-progress. Now I make it my aim to hold others up. I plan to contribute to the Brown community by helping fellow students and strangers in moments of precariousness.

Brown University Community Essay Example Analysis

Here the student finds an original way to write about where they come from. The subway is not their home, yet it remains integral to ideas of belonging. The student shows how a community can be built between strangers, in their responsibility toward each other. The student succeeds at incorporating key words from the prompt (“challenge,” “inspired” “Brown community,” “contribute”) into their community essay.

UW Community Essay Example

I grew up in Hawaii, a world bound by water and rich in diversity. In school we learned that this sacred land was invaded, first by Captain Cook, then by missionaries, whalers, traders, plantation owners, and the U.S. government. My parents became part of this problematic takeover when they moved here in the 90s. The first community we knew was our church congregation. At the beginning of mass, we shook hands with our neighbors. We held hands again when we sang the Lord’s Prayer. I didn’t realize our church wasn’t “normal” until our diocese was informed that we had to stop dancing hula and singing Hawaiian hymns. The order came from the Pope himself.

Eventually, I lost faith in God and organized institutions. I thought the banning of hula—an ancient and pure form of expression—seemed medieval, ignorant, and unfair, given that the Hawaiian religion had already been stamped out. I felt a lack of community and a distrust for any place in which I might find one. As a postcolonial inhabitant, I could never belong to the Hawaiian culture, no matter how much I valued it. Then, I was shocked to learn that Queen Ka’ahumanu herself had eliminated the Kapu system, a strict code of conduct in which women were inferior to men. Next went the Hawaiian religion. Queen Ka’ahumanu burned all the temples before turning to Christianity, hoping this religion would offer better opportunities for her people.

Community Essay (Continued)

I’m not sure what to make of this history. Should I view Queen Ka’ahumanu as a feminist hero, or another failure in her islands’ tragedy? Nothing is black and white about her story, but she did what she thought was beneficial to her people, regardless of tradition. From her story, I’ve learned to accept complexity. I can disagree with institutionalized religion while still believing in my neighbors. I am a product of this place and their presence. At UW, I plan to add to campus diversity through my experience, knowing that diversity comes with contradictions and complications, all of which should be approached with an open and informed mind.

UW Community Essay Example Analysis

This student also manages to weave in words from the prompt (“family,” “community,” “world,” “product of it,” “add to the diversity,” etc.). Moreover, the student picks one of the examples of community mentioned in the prompt, (namely, a religious group,) and deepens their answer by addressing the complexity inherent in the community they’ve been involved in. While the student displays an inner turmoil about their identity and participation, they find a way to show how they’d contribute to an open-minded campus through their values and intellectual rigor.

What’s Next

For more on supplemental essays and essay writing guides, check out the following articles:

- How to Write the Why This Major Essay + Example

- How to Write the Overcoming Challenges Essay + Example

- How to Start a College Essay – 12 Techniques and Tips

- College Essay

Kaylen Baker

With a BA in Literary Studies from Middlebury College, an MFA in Fiction from Columbia University, and a Master’s in Translation from Université Paris 8 Vincennes-Saint-Denis, Kaylen has been working with students on their writing for over five years. Previously, Kaylen taught a fiction course for high school students as part of Columbia Artists/Teachers, and served as an English Language Assistant for the French National Department of Education. Kaylen is an experienced writer/translator whose work has been featured in Los Angeles Review, Hybrid, San Francisco Bay Guardian, France Today, and Honolulu Weekly, among others.

- 2-Year Colleges

- Application Strategies

- Best Colleges by Major

- Best Colleges by State

- Big Picture

- Career & Personality Assessment

- College Search/Knowledge

- College Success

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Dental School Admissions

- Extracurricular Activities

- Graduate School Admissions

- High School Success

- High Schools

- Law School Admissions

- Medical School Admissions

- Navigating the Admissions Process

- Online Learning

- Private High School Spotlight

- Summer Program Spotlight

- Summer Programs

- Test Prep Provider Spotlight

“Innovative and invaluable…use this book as your college lifeline.”

— Lynn O'Shaughnessy

Nationally Recognized College Expert

College Planning in Your Inbox

Join our information-packed monthly newsletter.

I am a... Student Student Parent Counselor Educator Other First Name Last Name Email Address Zip Code Area of Interest Business Computer Science Engineering Fine/Performing Arts Humanities Mathematics STEM Pre-Med Psychology Social Studies/Sciences Submit

Writing for an Audience: Discourse Communities

- First Online: 21 November 2023

Cite this chapter

- Mary Renck Jalongo 3

Part of the book series: Springer Texts in Education ((SPTE))

232 Accesses