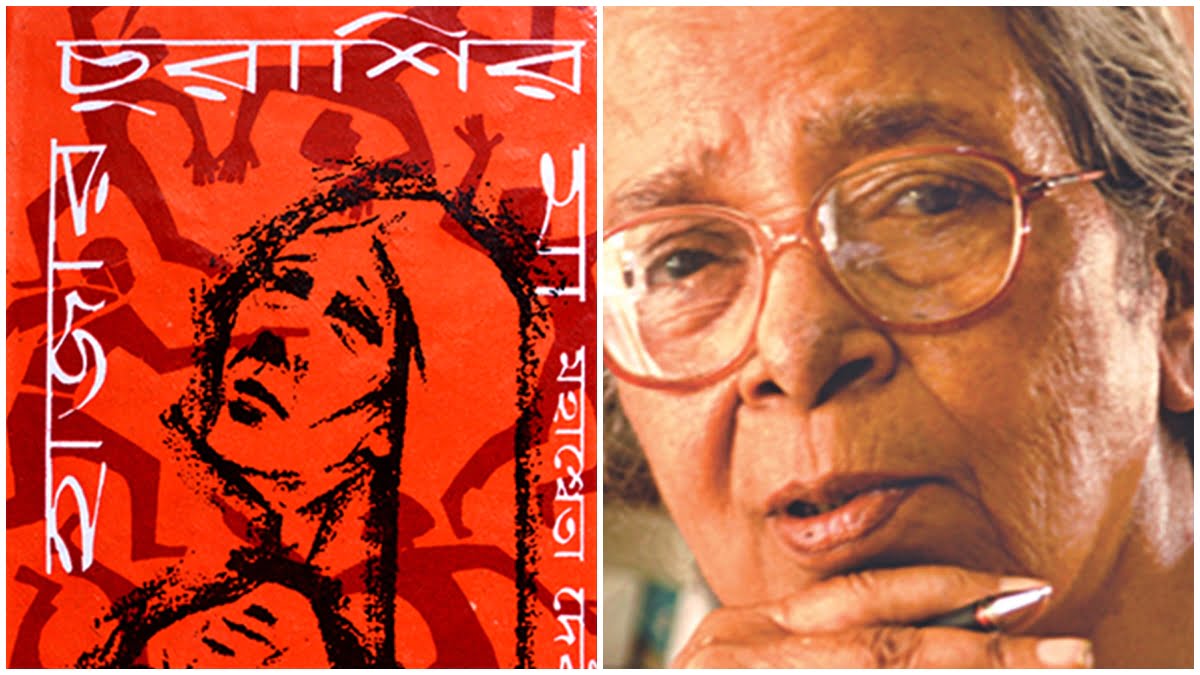

Reading Mahasweta Devi’s Hajar Churashir Maa: Mothers, Memories & Movement

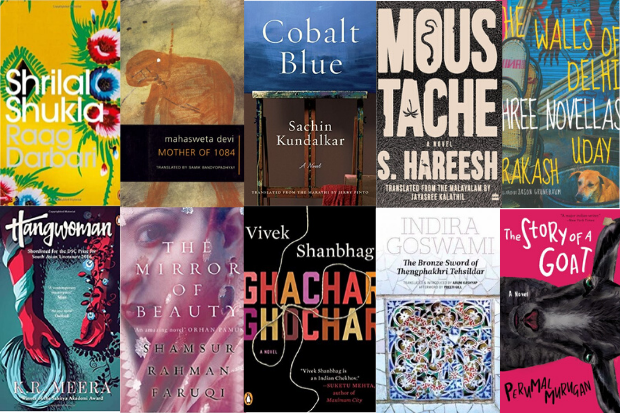

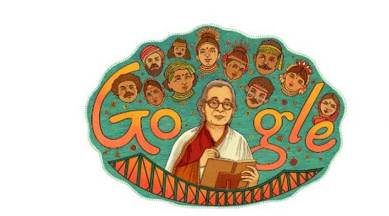

The society that we inhabit today is a site of make-beliefs and failing magic realistic monotones. Antidotes to these fault lines aren’t available yet, hence the illusions are continuing to loom large on the psyche of human minds. This, coupled with state-sponsored misnomers, is putting the human conscience at stake. But does the garb of normalcy, the Foucauldian “order” make one disenfranchise a memory, a disturbing one, which is dear to her/him? Memory can be manufactured, perfected, and dehumanised even. But what about the repertoires within the mothers’ minds who earthed the seeds of “unrest” in the face of a deathly calm? Mahasweta Devi, in Hajar Churashir Maa (Mother of 1084) , her 1974 Bengali novel, provides an alternative plane where these are never forgotten but nurtured like raw wounds.

Memory can be manufactured, perfected, and dehumanised even. But what about the repertoires within the mothers’ minds who earthed the seeds of “unrest” in the face of a deathly calm? Mahasweta Devi, in Hajar Churashir Maa (Mother of 1084) , her 1974 Bengali novel, provides an alternative plane where these are never forgotten but nurtured like raw wounds.

Time isn’t really an omnipotent healer in these cases.

Also read: Book Review: After Kurukshetra By Mahasweta Devi

A civilisation with its trio feathers of modernity, civility, and normalcy can be highly elusive. Here comes the necessity to metamorphose and obliterate those memories, heavy with a critique of this normalcy. The Naxalite movement, the spontaneous plot device of Hajar Churashir Maa , representative of many other past and contemporary not so pro-state movements, was such an inventory of counter state actions and narratives. Thus, along with systematically killing its leaders and participants, it became necessary to completely do away with any and every traces of memory that could reiterate its dominant being.

In Hajar Churashir Maa , after hearing the news of his murder, the instant attempt to confine all the traces of Broti , the deceased Naxal rebel, to his third-floor room by his family could seem brutal and shocking to his mother, but it was not so for the neighbours, the elements of a disciplined modern society who rather was surprised to know that this sophisticated middle-class household could house a social menace like Broti ! The attempt to liquidate the existence of such poisonous outgrowths of society, both from individual and collective reminiscence, is best represented by the author in Hajar Churashir Maa when Broti’s sister’s engagement took place on the very date of his first death anniversary.

However, as a counterpoise to that, it could never really be obliterated from the memories of the mothers. Hajar Churashir Maa starts from the inception of life, Sujata’s son Broti and the discomforting unglorified days of a mother with a child in her womb. But gradually, for Sujata through the seasons of her life and her son, with her husband and other four children settled along their lines, Broti became the only solace to whom she could return to at the end of the day and vice versa. However, the reader does not get a graphic clue about Broti’s journey into the rebel consciousness, just like Sujata’s oblivion about the same in Hajar Churashir Maa . This anguish of being numb to the constructed societal discrepancies transcends the shadow-lines of any one particular movement and embraces the placard against manufactured discipline at large. So, here Broti became a juxtaposition of all those who dared to question norms of a society, who declined to surrender to fate, whose ideas refused succumbing to lifeless bullet marks or prison tortures!

A myriad plane accommodating Somu’s mother (Broti’s friend and ‘accomplice in crime’), his sister, Broti’s love interest, and his mother stood in the face of the civilisational silence and “betrayal” (Hajar Churashir Maa). Their crisis, desperation, love, resistance, angst resonate and attack, if not shatter, the graveyards of conscience that the society so carefully manufactures. These emotions were as multifarious as their beholders. In Hajar Churashir Maa , Somu’s mother belonging from a not so sophisticated family was way more expressive with her loss. She was like any character from a Rittwik Ghatak film, where the director focusses on the explicit expression of any and every emotion his characters’ experience.

Somu’s sister and Sujata were two sides of the same coin. Bearing with their existence and exposure to the outside world, in Hajar Churashir Maa , their processing of the grief was much more internalised and haunting to the minds of the reader, much like the short drastic mourning of Sarbajaya processing the untimely death of her daughter in Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali . Nandini was much like Sujata , she suffers but doesn’t succumb. The dissatisfaction within, fresh with the loss of loved ones still lives on in her every single breath. They live with their memories of existence, a composite being that can never give in to a constructed collective amnesia. In the state’s attempt to not build any commemorative sites of memory for such disgraceful uprising, these networks of motherhood (both biological and metaphorical) itself became such a “lieux de memoire” (Pierre Nora) or the site of memory.

Often as explained by Yosef Yerushalmi, the act of forgetfulness is only possible for those who lived through the memory. With the succession of generation or aging of the historical agents, this forgetfulness is enabled. This anxiety culminated into an endless crisis of losing Broti again, his spirit, his essence altogether again in Hajar Churashir Maa .

Often as explained by Yosef Yerushalmi, the act of forgetfulness is only possible for those who lived through the memory. With the succession of generation or aging of the historical agents, this forgetfulness is enabled. This anxiety culminated into an endless crisis of losing Broti again, his spirit, his essence altogether again in Hajar Churashir Maa . When all the ‘Sujatas’ and ‘Nandinis’ die in the real world, this site of living memory may also perish along with them. With the absence of these “memory entrepreneurs” (Jelin 50), the subjective and biased state narrative is what is made legitimate and permanent in the social memory. Their death is never ceremonial; no processions or gun salute accompany them; the state discards their identity and just assigns a serial number to the dead body stored in the morgue. Thus is created a carefully ordained narrative of the whole phenomenon which can be called a myth as far as Roland Barthes’s interpretation of myth is concerned. The movement was tagged to be emanating out of a certain group of trouble makers- the Naxals, completely neglecting rather negatively manoeuvring the causality behind its occurrence.

Also read: Mahasweta Devi’s Draupadi As A Symbol Of Subaltern Defiance

This myth which is considered to be “the most powerful instrument for presenting and forming the past” runs contrary to individual memories. Hajar Churashir Maa can be used to debunk the gap between myth and reality of such defiance, for it provides the foundational ethos behind those ‘disorders’. Thus the mothers of many such thousand eighty-fours continue commemorating, preserving and caring all those miniscule of identities that are said to be “misinformed” and “misguided” but still are the only knights in the shining armour to get us through!

Works Cited

- Devi, Mahasweta . “Hajar Churashir Maa”

- Jelin, Elizabeth. “ State Repression and labors of memory .” Translated by Judy Rein and Marcial Godoy-Anativia. Contradictions, Volume 18. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2003. Print.

- Koczanowicz, Leszek. “Memory of Politics and Politics of Memory. Reflections on the Construction of the Past in Post-Totalitarian Poland.” STUDIES IN EAST EUROPEAN THOUGHT. Vol. 49, No. 4 (Dec., 1997), 259-270. Web.

- Nora, Pierre. “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire”.REPRESENTATIONS, No. 26, Special Issue: Memory and Counter-Memory (spring, 1989). 7-24. Web.

Haimanti Mukhoti is a post graduate student of History in Delhi University and can be found on Facebook and Instagram .

Wonderful article!

Comments are closed.

Related Posts

Historic Victory For Adivasi Land Struggle In Nilambur, Kerala

By Naveen Prasad Alex

10 Ecological Fiction Masterpieces Weaving India’s Environmental Ethos

By Sahil Pradhan

Book Review: In ‘Crying In H Mart’ Food Is Memory

By Shivani Yadav

roughghosts

words, images and musings on life, literature and creative self expression

A chronicle of pain: Mother of 1084 by Mahasweta Devi

The pain had come at eight in the evening. Hem with all her experience had said, It won’t take time, Ma. The womb has started pushing it out. Hem held her hands and said, Let all be well. Let God bring you back, the two of you separate.

Sujata’s story is framed and defined by pain. As it opens she is asleep, her dreams have transported her back twenty-two years, to the morning following an agonizing night of labour and emergency surgery when she gave birth to her fourth child and second son, Brati. Now she is awoken by searing pain once more, on the same date, January seventeenth, but this time an inflamed appendix is to blame. Once her abdominal distress begins to settle, a glance at the calendar takes her back to the early hours of yet another January seventeenth, just two years earlier, when the telephone suddenly rang. At the other end of the line, a voice summoned her to the morgue. There she would find her beloved son reduced to a numbered corpse, 1084.

Brati, the youngest son, had always been unlike his other siblings. Imaginative and sensitive, he was easily frightened and deeply attached to his mother. From his earliest years on through adolescence, their bond was close while there was little love lost between Dibyananth and his second son. Naturally Sujata was blamed for spoiling him and making him weak. When Brati is killed with a group of young Naxalite revolutionaries, his father’s immediate concern is to assure that no one knows of his involvement. He pulls a few strings and Brati’s name is omitted from the news reports while at home all evidence of his existence is cleared away and locked in his bedroom on the uppermost floor. Sujata finds herself on the wrong side of her own family, on the side of the dead man who had failed to consider the shame and embarrassment he would cause. She is left alone to try to make sense of why her son had been drawn to such a radical movement and to understand the events of the night on the eve of his twentieth birthday that had cost him his life. It was a death that could not be classified in any of the usual ways—illness, accident, crime:

All that Brati could be charged with was that he had lost faith in the social system itself. Brati had decided for himself that freedom could not come from the path society and the state offered. Brati had not remained content with writing slogans on the wall, he had come to commit himself to the slogans. There lay his offence.

Extending from morning to evening over the course of a single day, exactly two years after his death, Mother of 1084 chronicles Sujata’s attempt to honour her son’s memory and perhaps find some sense of closure. At home, Tuli is preparing to hold her engagement party. Although it is her brother’s birth anniversary, the date has been determined by her future mother-in-law’s American guru—her own mother’s feelings be damned. Between attending to the necessary arrangements in the house, Sujata will make two excursions that will help fill in some of the missing information she craves, but not necessarily bring any peace.

In the afternoon she travels out from central Calcutta to the colony where the mother of Somu, one of Brati’s friends, lives. The young men killed had spent their last hours in her house. Sujata had first met Somu’s mother when she went to identify her son’s body and she had found in this poor woman a kind of a kindred spirit, another mother who understood the loss. But face to face with the graphic details of that fateful night and the absolutely devastating effect it has had on this impoverished family, she is reminded that her social status will forever be a barrier that cannot be wished away. The two women, brought together in shock and pain at the morgue and the crematorium, share an affinity that can never be more than temporary:

Time was stronger than grief. Grief is the bank. Time the flowing river, heaping earth upon earth upon grief.

Later that afternoon, Sujata makes another outing, this one closer in location and class, but again one with a divide that cannot be breached. For the first and last time, she visits Brati’s girlfriend Nandini who has recently been released from prison, bearing the injuries of torture and incarceration. In this encounter there is a bitter demonstration of the activist’s unshakable resolve, something the grieving mother will never fully appreciate. Upon returning home to where guests are gathered, Sujata is clearly affected by her experiences, and all of the memories and details that have come back to her over the course of that day. But even as pain rips through her abdomen, she must once more attempt to play her role as wife and mother. At least for the moment.

One of Devi’s most widely-read books, Mother of 1084 is not explicitly concerned with the broader political context of the Naxalite insurgency, rather it turns its attention to the intimate human experience—the appeal of the movement to individuals from different backgrounds, the reality of betrayal, the brutality of the violence, and the wide range of responses from the families and communities affected. That is not to suggest that this is not an intensely political work, but by centring an apolitical protagonist who finds herself navigating the space between the shocking indifference of her family and social class, the devastation of the bereaved who exist in the midst of conflict and destitution, and the anger of the activist committed to the cause at all costs, Devi crafts a powerful, unforgiving narrative. Sujata is the troubled conscience of this tightly woven novella but one is ever aware how very small she is against society’s pretense of normality in a time of upheaval.

Mother of 1084 by Mahasweta Devi is translated from the Bengali by Samik Bandyopadhyay and published by Seagull Books.

Share this:

Author: roughghosts

Literary blog of Joseph Schreiber. Writer. Reader. Editor. Photographer. View all posts by roughghosts

4 thoughts on “A chronicle of pain: Mother of 1084 by Mahasweta Devi”

Even at a much lower level of activism, not involving violence, the breach in families stranded on either side of a political divide can be enduring. I sometimes wonder if activists realise the price to be paid. I’m thinking of people estranged from their families on opposing sides of the gay marriage debate here in Australia, of people who put everything on the line in the campaign to end the Vietnam War. How much more difficult it would be for people caught up in radicalisation that they don’t understand…

Like Liked by 1 person

With this situation, as with having a gay family member, it’s a question of the family being more concerned about what their social group will think. What makes this book so powerful is that in the wake of her son’s death Sujata makes an effort to educate herself to understand, her unconditional love for Brati never wavers, yet she remains alone and trapped by her social class.

- Pingback: Twenty Seagull books to mark forty years of publishing magic: A 2022 reading project wrap up – roughghosts

- Pingback: Roughghosts is nine years old today – roughghosts

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

GetSetNotes

Mahasweta Devi Mother of 1084 Summary

Sujata, often dreams about a morning twenty-two years ago when she was packing her bag to give birth to her child, Brati. Sujata’s mother-in-law did not support her during childbirth and would leave the house to live with her sister. Sujata’s husband, Dibyanath, did not accompany her during childbirth and showed little concern for her well-being. Sujata experienced pain during childbirth and eventually had to undergo an operation to save the child. Sujata’s husband was not present during the birth of their child and would sleep in a separate room to avoid disturbance. Sujata’s husband showed concern for her health only when he desired intimacy. Sujata had a difficult pregnancy and felt violated and defiled throughout the nine months. Sujata’s child, Brati, was born on January 17th, but two years later, on the same day, Sujata received a phone call informing her of Brati’s death. Sujata went through a period of grief and depression, during which she was unable to function normally. After three months, Sujata slowly started to resume her normal activities and noticed that the telephone had been moved to her son Jyoti’s room. Sujata’s family members were successful and well-established in their careers.

The family no longer has anyone to do something out of the ordinary or commit a crime that would require Sujata to identify a dead body in the morgue. Jyoti’s father had to pull strings to hush up the news of his son’s scandalous death. Sujata’s husband, Dibyanath, prioritizes his own position and security over the death of their son, Brati. Dibyanath successfully removes any mention of Brati’s death from the newspapers. Sujata starts working at a bank to support the family after Dibyanath faces problems at his office. Sujata’s presence at the bank is met with stares and silence from her colleagues. Bhikhan, a coworker, sympathizes with Sujata due to the death of his own son. Brati’s death raises many unanswered questions, and his file is abruptly closed without any resolution. Sujata asks Dibyanath about removing Brati’s portrait and belongings from the house, to which he confirms he has done so. Sujata questions why Dibyanath made these decisions regarding Brati’s belongings.

Sujata is struggling to come to terms with the loss of her son, Brati, and is trying to remove all traces of his existence from their home. Brati used to sleep in a room on the second floor and had a fear of sleeping alone, which led to arrangements being made for Hem to sleep in the same room. Brati had outgrown his childhood fears and developed a fascination with death and poetry about death. Sujata has vivid dreams about Brati, where he is still present and she longs for his return. Sujata questions herself and wonders if she played a role in Brati’s death or if there was something she could have done differently. Dibyanath, Sujata’s husband, accuses her of turning Brati against him, but Sujata denies this and questions why Brati had such animosity towards his father. Sujata reflects on her own upbringing and the values she holds, which align with Dibyanath’s, making his accusations unfounded. Brati’s death is not due to sickness, accident, or criminal activity, but rather his rejection of societal norms and his commitment to revolutionary slogans. Brati and others like him are considered antisocial and their bodies are taken to the morgue and burned at night under police protection. Sujata discovers Brati’s handwritten slogans and learns about the dangerous activities he and his friends were involved in, including writing slogans on walls. Kalu, one of Brati’s friends, is shot while writing a slogan on a wall, leaving the sentence unfinished.

Brati and his friends belongs to a new generation that challenges the establishment. Brati and his friends write slogans on walls, knowing that it puts their lives at risk. The society they reject is ruled by profit-driven businessmen and self-interested leaders. They believe that those who adulterate food, drugs, and baby food have the right to live, but Brati is considered a worse criminal because he has lost faith in this society. The text explores the idea that once a young person loses faith in society, death becomes their inevitable fate. They are sentenced to death by anyone who believes in the establishment, without needing any legal sanction. The main question raised is whether Brati’s death and the deaths of his friends have extinguished their cause or if their deaths stand as a rejection of the establishment. The text also delves into the perspective of Sujata, Brati’s mother, who mourns his death and keeps his room intact, speaking to him as if he were still alive. The narrative introduces Nandini, a friend of Brati’s, who contacts Sujata and arranges to meet her. Sujata prepares for her daughter Tuli’s engagement party and reflecting on her own independence and the importance of her job.

Tuli resents her mother, Sujata, for prioritizing her job over household responsibilities and childcare. Tuli is engaged to Tony Kapadia, and the engagement is being formally announced on Brati’s birthday. Tuli plans to have an operation for appendicitis after her wedding. Tuli is frustrated with the lack of discipline and convenience in the household. Sujata and Tuli have a disagreement about religious beliefs and rituals. Tuli is unhappy with how her family handled the death of Brati and feels they are trying to cover up the incident.

Sujata is the only one in her family who does not blame Brati for disrupting their lives. Sujata has made up her mind to never seek consolation from those who prioritize themselves over Brati. Sujata feels closer to Hem than to Brati’s father, brother, or sisters. Brati is considered part of the “other camp” by his family because he does not behave like them. The family would have accepted Brati if he had followed their behavior patterns. Sujata has never been unhappy with her family’s behavior and has learned to accept things as they come. Sujata’s husband, Dibyanath, has always been unfaithful, but his mother sees it as a sign of virility. Brati is different from the rest of the family, as he is not easily scared or intimidated. Sujata has become possessive about Brati and has protected him from her husband and mother-in-law’s dominance. Sujata wonders if her husband and mother-in-law feel guilty towards Brati and hide it through their roughness or reserve. Sujata expresses her wish for Tuli to be happy in life.

The colony in West Bengal grew haphazardly without any plan, as residents grabbed land and settled down. The government neglected the region, denying it basic amenities like roads, health centers, and public transportation. The region experienced unrest and violence for two and a half years, with bombings, killings, and chaos. However, the situation has now calmed down, with no signs of violence or panic. The killers from the past have changed their appearance and move around freely. The region has returned to a state of normalcy, with happy and peaceful households, hoarding of rice, and crowded cinemas and temples. Sujata, who is grieving the loss of her son Somu, finds solace in the house where he once lived. Somu’s sister, burdened with running the household, shows hostility towards Sujata’s visits. Sujata reflects on the loss of those who died and the impact on their families. Somu’s mother recounts the night of the incident when Somu, Partha, and Brati slept together in their small room. Brati used to visit Somu’s house frequently, enjoying tea and spending time there.

Sujata is reflecting on her son Brati, who had become distant and mysterious to her. Brati had been involved in some kind of revolutionary activity and had trusted people who ultimately betrayed him and his group. Sujata discovers that Brati had left memories and mementos with Somu’s mother, showing that he had a connection with her as well. Brati had been waiting for a call that never came, indicating that something had gone wrong with his plans. Sujata and Brati have a conversation about their relationship and Brati’s behavior, with Sujata questioning if he even needs his mother anymore. Brati deflects the questions and suggests playing a game of ludo instead.

Sujata and Brati play a game of ludo and Brati asks about Nandini. Sujata suspects that Brati knows about Dibyanath’s affair with the typist. Brati questions if he makes Sujata suffer and she reassures him. Sujata reflects on her passive role in the household and Dibyanath’s prioritization of his mother over her. Sujata refuses to give up her job, which is seen as an act of rebellion. Sujata also refused to have another child, causing tension with Dibyanath. Brati shows concern for Sujata and they discuss his upcoming birthday. Brati receives a phone call and asks for money before leaving. Sujata asks where he is going and there is a sense of unease about the safety of certain areas in Calcutta.

Sujata recently discovered old newspapers that revealed the violent events that occurred in Calcutta two and a half years ago. Sujata and Brati were the only ones in their house who read the newspapers, as others found the gruesome descriptions of killings repelling. Despite the city’s familiar landmarks, Sujata felt that Calcutta had changed and become unrecognizable. The newspapers revealed that while the city seemed normal on the surface, there were dangerous incidents occurring, such as killings and demonstrations. The artists, writers, intellectuals, and poets of Calcutta focused on the brutalities happening beyond the border in Bangladesh, ignoring the bloodshed in their own city. Sujata’s son, Brati, had plans to meet a group of friends but was unaware that their messenger had betrayed them, leading to their deaths. Sujata had no premonition of Brati’s fate and only realized the truth in her dreams. The novel highlights the pain and confusion of mothers like Sujata, who are left with unanswered questions and the burden of loss. The thoughts and emotions of Somu’s mother reflect the shared grief and desire for answers among the affected families.

Somu’s mother is grieving the loss of her son, who died while fighting for a cause. Somu’s mother reflects on her own difficult life, being married off at a young age and facing hardships. Sujata, who is visiting Somu’s mother, sympathizes with her and tries to offer comfort. The novel mentions other boys from the neighborhood who have also been affected by tragedy. Sujata realizes that her own grief is not isolated, but connects her to others who have experienced loss. The living conditions of Somu’s mother have deteriorated, indicating the impact of poverty. Sujata feels a sense of belonging and connection in Somu’s mother’s home, but also senses that she is not fully accepted by Somu’s sister. The novel raises questions about the treatment of families of those who defy the system and the existence of unwritten policies affecting them.

There was a policy of silence in West Bengal for two and a half years, during which enemies of society were purged from Baranagar and Kashipur. Various national events, such as the airlifting of elephant cubs to Tokyo and a film festival at Metro, took place as part of a premeditated policy. Sujata, a mother, feels that the youth in West Bengal are being hounded and threatened, while the nation and state refuse to acknowledge their existence. Sujata is disturbed by the pretense of normalcy and the silence of society regarding the killings and persecution of the youth. Time has caused a rift between Sujata and Somu’s mother, erasing the temporary unity brought about by grief. Sujata’s daughter faces difficulties due to her brother’s affiliation with the Party, and they encounter taunts and threats from his killers. Sujata realizes that the killers are freely moving about and taunting others, while cultural festivals and fairs continue unaffected. Somu’s mother suggests that Sujata can console herself with another son, but Sujata cannot openly express her grief. The novel ends with a recounting of the night when Somu and Brati were forced to leave their house, with Brati being the first to go out.

A group of young men goes out together, armed with knives, to protest. They are met with violence and one of them, Bijit, is killed. The father of one of the boys, Somu, tries to seek justice but is met with indifference and corruption from the police. The mother of Brati, mourns his death and reflects on his motivations for joining the protest. The part ends with the revelation that it would have been Brati’s birthday the day after he was killed.

Mother of 1084 Summary (late afternoon & evening)

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The mother of 1084. Hazaar Chaurasi Ki Maa 2022-10-30

"Walk Well, My Brother" is a poignant and moving film that tells the story of two brothers who are struggling to find their place in the world. Set in rural India, the film follows the lives of the brothers as they navigate the challenges and struggles of poverty, discrimination, and social expectations.

At the heart of the film is the relationship between the two brothers, who are bonded by their love and loyalty to each other. Despite their differences, they support and encourage each other, and are always there for each other when the going gets tough.

One of the most powerful themes of the film is the way in which the brothers are able to overcome adversity and achieve their dreams, despite the many obstacles that stand in their way. Through hard work, determination, and a strong sense of purpose, they are able to break through the barriers that have held them back and pursue their goals with confidence and determination.

Another important theme of the film is the power of education. For the brothers, education is a way to break out of the cycle of poverty and discrimination that has held their family back for generations. Through their studies, they are able to gain the knowledge and skills they need to succeed in life and make a positive difference in the world.

Ultimately, "Walk Well, My Brother" is a powerful and inspiring film that showcases the strength of the human spirit and the power of perseverance and determination. It is a must-see for anyone who has ever struggled to overcome obstacles and follow their dreams, and is a testament to the idea that with hard work and determination, anything is possible.

Hajar Churashir Maa

The entire story takes place on the second anniversary of his death, which is also the day of her daughter's engagement party to socialite Tony Kapadia, because Tony's mother's guru who lived in the United States had said that was the most auspicious date. During his period of struggle, he comes into contact with a young girl, Nandini, who is also a member of the underground movement and with whom he shares his vision of a new world order. In the spring of 1967 the peasants of Naxalbari, in West Bengal, aided by the intellectual Left in love with the communist ideology, staged a successful rebellion against the landlords, who were supported by the system and the establishment. By engaging with a textual portrayal of the play through Foucauldian and Agambenian critical lenses, this article interrogates the ways in which biopolitics coerces populations within the contemporary socio-political milieu. Parents always play an important role in raising children. Recording contemporary history was Devi's self-imposed mandate. The Naxalite movement spread to other parts as well.

Mother of 1084 : Mahasveta Debi, 1926

His father bribes the police and hushes up the death from the media, unwilling to be associated with the revolutionaries; the play is the story of his mother's reconstruction of Brati's other life, his true life. While she felt unsure about the house, she entered anyway because she did not know any better How Does Kafka Present The Struggles In Gregor's Life Gregor clearly dislikes his role of being the only one working. What are you talking about? The novel offers a unique perspective on the armed political movement that shook Bengal in the 1970s, claiming victims among both the urban youth and the rural peasantry, leaving its impact not just on the political and administrative landscape but also on the families of those who died. If you are ordering from the US or the UK or anywhere else in the world, your order will be shipped from the University of Chicago Press' distribution centre, Chicago. .

Discuss the themes of mother of 1084

She is shattered by the news that her son is dead. Published in Bengali in 1974. Jyoti busy in dialing a number. That is the reason Naxalites can be seen by historians as ruthless terrorists. The mother of 1084 is one of the most read novels of Mahasweta Devi.

Her subjects were the cycle rickshaw puller and the bricklayer working on boiling city streets, farmers threatened by factories, peasant communist guerrillas wielding sickles against the State and impoverished wet nurses hired out to suckle wealthy babies. Tuli : Are we not worthy enough to pronounce his name? Mahasweta's mother Dharitri Devi was also a writer and a social worker. Belonging from a very humble Premium United States Management Investment Phoolan Devi Phoolan Devi the Bandit Queen of India By Anthony Bruno Another St. Grief is the bank, Time the flowing river, heaping earth upon earth on grief. As far as I could remember my mother has always been there for me.

A Brief Guide To Mother Of 1084 Summary And Critical Analysis Essay

In the field of Indian English Literature, feminist or woman centered approach is the major development that deals with the experience and situation of women from the feminist consciousness. The neglected and suppressed plight of the woman is represented by Sujata Chatterjee, mother of the protagonist of the play Brati Chatterjee whose ideology i. Brati is identified only as Corpse Number 1084. She was born in 1926 in Dhaka, to literary parents in a Hindu Brahmin family. Hajar Churashir Maa means Mother of 1084 is story of a mother Sujata whose son Brati , corpse number 1084 in the morgue, was brutally killed by the state because of his ideology of advocating the brutal killing of class enemies, collaborators with the State and counter-revolutionaries within the Party. Having found a soul mate in Brati, she turns her back on Dibyanath and his decadent value-system.

Hazaar Chaurasi Ki Maa

For example one of the many times she has been there for me was when she taught me the difference between healthy food and junk food. The translation is faithful to the original, but the substitution of standard English for the colloquialisms and syntax of the original has taken a toll from the poetic flow of the dialogue. As the mother, Sujata, relives her son's life, we are also given a taste of Devi's satire, as in the reference to the cultism that has vitiated religion and elitism. Mahasweta Devi is one of the foremost literary personalities, a prolific and best-selling author of Bengali fiction. She is basically a social activist, who further has added another feather to her field through her writing. The Indian playwright Mahasweta Devi's Anglophone play-text Mother of 1084 1973 enables scholars to participate in a critical forum on biopolitical praxis, because of its pervasive and explicit representation of state violence and rebels. When I next read Samik Bandyopadhyay's introduction to the novel, I saw yet another cross-cultural dialogue: that between the two translators, Spivak and Bandyopadhyay, between the culture of an expatriate critic steeped in the language and concepts of contemporary Western literary criticism and the culture of an India-based this is my inference scholar steeped in Bengali literature, who reads the stories and plays with the author's intent in mind.

Mother of 1084 by Mahasweta Devi

So right away the reader learns that Gregor is seen more as a source of income, rather than given the time and love he needs to be in this situation. Abstract: Identity crisis or search of identity has received an impetus in the Post-Colonial literature. She writes novels, short fictions and plays in Bengali and has made a mark in all three genres. It focuses on the large body of working class immigrants and the issue of marginalization. I have chosen to focus on Mother of 1084, because we have both a novel and a play of that name. Unaware of his secret mission, Sujata is not able to dissuade her son from joining this movement. Translated into English by Samik Bandyopadhyay, published in 2010.

Marginalization In Mahasweta Devi's 'Mother Of 1084'

The neglected and suppressed plight of the woman is represented by Sujata Chatterjee, mother of the protagonist of the play Brati Chatterjee whose ideology i. Each of the five plays deals with different specifics, but both the thrust and the technique are similar to Mother of 1084. In 1948, she gave birth to Nabarun Bhattacharya, currently one of Bengal's and India's leading novelist whose works are noted for their intellectual vigour and philosophical flavour. While Naxalites can be seen by historians as ruthless terrorists, Devi's focus is on the young intellectuals who were drawn to the cause because of their idealism, and on peasants and tribals who were drawn to it because they were victims of centuries-old oppression. Translated with an Introductory Essay by Anjum Katyal. In the second part, the paper traces the political narrative embedded within the novella, connects it with the historical narrative and the characterization of the protagonist.

The Mother Of 1084 By Mahashveta Devi Radhakrishna Publication Delhi : Radhakrishna Publication Delhi : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

In the play Mother of 1084 a young, idealistic student intellectual, Brati Chatterjee, is treacherously betrayed to the police by a mole in his revolutionary group. She enters into the little known world of slum dwellers. He grows lustful of her. Significantly, Sujata makes several other discoveries, only after the sudden and mysterious death of Brati, her younger son, with whom she had always shared a very special relationship. In the process, she also initiates Sujata into the little known world of the underground movement, explaining to her the logic for an organized rebellion, giving her first hand account of state repression and its multiple failures.

- Description

In the 1970s, Mahasweta Devi dramatized one of her major works, Mother of 1084 , and four of her finest stories, convinced that as plays they would be more accessible to the larger audience she wanted to reach. In the five plays collected here, the mother of a Naxalite martyr ‘discovers’ her son (and, in the process, herself) a year after his death; a man enslaved by an ancient bond discovers that the bond has turned to dust years ago; a ventriloquist intensely in love with his ‘speaking doll’ loses his voice to throat cancer; a son acknowledges far too late his mother who has been outcast and branded a witch by the community; and a traditional ‘water-diviner’ rises to a different role, immediately becoming a threat to the administration.

Rooted in history, and following myth as well as contemporary reality, with socio-economic milieus ranging from the urban bourgeoisie to the urban underworld, rural untouchable settlements to adivasi communities, these plays offer a view of India rarely seen in literature.

Orders will be shipped from Seagull Books, Calcutta.

Please note: For customers paying in currencies other than Indian rupee or US dollar, prices will be calculated according to the currency conversion rate at the time of purchase and may vary from the printed price.

Print and ebook orders will have to be processed separately. Please bear with us. [email protected]

Related Titles

Mother of 1084, the queen of jhansi, breast stories, mirror of the darkest night, chotti munda and his arrow.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

MAHASWETA DEVI’S MOTHER OF 1084: AN EXPLORATION

‘Dramatic Realism’ means ‘objective experience’ and ‘social truth’ and in that drama becomes a powerful weapon for exposing and demolishing social evils and injustices. As an anti-establishment artist Mahasweta Devi always committed herself socially and ethically in order to give voice to the marginalized and the downtrodden. Like Shaw she employed drama not merely for faithful documentation of contemporary social evils, but as active medium for revolting against authority and other social constraints. The play Mother of 1084 (1997), actually a translation of her early Bengali novel, titled Hajar Churasir Ma, conscious of the political happenings of Naxalite Bengal, focuses on the exploitation and deprivation of the tribal and the marginalized people, the landless and the curse of landlordism and feudalism, and aboveall the neglected and subjugated fate of women. The plot, a diatribe against decadent social institutions articulates ‘the awakening of an apolitical mother’, which has an urban middle class setting. Through Brati’s (the protagonist) whose commitment to the revolutionary Communist ideology led to his killing in an ‘encounter’, self-sacrifice the dramatist debunked the ‘spent-up intellectuals’, ‘cocktail parties’, the meaningless ‘Godmen’ and the so called radicals. Somehow the play mirrors the whole gamut of a hypocritical culture with its brooding over the Bangladesh war, amorous scandals, a world of ‘affluence’, of ‘pseudo-religion’, selfishness, of drinking, whoring and abnormal relationships. Yet in Sujata, the deprived mother, ‘a new woman is born’. Sujata’s past life, her isolation, her philandering husband, her unwanted motherhood all ultimately ends up in her self-realization which itself becomes a convenient and powerful protest against the rotten societal value system. Key Words Social reality, problem play, anti-establishment, political, subaltern,

Related Papers

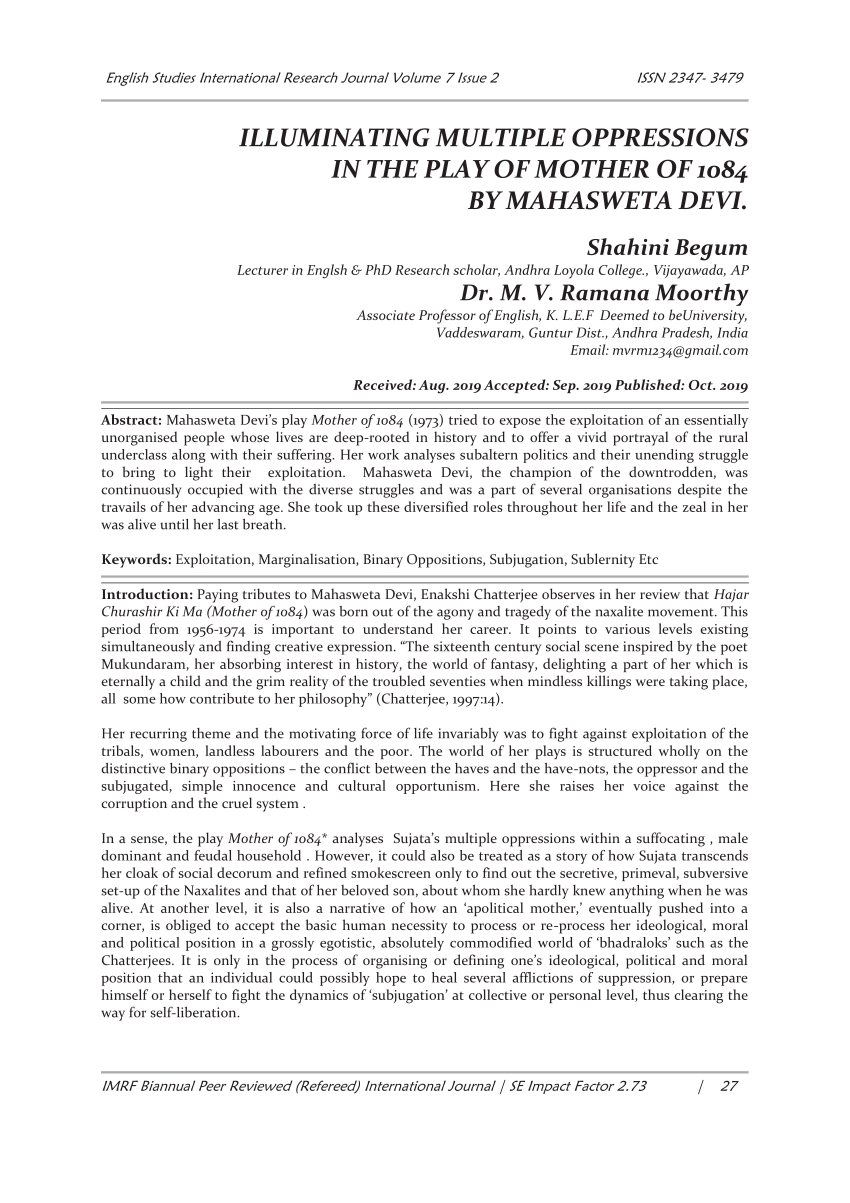

English Studies International Research Journal Volume 7 Issue 2 ISSN 2347 - 3479

ramana moorthy meduri

Mahasweta Devi’s play Mother of 1084 (1973) tried to expose the exploitation of an essentially unorganised people whose lives are deep-rooted in history and to offer a vivid portrayal of the rural underclass along with their suffering. Her work analyses subaltern politics and their unending struggle to bring to light their exploitation. Mahasweta Devi, the champion of the downtrodden, was continuously occupied with the diverse struggles and was a part of several organisations despite the travails of her advancing age. She took up these diversified roles throughout her life and the zeal in her was alive until her last breath. Keywords: Exploitation, Marginalisation, Binary Oppositions, Subjugation, Sublernity Etc

Research Journey

Shyaonti Talwar

This is the idea of the paper. It incorporates a slightly Marxist feminist perspective that basically works on the premise that we are all agents in the production cycle like cogs in a wheel and we have different roles to play to keep the production cycle going and all institutions and arrangements in society that we see are determined by economics. Men and women through their different roles in the cycle of production create a society which in turn shapes them. Marriage is a contract which has economic reasons and the family acquires the status of a hegemonic institution because it is instrumental in facilitating production and in furthering the interest and the material wellbeing of the state. The man works for the state, the woman works for the man and she also reproduces so in other words she brings in more workers or caretakers which will contribute to this cycle of production. I have taken up Mahashweta Devi’s MO1084 and I am looking at how she is trying to disrupt the family as a hegemonic institution and critiquing its functioning just as a mere tool of the state which undermines individual growth and well-being of a person. So we have grieving mother Sujata who has lost her son to the Naxalite movement and she is the only one who is mourning his death. But not publicly. Because they belong to a particular social class, the Bengali bhadralok or the bourgeoisie their actions and reactions and even the dynamics within the family are determined and governed by their class consciousness. So the Brati the dead Naxalite son who has brought bad name to the family is reduced to a number 1084 and disowned in many ways by the family. They don’t discuss him, they obliterate him from their thoughts and they go on as if nothing has happened. Because that’s whats best for the family and the family name and the family business. Except Sujata. She is torn between conforming to middle class standards and mourning over her dead son. And if she is seen to be grieving she allows herself to be labelled as strange, not dutiful enough to her husband and his reputation. So devi gives us a glimpse of this family where no true bonds exist either between the couples, all the married couples share a very perfunctory arbitrary relationship. They are just married to each other because it is socially correct to remain married. There is no bond between the children and the mother because they are in different camps playing the game of capitalist patriarchy. SO through this model of a dysfunctional family devi exposes the decay and the damage which submission to the state machinery can cause to a family and how the family in turn because of its puppetlike existence can be detrimental to the well-being of the individual, how it can lead to estrangement and frigidity and ostracism and marginalisation and finally death. And the paper of course attempts a very close reading of the text to substantiate and consolidate this argument.

International Research Journal Commerce arts science

Mahasweta Devi is one of the leading writers of our times. Translated into many languages, her works have won her international acclaim and prestige. Her voluminous writings, cemented by her activism, has made her the celebrated writer of social commitment. Committed to the cause of tribals, peasants, landless labourers, bonded slaves and oppressed women, Mahasweta Devi has wielded her pen to raise the voice of these downtrodden people. The mother of 1084 is one of the most read novels of Mahasweta Devi. Set in the background of the Naxalite Movement of Bengal in the seventies, this novel focuses on the emotional and psychological crisis of a mother whose son is killed in this movement. Sujata, the mother of Brati, becomes the voice of all women who have to bear the emotional setback due to this and other such movements. Sujata becomes a living dead body after her son's death. Analysing the cause of this movement and the death of her son, she comes face to face with her own real self which hitherto has been suppressed by her callous husband. In this paper my endeavour will be to trace Sujata's journey through the emotional vacuum created Brati's death. Mahasweta Devi is one of the foremost literary personalities, a prolific and best-selling author of Bengali fiction. She is basically a social activist, who further has added another feather to her field through her writing. She has been working with the tribals and the marginalized communities so that their real stories could reach the authorities at the helm of affairs. Devi started her career as a socio-political journalist whose articles have appeared regularly in the Economic and Political Weekly, Frontier and other journals. Mahasweta Devi has made a significant contribution in the field of literary and cultural studies in our country. Her research into oral history of the cultures and memories of tribal communities is a first of its kind. Her powerful and horrifying tales of exploitation and struggle

Creative Saplings

This paper attempts to evaluate the resistance to the ethnic and gender subalternity portrayed by Mahasweta Devi n the story, Draupadi. Mahasweta Devi portrays a figure of resistance to the multi-layered subalternity through the rejection of gender performative acts in both theatrical and non-theatrical contexts of subaltern. The story, Draupadi, challenges the conventional phallocentric representation of gender subalterns and colonial domination over marginalized ethnicity through the construction of the character, Dopdi Mejhen (or Draupadi), a young Santal widow, fighting for the socioeconomic freedom of her tribe, who radically stands naked exposing her blood spotted body against the oppressive colonizer after extreme physical oppression, to protest the patriarchal and colonial domination over her body and ethnic community. She is subaltern by her class, caste and gender; but liberates herself from subalternity through non-cooperation resistance. This paper applies the theory of 'subalternity' of Ranajit Guha and Chakravorty Spivak to bring out the aspects of multi-layered subalternity and intellectual location of the resistance; and theory of 'gender performativity' of Judith Butler to evaluate the resistance of gender subalternity. This research proves that the conquering resistance to the colonial domination and subalternity is the result of the non-cooperative movement against dominant elitism, rejection of gender performative acts in both theatrical and nontheatrical contexts, radical stand against ethnic representation, existential tactic to disrupt the essential codes and dominant administrative colonial power.

Dr. Haresh Kakde

Ajay Sekher

SMART M O V E S J O U R N A L IJELLH

Mahashweta Devi’s story is about the reawakening of a mother proselytized by the death of her son against the backdrop of the systematic “annihilation” of the Naxalites in the 1970’s Bengal. The uncanny death forces the apolitical mother to embark on a quest for the discovery of her ‘real’ son which eventually leads to her own self-discovery. The discovery entails the knowledge of certain truths or half truths about the particular socio-political milieu in which the characters are located. Sujata conditioned to play the submissive, unquestioning wife and mother for the major part of her life gains a new consciousness about her own reality (as a woman) and her immediate context (the patriarchal / feudal order). She therefore pledges to refashion herself by assimilating her son’s political beliefs of ushering in a new egalitarian world without centre or margin. In Govind Nihalani’s own words his film is “a tribute to that dream”.

priya adwani

Diasporic Sensibility and Consciousness in Poetry of Sujata Bhatt reveal the three very commonly used terms—"self, "personality" and "identity". These terms were constantly under investigation in the present paper ". The purport of this paper is to study inclinations of Bhatt on various themes like feminism which demonstrated the state of a middleclass Indian Woman; who is crushed up, battered and not taken care at all and macro level revolutions. The paper has a study which demonstrates the hatred of Hindu religion and its preplanned commandments in opposition to women. Sujata Bhatt is apprehensive with the diverse social evils ubiquitous in the society. Her Diasporic writing embodies kind of paradoxical experience because of which a tensional quality is at the heart of her writings. The diasporic experience cannot be reduced to a simple-minded rejection or acceptance of the homeland. Sujata Bhatt creates an incorporation of her various diasporic exper...

Somrita Dey(Mondal)

Mahasweta Devi's writings are mostly premised on the project of lending space and voice to the unacknowledged presences of the society. Her task is that of retrieving the silences from the grand narratives of history. After Kurukshetra, comprising three stories that imaginatively recreate certain segments of the epic- too, is no exception. In these stories she has attempted a revisionist reading of the Mahabharata, by bringing to the fore the perspectives of a marginalized section of the society. Her short stories attempt a counter historical depiction of the epic through the eyes of women who are also underclassed, thereby debunking the patriarchal brahminic discourse of the Mahabharata. In these stories Devi has not only granted them space but has also accorded them a superior status. The present paper would like to explore the strategies Devi has employed not only to articulate the silenced peripheries but also to give these dispossessed women an edge over their social superi...

Chitra Jayathilake

Biopolitics—the strategies and mechanisms through which human life processes are managed and regulated under regimes of authority—is ordinary currency in society, and ruling political systems exercise surveillance, incarceration and killings to a great extent in this regard. Michel Foucault's work on the regulation of human beings through the production of power serves as an initial medium of investigation into biopolitics. Yet, Giorgio Agamben probes the covert and overt presence of biopolitical violence in society, particularly through his concepts of state of exception and bare life. The Indian playwright Mahasweta Devi's Anglophone play-text Mother of 1084 (1973) enables scholars to participate in a critical forum on biopolitical praxis, because of its pervasive and explicit representation of state violence and rebels. Nonetheless, the play-text is often renowned for its reference to feminist ideology and mother-son relationship. Existing scholarship has overlooked the manifestation of torture and dead bodies on-stage represented in it. The play is also on the periphery of the mainstream literary criticism. By engaging with a textual portrayal of the play through Foucauldian and Agambenian critical lenses, this article interrogates the ways in which biopolitics coerces populations within the contemporary socio-political milieu. The analysis implies a potential to understand the biopolitical logic more meaningfully, and to be resistant to its stratagems of coercion. It adds to the existing body of literature on biopolitics by creating a specific account of life-politics as characterised in postcolonial theatre, provides a supplemental standpoint to debates on biopolitical subjugation and specifically contributes to current discussions of the play.

RELATED PAPERS

International Journal of Engineering Research and Technology (IJERT)

IJERT Journal

Cuadernos De Los Amigos De Los Museos De Osuna

Maria Isabel Osuna Lucena

J. Austral. College Nutrition, Environ. Med

DR. AZRINAWATI MOHD ZIN

Psychiatric Bulletin

Richard Soppitt

Journal of Vegetation Science

Susan Laurance

Simona Cavagna

The Lancet Global Health

Charles Makwenda

Ahmed Ghoneim

Jurnal PADMA: Pengabdian Dharma Masyarakat

Andriko Prasetyo

Journal of Chemical Ecology

Raimondas Mozuraitis

Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies

Gülden İlin

Hector Torriente

British Journal of Pharmacology

Human Molecular Genetics

Tamnun Mursalin

Dennis Vetter

Amber Anderson597

HAL (Le Centre pour la Communication Scientifique Directe)

Azita Ahmadi-sénichault

Chaker Tlili

Journal of Anglican Studies

Andrew McGowan

Martina Gondekova

Michael Kostapanos

Journal of Clinical Anesthesia

Ricardo martinez-ruiz

Virchows Archiv

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

In the play Mother of 1084 Sujata Chatterjee, a traditional apolitical upper middle class lady, an employee who awakens one early morning to the shattering news that her youngest and favourite son, Brati, is lying dead in the police morgue bearing the corpse no. 1084. Her efforts to understand her son's revolutionary activism lead her to ...

alienated, such a knowing mother - and Sujata in Mother of 1084, as is the case - gets stuck in situation of impasse, notwithsatnding travelling back and forth through time within a private space.

At root Mother of 1084 is a historical document of a period of Bengal when Naxalite uprising has been branded as 'extremist' and 'terrorizing'. The Naxalite Movement was Volume V, Issue VIII August 2017 349 IJELLH ISSN-2321-7065 predominantly an economic and agrarian cause in which the tribals and peasants clash with the landlords.

The article attempts to analyze Mahasweta Devi's novel Mother of 1084 in the light of understanding how 'motherhood' has been redefined by highlighting and empowering the 'mother's selfhood'. This novel has been translated from Bengali into English by Samik Bandyopadhyay and published in 2010. The article

Karuna Prakashani, Kolkata. Publication date. 1974. Media type. Print ( Hardcover) ISBN. 978-81-8437-055-3. Hajar Churashir Maa ( No. 1084's Mother) is a 1974 Bengali novel written by Ramon Magsaysay Award winner Mahasweta Devi. [1] It was written in 1974 on the backdrop of the Naxalite revolution in the Seventies.

The novel Mother of 1084 (1974) is set in late 1960s and early 1970 s Calcutta and covers the daylong journey of a mother, Sujata whose younger son Brati has been brutally Killed by the established Government agency. Sujata's journey in search of self-identity is accompanied with several questions to be answered.

The mother of 1084 is one of the most read novels of Mahasweta Devi. Set in the background of the Naxalite Movement of Bengal in the seventies, this novel focuses on the emotional and psychological crisis of a mother whose son is killed in this movement. Sujata, the mother of Brati, becomes the voice of all women who have to bear the emotional ...

Mahasweta Devi, in Hajar Churashir Maa (Mother of 1084), her 1974 Bengali novel, provides an alternative plane where these are never forgotten but nurtured like raw wounds. Time isn't really an omnipotent healer in these cases. Also read: Book Review: After Kurukshetra By Mahasweta Devi. A civilisation with its trio feathers of modernity ...

Mother of 1084 is one of Mahasweta Devi's most widely read works, written during the height of the Naxalite agitation—a militant communist uprising in the 1960s-70s that was brutally repressed by the West Bengal government, leading to the widespread murder of young rebels across the state. The novel focuses on the trauma of a mother who awakens one morning to the shattering news that her ...

This essay examines K.R. Meera's prose as a critique of the patriarchal homo-social economy of exchange in India which does not allow women to embody non-gestational, non-objectified forms of power. ... MOTHER OF 1084 Mother of 1084 epitomises the Indian Government's reaction to the resistance that emerged during the Naxalite insurgency in ...

Postcolonial Indian City-LiteratureLITERATURE AS A SITE OF ACTIVISM: A SELECT STUDY OF WOMEN WRITING IN INDIAThe Plays of Mahasweta DeviCritical Perspectives on Mahasweta Devi's Mother of 1084Political Violence in South AsiaThe Concept of Motherhood in IndiaWestern Drama Through the AgesA Linguistic Analysis of Mahasweta Devi's Mother of 1084 and RudaliMahashweta Devi's 'Mother of 1084 ...

Book Reviews : Mahasweta Devi, Mother of 1084. Translated with an Introductory Essay by Samik Bandyopadhyay. Calcutta: Seagull Books, 1997. 130 pages. Rs 160. Mahasweta Devi and Usha Ganguli, Rudali—From Fiction to Performance. Translated with an Introductory Essay by Anjum Katyal. Calcutta: Seagull Books, 1997. 156 pages, Rs 175.

Set over the late sixties and early seventies, during the first phase of the Maoist-inspired Naxalite insurgency in West Bengal, Mother of 1084 by Indian writer and activist, Mahasweta Devi (1926-2016), is a focused examination of the impact of targeted violence on those left behind through the story of one woman stranded in her loss and grief.

Mother of 1084. The play Mother of 1084 (1997) is the original translation of Mahasweta Devi's Bengali playHajar Churashir Ma that has the best illustrations for the marginalized category. The neglected and suppressed plight of the woman is represented by Sujata Chatterjee, mother of the protagonist of the play Brati Chatterjee whose ideology ...

" Gayatri Spivak in an essay titled "Can the Subaltern Speak"?. Wrote ... Mother of 1084 described almost all the features of the urban phase of the 1971-1974 Naxalite-Movements. Many aspects have been depicted by MahaswetaDevi in this novel, but violence is one of the major factor dealt with the author as the Naxalite had to ...

The thoughts and emotions of Somu's mother reflect the shared grief and desire for answers among the affected families. Somu's mother is grieving the loss of her son, who died while fighting for a cause. Somu's mother reflects on her own difficult life, being married off at a young age and facing hardships.

Mahasweta Devi is one of India s foremost literary figures, a prolific and best-selling author in Bengali of short fiction and novels, and a deeply political social activist who has been working marginalized communities for decades. "Mother of 1084," one of Devi s most widely read works, was written in 1973 74, during the height of the Naxalite agitation a militant communist uprising that ...

Mahasweta Devi is one of India's foremost literary figures. Mother of 1084 is one of her most widely read works, written during the height of the Naxalite agitation - a militant communist uprising that was brutally repressed by the Indian government and led to the widespread murder of young rebels across Bengal. This novel focuses on the trauma of a mother who awakens one morning to the ...

mother of 1084. The sentimental comedy did not last long. The sentimental soon degenerated into sentimentality. This change gradually manifested itself in the advent of replace wit and immortality in the comedy. In this sentimental comedy of Colley Cibber and Steele there was conventional morality and sentimentality in place of grossness of the ...

When the novel Mother of 1084 opens we see that Sujata, the mother gave birth of two sons Brati and Jyoti, and two girls Nipa and Tuli. Brati was the youngest son and he was very close to her mother. One day in a very harsh morning, Sujata awakes from sleep and comes to know that Brati had died. And already police has given him the No. 1084.

A Brief Guide To Mother Of 1084 Summary And Critical Analysis Essay. In the field of Indian English Literature, feminist or woman centered approach is the major development that deals with the experience and situation of women from the feminist consciousness.

Five Plays. Translated by Samik Bandyopadhyay. ₹499.00 $14.99 £11.99. Description. Details. Shipping. In the 1970s, Mahasweta Devi dramatized one of her major works, Mother of 1084, and four of her finest stories, convinced that as plays they would be more accessible to the larger audience she wanted to reach. In the five plays collected ...

At root Mother of 1084 is a historical document of a period of Bengal when Naxalite uprising has been branded as 'extremist' and 'terrorizing'. The Naxalite Movement was Volume V, Issue VIII August 2017 349 IJELLH ISSN-2321-7065 predominantly an economic and agrarian cause in which the tribals and peasants clash with the landlords.

A Brief Guide To Mother Of 1084 Summary And Critical Analysis Essay - PHDessay.com - Free download as PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or read online for free. A brief summary

Marginalization In Mahasweta Devi's 'Mother Of 1084'. Mahasweta Devi had a prominent voice on the international sphere who is prosecuting for the right of equality of unprivileged subaltern and oppressed section of society by expressing miserable condition through her pen. This novel Mother of 1084 is one of the best creations of her writings ...

1 CP Notes. II Semester B.SC. BCA. English. Slow food Nation - Assignment. 1 Basics of computer. Add. eng Text Book For 2nd Year Additional Eng. Summary about mahasweta devi an indian writer in bengali and an activist. she is remembered for submerging herself in the lives of deprived and sidelined as she.