Barriers of Affordable Housing for people on low incomes Essay

The affordability of housing especially by low income people is an issue that has received great attention in the recent past. High housing prices may at times expose an individual or a family to a chance of homelessness especially when their earnings are not enough to cater for both housing and other basic requirements.

In the United States, individuals whose incomes are constant cannot afford to pay for the rising housing costs. Therefore, persons looking for affordable housing are faced with barriers that more often turn out to be insurmountable.

As a result of this, low-income people experience unequal and unfair access to affordable housing. Moreover, the complexity of different housing policies makes it almost impossible to get affordable housing (LaBella & Waggener).This essay looks at barriers of affordable housing for people on low incomes.

Affordable housing has been measured by the ratio of house incomes to the price of available housing. For more than a hundred years, it has been an advocated measure for housing affordability that families should spend less than one-quarter of their earnings for housing disbursals.

Many economists such as Ernest Engel in Norris and Decland (2008) have been wary concerning the issue of affordability. Engel has projected an economic law which states that the ratio of a family’s earnings used for housing is fixed irrespective of the earnings of the household.

This law focuses on food as the most important expenditure in a household. Of importance, food prices would shift based on the size and age of the members of a household and the power to provide for oneself. This ratio could be employed in the making of decisions for reducing risks in leasing a house or giving mortgage to a particular household (Norris & Redmond 2007).

The difficulty of the housing process has created many barriers to access for low income applicants. Furthermore, the costs involved in the operation and maintenance of homes have some effects on the affordability of housing for the low-income persons. Utility costs such as those of natural gas and heating fuels have gone up, thus, these fluctuations affect the affordability of housing (Franko 2009).

The local government policies that raise the costs of construction and place restrictions on the provision of housing are another major reason for the lack of affordable housing for the poor. Impositions of fees as well as inclusionary zoning are especially pricey. If the government was to cut down these prices, then affordable housing would be more available for the low-income individuals (Moriarty 2009)

Along with the creation of more affordable housing, the government ought to take into account other barriers that cause homelessness. These barriers will then need to be looked at in order to achieve the objective of bringing homelessness to an end.

Refining the standard of housing affordability might lead to effectual dispersion of government housing aid and a greater pool of likely home buyers. However, it does not address the difficulties faced by low-income households in acquiring affordable housing posed by increased housing costs (Housing Affordability 2007).

Since affordability standards depend upon the housing costs and income, trends in the distribution of income are significant in explaining the rise in housing costs realised by low-income families. According to Quigley and Raphael, typical households in the United States nowadays find that incomes have not kept step with the price of housing.

Individuals who work at low-salary, insecure occupations are especially susceptible to homelessness. Increasing costs of housing construction is another factor that has led to increase in costs of home ownership. The United States census report in 2000 has indicated that the average price for a brand single family was $207,000.

In 1990, it was $149,800 and, in 1980, it was less than $80,000. An account for this increase would be due to the rise in market demand. Additionally, regulative barriers and building codes raise the costs of housing as well (Quigley & Raphael 2004).

Further, lack of affordable housing is worsened by the fact that some disadvantaged people do not have access to housing. Segregation along lines of race, family size, age, and disability affect such families in terms of affordability of housing (Park & Combs 1994). These families impact the demand of home ownership.

Furthermore, they are the households that are at a high risk of proceedings due to their dubious lending practices which affect their extended housing stableness (Bourassa 1996).

The data taken from the King County from a 2009 rental housing supply, indicate that there is a huge gap between the actual costs of housing and the prices that households can fairly afford. The chart below represents the rental units affordable to low-income households in King County.

Source: Housing Affordability 2007

Deficiency in affordable housing directly relates to homelessness. As the accessibility of affordable housing reduces, the rate of homelessness goes up. In order for the issue of homelessness to be addressed, the problem of deficient affordable housing has to be dealt with first.

Trends in family earnings, housing prices, building and demolition of housing, suggest that fears concerning housing affordability will continue to intensify. Solid public policies, dedications from the private sector, and public support are necessary to diminish shortages of affordable housing. Simultaneously, people are making use of several strategic options to deal with lack of affordable housing.

Communities have become cognizant of income elements that impact affordability of housing and are pushing for development in jobs as well as more liveable salaries. They are re-examining regulative barriers to building of affordable housing all around the state and setting up alternate policies. It can only be expected that affordable housing will, in the near future, become a touchstone of community welfare.

List of References

Bourassa, S 1996, “Measuring the Affordability of Home-Ownership”, Urban Studies , pp. 1867-1877.

Franko, J 2009, Barriers to Affordable Housing. Web.

Housing Affordability 2007. Web.

LaBella, J & Waggener, A, Affordable Housing: Barriers to Equal Opportunity and Access, Housing Works, Boston. Moriarty, S 2009, Barriers to Affordable Housing. Web.

Norris, M & Redmond, D 2007, Housing Contemporary Ireland: Policy, Society and Shelter, Springer, New York.

Park, S & Combs, R 1994, “Housing Affordability among ElderlyFemale Heads of Household in Nonmetropolitan Areas”, Journal of Family and Economic Issues , pp. 317-328.

Quigley, J & Raphael, S 2004, “Is Housing Unaffordable? Why Isn’t It More Affordable?” Journal of Economic Perspectives , pp. 191-214.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, July 4). Barriers of Affordable Housing for people on low incomes. https://ivypanda.com/essays/barriers-of-affordable-housing-for-people-on-low-incomes/

"Barriers of Affordable Housing for people on low incomes." IvyPanda , 4 July 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/barriers-of-affordable-housing-for-people-on-low-incomes/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'Barriers of Affordable Housing for people on low incomes'. 4 July.

IvyPanda . 2019. "Barriers of Affordable Housing for people on low incomes." July 4, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/barriers-of-affordable-housing-for-people-on-low-incomes/.

1. IvyPanda . "Barriers of Affordable Housing for people on low incomes." July 4, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/barriers-of-affordable-housing-for-people-on-low-incomes/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Barriers of Affordable Housing for people on low incomes." July 4, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/barriers-of-affordable-housing-for-people-on-low-incomes/.

- "Compassionate Communication in Patient Care" by Engel

- Nursing Issues: I’m Here by Marcus Engel

- Nicosia Model and Engel Blackwell Miniard Model of Consumer Behaviour

- Impacts of Industrial Revolution

- The Mere Considerability of Animals

- Ethical Issue: Accessibility and Affordability of Healthcare

- Communism Versus Organic Solidarity

- Homelessness in the United States

- Australian Housing Affordability

- Racial Conflict in Ferguson

- Tenant Focused Housing Services

- Housing Market in Sydney

- Housing Problem in Canada

- Housing finance management and organizations

- America's Housing Crisis

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Key facts about housing affordability in the U.S.

A rising share of Americans say the availability of affordable housing is a major problem in their local community. In October 2021, about half of Americans (49%) said this was a major problem where they live, up 10 percentage points from early 2018. In the same 2021 survey, 70% of Americans said young adults today have a harder time buying a home than their parents’ generation did.

A variety of factors have set the stage for the financial challenges American homeowners and renters have been facing in the housing market, including incomes that haven’t kept pace with housing cost increases and a housing construction slowdown . A surge in homebuying spurred by record low mortgage interest rates during the COVID-19 pandemic has further strained the availability of homes.

Here are some of the key measures of the housing affordability crunch in the United States and the reasons behind it.

This Pew Research Center analysis about housing affordability in America draws from Center surveys designed to understand Americans’ views and preferences for where they live. It also uses outside data from sources including the Federal Reserve Bank and the U.S. Census Bureau.

Everyone who took the Pew Research Center surveys cited is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Rising demand for housing meets limited supply

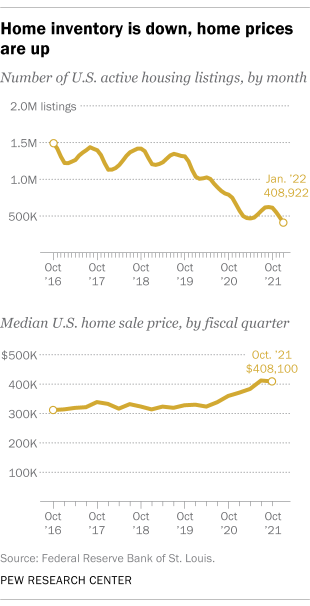

- As home sales have boomed, active housing listings have dropped and the median home sale price has surged, according to data from the Federal Reserve. The number of active housing listings in the U.S. was at its lowest in at least five years in January 2022, with 408,922 active listings on the market. That’s a 60% drop from about 1 million listings in February 2020, just before the coronavirus recession hit the U.S. Around the same time, the national median sale price for a single-family home jumped 25% from $327,100 in the fourth quarter of 2019 (the last full quarter unaffected by the COVID-19 recession) to $408,100 in the fourth quarter of 2021, the most recent data available. The greatest increases were in the West, Midwest and Northeast. Housing vacancy rates, meanwhile, have dropped over the last decade. The vacancy rate for rental units fell from about 10% in 2010 to 5.6% at the end of 2021. The rate for homeowner units is down from about 2.6% in 2010 to 0.9% in 2021 (the most recent year with available data).

- Housing availability has been squeezed by a near-record increase in the number of American homeowners in 2020, a Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data found. There were an estimated 2.1 million more homeowners in the fourth quarter of 2020 than there were a year earlier, equal to the previous record increase in homeowners, which occurred during the housing boom between 2003 and 2004. During 2020, the U.S. homeownership rate also increased to 65.8%, up from 65.1% a year earlier – a large year-over-year change, but still below the historical peak of 69.2% in 2004. The homeownership rate in the fourth quarter of 2021 (65.5%) was not statistically different from the rates in the fourth quarter of 2020 (65.8%) and the third quarter of 2021 (65.4%). Homeownership among households headed by White Americans rose an estimated 0.8 points from 2019 to 2020 – the only racial or ethnic group to see a statistically significant increase during that time. (Homeownership rates did not significantly increase for any racial or ethnic group between 2020 and 2021). In the fourth quarter of 2021, 74% of White adults owned a home, compared with 43% of Black Americans and 48% of Hispanic Americans. These disparities in homeownership have persisted over decades.

Renters are feeling the strain

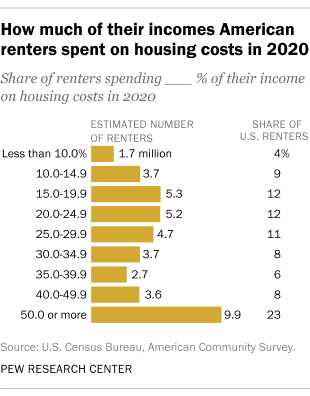

- In 2020, 46% of American renters spent 30% or more of their income on housing, including 23% who spent at least 50% of their income this way, according to the most recent data available from the U.S. Census Bureau . This meets the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s definition of being “cost burdened.” Although spending 30% of income on housing has long been considered the most a household should spend in order to have money left over for essentials, some researchers have argued this housing affordability measure should be adjusted to reflect changes in the cost of other necessities, types of households and other factors.

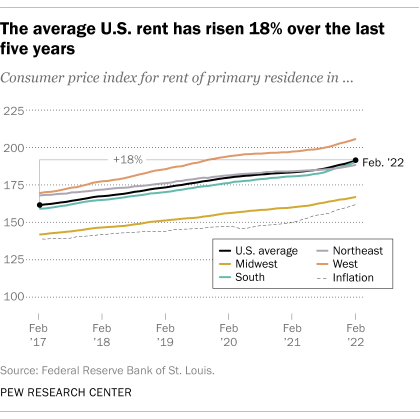

- Renters across the U.S. have seen the average rent rise 18% over the last five years, outpacing inflation, according to consumer price index data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics . Between 2017 and 2022, the cost of all goods and services increased by 16% due to inflation. During that span, the growth in rent prices exceeded inflation in every region but the Northeast: The average rent rose 21% in the West, 20% in the South and 18% in the Midwest. Rents were up 12% in the Northeast during that time. From February 2020 to February 2022, rents were up 6%, compared with a 10% inflation rate amid loosening coronavirus restrictions.

- Renters tend to skew toward the lower ends of the economic scale when it comes to income and wealth , according to data from the Federal Reserve’s 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances . That year, about six-in-ten Americans in the lowest income quartile (61%) rented their homes, as did 88% of people with net worths below the 25th percentile. People with lower incomes or net worths were more likely to be renters: Only 10.5% of people in the top income quartile, for example, were renters. Younger Americans and those who are Black or Hispanic are more likely to be renters, according to an August 2021 Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data. Roughly a third of U.S. households (35%) were headed by renters in 2021, the last year for which the U.S. Census Bureau has reliable estimates. Households headed by Black or African American adults are more likely than the population overall to rent their homes (57% rent), along with 52% of Hispanic- or Latino-led households. Around a quarter of households led by non-Hispanic White adults (26%) rent. Americans younger than 35 are far more likely to rent than those in older age groups: 62% of this age group lives in rentals compared with 39% of those ages 35 to 44, and 30% of 45- to 54-year-olds.

- Looking ahead, Americans anticipate continued rent increases in 2022, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Survey of Consumer Expectations . Americans expect that rents will increase by 10% this year – that’s larger than the expected increase in price for any other commodity, including food (9.2%), college education (9.0%) and gas (8.8%).

- Economic Conditions

- Homeownership & Renting

- Personal Finances

A look at small businesses in the U.S.

State of the union 2024: where americans stand on the economy, immigration and other key issues, americans more upbeat on the economy; biden’s job rating remains very low, online shopping has grown rapidly in u.s., but most sales are still in stores, congress has long struggled to pass spending bills on time, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

Four reasons why more public housing isn’t the solution to affordability concerns

Subscribe to the brookings metro update, jenny schuetz jenny schuetz senior fellow - brookings metro @jenny_schuetz.

January 14, 2021

With President-elect Joe Biden about to take office bolstered by Democratic control of both the House and Senate, left-leaning wonks and activists are putting together wish lists for new legislation across a myriad of issues and policy arenas.

Housing is a big one. A recent idea that’s drawing attention among housing activists—and some legislators —is to repeal the Faircloth Amendment, which bans new construction of public housing. For low-income families , the struggle to afford decent-quality, stable housing was an urgent problem long before the COVID-19 pandemic. Providing more housing support should be a priority for the incoming administration.

However, expecting local housing authorities to develop large public housing portfolios is not an effective solution. And focusing debate on the Faircloth Amendment is a red herring—a political distraction from more tangible obstacles to low-cost housing.

Below are four reasons why building more public housing is not a cure-all for the nation’s housing woes—as well as ideas for more effective solutions advocates can push for in the months ahead.

Land availability and local zoning are the main obstacles to subsidized housing

Building subsidized housing—or for that matter, market rate rental housing—is illegal in most parts of the U.S. Local zoning laws prohibit structures other than single-family detached homes on the majority of land across cities and suburbs.

Repealing the Faircloth Amendment does nothing to address this problem. Nor is this a new issue: Public housing developed from the 1950s through 1970s was largely built in poor, racially segregated neighborhoods , because that’s where government agencies could acquire land—and where middle-class white voters didn’t protest too vehemently.

Where people live—and especially where children grow up —is critical to long-term well-being, including life expectancy, health, and income. Absent any serious plan to legalize apartments in high-opportunity communities, proposals to build more public housing will only exacerbate racial and economic segregation—to the harm of low-income families.

Public agencies aren’t designed to be real estate developers

Proposals for “the government” to build public housing are often vague about which agency or department they mean. While funding for public housing originates at the federal level, the properties are operated by more than 3,300 local housing authorities across the country. And most of them don’t have recent experience with new construction—a long, complicated, risky business under the best of circumstances. Public agencies operate under more rigid rules and processes than private sector companies as well; for instance, procurement and labor requirements that make construction substantially more difficult and more expensive.

Today, nearly all new subsidized housing is built and managed by specialized nonprofit or for-profit developers . So, despite those calls for “the government” to build more housing, most housing authorities don’t have the capacity or the desire to undertake new construction projects.

High-quality subsidized housing needs a long-term commitment, not a brief flirtation

As any homeowner knows, maintaining a home in good condition requires ongoing investments of time and money. In that sense, most existing public housing properties have been slowly deteriorating for decades, plagued by water damage, mold, vermin infestations, and aging mechanical systems. In 2017, Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Secretary Ben Carson was famously trapped in a malfunctioning elevator while visiting a Miami high-rise project. With that in mind, why would housing authorities sign up to build more apartments when they already face enormous maintenance backlogs and insufficient capital funds?

The federal government’s history of infrastructure funding is like parents who buy their 16-year-old a new car, then refuse to chip in for insurance, gas, or repairs. (See also: unmet capital needs for roads, bridges, and subways .)

Writer Noah Smith recently proposed that the U.S. adopt a public housing model like Singapore, where the government builds apartments and then sells them at low prices to households. But even that doesn’t solve the problem, instead merely shifting the burden of future maintenance expenses onto households—a problem familiar to many low-income homeowners in the U.S. today.

Other types of housing subsidy give taxpayers more bang for their buck

Constructing new housing is expensive, especially in coastal metro areas where affordability problems are most acute. Developing subsidized housing is—paradoxically— more expensive than market rate housing, because of the complexity of assembling financing. New construction is also slow: It can take a decade or longer to complete subsidized apartments in tightly regulated markets.

If the goal of federal policymakers is to help as many low-income households as possible, then a strategy of newly constructed public housing is perhaps the least effective path. Increasing funds for housing vouchers or for the acquisition and rehabilitation of existing apartments through the National Housing Trust Fund would stretch subsidy dollars to cover many more households more quickly, and often in higher-opportunity neighborhoods . Shoring up the long-term physical and financial viability of existing subsidized properties—such as through HUD’s Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) program—would also be more cost effective than new construction.

In sum, helping low-income families gain access to good-quality, stable, affordable housing in high-opportunity neighborhoods should be a goal of the incoming Biden administration and the new Congress. But building more public housing is the wrong way to achieve that goal.

Related Content

Jenny Schuetz

December 8, 2020

December 9, 2020

October 26, 2020

Economic Development Housing Infrastructure

Children & Families

Brookings Metro

William A. Galston

March 25, 2024

Jenny Schuetz, Eve Devens

March 4, 2024

Alexander Conner, Sophia Campbell, Louise Sheiner, David Wessel

January 31, 2024

L.A. Housing: Racism, skyrocketing prices and now a homeless crisis

How housing has shaped the landscape of Los Angeles. And vice versa

By Yanit Mehta

AS LOS ANGELES CONSIDERS ITS FUTURE, few questions are more pressing than where its residents will live. The price of housing haunts much of the region’s vision for itself, undergirding homelessness, reinforcing the consequences of income inequality and threatening to divide the region into enclaves of rich amidst oceans of poor. As such, the topic is the subject of intense policy and academic interest, with researchers at UCLA and elsewhere examining models in other communities that may suggest ways for this area to address the cost of housing and its implications for society at large.

The dimensions of the issue are striking: California contains four of America’s five most expensive housing markets and about a quarter of the nation’s homeless. When the cost of housing is considered, certain parts of Los Angeles have some of the highest poverty rates in the country. Affordable housing is rare and difficult to encourage.

The median price for single-family homes in Los Angeles rose 22.6% to $809,750 in July, while sales increased by 6.4%. According to the NAHB/Wells Fargo Housing Opportunity Index, Los Angeles has been the least affordable large metropolitan area in America since the fourth quarter of 2020. Only 11% of families can afford a median-priced home in Los Angeles. And with a median individual income of $28,072, it would take nine years for an average Los Angeles resident to earn the sales price of that home. Nationally, the average is four years.

Income inequality in Los Angeles exacerbates an already dire housing situation. A local minimum-wage worker would have to work an average of 87 hours per week to pay the rent for an average one-bedroom apartment. With an unemployment rate of 10.4% in July 2021, too many Los Angeles residents are extremely reliant on rent moratoriums, and homelessness has increased by 16.1%. A UCLA study found that one in five renters in Los Angeles was unable to pay on time during the early months of the pandemic. In 2020, about 7% — or about 137,000 households — were unable to pay any rent at all for at least one month from May to July. This was a substantial surge when compared to the roughly 2% of renters in 2019. And the share of renters that was unable to pay part of their rent for at least one month almost doubled, from 17% to 31%.

According to a survey from the USC Sol Price Center for Social Innovation, three out of four Los Angeles households were rent-burdened, meaning they spent over 30% of household income on rent and utilities. And 48% were severely rent-burdened, spending more than half of their household income on rent and utilities. The survey also highlighted racial disparities. White and Asian households were less likely to be rent-burdened than Latino and Black households.

A history of racism in housing

Such disparities are hardly new. Housing and real estate in America have long been hotbeds for racial and economic segregation. African-American communities have repeatedly been denied the opportunity to accumulate wealth and own property. During the economic boom that followed World War II, progress in California was racially restricted by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) through practices such as redlining and exclusionary zoning. Lakewood, developed between 1949 and 1953, and Westchester, developed by Kaiser Community Homes, were FHA White-only projects.

From 1937 to 1948, more than 100 lawsuits challenged racial covenants and evicting African Americans in Los Angeles from their homes. In 1947, an African-American man was jailed for refusing to move out of his house, in violation of racial covenants. Westwood, the neighborhood bordering the UCLA campus, was notorious for such segregationist practices.

During the 1960s, after racial covenants across Los Angeles were no longer legal, real estate agents sought an opportunity to commence “blockbusting” Los Angeles suburbs such as Compton. Blockbusting was the practice where agents would instigate fear among White homeowners about the influx of African Americans into their community and the subsequent drop in property values. Once all the White homeowners had given in to their trepidations, agents would then sell the same homes to Blacks at inflated rates. State legislators and regulators condoned the practice.

These practices encouraged severe segregation in the Los Angeles area and excluded African Americans from accumulating generational wealth through home ownership, long after segregation was prohibited by law. Owning a home was easy for Whites through cheap, FHA-approved mortgages, even as those loans were routinely denied to Black applicants. The effect can still be felt in L.A.’s African-American community, where the median value of homes purchased in the 1950s would have increased since by almost tenfold. Black were denied those investment opportunities and the wealth that those homes would have allowed them to accumulate.

Today, many families, White or otherwise, still might not be able to purchase a house. That is because racial restrictions have been replaced by exorbitant prices. In contrast to the ‘50s and ‘60s, only half as many housing units have been built in the past decade, while demand has continued to grow.

That is not because Los Angeles has run out of space. Indeed, there is a misconception that Los Angeles has no more room to build new housing units. The truth is not that land is lacking, but rather that land is being misused. A majority of the neighborhoods in Los Angeles are zoned only for inefficient single-family homes. There is a high demand for housing in areas with a lot of job opportunities, notably the Westside. But a majority of the dense concentration of housing is in central L.A. and downtown, where multifamily zoning and apartment complexes are common, but jobs are more scarce.

Moreover, the areas under single-family zoning can vary drastically across neighborhoods. For instance, only 14% of the homes in Palms (11.07% African American), are single-family, whereas in Cheviot Hills (1.31% African American) 78% of the homes are single-family. Los Angeles has built an insufficient number of homes in the last 50 years. The average home is 65 to 95 years old and areas of high poverty have the oldest average home age.

Housing and the unhoused

For researchers who tackle these trends, homelessness is the most tangible form that inequality, housing shortage and poverty can take in a metropolis like Los Angeles. The county of Los Angeles would need to build 509,000 affordable units to solve the homelessness crisis. “It just seems like a fundamental contradiction that a place that strives for equity and claims to be sustainable has people who cannot afford to live anywhere,” said Stephanie Pincetl, professor at the UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability.

Pincetl urges Los Angeles to follow the examples set by cities such as Minneapolis, Berkeley and Portland, Oregon, to end single-family zoning. She acknowledges the uphill battle. “Here we are, a city that thinks of itself as so liberal, and we can’t even entertain the notion of abolishing the single-family zone,” she said. “You try floating that out there to any of the city council districts and they will just flip. I’d say Los Angeles has had almost 100 years of building under single-family zoning.”

The single-family zone may be deeply ingrained in American land-use policy, but referenda such as Proposition HHH and Measure H have targeted the issue of providing affordable housing for the homeless population of Los Angeles. Prop. HHH was a $1.2 billion bond to build approximately 10,000 units for the homeless, and Measure H was a 1⁄4-cent sales tax approved by Los Angeles County voters in March 2017 to combat homelessness. Some experts were encouraged by those votes. “In 2016, we as a people decided to tax ourselves to come up with $1.2 billion to expedite the production of permanent supportive housing in the city of L.A.,” said Michael Lens, associate professor of urban planning and public policy at UCLA. “That’s a tax-and-spend initiative on a grander scale than any other city in the country has engaged in recent decades.”

Still, the dream of an affordable housing market in Los Angeles remains elusive. About halfway into its 10-year tenure, Prop HHH has produced only 7% of the housing units it was supposed to create. Land acquisition and other factors slow down the process, but even if all 10,000 units were built, the city would still be very short of meeting its housing requirements.

“Looking forward,” Lens said, “we are still probably two to three years away from the 10,000 units being produced. We need more money for permanent supportive housing. We need a kind of HHH part two. However, I think that looks very unlikely given the public’s perception of how this has gone.”

Meanwhile, state officials are taking note of the housing crisis. On September 16, just three days after surviving the attempt to recall him from office, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed three housing-related bills. The most significant, SB 9, allows lot-splitting and enables property owners to subdivide their single-family lots and build up to four units where there was initially just one. A study by the UC Berkeley Terner Center for Housing Innovation found that SB 9 could create more than 700,000 new homes that would not be constructed under normal market conditions.

The housing shortage and the homeless crisis are inextricably linked. Predominant single-family zoning prevents the development of affordable multifamily units such as apartment complexes or smaller homes. Though some of the homeless resist housing even when it is available, others would happily accept housing if they could afford it. Still, communities resist, with far-reaching implications.

“Even if Prop. HHH and Measure H passed with majority voter support, the median homeowner does not want anything built near them at all. They might not want anything built rather far away from them in some cases,” Lens said. “If you look at what’s going on in Venice right now, I think it’s very illustrative. That community hasn’t built. I think it’s true that the population of Venice has declined in the last 30 years. You have this incredibly high demand for living there, but they haven’t been allowed to build any new housing. So housing just is getting more and more expensive. Homelessness is getting more prominent, and renters have been pushed out.”

Those are the crises that confront the future of Los Angeles.

Yanit Mehta

YANIT MEHTA is a San Francisco/Los Angeles based multimedia freelance reporter, specializing in state government and politics, environmental reporting and California housing.

Post navigation

Designs for a New Los Angeles

L.A. invites fresh thinking on how to live and work

Home — Essay Samples — Government & Politics — Public Services — Affordable Housing

Affordable Housing Essays

Affordable housing essay topics and outline examples, essay title 1: the crisis of affordable housing: causes, effects, and solutions.

Thesis Statement: This essay explores the root causes of the affordable housing crisis, its far-reaching effects on individuals and communities, and potential solutions to address this pressing issue.

- Introduction

- The Affordable Housing Crisis: Definition and Scope

- Causes of the Crisis: Economic, Policy, and Demographic Factors

- Effects on Society: Homelessness, Gentrification, and Inequality

- Solutions and Policy Measures: Affordable Housing Initiatives, Rent Control, and Housing First Programs

- Community Engagement and Advocacy: Grassroots Movements for Change

- Conclusion: The Ongoing Struggle for Affordable Housing

Essay Title 2: The Impact of Affordable Housing on Urban Development and Sustainability

Thesis Statement: This essay investigates how affordable housing policies and initiatives influence urban development, environmental sustainability, and the overall well-being of city dwellers.

- Affordable Housing and Urbanization: Trends and Challenges

- Urban Development and Affordable Housing: Mixed-Income Communities and Transit-Oriented Development

- Sustainability and Affordable Housing: Energy-Efficient Design and Green Building Practices

- Case Studies: Successful Models of Affordable and Sustainable Housing

- The Future of Affordable Housing: Smart Cities and Inclusive Urban Planning

- Conclusion: Achieving Sustainable and Affordable Urban Housing

Essay Title 3: Homelessness and the Affordable Housing Dilemma: A Comprehensive Analysis

Thesis Statement: This essay provides an in-depth analysis of the link between homelessness and the lack of affordable housing, examining the root causes, social consequences, and potential strategies to combat homelessness.

- Homelessness and Affordable Housing: The Interconnected Crisis

- Causes of Homelessness: Poverty, Mental Health, and Housing Instability

- The Vicious Cycle: How Homelessness and Affordable Housing Are Linked

- Government Initiatives: Housing First and Homelessness Reduction Programs

- Community Responses: Shelters, Outreach, and Support Services

- Conclusion: The Path Toward Ending Homelessness Through Affordable Housing

Argumentative About Homelessness

Affordable housing, poverty and homelessness in british columbia, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Increasing Urbanization and Problem of Housing The Lower Class Population: Affordable Housing

Cherry hill's strategies to provide an affordable housing in the usa, a report on affordable housing in dallas, texas, advocacy in affordable housing: the problem of the homeless, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Housing Affordability - a Matter of Concern in Australia

Analysis of the crisis of affordable housing in the film 'poverty, politics and profit', affordable housing: the increasing problem of housing in india, social issues regarding affordable housing: risks by lack and influence of coronavirus, the issue of housing crisis in modern america, relevant topics.

- Transportation

- Fire Safety

- Traffic Congestion

- Health Insurance

- Amusement Park

- Public Transport

- Electoral College

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Where Should Poor People Live?

Studies say that lower-income people do better when they live in affluent neighborhoods, but rich people don’t want them there. A few states are seeking ways around that resistance.

AMHERST, Mass.—When Peter Gagliardi first heard about an owner looking to sell an old farmhouse in this college town, he thought it seemed like an ideal place for an affordable housing complex. The property was across the street from a bus stop, near a bike path, and had access to two different sewer lines. What’s more, the city of Amherst, concerned with rising housing prices, had made a commitment to developing more affordable housing for residents in the town and region.

So Gagliardi’s nonprofit, HAPHousing, hired an architecture firm that would convert the farmhouse into 26 affordable units, a development that would blend into the bucolic landscape of ramshackle barns and rolling hills.

But when the plan for the development, called Butternut Farms, ended up in front of the community, opposition was vociferous.

“People basically said, ‘We’re in favor of affordable housing, but it shouldn’t be in a residential neighborhood,’” Gagliardi told me.

In a zoning meeting about the development, some people said their children had been bullied when they lived in rental developments and didn’t want that to happen again. Others said there would be too much traffic if the development was built. Still others worried that they would no longer be able to go into their backyards in their underwear. A young boy complained that the residents of the affordable-housing complex would run over the turtles that sometimes appeared in the neighborhood. Another resident complained that he used the property—which was private—to pick blueberries or race ATVs, and the development would put an end to all of that.

“Some of the things that were said were on the hateful side,” Gagliardi said. “It happens often, it’s the Not In My Backyard Syndrome.”

For more than a century, municipalities across the country have crafted zoning ordinances that seek to limit multi-family (read: affordable) housing within city limits. Such policies, known as exclusionary zoning, have led to increased racial and social segregation, which a growing body of work indicates limits educational and employment opportunities for low-income households.

But Massachusetts has a work-around: A state statute, called 40B, allows developers to get around exclusionary zoning and build affordable housing in communities where only a small percentage of units are considered affordable. (A few other states have similar policies.) The statute, passed in 1969 and upheld by the state’s Supreme Judicial Court in 1973, has led to the construction of 1,300 developments throughout the state, containing a total of 34,000 units of affordable housing, according to Citizens’ Housing and Planning Association , or CHAPA.

Projects built under 40B are almost always controversial: The statute was enacted in the first place because most communities outside of big cities didn’t permit multi-family housing, said Ann Verrilli, the director of research at CHAPA. Even with the statute, communities often spend millions of dollars in legal fees to try and stop the projects, Verrilli told me.

“There’s real resistance to change, resistance to development of any kind that may have school-aged kids,” she said.

The experience of developers trying to build affordable housing in Massachusetts takes on added significance now, as housing advocates wait for a decision on a landmark case in front of the Supreme Court that concerns where low-income housing projects are placed. The case, Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs v. The Inclusive Communities Project , arose when a nonprofit housing group sued Texas, arguing that the state primarily distributed tax credits for low-income housing projects in minority-dominated areas. Inclusive Communities argued that doing so perpetuated segregation and violated the Fair Housing Act, which was passed in 1968 to prevent landlords, municipalities, banks and other housing providers from discriminating on the basis of race. The Supreme Court case centers on whether this discrimination has to be intentional in order to be illegal, or whether the Fair Housing Act also seeks to prevent policies that may not be intentionally discriminatory, but that have a “disparate impact” on minorities.

Housing advocates say the parts of the Fair Housing Act being challenged in this case are important tools in ensuring the country does not become even more deeply segregated. As things are now, few states have policies in place that try and integrate communities or develop affordable housing in so-called “high opportunity” areas. And the process of bringing discrimination claims to court under the Fair Housing Act is a difficult and expensive one. The Supreme Court may yet make it even more difficult to build housing for poorer families in anywhere besides the poorest places.

“This decision will have a very profound impact on millions of Americans going forward at a time when we need every tool we can use in the arsenal of civil rights actions to make sure we live up to the aspiration of providing equal opportunity and ending discrimination in this country,” said Dennis Parker, the director of the Racial Justice Program at the ACLU, which filed an amicus brief on behalf of Inclusive Communities.

To be sure, there are reasons—besides pure racism—why a wealthy community might resist the placement of affordable housing within city limits. Many municipalities already have trouble funding schools. With more houses and families but not much more of a tax base, their budget problems could get even worse. The small Massachusetts town where I grew up, and where my brother is a public-school teacher, has been enmeshed in debate over a 40B proposal at the same time voters were asked to increase taxes so the town could continue funding schools at adequate levels.

But people who oppose 40B projects and other affordable housing developments often don’t have any complaints after the projects are built, according to research. A study out of Tufts University, “ On The Ground: 40B Controversies Before and After ” looked at some of the most controversial 40B projects in Massachusetts that were completed before June 2006. It found that the concerns of residents expressed before construction were usually not realized, and that controversy evaporated after construction wrapped up.

“This study provides significant evidence that the fears of new affordable housing development are far more myth than reality,” the study concluded.

Similarly, Princeton professor Douglas Massey studied an affordable housing development in Mount Laurel, New Jersey, that local residents had complained would lower home values, increase crime rates, and cause local taxes to rise.

He found that the development did none of those things. Many surrounding neighbors didn’t even know there was a housing project nearby.

What’s more, the lives of residents in the housing development improved markedly after they moved to the affluent suburb. An increasing amount of data seems to show that location matters just as much as income in determining a child’s likelihood of escaping poverty. As I’ve written about before, children from low-income families who move to more affluent suburbs are more likely to graduate from high school, attend four-year colleges, and have jobs than their peers who stayed in the city. And cities that have made an effort to keep schools desegregated have enjoyed less race-based strife than peer cities.

Still, affluent cities and towns often resist low-income housing projects: Despite 40B in Massachusetts, many areas of the state are falling back into the same segregation patterns that the Fair Housing Act sought to remedy nearly 50 years ago. Recent research showed , for example, that the Boston metro area has more racially concentrated areas of affluence (census tracts where 90 percent is white and wealthy) than any of America’s 20 biggest cities.

There are few states or municipalities that have laws targeted at exclusionary zoning. Three states—Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Jersey—have “exemplary interventions” to address exclusionary zoning, according to a paper by Rachel G. Bratt and Abigail Vladeck of Tufts University. Montgomery County Maryland also has a similar intervention. Other states, such as Oregon and Texas, prohibit mandatory inclusionary zoning requirements. In places that don’t strive to promote integration, segregation is likely to be prevalent.

“The market is going to work to de facto disadvantage lower-income residents,” Bratt told me. “The theory is that in order to deal with segregated patterns, you need to have proactive policies to deal with it.”

Many affordable housing units in the suburbs are a direct result of court cases, and even enforcement of those programs are lax. In 2009, Westchester County in New York signed a desegregation agreement and agreed to build and market hundreds of apartments for moderate-income minorities after a court found it had misled HUD by applying for funds that it said it would use to integrate housing, and then did the opposite. Four years later, the county had not complied with the provisions.

New Jersey is one of the few states that bars wealthy towns from excluding affordable housing, largely because of court decisions relating to the Mount Laurel case , but even those have been under attack. Governor Chris Christie attempted to disassemble the state agency overseeing affordable housing and wanted to allow municipalities to decide how much affordable housing to allow. A state appeals court blocked these attempts, but the instance points to the fact that affordable housing programs are being challenged in the few states that have them.

In Massachusetts, a group put an initiative on the ballot in 2010 that sought to repeal 40B. The coalition for repealing the law said that the statute “has destroyed communities in rural, suburban and urban neighborhoods alike, while lining the pockets of out-of-state speculators.”

The repeal effort failed, 58 percent to 42 percent, and Marc Draisen, the executive director of the Metropolitan Area Planning Council, a state planning group, says he thinks the law now has widespread support. But that doesn’t mean it has gotten any easier to build affordable housing.

Most developers don’t want to do mixed-income developments, and prefer to build market-rate buildings where they won’t have to face any community resistance or years of legal wrangling. That’s even in a state that’s seen by many as a leader in encouraging the construction of affordable housing in communities that don’t really want it.

“40B is a legal tool but it doesn’t eliminate prejudice,” Draisen told me. “Some people just do not want low-income housing in their communities.”

This prejudice won’t likely change soon, no matter what the Supreme Court decides in Texas v. Inclusive Communities . Housing advocates see some hope in an impending HUD rule, which may make it harder for communities to show this prejudice. HUD wants to stipulate that all areas receiving federal funds for low-income housing show that they are proactively promoting integration, housing experts say .

Still, the government currently lacks the resources to ensure that every community promotes integrated housing. It may be up to developers like Peter Gagliardi to continue to keep fighting to do so. And he can hold up Butternut Farms as an example of how it can work.

The development is located off a two-lane road near Hampshire College, a campus with rolling green hills, barns, and unobtrusive brick buildings. The 26 units blend right in: They are distributed in a few red barn-like structures and one yellow multi-family house, surrounded by trees and set back from the road, located up a sloping driveway.

Gagliardi first set foot on this property in 2000. The homes opened to tenants in 2011. The intervening decade was threaded with court cases, appeals, and $150,000 worth of legal costs for HAP, despite pro bono legal assistance.

The project, which involved the construction of three detached buildings of eight units of housing each and renovating the farmhouse to include two new units, violated parts of Amherst’s zoning bylaws regarding parking and housing density in residential areas. But that's the point of 40B—it allows developers to get around those laws if the housing they are building is affordable.

The local zoning board approved HAP’s application to build a 26-unit rental development in 2002, but neighbors immediately filed suit to annul the approval. When a Land Court judge upheld the permit, neighbors appealed. When the case went to the state Supreme Judicial Court, justices decided on behalf of HAP, in 2007.

“Our conclusion does not ‘needlessly infringe’ on the ‘settled property rights of abutters,’” the justices wrote. “Rather, our conclusion takes into account that the Legislature ‘has clearly delineated that point where local interests must yield to the general public need for housing.’”

A few weeks before the first tenants moved into the apartments in 2011, a rare tornado blew through nearby Springfield, destroying dozens of affordable housing units there.

“I pointed out the irony it took us 10 years to get 26 units built here, but at the same time, many times that number of units of affordable housing were destroyed in a brief time of a tornado,” Gagliardi said.

It’s a happy ending, but the problems that face Peter Gagliardi now face the nation. The country will have to grapple with how to house low-income residents in areas of opportunity, or bear more racial strife. After all, if Gagliardi had so much trouble in a liberal town in Massachusetts, a state with some of the strongest affordable-housing laws in the country, is there any reason to believe developers will be able to build affordable housing in affluent areas in the rest of the country, especially without the benefit of the Fair Housing Act?

Home / Essay Samples / Life / Personal Finance / Affordable Housing

Affordable Housing Essay Examples

Affordable housing: development, problems and the future.

'Affordable housing conveys fiscal assortment, stability, and amplifies the quality of a neighborhood'. Due to the sudden onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the core of the real estate sector of India was affected massively. However, since the final quarter of the year, the...

Chronic Homelessness: Problems with Affordable Housing

When people stay in the cycle of chronic homelessness their health and livelihood deteriorate. Therefore, the question of why people stay homeless is an important subject to look at. In Texas alone, over 25,000 individuals are experiencing homelessness on any given day. The purpose of...

Growing Affordable Housing World Crisis

According to the Wall Street Journal, the larger cities around the world, from New York to London, and Stockholm to Sydney, are making efforts to work out the growing affordable housing crisis. The data provided by Knight Frank illustrates that in the past 5 years,...

Housing Affordability: Transit Influences in the Corridor and the Waterloo Region

The intention of this report is to articulate the current housing affordability environment and how it is affected by the incoming Light Rail Transit (LRT) system or ION. The route of the LRT is further defined by an Analytical boundary to measure the properties that...

Working with Rural Communities to Build Affordable Housing

There are several diverse groups who need to co-exist in rural areas. The demand for rural housing is an issue that local councils and communities are faced with continually. Social and economic restructuring has consequentially led to rural areas being more complex places to live,...

Trying to find an excellent essay sample but no results?

Don’t waste your time and get a professional writer to help!

You may also like

- Inspiration

- Money Essays

- Legacy Essays

- Student Loan Debt Essays

- Stock Market Essays

- Heritage Essays

- Retirement Essays

- Loan Essays

- Insurance Essays

- Health Insurance Essays

- Investment Essays

samplius.com uses cookies to offer you the best service possible.By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .--> -->