Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10.2 Using Common Organizing Patterns

Learning objectives.

- Differentiate among the common speech organizational patterns: categorical/topical, comparison/contrast, spatial, chronological, biographical, causal, problem-cause-solution, and psychological.

- Understand how to choose the best organizational pattern, or combination of patterns, for a specific speech.

Twentyfour Students – Organization makes you flow – CC BY-SA 2.0.

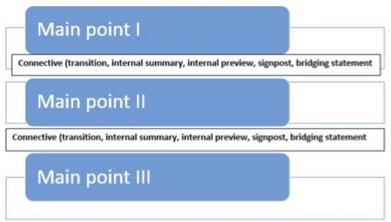

Previously in this chapter we discussed how to make your main points flow logically. This section is going to provide you with a number of organization patterns to help you create a logically organized speech. The first organization pattern we’ll discuss is categorical/topical.

Categorical/Topical

By far the most common pattern for organizing a speech is by categories or topics. The categories function as a way to help the speaker organize the message in a consistent fashion. The goal of a categorical/topical speech pattern is to create categories (or chunks) of information that go together to help support your original specific purpose. Let’s look at an example.

In this case, we have a speaker trying to persuade a group of high school juniors to apply to attend Generic University. To persuade this group, the speaker has divided the information into three basic categories: what it’s like to live in the dorms, what classes are like, and what life is like on campus. Almost anyone could take this basic speech and specifically tailor the speech to fit her or his own university or college. The main points in this example could be rearranged and the organizational pattern would still be effective because there is no inherent logic to the sequence of points. Let’s look at a second example.

In this speech, the speaker is talking about how to find others online and date them. Specifically, the speaker starts by explaining what Internet dating is; then the speaker talks about how to make Internet dating better for her or his audience members; and finally, the speaker ends by discussing some negative aspects of Internet dating. Again, notice that the information is chunked into three categories or topics and that the second and third could be reversed and still provide a logical structure for your speech

Comparison/Contrast

Another method for organizing main points is the comparison/contrast speech pattern . While this pattern clearly lends itself easily to two main points, you can also create a third point by giving basic information about what is being compared and what is being contrasted. Let’s look at two examples; the first one will be a two-point example and the second a three-point example.

If you were using the comparison/contrast pattern for persuasive purposes, in the preceding examples, you’d want to make sure that when you show how Drug X and Drug Y differ, you clearly state why Drug X is clearly the better choice for physicians to adopt. In essence, you’d want to make sure that when you compare the two drugs, you show that Drug X has all the benefits of Drug Y, but when you contrast the two drugs, you show how Drug X is superior to Drug Y in some way.

The spatial speech pattern organizes information according to how things fit together in physical space. This pattern is best used when your main points are oriented to different locations that can exist independently. The basic reason to choose this format is to show that the main points have clear locations. We’ll look at two examples here, one involving physical geography and one involving a different spatial order.

If you look at a basic map of the United States, you’ll notice that these groupings of states were created because of their geographic location to one another. In essence, the states create three spatial territories to explain.

Now let’s look at a spatial speech unrelated to geography.

In this example, we still have three basic spatial areas. If you look at a model of the urinary system, the first step is the kidney, which then takes waste through the ureters to the bladder, which then relies on the sphincter muscle to excrete waste through the urethra. All we’ve done in this example is create a spatial speech order for discussing how waste is removed from the human body through the urinary system. It is spatial because the organization pattern is determined by the physical location of each body part in relation to the others discussed.

Chronological

The chronological speech pattern places the main idea in the time order in which items appear—whether backward or forward. Here’s a simple example.

In this example, we’re looking at the writings of Winston Churchill in relation to World War II (before, during, and after). By placing his writings into these three categories, we develop a system for understanding this material based on Churchill’s own life. Note that you could also use reverse chronological order and start with Churchill’s writings after World War II, progressing backward to his earliest writings.

Biographical

As you might guess, the biographical speech pattern is generally used when a speaker wants to describe a person’s life—either a speaker’s own life, the life of someone they know personally, or the life of a famous person. By the nature of this speech organizational pattern, these speeches tend to be informative or entertaining; they are usually not persuasive. Let’s look at an example.

In this example, we see how Brian Warner, through three major periods of his life, ultimately became the musician known as Marilyn Manson.

In this example, these three stages are presented in chronological order, but the biographical pattern does not have to be chronological. For example, it could compare and contrast different periods of the subject’s life, or it could focus topically on the subject’s different accomplishments.

The causal speech pattern is used to explain cause-and-effect relationships. When you use a causal speech pattern, your speech will have two basic main points: cause and effect. In the first main point, typically you will talk about the causes of a phenomenon, and in the second main point you will then show how the causes lead to either a specific effect or a small set of effects. Let’s look at an example.

In this case, the first main point is about the history and prevalence of drinking alcohol among Native Americans (the cause). The second point then examines the effects of Native American alcohol consumption and how it differs from other population groups.

However, a causal organizational pattern can also begin with an effect and then explore one or more causes. In the following example, the effect is the number of arrests for domestic violence.

In this example, the possible causes for the difference might include stricter law enforcement, greater likelihood of neighbors reporting an incident, and police training that emphasizes arrests as opposed to other outcomes. Examining these possible causes may suggest that despite the arrest statistic, the actual number of domestic violence incidents in your city may not be greater than in other cities of similar size.

Problem-Cause-Solution

Another format for organizing distinct main points in a clear manner is the problem-cause-solution speech pattern . In this format you describe a problem, identify what you believe is causing the problem, and then recommend a solution to correct the problem.

In this speech, the speaker wants to persuade people to pass a new curfew for people under eighteen. To help persuade the civic group members, the speaker first shows that vandalism and violence are problems in the community. Once the speaker has shown the problem, the speaker then explains to the audience that the cause of this problem is youth outside after 10:00 p.m. Lastly, the speaker provides the mandatory 10:00 p.m. curfew as a solution to the vandalism and violence problem within the community. The problem-cause-solution format for speeches generally lends itself to persuasive topics because the speaker is asking an audience to believe in and adopt a specific solution.

Psychological

A further way to organize your main ideas within a speech is through a psychological speech pattern in which “a” leads to “b” and “b” leads to “c.” This speech format is designed to follow a logical argument, so this format lends itself to persuasive speeches very easily. Let’s look at an example.

In this speech, the speaker starts by discussing how humor affects the body. If a patient is exposed to humor (a), then the patient’s body actually physiologically responds in ways that help healing (b—e.g., reduces stress, decreases blood pressure, bolsters one’s immune system, etc.). Because of these benefits, nurses should engage in humor use that helps with healing (c).

Selecting an Organizational Pattern

Each of the preceding organizational patterns is potentially useful for organizing the main points of your speech. However, not all organizational patterns work for all speeches. For example, as we mentioned earlier, the biographical pattern is useful when you are telling the story of someone’s life. Some other patterns, particularly comparison/contrast, problem-cause-solution, and psychological, are well suited for persuasive speaking. Your challenge is to choose the best pattern for the particular speech you are giving.

You will want to be aware that it is also possible to combine two or more organizational patterns to meet the goals of a specific speech. For example, you might wish to discuss a problem and then compare/contrast several different possible solutions for the audience. Such a speech would thus be combining elements of the comparison/contrast and problem-cause-solution patterns. When considering which organizational pattern to use, you need to keep in mind your specific purpose as well as your audience and the actual speech material itself to decide which pattern you think will work best.

Key Takeaway

- Speakers can use a variety of different organizational patterns, including categorical/topical, comparison/contrast, spatial, chronological, biographical, causal, problem-cause-solution, and psychological. Ultimately, speakers must really think about which organizational pattern best suits a specific speech topic.

- Imagine that you are giving an informative speech about your favorite book. Which organizational pattern do you think would be most useful? Why? Would your answer be different if your speech goal were persuasive? Why or why not?

- Working on your own or with a partner, develop three main points for a speech designed to persuade college students to attend your university. Work through the preceding organizational patterns and see which ones would be possible choices for your speech. Which organizational pattern seems to be the best choice? Why?

- Use one of the common organizational patterns to create three main points for your next speech.

Stand up, Speak out Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

7.3 Organizational Patterns of Arrangement

After deciding which main points and subpoints you must include, you can get to work writing up the speech. Before you do so, however, it is helpful to consider how you will organize the ideas. There are many ways you can organize speeches, and these approaches will be different depending on whether you are preparing an informative or persuasive speech. These are referred to as organizational patterns for arranging your main points in a speech. The chronological (or temporal), topical , spatial , or causal patterns may be better suited to informative speeches, whereas the Problem-Solution, Monroe’s Motivated Sequence (Monroe, 1949), Claim-to-Proof (Mudd & Sillar, 1962), or Refutation pattern would work best for persuasive speeches. Sample outlines for persuasive speeches can be found in Chapter 17.

Chronological Pattern

When you speak about events that are linked together by time, it is sensible to engage the chronological organization pattern. In a chronological speech, main points are delivered according to when they happened and could be traced on a calendar or clock. Some professors use the term temporal to reflect any speech pattern dealing with taking the audience through time. Arranging main points in chronological order can be helpful when describing historical events to an audience as well as when the order of events is necessary to understand what you wish to convey. Informative speeches about a series of events most commonly engage the chronological style, as do many process speeches (e.g., how to bake a cake or build an airplane). Another time when the chronological style makes sense is when you tell the story of someone’s life or career. For instance, a speech about Oprah Winfrey might be arranged chronologically. In this case, the main points are arranged by following Winfrey’s life from birth to the present time. Life events (e.g., early life, her early career, her life after ending the Oprah Winfrey Show) are connected together according to when they happened and highlight the progression of Winfrey’s career. Organizing the speech in this way illustrates the interconnectedness of life events. Below you will find a way in which you can organize your main points chronologically:

Topic : Oprah Winfrey (Chronological Pattern)

Thesis : Oprah’s career can be understood by four key, interconnected life stages.

Preview : First, let’s look at Oprah’s early life. Then, we will look at her early career, followed by her years during the Oprah Winfrey show. Finally, we will explore what she is doing now.

I. Oprah’s childhood was spent in rural Mississippi, where she endured sexual abuse from family members II. Oprah’s early career was characterized by stints on local radio and television networks in Nashville and Chicago. III. Oprah’s tenure as host of the Oprah Winfrey Show began in 1986 and lasted until 2011, a period of time marked by much success. IV. Oprah’s most recent media venture is OWN: The Oprah Winfrey Network, which plays host to a variety of television shows including Oprah’s Next Chapter .

Topical Pattern

When the main points of your speech center on ideas that are more distinct from one another, a topical organization pattern may be used. In a topical speech, main points are developed according to the different aspects, subtopics or topics within an overall topic. Although they are all part of the overall topic, the order in which they are presented really doesn’t matter. For example, you are currently attending college. Within your college, there are various student services that are important for you to use while you are here. You may use the library, The Learning Center (TLC), Student Development office, ASG Computer Lab, and Financial Aid. To organize this speech topically, it doesn’t matter which area you speak about first, but here is how you could organize it.

Topic : Student Services at College of the Canyons

Thesis and Preview : College of the Canyons has five important student services, which include the library, TLC, Student Development Office, ASG Computer Lab, and Financial Aid.

I. The library can be accessed five days a week and online and has a multitude of books, periodicals, and other resources to use. II. The TLC has subject tutors, computers, and study rooms available to use six days a week. III. The Student Development Office is a place that assists students with their ID cards, but also provides students with discount tickets and other student related needs. IV. The ASG computer lab is open for students to use for several hours a day, as well as to print up to 15 pages a day for free. V. Financial Aid is one of the busiest offices on campus, offering students a multitude of methods by which they can supplement their personal finances paying for both tuition and books.

Spatial Pattern

Another way to organize the points of a speech is through a spatial speech, which arranges main points according to their physical and geographic relationships. The spatial style is an especially useful organization pattern when the main point’s importance is derived from its location or directional focus. Things can be described from top to bottom, inside to outside, left to right, north to south, and so on. Importantly, speakers using a spatial style should offer commentary about the placement of the main points as they move through the speech, alerting audience members to the location changes. For instance, a speech about The University of Georgia might be arranged spatially; in this example, the spatial organization frames the discussion in terms of the campus layout. The spatial style is fitting since the differences in architecture and uses of space are related to particular geographic areas, making location a central organizing factor. As such, the spatial style highlights these location differences.

Topic : University of Georgia (Spatial Pattern)

Thesis : The University of Georgia is arranged into four distinct sections, which are characterized by architectural and disciplinary differences.

I. In North Campus, one will find the University’s oldest building, a sprawling treelined quad, and the famous Arches, all of which are nestled against Athens’ downtown district. II. In West Campus, dozens of dormitories provide housing for the University’s large undergraduate population and students can regularly be found lounging outside or at one of the dining halls. III. In East Campus, students delight in newly constructed, modern buildings and enjoy the benefits of the University’s health center, recreational facilities, and science research buildings. IV. In South Campus, pharmacy, veterinary, and biomedical science students traverse newly constructed parts of campus featuring well-kept landscaping and modern architecture.

Causal Pattern

A causal speech informs audience members about causes and effects that have already happened with respect to some condition, event, etc. One approach can be to share what caused something to happen, and what the effects were. Or, the reverse approach can be taken where a speaker can begin by sharing the effects of something that occurred, and then share what caused it. For example, in 1994, there was a 6.7 magnitude earthquake that occurred in the San Fernando Valley in Northridge, California. Let’s look at how we can arrange this speech first by using a cause-effect pattern:

Topic : Northridge Earthquake

Thesis : The Northridge earthquake was a devastating event that was caused by an unknown fault and resulted in the loss of life and billions of dollars of damage.

I. The Northridge earthquake was caused by a fault that was previously unknown and located nine miles beneath Northridge. II. The Northridge earthquake resulted in the loss of 57 lives and over 40 billion dollars of damage in Northridge and surrounding communities.

Depending on your topic, you may decide it is more impactful to start with the effects, and work back to the causes (effect-cause pattern). Let’s take the same example and flip it around:

Thesis : The Northridge earthquake was a devastating event that was that resulted in the loss of life and billions of dollars in damage, and was caused by an unknown fault below Northridge.

I. The Northridge earthquake resulted in the loss of 57 lives and over 40 billion dollars of damage in Northridge and surrounding communities. II. The Northridge earthquake was caused by a fault that was previously unknown and located nine miles beneath Northridge.

Why might you decide to use an effect-cause approach rather than a cause-effect approach? In this particular example, the effects of the earthquake were truly horrible. If you heard all of that information first, you would be much more curious to hear about what caused such devastation. Sometimes natural disasters are not that exciting, even when they are horrible. Why? Unless they affect us directly, we may not have the same attachment to the topic. This is one example where an effect-cause approach may be very impactful.

main points are delivered according to when they happened and could be traced on a calendar or clock

main points are developed according to the different aspects, subtopics or topics within an overall topic.

useful organization pattern when the main point’s importance is derived from its location or directional focus

organizational pattern that reasons from cause to effect or from effect to cause

Introduction to Speech Communication Copyright © 2021 by Individual authors retain copyright of their work. is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7 Building and Organizing Your Speech

Learning objectives.

- Understand how to make the transition from a specific purpose to a series of main points.

- Explain how to prepare meaningful main points.

- Understand how to choose the best organizational pattern, or combination of patterns, for a specific speech.

- Understand how to use a variety of strategies to help audience members keep up with a speech’s content: internal previews, internal summaries, and signposts.

Siddie Nam – Thinking – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

In a series of ground-breaking studies conducted during the 1950s and 1960s, researchers started investigating how a speech’s organization was related to audience perceptions of those speeches. The first study, conducted by Raymond Smith in 1951, randomly organized the parts of a speech to see how audiences would react. Not surprisingly, when speeches were randomly organized, the audience perceived the speech more negatively than when audiences were presented with a speech with a clear, intentional organization. Smith also found that audiences who listened to unorganized speeches were less interested in those speeches than audiences who listened to organized speeches (Smith, 1951). Thompson furthered this investigation and found that it was harder for audiences to recall information after an unorganized speech. Basically, people remember information from speeches that are clearly organized, and they forget information from speeches that are poorly organized (Thompson, 1960). A third study by Baker found that when audiences were presented with a disorganized speaker, they were less likely to be persuaded, and saw the disorganized speaker as lacking credibility (Baker, 1965).

These three critical studies make the importance of organization very clear. When speakers are organized they are perceived as credible. When speakers are not organized, their audiences view the speeches negatively, are less likely to be persuaded, and don’t remember specific information from the speeches after the fact.

We start this chapter by discussing these studies because we want you to understand the importance of speech organization to real audiences. This chapter will help you learn organization so that your speech with have its intended effect. In this chapter, we are going to discuss the basics of organizing the body of your speech.

Determining Your Main Ideas

While speeches take many different forms, they are often discussed as having an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. The introduction establishes the topic and wets your audience’s appetite, and the conclusion wraps everything up at the end of your speech. The real “meat” of your speech happens in the body. In this section, we’re going to discuss how to think strategically about structuring the body of your speech.

We like the word strategic because it refers to determining what is essential to the overall plan or purpose of your speech. Too often, new speakers throw information together and stand up and start speaking. When that happens, audience members are left confused, and the reason for the speech may get lost. To avoid being seen as disorganized, we want you to start thinking critically about the organization of your speech. In this section, we will discuss how to take your speech from a specific purpose to creating the main points of your speech.

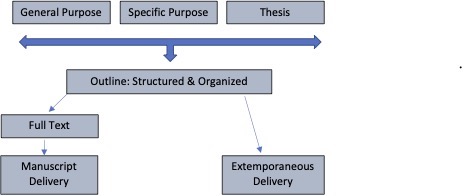

What Is Your Specific Purpose?

Before we discuss how to determine the main points of your speech, we want to revisit your speech’s specific purpose, which we discussed in detail in Chapter 4 “Topic, Purpose, and Thesis”. Recall that a speech can have one of three general purposes: to inform, to persuade, or to entertain. The general purpose refers to the broad goal for creating and delivering the speech. The specific purpose, on the other hand, starts with one of those broad goals (inform, persuade, or entertain) and then further informs the listener about the who , what , when , where , why , and how of the speech.

The specific purpose is stated as a sentence incorporating the general purpose, the specific audience for the speech, and a prepositional phrase that summarizes the topic. Suppose you are going to give a speech about using open-source software. Here are three examples (each with a different general purpose and a different audience):

In each of these three examples, you’ll notice that the general topic is the same, open-source software, but the specific purpose is different because the speech has a different general purpose and a different audience. Before you can think strategically about organizing the body of your speech, you need to know what your specific purpose is. If you have not yet written a specific purpose for your current speech, please go ahead and write one now.

From Specific Purpose to Main Points

Once you’ve written down your specific purpose, you can start thinking about the best way to turn that specific purpose into a series of main points. Main points are the key ideas you present to enable your speech to accomplish its specific purpose. In this section, we’re going to discuss how to determine your main points and how to organize those main points into a coherent, strategic speech.

Main Points are the key ideas you present to enable your speech to accomplish its specific purpose.

How Many Main Points Do I Need?

While there is no magic number for how many main points a speech should have, speech experts generally agree that the fewer the number of main points the better. First and foremost, experts on the subject of memory have consistently shown that people don’t tend to remember very much after they listen to a message or leave a conversation (Bostrom & Waldhart, 1988). While many different factors can affect a listener’s ability to retain information after a speech, how the speech is organized is an important part of that process (Dunham, 1964; Smith, 1951; Thompson, 1960). For the speeches you will be delivering in a typical public speaking class, you will usually have just two or three main points. If your speech is less than three minutes long, then two main points will probably work best. If your speech is between three and ten minutes in length, then it makes more sense to use three main points.

You may be wondering why we are recommending only two or three main points. The reason comes straight out of the research on listening. According to LeFrancois, people are more likely to remember information that is meaningful, useful, and of interest to them; different or unique; organized; visual; and simple (LeFrancois, 1999). Two or three main points are much easier for listeners to remember than ten or even five. In addition, if you have two or three main points, you’ll be able to develop each one with examples, statistics, or other forms of support. Including support for each point will make your speech more interesting and more memorable for your audience.

Narrowing Down Your Main Points

When you write your specific purpose and review the research you have done on your topic, you will probably find yourself thinking of quite a few points that you’d like to make in your speech. Whether that’s the case or not, we recommend taking a few minutes to brainstorm and develop a list of points. In brainstorming, your goal is simply to think of as many different points as you can, not to judge how valuable or vital they are. What information does your audience need to know to understand your topic? What information does your speech need to convey to accomplish its specific purpose? Consider the following example:

Now that you have brainstormed and developed a list of possible points, how do you go about narrowing them down to just two or three main ones? Remember, your main points are the key ideas that help build your speech. When you look over the preceding list, you can then start to see that many of the points are related to one another. Your goal in narrowing down your main points is to identify which individual, potentially minor points can be combined to make main points. This process is called chunking because it involves taking smaller chunks of information and putting them together with like chunks to create more fully developed chunks of information. Before reading our chunking of the preceding list, see if you can determine three large chunks out of the list (note that not all chunks are equal).

Chunking involves taking smaller chunks of information and putting them together with like chunks to create more fully developed chunks of information.

You may notice that in the preceding list, the number of subpoints under each of the three main points is a little disjointed or the topics don’t go together clearly. That’s all right. Remember that these are just general ideas at this point. It’s also important to remember that there is often more than one way to organize a speech. Some of these points could be left out and others developed more fully, depending on the purpose and audience. We’ll develop the preceding main points more fully in a moment.

Helpful Hints for Preparing Your Main Points

Now that we’ve discussed how to take a specific purpose and turn it into a series of main points, here are some helpful hints for creating your main points.

Uniting Your Main Points

Once you’ve generated a possible list of main points, you want to ask yourself this question: “When you look at your main points, do they fit together?” For example, if you look at the three preceding main points (school districts use software in their operations; what is open-source software; name some specific open-source software packages that may be appropriate for these school administrators to consider), ask yourself, “Do these main points help my audience understand my specific purpose?”

Suppose you added a fourth main point about open-source software for musicians—would this fourth main point go with the other three? Probably not. While you may have a strong passion for open-source music software, that main point is extraneous information for the speech you are giving. It does not help accomplish your specific purpose, so you’d need to toss it out.

Keeping Your Main Points Separate

The next question to ask yourself about your main points is whether they overlap too much. While some overlap may happen naturally because of the singular nature of a specific topic, the information covered within each main point should be clearly distinct from the other main points. Imagine you’re giving a speech with the specific purpose “to inform my audience about the health reasons for eating apples and oranges.” You could then have three main points: that eating fruits is healthy, that eating apples is healthy, and that eating oranges is healthy. While the two points related to apples and oranges are clearly distinct, both of those main points would probably overlap too much with the first point “that eating fruits is healthy,” so you would probably decide to eliminate the first point and focus on the second and third. On the other hand, you could keep the first point and then develop two new points giving additional support to why people should eat fruit.

Balancing Main Points

One of the biggest mistakes some speakers make is to spend most of their time talking about one of their main points, completely neglecting their other main points. To avoid this mistake, organize your speech to spend roughly the same amount of time on each main point. If you find that one of your main points is simply too large, you may need to divide that main point into two main points and consolidate your other main points into a single main point.

Let’s see if our preceding example is balanced (school districts use software in their operations; what is open-source software; name some specific open-source software packages that may be appropriate for these school administrators to consider). What do you think? The answer depends on how much time a speaker will have to talk about each of these main points. If you have an hour to speak, then you may find that these three main points are balanced. However, you may also find them wildly unbalanced if you only have five minutes to speak because five minutes is not enough time to even explain what open-source software is. If that’s the case, then you probably need to rethink your specific purpose to ensure that you can cover the material in the allotted time.

Creating Parallel Structure for Main Points

Another major question to ask yourself about your main points is whether or not they have a parallel structure. By parallel structure , we mean that you should structure your main points so that they all sound similar. When all your main points sound similar, it’s easier for your audiences to remember your main points and retain them for later. Let’s look at our sample (school districts use software in their operations; what is open-source software; name some specific open-source software packages that may be appropriate for these school administrators to consider). Notice that the first and third main points are statements, but the second one is a question. We have an example here of main points that are not parallel in structure. You could fix this in one of two ways. You could make them all questions: what are some common school district software programs; what is open-source software; and what are some specific open-source software packages that may be appropriate for these school administrators to consider. Or you could turn them all into statements: school districts use software in their operations; define and describe open-source software; name some specific open-source software packages that may be appropriate for these school administrators to consider. Either of these changes will make the grammatical structure of the main points parallel.

Parallel structure means structuring your main points so that they all sound similar.

Maintaining Logical Flow of Main Points

The last question you want to ask yourself about your main points is whether the main points make sense in the order you’ve placed them. The next section goes into more detail of common organizational patterns for speeches, but for now, we want you to think logically about the flow of your main points. When you look at your main points, can you see them as progressive, or does it make sense to talk about one first, another one second, and the final one last? If you look at your order, and it doesn’t make sense to you, you probably need to think about the flow of your main points. Often, this process is an art and not a science. But let’s look at a couple of examples.

When you look at these two examples, what are your immediate impressions of the two examples? In the first example, does it make sense to talk about history, and then the problems, and finally how to eliminate school dress codes? Would it make sense to put history as your last main point? Probably not. In this case, the main points are in a logical sequential order. What about the second example? Does it make sense to talk about your solution, then your problem, and then define the solution? Not really! What order do you think these main points should be placed in for a logical flow? Maybe you should explain the problem (lack of rider laws), then define your solution (what is rider law legislation), and then argue for your solution (why states should have rider laws). Notice that in this example you don’t even need to know what “rider laws” are to see that the flow didn’t make sense.

Using Common Organizing Patterns

Twentyfour Students – Organization makes you flow – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Previously in this chapter, we discussed how to make your main points flow logically. This section is going to provide you with organization patterns to help you create a logically organized speech. The first organization pattern we’ll discuss is categorical/topical.

Categorical/Topical

By far the most common pattern for organizing a speech is by categories or topics. The categories function as a way to help the speaker organize the message in a consistent fashion. The goal of a categorical/topical speech pattern is to create categories (or chunks) of information that go together to help support your original specific purpose. Let’s look at an example:

In this case, we have a speaker trying to persuade a group of high school juniors to apply to attend Generic University. To persuade this group, the speaker has divided the information into three basic categories: what it’s like to live in the dorms, what classes are like, and what life is like on campus. Almost anyone could take this basic speech and specifically tailor the speech to fit their own university or college. The main points in this example could be rearranged and the organizational pattern would still be effective because there is no inherent logic to the sequence of points. Let’s look at a second example:

In this speech, the speaker is talking about how to find others online and date them. Specifically, the speaker starts by explaining what Internet dating is; then the speaker talks about how to make Internet dating better for her or his audience members; and finally, the speaker ends by discussing some negative aspects of Internet dating. Again, notice that the information is chunked into three categories or topics and that the second and third could be reversed and still provide a logical structure for your speech.

Comparison/Contrast

Another method for organizing your main points is the comparison/contrast speech pattern . While this pattern lends itself easily to two main points, you can also create a third point by giving basic information about what is being compared and what is being contrasted. Let’s look at two examples; the first one will be a two-point example and the second a three-point example:

If you were using the comparison/contrast pattern for persuasive purposes, in the preceding examples, you’d want to make sure that when you show how Drug X and Drug Y differ, you clearly state why Drug X is the better choice for physicians to adopt. In essence, you’d want to make sure that when you compare the two drugs, you show that Drug X has all the benefits of Drug Y, but when you contrast the two drugs, you show how Drug X is superior to Drug Y in some way.

The spatial speech pattern organizes information according to how things fit together in physical space. This pattern is best used when your main points are oriented to different locations that can exist independently. The primary reason to choose this format is to show that the main points have specific locations. We’ll look at two examples here, one involving physical geography and one involving a different spatial order.

If you look at a basic map of the United States, you’ll notice that these groupings of states were created because of their geographic location to one another. In essence, the states create three spatial territories to explain.

Now let’s look at a spatial speech unrelated to geography.

In this example, we still have three spatial areas. If you look at a model of the urinary system, the first step is the kidney, which then takes waste through the ureters to the bladder, which then relies on the sphincter muscle to excrete waste through the urethra. All we’ve done in this example is create a spatial speech order for discussing how waste is removed from the human body through the urinary system. It is spatial because the organization pattern is determined by the physical location of each body part in relation to the others discussed.

Chronological

The chronological speech pattern places the main idea in the time order in which items appear—whether backward or forward. Here’s a simple example.

In this example, we’re looking at the writings of Winston Churchill in relation to World War II (before, during, and after). By placing his writings into these three categories, we develop a system for understanding this material based on Churchill’s own life. Note that you could also use reverse chronological order and start with Churchill’s writings after World War II, progressing backward to his earliest writings.

Cause/Effect

The causal speech pattern is used to explain cause-and-effect relationships. When you use a causal speech pattern, your speech will have two basic main points: cause and effect. In the first main point, typically you will talk about the causes of a phenomenon, and in the second main point, you will then show how the causes lead to either a specific effect or a small set of effects. Let’s look at an example.

In this case, the first main point is about the history and prevalence of drinking alcohol among Native Americans (the cause). The second point then examines the effects of Native American alcohol consumption and how it differs from other population groups.

However, a causal organizational pattern can also begin with an effect and then explore one or more causes. In the following example, the effect is the number of arrests for domestic violence.

In this example, the possible causes for the difference might include stricter law enforcement, greater likelihood of neighbors reporting an incident, and police training that emphasizes arrests as opposed to other outcomes. Examining these possible causes may suggest that despite the arrest statistic, the actual number of domestic violence incidents in your city may not be greater than in other cities of similar size.

Problem-Cause-Solution

Another format for organizing distinct main points in a clear manner is the problem-cause-solution speech pattern . In this format, you describe a problem, identify what you believe is causing the problem, and then recommend a solution to correct the problem.

In this speech, the speaker wants to persuade people to pass a new curfew for people under eighteen. To help persuade the civic group members, the speaker first shows that vandalism and violence are problems in the community. Once the speaker has demonstrated the problem, the speaker then explains to the audience that the cause of this problem is youth outside after 10:00 p.m. Lastly, the speaker provides the mandatory 10:00 p.m. curfew as a solution to the vandalism and violence problem within the community. The problem-cause-solution format for speeches generally lends itself to persuasive topics because the speaker is asking an audience to believe in and adopt a specific solution.

Speech Pattern Overview

The categorical/topical speech pattern creates categories (or chunks) of information that go together to help support your original specific purpose.

The comparison/contrast speech pattern uses main points to compare an contrast two similar objects, topics, or ideas.

The spatial speech pattern organizes information according to how things fit together in physical space.

The chronological speech pattern places the main idea in the time order in which items appear—whether backward or forward.

The causal speech pattern is used to explain cause-and-effect relationships. When you use a causal speech pattern, your speech will have two basic main points: cause and effect.

The problem-cause-solution speech pattern describes a problem, identifies what is causing the problem, and then recommends a solution to correct the problem.

Selecting an Organizational Pattern

Each of the preceding organizational patterns is potentially useful for organizing the main points of your speech. However, not all organizational patterns work for all speeches. For example, as we mentioned earlier, the biographical pattern is useful when you are telling the story of someone’s life. Some other patterns, particularly comparison/contrast, problem-cause-solution, and psychological, are well suited for persuasive speaking. Your challenge is to choose the best pattern for the particular speech you are giving.

You will want to be aware that it is also possible to combine two or more organizational patterns to meet the goals of a specific speech. For example, you might wish to discuss a problem and then compare/contrast several different possible solutions for the audience. Such a speech would thus be combining elements of the comparison/contrast and problem-cause-solution patterns. When considering which organizational pattern to use, you need to keep in mind your specific purpose as well as your audience and the actual speech material itself to decide which pattern you think will work best.

Keeping Your Speech Moving

Chris Marquardt – REWIND – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Have you ever been listening to a speech or a lecture and found yourself thinking, “I am so lost!” or “Where the heck is this speaker going?” Chances are one of the reasons you weren’t sure what the speaker was talking about was that the speaker didn’t effectively keep the speech moving. When we are reading and encounter something we don’t understand, we can reread the paragraph and try to make sense of what we’re trying to read. Unfortunately, we are not that lucky when it comes to listening to a speaker. We cannot pick up our universal remote and rewind the person. For this reason, speakers need to think about how they keep a speech moving so that audience members are easily able to keep up with the speech. In this section, we’re going to look at four specific techniques speakers can use that make following a speech much easier for an audience: transitions, internal previews, internal summaries, and signposts.

Transitions between Main Points

A transition is a phrase or sentence that indicates that a speaker is moving from one main point to another main point in a speech. Basically, a transition is a sentence where the speaker summarizes what was said in one point and previews what is going to be discussed in the next point. Let’s look at some examples:

- Now that we’ve seen the problems caused by lack of adolescent curfew laws, let’s examine how curfew laws could benefit our community.

- Thus far we’ve examined the history and prevalence of alcohol abuse among Native Americans, but it is the impact that this abuse has on the health of Native Americans that is of the greatest concern.

- Now that we’ve thoroughly examined how these two medications are similar to one another, we can consider the many clear differences between the two medications.

- Although he was one of the most prolific writers in Great Britain prior to World War II, Winston Churchill continued to publish during the war years as well.

You’ll notice that in each of these transition examples, the beginning phrase of the sentence indicates the conclusion of a period of time (now that, thus far) or main point. Table 2: Transition Words contains a variety of transition words that will be useful when keeping your speech moving.

Table 2: Transition Words

Beyond transitions, there are several other techniques that you can use to clarify your speech organization for your audience. The next sections address several of these techniques, including internal previews, internal summaries, and signposts.

Internal Previews

An internal preview is a phrase or sentence that gives an audience an idea of what is to come within a section of a speech. An internal preview works similarly to the preview that a speaker gives at the end of a speech introduction, quickly outlining what he or she is going to talk about (i.e. the speech’s three main body points). In an internal preview, the speaker highlights what he or she is going to discuss within a specific main point during a speech.

Ausubel was the first person to examine the effect that internal previews had on retention of oral information (Ausubel, 1968). When a speaker clearly informs an audience what they are going to be talking about in a clear and organized manner, the audience listens for those main points, which leads to higher retention of the speaker’s message. Let’s look at a sample internal preview:

To help us further understand why recycling is important, we will first explain the positive benefits of recycling and then explore how recycling can help our community.

When an audience hears that you will be exploring two different ideas within this main point, they are ready to listen for those main points as you talk about them. In essence, you’re helping your audience keep up with your speech.

Rather than being given alone, internal previews often come after a speaker has transitioned to that main topic area. Using the previous internal preview, let’s see it along with the transition to that main point.

Now that we’ve explored the effect that a lack of consistent recycling has on our community, let’s explore the importance of recycling for our community (transition). To help us further understand why recycling is important, we will first explain the positive benefits of recycling and then explore how recycling can help our community (internal preview).

While internal previews are definitely helpful, you do not need to include one for every main point of your speech. In fact, we recommend that you use internal previews sparingly to highlight only the main points containing relatively complex information.

Internal Summaries

Whereas an internal preview helps an audience know what you are going to talk about within a main point at the beginning, an internal summary is delivered to remind an audience of what they just heard within the speech. In general, internal summaries are best used when the information within a specific main point of a speech was complicated. To write your own internal summaries, look at the summarizing transition words in Table 2: Transition Words Let’s look at an example.

To sum up, school bullying is a definite problem. Bullying in schools has been shown to be detrimental to the victim’s grades, the victim’s scores on standardized tests, and the victim’s future educational outlook.

In this example, the speaker was probably talking about the impact that bullying has on an individual victim educationally. Of course, an internal summary can also be a great way to lead into a transition to the next point of a speech.

In this section, we have explored how bullying in schools has been shown to be detrimental to the victim’s grades, the victim’s scores on standardized tests, and the victim’s future educational outlook (internal summary). Therefore, schools need to implement campus-wide, comprehensive anti-bullying programs (transition).

While not sounding like the more traditional transition, this internal summary helps readers summarize the content of that main point. The sentence that follows than leads to the next major part of the speech, which is going to discuss the importance of anti-bullying programs.

Have you ever been on a road trip and watched the green rectangular mile signs pass you by? Fifty miles to go. Twenty-five miles to go. One mile to go. Signposts within a speech function the same way. A signpost is a guide a speaker gives their audience to help the audience keep up with the content of a speech. If you look at Table 2: Transition Words and look at the “common sequence patterns,” you’ll see a series of possible signpost options. In essence, we use these short phrases at the beginning of a piece of information to help our audience members keep up with what we’re discussing. For example, if you were giving a speech whose main point was about the three functions of credibility, you could use internal signposts like this:

- The first function of credibility is competence.

- The second function of credibility is trustworthiness.

- The final function of credibility is caring/goodwill.

Signposts are meant to help your audience keep up with your speech, so the more simplistic your signposts are, the easier it is for your audience to follow.

In addition to helping audience members keep up with a speech, signposts can also be used to highlight specific information the speaker thinks is important. Where the other signposts were designed to show the way (like highway markers), signposts that call attention to specific pieces of information are more like billboards. Words and phrases that are useful for highlighting information can be found in Table 2: Transition Words under the category “emphasis.” All these words are designed to help you call attention to what you are saying so that the audience will also recognize the importance of the information.

A transition is a phrase or sentence that indicates that a speaker is moving from one main point to another main point in a speech.

An internal preview is a phrase or sentence that gives an audience an idea of what is to come within a section of a speech.

An internal summary is delivered to remind an audience of what they just heard within the speech.

A signpost is a guide a speaker gives their audience to help the audience keep up with the content of a speech.

Ausubel, D. P. (1968). Educational psychology . New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Baker, E. E. (1965). The immediate effects of perceived speaker disorganization on speaker credibility and audience attitude change in persuasive speaking. Western Speech, 29 , 148–161.

Bostrom, R. N., & Waldhart, E. S. (1988). Memory models and the measurement of listening. Communication Education, 37 , 1–13.

Dunham, J. R. (1964). Voice contrast and repetition in speech retention (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from: http://etd.lib.ttu.edu/theses .

LeFrancois, G. R. (1999). Psychology for teaching (10th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Smith, R. G. (1951). An experimental study of the effects of speech organization upon attitudes of college students. Speech Monographs, 18 , 292–301.

Thompson, E. C. (1960). An experimental investigation of the relative effectiveness of organizational structure in oral communication. Southern Speech Journal, 26 , 59–69.

Stand up, Speak out Copyright © 2017 by Josh Miller; Marnie Lawler-Mcdonough; Megan Orcholski; Kristin Woodward; Lisa Roth; and Emily Mueller is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

36 Organizational Styles

After deciding which main points and sub-points you must include, you can get to work writing up the speech. Before you do so, however, it is helpful to consider how you will organize the ideas. From presenting historical information in chronological order as part of an informative speech to drawing a comparison between two ideas in a persuasive speech to offering up problems and solutions, there are many ways in which speakers can craft effective speeches. These are referred to as organizational styles, or templates for organizing the main points of a speech.

Chronological

When you speak about events that are linked together by time, it is sensible to engage the chronological organization style. In a chronological speech , main points are delivered according to when they happened and could be traced on a calendar or clock. Arranging main points in chronological order can be helpful when describing historical events to an audience as well as when the order of events is necessary to understand what you wish to convey. Informative speeches about a series of events most commonly engage the chronological style, as do many demonstrative speeches (e.g., how to bake a cake or build an airplane). Another time when the chronological style makes sense is when you tell the story of someone’s life or career. For instance, a speech about Oprah Winfrey might be arranged chronologically (see textbox). In this case, the main points are arranged by following Winfrey’s life from birth to the present time. Life events (e.g., birth, her early career, her life after ending the Oprah Winfrey Show) are connected together according to when they happened and highlight the progression of Winfrey’s career. Organizing the speech in this way illustrates the interconnectedness of life events.

Oprah Winfrey (Chronological Arrangement)

Thesis : Oprah’s career can be understood by four key, interconnected life stages.

I. Oprah’s childhood was spent in rural Mississippi, where she endured sexual abuse from family members.

II. Oprah’s early career was characterized by stints on local radio and television networks in Nashville and Chicago.

III. Oprah’s tenure as host of the Oprah Winfrey Show began in 1986 and lasted until 2011, a period of time marked by much success.

IV. Oprah’s most recent media venture is OWN: The Oprah Winfrey Network, which plays host to a variety of television shows including Oprah’s Next Chapter .

Doing the best at this moment puts you in the best place for the next moment. – Oprah Winfrey

When the main points of your speech center on ideas that are more distinct from one another, a topical organization style may be engaged. In a topical speech , main points are developed separately and are generally connected together within the introduction and conclusion. In other words, the topical style is crafted around main points and sub-points that are mutually exclusive but related to one another by virtue of the thesis. It makes sense to use the topical style when elements are connected to one another because of their relationship to the whole. A topical speech about the composition of a newspaper company can be seen in the following textbox. The main points are linked together by the fact that they are all a part of the same business. Although they are related in that way, the topical style illustrates the ways in which the four different departments function apart from one another. In this example, the topical style is a good fit because the four departments are equally important to the function of the newspaper company.

Composition of a Newspaper Company (Topical Arrangement)

Thesis : The newspaper has four primary departments.

I. The advertising department sells display advertisements to local and national businesses.

II. The editorial department produces the written content of the newspaper, including feature stories.

III. The production department lays out the pages and manages pre- press work such as distilling the pages and processing colors.

IV. The business department processes payments from advertisers, employee paperwork, and the bi-weekly payroll.

Another way to organize the points of a speech is through a spatial speech , which arranges main points according to their physical and geographic relationships. The spatial style is an especially useful organization style when the main point’s importance is derived from its location or directional focus. In other words, when the scene or the composition is a central aspect of the main points, the spatial style is an appropriate way to deliver key ideas. Things can be described from top to bottom, inside to outside, left to right, north to south, and so on. Importantly, speakers using a spatial style should offer commentary about the placement of the main points as they move through the speech, alerting audience members to the location changes. For instance, a speech about The University of Georgia might be arranged spatially; in this example, the spatial organization frames the discussion in terms of the campus layout. The spatial style is fitting since the differences in architecture and uses of space are related to particular geographic areas, making location a central organizing factor. As such, the spatial style highlights these location differences.

University of Georgia (Spatial Arrangement)

Thesis : The University of Georgia is arranged into four distinct sections, which are characterized by architectural and disciplinary differences.

I. In North Campus, one will find the University’s oldest building, a sprawling tree- lined quad, and the famous Arches, all of which are nestled against Athens’ downtown district.

II. In West Campus, dozens of dormitories provide housing for the University’s large undergraduate population and students can regularly be found lounging outside or at one of the dining halls.

III. In East Campus, students delight in newly constructed, modern buildings and enjoy the benefits of the University’s health center, recreational facilities, and science research buildings.

IV. In South Campus, pharmacy, veterinary, and biomedical science students traverse newly constructed parts of campus featuring well-kept landscaping and modern architecture.

Comparative

When you need to discuss the similarities and differences between two or more things, a comparative organizational pattern can be employed. In comparative speeches , speakers may choose to compare things a couple different ways. First, you could compare two or more things as whole (e.g., discuss all traits of an apple and then all traits of an orange). Second, you could compare these things element by element (e.g., color of each, smell of each, AND taste of each). Some topics that are routinely spoken about comparatively include different cultures, different types of transportation, and even different types of coffee. A comparative speech outline about eastern and western cultures could look like this.

Eastern vs. Western Culture (Comparison Arrangement)

Thesis : There are a variety of differences between Eastern and Western cultures.

I. Eastern cultures tend to be more collectivistic.

II. Western cultures tend to be more individualistic.

III. Eastern cultures tend to treat health issues holistically.

IV. Western cultures tend to treat health issues more acutely.

In this type of speech, the list of comparisons, which should be substantiated with further evidence, could go on for any number of main points. The speech could also compare how two or more things are more alike than one might think. For instance, a speaker could discuss how singers Madonna and Lady Gaga share many similarities both in aesthetic style and in their music.

Problem-Solution

Sometimes it is necessary to share a problem and a solution with an audience. In cases like these, the problem-solution speech is an appropriate way to arrange the main points of a speech. One familiar example of speeches organized in this way is the political speeches that presidential hopefuls give in the United States. Often, candidates will begin their speech by describing a problem created by or, at the very least, left unresolved by the incumbent. Once they have established their view of the problem, they then go on to flesh out their proposed solution. The problem- solution style is especially useful when the speaker wants to convince the audience that they should take action in solving some problem. A political candidate seeking office might frame a speech using the problem-solution style (see textbox).

Presidential Candidate’s Speech (Problem-Solution Arrangement)

Thesis : The US energy crisis can be solved by electing me as president since I will devote resources to the production of renewable forms of energy.

I. The United States is facing an energy crisis because we cannot produce enough energy ourselves to sustain the levels of activity needed to run the country. (problem)

II. The current administration has failed to invest enough resources in renewable energy practices. (problem)

III. We can help create a more stable situation if we work to produce renewable forms of energy within the United States. (solution)

IV. If you vote for me, I will ensure that renewable energy creation is a priority. (solution)

The difference between what we do and what we are capable of doing would suffice to solve most of the world’s problems. – Mahatma Gandhi

This example illustrates the way in which a problem-solution oriented speech can be used to identify both a general problem (energy crisis) and a specific problem (incumbent’s lack of action). Moreover, this example highlights two kinds of solutions: a general solution and a solution that is dependent on the speaker’s involvement. The problem-solution speech is especially appropriate when the speaker desires to promote a particular solution as this offers audience members a way to become involved. Whether you are able to offer a specific solution or not, key to the problem-solution speech is a clear description of both the problem and the solution with clear links drawn between the two. In other words, the speech should make specific connections between the problem and how the solution can be engaged to solve it.

Similar to a problem-solution speech, a causal speech informs audience members about causes and effects that have already happened. In other words, a causal organization style first addresses some cause and then shares what effects resulted. A causal speech can be particularly effective when the speaker wants to share the relationship between two things, like the creation of a vaccine to help deter disease. An example of how a causal speech about a shingles vaccine might be designed follows:

As the example illustrates, the basic components of the causal speech are the cause and the effect. Such an organizational style is useful when a speaker needs to share the results of a new program, discuss how one act led to another, or discuss the positive/negative outcomes of taking some action.

Shingles Speech (Cause-Effect Arrangement)

Thesis : The prevalence of the disease shingles led to the invention of a vaccine.

- Shingles is a disease that causes painful, blistering rashes in up to one million Americans every year. (cause)

- In 2006, a vaccine for shingles was licensed in the United States and has been shown to reduce the likelihood that people over 60 years old will get shingles. (effect)

Every choice you make has an end result. – Zig Ziglar

Choosing an organizational style is an important step in the speechwriting process. As you formulate the purpose of your speech and generate the main points that you will need to include, selecting an appropriate organizational style will likely become easier. The topical, spatial, causal, comparative and chronological methods of arrangement may be better suited to informative speeches, whereas the refutation pattern may work well for a persuasive speech. Additionally, Chapter 16 offers additional organization styles suited for persuasive speeches, such as the refutation speech and Monroe’s Motivated Sequence. [1] Next, we will look at statements that help tie all of your points together and the formal mode of organizing a speech by using outlines.

- Monroe, A. H. (1949). Principles and types of speech. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman and Company. ↵

Fundamentals of Public Speaking Copyright © by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

17 Organizational Patterns

Learning Objectives

- Decide on an effective organizational pattern.

Now that we have gotten this far, we need to consider how we will organize our material. There are several ways you can organize your speech content to ensure your information is easy for your audience to follow. The following video explains different organizing patterns. Note that some of the organizing patterns are better for information speech and some are better for persuasive speeches.

Organizational Patterns

After deciding which main points and sub-points you must include, you can get to work writing up the speech. Before you do so, however, it is helpful to consider how you will organize the ideas. There are many ways you can organize speeches, and these approaches will be different depending on whether you are preparing an informative or persuasive speech. These are referred to as organizational patterns for arranging your main points in a speech. The chronological, topical, spatial, or causal patterns may be better suited to informative speeches, whereas the Problem-Solution, Monroe’s Motivated Sequence (Monroe, 1949) would work best for persuasive speeches.

Chronological Pattern

When you speak about events that are linked together by time, it is sensible to engage the chronological organization pattern. In a chronological speech, the main points are delivered according to when they happened and could be traced on a calendar or clock. Some professors use the term temporal to reflect any speech pattern dealing with taking the audience through time. Arranging main points in chronological order can be helpful when describing historical events to an audience as well as when the order of events is necessary to understand what you wish to convey. Informative speeches about a series of events most commonly engage the chronological style, as do many process speeches (e.g., how to bake a cake or build an airplane). Another time when the chronological style makes sense is when you tell the story of someone’s life or career. For instance, a speech about Oprah Winfrey might be arranged chronologically. In this case, the main points are arranged by following Winfrey’s life from birth to the present time. Life events (e.g., early life, her early career, her life after ending the Oprah Winfrey Show) are connected together according to when they happened and highlight the progression of Winfrey’s career. Organizing the speech in this way illustrates the interconnectedness of life events. Below you will find a way in which you can organize your main points chronologically:

Topic : Oprah Winfrey (Chronological Pattern)

Thesis : Oprah’s career can be understood by four key, interconnected life stages.

Preview : First, let’s look at Oprah’s early life. Then, we will look at her early career, followed by her years during the Oprah Winfrey show. Finally, we will explore what she is doing now.

I. Oprah’s childhood was spent in rural Mississippi, where she endured sexual abuse from family members II. Oprah’s early career was characterized by stints on local radio and television networks in Nashville and Chicago. III. Oprah’s tenure as host of the Oprah Winfrey Show began in 1986 and lasted until 2011, a period of time marked by much success. IV. Oprah’s most recent media venture is OWN: The Oprah Winfrey Network, which plays host to a variety of television shows including Oprah’s Next Chapter .

Topical Pattern

When the main points of your speech center on ideas that are more distinct from one another, a topical organization pattern may be used. In a topical speech, main points are developed according to the different aspects, subtopics, or topics within an overall topic. Although they are all part of the overall topic, the order in which they are presented really doesn’t matter. For example, you are currently attending college. Within your college, there are various student services that are important for you to use while you are here. You may use the library, The Learning Center (TLC), Student Development office, ASG Computer Lab, and Financial Aid. To organize this speech topically, it doesn’t matter which area you speak about first, but here is how you could organize it.

Topic : Student Services at College of the Canyons

Thesis and Preview : College of the Canyons has five important student services, which include the library, TLC, Student Development Office, ASG Computer Lab, and Financial Aid.

I. The library can be accessed five days a week and online and has a multitude of books, periodicals, and other resources to use. II. The TLC has subject tutors, computers, and study rooms available to use six days a week. III. The Student Development Office is a place that assists students with their ID cards, but also provides students with discount tickets and other student related needs. IV. The ASG computer lab is open for students to use for several hours a day, as well as to print up to 15 pages a day for free. V. Financial Aid is one of the busiest offices on campus, offering students a multitude of methods by which they can supplement their personal finances paying for both tuition and books.

Spatial Pattern

Another way to organize the points of a speech is through a spatial speech, which arranges the main points according to their physical and geographic relationships. The spatial style is an especially useful organization pattern when the main point’s importance is derived from its location or directional focus. Things can be described from top to bottom, inside to outside, left to right, north to south, and so on. Importantly, speakers using a spatial style should offer commentary about the placement of the main points as they move through the speech, alerting audience members to the location changes. For instance, a speech about The University of Georgia might be arranged spatially; in this example, the spatial organization frames the discussion in terms of the campus layout. The spatial style is fitting since the differences in architecture and uses of space are related to particular geographic areas, making the location a central organizing factor. As such, the spatial style highlights these location differences.

Topic : University of Georgia (Spatial Pattern)

Thesis : The University of Georgia is arranged into four distinct sections, which are characterized by architectural and disciplinary differences.

I. In North Campus, one will find the University’s oldest building, a sprawling treelined quad, and the famous Arches, all of which are nestled against Athens’ downtown district. II. In West Campus, dozens of dormitories provide housing for the University’s large undergraduate population and students can regularly be found lounging outside or at one of the dining halls. III. In East Campus, students delight in newly constructed, modern buildings and enjoy the benefits of the University’s health center, recreational facilities, and science research buildings. IV. In South Campus, pharmacy, veterinary, and biomedical science students traverse newly constructed parts of campus featuring well-kept landscaping and modern architecture.

Causal Pattern

A causal speech informs audience members about causes and effects that have already happened with respect to some condition, event, etc. One approach can be to share what caused something to happen, and what the effects were. Or, the reverse approach can be taken where a speaker can begin by sharing the effects of something that occurred, and then share what caused it. For example, in 1994, there was a 6.7 magnitude earthquake that occurred in the San Fernando Valley in Northridge, California. Let’s look at how we can arrange this speech first by using a cause-effect pattern:

Topic : Northridge Earthquake

Thesis : The Northridge earthquake was a devastating event that was caused by an unknown fault and resulted in the loss of life and billions of dollars of damage.

I. The Northridge earthquake was caused by a fault that was previously unknown and located nine miles beneath Northridge. II. The Northridge earthquake resulted in the loss of 57 lives and over 40 billion dollars of damage in Northridge and surrounding communities.

Depending on your topic, you may decide it is more impactful to start with the effects, and work back to the causes (effect-cause pattern). Let’s take the same example and flip it around:

Thesis : The Northridge earthquake was a devastating event that was that resulted in the loss of life and billions of dollars in damage, and was caused by an unknown fault below Northridge.

I. The Northridge earthquake resulted in the loss of 57 lives and over 40 billion dollars of damage in Northridge and surrounding communities. II. The Northridge earthquake was caused by a fault that was previously unknown and located nine miles beneath Northridge.

Why might you decide to use an effect-cause approach rather than a cause-effect approach? In this particular example, the effects of the earthquake were truly horrible. If you heard all of that information first, you would be much more curious to hear about what caused such devastation. Sometimes natural disasters are not that exciting, even when they are horrible. Why? Unless they affect us directly, we may not have the same attachment to the topic. This is one example where an effect-cause approach may be very impactful.

Organizational patterns help you to organize your thoughts and speech content so that you are able to develop your ideas in a way that makes sense to the audience. Having a solid idea of which organization pattern is best for your speech will make your speech writing process so much easier!

Key Takeaways

- Speech organizational patterns help us to arrange our speech content in a way that will communicate our ideas clearly to our audience.

- Different organizational patterns are better for different types of speeches and topics.

- Some organizational patterns are better for informative speeches: Chronological, spatial, topical, and narrative.

- Although cause-effect and problem-solution can be used for an informative speech, use these patterns with caution as they are better used for persuasive speeches.

Introduction to Speech Communication by Individual authors retain copyright of their work licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.