Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 03 October 2017

Grenfell Tower fire – a tragic case study in health inequalities

- R. G. Watt 1

British Dental Journal volume 223 , pages 478–480 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

19k Accesses

7 Citations

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Dental epidemiology

- Dental public health

Highlights that the recent Grenfell Tower fire has raised fundamental policy questions about safety regulation in the UK.

Suggests that, seen through a public health perspective, this tragic incident is ultimately about social inequality in the UK.

Suggests that as general and oral health inequalities are caused by the same underlying factors, the lessons learnt from this tragedy have relevance to oral health professionals committed to tackling social inequalities.

At least 80 people died in the recent Grenfell Tower fire in Kensington and Chelsea, West London. This incident has provoked much anger, debate and reflection on how such a tragedy could happen in London, one of the richest cities in the world. Seen through a public health lens, this disaster is ultimately about social inequality in modern Britain. Kensington and Chelsea is a deeply divided community, where many billionaires and very wealthy people live cheek by jowl with poor and disenfranchised people struggling to make ends meet. It is therefore not a surprise that such a terrible incident should happen in this socially unequal setting where very stark health inequalities already exist. This paper explores some of the broader underlying factors that may have contributed to this tragedy, the political determinants of health. As these factors are linked to both general and oral health inequalities, the lessons learnt from this incident have direct relevance and salience to oral health professionals concerned about tackling social inequalities in contemporary society.

Margaret Whitehead's classic definition of health inequalities as health differences that are 'avoidable, unjust, unfair and unacceptable', 1 perfectly describes the deaths caused by the recent Grenfell Tower fire in West London. On 12 June 2017 a fire started by a faulty fridge freezer in a fourth floor flat in Grenfell Tower, a 24-storey tower block in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea turned into an inferno in the space of minutes trapping many families, with at least 80 people believed to be dead – although the final death toll is expected to be much higher.

Following the tragic fire many commentators have been asking how such a terrible event could happen in twenty-first century London, one of the richest cities in the world. The UK used to be world renowned for its stringent health and safety record. What has gone so badly wrong for this event, the worst fire in the UK for over a century, to happen? The government has appointed Sir Martin Moore-Bick to lead a public inquiry into the fire and the police are conducting a criminal investigation, but these may take months or even years to report. There is a groundswell of pressure from the surviving victims, the local community and many others for answers to why this tragedy happened. Key questions that need answers include: What were the underlying causes behind this incident? How did public services respond to the unfolding events on 12th June? What are the longer-term policy implications to ensure that this terrible event is not repeated? It has been argued that this disaster is ultimately about social inequalities in modern Britain – a tragic tale of political ineptitude and neglect, disenfranchised and marginalised families ignored by those in positions of power and authority, and public services unable to cope with the immediate and longer-term consequences of the fire. 2 , 3

Although it is important to investigate the potential role of the recently placed cladding and other technical issues in the fire, it is essential that the broader underlying factors of this tragedy are investigated and uncovered. Several years ago the British Medical Journal banned the word 'accidents' in any of its scientific publications, preferring instead the use of the term injury. 4 This was principally because the word 'accident' strongly implied that the event leading to the injury happened by chance, at random. Major incidents like the Grenfell Tower fire do not happen by chance, they are caused by a web of inter-related factors that ultimately lead to the tragedy – the political determinants or as Rose (2008) described, 'the causes of the causes'. 5

The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea is the richest borough in London with a staggeringly high mean income of £116,000 per year. 6 It is home to many billionaires (hence the extremely high mean income) and the average cost of a property is over £2 million. However, it is also characterised by stark economic and social inequality. Wards in the north of the borough, including Notting Barnes (the ward where Grenfell Tower is located), have higher rates of low income households, child poverty and registered homeless people compared to the London average. Although overall life expectancy is higher than the England average, shocking health inequalities exist in this area of West London. For example, life expectancy is 16 years lower for men living in the most deprived areas of Kensington and Chelsea compared to the least deprived. 7 Although the personal details of the victims are not, as yet fully available, it is very apparent that the families affected were mostly from disadvantaged and marginalised backgrounds, including many recent migrants and refugees. National data have shown that injury-related deaths are strongly associated with levels of deprivation, particularly deaths caused by fires. Children living in households where parents never worked or are long-term unemployed are 38 times more likely to die in a fire than children living in families with professional parents. 8 The death toll in Grenfell Tower provides yet more evidence on the grim statistics of deprivation, disadvantage and mortality.

Kensington and Chelsea local authority have been heavily criticised for many years as being out of touch, detached and elitist in nature, only concerned with the interests of their wealthy residents. Although £8.7 million was spent on refurbishing Grenfell Tower in 2016, almost immediately, residents voiced concerns about the fire risks in the newly refurbished building. The Grenfell Action Group, acting on behalf of the local residents complained to the council on ten separate occasions over concerns of the fire hazards in the tower block. All these warnings were totally ignored by those in positions of power. No one listened to the residents' fears. The local population were therefore powerless in their attempts to improve the safety of their homes. Although the council has amassed a budget reserve in excess of £274 million, during the building refurbishment a decision was made to use cheaper quality cladding material to save an estimated £290,000. This is the cladding material that is suspected of rapidly spreading the fire on the exterior of the building due to its combustible nature – a material that is not permitted for use in tall buildings in Germany and many other European countries. Major concerns have also been voiced about the council's immediate response to the unfolding events on 12 June. As the magnitude of the tragedy became apparent and hundreds of surviving victims and residents were in urgent need of help, both practical and emotional, the local politicians seemed incapable of providing the necessary assistance and support. It took days before an organised and effective response was mobilised. Eventually, amid a media frenzy the Conservative leader of the council, Nicholas Paget-Brown, took responsibility for the failings of the council and resigned with immediate effect.

It has also emerged that although fire crews from the London Fire Brigade managed to bravely save the lives of over 250 people from the inferno, the London fire service did not have a sufficiently tall ladder to deal with a fire in a 24-storey tower block and had to borrow a 42 m firefighting platform from Surrey fire service, causing a critical delay in their response and management of the fire. It seems bizarre in the extreme that London, with so many tall buildings and many others under construction, does not have access to the appropriate equipment to deal with fires in tower blocks.

How have national policies contributed to the events in Grenfell Tower? For decades governments of all political persuasions have failed to address the housing crisis in the UK. There is an acute shortage of affordable housing, particularly in the south of England where the costs of the private rental sector are beyond the reach of many. The right to buy policy introduced by Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s has greatly diminished the social housing stock across the country and very few new social housing developments have since been built. Increasingly, social housing has been perceived as the 'dumping ground' for the most marginalised and disadvantaged in society, and the residents vilified as 'scroungers' and social outcasts – see the portrayal of social housing residents in television programmes such as 'Benefits Street'. This combined with a backlash against a health and safety 'culture' has seen a steady relaxation of building regulations and controls. Deregulation, privatisation and the outsourcing of public services are all part of a political neo-liberal ideology that has influenced government policy in many countries across the globe over the last 30 years.

Government regulation is perceived as bad, interfering and stifling red tape. Freed up market forces are seen as the way forward in encouraging enterprise and innovation. In addition, since 2010, austerity measures introduced by the coalition government and continued by the Conservative administration have seen dramatic reductions in local authority budgets including housing inspection and maintenance services. Cuts to the legal aid budget have also had a significant effect in greatly limiting access of legal support for low-income people. With appropriate legal representation perhaps the safety concerns of the Grenfell Tower residents would have been taken seriously by those in positions of authority and the necessary improvements made to avoid the tragic events in June. All these policies have undoubtedly played a role in creating a deeply fractured and unequal society where the most vulnerable and disadvantaged live in unsafe conditions.

The dramatic events at Grenfell Tower may seem very remote and unconnected to oral health. However, the underlying causes and pathways for both general and oral health inequalities are shared. 9 What lessons, therefore, need to be learnt from this tragedy? Seen through a public health lens, the Grenfell fire has provided stark evidence on the social and political determinants of health inequalities – the direct impact of the conditions of living on health, and the need for appropriate upstream policies, including action by national and local government to deal with the housing crisis in this country. 10 , 11 Giving marginalised and disadvantaged people a voice so that their concerns and views are heard by those in positions of power is essential. Political processes and decision making also needs to be more open and accountable so that the needs of local populations, often very diverse backgrounds, are heard and responded to.

Speaking truth to power is a fundamental tenet of public health advocacy. In August 2016 the Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA) for Kensington and Chelsea focused on housing as a local public health priority, 12 but publication of this report clearly did not avert the subsequent disaster one year later. Public health professionals and other agencies need to be empowered and independent to challenge threats to the health of their local populations. Lastly, the underlying importance of effective regulation and legislation in improving the conditions of daily living needs to be recognised and strengthened. Housing, work places, schools, hospitals and other settings of modern life all need to comply with up-to-date and stringent regulations to ensure their safety and the promotion of health and the well-being of the people living, working and using these settings. This is important for the whole population but particularly for the most vulnerable in society.

The Grenfell Tower fire has been a wake-up call for British society in many different respects. Urgent changes are needed to ensure that the lessons learnt are acted upon to avoid such a tragedy ever happening again.

Whitehead M . The concepts and principles of equity and health. Int J Health Serv. 1992; 22 : 429–445.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

McKee M . Grenfell Tower fire: why we cannot ignore the political determinants of health. BMJ 2017; 357 : j2966. 10.1136/bmj.j2966.

Chakrabortty A . Over 170 years after Engels, Britain is still a country that murders its poor. The Guardian. 2017. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/jun/20/engels-britain-murders-poor-grenfell-tower (accessed August 2017).

Davis R, Pless B . BMJ bans 'accidents'. BMJ 2001; 322 : 1320–1321.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rose G . Rose's strategy of preventive medicine . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Book Google Scholar

London's Poverty Profile. New analysis of poverty in Kensington and Chelsea. [Internet]. Trust for London, New Policy Institute [cited 2017 Jul 19]. Available at http://www.londonspovertyprofile.org.uk/news/updated-profile-of-kensington/ (accessed August 2017).

Public Health England. Kensington and Chelsea Health Profile 2016. UK Government. Available at http://www.psnc.org.uk/kensington-chelsea-and-westminster-lpc/wp-content/uploads/sites/73/2017/05/2016.pdf (accessed 12 September 2017).

Edwards P, Green J, Roberts I, Lutchmun M . Deaths from injury in children and employment status in family: analysis of trends in class specific death rates. BMJ 2006; 333 : 119–121.

Marmot M, Bell R . Social determinants and dental health. Adv Dent Res 2011; 23 : 201–206.

Marmot M . Fair society, healthy lives: strategic review of health inequalities in England post – 2010. London: Department of Health, 2010.

Sheiham A . Improving oral health for all: focusing on determinants and conditions. Health Educ J 2000; 59 : 64–76.

Article Google Scholar

City of Westminster and Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Housing support and care: integrated solutions for integrated challenges. Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA), 2016.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, 1–19 Torrington Place, London, WC1E 6BT

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to R. G. Watt .

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Watt, R. Grenfell Tower fire – a tragic case study in health inequalities. Br Dent J 223 , 478–480 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.785

Download citation

Accepted : 10 August 2017

Published : 03 October 2017

Issue Date : 13 October 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.785

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- For authors

- Browse by collection

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 12, Issue 9

- Systematic review of the effectiveness of the health inequalities strategy in England between 1999 and 2010

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7011-4116 Ian Holdroyd 1 ,

- Alice Vodden 1 , 2 ,

- Akash Srinivasan 3 ,

- Isla Kuhn 4 ,

- Clare Bambra 5 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8033-7081 John Alexander Ford 1

- 1 Department of Public Health and Primary Care , University of Cambridge , Cambridge , UK

- 2 University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust , London , UK

- 3 Imperial College London Faculty of Medicine , South Kensington Campus , London , UK

- 4 Medical Library, School of Clinical Medicine , University of Cambridge , Cambridge , UK

- 5 Newcastle University Population Health Sciences Institute , Newcastle upon Tyne , UK

- Correspondence to Dr John Alexander Ford; jf653{at}medschl.cam.ac.uk

Objectives The purpose of this systematic review is to explore the effectiveness of the National Health Inequality Strategy, which was conducted in England between 1999 and 2010.

Design Three databases (Ovid Medline, Embase and PsycINFO) and grey literature were searched for articles published that reported on changes in inequalities in health outcomes in England over the implementation period. Articles published between January 1999 and November 2021 were included. Title and abstracts were screened according to an eligibility criteria. Data were extracted from eligible studies, and risk of bias was assessed using the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions tool.

Results The search strategy identified 10 311 unique studies, which were screened. 42 were reviewed in full text and 11 were included in the final review. Six studies contained data on inequalities of life expectancy or mortality, four on disease-specific mortality, three on infant mortality and three on morbidities. Early government reports suggested that inequalities in life expectancy and infant mortality had increased. However, later publications using more accurate data and more appropriate measures found that absolute and relative inequalities had decreased throughout the strategy period for both measures. Three of four studies found a narrowing of inequalities in all-cause mortality. Absolute inequalities in mortality due to cancer and cardiovascular disease decreased, but relative inequalities increased. There was a lack of change, or widening of inequalities in mental health, self-reported health, health-related quality of life and long-term conditions.

Conclusions With respect to its aims, the strategy was broadly successful. Policymakers should take courage that progress on health inequalities is achievable with long-term, multiagency, cross-government action.

Trial registration number This study was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42021285770).

- public health

- health policy

- quality in health care

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-063137

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is the first study to synthesise all published studies and grey literature on the health inequalities strategy conducted in England from 1999 to 2010.

This study used a broad search strategy of peer-reviewed and grey literature.

The retrospective nature of studies and lack of counterfactual means that causal claims as to the effect of the strategy cannot easily be made. This resulted in an increased risk of bias of studies.

Introduction

The pandemic has exacerbated societal health inequalities, with higher numbers of COVID-19 related cases and deaths in areas of higher socioeconomic disadvantage and among minority ethnic groups. 1 2 In England, the COVID-19 mortality rate for those under 65 was 3.7× greater in the most deprived 10% of local areas compared with the least deprived. Age-standardised COVID-19 mortality rates were more than twice as high in the most deprived 10% of areas compared with the least. 2

Knowledge of the existence of health inequalities is not new. The first major UK publication describing health inequalities was the Black report in 1980, although health inequalities had been described and debated in the academic literature for decades before that. It was not until 1997, with a newly elected government, that health inequalities became a policy priority. The government commissioned a health inequalities review, subsequently published in 1998 as the Acheson report, and committed itself to implement the evidence-based policy recommendations. 3 Subsequently, a wide-ranging national health inequalities strategy was implemented, with various strategies and aims updated over time. This was the first and most extensive international attempt to address health inequalities through a widespread programme of cross-government action.

Two national documents set out the health inequalities strategy. First, ‘Reducing health inequalities: an action report’ was published in 1999 in response to the Acheson report. It described a wide variety of policies designed to reduce health inequalities: both more ‘downstream’ initiatives, such as increased National Health Service (NHS) funding or the establishment of a National Institute for Clinical Excellence, and more ‘upstream’ policies, such as a national minimum wage, the new deal for employment and increased funding for schools, housing and transport. 4 Second, ‘Tackling health inequalities: a Program for Action’ was published in 2003. 5 It set out 82 cross-departmental commitments, along with 12 headline indicators of the key areas to be monitored. Again, these commitments included a range of ‘upstream’ and ‘downstream’ policies. Other studies have previously summarised the strategy. 6–8 The strategy involved a wide range of policy actions across different sectors. These included large increases in levels of public spending on a range of social programmes (such as the introduction of the Child Tax Credit; SureStart Children’s Centres), the introduction of the national minimum wage, area-based interventions such as the Health Action Zones and Neighbourhood Renewal funds and a substantial increase in expenditure on the NHS. The latter was targeted at more deprived neighbourhoods when, after 2001, a ‘health inequalities weighting’ was added to the way in which NHS funds were geographically distributed, so that areas of higher deprivation received more funds per head to reflect higher health need. 9

The programme for action included two national targets: (1) by 2010, to reduce by at least 10% the gap in infant mortality between routine and manual groups and the population as a whole and (2) by 2010, to reduce by at least 10% the gap between the fifth of areas with the lowest life expectancy at birth and the population as a whole. The ‘areas with the lowest life expectancy at birth and the population as a whole’ were defined by later documents as the ‘Spearhead areas’. 10–12 These 70 local authority areas were identified as being the worst performing local authorities associated with three or more of: male and female life expectancy at birth, cancer and cardiovascular disease mortality rates for the under 75s and Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 2004 scores. These targets were based on relative, rather than absolute, inequalities. 12 13 This is important as debate exists as to which of these is the most appropriate measure of inequality. 3 14 15 Absolute inequalities measure the numerical gap between groups, while relative inequalities measure the percentage difference between groups.

One major criticism of health inequalities research and policy is that there has been too much effort put into describing the problem, rather than finding solutions. The National Health Inequalities Strategy in England 1999–2010 provides a key international example of the latter. It is a high-profile international case study of long term multifaceted government action. Discussions to date of the effects of the strategy have been polarised, with some prominent commentators arguing that it failed, 8 while others have asserted that it was effective. 16 17 This is partly because early evaluations of this health inequalities strategy suggested that it had failed to reach its targets and that inequalities may have increased during this period. 8 10 16 18 However, subsequent research found that this period was associated with a reduction in health inequalities. 6 9 19–21 As governments around the world consider how to respond to inequalities compounded by the pandemic, here we present a systematic review of the studies assessing the effectiveness of this health inequalities strategy.

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with established methodology 22 and reported in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement. 23 This systematic review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42021285770).

Search strategy and selection criteria

Three electronic databases (Ovid Medline, Ovid Embase and Ebsco PsycINFO) were systematically searched from January 1999 to November 2021. The search terms were based in part on previous literature, which identified key search terms to identify studies investigating inequality and inequity 24 and the UK. 25 Online supplemental table 1 presents the search terms. After removing duplicate records, abstracts and titles were screened according to the eligibility criteria by two researchers (IH and AS) using the software Rayyan by December 2021. Discrepancies were resolved by a third researcher (JAF). Each researcher cross screened 20% of the abstracts and titles of the other to ensure accuracy. Three conflicts arose, which were resolved after discussion. A detailed grey literature search of the UK Government Web Archives, specific websites (such as the King’s Fund) and a broad search using an internet search engine (Google) was used. Relevant citations of included studies were also screened.

Supplemental material

Inclusion criteria were:

Studies assessing the impact of the health inequalities strategy in England between 1999 and 2010 on inequality in health outcomes in England.

Any form of quantitative study.

Studies reporting primary research.

Studies in any language.

Exclusion criteria were:

Studies whose methodology make it impossible to draw conclusions about the impact of the strategy.

Studies that reported non-health inequalities.

Earlier editions of included reports.

The full text of all articles screened as meeting the eligibility criteria or possibly meeting the criteria were reviewed. The following information was independently extracted from each study by two authors (IH and AV): first author, year of publication, aim, design, data sources, time period of analysis, population, health inequalities measured, main findings and risk of bias. The main outcomes of interest were absolute or relative changes in socioeconomic inequalities in life expectancy and infant mortality in the population of England between 1999 and 2010 to reflect the aims of the strategy. All results compatible with each outcome domain were sought from each study. Secondary outcomes included changes to socioeconomic inequalities in mortality, comorbidities or self-reported health.

Quality assessment

Risk of bias was assessed at a study level using the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool, which assesses the risk of bias across seven domains. One author (IH) undertook the risk of bias assessment, and this was double checked by a second author (AS or AV) with disagreements resolved by a third (JAF).

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the design or execution of this study. Nor were members of the public.

Due to the small number of studies with a large amount of data heterogeneity, it was deemed inappropriate to perform a meta-analysis. Instead, studies were synthesised narratively.

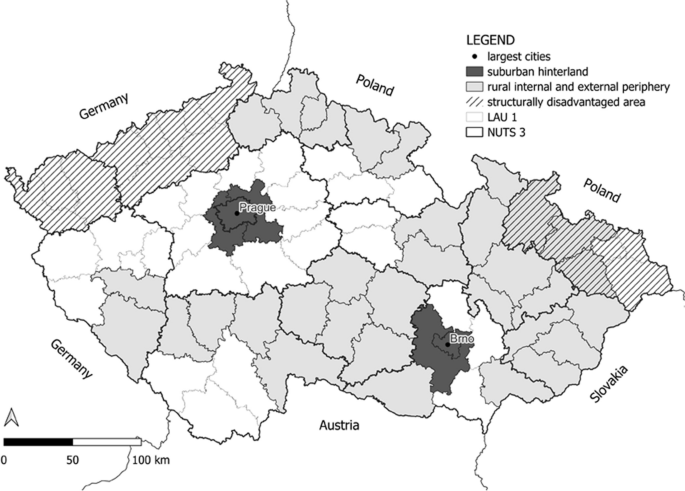

After removal of duplicates, the search identified 10 311 unique records. Forty-two were reviewed in full text, and 11 were included in the final review. A flow diagram of the screening and selection process can be found in figure 1 . Six studies contained data on inequalities of life expectancy or mortality, 6 7 9 10 12 19 three on disease-specific mortality, 10 12 26 three on infant mortality 10 13 21 and three on morbidities. 7 20 27 Six studies investigated geographical health inequalities, four investigated health inequalities at an individual level and one had statistics from both measures. Measures of socioeconomic status included income, living in a spearhead area, deprivation, occupation, social class and education. Data were collected between 1983 and 2017 ( table 1 ). Results from these papers are summarised in table 2 . Table 3 shows the risk of bias of each study across seven domains.

- View inline

Study characteristics

Study findings

Risk of bias – ROBINS-I tool

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Study selection process.

Life expectancy, all-cause mortality and disease-specific mortality

Six studies reported data on life expectancy or mortality. Two earlier studies reported a widening of inequalities in life expectancy with one showing narrowing of mortality inequalities. The four more recent studies showed a narrowing of inequalities.

Two early government reports showed widening of life expectancy inequalities and mixed results for mortality inequalities. ‘Tackling Health Inequalities: 2007 Status Report on the Programme for Action’ used Office for National Statistics (ONS) data based on life estimates made using the 2006 census. It compared life expectancy in spearhead areas and the rest of the country. While life expectancy had increased for both spearhead and non-spearhead areas, absolute and relative inequalities between them had increased between 1995–1997 and 2004–2006. 10 The second reported ONS data up to and including 2010. 12 Compared with the 1995–1997 baseline, the absolute and relative gap in life expectancy between spearhead areas and England as a whole increased by 2008–2010.

Four later published studies found that inequalities had narrowed. The first study by Barr and colleagues 9 compared individuals living in the fifth most deprived areas to those living in the fifth least deprived areas. The authors found that inequalities of healthcare amenable mortality, defined as mortality from causes that would be prevented provided appropriate access to high-quality healthcare, narrowed between 2001 and 2011. Absolute inequalities for men and women fell with 85% of the change explained by redistributive resource allocation changes between areas. The relative gap narrowed for males and females. However, the authors found that absolute or relative inequalities of mortality not amenable to healthcare failed to change noticeably between 2001 and 2011. 9

The second study by Barr and colleagues 6 investigated geographical inequalities between 1983 and 2015 using ONS data based on the 2011 census, rather than 2006, which informed earlier government publications. They analysed trends in the absolute difference of life expectancy and mortality in the 20% most deprived local authorities compared with the rest of England. Supplementary analysis compared life expectancy in spearhead and non-spearhead areas. The authors identified breakpoints to account for the lag between implementation and outcomes. Both socioeconomic inequalities and inequalities between spearhead and non-spearhead areas in life expectancy for men and women statistically significantly increased year-on-year before the strategy and decreased during the time of the strategy, with no evidence that this decrease continued after the strategy. Relative socioeconomic inequalities in mortality fell year-on-year throughout the strategy for both men and women and increased before and after the strategy for men. Further analysis showed that the gap in life expectancy between spearhead areas and the rest of the country did not decrease until after 2005. Relative socioeconomic inequalities in life expectancy widened before and after the strategy period and narrowed during it. The authors found that using population estimates using the 2006 census caused an artificial increase in life expectancy inequalities compared with 2011 estimates.

Hu and colleagues 7 compared data from the health survey for England to similar surveys done in other European countries. They investigated trends in inequalities of all-cause mortality between those with high (tertiary) education and the rest of the country. The gap narrowed more significantly in 2000–2010 compared with 1990–2000 in England.

While aforementioned studies, analysing differences between the most and least deprived areas, are important concerning the strategies aims, they fail to describe the change in the social gradient across the whole of the population. Buck and Maguire 19 examined the relationship between area-based income deprivation and life expectancy, comparing data from 1999 to 2003 to 2006–2010. The authors found improved life expectancy for all levels of deprivation but a greater improvement in more deprived areas. It was noted that both unemployment and older people’s deprivation played a particularly important role in determining differences in life expectancy between areas.

Three studies reported changes in inequalities in disease-specific mortality. Two government documents examined inequalities in mortality due to cancer between spearhead areas and England as a whole from 1995 to 1997 to 2006–2008 and 2008–2010 using ONS data. By 2006–2008, absolute inequalities fell, without a change in relative inequalities. 10 By 2010, the absolute gap had fallen further, with an increase in the relative gap. 12 Absolute inequalities in mortality due to circulatory disease decreased by 2006–2008, but relative inequalities widened. By 2008–2010, there was a further decrease in absolute but an increase in relative inequalities. Exarchakou and colleagues 26 reported inequalities of 1-year survival rate following a diagnosis of one of the 24 most common cancers between 1996 and 2013. They investigated the absolute difference between individuals living in the fifth most and fifth least deprived areas. The gap narrowed in only 6 of 20 cancers in men and 2 of 21 cancers in women and widened for three cancers (two in women and one in men). One final study examined inequalities in road accident causality in the fifth most deprived local authority districts areas compared with England as a whole. 10 The absolute gap decreased between 1998 and 2006.

Infant mortality

Three studies reported changes in the infant mortality rate. Initial reporting using ONS data from 2004 to 2006 found that inequalities had widened between routine plus manual groups and the population as a whole compared with the 1997–1999 baseline. 10 A later report found that by 2008–2010, inequalities had narrowed compared with the baseline. 13 Robinson and colleagues 21 calculated the infant mortality rate in 323 lower tier local authorities between 1983 and 2017 to investigate changes in inequalities between the 20% most deprived areas and the rest of the country. Absolute inequality increased year on year before the strategy and decreased during it. A non-significant increase was seen after the strategy ended. Relative inequalities marginally decreased during the time of the strategy, in contrast to an increase that was seen before and after the strategy period.

Morbidities

Three studies reported on morbidities using Health Survey of England data. Specifically, these studies investigated self-assessed health, health-related quality of life, mental health and long-term health. The Health Survey of England contains data collected from a nationally representative sample of those residing at private residential addresses and has been carried out since 1991. 28 Around 8000 adults and 2000 children take part in the survey each year.

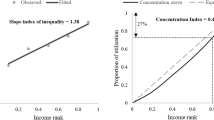

Mixed results were found concerning self-reported health. Between 1996 and 2009, the probability of reporting bad or very bad health remained relatively constant for those in the highest social class but increased for those in lower social classes. 27 When comparing those with high and low education, there was no significant difference in inequality trends between 2000 and 2010 compared with 1990–2000. Additionally, there was no significant difference in the change of these trends between these periods compared with three European countries. 7 Costa Font and colleagues 20 measured inequalities in self-reported health using concentration indices, whereby a high result indicates more inequality. Equalised household income was used to measure inequality across the whole population. In contrast to the two aforementioned studies, they reported a fall in the concentration index between 1997 and 2007, indicating a reduction in inequality.

Health-related quality of life did not change between social classes from 1996 to 2008. 27 When assessed by a concentration index comparing different household incomes, inequalities of long-term health problems increased between 1997 and 2007. 20 There was no significant change in the trend of inequalities of long-term health problems by education in 2000–2010 compared with 1990–2000. Nor was there a significant difference in the change in trend in England compared with three European countries. 7 While mental health improved in all social classes between 1997 and 2009, it did so more for individuals in higher social classes. 27

Principle findings

There is evidence that the strategy met the infant mortality target, while the life expectancy target was reached for men but not women. Absolute health inequalities in life expectancy, mortality, infant mortality and multiple major causes of death reduced. Less evidence is available concerning relative inequalities. More recent data suggest that relative socioeconomic inequalities in life expectancy and infant mortality narrowed. Relative inequalities of mortality narrowed between the fifth most deprived areas and the country as a whole, but not between the fifth most and fifth least deprived areas. The only data available on disease-specific conditions suggest an increase in relative inequalities. This may be due to a lack of newly published studies, using more recent census data and sampling from the later years of the strategy being available as it is for life expectancy and infant mortality. The difference may also be due to the statistical relationship whereby relative inequalities may increase as a result of a fall in absolute inequalities. 29 30 There was a lack of change or worsening of change for inequalities in mental health, health-related quality of life and long-term conditions. This lack of change or increased inequality for self-reported health measures may be due to multiple reasons. As all studies used the same survey, with data collected shortly after the 2008 financial crash, perceptions of economic security may have altered results. It may be that self-reported measures are more resilient to change. Alternatively, small changes in categorically assessed self-assessed measures may be less easily observed compared with life expectancy and infant mortality that are continuous measures. Health inequalities were found to have narrowed more consistently when measured between geographical areas rather than between individuals. This may be due to longer follow-up periods in many of the studies that were measured at a geographical level, extending beyond the immediate aftermath of the banking crises. Alternatively, it could have been caused by the redistributive resource allocation changes that occurred between areas. 9

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study to collate and synthesise all evidence of the first international attempt at a cross-government strategy to address health inequalities. We used an extensive search strategy with robust screening, data extraction and quality assessment processes. We included peer-reviewed articles and grey literature, including documents published at the time and identified through the UK government archives.

The main limitation is that the studies included are retrospective using either time-trend or before and after methods. All of the studies have a high risk of bias due to deviations from intended interventions. This was predominantly because of the lack of a robust counterfactual that makes it difficult to unpick the impact of the strategy against the impact of other factors, such as broad economic growth before the financial crash in 2008. These limitations are common to any attempt to assess the impact of national policy; however, considering the breadth and ambition of the strategy it is disappointing that more comprehensive evaluations or data are not available. The strategy’s wide-ranging nature does however allow many of these factors to be considered a part of it rather than as a confounding factor. For example, the large decrease in poverty rates, especially in children 31 and pensioners, 32 may both have contributed. Additionally, not every abstract was double screened. However, 40% of abstracts were cross checked to ensure consistency, and only three discrepancies arose, none of which were included in the review.

The included articles use different measures that make direct comparisons impossible, for example, comparing the most deprived areas to either the least deprived areas or the rest of the population and using individual-level measures of socio-economic status (eg, occupation) or area-based measures (eg, IMD). Morbidity data are based on self-reported measures within a nationally representative survey, rather than chronic disease registers.

As indicated by guidance, absolute and relative inequalities were included. 14 33 This aligns with existing guidance and debate both from those who argue that absolute inequalities are the more important measure for policymakers 3 and others who support the idea that relative inequalities are also of significant importance. 34

What this research means

A lack of progress on health inequalities, despite policy priority, can lead to a sense of fatalism and powerlessness to effect change. These findings are therefore important because they show that with sustained cross-government action, progress on health inequalities is possible. It is particularly encouraging that improvements were made in both of the areas that the strategy predominantly set out to improve: inequalities in life expectancy and infant mortality.

These results are even more encouraging when considering that they came from a strategy that was far from perfect. Critics have noted various points about the strategy, for example, that it was insufficiently based on reliable evidence, 8 18 35 36 flawed in delivery, 8 16 18 insufficiently focused on the wider determinants of health 16 34 37 and that efforts may not have been large enough. 8 34 38

Earlier findings consistently showed no improvement in life expectancy inequalities, yet later results were more positive. This may be due to a lag period between the implementation of the strategy of interventions and changes in health outcomes. Certain initiatives would take considerably longer to impact inequalities in life expectancy, such as reducing childhood poverty, compared with more downstream factors, such as blood pressure control. Alternatively, it may be due to more accurate and up-to-date data, such as the 2011 census. Importantly, this shows that sufficient time is needed between implementation and measuring outcomes.

Implications for policy and research

Governments around the world are taking steps to address health inequalities, particularly in light of the growing evidence of an unequal pandemic. 39 For example, the UK government has committed to a programme of ‘levelling up’ regional inequalities and setting out new legislation to address health inequalities. This review suggests that it is possible to reduce health inequalities through long-term cross-government action, which was wide reaching both in terms of government departments and across the life course. Most encouragingly with respect to current government aims, geographical health inequalities especially narrowed. The strategy was supported by significant increases in both funding and reform of public services, of which only one has continued. Since the end of the strategy period, public services internationally, but particularly in the UK, have experienced reduced funding as a result of austerity policies from 2010 onwards. In the UK, this has particularly impacted on local authorities, social security, children’s services and, until the pandemic, to the NHS. Indeed, there is evidence that from 2010 onwards (and before the unequal impact of the pandemic) the improvements in health inequalities under the English strategy have reversed with, for example, increasing inequalities in infant mortality rates 40 and falling life expectancy in the most deprived areas. 41 Considerable investments in these services would be necessary to recreate a proactive attempt to tackle the social determinants of health inequalities.

The strategy used relative measures of inequality. Absolute measures are easier to change, making them appealing to policymakers as progress can be more easily proven. The goals were based on long-term changes in life expectancy and infant mortality rather than shorter term changes in measures such as blood pressure and heart rate. These were appropriate for the strategy given the wide-ranging, cross-departmental approach that aimed to target determinants of ill health. The fact that long-term, ambitious health inequalities targets require a cross-departmental approach can be of benefit to policy makers. They can provide rationale and strengthen the argument for a wide range of potentially transformative policies that may otherwise fail to be enacted due to a lack of political support. Goals were based on changes between the most and least deprived areas, rather than changes in the societal gradient in health. This again would be an easier target for policymakers to achieve. The government’s current targets, through the ‘levelling up’ programme are less ambitious than the strategy’s. 42 Only an absolute narrowing in life expectancy and well-being is aimed for, rather than the 10% change targeted by the strategy. Additionally, the absolute gap in life expectancy by area is measured between the top and bottom 10% rather than 20%.

Arguably more policy priority should have been given to reducing the gap in morbidities as the data fail to show a convincing narrowing of inequalities of self-reported health, mental health, health-related quality of life and long-term conditions.

More research is needed to unpick the active ingredients and exact initiatives that were most effective during the strategy. This should start with a more detailed understanding of which diseases drove the reduction in life expectancy and a broader understanding of how the wider determinants of health such as housing, income and education may have impacted changes in infant mortality, mortality and life expectancy.

In summary, this review found some evidence that the 1999–2010 cross-government health inequalities strategy led to a reduction in the absolute inequalities in life expectancy, mortality, infant mortality and major causes of death. While the impact on relative inequalities is less clear, there seemed to be a narrowing of relative inequalities in at least life expectancy and infant mortality. The national targets relating to life expectancy were met for men, but not women, and were achieved for infant mortality. Policymakers should take courage that progress on health inequalities is achievable with long-term, multiagency, cross-government action. These findings are especially pertinent at present times whereby many governments are aiming to use postpandemic recovery as an opportunity to build back better.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication.

Not applicable.

- Riordan R ,

- Ford J , et al

- Suleman M ,

- Sonthalia S ,

- Department of Health

- Higgerson J ,

- Whitehead M

- van Lenthe FJ ,

- Judge K , et al

- Mackenbach JP

- Costa Font J ,

- Hernández-Quevedo C ,

- Robinson T ,

- Norman PD , et al

- Higgins J ,

- McKenzie JE ,

- Bossuyt PM , et al

- Uphoff EP ,

- Power M , et al

- Hudson T , et al

- Exarchakou A ,

- Belot A , et al

- Maheswaran H ,

- Mindell J ,

- Biddulph JP ,

- Hirani V , et al

- Meersman SC , et al

- Department for Work and Pensions Department for Education

- Office for National Statistics

- Mackenbach JP ,

- Garthwaite K , et al

- Macintyre S ,

- Chalmers I ,

- Horton R , et al

- Hunter DJ ,

- Tannahill C , et al

- Taylor-Robinson D ,

- Wickham S , et al

- Raleigh VS ,

- Goldblatt P

- HM Government

Supplementary materials

Supplementary data.

This web only file has been produced by the BMJ Publishing Group from an electronic file supplied by the author(s) and has not been edited for content.

- Data supplement 1

Twitter @ilk21

Contributors JAF conceptualised the study. JAF and IH drafted the protocol, and IK and AV provided comments. IK developed the searches with the support of IH and JAF. IH and AS screened the titles and abstract and were supported by JAF. IH and JF screened the full text articles. IH, AS and AV extracted and checked the extraction. IH wrote the first draft of the manuscript. JAF, IK, CB, AS and AV redrafted. All authors approved the final version. JAF is the guarantor.

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient and public involvement Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Open access

- Published: 23 March 2023

Why and how has the United Kingdom become a high producer of health inequalities research over the past 50 years? A realist explanatory case study

- Lucinda Cash-Gibson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3292-5684 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Eliana Martinez-Herrera 1 , 2 , 4 &

- Joan Benach 1 , 2 , 5

Health Research Policy and Systems volume 21 , Article number: 23 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

2208 Accesses

1 Citations

18 Altmetric

Metrics details

Evidence on health inequalities has been growing over the past few decades, yet the capacity to produce research on health inequalities varies between countries worldwide and needs to be strengthened. More in-depth understanding of the sociohistorical, political and institutional processes that enable this type of research and related research capacity to be generated in different contexts is needed. A recent bibliometric analysis of the health inequalities research field found inequalities in the global production of this type of research. It also found the United Kingdom to be the second-highest global contributor to this research field after the United States. This study aims to understand why and how the United Kingdom, as an example of a “high producer” of health inequalities research, has been able to generate so much health inequalities research over the past five decades, and which main mechanisms might have been involved in generating this specific research capacity over time.

We conducted a realist explanatory case study, which included 12 semi-structured interviews, to test six theoretical mechanisms that we proposed might have been involved in this process. Data from the interviews and grey and scientific literature were triangulated to inform our findings.

We found evidence to suggest that at least four of our proposed mechanisms have been activated by certain conditions and have contributed to the health inequalities research production process in the United Kingdom over the past 50 years. Limited evidence suggests that two new mechanisms might have potentially also been at play.

Conclusions

Valuable learning can be established from this case study, which explores the United Kingdom’s experience in developing a strong national health inequalities research tradition, and the potential mechanisms involved in this process. More research is needed to explore additional facilitating and inhibiting mechanisms and other factors involved in this process in this context, as well as in other settings where less health inequalities research has been produced. This type of in-depth knowledge could be used to guide the development of new health inequalities research capacity-strengthening strategies and support the development of novel approaches and solutions aiming to tackle health inequalities.

Growing evidence demonstrates that avoidable and unfair systematic differences in health outcomes (i.e. health inequalities [HI]) [ 1 ] exist within and between countries [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Research on HI is essential to be able to assess the characteristics and trends of HI and to establish their causes, and can be used to inform the design and implementation of policy interventions aiming to reduce HI in different settings. A strong capacity to produce HI research at the local, national and global levels is therefore crucial to be able to understand and work towards addressing HI, yet this capacity does not exist worldwide [ 5 , 6 ]. Despite notable advances and global efforts to invest in and strengthen such research capacities, further concerted efforts are still needed. In this paper, the term HI is used according to Whitehead and Dahlgren’s [ 1 ] conceptualization, and refers to all of the following terms: health disparities, HI, health inequities and social inequalities in health.

A recent bibliometric analysis of the global HI scientific production (1966–2015) identified significant inequalities within this research production worldwide [ 5 ]. The study also found the United Kingdom to be the second-highest global contributor to the HI research field after the United States [ 5 ]. Such findings raise important questions: why and how are some countries able to produce more research on this topic than others, and what types of mechanisms have been involved? Additionally, since scientific research output is generally considered as a proxy indication of research capacity, what do these diverse research outcomes suggest about HI research capacities in different settings? Furthermore, as an example of a “high HI researcher producer”, why and how has the United Kingdom been able to produce such a large volume of HI research during the last 50 years? Which key determinants and causal mechanisms might have been involved in generating this strong national HI research production and capacity over time?

In line with realist inquiries, our study therefore aims to generate valuable causal insights and knowledge about which mechanisms have worked in the United Kingdom, how, and under what conditions, for it to become a high HI research producer. Specifically, we aim to (i) understand why and how the United Kingdom has produced a high volume of HI research over the past five decades; (ii) test six theoretical mechanisms that we propose might have been involved in this national HI research production process over time and (iii) identify evidence to support, refute or refine these hypotheses.

We conducted a realist explanatory case study, which included 12 semi-structured interviews with key informants. Data from the interviews were then triangulated with grey and scientific literature in order to strengthen our overall findings. Explanatory case studies attempt to explain causal relationships, and answer “how” and “why” questions. Realism is a strand of philosophy of science, and realist models of explanation attempt to consider the role of structure and human agency in social change. They aim to reveal the nature of hidden underlying causal forces (i.e. mechanisms) that are sensitive to different contextual conditions, and which can create series of changes that generate certain outcomes of interest [ 7 , 8 , 9 ].

We selected our “unique case of interest” (i.e. an example of a high producer of HI scientific research) based on previous findings of a recent bibliometric analysis [ 5 ]. Combining Pawson and Tilley’s [ 7 ] and Shankardass et al.’s [ 8 ] methodologies for realist evaluations and realist explanatory case studies, we developed our own realist explanatory case study protocol that explains how to design and implement realist explanatory case studies [ 9 ]. The study design included developing (i) a guiding abstract conceptual model based on existing literature on HI research production processes [ 10 ], (ii) a guiding context + mechanism = outcome (CMO) configuration and (iii) the rationale for proposing our theoretical mechanisms that we aim to test and refine through the case study [ 9 ]. The purpose of the guiding CMO configuration is to simplify the main process of interest (i.e. HI research production process) down to its key attributes [ 8 ]. This serves to “artificially isolate” the key combinations of factors that are embedded in specific historical, political and institutional contexts within the United Kingdom (C) and likely interacted over time to activate certain mechanisms (M), which collectively led to our outcome of interest (O) (i.e. high HI research production) [ 7 ].

Through our realist explanatory case study, we aimed to test six theoretical causal mechanisms (M1–M6) that we proposed based on a review of multidisciplinary literature. We hypothesized that these mechanisms might have been involved in this process, with the intention of refining them based on our study findings [ 7 , 9 ]. Table 1 shows the CMO configuration that was created to guide our realist explanatory case study in the United Kingdom. (See the study protocol [ 9 ] for further details on how to design and implement realist explanatory case studies, and the rationale for proposing these six theoretical mechanisms.)

Through the semi-structured interviews, we aimed to understand how and why the United Kingdom’s HI research field was initiated and how it has evolved over the past few decades. Study participants were initially identified from the published HI literature [ 5 ] and invited via email for interview if they met the following inclusion criteria: (i) senior researcher working or having worked in United Kingdom during the last five decades, of any gender; and (ii) has produced (and published) research on HI while working in United Kingdom during the last five decades. Out of the 13 people invited to interview, one potential participant declined to be interviewed.

Interview questions were developed using a political economy perspective and in line with our guiding abstract conceptual model, CMO configuration and supporting literature on HI research production and research capacities (refer to [ 9 , 11 ] for details about the conceptual models). These research questions were tested in a pilot interview conducted by two of the authors and then adjusted accordingly to establish the core set of key questions for the rest of interviews. Participants were asked the following:

Their professional background and initial motivation for working in the field of HI (to establish positionality)

Why and how has the United Kingdom produced such a high volume of HI research over the past five decades, and why and how have certain institutions in the United Kingdom produced more HI research than others?

What key historical, political, research and institutional events might have been important for the initiation and development of the HI research field in the United Kingdom over the past five decades, and why?

Which factors have been important for developing national capacity (human and technical research infrastructure) to conduct HI research in the United Kingdom and why?

Have individual or institutional ideologies and values been important for the process of generating our outcome of interest? If so, why?

What role have research networks played in the HI research field over time?

Twelve interviews were conducted until saturation was attained [ 12 ]. In terms of the profiles of the study participants, the majority of the participants were male ( n = 7) and professors ( n = 11) who worked in different institutions and cities throughout the United Kingdom and had been trained in a range of disciplines, such as political and social sciences, medicine, public health and epidemiology, statistics and geography. Given the sample size, and the well-known profiles of many HI researchers from the United Kingdom, we do not provide further details to preserve study participant anonymity.

Participants signed an informed consent form prior to their interview, in line with ethics approval. Interviews were conducted in English by either one or two of the authors. Five interviews were conducted in person, and seven by teleconference. All interviews were audio-recorded, and one author was responsible for transcribing and translating the audio recordings, which were double-checked. All data were anonymized by the removal of any personal information that might reveal their personal identity. Participants were coded as P1–P12 in the results. The original and anonymized data (audio and transcripts) were stored separately in secure encrypted external hard drives that only the research team had access to. These data were iteratively triangulated with grey and scientific literature, which was identified through snowballing techniques and reviewed with the research questions and interview data in mind. One author initially coded the data using Microsoft Word 10 and analysed all the texts to identify recurrent themes, which were reviewed and agreed on by a second author [ 9 ]. Evidence from the various data sources was then synthesized, examined, interpreted and discussed between the authors until consensus was reached.

Through our case study, we found evidence to support our hypothesis that at least four of our proposed mechanisms (M) have been present and activated by a combination of contextual conditions (C) at different moments over the past five decades, which has likely led to the identified high production of HI research (O) in the United Kingdom [ 5 ]. In particular, we found strong evidence to support our hypotheses that M1 ( recognition with concern ) and M2 ( sense of moral responsibility ) have been present and activated during this process and time period and have contributed to the outcome of interest (O). In addition, based on our study findings, we refined several of our proposed mechanisms (M3, M4, M5 and M6) and identified two new potential mechanisms (M7 and M8) that might have been at play as well (Table 2 ).

M1: recognition with concern

Strong evidence gathered from the different data sources suggests that M1 has been present in the United Kingdom during different moments over the past few decades, and has actively contributed to the initiation and development of the national production of HI research (O). Evidence also suggests that during different historical periods, “recognition” alone has acted as a contextual factor (C); however, once it is combined with “concern” it becomes activated, and together they act as a mechanism of change (M).

The United Kingdom’s production of HI research was established in the 1980s [ 3 , 13 , 14 , 15 ], yet important questions are raised such as why and how was it established. Evidence suggests that “dramatic events” and/or perceptions of socioeconomic crisis [ 16 , 17 , 18 ] lead to public debate, recognition of and widespread concern about socially relevant issues (such as HI), which stimulates active investigation [ 14 , 19 , 20 ]. The following quotes illustrate this:

I think it’s a kind of long running line of debate and concern, political concern…it was really about a kind of moral panic… there are these sort of moments I think, partly political, partly science based, and partly a kind of public outcry about social conditions. (P11: Professor) You get a sudden collection of interests in social inequality, which may be because of either a change of government or a mini-revolution… and people may ask the question, why is there a lot of inequality in these country … So that’s the spark. (P6: Professor)

Prior to the mid-1970s, there had been an economic crisis in the United Kingdom and an increase in social and HI [ 16 , 17 , 21 , 22 ], which triggered “ public outcry [with a] growing public perception of a divided society ” [ 23 ] (p. 484). Also, after the establishment of the United Kingdom’s welfare state and National Health Service (NHS) in the early post-Second World War period, there had been a general assumption that population health would improve and HI would eventually decline, which they initially did [ 14 , 15 ]. Yet, by the 1970s, they had increased once again, which raised concern over the effectiveness of the NHS and related public expenditure [ 15 , 16 , 21 , 24 , 25 ] (C).

Whitehead’s [ 10 ] Action spectrum on inequalities in health model includes recognition of HI as one of the initial activities (C). Whitehead explains that there is already a strong tradition of research and recognition of HI in the United Kingdom, dating back to the nineteenth century, when there were “ pioneering collectors of statistics, also offering social commentary on the data they gathered ” [ 10 ] (p. 480) (C). This, in combination with the new recognition of noticeable “ deteriorating socio-economic conditions [and] worsening health trends ” [ 10 ] (p. 472–3) during the 1960s and 1970s (C), and strategies of “ promoting awareness ” of the problems (C), raised “ voices of concern…about the extent of [HI]” (C, and M1). Whitehead also mentions the role of “ professional advocates ” [ 23 ] (p. 487) and the “ intense professional pressures from health-related bodies and medical journals ” [ 23 ] (p. 483) (C), which in combination with various reports and other actions [ 26 ] helped to raise further awareness and interest in HI (C and/or M1). In addition, the author states that “ concern reached such a level by 1977 that the Labour government was persuaded to set up the [HI] Research Working Group, under the chairmanship of Sir Douglas Black ” [ 10 ] (p. 482) (M1).

The Black Committee was set up to assess national and international evidence on HI and draw up policy implications. The work of this committee led to the famous 1980 Black Report [ 13 , 27 ]. The Black Report was said to have represented a significant shift in political thinking about HI [ 16 ]: it accumulated evidence that confirmed the existence of HI and showed the clear link between health and social position [ 15 ]. Evidence suggests that these findings sparked a key interest in HI and a growth in this research field, both in the United Kingdom (O) and abroad [ 3 , 13 , 27 , 28 ].

We suspect that M1 might have also been activated in 1997, when HI were once again “recognized” as an important issue to be addressed (C) and were placed on the national political agenda by the New Labour (moderate social democratic party) government at the time [ 3 , 15 , 20 , 29 , 30 ] (C). This may have activated M1 at the political level, as the new government then commissioned an independent inquiry into HI, the so-called Acheson Report [ 31 ]. This report provided a comprehensive up-to-date synthesis of the HI scientific evidence and recommendations, mainly consistent with those of the Black Report [ 3 , 15 ]. During this time, there was a strong political commitment to tackling HI [ 30 ], which in turn created favourable HI research conditions (C), such as an increase in dedicated HI research funding (C and/or M4) [ 15 ], resulting in more HI research being produced (O). This process may have occurred again in 2010, when the New Labour government commissioned the English review of the social determinants of health (SDH) (also known as the Marmot Review ) to compile the latest evidence on HI [ 22 , 32 ].

Inhibition of M1: recognition with concern, or a potential new mechanism M7—misrecognition and denial

Interestingly, there is evidence to suggest that the lack of political recognition and concern (M1)—or even misrecognition and denial acting as a potential new mechanism (M7)—regarding HI during the 1980s and 1990s [ 10 ] was important to stimulate the generation of HI research (O). For the sake of chronological continuity in terms of the historical timelines of the HI research production process in the United Kingdom, we include this section on M7 here, since its contents will be important to understand the following sections.

By the time the Black Report was published in 1980 (despite having been commissioned by the former Labour government), the Conservative Thatcher government was in power, and evidence states that they were not keen to acknowledge the evidence and recommendations presented in the report [ 3 , 20 , 33 ]. However, the way in which the Conservative government released the Black Report , dismissed its findings and refuted the evidence on HI triggered an outcry by the public health community and top medical journals, as well as intrigue from the media [ 3 , 18 , 27 , 33 , 34 ] (potentially C and/or M1). As the following quote discusses:

The publication of the Black Report in 1980 was absolutely pivotal… Its fame was fuelled by the fact that the government tried to bury it, and when it couldn’t, it tried to discredit it…that was like a red rag to a bull as far as the medical professional was concerned… and The Lancet and the BMJ… there was a feeling that it was being somehow pushed under the carpet, so as soon as journalists got wind of it, they thought “oh, there’s a story here, you know the government is trying to hide it”, so that helped circulate it. (P8: Professor)

Findings suggest that the Conservative government’s negative reaction (C and/or M7) also “incentivized” certain individuals to act [ 3 , 22 ]. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, while the Conservative government was in power, there was a sociopolitical and scientific struggle for recognition of HI, both in and outside of academia, determined to prove that HI existed [ 9 , 35 ] (M1 and M2), as the following quotes illustrate:

Back in the ’80s, there was a real attack on any idea that health inequality was real, and a lot of us spent a lot of time on this… we had a big struggle to prove health inequalities exist. (P4: Professor) As a result of Thatcher’s suppression of the health inequalities discourse… it sort of went underground, but equally true, it flourished outside the [central] government public sector…there were lots of Labour local authorities that produced what we used to call “local Black Reports”… and the third sector… [all] working together to keep the flag flying, and the concept alive. (P1: Lecturer)

Furthermore, evidence suggests that the media and certain academic journals have been important for circulating the HI discourse over the years (C) [ 18 , 28 ], due to their “ recognition of the importance of the issue ” [ 18 ] (p. 28) and willingness to publish material on the topic [ 3 , 18 , 26 ]. This likely helped to circulate or “diffuse” HI ideas (C), which were then picked up by others [ 10 , 18 , 36 ]. This process seems to have helped to circulate wider recognition and concern for HI (M1). The follow quote touches on this:

When I first started doing research on health inequalities… [people] didn’t know whether they were higher at the top or bottom … then all the little bits of research on poverty and health, unemployment and health and so on… 10–15 years later you could talk to people … they’d ask what are you doing… you’d [explain] and they would say “what’s the point, isn’t it obvious?” and that was such a huge change. I think that was done though little bits and pieces, over time, by little bits of research coming out in the media ... [creating] a common sense that hadn’t existed earlier. (P5: Professor)

Evidence on M2: sense of moral responsibility to act

Strong evidence, particularly from the interviews, suggests that M2 has been present and has acted during different moments over the past few decades, which has contributed to the development of the national production of HI research (O). All participants reported that individual and institutional values, views and ideology have played an important role (C and/or via M2) in the HI research production process in the United Kingdom over time (O). The following quote explains this:

Certainly, all of my research has been driven by my values…and my commitment—personally and politically—to social justice. So I don’t think my research is biased by that, but it’s driven by that…I think that it’s probably the case for anyone in this field. I just think that some people are more explicit about it than others… for me, health inequalities are profoundly political…You can depoliticize health inequalities in a research frame…but you can’t depoliticize the issue really. (P2: Professor)

During the 1980s and 1990s, it was apparently difficult to obtain funding for HI research, and scholars have since reported that it was “ a lonely time ” for any HI researcher who decided to “ stick it out ” [ 37 ], and that their work was heavily scrutinized [ 28 ]. The presence of strong personal (egalitarian) values and a sense of moral responsibility to address social injustice seem to partly explain why some researchers remained so committed to working in this research field, despite the unfavourable working conditions (M2). In addition, several interviewees also stated that they thought that individual values and views, combined with different disciplinary perspectives and other factors (C), have been important to produce not only HI research (O), but also different types of HI research (i.e. focusing on more upstream or downstream determinants of health and HI). For example:

There are researchers who would focus more on the psychosocial explanations, and there are researchers who would focus more on the social-material conditions, and would maybe have different values around that ... you get these very deep and personally felt controversies… I’m sure there is a whole mix… the psychological and the political, and the two are probably entwined. (P11: Professor) Most people studying health inequalities…identify themselves as left-of-centre, but then there is a really big difference between how left-of-centre, and who they see as their allies…those kinds of personal relationships have an impact on how the field is shaped…there’s political and ideological, and kind of value-based things that everyone is bringing to the field, but they are also bringing their disciplinary training, and their personal likes…and all of those things interact. (P3: Professor)

Evidence on M3 potential refined: Stewardship and/or leadership for HI research

Findings suggest that stewardship and leadership existed at the individual and institutional levels during certain historical periods, which have helped to create an enabling HI research environment (C), and in turn lead to the production of HI research (O). It is unclear whether M3 should remain as “stewardship” or be refined to “leadership”, or whether these are potentially two different mechanisms. Some interview participants discussed the important role of individual HI scientific leadership; for example:

Oh, it will be a story of individuals…a couple of plucky individuals who would have plugged away. (P10: Professor) There have been some really key figureheads, who have set up institutions and they’ve attracted a lot of funding, got a strong reputation, and there’ve been people who have been training through them. (P4: Professor)

Several participants also emphasized the importance of certain academic institutions as HI research stewards and leaders, due to their history and strong tradition within certain cities. These institutions have then attracted certain individuals to work in them (M3 at the individual level). As the following interviews illustrate: