1.2 The Scientific Methods

Section learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Explain how the methods of science are used to make scientific discoveries

- Define a scientific model and describe examples of physical and mathematical models used in physics

- Compare and contrast hypothesis, theory, and law

Teacher Support

The learning objectives in this section will help your students master the following standards:

- (A) know the definition of science and understand that it has limitations, as specified in subsection (b)(2) of this section;

- (B) know that scientific hypotheses are tentative and testable statements that must be capable of being supported or not supported by observational evidence. Hypotheses of durable explanatory power which have been tested over a wide variety of conditions are incorporated into theories;

- (C) know that scientific theories are based on natural and physical phenomena and are capable of being tested by multiple independent researchers. Unlike hypotheses, scientific theories are well-established and highly-reliable explanations, but may be subject to change as new areas of science and new technologies are developed;

- (D) distinguish between scientific hypotheses and scientific theories.

Section Key Terms

[OL] Pre-assessment for this section could involve students sharing or writing down an anecdote about when they used the methods of science. Then, students could label their thought processes in their anecdote with the appropriate scientific methods. The class could also discuss their definitions of theory and law, both outside and within the context of science.

[OL] It should be noted and possibly mentioned that a scientist , as mentioned in this section, does not necessarily mean a trained scientist. It could be anyone using methods of science.

Scientific Methods

Scientists often plan and carry out investigations to answer questions about the universe around us. These investigations may lead to natural laws. Such laws are intrinsic to the universe, meaning that humans did not create them and cannot change them. We can only discover and understand them. Their discovery is a very human endeavor, with all the elements of mystery, imagination, struggle, triumph, and disappointment inherent in any creative effort. The cornerstone of discovering natural laws is observation. Science must describe the universe as it is, not as we imagine or wish it to be.

We all are curious to some extent. We look around, make generalizations, and try to understand what we see. For example, we look up and wonder whether one type of cloud signals an oncoming storm. As we become serious about exploring nature, we become more organized and formal in collecting and analyzing data. We attempt greater precision, perform controlled experiments (if we can), and write down ideas about how data may be organized. We then formulate models, theories, and laws based on the data we have collected, and communicate those results with others. This, in a nutshell, describes the scientific method that scientists employ to decide scientific issues on the basis of evidence from observation and experiment.

An investigation often begins with a scientist making an observation . The scientist observes a pattern or trend within the natural world. Observation may generate questions that the scientist wishes to answer. Next, the scientist may perform some research about the topic and devise a hypothesis . A hypothesis is a testable statement that describes how something in the natural world works. In essence, a hypothesis is an educated guess that explains something about an observation.

[OL] An educated guess is used throughout this section in describing a hypothesis to combat the tendency to think of a theory as an educated guess.

Scientists may test the hypothesis by performing an experiment . During an experiment, the scientist collects data that will help them learn about the phenomenon they are studying. Then the scientists analyze the results of the experiment (that is, the data), often using statistical, mathematical, and/or graphical methods. From the data analysis, they draw conclusions. They may conclude that their experiment either supports or rejects their hypothesis. If the hypothesis is supported, the scientist usually goes on to test another hypothesis related to the first. If their hypothesis is rejected, they will often then test a new and different hypothesis in their effort to learn more about whatever they are studying.

Scientific processes can be applied to many situations. Let’s say that you try to turn on your car, but it will not start. You have just made an observation! You ask yourself, "Why won’t my car start?" You can now use scientific processes to answer this question. First, you generate a hypothesis such as, "The car won’t start because it has no gasoline in the gas tank." To test this hypothesis, you put gasoline in the car and try to start it again. If the car starts, then your hypothesis is supported by the experiment. If the car does not start, then your hypothesis is rejected. You will then need to think up a new hypothesis to test such as, "My car won’t start because the fuel pump is broken." Hopefully, your investigations lead you to discover why the car won’t start and enable you to fix it.

A model is a representation of something that is often too difficult (or impossible) to study directly. Models can take the form of physical models, equations, computer programs, or simulations—computer graphics/animations. Models are tools that are especially useful in modern physics because they let us visualize phenomena that we normally cannot observe with our senses, such as very small objects or objects that move at high speeds. For example, we can understand the structure of an atom using models, without seeing an atom with our own eyes. Although images of single atoms are now possible, these images are extremely difficult to achieve and are only possible due to the success of our models. The existence of these images is a consequence rather than a source of our understanding of atoms. Models are always approximate, so they are simpler to consider than the real situation; the more complete a model is, the more complicated it must be. Models put the intangible or the extremely complex into human terms that we can visualize, discuss, and hypothesize about.

Scientific models are constructed based on the results of previous experiments. Even still, models often only describe a phenomenon partially or in a few limited situations. Some phenomena are so complex that they may be impossible to model them in their entirety, even using computers. An example is the electron cloud model of the atom in which electrons are moving around the atom’s center in distinct clouds ( Figure 1.12 ), that represent the likelihood of finding an electron in different places. This model helps us to visualize the structure of an atom. However, it does not show us exactly where an electron will be within its cloud at any one particular time.

As mentioned previously, physicists use a variety of models including equations, physical models, computer simulations, etc. For example, three-dimensional models are often commonly used in chemistry and physics to model molecules. Properties other than appearance or location are usually modelled using mathematics, where functions are used to show how these properties relate to one another. Processes such as the formation of a star or the planets, can also be modelled using computer simulations. Once a simulation is correctly programmed based on actual experimental data, the simulation can allow us to view processes that happened in the past or happen too quickly or slowly for us to observe directly. In addition, scientists can also run virtual experiments using computer-based models. In a model of planet formation, for example, the scientist could alter the amount or type of rocks present in space and see how it affects planet formation.

Scientists use models and experimental results to construct explanations of observations or design solutions to problems. For example, one way to make a car more fuel efficient is to reduce the friction or drag caused by air flowing around the moving car. This can be done by designing the body shape of the car to be more aerodynamic, such as by using rounded corners instead of sharp ones. Engineers can then construct physical models of the car body, place them in a wind tunnel, and examine the flow of air around the model. This can also be done mathematically in a computer simulation. The air flow pattern can be analyzed for regions smooth air flow and for eddies that indicate drag. The model of the car body may have to be altered slightly to produce the smoothest pattern of air flow (i.e., the least drag). The pattern with the least drag may be the solution to increasing fuel efficiency of the car. This solution might then be incorporated into the car design.

Using Models and the Scientific Processes

Be sure to secure loose items before opening the window or door.

In this activity, you will learn about scientific models by making a model of how air flows through your classroom or a room in your house.

- One room with at least one window or door that can be opened

- Work with a group of four, as directed by your teacher. Close all of the windows and doors in the room you are working in. Your teacher may assign you a specific window or door to study.

- Before opening any windows or doors, draw a to-scale diagram of your room. First, measure the length and width of your room using the tape measure. Then, transform the measurement using a scale that could fit on your paper, such as 5 centimeters = 1 meter.

- Your teacher will assign you a specific window or door to study air flow. On your diagram, add arrows showing your hypothesis (before opening any windows or doors) of how air will flow through the room when your assigned window or door is opened. Use pencil so that you can easily make changes to your diagram.

- On your diagram, mark four locations where you would like to test air flow in your room. To test for airflow, hold a strip of single ply tissue paper between the thumb and index finger. Note the direction that the paper moves when exposed to the airflow. Then, for each location, predict which way the paper will move if your air flow diagram is correct.

- Now, each member of your group will stand in one of the four selected areas. Each member will test the airflow Agree upon an approximate height at which everyone will hold their papers.

- When you teacher tells you to, open your assigned window and/or door. Each person should note the direction that their paper points immediately after the window or door was opened. Record your results on your diagram.

- Did the airflow test data support or refute the hypothetical model of air flow shown in your diagram? Why or why not? Correct your model based on your experimental evidence.

- With your group, discuss how accurate your model is. What limitations did it have? Write down the limitations that your group agreed upon.

- Yes, you could use your model to predict air flow through a new window. The earlier experiment of air flow would help you model the system more accurately.

- Yes, you could use your model to predict air flow through a new window. The earlier experiment of air flow is not useful for modeling the new system.

- No, you cannot model a system to predict the air flow through a new window. The earlier experiment of air flow would help you model the system more accurately.

- No, you cannot model a system to predict the air flow through a new window. The earlier experiment of air flow is not useful for modeling the new system.

This Snap Lab! has students construct a model of how air flows in their classroom. Each group of four students will create a model of air flow in their classroom using a scale drawing of the room. Then, the groups will test the validity of their model by placing weathervanes that they have constructed around the room and opening a window or door. By observing the weather vanes, students will see how air actually flows through the room from a specific window or door. Students will then correct their model based on their experimental evidence. The following material list is given per group:

- One room with at least one window or door that can be opened (An optimal configuration would be one window or door per group.)

- Several pieces of construction paper (at least four per group)

- Strips of single ply tissue paper

- One tape measure (long enough to measure the dimensions of the room)

- Group size can vary depending on the number of windows/doors available and the number of students in the class.

- The room dimensions could be provided by the teacher. Also, students may need a brief introduction in how to make a drawing to scale.

- This is another opportunity to discuss controlled experiments in terms of why the students should hold the strips of tissue paper at the same height and in the same way. One student could also serve as a control and stand far away from the window/door or in another area that will not receive air flow from the window/door.

- You will probably need to coordinate this when multiple windows or doors are used. Only one window or door should be opened at a time for best results. Between openings, allow a short period (5 minutes) when all windows and doors are closed, if possible.

Answers to the Grasp Check will vary, but the air flow in the new window or door should be based on what the students observed in their experiment.

Scientific Laws and Theories

A scientific law is a description of a pattern in nature that is true in all circumstances that have been studied. That is, physical laws are meant to be universal , meaning that they apply throughout the known universe. Laws are often also concise, whereas theories are more complicated. A law can be expressed in the form of a single sentence or mathematical equation. For example, Newton’s second law of motion , which relates the motion of an object to the force applied ( F ), the mass of the object ( m ), and the object’s acceleration ( a ), is simply stated using the equation

Scientific ideas and explanations that are true in many, but not all situations in the universe are usually called principles . An example is Pascal’s principle , which explains properties of liquids, but not solids or gases. However, the distinction between laws and principles is sometimes not carefully made in science.

A theory is an explanation for patterns in nature that is supported by much scientific evidence and verified multiple times by multiple researchers. While many people confuse theories with educated guesses or hypotheses, theories have withstood more rigorous testing and verification than hypotheses.

[OL] Explain to students that in informal, everyday English the word theory can be used to describe an idea that is possibly true but that has not been proven to be true. This use of the word theory often leads people to think that scientific theories are nothing more than educated guesses. This is not just a misconception among students, but among the general public as well.

As a closing idea about scientific processes, we want to point out that scientific laws and theories, even those that have been supported by experiments for centuries, can still be changed by new discoveries. This is especially true when new technologies emerge that allow us to observe things that were formerly unobservable. Imagine how viewing previously invisible objects with a microscope or viewing Earth for the first time from space may have instantly changed our scientific theories and laws! What discoveries still await us in the future? The constant retesting and perfecting of our scientific laws and theories allows our knowledge of nature to progress. For this reason, many scientists are reluctant to say that their studies prove anything. By saying support instead of prove , it keeps the door open for future discoveries, even if they won’t occur for centuries or even millennia.

[OL] With regard to scientists avoiding using the word prove , the general public knows that science has proven certain things such as that the heart pumps blood and the Earth is round. However, scientists should shy away from using prove because it is impossible to test every single instance and every set of conditions in a system to absolutely prove anything. Using support or similar terminology leaves the door open for further discovery.

Check Your Understanding

- Models are simpler to analyze.

- Models give more accurate results.

- Models provide more reliable predictions.

- Models do not require any computer calculations.

- They are the same.

- A hypothesis has been thoroughly tested and found to be true.

- A hypothesis is a tentative assumption based on what is already known.

- A hypothesis is a broad explanation firmly supported by evidence.

- A scientific model is a representation of something that can be easily studied directly. It is useful for studying things that can be easily analyzed by humans.

- A scientific model is a representation of something that is often too difficult to study directly. It is useful for studying a complex system or systems that humans cannot observe directly.

- A scientific model is a representation of scientific equipment. It is useful for studying working principles of scientific equipment.

- A scientific model is a representation of a laboratory where experiments are performed. It is useful for studying requirements needed inside the laboratory.

- The hypothesis must be validated by scientific experiments.

- The hypothesis must not include any physical quantity.

- The hypothesis must be a short and concise statement.

- The hypothesis must apply to all the situations in the universe.

- A scientific theory is an explanation of natural phenomena that is supported by evidence.

- A scientific theory is an explanation of natural phenomena without the support of evidence.

- A scientific theory is an educated guess about the natural phenomena occurring in nature.

- A scientific theory is an uneducated guess about natural phenomena occurring in nature.

- A hypothesis is an explanation of the natural world with experimental support, while a scientific theory is an educated guess about a natural phenomenon.

- A hypothesis is an educated guess about natural phenomenon, while a scientific theory is an explanation of natural world with experimental support.

- A hypothesis is experimental evidence of a natural phenomenon, while a scientific theory is an explanation of the natural world with experimental support.

- A hypothesis is an explanation of the natural world with experimental support, while a scientific theory is experimental evidence of a natural phenomenon.

Use the Check Your Understanding questions to assess students’ achievement of the section’s learning objectives. If students are struggling with a specific objective, the Check Your Understanding will help identify which objective and direct students to the relevant content.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute Texas Education Agency (TEA). The original material is available at: https://www.texasgateway.org/book/tea-physics . Changes were made to the original material, including updates to art, structure, and other content updates.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/physics/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Paul Peter Urone, Roger Hinrichs

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Physics

- Publication date: Mar 26, 2020

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/physics/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/physics/pages/1-2-the-scientific-methods

© Jan 19, 2024 Texas Education Agency (TEA). The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Understanding Science

How science REALLY works...

- Understanding Science 101

- Misconceptions

- Testing ideas with evidence is at the heart of the process of science.

- Scientific testing involves figuring out what we would expect to observe if an idea were correct and comparing that expectation to what we actually observe.

Misconception: Science proves ideas.

Misconception: Science can only disprove ideas.

Correction: Science neither proves nor disproves. It accepts or rejects ideas based on supporting and refuting evidence, but may revise those conclusions if warranted by new evidence or perspectives. Read more about it.

Testing scientific ideas

Testing ideas about childbed fever.

As a simple example of how scientific testing works, consider the case of Ignaz Semmelweis, who worked as a doctor on a maternity ward in the 1800s. In his ward, an unusually high percentage of new mothers died of what was then called childbed fever. Semmelweis considered many possible explanations for this high death rate. Two of the many ideas that he considered were (1) that the fever was caused by mothers giving birth lying on their backs (as opposed to on their sides) and (2) that the fever was caused by doctors’ unclean hands (the doctors often performed autopsies immediately before examining women in labor). He tested these ideas by considering what expectations each idea generated. If it were true that childbed fever were caused by giving birth on one’s back, then changing procedures so that women labored on their sides should lead to lower rates of childbed fever. Semmelweis tried changing the position of labor, but the incidence of fever did not decrease; the actual observations did not match the expected results. If, however, childbed fever were caused by doctors’ unclean hands, having doctors wash their hands thoroughly with a strong disinfecting agent before attending to women in labor should lead to lower rates of childbed fever. When Semmelweis tried this, rates of fever plummeted; the actual observations matched the expected results, supporting the second explanation.

Testing in the tropics

Let’s take a look at another, very different, example of scientific testing: investigating the origins of coral atolls in the tropics. Consider the atoll Eniwetok (Anewetak) in the Marshall Islands — an oceanic ring of exposed coral surrounding a central lagoon. From the 1800s up until today, scientists have been trying to learn what supports atoll structures beneath the water’s surface and exactly how atolls form. Coral only grows near the surface of the ocean where light penetrates, so Eniwetok could have formed in several ways:

Hypothesis 2: The coral that makes up Eniwetok might have grown in a ring atop an underwater mountain already near the surface. The key to this hypothesis is the idea that underwater mountains don’t sink; instead the remains of dead sea animals (shells, etc.) accumulate on underwater mountains, potentially assisted by tectonic uplifting. Eventually, the top of the mountain/debris pile would reach the depth at which coral grow, and the atoll would form.

Which is a better explanation for Eniwetok? Did the atoll grow atop a sinking volcano, forming an underwater coral tower, or was the mountain instead built up until it neared the surface where coral were eventually able to grow? Which of these explanations is best supported by the evidence? We can’t perform an experiment to find out. Instead, we must figure out what expectations each hypothesis generates, and then collect data from the world to see whether our observations are a better match with one of the two ideas.

If Eniwetok grew atop an underwater mountain, then we would expect the atoll to be made up of a relatively thin layer of coral on top of limestone or basalt. But if it grew upwards around a subsiding island, then we would expect the atoll to be made up of many hundreds of feet of coral on top of volcanic rock. When geologists drilled into Eniwetok in 1951 as part of a survey preparing for nuclear weapons tests, the drill bored through more than 4000 feet (1219 meters) of coral before hitting volcanic basalt! The actual observation contradicted the underwater mountain explanation and matched the subsiding island explanation, supporting that idea. Of course, many other lines of evidence also shed light on the origins of coral atolls, but the surprising depth of coral on Eniwetok was particularly convincing to many geologists.

- Take a sidetrip

Visit the NOAA website to see an animation of coral atoll formation according to Hypothesis 1.

- Teaching resources

Scientists test hypotheses and theories. They are both scientific explanations for what we observe in the natural world, but theories deal with a much wider range of phenomena than do hypotheses. To learn more about the differences between hypotheses and theories, jump ahead to Science at multiple levels .

- Use our web interactive to help students document and reflect on the process of science.

- Learn strategies for building lessons and activities around the Science Flowchart: Grades 3-5 Grades 6-8 Grades 9-12 Grades 13-16

- Find lesson plans for introducing the Science Flowchart to your students in: Grades 3-5 Grades 6-8 Grades 9-16

- Get graphics and pdfs of the Science Flowchart to use in your classroom. Translations are available in Spanish, French, Japanese, and Swahili.

Observation beyond our eyes

The logic of scientific arguments

Subscribe to our newsletter

- The science flowchart

- Science stories

- Grade-level teaching guides

- Teaching resource database

- Journaling tool

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Great Hypothesis

Hypothesis Definition, Format, Examples, and Tips

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Verywell / Alex Dos Diaz

- The Scientific Method

Hypothesis Format

Falsifiability of a hypothesis.

- Operationalization

Hypothesis Types

Hypotheses examples.

- Collecting Data

A hypothesis is a tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. It is a preliminary answer to your question that helps guide the research process.

Consider a study designed to examine the relationship between sleep deprivation and test performance. The hypothesis might be: "This study is designed to assess the hypothesis that sleep-deprived people will perform worse on a test than individuals who are not sleep-deprived."

At a Glance

A hypothesis is crucial to scientific research because it offers a clear direction for what the researchers are looking to find. This allows them to design experiments to test their predictions and add to our scientific knowledge about the world. This article explores how a hypothesis is used in psychology research, how to write a good hypothesis, and the different types of hypotheses you might use.

The Hypothesis in the Scientific Method

In the scientific method , whether it involves research in psychology, biology, or some other area, a hypothesis represents what the researchers think will happen in an experiment. The scientific method involves the following steps:

- Forming a question

- Performing background research

- Creating a hypothesis

- Designing an experiment

- Collecting data

- Analyzing the results

- Drawing conclusions

- Communicating the results

The hypothesis is a prediction, but it involves more than a guess. Most of the time, the hypothesis begins with a question which is then explored through background research. At this point, researchers then begin to develop a testable hypothesis.

Unless you are creating an exploratory study, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen.

In a study exploring the effects of a particular drug, the hypothesis might be that researchers expect the drug to have some type of effect on the symptoms of a specific illness. In psychology, the hypothesis might focus on how a certain aspect of the environment might influence a particular behavior.

Remember, a hypothesis does not have to be correct. While the hypothesis predicts what the researchers expect to see, the goal of the research is to determine whether this guess is right or wrong. When conducting an experiment, researchers might explore numerous factors to determine which ones might contribute to the ultimate outcome.

In many cases, researchers may find that the results of an experiment do not support the original hypothesis. When writing up these results, the researchers might suggest other options that should be explored in future studies.

In many cases, researchers might draw a hypothesis from a specific theory or build on previous research. For example, prior research has shown that stress can impact the immune system. So a researcher might hypothesize: "People with high-stress levels will be more likely to contract a common cold after being exposed to the virus than people who have low-stress levels."

In other instances, researchers might look at commonly held beliefs or folk wisdom. "Birds of a feather flock together" is one example of folk adage that a psychologist might try to investigate. The researcher might pose a specific hypothesis that "People tend to select romantic partners who are similar to them in interests and educational level."

Elements of a Good Hypothesis

So how do you write a good hypothesis? When trying to come up with a hypothesis for your research or experiments, ask yourself the following questions:

- Is your hypothesis based on your research on a topic?

- Can your hypothesis be tested?

- Does your hypothesis include independent and dependent variables?

Before you come up with a specific hypothesis, spend some time doing background research. Once you have completed a literature review, start thinking about potential questions you still have. Pay attention to the discussion section in the journal articles you read . Many authors will suggest questions that still need to be explored.

How to Formulate a Good Hypothesis

To form a hypothesis, you should take these steps:

- Collect as many observations about a topic or problem as you can.

- Evaluate these observations and look for possible causes of the problem.

- Create a list of possible explanations that you might want to explore.

- After you have developed some possible hypotheses, think of ways that you could confirm or disprove each hypothesis through experimentation. This is known as falsifiability.

In the scientific method , falsifiability is an important part of any valid hypothesis. In order to test a claim scientifically, it must be possible that the claim could be proven false.

Students sometimes confuse the idea of falsifiability with the idea that it means that something is false, which is not the case. What falsifiability means is that if something was false, then it is possible to demonstrate that it is false.

One of the hallmarks of pseudoscience is that it makes claims that cannot be refuted or proven false.

The Importance of Operational Definitions

A variable is a factor or element that can be changed and manipulated in ways that are observable and measurable. However, the researcher must also define how the variable will be manipulated and measured in the study.

Operational definitions are specific definitions for all relevant factors in a study. This process helps make vague or ambiguous concepts detailed and measurable.

For example, a researcher might operationally define the variable " test anxiety " as the results of a self-report measure of anxiety experienced during an exam. A "study habits" variable might be defined by the amount of studying that actually occurs as measured by time.

These precise descriptions are important because many things can be measured in various ways. Clearly defining these variables and how they are measured helps ensure that other researchers can replicate your results.

Replicability

One of the basic principles of any type of scientific research is that the results must be replicable.

Replication means repeating an experiment in the same way to produce the same results. By clearly detailing the specifics of how the variables were measured and manipulated, other researchers can better understand the results and repeat the study if needed.

Some variables are more difficult than others to define. For example, how would you operationally define a variable such as aggression ? For obvious ethical reasons, researchers cannot create a situation in which a person behaves aggressively toward others.

To measure this variable, the researcher must devise a measurement that assesses aggressive behavior without harming others. The researcher might utilize a simulated task to measure aggressiveness in this situation.

Hypothesis Checklist

- Does your hypothesis focus on something that you can actually test?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate the variables?

- Can your hypothesis be tested without violating ethical standards?

The hypothesis you use will depend on what you are investigating and hoping to find. Some of the main types of hypotheses that you might use include:

- Simple hypothesis : This type of hypothesis suggests there is a relationship between one independent variable and one dependent variable.

- Complex hypothesis : This type suggests a relationship between three or more variables, such as two independent and dependent variables.

- Null hypothesis : This hypothesis suggests no relationship exists between two or more variables.

- Alternative hypothesis : This hypothesis states the opposite of the null hypothesis.

- Statistical hypothesis : This hypothesis uses statistical analysis to evaluate a representative population sample and then generalizes the findings to the larger group.

- Logical hypothesis : This hypothesis assumes a relationship between variables without collecting data or evidence.

A hypothesis often follows a basic format of "If {this happens} then {this will happen}." One way to structure your hypothesis is to describe what will happen to the dependent variable if you change the independent variable .

The basic format might be: "If {these changes are made to a certain independent variable}, then we will observe {a change in a specific dependent variable}."

A few examples of simple hypotheses:

- "Students who eat breakfast will perform better on a math exam than students who do not eat breakfast."

- "Students who experience test anxiety before an English exam will get lower scores than students who do not experience test anxiety."

- "Motorists who talk on the phone while driving will be more likely to make errors on a driving course than those who do not talk on the phone."

- "Children who receive a new reading intervention will have higher reading scores than students who do not receive the intervention."

Examples of a complex hypothesis include:

- "People with high-sugar diets and sedentary activity levels are more likely to develop depression."

- "Younger people who are regularly exposed to green, outdoor areas have better subjective well-being than older adults who have limited exposure to green spaces."

Examples of a null hypothesis include:

- "There is no difference in anxiety levels between people who take St. John's wort supplements and those who do not."

- "There is no difference in scores on a memory recall task between children and adults."

- "There is no difference in aggression levels between children who play first-person shooter games and those who do not."

Examples of an alternative hypothesis:

- "People who take St. John's wort supplements will have less anxiety than those who do not."

- "Adults will perform better on a memory task than children."

- "Children who play first-person shooter games will show higher levels of aggression than children who do not."

Collecting Data on Your Hypothesis

Once a researcher has formed a testable hypothesis, the next step is to select a research design and start collecting data. The research method depends largely on exactly what they are studying. There are two basic types of research methods: descriptive research and experimental research.

Descriptive Research Methods

Descriptive research such as case studies , naturalistic observations , and surveys are often used when conducting an experiment is difficult or impossible. These methods are best used to describe different aspects of a behavior or psychological phenomenon.

Once a researcher has collected data using descriptive methods, a correlational study can examine how the variables are related. This research method might be used to investigate a hypothesis that is difficult to test experimentally.

Experimental Research Methods

Experimental methods are used to demonstrate causal relationships between variables. In an experiment, the researcher systematically manipulates a variable of interest (known as the independent variable) and measures the effect on another variable (known as the dependent variable).

Unlike correlational studies, which can only be used to determine if there is a relationship between two variables, experimental methods can be used to determine the actual nature of the relationship—whether changes in one variable actually cause another to change.

The hypothesis is a critical part of any scientific exploration. It represents what researchers expect to find in a study or experiment. In situations where the hypothesis is unsupported by the research, the research still has value. Such research helps us better understand how different aspects of the natural world relate to one another. It also helps us develop new hypotheses that can then be tested in the future.

Thompson WH, Skau S. On the scope of scientific hypotheses . R Soc Open Sci . 2023;10(8):230607. doi:10.1098/rsos.230607

Taran S, Adhikari NKJ, Fan E. Falsifiability in medicine: what clinicians can learn from Karl Popper [published correction appears in Intensive Care Med. 2021 Jun 17;:]. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47(9):1054-1056. doi:10.1007/s00134-021-06432-z

Eyler AA. Research Methods for Public Health . 1st ed. Springer Publishing Company; 2020. doi:10.1891/9780826182067.0004

Nosek BA, Errington TM. What is replication ? PLoS Biol . 2020;18(3):e3000691. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000691

Aggarwal R, Ranganathan P. Study designs: Part 2 - Descriptive studies . Perspect Clin Res . 2019;10(1):34-36. doi:10.4103/picr.PICR_154_18

Nevid J. Psychology: Concepts and Applications. Wadworth, 2013.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.1: Scientific Investigation

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 6252

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Chances are you've heard of the scientific method. But what exactly is the scientific method?

Is it a precise and exact way that all science must be done? Or is it a series of steps that most scientists generally follow, but may be modified for the benefit of an individual investigation?

The Scientific Method

"We also discovered that science is cool and fun because you get to do stuff that no one has ever done before." In the article Blackawton bees, published by eight to ten year old students: Biology Letters (2010) http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/early/2010/12/18/rsbl.2010.1056.abstract .

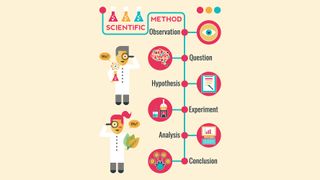

There are basic methods of gaining knowledge that are common to all of science. At the heart of science is the scientific investigation, which is done by following the scientific method . A scientific investigation is a plan for asking questions and testing possible answers. It generally follows the steps listed in Figure below . See http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KZaCy5Z87FA for an overview of the scientific method.

Steps of a Scientific Investigation. A scientific investigation typically has these steps. Scientists often develop their own steps they follow in a scientific investigation. Shown here is a simplification of how a scientific investigation is done.

Making Observations

A scientific investigation typically begins with observations. You make observations all the time. Let’s say you take a walk in the woods and observe a moth, like the one in Figure below, resting on a tree trunk. You notice that the moth has spots on its wings that look like eyes. You think the eye spots make the moth look like the face of an owl.

Figure 2: Marbled emperor moth Heniocha dyops in Botswana. (CC-SA-BY-4.0; Charlesjsharp ).

Does this moth remind you of an owl?

Asking a Question

Observations often lead to questions. For example, you might ask yourself why the moth has eye spots that make it look like an owl’s face. What reason might there be for this observation?

Forming a Hypothesis

The next step in a scientific investigation is forming a hypothesis . A hypothesis is a possible answer to a scientific question, but it isn’t just any answer. A hypothesis must be based on scientific knowledge, and it must be logical. A hypothesis also must be falsifiable. In other words, it must be possible to make observations that would disprove the hypothesis if it really is false. Assume you know that some birds eat moths and that owls prey on other birds. From this knowledge, you reason that eye spots scare away birds that might eat the moth. This is your hypothesis.

Testing the Hypothesis

To test a hypothesis, you first need to make a prediction based on the hypothesis. A prediction is a statement that tells what will happen under certain conditions. It can be expressed in the form: If A occurs, then B will happen. Based on your hypothesis, you might make this prediction: If a moth has eye spots on its wings, then birds will avoid eating it.

Next, you must gather evidence to test your prediction. Evidence is any type of data that may either agree or disagree with a prediction, so it may either support or disprove a hypothesis. Evidence may be gathered by an experiment . Assume that you gather evidence by making more observations of moths with eye spots. Perhaps you observe that birds really do avoid eating moths with eye spots. This evidence agrees with your prediction.

Drawing Conclusions

Evidence that agrees with your prediction supports your hypothesis. Does such evidence prove that your hypothesis is true? No; a hypothesis cannot be proven conclusively to be true. This is because you can never examine all of the possible evidence, and someday evidence might be found that disproves the hypothesis. Nonetheless, the more evidence that supports a hypothesis, the more likely the hypothesis is to be true.

Communicating Results

The last step in a scientific investigation is communicating what you have learned with others. This is a very important step because it allows others to test your hypothesis. If other researchers get the same results as yours, they add support to the hypothesis. However, if they get different results, they may disprove the hypothesis.

When scientists share their results, they should describe their methods and point out any possible problems with the investigation. For example, while you were observing moths, perhaps your presence scared birds away. This introduces an error into your investigation. You got the results you predicted (the birds avoided the moths while you were observing them), but not for the reason you hypothesized. Other researchers might be able to think of ways to avoid this error in future studies.

The Scientific Method Made Easy explains scientific method: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zcavPAFiG14 (9:55).

As you view The Scientific Method Made Easy, focus on these concepts: the relationship between evidence, conclusions and theories, the "ground rules" of scientific research, the steps in a scientific procedure, the meaning of the "replication of results," the meaning of "falsifiable," the outcome when the scientific method is not followed.

Discovering the Scientific Method

A summery video of the scientific method, using the identification of DNA structure as an example, is shown in this video by MIT students: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5eDNgeEUtMg .

Why I do Science

Dan Costa, Ph.D. is a professor of Biology at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and has been studying marine life for well over 40 years. He is a leader in using satellite tags, time and depth recorders and other sophisticated electronic tags to gather information about the amazing depths to which elephant seals dive, their migration routes and how they use oceanographic features to hunt for prey as far as the international dateline and the Alaskan Aleutian Islands. In the following KQED video, Dr. Costa discusses why he is a scientist: http://science.kqed.org/quest/video/why-i-do-science-dan-costa/ .

- At the heart of science is the scientific investigation, which is done by following the scientific method. A scientific investigation is a plan for asking questions and testing possible answers.

- A scientific investigation typically begins with observations. Observations often lead to questions.

- A hypothesis is a possible logical answer to a scientific question, based on scientific knowledge.

- A prediction is a statement that tells what will happen under certain conditions.

- Evidence is any type of data that may either agree or disagree with a prediction, so it may either support or disprove a hypothesis. Conclusions may be formed from evidence.

- The last step in a scientific investigation is the communication of results with others.

Explore More

Explore more i.

Use this resource to answer the questions that follow.

- Steps of the Scientific Method at http://www.sciencebuddies.org/science-fair-projects/project_scientific_method.shtml#overviewofthescientificmethod .

- Describe what is means to "Ask a Question."

- Describe what it means to "Construct a Hypothesis."

- How does a scientist conduct a fair test?

- What does a scientist do if the hypothesis is not supported?

Explore More II

- SciMeth Matching at http://www.studystack.com/matching-2497 .

- Outline the steps of a scientific investigation.

- What is a scientific hypothesis? What characteristics must a hypothesis have to be useful in science?

- Give an example of a scientific question that could be investigated with an experiment. Then give an example of question that could not be investigated.

- Can a hypothesis be proven true? Why or why not?

- Why do scientists communicate their results?

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Korean Med Sci

- v.36(50); 2021 Dec 27

Formulating Hypotheses for Different Study Designs

Durga prasanna misra.

1 Department of Clinical Immunology and Rheumatology, Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow, India.

Armen Yuri Gasparyan

2 Departments of Rheumatology and Research and Development, Dudley Group NHS Foundation Trust (Teaching Trust of the University of Birmingham, UK), Russells Hall Hospital, Dudley, UK.

Olena Zimba

3 Department of Internal Medicine #2, Danylo Halytsky Lviv National Medical University, Lviv, Ukraine.

Marlen Yessirkepov

4 Department of Biology and Biochemistry, South Kazakhstan Medical Academy, Shymkent, Kazakhstan.

Vikas Agarwal

George d. kitas.

5 Centre for Epidemiology versus Arthritis, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK.

Generating a testable working hypothesis is the first step towards conducting original research. Such research may prove or disprove the proposed hypothesis. Case reports, case series, online surveys and other observational studies, clinical trials, and narrative reviews help to generate hypotheses. Observational and interventional studies help to test hypotheses. A good hypothesis is usually based on previous evidence-based reports. Hypotheses without evidence-based justification and a priori ideas are not received favourably by the scientific community. Original research to test a hypothesis should be carefully planned to ensure appropriate methodology and adequate statistical power. While hypotheses can challenge conventional thinking and may be controversial, they should not be destructive. A hypothesis should be tested by ethically sound experiments with meaningful ethical and clinical implications. The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic has brought into sharp focus numerous hypotheses, some of which were proven (e.g. effectiveness of corticosteroids in those with hypoxia) while others were disproven (e.g. ineffectiveness of hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin).

Graphical Abstract

DEFINING WORKING AND STANDALONE SCIENTIFIC HYPOTHESES

Science is the systematized description of natural truths and facts. Routine observations of existing life phenomena lead to the creative thinking and generation of ideas about mechanisms of such phenomena and related human interventions. Such ideas presented in a structured format can be viewed as hypotheses. After generating a hypothesis, it is necessary to test it to prove its validity. Thus, hypothesis can be defined as a proposed mechanism of a naturally occurring event or a proposed outcome of an intervention. 1 , 2

Hypothesis testing requires choosing the most appropriate methodology and adequately powering statistically the study to be able to “prove” or “disprove” it within predetermined and widely accepted levels of certainty. This entails sample size calculation that often takes into account previously published observations and pilot studies. 2 , 3 In the era of digitization, hypothesis generation and testing may benefit from the availability of numerous platforms for data dissemination, social networking, and expert validation. Related expert evaluations may reveal strengths and limitations of proposed ideas at early stages of post-publication promotion, preventing the implementation of unsupported controversial points. 4

Thus, hypothesis generation is an important initial step in the research workflow, reflecting accumulating evidence and experts' stance. In this article, we overview the genesis and importance of scientific hypotheses and their relevance in the era of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

DO WE NEED HYPOTHESES FOR ALL STUDY DESIGNS?

Broadly, research can be categorized as primary or secondary. In the context of medicine, primary research may include real-life observations of disease presentations and outcomes. Single case descriptions, which often lead to new ideas and hypotheses, serve as important starting points or justifications for case series and cohort studies. The importance of case descriptions is particularly evident in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic when unique, educational case reports have heralded a new era in clinical medicine. 5

Case series serve similar purpose to single case reports, but are based on a slightly larger quantum of information. Observational studies, including online surveys, describe the existing phenomena at a larger scale, often involving various control groups. Observational studies include variable-scale epidemiological investigations at different time points. Interventional studies detail the results of therapeutic interventions.

Secondary research is based on already published literature and does not directly involve human or animal subjects. Review articles are generated by secondary research. These could be systematic reviews which follow methods akin to primary research but with the unit of study being published papers rather than humans or animals. Systematic reviews have a rigid structure with a mandatory search strategy encompassing multiple databases, systematic screening of search results against pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, critical appraisal of study quality and an optional component of collating results across studies quantitatively to derive summary estimates (meta-analysis). 6 Narrative reviews, on the other hand, have a more flexible structure. Systematic literature searches to minimise bias in selection of articles are highly recommended but not mandatory. 7 Narrative reviews are influenced by the authors' viewpoint who may preferentially analyse selected sets of articles. 8

In relation to primary research, case studies and case series are generally not driven by a working hypothesis. Rather, they serve as a basis to generate a hypothesis. Observational or interventional studies should have a hypothesis for choosing research design and sample size. The results of observational and interventional studies further lead to the generation of new hypotheses, testing of which forms the basis of future studies. Review articles, on the other hand, may not be hypothesis-driven, but form fertile ground to generate future hypotheses for evaluation. Fig. 1 summarizes which type of studies are hypothesis-driven and which lead on to hypothesis generation.

STANDARDS OF WORKING AND SCIENTIFIC HYPOTHESES

A review of the published literature did not enable the identification of clearly defined standards for working and scientific hypotheses. It is essential to distinguish influential versus not influential hypotheses, evidence-based hypotheses versus a priori statements and ideas, ethical versus unethical, or potentially harmful ideas. The following points are proposed for consideration while generating working and scientific hypotheses. 1 , 2 Table 1 summarizes these points.

Evidence-based data

A scientific hypothesis should have a sound basis on previously published literature as well as the scientist's observations. Randomly generated (a priori) hypotheses are unlikely to be proven. A thorough literature search should form the basis of a hypothesis based on published evidence. 7

Unless a scientific hypothesis can be tested, it can neither be proven nor be disproven. Therefore, a scientific hypothesis should be amenable to testing with the available technologies and the present understanding of science.

Supported by pilot studies

If a hypothesis is based purely on a novel observation by the scientist in question, it should be grounded on some preliminary studies to support it. For example, if a drug that targets a specific cell population is hypothesized to be useful in a particular disease setting, then there must be some preliminary evidence that the specific cell population plays a role in driving that disease process.

Testable by ethical studies

The hypothesis should be testable by experiments that are ethically acceptable. 9 For example, a hypothesis that parachutes reduce mortality from falls from an airplane cannot be tested using a randomized controlled trial. 10 This is because it is obvious that all those jumping from a flying plane without a parachute would likely die. Similarly, the hypothesis that smoking tobacco causes lung cancer cannot be tested by a clinical trial that makes people take up smoking (since there is considerable evidence for the health hazards associated with smoking). Instead, long-term observational studies comparing outcomes in those who smoke and those who do not, as was performed in the landmark epidemiological case control study by Doll and Hill, 11 are more ethical and practical.

Balance between scientific temper and controversy

Novel findings, including novel hypotheses, particularly those that challenge established norms, are bound to face resistance for their wider acceptance. Such resistance is inevitable until the time such findings are proven with appropriate scientific rigor. However, hypotheses that generate controversy are generally unwelcome. For example, at the time the pandemic of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and AIDS was taking foot, there were numerous deniers that refused to believe that HIV caused AIDS. 12 , 13 Similarly, at a time when climate change is causing catastrophic changes to weather patterns worldwide, denial that climate change is occurring and consequent attempts to block climate change are certainly unwelcome. 14 The denialism and misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic, including unfortunate examples of vaccine hesitancy, are more recent examples of controversial hypotheses not backed by science. 15 , 16 An example of a controversial hypothesis that was a revolutionary scientific breakthrough was the hypothesis put forth by Warren and Marshall that Helicobacter pylori causes peptic ulcers. Initially, the hypothesis that a microorganism could cause gastritis and gastric ulcers faced immense resistance. When the scientists that proposed the hypothesis themselves ingested H. pylori to induce gastritis in themselves, only then could they convince the wider world about their hypothesis. Such was the impact of the hypothesis was that Barry Marshall and Robin Warren were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2005 for this discovery. 17 , 18

DISTINGUISHING THE MOST INFLUENTIAL HYPOTHESES

Influential hypotheses are those that have stood the test of time. An archetype of an influential hypothesis is that proposed by Edward Jenner in the eighteenth century that cowpox infection protects against smallpox. While this observation had been reported for nearly a century before this time, it had not been suitably tested and publicised until Jenner conducted his experiments on a young boy by demonstrating protection against smallpox after inoculation with cowpox. 19 These experiments were the basis for widespread smallpox immunization strategies worldwide in the 20th century which resulted in the elimination of smallpox as a human disease today. 20

Other influential hypotheses are those which have been read and cited widely. An example of this is the hygiene hypothesis proposing an inverse relationship between infections in early life and allergies or autoimmunity in adulthood. An analysis reported that this hypothesis had been cited more than 3,000 times on Scopus. 1

LESSONS LEARNED FROM HYPOTHESES AMIDST THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

The COVID-19 pandemic devastated the world like no other in recent memory. During this period, various hypotheses emerged, understandably so considering the public health emergency situation with innumerable deaths and suffering for humanity. Within weeks of the first reports of COVID-19, aberrant immune system activation was identified as a key driver of organ dysfunction and mortality in this disease. 21 Consequently, numerous drugs that suppress the immune system or abrogate the activation of the immune system were hypothesized to have a role in COVID-19. 22 One of the earliest drugs hypothesized to have a benefit was hydroxychloroquine. Hydroxychloroquine was proposed to interfere with Toll-like receptor activation and consequently ameliorate the aberrant immune system activation leading to pathology in COVID-19. 22 The drug was also hypothesized to have a prophylactic role in preventing infection or disease severity in COVID-19. It was also touted as a wonder drug for the disease by many prominent international figures. However, later studies which were well-designed randomized controlled trials failed to demonstrate any benefit of hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19. 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 Subsequently, azithromycin 27 , 28 and ivermectin 29 were hypothesized as potential therapies for COVID-19, but were not supported by evidence from randomized controlled trials. The role of vitamin D in preventing disease severity was also proposed, but has not been proven definitively until now. 30 , 31 On the other hand, randomized controlled trials identified the evidence supporting dexamethasone 32 and interleukin-6 pathway blockade with tocilizumab as effective therapies for COVID-19 in specific situations such as at the onset of hypoxia. 33 , 34 Clues towards the apparent effectiveness of various drugs against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in vitro but their ineffectiveness in vivo have recently been identified. Many of these drugs are weak, lipophilic bases and some others induce phospholipidosis which results in apparent in vitro effectiveness due to non-specific off-target effects that are not replicated inside living systems. 35 , 36

Another hypothesis proposed was the association of the routine policy of vaccination with Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) with lower deaths due to COVID-19. This hypothesis emerged in the middle of 2020 when COVID-19 was still taking foot in many parts of the world. 37 , 38 Subsequently, many countries which had lower deaths at that time point went on to have higher numbers of mortality, comparable to other areas of the world. Furthermore, the hypothesis that BCG vaccination reduced COVID-19 mortality was a classic example of ecological fallacy. Associations between population level events (ecological studies; in this case, BCG vaccination and COVID-19 mortality) cannot be directly extrapolated to the individual level. Furthermore, such associations cannot per se be attributed as causal in nature, and can only serve to generate hypotheses that need to be tested at the individual level. 39

IS TRADITIONAL PEER REVIEW EFFICIENT FOR EVALUATION OF WORKING AND SCIENTIFIC HYPOTHESES?

Traditionally, publication after peer review has been considered the gold standard before any new idea finds acceptability amongst the scientific community. Getting a work (including a working or scientific hypothesis) reviewed by experts in the field before experiments are conducted to prove or disprove it helps to refine the idea further as well as improve the experiments planned to test the hypothesis. 40 A route towards this has been the emergence of journals dedicated to publishing hypotheses such as the Central Asian Journal of Medical Hypotheses and Ethics. 41 Another means of publishing hypotheses is through registered research protocols detailing the background, hypothesis, and methodology of a particular study. If such protocols are published after peer review, then the journal commits to publishing the completed study irrespective of whether the study hypothesis is proven or disproven. 42 In the post-pandemic world, online research methods such as online surveys powered via social media channels such as Twitter and Instagram might serve as critical tools to generate as well as to preliminarily test the appropriateness of hypotheses for further evaluation. 43 , 44

Some radical hypotheses might be difficult to publish after traditional peer review. These hypotheses might only be acceptable by the scientific community after they are tested in research studies. Preprints might be a way to disseminate such controversial and ground-breaking hypotheses. 45 However, scientists might prefer to keep their hypotheses confidential for the fear of plagiarism of ideas, avoiding online posting and publishing until they have tested the hypotheses.

SUGGESTIONS ON GENERATING AND PUBLISHING HYPOTHESES

Publication of hypotheses is important, however, a balance is required between scientific temper and controversy. Journal editors and reviewers might keep in mind these specific points, summarized in Table 2 and detailed hereafter, while judging the merit of hypotheses for publication. Keeping in mind the ethical principle of primum non nocere, a hypothesis should be published only if it is testable in a manner that is ethically appropriate. 46 Such hypotheses should be grounded in reality and lend themselves to further testing to either prove or disprove them. It must be considered that subsequent experiments to prove or disprove a hypothesis have an equal chance of failing or succeeding, akin to tossing a coin. A pre-conceived belief that a hypothesis is unlikely to be proven correct should not form the basis of rejection of such a hypothesis for publication. In this context, hypotheses generated after a thorough literature search to identify knowledge gaps or based on concrete clinical observations on a considerable number of patients (as opposed to random observations on a few patients) are more likely to be acceptable for publication by peer-reviewed journals. Also, hypotheses should be considered for publication or rejection based on their implications for science at large rather than whether the subsequent experiments to test them end up with results in favour of or against the original hypothesis.

Hypotheses form an important part of the scientific literature. The COVID-19 pandemic has reiterated the importance and relevance of hypotheses for dealing with public health emergencies and highlighted the need for evidence-based and ethical hypotheses. A good hypothesis is testable in a relevant study design, backed by preliminary evidence, and has positive ethical and clinical implications. General medical journals might consider publishing hypotheses as a specific article type to enable more rapid advancement of science.

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions:

- Data curation: Gasparyan AY, Misra DP, Zimba O, Yessirkepov M, Agarwal V, Kitas GD.

Science and the scientific method: Definitions and examples

Here's a look at the foundation of doing science — the scientific method.

The scientific method

Hypothesis, theory and law, a brief history of science, additional resources, bibliography.

Science is a systematic and logical approach to discovering how things in the universe work. It is also the body of knowledge accumulated through the discoveries about all the things in the universe.

The word "science" is derived from the Latin word "scientia," which means knowledge based on demonstrable and reproducible data, according to the Merriam-Webster dictionary . True to this definition, science aims for measurable results through testing and analysis, a process known as the scientific method. Science is based on fact, not opinion or preferences. The process of science is designed to challenge ideas through research. One important aspect of the scientific process is that it focuses only on the natural world, according to the University of California, Berkeley . Anything that is considered supernatural, or beyond physical reality, does not fit into the definition of science.

When conducting research, scientists use the scientific method to collect measurable, empirical evidence in an experiment related to a hypothesis (often in the form of an if/then statement) that is designed to support or contradict a scientific theory .

"As a field biologist, my favorite part of the scientific method is being in the field collecting the data," Jaime Tanner, a professor of biology at Marlboro College, told Live Science. "But what really makes that fun is knowing that you are trying to answer an interesting question. So the first step in identifying questions and generating possible answers (hypotheses) is also very important and is a creative process. Then once you collect the data you analyze it to see if your hypothesis is supported or not."

The steps of the scientific method go something like this, according to Highline College :

- Make an observation or observations.

- Form a hypothesis — a tentative description of what's been observed, and make predictions based on that hypothesis.

- Test the hypothesis and predictions in an experiment that can be reproduced.

- Analyze the data and draw conclusions; accept or reject the hypothesis or modify the hypothesis if necessary.

- Reproduce the experiment until there are no discrepancies between observations and theory. "Replication of methods and results is my favorite step in the scientific method," Moshe Pritsker, a former post-doctoral researcher at Harvard Medical School and CEO of JoVE, told Live Science. "The reproducibility of published experiments is the foundation of science. No reproducibility — no science."

Some key underpinnings to the scientific method:

- The hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable, according to North Carolina State University . Falsifiable means that there must be a possible negative answer to the hypothesis.

- Research must involve deductive reasoning and inductive reasoning . Deductive reasoning is the process of using true premises to reach a logical true conclusion while inductive reasoning uses observations to infer an explanation for those observations.

- An experiment should include a dependent variable (which does not change) and an independent variable (which does change), according to the University of California, Santa Barbara .

- An experiment should include an experimental group and a control group. The control group is what the experimental group is compared against, according to Britannica .

The process of generating and testing a hypothesis forms the backbone of the scientific method. When an idea has been confirmed over many experiments, it can be called a scientific theory. While a theory provides an explanation for a phenomenon, a scientific law provides a description of a phenomenon, according to The University of Waikato . One example would be the law of conservation of energy, which is the first law of thermodynamics that says that energy can neither be created nor destroyed.

A law describes an observed phenomenon, but it doesn't explain why the phenomenon exists or what causes it. "In science, laws are a starting place," said Peter Coppinger, an associate professor of biology and biomedical engineering at the Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. "From there, scientists can then ask the questions, 'Why and how?'"

Laws are generally considered to be without exception, though some laws have been modified over time after further testing found discrepancies. For instance, Newton's laws of motion describe everything we've observed in the macroscopic world, but they break down at the subatomic level.

This does not mean theories are not meaningful. For a hypothesis to become a theory, scientists must conduct rigorous testing, typically across multiple disciplines by separate groups of scientists. Saying something is "just a theory" confuses the scientific definition of "theory" with the layperson's definition. To most people a theory is a hunch. In science, a theory is the framework for observations and facts, Tanner told Live Science.

The earliest evidence of science can be found as far back as records exist. Early tablets contain numerals and information about the solar system , which were derived by using careful observation, prediction and testing of those predictions. Science became decidedly more "scientific" over time, however.

1200s: Robert Grosseteste developed the framework for the proper methods of modern scientific experimentation, according to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. His works included the principle that an inquiry must be based on measurable evidence that is confirmed through testing.

1400s: Leonardo da Vinci began his notebooks in pursuit of evidence that the human body is microcosmic. The artist, scientist and mathematician also gathered information about optics and hydrodynamics.

1500s: Nicolaus Copernicus advanced the understanding of the solar system with his discovery of heliocentrism. This is a model in which Earth and the other planets revolve around the sun, which is the center of the solar system.

1600s: Johannes Kepler built upon those observations with his laws of planetary motion. Galileo Galilei improved on a new invention, the telescope, and used it to study the sun and planets. The 1600s also saw advancements in the study of physics as Isaac Newton developed his laws of motion.

1700s: Benjamin Franklin discovered that lightning is electrical. He also contributed to the study of oceanography and meteorology. The understanding of chemistry also evolved during this century as Antoine Lavoisier, dubbed the father of modern chemistry , developed the law of conservation of mass.

1800s: Milestones included Alessandro Volta's discoveries regarding electrochemical series, which led to the invention of the battery. John Dalton also introduced atomic theory, which stated that all matter is composed of atoms that combine to form molecules. The basis of modern study of genetics advanced as Gregor Mendel unveiled his laws of inheritance. Later in the century, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen discovered X-rays , while George Ohm's law provided the basis for understanding how to harness electrical charges.

1900s: The discoveries of Albert Einstein , who is best known for his theory of relativity, dominated the beginning of the 20th century. Einstein's theory of relativity is actually two separate theories. His special theory of relativity, which he outlined in a 1905 paper, " The Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies ," concluded that time must change according to the speed of a moving object relative to the frame of reference of an observer. His second theory of general relativity, which he published as " The Foundation of the General Theory of Relativity ," advanced the idea that matter causes space to curve.

In 1952, Jonas Salk developed the polio vaccine , which reduced the incidence of polio in the United States by nearly 90%, according to Britannica . The following year, James D. Watson and Francis Crick discovered the structure of DNA , which is a double helix formed by base pairs attached to a sugar-phosphate backbone, according to the National Human Genome Research Institute .

2000s: The 21st century saw the first draft of the human genome completed, leading to a greater understanding of DNA. This advanced the study of genetics, its role in human biology and its use as a predictor of diseases and other disorders, according to the National Human Genome Research Institute .

- This video from City University of New York delves into the basics of what defines science.