The effectiveness of workplace coaching: a meta-analysis of contemporary psychologically informed coaching approaches

Journal of Work-Applied Management

ISSN : 2205-2062

Article publication date: 21 June 2021

Issue publication date: 5 April 2022

The authors examine psychologically informed coaching approaches for evidence-based work-applied management through a meta-analysis. This analysis synthesized previous empirical coaching research evidence on cognitive behavioral and positive psychology frameworks regarding a range of workplace outcomes, including learning, performance and psychological well-being.

Design/methodology/approach

The authors undertook a systematic literature search to identify primary studies ( k = 20, n = 957), then conducted a meta-analysis with robust variance estimates (RVEs) to test the overall effect size and the effects of each moderator.

The results confirm that psychologically informed coaching approaches facilitated effective work-related outcomes, particularly on goal attainment ( g = 1.29) and self-efficacy ( g = 0.59). Besides, these identified coaching frameworks generated a greater impact on objective work performance rated by others (e.g. 360 feedback) than on coachees' self-reported performance. Moreover, a cognitive behavioral-oriented coaching process stimulated individuals' internal self-regulation and awareness to promote work satisfaction and facilitated sustainable changes. Yet, there was no statistically significant difference between popular and commonly used coaching approaches. Instead, an integrative coaching approach that combines different frameworks facilitated better outcomes ( g = 0.71), including coachees' psychological well-being.

Practical implications

Effective coaching activities should integrate cognitive coping (e.g. combining cognitive behavioral and solution-focused technique), positive individual traits (i.e. strength-based approach) and contextual factors for an integrative approach to address the full range of coachees' values, motivators and organizational resources for yielding positive outcomes.

Originality/value

Building on previous meta-analyses and reviews of coaching, this synthesis offers a new insight into effective mechanisms to facilitate desired coaching results. Frameworks grounded in psychotherapy and positive appear most prominent in the literature, yet an integrative approach appears most effective.

- Workplace coaching

- Coaching psychology

- Meta-analysis

- Psychological well-being

- Learning and development

Wang, Q. , Lai, Y.-L. , Xu, X. and McDowall, A. (2022), "The effectiveness of workplace coaching: a meta-analysis of contemporary psychologically informed coaching approaches", Journal of Work-Applied Management , Vol. 14 No. 1, pp. 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWAM-04-2021-0030

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2021, Qing Wang, Yi-Ling Lai, Xiaobo Xu and Almuth McDowall

Published in Journal of Work-Applied Management . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Introduction

Given the ever-growing popularity of coaching which some populist publications expect to surpass consultancy ( Forbes, 2018 ) as a workplace learning and development (L&D) activity of choice, the effectiveness of coaching has attracted increasing attention from scholars, practitioners and clients. Several meta-analyses (e.g. Jones et al. , 2016 ; Theeboom et al. , 2014 ) have established that taking part in coaching activities has positive effects on individual-level outcomes. Yet, we still know little about “ how ” does coaching work from a psychological perspective ( Bono et al. , 2009 ; Smither, 2011 ); what are the “ active ingredients ” and potential mechanisms that make coaching successful ( Theeboom et al. , 2014 ). Recent meta-analysis ( Graßmann et al. , 2020 ) confirmed the working alliance which refers to the coach–coachee relationship, as an antecedent of desired coaching outcomes. Our meta-analysis aims to synthesize extant psychologically informed coaching research evidence (e.g. cognitive behavioral approaches) to elicit better understanding of potential mechanisms to contribute to the development of work-applied management.

We framed workplace coaching (hereafter coaching) as a facilitative process for the purpose of coachees' L&D and a greater working life (e.g. psychological well-being) through interpersonal interactions between the coach and coachee ( Grant, 2017 ; Passmore and Fillery-Travis, 2011 ). The present analysis only included coaching offered by independent contracted specialists who use a wide variety of behavioral techniques and methods to help the coachee achieve a mutually identified set of goals, including professional performance, personal satisfaction as well as the effectiveness of the coachee's organization within a formally defined coaching agreement ( Kilburg, 1996 , p. 142). Whereas certain organizations often conduct coaching through internal specialists such as in-house human resource (HR) professionals, external coaching engagements has larger influences on coachees' affective learning outcomes and workplace well-being than internal coaching ( Jones et al. , 2018 ). These affective and psychological welfare related outcomes are important determinants of sustainable behavior or performance improvement ( Kraiger et al. , 1993 ). Accordingly, our primary study objective is to investigate whether coaching provided by independent practitioners applying psychologically informed approaches promotes longstanding outcomes.

Our study extends previous meta-analyses by focusing on psychological perspectives, for instance psychotherapy ( Graßmann et al. , 2020 ; Gray, 2006 ) and positive psychology ( Grant and Cavanagh, 2007 ), and draws on compatible paradigms and theoretical constructs to explain potential mechanisms of coaching interventions. Previous analyses (e.g. Jones et al. , 2016 ; Theeboom et al. , 2014 ) outlined several frequently used psychologically informed coaching approaches, including cognitive behavioral coaching (CBC) [1] . Nevertheless, we have sparse evidence on how different coaching approaches compare to one another in terms of outcomes produced ( Athanasopoulou and Dopson, 2018 ; Smither, 2011 ). In addition, we contend that contemporary literature has neglected social complexity in workplace coaching settings; hence, coaches should apply integrative and flexible approaches to acknowledge fluctuating and complex organizational management scenarios ( Shoukry and Cox, 2018 ). Accordingly, our analysis investigated whether an integrative psychological approach (e.g. CBC combined with other psychological approaches) with potentially more comprehensive consideration of individuals' needs and organizational circumstances affects coaching outcomes.

Brief meta-review of previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses

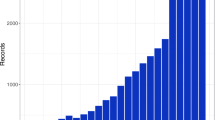

Given the growing number of coaching-focused meta-analyses and systematic reviews referenced above, we undertook a succinct meta-review as summarized in Table 1 to inform distinctions of our analysis.

Most reviews concurred that coaching overall had a positive impact on individuals' workplace learning and performance. Meanwhile, Theeboom et al. 's synthesis ( 2014 ) identified that coaching interventions have significant positive effects on employees' working life and psychological states, including coping mechanisms (e.g. resilience) and well-being. This finding accorded with the contemporary coaching literature suggesting that sustainable behavioral changes should be underpinned by personal life and learning experiences ( Grant, 2014 ; Stelter, 2014 ). Therefore, coachees' personal values and meaning of their life and work are also important for desired coaching outcomes. In addition, three reviews specifically stressed on the professional helping relationship in the coaching dyad ( Graßmann et al. , 2020 ; Lai and McDowall, 2014 ; Sonesh et al. , 2015 ) as central to coaching as a positive process and good outcomes; the focus of working alliance has set a road map for the future research between psychotherapy and coaching.

We noted the following implications for future research. First, there is a need for greater clarity to distinguish approaches to coaching, since synthesized data of previous reviews comprised different types of coaching, such as grouping together internal and external coaching ( Jones et al. , 2016 ), group and peer coaching ( Theeboom et al. , 2014 ), or workplace and life coaching ( Graßmann et al. , 2020 ). Yet there are fundamental differences between coaching modalities ( Jones et al. , 2018 ) including purpose (life or work-related coaching) and contracting (internal or external coaching). Second, all reviews suggested that future research could emphasize sound theoretical constructs, including those derived from psychotherapy or counselling to investigate more clearly articulated models for coaching outcomes. To date, several psychological determinants appear important for the coaching process. For instance, the strength of the working alliance, a concept originating in psychotherapy, has positive impacts on coachees' self-efficacy and self-reflection ( Graßmann et al. , 2020 ). Although these analyses conducted by Jones et al. (2016) and Theeboom et al. (2014) included several primary studies drawn from psychology such as CBC and solution-focused coaching (SFC) [2] , they did not go as far as a comparative evaluation of different approaches, which we took on as a key focus for the present study. Building on these review and synthesis results for a future coaching research agenda, we propose a meta-analytic synthesis of existing psychologically informed empirical evidence. Although we acknowledge the role other disciplines (e.g. adult learning and management) play in coaching practice, a more extensive cross-examination between psychology and other coaching domains was not feasible due to challenges regarding literature searching and screening. This is because many existing coaching studies do not specify coaching designs or paradigms in necessary detail ( Jones et al. , 2016 ). The comprehensive theoretical foundations and explanations of our analysis are presented below.

Psychologically informed approaches to coaching

Given the central importance of psychological theories in previous reviews, we revisit these in the context of contemporary coaching literature. Several theoretical frameworks originating from psychotherapy and positive psychology have been frequently applied in extant coaching practice regardless of concrete empirical evidence for their effectiveness ( Palmer and Lai, 2019 ). Grant (2001) carried out a pioneering literature review of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), addressing identifying negative cognitive patterns and solution-focused therapy (SFT), emphasizing self-developed and future focused plans for behavior change, as L&D interventions for nonclinical population coaching. This review indicated that understanding coachees' socio-cognitive characteristics, such as psychological mindedness, self-awareness and self-regulation, can advance coachees' purposeful behavioral changes. The application of theories in psychotherapy offers a holistic picture of coachees, including their intrinsic motivations, personal history and current life, and may make a significant contribution to coachees' sustainable changes ( Williams et al. , 2002 ). Nevertheless, the workplace coaching usually requires a systematic focus and developmental partnership and often involves a complicated as triadic contracting process among the coach, coachee and organization ( Louis and Fatien Diochon, 2014 ; Smither, 2011 ); hence, theories and techniques in coaching might matter more than in psychotherapy. To revisit the boundaries between coaching and psychotherapy, Grant and Cavanagh (2007) proposed that positive psychology, which is identifying and utilizing positive traits of people, may strengthen coaching outcome, such as workplace satisfaction, performance and well-being can be enhanced. Nevertheless, there is still lack of rigor in many of the claims and much of the published work in coaching. Accordingly, the future coaching research should focus on in what way psychology can contribute to coaching ( Bono et al. , 2009 ) and directly compares the efficacy of different theoretical frameworks and approaches to executive coaching ( Smither, 2011 ).

Outcome criteria for workplace coaching

Outcome criteria in contemporary coaching research have been criticized due to the lack of consistency and validity ( Lai and Palmer, 2019 ); hence, we drew on established criterion models from similar interventions, such as training and learning for coaching evaluations. To build on previous meta-analyses, we combined multi-level training evaluation ( Kraiger et al. , 1993 ) with the Engagement and Well-being Matrix® ( Grant, 2014 ) in the present analysis. Given that expectations of coaching have been expanded to a broader view of working life, including employee relations, engagement, motivation to change and psychological well-being ( Grant, 2014 ), our coaching outcome evaluation criteria across four individual domains are affective, cognitive, behavioral (skills/performance) outcomes and psychological well-being (See Table 2 below).

Do psychologically informed coaching approaches have positive effects on the following learning outcomes; (a) affective; (b) cognitive; (c) skills-based/performance and (d) psychological well-being?

Is there a difference among the effectiveness of various frequently used psychological frameworks such as CBC and SFC on coaching outcomes?

Contextual factors in the coaching process

Despite certain prominent psychologically informed approaches (e.g. CBC) having been widely applied in coaching studies, contextual factors (e.g. organizational characteristics) have been overlooked in research evidence ( Shoukry and Cox, 2018 ). Indeed, workplace coaching requires comprehensive approaches due to a sophisticated triangular relationship between the coach, coachee and organization ( Louis and Fatien Diochon, 2014 ). Therefore, coaching is regarded as a social process where contingent factors including organizational structure, political dynamics and power relationships are important influences on the coaching relationship ( Louis and Fatien Diochon, 2018 ; Shoukry and Cox, 2018 ). Specifically, interpersonal interactions between the coach and coachee were altered by the context and relation-specific scenarios ( de Haan and Nieß, 2015 ; Ianiro et al. , 2015 ), in which a more flexible and integrated coaching process is essential.

Do integrative psychologically informed coaching frameworks have better effects on coaching outcomes than a singular formed coaching framework?

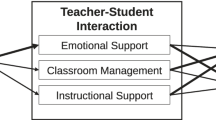

Based on the above, we developed a conceptual model to guide our analysis (See Figure 1 below).

Literature search and screening

We used a systematic search strategy to identify relevant peer-reviewed papers, unpublished doctoral theses and conference proceedings ( Denyer and Tranfield, 2011 ). Search terms associated with psychologically informed coaching approaches (e.g. cogniti* and coaching) and psychological assessments (e.g. psychometric* and coaching) were used across eight databases, such as PsyINFO and Business Source Complete. Inclusion criteria were (1) written in English; (2) published between 1995 and 2018; (3) empirical quantitative trial settings with clear research methods, participants, evaluations and outcomes; (4) focused external one-on-one workplace coaching; (5) clearly stated psychologically informed coaching approaches and frameworks, such as CBC, SFC GROW [3] and so forth. Please see Figure 2 for the flow chart of literature search process.

A total of 20 studies ( k = 20, n = 957, 63 effect sizes) meeting the above criteria were included in the final review. Overall, most of the included studies were conducted in English speaking countries (e.g. UK, USA and Australia) and continental Europe (e.g. Italy, Netherlands, Spain, etc.). This aligns to a recent global coaching consumer report by the International Coach Federation (ICF, 2017) , indicating USA and Europe as established coaching markets. A comparative analysis between countries was out of scope due to insufficient numbers of primary studies. An overview of the included studies is displayed in Table 3 .

Calculating the effect sizes

We used Hedges's g as the indicator of effect size, which adjusts the small sample overestimation bias of Cohen's d ( Hedges, 1981 ) and is usually interpreted as the standardized mean difference calculated by using the means, standard deviations and sample sizes of treatment and comparison groups. In cases when the above statistic information was not available, we estimated this indicator by transforming F , Z or t values according to the formula described in Card (2011 , p. 97).

There are three types of research design in the present meta-analysis: (1) posttest only with control design (POWC), (b) single group pretest–posttest design (SGPP) and (c) pretest–posttest with control design (PPWC). For those which employed two cohorts with nonequivalent control design (e.g. MacKie, 2014 ; MacKie, 2015 ), we aggregated the precoaching and postcoaching data of the first coaching group and the waitlist first group and treated them as SGPP. Accordingly, we employed different formulas to calculate the effect sizes and variances for each research design as illustrated in Table 4 . For POWC research design studies, the effect size was defined as the difference between the mean posttest scores of the treatment and control groups divided by the pooled standard deviation of the two groups ( Carlson and Schmidt, 1999 , p. 852, 855; Rubio-Aparicio et al. , 2017 , p. 2059). For SGPP research design studies, the effect size was defined as the average pretest-follow-up change, divided by the pretest standard deviation ( Morris and DeShon, 2002 , p.114; Rubio-Aparicio et al. , 2017 , p. 2059). Finally, for PPWC research design studies, the effect size index was computed as the difference between the average pretest-follow-up change of the experimental and control groups, divided by a pooled estimate of the pretest standard deviations of the two groups ( Morris, 2008 , p. 369; Rubio-Aparicio et al. , 2017 , p. 2060). For SGPP and PPWC, Pearson correlation coefficient between the pretest and follow-up measures must be available to estimate the variance. As this information was seldom reported in the studies, a value of 0.70 was assumed for r , as recommended by Rosenthal (1991) .

Meta-analysis with robust variance estimates

When a study provides multiple effect size estimates, a traditional approach is to aggregate effect sizes drawn from the same study ( Borenstein et al. , 2009 ). However, this method usually eliminates the possibility of comparing multiple levels of a moderator within a single study. To overcome this limitation, the present study conducted a meta-analysis with robust variance estimates (RVEs; Hedges et al. , 2010 ), which can comprehensively analyze all the effect sizes and effectively accommodate the multiple sources of dependencies. Considering 70.00% (14 out of 20 studies) of the studies provided multiple effect sizes, this study employed the correlated effects weighting scheme for RVE, with the default assumed correlation ( r = 0.80) among dependent effect sizes within each study.

Testing overall effects and moderators

To test the overall effect size and the effects of each moderator, we conducted an intercept-only random-effects meta-regression model with RVE using the R package, robumeta ( Fisher and Tipton, 2015 ). The intercept of this model can be interpreted as the precision weighted overall effect size, adjusted for correlated-effect dependencies. Categorical moderators (e.g. coaching method and outcome category) were first dummy coded and then entered into meta-regression equations. To test whether there were significant differences across all levels of each moderator, we conducted approximate Hotelling-Zhang with small sample correction tests using the R package clubSandwhich ( Pustejovsky, 2015 ). This test produced an F- value, an atypical degree of freedom, and a p -value that indicated the significance of moderating effect.

Examining publication bias

Publication bias refers to the tendency of studies that report small or nonsignificant effects to be underrepresented in the published literature. Since publication bias analyses cannot be performed with RVEs, we used the R package MAd ( Del Re and Hoyt, 2010 ) to aggregate dependent effect sizes with a prespecified correlation ( r = 0.5) ( Borenstein et al. , 2009 ). Then, we conducted the Orwin's fail-safe N analysis ( Orwin, 1983 ) and the trim-and-fill analysis ( Duval and Tweedie, 2000 ) with the R package metafor ( Viechtbauer, 2010 ), based on the aggregated 20 effect sizes (one effect size per study). Orwin's fail-safe N indicates how many studies with null results ( g = 0) would have to be added to reduce the present average effect size to a trivial level ( g = 0.1, Hyde and Linn, 2006 ). Trim and Fill analysis indicated how many missing studies were needed to make the funnel plot symmetrical ( Duval and Tweedie, 2000 ). The results indicated that it takes 87 overlooked studies with effect sizes of 0 to reduce our results to a trivial level. Furthermore, the results of Trim and Fill analysis implied that no studies were added in the funnel plot ( Figure 3 ). Taken together, publication bias was probably not a problem in this meta-analysis.

The effectiveness of psychologically informed coaching approaches on workplace outcomes

With regards to our first research question, the results of meta-regression with RVEs indicated a moderately positive effect across outcomes ( g = 0.51, 95% CI, 0.35–0.66 and p < 0.01). However, the relatively large effect size of goal attainment in Grant's (2010, g = 2.06) study prompted us to perform a sensitivity analysis; namely, the above analysis was repeated while excluding the result of this outcome. The overall effect size dropped slightly but remained significant ( g = 0.48, 95% CI, 0.33–0.64 and p < 0.01), indicating that the overall effect was not altered when Grant's (2001) study was excluded.

The effectiveness of various frequently used psychological coaching frameworks

The large amount of heterogeneity in the effect sizes ( T 2 = 0.12 and I 2 = 79.37) suggested there may be meaningful differences that could be further explored through moderator analyses. Table 5 contains effect size estimates for each level of moderator analyses.

We first examined whether different coaching methods (CBC, GROW, PPC and integrative coaching) varied in their effects on outcomes addressing the second research question. The results indicated positive effects across all coaching methods: CBC ( g = 0.39, 95% CI, −0.03–0.82 and p = 0.07), GROW ( g = 0.44, 95% CI, 0.18–0.70 and p < 0.01), PPC ( g = 0.57, 95% CI, 0.28–0.85 and p = 0.02) and integrative ( g = 0.71, 95% CI, 0.21–1.21 and p = 0.02). Overall, we did not find evidence that coaching method significantly moderated coaching effect, F (3, 6.27) = 0.78 and p = 0.54.

Integrative vs singular psychologically informed coaching frameworks

Addressing our third review question, we compared the effect size between studies employing integrative coaching methods and those based on a single coaching method. The average effect size for integrative coaching methods ( g = 0.71, 95% CI, 0.21–1.21 and p = 0.02) was higher than for single coaching method ( g = 0.45, 95% CI, 0.27–0.64 and p < 0.01), yet the difference was not significant, F (1, 6.15) = 1.41 and p = 0.28.

The effects of psychologically informed coaching approaches on evaluative outcomes

The results demonstrated that coaching constructs, informed by psychotherapy and positive psychology, had an overall effective impact on all evaluative outcomes including individuals' cognitive and affective learning outcomes, objective work performance improvement and psychological well-being. The effective sizes ranged from g = 0.25 to 1.29. Whereas several previous meta-analyses (e.g. Theeboom et al. , 2014 ) also indicated support for effective coaching outcomes, these syntheses did not differentiate between psychological and nonpsychological coaching approaches as well as formats of coaching (e.g. peer and group coaching). Our analysis makes the distinction that psychologically informed approaches contribute to external workplace coaching processes and outcomes. This present analysis revealed that psychological coaching approaches had significant impacts particularly on goal-related outcomes; this finding reflects on Bono et al. 's (2009) comparative analysis between psychologist and nonpsychologist coaches that the former tended to set specific “goals” triggering behavioral changes. In addition, our analysis identified that psychologically informed coaching approaches had substantial impacts on individuals' cognitive learning outcomes; for instance, meta-cognitive skills which process and organize information for the development and to plan, monitor and revise goal-oriented behaviors ( Brown et al. , 1983 ; Kraiger et al. , 1993 ). Considering that coaching has been described as a reflective process to simulate people's self-awareness ( Passmore and Travis, 2011 ), our analysis tallied with literature of learning that individuals' internal self-regulation and cognition stimulate purposeful mental (internal) and behavioral (external) changes (e.g. goal-attainment) through a continuous cognitive process ( Anderson, 1982 ).

The second largest effect size in our analysis was the impact on coachees' affective outcomes ( g = 0.44), such as work attitudes, organizational commitment, job satisfaction and intention to leave. Workplace coaching is a type of investment in people through supporting coachees' professional and personal development. This sort of social support either from the organization or supervisors indeed reinforced coachees' satisfaction of the coaching process ( Zimmermann and Antoni, 2020 ) and therefore encouraged their motivation and efforts to change ( Baron and Morin, 2010 ; Bozer and Jones, 2018 ). Our analysis indicated psychologically informed coaching, which provides a more holistic facilitation of coachees by understanding their internal motivators, emotions and unconscious assumptions ( Gray, 2006 ), increased coachees' organizational commitment and job satisfaction listed above. Therefore, our study further clarifies that coaching approaches addressing self-directed process and underlying cognitive issues advanced coachees' perceived social support and attitude to organizational objectives.

Coachees' psychological well-being evaluative outcomes took place the third largest effect size ( g = 0.28) in our analysis. This finding is an incremental contribution as previous meta-analyses mainly emphasized workplace performance or behavioral related evaluative indicators. Instead, we recognized people's quality of working life and challenges as important indicators for a sustainable behavioral or performance change ( Grant, 2014 ). Our analysis indicated psychologically informed coaching emphasizes improvement of coachees' mental health, resilience, positive moods and reducing stress and psychopathologies ( Grant, 2014 ; Yu et al. , 2008 ). Interestingly, most of the studies that examined psychological health outcomes adopted an integrative coaching approach ( Grant, 2014 ; Grant et al. , 2009 , 2014 ; Weinberg, 2016 ; Yu et al. , 2008 ). This finding is distinct to some contemporary coaching literature that advocates theories in positive psychology are the predominant ingredient to flourish individuals' workplace experiences and satisfaction ( Biswas-Diener and Dean, 2007 ; Biswas-Diener, 2010 ). This synthesis result informs us that the combined approach of coaching may offer a comprehensive pathway to understand the full range of coachees' emotions, feelings and passion for life to promote their mental health.

Lastly, psychologically informed coaching had a positive impact on objective work performance rated by others ( g = 0.24). Interestingly, coachees' self-reported work performance was not significantly improved after coaching. A possible explanation for this finding could be due to the self-reporting bias in interventional studies ( Kumar and Yale, 2016 ; Rosenman et al. , 2011 ). The reference standards of respondents' judgment may change over time as coachees gain more realistic understating of respective strengths and weaknesses, a beta change ( Millsap and Hartog, 1988 ). A similar phenomenon was noted in Mackie's study ( 2014 ) where senior managers in the experimental group reported less improvement in their leadership development after receiving coaching, although their “actual” improvements in leadership behaviors were better than participants in the control group, evaluated by objective 360-degree assessment.

The outcome equivalence of psychologically informed coaching frameworks

To offer a further insight of psychologically informed coaching approaches, we carried out a comparative analysis among all identified coaching constructs, namely, CBC, GROW, positive psychology coaching (PPC [4] ) and integrative approaches (e.g. CBC combined with SFC). Our analysis suggests that the effect sizes of different psychologically informed coaching approaches were homogeneous. Precisely, there was no particular psychological approach to coaching more effective than others in terms of evaluative outcomes. This result is aligned with “outcome equivalence” in therapeutic research that there is no significant distinction in effectiveness between different approaches and techniques ( Ahn and Wampold, 2001 ). Meanwhile, this synthesis clarifies the long-standing debate on coaching approaches by indicating that none of the popular and commonly used constructs are prominent than others ( Smither, 2011 ).

Whereas CBC had the most empirical data and largest sample size in our included papers, we found lower effects of CBC on desired coaching outcomes ( g = 0.39) compared with other psychological frameworks ( g = 0.55), although the difference was not significant. A possible explanation is that CBC, which combines cognitive-behavioral, imaginal and problem-solving techniques and strategies to enable clients to overcome blocks to change and achieve their goals ( Palmer and Szymanska, 2019 ), may require a prolonged coaching program to cultivate or transfer the values and meanings of certain situations. Other psychologically informed coaching frameworks, such as SFC and PPC, are more outcome-oriented, competence-based and goal-focused procedures, and they may demonstrate effects in the short term that satisfy expectations in workplace coaching settings. We cannot rule out the possibility that a particular psychologically informed coaching framework generates better outcomes than other frameworks. However, we were not able to conduct a meta-analysis between each framework due to the small number of empirical studies up-to-date. Future research could investigate whether specific psychological approaches are more strongly associated with specific coaching effects.

Integrative coaching frameworks may work better than a single approach

Whereas recent coaching literature implied that a singular formed coaching framework understates the complexity of coaching processes ( Shoukry and Cox, 2018 ), our study discovered several psychologically informed coaching frameworks were commonly used in an integrative way; for example, CBC was often combined with SFC (e.g. Grant, 2014 ). Our meta-analysis results revealed that the effectiveness of using an integrative approach ( g = 0.71) was stronger than a singular formed framework ( g = 0.45) on evaluative outcomes, though the difference was not significant. However, we note that only six studies ( n = 233) used an integrating approach and 14 studies ( n = 724) used singular formed models in our included papers. The discrepancy of study numbers and sample sizes was a limitation for robustly comparing these two groups, and yet integrative frameworks still demonstrated stronger impacts on evaluative outcomes. This result indicates that a more comprehensive approach may have addressed the social complexity in coaching process and captured a thorough picture of coachees' and organizational characteristics to facilitate desired coaching outcomes ( Shoukry and Cox, 2018 ). Overall, our meta-analysis indicates the positive impact of psychologically informed coaching approaches on relevant outcomes. However, we do not suggest a degree in psychology as prerequisite for all coaches. Rather, we advocate that a sound understanding of cognitive-behavioral-based science and appreciation of the coachee's work-related context is a helpful basis for effective coaching processes.

Future research directions and practical implications

This study takes an initial step to synthesize relevant studies and confirms the role psychology plays in promoting certain workplace coaching outcomes; we draw out several implications for future research following a number of limitations. In addition to the common suggestions in previous meta-analyses and systematic reviews demanding more thorough and rigorous studies and assessing longitudinal effects of coaching, we emphasize that, first, explicit coaching constructs or frameworks should be adequately addressed and discussed in future research since large numbers of existing empirical studies did not specify coaching design in sufficient detail. Second, a transparent data analysis and presentation is crucial as we had to disregard several studies due to missing data or unclear clarification from authors. Third, a comparison between psychologically informed approaches and other coaching disciplines (e.g. adult learning or management) might offer more comprehensive understanding of contemporary coaching research evidence on coachees' transformation and growth. Others may also wish to build on our groundwork to additionally investigate in what way coaches' cultural backgrounds and qualification impact on coaching outcome in both the internal and external coaching setting.

In terms of practical implications, we suggest that using integrative psychologically informed coaching frameworks with consideration of individual differences and social complexity in organizations is important. Our meta-analysis points out outcome equivalence of contemporary commonly used psychologically informed coaching frameworks (including CBC, SFC and PPC), thus corresponding with recent coaching practice trend that workplace coaching is associated with complex social factors. In other words, a combined approach may facilitate greater desirable outcomes. Our purpose is not to claim that applying psychological frameworks is the exclusive influential factor in coaching but rather to promote evidence-based practice by integrating scientific evidence of psychology. As the first meta-analysis of coaching that focuses on one specific theoretical domain, psychology, our review results indeed disclose that future practice need to pay more attention to the coaching process rather than use one particular coaching framework. Our review results can be considered a benchmark for coaches to reflect on their practice to facilitate sustainable coaching outcomes, for instance, whether coaches integrate coachees' cognitive coping, positive traits and strengths as well as social dynamics in the coachee's work environment. In addition, this analysis offers coaches a preliminary guideline to review whether their coaching evaluations consist of comprehensive angles, such as affective and cognitive learning, performance-related outcomes and psychological states.

Conceptual framework of the present meta-analysis

Funnel plot

A meta-review of contemporary meta-analyses and systematic reviews on coaching

Proposed coaching evaluation criteria framework

Characteristics of psychologically informed studies and nonpsychologically informed studies included in this meta-analysis

Note(s) : k = number of studies; n = number of correlations; F = HTZ-F test comparing the levels of a given moderator. A = affective outcomes (e.g. organizational commitment, satisfaction and turn over intention); B1 = general perceived efficacy and other cognitive outcomes (e.g. self-awareness, self-efficacy, attribution and self-regulation); B2 = goal-attainment (e.g. goal setting and goal attainment); C1 = self-rated performance; C2 = other-rated performance (e.g. 360-degree multifactor evaluation) and D = workplace well-being (e.g. burn out, stress and anxiety)

CBC is an integrative approach which combines the use of cognitive, behavioral, imaginal and problem-solving techniques and strategies within a cognitive behavioral framework to enable coachees to achieve their realistic goals ( Palmer and Szymanska, 2019 , p. 108).

SFC is an outcome-oriented, competence-based approach to coaching. It helps coachees to achieve their preferred outcomes by evoking and co-constructing solutions to their problems ( O'Connell and Palmer, 2019 , p. 270).

The GROW model is grounded in behavioral science as a structured, process-derived relationship between a coach and coachee or group which includes the four action-focused stage: goal, reality, options and way forward ( Passmore, 2018 , pp. 99–101).

PPC is a scientifically-rooted approach to helping clients increase well-being, enhance and apply strengths, improve performance and achieve valued goals ( Boniwell and Kauffman, 2018 , p. 153).

Ahn , H.N. and Wampold , B.E. ( 2001 ), “ Where oh where are the specific ingredients? A meta-analysis of component studies in counseling and psychotherapy ”, Journal of Counseling Psychology , Vol. 48 No. 3 , pp. 251 - 257 .

Anderson , J.R. ( 1982 ), “ Acquisition of cognitive skill ”, Psychological Review , Vol. 8 No. 4 , pp. 369 - 406 .

Athanasopoulou , A. and Dopson , S. ( 2018 ), “ A systematic review of executive coaching outcomes: is it the journey or the destination that matters the most? ”, The Leadership Quarterly , Vol. 29 No. 129 , pp. 70 - 88 .

Baron , L. and Morin , L. ( 2010 ), “ The impact of executive coaching on self-efficacy related to management soft-skills ”, Leadership and Organization Development Journal , Vol. 31 No. 1 , pp. 18 - 38 .

Biswas-Diener , R. and Dean , B. ( 2007 ), Positive Psychology Coaching: Putting the Science of Happiness to Work for Your Clients , John Wiley & Sons , New Jersey .

Biswas-Diener , R. ( 2010 ), Practicing Positive Psychology Coaching: Assessment, Diagnosis, and Intervention , John Wiley & Sons , New Jersey .

Blackman , A. , Moscardo , G. and Gray , D.E. ( 2016 ), “ Challenges for the theory and practice of business coaching: a systematic review of empirical evidence ”, Human Resource Development Review , Vol. 15 No. 4 , pp. 459 - 486 .

Boniwell , H. and Kauffman , C. ( 2018 ), “ The positive psychology approach to coaching ”, in Cox , E. , Bachkirova , T. and Clutterbuck , D. (Eds), The Complete Handbook of Coaching , 2nd ed . , SAGE , London , pp. 153 - 166 .

Bono , J.E. , Purvanova , R.K. , Towler , A.J. and Peterson , D.B. ( 2009 ), “ A survey of executive coaching practices ”, Personnel Psychology , Vol. 62 No. 2 , pp. 361 - 404 .

Borenstein , M. , Hedges , L.V. , Higgins , J.P. and Rothstein , H.R. ( 2009 ), Introduction to Meta-Analysis , Wiley , New Jersey, NJ .

Bozer , G. and Jones , R.J. ( 2018 ), “ Understanding the factors that determine workplace coaching effectiveness: a systematic literature review ”, European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology , Vol. 27 No. 3 , pp. 342 - 361 .

Bozer , G. and Sarros , J.C. ( 2012 ), “ Examining the effectiveness of executive coaching on coachees' performance in the Israeli context ”, International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring , Vol. 10 No. 1 , pp. 14 - 32 .

Bright , D. and Crockett , A. ( 2012 ), “ Training combined with coaching can make a significant difference in job performance and satisfaction ”, Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice , Vol. 5 No. 1 , pp. 4 - 21 .

Brown , A.L. , Bransford , J.D. , Ferrara , R.A. and Campione , J. ( 1983 ), “ Learning, understanding, and remembering ”, Mussen , P.H. , Flavell , J.H. and Markman , E.M. (Eds), Handbook of Child Psychology , Vol. 3 , pp. 77 - 167 .

Burke , D. and Linley , P.A. ( 2007 ), “ Enhancing goal self-concordance through coaching ”, International Coaching Psychology Review , Vol. 2 No. 1 , pp. 62 - 69 .

Burt , D. and Talati , Z. ( 2017 ), “ The unsolved value of executive coaching: a meta-analysis of outcomes using randomised control trail studies ”, International Journal of Evidence-Based Coaching and Mentoring , Vol. 15 No. 2 , pp. 17 - 24 .

Card , N.A. ( 2011 ), Applied Meta-Analysis for Social Science Research , Guilford Press , New York, NY .

Carlson , K.D. and Schmidt , F.L. ( 1999 ), “ Impact of experimental design on effect size: findings from the research literature on training ”, Journal of Applied Psychology , Vol. 84 , pp. 851 - 862 .

Cerni , T. , Curtis , G.J. and Colmar , S. ( 2010a ), “ Increasing transformational leadership by developing leaders' information‐processing systems ”, Journal of Leadership Studies , Vol. 4 No. 3 , pp. 51 - 65 .

Cerni , T. , Curtis , G.J. and Colmar , S.H. ( 2010b ), “ Executive coaching can enhance transformational leadership ”, International Coaching Psychology Review , Vol. 5 No. 1 5 , pp. 81 - 85 .

David , O.A. , Ionicioiu , I. , Imbăruş , A.C. and Sava , F.A. ( 2016 ), “ Coaching banking managers through the financial crisis: effects on stress, resilience, and performance ”, Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy , Vol. 34 No. 4 , pp. 267 - 281 .

de Haan , E. and Nieß , C. ( 2015 ), “ Differences between critical moments for clients, coaches, and sponsors of coaching ”, International Coaching Psychology Review , Vol. 10 No. 1 , pp. 38 - 61 .

Del Re , A.C. and Hoyt , W.T. ( 2010 ), “ MAd: meta-analysis with mean differences (R package version 0.8–2) ”, available at: http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MAd .

Denyer , D. and Tranfield , D. ( 2011 ), “ Producing a systematic review ”, in Buchanan , D. and Bryman , A. (Eds), The Sage Handbook of Organisational Research Methods , 2nd ed , SAGE , London , pp. 671 - 689 .

Duval , S. and Tweedie , R. ( 2000 ), “ Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis ”, Biometrics , Vol. 56 , pp. 455 - 463 .

Evers , W.J. , Brouwers , A. and Tomic , W. ( 2006 ), “ A quasi-experimental study on management coaching effectiveness ”, Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research , Vol. 58 No. 3 , pp. 174 - 182 .

Fisher , Z. and Tipton , E. ( 2015 ), “ Robumeta: an R-package for robust variance estimation in meta-analysis ”, available at: http://arxiv.org/abs/1503.02220 .

Forbes ( 2018 ), “ 15 trends that will redefine executive coaching in the next decade ”, available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbescoachescouncil/2018/04/09/15-trends-that-will-redefine-executive-coaching-in-the-next-decade/#36ba0f476fc9 ( accessed 1 April 2021 ).

Grant , A.M. ( 2001 ), Toward a Psychology of Coaching: The Impact of Coaching on Metacognition, Mental Health and Goal Attainment , Doctoral thesis , Coaching Psychology Unit, University of Sydney , Sydney .

Grant , A.M. ( 2014 ), “ The efficacy of executive coaching in times of organisational change ”, Journal of Change Management , Vol. 14 No. 2 , pp. 258 - 280 .

Grant , A.M. ( 2017 ), “ The third ‘generation’ of workplace coaching: creating a culture of quality conversations ”, Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice , Vol. 10 No. 1 , pp. 37 - 53 .

Grant , A.M. and Cavanagh , M.J. ( 2007 ), “ Evidence‐based coaching: flourishing or languishing? ”, Australian Psychologist , Vol. 42 No. 4 , pp. 239 - 254 .

Grant , A.M. , Curtayne , L. and Burton , G. ( 2009 ), “ Executive coaching enhances goal attainment, resilience and workplace well-being: a randomised controlled study ”, The Journal of Positive Psychology , Vol. 4 No. 5 , pp. 396 - 407 .

Grant , A.M. , Green , L.S. and Rynsaardt , J. ( 2010 ), “ Developmental coaching for high school teachers: executive coaching goes to school ”, Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research , Vol. 62 No. 3 , pp. 151 - 168 .

Gray , D. ( 2006 ), “ Executive coaching: towards a dynamic alliance of psychotherapy and transformative learning processes ”, Management Learning , Vol. 37 No. 4 , pp. 475 - 497 .

Graßmann , C. , Schölmerich , F. and Schermuly , C. ( 2020 ), “ The relationship between working alliance and client outcomes in coaching: a meta-analysis ”, Human Relations , Vol. 73 No. 1 , pp. 35 - 58 .

Grover , S. and Furnham , A. ( 2016 ), “ Coaching as a developmental intervention in organisations: a systematic review of its effectiveness and the mechanisms underlying it ”, PloS One , Vol. 11 No. 7 , e0159137 .

Hedges , L.V. ( 1981 ), “ Distribution theory for glass's estimator of effect size and related estimators ”, Journal of Educational Statistics , Vol. 6 , pp. 107 - 128 .

Hedges , L.V. , Tipton , E. and Johnson , M.C. ( 2010 ), “ Robust variance estimation in meta-regression with dependent effect size estimates ”, Research Synthesis Methods , Vol. 1 , pp. 39 - 65 .

Hyde , J.S. and Linn , M.C. ( 2006 ), “ Gender similarities in mathematics and science ”, Science , Vol. 314 No. 5799 , pp. 599 - 600 .

Ianiro , P.M. , Lehmann-Willenbrock , N. and Kauffeld , S. ( 2015 ), “ Coaches and clients in action: a sequential analysis of interpersonal coach and client behavior ”, Journal of Business and Psychology , Vol. 30 No. 3 , pp. 435 - 456 .

International Coach Federation ( 2017 ), “ Global consumer awareness study ”, available at: https://cplatform-files.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/resources/ICF_2017_Survey.pdf ( accessed 21 April 2021 ).

Jones , R. , Woods , S. and Guillaume , Y. ( 2016 ), “ The effectiveness of workplace coaching: a meta-analysis of learning and performance outcomes from coaching ”, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology , Vol. 89 No. 2 , pp. 249 - 277 .

Jones , R.J. , Woods , S.A. and Zhou , Y. ( 2018 ), “ Boundary conditions of workplace coaching outcomes ”, Journal of Managerial Psychology , Vol. 33 Nos 7/8 , pp. 475 - 496 .

Kraiger , K. , Ford , J.K. and Salas , E. ( 1993 ), “ Application of cognitive, skill-based, and affective theories of learning outcomes to new methods of training evaluation ”, Journal of Applied Psychology , Vol. 78 No. 2 , pp. 311 - 328 .

Kilburg , R. ( 1996 ), “ Toward a conceptual understanding and definition of executive coaching ”, Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research , Vol. 482 , pp. 134 - 144 .

Kumar , C.S. and Yale , S.S. ( 2016 ), “ Identifying and eliminating bias in interventional research studies – a quality indicator ”, International Journal of Contemporary Medical Research , Vol. 3 No. 6 , pp. 1644 - 1648 .

Ladegard , G. and Gjerde , S. ( 2014 ), “ Leadership coaching, leader role-efficacy, and trust in subordinates. A mixed methods study assessing leadership coaching as a leadership development tool ”, Leadership Quarterly , Vol. 25 No. 4 , pp. 631 - 646 .

Lai , Y. and McDowall , A. ( 2014 ), “ A systematic review (SR) of coaching psychology: focusing on the attributes of effective coaching psychologists ”, International Coaching Psychology Review , Vol. 9 No. 2 , pp. 120 - 136 .

Lai , Y. and Palmer , S. ( 2019 ), “ Psychology in executive coaching: an integrated literature review ”, Journal of Work-Applied Management , Vol. 11 No. 2 , pp. 143 - 164 .

Louis , D. and Fatien Diochon , P. ( 2014 ), “ Educating coaches to power dynamics: managing multiple agendas within the triangular relationship ”, Journal of Psychological Issues in Organizational Culture , Vol. 5 No. 2 , pp. 31 - 47 .

Louis , D. and Fatien Diochon , P. ( 2018 ), “ The coaching space: a production of power relationships in organizational settings ”, Organization , Vol. 25 No. 6 , pp. 710 - 731 .

MacKie , D. ( 2014 ), “ The effectiveness of strength-based executive coaching in enhancing full range leadership development: a controlled study ”, Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research , Vol. 66 No. 2 , pp. 118 - 137 .

MacKie , D. ( 2015 ), “ The effects of coachee readiness and core self-evaluations on leadership coaching outcomes: a controlled trial ”, Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice , Vol. 8 No. 2 , pp. 120 - 136 .

Markus , I. ( 2016 ), “ Efficacy of immunity-to-change coaching for leadership development ”, The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science , Vol. 52 No. 2 , pp. 215 - 230 .

Millsap , R.E. and Hartog , S.B. ( 1988 ), “ Alpha, beta, and gamma change in evaluation research: a structural equation approach ”, Journal of Applied Psychology , Vol. 73 No. 3 , pp. 574 - 584 .

Morris , S.B. ( 2008 ), “ Estimating effect sizes from pretest-posttest-control group designs ”, Organizational Research Methods , Vol. 11 , pp. 364 - 386 .

Morris , S.B. and DeShon , R.P. ( 2002 ), “ Combining effect size estimates in meta-analysis with repeated measures and independent-groups designs ”, Psychological Methods , Vol. 7 , pp. 105 - 125 .

Nielsen , K.J. , Kines , P. , Pedersen , L.M. , Andersen , L.P. and Andersen , D.R. ( 2015 ), “ A multi-case study of the implementation of an integrated approach to safety in small enterprises ”, Safety Science , Vol. 71 , pp. 142 - 150 .

Orwin , R.G. ( 1983 ), “ A fail-safe N for effect size in meta-analysis ”, Journal of Educational Statistics , Vol. 8 No. 2 , pp. 157 - 159 .

O'Connell , B. and Palmer , S. ( 2019 ), “ Solution-focused coaching ”, in Palmer , S. and Whybrow , A. (Eds), The Handbook of Coaching Psychology: A Guide for Practitioners , 2nd ed. , Routledge , New York, NY , pp. 270 - 281 .

Palmer , S. and Szymanska , K. ( 2019 ), “ Cognitive behavioural coaching: an integrative approach ”, in Palmer , S. and Whybrow , A. (Eds), The Handbook of Coaching Psychology: A Guide for Practitioners , 2nd ed. , Routledge , New York, NY , pp. 108 - 127 .

Passmore , J. ( 2018 ), “ Behavioural coaching ”, in Palmer , S. and Whybrow , A. (Eds), The Handbook of Coaching Psychology: A Guide for Practitioners , 2nd ed. , Routledge , New York, NY , pp. 99 - 107 .

Passmore , J. and Fillery-Travis , A. ( 2011 ), “ A critical review of executive coaching research: a decade of progress and what's to come ”, Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice , Vol. 4 No. 2 , pp. 70 - 88 .

Pustejovsky , J.E. ( 2015 ), ClubSandwich: Cluster-Robust (Sandwich) Variance Estimators with Smallsample Corrections , R package version 0.0.0.9000 , available at: https://github.com/jepusto/clubSandwich .

Ratiu , L. , David , O.A. and Baban , A. ( 2017 ), “ Developing managerial skills through coaching: efficacy of a cognitive-behavioral coaching program ”, Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy , Vol. 35 , pp. 88 - 110 .

Rosenman , R. , Tennekoon , V. and Hill , L.G. ( 2011 ), “ Measuring bias in self-reported data ”, International Journal of Behavioral Healthcare Research , Vol. 2 No. 2 , pp. 320 - 332 .

Rosenthal , R. ( 1991 ), Meta-analytic Procedures for Social Research , Rev. ed , Sage , Newbury Park .

Rubio-Aparicio , M. , Marin-Martinez , F. , Sanchez-Meca , J. and Lopez-Lopez , J.A. ( 2017 ), “ A methodological review of meta-analyses of the effectiveness of clinical psychology treatments ”, Behavior Research Methods , Vol. 50 , pp. 2057 - 2073 .

Sherlock-Storey , M. , Moss , M. and Timson , S. ( 2013 ), “ Brief coaching for resilience during organisational change—an exploratory study ”, The Coaching Psychologist , Vol. 9 No. 1 , pp. 19 - 26 .

Shoukry , H. and Cox , E. ( 2018 ), “ Coaching as a social process ”, Management Learning , Vol. 49 No. 4 , pp. 413 - 428 .

Smither , J.W. ( 2011 ), “ Can psychotherapy research serve as a guide for research about executive coaching? An agenda for the next decade ”, Journal of Business and Psychology , Vol. 26 No. 2 , pp. 135 - 145 .

Sonesh , S.C. , Coultas , C.W. , Lacerenza , C.N. , Marlow , S.L. , Benishek , L.E. and Salas , E. ( 2015 ), “ The power of coaching: a meta-analytic investigation ”, Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice , Vol. 8 No. 2 , pp. 73 - 95 .

Stelter , R. ( 2014 ), “ Third generation coaching: reconstructing dialogues through collaborative practice and a focus on values ”, International Coaching Psychology Review , Vol. 9 No. 1 , pp. 51 - 66 .

Theeboom , T. , Beersma , B. and van Vianen , A. ( 2014 ), “ Does coaching work? A meta-analysis on the effects of coaching on individual level outcomes in an organizational context ”, Journal of Positive Psychology , Vol. 9 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 18 .

Vidal Salazar , M.D. , Ferrón-Vílchez , V. and Cordón‐Pozo , E. ( 2012 ), “ Coaching: an effective practice for business competitiveness ”, Competitiveness Review , Vol. 22 No. 5 , pp. 423 - 433 .

Viechtbauer , W. ( 2010 ), “ Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package ”, Journal of Statistical Software , Vol. 36 , pp. 1 - 48 .

Weinberg , A. ( 2016 ), “ The preventative impact of management coaching on psychological strain ”, International Coaching Psychology Review , Vol. 11 No. 1 , pp. 93 - 105 .

Williams , J.S. and Lowman , R.L. ( 2018 ), “ The efficacy of executive coaching: an empirical investigation of two approaches using random assignment and a switching-replications design ”, Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research , Vol. 70 No. 3 , pp. 227 - 249 .

Williams , K. , Kiel , F. , Doyle , M. and Sinagra , L. ( 2002 ), “ Breaking the boundaries: leveraging the personal in executive coaching ”, in Fitzgerald , C. and Berger , G.J. (Eds), Executive Coaching: Practices and Perspectives , Davies-Black Publishing , Palo Alto, California, CA , pp. 119 - 133 .

Yu , N. , Collins , C.G. , Cavanagh , M. , White , K. and Fairbrother , G. ( 2008 ), “ Positive coaching with frontline managers: enhancing their effectiveness and understanding why ”, International Coaching Psychology Review , Vol. 3 No. 2 , pp. 110 - 122 .

Zimmermann , L.C. and Antoni , C.H. ( 2020 ), “ Activating clients' resources influences coaching satisfaction via occupational self-efficacy and satisfaction of needs ”, Zeitschrift für Arbeits-und Organisationspsychologie A&O , Vol. 64 , pp. 149 - 169 .

Further reading

Finn , F.A. ( 2007 ), Leadership Development through Executive Coaching: The Effects on Leaders' Psychological States and Transformational Leadership Behaviour , Doctoral dissertation , Queensland University of Technology , Brisbane .

Jarzebowski , A. , Palermo , J. and van de Berg , R. ( 2012 ), “ When feedback is not enough: the impact of regulatory fit on motivation after positive feedback ”, International Coaching Psychology Review , Vol. 7 No. 1 , pp. 14 - 32 .

Jones , R.A. , Rafferty , A.E. and Griffin , M.A. ( 2006 ), “ The executive coaching trend: towards more flexible executives ”, Leadership and Organization Development Journal , Vol. 27 No. 7 , pp. 584 - 596 .

Kochanowski , S. , Seifert , C.F. and Yukl , G. ( 2010 ), “ Using coaching to enhance the effects of behavioral feedback to managers ”, Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies , Vol. 17 No. 4 , pp. 363 - 369 .

Luthans , F. and Peterson , S.J. ( 2003 ), “ 360‐degree feedback with systematic coaching: empirical analysis suggests a winning combination ”, Human Resource Management: Published in Cooperation with the School of Business Administration, The University of Michigan and in alliance with the Society of Human Resources Management , Vol. 42 No. 3 , pp. 243 - 256 .

Moen , F. and Allgood , E. ( 2009 ), “ Coaching and the effect on self-efficacy ”, Organization Development Journal , Vol. 27 No. 4 , pp. 69 - 81 .

Nieminen , L.R. , Smerek , R. , Kotrba , L. and Denison , D. ( 2013 ), “ What does an executive coaching intervention add beyond facilitated multisource feedback? Effects on leader self‐ratings and perceived effectiveness ”, Human Resource Development Quarterly , Vol. 24 No. 2 , pp. 145 - 176 .

Peterson , D.B. ( 1993 ), “ Measuring change: a psychometric approach to evaluating individual coaching outcomes ”, Annual Conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology , San Francisco, CA .

Smither , J.W. , London , M. , Flautt , R. , Vargas , Y. and Kucine , I. ( 2003 ), “ Can working with an executive coach improve multisource feedback ratings over time? A quasi‐experimental field study ”, Personnel Psychology , Vol. 56 No. 1 , pp. 23 - 44 .

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Alanna Henderson, who read our first draft and provided constructive comments.

Corresponding author

About the authors.

Qing Wang (PhD, Cpsychol) is a chartered psychologist and accredited coaching psychologist. She is an Associate Professor in Educational and Coaching Psychology and leads Educational Coaching Research Group her current institution. Qing focuses her academic research and practice on coaching psychology in the field of education, including theoretical development, model construction and implementation with educators, teachers and students in various learning settings.

Yi-Ling Lai (PhD, CPsychol) is currently a Lecturer and Programme Director of MSc Organizational Psychology at the Birkbeck University of London. Her main research areas include common factors for an effective coaching alliance and the psychological effects on the workplace coaching outcomes. In addition, Yi-Ling's recent research project focuses on the application of psychological-focused interventions into workplace well-being and resilience. Yi-Ling has published several journal papers and book chapters on the psychological theories in the coaching process.

Xiaobo Xu (PhD) is now a postdoctoral researcher from East China Normal University. His research interest focus on examining how family backgrounds (e.g. family socioeconomic status and parenting styles) and personality traits (e.g. authenticity and openness to experience) interact to influence students' learning outcomes and creative performance. He is also interested in conducting meta-analytic studies on the aforementioned topics.

Almuth McDowall (PhD, CPyschol) is Professor of Organisational Psychology at Birkbeck University of London where she leads her department and is part of her school's executive team. Her research has been funded by the Ministry of Defence, the College of Policing, the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development and the Home Office as well as a range of other funders. Almuth has won awards for her research and her commitment to furthering the practice of psychology in the workplace in the United Kingdom. She is regularly contributing to the media fuelled by her belief that research needs to speak to organizations directly to have impact and contemporary relevance.

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Advertisement

Investigating the Effects of Academic Coaching on College Students’ Metacognition

- Published: 07 January 2021

- Volume 46 , pages 189–204, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Marc Alan Howlett ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2561-6827 1 ,

- Melissa A. McWilliams 1 ,

- Kristen Rademacher 1 ,

- J. Conor O’Neill 2 ,

- Theresa Laurie Maitland 1 ,

- Kimberly Abels 1 ,

- Cynthia Demetriou 3 &

- A. T. Panter 4

3287 Accesses

13 Citations

10 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Academic coaching is an increasingly prevalent form of student support in higher education, although empirical research on the intervention is relatively limited (Robinson, 2015 ). Academic coaching is intended to advance student learning, well-being, and success in a context external but complementary to the classroom (Richman, Rademacher, & Maitland, 2014 ; Robinson, 2015 ). This exploratory study used a randomized control trial design to investigate the effects of academic coaching on college students’ metacognition, a primary component of self-regulated learning. We recruited undergraduates who had not previously participated in academic coaching and randomly assigned them to three groups: in-person academic coaching, online academic coaching, and control. All participants completed a pre- and post-test instrument that included the Metacognitive Awareness Inventory (MAI; Schraw & Dennison, 1994 ). Results showed that students who received academic coaching had increased metacognition as measured by MAI subscales. Increases in metacognitive awareness occurred in both the in-person and online academic coaching conditions. However, repeated measures ANOVAs did not reveal differences between the three conditions. Overall preliminary results suggest that academic coaching may be a promising student support intervention for helping develop college students’ metacognition outside of the classroom environment.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Theories of Motivation in Education: an Integrative Framework

The Impact of Peer Assessment on Academic Performance: A Meta-analysis of Control Group Studies

Is Empathy the Key to Effective Teaching? A Systematic Review of Its Association with Teacher-Student Interactions and Student Outcomes

Data availability.

Alexander, G. & Renshaw, B. (2005). Supercoaching: The missing ingredient for high performance . Random House.

Arendale, D. R. (2010). Access at the crossroads: Learning assistance in higher education. ASHE Higher Education Report, 35 , 1–145. https://doi.org/10.1002/aehe.3506 .

Arendale, D. R. (2004). Mainstreamed academic assistance and enrichment for all students: The historical origins of Learning Assistance Centers. Research for Educational Reform, 9 , 3–21.

Bellman, S., Burgstahler, S., & Hinke, P. (2015). Academic coaching: Outcomes from a pilot group of postsecondary STEM students with disabilities. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 28 , 103–108. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1066319 .

Ben-Eliyahu, A. & Bernacki, M. L. (2015). Addressing complexities in self-regulated learning: A focus on contextual factors, contingencies, and dynamic relations. Metacognition and Learning, 10 , 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-015-9134-6 .

Bettinger, E. & Baker, R. (2014). The effects of student coaching: An evaluation of a randomized experiment in student advising. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 36 (1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373713500523 .

Boekaerts, M. (1995). Self-regulated learning: Bridging the gap between metacognitive and metamotivation theories. Educational Psychologist, 30 (4), 195–200. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3004_4 .

Boekaerts, M. & Corno, L. (2005). Self-regulation in the classroom: A perspective on assessment and intervention. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 54 , 199–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2005.00205.x .

Bruijn-Smolders, M., Timmers, C., Gawke, J., Schoonman, W., & Born, M. (2016). Effective self-regulatory processes in higher education: Research findings and future directions. A systemic review. Studies in Higher Education, 41 (1), 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.915302 .

Capstick, M. K., Harrell-Williams, L. M., Cockrum, C. D., West, & Steven L. (2019). Exploring the effectiveness of academic coaching for academically at-risk college students. Innovative Higher Education, 44 (3), 219–231, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-019-9459-1 .

Claessens, B. van Eerde, W., Rutte, C., & Roe, R. (2007). A review of the time management literature. Personnel Review, 36 (2), 255–276. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480710726136 .

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd edition). Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

Cornford, I. (2002). Learning to learn strategies as a basis for effective lifelong learning. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 21 , 357–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370210141020 .

De Backer, L., Van Keer, H., & Valcke, M. (2012). Exploring the potential impact of reciprocal peer tutoring on higher education students’ metacognitive knowledge and regulation. Instructional Science, 45 , 559–588. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-011-9190-5 .

DiFrancesca, D., Nietfeld, J., & Cao, L. (2016). A comparison of high and low achieving students on self-regulated learning variables. Learning and Individual Differences, 45 , 228–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.11.010 .

Efklides, A. (2011). Interactions of metacognition with motivation and affect in self-regulated learning: The MASRL model. Educational Psychologist, 46 (1), 6–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2011.538645 .

Field, S., Parker, D., Sawilowsy, S., & Rolands, L. (2013). Assessing the impact of ADHD coaching services on university students’ learning skills, self-regulation, and well-being. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 26 (1), 67–81. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1026813.pdf .

Follmer, J. & Sperling, R. (2016). The mediating role of metacognition in the relationship between executive function and self-regulated learning. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 86 (4), 559–575. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12123 .

Franklin, J. & Doran, J. (2009) Does all coaching enhance objective performance independently evaluated by blind assessors? The importance of the coaching model and content. International Coaching Psychology Review, 4 (2), 128–144.

Grant, A. (2013). The efficacy of coaching. In J. Passmore, D. Peterson, & T. Freire (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of the psychology of coaching and mentoring (pp. 15–39). Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Greene, J. A. (2018). Self-regulation in education . Taylor & Francis.

Gynnild, V., Holstada, A., & Myrhaug, D. (2008). Identifying and promoting self-regulated learning in higher education: Roles and responsibilities of student tutors. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 16 (2), 147–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611260801916317 .

Hartman, H., & Sternberg, J. (1993). A broad BACIES for improving thinking. Instructional Science, 21 , 401–425.

Hattie, J., Biggs, J., & Purdie, N. (1996). Effects of learning skills interventions on student learning: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 66 , 99–136. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543066002099 .

Howlett, M. A., McWilliams, M. A., Rademacher, K., Maitland, T. L., O’Neill, J. C., Abels, K., Demetriou, C. & Panter, A. T. (2020) An Academic Coaching Training Program for University Professionals: A Mixed Methods Examination. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice . https://doi.org/10.1080/19496591.2020.1784750 .

Hurme, T. L., Palonen, T., & Järvelä, S. (2006). Metacognition in joint discussions: An analysis of the patterns of interaction and the metacognitive content of the networked discussions in mathematics. Metacognition and Learning, 1 , 181–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-006-9792-5 .

Hutson, B. (2006). Monitoring for success: Implementing a proactive probation program for diverse, at-risk college students (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/305282691 .

Kallay, E. (2012). Learning strategies and metacognitive awareness as predictors of academic achievement in a sample of Romanian second-year students. Cognition, Brain, Behavior. An Interdisciplinary Journal, 16 (3), 369–385.

Kimsey-House, H., Kimsey-House, K., Sandahl, P., & Whitworth, L. (2018). Co-active Coaching, Fourth edition . Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Kitsantas, A., Winsler, A., & Hue, F. (2008). Self-regulation and ability predictors of academic success during college: A predictive validity study. Journal of Advanced Academics 20 (1), 42–68. https://doi.org/10.4219/jaa-2008-867 .

Kuhn, D. (2000). Metacognitive development. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9 (5), 178–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00088 .

Losch, S., Traut-Mattausch, E., Mühlberger, M., & Jonas, E. (2016). Comparing the effectiveness of individual coaching, self-coaching, and group training: How leadership makes the difference. Frontiers in Psychology, 7 , 629. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00629 .

Maclellan, E., & Soden, R. (2006). Facilitating self-regulation in higher education through self-report. Learning Environments Research, 9 , 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-005-9002-4 .

McGuire, S. Y. & McGuire, S. (2015). Teach students how to learn: Strategies you can incorporate into any course to improve student metacognition, study skills, and motivation . Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Meijer, J., Veenman, M. V. J., & van Hout-Wolters, B. H. A. M. (2006). Metacognitive activities in text studying and problem-solving: Development of a taxonomy. Educational Research and Evaluation, 12 , 209–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803610500479991 .

Moos, D. C., & Azevedo, R. (2009). Self-efficacy and prior domain knowledge: To what extent does monitoring mediate their relationship with hypermedia learning? Metacognition and Learning, 4 , 197–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-009-9045-5 .

Muis, K. (2007). The role of epistemic beliefs in self-regulated learning. Educational Psychologist, 42 (3), 173–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520701416306 .

Pintrich, P. (2000). The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning. In M. Boekaerts, P. Pintrich & M. Zeidnder (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 451–502). Academic Press.

Pintrich, P. (2004). A conceptual framework for assessing motivation and self-regulated learning in college students. Educational Psychology Review, 16 (4), 385–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-004-0006-x .

Prevatt, F. & Yelland, S. (2015). An empirical evaluation of ADHD coaching in college students. Journal of Attention Disorders, 19 (8), 666-677. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054713480036 .

Reeves, T. D. (2009). Toward a treatment effect of an intervention to foster self-regulated learning (SRL): An application of the Rasch Model (Doctoral Dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations Publishing (1469123).

Reeves, T. D., & Stich, A. E. (2011). Tackling suboptimal bachelor’s degree completion rates through training in self-regulated learning (SRL). Innovative Higher Education, 36 , 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-010-9152-x .

Richardson, M., Abraham, C., & Bond, R. (2012). Psychological correlates of university students’ academic performance: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138 (2), 353–387.

Richman, E., Rademacher, K., & Maitland, T. (2014). Coaching and college success. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 27 (1), 33–52. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1029647.pdf .

Robinson, C. E. (2015). Academic/success coaching: A description of an emerging field in higher education (Doctoral dissertation). University of South Carolina Scholar Commons. Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3148 .

Rosenshine, B., Meister, C., & Chapman, S. (1996). Teaching students to generate questions: A review of the intervention studies. Review of Educational Research, 66 , 181–221. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543066002181 .

Schraw, G., & Dennison, R. S. (1994). Assessing metacognitive awareness. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 19 , 460–475. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1994.1033 .

Schunk, D. H. & Greene, J. A. (2018). Historical, contemporary, and future perspectives on self-regulated learning and performance. In D.H. Schunk & J.A. Greene (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance (pp. 1–15). Taylor & Francis.

Schunk, D. H. & Mullen, C. A. (2013). Toward a conceptual model of mentoring research: Integration with self-regulated learning. Educational Psychology Review, 25 , 361–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-013-9233-3 .

Seli, H., & Dembo, M. H. (2016). Motivation and learning strategies for college success: A focus on self-regulated learning (5th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Seligman, M. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being . Free Press.

Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference . Houghton Mifflin.

Sitzmann, T. & Ely, K. (2011). A meta-analysis of self-regulated learning in work-related training and educational attainment: What we know and where we need to go. Psychological Bulletin, 137 (3), 421–442. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022777 .

Spence, G., & Grant, A. (2007). Professional and peer life coaching and the enhancement of goal striving and well-being: An exploratory study. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 2 (3), 185–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760701228896 .

Sperling, R., Howard, B., Staley, R., & DuBois, N. (2004). Metacognition and self-regulated learning constructs. Educational Research and Evaluation, 10 (2), 117–139. https://doi.org/10.1076/edre.10.2.117.27905 .

Theeboom, T., Beersma, B., & van Vianen, A. (2014). Does coaching work? A meta-analysis on the effects of coaching on individual level outcomes in an organizational context. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 9 (1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2013.837499 .

Vrieling, E., Stijnen, S., & Bastiaens, T. (2018). Successful learning: Balancing self-regulation with instructional planning. Teaching in Higher Education, 23 , 685–700, https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2017.1414784 .

Warner, Z., Neater, W., Clark, L., & Lee, J. (2018). Peer coaching and motivational interviewing in postsecondary settings: Connecting retention theory with practice. Journal of College Reading and Learning, 48 (3), 159–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790195.2018.1472940 .

Whitmore, J. (1992). Coaching for performance: A practical guide for growing your own skills . Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Willingham, D. T. (2009). Why don’t students like school? San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Winne, P. (1995). Self-regulation is ubiquitous but its forms vary with knowledge. Educational Psychologist, 30 (4), 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3004_9 .

Winne, P. (2011). A cognitive and metacognitive analysis of self-regulated learning. In B. Zimmerman & B. Schunk (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance (pp. 15–32). New York, NY: Routledge

Winne, P. & Perry, N. (2005). Measuring self-regulated learning. In M. Boekaerts, P. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 531–566). Academic Press.

Wolters, C. & Hussain, M. (2015). Investigating grit and its relation with college students’ self-regulated learning and academic achievement. Metacognition and Learning, 10 , 293–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-014-9128-9 .

Wolters, C. A., Won, S., & Hussain, M. (2017). Examining the relations of time management and procrastination within a model of self-regulated learning. Metacognition and Learning, 12 , 381–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-017-9174-1 .

Young, A. & Fry, J. (2008). Metacognitive awareness and academic achievement in college students. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 8 (2), 1–10. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ854832 .

Zimmerman, B. (2008). Investigating self-regulation and motivation: Historical background, methodological developments, and future prospects. American Educational Research Journal, 45 , 166–183. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831207312909 .

Zimmerman, B. (2013). From cognitive modeling to self-regulation: A social cognitive career path. Educational Psychologist, 48 (3), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2013.794676 .

Zimmerman, B. J., & Schunk, D. H. (Eds.) (2011). Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance . Routledge.

Download references

This research is part of the Finish Line Project (P116F140018; Panter, PI; Demetriou, Executive Director), which is funded by the U.S. Department of Education’s “First in the World” grant program.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Writing and Learning Center, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Campus Box 5135, 450 Ridge Rd, Chapel Hill, NC, 27599-5135, USA

Marc Alan Howlett, Melissa A. McWilliams, Kristen Rademacher, Theresa Laurie Maitland & Kimberly Abels

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University School of Medicine, 2608 Erwin Rd., Suite 300, Durham, NC, 27705, USA

J. Conor O’Neill

Student Success & Retention Innovation, University of Arizona, 1428 E. University Blvd., Tuscon, AZ, 85721, USA

Cynthia Demetriou

Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 235 E. Cameron Avenue, Chapel Hill, NC, 27599-3270, USA

A. T. Panter

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Corresponding author.

Correspondence to Marc Alan Howlett .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Code Availability

Additional information, publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions