Advanced search

Saved to my library.

University Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Peer Review: An Introduction: Where to Find Peer Reviewed Sources

- Why not just use Google or Wikipedia?

- Where to Find Peer Reviewed Sources

- Where to Get More Help

Need More Help?

Have more questions? Contact Scholarly Communication and Publishing at [email protected] for more information and guidance.

Ask a Librarian

The Ask a Librarian service for general reference is available during all of the hours when the Main Library is open. Visit the Ask a Librarian page to chat with a librarian.

Why is it so hard to find Peer-Reviewed Sources?

It isn't hard to find peer-reviewed sources: you just need to know where to look! If you start in the right place, you can usually find a relevant, peer-reviewed source for your research in as few clicks as a Google search, and you can even use many of the search techniques you use in Google and Wikipedia.

The easiest way to find a peer-reviewed article is by using one of the Library's numerous databases. All of the Library's databases are listed in the Online Journals and Databases index. The databases are divided by name and discipline.

Departmental libraries and library subject guides have created subject-focused lists of electronic and print research resources that are useful for their disciplines. You can search the library directory for links to the departmental libraries at the University of Illinois Library, or search library websites by college if you're not sure which departmental library serves your subject.

Peer-Reviewed Resources for Disciplinary Topics

There are numerous print and digital resources for specific disciplines, areas of study, and specialist fields. To find research resources and databases for your area, consult the comprehensive directory of LibGuides , the websites of specialist libraries, and above all, contact a librarian for help !

Here are a few major databases for finding peer-reviewed research sources in the humanities, social sciences, and sciences:

- MLA International Bibliography This link opens in a new window Indexes critical materials on literature, languages, linguistics, and folklore. Proved access to citations from worldwide publications, including periodicals, books, essay collections, working papers, proceedings, dissertations and bibliographies. more... less... Alternate Access Link

- Web of Science (Core Collection) This link opens in a new window Web of Science indexes core journal articles, conference proceedings, data sets, and other resources in the sciences, social sciences, arts, and humanities.

- Academic Search Ultimate This link opens in a new window A scholarly, multidisciplinary database providing indexing and abstracts for over 10,000 publications, including monographs, reports, conference proceedings, and others. Also includes full-text access to over 5,000 journals. Offers coverage of many areas of academic study including: archaeology, area studies, astronomy, biology, chemistry, civil engineering, electrical engineering, ethnic & multicultural studies, food science & technology, general science, geography, geology, law, mathematics, mechanical engineering, music, physics, psychology, religion & theology, women's studies, and other fields. more... less... Alternate Access Link

- IEEE Xplore This link opens in a new window Provides full-text access to IEEE transactions, IEEE and IEE journals, magazines, and conference proceedings published since 1988, and all current IEEE standards; brings additional search and access features to IEEE/IEE digital library users. Browsable by books & e-books, conference publications, education and learning, journals and magazines, standards and by topic. Also provides links to IEEE standards, IEEE spectrum and other sites.

- Scopus This link opens in a new window Scopus is the largest abstract and citation database including peer-reviewed titles from international publishers, Open Access journals, conference proceedings, trade publications and quality web sources. Subject coverage includes: Chemistry, Physics, Mathematics and Engineering; Life and Health Sciences; Social Sciences, Psychology and Economics; Biological, Agricultural and Environmental Sciences.

- Business Source Ultimate This link opens in a new window Provides bibliographic and full text content, including indexing and abstracts for scholarly business journals back as far as 1886 and full text journal articles in all disciplines of business, including marketing, management, MIS, POM, accounting, finance and economics. The database full text content includes financial data, books, monographs, major reference works, book digests, conference proceedings, case studies, investment research reports, industry reports, market research reports, country reports, company profiles, SWOT analyses and more. more... less... Alternate Access Link

- << Previous: Why not just use Google or Wikipedia?

- Next: Where to Get More Help >>

- Last Updated: Nov 9, 2023 11:15 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.illinois.edu/peerreview

Where to find peer reviewed articles for research

This is our ultimate guide to helping you get familiar with your research field and find peer reviewed articles in the Web of Science™. It forms part of our Research Smarter series.

Finding relevant research and journal articles in your field is critical to a successful research project. Unfortunately, it can be one of the hardest, most time-consuming challenges for academics.

This blog outlines how you can leverage the Web of Science citation network to complete an in-depth, comprehensive search for literature. We share insights about how you can find a research paper and quickly assess its impact. We also explain how to create alerts to keep track of new papers in your field – whether you’re new to the topic or about to embark on a literature review.

- Choosing research databases for your search

- Where to find peer reviewed articles? Master the keyword search

- Filter your results and analyze for trends

- Explore the citation network

- Save your searches and set up alerts for new journal articles

1. Choosing research databases for your search

The myriad search engines, research databases and data repositories all differ in reliability, relevancy and organization of data. This can make it tricky to navigate and assess what’s best for your research at hand.

The Web of Science stands out the most powerful and trusted citation database. It helps you connect ideas and advance scientific research across all fields and disciplines. This is made possible with best-in-class publication and citation data for confident discovery and assessment of journal articles. The Web of Science is also publisher-neutral, carefully-curated by a team of expert editors and consists of 19 different research databases.

The Web of Science Core Collection™ is the single most authoritative source for how to find research articles, discover top authors , and relevant journals . It only includes journals that have met rigorous quality and impact criteria, and it captures billions of cited references from globally significant journals, books and proceedings ( check out its coverage ). Researchers and organizations use this research database regularly to track ideas across disciplines and time.

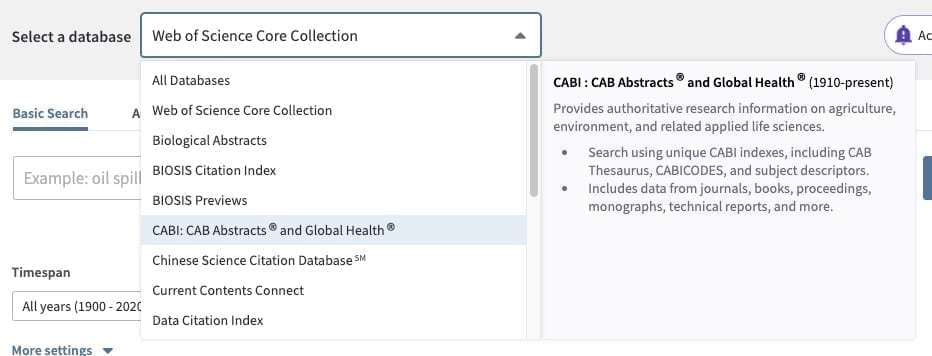

Explore the Web of Science Core Collection

We recommend spending time exploring the Core Collection specifically because its advanced citation network features are unparalleled. If you are looking to do an exhaustive search of a specific field, you might want to switch to one of the field-specific databases like MEDLINE and INSPEC. You can also select “All databases” from the drop-down box on the main search page. This will cover all research databases your institution subscribes to. IF you are still unsure about where to find scholarly journal articles, you can learn more in our Quick Reference Guide, here, or try it out today.

“We recommend spending time exploring the Core Collection specifically because its advanced citation network features are unparalleled.”

2. Where to find peer reviewed articles? Master the keyword search

A great deal of care and consideration is needed to find peer review articles for research. It starts with your keyword search.

Your chosen keywords or search phrases cannot be too inclusive or limiting. They also require constant iteration as you become more familiar with your research field. Watch this video on search tips to learn more:

It’s worth noting that a repeated keyword search in the same Web of Science database will retrieve almost identical results every time, save for newly-indexed research. Not all research databases do this. If you are conducting a literature review and require a reproducible keyword search, it is best to steer clear of certain databases. For example, a research database that lacks overall transparency or frequently changes its search algorithm may be detrimental to your research.

3. Filter your search results and analyze trends

Group, rank and analyze the research articles in your search results to optimize the relevancy and efficiency of your efforts. In the Web of Science, researchers can cut through the data in a number of creative ways. This will help you when you’re stuck wondering where to find peer reviewed articles, journals and authors. The filter and refine tools , as well as the Analyze Results feature, are all at your disposal for this.

“Group, rank and analyze the research papers in your search results to optimize the relevancy and efficiency of your efforts.”

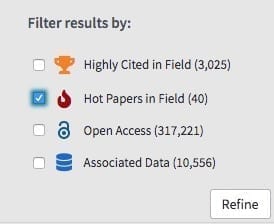

Filter and Refine tools in the Web of Science

You can opt for basic filter and refine tools in the Web of Science. These include subject category, publication date and open access within your search results. You can also filter by highly-cited research and hot research papers. A hot paper is a journal article that has accumulated rapid and significant numbers of citations over a short period of time.

The Analyze Results tool does much of this and more. It provides an interactive visualization of your results by the most prolific author, institution and funding agency, for example. This, combined, will help you understand trends across your field.

4. Explore the citation network

Keyword searches are essentially an a priori view of the literature. Citation-based searching, on the other hand, leads to “systematic serendipity”. This term was used by Eugene Garfield, the founder of Web of Science. New scientific developments are linked to the global sphere of human knowledge through the citation network. The constantly evolving connections link ideas and lead to systematic serendipity, allowing for all sorts of surprising discoveries.

Exploring the citation network helps you to:

- Identify a seminal research paper in any field. Pay attention to the number of times a journal article is cited to achieve this.

- Track the advancement of research as it progresses over time by analyzing the research papers that cite the original source. This will also help you catch retractions and corrections to research.

- Track the evolution of a research paper backward in time by tracking the work that a particular journal article cites.

- View related references. A research paper may share citations with another piece of work (calculated from bibliographic coupling). That means it’s likely discussing a similar topic.

Visualizing the history discoveries in the citation network

The Web of Science Core Collection indexes every piece of content cover-to-cover. This creates a complete and certain view of more than 115 years of the highest-quality journal articles. The depth of coverage enables you to uncover the historical trail of a research paper in your field. By doing so, it helps you visualize how discoveries unfold through time. You can also learn where they might branch off into new areas of research. Achieve this in your search by ordering your result set by date of publication.

As PhD student Rachel Ragnhild Carlson (Stanford University) recently wrote in a column for Nature: [1]

”As a PhD student, I’ve learnt to rely not just on my Web of Science research but on numerous conversations with seasoned experts. And I make sure that my reading includes literature from previous decades, which often doesn’t rise to the top of a web search. This practice is reinforced by mentors in my lab, who often find research gems by filtering explicitly for studies greater than ten years old.”

5. Save your search and set up alerts for new journal articles

Save time and keep abreast of new journal articles in your field by saving your searches and setting up email alerts . This means you can return to your search at any time. You can also stay up-to-date about a new research paper included in your search result. This will help you find an article more easily in the future. Head over to Web of Science to try it out today.

“Everyone should set up email alerts with keywords for PubMed, Web of Science, etc. Those keyword lists will evolve and be fine-tuned over time. However, it really helps to get an idea of recent publications.” Thorbjörn Sievert , PhD student, University of Jyväskylä

[1] Ragnhild Carlson, R. 2020 ‘How Trump’s embattled environment agency prepared me for a PhD’, Nature 579, 458

Related posts

Reimagining research impact: introducing web of science research intelligence.

Beyond discovery: AI and the future of the Web of Science

Clarivate welcomes the Barcelona Declaration on Open Research Information

Finding Scholarly Articles: Home

What's a Scholarly Article?

Your professor has specified that you are to use scholarly (or primary research or peer-reviewed or refereed or academic) articles only in your paper. What does that mean?

Scholarly or primary research articles are peer-reviewed , which means that they have gone through the process of being read by reviewers or referees before being accepted for publication. When a scholar submits an article to a scholarly journal, the manuscript is sent to experts in that field to read and decide if the research is valid and the article should be published. Typically the reviewers indicate to the journal editors whether they think the article should be accepted, sent back for revisions, or rejected.

To decide whether an article is a primary research article, look for the following:

- The author’s (or authors') credentials and academic affiliation(s) should be given;

- There should be an abstract summarizing the research;

- The methods and materials used should be given, often in a separate section;

- There are citations within the text or footnotes referencing sources used;

- Results of the research are given;

- There should be discussion and conclusion ;

- With a bibliography or list of references at the end.

Caution: even though a journal may be peer-reviewed, not all the items in it will be. For instance, there might be editorials, book reviews, news reports, etc. Check for the parts of the article to be sure.

You can limit your search results to primary research, peer-reviewed or refereed articles in many databases. To search for scholarly articles in HOLLIS , type your keywords in the box at the top, and select Catalog&Articles from the choices that appear next. On the search results screen, look for the Show Only section on the right and click on Peer-reviewed articles . (Make sure to login in with your HarvardKey to get full-text of the articles that Harvard has purchased.)

Many of the databases that Harvard offers have similar features to limit to peer-reviewed or scholarly articles. For example in Academic Search Premier , click on the box for Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) Journals on the search screen.

Review articles are another great way to find scholarly primary research articles. Review articles are not considered "primary research", but they pull together primary research articles on a topic, summarize and analyze them. In Google Scholar , click on Review Articles at the left of the search results screen. Ask your professor whether review articles can be cited for an assignment.

A note about Google searching. A regular Google search turns up a broad variety of results, which can include scholarly articles but Google results also contain commercial and popular sources which may be misleading, outdated, etc. Use Google Scholar through the Harvard Library instead.

About Wikipedia . W ikipedia is not considered scholarly, and should not be cited, but it frequently includes references to scholarly articles. Before using those references for an assignment, double check by finding them in Hollis or a more specific subject database .

Still not sure about a source? Consult the course syllabus for guidance, contact your professor or teaching fellow, or use the Ask A Librarian service.

- Last Updated: Oct 3, 2023 3:37 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/FindingScholarlyArticles

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

Explore millions of high-quality primary sources and images from around the world, including artworks, maps, photographs, and more.

Explore migration issues through a variety of media types

- Part of The Streets are Talking: Public Forms of Creative Expression from Around the World

- Part of The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Winter 2020)

- Part of Cato Institute (Aug. 3, 2021)

- Part of University of California Press

- Part of Open: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Part of Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, Vol. 19, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

- Part of R Street Institute (Nov. 1, 2020)

- Part of Leuven University Press

- Part of UN Secretary-General Papers: Ban Ki-moon (2007-2016)

- Part of Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol. 12, No. 4 (August 2018)

- Part of Leveraging Lives: Serbia and Illegal Tunisian Migration to Europe, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (Mar. 1, 2023)

- Part of UCL Press

Harness the power of visual materials—explore more than 3 million images now on JSTOR.

Enhance your scholarly research with underground newspapers, magazines, and journals.

Explore collections in the arts, sciences, and literature from the world’s leading museums, archives, and scholars.

Navigation group

Home banner.

Where scientists empower society

Creating solutions for healthy lives on a healthy planet.

most-cited publisher

largest publisher

2.5 billion

article views and downloads

Main Content

- Editors and reviewers

- Collaborators

Find a journal

We have a home for your research. Our community led journals cover more than 1,500 academic disciplines and are some of the largest and most cited in their fields.

Submit your research

Start your submission and get more impact for your research by publishing with us.

Author guidelines

Ready to publish? Check our author guidelines for everything you need to know about submitting, from choosing a journal and section to preparing your manuscript.

Peer review

Our efficient collaborative peer review means you’ll get a decision on your manuscript in an average of 61 days.

Article publishing charges (APCs) apply to articles that are accepted for publication by our external and independent editorial boards

Press office

Visit our press office for key media contact information, as well as Frontiers’ media kit, including our embargo policy, logos, key facts, leadership bios, and imagery.

Institutional partnerships

Join more than 555 institutions around the world already benefiting from an institutional membership with Frontiers, including CERN, Max Planck Society, and the University of Oxford.

Publishing partnerships

Partner with Frontiers and make your society’s transition to open access a reality with our custom-built platform and publishing expertise.

Policy Labs

Connecting experts from business, science, and policy to strengthen the dialogue between scientific research and informed policymaking.

How we publish

All Frontiers journals are community-run and fully open access, so every research article we publish is immediately and permanently free to read.

Editor guidelines

Reviewing a manuscript? See our guidelines for everything you need to know about our peer review process.

Become an editor

Apply to join an editorial board and collaborate with an international team of carefully selected independent researchers.

My assignments

It’s easy to find and track your editorial assignments with our platform, 'My Frontiers' – saving you time to spend on your own research.

Experts call for global genetic warning system to combat the next pandemic and antimicrobial resistance

Scientists champion global genomic surveillance using latest technologies and a “One Health” approach to protect against novel pathogens like avian influenza and antimicrobial resistance, catching epidemics before they start.

Safeguarding peer review to ensure quality at scale

Making scientific research open has never been more important. But for research to be trusted, it must be of the highest quality. Facing an industry-wide rise in fraudulent science, Frontiers has increased its focus on safeguarding quality.

Scientists call for urgent action to prevent immune-mediated illnesses caused by climate change and biodiversity loss

Climate change, pollution, and collapsing biodiversity are damaging our immune systems, but improving the environment offers effective and fast-acting protection.

Baby sharks prefer being closer to shore, show scientists

marine scientists have shown for the first time that juvenile great white sharks select warm and shallow waters to aggregate within one kilometer from the shore.

Puzzling link between depression and cardiovascular disease explained at last

It’s long been known that depression and cardiovascular disease are somehow related, though exactly how remained a puzzle. Now, researchers have identified a ‘gene module’ which is part of the developmental program of both diseases.

Air pollution could increase the risk of neurological disorders: Here are five Frontiers articles you won’t want to miss this Earth Day

At Frontiers, we bring some of the world’s best research to a global audience. But with tens of thousands of articles published each year, it’s impossible to cover all of them. Here are just five amazing papers you may have missed.

Opening health for all: 7 Research Topics shaping a healthier world

We have picked 7 Research Topics that tackle some of the world's toughest healthcare challenges. These topics champion everyone's access to healthcare, life-limiting illness as a public health challenge, and the ethical challenges in digital public health.

Get the latest research updates, subscribe to our newsletter

Articles & Media

Books & eBooks

Tips for Finding Peer Reviewed Articles

What is a peer reviewed article, example of a peer reviewed article, gale academic onefile.

Because of this more rigorous process, a peer reviewed article is considered to have the most value, even more than other scholarly articles.

Extracted from Alexander Hamilton and the Sedition Act: A Founder's Ambivalence on Freedom of the Press . (Must be on campus or have a COM account to view the entire article).

Get peer reviewed articles in Gale Academic OneFile. Here's how:

- Perform a search on your topic.

- Under Filter Your Results , select Peer-Reviewed Journals .

- All your results will now be peer reviewed.

All the articles in JSTOR are not only scholarly, but peer reviewed so you can search as you normally would. JSTOR does include content other than articles, such as primary sources, images reports and open content in the results, however, that are not peer reviewed. To take these out your results:

- Under Refine Results , find Academic Content

- Select Journals

- You should be left with peer reviewed content.

Get peer reviewed articles in ProQuest. Here's how:

- Select the Peer Reviewed option directly under the search box, or in the Narrow results column.

- Last Updated: May 13, 2024 4:39 PM

- URL: https://libguides.com.edu/peer

© 2023 COM Library 1200 Amburn Road, Texas City, Texas 77591 409-933-8448 . FAX 409-933-8030 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License Class Poll

Finding Peer-Reviewed Articles: Google Scholar

- Introduction

- Using Databases

- Searching for Specific Journals

- Google Scholar

- Inter-Library Loan

Google Scholar Search

Advanced Scholar Search Tips

About Google Scholar

Google Scholar provides a simple way to broadly search for scholarly literature. You can search across many disciplines and sources for: articles, theses, books, abstracts and court opinions, from academic publishers, professional societies, online repositories, universities and other web sites.

Features of Google Scholar:

- Search diverse sources from one convenient place

- Find articles, theses, books, abstracts or court opinions

- Locate the complete document through your library or on the web

- Learn about key scholarly literature in any area of research

With Google Scholar, you can search by scholar preferences, easily navigate to related articles, and see how many times an article has been cited. Use search criteria to locate peer-reviewed articles.

Search with Google Scholar

- << Previous: Searching for Specific Journals

- Next: Inter-Library Loan >>

- Last Updated: Sep 14, 2022 4:20 PM

- URL: https://palmbeachstate.libguides.com/peerreview

- USU Library

Articles: Finding (and Identifying) Peer-Reviewed Articles: What is Peer Review?

- What is Peer Review?

- Finding Peer Reviewed Articles

- Databases That Can Determine Peer Review

Peer Review in 3 Minutes

What is "Peer-Review"?

What are they.

Scholarly articles are papers that describe a research study.

Why are scholarly articles useful?

They report original research projects that have been reviewed by other experts before they are accepted for publication, so you can reasonably be assured that they contain valid information.

How do you identify scholarly or peer-reviewed articles?

- They are usually fairly lengthy - most likely at least 7-10 pages

- The authors and their credentials should be identified, at least the company or university where the author is employed

- There is usually a list of References or Works Cited at the end of the paper, listing the sources that the authors used in their research

How do you find them?

Some of the library's databases contain scholarly articles, either exclusively or in combination with other types of articles.

Google Scholar is another option for searching for scholarly articles.

Know the Difference Between Scholarly and Popular Journals/Magazines

Peer reviewed articles are found in scholarly journals. The checklist below can help you determine if what you are looking at is peer reviewed or scholarly.

- Both kinds of journals and magazines can be useful sources of information.

- Popular magazines and newspapers are good for overviews, recent news, first-person accounts, and opinions about a topic.

- Scholarly journals, often called scientific or peer-reviewed journals, are good sources of actual studies or research conducted about a particular topic. They go through a process of review by experts, so the information is usually highly reliable.

- Next: Finding Peer Reviewed Articles >>

- Last Updated: Feb 28, 2023 10:46 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usu.edu/peer-review

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

- Collections

- Services & Support

Which Source Should I Use?

- The Right Source For Your Need-Authority

- Finding Subject Specific Sources: Research Guides

- Understanding Peer Reviewed Articles

- Understanding Peer Reviewed Articles- Arts & Humanities

- How to Read a Journal Article

- Locating Journals

- How to Find Streaming Media

The Peer Review Process

So you need to use scholarly, peer-reviewed articles for an assignment...what does that mean?

Peer review is a process for evaluating research studies before they are published by an academic journal. These studies typically communicate original research or analysis for other researchers.

The Peer Review Process at a Glance:

Looking for peer-reviewed articles? Try searching in OneSearch or a library database and look for options to limit your results to scholarly/peer-reviewed or academic journals. Check out this brief tutorial to show you how: How to Locate a Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) Article

Part 1: Watch the Video

Part 1: watch the video all about peer review (3 min.) and reflect on discussion questions..

Discussion Questions

After watching the video, reflect on the following questions:

- According to the video, what are some of the pros and cons of the peer review process?

- Why is the peer review process important to scholarship?

- Do you think peer reviewers should be paid for their work? Why or why not?

Part 2: Practice

Part 2: take an interactive tutorial on reading a research article for your major..

Includes a certification of completion to download and upload to Canvas.

Social Sciences

(e.g. Psychology, Sociology)

(e.g. Health Science, Biology)

Arts & Humanities

(e.g. Visual & Media Arts, Cultural Studies, Literature, History)

Click on the handout to view in a new tab, download, or print.

For Instructors

- Teaching Peer Review for Instructors

In class or for homework, watch the video “All About Peer Review” (3 min.) .

Video discussion questions:

- According to the video, what are some of the pros and cons of the peer review process

Assignment Ideas

- Ask students to conduct their own peer review of an important journal article in your field. Ask them to reflect on the process. What was hard to critique?

- Have students examine a journals’ web page with information for authors. What information is given to the author about the peer review process for this journal?

- Assign this reading by CSUDH faculty member Terry McGlynn, "Should journals pay for manuscript reviews?" What is the author's argument? Who profits the most from published research? You could also hold a debate with one side for paying reviewers and the other side against.

- Search a database like Cabell’s for information on the journal submission process for a particular title or subject. How long does peer review take for a particular title? Is it is a blind review? How many reviewers are solicited? What is their acceptance rate?

- Assign short readings that address peer review models. We recommend this issue of Nature on peer review debate and open review and this Chronicle of Higher Education article on open review in Shakespeare Quarterly .

Proof of Completion

Mix and match this suite of instructional materials for your course needs!

Questions about integrating a graded online component into your class, contact the Online Learning Librarian, Rebecca Nowicki ( [email protected] ).

Example of a certificate of completion:

- << Previous: Finding Subject Specific Sources: Research Guides

- Next: Understanding Peer Reviewed Articles- Arts & Humanities >>

- Last Updated: Apr 26, 2024 10:45 AM

- URL: https://libguides.sdsu.edu/WhichSource

- University of Texas Libraries

- UT Libraries

Finding Journal Articles 101

Peer-reviewed or refereed.

- Research Article

- Review Article

- By Journal Title

What Does "Peer-reviewed" or "Refereed" Mean?

Peer review is a process that journals use to ensure the articles they publish represent the best scholarship currently available. When an article is submitted to a peer reviewed journal, the editors send it out to other scholars in the same field (the author's peers) to get their opinion on the quality of the scholarship, its relevance to the field, its appropriateness for the journal, etc.

Publications that don't use peer review (Time, Cosmo, Salon) just rely on the judgment of the editors whether an article is up to snuff or not. That's why you can't count on them for solid, scientific scholarship.

Note:This is an entirely different concept from " Review Articles ."

How do I know if a journal publishes peer-reviewed articles?

Usually, you can tell just by looking. A scholarly journal is visibly different from other magazines, but occasionally it can be hard to tell, or you just want to be extra-certain. In that case, you turn to Ulrich's Periodical Directory Online . Just type the journal's title into the text box, hit "submit," and you'll get back a report that will tell you (among other things) whether the journal contains articles that are peer reviewed, or, as Ulrich's calls it, Refereed.

Remember, even journals that use peer review may have some content that does not undergo peer review. The ultimate determination must be made on an article-by-article basis.

For example, the journal Science publishes a mix of peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed content. Here are two articles from the same issue of Science .

This one is not peer-reviewed: https://science-sciencemag-org.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/content/303/5655/154.1 This one is a peer-reviewed research article: https://science-sciencemag-org.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/content/303/5655/226

That is consistent with the Ulrichsweb description of Science , which states, "Provides news of recent international developments and research in all fields of science. Publishes original research results, reviews and short features."

Test these periodicals in Ulrichs :

- Advances in Dental Research

- Clinical Anatomy

- Molecular Cancer Research

- Journal of Clinical Electrophysiology

- Last Updated: Aug 28, 2023 9:25 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/journalarticles101

Peer-reviewed journal articles

- Overview of peer review

- Scholarly and academic - good enough?

- Find peer-reviewed articles

Using Library Search

Is a journal peer reviewed, check the journal.

Resources listed in Library Search that are peer reviewed will include the Peer Reviewed icon.

For example:

If you have not used Library Search to find the article, which may indicate if it's peer reviewed, you can use Ulrichsweb to check.

- Go to Ulrichsweb

Screenshot of search box in UlrichsWeb © Proquest

- Enter the journal title in the search box.

Screenshot of results list in UlrichsWeb © Proquest

- If there are no results, do a search in Ulrichsweb to find journals in your field that are peer reviewed.

Be aware that not all articles in peer reviewed journals are refereed or peer reviewed, for example, editorials and book reviews.

If the journal is not listed in Ulrichsweb :

- Go to the journal's website

- Check for information on a peer review process for the journal. Try the Author guidelines , Instructions for authors or About this journal sections.

If you can find no evidence that a journal is peer reviewed, but you are required to have a refereed article, you may need to choose a different article.

- << Previous: Find peer-reviewed articles

- Last Updated: Dec 6, 2023 2:42 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.uq.edu.au/how-to-find/peer-reviewed-articles

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to know if an article is peer reviewed [6 key features]

Features of a peer reviewed article

How to find peer reviewed articles, frequently asked questions about peer reviewed articles, related articles.

A peer reviewed article refers to a work that has been thoroughly assessed, and based on its quality, has been accepted for publication in a scholarly journal. The aim of peer reviewing is to publish articles that meet the standards established in each field. This way, peer reviewed articles that are published can be taken as models of research practices.

A peer reviewed article can be recognized by the following features:

- It is published in a scholarly journal.

- It has a serious, and academic tone.

- It features an abstract at the beginning.

- It is divided by headings into introduction, literature review or background, discussion, and conclusion.

- It includes in-text citations, and a bibliography listing accurately all references.

- Its authors are affiliated with a research institute or university.

There are many ways in which you can find peer reviewed articles, for instance:

- Check the journal's features and 'About' section. This part should state if the articles published in the journal are peer reviewed, and the type of reviewing they perform.

- Consult a database with peer reviewed journals, such as Web of Science Master Journal List , PubMed , Scopus , Google Scholar , etc. Specify in the advanced search settings that you are looking for peer reviewed journals only.

- Consult your library's database, and specify in the search settings that you are looking for peer reviewed journals only.

➡️ Want to know if a source is scholarly? Check out our guide on scholarly sources.

➡️ Want to know if a source is credible? Find out in our guide on credible sources (+ how to find them).

A peer reviewed article refers to a work that has been thoroughly assessed, and based on its quality has been accepted to be published in a scholarly journal.

Once an article has been submitted for publication to a peer reviewed journal, the journal assigns the article to an expert in the field, who is considered the “peer”.

The easiest way to find a peer reviewed article is to narrow down the search in the "Advanced search" option. Then, mark the box that says "peer reviewed".

Consult a database with peer reviewed journals, such as Web of Science Master Journal List , PubMed , Scopus , etc.

There are many views on peer reviewed articles. Take a look at Peer Review in Scientific Publications: Benefits, Critiques, & A Survival Guide for more insight on this topic.

Finding scholarly, peer reviewed articles

Learn how to search for only scholarly and peer-reviewed journal articles.

Scholarly articles are written by researchers and intended for an audience of other researchers. Scholarly writers may assume that the reader already has some understanding of the topic and its vocabulary. Peer-reviewed articles are evaluated by other scholars or experts within the same field as the author before they are published, to help ensure the validity of the research being done. Learn more about the peer review process .

Many scholarly articles are peer-reviewed and vice versa, but this may not always be the case. In addition, an article can be from a peer-reviewed journal and not actually be peer reviewed. Components such as editorials, news items, and book reviews do not go through the same review process.

Many professors will require that you use only scholarly, peer-reviewed journal articles in your research papers and assignments. To simplify the research process, you can limit your search to only see peer-reviewed articles in Library Search and many library databases.

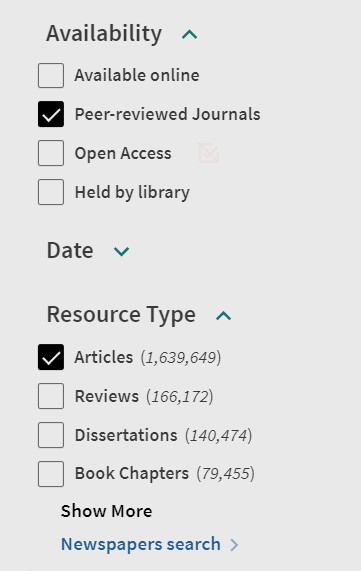

Limiting to peer-reviewed articles in Library Search

In Library Search, you can refine your results to peer-reviewed articles by selecting two filters. Under “Availability,” choose “Peer-reviewed Journals.” Under “Resource Type,” choose “Articles.” If you plan to do multiple searches, be sure to click the lock icon that says “Remember all filters” underneath “Active Filters” at the top. This will ensure your results continue to show only peer-reviewed articles even if you try different keywords. Peer-reviewed articles will display a purple icon of a book with an eye over it under their title and citation information.

Filter options in Library Search. The "Peer-reviewed Journals" and "Articles" options have filled checkboxes next to their names, which indicates these options have been selected.

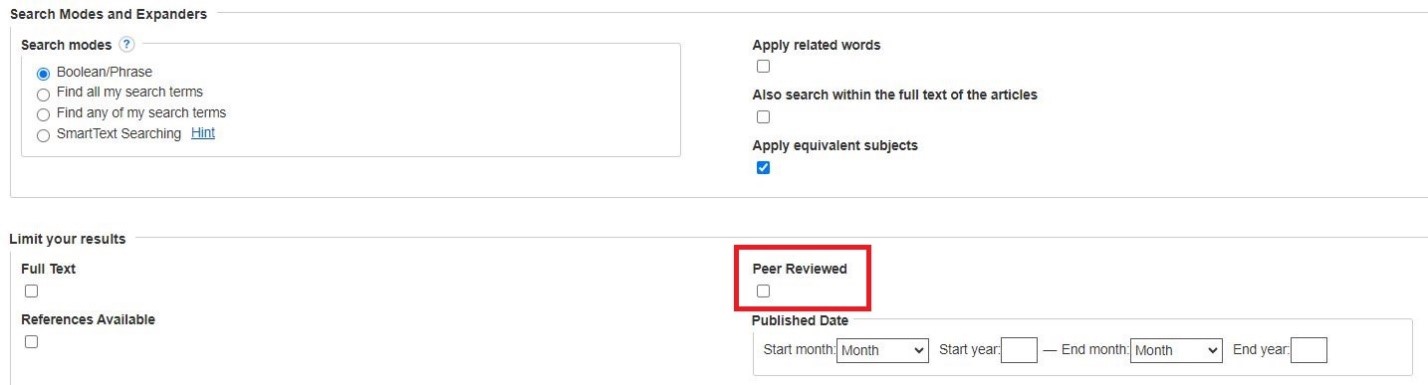

Limiting to peer-reviewed articles in databases

Many databases have an option to limit your search results to peer-reviewed articles. This will usually appear either in advanced search options or in a bank of filters in the search results screen.

Search options for a database hosted in EBSCO. Under the subheading “Limit your results,” a checkbox with the words “Peer Reviewed” above it is enclosed in a red square to indicate its position on the screen.

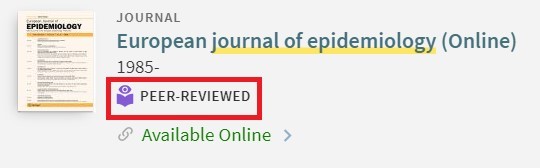

Checking the status of your article

If you need further confirmation of whether an article comes from a peer-reviewed journal, you can follow one of the procedures below.

Search for a journal title in the library’s Journals search list. Titles that are peer reviewed will have a small purple icon of an eye above an open book with the words “Peer-Reviewed” next to it.

A small purple icon of an eye above an open book, and the words "Peer-Reviewed" are enclosed in a red rectangle.

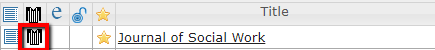

If you don’t find a journal in the Journals’ list as described above, you can consult the UlrichsWeb database . It includes information on journals that are not owned by the University, so you might want to check a journal title there before you make an Interlibrary Loan request. When you search for a journal title in this database, you will see a small black and white referee icon. This indicates that the journal is peer reviewed. You can also check the journal publisher's website. It should indicate whether articles go through a peer-review process on a page that contains instructions for authors.

In this entry for the "Journal of Social Work," there is a small black and white "referee" icon, which indicates that the journal is peer reviewed. The "referee" icon is enclosed in a red square.

Library & Learning Commons

- Search for sources

- APA style guide

How to Find Scholarly, Peer-Reviewed Journal Articles

- Peer Review & Academic/Scholarly Journals

- How to Identify a Scholarly, Peer-Reviewed Journal Article

- Finding Academic/Scholarly Journal Articles in Library Databases

#wrapbox6165059. headerbox { display: none; }

Confused by scholarly, peer-reviewed sources?

This guide explains the peer review process, the identifying characteristics of a peer-reviewed article, and where you'll find scholarly, peer-reviewed journal articles in the RGO Library & Learning Commons databases.

#wrapbox6161783. headerbox { display: none; }

- What is Peer Review?

- What is an Academic/Scholarly Journal?

- What is a Peer-Reviewed Article?

Also called an academic or peer-reviewed journal, a scholarly journal:

• Is a type of periodical (a publication issued in regular periods, i.e. newspapers, magazines, etc.) that provides a forum for scholarly communication in a particular academic discipline,

• Publishes original, peer-reviewed research-based or theoretical articles are written by researchers and experts,

• Publishes additional forms of scholarly communication such as book reviews, editorials, conference proceedings, debate pieces, and interviews.

A scholarly, peer-reviewed journal article:

• Presents research studies and experiments or original theoretical analysis that advances what is understood or known in a specific subject area or discipline,

• Is written by the person(s) who conducted the research or analysis, who typically have advanced degrees, credentials, and/or academic positions,

• Often has a scientific format with sections and headings that follow the structure of a research study:

In addition to the scientific format described in the previous tab, there are several common types of scholarly, peer-reviewed journal articles.

Follow the links below to view examples of a systematic literature review , a case study , a theoretical research article, and a scientific research article from the library databases:

- Neighborhood safety factors associated with older adults' health-related outcomes: A systematic literature review. (2016) This is a sub-type of a LITERATURE REVIEW article that systematically and critically collects, describes and summarizes prior publications on a specific topic or subject, rather than reporting new original research. It features a substantial list of references that a reader may wish to consult when learning about or researching a topic.

- Chronic Schizophrenia and Cognitive Behaviour Therapy: Three Case Studies. (2015) Common in the social sciences and life sciences, a CASE STUDY provides an intensive analysis of an individual unit (such as a person, group, community or event) in order to illustrates a problem, present new variables, and provide possible solutions or questions for further research.

- Early childhood cognitive development and parental cognitive stimulation: Evidence for reciprocal gene-environment transactions (2012) This scientific RESEARCH STUDY presents original interpretation of data that was collected and analyzed by the authors. It uses technical and formal language with a logical structure that reflects the format of the study.

- The unifying function of affect: Founding a theory of psychocultural development in the epistemology of John Dewey and Carl Jung (2012) This example of a THEORETICAL RESEARCH article that presents an original argument or conclusion based on the interpretation of evidence. This type of article usually refers to or contains new or established abstract principles related to a very specific field of knowledge.

#wrapbox6166979. headerbox { display: none; }

- Next: How to Identify a Scholarly, Peer-Reviewed Journal Article >>

- Last Updated: Jan 25, 2024 10:44 AM

- URL: https://bowvalleycollege.libguides.com/scholarly-articles

7 Ways to Find Peer-Reviewed Articles on Google Scholar

Google Scholar is the professional place to find scholarly literature, peer-reviewed articles and high-quality, patented and unpatented research on a specialized Google platform.

Google search is everything in 2021; one can search anything on the internet by Google search which provides nearly 99% accurate results. One can find products, literature, articles, information or any data from Google simply by telling “Hell Google” from your Phone.

Say “Hello Google please suggest to me the best recipes for poached egg”

And that’s it!

It will give you tons of results.

But let me tell you that finding high-quality, peer-reviewed articles on Google isn’t that easy. The reason is that the Google search is meant for all people. Meaning, when searching anything directly from Google search, it will provide broad search results to cover all topics, products and results for all age groups.

For example,

When you search “Symptoms of H1N1 flu”; The results might show

- Some common symptoms

- Questions relevant to the topics

- Products related to the H1N1 flu- medication, therapies and testing

- Some good blog articles

- Global News on H1N1

- And like that…

If you are a researcher, PhD scholar or scientist, these search results may not help you, I guess. You need more powerful, research-based, peer-reviewed and more scientific results.

And for that my friends you have to go to Google Scholar. I know it isn’t that much hard to use Google Scholar but still, many research students still don’t know how to use it.

I have conducted a small research study and asked my research students how they start searching the literature. 87% of them said,

They go the Google, search their queries like

- H1N1 Wikipedia

- H1N1 articles PMC

- H1N1 article PubMed

- H1N1 article NCBI

Like that, but mostly they avoid the very first segment suggested by Google itself, that’s our Google scholar,

When you click on it, you will get tons of high-quality research articles. Note that Google standard search and Google Scholar search have some substantial differences, take a look at the table,

Difference Between Google Search and Google Scholar search:

There are several ways you can use this tool to find peer-reviewed articles, journal reviews and thesis. In this article, I will explain 7 ways to find peer-reviewed articles on Google Scholar.

Search on Google:

Directly go to google scholar: , write a topic name with +google scholar: , search peer-reviewed articles: , short by relevance: , search by author or authors name:, search from the google scholar profile: .

- Wrapping up:

7 Ways to find Peer-Reviewed articles on Google Scholar:

One of the easiest ways to find scholarly articles is by searching anything directly using Google search.

Go to Google Search using this link > https://www.google.com/ .

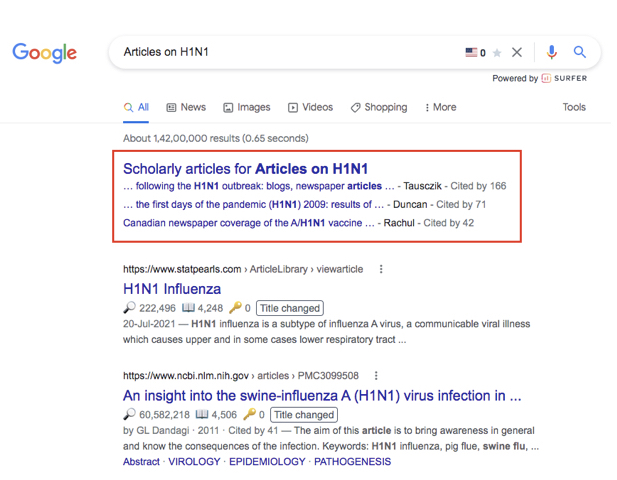

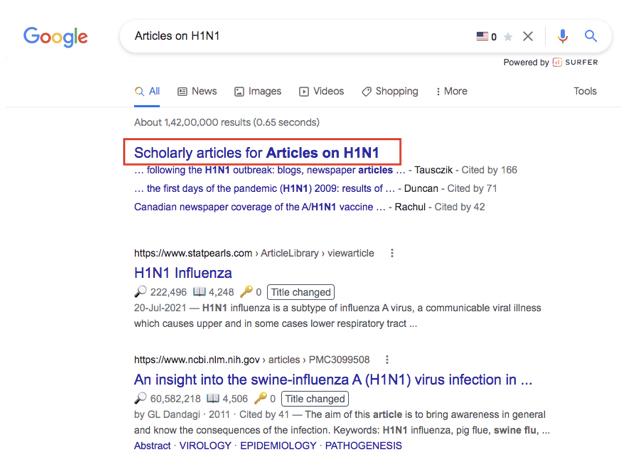

Search in the search box, for example, “Articles on H1N1”.

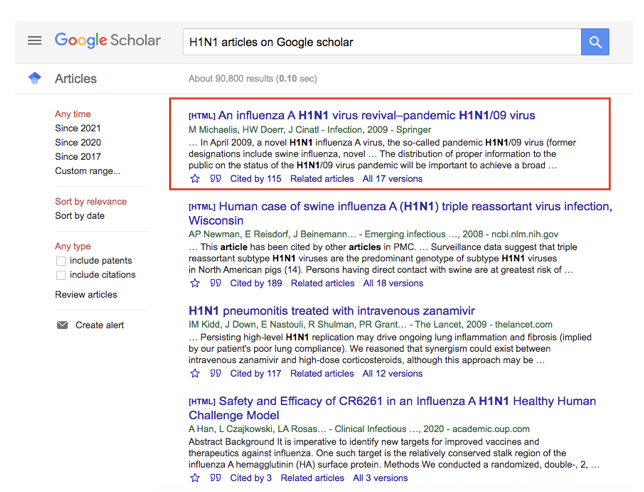

You will get various results, see the very first results (Image below)

Click on the “Scholarly articles for Articles on H1N1”

Now you will get so many articles that are well-cited, peer-reviewed and in-depth.

Newbies usually don’t go directly to Google scholar, instead prefer to use Wiki or other resources. If you just have started your PhD and don’t know where to initiate, start reading articles only on Google Scholar.

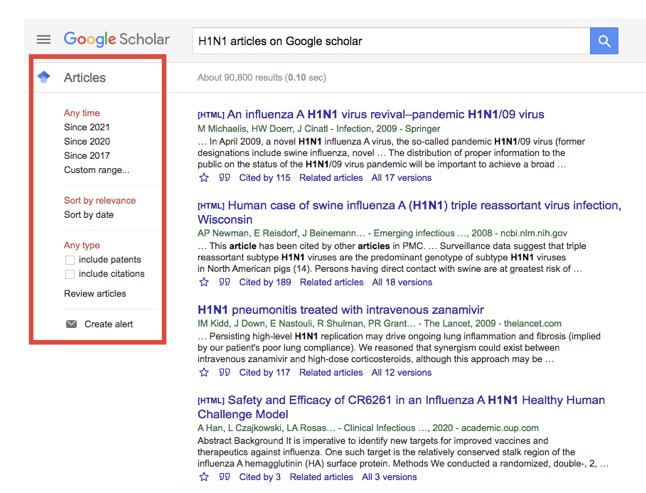

Go to the URL: https://scholar.google.com/

In the search box search only “H1N1”

You will get various resources on H1N1 that help in your study. You will also get other relevant studies and articles, contact details, scientists, organizations or labs working in your research area, etc.

In addition, you will get ideas for additional research queries relevant to your research.

The easiest way to use the Google scholar database is to customize your research query.

Go to Google >> https://www.google.com/ .

Search “H1N1 articles on Google scholar”

You will get a Google scholar list of articles as well as only high-quality articles related to the topic you searched.

Yet another easiest way to find the most outstanding peer-reviewed journal articles is by a consuming search query.

Go to Google >> https://www.google.com/ .

Write Peer-reviewed articles on H1N1

You will get the same list of scholarly articles on the present topic.

Getting more relevant resources is yet another difficult task to complete. It’s practically not possible to go through all articles present in the Google Scholar library.

One needs more precise, customized, appropriate and relevant results.

Google Scholar provides a “Short By relevance” feature to find articles only what you want.

For example, for H1N1 you will get tons of resources, some are useful and some are not!

Suppose you need review articles.

Go to the sidebar and click on review articles.

Suppose you need only articles published since 2020.

On the sidebar, you can choose a year or from which year you want research articles.

There are other options as well which you can use as per your requirement.

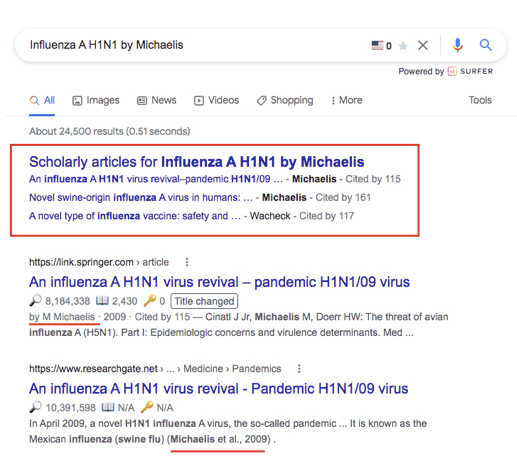

Yet another interesting way to search scholarly research work is by searching articles by the name of the author; if his/her profile is there on Google scholar, it immediately shows you.

Take look at the example,

Influenza A H1N1 by Michaelis, you will get results like this,

This is exactly the same results on Google Scholar, take a look,

Note that this will be fine only if you know some of the renowned researchers and scientists working in your field.

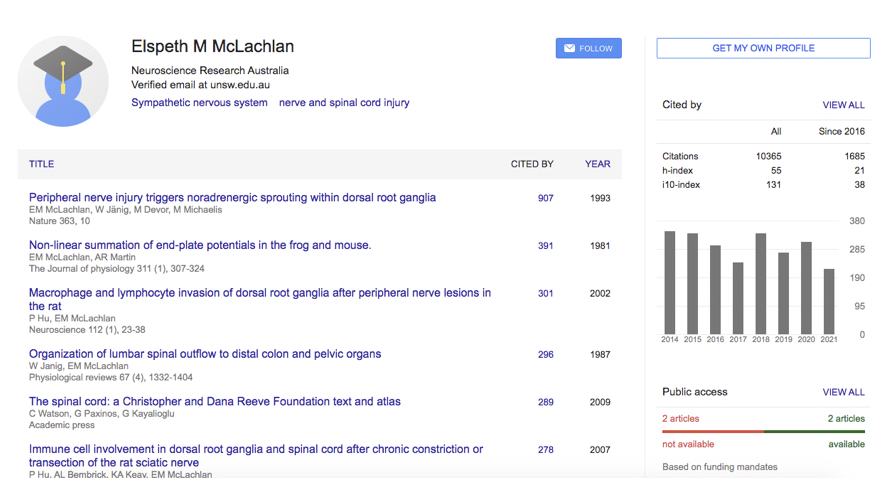

If you already have a Google Scholar account and some scholarly articles, you can search relevant resources from the profile of other researchers as well.

For example,

Take a look at the profile of Elspeth M McLachlan.

You can find all the publications and his collaboration on the Google Scholar profile.

Read more: How to Generate a Bibliography using Citation Generator .

Wrapping up:

Google Scholar is a significantly important sub-search engine for researchers, scientists and PhD students. If you have a Google Scholar profile, some Peer-reviewed articles, trust me you will get more citations, reads and rewards in your academic and research field.

Use scholars and try to publish some good quality work as well.

I hope this article will help you.

Dr. Tushar Chauhan is a Scientist, Blogger and Scientific-writer. He has completed PhD in Genetics. Dr. Chauhan is a PhD coach and tutor.

Share this:

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Pinterest

- Share on Linkedin

- Share via Email

About The Author

Dr Tushar Chauhan

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Reumatologia

- v.59(1); 2021

Peer review guidance: a primer for researchers

Olena zimba.

1 Department of Internal Medicine No. 2, Danylo Halytsky Lviv National Medical University, Lviv, Ukraine

Armen Yuri Gasparyan

2 Departments of Rheumatology and Research and Development, Dudley Group NHS Foundation Trust (Teaching Trust of the University of Birmingham, UK), Russells Hall Hospital, Dudley, West Midlands, UK

The peer review process is essential for quality checks and validation of journal submissions. Although it has some limitations, including manipulations and biased and unfair evaluations, there is no other alternative to the system. Several peer review models are now practised, with public review being the most appropriate in view of the open science movement. Constructive reviewer comments are increasingly recognised as scholarly contributions which should meet certain ethics and reporting standards. The Publons platform, which is now part of the Web of Science Group (Clarivate Analytics), credits validated reviewer accomplishments and serves as an instrument for selecting and promoting the best reviewers. All authors with relevant profiles may act as reviewers. Adherence to research reporting standards and access to bibliographic databases are recommended to help reviewers draft evidence-based and detailed comments.

Introduction

The peer review process is essential for evaluating the quality of scholarly works, suggesting corrections, and learning from other authors’ mistakes. The principles of peer review are largely based on professionalism, eloquence, and collegiate attitude. As such, reviewing journal submissions is a privilege and responsibility for ‘elite’ research fellows who contribute to their professional societies and add value by voluntarily sharing their knowledge and experience.

Since the launch of the first academic periodicals back in 1665, the peer review has been mandatory for validating scientific facts, selecting influential works, and minimizing chances of publishing erroneous research reports [ 1 ]. Over the past centuries, peer review models have evolved from single-handed editorial evaluations to collegial discussions, with numerous strengths and inevitable limitations of each practised model [ 2 , 3 ]. With multiplication of periodicals and editorial management platforms, the reviewer pool has expanded and internationalized. Various sets of rules have been proposed to select skilled reviewers and employ globally acceptable tools and language styles [ 4 , 5 ].

In the era of digitization, the ethical dimension of the peer review has emerged, necessitating involvement of peers with full understanding of research and publication ethics to exclude unethical articles from the pool of evidence-based research and reviews [ 6 ]. In the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, some, if not most, journals face the unavailability of skilled reviewers, resulting in an unprecedented increase of articles without a history of peer review or those with surprisingly short evaluation timelines [ 7 ].

Editorial recommendations and the best reviewers

Guidance on peer review and selection of reviewers is currently available in the recommendations of global editorial associations which can be consulted by journal editors for updating their ethics statements and by research managers for crediting the evaluators. The International Committee on Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) qualifies peer review as a continuation of the scientific process that should involve experts who are able to timely respond to reviewer invitations, submitting unbiased and constructive comments, and keeping confidentiality [ 8 ].

The reviewer roles and responsibilities are listed in the updated recommendations of the Council of Science Editors (CSE) [ 9 ] where ethical conduct is viewed as a premise of the quality evaluations. The Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) further emphasizes editorial strategies that ensure transparent and unbiased reviewer evaluations by trained professionals [ 10 ]. Finally, the World Association of Medical Editors (WAME) prioritizes selecting the best reviewers with validated profiles to avoid substandard or fraudulent reviewer comments [ 11 ]. Accordingly, the Sarajevo Declaration on Integrity and Visibility of Scholarly Publications encourages reviewers to register with the Open Researcher and Contributor ID (ORCID) platform to validate and publicize their scholarly activities [ 12 ].

Although the best reviewer criteria are not listed in the editorial recommendations, it is apparent that the manuscript evaluators should be active researchers with extensive experience in the subject matter and an impressive list of relevant and recent publications [ 13 ]. All authors embarking on an academic career and publishing articles with active contact details can be involved in the evaluation of others’ scholarly works [ 14 ]. Ideally, the reviewers should be peers of the manuscript authors with equal scholarly ranks and credentials.

However, journal editors may employ schemes that engage junior research fellows as co-reviewers along with their mentors and senior fellows [ 15 ]. Such a scheme is successfully practised within the framework of the Emerging EULAR (European League Against Rheumatism) Network (EMEUNET) where seasoned authors (mentors) train ongoing researchers (mentees) how to evaluate submissions to the top rheumatology journals and select the best evaluators for regular contributors to these journals [ 16 ].

The awareness of the EQUATOR Network reporting standards may help the reviewers to evaluate methodology and suggest related revisions. Statistical skills help the reviewers to detect basic mistakes and suggest additional analyses. For example, scanning data presentation and revealing mistakes in the presentation of means and standard deviations often prompt re-analyses of distributions and replacement of parametric tests with non-parametric ones [ 17 , 18 ].

Constructive reviewer comments

The main goal of the peer review is to support authors in their attempt to publish ethically sound and professionally validated works that may attract readers’ attention and positively influence healthcare research and practice. As such, an optimal reviewer comment has to comprehensively examine all parts of the research and review work ( Table I ). The best reviewers are viewed as contributors who guide authors on how to correct mistakes, discuss study limitations, and highlight its strengths [ 19 ].

Structure of a reviewer comment to be forwarded to authors

Some of the currently practised review models are well positioned to help authors reveal and correct their mistakes at pre- or post-publication stages ( Table II ). The global move toward open science is particularly instrumental for increasing the quality and transparency of reviewer contributions.

Advantages and disadvantages of common manuscript evaluation models

Since there are no universally acceptable criteria for selecting reviewers and structuring their comments, instructions of all peer-reviewed journal should specify priorities, models, and expected review outcomes [ 20 ]. Monitoring and reporting average peer review timelines is also required to encourage timely evaluations and avoid delays. Depending on journal policies and article types, the first round of peer review may last from a few days to a few weeks. The fast-track review (up to 3 days) is practised by some top journals which process clinical trial reports and other priority items.

In exceptional cases, reviewer contributions may result in substantive changes, appreciated by authors in the official acknowledgments. In most cases, however, reviewers should avoid engaging in the authors’ research and writing. They should refrain from instructing the authors on additional tests and data collection as these may delay publication of original submissions with conclusive results.

Established publishers often employ advanced editorial management systems that support reviewers by providing instantaneous access to the review instructions, online structured forms, and some bibliographic databases. Such support enables drafting of evidence-based comments that examine the novelty, ethical soundness, and implications of the reviewed manuscripts [ 21 ].

Encouraging reviewers to submit their recommendations on manuscript acceptance/rejection and related editorial tasks is now a common practice. Skilled reviewers may prompt the editors to reject or transfer manuscripts which fall outside the journal scope, perform additional ethics checks, and minimize chances of publishing erroneous and unethical articles. They may also raise concerns over the editorial strategies in their comments to the editors.

Since reviewer and editor roles are distinct, reviewer recommendations are aimed at helping editors, but not at replacing their decision-making functions. The final decisions rest with handling editors. Handling editors weigh not only reviewer comments, but also priorities related to article types and geographic origins, space limitations in certain periods, and envisaged influence in terms of social media attention and citations. This is why rejections of even flawless manuscripts are likely at early rounds of internal and external evaluations across most peer-reviewed journals.

Reviewers are often requested to comment on language correctness and overall readability of the evaluated manuscripts. Given the wide availability of in-house and external editing services, reviewer comments on language mistakes and typos are categorized as minor. At the same time, non-Anglophone experts’ poor language skills often exclude them from contributing to the peer review in most influential journals [ 22 ]. Comments should be properly edited to convey messages in positive or neutral tones, express ideas of varying degrees of certainty, and present logical order of words, sentences, and paragraphs [ 23 , 24 ]. Consulting linguists on communication culture, passing advanced language courses, and honing commenting skills may increase the overall quality and appeal of the reviewer accomplishments [ 5 , 25 ].

Peer reviewer credits

Various crediting mechanisms have been proposed to motivate reviewers and maintain the integrity of science communication [ 26 ]. Annual reviewer acknowledgments are widely practised for naming manuscript evaluators and appreciating their scholarly contributions. Given the need to weigh reviewer contributions, some journal editors distinguish ‘elite’ reviewers with numerous evaluations and award those with timely and outstanding accomplishments [ 27 ]. Such targeted recognition ensures ethical soundness of the peer review and facilitates promotion of the best candidates for grant funding and academic job appointments [ 28 ].

Also, large publishers and learned societies issue certificates of excellence in reviewing which may include Continuing Professional Development (CPD) points [ 29 ]. Finally, an entirely new crediting mechanism is proposed to award bonus points to active reviewers who may collect, transfer, and use these points to discount gold open-access charges within the publisher consortia [ 30 ].

With the launch of Publons ( http://publons.com/ ) and its integration with Web of Science Group (Clarivate Analytics), reviewer recognition has become a matter of scientific prestige. Reviewers can now freely open their Publons accounts and record their contributions to online journals with Digital Object Identifiers (DOI). Journal editors, in turn, may generate official reviewer acknowledgments and encourage reviewers to forward them to Publons for building up individual reviewer and journal profiles. All published articles maintain e-links to their review records and post-publication promotion on social media, allowing the reviewers to continuously track expert evaluations and comments. A paid-up partnership is also available to journals and publishers for automatically transferring peer-review records to Publons upon mutually acceptable arrangements.

Listing reviewer accomplishments on an individual Publons profile showcases scholarly contributions of the account holder. The reviewer accomplishments placed next to the account holders’ own articles and editorial accomplishments point to the diversity of scholarly contributions. Researchers may establish links between their Publons and ORCID accounts to further benefit from complementary services of both platforms. Publons Academy ( https://publons.com/community/academy/ ) additionally offers an online training course to novice researchers who may improve their reviewing skills under the guidance of experienced mentors and journal editors. Finally, journal editors may conduct searches through the Publons platform to select the best reviewers across academic disciplines.

Peer review ethics

Prior to accepting reviewer invitations, scholars need to weigh a number of factors which may compromise their evaluations. First of all, they are required to accept the reviewer invitations if they are capable of timely submitting their comments. Peer review timelines depend on article type and vary widely across journals. The rules of transparent publishing necessitate recording manuscript submission and acceptance dates in article footnotes to inform readers of the evaluation speed and to help investigators in the event of multiple unethical submissions. Timely reviewer accomplishments often enable fast publication of valuable works with positive implications for healthcare. Unjustifiably long peer review, on the contrary, delays dissemination of influential reports and results in ethical misconduct, such as plagiarism of a manuscript under evaluation [ 31 ].

In the times of proliferation of open-access journals relying on article processing charges, unjustifiably short review may point to the absence of quality evaluation and apparently ‘predatory’ publishing practice [ 32 , 33 ]. Authors when choosing their target journals should take into account the peer review strategy and associated timelines to avoid substandard periodicals.

Reviewer primary interests (unbiased evaluation of manuscripts) may come into conflict with secondary interests (promotion of their own scholarly works), necessitating disclosures by filling in related parts in the online reviewer window or uploading the ICMJE conflict of interest forms. Biomedical reviewers, who are directly or indirectly supported by the pharmaceutical industry, may encounter conflicts while evaluating drug research. Such instances require explicit disclosures of conflicts and/or rejections of reviewer invitations.

Journal editors are obliged to employ mechanisms for disclosing reviewer financial and non-financial conflicts of interest to avoid processing of biased comments [ 34 ]. They should also cautiously process negative comments that oppose dissenting, but still valid, scientific ideas [ 35 ]. Reviewer conflicts that stem from academic activities in a competitive environment may introduce biases, resulting in unfair rejections of manuscripts with opposing concepts, results, and interpretations. The same academic conflicts may lead to coercive reviewer self-citations, forcing authors to incorporate suggested reviewer references or face negative feedback and an unjustified rejection [ 36 ]. Notably, several publisher investigations have demonstrated a global scale of such misconduct, involving some highly cited researchers and top scientific journals [ 37 ].

Fake peer review, an extreme example of conflict of interest, is another form of misconduct that has surfaced in the time of mass proliferation of gold open-access journals and publication of articles without quality checks [ 38 ]. Fake reviews are generated by manipulating authors and commercial editing agencies with full access to their own manuscripts and peer review evaluations in the journal editorial management systems. The sole aim of these reviews is to break the manuscript evaluation process and to pave the way for publication of pseudoscientific articles. Authors of these articles are often supported by funds intended for the growth of science in non-Anglophone countries [ 39 ]. Iranian and Chinese authors are often caught submitting fake reviews, resulting in mass retractions by large publishers [ 38 ]. Several suggestions have been made to overcome this issue, with assigning independent reviewers and requesting their ORCID IDs viewed as the most practical options [ 40 ].

Conclusions

The peer review process is regulated by publishers and editors, enforcing updated global editorial recommendations. Selecting the best reviewers and providing authors with constructive comments may improve the quality of published articles. Reviewers are selected in view of their professional backgrounds and skills in research reporting, statistics, ethics, and language. Quality reviewer comments attract superior submissions and add to the journal’s scientific prestige [ 41 ].

In the era of digitization and open science, various online tools and platforms are available to upgrade the peer review and credit experts for their scholarly contributions. With its links to the ORCID platform and social media channels, Publons now offers the optimal model for crediting and keeping track of the best and most active reviewers. Publons Academy additionally offers online training for novice researchers who may benefit from the experience of their mentoring editors. Overall, reviewer training in how to evaluate journal submissions and avoid related misconduct is an important process, which some indexed journals are experimenting with [ 42 ].

The timelines and rigour of the peer review may change during the current pandemic. However, journal editors should mobilize their resources to avoid publication of unchecked and misleading reports. Additional efforts are required to monitor published contents and encourage readers to post their comments on publishers’ online platforms (blogs) and other social media channels [ 43 , 44 ].

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

- Library databases

- Library website

Evaluating Resources: Peer Review

What is peer review.

The term peer review can be confusing, since in some of your courses you may be asked to review the work of your peers. When we talk about peer-reviewed journal articles, this has nothing to do with your peers!

Peer-reviewed journals, also called refereed journals, are journals that use a specific scholarly review process to try to ensure the accuracy and reliability of published articles. When an article is submitted to a peer-reviewed journal for publication, the journal sends the article to other scholars/experts in that field and has them review the article for accuracy and reliability.

Find out more about peer review with our Peer Review Guide:

- Peer Review Guide

Types of peer review

Single blind.

In this process, the names of the reviewers are not known to the author(s). The reviewers do know the name of the author(s).

Double blind

Here, neither reviewers or authors know each other's names.

In the open review process, both reviewers and authors know each other's names.

What about editorial review?

Journals also use an editorial review process. This is not the same as peer review. In an editorial review process an article is evaluated for style guidelines and for clarity. Reviewers here do not look at technical accuracy or errors in data or methodology, but instead look at grammar, style, and whether an article is well written.

What is the difference between scholarly and peer review?

Not all scholarly journals are peer reviewed, but all peer-reviewed journals are scholarly.

- Things that are written for a scholarly or academic audience are considered scholarly writing.

- Peer-reviewed journals are a part of the larger category of scholarly writing.

- Scholarly writing includes many resources that are not peer reviewed, such as books, textbooks, and dissertations.

Scholarly writing does not come with a label that says scholarly . You will need to evaluate the resource to see if it is

- aimed at a scholarly audience

- reporting research, theories or other types of information important to scholars

- documenting and citing sources used to help authenticate the research done

The standard peer review process only applies to journals. While scholarly writing has certainly been edited and reviewed, peer review is a specific process only used by peer-reviewed journals. Books and dissertations may be scholarly, but are not considered peer reviewed.

Check out Select the Right Source for help with what kinds of resources are appropriate for discussion posts, assignments, projects, and more:

- Select the Right Source

How do I locate or verify peer-reviewed articles?

The peer review process is initiated by the journal publisher before an article is even published. Nowhere in the article will it tell you whether or not the article has gone through a peer review process.

You can locate peer-reviewed articles in the Library databases, typically by checking a limiter box.

- Quick Answer: How do I find scholarly, peer reviewed journal articles?

You can verify whether a journal uses a peer review process by using Ulrich's Periodicals Directory.

- Quick Answer: How do I verify that my article is peer reviewed?

What about resources that are not peer-reviewed?

Limiting your search to peer review is a way that you can ensure that you're looking at scholarly journal articles, and not popular or trade publications. Because peer-reviewed articles have been vetted by experts in the field, they are viewed as being held to a higher standard, and therefore are considered to be a high quality source. Professors often prefer peer-reviewed articles because they are considered to be of higher quality.

There are times, though, when the information you need may not be available in a peer-reviewed article.

- You may need to find original work on a theory that was first published in a book.

- You may need to find very current statistical data that comes from a government website.

- You may need background information that comes from a scholarly encyclopedia.

You will want to evaluate these resources to make sure that they are the best source for the information you need.

Note: If you are required for an assignment to find information from a peer-reviewed journal, then you will not be able to use non-peer-reviewed sources such as books, dissertations, or government websites. It's always best to clarify any questions over assignments with your professor.

- Previous Page: Evaluation Methods

- Next Page: Primary & Secondary Sources

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

University Libraries

- Research Guides

- Blackboard Learn

- Interlibrary Loan

- Study Rooms

- University of Arkansas

Libraries Information for Families

Getting started with onesearch.

- Library Locations