- Sign into My Research

- Create My Research Account

- Company Website

- Our Products

- About Dissertations

- Español (España)

- Support Center

Select language

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Português (Brasil)

- Português (Portugal)

Welcome to My Research!

You may have access to the free features available through My Research. You can save searches, save documents, create alerts and more. Please log in through your library or institution to check if you have access.

Translate this article into 20 different languages!

If you log in through your library or institution you might have access to this article in multiple languages.

Get access to 20+ different citations styles

Styles include MLA, APA, Chicago and many more. This feature may be available for free if you log in through your library or institution.

Looking for a PDF of this document?

You may have access to it for free by logging in through your library or institution.

Want to save this document?

You may have access to different export options including Google Drive and Microsoft OneDrive and citation management tools like RefWorks and EasyBib. Try logging in through your library or institution to get access to these tools.

- Document 1 of 1

- More like this

- Scholarly Journal

Situational, Transformational, and Transactional Leadership and Leadership Development

No items selected.

Please select one or more items.

Select results items first to use the cite, email, save, and export options

In order to advance our knowledge of leadership, it is necessary to understand where the study of leadership has been. McCleskey (2014) argued that the study of leadership spans more than 100 years. This manuscript describes three seminal leadership theories and their development. Analysis of a sampling of recent articles in each theory is included. The manuscript also discusses the concept of leadership development in light of those three seminal theories and offers suggestions for moving forward both the academic study of leadership and the practical application of research findings on the field.

Keywords: Leadership, Situational Leadership, Transactional Leadership, Transformational Leadership, Development, Review

Introduction

This manuscript analyzes three seminal leadership theories: situational leadership, transformational leadership (TL), and transactional leadership. It begins with introductory comments about the academic field of leadership, continues with a look at the three theories including their history and development, and proceeds to a micro-level, examining several recent published studies in each area. It presents a comparison and contrast of the key principles of each. The manuscript also discusses modern leadership challenges and leadership development in the context of all three theories. First, a brief history of leadership follows.

Leadership Theory

One of the earliest studies of leadership, Galton's (1869) Hereditary Genius emphasized a basic concept that informed popular ideas about leadership (Zaccaro, 2007). The idea is that leadership is a characteristic ability of extraordinary individuals. This conception of leadership, known as the great man theory, evolved into the study of leadership traits, only to be supplanted later the theories under discussion here (Glynn & DeJordy, 2010). Before discussing leadership, it is useful to define the term. The question of the correct definition of leadership is a nontrivial matter. Rost (1993) discovered 221 different definitions and conceptions of leadership. Some of those definitions were narrow while others offered broader conceptions. Bass (2000; 2008) argued that the search for a single definition of leadership was pointless. Among multiple definitions and conceptions, the correct definition of leadership depends on the specific aspect of leadership of interest to the individual (Bass, 2008). This manuscript focuses on three specific conceptions of leadership: situational, transformational, and TL. The next section begins with situational leadership.

Situational leadership

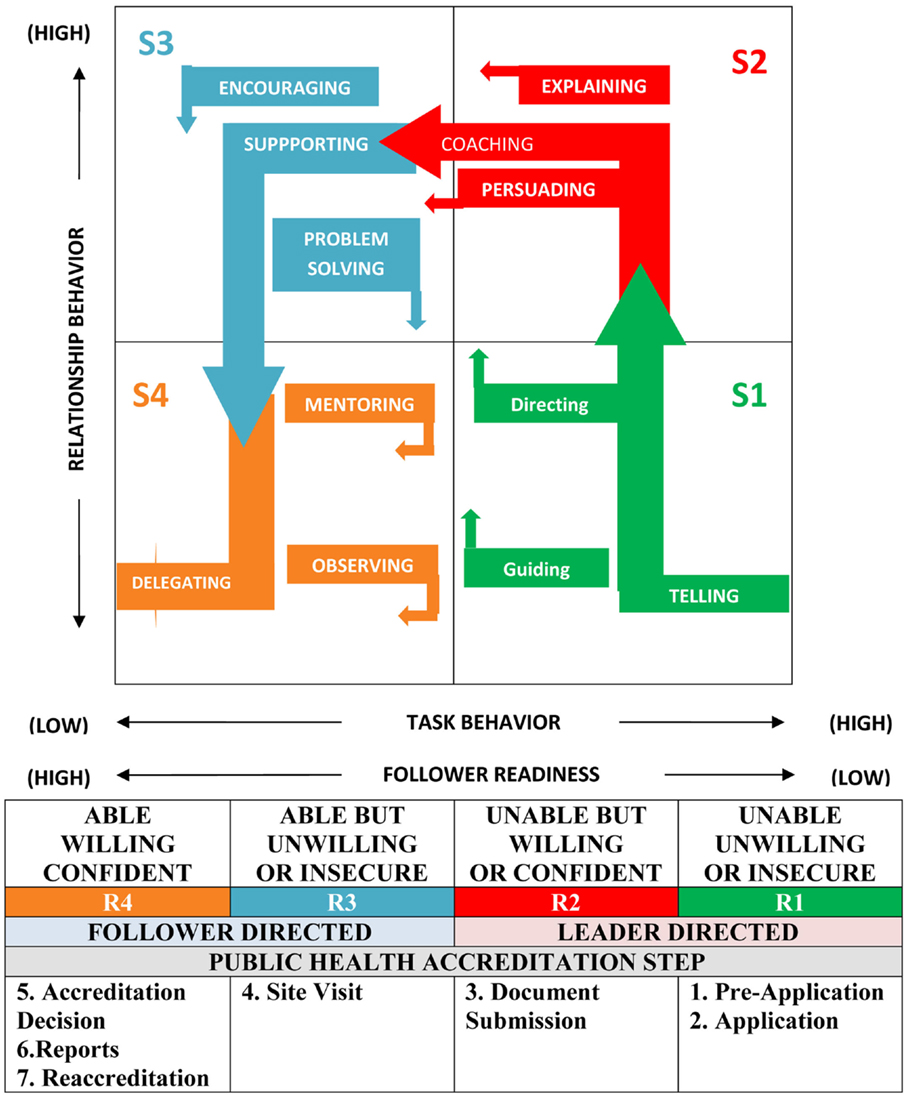

Situational leadership theory proposes that effective leadership requires a rational understanding of the situation and an appropriate response, rather than a charismatic leader with a large group of dedicated followers (Graeff, 1997; Grint, 2011). Situational leadership in general and Situational Leadership Theory (SLT) in particular evolved from a task-oriented versus people-oriented leadership continuum (Bass, 2008; Conger, 2010; Graeff, 1997; Lorsch, 2010). The continuum represented the extent that the leader focuses on the required tasks or focuses on their relations with their followers. Originally developed by Hershey and Blanchard (1969; 1979; 1996), SLT described leadership style, and stressed the need to relate the leader's style to the maturity level of the followers. Task-oriented leaders define the roles for followers, give definite instructions, create organizational patterns, and establish formal communication channels (Bass, 2008; Hersey & Blanchard, 1969; 1979; 1996; 1980; 1981). In contrast, relation-oriented leaders practice concern for others, attempt to reduce emotional conflicts, seek harmonious relations, and regulate equal participation (Bass, 2008; Hersey & Blanchard, 1969; 1979; 1996; 1980; 1981; Shin, Heath, & Lee, 2011). Various authors have classified SLT as a behavioral theory (Bass, 2008) or a contingency theory (Yukl, 2011). Both conceptions contain some validity. SLT focuses on leaders' behaviors as either task or people focused. This supports its inclusion as a behavioral approach to leadership, similar to the leadership styles approach (autocratic, democratic, and laissez-faire), the Michigan production-oriented versus employee- oriented approach, the Ohio State initiation versus consideration dichotomy, and the directive versus participative approach (Bass, 2008; Glynn & DeJordy, 2010). It also portrays effective leadership as contingent on follower maturity. This fits with other contingency-based leadership theories including Fiedler's contingency theory, path-goal theory, leadership substitutes theory, and Vroom's normative contingency model (Glynn & DeJordy, 2010; Bass, 2008; Yukl, 2011). Both conceptualizations of SLT admit that task-oriented and relation-oriented behaviors are dependent, rather than mutually exclusive approaches. The effective leader engages in a mix of task and relation behaviors (Cubero, 2007; Graeff, 1997; Shin et al., 2011; Yukl, 2008; 2011; Yukl & Mahsud, 2010). The level of maturity (both job and psychological maturity) of followers determines the correct leadership style and relates to previous education and training interventions (Bass, 2008; Hersey & Blanchard, 1969). Some scholars criticize SLT specifically and situational leadership in general.

Criticisms of situational leadership

SLT was a popular conception of leadership; however, as experience with the original Hersey & Blanchard model accrued, problems with the construct appeared. Nicholls (1985) described three flaws with SLT dealing with its consistency, continuity, and conformity. Bass (2008) agreed, noting lack of internal consistency, conceptual contradictions, and ambiguities. Other scholars suggested additional weaknesses of SLT (Bass, 2008; Glynn & DeJordy, 2010). Research revealed that no particular leadership style was universally effective and behavioral theories relied on abstract leadership types that were difficult to identify (Glynn & DeJordy, 2010). A number of recent studies utilized the situational leadership approach. Next, this manuscript describes two of them.

Research articles on situational leadership

Paul and Elder (2008) presented a guide for the analysis of research articles. Paul and Elder (2008) suggested that the examination of an article explicitly consider the purpose, question, information, concepts, assumptions, inferences, point of view, and implications in the study. Arvidsson, Johansson, Ek, and Akselsson (2007), used a situational leadership framework in the study of air traffic control employees. Arvidsson et al. (2007) set out to investigate how leadership styles and adaptability differ across various situations, conditions, structures, and tasks in the air traffic control arena. The authors asked a variety of research questions about the relationship between leadership adaptability, task-orientation of the leader, leadership style, working situation, operational conditions, organizational structure, and level of leadership experience (Arvidsson et al., 2007). The information contained in the article included a discussion of the literature linking leadership and safety and a relationship between leadership and reduced stress levels. The article described the SLT model, the study, methods, results, and discussion. The specific concepts presented included leadership and SLT. The authors' implicit assumptions included a relationship between effective leadership and workplace safety as well as a relationship between leadership effectiveness and stress and between stress and poor workplace performance. The authors also assumed that differences among coworkers require leaders to exhibit sensitivity to and the ability to diagnose varying levels of maturity or readiness among employees (Arvidsson et al, 2007). The point of view of the article is quantitative, positivist, and objectivist. The authors hypothesize a correlation between independent and dependent variables and then set out to investigate and confirm that relationship (Creswell, 2009). Arvidsson et al. (2007) discussed implications of their work. In particular, despite the fact that previous research indicated that relation-oriented leadership is preferred over task-oriented leadership, task- orientation is suitable in some situations. Assigning tasks and job roles, specifying procedures, and clarifying follower expectations result in increased job satisfaction (Arvidsson et al., 2007). The next section examines another recent study.

Larsson and Vinberg (2010) conducted a study to identify common leadership behaviors at a small group of successful companies and to organize those behaviors into suitable categories to discuss theoretical implications of situational aspects of effective leadership. The study attempted to uncover common leadership behaviors as they related to quality, effectiveness, environment, and health perceptions. The implicit questions included which leadership behaviors relate to outcomes, situational aspects, effectiveness, productivity, quality, and job satisfaction (Larsson & Vinberg, 2010). The information in the article covered situational leadership theories, theoretical constructs of effectiveness, and a description of four case studies of effective organizations. The study addressed the concepts of leadership effectiveness, task orientation, relation orientation, change leadership, and case study methodology. Larsson and Vinberg (2010) started from the position of endorsing the relationship between leadership and organizational success. Then they sought to identify the behaviors common to successful leadership across four subject organizations. Larsson and Vinberg conducted the study from a qualitative, comparative, positivist point of view (2010). The authors discuss the implications as well as the need for additional research. Larsson and Vinberg (2010) conclude that successful leadership includes both universally applicable elements (task-oriented) and contingency elements (relation and change-oriented). The authors suggest additional research in leadership and quality, and in leadership and follower health outcomes (Larsson & Vinberg, 2010). The next section presents the transformational leadership theory.

Transformational leadership (TL)

Over the past 30 years, TL has been "the single most studied and debated i dea with the field of leadership" (Diaz-Saenz, 2011, p. 299). Published studies link TL to CEO success (Jung, Wu, & Chow, 2008), middle manager effectiveness (Singh & Krishnan, 2008), military leadership (Eid, Johnsen, Bartone, & Nissestad, 2008), cross-cultural leadership (Kirkman, Chen, Farh, Chen, & Lowe, 2009), virtual teams (Hambley, O'Neill, & Kline, 2007), personality (Hautala, 2006), emotional intelligence (Barbuto & Burbach, 2006), and a variety of other topics (Diaz-Saenz, 2011). Burns (1978) operationalized the theory of TL as one of two leadership styles represented as a dichotomy: transformational and transactional leadership. While distinct from the concept of charismatic leadership (see Weber, 1924/1947), charisma is an element of TL (Bass, 1985; 1990; 2000; 2008; Bass & Riggio, 2006; Conger, 1999; 2011; Conger & Hunt, 1999; Diaz-Saenz, 2011). Burns (1978) defined a transformational leader as "one who raises the followers' level of consciousness about the importance and value of desired outcomes and the methods of reaching those outcomes" (p. 141). The transformational leader convinced his followers to transcend their self-interest for the sake of the organization, while elevating "the followers' level of need on Maslow's (1954) hierarchy from lower-level concerns for safety and security to higher-level needs for achievement and self-actualization" (Bass, 2008, p. 619). Based on empirical evidence, Bass (1985) modified the original TL construct. Over time, four factors or components of TL emerged. These components include idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration. Researchers frequently group the first two components together as charisma (Bass & Riggio, 2006). The transformational leader exhibits each of these four components to varying degrees in order to bring about desired organizational outcomes through their followers (Bass 1985; 1990; 2000; Bass & Riggio, 2006). Idealized influence incorporates two separate aspects of the follower relationship. First, followers attribute the leader with certain qualities that followers wish to emulate. Second, leaders impress followers through their behaviors. Inspirational motivation involves behavior to motivate and inspire followers by providing a shared meaning and a challenge to those followers. Enthusiasm and optimism are key characteristics of inspirational motivation (Bass & Riggio, 2006). Intellectual stimulation allows leaders to increase their followers' efforts at innovation by questioning assumptions, reframing known problems, and applying new frameworks and perspectives to old and established situations and challenges (Bass & Riggio, 2006). Intellectual stimulation requires openness on the part of the leader. Openness without fear of criticism and increased levels of confidence in problem solving situation combine to increase the self-efficacy of followers. Increased self-efficacy leads to increased effectiveness (Bandura, 1977). Individualized consideration involves acting as a coach or mentor in order to assist followers with reaching their full potential. Leaders provide learning opportunities and a supportive climate (Bass & Riggio, 2006). These four components combine to make leaders transformational figures. In spite of significant empirical support, a number of criticisms of TL theory exist.

Criticisms of transformational leadership

Empirical research supports the idea that TL positively influences follower and organizational performance (Diaz-Saenz, 2011). However, a number of scholars criticize TL (Beyer, 1999; Hunt, 1999; Yukl, 1999; 2011). Yukl (1999) took TL to task and many of his criticisms retain their relevance today. He noted that the underlying mechanism of leader influence at work in TL was unclear and that little empirical work existed examining the effect of TL on work groups, teams, or organizations. He joined other authors and noted an overlap between the constructs of idealized influence and inspirational motivation (Hunt, 1999; Yukl, 1999). Yukl suggested that the theory lacked sufficient identification of the impact of situational and context variables on leadership effectiveness (1999; 2011). Despite its critics, an ongoing and vibrant body of research exists on TL and an analysis of two recent articles follows below.

Recent articles on transformational leadership

Gundersen, Hellesoy, and Raeder (2012) studied TL and leadership effectiveness in international project teams facing dynamic work environments. As noted previously, Paul and Elder (2008) presented guidelines for the analysis of research articles. The article presented an examination of the relationship between TL and work adjustment including the mediating role of trust. The research questions created included the relationship between TL and team performance, the mediating role of trust, the moderating role of a dynamic work environment, the relationship between TL and work adjustment, and the relationship between TL and job satisfaction. Information contained in the article included brief reviews of TL, team performance, dynamic work environment, trust, work adjustment, and job satisfaction. The article also discussed the study sample, measures, statistical procedures, limitations, future research suggestions, implications, and overall conclusion. The specific concepts presented included TL, trust, dynamic work environment, team performance, work adjustment, and job satisfaction. The assumptions of the authors included three explicit premises. The suitability of TL varies according to context, the need for additional empirical work on the relationship between TL and team outcomes exists, and no previous empirical studies on work adjustment in international settings as an outcome of leader behaviors exists (Gundersen et al., 2012). The authors write from a quantitative, positivist, objectivist viewpoint with a confirmatory purpose. The authors hypothesized a correlation between independent and dependent variables and then set out to investigate and confirm that relationship (Creswell, 2009). Gundersen et al. (2012) argue that their study increases knowledge of the drivers of organizational effectiveness. Specifically, TL behaviors affect performance on international assignments in a variety of complex projects by contributing to work adjustment and positive outcomes. These implications apply to high-stakes organizational outcomes including selection of organizational leaders. Another TL study follows below.

Hamstra, Yperen, Wisse, and Sassenberg (2011) studied transformational (and transactional) leadership style in relation to followers' preferred regulatory style, workforce stability, and organizational effectiveness. The authors intended to address a gap in the leadership literature by addressing regulatory fit in the context of turnover intentions, while integrating both transformational and transactional leadership and examining both promotion and prevention focused regulatory strategies (Hamstra et al., 2011). The research addressed the relationship between TL and turnover intentions, given a promotion-focused regulatory strategy, given a prevention-focused regulatory strategy; and the relationship between transactional leadership and turnover intentions given a promotion-focused regulatory strategy, and given a prevention-focused regulatory strategy. Information contained in the article included a brief discussion of TL, transactional leadership, workforce turnover intentions, regulatory strategy, participants and procedures, measures used, results, and a general discussion of the research findings. The specific concepts enumerated above include transactional and TL style, and followers' regulatory focus. The authors assumed that leadership influences followers turnover intentions, that a match between followers self-regulatory strategy influences organizational outcomes, and that leadership style preferences may fit with regulatory style preferences. The authors worked from a positivist, objectivist, and confirmatory point of view. The authors hypothesized a correlation between independent and dependent variables and then set out to investigate and confirm that relationship (Creswell, 2009). Hamstra et al. (2011) discussed several implications of the study including the idea that tailoring specific leadership behaviors or styles to followers prefer self-regulatory orientation may improve employee retention, organizational stability, and the engagement of followers. The authors recommended further research on the relationship between leadership style, turnover intention, and follower commitment. The authors also suggested additional research on preferred self-regulatory orientation and other organizational outcomes variables. The next section of the manuscript explores transactional leadership theory.

Transactional leadership

Transactional leadership focuses on the exchanges that occur between leaders and followers (Bass 1985; 1990; 2000; 2008; Burns, 1978). These exchanges allow leaders to accomplish their performance objectives, complete required tasks, maintain the current organizational situation, motivate followers through contractual agreement, direct behavior of followers toward achievement of established goals, emphasize extrinsic rewards, avoid unnecessary risks, and focus on improve organizational efficiency. In turn, transactional leadership allows followers to fulfill their own self-interest, minimize workplace anxiety, and concentrate on clear organizational objectives such as increased quality, customer service, reduced costs, and increased production (Sadeghi & Pihie, 2012). Burns (1978) operationalized the concepts of both transformational and transactional leadership as distinct leadership styles. Transactional leadership theory described by Burns (1978) posited the relationship between leaders and followers as a series of exchanges of gratification designed to maximize organizational and individual gains. Transactional leadership evolved for the marketplace of fast, simple transactions among multiple leaders and followers, each moving from transaction to transaction in search of gratification. The marketplace demands reciprocity, flexibility, adaptability, and real-time cost-benefit analysis (Burns, 1978). Empirical evidence supports the relationship between transactional leadership and effectiveness in some settings (Bass, 1985; 1999; 2000; Bass, Avolio, Jung, & Berson, 2003; Bass & Riggio, 2006; Hater & Bass, 1988; Zhu, Sosik, Riggio, & Yang, 2012). Today, researchers study transactional leadership within the continuum of the full range of leadership model (Bass & Riggio, 2006). Some researchers criticize transactional leadership.

Criticisms of transactional leadership

Burns (1978) argued that transactional leadership practices lead followers to short-term relationships of exchange with the leader. These relationships tend toward shallow, temporary exchanges of gratification and often create resentments between the participants. Additionally, a number of scholars criticize transactional leadership theory because it utilizes a one-size-fits-all universal approach to leadership theory construction that disregards situational and contextual factors related organizational challenges (Beyer, 1999; Yukl, 1999; 2011; Yukl & Mahsud, 2010). Empirical support for transactional leadership typically includes both transactional and transformational behaviors (Gundersen et al., 2012; Liu, Liu, & Zeng, 2011). Next, this manuscript reviews two recent articles featuring transactional leadership theory.

Recent articles on transactional leadership

Liu et al. (2011) looked at the relationship between transactional leadership and team innovativeness. The authors focused on the potential moderating role of emotional labor and examined a mediating role for team efficacy. The authors intended to contribute to the leadership field by closing an identified gap in the literature with the introduction of emotional labor and team efficacy as important factors in the existing relationship between transactional leadership and team innovativeness. The authors predicted a significant negative relationship between transactional leadership and team innovativeness. The article included an overview discussion of teams, innovativeness, transactional leadership, emotional labor, and team efficacy. The authors assumed that transactional leadership could foster team innovativeness in some settings. The authors also assumed that emotional labor was a moderating factor in that relationship. Liu et al. (2011) conducted the study from the quantitative, positivist, objectivist, and confirmatory point of view. The authors hypothesized a correlation between independent and dependent variables and then set out to investigate and confirm that relationship (Creswell, 2009). Liu et al. (2011) discussed several implications of their findings. Emotional labor acts as a boundary condition on the relationship between transactional leadership and team innovativeness. This knowledge helps deepen the understanding of the context in which transactional leadership leads to organizational effectiveness. Liu et al. (2011) recommended additional research on transactional leadership and other positive organizational outcomes, and additional research on other possible boundary conditions. The next section addresses another study on transactional leadership.

Groves and LaRocca (2011) studied both transactional and TL in the context of ethical behavior. In contrast to the full range of leadership model view of transactional leadership as part of a continuum of behaviors, Groves and LaRocca see transactional leadership and TL as distinct constructs underpinned by separate ethical foundations. Specifically, transactional leadership flows from "teleological ethical values (utilitarianism)" and TL flows from "deontological ethical values (altruism, universal rights, Kantian principle, etc.)" (Groves & LaRocca, 2011, p. 511). While an in-depth discussion of ethics is outside the scope of this manuscript, it is noteworthy that other authors (Bass & Steidlmeier, 1999; Singh & Krishnan, 2008) also discussed the relationship between ethics and transactional leadership. The concepts presented by Groves and LaRocca (2011) include corporate social responsibility, ethics, TL, transactional leadership, and managerial decision-making. The authors examined ethics in relation to leadership style and its impact on follower values and corporate social responsibility. The point of view presented by the authors is quantitative, positivist, objective, and confirmatory as evidenced by a research design that hypothesizes a correlation between independent and dependent variables and then set out to investigate and confirm that relationship (Creswell, 2009). Liu et al. (2011) confirmed empirical support for their view. Author identified limitations included: results oriented toward leaders description of what they would do rather than actual behavior, omission of measures designed to identify social desirability, and inability to generalize findings to the larger population. Additional limitations mentioned included potential common source and common method bias, lack of longitudinal data, follower response bias, and an inability to separate personal ethics from preferred leadership style (Liu et al., 2011). The authors suggested additional research to address these limitations. Next, this manuscript summarizes the key concepts in situational, transformational, and transactional leadership.

Situational, Transformational, and Transactional Leadership

This manuscript analyzes three seminal leadership theories: situational leadership, TL, and transactional leadership. Situational leadership emphasized leadership behaviors along a continuum between task-orientation in relation-orientation. Situational leadership also emphasized the level of maturity, or readiness of the followers as a contingency or context that leaders need to account for in order to establish the correct fit between the leader and follower (Bass, 2008). In TL, leaders achieve results by employing idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration (Bass, 2000; 2008; Bass & Riggio, 2006). The transformational leader exhibits each of these four components to varying degrees in order to bring about desired organizational outcomes through their followers (Bass & Riggio, 2006). Transformational leaders share a vision, inspire followers, mentor, coach, respect individuals, foster creativity, and act with integrity (Bass, 1990; 1999; 2008; Bass & Riggio, 2006).

Transactional leadership involves exchanges between leaders and followers designed to provide benefits to both. Leaders influence followers through contingent rewards and negative feedback or corrective coaching. Despite originating as distinct constructs, transactional and TL exist as parts of another leadership model, the full range of leadership model (Bass & Riggio, 2006). One notable difference between these three leadership theories involves the subject of charisma (Conger, 1999; 2011; Conger & Hunt, 1999; Hunt, 1999; Shamir & Howell, 1999).

Many scholars combine idealized influence and inspirational motivation under the heading charismatic-inspirational leadership or simply charismatic leadership (Bass, 2008; Bass & Riggio, 2006; Hunt, 1999; Shamir & Howell, 1999). The concept of charisma in entered the social sciences from religion through the work of Max Weber (1924/1947). In contrast to TL, both situational and transactional leadership theories ignore the role of individual differences between leaders (Bass, 2008). Charisma is a key example of one such individual difference.

Summary of key differences and similarities

As described above, similarities exist between task-oriented leadership and transactional leadership (Bass, 1985; 1990; 1999; Bass & Riggio, 2006; Burns, 1978). Both focus on the exchange between leaders and followers and both emphasize work products or outcomes. Relation-oriented leadership compares to TL (Bass 1985; 1990; 1999; Burns 1978; Conger, 2011), authentic leadership (Avolio, 2010; Bass, 2008; Caza & Jackson, 2011), and servant leadership (Bass, 2008). Relation-oriented leadership is people focused, inspirational, persuasive, and intellectually stimulating (Bass, 2008). Both situational leadership theory and transactional leadership focus on leadership behaviors to the exclusion of leadership traits or individual differences, while TL looks at leadership behaviors and individual differences. Transactional and TL theories involve universal approaches to leadership. TL applies to a wide range of situations and contexts and evidence suggests TL fits a variety of diverse cultural contexts (Den Hartog, House, Hanges, Ruiz-Quintanilla, & Dorfman, 1999; Leong, 2011; Rowold & Rohmann, 2009; Tsai, Chen, & Cheng, 2009; Zhu et al., 2012). In contrast, situational leadership theories and contingent leadership approaches advocate for the right leadership style and behaviors for the context and situation faced by the organization (Bass, 2008; Hersey & Blanchard, 1969; 1979; 1996; Yukl, 1999, 2008; 2011). Transformational and transactional leadership theories, and the corresponding full range of leadership theory, continue to add to an impressive 30-year history of empirical support (Diaz-Saenz, 2011; Gundersen et al., 2012; Hamstra et al., 2011; Judge & Piccolo, 2004; Leong, 2011; Reichard, Riggio, Guerin, Oliver, Gottfried, & Gottfried, 2009; Yukl; 2011). However, 30 years of history does not guarantee that transformational and transactional leadership adequately address the challenges facing the modern field of leadership.

Contemporary Leadership Challenges and the Future of Leadership Development

A vital challenge to the academic leadership field involves the need to develop leaders and leadership. Day (2011) argued that over time, some leaders developed "the erroneous belief that leadership develops mainly in leadership development programs" (p. 37). Historically, leadership development targeted specific skills and competencies, while focusing on diffusion of best practices. For example, leadership development programs target self-management strategies, social competencies, and work facilitation (Day, 2009). Day (2011) suggested a transition in leadership development beyond the best practices orientation. Day argued for a more scientific approach to developing leaders and leadership. Modern leadership requires a new focus on developing leadership expertise (Day, 2009), new perspectives on the role of leader identity (Day & Harrison, 2007), and the development of adaptive leadership capacity (DeRue & Wellman, 2009). Each of the three leadership theories discussed in this manuscript approaches the subject of leadership development differently.

Situational leadership theory advocates matching the leader to the situation if possible or matching the leadership orientation (task versus relation) to the follower maturity (Hersey & Blanchard, 1969; 1979; 1996). Leadership development efforts aimed at improving organizational effectiveness should use instruments designed to gauge the level of task- orientation and relation-orientation of the leader in order to establish a fit with the current level of follower maturity. Existing leaders should receive skills and competency training aimed at developing their task-oriented or relational-oriented skill deficits. Previous empirical research indicated that level of follower maturity related to previous education and training interventions (Bass, 2008; Hersey & Blanchard, 1969; 1979; 1996).

Bass & Riggio (2006) suggested that TL development could not focus on specific, narrow skills. Bass (2008) argued for TL as a reflection of the "whole integrated person and their deeply held values and self-concepts" (p. 1106). Development in TL requires a broadly established educational process. Burns (1978) agreed, advocating for the joint involvement of facilitators and students in an effort to reach "higher stages of moral reasoning" and higher levels of individual judgment (Burns, 1978, p. 449). Based on these recommendations for a broad educational process, targeting the leader's values and self-concepts, aimed at higher stages of moral reasoning, it is reasonable to doubt whether TL development is possible. This represents another key difference between TL and situational leadership.

The extant leadership literature provides little guidance on transactional leadership development. This may stem from the fact that most leaders do not need development to behave transactionally with their followers. Transactional leadership is traditional leadership (Burns, 1978). As Weber (1924/1947) indicated, a system of operation and coordination is called "traditional" if it is part of an existing system of control, and if the leader enjoys authority based on status and on the existence of personal loyalty created through a process of education (p. 341). This process of education is transactional leadership development. Real-world examples, available practice, and on-the-job training opportunities abound for the leader attempting to develop their transactional leadership behaviors. This manuscript closes with a brief description of the future of leadership.

Bass (2008) predicted the continued importance of both personal traits and situations to leadership. Bass argued that large, purely transactional organizations would give way to transformational ones as modern leaders become more innovative, responsive, flexible, and adaptive (Bass, 2008). The study of leadership marches on toward follower-centered approaches (Bligh, 2011), hybrid configurations (Gronn, 2011), complexity theory (Uhl-Bien & Marion, 2011), and a variety of other arenas. The increase in theoretical pluralism, evident since the 90s, continues as the academic field of leadership continues its search for the truth (Bryman, Collinson, Grint, Jackson, & Uhl-Bien, 2011). Leadership scholars must continue to engage in thorough and thoughtful research into the connections between development and efficacy, organizations and outcomes, and between leaders and followers. That is both the future challenge and the historical past of leadership.

Arvidsson, M., Johansson, C. R., Ek, Å., & Akselsson, R. (2007). Situational leadership in air traffic control. Journal of Air Transportation, 12(1), 67-86. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.capella.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com.library.capella.ed u/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=25644644&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Avolio, B. J. (2010). Pursuing authentic leadership development. In N. Nohria, & R. Khurana (Eds.), Handbook of leadership theory and practice (pp. 739-765). Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership: Good, better, best. Organizational Dynamics, 13(3), 26-40. doi:10.1016/0090-2616(85)90028-2

Bass, B. M. (1990). From transactional to transformational leadership: Learning to share the vision. Organizational Dynamics, 18(3), 19-31. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.capella.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com.library.capella.ed u/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=9607211357&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Bass, B. M. (1999). Two decades of research and development in transformational leadership. European Journal of Work & Organizational Psychology, 8(1), 9-32. doi:10.1080/135943299398410

Bass, B. M. (2000). The future of leadership in learning organizations. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 7(3), 18-40. doi:10.1177/107179190000700302

Bass, B. M. (2008). The Bass handbook of leadership: Theory, research, & managerial applications (4th ed.). New York, NY: Free Press.

Bass, B. M., Avolio, B. J., Jung, D. I., & Berson, Y. (2003). Predicting unit performance by assessing transformational and transactional leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(2), 207-218. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.2.207

Bass, B. M., & Riggio, R. E. (2006). Transformational leadership (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Bass, B. M., & Steidlmeier, P. (1999). Ethics, character, and authentic transformational leadership behavior. The Leadership Quarterly, 10(2), 181-217. doi:10.1016/S1048- 9843(99)00016-8

Beyer, J. M. (1999). Taming and promoting charisma to change organizations. The Leadership Quarterly, 10(2), 307-330. doi:10.1016/S1048-9843(99)00019-3

Bligh, M. C. (2011). Followership and follower-centered approaches. In A. Bryman, D. Collinson, K. Grint, B. Jackson & M. Uhl-Bien (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of leadership (pp. 425-436). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bryman, A., Collinson, D., Grint, K., Jackson, B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (Eds.). (2011). The SAGE handbook of leadership. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Caza, A., & Jackson, B. (2011). Authentic leadership. In A. Bryman, D. Collinson, K. Grint, B. Jackson & M. Uhl-Bien (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of leadership (pp. 352-364). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Conger, J. A. (1999). Charismatic and transformational leadership in organizations: An insider's perspective on these developing streams of research. The Leadership Quarterly, 10(2), 145-179. doi:10.1016/S1048-9843(99)00012-0

Conger, J. A. (2011). Charismatic leadership. In A. Bryman, D. Collinson, K. Grint, B. Jackson & M. Uhl-Bien (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of leadership (pp. 86-102). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Conger, J. A., & Hunt, J. G. (1999). Charismatic and transformational leadership: Taking stock of the present and future (part i). The Leadership Quarterly, 10(2), 121-127. doi: 10.1016/S1048-9843(99)00017-X

Creswell, J. H. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Cubero, C. G. (2007). Situational leadership and persons with disabilities. Work, 29(4), 351-356. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.capella.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com.library.capella.ed u/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=27621294&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Day, D. V. (2009). Executive selection is a process not a decision. Industrial & Organizational Psychology, 2(2), 159-162. doi:10.1111/j.1754-9434.2009.01126.x

Day, D. V. (2011). Leadership development. In A. Bryman, D. Collinson, K. Grint, B. Jackson & M. Uhl-Bien (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of leadership (pp. 37-50). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Day, D. V., & Harrison, M. M. (2007). A multilevel, identity-based approach to leadership development. Human Resource Management Review, 17(4), 360-373. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2007.08.007

Den Hartog, D. N., House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Ruiz-Quintanilla, S. A., & Dorfman, P. W. (1999). Culture specific and cross-culturally generalizable implicit leadership theories: Are attributes of charismatic/transformational leadership universally endorsed? The Leadership Quarterly, 10(2), 219-256. doi:10.1016/S1048-9843(99)00018-1

DeRue, D. S., & Wellman, N. (2009). Developing leaders via experience: The role of developmental challenge, learning orientation, and feedback availability. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(4), 859-875. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.capella.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com.library.capella.ed u/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=42838422&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Diaz-Saenz, H. R. (2011). Transformational leadership. In A. Bryman, D. Collinson, K. Grint, B. Jackson & M. Uhl-Bien (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of leadership (pp. 299-310). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Eid, J., Johnsen, B. H., Bartone, P. T., & Nissestad, O. A. (2008). Growing transformational leaders: Exploring the role of personality hardiness. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 29(1), 4-23. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org.library.capella.edu/10.1108/01437730810845270

Glynn, M. A., & DeJordy, R. (2010). Leadership through an organizational behavior lens: A look at the last half-century of research. In N. Nohria, & R. Khurana (Eds.), Handbook of leadership and practice (pp. 119-158). Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.

Graeff, C. L. (1997). Evolution of situational leadership theory: A critical review. The Leadership Quarterly, 8(2), 153-170. doi:10.1016/S1048-9843(97)90014-X

Grint, K. (2011). A history of leadership. In A. Bryman, D. Collinson, K. Grint, B. Jackson & M. Uhl-Bien (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of leadership (pp. 3-14). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Gronn, P. (2011). Hybrid configurations of leadership. In A. Bryman, D. Collinson, K. Grint, B. Jackson & M. Uhl-Bien (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of leadership (pp. 437-454). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Groves, K. S., & LaRocca, M. A. (2011). An empirical study of leader ethical values, transformational and transactional leadership, and follower attitudes toward corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 103(4), 511-528. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org.library.capella.edu/10.1007/s10551-011-0877-y

Gundersen, G., Hellesoy, B. T., & Raeder, S. (2012). Leading international project teams: The effectiveness of transformational leadership in dynamic work environments. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 19(1), 46-57. doi:10.1177/1548051811429573

Hambley, L. A., O'Neill, T. A., & Kline, T. J. B. (2007). Virtual team leadership: The effects of leadership style and communication medium on team interaction styles and outcomes. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 103(1), 1-20. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.09.004

Hamstra, M. R. W., Van Yperen, N. W., Wisse, B., & Sassenberg, K. (2011). Transformational- transactional leadership styles and followers' regulatory focus: Fit reduces followers' turnover intentions. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 10(4), 182-186. doi:10.1027/1866- 5888/a000043

Hater, J. J., & Bass, B. M. (1988). Superior's evaluations and subordinates' perceptions of transformational and transactional leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 73(4), 695- 702. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.capella.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com.library.capella.ed u/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=5111775&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Hautala, T.M. (2006). The relationship between personality and transformational leadership. Journal of Management Development, 25(8), 777-794. doi:10.1108/02621710610684259

Hersey, P., & Blanchard, K. H. (1969). Life cycle theory of leadership. Training & Development Journal, 23(5), 26. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.capella.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com.library.capella.ed u/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=7465530&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Hersey, P., & Blanchard, K. H. (1979). Life cycle theory of leadership. Training & Development Journal, 33(6), 94. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.capella.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com.library.capella.ed u/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=9067469&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Hersey, P., & Blanchard, K. H. (1980). The management of change. Training & Development Journal, 34(6), 80. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.capella.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com.library.capella.ed u/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=9072349&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Hersey, P., & Blanchard, K. H. (1981). So you want to know your leadership style? Training & Development Journal, 35(6), 34. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.capella.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com.library.capella.ed u/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=7471134&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Hersey, P., & Blanchard, K. H. (1996). Great ideas revisited: Revisiting the life-cycle theory of leadership. Training & Development Journal, 50(1), 42.

Hunt, J. G. (1999). Transformational/charismatic leadership's transformation of the field: An historical essay. The Leadership Quarterly, 10(2), 129-144. doi:10.1016/S1048- 9843(99)00015-6

Judge, T. A., & Piccolo, R. F. (2004). Transformational and transactional leadership: A meta- analytic test of their relative validity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(5), 755-768. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.89.5.755

Jung, D., Wu, A., & Chow, C. W. (2008). Towards understanding the direct and indirect effects of CEOs' transformational leadership on firm innovation. The Leadership Quarterly, 19(5), 582-594. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.07.007

Kirkman, B. L., Chen, G., Farh, J.-L., Chen, Z., & Lowe, K. B. (2009). Individual power distance orientation and follower reactions to transformational leaders: A cross-level, cross-cultural examination. Academy of Management Journal, 52(4), 744-764. doi:10.5465/AMJ.2009.43669971

Larsson, J., & Vinberg, S. (2010). Leadership behaviour in successful organisations: Universal or situation-dependent? Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 21(3), 317-334. doi:10.1080/14783360903561779

Leong, L. Y. C. (2011). Is transformational leadership universal? A meta-analytical investigation of multifactor leadership questionnaire means across cultures. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 18(2), 164-174. doi:10.1177/1548051810385003

Liu, J., Liu, X., & Zeng, X. (2011). Does transactional leadership count for team innovativeness? Journal of Organizational Change Management, 24(3), 282-298. doi:10.1108/09534811111132695

Lorsch, J. W. (2010). A contingency theory of leadership. In N. Nohria, & R. Khurana (Eds.), Handbook of leadership theory and practice (pp. 411-432). Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.

Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. New York, NY: Harper.

Nicholls, J. R. (1985). A new approach to situational leadership. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 6(4), 2.

Paul, R. & Elder, L. (2008). The miniature guide to critical thinking. ( No. 520m). www.criticalthinking.org: Foundation for Critical Thinking Press. Retrieved from http://courseroom2.capella.edu/webct/RelativeResourceManager/Template/OM8004/Cour se_Files/cf_Miniature_Guide_to_Critical_Thinking-Concepts_and_Tools.pdf

Reichard, R. J., Riggio, R. E., Guerin, D. W., Oliver, P. H., Gottfried, A. W., & Gottfried, A. E. (2011). A longitudinal analysis of relationships between adolescent personality and intelligence with adult leader emergence and transformational leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(3), 471-481. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.04.005

Rost, J. C. (1993). Leadership development in the new millennium. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 1(1), 91-110. doi:10.1177/107179199300100109

Rowold, J., & Rohmann, A. (2009). Transformational and transactional leadership styles, followers' positive and negative emotions, and performance in German nonprofit orchestras. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 20(1), 41-59. doi:10.1002/nml.240

Sadeghi, A., & Pihie, Z. A. L. (2012). Transformational leadership and its predictive effects on leadership effectiveness. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(7), 186- 197.

Shamir, B., & Howell, J. M. (1999). Organizational and contextual influences on the emergence and effectiveness of charismatic leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 10(2), 257-283. doi:10.1016/S1048-9843(99)00014-4

Shin, J., Heath, R. L., & Lee, J. (2011). A contingency explanation of public relations practitioner leadership styles: Situation and culture. Journal of Public Relations Research, 23(2), 167-190. doi:10.1080/1062726X.2010.505121

Singh, N., & Krishnan, V. R. (2008). Self-sacrifice and transformational leadership: Mediating role of altruism. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 29(3), 261-274. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org.library.capella.edu/10.1108/01437730810861317

Tsai, W., Chen, H., & Cheng, J. (2009). Employee positive moods as a mediator linking transformational leadership and employee work outcomes. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(1), 206-219. doi:10.1080/09585190802528714

Uhl-Bien, M., & Marion, R. (2011). Complexity leadership theory. In A. Bryman, D. Collinson, K. Grint, B. Jackson & M. Uhl-Bien (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of leadership (pp. 468- 482). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Weber, M. (1947). The theory of social and economic organization (T. Parsons Trans.). New York, NY: Free Press. (Original work published in 1924)

Yukl, G. (1999). An evaluation of conceptual weaknesses in transformational and charismatic leadership theories. The Leadership Quarterly, 10(2), 285-305. doi:10.1016/S1048- 9843(99)00013-2

Yukl, G. (2008). How leaders influence organizational effectiveness. The Leadership Quarterly, 19(6), 708-722.

Yukl, G. (2011). Contingency theories of effective leadership. In A. Bryman, D. Collinson, K. Grint, B. Jackson & M. Uhl-Bien (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of leadership (pp. 286- 298). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Yukl, G., & Mahsud, R. (2010). Why flexible and adaptive leadership is essential. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 62(2), 81-93. doi:10.1037/a0019835

Zaccaro, S. J. (2007). Trait-based perspectives of leadership. American Psychologist, 62(1), 6- 16. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.62.1.6

Zhu, W., Sosik, J.J., Riggio, R.E. & Yang, B. (2012). Relationships between transformational and active transactional leadership and followers' organizational identification: The role of psychological empowerment. Journal of Behavioral and Applied Management, 13(3), 186.

You have requested "on-the-fly" machine translation of selected content from our databases. This functionality is provided solely for your convenience and is in no way intended to replace human translation. Show full disclaimer

Neither ProQuest nor its licensors make any representations or warranties with respect to the translations. The translations are automatically generated "AS IS" and "AS AVAILABLE" and are not retained in our systems. PROQUEST AND ITS LICENSORS SPECIFICALLY DISCLAIM ANY AND ALL EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTIES, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION, ANY WARRANTIES FOR AVAILABILITY, ACCURACY, TIMELINESS, COMPLETENESS, NON-INFRINGMENT, MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. Your use of the translations is subject to all use restrictions contained in your Electronic Products License Agreement and by using the translation functionality you agree to forgo any and all claims against ProQuest or its licensors for your use of the translation functionality and any output derived there from. Hide full disclaimer

Copyright Journal of Business Studies Quarterly (JBSQ) Jun 2014

Suggested sources

- About ProQuest

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- go to walkme.com

Situational leadership theory: Definition, features & examples

Situational leadership theory could be the missing element in your leadership vision for the challenges of the coming decade.

A leading McKinsey report from 2023 explains why. The successful enterprises of the future will require adaptable management teams to become “open, collaborative, and emergent” businesses. In McKinsey’s terms, this is the exciting trend of the “thriving organization.”

Situational leadership gives useful insights that tools like agile project management miss. It helps to understand staff motivation, respond with appropriate leadership, and then reach goals with high levels of satisfaction. In this article, we’ll explain how.

This article will:

- Define situational leadership theory

- Explain the four leadership behavior types in situational leadership theory

- Explain how situational leadership theory describes motivation through “performance readiness”

- Introduce the major benefits and challenges of situational leadership.

This is one of many articles we have about leadership development . If situational leadership doesn’t work for you, look for links to other content along the way.

What is situational leadership theory?

Situational leadership theory examines the interactions between people, motivation, and leadership choices. It suggests no single “correct” way to give instructions and encourage staff. Rather, managers must effectively handle their interactions with staff to achieve positive organizational outcomes.

This makes organizations seem complicated. As anyone knows, staff can change their motivation levels from one task to the next, and leaders must learn how to respond appropriately.

SLT takes another step by showing how to understand staff motivation and how to respond to it. The pioneers of the theory, Paul Hersey and Ken Blanchard, showed how the “performance readiness” of staff should connect with the “behavior style” of leaders. One of the most famous symbols of situational leadership theory is the “wishbone”-shaped graph, which visually connects these two factors.

In its time, situational leadership solved a specific problem. Many writers suggested that management was a “universal” science. They thought that we would find a basic template for all organizational behavior (if we just did enough work).

In their book Management of Organizational Behavior (1969) , Hersey and Blanchard showed that reality is much more complicated. Many leaders today recognize this. However, the lessons of situational leadership are still a provocative and exciting approach.

After all, it is common to see people arguing for a widespread idea of HR best practices , most notably in Jeffrey Pfeffer’s work. Situational leadership provides a thorough model for context-specific responses to problems and issues.

Like any leadership practice, situational leadership is not perfect. Scholars like Geir Thompson have carefully evaluated the ideas of situational leadership (see their articles in 2009 and 2018 ). Like any leadership theory, this is a set of ideas that adapt and change over time.

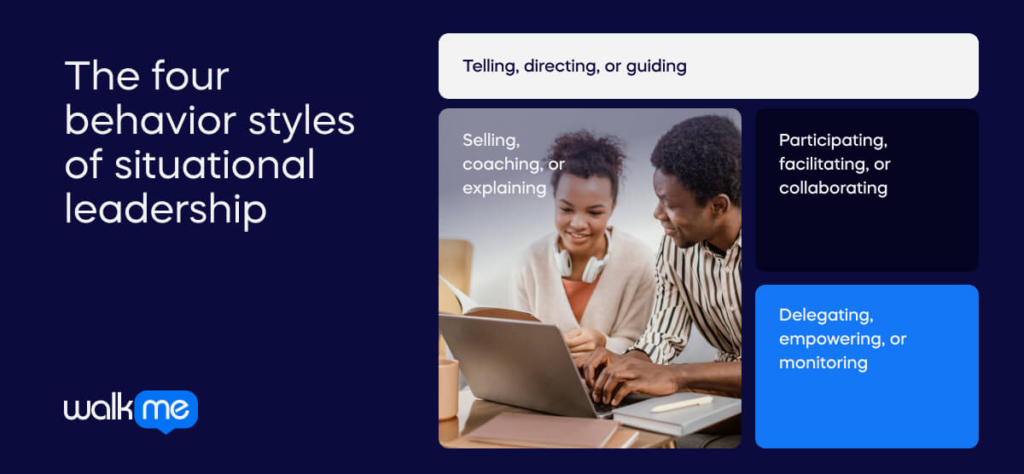

The four behavior styles of situational leadership

Situational Leadership Theory introduces four distinct behavior styles that leaders can employ depending on the readiness level of their team members. These styles are:

- Telling

- Selling

- Participating

- Delegating

These behavior styles balance two important aspects: task behavior and relationship behavior. Task behavior involves giving instructions and guiding the team on what needs to be done. Relationship behavior focuses on building connections and motivation within the team.

In the rest of this section, we will introduce the four major behavior styles in situational leadership.

- Telling, directing, or guiding

In this style, the leader provides specific instructions and closely supervises task completion. This style is most appropriate when followers have low readiness levels and need clear guidance and direction. With “telling,” leaders prioritize task behavior.

Example: A new employee is hired in a manufacturing plant. The supervisor provides detailed instructions on operating a specific machine and closely monitors the employee’s performance during the initial training period.

- Selling, coaching, or explaining

Here, the leader provides both direction and support. They explain decisions, gather input, and encourage questions. This style is effective when followers have moderate readiness levels but still need guidance.

Example: A project manager is leading a team of software developers to create a new application. The manager explains the project’s goals, provides guidance on the development process, and motivates team members by highlighting the importance of their contributions.

- Participating, facilitating, or collaborating

This style involves more delegation and support from the leader. In other words, it prioritizes relationship behavior over task behavior.

Leaders encourage followers to take initiative and make decisions while providing resources and assistance as needed. This style suits followers with moderate to high readiness levels who may benefit from increased autonomy and empowerment.

Example: A department manager encourages her team members to take ownership of their tasks and make decisions regarding project implementation. She offers resources and assistance as needed but trusts her team to manage their responsibilities autonomously.

- Delegating, empowering, or monitoring

In this style, the leader provides minimal direction and support. They allow their followers to take full responsibility for task completion. The leader still monitors progress but grants followers a high degree of autonomy. This style is most appropriate for followers with high readiness levels who can work independently.

This style is low in both task and relationship behavior. It’s appropriate when there’s a high level of trust and understanding between a leader and their team.

Example: A business owner delegates the responsibility of managing day-to-day operations to the store manager. The owner provides general guidelines and expectations but allows the manager to make staffing, inventory management, and customer service decisions without constant oversight.

What are the different types of performance readiness in situational leadership theory?

In Situational Leadership Theory, leadership behaviors align with performance readiness.

Performance readiness is a measure of motivation that gauges how far staff members are prepared to tackle tasks.

These readiness levels, termed “maturity levels” in earlier versions of the theory, include:

- Unable and unwilling

- Unable but willing

Able but unwilling

- Able and willing.

In this section, we will explain the meaning of each one in turn.

Unable and unwilling

At this level, individuals lack the necessary skills or confidence to perform a task and may be unwilling to take on the responsibility.

Example: A new team member joins a marketing project requiring advanced data analysis skills. However, they lack experience with data analysis software and feel overwhelmed by the task’s complexity, leading to reluctance to take it on.

Unable but willing

At this level, individuals are motivated and willing to perform the task but lack the necessary skills or knowledge. They may need guidance, training, or support to complete the task successfully.

Example: A software developer volunteers to lead a new project using a programming language they’re unfamiliar with. Despite their enthusiasm, they require support and mentoring from senior team members to grasp the language and meet project requirements.

Here, individuals have the skills and knowledge required to perform the task but lack the motivation or confidence to do so. They may need encouragement, reassurance, or incentives to take responsibility.

Example: An experienced sales representative is hesitant to take on a leadership role in a client presentation despite having the necessary expertise. They require reassurance and support from their manager to overcome self-doubt and step into the leadership role.

Able and willing

This is the ideal level of performance readiness, where individuals have both the skills and the motivation to perform the task effectively. They are confident and willing to take on responsibility independently.

Example: A seasoned project manager confidently leads a cross-functional team through a complex project, leveraging their expertise and motivation to guide team members toward successful completion.

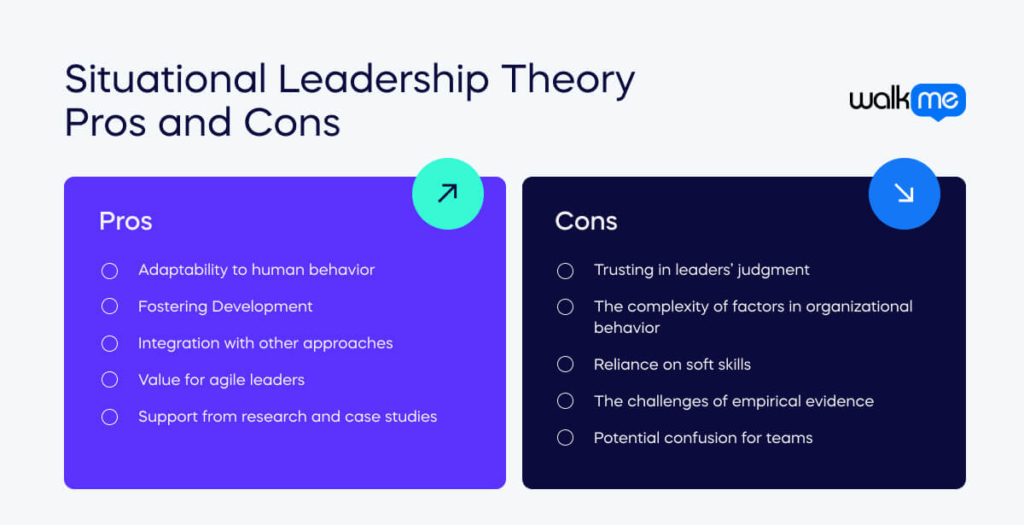

What are the benefits of situational leadership theory?

Situational Leadership Theory has been around for nearly six decades. Yet, it is still vitally important for many leaders. SLT has many distinct benefits that make it very different from other approaches, so it is no surprise that business people keep coming back. The benefits include the following.

Adaptability to human behavior

SLT recognizes the ever-changing nature of human behavior. It helps leaders to respond without relying on rigid responses or cookie-cutter thinking. It can adapt to many situations.

Fostering Development

By emphasizing flexibility and responsiveness, the theory promotes a culture of learning. SLT encourages continuous staff training under the guidance of adaptable leadership.

Integration with other approaches

Situational Leadership works well with other leadership methodologies. For instance, its participatory behavior style aligns well with servant leadership principles. It also goes well with empathetic leadership, promoting understanding and support within teams.

Value for agile leaders

Agile methods benefit significantly from Situational Leadership Theory. Agile allows teams to adapt and innovate. SLT adds to this by helping to define a range of managerial responses when they arise. This collaboration with agile team leadership fosters a dynamic and responsive work environment.

Support from research and case studies

Backed by extensive research and analysis, Situational Leadership Theory offers an academically robust framework supported by a wealth of case studies and examples. This ensures its applicability and effectiveness in addressing real-world challenges.

What are the challenges of situational leadership theory?

As we’ve seen in this article, situational leadership has a lot of positive benefits. However, it is not perfect. Some of the major problems with situational leadership include the following points.

Trusting in leaders’ judgment

SLT places significant emphasis on leaders’ judgment when assessing follower readiness levels. However, this skill may be challenging for many leaders to develop. Accurately gauging readiness requires experience, intuition, and insight, which may not come naturally to all leaders.

The complexity of factors in organizational behavior

Much about SLT “rings true” – it seems like common sense! However, in difficult times, mastering SLT is no small feat. It involves navigating a dynamic landscape of situational factors, individual motivations, and leadership behaviors.

Reliance on soft skills

SLT assumes a foundation of soft skills, such as communication, empathy, and emotional intelligence, essential for effective leadership. However, not all leaders possess these skills innately. Incorporating SLT into leadership training programs alongside other soft skills development initiatives can address this challenge.

The challenges of empirical evidence

Producing clear-cut empirical evidence to validate SLT can be challenging. As a result, SLT may be better suited as a subjective approach rather than relying solely on empirical evidence.

Potential confusion for teams

Constantly shifting leadership behaviors based on situational factors may confuse teams and undermine stability. Teams may struggle to understand and adapt to rapidly changing leadership styles, leading to uncertainty and inefficiency.

Navigating these challenges requires leaders to approach SLTs with humility, adaptability, and a commitment to development.

Why situational leadership is so effective

Today, Business leaders know they need emotional intelligence (EQ) to match their academic intelligence (IQ). SLT opens doors for a generation of leaders who wear their soft skills on their sleeves.

The theory can challenge the status quo by addressing the lack of diversity in leadership teams.

The possibilities of SLT remind us just how far we’ve come from the theories of “scientific management” in the first part of the twentieth century. Businesses, organizations, and people have all changed beyond recognition, and SLT is one of many postmodern leadership theories that address these challenges.

Like what you are reading?

Sign up for our weekly digest of the latest digital trends and insights delivered straight to your inbox.

By clicking the button, you agree to the Terms and Conditions . Click Here to Read WalkMe's Privacy Policy

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Thanks for subscribing to WalkMe’s newsletter!

- Creative & Design

- See all teams

For industries

- Manufacturing

- Professional Services

- Consumer Goods

- Financial Services

- See all industries

- Resource Management

- Project Management

- Workflow Management

- Task Management

- See all use cases

Explore Wrike

- Book a Demo

- Take a Product Tour

- ROI Calculator

- Customer Stories

- Start with Templates

- Gantt Charts

- Custom Item Types

- Project Resource Planning

- Project Views

- Kanban Boards

- Dynamic Request Forms

- Cross-Tagging

- See all features

- Integrations

- Mobile & Desktop Apps

- Resource Hub

- Educational Guides

Upskill and Connect

- Training & Certifications

- Help Center

- Wrike's Community

- Premium Support Packages

- Wrike Professional Services

Implementing the Situational Leadership Theory in Project Management

June 11, 2023 - 10 min read

In the ever-evolving world of project management , effective leadership is a crucial factor in achieving the success of any endeavor. One leadership theory that has gained traction in recent years is the Situational Leadership Theory. This theory recognizes that different situations require different leadership styles and that effective leaders are those who can adapt their approach to suit the needs of their team. In this article, we will explore the basics of Situational Leadership Theory, its importance in project management, steps to implement this theory, real-world case studies, and challenges associated with its implementation.

Understanding the Basics of Situational Leadership Theory

Developed by entrepreneur Paul Hersey and writer Kenneth Blanchard, the Situational Leadership Theory is based on the premise that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to leadership. Instead, it emphasizes the importance of adjusting leadership behaviors based on the maturity level of the team members and the specific task at hand. Leaders who can effectively diagnose the development level of their team members and apply the appropriate leadership style are more likely to achieve positive outcomes.

The Four Leadership Styles in Situational Leadership Theory

Based on the staff's development level, leaders can adopt one of four leadership styles: directing, coaching, supporting, or delegating. Each style is tailored to the specific needs of the team members, ensuring that their growth and success are maximized.

- Directing: Appropriate when team members are low on both competence and commitment. In such situations, leaders take a more hands-on approach, providing explicit instructions and closely monitoring progress.

- Coaching: Suitable when team members have low competence but high commitment. In this style, leaders focus on both task accomplishment and personal development. They provide guidance and support, offering constructive feedback and helping team members enhance their skills.

- Supporting: Perfect for team members with high competence but low commitment. In this style, leaders facilitate and empower the team, providing support and encouragement.

- Delegating: For team members who have high competence and high commitment. In this style, leaders allow the team to take ownership and make decisions autonomously.

The Importance of Situational Leadership in Project Management

Effective project management relies on leaders who can maximize team performance, facilitate effective communication, and promote flexibility and adaptability.

Enhancing Team Performance

By adapting leadership styles based on the development level of team members, project managers can provide the necessary guidance and support for individuals to reach their full potential. This approach boosts team performance by tailoring leadership behaviors to the specific needs of each team member.

Let's consider a project manager who has a team consisting of both experienced professionals and new recruits. The experienced professionals may require less direction and guidance, as they have a high level of competence and commitment. On the other hand, the new recruits may need more support and clear instructions to build their skills and confidence. By using situational leadership, the project manager can adjust their leadership style accordingly, providing the appropriate level of guidance to each team member. This not only helps the new recruits develop their skills but also allows the experienced professionals to work autonomously, leading to improved overall team performance.

Facilitating Effective Communication

Communication is paramount in project management. Situational Leadership Theory encourages leaders to adjust their communication style to align with the competence and commitment of team members. By doing so, leaders can see to it that messages are conveyed effectively and understood by all team members, resulting in improved collaboration and productivity.

Consider a project manager who is leading a team with members from different cultural backgrounds. Each team member may have different communication preferences and styles. Some may prefer direct and concise communication, while others may prefer more detailed and contextualized information. By using situational leadership, the project manager can adapt their communication style to meet the needs of each team member, so that information is effectively transmitted and understood by all. This fosters a positive and inclusive team environment, where everyone feels heard and valued, leading to enhanced team collaboration and ultimately, project success.

Promoting Flexibility and Adaptability

Projects often encounter unexpected challenges and changes. Leaders who embrace Situational Leadership Theory are better equipped to adapt their approach and guide their team through turbulent times. This flexibility ensures that projects remain on track and objectives are met, ultimately leading to project success.

Imagine a project manager who is leading a team working on a complex software development project. Midway through the project, a critical software bug is discovered, requiring immediate attention and a change in the project plan. A project manager who practices situational leadership can quickly assess the situation, gather input from team members, and adapt the project plan accordingly. They may assign additional resources to fix the bug, rearrange priorities, or modify timelines to accommodate the change. By being flexible and adaptable, the project manager can effectively navigate through unexpected challenges, so that the project remains on track and objectives are met.

Steps to Implement Situational Leadership Theory in Project Management

Below are several key steps:

Assessing the Team's Competence and Commitment

To effectively apply Situational Leadership Theory, project managers need to assess the competence and commitment levels of their team members. This assessment can be done through various methods, such as individual interviews, skills assessments, and feedback sessions.

During individual interviews, project managers can have one-on-one conversations with team members to understand their strengths, weaknesses, and areas for improvement. They can conduct skills assessments to objectively measure the technical abilities of team members via tests, simulations, or practical exercises. Lastly, feedback sessions provide an opportunity for project managers to gather insights from team members about their level of commitment and motivation, through open discussions, surveys, or anonymous feedback forms.

Identifying the Appropriate Leadership Style

Once the team's competence and commitment levels have been evaluated, project managers can determine the most suitable leadership style for each team member. The goal is to match the leadership style to the development level of the individual, so that the team member receives the necessary guidance and support to succeed. There are four main leadership styles in Situational Leadership Theory: directing, coaching, supporting, and delegating. They are described above, in the section titled The Four Leadership Styles in Situational Leadership Theory .

Applying the Chosen Leadership Style

After identifying the appropriate leadership style, project managers must implement it effectively. This involves communicating expectations, providing resources and support, and monitoring progress. Regular feedback and coaching sessions can also help team members develop and grow.

When applying the chosen leadership style, project managers need to clearly communicate their expectations to team members. This includes defining project goals, outlining roles and responsibilities, and setting performance standards. Managers must also provide the necessary resources and support to enable team members to succeed. This can include providing access to training and development opportunities, allocating sufficient time and budget for project tasks, and offering guidance and assistance when needed. Lastly, project managers should regularly monitor the progress of team members and provide feedback to help them improve. This can be done through performance evaluations, progress reports, or informal check-ins.

Case Studies of Situational Leadership in Project Management

Here are two case studies that illustrate the inclusion of situational leadership in project management.

Case Study 1: Tech Industry

In a technology company, a project manager utilized Situational Leadership Theory to manage a team of software developers. By identifying the competence and commitment levels of each team member, the project manager was able to adjust their leadership style accordingly. This resulted in increased collaboration, improved technical skills, and higher motivation among team members, leading to the successful completion of the project within the specified time frame.

Case Study 2: Construction Industry

In a construction project, a project manager applied Situational Leadership Theory to effectively guide a diverse team of skilled laborers. By recognizing the development level of each individual and adapting the leadership style accordingly, the project manager made sure that all team members understood their roles and responsibilities. This created a positive working environment, increased productivity, and minimized rework, resulting in the timely completion of the project and high client satisfaction.

Challenges and Solutions in Implementing Situational Leadership

Here are several obstacles in implementing situational leadership, along with tactics to overcome them.

Common Obstacles in Applying Situational Leadership

Implementing Situational Leadership Theory may encounter a few challenges. Some team members may resist changes to their preferred leadership style, or there may be a lack of understanding or awareness about the theory. Additionally, time constraints and resource limitations can pose obstacles to the effective implementation of Situational Leadership Theory in project management.

Effective Strategies to Overcome Challenges

To overcome these challenges, project managers can invest in training and development programs for both leaders and team members, promoting a shared understanding of Situational Leadership Theory. Clear communication and regular feedback can help address resistance and build trust among team members. Additionally, project managers can allocate sufficient time and resources to confirm that the theory is implemented effectively and seamlessly.

Ultimately, implementing the Situational Leadership Theory in project management can greatly enhance team performance, facilitate effective communication, and promote flexibility and adaptability. By understanding the basics of this theory, recognizing its importance, and following the steps to implementation, project managers can create a supportive and productive environment that drives project success. While challenges may arise, with effective strategies, these challenges can be overcome, and the benefits of Situational Leadership Theory can be realized.

Enhance your project management skills by effectively implementing the situational leadership theory with Wrike. Start a free trial and lead your team with adaptability and sensitivity. Note: This article was created with the assistance of an AI engine. It has been reviewed and revised by our team of experts to ensure accuracy and quality.

Occasionally we write blog posts where multiple people contribute. Since our idea of having a gladiator arena where contributors would fight to the death to win total authorship wasn’t approved by HR, this was the compromise.

Related articles