- Open access

- Published: 01 December 2022

Building connections between biomedical sciences and ethics for medical students

- Oluwaseun Olaiya 1 ,

- Travis Hyatt 2 ,

- Alwyn Mathew 2 ,

- Shawn Staudaher 2 ,

- Zachary Bachman 3 &

- Yuan Zhao 4

BMC Medical Education volume 22 , Article number: 829 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

2432 Accesses

1 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

Medical ethics education is crucial for preparing medical students to face ethical situations that can arise in patient care. Instances of ethics being integrated into biomedical science education to build the connection between human science and ethics is limited. The specific aim of this study was to measure student attitudes towards an innovative curriculum design that integrates ethics education directly into a biomedical science course in pre-clinical medical curriculum.

In this cross-sectional study, three ethics learning modules were designed and built in a biomedical science course in the pre-clinical curriculum. All students of Class of 2024 who were enrolled in the course in 2021 were included in the study. Each module integrated ethics with basic science topics and was delivered with different teaching modalities. The first module used a documentary about a well-known patient with severe combined immunodeficiency disease. The second module was delivered through a clinical scenario on HIV infection. The third module used small group discussion and debate on the topic of blood transfusion. For evaluation, students were asked to self-identify the ethical challenges associated with each module and complete reflective writing to assess their knowledge and attitude. Quantitative and qualitative analyses were conducted on student perceptions of each module.

Likert scale ratings on the usefulness of each module revealed significantly higher ratings for the small group discussion/debate module, seconded by the documentary and lastly the case scenario only modules. Narrative analysis on student feedback revealed three themes: General favorable impression , Perceived learning outcomes , and Critiques and suggestion . Common and unique codes were identified to measure the strengths and weaknesses of each module. Overall, students’ perception of the curriculum design was extremely positive.

Conclusions

This curriculum design enabled us to highlight foundational biomedical sciences and clinical conditions with ethical dilemmas that physicians are likely to face in practice. Students found value in the modules, with a preference for the most active learning method. This study provides insight on a novel approach for integrating medical ethics into biomedical science courses that can be tailored to any institution. Strategies learned include utilizing active learning modalities and discussion.

Peer Review reports

Medical ethics is the study of the moral issues inherent in the practice of medicine, including, among many other topics, the moral choices physicians face in their day-to-day interactions with patients, colleagues, and the broader society in which they practice [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Knowledge of medical ethics is crucial for training morally competent healthcare professionals to manage ethical considerations that arise in patient care [ 5 ]. Evolving health care systems, expanding involvement of allied health professionals, and advances in technologies and treatment regimens have given rise to increasingly complex moral dilemmas faced by medical professionals in everyday practice. There is thus a compelling argument to continuously improve the incorporation of medical ethics into both pre-clinical and clinical medical education.

In the Association of American Medical Colleges published curriculum report, 143 out of 145 allopathic medical schools covered medical ethics in either a required or an elective course in 2016-2017 academic year [ 6 ]. The curriculum topics reported by the American Association of College of Osteopathic Medicine shows all osteopathic medical schools checked off medical ethics in a required course or rotation and 21 out of 38 schools had it covered in a selective/elective course or rotation in academic year of 2017-2018 [ 7 ]. Not surprisingly, reports on medical student perspectives of ethics education have revealed strong recognition of the importance of ethics as part of their medical training and a perceived need and desire for more formal bioethical education [ 8 , 9 ]. Although there is consensus from both faculty and students that medical ethics is an important part of medical training, literature suggests notable heterogeneity across medical schools regarding the best practice of teaching medical ethics [ 10 , 11 , 12 ].

Various pedagogical approaches have been employed to teach this subject, including the content, method, and timing of ethics education [ 10 , 13 , 14 ]. In the aspect of curriculum design, ethics inclusion in pre-clinical medical education has been done through various strategies. In addition to the most common traditional stand-alone ethics course, other approaches have also been explored, such as elective courses, students’ medical ethics rounds, a scholarly concentration program, etc [ 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ]. Various formats of delivery have been reported as well, including small group session, case-based teaching, narrative approach, peer-based teaching, team-based learning, etc [ 15 , 19 , 20 , 21 ]. A commonality among these various pedagogical approaches is that the ethics content is delivered in a way that tends to treat ethics as a distinct subject matter that students are required to learn.

A core component of medical education is, of course, also learning the sciences related to understanding the human body. Many of the ethical challenges that doctors face – such as recruiting patients for clinical trials or securing informed consent for an invasive procedure – are directly related to the science that students learn in pre-clinical biomedical education. When an ethics education is cleaved off from the underlying context that gives rise to the ethical issues being studied, it is natural to treat ethics and the sciences core to medicine as inhabiting separate realms: after all, ethics studies how the world ought to be while science studies how the world is . Ethical norms often become viewed as a set of norms externally imposed on scientists and doctors, rather than norms internal to their practice [ 22 ]. But since medicine is fundamentally about using science to treat disease and illness in the context of a doctor-patient relationship, it stands to reason that the aim of the practice of medicine is to use science in a way consistent with the moral norms that govern the doctor-patient relationship. A good doctor, in other words, is one who uses science in an ethical manner to promote healing. Given the way in which ethics and science are interwoven in medical practice, we asked the question whether ethics could be integrated in biomedical science curriculum of pre-clinical medical training. While a review of literature has revealed recent efforts to implement ethics education into science education [ 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ], we couldn’t find any discussion of efforts to embed ethics curriculum within the biomedical science curriculum in particular, except for anatomy [ 27 ].

Given the rationale above, we initiated a project to develop strategies for medical educators to integrate ethics modules into biomedical science courses, with the aim of promoting student awareness of how scientific practice and ethics are interrelated. Our first step in this project, which this paper analyzes, was to assess student attitudes towards the inclusion of ethics modules in pre-clinical biomedical science courses - how will students respond to this new course design? Future objectives, not undertaken here, will be to measure student learning as a result of our interventions, assess the effectiveness of different inclusion strategies, and create a framework that other medical educators can use in their courses.

Our study concerns a curriculum design we implemented that incorporates ethics threads in a pre-clinical biomedical science course using various teaching modalities. Our model enabled us to highlight the pathophysiology and clinical presentations of the disorders, along with ethical dilemmas that physicians are likely to face in clinical practice. By learning biomedical science side-by-side with medical ethics, students could make meaningful connections between the two domains. We believe this pedagogical approach of teaching medical ethics can help students better understand the relationship between science and ethics in medical practice as well as build richer “organizational structures” of knowledge that will aid in the retention and application of information [ 28 , 29 ]. This curriculum design can also shed light on how to incorporate ethics education creatively and effectively in the pre-clinical medical curriculum.

This study was conducted at Sam Houston State University College of Osteopathic Medicine in 2021. Three ethics learning modules were designed and built in a six-week system course “Immune System and HEENT” (HEENT: Head, Eyes, Ears, Nose, Throat) which was offered in the spring semester of the first year of pre-clinical curriculum. In this course, students were introduced to the principles of trauma, inflammatory disorders, infections and cancers associated with HEENT as it relates to the immune system. Students learned to apply the basic concepts of immunology in normal and disease states and to diagnose, prevent, and treat infections, cancers and immunological diseases. All students from our institute who were enrolled in this course in 2021 were included in the study. These students were in their first year of a four-year Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine program. A total of 74 first-year medical students in the Class of 2024 were enrolled in the course and completed all three modules and assessments. Forty were males and thirty-four were females. The average age of the cohort was 26 years ranging from 23 to 45 years.

The learning objectives of the ethics modules were identified and standardized based on the Romanell Report [ 28 ] which reviewed medical ethics education in the United States and offers suggestions for objectives, teaching methods, and assessment strategies.

The design of the three modules is presented in Table 1 .

The first module used a documentary about David Vetter, a well-known pediatric patient with severe combined immunodeficiency disease. After students completed the session “Introduction of the Immune System”, they were provided an asynchronous ethics module in a learning management software and assigned a one-hour long documentary named The Boy in the Bubble released in 2006 by PBS [ 29 ], and then completed the assessments at their own time. The second module used a clinical case on human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) that was introduced in team-based learning (TBL), a form of peer collaboration. This case concerned a patient diagnosed with HIV and the dual roles of physician as mandatory reporter of communicable disease and protector of patient confidentiality. Immediately following the two-hour TBL, the students were provided assessments to be completed on their own. The third module was a one-hour mandatory live session offered 4 days after students completed the session “Blood Transfusion”. The students were given an ethics case about a young Jehovah’s Witness in need of a blood transfusion and asked to complete the assessments in class. They were then sorted into small groups for discussion and subsequently assigned a position to debate on whether the patient should receive the blood transfusion. For all three module assessments, students were provided a list of twenty ethical challenges cited from the Romanell report and were asked to select the challenges that they recognized in the learning module and provide supporting explanations (Additional file 1 : Appendix 1). Reflective writing prompts were included for students to complete on their own for thinking critically about the ethical challenges associated with the module. Module #1 reflective questions were tied to surrogate decision making and informed consent. An example of the reflective writing prompt from Module #1 includes “Would the case have been handled any differently were David a competent adult? At what point should David be considered autonomous and capable of making healthcare decisions? Explain your reasoning.” Module #2 reflective questions were tied to patient confidentiality and the reporting of communicable diseases. Module #3 reflective questions were tied to the impact of religion on clinical decisions. Students were also asked to voluntarily respond to the perception question “How useful did you consider this module in ethics training?” to rate the usefulness of the module on a 1 to 5 Likert scale (1-not useful at all, 5-very useful) and provide feedback. We expected students took 30 min to 1 h to complete all assessments. General feedback were provided by YZ and OO in person or in writing for each module.

Analytical procedure

The analytical procedure was aligned with the study’s aim to measure student attitudes about the ethics modules. The first analysis measured differences between perceived usefulness of the modules to determine if students found one teaching modality more useful than the others. The second was a qualitative study on written student feedback.

The statistical analysis of perceived usefulness was performed with the python programming language using the pandas, statsmodels, scipy, and scikit_posthocs packages. Descriptive statistics were calculated for each analysis with reported averages following the format of the mean ± one standard deviation. Group differences between the Likert-based usefulness ratings were initially analyzed with an ANOVA and normalcy of the standardized residuals were computed with a Shapiro-Wilk test. The final analysis used a Kruskal-Wallis test and post-hoc Dunn test with a Bonferroni correction to determine differences between groups (corrected- α for all tests was set to 0.05).

Student feedback was analyzed using two different qualitative approaches: constant comparison analysis [ 30 ] and classical content analysis [ 31 ]. Using more than one approach in qualitative data analysis, as recommended by Leech and Onwuegbuzie [ 32 ], can increase interpretive validity, or the degree to which the perspectives of students are accurately rendered by the researcher [ 33 ]. Two of the investigators (YZ and KO) double coded the de-identified student feedback with Dedoose 8.3.47b to independently assign codes to the text for each module. The investigators then reviewed the accuracy and relevance of these codes according to their interpretation of the students’ meaning and used the software to merge similar codes and remove other codes that were no longer pertinent. Next, the investigators used printouts from the software to complete axial coding, which involves comparing text segments and codes to create categories made up of similar codes, and to combine categories into broad themes. Last, the investigators used printouts from the software to conduct classical content analysis, calculating percentages of codes associated with each theme to determine their relative significance to the participants. The premise underlying classical content analysis is that the frequency of occurrence is connected to the meaning of the content [ 31 ]. This analysis allowed the investigators to discover the relative importance that each theme held for students (i.e., based upon the frequency of the codes associated with each theme), which gave more insight into students’ responses. The data were entered into Microsoft Excel for data management.

Ethical considerations

Exempt status for the research project was granted by the IRB committee of SHSU.

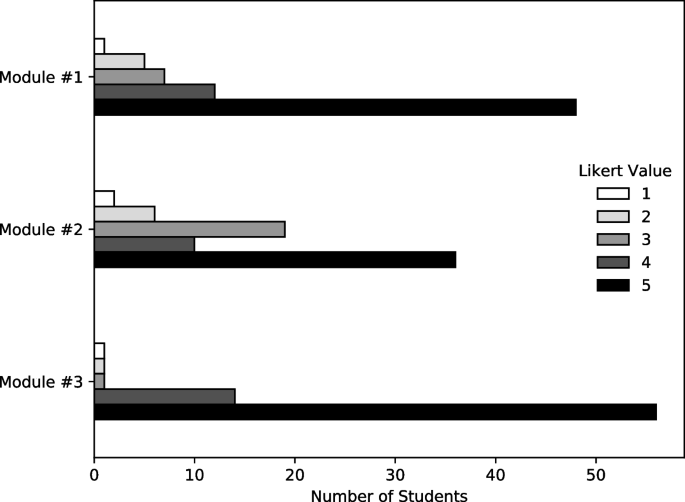

The majority of students (73/74) completed the Likert-based usefulness ratings. In general, students found each module useful, with an average across all modules of 4.37 ± 0.99. Descriptive statistics for each module are reported in Table 2 and the distribution of answers are shown in Fig. 1 .

Usefulness ratings for each ethics learning module

To test differences between the Likert-based usefulness ratings between modules, a one-way ANOVA was performed with modules as groups and Likert-results as the dependent variable. However, it was found that the standardized residuals of the ANOVA did not follow a normal distribution after testing with a Shapiro-Wilk test ( W = 0.84, p < 0.001). Due to non-normal standardized residuals, a Kruskal-Wallis test was employed and found a statistically significant difference in rank-order between treatments ( H = 16.2, p < 0.001). A post-hoc Dunn test with a Bonferroni correction found that the only treatment pair with a statistically significant difference (corrected- α < 0.05) was between Module #3 and Module #2 (corrected p < 0.001). Complete results from the post-hoc Dunn test are reported in Table 3 .

The number of narrative responses to the perception question was consistently high, but not complete, with 82% of students who completed Module #1 providing feedback, with 85% for Module #2 and 80% for Module #3. Constant comparison analysis of student perception of the learning modules reveals three themes. These include general favorable impression for the learning modules , perceived learning outcomes for the learning module , and suggestions and critiques from students (Table 4 ).

General favorable impression of students for the learning modules

Students’ overall impression of the ethics learning modules integrated in a biomedical science course was positive. Based on classical content analysis (Table 4 ), the student’s general impression theme contains the highest percentage of codes, suggesting it is the most relevant theme from students’ perceptive responses. A detailed breakdown of common and unique codes for this theme is presented in Table 5 .

Engaging and enjoyable is the most dominant code in this theme with more comments from Module #1 (documentary) and Module #3 (SGD/Debate). In addition, several students described participating in Module #3 as “ fun ”.

“It was very interesting to learn about ethics this way and certainly something that I will not forget for a very long time.” (Module #1)

“Everyone in my group was excited to participate and contribute thought. I loved this.” (Module #3)

According to students, all the modules were considered effective and useful, thought provoking, and provided opportunities for them to examine ethical challenges and different perspectives which promoted their critical thinking. Most of the relevant comments associated with these codes were from Module #3, seconded by Module #2 and then Module #1.

“If I had watched the documentary on my own, I probably would not have thought about it as deeply as I did for this activity” (Module #1)

“ … the questions challenge me to think from different perspectives and consider multiples factors.” (Module #2)

“The debate made me think of the case on a deeper level and truly analyze each argument.” (Module #3)

Unique codes were also identified for Modules #1 and #3. For Module #1, students commented that watching the documentary helped them to see different viewpoints and it is more effective than traditional teaching styles such as reading text. For Module #3, the students described the debate as stress free but challenging and highlighted that it provided the opportunity to present and view different perspectives which ultimately allowed them to learn from each other. It was well perceived by students as a favorable format of teaching ethics.

“Thus, having these discussions are still very important, and sharing unique perspectives is great for that in two regards. One, these discussions teach us who others are and what others think about the world around them, and we must try our best to respect and understand these perspectives of others. Two, these discussions could reveal more about ourselves and even help us understand ourselves better, which allows us to develop our sense of uniqueness.” (Module #3)

Perceived learning outcome

Our analysis also revealed students’ perceived learning outcomes for each module. Several common and overlapping codes were identified as well as unique codes. (Table 6 ).

Many students felt that all the modules provided real world preparation and increased awareness of their roles as future physician. This code was the most dominant one compared to the other common codes. They felt that the modules helped them recognize the impact of ethical issues in clinical situations and made them think ahead as to how they might and should proceed in real-life circumstances.

“ … this is a very ethically engaging case and an issue that we will likely come across in our careers.” (Module #1)

“Really challenging situations like this do happen in real life and we need to have the skills to navigate through these situations and do what is best for the patient and their life.” (Module #3)

Students also described that the modules helped them raise awareness of the complexity of ethics by seeing the difficulty of ethics and how sometimes there is not a clear-cut answer as to what to do in a situation . In addition, the integration of ethics learning in biomedical science course helped them build connection of ethics with science. The classroom activities encouraged the application of biomedical knowledge learned in the course.

“I found this module to be useful in terms of utilizing all that we have learned so far to understand HIV from a different lens than previously thought.” (Module #2)

“I really like seeing the ethical side of the science that we are learning. It is easy to get so focused in the science and technology that it is nice to take a step back and think of the human perspective of it.” (Module #3)

The unique codes for the perceived learning outcomes were consistent with the distinct ethical challenges that were highlighted in each module. In Module #1, several students felt it improved awareness of the connection of ethics and research as well as recognizing the importance of a research compliance body oversight. Students felt this module helped them understand the role of ethics within the larger health care system. One student commented:

“My value of the scientific community and of institutional review boards has now increased as I believe that they could have helped improve the situation David and his family were facing if they intervened appropriately. ” (Module #1)

In Module #2, many students felt it raised awareness of the interplay between ethics and law, made them consider the legal rights versus the patients’ rights when it comes down to certain situations as physician.In Module #3, students identified increased awareness of the complexity of patient care as well and of the role of religion in health care. They also felt this highlighted the importance of patient-centered care.

“ … physicians must not just deal with symptoms but also the social aspects and ethical principles when addressing a patient’s care. Education, personal experience, stress, and religious beliefs are a few of the variables that differ amongst individuals and increase the complexity of a patient case. ” (Module #3)

Student critiques and suggestions

Some students commented on the fact that addition of group discussion would have been preferred and more effective in both Module #1 and #2. In Module #1, some wished for more structured instruction along with concrete objectives and didactic information . In Module #2, some students felt that the case was hypothetical and lacked background information. As one student commented “ It would be more useful knowing more about the state laws and regulations surrounding this kind of diagnosis.” Adding more context to the case and providing relevant learning materials would allow for more insightful discussion to the suggested way to approach difficult scenarios for us as future physicians . In Module #3, one student felt they needed more time to consider the ethical challenges as it was a harder ethics choice .

Although the goal is for students to explore and identify ethical challenges on their own, one student commented the Module #1 is not instructional in pointing out ethical issues/errors in the video as they happen. A detailed breakdown of common and unique codes for this theme is presented in Table 7 .

Given the importance of ethics in medical education, we created an innovative curriculum design for ethics learning made up of three unique modules that were integrated into a biomedical science course in the first-year pre-clinical curriculum. We started this project with the overall aim to increase student awareness and understanding of the ethical dimensions of the biomedical sciences. The literature on interleaving would suggest that students who learn medical ethics within a biomedical science context will improve their learning of both the foundational science content and the medical ethics content [ 34 ], for by exercising different forms of reasoning – scientific reasoning and ethical reasoning – within the same course, students may increase their ability to retain and apply the content learned, at least as compared to massed learning [ 35 ]. Literature is limited regarding strategies to integrate ethics in biomedical science courses [ 35 ]. Ultimately, we believe that a curricular design like the one that we developed can help medical students build connections between science, human disease and ethics, but our first step for this project was to see how students would react to this novel course design by evaluating their attitudes.

The design of our ethics modules was heavily influenced by the mounting evidence suggesting that students learn better and retain information longer when they learn through multiple modalities [ 35 ]. Several educational modalities have been shown to be effective in the teaching and learning of ethics in medical education. Examples include the use of ethical dilemmas in integrated small group sessions, standardized patients, team-based approaches, case-based discussion, problem-based methods, student-driven curriculum, peer-based teaching and ethics guest lectures [ 4 , 10 , 13 , 20 , 36 , 37 ]. These teaching modalities additionally provide opportunities for active learning which can increase student engagement and retention of information [ 35 ].

With this in mind, our modules were created utilizing different modalities to allow for maximal engagement and connection with the content. The particular choice of active learning strategy for each module was made by considering the content and the availability of course schedule along with the instructors’ content expertise. All three modules generated a consensus regarding the effectiveness and benefits of this curriculum design of ethics education in improving understanding and future preparation for encountering real dilemmas in medical practice. While all modules were considered to be engaging and thought-provoking, student responses highlighted various perceived strengths and weaknesses of each unique module and pedagogical modality. Module #1 was delivered through an asynchronous module using a commercially available documentary without formalized discussion. While the design of the documentary module did not allow for collaboration between the students or didactic instruction, choosing media with an existing reputation for engaging audiences made it more likely that the students would have at least a base-level interest in the module. Interactive learning strategies such as using the documentary as a basis for an interrupted case study could be utilized in the future to enhance the engagement. Module #2 was presented in a case-based fashion and without group discussion. A perceived weakness of this module was the lack of detailed background information in comparison to Module #1 which is a well-publicized case with robust details. Since the module was embedded in a TBL case that was focused on the scientific foundations of HIV, students felt it helped them strengthen their understanding of the ethical dimensions of the science they learned. Module #3 allowed for both small and large group discussion while incorporating a debate format which prompted rich discussion.

Although all modules were considered useful, student responses indicated a strong preference for Module #3, with a statistical significance when compared to Module #2, but not Module #1. There were more unique codes and comments generated related to its complexity and challenging format. This could be because the debate allowed students the uninterrupted opportunity to voice an opinion regarding the many ethical dilemmas central to the case being examined. Further, students enjoyed learning about their classmates and hearing new viewpoints from colleagues. Students were assigned a side to defend which compelled some students to make arguments different from their own perspective. Our finding resonates with existing literature which has suggested that the use of debates can be an effective tool for teaching medical ethics because it increases students’ critical thinking expression and tolerance toward ambiguity [ 38 ]. In addition, the reflective writing time was integrated into the session module which encouraged more valuable, thorough, and accurate feedback. Another reason students may have reported a preference for Module #3 could be that it was the last module of the course and close to the completion of the course. Overall, these elements highlighted the benefit of a debate format to encourage discussion of difficult topics emphasized in ethics courses, which contributed to the preference of Module #3. Interestingly, only one participant mentioned the link between ethics and science for Module #3, this might be due to the timing and method of the science session delivery. The session “Blood Transfusion” was offered asynchronously at the beginning of the week, while Module #3 was delivered at the end of the week due to scheduling conflict. This suggests the importance of purposeful design, delivery, and sequencing of both science and ethics sessions to help students better recognize the connection between the two subjects.

Our study has several limitations that affect the reliability and validity of the study. Although students were provided opportunities to practice ethical reasoning and decision making through providing explanation for self-identified ethical challenges and reflective writing, the direct learning outcome was not assessed. The lack of baseline data has hindered the analysis on the gain of students’ knowledge and attitude, although as a whole they perceived the modules as valuable and beneficial. Future studies should include pre- and post-assessment and longitudinal evaluation of the growth of the knowledge and moral attitudes of students. We also do not know whether students’ usefulness ratings were based on their preference for learning modalities or their specific interest in the topic of the module. For future studies the usefulness question should be revised to remove this ambiguity and improve content validity. The students were also not asked to directly compare the modules. Instead, they gave their responses at the time they completed each module, which was weeks apart from one another. Their general opinion may have changed over time and the order in which the modules were delivered may have influenced their responses. The modules could also be expanded to include multiple classes and to incorporate the modules in multiple courses. Furthermore, backward design strategy could be incorporated to ensure achievement of ethics learning objectives. The long-term impact of the modules may be evaluated by using preceptors survey in clerkship.

Expanding the study, and ethics education in general, faces several obstacles. Perhaps the most challenging obstacles are mundane: the lack of time within curriculum, lack of time in faculty schedules, and the lack of teachers qualified to teach ethics in the context of medical education [ 10 ]. Our study shows that ethics may be integrated in non-traditional places in curriculum and that student-directed learning can be used to alleviate the burden of curriculum load, although more student interaction should be encouraged. We plan to develop pre- and post-testing along with additional modules in order to measure longitudinal learning and to further integrate ethics into our biomedical science curriculum. To address the lack of standardized ethics training or certification for the instructors some institutions may face, collaborating with ethicists through interdepartmental or interinstitutional effort may be helpful. Together, the team can develop the modules as well as provide narrative feedback to students, which may enhance the delivery and assessment of the ethics modules.

Our study demonstrates that ethics education can be integrated with biomedical sciences. As is universal in education, the pedagogical design of the curriculum and relevant activities is the key to gaining students’ interest in learning. Strategies for ethics learning that we noted include the importance of purposeful design and sequence as well as the use of active learning modalities that involve discussion such as debate. Our model can shed light on an innovative way of integrating ethics education into medical education.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Veatch RM. Medical Ethics: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 1997. (Jones and Bartlett series in philosophy). Available from: https://books.google.com/books?id=UCOT4sj-DwUC

Google Scholar

Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of biomedical ethics. 7th ed: Oxford University Press; 2013.

Vaugh L. Bioethics: principles, issues, and cases. 4th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2020.

Miles SH, Lane LW, Bickel J, Walker RM, Cassel CK. Medical ethics education: coming of age. Acad Med. 1989;64(12):705–14.

Article Google Scholar

Savulescu J, Crisp R, Fulford KWM, Hope T. Evaluating ethics competence in medical education. J Med Ethics. 1999;25(5):367–74.

Curriculum Topics in Required and Elective Courses at Medical School Programs. AAMC. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/curriculum-reports/interactive-data/curriculum-topics-required-and-elective-courses-medical-school-programs . Accessed 29 Nov 2022.

2017-18 Osteopathic Medical College Curriculum Topics. AACOM. https://www.aacom.org/reports-programs-initiatives/aacom-reports/curriculum . Accessed 29 Nov 2022.

DeFoor MT, Chung Y, Zadinsky JK, Dowling J, Sams RW. An interprofessional cohort analysis of student interest in medical ethics education: a survey-based quantitative study. BMC Med Ethics. 2020;21:26.

AlMahmoud T, Hashim MJ, Elzubeir MA, Branicki F. Ethics teaching in a medical education environment: preferences for diversity of learning and assessment methods. Med Educ Online. 2017;22(1):1328257.

Soleymani Lehmann L, Kasoff WS, Koch P, Federman DD. A survey of medical ethics education at U.S. and Canadian medical schools. Acad Med. 2004;79(7):682–9.

DuBois JM, Burkemper J. Ethics education in U.S. medical schools: a study of syllabi. Acad Med. 2002;77(5):432–7.

Shamim M, Baig L, Zubairi N, Torda A. Review of ethics teaching in undergraduate medical education. J Pak Med Assoc. 2019;70(6):1056–62.

de la Garza S, Phuoc V, Throneberry S, Blumenthal-Barby J, McCullough L, Coverdale J. Teaching medical ethics in graduate and undergraduate medical education: a systematic review of effectiveness. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(4):520–5.

Giubilini A, Milnes S, Savulescu J. The medical ethics curriculum in medical schools: present and future. J Clin Ethics. 2016;27(2):129–45.

Goldie J. Review of ethics curricula in undergraduate medical education. Med Educ. 2000;34:108–19.

Aguilera ML, Martínez Siekavizza S, Barchi F. A practical approach to clinical ethics education for undergraduate medical students: a case study from Guatemala. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2019;6:238212051986920.

Beigy M, Pishgahi G, Moghaddas F, Maghbouli N, Shirbache K, Asghari F, et al. Students’ medical ethics rounds: a combinatorial program for medical ethics education. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2016;9:3.

Liu EY, Batten JN, Merrell SB, Shafer A. The long-term impact of a comprehensive scholarly concentration program in biomedical ethics and medical humanities. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):204.

Chung EK, Rhee JA, Baik YH, A OS. The effect of team-based learning in medical ethics education. Med Teach. 2009;31(11):1013–7.

Hindmarch T, Allikmets S, Knights F. A narrative review of undergraduate peer-based healthcare ethics teaching. Int J Med Educ. 2015;6:184–90.

Donaldson TM, Fistein E, Dunn M. Case-based seminars in medical ethics education: how medical students define and discuss moral problems. J Med Ethics. 2010;36(12):816–20.

Wolpe PR. Reasons scientists avoid thinking about ethics. Cell. 2006;125(6):1023–5.

Mcgowan A. Teaching science and ethics to undergraduates: a multidisciplinary approach. Sci Eng Ethics. 2013;19(2):535–43.

Reese AJ. An undergraduate elective course that introduces topics of diversity, equity, and inclusion into discussions of science. J Microbiol Biol Educ. 2020;21(1):21.1.10.

Mann MK. The right place and the right time: incorporating ethics into the undergraduate biochemistry curriculum. In: Kloepper KD, Crawford GL, editors. ACS symposium series. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; 2017. p. 45–70. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/bk-2017-1266.ch004 . [Cited 2022 Jul 19].

Smith K, Wueste D, Frugoli J. Using “ethics labs” to set a framework for ethical discussion in an undergraduate science course. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2007;35(5):332–6.

Cornwall J, Hildebrandt S. Anatomy, education, and ethics in a changing world. Anat Sci Educ. 2019;12(4):329–31.

Carrese JA, Malek J, Watson K, Lehmann LS, Green MJ, McCullough LB, et al. The essential role of medical ethics education in achieving professionalism: the Romanell report. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):744–52.

The boy in the bubble. Public Broadcasting Service (PBS); 2006.

Glaser B. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Soc Probl. 1965;12(4):436–45.

Berelson B. Content analysis in communication research. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 1952;283(1):197–8.

Leech NL, Onwuegbuzie AJ. An array of qualitative data analysis tools: a call for data analysis triangulation. Sch Psychol Q. 2007;22(4):557–84.

Maxwell JA. Understanding and validity in qualitative research. In: The qualitative Researcher’s companion. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2022. Available from: https://methods.sagepub.com/book/the-qualitative-researchers-companion .

Safuan S, Ali S, Kuan G, Long I, Nik N. The challenges of bioethics teaching to mixed-ability classes of health sciences students. Educ Med J. 2017;9:41–9.

Brown PC. Make it stick : the science of successful learning. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, [2014]; 2014. Available from: https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/9910195454802121

Book Google Scholar

Mattick K. Teaching and assessing medical ethics: where are we now? J Med Ethics. 2006;32(3):181–5.

Sullivan BT, DeFoor MT, Hwang B, Flowers WJ, Strong W. A novel peer-directed curriculum to enhance medical ethics training for medical students: a single-institution experience. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:2382120519899148.

Amar-Gavrilman N, Bentwich ME. To debate or not to debate? Examining the contribution of debating when studying medical ethics in small groups. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):114.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Amber Sechelski for her recommendations on the qualitative analysis.

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Primary Care and Clinical Medicine, College of Osteopathic Medicine, Sam Houston State University, Conroe, USA

Oluwaseun Olaiya

College of Osteopathic Medicine, Sam Houston State University, Conroe, USA

Travis Hyatt, Alwyn Mathew & Shawn Staudaher

Department of Psychology and Philosophy, College of Humanities and Social Sciences, Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, USA

Zachary Bachman

Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, College of Osteopathic Medicine, Sam Houston State University, Conroe, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

YZ and OO designed the study and delivered all learning modules. They collected the data and conducted the qualitative data analysis and were major contributors in writing the manuscript. TH and AM conducted the literature review and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. SS conducted the quantitative data analysis and contributed to the editing of the manuscript. ZB contributed to the editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Yuan Zhao .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Decision of exempt status for this research project was granted by the IRB committee of Sam Houston State University. Informed consent was exempted by the IRB committee of Sam Houston State University due to retrospective nature of the study. All methods were carried out in accordance with the principles, guidelines and regulations of Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1..

Appendix 1. List of Ethical Challenges Cited from the Romanell Report.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Olaiya, O., Hyatt, T., Mathew, A. et al. Building connections between biomedical sciences and ethics for medical students. BMC Med Educ 22 , 829 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03865-y

Download citation

Received : 27 July 2022

Accepted : 04 November 2022

Published : 01 December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03865-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Medical ethics

- Medical education

- Curriculum development

- Biomedical science

BMC Medical Education

ISSN: 1472-6920

- General enquiries: [email protected]

To Determine the Effectiveness of Current Ethical Teachings in Medical Students and Ways to Reform this Aspect

- Published: 20 August 2024

Cite this article

- Rida Saleem ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1126-2773 1 ,

- Syeda Zainab Fatima ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8606-5854 1 ,

- Roha Shafaut ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6857-2943 1 ,

- Asifa Maqbool 1 ,

- Faiza Zakaria ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1067-264X 1 ,

- Saba Zaheer ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5911-581X 1 ,

- Musfirah Danyal Barry ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4236-3462 1 ,

- Haris Jawaid ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1879-4139 1 &

- Dr. Fauzia Imtiaz 1

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

To determine the effectiveness of current ethical teaching and to suggest ways to reform the current ethical curriculum in light of students’ perspectives and experiences. Students of Dow Medical College were selected for this cross-sectional study conducted between the year 2020 till 2023. The sample size was 387, calculated by OpenEpi. A questionnaire consisting of 17 close-ended questions was used to collect data from participants selected via stratified random sampling. The questionnaire consisted of two parts. The first part included the demographics. While the second contained 15 questions designed to assess the participants’ current teaching of ethics and effective ways to further improve it. The data obtained were analyzed using IBM SPSS statistics 26. Out of the 376 students who gave consent, the majority of the respondents (64.6%) encountered situations where they felt that their current teaching of ethics was insufficient and (54%) believed that the current teaching of ethics could be improved and made further effective. Practical sessions, PBLs (problem-based learning), case analysis, and ward visits were some of the ways the participants believed could help improve the teaching of medical ethics. Most students (92.8%) agreed that external factors like burnout and excessive workload have an impact on medical professionals’ ethical practices. In light of our study, a refined curriculum with a focus on ethical teaching must be established, with input from students to ensure that the medical students have the necessary expertise to manage an ethical dilemma.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

What Do Students Perceive as Ethical Problems? A Comparative Study of Dutch and Indonesian Medical Students in Clinical Training

Must we remain blind to undergraduate medical ethics education in africa a cross-sectional study of nigerian medical students.

The state of ethics education at medical schools in Turkey: taking stock and looking forward

Explore related subjects.

- Medical Ethics

- Artificial Intelligence

Data Availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

Aleem, I., Zaidi, TafazzulHyder, Usman, G., Siddiq, H., Usman, T., Baloch, Z. H., & Abbas, K. (2021). Practice of medical ethics among house officers at tertiary care hospital in karachi. Pakistan Journal of Neurological Sciences (PJNS), 16 (3), 3.

Google Scholar

Althobaiti, M. H., Alkhaldi, L. H., Alotaibi, W. D., Alshreef, M. N., Alkhaldi, A. H., Alshreef, N. F., Alzahrani, N. N., & Atalla, A. A. (2021). Knowledge, attitude, and practice of medical ethics among health practitioners in Taif government, KSA. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 10 (4), 1759–1765. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_2212_20

Article Google Scholar

Chen, D., Lew, R., Hershman, W., & Orlander, J. (2007). A cross-sectional measurement of medical student empathy. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22 (10), 1434–1438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0298-x

Chen, D. C., Kirshenbaum, D. S., Yan, J., Kirshenbaum, E., & Aseltine, R. H. (2012). Characterizing changes in student empathy throughout medical school. Medical Teacher, 34 (4), 305–311. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.644600

Cho, D., Cosimini, M., & Espinoza, J. (2017). Podcasting in medical education: A review of the literature. Korean Journal of Medical Education, 29 (4), 229–239. https://doi.org/10.3946/kjme.2017.69

Gabel, S. (2011). Ethics and values in clinical practice: whom do they help? Mayo Clinic proceedings, 86 (5), 421–424. https://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2010.0781

Jafarey, A. M. (2003). Bioethics and medical education. Journal of Pakistan Medical Association, 53 (6), 210–214.

Kelly, J. M., Perseghin, A., Dow, A. W., Trivedi, S. P., Rodman, A., & Berk, J. (2022). Learning through listening: a scoping review of podcast use in medical education. Academic Medicine : Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 97 (7), 1079–1085. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000004565

Martins, V., Santos, C., Bataglia, P., & Duarte, I. (2021). The teaching of ethics and the moral competence of medical and nursing students. Health Care Analysis: HCA: Journal of Health Philosophy and Policy, 29 (2), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10728-020-00401-1

Nandi, P. L. (2000). Ethical aspects of clinical practice. Archives of surgery (Chicago, Ill. : 1960), 135 (1), 22–25. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.135.1.22

Ozgonul, L., & Alimoglu, M. K. (2019). Comparison of lecture and team-based learning in medical ethics education. Nursing Ethics, 26 (3), 903–913. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733017731916

Ridd, M., Shaw, A., Lewis, G., & Salisbury, C. (2009). The patient-doctor relationship: A synthesis of the qualitative literature on patients’ perspectives. The British Journal of General Practice: THe Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 59 (561), e116–e133. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp09X420248

Roberts, L. W., Warner, T. D., Hammond, K. A., Geppert, C. M., & Heinrich, T. (2005). Becoming a good doctor: Perceived need for ethics training focused on practical and professional development topics. Academic Psychiatry : THe Journal of the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training and the Association for Academic Psychiatry, 29 (3), 301–309. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ap.29.3.301

Ruberton, P. M., Huynh, H. P., Miller, T. A., Kruse, E., Chancellor, J., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2016). The relationship between physician humility, physician-patient communication, and patient health. Patient Education and Counseling, 99 (7), 1138–1145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.01.012

Silverman, H. J., Dagenais, J., Gordon-Lipkin, E., Caputo, L., Christian, M. W., Maidment, B. W., 3rd., Binstock, A., Oyalowo, A., & Moni, M. (2013). Perceived comfort level of medical students and residents in handling clinical ethics issues. Journal of Medical Ethics, 39 (1), 55–58.

Stratta, E. C., Riding, D. M., & Baker, P. (2016). Ethical erosion in newly qualified doctors: Perceptions of empathy decline. International Journal of Medical Education, 7 , 286–292. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.57b8.48e4

Syed, S. S., John, A., & Hussain, S. (1996). Attitudes and perceptions of current ethical practices . PakIstan Journal of Medical Ethics, 1 , 5–6.

Download references

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Dow University of Health Sciences, Baba-E-Urdu Road, Karachi 74200, Pakistan

Rida Saleem, Syeda Zainab Fatima, Roha Shafaut, Asifa Maqbool, Faiza Zakaria, Saba Zaheer, Musfirah Danyal Barry, Haris Jawaid & Dr. Fauzia Imtiaz

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All the authors took an equal part in performing the literature search, drafting the questionnaire, and the data collection of this study. Rida Saleem, Syeda Zainab Fatima, Roha Shafaut, Asfa Maqbool, and Faiza Zakaria drafted the initial manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript. Saba Zaheer and Musfirah Danyal Barry contributed to the editing and revisions of the initial and subsequent drafts for incorporating important intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript. Haris Jawaid played an essential role in the data analysis and formulation of the results of this study. This study was completed under the supervision and guidance of Dr. Fauzia Imtiaz. She contributed to getting the IRB approval from DUHS- Research Committee. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Syeda Zainab Fatima .

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval.

Approval to conduct this study was obtained from Ethics Committee of the institutional review board (IRB), (Authors will indicate the name of the granting institution after the acceptance of the manuscript).

Competing Interest

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Saleem, R., Fatima, S.Z., Shafaut, R. et al. To Determine the Effectiveness of Current Ethical Teachings in Medical Students and Ways to Reform this Aspect. J Acad Ethics (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-024-09550-7

Download citation

Accepted : 11 July 2024

Published : 20 August 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-024-09550-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Medical Education

- Malpractices

- Medical Students

- Government Sector

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Subscribe to journal Subscribe

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

The Essential Role of Medical Ethics Education in Achieving Professionalism

The romanell report.

Carrese, Joseph A. MD, MPH; Malek, Janet PhD; Watson, Katie JD; Lehmann, Lisa Soleymani MD, PhD; Green, Michael J. MD, MS; McCullough, Laurence B. PhD; Geller, Gail ScD, MHS; Braddock, Clarence H. III MD, MPH; Doukas, David J. MD

J.A. Carrese is professor, Division of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and core faculty, Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

J. Malek is associate professor, Department of Bioethics and Interdisciplinary Studies, Brody School of Medicine, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina.

K. Watson is assistant professor, Medical Humanities and Bioethics Program, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois.

L.S. Lehmann is associate professor, Center for Bioethics, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Division of Medical Ethics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.

M.J. Green is professor, Department of Humanities and Department of Medicine, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania.

L.B. McCullough is professor and Dalton Tomlin Chair in Medical Ethics and Health Policy, Center for Medical Ethics and Health Policy, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas.

G. Geller is professor, Division of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and core faculty, Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

C.H. Braddock III is professor and vice dean for education, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, California.

D.J. Doukas is William Ray Moore Endowed Chair of Family Medicine and Medical Humanism and director, Division of Medical Humanism and Ethics, Department of Family and Geriatric Medicine, University of Louisville School of Medicine, Louisville, Kentucky.

Funding/Support: The Project to Rebalance and Integrate Medical Education was supported by the Patrick and Edna Romanell Fund for Bioethics Pedagogy of the University of Buffalo.

Other disclosures: J.A. Carrese, D.J. Doukas, M.J. Green, and J. Malek hold leadership roles in the Academy for Professionalism in Health Care (APHC). At the time of writing, C.H. Braddock and L.S. Lehmann also held APHC leadership roles.

Ethical approval: Reported as not applicable.

Disclaimers: The views expressed by the authors reflect their personal perspectives and do not necessarily reflect those of the APHC.

Correspondence should be addressed to Joseph A. Carrese, Division of General Internal Medicine, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, 5200 Eastern Ave., Mason F. Lord Building, Center Tower, Suite 2300, Baltimore, MD 21224; telephone: (410) 550-2247; e-mail: [email protected] .

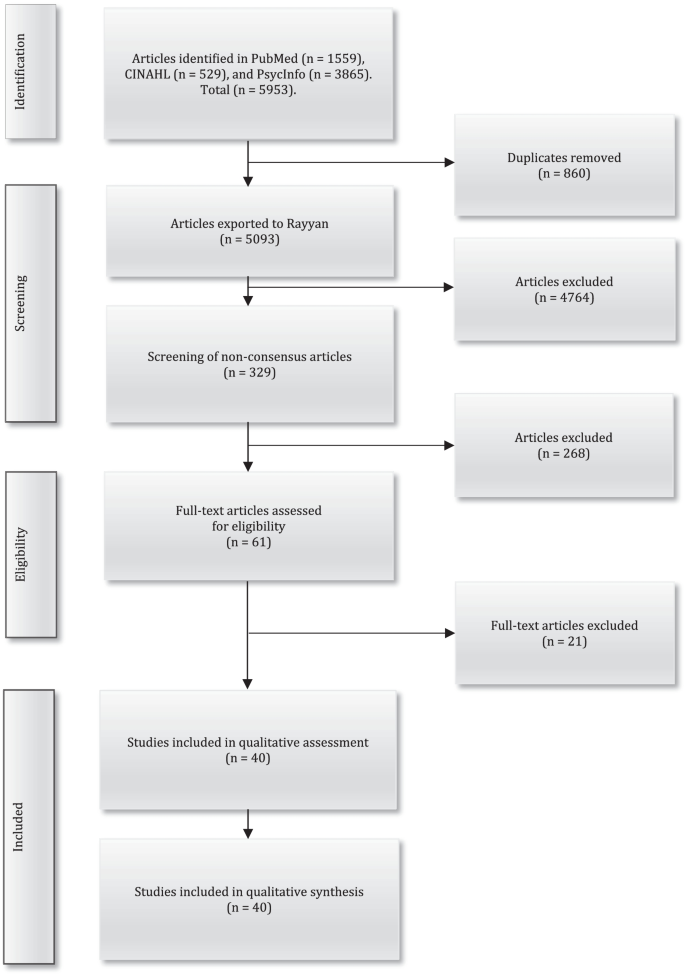

This article—the Romanell Report—offers an analysis of the current state of medical ethics education in the United States, focusing in particular on its essential role in cultivating professionalism among medical learners. Education in ethics has become an integral part of medical education and training over the past three decades and has received particular attention in recent years because of the increasing emphasis placed on professional formation by accrediting bodies such as the Liaison Committee on Medical Education and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Yet, despite the development of standards, milestones, and competencies related to professionalism, there is no consensus about the specific goals of medical ethics education, the essential knowledge and skills expected of learners, the best pedagogical methods and processes for implementation, and optimal strategies for assessment. Moreover, the quality, extent, and focus of medical ethics instruction vary, particularly at the graduate medical education level. Although variation in methods of instruction and assessment may be appropriate, ultimately medical ethics education must address the overarching articulated expectations of the major accrediting organizations. With the aim of aiding medical ethics educators in meeting these expectations, the Romanell Report describes current practices in ethics education and offers guidance in several areas: educational goals and objectives, teaching methods, assessment strategies, and other challenges and opportunities (including course structure and faculty development). The report concludes by proposing an agenda for future research.

In 1985, the landmark article “Basic Curricular Goals in Medical Ethics,” known as the DeCamp Report, argued that basic instruction in medical ethics should be a requirement in all U.S. medical schools. 1 That same year, the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) introduced standards stipulating that in U.S. medical schools “ethical, behavioral, and socioeconomic subjects pertinent to medicine must be included in the curriculum and that material on medical ethics and human values should be presented.” 2 More recently, medical educators and accrediting organizations have expanded the scope of ethics education guidelines, manifested in part by requirements that learners at all levels receive instruction addressing professional formation to prepare them for a lifelong commitment to professionalism in patient care, education, and research. 3 A physician’s ability and willingness to act in accordance with accepted moral norms and values is one key component of professional behavior; as a result, educational objectives relating to ethics are now often incorporated into broader goals for professionalism education.

Despite broad consensus on the importance of teaching medical ethics and professionalism, there is no consensus about the specific goals of medical ethics education for future physicians, the essential knowledge and skills learners should acquire, the best methodologies and processes for instruction, and the optimal strategies for assessment. 4–8 Moreover, the quality and extent of instruction, particularly at the graduate medical education (GME) level, varies within and across institutions and residency training programs. 9–11 Although such variation may be appropriate in light of differences in educational contexts, medical ethics education efforts must ultimately address the overarching expectations articulated by accrediting organizations. Variation raises concerns about whether all approaches succeed in meeting basic educational objectives, which leads to the question, “Which approaches to medical ethics education are most effective?”

This article, the Romanell Report, is a product of the Project to Rebalance and Integrate Medical Education (PRIME), funded by the Patrick and Edna Romanell Fund for Bioethics Pedagogy. PRIME was a national working group that focused on medical ethics and humanities education as they relate to professionalism education in medical school and residency training. 12 , 13 PRIME led to the founding of the Academy for Professionalism in Health Care as an organization devoted to professionalism education. 14

As members of PRIME with a particular interest in medical ethics education, we address in this report the essential role of such education in cultivating professionalism among medical learners. We previously described medical professionalism as (1) becoming scientifically and clinically competent; (2) using clinical knowledge and skills primarily for the protection and promotion of the patient’s health-related interests, keeping self-interest systematically secondary; and (3) sustaining medicine as a public trust, rather than as a guild primarily concerned with protecting the economic, political, and social power of its members. 13

We take our working definition of “medical ethics” from a prominent textbook on clinical ethics: “Clinical ethics concerns both the ethical features that are present in every clinical encounter and the ethical problems that occasionally occur in those encounters.” 15 In addition, we consider medical ethics to include attention to determining what ought to be done when problems or values conflicts are present: that is, determining the right course of action or a morally acceptable choice from among the available options.

We consider it self-evident that there is a close relationship between medical ethics and professionalism and that the extensive body of scholarship on medical ethics informs how we think about professionalism. However, a thorough analysis of this relationship is beyond the scope of this article. We do not address the important role of humanities education in the pursuit of professional formation in this report; we plan to focus on that in future work. Additionally, although our focus in this article is on medical ethics education during medical school and residency training, we acknowledge that the educational continuum extends on either side of this focus. We believe that medical ethics and professionalism should also be made a priority during premedical studies and reinforced post residency through continuing medical education (CME).

In this report, with the aim of aiding medical ethics educators in meeting the articulated expectations of accrediting organizations, we address the following aspects of medical ethics education in medical schools and residency programs: goals and objectives, teaching methods, assessment strategies, and additional challenges and opportunities. We conclude by recommending next steps and areas for future study.

Goals and Objectives

Although most educators agree that the central goal of medical ethics education is to promote excellence in patient care, there are diverse views about how best to achieve this aim. 4 Whereas some educators emphasize the importance of developing future physicians’ character, others hold that shaping their behavior is a more appropriate focus. Still others believe that ethics and professionalism cannot be taught; rather, virtuous individuals must be selected through the medical school admission process. The debate among proponents of these schools of thought is unlikely to be resolved in the near future.

Although medical schools should seek to select students with the “right” character and attitudes, those qualities are difficult to assess accurately. Further, effecting character change in the limited time available for medical ethics and professionalism education seems challenging at best. The practical challenges of shaping and evaluating character traits logically lead to the alternative: cultivating behavior that exemplifies ethical and professional virtues. The foundation of this approach is to provide trainees with conceptual tools for seeing, preventing, analyzing, and resolving the ethical dilemmas encountered in clinical medicine. Although an argument can be made that this pragmatic approach is not ideal, it is a workable compromise that may be the best available option given existing constraints.

This focus on behavioral goals is supported by the major accrediting bodies for U.S. medical schools and residency programs, which have established behavior-based standards and competencies that learners must achieve during training. For example, LCME standard ED-23 states: “A medical education program must include instruction in medical ethics and human values and require its medical students to exhibit scrupulous ethical principles in caring for patients and in relating to patients’ families and to others involved in patient care.” 16 The LCME specifies that students’ behavior must be observed and assessed to ensure that it is in line with accepted ethical guidelines.

Similarly, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has defined six core competencies 17 and has called for the development of milestones that establish benchmarks for the behaviors that physicians completing U.S. residency programs must demonstrate for each competency. One of the six core competencies specifically focuses on professionalism, stating, “Residents must demonstrate a commitment to carrying out professional responsibilities and an adherence to ethical principles.” Residents are expected to show compassion and respect for others, put patients’ needs above their own, respect patients’ autonomy, act accountably, and demonstrate sensitivity to patients from diverse backgrounds. The ACGME has left it to individual specialties to define the milestones that compose this core competency. As an example, the professionalism milestones identified by the American Board of Internal Medicine are presented in Table 1 . It should be noted that all six of the ACGME core competencies involve various aspects of professionalism, explicitly or implicitly.

With respect to the continuum of medical learning, there is interest in extending the focus on competencies and milestones beyond GME. Some educators suggest integrating them into undergraduate medical education (UME) as well as addressing them as part of CME and maintenance of certification. 18

In addition, attention has been directed at linking milestones to instances of actual clinical practice by defining entrustable professional activities (EPAs) and using them as a basis for assessing learner performance. 19 To successfully and independently perform one of these core clinical activities, learners must not only demonstrate the requisite knowledge, attitudes, and skills but also seamlessly integrate competencies, subcompetencies, and milestones. Some educators 18 have argued for tailoring EPAs to the learner’s developmental level, which could serve to further integrate the learning continuum.

EPAs, milestones, and competencies define where learners are expected to be by the end of their training, but they do not specify the detailed objectives that educators should use to lead them there. Among ethics educators, there is no consensus on a set of specific objectives for medical ethics education, although several lists of key skills and topics have been put forward. 20–22 Our attempt to synthesize current thought on a minimum set of objectives for medical ethics education is presented in List 1 . These objectives apply to both medical students and residents, with greater proficiency expected of higher-level trainees. This list was developed collaboratively by our group of experienced educators and draws on relevant empirical studies and other published literature. 4 , 6 , 9 , 20 , 21 , 23 It is important to emphasize that this list represents what we consider to be the basic requirements for medical ethics education. We acknowledge that other objectives to promote professionalism in learners (i.e., objectives incorporating other specific skills and topics) could be added to this list.

List 1 Proposed Objectives for Medical Ethics Education Cited Here

Upon completion of medical school or a residency training program, learners will, with an appropriate level of proficiency:

- Demonstrate an understanding of the concept of the physician as fiduciary and the historical development of medicine as a profession

- Recognize ethical issues that may arise in the course of patient care

- Utilize relevant ethics statements from professional associations to guide clinical ethical judgment and decision making

- Think critically and systematically through ethical problems using bioethical principles and other tools of ethical analysis

- Provide a reasoned account of professionally responsible management of ethical problems and act in accordance with those judgments

- Articulate ethical reasoning to others coherently and respectfully

Upon completion of medical school or a residency training program, learners will, with an appropriate level of proficiency, manage ethical challenges in a professional manner in the following areas:

- Protection of patient privacy and confidentiality

- Disclosure of information to patients, including medical errors and the delivery of bad news

- Assessment of patient decision-making capacity and issues related to surrogate decision making

- Shared decision making, including informed consent and informed refusal of medical interventions by patients

- Care at the end of life, including patient advance directives, withholding and withdrawing life-sustaining interventions, care for the dying, and determination of death

- Maternal–fetal medicine, including reproductive technologies and termination of pregnancy

- Pediatric and neonatal medicine

- Access to health care, including health care disparities, the health care system, and the allocation of scarce resources

- Cross-cultural communication, including cultural competency and humility

- Role of the health care professional’s personal values in the clinical encounter, including the extent and limits of the right of conscience

- Conflicts of interest and of obligation in education, clinical practice, and research

- Research with human subjects, including institutional review boards

- Work within the medical team, including interprofessional interactions

- Concerns about colleagues, including impairment, incompetence, and mistakes

- Medical trainee issues, including disclosure of student status, the tension between education and best care for patients, the hidden curriculum, and moral distress

- Self-awareness, including professional identity and self-care

- Management of challenging patients/family members, including recognition of what the clinician may be contributing to the difficulty

- Social media

- Religion and spirituality

- Acceptance of gifts from patients, including grateful patient philanthropy

For comparison, we have summarized the objectives for medical ethics education presented in the 1985 DeCamp Report 1 in List 2 . The objectives proposed in this report ( List 1 ) differ from the earlier objectives in several ways. First, our objectives are more comprehensive, which may reflect an increased emphasis on ethics and professionalism in medical training and therefore an expectation that more curricular time will be devoted to these topics. It may also reflect the broadening scope of the still-developing field of bioethics. A second difference between the objectives offered in the DeCamp and Romanell Reports is our inclusion of items that take into account the context in which medicine is practiced, particularly issues of access to health care and cultural competence. The inclusion of these items mirrors recent social trends—expanding awareness of socioeconomic inequalities, emphasizing the social determinants of health, and increasingly respecting and valuing diversity. Third, our expansion of ethical considerations beyond the patient–physician dyad to interprofessional interaction and self-care should be noted. An improved understanding of the important role of effective teams in preventing medical errors and in offering patients excellent care can explain our addition of an item on working within the medical team. The attention to self-care reflects a developing awareness that experiencing a loss of meaning in clinical practice and inadequate work–life balance can lead to waning commitment, dissatisfaction, and burnout, 24 and these in turn can be associated with lapses in professionalism. 25 , 26 Fourth, the DeCamp Report objectives emphasize moral reasoning and knowledge to be acquired in specific content areas, but devote less attention to specific skills to be developed. Our inclusion of more skills-based items in the Romanell Report objectives reflects accrediting agencies’ move toward evaluation of learners’ actual performance in clinical encounters and their achievement of corresponding milestones.

List 2 The DeCamp Report’s Proposed Objectives of Medical Ethics Education a Cited Here

- The ability to identify the moral aspects of medical practice

- The ability to obtain a valid consent or a valid refusal of treatment

- Knowledge of how to proceed if a patient is only partially competent or incompetent to consent or to refuse treatment

- Knowledge of how to proceed if a patient refuses treatment

- The ability to decide when it is morally justified to withhold information from a patient

- The ability to decide when it is morally justified to breach confidentiality

- Knowledge of the moral aspects of the care of patients with a poor prognosis, including patients who are terminally ill

- Additional areas considered for inclusion:

- Distribution of health care

a Objectives articulated in Culver et al, 1985. 1

In addition to these differences in learning objectives, the Romanell Report devotes attention to several areas not addressed by the DeCamp Report: methods of teaching, assessment strategies, and additional challenges and opportunities. We now turn our attention to these issues.

Teaching Methods

There is no single, best pedagogical approach for teaching medical ethics and professionalism. Learning styles and institutional resources vary, so teaching methods need to be flexible and varied to reflect this diversity. For example, to address the ACGME professionalism subcompetency “sensitivity and responsiveness to a diverse patient population,” 17 an educator could deliver a conventional didactic lecture, present clinical cases, or show a “trigger tape” intended to inspire discussion and debate. 27 Similarly, articles that illuminate issues of diversity by presenting patient perspectives 28 , 29 or that address the evolution of different “worldviews” on health and healing could be assigned and discussed. 30 Another pedagogical technique is to invite learners to write reflective narratives about cases they have been involved in that have raised ethics issues. 31 , 32 Whenever possible, medical ethics and professionalism instruction should involve collaboration among faculty from different disciplines to reinforce the team approach required in clinical practice. In recent years, multidisciplinary contributions to professionalism teaching have expanded beyond the traditional fields of philosophy, history, literature, law, and social sciences to include applied methods from the arts such as improvisational theater exercises, 33 comics drawing, 34 creative writing practices, 35 and fine art study. 36–38

Educational theory suggests that spacing and repetition of content improve learning. 39 A medical ethics and professionalism curriculum is therefore most likely to result in sustained changes in reasoning and behavior when it is longitudinal, such that early educational interventions are reinforced or advanced by subsequent exposures. For example, a method for ethics case analysis introduced in the first year of medical school could be reinforced in clinical clerkships by asking students to apply that method to analyze ethical issues they are encountering in clinical settings. In addition, learner-driven teaching strategies should be considered. For example, learners could identify clinical cases with ethics issues for discussion and take an active role in facilitating case discussions.