Nov 17, 2010

The six steps of the no-lose method, no comments:, post a comment.

Thanks for commenting! - P.E.T.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Problem-Solving Strategies and Obstacles

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Sean is a fact-checker and researcher with experience in sociology, field research, and data analytics.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Sean-Blackburn-1000-a8b2229366944421bc4b2f2ba26a1003.jpg)

JGI / Jamie Grill / Getty Images

- Application

- Improvement

From deciding what to eat for dinner to considering whether it's the right time to buy a house, problem-solving is a large part of our daily lives. Learn some of the problem-solving strategies that exist and how to use them in real life, along with ways to overcome obstacles that are making it harder to resolve the issues you face.

What Is Problem-Solving?

In cognitive psychology , the term 'problem-solving' refers to the mental process that people go through to discover, analyze, and solve problems.

A problem exists when there is a goal that we want to achieve but the process by which we will achieve it is not obvious to us. Put another way, there is something that we want to occur in our life, yet we are not immediately certain how to make it happen.

Maybe you want a better relationship with your spouse or another family member but you're not sure how to improve it. Or you want to start a business but are unsure what steps to take. Problem-solving helps you figure out how to achieve these desires.

The problem-solving process involves:

- Discovery of the problem

- Deciding to tackle the issue

- Seeking to understand the problem more fully

- Researching available options or solutions

- Taking action to resolve the issue

Before problem-solving can occur, it is important to first understand the exact nature of the problem itself. If your understanding of the issue is faulty, your attempts to resolve it will also be incorrect or flawed.

Problem-Solving Mental Processes

Several mental processes are at work during problem-solving. Among them are:

- Perceptually recognizing the problem

- Representing the problem in memory

- Considering relevant information that applies to the problem

- Identifying different aspects of the problem

- Labeling and describing the problem

Problem-Solving Strategies

There are many ways to go about solving a problem. Some of these strategies might be used on their own, or you may decide to employ multiple approaches when working to figure out and fix a problem.

An algorithm is a step-by-step procedure that, by following certain "rules" produces a solution. Algorithms are commonly used in mathematics to solve division or multiplication problems. But they can be used in other fields as well.

In psychology, algorithms can be used to help identify individuals with a greater risk of mental health issues. For instance, research suggests that certain algorithms might help us recognize children with an elevated risk of suicide or self-harm.

One benefit of algorithms is that they guarantee an accurate answer. However, they aren't always the best approach to problem-solving, in part because detecting patterns can be incredibly time-consuming.

There are also concerns when machine learning is involved—also known as artificial intelligence (AI)—such as whether they can accurately predict human behaviors.

Heuristics are shortcut strategies that people can use to solve a problem at hand. These "rule of thumb" approaches allow you to simplify complex problems, reducing the total number of possible solutions to a more manageable set.

If you find yourself sitting in a traffic jam, for example, you may quickly consider other routes, taking one to get moving once again. When shopping for a new car, you might think back to a prior experience when negotiating got you a lower price, then employ the same tactics.

While heuristics may be helpful when facing smaller issues, major decisions shouldn't necessarily be made using a shortcut approach. Heuristics also don't guarantee an effective solution, such as when trying to drive around a traffic jam only to find yourself on an equally crowded route.

Trial and Error

A trial-and-error approach to problem-solving involves trying a number of potential solutions to a particular issue, then ruling out those that do not work. If you're not sure whether to buy a shirt in blue or green, for instance, you may try on each before deciding which one to purchase.

This can be a good strategy to use if you have a limited number of solutions available. But if there are many different choices available, narrowing down the possible options using another problem-solving technique can be helpful before attempting trial and error.

In some cases, the solution to a problem can appear as a sudden insight. You are facing an issue in a relationship or your career when, out of nowhere, the solution appears in your mind and you know exactly what to do.

Insight can occur when the problem in front of you is similar to an issue that you've dealt with in the past. Although, you may not recognize what is occurring since the underlying mental processes that lead to insight often happen outside of conscious awareness .

Research indicates that insight is most likely to occur during times when you are alone—such as when going on a walk by yourself, when you're in the shower, or when lying in bed after waking up.

How to Apply Problem-Solving Strategies in Real Life

If you're facing a problem, you can implement one or more of these strategies to find a potential solution. Here's how to use them in real life:

- Create a flow chart . If you have time, you can take advantage of the algorithm approach to problem-solving by sitting down and making a flow chart of each potential solution, its consequences, and what happens next.

- Recall your past experiences . When a problem needs to be solved fairly quickly, heuristics may be a better approach. Think back to when you faced a similar issue, then use your knowledge and experience to choose the best option possible.

- Start trying potential solutions . If your options are limited, start trying them one by one to see which solution is best for achieving your desired goal. If a particular solution doesn't work, move on to the next.

- Take some time alone . Since insight is often achieved when you're alone, carve out time to be by yourself for a while. The answer to your problem may come to you, seemingly out of the blue, if you spend some time away from others.

Obstacles to Problem-Solving

Problem-solving is not a flawless process as there are a number of obstacles that can interfere with our ability to solve a problem quickly and efficiently. These obstacles include:

- Assumptions: When dealing with a problem, people can make assumptions about the constraints and obstacles that prevent certain solutions. Thus, they may not even try some potential options.

- Functional fixedness : This term refers to the tendency to view problems only in their customary manner. Functional fixedness prevents people from fully seeing all of the different options that might be available to find a solution.

- Irrelevant or misleading information: When trying to solve a problem, it's important to distinguish between information that is relevant to the issue and irrelevant data that can lead to faulty solutions. The more complex the problem, the easier it is to focus on misleading or irrelevant information.

- Mental set: A mental set is a tendency to only use solutions that have worked in the past rather than looking for alternative ideas. A mental set can work as a heuristic, making it a useful problem-solving tool. However, mental sets can also lead to inflexibility, making it more difficult to find effective solutions.

How to Improve Your Problem-Solving Skills

In the end, if your goal is to become a better problem-solver, it's helpful to remember that this is a process. Thus, if you want to improve your problem-solving skills, following these steps can help lead you to your solution:

- Recognize that a problem exists . If you are facing a problem, there are generally signs. For instance, if you have a mental illness , you may experience excessive fear or sadness, mood changes, and changes in sleeping or eating habits. Recognizing these signs can help you realize that an issue exists.

- Decide to solve the problem . Make a conscious decision to solve the issue at hand. Commit to yourself that you will go through the steps necessary to find a solution.

- Seek to fully understand the issue . Analyze the problem you face, looking at it from all sides. If your problem is relationship-related, for instance, ask yourself how the other person may be interpreting the issue. You might also consider how your actions might be contributing to the situation.

- Research potential options . Using the problem-solving strategies mentioned, research potential solutions. Make a list of options, then consider each one individually. What are some pros and cons of taking the available routes? What would you need to do to make them happen?

- Take action . Select the best solution possible and take action. Action is one of the steps required for change . So, go through the motions needed to resolve the issue.

- Try another option, if needed . If the solution you chose didn't work, don't give up. Either go through the problem-solving process again or simply try another option.

You can find a way to solve your problems as long as you keep working toward this goal—even if the best solution is simply to let go because no other good solution exists.

Sarathy V. Real world problem-solving . Front Hum Neurosci . 2018;12:261. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2018.00261

Dunbar K. Problem solving . A Companion to Cognitive Science . 2017. doi:10.1002/9781405164535.ch20

Stewart SL, Celebre A, Hirdes JP, Poss JW. Risk of suicide and self-harm in kids: The development of an algorithm to identify high-risk individuals within the children's mental health system . Child Psychiat Human Develop . 2020;51:913-924. doi:10.1007/s10578-020-00968-9

Rosenbusch H, Soldner F, Evans AM, Zeelenberg M. Supervised machine learning methods in psychology: A practical introduction with annotated R code . Soc Personal Psychol Compass . 2021;15(2):e12579. doi:10.1111/spc3.12579

Mishra S. Decision-making under risk: Integrating perspectives from biology, economics, and psychology . Personal Soc Psychol Rev . 2014;18(3):280-307. doi:10.1177/1088868314530517

Csikszentmihalyi M, Sawyer K. Creative insight: The social dimension of a solitary moment . In: The Systems Model of Creativity . 2015:73-98. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9085-7_7

Chrysikou EG, Motyka K, Nigro C, Yang SI, Thompson-Schill SL. Functional fixedness in creative thinking tasks depends on stimulus modality . Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts . 2016;10(4):425‐435. doi:10.1037/aca0000050

Huang F, Tang S, Hu Z. Unconditional perseveration of the short-term mental set in chunk decomposition . Front Psychol . 2018;9:2568. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02568

National Alliance on Mental Illness. Warning signs and symptoms .

Mayer RE. Thinking, problem solving, cognition, 2nd ed .

Schooler JW, Ohlsson S, Brooks K. Thoughts beyond words: When language overshadows insight. J Experiment Psychol: General . 1993;122:166-183. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.2.166

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- Register or Log In

- 0) { document.location='/search/'+document.getElementById('quicksearch').value.trim().toLowerCase(); }">

Chapter 9 Self-Quiz

Managing Conflict

Please note that this exercise is for self-study, and your instructor will not be able to see your responses.

Quiz Content

Are you sure, select your country.

No-lose Method

This is a democratic approach that results in caregivers and children resolving conflict in a manner in which all parties are satisfied with the solution.

How to use this method:

- Define: All parties communicate their perspectives of the “problem”.

- Brainstorm Solutions: All parties list all possible solutions to resolve the issue.

- Assess Solutions: All parties decide and discuss how they feel about all of the solutions.

- Best Solution: All parties decide upon and agree to implement the best solution.

- Plan in Action: All parties put the best solution into practice.

- Follow-Up: Adult(s) proactively discuss the problem and solution with the child(ren) to revisit the situation [1] .

- Define: The “problem” is that siblings are fighting over a book.

- Brainstorm Solutions: The children can take turns reading the book; each child can read a different book; both children can read with each other at the same time with that book; a parent can remove the book so both children need to find different books.

- Assess Solutions: Both children want to read the book together.

- Best Solution: The children and parent agree that the children will read the book together as long as the children do not fight. If they fight while reading the book, the parent will remove the book and both children will need to take a break.

- Plan in Action: The children read the book together and do not fight.

- Follow-Up: Later that same day, the parent asks if they both enjoyed reading that book together. Both children agreed it was an enjoyable time. The parent praised them for not fighting and for solving the issue.

Key Takeaways

- This method is used to resolve conflict where every party involved discusses their perspective on the problem and possible solutions.

- A solution that satisfies all parties is decided and agreed upon.

- Heath, P. (2013). Parent-child relations: Context, research, and application (3rd Ed.). Pearson. ↵

Parenting and Family Diversity Issues Copyright © 2020 by Diana Lang is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

7.5 Problem-Solving

Questions to Consider:

- How can determining the best approach to solve a problem help you generate solutions?

- Why do thinkers create multiple solutions to problems?

When we’re solving a problem, whether at work, school, or home, we are being asked to perform multiple, often complex, tasks. The most effective problem-solving approach includes some variation of the following steps:

- Determine the issue(s)

- Recognize other perspectives

- Think of multiple possible results

- Research and evaluate the possibilities

- Select the best result(s)

- Communicate your findings

- Establish logical action items based on your analysis

Determining the best approach to any given problem and generating more than one possible solution to the problem constitutes the complicated process of problem-solving. People who are good at these skills are highly marketable because many jobs consist of a series of problems that need to be solved for production, services, goods, and sales to continue smoothly. Think about what happens when a worker at your favorite coffee shop slips on a wet spot behind the counter, dropping several drinks she just prepared. One problem is the employee may be hurt, in need of attention, and probably embarrassed; another problem is that several customers do not have the drinks they were waiting for; and another problem is that stopping production of drinks (to care for the hurt worker, to clean up her spilled drinks, to make new drinks) causes the line at the cash register to back up. A good manager has to juggle all of these elements to resolve the situation as quickly and efficiently as possible. That resolution and return to standard operations doesn’t happen without a great deal of thinking: prioritizing needs, shifting other workers off one station onto another temporarily, and dealing with all the people involved, from the injured worker to the impatient patrons.

Determining the Best Approach

Faced with a problem-solving opportunity, you must assess the skills you will need to create solutions. Problem-solving can involve many different types of thinking. You may have to call on your creative, analytical, or critical thinking skills—or more frequently, a combination of several different types of thinking—to solve a problem satisfactorily. When you approach a situation, how can you decide what is the best type of thinking to employ? Sometimes the answer is obvious; if you are working a scientific challenge, you likely will use analytical thinking; if you are a design student considering the atmosphere of a home, you may need to tap into creative thinking skills; and if you are an early childhood education major outlining the logistics involved in establishing a summer day camp for children, you may need a combination of critical, analytical, and creative thinking to solve this challenge.

What sort of thinking do you imagine initially helped in the following scenarios? How would the other types of thinking come into resolving these problems?

- Analytical thinking

- Creative thinking

- Critical thinking

Write a one- to two-sentence rationale for why you chose the answers you did on the above survey.

Generating Multiple Solutions

Why do you think it is important to provide multiple solutions when you’re going through the steps to solve problems? Typically, you’ll end up only using one solution at a time, so why expend the extra energy to create alternatives? If you planned a wonderful trip to Europe and had all the sites you want to see planned out and reservations made, you would think that your problem-solving and organizational skills had quite a workout. But what if when you arrived, the country you’re visiting is enmeshed in a public transportation strike experts predict will last several weeks if not longer? A back-up plan would have helped you contemplate alternatives you could substitute for the original plans. You certainly cannot predict every possible contingency—sick children, weather delays, economic downfalls—but you can be prepared for unexpected issues to come up and adapt more easily if you plan for multiple solutions.

Write out at least two possible solutions to these dilemmas:

- Your significant other wants a birthday present—you have no cash.

- You have three exams scheduled on a day when you also need to work.

- Your car needs new tires, an oil change, and gas—you have no cash. (Is there a trend here?)

- You have to pass a running test for your physical education class, but you’re out of shape.

Providing more than one solution to a problem gives people options. You may not need several options, but having more than one solution will allow you to feel more in control and part of the problem-solving process.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/college-success/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Amy Baldwin

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: College Success

- Publication date: Mar 27, 2020

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/college-success/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/college-success/pages/7-5-problem-solving

© Sep 20, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

8.5: Problem Solving and Decision-Making in Groups

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 106475

- Lisa Coleman, Thomas King, & William Turner

- Southwest Tennessee Community College

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- Discuss the common components and characteristics of problems.

- Explain the five steps of the group problem-solving process.

- Discuss the various influences on decision-making.

Although the steps of problem-solving and decision-making that we will discuss next may seem obvious, we often don’t think to or choose not to use them. Instead, we start working on a problem and later realize we are lost and have to backtrack. I’m sure we’ve all reached a point in a project or task and had the “OK, now what?” moment. I’ve recently taken up some carpentry projects as a functional hobby, and I have developed a great respect for the importance of advanced planning. It’s frustrating to get to a crucial point in building or fixing something only to realize that you have to unscrew a support board that you already screwed in, have to drive back to the hardware store to get something that you didn’t think to get earlier, or have to completely start over. In this section, we will discuss the group problem-solving process, methods of decision making, and influences on these processes.

Group Problem-Solving Process

There are several variations of similar problem-solving models based on US American scholar John Dewey’s reflective thinking process (Bormann & Bormann, 1988). As you read through the steps in the process, think about how we can apply what we have learned regarding the general and specific elements of problems. Some of the following steps are straightforward, and they are things we would logically do when faced with a problem. However, taking a deliberate and systematic approach to problem-solving has been shown to benefit group functioning and performance. A deliberate approach is especially beneficial for groups that do not have an established history of working together and will only be able to meet occasionally. Although a group should attend to each step of the process, group leaders or other group members who facilitate problem-solving should be cautious not to dogmatically follow each element of the process or force a group along. Such a lack of flexibility could limit group member input and negatively affect the group’s cohesion and climate.

Step 1: Define the Problem

Define the problem by considering the three elements shared by every problem: the current undesirable situation , the goal or more desirable situation, and obstacles in the way (Adams & Galanes, 2009). At this stage, group members share what they know about the current situation, without proposing solutions or evaluating the information. Here are some good questions to ask during this stage: What is the current difficulty? How did we come to know that the difficulty exists? Who/what is involved? Why is it meaningful/urgent/important? What have the effects been so far? What, if any, elements of the difficulty require clarification? At the end of this stage, the group should be able to compose a single sentence that summarizes the problem called a problem statement. Avoid wording in the problem statement or question that hints at potential solutions. A small group formed to investigate ethical violations of city officials could use the following problem statement: “Our state does not currently have a mechanism for citizens to report suspected ethical violations by city officials.”

Step 2: Analyze the Problem

During this step, a group should analyze the problem and the group’s relationship to the problem. Whereas the first step involved exploring the “what” related to the problem, this step focuses on the “why.” At this stage, group members can discuss the potential causes of the difficulty. Group members may also want to begin setting out an agenda or timeline for the group’s problem-solving process, looking forward to the other steps. To fully analyze the problem, the group can discuss the five common problem variables discussed before. Here are two examples of questions that the group formed to address ethics violations might ask: Why doesn’t our city have an ethics reporting mechanism? Do cities of similar size have such a mechanism? Once the problem has been analyzed, the group can pose a problem question that will guide the group as it generates possible solutions. “How can citizens report suspected ethical violations of city officials and how will such reports be processed and addressed?” As you can see, the problem question is more complex than the problem statement, since the group has moved on to a more in-depth discussion of the problem during step 2.

Step 3: Generate Possible Solutions

During this step, group members generate possible solutions to the problem. Again, solutions should not be evaluated at this point, only proposed and clarified. The question should be what could we do to address this problem, not what should we do to address it. It is perfectly OK for a group member to question another person’s idea by asking something like “What do you mean?” or “Could you explain your reasoning more?” Discussions at this stage may reveal a need to return to previous steps to better define or more fully analyze a problem. Since many problems are multifaceted, it is necessary for group members to generate solutions for each part of the problem separately, making sure to have multiple solutions for each part. Stopping the solution-generating process prematurely can lead to groupthink. For the problem question previously posed, the group would need to generate solutions for all three parts of the problem included in the question. Possible solutions for the first part of the problem (How can citizens report ethical violations?) may include “online reporting system, e-mail, in-person, anonymously, on-the-record,” and so on. Possible solutions for the second part of the problem (How will reports be processed?) may include “daily by a newly appointed ethics officer, weekly by a nonpartisan nongovernment employee,” and so on. Possible solutions for the third part of the problem (How will reports be addressed?) may include “by a newly appointed ethics commission, by the accused’s supervisor, by the city manager,” and so on.

Step 4: Evaluate Solutions

During this step, solutions can be critically evaluated based on their credibility, completeness, and worth. Once the potential solutions have been narrowed based on more obvious differences in relevance and/or merit, the group should analyze each solution based on its potential effects—especially negative effects. Groups that are required to report the rationale for their decision or whose decisions may be subject to public scrutiny would be wise to make a set list of criteria for evaluating each solution. Additionally, solutions can be evaluated based on how well they fit with the group’s charge and the abilities of the group. To do this, group members may ask, “Does this solution live up to the original purpose or mission of the group?” and “Can the solution actually be implemented with our current resources and connections?” and “How will this solution be supported, funded, enforced, and assessed?” Secondary tensions and substantive conflict, two concepts discussed earlier, emerge during this step of problem-solving, and group members will need to employ effective critical thinking and listening skills.

Decision-making is part of the larger process of problem-solving and it plays a prominent role in this step. While there are several fairly similar models for problem-solving, there are many varied decision-making techniques that groups can use. For example, to narrow the list of proposed solutions, group members may decide by majority vote, by weighing the pros and cons, or by discussing them until a consensus is reached. There are also more complex decision-making models like the “six hats method,” which we will discuss later. Once the final decision is reached, the group leader or facilitator should confirm that the group is in agreement. It may be beneficial to let the group break for a while or even to delay the final decision until a later meeting to allow people time to evaluate it outside of the group context.

Step 5: Implement and Assess the Solution

Implementing the solution requires some advanced planning, and it should not be rushed unless the group is operating under strict time restraints or delay may lead to some kind of harm. Although some solutions can be implemented immediately, others may take days, months, or years. As was noted earlier, it may be beneficial for groups to poll those who will be affected by the solution as to their opinion of it or even do a pilot test to observe the effectiveness of the solution and how people react to it. Before implementation, groups should also determine how and when they would assess the effectiveness of the solution by asking, “How will we know if the solution is working or not?” Since solution assessment will vary based on whether or not the group is disbanded, groups should also consider the following questions: If the group disbands after implementation, who will be responsible for assessing the solution? If the solution fails, will the same group reconvene or will a new group be formed?

Certain elements of the solution may need to be delegated out to various people inside and outside the group. Group members may also be assigned to implement a particular part of the solution based on their role in the decision-making or because it connects to their area of expertise. Likewise, group members may be tasked with publicizing the solution or “selling” it to a particular group of stakeholders. Last, the group should consider its future. In some cases, the group will get to decide if it will stay together and continue working on other tasks or if it will disband. In other cases, outside forces determine the group’s fate.

“Getting Competent”: Problem Solving and Group Presentations

Giving a group presentation requires that individual group members and the group as a whole solve many problems and make many decisions. Although having more people involved in a presentation increases logistical difficulties and has the potential to create more conflict, a well-prepared and well-delivered group presentation can be more engaging and effective than a typical presentation. The main problems facing a group giving a presentation are (1) dividing responsibilities, (2) coordinating schedules and time management, and (3) working out the logistics of the presentation delivery.

In terms of dividing responsibilities, assigning individual work at the first meeting and then trying to fit it all together before the presentation (which is what many college students do when faced with a group project) is not the recommended method. Integrating content and visual aids created by several different people into a seamless final product takes time and effort, and the person “stuck” with this job at the end usually ends up developing some resentment toward his or her group members. While it’s OK for group members to do work independently outside of group meetings, spend time working together to help set up some standards for content and formatting expectations that will help make later integration of work easier. Taking the time to complete one part of the presentation together can help set those standards for later individual work. Discuss the roles that various group members will play openly so there isn’t role confusion. There could be one point person for keeping track of the group’s progress and schedule, one point person for communication, one point person for content integration, one point person for visual aids, and so on. Each person shouldn’t do all that work on his or her own but help focus the group’s attention on his or her specific area during group meetings (Stanton, 2009).

Scheduling group meetings is one of the most challenging problems groups face, given people’s busy lives. From the beginning, it should be clearly communicated that the group needs to spend considerable time in face-to-face meetings, and group members should know that they may have to make an occasional sacrifice to attend. Especially important is the commitment to scheduling time to rehearse the presentation. Consider creating a contract of group guidelines that include expectations for meeting attendance to increase group members’ commitment.

Group presentations require members to navigate many logistics of their presentation. While it may be easier for a group to assign each member to create a five-minute segment and then transition from one person to the next, this is definitely not the most engaging method. Creating a master presentation and then assigning individual speakers creates a more fluid and dynamic presentation and allows everyone to become familiar with the content, which can help if a person doesn’t show up to present and during the question-and-answer section. Once the content of the presentation is complete, figure out introductions, transitions, visual aids, and the use of time and space (Stanton, 2012). In terms of introductions, figure out if one person will introduce all the speakers at the beginning, if speakers will introduce themselves at the beginning, or if introductions will occur as the presentation progresses. In terms of transitions, make sure each person has included in his or her speaking notes when presentation duties switch from one person to the next. Visual aids have the potential to cause hiccups in a group presentation if they aren’t fluidly integrated. Practicing with visual aids and having one person control them may help prevent this. Know how long your presentation is and know how you’re going to use the space. Presenters should know how long the whole presentation should be and how long each of their segments should be so that everyone can share the responsibility of keeping time. Also, consider the size and layout of the presentation space. You don’t want presenters huddled in a corner until it’s their turn to speak or trapped behind furniture when their turn comes around.

- Of the three main problems facing group presenters, which do you think is the most challenging and why?

- Why do you think people tasked with a group presentation (especially students) prefer to divide the parts up and have members work on them independently before coming back together and integrating each part? What problems emerge from this method? In what ways might developing a master presentation and then assign parts to different speakers be better than the more divided method? What are the drawbacks to the master presentation method?

Specific Decision-Making Techniques

Some decision-making techniques involve determining a course of action based on the level of agreement among the group members. These methods include majority , expert , authority , and consensus rule . Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) “Pros and Cons of Agreement-Based Decision-Making Techniques” reviews the pros and cons of each of these methods.

Majority rule is a commonly used decision-making technique in which a majority (one-half plus one) must agree before a decision is made . A show-of-hands vote, a paper ballot, or an electronic voting system can determine the majority choice. Many decision-making bodies, including the US House of Representatives, Senate, and Supreme Court, use majority rule to make decisions, which shows that it is often associated with democratic decision-making since each person gets one vote and each vote counts equally. Of course, other individuals and mediated messages can influence a person’s vote, but since the voting power is spread out over all group members, it is not easy for one person or party to take control of the decision-making process. In some cases—for example, to override a presidential veto or to amend the constitution—a supermajority of two-thirds may be required to make a decision.

Minority rule is a decision-making technique in which a designated authority or expert has the final say over a decision and may or may not consider the input of other group members . When a designated expert makes a decision by minority rule, there may be buy-in from others in the group, especially if the members of the group didn’t have relevant knowledge or expertise. When a designated authority makes decisions, buy-in will vary based on group members’ level of respect for the authority. For example, decisions made by an elected authority may be more accepted by those who elected him or her than by those who didn’t. As with majority rule, this technique can be time-saving. Unlike majority rule, one person or party can have control over the decision-making process. This type of decision-making is more similar to that used by monarchs and dictators. An obvious negative consequence of this method is that the needs or wants of one person can override the needs and wants of the majority. A minority deciding for the majority has led to negative consequences throughout history. The white Afrikaner minority that ruled South Africa for decades instituted apartheid, which was a system of racial segregation that disenfranchised and oppressed the majority population. The quality of the decision and its fairness really depends on the designated expert or authority.

Consensus rule is a decision-making technique in which all members of the group must agree on the same decision . On rare occasions, a decision may be ideal for all group members, which can lead to a unanimous agreement without further debate and discussion. Although this can be positive, be cautious that this isn’t a sign of groupthink. More typically, the consensus is reached only after a lengthy discussion. On the plus side, consensus often leads to high-quality decisions due to the time and effort it takes to get everyone in agreement. Group members are also more likely to be committed to the decision because of their investment in reaching it. On the negative side, the ultimate decision is often one that all group members can live with but not one that’s ideal for all members. Additionally, the process of arriving at a consensus also includes conflict, as people debate ideas and negotiate the interpersonal tensions that may result.

“Getting Critical”: Six Hats Method of Decision Making

Edward de Bono developed the Six Hats method of thinking in the late 1980s, and it has since become a regular feature in decision-making training in business and professional contexts (de Bono, 1985). The method’s popularity lies in its ability to help people get out of habitual ways of thinking and to allow group members to play different roles and see a problem or decision from multiple points of view. The basic idea is that each of the six hats represents a different way of thinking, and when we figuratively switch hats, we switch the way we think. The hats and their style of thinking are as follows:

- White hat. Objective—focuses on seeking information such as data and facts and then processes that information in a neutral way.

- Red hat. Emotional—uses intuition, gut reactions, and feelings to judge information and suggestions.

- Black hat. Negative—focus on potential risks, point out possibilities for failure, and evaluates information cautiously and defensively.

- Yellow hat. Positive—is optimistic about suggestions and future outcomes gives constructive and positive feedback, points out benefits and advantages.

- Green hat. Creative—try to generate new ideas and solutions, think “outside the box.”

- Blue hat. Philosophical—uses metacommunication to organize and reflect on the thinking and communication taking place in the group, facilitates who wears what hat and when group members change hats.

Specific sequences or combinations of hats can be used to encourage strategic thinking. For example, the group leader may start off wearing the Blue Hat and suggest that the group start their decision-making process with some “White Hat thinking” in order to process through facts and other available information. During this stage, the group could also process through what other groups have done when faced with a similar problem. Then the leader could begin an evaluation sequence starting with two minutes of “Yellow Hat thinking” to identify potential positive outcomes, then “Black Hat thinking” to allow group members to express reservations about ideas and point out potential problems, then “Red Hat thinking” to get people’s gut reactions to the previous discussion, then “Green Hat thinking” to identify other possible solutions that are more tailored to the group’s situation or completely new approaches. At the end of a sequence, the Blue Hat would want to summarize what was said and begin a new sequence. To successfully use this method, the person wearing the Blue Hat should be familiar with different sequences and plan some of the thinking patterns ahead of time based on the problem and the group members. Each round of thinking should be limited to a certain time frame (two to five minutes) to keep the discussion moving.

- This decision-making method has been praised because it allows group members to “switch gears” in their thinking and allows for role-playing, which lets people express ideas more freely. How can this help enhance critical thinking? Which combination of hats do you think would be best for a critical thinking sequence?

- What combinations of hats might be useful if the leader wanted to break the larger group up into pairs and why? For example, what kind of thinking would result from putting Yellow and Red together, Black and White together, or Red and White together, and so on?

- Based on your preferred ways of thinking and your personality, which hat would be the best fit for you? Which would be the most challenging? Why?

Influences on Decision Making

The personalities of group members, especially leaders and other active members, affect the climate of the group. Group member personalities can be categorized based on where they fall on a continuum anchored by the following descriptors: dominant/submissive, friendly/unfriendly, and instrumental/emotional (Cragan & Wright, 1999). The more group members there are in any extreme of these categories, the more likely it that the group climate will also shift to resemble those characteristics.

- Dominant versus submissive. Group members that are more dominant act more independently and directly, initiate conversations, take up more space, make more direct eye contact, seek leadership positions, and take control over decision-making processes. More submissive members are reserved, contribute to the group only when asked to, avoid eye contact, and leave their personal needs and thoughts unvoiced or give in to the suggestions of others.

- Friendly versus unfriendly. Group members on the friendly side of the continuum find a balance between talking and listening, don’t try to win at the expense of other group members, are flexible but not weak, and value democratic decision-making. Unfriendly group members are disagreeable, indifferent, withdrawn, and selfish, which leads them to either not invest in decision making or direct it in their own interest rather than in the interest of the group.

- Instrumental versus emotional. Instrumental group members are emotionally neutral, objective, analytical, task-oriented, and committed followers, which leads them to work hard and contribute to the group’s decision-making as long as it is orderly and follows agreed-on rules. Emotional group members are creative, playful, independent, unpredictable, and expressive, which leads them to make rash decisions, resist group norms or decision-making structures and switch often from relational to task focus.

Domestic Diversity and Group Communication

While it is becoming more likely that we will interact in small groups with international diversity, we are guaranteed to interact in groups that are diverse in terms of the cultural identities found within a single country or the subcultures found within a larger cultural group.

Gender stereotypes sometimes influence the roles that people play within a group. For example, the stereotype that women are more nurturing than men may lead group members (both male and female) to expect that women will play the role of supporters or harmonizers within the group. Since women have primarily performed secretarial work since the 1900s, it may also be expected that women will play the role of the recorder. In both of these cases, stereotypical notions of gender place women in roles that are typically not as valued in group communication. The opposite is true for men. In terms of leadership, despite notable exceptions, research shows that men fill an overwhelmingly disproportionate amount of leadership positions. We are socialized to see certain behaviors by men as indicative of leadership abilities, even though they may not be. For example, men are often perceived to contribute more to a group because they tend to speak first when asked a question or to fill a silence and are perceived to talk more about task-related matters than relationally oriented matters. Both of these tendencies create a perception that men are more engaged with the task. Men are also socialized to be more competitive and self-congratulatory, meaning that their communication may be seen as dedicated and their behaviors seen as powerful, and that when their work isn’t noticed they will be more likely to make it known to the group rather than take silent credit. Even though we know that the relational elements of a group are crucial for success, even in high-performance teams, that work is not as valued in our society as task-related work.

Despite the fact that some communication patterns and behaviors related to our typical (and stereotypical) gender socialization affects how we interact in and form perceptions of others in groups, the differences in group communication that used to be attributed to gender in early group communication research seem to be diminishing. This is likely due to the changing organizational cultures from which much group work emerges, which have now had more than sixty years to adjust to women in the workplace. It is also due to a more nuanced understanding of gender-based research, which doesn’t take a stereotypical view from the beginning as many of the early male researchers did. Now, instead of biological sex being assumed as a factor that creates inherent communication differences, group communication scholars see that men and women both exhibit a range of behaviors that are more or less feminine or masculine. It is these gendered behaviors, and not a person’s gender, that seem to have more of an influence on perceptions of group communication. Interestingly, group interactions are still masculinist in that male and female group members prefer a more masculine communication style for task leaders and that both males and females in this role are more likely to adapt to a more masculine communication style. Conversely, men who take on social-emotional leadership behaviors adopt a more feminine communication style. In short, it seems that although masculine communication traits are more often associated with high-status positions in groups, both men and women adapt to this expectation and are evaluated similarly (Haslett & Ruebush, 1999).

Other demographic categories are also influential in group communication and decision-making. In general, group members have an easier time communicating when they are more similar than different in terms of race and age. This ease of communication can make group work more efficient, but the homogeneity, meaning the members are more similar, may sacrifice some creativity. n general, groups that are culturally heterogeneous have better overall performance than more homogenous groups (Haslett & Ruebush, 1999). These groups benefit from the diversity of perspectives in terms of the quality of decision-making and creativity of output.

The benefits and challenges that come with the diversity of group members are important to consider. Since we will all work in diverse groups, we should be prepared to address potential challenges in order to reap the benefits. Diverse groups may be wise to coordinate social interactions outside of group time in order to find common ground that can help facilitate interaction and increase group cohesion. We should be sensitive but not let sensitivity create fear of “doing something wrong” which then prevents us from having meaningful interactions.

Key Takeaways

- Every problem has common components: an undesirable situation, the desired situation, and obstacles between the undesirable and desirable situations. Every problem also has a set of characteristics that vary among problems, including task difficulty, number of possible solutions, group member interest in the problem, group familiarity with the problem, and the need for solution acceptance.

- Define the problem by creating a problem statement that summarizes it.

- Analyze the problem and create a problem question that can guide solution generation.

- Generate possible solutions. Possible solutions should be offered and listed without stopping to evaluate each one.

- Evaluate the solutions based on their credibility, completeness, and worth. Groups should also assess the potential effects of the narrowed list of solutions.

- Implement and assess the solution. Aside from enacting the solution, groups should determine how they will know the solution is working or not.

- Common decision-making techniques include majority rule, minority rule, and consensus rule. Only a majority, usually one-half plus one, must agree before a decision is made with majority rule. With minority rule, designated authority or expert has final say over a decision, and the input of group members may or may not be invited or considered. With consensus rule, all members of the group must agree on the same decision.

- Situational factors include the degree of freedom a group has to make its own decisions, the level of uncertainty facing the group and its task, the size of the group, the group’s access to information, and the origin and urgency of the problem.

- Personality influences on decision making include a person’s value orientation (economic, aesthetic, theoretical, political, or religious), and personality traits (dominant/submissive, friendly/unfriendly, and instrumental/emotional).

- Cultural influences on decision making include the heterogeneity or homogeneity of the group makeup; cultural values and characteristics such as individualism/collectivism, power distance, and high-/low-context communication styles; and gender and age differences.

- Scenario 1. Task difficulty is high, the number of possible solutions is high, group interest in the problem is high, group familiarity with the problem is low, and the need for solution acceptance is high.

- Scenario 2. Task difficulty is low, the number of possible solutions is low, group interest in the problem is low, group familiarity with the problem is high, and the need for solution acceptance is low.

- Scenario 1: Academic. A professor asks his or her class to decide whether the final exam should be an in-class or take-home exam.

- Scenario 2: Professional. A group of coworkers must decide which person from their department to nominate for a company-wide award.

- Scenario 3: Personal. A family needs to decide how to divide the belongings and estate of a deceased family member who did not leave a will.

- Scenario 4: Civic. A local branch of a political party needs to decide what five key issues it wants to include in the national party’s platform.

- Group communication researchers have found that heterogeneous groups (composed of diverse members) have advantages over homogenous (more similar) groups. Discuss a group situation you have been in where diversity enhanced your and/or the group’s experience.

Adams, K., and Gloria G. Galanes, Communicating in Groups: Applications and Skills , 7th ed. (Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill, 2009), 220–21.

Allen, B. J., Difference Matters: Communicating Social Identity , 2nd ed. (Long Grove, IL: Waveland, 2011), 5.

Bormann, E. G., and Nancy C. Bormann, Effective Small Group Communication , 4th ed. (Santa Rosa, CA: Burgess CA, 1988), 112–13.

Clarke, G., “The Silent Generation Revisited,” Time, June 29, 1970, 46.

Cragan, J. F., and David W. Wright, Communication in Small Group Discussions: An Integrated Approach , 3rd ed. (St. Paul, MN: West Publishing, 1991), 77–78.

de Bono, E., Six Thinking Hats (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1985).

Delbecq, A. L., and Andrew H. Ven de Ven, “A Group Process Model for Problem Identification and Program Planning,” The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 7, no. 4 (1971): 466–92.

Haslett, B. B., and Jenn Ruebush, “What Differences Do Individual Differences in Groups Make?: The Effects of Individuals, Culture, and Group Composition,” in The Handbook of Group Communication Theory and Research , ed. Lawrence R. Frey (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1999), 133.

Napier, R. W., and Matti K. Gershenfeld, Groups: Theory and Experience , 7th ed. (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 2004), 292.

Osborn, A. F., Applied Imagination (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1959).

Spranger, E., Types of Men (New York: Steckert, 1928).

Stanton, C., “How to Deliver Group Presentations: The Unified Team Approach,” Six Minutes Speaking and Presentation Skills , November 3, 2009, accessed August 28, 2012, http://sixminutes.dlugan.com/group-presentations-unified-team-approach .

Thomas, D. C., “Cultural Diversity and Work Group Effectiveness: An Experimental Study,” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 30, no. 2 (1999): 242–63.

Welcome to Gordon Training International

Gti has been helping people all over the world have better relationships at work, at home, and in schools through the gordon model skills., we hope to help you, too.

What Can You Win with the No Lose Method?

Excerpted from L.E.T. book by Dr. Thomas Gordon

What ARE the Benefits of the No-Lose Method?

- Increased Commitment to Carry Out the Decision

Everyone has had the experience of feeling a strong commitment to carry out a decision because of having had the chance to participate in formulating that decision. With a voice in the decision-making process, a person somehow has more motivation to implement the decision than if someone else unilaterally makes it. Psychologists call this commonsense idea the “Principle of Participation.” It affirms the well-known phenomenon that when people participate in the problem-solving process and develop a mutually acceptable solution, they get the feeling it is “their” decision. They were responsible for helping to shape the decision, so they feel responsible for seeing that it works.

This heightened sense of responsibility or commitment usually means that less effort is required from the leader to enforce compliance—less need for the leader to play the cop, as I pointed out earlier. Obviously, this yields a distinct saving of time for the leader and makes available more “productive work” time. A related benefit is greater organizational efficiency: when decisions are made, they get implemented; when conflicts are resolved, they stay resolved.

- Higher-Quality Decisions

Method III enlists the creativity, experience, and brain-power of all parties involved in a conflict. It follows that this method would often produce high-quality decisions. And so it does. “Two heads are better than one” makes particularly good sense in conflict resolution because the needs of both (or all) parties must be accurately represented. Also, with both parties participating in the solution-generating, the odds are that they will brainstorm a larger number of creative solutions. Finally, the presence of both parties is necessary so each can judge which solution best meets their needs.

It would be inconceivable to me, for example, to try to resolve a conflict between myself and one of my children (or my wife, or one of my group members) without their active participation—stating their needs and understanding mine, offering their solutions and hearing mine, evaluating each solution against their experience and considering my evaluations based on my own experience. When I find myself in conflict with others, I want their help so we can find our way out of that conflict, with nobody losing. With such help I’ll trust the quality of the solution much more than I’d trust one that I selected entirely on my own.

- Warmer Relationships

One of the most predictable outcomes of the No-Lose Method is that the parties to the conflict end up feeling good about each other. The resentment that usually follows either of the win-lose methods is absent in Method III. Instead, after a successful No-Lose decision, there emerges a positive feeling of liking each other—yes, even loving each other. It probably comes from each person appreciating that the other was willing to be considerate of their needs and took the time to search for a solution that would make each happy. What better proof of caring?

- Quicker Decisions

Have you ever experienced getting into a conflict with someone and then having that conflict go unresolved for weeks or months because you couldn’t for the life of you figure out a solution? Then you found the courage to approach the person and invite him to join with you to try and resolve it. Much to your surprise, you reached an amicable and mutually acceptable solution in a matter of minutes.

This is not unusual. The No-Lose Method often helps people in conflict get their feelings and needs out in the open, honestly face the issues, and explore possible solutions. Once started, the problem-solving process can lead quickly to a no-lose solution because it helps bring out a lot of data (facts and feelings) unavailable to either of the parties operating separately.

Then, too, many conflicts between people are very complex, particularly in organizations where differences arise over complicated technological matters, sensitive financial issues, and sticky human problems. Often these conflicts are resolved much more quickly by involving everyone who possesses relevant data or who might be affected by the decision.

- No “Selling” Is Required

You will recall how Method I usually requires that leaders spend time selling their decisions to those who must carry them out, over and above the time involved in simply making the decision. This second step is seldom required in Method III, obviously, because the final decision, once accepted by all the parties to the conflict, needs no selling afterwards—everyone is already sold.

Beyond Intractability

The Hyper-Polarization Challenge to the Conflict Resolution Field: A Joint BI/CRQ Discussion BI and the Conflict Resolution Quarterly invite you to participate in an online exploration of what those with conflict and peacebuilding expertise can do to help defend liberal democracies and encourage them live up to their ideals.

Follow BI and the Hyper-Polarization Discussion on BI's New Substack Newsletter .

Hyper-Polarization, COVID, Racism, and the Constructive Conflict Initiative Read about (and contribute to) the Constructive Conflict Initiative and its associated Blog —our effort to assemble what we collectively know about how to move beyond our hyperpolarized politics and start solving society's problems.

By Brad Spangler

January 2013

Original Publication September 2003, updated January 2013 by Heidi Burgess

Win-win, win-lose, and lose-lose are game theory terms that refer to the possible outcomes of a game or dispute involving two sides, and more importantly, how each side perceives their outcome relative to their standing before the game. For example, a "win" results when the outcome of a negotiation is better than expected, a "loss" when the outcome is worse than expected. Two people may receive the same outcome in measurable terms, say $10, but for one side that may be a loss, while for the other it is a win. In other words, expectations determine one's perception of any given result.

Win-win outcomes occur when each side of a dispute feels they have won. Since both sides benefit from such a scenario, any resolutions to the conflict are likely to be accepted voluntarily. The process of integrative bargaining aims to achieve, through cooperation, win-win outcomes.

Win-lose situations result when only one side perceives the outcome as positive. Thus, win-lose outcomes are less likely to be accepted voluntarily. Distributive bargaining processes, based on a principle of competition between participants, are more likely than integrative bargaining to end in win-lose outcomes--or they may result in a situation where each side gets part of what he or she wanted, but not as much as they might have gotten if they had used integrative bargaining.

Lose-lose means that all parties end up being worse off. An example of this would be a budget-cutting negotiation in which all parties lose money. The intractable budget debates in Congress in 2012-13 are example of lose-lose situations. Cuts are essential--the question is where they will be made and who will be hurt. In some lose-lose situations, all parties understand that losses are unavoidable and that they will be evenly distributed. In such situations, lose-lose outcomes can be preferable to win-lose outcomes because the distribution is at least considered to be fair.[1]

In other situations, though, lose-lose outcomes occur when win-win outcomes might have been possible. The classic example of this is called the prisoner's dilemma in which two prisoners must decide whether to confess to a crime. Neither prisoner knows what the other will do. The best outcome for prisoner A occurs if he/she confesses, while prisoner B keeps quiet. In this case, the prisoner who confesses and implicates the other is rewarded by being set free, and the other (who stayed quiet) receives the maximum sentence, as s/he didn't cooperate with the police, yet they have enough evidence to convict. (This is a win-lose outcome.) The same goes for prisoner B. But if both prisoners confess (trying to take advantage of their partner), they each serve the maximum sentence (a lose-lose outcome). If neither confesses, they both serve a reduced sentence (a win-win outcome, although the win is not as big as the one they would have received in the win-lose scenario).

This situation occurs fairly often, as win-win outcomes can only be identified through cooperative (or integrative) bargaining, and are likely to be overlooked if negotiations take a competitive distributive) stance.

The key thing to remember is that any negotiation may be reframed (placed in a new context) so that expectations are lowered. In the prisoner's dilemma, for example, if both prisoners are able to perceive the reduced sentence as a win rather than a loss, then the outcome is a win-win situation. Thus, with lowered expectations, it may be possible for negotiators to craft win-win solutions out of a potentially lose-lose situation. However, this requires that the parties sacrifice their original demands for lesser ones.

[1] The above definitions were drawn from: Heidi Burgess and Guy Burgess, Encyclopedia of Conflict Resolution (Denver: ABC-CLIO, 1997), 306-307, 309-310. < http://www.amazon.com/Encyclopedia-Conflict-Resolution-Heidi-Burgess/dp/0874368391 >.

Use the following to cite this article: Spangler, Brad. "Win-Win, Win-Lose, and Lose-Lose Situations." Beyond Intractability . Eds. Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess. Conflict Information Consortium, University of Colorado, Boulder. Posted: June 2003 < http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/win-lose >.

Additional Resources

The intractable conflict challenge.

Our inability to constructively handle intractable conflict is the most serious, and the most neglected, problem facing humanity. Solving today's tough problems depends upon finding better ways of dealing with these conflicts. More...

Selected Recent BI Posts Including Hyper-Polarization Posts

- Massively Parallel Peace and Democracy Building Roles - Part 4 -- The last in a four-part series of MPP roles looking at those who help balance power so that everyone in society is treated fairly, and those who try to defend democracy from those who would destroy it.

- Massively Parallel Peace and Democracy Building Links for the Week of May 19, 2024 -- Another in our weekly set of links from readers, our colleagues, and others with important ideas for our field.

- Crisis, Contradiction, Certainty, and Contempt -- Columbia Professor Peter Coleman, an expert on intractable conflict, reflects on the intractable conflict occurring on his own campus, suggesting "ways out" that would be better for everyone.

Get the Newsletter Check Out Our Quick Start Guide

Educators Consider a low-cost BI-based custom text .

Constructive Conflict Initiative

Join Us in calling for a dramatic expansion of efforts to limit the destructiveness of intractable conflict.

Things You Can Do to Help Ideas

Practical things we can all do to limit the destructive conflicts threatening our future.

Conflict Frontiers

A free, open, online seminar exploring new approaches for addressing difficult and intractable conflicts. Major topic areas include:

Scale, Complexity, & Intractability

Massively Parallel Peacebuilding

Authoritarian Populism

Constructive Confrontation

Conflict Fundamentals

An look at to the fundamental building blocks of the peace and conflict field covering both “tractable” and intractable conflict.

Beyond Intractability / CRInfo Knowledge Base

Home / Browse | Essays | Search | About

BI in Context

Links to thought-provoking articles exploring the larger, societal dimension of intractability.

Colleague Activities

Information about interesting conflict and peacebuilding efforts.

Disclaimer: All opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Beyond Intractability or the Conflict Information Consortium.

Beyond Intractability

Unless otherwise noted on individual pages, all content is... Copyright © 2003-2022 The Beyond Intractability Project c/o the Conflict Information Consortium All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced without prior written permission.

Guidelines for Using Beyond Intractability resources.

Citing Beyond Intractability resources.

Photo Credits for Homepage, Sidebars, and Landing Pages

Contact Beyond Intractability Privacy Policy The Beyond Intractability Knowledge Base Project Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess , Co-Directors and Editors c/o Conflict Information Consortium Mailing Address: Beyond Intractability, #1188, 1601 29th St. Suite 1292, Boulder CO 80301, USA Contact Form

Powered by Drupal

production_1

- education and training in Europe and in Hungary

- Our profile

- ESLplus - Nemzetközi szintű tudásmegosztással a korai iskolaelhagyás csökkentéséért

- CroCooS – Prevent dropout!

- Summary & Results

- Resource Pool

- Toolkit & Guidelines

Ask an Expert

Download tool.

Click on the Download button to get the tool in a PDF file, which you can print out easily

No lose conflict solving

Two main methods are highly recommended to use for solving conflicts in teacher-student relationships. One that is used in Gordon’s T.E.T. programs and the other is Nonviolent Communication (NVC). Both of these methods help to solve problems by keeping mutually satisfying relationship between partners.

What is common in these no-lose conflict solving methods is that

both are based on

- the value: both side’s wellbeing is of equal worth in a conflict,

- non-judgemental attitude, empathy (not sympathy nor antipathy) and

- certain skills: using active listening, and expressing I-Messages.

In what case do we prefer using Gordon’s model? If…

- there is only limited time

- it is possible to modify physical environment to prevent problems and conflicts

- it is important to decide who is the owner of the problem

- it is essential to recognize and avoid the 12 Communication Roadblocks

- the aim is to get a rule-setting process

- the emphasis is on the problem/conflict solving itself

How to use it?

The basic version of Gordon’s method is that first it needs to labelled who is the problem owner, then comes the 3 STEPS of communication:

- Non-judgemental description of the other’s behaviour (factual description of what happened without any adjectives)

- Expressing feelings (how did I feel as a result of the other’s actions)

- Identification of the tangible/concrete effect of the others’ behaviour on us (sentences that start with "This made me…")

In what case do we prefer using NVC? If…

- more time we have for understanding the roots of the conflict

- we would like to have/keep a meaningful deeper relationship

- we want to focus on the relationship between us (more therapeutic approach)

- we want to focus on one’s own needs and on the other’s as well

- having the knowledge, that everyone takes responsibility about her/his feelings

- the emphasis is on the process between us in the present

How to use NVC?

Briefly: Keep role changes (use empathic listening and expressing) as many times as needed to understand each other.

Using empathy and active listening (clarifying, questioning with NVC’s 4 steps) to listen to the other, and using 4 steps to express our inner world.

Applying the NVC’s 4 STEPS:

Observation of behaviour or events (without interpretation or evaluation being mixed in)

Expressing our feelings (avoid evaluating expressions)

Expressing our needs (NVC includes a literacy of human needs and a listed itinerary of basic universal needs)

- A clear specific request for connection or action (I-Messages, or Strategies)

Alternatively, there is another Gordon’s no-lose conflict solving method in 6 STEPS: When shell we use this model? If

- we are not or not much involved emotionally in the conflict (we have no specific feelings about the conflict or the people in it)

- The problem/conflict is of a materialistic type (the issue is not about different feelings, personalities but concrete actions or objects, like if two students need the only available laptop for use)

Step 1 :Identifying and Defining the Problem Together

Warning: your statements of the problem should be expressed in a way that does not communicate blame or judgment. I –messages are recommended.

Step 2: Generating Alternative Solutions

Both parts should be creative in generating possible solutions.

It’s important to avoid evaluation until a number of possible solutions are proposed.

Step 3: Evaluating the Alternative Solutions

It is important by this phase to take special care that both you and the other person are honest and use active listening.

Step 4: Choose a Solution

In this phase both people agree on a solution or combination of solutions. Someone needs to state the solutions to make sure that both agree. Don't try to push a solution - both should choose freely.

Step 5: Plan for and Take Action

In this step, you both decide Who does What by When to carry out the agreed-on solution. It's best to trust that both will do what they agreed on instead of talking about what will happen if they don't.

Step 6: Check Results

Both need to agree to check back at a later time to make sure the solution worked/is working for each of them.

User's guide, equipment:

- List of NVC universal needs

- NVC List of words for feelings

- List of 12 Communication Roadblocks of T.E.T.

How useful did you find it?

- All rights reserved 2014 © Tempus Public Foundation

Tempus Public Foundation • H-1077 Budapest, Kéthly Anna tér 1. • Phone: (+36 1) 237-1300 • Fax: (+36 1) 239-1329 • Infoline: (+36 1) 237-1320 • E-mail: [email protected]

On oktataskepzes.tka.hu we use cookies to give you the best possible experience. By using this website you accept cookies.

February 1, 2024

18 min read

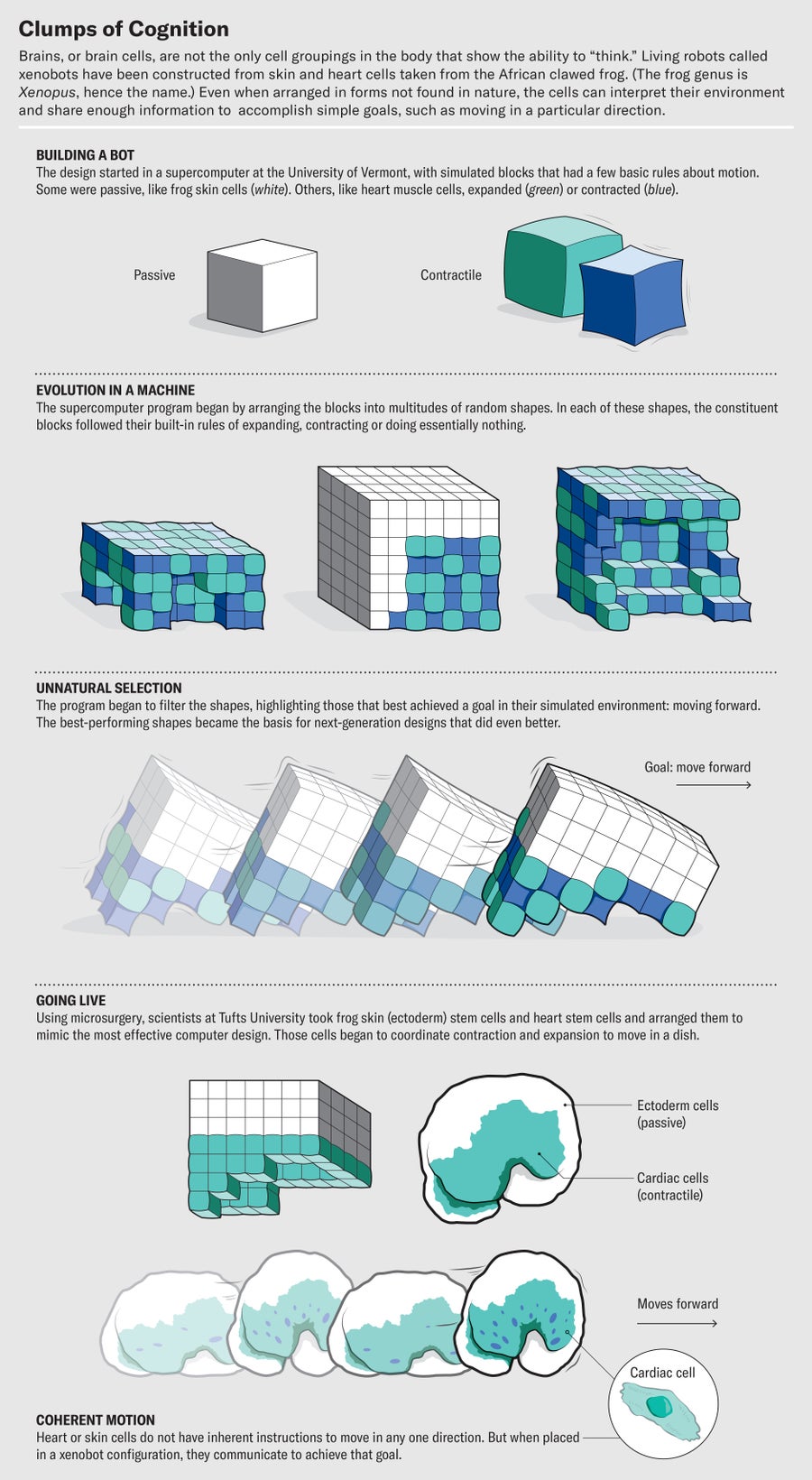

Brains Are Not Required When It Comes to Thinking and Solving Problems—Simple Cells Can Do It

Tiny clumps of cells show basic cognitive abilities, and some animals can remember things after losing their head

By Rowan Jacobsen

Natalya Balnova

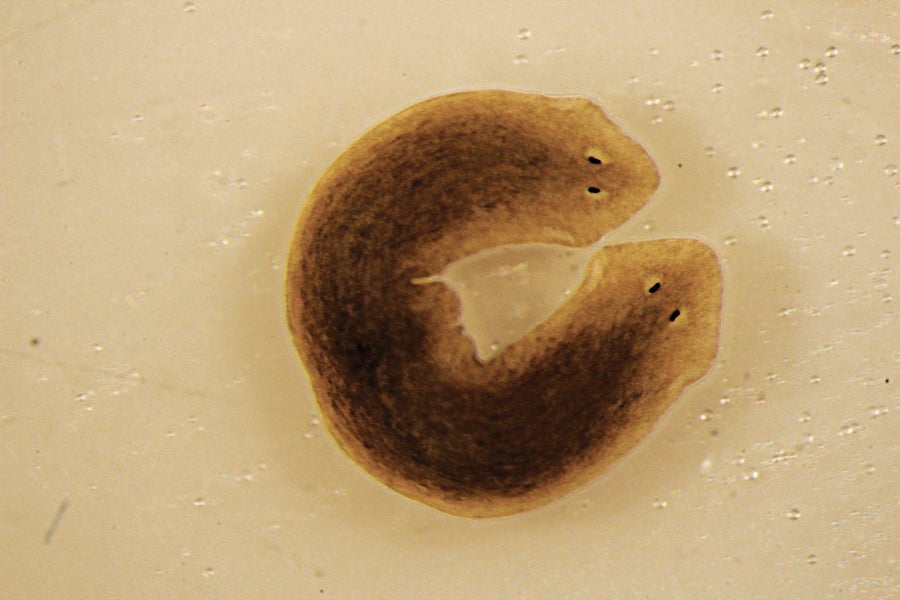

T he planarian is nobody's idea of a genius. A flatworm shaped like a comma, it can be found wriggling through the muck of lakes and ponds worldwide. Its pin-size head has a microscopic structure that passes for a brain. Its two eyespots are set close together in a way that makes it look cartoonishly confused. It aspires to nothing more than life as a bottom-feeder.

But the worm has mastered one task that has eluded humanity's greatest minds: perfect regeneration. Tear it in half, and its head will grow a new tail while its tail grows a new head. After a week two healthy worms swim away.

Growing a new head is a neat trick. But it's the tail end of the worm that intrigues Tufts University biologist Michael Levin. He studies the way bodies develop from single cells , among other things, and his research led him to suspect that the intelligence of living things lies outside their brains to a surprising degree. Substantial smarts may be in the cells of a worm's rear end, for instance. “All intelligence is really collective intelligence, because every cognitive system is made of some kind of parts,” Levin says. An animal that can survive the complete loss of its head was Levin's perfect test subject.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In their natural state planaria prefer the smooth and sheltered to the rough and open. Put them in a dish with a corrugated bottom, and they will huddle against the rim. But in his laboratory, about a decade ago, Levin trained some planaria to expect yummy bits of liver puree that he dripped into the middle of a ridged dish. They soon lost all fear of the rough patch, eagerly crossing the divide to get the treats. He trained other worms in the same way but in smooth dishes. Then he decapitated them all.

Levin discarded the head ends and waited two weeks while the tail ends regrew new heads. Next he placed the regenerated worms in corrugated dishes and dripped liver into the center. Worms that had lived in a smooth dish in their previous incarnation were reluctant to move. But worms regenerated from tails that had lived in rough dishes learned to go for the food more quickly. Somehow, despite the total loss of their brains, those planaria had retained the memory of the liver reward. But how? Where?