- Investment Areas

- Early Years

- Early Childhood Matters

- Annual Reports and ANBI

- Media library

- Netherlands

- Global displacement

Children growing up in Indian slums: Challenges and opportunities for new urban imaginations

The physical environments of slums present many challenges to residents, particularly children. Even so, there are thriving communities in slums with strong social and economic networks. This article looks at the reality of growing up in slums in Delhi, and explores how well-intentioned slum improvement efforts can fail children. It concludes by identifying ways in which India’s policy environment could support efforts to make slum improvement programmes more child-friendly.

Children growing up in slums experience a childhood that often defies the imagination of both the ‘innocent childhood’ proponents and the ‘universal childhood’ advocates. The slums typically lack proper sanitation, safe drinking water, or systematic garbage collection; there is usually a severe shortage of space inside the houses where the children live, and no public spaces dedicated to their use. But that does not mean that these children have no childhood, only a different kind of childhood that sees them playing on rough, uneven ground, taking on multiple roles in everyday life, and sharing responsibilities with adults in domestic and public spaces in the community.

Some years ago I spent a year working closely with and observing children in Nizamuddin Basti, an 800-year-old historic settlement in the heart of central New Delhi best known for its famous Sufi shrine, the Nizamuddin Dargah. This internationally renowned spiritual centre is also a prominent cultural and philanthropic institution for the community and the city. The Basti is now considered an urban village with a historic core and layers of slums on its periphery. A predominantly Muslim community, Nizamuddin Basti and its slums together comprise ten notional precincts. These precincts were first delineated by children who worked with the local NGO, the Hope Project, in a community mapping exercise; the ngo is using the map to develop strategies for the different precincts of the Basti, given the different profiles of their residents (long-term residents vs. new migrants, regional origin, language and customs, and professions).

Children were to be seen everywhere as one entered the Basti. They played in the parks that wrapped the Basti on the western side to hide it from the gaze of the city. They played on the rough ground and vacant lots dotted with graves, in the open spaces in the centre where garbage was manually sorted. The parked rickshaws, vending carts, cars and bikes all served as play props in the streets. As soon as they could walk, children could be seen outdoors walking around mostly barefoot, climbing on debris and petting goats that freely roamed around. Girls as young as 5 carried infants and toddlers on their hip and moved around freely in the narrow pedestrian bylanes of the village, visiting shops for sweets and the houses of friends down the street. Many houses open out directly onto the street through a doorway that often is nothing more than a 5-foot-high opening in a wall. Infants reach out of these holes in the wall and interact with passers-by.

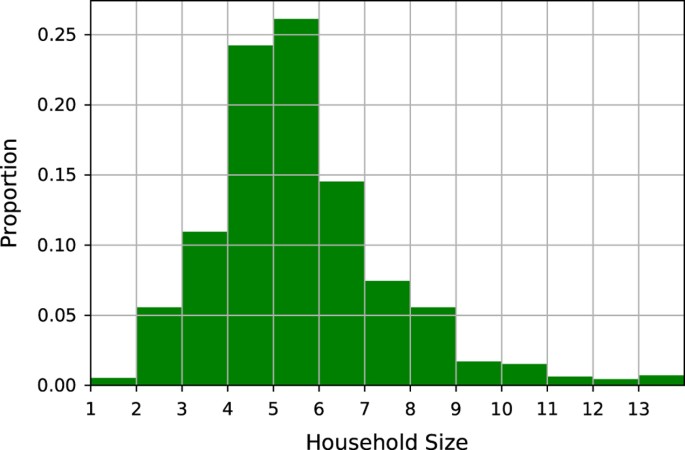

The Basti has an approximate population of 15,000, based on the counting done by the Hope Project 3 years ago. Since a major focus of the Hope Project’s admirable work was on health and education, I looked up the data on child health as recorded in the outpatient registers of the paediatric unit. Just over 5000 children aged under 14 years live in the Basti. For common ailments the majority of households visit the Hope Dispensary, with the next most commonly visited medical facilities being private doctors and government hospitals and dispensaries (Prerana, 2007). The most common childhood diseases reported at the Hope Project are respiratory diseases, diarrhoea, gastritis, intestinal worms, anaemia, scabies, and ringworm. An adverse living environment characterised by overcrowding, lack of ventilation in homes, and inadequate sanitation, water supply and water storage facilities no doubt contributes to the childhood diseases reported.

However, despite a largely unplanned physical environment, with debris and garbage generously strewn around, very few serious injuries occur in the public domain. Only a few superficial cuts were reported. I too had noticed that during my year-long observation in the Basti. In fact, the only accident I witnessed involved play equipment provided by the government in front of the municipal school.

The stories of Rani and Wahida

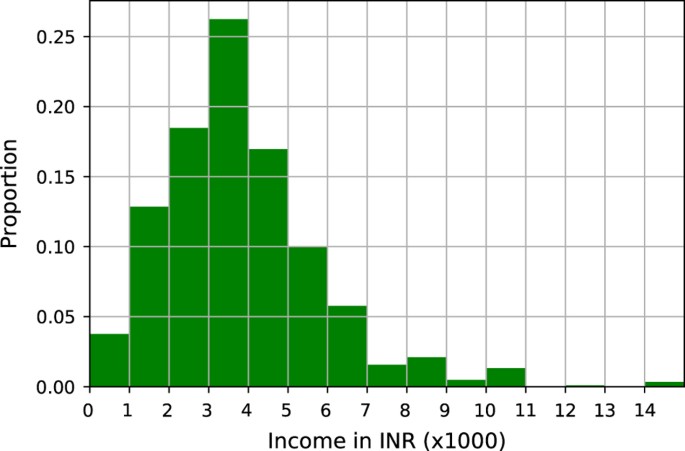

Rani’s family lived in one of the peripheral slums of the Basti called Nizam Nagar, one of the most deprived precincts and also the most crowded. The average monthly income of a family there barely exceeds 30 euros. Spread over about an acre, this informal housing accommodates 4458 people. Rani lived with her mother, two unmarried sisters and a married sister and her family in their two rooms arranged one on top of the other. The married sister occupied the top room. Half of the bottom room was occupied by a bed and the remaining floor space at the back was used for cooking, storage and for sitting around. The room had windowless walls on three sides and only opened onto the street in front. Rani’s mother had carved out a small shop selling cigarettes in the front of the room. There was no attached toilet or any piped water supply in this house.

When she was 11 years old, Rani kept a journal for me for a week, recording her day before she went to sleep. This account of her life provides some valuable glimpses about the multiple roles a girl child plays in this community. Rani was responsible for fetching milk for tea for her family every morning from Hasan Bhai’s tea stall. She would meet and chat with friends and neighbours here. In poor families such as hers, food is purchased on a daily basis, as there are no refrigerators for storing groceries.

Rani was a good practising Muslim. She washed herself in the morning and routinely offered all five prayers, or namaz, throughout the day. She called on her friend Meher, who lived around the corner, every morning and walked with her to the Hope Project’s non-formal school for adolescent girls. Rani performed daily household chores and shopping for the family, fetching cigarettes, snacks and groceries both for her mother’s shop and for home. Rani acted as guardian to her little niece, playing with her, feeding her, looking after her. She was a part-time shopkeeper, and sat in their small house-front shop to relieve her mother of her shopkeeping duties for some time every day.

Rani was a good student; other girls came to her for homework help. She bought sweets with small change, liked to play with domestic pets and with friends in the street in front of her house, in the nearby open spaces including the yard of the public toilet across from her house, in Meher’s back yard, and in the city park that was just outside the wall that separated her street from the park. Rani’s two older unmarried sisters took care of the cooking, cleaning and washing.

Rani had a friend called Wahida – unlike her, an orphan who had grown up in many households. Wahida split her time between the houses of her older siblings, her grandmother and her friend Rani’s family in Nizam Nagar. Her days were filled with household chores, besides attending the non-formal Hope school and evening religious studies. Wahida also attended a vocational training course in tailoring and sewing every afternoon in the community centre across from Nizam Nagar.

Both Rani and Wahida had grown up in severe poverty. Rani’s father had died of a drug overdose after reducing the family to penury. Rani’s mother barely earned a dollar a day from her shop and found it difficult to pay even the two rupees that would have bought Rani a hot lunch at school. Wahida had no one to watch over her and depended on charity for meals and a roof for the night. Yet both girls not only survived but thrived in this slum which represents one of the best examples of social capital in an urban neighbourhood. Seven years later, Rani and Wahida have both successfully completed school and are undergoing training as nursery teachers. Wahida is also working as an assistant to a city physiotherapist.

Slum redevelopment with children in mind

There are many such stories in Nizamuddin Basti that speak to the power of family and community social capital in aiding the well-being and future prospects of children. The many everyday places in Nizam Nagar and the larger Nizamuddin Basti that allow children like Rani and Wahida to be active social participants in everyday life are the stuff that communities are made of.

When families are driven out of their slums and taken by truckloads to a resettlement site, they are not only driven away from their homes but also from their communities. Sadly, this is the reality of how many cities are tackling slum renewal – notably Delhi, where families living in squatter settlements are routinely displaced from their squatter locations to make way for profitable new developments and are relocated to barren resettlement sites typically outside the city. Delhi has 44 such resettlement colonies, with a total population estimated to be 1.8 million (Government of Delhi, 2002). Less than 1% of the land occupied by squatters is privately owned (Kundu, 2004), implying that if there were political will, the state could easily provide adequate housing with secure tenure inside the city.

Most slum redevelopment assumes that overall slum improvement processes will automatically benefit children. This is unfortunately not always true. Even the best of initiatives that work on improving sanitation – such as through providing more public toilets, as is currently happening in Nizamuddin Basti – do not take children’s needs into account. Public toilets are scary places for children and with long adult queues, children have to wait a long time for their turn. These are reasons why children can often be seen to squat in the space outside the toilet block or in the street right outside their homes.

The new toilet blocks were part of a larger improvement plan in the Basti that did not adequately consider children. For example, the Basti improvement plan ostensibly benefited children by creating two new landscaped parks. One of them was exclusively for women and children, although it opened its secure gates for only a few hours in the evenings. (Recently a local NGO negotiated access at least once a week outside of the evening hours for children who are part of their programmes.) The other new park replaced a large, central open space in the heart of the community, which was used for sorting scrap. As most residents in the peripheral slums of the Basti depend on this business for a livelihood, the unavailability of this space meant sorting scrap at home. As a result, the home environment is now extremely hazardous for children. These kinds of problems result when communities are not made partners in development, and solutions instead come from a myopic outside view.

In Khirkee, another urban village in Delhi south of the Nizamuddin Basti, children living in a small slum cluster in neighbouring Panchshel Vihar had access to only one badly maintained park, even though the local area had several landscaped parks. When I asked 12-year-old Rinki, who was a play leader of the slum children, what sort of improvements she would recommend for the park, she told me, ‘Please don’t do anything otherwise we will not be able to play here any more.’ This poignantly sums up the attitude of the city. While in theory investment in parks is seen as benefiting children, in practice the temptation is to protect the newly beautified parks from slum kids, who are viewed as vandals. In some communities, slum children are actively evicted from parks, which defeats the purpose of providing them. Rules on park use also discourage imaginative play – when we observed children in landscaped, rule-bound parks that kept out slum children, we counted them playing 12 to 16 different games. In contrast, the slum children from Panchsheel Vihar were counted playing 34 different games in the badly maintained park in Khirkee.

Children use the public realm of neighbourhoods not only for playing but for many other activities including privacy needs and concealing secrets. This requires a range of spaces of different scales and character. Well-designed parks are no doubt very desirable for slum kids, but throughout the day more play happens in the streets and informal open spaces of the neighbourhood than in formal parks. Children in both Nizamuddin Basti and Khirkee referred to the importance of having friendly adults around their play territories, which tells us we need to create new, more imaginative solutions for children’s play than resource-intensive parks which inevitably become sites of conflict between different user groups.

Children from both communities routinely sought out open spaces in the local area outside their neighbourhoods. This points to the importance of integrating slums with the wider local area and securing access to open-space resources for slum children outside of the slum. The importance of community-level open spaces for children living in slums cannot be overemphasised. As there is little opportunity for innovation within the 12.5 m2of cramped private domestic space that Delhi slum dwellers are typically allocated, children in slums, including very small children, spend a large portion of their day outdoors. The cleanliness, safety and friendliness of the outdoor spaces in a slum thus play an important role in the health and well-being of children. Slum improvement plans will work better for children if we consider environmental improvements to the slum neighbourhood as a whole by involving children and by considering slums to be an integral part of the city.

The policy environment in India

India deals with slums only through poverty alleviation strategies. Since the 1980s, every Five Year Plan has included strategies targeting the environmental improvement of urban slums through provision of basic services including water supply, sanitation, night shelters and employment opportunities. But as urban slum growth is outpacing urban growth by a wide margin (UNDP, 2007), the living conditions of more than a 100 million urban slum dwellers in India remain vulnerable.

Is it possible to create a new imagination of slum development within the current policy environment of India? Following the liberalisation of India’s economy in 1991, two landmark events unfolded which may enable this:

- the 74th Constitutional Amendment of 1992, which proposes that urban local bodies (ULBs) should have a direct stake in urban poverty alleviation and slum improvement and upgrading, with participation of citizens, and

- the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM), launched in December 2005, which embodies the principles of the 74th Constitutional Amendment. jnnurm outlines a vision for improving quality of life in cities and promoting inclusive growth, through substantial central financial assistance to cities for infrastructure and capacity development for improved governance and slum development through Basic Services to the Urban Poor. These include security of tenure at affordable prices, improved housing, water supply, sanitation, education, health and social security.

In promoting an integrated approach to planned urban development and the provision of basic services to the urban poor, JNNURM can perhaps reduce some of the existing lapses in planning and service delivery and improve living conditions for the urban poor in a fairer manner. The Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation has recently launched the National Urban Poverty Reduction Strategy (2010–2020): ‘A New Deal for the Urban Poor – Slum Free Cities’, which adopts a multi-pronged approach to reducing urban poverty involving measures such as slum renewal and redevelopment (Mathur, 2009). This calls for developing Slum Free Cities plans for some 30 cities which have been selected for a ‘National Slum Free City Campaign’. None of the national policies on poverty has any focus on children’s well-being or development, however, or on slums as vibrant neighbourhoods that offer affordable housing to Indian citizens.

Slum Free Cities is operationalised through a government scheme called Rajiv Awas Yojana (RAY), using JNNURM support. RAY sees slum settlements as spatial entities that can be identified, targeted and reached through the following development options:

- slum improvement: extending infrastructure in the slums where residents have themselves constructed incremental housing

- slum upgrading: extending infrastructure in the slums along with facilitation of housing unit upgrading, to support incremental housing

- slum redevelopment: in-situ redevelopment of the entire slum after demolition of the existing built structures

- slum resettlement: in case of untenable slums, to be rehabilitated on alternative sites.

RAY provides detailed guidelines for spatial analysis and situation assessment and recommends a participative process, involving slum communities with the help of ngos and community-based organisations active in the area of slum housing and development, to identify possible development options. Slum Free Cities provides an opportunity for new thinking, as well as posing a problem to municipalities and ngos who may not have the technical knowledge and imagination to create innovative community-driven solutions.

As the well-being of children – in terms of health, nutrition, education and protection – is closely connected to the quality of physical living environments and to the delivery of and access to services, children must be central to slum improvement programmes. Slum improvements funded by jnnurm should be used to make Indian cities child-friendly, and build on the assets of intricate social networks, inherent walkability and mixed uses which are considered by new planning theories to be vital in making neighbourhoods sustainable (Neuwirth, 2005; Brugman, 2009).

Slum Free Cities planning guidelines already incorporate many elements that could secure children’s right to an adequate standard of living, such as secure tenure, improved housing, reliable services and access to health and education. However, intentions are often not translated into action. Children’s direct participation in local area planning and design for slum improvements would be a good step forward in creating child-friendly cities in India. Action for Children’s Environments (ACE) is currently working on a study supported by the Bernard van Leer Foundation to understand how the first phase of JNNURM-funded slum improvements have affected children, with the aim of informing these policies and improving the practice of planning and implementation of projects to make slum redevelopment more child-friendly.

References can be found in the PDF version of this article .

Also in this edition of Early Childhood Matters

Please note that “slum-dweller” as used in this piece is not intended to be offensive and is intended only to refer to individuals living in housing lacking proper sanitation, drinking water, and transportation facilities.

Introduction:

Due to rapid urbanization and lack of a proper housing scheme in India, slums have become a dumping ground for the surplus urban population. These slums are regarded as illegal from the point of view of city planners. The total number of slums in India amount to more than 65 million , of which around 11 million are in Maharashtra, followed by Andhra Pradesh, West Bengal, and Uttar Pradesh. These slums lack basic amenities, such as safe drinking water and sanitation.

In order to remove these slum dwellers, the government authorities resort to “forced evictions”, which results in serious violation of their human rights. This article is an attempt to analyze the rights of these slum dwellers.

Previous approach regarding the Human Rights of Slum Dwellers:

The accumulation of a large population in a small area (slums) with an inhabitable infrastructure leads to the inadequate distribution of resources among the people making them more vulnerable and ultimately leading to the infringement of human rights. Living in slums leads to a lack of proper sanitation, clean drinking water, and transportion facilities. Slum-dwellers often face poor economic conditions and thus have little power to oppose big companies who often encroach on their rights.

Most slums are located on the government’s land. Evictions from this land used to take place without even providing alternate housing to the slum dwellers leaving them to live at road paths with no other option. The court’s decisions would often favor the government and disregard the serious human rights violations the slum dwellers would face. But more recently, as more non-profit organizations have begun spreading awareness of human rights violations, the trend has started to change.

International Stance

Human Rights are termed as the “basic parameters” which assure the integrity of individuals are met for their overall development and that their rights will be protected against the more powerful entities. The section of society that is most vulnerable to having their rights infringed upon is the poorer section, which works in an unorganized sector and lives in a self-made informal structure, also known as slums. To provide more adequate housing, several treaties, laws, and legislations have been laid by several different nations.

The major laws that deal with the protection of slum dweller’s human rights are:

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights ( UDHR ) : Article 25 of UDHR states that every individual has a right to a satisfactory standard of living, along with the enjoyment of clothing, food, and medical care. Special care is to be taken of women and children. It also covers the right to security in the event of unemployment. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights ( CESCR ): Article 11 of the CESCR recognizes the right of adequate housing to everyone with a focus on continuous improvement in living conditions. It also ensures the right to remain free from hunger (identified as a fundamental right) for every individual and commands the state to take adequate measures to ensure that these rights are not infringed. The International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families – Article 43 in the convention discusses the right to access housing of migrant workers and their families. It also provides them protection against rent exploitation. The Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees – Article 21 states that the most possible and favorable atmosphere is to be provided to refugees along with other adequate and basic requirements.

The Convention on the Rights of the Child – Article 27 states that appropriate measures should be taken to provide adequate housing, clothing and nutrition along with material assistances and support programs.

The primary goal each of these regulations is to provide shelter and immunity against encroachment on basic human rights of the aggrieved population.

The largest problem of slums arises in the densely populated states or the under-developed states lacking the resources to provide accommodations in habitable atmospheres to their economically deprived community. Some of the largest slums in the world are located at Khayelitsha in Cape Town, South Africa with 400,000 inhabitants, Kibera in Nairobi, Kenya with 700,000 inhabitants and Dharavi in Mumbai, India: 1,000,000 – all of which fall under the above-mentioned criteria.

Apart from the legislation, there are several governmental and non-governmental organizations, such as UN-Habitat and GPRBA , which deal with the issues in slums and provide alternate shelter to dwellers.

Indian approach towards securing the rights of Slum Dwellers:

The Supreme Court of India has held that the right to life of human beings is not limited to mere animal existence and extends to the right to live with human dignity, including shelter, clothing, nutrition. The Court has also interpreted the right to be a fundamental rights guaranteed under Article 19(1)(e) and 21 of the Indian Constitution .

There is no specific law in India that deals with the removal of slums. For the purpose of eviction, the government resorts to laws dealing with property and cleanliness, which are distinct from forced eviction laws. Also, none of the provisions from the Public Premises Act or the Land Acquisition Act discuss the forced eviction of slum dwellers.

The Supreme Court of India declared in Ratlam Municipal Council vs. Vardichand that ensuring the public health of slum dwellers is the statutory duty of municipal corporations. The Court has also recognized the slum dweller’s right to life is not limited to a mere roof over their heads, but extends to the right to water, food, education, medical care, and sanitation. The question of whether the forced eviction of slum dwellers is a human rights violation came before the Supreme Court in Olga Tellis v. Bombay Municipal Corpn , where the Court held that eviction would amount to the violation of the right to life, and although Article 21 of the Indian Constitution does not give slum dwellers the absolute right to reside anywhere, the eviction process should be just, fair and reasonable and the dwellers must be relocated to other suitable places.

Conclusion:

There is a need for a shift in perception regarding slum dwellers when it comes to town-planning. The international obligations regarding the rights of slum dwellers must be followed in order to prevent human rights violations. It must not be forgotten that the slum dwellers, who constitute major part of the population, are human beings and should be provided the basic amenities of life, as well as resources to be able to contribute towards the economy. The problems faced by slum dwellers must be solved by the government with the help of long-term solutions. More non-governmental and governmental organizations must come forward to eradicate this issue and protect the human rights of slum dwellers.

Milind Rajratnam is currently in his second year at Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University, Lucknow. He takes an active interest in Criminal Law and Constitutional Law. He is associated with various organizations that work for creating legal awareness in the society.

Shivang Yadav is currently in his third year at Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University, Lucknow. He is interest in international relations and has been a part of multiple projects relating to international criminal Law and international humanitarian law.

Suggested citation: Milind Rajratnam and Shivang Yadav, Slums in India: Tracing the Contours of Human Rights Obligations, JURIST – Student Commentary, April 23, 2020, https://www.jurist.org/commentary/2020/04/Rajratnam-Yadav-slums-human-rights/

This article was prepared for publication by Gabrielle Wast , Assistant Editor for JURIST Commentary. Please direct any questions or comments to her at [email protected]

Supreme court overturns racially restrictive covenants

On May 3, 1948, the Supreme Court ruled that racially-restrictive covenants violate the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, even covenants between private individuals. In Shelley v. Kraemer , the Court overturned a covenant among members of a neighborhood in St. Louis, Missouri that restricted home sales to only white families.

World Press Freedom day

May 3 is World Press Freedom Day . On May 3, 1845, Macon B. Allen, the first African American to practice law in the United States, was admitted to the Massachusetts bar. Learn more about Allen's admission.

- Search Menu

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

17 The Political Construction of Slums in India

Nandini Gooptu is a Fellow of St Antony’s College, Oxford, and teaches at the Department of International Development. Educated in Kolkata and at Cambridge, she is the author of The Politics of the Urban Poor in Early-Twentieth-Century India ; editor of Enterprise Culture in Neoliberal India ; and joint editor of India and the British Empire and Persistence of Poverty in India . Her current research is concerned with social and political transformation and cultural change in contemporary India, particularly in the realm of work.

- Published: 16 August 2023

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The slum in India is a relational concept, brought into being through actions of the state and non-state actors, who create specific forms of knowledge about the slum, imbuing it with multiple meanings and attributes. The colonial construction of slums as insanitary sites of disease contagion and as spatial aberrations consisting of debased humanity were further elaborated in postcolonial India, with the changing dynamics of nationalism, development, and democratic politics as well as class conflict over rights to the city. Slum populations have been variously portrayed as criminal, illegal interlopers in the city who undermine democratic politics, as multitudinous consumers of scarce urban resources, as reckless polluters who degrade urban life and thwart both urban and national development, yet worthy of benevolent ministrations of the state and elites. The idea of the slum has been at the heart of struggles over the nation and the city, spatially, ideologically, and politically.

“A Slum, for the purpose of Census, has been defined as residential areas where dwellings are unfit for human habitation by reasons of dilapidation, overcrowding, faulty arrangements and design of such buildings, narrowness or faulty arrangement of street, lack of ventilation, light, or sanitation facilities or any combination of these factors which are detrimental to the safety and health.” 1 This approach by the Census of India 2011 gives the slum a spatial definition as a bounded and physically identifiable entity, characterized by deficiencies in its physical environment. This essentialized and reductionist characterization of the slum overlooks its multiple connotations and meanings that are created through political discourse and practice, as the following two, very different, examples illustrate.

On October 2, 2014, the birthday of Mahatma Gandhi, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched a highly orchestrated national campaign to create a “clean India” ( Swachh Bharat ) by wielding a broom to sweep dirt in Valmiki Basti, a slum in Delhi where Gandhi once stayed. The slum was projected as deserving of the virtuous ministrations of the enlightened, welfarist state and of an altruistic nationalist leadership imbued with civic virtue. It served as the ethical locus around which the government sought to galvanize the nation for developmental action to eradicate filth, animated by a spirit of morally charged social improvement associated with Gandhi as a national icon.

In contrast to Modi’s attention to the environment of the slum, its residents are highlighted on the website of the property development firm of Mukesh Mehta, best known for his controversial and highly disruptive and destructive plan for the commercial redevelopment of Mumbai’s Dharavi district, Asia’s largest slum: “The failure [of slum development policies so far] lies in not harnessing the spirit of a group of people that can and will act as an engine for economic growth. If slum-dwellers are treated as valuable human resources, they can act as a key stone to a vibrant and robust economy anywhere.” 2 The website then goes on to explain that unsanitary conditions, high incidence of disease, and the lack of educational and sociocultural infrastructure retard the realization of the full potentials of slum-dwellers as productive agents. Mehta, a private real-estate developer who made a fortune by building luxury homes, now describes himself as a social entrepreneur, and he justifies his lucrative slum reconstruction project and strategy of capital accumulation by invoking slums as repositories of entrepreneurial talent and the home of a potentially productive human resource.

These examples draw attention to the slum as a relational concept brought into being through the actions and interventions of the state and non-state actors. These interactions create specific forms of knowledge about the slum that are integrally linked with the economic and political life of the city and the nation. Slums are imbued with multiple meanings and attributes through struggles over the control, identity, and imaginaries of the city as well as through the dynamics of wider national politics. If one accepts that the slum is a socially and politically constructed category, it becomes worthwhile to eschew empirical enquiry into the condition of slums in India in order to explore their production through political and social discourse over time, and to trace the historical evolution of the slum as a concept in the colonial and postcolonial periods. This approach does not imply that the physical spaces described as slums do not exist in reality and are mere figments of imagination. On the contrary, an analysis of the conceptual development and the construction of slums through political and social discourse reveals wider urban struggles, conflicts, and inequalities that slums represent in a microcosm. As such, this analytical perspective explains why slums have proved to be so durable in India and come to signify the negative features of the urban condition. Moreover, a historically informed and contextualized enquiry into the social and political construction of slums helps to explain the local iterations of some widely prevalent global ideas about slums. It reveals the specificity and local roots of apparently similar characterization of slums across many parts of the world.

Sanitation, Poverty, and Colonial Power

Slums were first identified as an urban problem in colonial India in the later nineteenth century. Approaches to them were largely shaped by analogy with similar developments in Britain in the same period. 3 Major colonial cities like Calcutta and Bombay witnessed the influx of laboring populations, with an attendant overcrowding in under-developed areas that lacked proper housing, sanitary infrastructure, and planned roads and often consisted of informal settlements and dilapidated buildings. The identification of such areas as slums and as a major challenge of municipal governance arose out of colonial concerns with disease epidemics and the consequent preoccupation with sanitation, public health, and the safety of British troops and personnel. Colonial sanitary and municipal officers recognized the need to construct sanitary infrastructure and suitable housing. However, the lack of resources at the disposal of municipal authorities as well as the fear of unleashing urban political unrest after the country-wide uprising of 1857 against the British, prevented large-scale investment on infrastructure and the wholesale re-planning of cities. 4 Instead, the focus was on slums as habitats of the poor, who were considered responsible for causing unsanitary conditions due to their unhygienic habits and behavior.

Some of the most durable characterizations of the slum emerged from this period, as public health issues assumed overwhelming urgency during the outbreak of disease epidemics, such as the cholera, and most importantly, the plague in the 1890s. As historian Prashant Kidambi has argued in relation to Bombay, colonial officials ignored emerging scientific evidence of the microbial, rather than the miasmic, origin of the plague, and instead approached the plague through a contagionist lens as an “infection of locality” that could spread to white areas and affect Indian elites. 5 Consequently, they sought to tackle the plague through a spatialized approach, targeting areas identified as unsanitary, overcrowded, and prone to breeding disease.

As a result, the characterization of slums took on two enduring features. First, slums as unsanitary spaces were seen as localized phenomena without reference to the wider social, economic, and political factors responsible for the production of what had come to be seen as plague spots. In fact, the term “plague spot” gradually came not only to refer to areas affected by the plague, but also to signify poor hygiene, sanitation, and health as well as congestion, dirt, squalor, and filth. The outcome was the identification of the slum as a distinct type of urban space that caused disease contagion, the solution to which lay in localized interventions. Second, the culpability for the problem was placed squarely on the shoulders of those who lived in the slums, notably the poor. Irrespective of the actual composition of their populations, slums came to be synonymous with poverty and low life. In this way, the urban spatial politics of slums and control of the poor would become a critical facet of the exercise of biopower as a mode of imposing colonial rule in India.

Civic Nationalism and Elite Control of Cities

In the early decades of the twentieth century, and the interwar period in particular, slums came to be held responsible for jeopardizing not only the physical morphology and public health of the city but also its body politic and social fabric. The context for this shift in the conception of the slum was set by two sets of development that exacerbated class tensions in many rapidly growing cities: first, urban demographic expansion with migration of the poor into cities and overcrowding, and second, the increasing political mobilization and action of the urban poor through nationalist, religious, and caste politics in urban India, eliciting concerns and political unrest among Indian elites and the colonial state alike.

As the habitat of the growing number of the poor, slums came to be associated not only with squalor, but also with morally degraded life and a political threat. In north India, where urban population growth was particularly striking with in-migration of laboring classes, the insalubrious living conditions of the poor were identified by Raj Bahadur Gupta in 1930 as the factor that “lie[s] at the root of the characteristic inefficiency, slothfulness and other short-comings” of the poor. 6 An enquiry report on urban labor in the city of Kanpur in north India held the opinion that “the only relief available to the worker from the dirt and squalor of his house and its surroundings … is the liquor shop or the grog shop.” 7 Not surprisingly, the transformation of slums as the physical environment of the poor through improvement projects and slum clearance campaigns came to assume a central place in urban local policies.

This trend was further fortified by the emergence of a new form of civic nationalism among Indian elites, who were newly ensconced in town halls from the early decades of the twentieth century. 8 The colonial state had devolved the powers of local administration to Indian elites, who were to be elected by property-owning rate payers. For these new municipal elites and their propertied middle-class electorates, local institutions afforded them access to political and administrative power within the framework of the colonial state, in which they were otherwise disempowered. With their newfound power at the helm of urban affairs, these elites envisioned the city as a vehicle of nationalist modernization, progress, and order to be planned and organized under their enlightened leadership. 9 Their nationalist urbanism and economic and political predilections came to shape urban policy, notably the need of their middle-class electorate to find safe and hygienic residential areas. Municipal bodies began to replan and remold cities to expand into new areas for middle-class housing. Private investment on middle-class housing was spurred on by high rents, the opening up of new land for building construction by local authorities, and the redirection of capital from the countryside to investment on urban real estate from the time of the agrarian depression of the 1930s.

Slums were anathema to this optimistic and expansive urban vision of orderly modernity. Local bodies began to demolish or relocate slums to urban outskirts, leading to the spatial segregation of slum populations. This process was underpinned by a new moral discourse about the adverse impact of environment on character and behavior and about the interplay of dirt and degeneracy in slums, in addition to preexisting concerns about public health and sanitation. Slums, thus, came to be framed in terms of a dualistic conception of the city along the lines of class, with formally planned, well-developed areas of the well-off as the norm and informal, unwholesome spaces of the poor as the aberration.

Yet, at the same time, a nationalist vision of a common purpose of social reform and mass anti-colonial mobilization animated the nationalist leadership, thus making possible an alternative view of slums as areas deserving of benevolent attention for improvement. Patrick Geddes, the highly influential town planner, who was warmly welcomed by Indian elites in this period to develop plans of urban development, contributed to this approach by emphasizing a constructive and inclusive approach to slums. A high-profile pageant that he organized during a religious festival in the city of Indore represented this exalted mission of urban development. The festival procession, organized on the occasion of Diwali (the festival of light to usher in the new year) and well known across India in nationalist circles, depicted the war on slums, dirt, and disease as a shared social mission. Not only eminent citizens but also the lower castes featured in the event as key actors, with untouchable sweepers appearing in pure white clothing, carrying their brooms and bedecked with garlands to celebrate their contribution to urban cleansing. 10 In this way, an ambiguous and contradictory approach to slums came into existence, with a binary framing of their negative impact on cities on the one hand, and their need for benign reform on the other.

State Authoritarianism and Class Conflict

The dual approach of slum clearance and slum improvement, initiated during the late colonial period, continued into the early years after independence, until a much more accelerated and intensive phase of the onslaught on slums emerged in the 1970s, with new implications for the concept of the slum and its political significance. In 1975, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declared a state of internal “Emergency” to deal with what she saw as the outbreak of political movements and unrest that destabilized and threatened the state. Democratic processes were suspended and civil liberties were curbed during this authoritarian interlude in Indian politics between 1975 and 1977.The Emergency period has gained notoriety for hitherto unseen violence on urban slums across the country and the wholesale destruction and displacement of many slums in major cities. The high authoritarianism of the Emergency was played out on the body and habitat of the slum poor. As Patrick Clibbens argues, the Emergency removed any inhibition and impediment to a full-scale onslaught on slums by putting central emphasis on a uniform urban policy. 11

The attack on slums was also a manifestation of rising class tensions, and slum demolition reflected increasing middle-class anger and hostility toward the poor. In the period immediately preceding the Emergency, Gandhi had launched a populist campaign, claiming to eradicate poverty. She undertook a number of policy initiatives that were ostensibly for the benefit of the poor. Indeed, she proclaimed the Emergency in the name of the common people of India whose interests she purported to represent and advance. On the one hand, Gandhi invoked the poor not only to legitimize her authoritarian populism or authoritarian republicanism, but also to justify draconian slum clearance measures. On the other hand, this rhetorical political emphasis on the poor served to create an image of Gandhi as a leader who failed to uphold the interests of the middle classes, not least because the early and mid-1970s and Gandhi’s regime coincided with a period of economic problems affecting the middle classes, with high levels of unemployment, inflation, and an agrarian crisis.

All this had fueled middle-class discontent and at times, fed into political unrest. Moreover, Gandhi’s populist electoral mobilization imparted the poor hitherto unprecedented visibility in electoral politics and conveyed a mistaken impression of their growing power and agency in politics. In this context, slums, as the most easily identifiable residential concentration of the poor multitude, came to represent spaces that endanger the proper functioning of democracy and middle-class interests. Underpinned by middle-class support, large-scale, often brutal and violent, initiatives of slum clearance as well as fertility control of the poor through forced sterilization of men were rolled out in this period across India, and notably in Delhi. 12 Many of these campaigns are attributed to Sanjay, Gandhi’s son, who was at the helm of the youth wing of the Congress Party that is associated with disgruntled middle-class urban youth, venting their anger through public violence.

Clibbens’s study of Delhi during the Emergency further shows that policies to remove and relocate slums to the urban periphery and the poor to the margins of the city aimed at an elitist cultural regeneration and revival in the city, in order to rectify what was seen as the rise of debased plebian public culture. Jagmohan, lieutenant governor of Delhi, who presided over slum clearance, said that he aspired to achieve a “revolution of the mind” and a new civic consciousness as well as a new aesthetic of the city that would remove the putatively unaesthetic presence of slums of the poor from the heart of the city. Elaborating on his vision of Delhi, Jagmohan explained: “I have often believed in the destiny of this city, in its historic role, in its being a spiritual workshop of the nation, in its capacity to impart urbanity and civility to the rural migrant…. The real problem of the slums is not taking people out of slums but slums out of people.” 13 The Emergency unambiguously cast legitimate urban aesthetics and civic life in terms of the superior preferences and priorities of elites and the middle classes, with slums of the poor being marked as illegitimate anomalies that were to be subjected to a civilizing mission and to be excised from the city, due to their degraded culture and lack of civic virtue. This echoed similar elite propensities during the late colonial period, but a common nationalist purpose of an earlier era to solve the problem of slums gradually gave way to a more explicit class polarization, which would be further hardened in the following decades.

New Urbansim and the Middle Classes

Following the excesses of the Emergency and after the restoration of democracy, the intensity of slum clearance campaigns abated for some time and in situ slum development became the main thrust of slum policy. However, matters changed with the liberalization and globalization of the Indian economy from the early 1990s and into the early decades of the twenty-first century. This period is marked by the acceleration of urbanization, increasingly lucrative investment in urban real estate and an intensified struggle over the urban built environment as well as the unabashed expression of hostility against slums by a culturally and socially ascendant and aspiring middle-class. Historical constructions of the slum have fed into present-day policies and practices, and new approaches to slums have emerged as cities are reimagined as instruments of economic globalization and modernization and as sites of a middle-class consumer revolution, lifestyle enhancement, and upward social mobility. With the emergence of a new economic nationalism, the early years of the twenty-first century have elicited most intense nationwide controversy over slums.

Extensive slum demolition started taking place in the early 2000s. P. Sainath, a journalist, put into perspective the physical scale, demographic magnitude, and human cost of slum demolition in Mumbai (previously called Bombay) in December 2004 and January 2005: “Number of homes damaged by the tsunami in Nagapattinam [the worst-affected coastal district in southern India]: 30,300; Number of homes destroyed … in Mumbai: 84,000.” 14 With the full backing of the local state’s coercive powers and extensive public support in the city, an estimated three hundred thousand people were displaced in this slum clearance drive alone. This particular spate of demolitions eventually stopped when the national government in Delhi instructed the local government in Mumbai to exercise restraint for fear of alienating slum electorates. This immediately led to a public outcry against the government, and party politics more generally, for capitulating to electoral considerations, instead of resolutely stamping out the problem of slums.

Delhi did not lag far behind Mumbai in demolitions. As in Mumbai, citizens’ groups and residents’ associations of private middle-class housing colonies in Delhi mounted concerted anti-slum campaigns from the 1990s. They appealed to the local authorities and the law courts through public interest petitions to remove slums and squatter settlements in order to cleanse the city. In February and April 2004, with the help of armed police, more than 150,000 people were violently evacuated from the Pushta colony in Delhi, along the river Yamuna, to develop and “beautify” the area into a recreational promenade. The experience in other major Indian cities, such as Kolkata, Ahmedabad, Bangalore, Hyderabad, and Chennai, were not quite so catastrophic, but all witnessed middle-class citizen activism against slums and often their removal, affecting several million people.

The onslaught on slums and the related urban land grab have been analytically understood in terms of the growing importance of real estate as an important site of private investment since the 1990s, when the Indian economy began to be gradually liberalized. The urban building boom from the turn of the century is also driven by rising demands from India’s burgeoning middle class and the private corporate sector. The geographer Swapna Banerjee-Guha argues that urban land is now the key instrument of capital accumulation. 15 This has led to a process of displacement of slums and dispossession of the poor from valuable urban space and prime real estate, often through force and coercion, in order to reconfigure the built environment for exclusive use by the privileged and the well-off. Beyond this economic rationale, the reconceptualization of the role of slums is also underpinned by new visions of the city that emerged from the turn of the century. One of India’s most high-profile entrepreneurs of a globally successful IT company, later turned politician, has argued that the city has come to take the place of the village as the quintessence of a “new” India. 16 Similarly, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, while launching a major, nationwide urban development program on December 3, 2005, stated: “Our urban economy has become an important driver of economic growth. It is also the bridge between the domestic economy and the global economy. It is a bridge we must strengthen.”

The centrality of the city in India’s growth economy has found expression in the oft-repeated official aspiration to transform Mumbai into Shanghai, and more widely to create global cities in India. Indeed, it now seems axiomatic in the Indian state and corporate circles to envision the city as the engine of economic growth, the beacon of India’s future and the crucible of enterprise and innovation. This spirit of economic nationalism and urban optimism was reflected in the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM), India’s largest ever and most ambitious urban regeneration program, launched in 2005, driven by a shared government and private corporate imperative to transform cities. 17 This economic nationalist and entrepreneurial urbanism has been further elaborated with a techno-modern civic imagination more recently, with the launch of the Smart Cities Mission in 2015 for a technology-led enhancement and management of urban infrastructure and resources. 18

The city has also been reimagined by the increasingly assertive and consumerist middle and upper classes. The past few decades of the liberalization and globalization of the Indian economy have witnessed the crystallization of a new passionate commitment by the Indian elites and middle classes to the idea of economic growth, enterprise, and consumption. As is widely recognized, political ideas have hardened against the redistributive policies of an earlier era and against what is now widely perceived to be the pro-poor orientation of India’s post-independence developmental state, which is held responsible for undermining capitalist development and prosperity.

The sociologist Satish Deshpande has argued that middle-class visions of nationalism have come to be focused on an imagined economy defined by consumption. He states: “cosmopolitan consumption (rather than the patriotic production of Nehruvian socialism) appears to be the preferred terrain for the national imagination associated with India’s globalized capitalist economy.” 19 The middle classes as sovereign consumers have focused specifically on cities as not only the symbols of the new imagined economy but also the site of fulfilment of consumer identity. Urban prosperity and modernity are at the heart of this vision. The cliché of urban shopping malls as the icons of a globalizing India does indeed capture this buoyant middle-class mood. The middle classes now view the city in terms of privatized enclaves and spaces, from which the poor are sought to be excluded, as evident from the rise of a vast private security system to protect spaces of consumption, leisure, work, and housing for the exclusive use of these classes. Sanjay Srivastava refers to the consumer-citizen whose identity is now rooted to private spaces of consumption. 20 “Bypass urbanism” 21 now characterizes Indian cities, with new residential areas being fortified within gated spaces and constructed away from the perceived filth and squalor of the poor and bypassing congestion and overcrowding, most notably in slums.

These middle and upper classes have also staked their prior claim to urban citizenship and privileged entitlement to the city through myriad forms of civic activism and “social municipalism” 22 that also seek to exclude the poor and outlaw the slum. An opportunity for this urban stakeholder activism has been afforded by the institutional reengineering of urban local governance to elicit the participation and involvement of citizens, as stakeholders, in the management of local services in partnership with municipal institutions. In particular, urban residents have been given greater autonomy to form local associations in their neighborhoods to mobilize local resources for service delivery. In response, Residents Welfare Associations (RWA) have been formed in many India cities, but overwhelmingly in affluent and middle-class areas. In contrast, local units of municipal governance and representative institutions in slums and other settlements of the poor are largely defunct or paper organizations, or only engaged in limited activities. This is despite the fact that some of these, such as ward committees (wards are the primary units of local governance) are mandated by law and have a statutory status. In comparison, RWAs have been highly activist, for local residents possess the skills and resources to fulfil their role as active citizens. In Delhi, for instance, RWAs implement neighborhood security arrangements, manage local infrastructure and services, such as drinking water and sanitation, and maintain roads, parks, community halls, and street lights. 23

In addition, RWAs have emerged as vociferous campaigners for the right of the privileged and the denial of the rights of the poor. As they are given direct access to municipal councils, they have the capacity to corner existing resources at the cost of poorer neighborhoods. The poor are seen to contribute little to the resource base of the city compared to tax-paying, property-owning citizens, while putting intolerable and unsustainable pressure on urban infrastructure, thus thwarting the modernization and environmental upgrading of cities. Indeed, resonating with enduring tropes of the unhygienic propensities of the poor, they are now seen to contribute to an environmental crisis in the city, consisting of overcrowding, congestion, insanitation, and pollution, thus imperiling the health and lifestyle aspirations of the upper and middle classes.

In contrast to the supposedly public-spirited, active citizens of RWAs, the poor are seen as irresponsible and parasitic on the city, thus being undeserving of any right to the city and devoid of any legitimate claim to urban citizenship status. In tune with this zeitgeist of new urbanism, RWAs have mounted concerted campaigns to protect and insulate putatively superior residential areas from the incursion of the poor as well as to remove slums and squatter settlements away from the city. All this has fueled a strident new environmentalism among the upper and middle-classes, focused on the “brown agenda” of protecting and enhancing the quality of the built environment for citizens’ well-being. Public spaces have been privatized and wrested from occupation by the poor for “beautification” and environmental and aesthetic upgradation, reminiscent of earlier eras of urban development in the colonial, early postcolonial and Emergency periods.

Strident campaigns have also been taken to the courts through public interest litigation for the removal of slums and to enforce the rights of the upper and middle classes to a high quality of life in the city, unencumbered by squatters or slum-dwellers. The Indian judiciary has often upheld and conferred legitimacy to these dominant middle-class and elite dispositions toward the slum for the supposed economic and social havoc wreaked in cities by slum-dwellers. The hostile attitude toward slum-dwellers has been fortified by judicial activism and by marked shifts in judicial rulings in favor of the middle classes and against slums and squatter settlements. 24 In 1986, the Supreme Court gave a landmark verdict in the Olga Tellis case, upholding the right of pavement dwellers to occupy public land to earn their livelihood, under Article 21 of the Constitution that guarantees Right to Life. In striking contrast, in 2000 and 2002, in two widely known judgements in the Almrita Patel and Pitampura-Manchanda cases, respectively, the courts ruled decisively in favor of residents of private middle-class housing estates in Delhi, whose quality of life was argued to be detrimentally affected by a plethora of “nuisance” perpetrated by nearby squatter settlements. In the Almrita Patel case, the Supreme Court judgment was unequivocal about the illegal status, and consequently the attenuated citizenship rights, of slum people, by stating that “rewarding an encroacher on public land with a free alternative site is like giving a reward to a pickpocket.” 25

In the second (Pitampura-Manchanda) case, the Delhi High Court verdict held: “The welfare of the residents of these [private housing] colonies is also in the realm of public interest which cannot be overlooked…. The welfare, health, maintenance of law and order, safety and sanitation of these residents cannot be sacrificed and their right under Article 21 is violated in the name of social justice to the slum-dwellers.” 26 These judgments lent formal authority and legal endorsement, not only to government action against slum-dwellers and squatters, but also to a public mood of contempt, abhorrence and outrage against the urban poor, as vociferously expressed by residents associations, and as stridently articulated in large swathes of the media.

In tune with these court judgements, slum residents are viewed as pathological lawbreakers who not only illegally occupy public land but also have a more general criminal and immoral disposition. A sense of moral panic appears to have gripped the middle and upper classes, with a fear that the proliferation of urban crime, emanating from the slums, would cause anything from theft and burglary to large-scale violence, and imperil the lives of law-abiding citizens. Thus, for example, in 2008 a citizens’ organization filed a court case against squatter colonies in Delhi and stated in its petition:

in the process of sponsoring, motivating and encouraging the setting up of these unauthorized, and subsequently, regularized colonies, the interests of the underprivileged persons do not really get served; they are encouraged to act illegally and to gain from such illegal acts; their moral fabric gets undermined; … these measures inevitably generate an atmosphere of crime … and a general lowering of the standards of morals. 27

The outlawing of slums as illegitimate spaces also represents a significant backlash against the increasing political democratization of the urban poor. Slums are seen as a threat, not simply because of their putative illegal occupation of space, but also because of the apparent power of slum residents in urban electoral politics. It is now amply documented that the 1980s and 1990s were characterized by a democratic, electoral participatory upsurge of the poor and lower orders. 28 The increasing electoral participation of the poor in urban politics and their political assertiveness have triggered an “elite revolt,” to use the formulation of Stuart Corbridge and John Harriss, 29 in the form of upper and middle-class denial of the legitimacy of democratic politics as being increasingly driven by the perverse imperatives of electoral mobilization of the multitudinous poor.

This particular idea has manifested itself in the form of an outpouring of righteous civic opposition to so-called “vote bank” politics that is believed to thrive in the slums, and the supposed capacity of slum-dwellers as squatters to lay illegal claims to urban land as well as to demand various undeserved rights and entitlements—all on the back of electoral politics as mobilized voters. A subject of intense political controversy and contention is the concept of the slum “cut-off date,” which would allow certain slums established before a particular year to be granted legal status, or to be “regularized,” while focusing demolition efforts on settlements that appeared after the “cut-off date.” The slum “cut-off date” has become the most powerful signifier of the putative capacity of slum residents to manipulate their electoral clout to gain recognition of what is seen as their entirely illegal and unfounded claim to urban settlement and citizenship.

Thus, in obvious support of slum demolitions in Mumbai in 2005, a journalist condemned “the sea of slum-dwellers who have taken root in Mumbai and who are encouraged and protected by political parties of every hue as they provide a huge catchment area of votes.” 30 In a related vein, a report shows that in 2004, “11 prominent Maharashtrians moved the Bombay High Court to bar slum-dwellers from voting” and in 2005, “the city’s Municipal Corporation itself asked the Chief Electoral Officer to drop residents of demolished slums from the voters’ lists.” The mentality behind these demands was interpreted in this report as follows: “the Indian poor have the audacity to believe that their votes can change things…. take away their votes. That should teach them they cannot live among us.” 31

At the present juncture then, slums are seen as the key spatial concentration, variously, of criminal, immoral, and illegal interlopers in the city, of irresponsible and multitudinous consumers of scarce and vital urban resources and of reckless polluters who degrade the quality of urban life and thwart both urban and national development. Slums are, therefore, now framed through a highly charged and emotive cleavage between the “outsider” or “alien” versus the “insider” or “citizen-resident” of the city.

Politics of the Urban Poor

The action and agency of slum-dwellers themselves also shape wider understanding of slums, while the exigencies of mass electoral politics force exclusionary urban ideologies to be tempered. Precisely at the time of an intensely exclusionary approach toward slums, an increasingly and highly mobilized popular electorate in a mass democracy has rendered it politically inexpedient to mount a wholesale attack on slums. Within an increasingly strong democratic culture of the poor and their electoral democratic upsurge, slum-dwellers have developed contested urban imaginaries and forged a variety of forms of political action and engagement to claim their own rights, entitlements, services, and territories.

The terms “occupancy urbanism” and the “dynamic ground up city” in the critical analytical literature describe the myriad ways in which the poor challenge and subvert urban elite policy and politics and shape the aesthetics of the city. 32 These have an impact on discursively reshaping space and reimagining the city, even though the ability of such politics from below to affect major shifts in urban policy remains limited. Nevertheless, these forms of subaltern urbanism in slums and “chronic street level subversion” 33 of policies represent the political agency of the poor that can scarcely be ignored or marginalized by the government and political parties, and it requires the hostility toward slums to be reined in. A war on slums could unleash significant political instability and unmanageable violence, posing a far greater threat to life and property than slums otherwise do. Veena Das and Michael Walton argue that it is “in the process of engaging the legal, administrative, and democratic resources that are available to them—in courts, in offices of the bureaucrats, and in the party offices—that the poor learn to become political actors.” 34 Through these forms of action, the slum poor assert their legal and moral right to live in the city and articulate their vision of inclusive cities. In this way, the poor have made it impossible to treat slums as unmitigated and irredeemable negative spaces, and have wrested the right for slums to be represented in a positive light and to attract developmental attention of both the state and middle and upper classes. In this context, a rhetoric of inclusion of slums and slum-dwellers has taken shape, as in the examples of the prime minister and a real estate developer construing slums and slum-dwellers as morally deserving of support.

This inclusive orientation has taken many different developmental and political forms. The provision and improvement of basic services for the poor in slums was a key component of JNNURM, India’s largest-ever urban renewal project. 35 For the delivery and embedding of such developmental programs, participatory forms of governance have been promoted at the local level to involve slum-dwellers, with greater or lesser degrees of effective implementation in actual practice in different places. However, these institutional arrangements for the involvement of slum-dwellers in local governance have created the channels of transactional, patron-client relationships between politicians and local residents. Various studies show how slum-dwellers are located in networks of urban political patronage. 36

Not only politicians, but also a large variety and number of NGOs now work among slum-dwellers for the provision of local services as well as for poverty alleviation. The NGOs, at times, assist slum-dwellers to resist draconian slum demolition policies and to ensure adequate rehabilitation, relocation, and alternative housing for displaced populations. Some commentators have seen NGO action in aid of slums as a form of deepening of democracy on behalf of the poor that also enables the articulation of development alternatives. 37 Others, however, argue that they fail to represent the interests of their constituents adequately and help to buttress government policy. 38 Indeed, the action of NGOs as well as the operation of patron-client linkages in slums have been critically assessed, variously for disciplining the political assertion of slum-dwellers, containing political energy within slums, muting the political expression of the slum poor, and casting them in a supplicant mode vis-à-vis the state as denizens rather than citizens. 39

Despite these limitations, popular politics in slums has undeniably drawn attention to inequality, neglect, and unjust deprivation, and thus given rise to a positive discourse and inclusive orientation that has even drawn in the otherwise hostile middle and upper classes to engage with slums through various kinds of voluntary developmental and charitable interventions, social enterprises, and NGO activism. These initiatives also represent the search for political agency and civic virtue by the middle classes, who have lost their faith in electoral democracy and eschewed party politics. Through a new culture of voluntarism that resonates with older traditions of social service associated with Gandhian nationalism, 40 these middle classes seek to assert their superiority and control over the slums, in an idiom of non-political or apolitical charity and welfarist philanthropy. Social-service-oriented involvement in slums, thus, enables middle-class self-constitution as political actors. These various forms of management of and intervention in politics in slums have served to reverse and complicate some of the hostile attitudes toward slums and have instead led to their construal as objects of reform and benevolent succor.

A further dimension of the positive orientation toward slums is the creation of the image of slum-dwellers as fundamentally entrepreneurial in disposition. Slum-dwellers are imagined to be adept at enterprise, supposedly due to their unparalleled resilience, coping ability, and capacity for frugal innovation ( jugaad in Hindi), in the face of the enduring adversity that they face in slums. This entrepreneurial image of slum inhabitants is in tune with current Indian economic nationalism and the much-vaunted image of India as the nation of entrepreneurs par excellence. Economic inclusion of slums through the mobilization of the entrepreneurial potentials of their inhabitants is now seen as an important element of the strategy of national economic growth, in line with prevalent global and national narratives of inclusive development. 41 This is evident from the extensive promotion of micro-credit, micro-enterprise, and self-help groups as a major plank of developmental intervention and poverty alleviation in slums. More broadly, with reference to the economic promise and profitable market potential of those at the bottom of the pyramid, slum populations and the vast informal economy of slums are sought to be integrated, or even adversely incorporated, into the wider economy through a boost to enterprise. Moreover, as is evident from the example of the property developer, Mukesh Mehta, the environment of slums is argued to stifle and constrain the supposedly innate entrepreneurial urge of slum populations, thus justifying the need to redevelop slums. The rhetoric of slum enterprise then paradoxically turns into an alibi for attacks on slums as a physical space endowed with negative characteristics, harking back to the abiding tropes that originated in the later nineteenth century under colonialism and that were reproduced repeatedly throughout the twentieth century.

The colonial imagery of slums in India as unsanitary, miasmic sites of disease contagion, and the late-colonial construction of slums as a spatial aberration consisting of debased humanity, were further extended and elaborated in postcolonial India with the changing dynamics of nationalism and national politics as well as class conflict over the right to the city and citizenship. New connotations of environmental degradation, illegality, and threat to democracy and development were attached to slums, while also construing slums as worthy of benevolent attention, in response, at least in part, to the assertion of political agency by slum-dwellers. It hardly bears stating that slum residents, their economic activities. and political engagement are all central to the very constitution of a city’s economy and polity. Slums supply labor and sustain the urban informal economy, while slum populations are arguably the mainstay of urban democratic politics. Yet slums in India continue to be seen as a problem, an imposition on the city and the source of many of its woes, sustained by myths and narratives of their fundamentally detrimental impact on the city. The idea of the slum has been at the heart of political conflict and contestation, and of struggles over the city and the nation, spatially, ideologically, and politically.

Dr C. Chandramouli, Registrar General and Census Commissioner, India, “Housing Stock, Amenities & Assets in Slums—Census 2011.” Powerpoint presentation, http://censusindia.gov.in/2011-Docuements/On_Slums-2011Final.ppt .

“Development Strategy,” cited on website of M M (Mukesh Mehta) Project Consultants Pvt Ltd., https://www.mmpcpl.com/development-strategy .

3. Christine Furedy , “Whose Responsibility: Dilemmas of Calcutta’s Bustee Policy in the Nineteenth Century,” South Asia 5, no. 2 (1982): 24–46 .

4. David Arnold , “Touching the Body: Perspectives on the Indian Plague, 1896–1900,” in Subaltern Studies V , edited by Ranajit Guha (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1988), 55–90 .

5. Prashant Kidambi , “‘An Infection of Locality’: Plague, Pythogenesis and the Poor in Bombay, c. 1896–1905,” Urban History 31, no. 2 (2004): 249–267 .

6. R. B. Gupta , Labour and Housing in India (Calcutta: Longmans, Green & Co., 1930): 64 .

Report of the Cawnpore [Kanpur] Labour Inquiry Committee, Chairman: Babu Rajendra Prasad (Allahabad, 1938): 420.

8. Prashant Kidambi , “From ‘Social Reform’ to ‘Social Service’: Indian Civic Activism and the Civilizing Mission in Colonial Bombay, c. 1900–1920,” in Civilizing Missions in Colonial and Postcolonial South Asia: From Improvement to Development , edited by Carey A. Watt and Michael Mann (London: Anthem Press, 2011), 217–239 ; Nandini Gooptu , The Politics of the Urban Poor in Early Twentieth-Century India (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 66–110 .

9. Helen E. Meller , “Urbanization and the Introduction of Modern Town Planning Ideas in India, 1900–1925,” in Economy and Society: Essays in Indian Economic and Social History , edited by K. N. Chaudhuri and Clive J. Dewey (Delhi and New York: Oxford University Press, 1979), 330–350 .

10. Philip Boardman , Patrick Geddes: Maker of the Future (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1944), 386–390 ; Philip Boardman , The Worlds of Patrick Geddes: Biologist, Town Planner, Re-Educator, Peace-Warrior (London: Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1978), 294–297 .

11. Patrick Clibbens , “‘The Destiny of this City is to be the Spiritual Workshop of the Nation:’ Clearing Cities and Making Citizens during the Indian Emergency, 1975–1977,” Contemporary South Asia 22, no. 1 (2014): 53–55 .

12. Emma Tarlo , Unsettling Memories: Narratives of the Emergency in Delhi (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003) .

Cited in Clibbens, “Destiny of the City,” 62 and passim.

14. P. Sainath , “The Unbearable Lightness of Seeing,” The Hindu , February 5, 2005 .

15. Swapna Banerjee-Guha , “Neoliberalising the ‘Urban’: New Geographies of Power and Injustice in Indian Cities,” Economic and Political Weekly 44, no. 22 (2009): 95–107 .

16. Nandan Nilekani , Imagining India: Ideas for the New Century (New Delhi: Allen Lane, Penguin Books India, 2008), 207–232 .

17. Darshini Mahadevia , “Branded and Renewed? Policies, Politics and Processes of Urban Development in the Reform Era,” Economic and Political Weekly 46, no. 31 (2011): 56–64 .

18. Ayona Datta , “Postcolonial Urban Futures: Imagining and Governing India’s Smart Urban Age,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space , online only (October 4, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775818800721 .

19. Satish Deshpande , “Imagined Economies: Styles of Nation-Building in Twentieth Century India,” Journal of Arts and Ideas nos. 25–26 (1993): 27 .

20. Sanjay Srivastava , “Urban Spaces, Post-Nationalism and the Making of the Consumer-Citizen in India,” in New Cultural Histories of India , ed. Partha Chatterjee , Tapati Guha Thakurta and Bodhisattva Kar (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2014) , ch. 13.

21. Rajesh Bhattacharya and Kalyan Sanyal , “Bypassing the Squalor: New Towns, Immaterial Labour and Exclusion in Post-Colonial Urbanisation,” Economic and Political Weekly 46, no. 31 (2011): 41–48 .

22. Janaki Nair , “‘Social Municipalism’ and the New Metropolis,” in Contested Transformations: Changing Economies and Identities in Contemporary India , ed. Mary John et al. (New Delhi: Tulika Books, 2006), 125–146 .

23. Debolina Kundu , “Elite Capture in Participatory Urban Governance,” Economic and Political Weekly 46, no. 10 (2011): 23–25 .

24. D. Asher Ghertner , “Analysis of New Legal Discourses behind Delhi’s Slum Demolitions,” Economic and Political Weekly 43, no. 20 (2008): 57–66 .

25. All these cases are cited in ibid .

26. Ibid .

27. Cited in Aman Sethi , “Some Home Truths,” Frontline , August 15, 2008, 38 .

28. Yogendra Yadav , “India’s Third Electoral System, 1989–99,” Economic and Political Weekly 34, nos. 34–35 (1999): 2393–2399 .

29. Stuart Corbridge and John Harriss , Reinventing India: Liberalization, Hindu Nationalism and Popular Democracy (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000) .

30. Siddharth Srivastava , “Mumbai Struggles to Catch Up with Shanghai,” Asia Times On-line , March 16, 2005, https://www.atimes.com/atimes/South_Asia/GC16Df02.html .

31. P. Sainath , “The Unbearable Lightness of Seeing,” The Hindu , February 5, 2005 .