- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Quick Facts

- The Northeast Plain

- The Changbai Mountains

- The North China Plain

- The Loess Plateau

- The Shandong Hills

- The Qin Mountains

- The Sichuan Basin

- The southeastern mountains

- Plains of the middle and lower Yangtze

- The Nan Mountains

- The Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau

- The Plateau of Tibet

- The Tarim Basin

- The Junggar Basin

- The Tien Shan

- The air masses

- Temperature

- Precipitation

- Animal life

- Ethnic groups

- Sino-Tibetan

- Other languages

- Rural areas

- Urban areas

- Population growth

- Population distribution

- Internal migration

- The role of the government

- Economic policies

- Farming and livestock

- Forestry and fishing

- Hydroelectric potential

- Energy production

- Manufacturing

- Labor and taxation

- Road networks

- Port facilities and shipping

- Posts and telecommunications

- Parallel structure

- Constitutional framework

- Role of the CCP

- Administration

- Health and welfare

- Cultural milieu

- Visual arts

- Performing arts

- Cultural institutions

- Daily life, sports, and recreation

- Media and publishing

- Archaeology in China

- Early humans

- Climate and environment

- Food production

- Incipient Neolithic

- 6th millennium bce

- 5th millennium bce

- 4th and 3rd millennia bce

- Regional cultures of the Late Neolithic

- Religious beliefs and social organization

- The advent of bronze casting

- Royal burials

- The chariot

- Late Shang divination and religion

- State and society

- Zhou and Shang

- The Zhou feudal system

- The decline of feudalism

- Urbanization and assimilation

- The rise of monarchy

- Economic development

- Cultural change

- The Qin state

- Struggle for power

- Prelude to the Han

- The imperial succession

- From Wudi to Yuandi

- From Chengdi to Wang Mang

- Dong (Eastern) Han

- The civil service

- Provincial government

- The armed forces

- The practice of government

- Relations with other peoples

- Cultural developments

- Sanguo (Three Kingdoms; 220–280 ce )

- The Xi (Western) Jin (265–316/317 ce )

- The Dong (Eastern) Jin (317–420) and later dynasties in the south (420–589)

- The Shiliuguo (Sixteen Kingdoms) in the north (303–439)

- Confucianism and philosophical Daoism

- Wendi’s institutional reforms

- Integration of the south

- Foreign affairs under Yangdi

- Administration of the state

- Fiscal and legal system

- The “era of good government”

- Rise of the empress Wuhou

- Prosperity and progress

- Military reorganization

- Provincial separatism

- The struggle for central authority

- The influence of Buddhism

- Trends in the arts

- Decline of the aristocracy

- Population movements

- Growth of the economy

- The Wudai (Five Dynasties)

- The Shiguo (Ten Kingdoms)

- Unification

- Consolidation

- Decline and fall

- Survival and consolidation

- Relations with the Juchen

- The court’s relations with the bureaucracy

- The chief councillors

- The bureaucratic style

- The clerical staff

- The rise of neo-Confucianism

- Internal solidarity during the decline of the Nan Song

- Song culture

- Invasion of the Jin state

- Invasion of the Song state

- Early Mongol rule

- Changes under Kublai Khan and his successors

- Foreign religions

- Confucianism

- Yuan China and the West

- The end of Mongol rule

- The dynasty’s founder

- The dynastic succession

- Local government

- Central government

- Later innovations

- Foreign relations

- Agriculture

- Philosophy and religion

- Literature and scholarship

- The rise of the Manchu

- Political institutions

- Social organization

- Trends in the early Qing

- The first Opium War and its aftermath

- The anti-foreign movement and the second Opium War (Arrow War)

- The Taiping Rebellion

- The Nian Rebellion

- Muslim rebellions

- Effects of the rebellions

- Foreign relations in the 1860s

- Industrialization for “self-strengthening”

- East Turkistan

- Tibet and Nepal

- Myanmar (Burma)

- Japan and the Ryukyu Islands

- Korea and the Sino-Japanese War

- The Hundred Days of Reform of 1898

- The Boxer Rebellion

- Sun Yat-sen and the United League

- Constitutional movements after 1905

- The Chinese Revolution (1911–12)

- Early power struggles

- Japanese gains

- Yuan’s attempts to become emperor

- Conflict over entry into the war

- Formation of a rival southern government

- Wartime changes

- An intellectual revolution

- Riots and protests

- The Nationalist Party

- The Chinese Communist Party

- Communist-Nationalist cooperation

- Militarism in China

- The foreign presence

- Reorganization of the KMT

- Clashes with foreigners

- KMT opposition to radicals

- The Northern Expedition

- Expulsion of communists from the KMT

- Japanese aggression

- War between Nationalists and communists

- The United Front against Japan

- Phase two: stalemate and stagnation

- Renewed communist-Nationalist conflict

- U.S. aid to China

- Conflicts within the international alliance

- Phase three: approaching crisis (1944–45)

- Nationalist deterioration

- Communist growth

- Efforts to prevent civil war

- Attempts to end the war

- Resumption of fighting

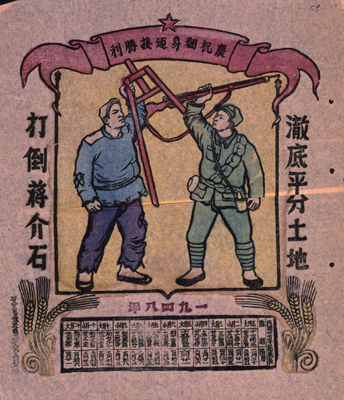

- A land revolution

- The decisive year, 1948

- Communist victory

- Reconstruction and consolidation, 1949–52

- Rural collectivization

- Urban socialist changes

- Political developments

- Foreign policy

- New directions in national policy, 1958–61

- Readjustment and reaction, 1961–65

- Attacks on cultural figures

- Attacks on party members

- Seizure of power

- The end of the radical period

- Social changes

- Struggle for the premiership

- Consequences of the Cultural Revolution

- Readjustment and recovery

- Economic policy changes

- Educational and cultural policy changes

- COVID-19 outbreak

- Allegations of human rights abuses

- International relations

- Relations with Taiwan

- Leaders of the People’s Republic of China since 1949

What are the major ethnic groups in China?

- Who was Mao Zedong?

- What is Maoism?

- How has China changed since Mao Zedong’s death?

- What is Mao Zedong's legacy?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- National Geographic Kids - 30 cool facts about China!

- Central Intelligence Agency - The World Factbook - China

- China - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- China - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

How big is China?

China, the largest of all Asian countries, occupies nearly the entire East Asian landmass and covers approximately one-fourteenth of the land area of Earth, making it almost as large as the whole of Europe.

China, which has the largest population of any country in the world, is composed of diverse ethnic and linguistic groups. The Han are the largest group in China, while the Zhuang is the largest minority group. In some areas of China, especially in the southwest, many different ethnic groups are geographically intermixed, including Buyi, Miao, Dong, Tibetans, Mongolians, and others.

Does China have an official language?

The official language of China is Mandarin, or putonghua , meaning “ordinary language” or “common language.” There are three variants of Mandarin—Beijing, Chengdu, and Nanjing. Of these, the Beijing dialect is the most widespread Chinese tongue and has officially been adopted as the basis for the national language.

How long has China existed as a discrete politico-cultural unit?

With more than 4,000 years of recorded history, China is one of the few existing countries that also flourished economically and culturally in the earliest stages of world civilization. China is unique among nations in its longevity and resilience as a discrete politico-cultural unit.

What crops are grown in China?

China is the world’s largest producer of rice and is among the principal sources of wheat, corn (maize), tobacco, soybeans, peanuts (groundnuts), and cotton.

China , country of East Asia . It is the largest of all Asian countries. Occupying nearly the entire East Asian landmass, it covers approximately one-fourteenth of the land area of Earth , and it is almost as large as the whole of Europe . China is also one of the most populous countries in the world, rivaled only by India , which, according to United Nations estimates, surpassed it in population in 2023.

China has 33 administrative units directly under the central government; these consist of 22 provinces , 5 autonomous regions, 4 municipalities ( Chongqing , Beijing , Shanghai , and Tianjin ), and 2 special administrative regions ( Hong Kong and Macau ). The island province of Taiwan , which has been under separate administration since 1949, is discussed in the article Taiwan . Beijing (Peking), the capital of the People’s Republic, is also the cultural, economic, and communications center of the country. Shanghai is the main industrial city; Hong Kong is the leading commercial center and port.

Recent News

Within China’s boundaries exists a highly diverse and complex country. Its topography encompasses the highest and one of the lowest places on Earth, and its relief varies from nearly impenetrable mountainous terrain to vast coastal lowlands . Its climate ranges from extremely dry, desertlike conditions in the northwest to tropical monsoon in the southeast, and China has the greatest contrast in temperature between its northern and southern borders of any country in the world.

The diversity of both China’s relief and its climate has resulted in one of the world’s widest arrays of ecological niches , and these niches have been filled by a vast number of plant and animal species. Indeed, practically all types of Northern Hemisphere plants, except those of the polar tundra, are found in China, and, despite the continuous inroads of humans over the millennia, China still is home to some of the world’s most exotic animals.

Probably the single most identifiable characteristic of China to the people of the rest of the world is the size of its population. Some one-fifth of humanity is of Chinese nationality. The great majority of the population is Chinese (Han), and thus China is often characterized as an ethnically homogeneous country, but few countries have as many diverse Indigenous peoples as does China. Even among the Han there are cultural and linguistic differences between regions; for example, the only point of linguistic commonality between two individuals from different parts of China may be the written Chinese language. Because China’s population is so enormous, the population density of the country is also often thought to be uniformly high, but vast areas of China are either uninhabited or sparsely populated.

With more than 4,000 years of recorded history , China is one of the few existing countries that also flourished economically and culturally in the earliest stages of world civilization. Indeed, despite the political and social upheavals that frequently have ravaged the country, China is unique among nations in its longevity and resilience as a discrete politico-cultural unit. Much of China’s cultural development has been accomplished with relatively little outside influence, the introduction of Buddhism from India constituting a major exception. Even when the country was penetrated by such foreign powers as the Manchu , these groups soon became largely absorbed into the fabric of Han Chinese culture .

This relative isolation from the outside world made possible over the centuries the flowering and refinement of the Chinese culture, but it also left China ill prepared to cope with that world when, from the mid-19th century, it was confronted by technologically superior foreign nations. There followed a century of decline and decrepitude, as China found itself relatively helpless in the face of a foreign onslaught. The trauma of this external challenge became the catalyst for a revolution that began in the early 20th century against the old regime and culminated in the establishment of a communist government in 1949. This event reshaped global political geography, and China has since come to rank among the most influential countries in the world.

Central to China’s long-enduring identity as a unitary country is the province, or sheng (“secretariat”). The provinces are traceable in their current form to the Tang dynasty (618–907 ce ). Over the centuries, provinces gained in importance as centers of political and economic authority and increasingly became the focus of regional identification and loyalty. Provincial power reached its peak in the first two decades of the 20th century, but, since the establishment of the People’s Republic, that power has been curtailed by a strong central leadership in Beijing. Nonetheless, while the Chinese state has remained unitary in form, the vast size and population of China’s provinces—which are comparable to large and midsize nations—dictate their continuing importance as a level of subnational administration.

China stretches for about 3,250 miles (5,250 km) from east to west and 3,400 miles (5,500 km) from north to south. Its land frontier is about 12,400 miles (20,000 km) in length, and its coastline extends for some 8,700 miles (14,000 km). The country is bounded by Mongolia to the north; Russia and North Korea to the northeast; the Yellow Sea and the East China Sea to the east; the South China Sea to the southeast; Vietnam , Laos , Myanmar (Burma), India , Bhutan , and Nepal to the south; Pakistan to the southwest; and Afghanistan , Tajikistan , Kyrgyzstan , and Kazakhstan to the west. In addition to the 14 countries that border directly on it, China also faces South Korea and Japan , across the Yellow Sea, and the Philippines , which lie beyond the South China Sea.

- AsianStudies.org

- Annual Conference

- EAA Articles

- 2025 Annual Conference March 13-16, 2025

- AAS Community Forum Log In and Participate

Education About Asia: Online Archives

Modern chinese history.

Two main themes run throughout Modern Chinese History . First, it emphasizes the role of foreign actors in China’s past. Cross-cultural contacts have deeply influenced the shape and trajectory of modern China. However, this text moves beyond the “impact-response” narrative, which outlines repeated conflicts with the superior West followed by China’s belated, inadequate responses. Not only is this narrative inaccurate and Eurocentric, it is also incomplete. Modern Chinese History emphasizes the importance of cross-cultural contacts but provides a more balanced approach to the topic. It includes encounters with the West, as well as interactions with China’s Asian neighbors. Second, this volume highlights the roles of domestic actors in China’s history, recognizing that these include far more than simply political and military elites. Modern Chinese History provides room for both men and women peasants, soldiers, and intellectuals to enter the stage of history.

Modern Chinese History provides room for both men and women peasants, soldiers, and intellectuals to enter the stage of history.

Whereas many scholars suggest modern China began during the mid-Qing period in 1840—the date of the Opium War and the beginning of the impact-response cycle—this work begins with the Qing dynasty (1644) and continues to the present day. Furthermore, rather than focusing primarily on twentieth-century events at the expense of earlier eras, roughly half the text covers the Qing period with the other half covering the Republican and Communist eras.

Several individuals will benefit from Modern Chinese History. Teachers of history, international studies, cultural studies, and Asian studies will find this text useful. Most notably, it will supplement the world history survey, which is becoming increasingly common on high school and college campuses. Even those colleges that have maintained the Western civilization survey will find this an appealing option, as instructors are emphasizing the West’s interaction with the larger world. Naturally, all types of Asian history classes will profit from this volume.

Modern Chinese History offers a succinct introduction to the political, economic, cultural, and social heritage of this powerful and influential nation. Because our students will increasingly interact with this region of the world, it is imperative they have a basic understanding of China.

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Latest News

- Join or Renew

- Education About Asia

- Education About Asia Articles

- Asia Shorts Book Series

- Asia Past & Present

- Key Issues in Asian Studies

- Journal of Asian Studies

- The Bibliography of Asian Studies

- AAS-Gale Fellowship

- Council Grants

- Book Prizes

- Graduate Student Paper Prizes

- Distinguished Contributions to Asian Studies Award

- First Book Subvention Program

- External Grants & Fellowships

- AAS Career Center

- Asian Studies Programs & Centers

- Study Abroad Programs

- Language Database

- Conferences & Events

- #AsiaNow Blog

Last updated 09/07/24: Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- < Back to search results

The Cambridge History of China

- Download list of titles

The Cambridge History of China is the largest and most comprehensive history of China in the English language. Planned in the 1960s by the late, distinguished China scholar Professor John K. Fairbank of Harvard, and Denis Twitchett, Professor Emeritus of Princeton, the series covers the grand scale of Chinese history from the 3rd century BC, to the death of Mao Tse-tung. Consisting of fifteen volumes (two of which, Volumes 5 and 9 are to be published in two books), the history embodies both existing scholarship and extensive original research into hitherto neglected subjects and periods. The contributors, all specialists from the international community of Sinologists, cover the main developments in political, social, economic and intellectual life of China in their respective periods. Collectively they present the major events in a long history that encompasses both a very old civilisation and a great modern power. Written not only for students and scholars, but with the general reader in mind, the volumes are designed to be read continuously, or as works of reference. No knowledge of Chinese is necessary; for readers with Chinese, proper names and terms are identified with their characters in the glossary, and full references to Chinese, Japanese, and other works are given in the bibliographies. Numerous maps illustrate the texts. The published volumes have constituted essential reading in Chinese history. See also, The Cambridge History of Ancient China, Michael Loewe and Edward Shaughnessy, eds., a companion to this series covering the period 1500 to 221 BC.

- General Editors: John K. Fairbank , Denis Twitchett

Refine search

Actions for selected content:.

- View selected items

- Save to my bookmarks

- Export citations

- Download PDF (zip)

- Save to Kindle

- Save to Dropbox

- Save to Google Drive

Save content to

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to .

To save content items to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service .

Save Search

You can save your searches here and later view and run them again in "My saved searches".

16 results in The Cambridge History of China

- Volume 2, The Six Dynasties, 220–589

- Edited by Albert E. Dien , Keith N. Knapp

- Published online: 28 October 2019 Print publication: 07 November 2019

- Get access Buy a print copy Check if you have access via personal or institutional login Log in Register

- Export citation

- View description The Six Dynasties Period (220–589 CE) is one of the most complex in Chinese history. Written by leading scholars from across the globe, the essays in this volume cover nearly every aspect of the period, including politics, foreign relations, warfare, agriculture, gender, art, philosophy, material culture, local society, and music. While acknowledging the era's political chaos, these essays indicate that this was a transformative period when Chinese culture was significantly changed and enriched by foreign peoples and ideas. It was also a time when history and literature became recognized as independent subjects and religion was transformed by the domestication of Buddhism and the formation of organized Daoism. Many of the trends that shaped the rest of imperial China's history have their origins in this era, such as the commercial vibrancy of southern China, the separation of history and literature from classical studies, and the growing importance of women in politics and religion.

- Volume 9, The Ch'ing Dynasty to 1800, Part 2

- Edited by Willard J. Peterson

- Published online: 05 April 2016 Print publication: 04 April 2016

- View description Volume 9, Part 2 of The Cambridge History of China is the second of two volumes which together explore the political, social and economic developments of the Ch'ing Empire during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries prior to the arrival of Western military power. Across fifteen chapters, a team of leading historians explore how the eighteenth century's greatest contiguous empire in terms of geographical size, population, wealth, cultural production, political order and military domination peaked and then began to unravel. The book sheds new light on the changing systems deployed under the Ch'ing dynasty to govern its large, multi-ethnic Empire and surveys the dynasty's complex relations with neighbouring states and Europe. In this compelling and authoritative account of a significant era of early modern Chinese history, the volume illustrates the ever-changing nature of the Ch'ing Empire, and provides context for the unforeseeable challenges that the nineteenth century would bring.

- Volume 5, Sung China, 960–1279 AD, Part 2

- Edited by John W. Chaffee , Denis Twitchett

- Published online: 05 March 2015 Print publication: 05 March 2015

- View description This is the second of two volumes on the Sung Dynasty, which together provide a comprehensive history of China from the fall of the T'ang Dynasty in 907 to the Mongol conquest of the Southern Sung in 1279. With contributions from leading historians in the field, Volume 5, Part Two paints a complex portrait of a dynasty beset by problems and contradictions, but one which, despite its military and geopolitical weakness, was nevertheless economically powerful, culturally brilliant, socially fluid and the most populous of any empire in global history to that point. In this much anticipated addition to the series, the authors survey key themes across ten chapters, including government, economy, society, religion, and thought to provide an authoritative and topical treatment of a profound and significant period in Chinese history.

- Volume 5, The Sung Dynasty and its Precursors, 907–1279, Part 1

- Edited by Denis Twitchett , Paul Jakov Smith

- Published online: 28 March 2010 Print publication: 23 March 2009

- View description This first of two volumes on the Sung Dynasty (960–1279) and its Five Dynasties and Southern Kingdoms precursors presents the political history of China from the fall of the T'ang Dynasty in 907 to the Mongol conquest of the Southern Sung in 1279. Its twelve chapters survey the personalities and events that marked the rise, consolidation, and demise of the Sung polity during an era of profound social, economic, and intellectual ferment. The authors place particular emphasis on the emergence of a politically conscious literati class during the Sung, characterized by the increasing importance of the examination system early in the dynasty and on the rise of the tao-hsueh (Neo-Confucian) movement toward the end. In addition, they highlight the destabilizing influence of factionalism and ministerial despotism on Sung political culture and the impact of the powerful steppe empires of the Khitan Liao, Tangut Hsi Hsia, Jurchen Chin, and Mongol Yüan on the shape and tempo of Sung dynastic events.

- Volume 9, Part 1, The Ch'ing Empire to 1800

- Published online: 28 March 2008 Print publication: 16 December 2002

- View description This volume of the Cambridge History of China considers the political, military, social, and economic developments of the Ch'ing empire to 1800. The period begins with the end of the resurgent Ming dynasty, covered in volumes 7 and 8, and ends with the beginning of the collapse of the imperial system in the nineteenth century, described in volume 10. Taken together, the ten chapters elucidate the complexities of the dynamic interactions between emperors and their servitors, between Manchus and non-Manchu populations, between various elite groups, between competing regional interests, between merchant networks and agricultural producers, between rural and urban interests, and, at work among all these tensions, between the old and new. This volume presents the changes underway in this period prior to the advent of Western imperialist military power.

- Volume 8, The Ming Dynasty, Part 2, 1368–1644

- Denis C. Twitchett , Frederick W. Mote

- Published online: 28 March 2008 Print publication: 28 January 1998

- View description Volumes seven and eight of The Cambridge History of China are devoted to the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), the only segment of later imperial history during which all of China proper was ruled by a native, or Han, dynasty. These volumes provide the largest and most detailed account of the Ming period in any language. Summarising all modern research, volume eight offers detailed studies of governmental structure, the fiscal and legal systems, international relations, social and economic history, transportation networks, and the history of ideas and religion, incorporating original research on subjects never before described in detail. Although it is written by specialists, this Cambridge History intends to explain and describe the Ming dynasty to general readers who do not have a specialised knowledge of Chinese history, as well as scholars and students. This volume can be utilised as a reference work, or read continuously.

- Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 907–1368

- Edited by Herbert Franke , Denis C. Twitchett

- Published online: 28 March 2008 Print publication: 25 November 1994

- View description This volume deals with four non-Chinese regimes: the Khitan dynasty of Liao; the Tangut state of Hsi Hsia; the Jurchen empire of Chin; and the Mongolian Yuan dynasty that eventually engulfed the whole of China. It investigates the historical background from which these regimes emerged and shows how each in its own way set up viable institutions for the control of a multi-racial, multi-lingual, and multi-cultural population. It discusses these problems not just as a long negative episode in China's history, but shows the ingenuity and adaptability of these states, and their success in achieving political and social stability. The volume presents the fullest chronological account of the period, in which political, institutional, social, and economic changes are integrated as far as possible, and sees the period against a broad background of international relations in Northern and Central Asia.

- Volume 15, The People's Republic, Part 2, Revolutions within the Chinese Revolution, 1966–1982

- Edited by Roderick MacFarquhar , John K. Fairbank

- Published online: 28 March 2008 Print publication: 29 November 1991

- View description Volume 15 of The Cambridge History of China is the second of two volumes dealing with the People's Republic of China since its birth in 1949. The harbingers of the Cultural Revolution were analyzed in Volume 14 and Volume 15 traces a course of events still only partially understood by most Chinese. It begins by analysing the development of Mao's thought since the Communist seizure of power, and, in doing so, attempts to understand why he launched the movement. The contributors grapple with the conflict of evidence between what was said favourably about the Cultural Revolution at the time and the often diametrically opposed retrospective accounts. Volume 15, together with Volume 14, provides the most comprehensive and clearest account of how revolutionary China has developed in response to the upheavals initiated by Mao and Teng Hsiao-p'ing.

- Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1

- Edited by Frederick W. Mote , Denis Twitchett

- Published online: 28 March 2008 Print publication: 26 February 1988

- View description This volume in The Cambridge History of China is devoted to the history of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), with some account of the three decades before the dynasty's formal establishment, and for the Ming courts that survived in South China for a generation after 1644. Volume 7 deals primarily with the political developments of the period, but it also incorporates background in social, economic, and cultural history where this is relevant to the course of events. The Ming period is the only segment of later imperial history during which all of China proper was ruled by a native, or Han, dynasty. The volume provides the largest and most detailed account of the Ming period in any language. Summarizing all modern research, both in Chinese, Japanese, and Western languages, the authors have gone far beyond a summary of the state of the field, but have incorporated original research on subjects that have never before been described in detail.

- Volume 14, The People's Republic, Part 1, The Emergence of Revolutionary China, 1949–1965

- Published online: 28 March 2008 Print publication: 26 June 1987

- View description This is the first of the two final volumes of The Cambridge History of China, which describe the efforts of the People's Republic of China to grapple with the problems of adaptation to modern times. Volume 14 deals with the achievements of the economic and human disasters of the new regime's first sixteen years (1949–65). Part I chronicles the attempt to adapt the Soviet model of development to China, and Part II covers the subsequent efforts of China's leaders to find native solutions that would provide more rapid and appropriate answers to China's problems. Each of the two parts of the volume analyzes the key issues and developments in the spheres of politics, economics, culture, education, and foreign relations. The contributors, all leading scholars of the period, show the interrelation of Chinese actions in all these spheres, and the describe how, gradually, events led to the Cultural Revolution launched by Mao Tse-tung in 1966.

- Volume 1, The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC–AD 220

- Edited by Denis Twitchett , Michael Loewe

- Published online: 28 March 2008 Print publication: 26 December 1986

- View description This volume begins the historical coverage of The Cambridge History of China with the establishment of the Ch'in empire in 221 BC and ends with the abdication of the last Han emperor in AD 220. Spanning four centuries, this period witnessed major evolutionary changes in almost every aspect of China's development, being particularly notable for the emergence and growth of a centralized administration and imperial government. Leading historians from Asia, Europe, and America have contributed chapters that convey a realistic impression of significant political, economic, intellectual, religious, and social developments, and of the contacts that the Chinese made with other peoples at this time. As the book is intended for the general reader as well as the specialist, technical details are given in both Chinese terms and English equivalents. References lead to primary sources and their translations and to secondary writings in European languages as well as Chinese and Japanese.

- Volume 13, Republican China 1912–1949, Part 2

- Edited by John K. Fairbank , Albert Feuerwerker

- Published online: 28 March 2008 Print publication: 24 July 1986

- View description This is the second of two volumes of this authoritative history which review the Republican period. The titanic drama of the Chinese Revolution is one of the major world events of modern times. The fifteen authors of this volume are pioneers in its exploration and analysis, and their text is designed to meet the needs of non-specialist readers. After a preliminary overview stressing economic and social history, the History presents a narrative of events in China's foreign relations to 1931, and in the political history of the Nationalist government and its Communist opponents from 1927 to 1937. Subsequent chapters analyse key governmental, educational and literary - offering critical appraisal of the major achievements and problems in each of these areas. Finally, the volume examines China's war of resistance, the civil war to 1949, and the portentous development of the thought of Mao Tse-tung before coming to power.

- Volume 12, Republican China, 1912–1949, Part 1

- Edited by John K. Fairbank

- Published online: 28 March 2008 Print publication: 30 September 1983

- View description This is the first of two volumes of this authoritative Cambridge history which review the Republican period, between the demise of imperial China and the establishment of the People's Republic. These years from 1912 to 1949 were marked by civil war, revolution and invasion; but also by change and growth in the economic, social, intellectual and cultural spheres. The chapters examine economic trends in the period and the rise of the new middle class. Intellectual trends are surveyed to show the changes in traditional Chinese values and the foreign influences which played a major role in Republican China. Although it is written by specialists, the goals and approach of this Cambridge history are to explain and discuss republican China for an audience which will include scholars, students and general readers who do not have special knowledge of Chinese history. It will be useful both as narrative history and as a reference source on the history and politics of China.

- Volume 11, Late Ch'ing, 1800–1911, Part 2

- Edited by John K. Fairbank , Kwang-Ching Liu

- Published online: 28 March 2008 Print publication: 30 September 1980

- View description This is the second of two volumes in this major Cambridge history dealing with the gradual decline of the Ch'ing empire in China (the first was volume 10). Volume 11 surveys the persistence and deterioration of the old order in China during the late nineteenth century, and the profound stirring during that period, which led to China's great twentieth-century revolution. The contributors focus on commercial and technological growth, foreign relations, the stimulation of Chinese intellectual life by the outside world, and military triumphs and disasters. They show that the effects of the accelerating changes were to fragment the old ruling class and the ancient monarchy, finally bringing the Chinese people face to face with the challenges of the new century. For readers with Chinese, proper names and terms are identified with their characters in the glossary, and full references to Chinese, Japanese and other works are given in the bibliographies.

- Volume 3, Sui and T'ang China, 589–906 AD, Part One

- Edited by Denis C. Twitchett

- Published online: 28 March 2008 Print publication: 27 September 1979

- View description The Cambridge History of China is one of the most far-reaching works of international scholarship ever undertaken, exploring the main developments in political, social, economic and intellectual life from the Ch'in empire to the present day. The contributors are specialists from the international community of sinological scholars. Many of the accounts break new ground; all are based on fresh research. The works are written not only with students and scholars but also with the general reader in mind. No knowledge of Chinese is assumed, though for readers of Chinese, proper and other names are identified with their characters in the index. Numerous maps and tables illustrate the text. Volume 3, covers the second great period of unified imperial power, 589–906, when China established herself as the centre of a wider cultural sphere, embracing Japan, Korea and Vietnam. It was an era in which there was a great deal of rapid social and economic change, and in which literature and the arts reached new heights of attainment.

- Volume 10, Late Ch'ing 1800–1911, Part 1

- Published online: 28 March 2008 Print publication: 05 June 1978

- View description This is the first of two volumes in this major Cambridge history dealing with the decline of the Ch'ing empire. It opens with a survey of the Ch'ing empire in China and Inner Asia at its height, in about 1800. Contributors study the complex interplay of foreign invasion, domestic rebellion and Ch'ing decline and restoration. Special reference is made to the Peking administration, the Canton trade and the early treaty system, the Taiping, Nien and other rebellions, and the dynasty's survival in uneasy cooperation with the British, Russian, French, American and other invaders. Each chapter is written by a specialist from the international community of sinological scholars. No knowledge of Chinese is necessary; for readers with Chinese, proper names and terms are identified with their characters in the glossary, and full references to Chinese, Japanese and other works are given in the bibliographies. Numerous maps illustrate the text, and there are a bibliographical essays describing the source materials on which each author's account is based.

Email your librarian or administrator to recommend adding this to your organisation's collection.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Art of Asia

Course: art of asia > unit 2, introduction to china.

- Imperial China, an introduction

- Archaeology and the study of ancient China

- Discoveries in Chinese archaeology

- Buddhist Temples at Wutaishan

- Chinese calligraphy, an introduction

- Decoding Chinese calligraphy

- Appreciating Chinese calligraphy

- Ascending the Heron Tower written in cursive script

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

In order to continue enjoying our site, we ask that you confirm your identity as a human. Thank you very much for your cooperation.

- Student Opportunities

About Hoover

Located on the campus of Stanford University and in Washington, DC, the Hoover Institution is the nation’s preeminent research center dedicated to generating policy ideas that promote economic prosperity, national security, and democratic governance.

- The Hoover Story

- Hoover Timeline & History

- Mission Statement

- Vision of the Institution Today

- Key Focus Areas

- About our Fellows

- Research Programs

- Annual Reports

- Hoover in DC

- Fellowship Opportunities

- Visit Hoover

- David and Joan Traitel Building & Rental Information

- Newsletter Subscriptions

- Connect With Us

Hoover scholars form the Institution’s core and create breakthrough ideas aligned with our mission and ideals. What sets Hoover apart from all other policy organizations is its status as a center of scholarly excellence, its locus as a forum of scholarly discussion of public policy, and its ability to bring the conclusions of this scholarship to a public audience.

- Peter Berkowitz

- Ross Levine

- Michael McFaul

- Timothy Garton Ash

- China's Global Sharp Power Project

- Economic Policy Group

- History Working Group

- Hoover Education Success Initiative

- National Security Task Force

- National Security, Technology & Law Working Group

- Middle East and the Islamic World Working Group

- Military History/Contemporary Conflict Working Group

- Renewing Indigenous Economies Project

- State & Local Governance

- Strengthening US-India Relations

- Technology, Economics, and Governance Working Group

- Taiwan in the Indo-Pacific Region

Books by Hoover Fellows

Economics Working Papers

Hoover Education Success Initiative | The Papers

- Hoover Fellows Program

- National Fellows Program

- Student Fellowship Program

- Veteran Fellowship Program

- Congressional Fellowship Program

- Media Fellowship Program

- Silas Palmer Fellowship

- Economic Fellowship Program

Throughout our over one-hundred-year history, our work has directly led to policies that have produced greater freedom, democracy, and opportunity in the United States and the world.

- Determining America’s Role in the World

- Answering Challenges to Advanced Economies

- Empowering State and Local Governance

- Revitalizing History

- Confronting and Competing with China

- Revitalizing American Institutions

- Reforming K-12 Education

- Understanding Public Opinion

- Understanding the Effects of Technology on Economics and Governance

- Energy & Environment

- Health Care

- Immigration

- International Affairs

- Key Countries / Regions

- Law & Policy

- Politics & Public Opinion

- Science & Technology

- Security & Defense

- State & Local

- Books by Fellows

- Published Works by Fellows

- Working Papers

- Congressional Testimony

- Hoover Press

- PERIODICALS

- The Caravan

- China's Global Sharp Power

- Economic Policy

- History Lab

- Hoover Education

- Global Policy & Strategy

- Middle East and the Islamic World

- Military History & Contemporary Conflict

- Renewing Indigenous Economies

- State and Local Governance

- Technology, Economics, and Governance

Hoover scholars offer analysis of current policy challenges and provide solutions on how America can advance freedom, peace, and prosperity.

- China Global Sharp Power Weekly Alert

- Email newsletters

- Hoover Daily Report

- Subscription to Email Alerts

- Periodicals

- California on Your Mind

- Defining Ideas

- Hoover Digest

- Video Series

- Uncommon Knowledge

- Battlegrounds

- GoodFellows

- Hoover Events

- Capital Conversations

- Hoover Book Club

- AUDIO PODCASTS

- Matters of Policy & Politics

- Economics, Applied

- Free Speech Unmuted

- Secrets of Statecraft

- Pacific Century

- Libertarian

- Library & Archives

Support Hoover

Learn more about joining the community of supporters and scholars working together to advance Hoover’s mission and values.

What is MyHoover?

MyHoover delivers a personalized experience at Hoover.org . In a few easy steps, create an account and receive the most recent analysis from Hoover fellows tailored to your specific policy interests.

Watch this video for an overview of MyHoover.

Log In to MyHoover

Forgot Password

Don't have an account? Sign up

Have questions? Contact us

- Support the Mission of the Hoover Institution

- Subscribe to the Hoover Daily Report

- Follow Hoover on Social Media

Make a Gift

Your gift helps advance ideas that promote a free society.

- About Hoover Institution

- Meet Our Fellows

- Focus Areas

- Research Teams

- Library & Archives

Library & archives

Events, news & press.

The Cycles—or Stages—of Chinese History

The logic of strategy and all that comes from it, including the idea of the “balance of power,” for example, is inherently universal, transcendental, and timeless, but each clan, tribe, nation, and state has its own peculiar political constructs—that is why seemingly homogeneous systems, for example parliamentary democracy, function in ways so radically different from country to country.

Equally, the elemental sense of the centrality of any polity takes very different forms, ranging from the quiet certitudes of the Kingdom of Denmark to that well-known Chinese construct, the Tianxia (whose logographs 天下 have been much seen in the Japanese press of late, their Kanji versions being identical). Literally “under heaven,” short for “all under heaven” or more meaningfully, “the rule of all humans,” it defines an ideal national and international system of ever-expanding concentric circles centered on a globally benevolent emperor, now Xi Jinping or more correctly perhaps, the seven-headed standing committee of the Politburo.

The innermost circle of the Tianxia is formed by the rest of the Politburo and top Beijing officialdom, while its outermost circle comprises the Solomon Islands along with the twenty or so other utterly benighted “outer barbarian” countries that still do not recognize Beijing, preferring Taipei. In between, all other Chinese from officials and tycoons to ordinary subjects and overseas Chinese fit in their own circles, further and further from the imperial coreas do foreign states both large and small, both near and far, both already respectful (too few) and those still arrogantly vainglorious. It is the long-range task of China’s external policy to bring each and every state into a proper relationship with the emperor—that is, a tributary relationship, in which they deliver goods and services if only as tokens of fealty, in exchange for security and prosperity, but even more for the privilege of proximity to the globally benevolent emperor 1 . All this is of course nothing more than an exceptionally elaborate rendition of universal ambitions that are merely grander for the greater—the Byzantine ranking of foreign potentates by their proximity to the emperor was only slightly less elaborate.

Nor is there anything peculiarly Chinese about the desire to bring other states into a tributary relationship—often better than a full incorporation, which may be unwanted for any number of reasons, and obviously superior to an alliance however close and secure but between equals, whereby there must be reciprocity, a quid for every quo, usually costly or irksome in some way. Hence from time immemorial, stronger clans, tribes, potentates, and entire nations have done their best to impose tributary relations on weaker clans, tribes, potentates and nations, obtaining goods and services for their forbearance and perhaps protection, or at least tokens of respectful subordination. Chinese emperors wanted no more than that, and unlike most recipients, not infrequently gave gifts more valuable than the tribute they received (as did many Byzantine emperors, by the way).

What is peculiar to China’s political culture, and of very great contemporary relevance is the centrality within it of a very specific doctrine on how to bring powerful foreigners—indeed foreigners initially more powerful than the empire—into a tributary relationship. Specialists concur that this doctrine emerged from the very protracted (3rd century BCE to 1st century CE) but ultimately successful struggle with the Xiongnú (匈奴) horse-nomad state, 2 just possibly remote ancestors of Attila’s Huns, but definitely the inventors of the Steppe State political system that would be replicated by all their successors, and more adapted than replaced even by the Mongols 3 .

Formidable mounted archers and capable of sustained campaigning (a primary objective of the Steppe State), the Xiongnú ravaged and savaged and extorted tribute from the perpetually less martial, and certainly cavalry-poor Han until the latter finally felt able to resist again. Even then, 147 years of intermittent warfare ensued until Huhanye (呼韓邪), the paramount Chanyu (Qagan, Khan) of the Xiongnú, personally and formally submitted to the emperor Han Xuandi in 51 BCE, undertaking to pay homage, to leave a son at court as a hostage, and to deliver tribute, as befitted a vassal. That was a very great downfall from the familial status of earlier Chanyus of the epoch of Xiongnú predominance, who were themselves recognized as emperors, whose sons and heirs could have imperial daughters in marriage, and who from 200 BCE had received tribute from the Han, instead of the other way around.

It is this successful transformation of a once superior power first into an equal (signified by imperial marriages) and then into a subservient client-state that seems to have left an indelible residue in China’s tradition of statecraft. It was achieved with a specific “barbarian-handling” tool box first described by its early practitioner, the scholar and imperial advisor Lou Jing (婁敬) 199 BCE. His method was first applied when the Xiongnú were still very strong and the Han were not only tactically inferior (their chariots were totally obsolete for fighting mounted archers) but also beset by political divisions, so much so that a 198 BCE 4 treaty required the payment of an annual tribute in kind (silk, grain, etc.), and the formal attestation of equality for the Chanyu embodied in a marriage alliance, formalized by imperial letters that make the equality fully explicit.

The first barbarian-handling tool is normally translated as “corruption” in English translations, but perhaps “addiction,” or more fully “induced economic dependence” are more accurate: the originally self-sufficient Xiongnú were to be made economically dependent on Han-produced goods, starting with silk and woolen cloths instead of their own rude furs and felt. At first supplied free as unrequited tribute, these goods could still be supplied later on when the Han were stronger, but only in exchange for services rendered.

The second tool of barbarian handling, is normally translated as “indoctrination”: the Xiongnú were to be persuaded to accept the authoritarian Confucian value system and the collectivistic behavioral norms of the Han, as opposed to the steppe value system, based on voluntary allegiance to a heroic (and successful in looting) fighting and migration leader. One immediate benefit was that once the Chanyu’s son and heir married an imperial daughter, he would be ethically subordinated to the emperor as his father-in-law—remaining so when he became Chanyu in turn.

The much larger, longer-term benefit of the second tool was to undermine the entire political culture of the Xiongnú, and make them psychologically well as economically dependent on the imperial radiance, which was willingly extended in brotherly fashion when the Han were weak, and then contemptuously withdrawn when the Xiongnú were reduced to vassalage. What happened between the Han and the Xiongnú from the equal treaty of 198 BCE to the vassalage treaty of 51 BCE, remained thereafter, and still remains today the most hopeful precedent for Han dealings with powerful and violent states—evidently the assigned role of the United States in the present Beijing world-view.

The method forms a logical sequence: Stage One: start by conceding all that must be conceded to the superior power including tribute, in order to avoid damage and obtain whatever forbearance is offered. But this in itself entangles the ruling class of the still-superior power in webs of material dependence that reduce its independent vitality and strength. Stage Two: offer equality in a privileged bipolarity that excludes all lesser powers, or “G-2” in current parlance. That neutralizes the still powerful Other party, and isolates the manipulated soon-to-be former equal from all its potential allies, preventing from balancing China with a coalition. Stage Three: finally, when the formerly superior power has been weakened enough, withdraw all tokens of equality and impose subordination.

Until the Chinese government decided—very prematurely I believe—to awaken the world to its classically imperial territorial ambitions by demanding the cession of lands, reefs, rocks, and sea waters from India, Japan, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam (demands that disturb and damage the concurrent Tianxia narrative of an alternative and more harmonious state system, disseminated even within the confines of Stanford University 5 ), it was making much progress towards Stage Two, the stage of equality preparatory to the final stage of subordination.

Of this progress—now interrupted, one may hope—one example suffices, though Zbigniew Brzezinski and Robert Zoellick among many others have expressed similar notions: at the end Dr. Henry Kissinger’s very widely read On China , after 526 pages of historical retrospectives and personal reminiscences, definite prescriptions are offered, summarized in the heading “Toward a Pacific Community,” i.e. a harmonious US-Chinese “G-2” that logically proceed from his relentlessly benign assessment of Chinese intentions. Dr. Kissinger’s G-2 is identical to that relationship very persistently advocated by Chinese officials high and low, and by senior advisors such as Zhen Bijian (郑必坚) of “Peaceful Rise” fame.

That Stage Two could be achieved only by persuading the still-powerful Other party to accept equality and its limitations , most notably the isolation of the soon-to-be former equal from all its potential allies, preventing it from balancing China with a coalition. Indeed, Dr. Kissinger calls for the creation of a Chinese-American “commonwealth”: one “which would enable [sic] other major countries such as Japan, Indonesia, Vietnam, India and Australia to participate in the construction of a system perceived as joint rather than polarized between ‘Chinese’ and ‘American’ blocs.” But Japan, Indonesia, Vietnam, India, and Australia are hardly likely to share Dr. Kissinger's optimism. Deprived of American support in facing Chinese demands, forced to become the objects of a Chinese-American entente, today’s actual and potential allies would have to make their own accommodations, eliminating the one and only potential long-term counterweight to China, the coalescence of all lesser powers menaced by its expansionism. As the man said, history need not be remembered but must still be lived.

1. It was thus at Mao’s lying in state, which I attended: diplomats accredited to Beijing were brought in to view the body in clusters, each forming a circle of the Tianxia—the innermost and the first to join us, most privileged guests, were the ambassadors of Romania, the Khmer Rouge, North Vietnam (soon to be demoted), and North Korea, with the Russian only coming in at the very end, in the outermost circle at that time.

2. Described in a military report in Book 88 of the Hòu hànshu (Book of the Later Han) attributed to Fan Ye (John E. Hill, tr.) http://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/texts/hhshu/hou_han_shu.html .

3. See Nicola Di Cosmo, Ancient China and Its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History (Cambridge University Press, 2002), p. 206 ff.

4. In the Shiji (史记), the Records of the Grand Historian (or Grand Scribe) of Sima Qian, 司馬遷, Vol. 99, Cols. 2144 and 2179. Increasingly available in English translations.

5. Stanford University Tianxia Workshop: Culture, International Relations, and World History May 6-11, 2011. The workshop will gather together a small group of distinguished scholars to engage in sustained conversations on the theoretical implications and practical values of the traditional Chinese vision of world order, or tianxia (all under heaven). Varied discourses indebted to tianxia have resurfaced in modern China in quest of moral and cultural ways of relating to and articulating an international society. We believe that the Chinese vision may prove productive in exploring possibilities of world culture and literature in the tension-ridden yet interconnected world. [author’s emphasis] http://www.stanford.edu/dept/asianlang/cgi-bin/about/tianxia_workshop.php

View the discussion thread.

Join the Hoover Institution’s community of supporters in ideas advancing freedom.

China History: The Sui Dynasty Unified China in the 6th Century Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

China has a rich and vibrant history that includes many periods. Each era implemented new reformations and improvements in the country, thus laying the foundation for the future. This paper summarizes the history of The Sui Dynasty that unified China in the 6th century. Despite the fact that the reign of the Sui Dynasty lasted for almost 4 decades, their decisions provided the basis for the reunion and prosperity of divided China after a long war.

The rule of the Sui Dynasty officially started when Yang Jian with the help of the military overthrew and killed the previous Emperor’s family. In 581 CE, he became the Emperor, and later in history, he was known under the name of Wendi. In the beginning, Emperor Wendi controlled regions of Northern China, but in the next ten years, he had united all regions. Eight years after the beginning of his reign, Yang Jian eliminated the Chen Dynasty, which ruled over southern China, and implemented many successful initiatives during his rule in united China.

Although Emperor Wendi was celebrated by the Chinese people for unifying the country and changing the structure of the local government, he accomplished other important achievements that improved the government and made life for Chinese citizens easier. Those reformations included coming back to Confucianism and the increasing Buddhism practices and expanding the army. The rule of Emperor Wendi lasted until 604 AC when he was killed by his son Yang Guang, who is also known as Yangdi.

The first emperor Wendi was previously a general for the Northern Zhou dynasty. Although the reign of the Sui Dynasty lasted only for roughly thirty to forty years, many developments started during his rule. For example, as it was previously noted that he modified local government in order to make internal administration more transparent. Moreover, he reconsidered and changed the criminal law, as well as several public work projects, that involved developing a complex canal system. It connected three main rivers of China and was named the Grand Canal.

The first Emperor of the Sui Dynasty also took some serious action to protect the borders of his newly unified empire. At that time, China was surrounded by many strong and dangerous empires. On the northern border the domain of the Yuezhi was located, a federation of nomadic warriors of Turkic heritage. They controlled the territory of Mongolia from Manchuria to the western border of the Byzantine Empire. Nevertheless, on the inside, the confederacy experienced a division into two competing groups, the Greater Yuezhi and Lesser Yuezhi.

The Greater Yuezhi controlled the western half of confederacy territory, up to IIi River. The Lesser Yuezhi controlled the eastern and southern territory on the edge of the Tibetan Plateau. Emperor Wendi offered his assistance to the Greater Yuezhi and tried to lessen the strength and political power of the Lesser Yuezhi khan. This conspiracy significantly reduced the risk of being attacked by the Greater Yuezhi.

Moreover, the other reasons for the decreased threat included an improved Great Wall and the expansion of Chinese army troops, who constantly patrolled the northern frontiers. At the same time, these strategic moves enabled the reopening of the western trade routes. Thus, a successful trade relationship with Central and Western Asia was established yet again. Considering the changes in political structure, it can be said that during the rule of the Sui Dynasty, both Emperors Wendi and Yangdi developed strong military forces. They were very successful not only in protecting borders but also in fighting the Emperor’s own wars. As a result, the Chinese army was victorious in the conquest of Vietnam and the Champa Kingdom, which allowed the territory of the Empire of China to spread.

It is also worth noticing that Emperor Wendi contributed to the rise of the Chinese economy by creating improved infrastructures. Apart from this, Yang Jian provided the granaries, which were used to save up food and keep market prices under control. Those reformations played a crucial role in the economic advancement of the empire. Following the success of the Jin dynasty, the economy of the Sui reign thrived. Moreover, the economic field also prospered after the flourishing of agriculture, because after previous wars, soldiers returned home and started farming. Another economic accomplishment of the Sui also was the Juntian system of splitting farming fields evenly among people. Moreover, in order to encourage trade, the taxes were also lowered.

Historians consider it a significant dynasty owing to the changes that took place during its period. There were notable political changes during the reign Sui dynasty. For the first time in the history of the Chinese Empire, there was a creation of a new political system with a modified structure. Three separate departments and six new ministries were formed. This reformation was studied and analyzed by many history researchers. For instance, Man Meng mentions that the Sui Dynasty also founded Three-Provinces-Six-Department system.

Additionally, the royal rule was improved, and the labor division in the courts became more informative. Consequently, the system for talent choice was seriously altered. The original hierarchical style of nine ranks of officials was substituted by the imperial examination style.

Wendi’s successor was Yangdi, who in many ways was even more ambitious than his father. Yangdi built a second capital at Loyang in the east to complement the site constructed by Wendi southeast of Changan. He oversaw the return of the southernmost regions of China into the empire and the addition of the Champa kingdom in Vietnam. Yet it was Yangdi’s ambitions, combined with financial mismanagement that ultimately led to the end of the reign of his clan. His attempts to meddle in the internal politics of his nomadic neighbors led to the alienation of the western Yuezhi fraction, which wrested away control of the city-states of the Tarim Basin, formerly under Sui protection.

Nevertheless, Yangdi was an educated Emperor, he encouraged the spread of Confucian culture and restored the principles of Confucian Education. Although Emperor Yang was called the tyrannical monarch, he had been careful before winning the throne and then gave grant indulgence to music after winning the trust of Emperor Wen of Sui and his mother. Emperor Yang was a talent in literacy, his creation of poetry style and series of policies in music have a great impact on China’s music culture.

Furthermore, one of the most remarkable projects of the Sui Dynasty was the creation of the Grand Canal, which joined the Yellow River together with the Huai and Yangtze Rivers. From that moment on, the transportation and shipping of goods from north to south was much easier. This improvement laid a crucial foundation for the economic and social advancement of the Chinese Empire. However, those constructions and wars were expensive. People suffered from intensive labor camps. Ten of thousands of able-bodied men were taken from rural farms and other occupations, which damaged the agricultural base and the economy. Peasant uprisings broke out one after another.

The fall of the Sui started relatively early; Emperor Yang was the second and the last Emperor. Several reasons contributed to the end of the Sui Dynasty. For example, the great famine caused peasants’ rebellions across the empire. To be more specific, a rebellion at Mt. Changbaishan in 611 seriously damaged the reputation of Emperor. The peasants believed that the Emperor was corrupt, and later they united their troops to create and expand the Wagang army. The movement was controlled by the agrarian leaders Zhai Rang and Li Mi who attacked and took over a granary to steal the food and distribute it among the poor. After this raid, the army killed Emperor Yangdi, thus ending the Sui Dynasty in 618.

In conclusion, it is worth noting that even though the reign of the Sui Dynasty was relatively short, it had a profound effect on the empire. Two emperors greatly contributed to the prosperity of the political, social and economic life of Chinese citizens. Their decisions and reformations united previously divided regions and laid the basis for future improvements. Understanding these changes is crucial for creating a foundation for understanding Chinese history.

Ding, Shuyue. The Music Complex of Emperor Yang of Sui Dynasty . Proceedings of 4th International Conference on Education, Language, Art and Intercultural Communication. Atlantis Press. 2017.

Jia, Jierui, Junyang Li, and Ke Gao. The Track of History: Finance and National Governance in Ancient China. International Journal of Education, Culture and Society 4, no. 1. 2019.

Jindong, C. A. I., and P. E. N. G. Jing. Introduction of Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal and analysis of its heritage values. Journal of Hydro-environment Research 26. 2019.

Jinwung, K. I. M., and Spencer C. Tucker. How did the Weaker Actor Defeat the Stronger Actor? Koguryŏ’s War with Sui (612–614) Revisited. Sungkyun Journal of East Asian Studies 18, no. 2 (2018).

Kaili, C. H. E. N. G. Emperor Wen of Sui Dynasty and Buddhism . Journal of Chongqing Three Gorges University 6. 2015.

Man, Meng. Rich Sui Dynasty and Strong Tang Dynasty: Dream of Great Power and Humanity Spirit . Journal of PLA Academy of Art 1. 2017.

Rodzinski, Witold. A History of China . Pergamon Press. 2017.

Xue, Da. Prosperity in Sui and Tang Dynasties . DeepLogic. 2019.

- The Decolonization in Asia and Africa in the Post-WW2 Period

- The History of China: Sun Yat-Sen as One of the Most Respected Revolutionary Leaders

- Sustainability in Fashion: Clothing Rental Services

- "Red Dust: A Path through China" and "Iron and Silk"

- Why Philosophy Emerged in Greece in the 6th Century BC

- Leabhar Gabhála: The Study of Celtic Mythology

- The Free Software Movement

- Imperialism: Politics and Differences of Empires

- Money and American Classes in 1870-1920

- Hernandez v. Texas: an Analysis

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, February 11). China History: The Sui Dynasty Unified China in the 6th Century. https://ivypanda.com/essays/china-history-the-sui-dynasty/

"China History: The Sui Dynasty Unified China in the 6th Century." IvyPanda , 11 Feb. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/china-history-the-sui-dynasty/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'China History: The Sui Dynasty Unified China in the 6th Century'. 11 February.

IvyPanda . 2022. "China History: The Sui Dynasty Unified China in the 6th Century." February 11, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/china-history-the-sui-dynasty/.

1. IvyPanda . "China History: The Sui Dynasty Unified China in the 6th Century." February 11, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/china-history-the-sui-dynasty/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "China History: The Sui Dynasty Unified China in the 6th Century." February 11, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/china-history-the-sui-dynasty/.

Paper in Ancient China

Server costs fundraiser 2024.

The widespread use of paper and printing were features of ancient China which distinguished it from other ancient cultures. Traditionally, paper was invented in the early 2nd century CE, but there is evidence it was much earlier. As a cheaper and more convenient material than bamboo, wood, or silk , paper helped spread literature and literacy but it was used for many other purposes from hats to packaging. The material was made finer over the centuries, was traded across Asia and was used in the first paper money from the early 12th century CE.

The Invention of Paper

There is ample archaeological evidence of primitive paper types from the 2nd century BCE in China, largely using hemp. It is believed that the invention of this early form of paper was accidental after clothes, which were made of hemp, were left too long after washing, and a residue formed in the water which could then be pressed into a useful new material. The traditional date for the invention of more refined paper has long been 105 CE. Cai Lun, the director of the Imperial Workshops at Luoyang , is the one credited with creating paper by using soaked and then pressed plant fibres which were dried in sheets on wooden frames or screens. Cumbersome bamboo or wooden strips and expensive silk had been used for centuries as a surface for writing but, after much endeavour, a lighter and cheaper alternative had finally been found in the form of paper scrolls.

Over time different fibres were experimented with to make paper, and so the quality had greatly increased by the end of the Han period (206-220 CE). Fibres from many different plants, the stems of grasses, vegetable matter, hemp, tree bark, and even rags were used and blended in a constant quest of experimentation to find the cheapest mix of materials which produced the highest quality of paper. Rattan replaced the early hemp paper and was favoured for centuries until it was replaced by bamboo fibres as the most common raw material from the 8th century CE. One of the reasons for rattan's replacement was that the demand for paper was so great the slow-growing plant had almost been wiped out in certain regions of China. Bamboo grows much quicker than hemp and so was a significantly cheaper option. From the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE) paper production techniques became even better and the main raw material was now the boiled bark of the mulberry tree. Chinese paper was of such high quality that it was traded to foreign states along the Silk Road .

Sheets of paper came in all sizes and many colour shades. Materials, techniques, and preferences varied from region to region, but there were helpful treatises written on the subject, the earliest being by Su I-chien (957-995 CE). Special paper with an appealing texture, pattern or colouring was reserved for calligraphy and art. These paper types were made using rice, wheat straw, sandalwood bark, hibiscus stalks, and even seaweed.

The Chinese were naturally rather secretive about their papermaking skills, just as they were with silk production but secrets rarely remain so for ever. The outside world, or at least the world west of China, acquired the knowledge of paper manufacturing in the 8th century CE (or plausibly even earlier). The trigger was when a group of papermakers were taken prisoner by their Arab victors following the Battle of Talas. Soon Baghdad would become a major producer of paper, and Medieval Europe , too, would eventually produce high-quality paper of its own.

Uses of Paper

The invention of paper greatly helped the spread of literature and literacy, making books more convenient to use and cheaper. Scholars at the Imperial academies were issued with thousands of sheets of paper each month by the government. Further, the combination of brush, ink, and paper would establish painting and calligraphy as the most important areas of art in China for the next two millennia. With the invention of block printing - either in Korea or China and perhaps in the 8th century CE - the demand for paper rocketed, especially from Buddhist scholars and temples. In the 10th century CE, when there was the Neo-Confucian revival, the printing of Confucian classics positively boomed. With the invention of moveable type printing, from the 11th or 12th century CE, paper needed to be thicker to resist the heavy metal blocks of type, but the two inventions - press and paper - would revolutionise communication and remain unchallenged as the means to send and store information until the arrival of the computer.

Paper was so highly valued in ancient China that it was used to pay tribute and taxes to the state during the Tang dynasty (618-907 CE). The Tang also imposed a colour code on the use of paper, with white paper being reserved for legal documents, yellow for government purposes, and blue for communications with Taoist temples.

Besides its use for writing and books, paper was used to produce topographical and military maps from the Han dynasty onwards. Drawn to a reasonably accurate scale, they included colour-coding and symbols for local features and included specific areas of enlarged scale. Other uses of paper included as packaging for delicate items such as medicine and as wrapping paper, especially for parcels of tea. Paper was widely used to make hats, stiffened it was used for armour, and thinned it could be used for windows. There were paper screens, sheets, curtains, clothes, and, eventually, money.

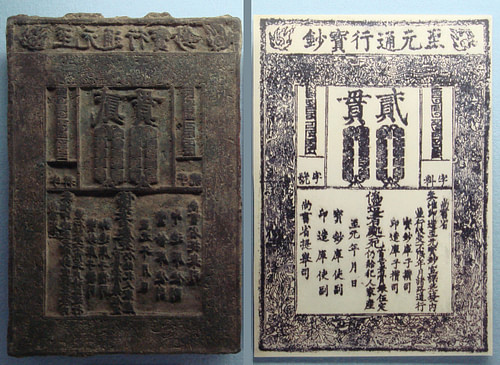

Paper Money

Following increases in trade , the system of barter, or the exchange of one material for another, was replaced by a system where one particular commodity came to be a common form of payment. In China rolls of silk or gold ingots could be used to pay for any other type of goods. For smaller exchanges metal coinage was used, first in the shape of tools, then in the form of more convenient small coins. As trade and the number of people involved in it grew ever larger, an even more convenient method of payment was sought. Another problem with coinage was the sheer quantity of copper required to make enough coins for the economy 's needs.

Paper money of a sort first appeared during the Tang Dynasty. The development sprang from merchants relying on paper documents. This was especially so for tea merchants, one of China's best-selling commodities. Merchants were wary of carrying valuable ingots to and from the state treasury and so preferred to use receipts instead. These paper documents allowed a merchant to make or collect his payment in any local treasury and so they became known as 'flying money'. This first form of paper money was not actually much of a success and, for larger transactions, merchants still preferred the greater security of silver ingots. The ideas was a good one, though, and paper money made a comeback in the 11th and 12th century CE.

In the 11th century CE in the Szechwan province, the use of heavy iron coinage necessitated the wealthy to leave their money in state deposit houses where it was more secure. Around 1023 CE, in order to indicate what money they had on deposit, people were issued with a paper certificate by the Song government. These certificates could also be used in transactions instead of physically moving the coinage. By the 12th century CE merchants elsewhere in China were again using more convenient paper receipts for their transactions instead of heavy bags of coins. These, in turn, led to the development of paper money around 1120 CE when the Chinese government established a monopoly on the issue of such receipts, in effect, creating the world's first banknotes. By 1260 CE the paper money had become what we would today call real banknotes - they could be kept for as long as one wished, used across the country to make purchases, and converted into gold or silver at any time.