Translations of "thesis" into Russian in sentences, translation memory

thesis translation | English-Russian dictionary

theses , these , thinness , the

Sign up to add your entry

- FAQ Technical Questions

- Text Translation

- Vocabulary Trainer

- Online Dictionary

- Login

- Online dictionary

- Products & Shop

- Conjugation

Vocabulary trainer

- Dictionary API

- Add to home screen

- Browse the dictionaries

- Terms and conditions of use

- Supply chain

- Data Protection Declaration

- Legal notice

- Privacy Settings

- Haitian Creole

- German Learner's Dictionary

- Dictionary of German Spelling

- Search in both directions

- Change language direction

My search history

- image/svg+xml Usage Examples

Translations for thesis in the English » Russian Dictionary

Thesis <-ses> [ˈθi:sɪs] n, monolingual examples (not verified by pons editors).

Would you like to add a word, a phrase or a translation?

Browse the dictionary

- Thermos flask

- thermostatic

Look up "thesis" in other languages

Links to further information.

You can suggest improvements to this PONS entry here:

We are using the following form field to detect spammers. Please do leave them untouched. Otherwise your message will be regarded as spam. We are sorry for the inconvenience.

How can I copy translations to the vocabulary trainer?

- Collect the vocabulary that you want to remember while using the dictionary. The items that you have collected will be displayed under "Vocabulary List".

- If you want to copy vocabulary items to the vocabulary trainer, click on "Import" in the vocabulary list.

Please note that the vocabulary items in this list are only available in this browser. Once you have copied them to the vocabulary trainer, they are available from everywhere.

- Most popular

- English ⇄ German

- English ⇄ Slovenian

- German ⇄ Spanish

- German ⇄ French

- German ⇄ Greek

- German ⇄ Polish

- Arabic ⇄ English

- Arabic ⇄ German

- Bulgarian ⇄ English

- Bulgarian ⇄ German

- Chinese ⇄ English

- Chinese ⇄ French

- Chinese ⇄ German

- Chinese ⇄ Spanish

- Croatian ⇄ German

- Czech ⇄ German

- Danish ⇄ German

- Dutch ⇄ German

- Elvish ⇄ German

- English ⇄ Arabic

- English ⇄ Bulgarian

- English ⇄ Chinese

- English ⇄ French

- English ⇄ Italian

- English ⇄ Polish

- English ⇄ Portuguese

- English ⇄ Russian

- English → Serbian

- English ⇄ Spanish

- Finnish ⇄ German

- French ⇄ Chinese

- French ⇄ English

- French ⇄ German

- French ⇄ Italian

- French ⇄ Polish

- French ⇄ Slovenian

- French ⇄ Spanish

- German ⇄ Arabic

- German ⇄ Bulgarian

- German ⇄ Chinese

- German ⇄ Croatian

- German ⇄ Czech

- German ⇄ Danish

- German ⇄ Dutch

- German ⇄ Elvish

- German ⇄ English

- German ⇄ Finnish

- German ⇄ Hungarian

- German → Icelandic

- German ⇄ Italian

- German ⇄ Japanese

- German ⇄ Latin

- German ⇄ Norwegian

- German ⇄ Persian

- German ⇄ Portuguese

- German ⇄ Romanian

- German ⇄ Russian

- German → Serbian

- German ⇄ Slovakian

- German ⇄ Slovenian

- German ⇄ Swedish

- German ⇄ Turkish

- Greek ⇄ German

- Hungarian ⇄ German

- Italian ⇄ English

- Italian ⇄ French

- Italian ⇄ German

- Italian ⇄ Polish

- Italian ⇄ Slovenian

- Italian ⇄ Spanish

- Japanese ⇄ German

- Latin ⇄ German

- Norwegian ⇄ German

- Persian ⇄ German

- Polish ⇄ English

- Polish ⇄ French

- Polish ⇄ German

- Polish ⇄ Italian

- Polish ⇄ Russian

- Polish ⇄ Spanish

- Portuguese ⇄ English

- Portuguese ⇄ German

- Portuguese ⇄ Spanish

- Romanian ⇄ German

- Russian ⇄ English

- Russian ⇄ German

- Russian ⇄ Polish

- Slovakian ⇄ German

- Slovenian ⇄ English

- Slovenian ⇄ French

- Slovenian ⇄ German

- Slovenian ⇄ Italian

- Slovenian ⇄ Spanish

- Spanish ⇄ Chinese

- Spanish ⇄ English

- Spanish ⇄ French

- Spanish ⇄ German

- Spanish ⇄ Italian

- Spanish ⇄ Polish

- Spanish ⇄ Portuguese

- Spanish ⇄ Slovenian

- Swedish ⇄ German

- Turkish ⇄ German

Identified ad region: ALL Identified country code: RU -->

Translator for

Translation of "thesis" into russian, lingvanex - your universal translation app, other words form.

- Vocabulary Games

- Words Everyday

- Russian to English Dictionary

- Favorite Words

- Word Search History

Topic Wise Words

Learn 3000+ common words, learn common gre words, learn words everyday.

Russian Studies

- Getting Started

- Find Articles

- Find Primary Sources

- Find Videos

- Chicago/Turabian Style

- Annotated Bibliographies

- Literature Reviews

- All about Dissertations

Featured Resource: Davidson Honors Theses

What is a thesis, why write a thesis are they necessary, how are theses formatted, tips for writing theses, resources for writing theses.

- Davidson Honors Theses A collection of Davidson theses that have earned departmental honors

Theses are comprehensive research projects completed at the undergraduate level. They encourage independent research, motivating students to contribute knowledge to a field of their choosing. Most theses have two overarching goals: to examine and critique existing scholarly literature, and to contribute a unique voice to the conversation. This second goal can either be met through experimental research, or though deeply analyzing existing research.

No Davidson students are required to write theses. However, many students may find writing theses to be advantageous. For example, theses can fulfill most major's capstone requirements.

Writing a thesis is also a required to earn academic honors in the following programs:

- Africana Studies

- Anthropology

- Chinese Studies

- Communication Studies

- Digital & Screen Media

- Educational Studies

- Environmental Studies

- French Studies

- Gender and Sexuality Studies

- German Studies

- Global Literacy Theory

- Hispanic Studies

- History

- Languages and Cultures of the Middle East

- Latin American Studies

- Linguistics

- Mathematics and Computer Science

- Neuroscience

- Political Science

- Public health

- Religious Studies

- Russian Language and literature

Theses are focused on answering a central research question. This question, chosen by the student, should be well-defined and set the tone for the paper. There are five parts to the typical modern theses:

- Part one: your research question, briefly foreshadowing the paper.

- Part two: reviews the existing research and conversation in your subject area.

- Part three: lays out the methodology you used to complete your research.

- Part four: present your results.

- Part five: interprets and analyzes your results, and compares your conclusions to those found in pre-existing research.

If your professor asks you to follow a different format, you should do so. If you need help formatting a thesis, please contact your professor or a librarian.

- Set deadlines. Theses are often year-long projects, and can occasionally be over 100 pages long.* In undertaking a project of such magnitude, it's incredibly important to stay on track.

- Never stop researching. Beyond directly researching your topic, it may be helpful to read scholarly journals and other completed theses. Here , you can find a collection of Davidson theses (from 2013 to 2020) that have earned departmental honors.

- Think about defense. It's common practice to defend your thesis after submitting it. This includes presenting your thesis, and answering questions about it. It's important to prepare for this question-and-answer session by anticipating questions and formulating answers.

- Stay motivated. Your thesis marks your transformation from student to academic. It can occasionally determine your career course or be your first published work. A thesis is much more work than a typical assignment, but has incredible potential to define you!

* This chart plots the average thesis length for programs at Davidson.

- << Previous: All about Dissertations

- Last Updated: Jul 10, 2024 2:23 PM

- URL: https://davidson.libguides.com/russian

Mailing Address : Davidson College - E.H. Little Library, 209 Ridge Road, Box 5000, Davidson, NC 28035

Russian & East European Studies

- Start Your Research

- Articles & Books

- Primary Sources

- Internet Resources

- Atlases & Maps

- Data & Statistics

Dissertations & Theses

- Encyclopedias

- Data & Document Sources This link opens in a new window

- ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global This link opens in a new window Electronic equivalent of Dissertation Abstracts International. this represents the work of authors from over 1,000 North American and European universities on a full range of academic subjects. Citations for Master's theses from 1988 forward include 150-word abstracts. All dissertations published since 1997, and some from prior years, are available for free download; others may be requested via Interlibrary Loan more... less... Includes abstracts for doctoral dissertations beginning July 1980 and for Master's theses beginning Spring 1988. Citations for dissertations published from 1980 forward include 350-word abstracts. Citations for Master's theses from 1988 forward include 150-word abstracts. Most dissertations published since 1997, and some from prior years, are available for free download; others may be requested via Interlibrary Loan.

- Dissertations & Theses (Georgetown-authored) This link opens in a new window Recent online theses and dissertations from selected Georgetown programs and departments. For access to Georgetown theses and dissertations authored prior to 2006, see the Georgetown catalog or refer to ProQuest's Dissertations & Theses database. Print copies of disserations may be requested using the Library's Library Use Only Materials Request. .

- EThoS: Electronic Theses Online This link opens in a new window The British Library's database of digitized theses from UK higher education institutions. Free registration and login is required.

- Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations This link opens in a new window Presents a searchable and browsable collection of electronic theses and dissertations. Includes masters- and doctoral-level theses and dissertations from about 70 institutions, U.S. and international.

- Theses Canada Portal This link opens in a new window Provides information on all the Canadian theses and dissertations in the collection of the National Library of Canada. Free access to the full-text of theses from 1998.

Dissertation Reviews

- Reviews of Dissertations on Russian Studies Dissertation Reviews features friendly, non-critical overviews of recently defended and unpublished dissertations, as well as articles on archives and libraries around the world.

- << Previous: Data & Statistics

- Next: Encyclopedias >>

- Last Updated: Aug 13, 2024 11:04 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.georgetown.edu/russian

International Communist Current

Workers of the world, unite, search form.

April Theses: Lenin’s fundamental role in the Russian Revolution

Submitted by World Revolution on 2 April, 2007 - 17:08

It is 90 years since the start of the Russian revolution. More particularly, this month sees the 90th anniversary of the ‘April Theses’, announced by Lenin on his return from exile, and calling for the overthrow of Kerensky’s ‘Provisional Government’ as a first step towards the international proletarian revolution. In highlighting Lenin’s crucial role in the revolution, we are not subscribing to the ‘great man’ theory of history, but showing that the revolutionary positions he was able to defend with such clarity at that moment were an expression of something much deeper – the awakening of an entire social class to the concrete possibility of emancipating itself from capitalism and imperialist war. The following article was originally published in World Revolution 203, April 1997. It can be read in conjunction with a more developed study of the April Theses now republished on our website, ‘ The April Theses: signpost to the proletarian revolution ’.

On 4 April 1917 Lenin returned from his exile in Switzerland, arrived in Petrograd and addressed himself directly to the workers and soldiers who crowded the station in these terms: “Dear comrades, soldiers, sailors and workers. I am happy to greet in you the victorious Russian revolution, to greet you as the advance guard of the International proletarian army... The Russian revolution achieved by you has opened a new epoch. Long live the worldwide socialist revolution!...” (Trotsky, History of the Russian Revolution ). 80 years later the bourgeoisie, its historians and media lackeys, are constantly busy maintaining the worst lies and historic distortions on the world proletarian revolution begun in Russia.

The ruling class’ hatred and contempt for the titanic movement of the exploited masses aims to ridicule it and to ‘show’ the futility of the communist project of the working class, its fundamental inability to bring about a new social order for the planet. The collapse of the eastern bloc has revived its class hatred. It has unleashed a gigantic campaign since then to hammer home the obvious defeat of communism, identified with Stalinism, and with that the defeat of marxism, the obsolescence of the class struggle and even the idea of revolution which can only lead to terror and the Gulag. The target of this foul propaganda is the political organisation, the incarnation of the vast insurrectionary movement of 1917, the Bolshevik Party, which constantly draws all the vindictiveness of the defenders of the bourgeoisie. For all these apologists for the capitalist order, including the anarchists, whatever their apparent disagreements, it is a question of showing that Lenin and the Bolsheviks were a band of power-hungry fanatics who did everything they could to usurp the democratic acquisitions of the February 1917 revolution (see ‘February 1917’ WR 202) and plunge Russia and the world into one of the most disastrous experiences in history.

Faced with all these unbelievable calumnies against Bolshevism, it falls to revolutionaries to re-establish the truth and reaffirm the essential point concerning the Bolshevik Party: it was not a product of Russian barbarism or backwardness, nor of deformed anarcho-terrorism, nor of the absolute concern for power by its leaders. Bolshevism was, in the first place, a product of the world proletariat, linked to a marxist tradition, the vanguard of the international movement to end all exploitation and oppression. To this end the statement of positions Lenin brought out on his return to Russia, known as the April Theses, gives us an excellent point of departure to refute all the various untruths on the Bolshevik Party, its nature, its role and its links with the proletarian masses.

The conditions of struggle on Lenin’s return to Russia in April 1917

In the previous article ( WR 202) we recalled that the working class in Russia had well and truly opened the way to the world communist revolution with the events of February 1917, overturning Tsarism, organising in soviets and showing a growing radicalisation. The insurrection resulted in a situation of dual power. The official power was the bourgeois ‘Provisional Government’, initially lead by the liberals but which later gained a more ‘socialist’ hue under the direction of Kerensky. On the other hand effective power already lay, as was well understood, in the hands of the soviets of workers’ and soldiers’ deputies. Without soviet authorisation the government had little hope of imposing its directives on the workers and soldiers. But the working class had not yet acquired the necessary political maturity to take all the power. In spite of their more and more radical actions and attitudes, the majority of the working class and behind them the peasant masses, were held back by illusions in the nature of the bourgeoisie, and by the idea that only a bourgeois democratic revolution was on the agenda in Russia. The predominance of these ideas among the masses was reflected in the domination of the soviets by Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries who did everything they could to make the soviets impotent in the face of the newly installed bourgeois regime. These parties, which had gone over, or were in the process of going over, to the bourgeoisie, tried by all means to subordinate the growing revolutionary movement to the aims of the Provisional Government, especially in relation to the imperialist war. In this situation, so full of dangers and promises, the Bolsheviks, who had directed the internationalist opposition to the war, were themselves in almost complete confusion at that moment, politically disorientated. So, “ In the ‘manifesto’ of the Bolshevik Central Committee, drawn up just after the victory of the insurrection, we read that ‘the workers of the shops and factories, and likewise the mutinied troops, must immediately elect their representatives to the Provisional Revolutionary Government’... They behaved not like the representatives of a proletarian party preparing an independent struggle for power, but like the left wing of a democracy ” ( Trotsky, History of the Russian Revolution , vol. 1, chapter XV , p.271, 1967 Sphere edition). Worse still, when Stalin and Kamenev took the direction of the party in March, they moved it even further to the right. Pravda, the official organ of the party, openly adopted a defencist position on the war: “Our slogan is not the meaningless ‘down with war’... every man remains at his fighting post.” (Trotsky, p.275). The flagrant abandonment of Lenin’s position on the transformation of the imperialist war into a civil war caused resistance and even anger in the party and among the workers of Petrograd, the heart of the proletariat. But these most radical elements were not capable of offering a clear programmatic alternative to this turn to the right. The party was then drawn towards compromise and treason, under the influence of the fog of democratic euphoria which appeared after the February revolt.

The political rearmament of the Party

It fell to Lenin, then, after his return from abroad, to politically rearm the party and to put forward the decisive importance of the revolutionary direction through the April Theses: “Lenin’s theses produced the effect of an exploding bomb” (Trotsky, p. 295). The old party programme had become null and void, situated far behind the spontaneous action of the masses. The slogan to which the “Old Bolsheviks” were attached, the “democratic dictatorship of workers and peasants” was henceforth an obsolete formula as Lenin put forward: “ The revolutionary democratic revolution of the proletariat and the peasants has already been achieved... ” (Lenin, Letters on tactics ). However, “ The specific feature of the present situation in Russia is that the country is passing from the first stage of the revolution - which, owing to the insufficient class consciousness and organisation of the proletariat, placed power in the hands of the bourgeoisie - to its second stage, which must place power in the hands of the proletariat and the poorest sections of the peasants. ” (Point 2 of the April Theses). Lenin was one of the first to grasp the revolutionary significance of the soviet as an organ of proletarian political power. Once again Lenin gave a lesson on the marxist method, in showing that marxism was the complete opposite of a dead dogma but a living scientific theory which must be constantly verified in the laboratory of social movements.

Similarly, faced with the Menshevik position according to which backward Russia was not yet ripe for socialism, Lenin argued as a true internationalist that the immediate task was not to introduce socialism in Russia (Thesis 8). If Russia, in itself, was not ready for socialism, the imperialist war had demonstrated that world capitalism as a whole was truly over-ripe. For Lenin, as for all the authentic internationalists then, the international revolution was not just a pious wish but a concrete perspective developed from the international proletarian revolt against the war - the strikes in Britain and Germany, the political demonstrations, the mutinies and fraternisations in the armed forces of several countries, and certainly the growing revolutionary flood in Russia itself, which revealed it. This is where the appeal for the creation of a new International at the end of the Theses came from. This perspective was going to be completely confirmed after the October insurrection by the extension of the revolutionary wave to Italy, Hungary, Austria and above all Germany.

This new definition of the proletariat’s tasks also brought another conception of the role and function of the party. There also the “Old Bolsheviks” like Kamenev were at first revolted by Lenin’s vision, his idea of the soviets taking power on the one hand and on the other his insistence on the class autonomy of the proletariat against the bourgeois government and the imperialist war, even if that would mean remaining for awhile in the minority and not as Kamenev would like: “ remaining with the masses of the revolutionary proletariat ”. Kamenev used the conception of “ a mass party ” to oppose Lenin’s conception of a party of determined revolutionaries, with a clear programme, united, centralised, minoritarian, capable of resisting the siren calls of the bourgeoisie and petit-bourgeoisie and illusions existing in the working class. This conception of the party has nothing to do with the Blanquist terrorist sect, that Lenin was accused of putting forward, nor even with the anarchist conception submitting to the spontaneity of the masses. On the contrary there was the recognition that in a period of massive revolutionary turbulence, of the development of consciousness in the class, the party can no longer organise nor plan to mobilise the masses in the way of the conspiratorial associations of the 19th century. But that made the role of the party more essential than ever. Lenin came back to the vision that Rosa Luxemburg developed in her authoritative analysis of the mass strike in the period of decadence: “ If we now leave the pedantic scheme of demonstrative mass strikes artificially brought about by order of the parties and trade unions, and turn to the living picture of a peoples’ movement arising with elemental energy... it becomes obvious that the task of social democracy does not consist in the technical preparation and direction of mass strikes, but first and foremost in the political leadership of the whole movement. ” (Luxemburg, The Mass Strike, the Political Party and the Trade Unions ). All Lenin’s energy was going to be orientated towards the necessity of convincing the party of the new tasks which fell to it, in relation to the working class, the central axis of which is the development of class consciousness. Thesis 4 posed this clearly: “ The masses must be made to see that the Soviets of Workers’ Deputies are the only possible form of revolutionary government and that therefore our task is, as long as this government yields to the influence of the bourgeoisie, to present a patient, systematic and persistent explanation of the errors of their tactics, an explanation especially adapted to the practical needs of the masses… we preach the necessity of transferring the entire state power to the Soviets of Workers’ Deputies. ” So this approach, this will to defend clear and precise class principles, going against the current and being in a minority, has nothing to do with purism or sectarianism. On the contrary they were based on a comprehension of the real movement which was unfolding in the class at each moment, on the capacity to give a voice and direction to the most radical elements within the proletariat. The insurrection was impossible as long as the Bolshevik’s revolutionary positions, positions maturing throughout the revolutionary process in Russia, had not consciously won over the soviets. We are a very long way from the bourgeois obscenities on the supposed putschist attitude of the Bolsheviks! As Lenin still affirmed: “ We are not charlatans. We must base ourselves only on the consciousness of the masses ” (Lenin’s second speech on his arrival in Petrograd, cited in Trotsky, p. 293).

Lenin’s mastery of the marxist method, seeing beyond the surface and appearances of events, allowed him in company with the best elements of the party, to discern the real dynamic of the movement which was unfolding before their eyes and to meet the profound desires of the masses and give them the theoretical resources to defend their positions and clarify their actions. They were also enabled to orientate themselves against the bourgeoisie by seeing and frustrating the traps which the latter tried to set for the proletariat, as during the July days in 1917. That’s why, contrary to the Mensheviks of this time and their numerous anarchist, social democratic and councilist successors, who caricature to excess certain real errors by Lenin [1] in order to reject the proletarian character of the October 1917 revolution, we reaffirm the fundamental role played by Lenin in the rectification of the Bolshevik Party, without which the proletariat would not have been able to take power in October 1917. Lenin’s life-long struggle to build the revolutionary organisation is a historic acquisition of the workers’ movement. It has left revolutionaries today an indispensable basis to build the class party, allowing them to understand what their role must be in the class as a whole. The victorious insurrection of October 1917 validates Lenin’s view. The isolation of the revolution after the defeat of the revolutionary attempts in other countries of Europe stopped the international dynamic of the revolution which would have been the sole guarantee of a local victory in Russia. The soviet state encouraged the advent of Stalinism, the veritable executioner of the revolution and of the Bolsheviks.

What remains essential is that during the rising tide of the revolution in Russia, the Lenin of the April Theses was never an isolated prophet, nor was he holding himself above the vulgar masses, but he was the clearest voice of the most revolutionary tendency within the proletariat, a voice which showed the way which lead to the victory of October 1917. “ In Russia the problem could only be posed. It could not be solved in Russia. And in this sense, the future everywhere belongs to ‘Bolshevism’. ” (Rosa Luxemburg, The Russian Revolution ). SB, March 2007.

[1] Among these great play is made by the councilists on the theory of ‘consciousness brought from outside’ developed in ‘What is to be done?’. Well, afterwards, Lenin recognised this error and amply proved in practice that he had acquired a correct vision of the process of the development of consciousness in the working class.

History of the workers' movement:

- 1917 - Russian Revolution

Bookmark/Search this post

Get the Reddit app

r/translator is *the* community for Reddit translation requests. Need something translated? Post here! We will help you translate any language, including Japanese, Chinese, German, Arabic, and many others. If you speak more than one language - especially rare ones - and want to put your multilingual skills to use, come join us!

[English > Russian] Thesis Dedication

By continuing, you agree to our User Agreement and acknowledge that you understand the Privacy Policy .

Enter the 6-digit code from your authenticator app

You’ve set up two-factor authentication for this account.

Enter a 6-digit backup code

Create your username and password.

Reddit is anonymous, so your username is what you’ll go by here. Choose wisely—because once you get a name, you can’t change it.

Reset your password

Enter your email address or username and we’ll send you a link to reset your password

Check your inbox

An email with a link to reset your password was sent to the email address associated with your account

Choose a Reddit account to continue

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of thesis

Did you know.

In high school, college, or graduate school, students often have to write a thesis on a topic in their major field of study. In many fields, a final thesis is the biggest challenge involved in getting a master's degree, and the same is true for students studying for a Ph.D. (a Ph.D. thesis is often called a dissertation ). But a thesis may also be an idea; so in the course of the paper the student may put forth several theses (notice the plural form) and attempt to prove them.

Examples of thesis in a Sentence

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'thesis.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

in sense 3, Middle English, lowering of the voice, from Late Latin & Greek; Late Latin, from Greek, downbeat, more important part of a foot, literally, act of laying down; in other senses, Latin, from Greek, literally, act of laying down, from tithenai to put, lay down — more at do

14th century, in the meaning defined at sense 3a(1)

Dictionary Entries Near thesis

the sins of the fathers are visited upon the children

thesis novel

Cite this Entry

“Thesis.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/thesis. Accessed 16 Aug. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of thesis, more from merriam-webster on thesis.

Nglish: Translation of thesis for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of thesis for Arabic Speakers

Britannica.com: Encyclopedia article about thesis

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

Plural and possessive names: a guide, commonly misspelled words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), absent letters that are heard anyway, how to use accents and diacritical marks, popular in wordplay, 8 words for lesser-known musical instruments, it's a scorcher words for the summer heat, 7 shakespearean insults to make life more interesting, 10 words from taylor swift songs (merriam's version), 9 superb owl words, games & quizzes.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to Write a Thesis Statement | 4 Steps & Examples

How to Write a Thesis Statement | 4 Steps & Examples

Published on January 11, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on August 15, 2023 by Eoghan Ryan.

A thesis statement is a sentence that sums up the central point of your paper or essay . It usually comes near the end of your introduction .

Your thesis will look a bit different depending on the type of essay you’re writing. But the thesis statement should always clearly state the main idea you want to get across. Everything else in your essay should relate back to this idea.

You can write your thesis statement by following four simple steps:

- Start with a question

- Write your initial answer

- Develop your answer

- Refine your thesis statement

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is a thesis statement, placement of the thesis statement, step 1: start with a question, step 2: write your initial answer, step 3: develop your answer, step 4: refine your thesis statement, types of thesis statements, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about thesis statements.

A thesis statement summarizes the central points of your essay. It is a signpost telling the reader what the essay will argue and why.

The best thesis statements are:

- Concise: A good thesis statement is short and sweet—don’t use more words than necessary. State your point clearly and directly in one or two sentences.

- Contentious: Your thesis shouldn’t be a simple statement of fact that everyone already knows. A good thesis statement is a claim that requires further evidence or analysis to back it up.

- Coherent: Everything mentioned in your thesis statement must be supported and explained in the rest of your paper.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

The thesis statement generally appears at the end of your essay introduction or research paper introduction .

The spread of the internet has had a world-changing effect, not least on the world of education. The use of the internet in academic contexts and among young people more generally is hotly debated. For many who did not grow up with this technology, its effects seem alarming and potentially harmful. This concern, while understandable, is misguided. The negatives of internet use are outweighed by its many benefits for education: the internet facilitates easier access to information, exposure to different perspectives, and a flexible learning environment for both students and teachers.

You should come up with an initial thesis, sometimes called a working thesis , early in the writing process . As soon as you’ve decided on your essay topic , you need to work out what you want to say about it—a clear thesis will give your essay direction and structure.

You might already have a question in your assignment, but if not, try to come up with your own. What would you like to find out or decide about your topic?

For example, you might ask:

After some initial research, you can formulate a tentative answer to this question. At this stage it can be simple, and it should guide the research process and writing process .

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Now you need to consider why this is your answer and how you will convince your reader to agree with you. As you read more about your topic and begin writing, your answer should get more detailed.

In your essay about the internet and education, the thesis states your position and sketches out the key arguments you’ll use to support it.

The negatives of internet use are outweighed by its many benefits for education because it facilitates easier access to information.

In your essay about braille, the thesis statement summarizes the key historical development that you’ll explain.

The invention of braille in the 19th century transformed the lives of blind people, allowing them to participate more actively in public life.

A strong thesis statement should tell the reader:

- Why you hold this position

- What they’ll learn from your essay

- The key points of your argument or narrative

The final thesis statement doesn’t just state your position, but summarizes your overall argument or the entire topic you’re going to explain. To strengthen a weak thesis statement, it can help to consider the broader context of your topic.

These examples are more specific and show that you’ll explore your topic in depth.

Your thesis statement should match the goals of your essay, which vary depending on the type of essay you’re writing:

- In an argumentative essay , your thesis statement should take a strong position. Your aim in the essay is to convince your reader of this thesis based on evidence and logical reasoning.

- In an expository essay , you’ll aim to explain the facts of a topic or process. Your thesis statement doesn’t have to include a strong opinion in this case, but it should clearly state the central point you want to make, and mention the key elements you’ll explain.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

A thesis statement is a sentence that sums up the central point of your paper or essay . Everything else you write should relate to this key idea.

The thesis statement is essential in any academic essay or research paper for two main reasons:

- It gives your writing direction and focus.

- It gives the reader a concise summary of your main point.

Without a clear thesis statement, an essay can end up rambling and unfocused, leaving your reader unsure of exactly what you want to say.

Follow these four steps to come up with a thesis statement :

- Ask a question about your topic .

- Write your initial answer.

- Develop your answer by including reasons.

- Refine your answer, adding more detail and nuance.

The thesis statement should be placed at the end of your essay introduction .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, August 15). How to Write a Thesis Statement | 4 Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 13, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/thesis-statement/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write an essay introduction | 4 steps & examples, how to write topic sentences | 4 steps, examples & purpose, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Type to search

Ten Theses on Russia in the 21st Century

Reflections on hybrid administration, algorithms for exiting the conflict, and how to govern the world’s most complex country

Thesis 1: The future of Russian governance is neither necessarily democratic nor strictly non-democratic. This choice is likely too binary for Russia’s extremely complex realities. Instead, a future Russia may well be – and perhaps should be – decidedly hybrid, drawing promiscuously on the best in 21st century structures and practices from around the world.

Russia is a very young country – even if most people, including many Russians, forget that this Russia, in its post-Soviet incarnation, is only just completing its third decade. It is therefore naturally still solidifying and indeed inventing, improvising and legitimating its governing institutions, not to mention forming (with inconsistent success) its future political elites. The country’s constitutional youth, coupled with its present unique internal and international pressures, means that Moscow can look non-dogmatically westward and eastward alike (and elsewhere besides) to adopt the best in governing approaches, even as it indigenizes these and ends up with its own idiom – as is, by history and mentality alike, the Russian wont.

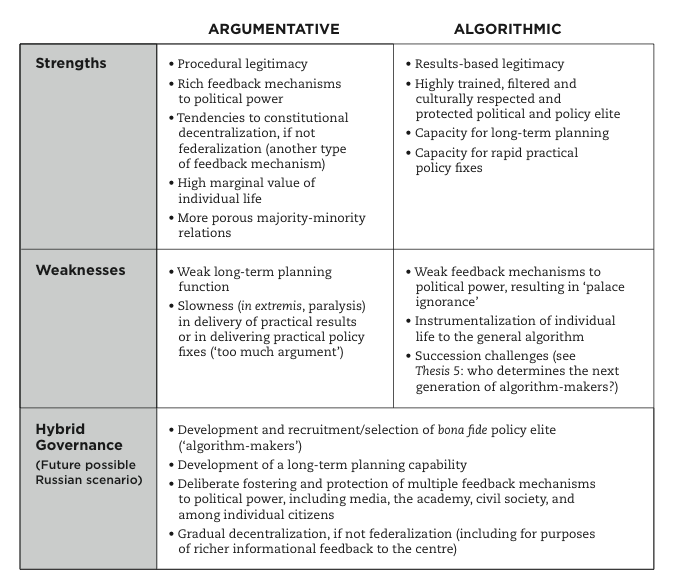

Let me propose that there are two dominant governing paradigms in the world today – on the one hand, the democratic tradition or, more tightly, what I would call ‘argumentative governance’; and on the other, ‘algorithmic governance.’ Argumentative governance prevails in the presumptive West – the deeply democratic countries of North America, Western Europe and indeed much of the EU, Australia and New Zealand. Algorithmic governance is led almost exclusively by the dyad of modern China and Singapore. Most of the remaining countries in the world – in the former Soviet space, the Middle East (including Israel), the Americas, Africa, and much of Asia (including India) – are still in what might be called the ‘voyeur’ world, still stabilizing, legitimizing or relegitimizing their governance regimes and institutions according to one tradition or the other, or actively borrowing from, and experimenting with, both.

Argumentative (or democratic) governance is characterized by fairly elected governments that are constantly opposed, challenged or corrected by deeply ingrained institutions (like political oppositions, the courts or other levels of government) or broad, activist estates (like the media, the academy, and various non-governmental organizations and groupings, not excluding religious organizations). Algorithmic governance, however, is characterized by the centrality of a smaller, select, highly professional group of national ‘algorithm-makers’ who, having been selected largely through intense filtering based principally on technical and intellectual (and perhaps ideological) qualifications (the so-called ‘smartest people in the room’), are constitutionally and culturally protected in their ability to generalize these algorithms throughout the country over the long run. Algorithmic governance lays claim to legitimacy via the securing of visible, concrete results in the form of consistently rising material wealth, advanced physical infrastructure, and general public order and stability – and indeed the rapidity (and predictability) with which such outcomes are realized and real-life problems are solved.

What would hybrid Russian governance look like in the 21st century? Answer: It would draw on the obvious strengths of the dominant algorithmic and argumentative governance models, while guarding against the major weaknesses of each of these idioms.

Argumentative governance, on the other hand, maintains its legitimacy via procedural argument in the contest for power among political parties, and in the information provided to power through various feedback loops. A large number of these argumentative regimes are federal in nature (just as the number of federal regimes globally has grown markedly over the last couple of decades), and so centre-region relations are both another source of procedural argument and a type of feedback to power (from the local to the general or macro).

What would hybrid Russian governance look like in the 21st century? Answer: It would draw on the obvious strengths of the dominant algorithmic and argumentative governance models, while guarding against the major weaknesses of each of these idioms. What are the key strengths of the algorithmic system that Russia should wish to adopt? First and foremost, Russia must invest in properly creating, over time (the next 15-20 years), a deep policy elite, meritocratically recruited and trained, to populate all its levels of government, from the federal centre in Moscow to the regional and municipal governments. Such a deep, professional post-Soviet policy elite is manifestly absent in Russia today, across its levels of government – a problem that repeats itself in nearly all of the 15 post-Soviet states.

Second, Russia must develop a credible long-term national planning capability (as distinct from the current exclusively short-term focus and occasional rank caprice of Russian governments, pace the various longer-term official national strategies and documents), led by the said algorithmic policy elite at the different levels of government, and implemented with great seriousness across the territory of the country.

Third, Russia requires an intelligent degree of very gradual decentralization (rapid decentralization being potentially fatal to national unity, or otherwise fragmenting the country’s internal coherence across its huge territory) and, if necessary or possible, a degree of genuine federalization of governmental power across the Russian territory.

Fourth, Russia’s policy elites must foster the development (and protection) of many more feedback mechanisms from citizens to political power in both the federal centre and in regional governments – not for purposes of democratic theatre or fetish, but rather to avoid making major or even existentially fatal policy mistakes, or indeed to correct policy mistakes and refine the governing algorithms in the interest of on-the-ground results and real-life problem-solving (a major imperative in Chinese algorithmic governance today, where the governing elites, as with past Chinese emperors, are, whatever their intellect, said to be excessively ‘far away’). These feedback loops – from the media, the academy, various groups and, evidently, from all Russian citizens – help to ensure that even the smartest algorithm-makers in the future policy elite do not make catastrophic mistakes based on information that is wholly detached from realities on the ground in Russia, across its massive territory.

Uncontrolled or excessively rapid federalization or decentralization, of course, could lead to the breakup of the country or to generalized chaos (a fact well underappreciated outside of Russia) – so strong are the centrifugal and also regionalized ethnic forces across Russia’s huge territory and regional diversity.

Thesis 2: Beyond this decentralization, Russia should ideally federalize substantively, even if the country is already, according to its present constitution, formally federal. At a minimum, as mentioned, the country must before long effectuate a gradual, controlled decentralization. Uncontrolled or excessively rapid federalization or decentralization, of course, could lead to the breakup of the country or to generalized chaos (a fact well underappreciated outside of Russia) – so strong are the centrifugal and also regionalized ethnic forces across Russia’s huge territory and regional diversity. Unintelligent or careless federalization, for its part, could lead to excessive ethnic concentration, to the detriment of the legitimacy of the federal centre in Moscow and the overall governability of the country – including through the destruction of the critical informational feedback to the centre provided by citizens and local governments in decentralized regimes.

Critically, because there is no felt – instinctual or cultural, rather than intellectual – understanding of how federalism works in any of the post-Soviet states – most of which are not only unitary but indeed hyper-unitary states, built on strict ‘verticals’ of power – it is perhaps appropriate (if not inevitable) that Russia should end up, through iteration and trial and error (the only way of doing policy in Russia), with what the Indians call a federal system with unitary characteristics.

Thesis 3: Mentality is critical to the future of Russia. There once was a ‘Soviet person.’ But what is a ‘Russian’ person, mentally, in the post-Soviet context? Answer: He or she is still being moulded. The Soviet collapse left Russians with at least three types of anomie or general disorientation – strategic, moral and, to be sure, in identity. All three species must be reckoned with – not with fetishistic searches for single national ideas, but rather through deliberate investments in real institutions and public achievements, and through long-term, patient investment in the legitimation of these institutions and achievements, both inside Russia and, to a lesser degree, internationally. Indeed, part of this investment and legitimation must involve the fostering of a far deeper and more robust policy culture in Russia’s intelligentsia, among its still-venerable specialists in various professional disciplines, and for its younger people, who are both the future algorithm-makers and drivers of the feedback mechanisms that are essential to the effective governance of the country. Such a policy culture is dangerously underdeveloped in today’s Russia, which militates against effective pivots to either of the argumentative or algorithmic traditions, and indeed against the creation of a uniquely Russian hybrid governance this century.

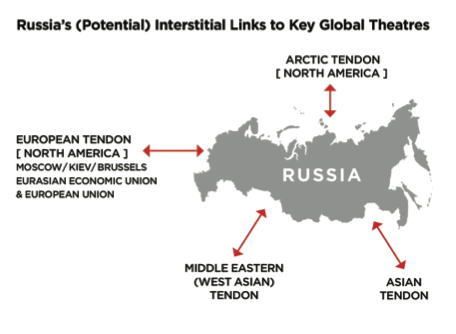

Russia has an opportunity to play a pivotal role in constructing a wide array of interstitial bridges and mechanisms that would help both to give its strategic doctrines greater and more constructive focus, and to drive the country’s institutional and economic development this century.

Thesis 4: What of Russia and Europe this century? The conflict between the West (especially Europe) and Russia that erupted over Ukraine in 2014 and that endures, without foreseeable resolution and in multiplying manifestations in several geographic theatres, can be properly and fundamentally understood as having originated in what I would call an ‘interstitial problem’ – that is, as the result of two regional regimes and geopolitical gravities (the EU to the west and Russia or, more loosely, the Eurasian Economic Union to the east) pulling ferociously, in opposite directions, on a poorly governed space (Ukraine), with weak institutions and unstable legitimacy at its own centre (the said problem of the ‘youth’ or ‘newness’ of all post-Soviet states). How can this be fixed? Answer: by creating, to the extent possible, a ‘Europe 2.0’ framework that interstitially – and tendon-like – binds Moscow with Brussels, or indeed the Eurasian and European planes, via Kiev. The ‘thickness’ of the binding mechanisms may well be de minimi s to start, comprising strictly confidence- or trust-building measures and renewed economic exchange, and evolving over time to bona fide security and political arrangements.

To be sure, with the EU significantly weakened by several concurrent crises (Brexit, refugees, economic stasis, the Ukrainian crisis and Turkish authoritarianism at its borders, the growing presence of Eurosceptic governments on the Continent, and now the Catalan crisis), an emerging strategic perspective from Moscow would seem to be that the ‘European’ option or pivot is now no longer on the table for Russia, even if the vision of constructing a common space between Lisbon and Vladivostok has been, with varying degrees of intensity and coherence, in the strategic psyche of, and expressed in many public statements by, Russian leaders going back to Mikhail Gorbachev (‘Big Europe’) in the late Soviet period through to Vladimir Putin from the early 2000s.

As Europe 1.0 transforms, it seems inevitable that, if peace is to be maintained on the continent, and if Russia is to avoid accidental or even narcissistic isolation and find economic and intellectual openings to Europe, then this Europe 2.0, although facially improbable today, will still have to be ‘invented’ and engineered. As such, there is a distinct strategic opportunity here for Moscow, if it is smart and plays its cards properly, to play a key role in its formulation and erection. Indeed, as Russia, on top of its juxtaposition with the EU, shares borders with several existing, emerging or potential economic and political blocs or international regimes in Asia-Pacific, the Middle East and even, via the melting Arctic, North America (a juxtaposition still underappreciated in North American capitals), Russia has an opportunity to play a pivotal role in constructing a wide array of interstitial bridges and mechanisms that would help both to give its strategic doctrines greater and more constructive focus, and to drive the country’s institutional and economic development this century. Moreover, to the extent that collision between two or more of these international blocs or regimes may, as with the Ukrainian case, lead to conflict – including, in extreme scenarios, nuclear conflict early this century – the opportunity for intellectual and strategic leadership in such interstitial ‘knitting,’ as it were, by Russia assumes a world-historical character.

Thesis 5: Russia has a serious succession problem. If this is not negotiated properly and carefully, it could result in civil conflict or chaos, and even the breakup of the country into several parts. (This is a fact that, as mentioned, is deeply misunderstood outside of Russia.) The absence of ‘argumentative’ institutions in Russia, including the peculiar weakness and superficiality of its political parties, means that the identity of, and nature of the contest and process for determining, the next President and other strategic leaders of Russia are not uncontroversially clear. This, again, is not a question of democratic fetish, but indeed one about the ability of the centre in Moscow to project legitimacy across the entire gigantic territory and population of the country. In the absence of a process deemed legitimate and a persona who, in succession to President Putin, is able to command the agreement of the masses to be governed by him (or her), there is a non-negligible risk of civil destabilization of the country. What’s more, should the presidency end more suddenly, for whatever reason, then the country could be seriously destabilized, as the process of relegitimation of the centre in succession will not have been triggered in time.

It is in the interest of Russian leaders to make the succession process extremely plain to the Russian people immediately. It is also manifestly in the interest of outside countries to understand this succession challenge – not least in order to be disabused of any interest in destabilizing the Russian leadership artificially, in the knowledge that a weak governing legitimacy in the aftermath of President Putin (or any Russian president, for that matter) could create not only wholesale chaos in Russia, but indeed major shockwaves in global stability (beginning at Russia’s 14 land and three maritime borders, and radiating outward).

Thesis 6: The creation of a true policy and political elite in the Singaporean or Chinese algorithmic idiom requires significant, long-term investment in education, and the creation of top-tier educational institutions, from kindergarten to the post-secondary levels. The USSR, for all its pathologies, obviously possessed such institutions (including ‘policy’ and administration academies through its Higher Party School). Russia, as a new state, does not. On top of world-class institution-building in education, Russia must, in order to improve the feedback mechanisms of the argumentative tradition, invest in, and deliver, renewed institutions of politics (including federalism), economics (including credible property rights protection), the judiciary (including serious judicial protection of the legitimate constitutional powers of different levels of government), as well as in other spheres of Russian social life (including the religious sphere).

Thesis 7: How to solve the Ukraine conflict and, by extension, Russia’s conflict with the West? We have discussed this extensively in past issues of GB . Moreover, 21CQ has itself, for the last three and a half years, been leading the track 1.5 work around the world, in leading capitals on three continents – from Moscow and Kiev to Paris, Washington, Ottawa and New Delhi – to find ‘exit’ algorithms for this conflict. The recent surge in interest in a peacekeeper-led exit from the conflict has direct roots in 21CQ’s work since the days immediately after the Ukrainian revolution, the Crimean annexation and the start of the Donbass war.

Still, at the time of this writing, I confess that the window for any clean, comprehensive resolution of this conflict may by now have passed (something that both leading Russians and Ukrainians know fairly well, even if some Western analysts may not yet). In 2014 and 2015, a winning algorithm for resolution, in my judgement, would have seen the insertion into the Donbass region (at the ceasefire line and along the Russo-Ukrainian border) of neutral peacekeepers (led by peacekeepers from Asian countries – non-NATO, but also not from the post-Soviet space – that are respected in both Ukraine and Russia), constitutional reform in Ukraine (including possible federalization in toto – recalling the aforementioned need for most post-Soviet states to decentralize or federalize – and/or special status or special economic zones for several regions of the south and east of Ukraine, in concert with the enshrinement of an Australian-style indissolubility clause for the Ukrainian union in the national constitution), and, finally, strong guarantees regarding the permanent non-membership of Ukraine in NATO (including through a possible UN Security Council resolution). These steps would have been accompanied by the removal (at least by the EU) of economic sanctions not related to Crimea.

Today, the paradox of the Ukraine conflict is as follows: Ukraine cannot succeed economically or even strategically without re-engagement with Russia (no amount of Western implication or goodwill will make up for the loss of Russian engagement); Russia cannot succeed (or modernize) economically without the removal of sanctions, and without a deeper reconnection with the EU; and the coherence of Europe suffers for the disengagement and economic weakness of Russia, as well as for the Ukrainian crisis at its borders. No resolution is currently in sight because both Ukraine and Russia remain ‘two houses radicalized’ in respect of this conflict, with key Western capitals not understanding (or believing) sufficiently the finer details of the conflict and its genesis, with Moscow gradually becoming ‘used to’ the economic sanctions and the renaissance of tensions with the West (including in its domestic political narrative), and with the government in Kiev increasingly weak and unstable, and therefore unable either to deliver major domestic reforms or make decisive moves to resolve the Donbass war. In addition, the accelerating disintegration of the Middle East, in Syria and beyond, has grossly complicated any prospects of exit from the crisis – effectively fusing together the European theatre with the Western Asian theatre. (The crisis in North Korea, if it erupts into war, may turn out to be yet another theatre of secondary conflict between Russia and Western countries.)

Leaving aside Russia’s succession issue, there is a clear risk of systemic collapse in one or both of Ukraine (for political and/or economic reasons) and Russia (more likely for economic reasons) in the near to medium term. Collapse of either country’s system would be devastating for both countries, as well as for European and global stability (including in nuclear terms). Ukrainian collapse would accelerate the slide toward direct military confrontation between Russia and NATO.

Only a systemic solution is possible to the conflict, and yet I do not believe that Europe is sufficiently strong and united at present to be able to drive a solution. The US, for its part, is politically unable to relieve Russia of sanctions, and so Moscow will not see much utility in the American play except insofar as Washington can play a role in pushing or incentivizing Kiev to make or not make certain moves. Therefore, the ‘solution’ to the conflict can for now only be partial , rather than general and global. In my assessment, it is Asia – particularly China, or perhaps India – and not Western countries that must play the pivotal role here. (Indeed, Moscow could cleverly seduce both New Delhi and Beijing, geopolitical rivalry between the two oblige, to play co-leads in this partial resolution.) The two key elements of the winning partial algorithm could include:

i. to stop the fighting, neutral peacekeepers from leading Asian countries (starting with China or India, but perhaps also Indonesia and Singapore) and a police or constabulary force in the Donbass region, as well as along the Russia-Ukraine border; and

ii. to rebuild and stabilize Ukraine, reconstitute the Ukrainian-Russian-European relationship (in new, interstitial terms), heavy Russian state reinvestment into all of Ukraine, and, concurrently, heavy Ukrainian reinvestment into all of Russia, with both countries combining economically to rebuild the Donbass in particular – all with significant loan guarantees from the new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the new BRICS bank, the Chinese and Indian governments proper, and with opportunistic but possibly subordinate participation by the EU (including through Donbass-specific sanctions relief for Russia), the US, Canada and other units and countries.

Issues like NATO guarantees of non-membership for Ukraine and also the future status of Crimea, as well as global sanctions relief for Russia, all require deep and coherent Western engagement, and so are not on the table for the foreseeable future. The above algorithm also insulates the Ukraine conflict somewhat from the Middle Eastern conflict – or, in other words, delinks, diplomatically, the resolution of the Ukraine conflict from that of the even less soluble Middle Eastern theatre.

Thesis 8: Despite its cultural dynamism and deep intelligentsia, Russia’s economy is unacceptably primitive. Natural resources and energy products will continue to dominate this economy for the foreseeable future, just as they did in the last century – which also makes the national economy and the federal and regional budgets exceedingly vulnerable to significant commodity price swings (with no serious countervailing revenue sources in sight). However, what appears to be missing in Russia today, in addition to proper investment in infrastructure across the territory, is a matching of state purpose, deep entrepreneurial talent, and large-scale venture investment in export-oriented sectors outside of commodities – the predictable result of which is a disproportionate dearth of great, global Russian companies and brands (again, outside of the commodities sector). And so here the model for Russia is likely Israel, from which algorithmic countries like Singapore have borrowed heavily in fashioning their own state-private sector models. Applied to the Russian context, that model would seem to commend two critical reform vectors for Russian industrial policy: first, the creation of a handful of national educational, military or technical-scientific institutions (elite or quasi-elite) that are able to develop an achievement-oriented mindset among Russia’s young adults, as well as lifelong friendships and ‘thick’ professional networks among these people; and second, assurances that the Russian state, with minimal bureaucratic friction, is positively disposed to giving entrepreneurs from the ‘class’ of young achievers passing through these institutions a first contract (procurement), initial funding, or indeed future contracts of scale.

Thesis 9: A key aspect of the argumentative paradigm of governance is that the marginal value of human life is greater in the societal geist of argumentative states than in that of algorithmic states, given the high importance ascribed to procedure and feedback to political power from citizens. This larger marginal value of life is given expression through very robust constitutional and cultural bulwarks for protecting human life, which is viewed in absolute terms. By contrast, algorithmic states, especially of the Asian ilk, may, at least implicitly, attach greater instrumentality to human life – that is, viewing human life as being in the service of, or subordinating to, the preferred Asian freedom: not freedom from government repression, but instead freedom from chaos. The Singaporeans and Malaysians, for instance, refer to the fear of chaos and death, in the Hokkien idiom, as kiasi, in response to which extreme or radical private or public measures may occasionally need to be taken: consider the death penalty or, more commonly, the use of standing emergency laws and measures. An individual life or, short of that, what Westerners view as fundamental rights, may, on this logic, need to be compromised or traded in the service of the more important general protection and freedom from chaos. This may lead to swifter and less compunctious resort to peremptory punishment (like the death penalty) for what might, in the argumentative states of the West, be considered micro-torts (including some drug offences), or to draconian emergency laws and prerogatives in response to perceived threats of a political ilk (including terrorism).

The policy implication for Russia is that the ‘care’ given to each individual Russian citizen (or the value of the individual Russian life) can be improved indirectly or circuitously – that is, that improvement may come not necessarily through direct legislative, regulatory, judicial or jurisprudential changes (and certainly not from well-intentioned rhetoric and nice proclamations), but indeed through investment in some of the ‘argumentative’ institutions themselves – including through improvement of the health and sophistication of the various estates, from political parties to Russian civil society (and even Russian businesses), that provide the feedback from the governed to the governors, thereby removing some of the edge from the bureaucratic leviathan as it touches the human condition in all corners of the country.

On this same logic of increasing the value of individual life, increased investment in argumentative institutions can arguably lead to better, more porous relations between the ethnic Russian majority and the many important minorities of Russia – from the Tatars, Chechens and Ingush, to the Jews, Ukrainians and Armenians.

The key question for Russian statecraft in the early 21st century is whether, allowing for limited corruption as an informal institution, the governing classes can move the country to greater wealth and stability, improving meaningfully and substantially the daily lives of citizens (and the perceived value of those lives).

Thesis 10: Excellent Russian public policy and administration will never wholly eliminate Russian public corruption. Russian corruption – narrowly conceived – can, to a limited extent, be seen as an informal institution of Russian state and society. In this, Russia is not that far removed from many countries and societies around the world, including the more advanced countries of Northeast and Southeast Asia (or also Israel and India). Instead, the key question for Russian statecraft in the early 21st century is whether, allowing for limited corruption as an informal institution, the governing classes can move the country to greater wealth and stability, improving meaningfully and substantially the daily lives of citizens (and, as mentioned above, the perceived value of those lives). Evidently, it would be best to improve the lot of citizens with negligible corruption, as is the standard in the argumentative states of North America or Western Europe. And just as manifestly, it is unacceptable to remain corrupt while the quality of life for Russians stagnates or deteriorates. But the story of leading algorithmic pioneers like Lee Kuan Yew or, on a more serious scale, Deng Xiaoping, is not one of perfunctory non-corruption – as that would likely remove all lubrication from the administrative system, institutional inertia oblige – but instead public achievement and policy-administrative delivery to citizens in the context of significant corruption that, over time, enjoys a demonstrably downward trajectory.

The paradox of Russian public administration as it applies to matters military versus non-military is instructive in this regard. In Russia, short-term military or emergency orders or decrees (or algorithms) are typically dispatched with remarkable rapidity and efficacy (demonstrating a prodigious national organizational ability to scale very quickly). And yet long-term plans and projects (including military procurement) are delivered with notorious inefficiency, slowness and procedural corruption. For these long-term projects, presidential decrees are issued, with considerable regularity, even to repeat or remind the bureaucratic system about the existence of still-unfulfilled past presidential decrees. Quaere : What type of strategic, policy and administrative seriousness and quality would Russia need to be able to deliver on the long term but prosaic with the same inspiration with which it delivers on various emergency prerogatives? Can the country maintain its focus (and cool)? Can it develop a professional leadership class across the country, at different levels of public power, that has a ‘synoptic vision’ that is sufficiently vast to incorporate Russia’s endless complexity while constantly iterating and refining this vision through citizen input and feedback? Can this class of people both populate and in turn discipline the administrative apparatus of the state? And, whatever the compromises it may require en route, can it deliver the goods for the Russian people?

Irvin Studin is Editor-in-Chief & Publisher of Global Brief Magazine.

(ILLUSTRATION: ARMANDO VEVE)

- Winter 2018

- Irvin Studin

- Russian strategy

You Might also Like

You might also enjoy this in gb.

SUBSCRIBE TODAY TO GB

Matador Original Series

The story behind dachas, russia's storybook country cottages.

I f you ever decide to visit Russia, you’ll likely be inclined to visit the well-known urban hubs, such as St. Petersburg and Moscow . And while these cities will definitely give you a large sampling of the nation’s culture, you’d still be missing a key slice of Russian life: the dacha.

Dachas are not just a type of building in Russia; they are a cultural institution. These cottage-like holiday homes often exist in tiny villages or colonies, in both suburban and rural areas. Dachas are not defined by a specific architectural style — rather, they are defined by their function. Dachas are a place to temporarily escape urban life and reconnect with nature by growing your own food, observing the surrounding wildlife, and returning to a simpler mode of existence.

The history of dachas

Photo: Alesya Miloslavskaya /Shutterstock

To understand why dachas are such an important tradition in Russian culture, we need to travel backward about 400 years. The word dacha actually comes from the word davat , which means “to give.” Initially, dachas were small plots of land, given as gifts by the Russian tsar throughout the 1600s. It is unclear which tsar specifically began this practice, but Peter the Great is credited with endowing dachas with a special significance.

Peter the Great is an all-around key figure in Russian history; he expanded Russia from a tsardom into an empire, and he integrated Western Enlightenment ideals into Russian culture. During Peter’s rule from 1682 to 1725, the upper class and nobility used their dachas to host social gatherings, holiday retreats, parties, and fireworks displays.

The concept of the dacha gained traction throughout the 1700s and 1800s. By the time the 20th century came, dachas were a status symbol for Russia’s middle and upper classes. Additionally, dachas embodied romantic connotations; they were seen as inspirational settings for Russian artists, writers, playwrights, and poets to produce their work.

Unfortunately, this “golden age” of dachas didn’t last long. Russia was embroiled in conflict for the first half of the 20th century, with World War I, the Bolshevik Revolution, and World War II. Many Russians lost their quaint holiday homes during this time period.

However, the idea of the dacha did not die altogether. It transformed.

Photo: SariMe /Shutterstock

The dacha took on a more utilitarian connotation in the aftermath of WWII. By then, Russia was under Soviet rule and supply shortages ravaged the country. Citizens thought that if they could purchase small plots of land outside the city, then they could be self-sufficient and grow their own food. The Soviet rulers caught on to this movement, and soon they imposed regulations limiting the amount of land that a single person could own. These rules were made so that civilians could not live on their rural dacha plots permanently — the state needed a strong labor force dwelling within the cities.

Thus, “dacha settlements” became popular. These were communities of personal rudimentary farms, with tiny houses standing right next to one another.

In the 1980s, state-imposed dacha regulations were lifted and civilians could purchase larger plots of land. This gave rise to the trend of dacha villages, and people could be creative in the construction of their home away from home.

Peredelkino

Photo: Free Wind 2014 /Shutterstock

Peredelkino is by far Russia’s most famous dacha village, sitting just 10 miles southwest of Moscow. Before the Bolshevik Revolution, this piece of land was part of a private family estate. However, it was usurped by the government in the 1930s, then gifted to the Writers’ Union following the suggestion of famous Soviet writer and political activist, Maxim Gorky. Within a couple of years, the state constructed 50 wooden cottages for the new Peredelkino dacha village.

Some of Russia’s most famous modern writers lived in Peredelkino, including Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Arseny Tarkovsky, and Boris Pasternak. However, having state-backed accommodations had its pitfalls. The writers of Peredelkino were pressured to conform to pro-Soviet thematic material and commit to a state-approved style of writing. If writers did not adhere to these tenets, the consequences could be deadly. In fact, the acclaimed Russian-Jewish writer Isaac Babel was arrested in his Peredelkino dacha in 1939 for “anti-Soviet activities,” and was executed in 1940.

In spite of these constraints, the artistic spirit of Peredelkino is undeniable. Many notable Russian works were created here (at least in part), including Pasternak’s Nobel Prize-winning Doctor Zhivago . The wooden dachas are charming and humble, like gingerbread houses in the woods of a fairytale. When visiting, it’s easy to understand how the peaceful, natural surroundings provided fuel for the writers’ imagination.

Dachas today

Photo: Mohylenets Vitalii /Shutterstock

Today, dachas are something of a blend between their 1800s and Soviet-era definitions. While they retain aspects of utilitarianism and independence (and most dachas still contain small farms), dachas have increased in both size and luxury. For instance, the barebones abodes of Peredelkino are now surrounded by the dachas of “new Russian” billionaires: fit with rooftop terraces and private swimming pools.

However, these “mega-dachas” are by no means the norm. According to the Moscow Times in 2019, it is estimated that nearly 60 million Russians own dachas (almost half the entire population). Most contemporary dachas are owned by middle- and upper-class Russians, and they contain modern amenities such as electricity and indoor plumbing. People go to their dachas to escape the city on weekends and to spend holidays in the summer. Additionally, most dachas are located near a lake or river, so owners can enjoy activities like swimming and fishing.

More like this

Trending now, the most epic treehouses you can actually rent on airbnb, 21 of the coolest airbnbs near disney world, orlando, stay at these 13 haunted airbnbs for a truly terrifying halloween night, the top luxury forest getaways in the us, the 19 most beautiful converted churches you can stay in around the world on airbnb, discover matador, adventure travel, train travel, national parks, beaches and islands, ski and snow.

We use cookies for analytics tracking and advertising from our partners.

For more information read our privacy policy .

Matador's Newsletter

Subscribe for exclusive city guides, travel videos, trip giveaways and more!

You've been signed up!

Follow us on social media.

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Meaning of thesis in English

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

- I wrote my thesis on literacy strategies for boys .

- Her main thesis is that children need a lot of verbal stimulation .

- boilerplate

- composition

- corresponding author

- dissertation

- essay question

- peer review

You can also find related words, phrases, and synonyms in the topics:

thesis | Intermediate English

Examples of thesis, collocations with thesis.

These are words often used in combination with thesis .

Click on a collocation to see more examples of it.

Translations of thesis

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

food remaining after a meal

Simply the best! (Ways to describe the best)

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- English Noun

- Intermediate Noun

- Collocations

- Translations

- All translations

To add thesis to a word list please sign up or log in.