Hill Street Studios/Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

In rhetoric, refutation is the part of an argument in which a speaker or writer counters opposing points of view. Also called confutation .

Refutation is "the key element in debate," say the authors of The Debater's Guide (2011). Refutation "makes the whole process exciting by relating ideas and arguments from one team to those of the other" ( The Debater's Guide , 2011).

In speeches, refutation and confirmation are often presented "conjointly with one another" (in the words of the unknown author of Ad Herrenium ): support for a claim ( confirmation ) can be enhanced by a challenge to the validity of an opposing claim ( refutation ).

In classical rhetoric , refutation was one of the rhetorical exercises known as the progymnasmata .

Examples and Observations

"Refutation is the part of an essay that disproves the opposing arguments. It is always necessary in a persuasive paper to refute or answer those arguments. A good method for formulating your refutation is to put yourself in the place of your readers, imagining what their objections might be. In the exploration of the issues connected with your subject, you may have encountered possible opposing viewpoints in discussions with classmates or friends. In the refutation, you refute those arguments by proving the opposing basic proposition untrue or showing the reasons to be invalid...In general, there is a question about whether the refutation should come before or after the proof . The arrangement will differ according to the particular subject and the number and strength of the opposing arguments. If the opposing arguments are strong and widely held, they should be answered at the beginning. In this case, the refutation becomes a large part of the proof . . .. At other times when the opposing arguments are weak, the refutation will play only a minor part in the overall proof." -Winifred Bryan Horner, Rhetoric in the Classical Tradition . St. Martin's, 1988

Indirect and Direct Refutation

- "Debaters refute through an indirect means when they use counter-argument to attack the case of an opponent. Counter-argument is the demonstration of such a high degree of probability for your conclusions that the opposing view loses its probability and is rejected... Direct refutation attacks the arguments of the opponent with no reference to the constructive development of an opposing view...The most effective refutation, as you can probably guess, is a combination of the two methods so that the strengths of the attack come from both the destruction of the opponents' views and the construction of an opposing view." -Jon M. Ericson, James J. Murphy, and Raymond Bud Zeuschner, The Debater's Guide , 4th ed. Southern Illinois University Press, 2011

- "An effective refutation must speak directly to an opposing argument. Often writers or speakers will claim to be refuting the opposition, but rather than doing so directly, will simply make another argument supporting their own side. This is a form of the fallacy of irrelevance through evading the issue." -Donald Lazere, Reading and Writing for Civic Literacy: The Critical Citizen's Guide to Argumentative Rhetoric . Taylor & Francis, 2009

Cicero on Confirmation and Refutation

"[T]he statement of the case . . . must clearly point out the question at issue. Then must be conjointly built up the great bulwarks of your cause, by fortifying your own position, and weakening that of your opponent; for there is only one effectual method of vindicating your own cause, and that includes both the confirmation and refutation. You cannot refute the opposite statements without establishing your own; nor can you, on the other hand, establish your own statements without refuting the opposite; their union is demanded by their nature, their object, and their mode of treatment. The whole speech is, in most cases, brought to a conclusion by some amplification of the different points, or by exciting or mollifying the judges; and every aid must be gathered from the preceding, but more especially from the concluding parts of the address, to act as powerfully as possible upon their minds, and make them zealous converts to your cause." -Cicero, De Oratore , 55 BC

Richard Whately on Refutation

"Refutation of Objections should generally be placed in the midst of the Argument; but nearer the beginning than the end. If indeed very strong objections have obtained much currency, or have been just stated by an opponent, so that what is asserted is likely to be regarded as paradoxical , it may be advisable to begin with a Refutation." -Richard Whately, Elements of Rhetoric , 1846)

FCC Chairman William Kennard's Refutation

"There will be those who say 'Go slow. Don't upset the status quo.' No doubt we will hear this from competitors who perceive that they have an advantage today and want regulation to protect their advantage. Or we will hear from those who are behind in the race to compete and want to slow down deployment for their own self-interest. Or we will hear from those that just want to resist changing the status quo for no other reason than change brings less certainty than the status quo. They will resist change for that reason alone. So we may well hear from a whole chorus of naysayers. And to all of them, I have only one response: we cannot afford to wait. We cannot afford to let the homes and schools and businesses throughout America wait. Not when we have seen the future. We have seen what high capacity broadband can do for education and for our economy. We must act today to create an environment where all competitors have a fair shot at bringing high capacity bandwidth to consumers—especially residential consumers. And especially residential consumers in rural and underserved areas." -William Kennard, Chairman of the FCC, July 27, 1998

Etymology: From the Old English, "beat"

Pronunciation: REF-yoo-TAY-shun

- Confirmation in Speech and Rhetoric

- Usage and Examples of a Rebuttal

- What Is the Straw Man Fallacy?

- Elenchus (argumentation)

- Definition and Examples of Progymnasmata in Rhetoric

- Arrangement in Composition and Rhetoric

- The Parts of a Speech in Classical Rhetoric

- Definition and Examples of Procatalepsis in Rhetoric

- Narratio in Rhetoric

- Reductio Ad Absurdum in Argument

- Oration (Classical Rhetoric)

- What Is Digression?

- Learn How to Use Extended Definitions in Essays and Speeches

- What Is a Compound Verb?

- Invention (Composition and Rhetoric)

- listeme (words)

Definition of Refutation

Types of refutation, refutation through evidence, refutation through logic, refutation through exposing discrepancies, examples of refutation in literature, example #1: elements of rhetoric (by richard whately).

“If indeed very strong objections have obtained much currency, or have been just stated by an opponent, so that what is asserted is likely to be regarded as paradoxical, it may be advisable to begin with a Refutation.”

Example #2: Remarks made to the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners, Seattle, Washington (By William Kennard, Chairman of the FCC)

“So we may well hear from a whole chorus of naysayers. And to all of them I have only one response: we cannot afford to wait. We cannot afford to let the homes and schools and businesses throughout America wait. Not when we have seen the future. We have seen what high capacity broadband can do for education and for our economy. We must act today to create an environment where all competitors have a fair shot at bringing high capacity bandwidth to consumers—especially residential consumers. And especially residential consumers in rural and underserved areas.”

Function of Refutation

Post navigation.

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

A Guide to Rebuttals in Argumentative Essays

4-minute read

- 27th May 2023

Rebuttals are an essential part of a strong argument. But what are they, exactly, and how can you use them effectively? Read on to find out.

What Is a Rebuttal?

When writing an argumentative essay , there’s always an opposing point of view. You can’t present an argument without the possibility of someone disagreeing.

Sure, you could just focus on your argument and ignore the other perspective, but that weakens your essay. Coming up with possible alternative points of view, or counterarguments, and being prepared to address them, gives you an edge. A rebuttal is your response to these opposing viewpoints.

How Do Rebuttals Work?

With a rebuttal, you can take the fighting power away from any opposition to your idea before they have a chance to attack. For a rebuttal to work, it needs to follow the same formula as the other key points in your essay: it should be researched, developed, and presented with evidence.

Rebuttals in Action

Suppose you’re writing an essay arguing that strawberries are the best fruit. A potential counterargument could be that strawberries don’t work as well in baked goods as other berries do, as they can get soggy and lose some of their flavor. Your rebuttal would state this point and then explain why it’s not valid:

Read on for a few simple steps to formulating an effective rebuttal.

Step 1. Come up with a Counterargument

A strong rebuttal is only possible when there’s a strong counterargument. You may be convinced of your idea but try to place yourself on the other side. Rather than addressing weak opposing views that are easy to fend off, try to come up with the strongest claims that could be made.

In your essay, explain the counterargument and agree with it. That’s right, agree with it – to an extent. State why there’s some truth to it and validate the concerns it presents.

Step 2. Point Out Its Flaws

Now that you’ve presented a counterargument, poke holes in it . To do so, analyze the argument carefully and notice if there are any biases or caveats that weaken it. Looking at the claim that strawberries don’t work well in baked goods, a weakness could be that this argument only applies when strawberries are baked in a pie.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Step 3. Present New Points

Once you reveal the counterargument’s weakness, present a new perspective, and provide supporting evidence to show that your argument is still the correct one. This means providing new points that the opposer may not have considered when presenting their claim.

Offering new ideas that weaken a counterargument makes you come off as authoritative and informed, which will make your readers more likely to agree with you.

Summary: Rebuttals

Rebuttals are essential when presenting an argument. Even if a counterargument is stronger than your point, you can construct an effective rebuttal that stands a chance against it.

We hope this guide helps you to structure and format your argumentative essay . And once you’ve finished writing, send a copy to our expert editors. We’ll ensure perfect grammar, spelling, punctuation, referencing, and more. Try it out for free today!

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a rebuttal in an essay.

A rebuttal is a response to a counterargument. It presents the potential counterclaim, discusses why it could be valid, and then explains why the original argument is still correct.

How do you form an effective rebuttal?

To use rebuttals effectively, come up with a strong counterclaim and respectfully point out its weaknesses. Then present new ideas that fill those gaps and strengthen your point.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

5-minute read

Free Email Newsletter Template (2024)

Promoting a brand means sharing valuable insights to connect more deeply with your audience, and...

6-minute read

How to Write a Nonprofit Grant Proposal

If you’re seeking funding to support your charitable endeavors as a nonprofit organization, you’ll need...

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

English Current

ESL Lesson Plans, Tests, & Ideas

- North American Idioms

- Business Idioms

- Idioms Quiz

- Idiom Requests

- Proverbs Quiz & List

- Phrasal Verbs Quiz

- Basic Phrasal Verbs

- North American Idioms App

- A(n)/The: Help Understanding Articles

- The First & Second Conditional

- The Difference between 'So' & 'Too'

- The Difference between 'a few/few/a little/little'

- The Difference between "Other" & "Another"

- Check Your Level

- English Vocabulary

- Verb Tenses (Intermediate)

- Articles (A, An, The) Exercises

- Prepositions Exercises

- Irregular Verb Exercises

- Gerunds & Infinitives Exercises

- Discussion Questions

- Speech Topics

- Argumentative Essay Topics

- Top-rated Lessons

- Intermediate

- Upper-Intermediate

- Reading Lessons

- View Topic List

- Expressions for Everyday Situations

- Travel Agency Activity

- Present Progressive with Mr. Bean

- Work-related Idioms

- Adjectives to Describe Employees

- Writing for Tone, Tact, and Diplomacy

- Speaking Tactfully

- Advice on Monetizing an ESL Website

- Teaching your First Conversation Class

- How to Teach English Conversation

- Teaching Different Levels

- Teaching Grammar in Conversation Class

- Members' Home

- Update Billing Info.

- Cancel Subscription

- North American Proverbs Quiz & List

- North American Idioms Quiz

- Idioms App (Android)

- 'Be used to'" / 'Use to' / 'Get used to'

- Ergative Verbs and the Passive Voice

- Keywords & Verb Tense Exercises

- Irregular Verb List & Exercises

- Non-Progressive (State) Verbs

- Present Perfect vs. Past Simple

- Present Simple vs. Present Progressive

- Past Perfect vs. Past Simple

- Subject Verb Agreement

- The Passive Voice

- Subject & Object Relative Pronouns

- Relative Pronouns Where/When/Whose

- Commas in Adjective Clauses

- A/An and Word Sounds

- 'The' with Names of Places

- Understanding English Articles

- Article Exercises (All Levels)

- Yes/No Questions

- Wh-Questions

- How far vs. How long

- Affect vs. Effect

- A few vs. few / a little vs. little

- Boring vs. Bored

- Compliment vs. Complement

- Die vs. Dead vs. Death

- Expect vs. Suspect

- Experiences vs. Experience

- Go home vs. Go to home

- Had better vs. have to/must

- Have to vs. Have got to

- I.e. vs. E.g.

- In accordance with vs. According to

- Lay vs. Lie

- Make vs. Do

- In the meantime vs. Meanwhile

- Need vs. Require

- Notice vs. Note

- 'Other' vs 'Another'

- Pain vs. Painful vs. In Pain

- Raise vs. Rise

- So vs. Such

- So vs. So that

- Some vs. Some of / Most vs. Most of

- Sometimes vs. Sometime

- Too vs. Either vs. Neither

- Weary vs. Wary

- Who vs. Whom

- While vs. During

- While vs. When

- Wish vs. Hope

- 10 Common Writing Mistakes

- 34 Common English Mistakes

- First & Second Conditionals

- Comparative & Superlative Adjectives

- Determiners: This/That/These/Those

- Check Your English Level

- Grammar Quiz (Advanced)

- Vocabulary Test - Multiple Questions

- Vocabulary Quiz - Choose the Word

- Verb Tense Review (Intermediate)

- Verb Tense Exercises (All Levels)

- Conjunction Exercises

- List of Topics

- Business English

- Games for the ESL Classroom

- Pronunciation

- Teaching Your First Conversation Class

- How to Teach English Conversation Class

Argumentative Essays: The Counter-Argument & Refutation

An argumentative essay presents an argument for or against a topic. For example, if your topic is working from home , then your essay would either argue in favor of working from home (this is the for side) or against working from home.

Like most essays, an argumentative essay begins with an introduction that ends with the writer's position (or stance) in the thesis statement .

Introduction Paragraph

(Background information....)

- Thesis statement : Employers should give their workers the option to work from home in order to improve employee well-being and reduce office costs.

This thesis statement shows that the two points I plan to explain in my body paragraphs are 1) working from home improves well-being, and 2) it allows companies to reduce costs. Each topic will have its own paragraph. Here's an example of a very basic essay outline with these ideas:

- Background information

Body Paragraph 1

- Topic Sentence : Workers who work from home have improved well-being .

- Evidence from academic sources

Body Paragraph 2

- Topic Sentence : Furthermore, companies can reduce their expenses by allowing employees to work at home .

- Summary of key points

- Restatement of thesis statement

Does this look like a strong essay? Not really . There are no academic sources (research) used, and also...

You Need to Also Respond to the Counter-Arguments!

The above essay outline is very basic. The argument it presents can be made much stronger if you consider the counter-argument , and then try to respond (refute) its points.

The counter-argument presents the main points on the other side of the debate. Because we are arguing FOR working from home, this means the counter-argument is AGAINST working from home. The best way to find the counter-argument is by reading research on the topic to learn about the other side of the debate. The counter-argument for this topic might include these points:

- Distractions at home > could make it hard to concentrate

- Dishonest/lazy people > might work less because no one is watching

Next, we have to try to respond to the counter-argument in the refutation (or rebuttal/response) paragraph .

The Refutation/Response Paragraph

The purpose of this paragraph is to address the points of the counter-argument and to explain why they are false, somewhat false, or unimportant. So how can we respond to the above counter-argument? With research !

A study by Bloom (2013) followed workers at a call center in China who tried working from home for nine months. Its key results were as follows:

- The performance of people who worked from home increased by 13%

- These workers took fewer breaks and sick-days

- They also worked more minutes per shift

In other words, this study shows that the counter-argument might be false. (Note: To have an even stronger essay, present data from more than one study.) Now we have a refutation.

Where Do We Put the Counter-Argument and Refutation?

Commonly, these sections can go at the beginning of the essay (after the introduction), or at the end of the essay (before the conclusion). Let's put it at the beginning. Now our essay looks like this:

Counter-argument Paragraph

- Dishonest/lazy people might work less because no one is watching

Refutation/Response Paragraph

- Study: Productivity increased by 14%

- (+ other details)

Body Paragraph 3

- Topic Sentence : In addition, people who work from home have improved well-being .

Body Paragraph 4

The outline is stronger now because it includes the counter-argument and refutation. Note that the essay still needs more details and research to become more convincing.

Working from home may increase productivity.

Extra Advice on Argumentative Essays

It's not a compare and contrast essay.

An argumentative essay focuses on one topic (e.g. cats) and argues for or against it. An argumentative essay should not have two topics (e.g. cats vs dogs). When you compare two ideas, you are writing a compare and contrast essay. An argumentative essay has one topic (cats). If you are FOR cats as pets, a simplistic outline for an argumentative essay could look something like this:

- Thesis: Cats are the best pet.

- are unloving

- cause allergy issues

- This is a benefit > Many working people do not have time for a needy pet

- If you have an allergy, do not buy a cat.

- But for most people (without allergies), cats are great

- Supporting Details

Use Language in Counter-Argument That Shows Its Not Your Position

The counter-argument is not your position. To make this clear, use language such as this in your counter-argument:

- Opponents might argue that cats are unloving.

- People who dislike cats would argue that cats are unloving.

- Critics of cats could argue that cats are unloving.

- It could be argued that cats are unloving.

These underlined phrases make it clear that you are presenting someone else's argument , not your own.

Choose the Side with the Strongest Support

Do not choose your side based on your own personal opinion. Instead, do some research and learn the truth about the topic. After you have read the arguments for and against, choose the side with the strongest support as your position.

Do Not Include Too Many Counter-arguments

Include the main (two or three) points in the counter-argument. If you include too many points, refuting these points becomes quite difficult.

If you have any questions, leave a comment below.

- Matthew Barton / Creator of Englishcurrent.com

Additional Resources :

- Writing a Counter-Argument & Refutation (Richland College)

- Language for Counter-Argument and Refutation Paragraphs (Brown's Student Learning Tools)

EnglishCurrent is happily hosted on Dreamhost . If you found this page helpful, consider a donation to our hosting bill to show your support!

24 comments on “ Argumentative Essays: The Counter-Argument & Refutation ”

Thank you professor. It is really helpful.

Can you also put the counter argument in the third paragraph

It depends on what your instructor wants. Generally, a good argumentative essay needs to have a counter-argument and refutation somewhere. Most teachers will probably let you put them anywhere (e.g. in the start, middle, or end) and be happy as long as they are present. But ask your teacher to be sure.

Thank you for the information Professor

how could I address a counter argument for “plastic bags and its consumption should be banned”?

For what reasons do they say they should be banned? You need to address the reasons themselves and show that these reasons are invalid/weak.

Thank you for this useful article. I understand very well.

Thank you for the useful article, this helps me a lot!

Thank you for this useful article which helps me in my study.

Thank you, professor Mylene 102-04

it was very useful for writing essay

Very useful reference body support to began writing a good essay. Thank you!

Really very helpful. Thanks Regards Mayank

Thank you, professor, it is very helpful to write an essay.

It is really helpful thank you

It was a very helpful set of learning materials. I will follow it and use it in my essay writing. Thank you, professor. Regards Isha

Thanks Professor

This was really helpful as it lays the difference between argumentative essay and compare and contrast essay.. Thanks for the clarification.

This is such a helpful guide in composing an argumentative essay. Thank you, professor.

This was really helpful proof, thankyou!

Thanks this was really helpful to me

This was very helpful for us to generate a good form of essay

thank you so much for this useful information.

Thank you so much, Sir. This helps a lot!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Unit 6: Argumentative Essay Writing

46 Counterargument and Refutation Development

In an argumentative essay, you need to convince your audience that your opinion is the most valid opinion. To do so, your essay needs to be balanced—it needs an opposing (opposite) viewpoint, known as a counter-argument . Even though you are arguing one side of an issue, you must include what someone from the other side would say. After your opponent’s view, include a refutation to demonstrate why the other point of view is wrong.

Identifying Counterarguments

There are many ways to identify alternative perspectives.

- Have an imaginary dialogue with a "devil's advocate."

- Discuss your topic with a classmate or group of classmates.

- Interview someone who holds the opposite opinion.

- Read about the topic to learn more about different perspectives.

Example Argument

In the conversation below the writer talks to someone with the opposite opinion. Roberto thinks professors should incorporate Facebook into their teaching. Fatima argues the opposing side. This discussion helps the writer identify a counterargument.

Roberto: I think professors should incorporate Facebook into their teaching . Students could connect with each other in and out of the classroom. ( Position and pro-argument )

Fatima : Hmmm… that could work, but I don’t think it’s a very good idea . Not all students are on Facebook. Some students don’t want to create accounts and share their private information. ( Counterargument )

Roberto: Well…. students could create an account that’s just for the course.

Fatima : Maybe, but some students won’t want to use their personal accounts and would find it troublesome to create an additional “temporary class account.” Plus, I think more young people prefer Instagram.

Example Counterargument paragraph

Roberto used information from the conversation and evidence from sources to write the counterargument paragraph. This paragraph concludes with a concession of validity and is followed by the refutation.

Example Refutation paragraph

Counterargument and refutation stems.

Below are the stems organized in a table.

|

| |

|---|---|

| of the topic you are against. | |

|

| |

Watch this video

The video refers to counterarguments as “counterclaims” and refutations as “rebuttals.

From: Karen Baxley

someone who presents a counterargument; someone who pretends to be against the issue for the sake of discussing the issue

Academic Writing I Copyright © by UW-Madison ESL Program is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

21 Argument, Counterargument, & Refutation

In academic writing, we often use an Argument essay structure. Argument essays have these familiar components, just like other types of essays:

- Introduction

- Body Paragraphs

But Argument essays also contain these particular elements:

- Debatable thesis statement in the Introduction

- Argument – paragraphs which show support for the author’s thesis (for example: reasons, evidence, data, statistics)

- Counterargument – at least one paragraph which explains the opposite point of view

- Concession – a sentence or two acknowledging that there could be some truth to the Counterargument

- Refutation (also called Rebuttal) – sentences which explain why the Counterargument is not as strong as the original Argument

Consult Introductions & Titles for more on writing debatable thesis statements and Paragraphs ~ Developing Support for more about developing your Argument.

Imagine that you are writing about vaping. After reading several articles and talking with friends about vaping, you decide that you are strongly opposed to it.

Which working thesis statement would be better?

- Vaping should be illegal because it can lead to serious health problems.

Many students do not like vaping.

Because the first option provides a debatable position, it is a better starting point for an Argument essay.

Next, you would need to draft several paragraphs to explain your position. These paragraphs could include facts that you learned in your research, such as statistics about vapers’ health problems, the cost of vaping, its effects on youth, its harmful effects on people nearby, and so on, as an appeal to logos . If you have a personal story about the effects of vaping, you might include that as well, either in a Body Paragraph or in your Introduction, as an appeal to pathos .

A strong Argument essay would not be complete with only your reasons in support of your position. You should also include a Counterargument, which will show your readers that you have carefully researched and considered both sides of your topic. This shows that you are taking a measured, scholarly approach to the topic – not an overly-emotional approach, or an approach which considers only one side. This helps to establish your ethos as the author. It shows your readers that you are thinking clearly and deeply about the topic, and your Concession (“this may be true”) acknowledges that you understand other opinions are possible.

Here are some ways to introduce a Counterargument:

- Some people believe that vaping is not as harmful as smoking cigarettes.

- Critics argue that vaping is safer than conventional cigarettes.

- On the other hand, one study has shown that vaping can help people quit smoking cigarettes.

Your paragraph would then go on to explain more about this position; you would give evidence here from your research about the point of view that opposes your own opinion.

Here are some ways to begin a Concession and Refutation:

- While this may be true for some adults, the risks of vaping for adolescents outweigh its benefits.

- Although these critics may have been correct before, new evidence shows that vaping is, in some cases, even more harmful than smoking.

- This may have been accurate for adults wishing to quit smoking; however, there are other methods available to help people stop using cigarettes.

Your paragraph would then continue your Refutation by explaining more reasons why the Counterargument is weak. This also serves to explain why your original Argument is strong. This is a good opportunity to prove to your readers that your original Argument is the most worthy, and to persuade them to agree with you.

Activity ~ Practice with Counterarguments, Concessions, and Refutations

A. Examine the following thesis statements with a partner. Is each one debatable?

B. Write your own Counterargument, Concession, and Refutation for each thesis statement.

Thesis Statements:

- Online classes are a better option than face-to-face classes for college students who have full-time jobs.

- Students who engage in cyberbullying should be expelled from school.

- Unvaccinated children pose risks to those around them.

- Governments should be allowed to regulate internet access within their countries.

Is this chapter:

…too easy, or you would like more detail? Read “ Further Your Understanding: Refutation and Rebuttal ” from Lumen’s Writing Skills Lab.

Note: links open in new tabs.

reasoning, logic

emotion, feeling, beliefs

moral character, credibility, trust, authority

goes against; believes the opposite of something

ENGLISH 087: Academic Advanced Writing Copyright © 2020 by Nancy Hutchison is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Please log in to save materials. Log in

- Concessions

- Counterarguments

- ESL Writing

The Argumentative Essay: The Language of Concession and Counterargument

Explanations and exercises about the use of counterarguments and concessions in argumentative essays.

The Argumentative Essay: The Language of Concession and Counterargument

We have already analyzed the structure of an argumentative essays (also known as a persuasive essay), and have read samples of this kind of essay. In this session we will review the purpose and structure of an argumentative essay, and will focus on practicing the grammar of sentences that present our argument while acknowledging that there is an opposing view point. In other words, we will focus on the grammar of concession and counterargument.

Purpose and structure of an argumentative essay

Take a few minutes to refresh your knowledge about the purpose and structure of argumentative / persuasive essays.

The Purpose of Persuasive Writing

The purpose of persuasion in writing is to convince, motivate, or move readers toward a certain point of view, or opinion. The act of trying to persuade automatically implies more than one opinion on the subject can be argued.

The idea of an argument often conjures up images of two people yelling and screaming in anger. In writing, however, an argument is very different. An argument is a reasoned opinion supported and explained by evidence. To argue in writing is to advance knowledge and ideas in a positive way. Written arguments often fail when they employ ranting rather than reasoning.

Most of us feel inclined to try to win the arguments we engage in. On some level, we all want to be right, and we want others to see the error of their ways. More times than not, however, arguments in which both sides try to win end up producing losers all around. The more productive approach is to persuade your audience to consider your opinion as a valid one, not simply the right one.

The Structure of a Persuasive Essay

The following five features make up the structure of a persuasive essay:

- Introduction and thesis

- Opposing and qualifying ideas

- Strong evidence in support of claim

- Style and tone of language

- A compelling conclusion

Creating an Introduction and a thesis

The persuasive essay begins with an engaging introduction that presents the general topic. The thesis typically appears somewhere in the introduction and states the writer’s point of view.

Avoid forming a thesis based on a negative claim. For example, “The hourly minimum wage is not high enough for the average worker to live on.” This is probably a true statement, but persuasive arguments should make a positive case. That is, the thesis statement should focus on how the hourly minimum wage is low or insufficient.

Acknowledging Opposing Ideas and Limits to Your Argument

Because an argument implies differing points of view on the subject, you must be sure to acknowledge those opposing ideas. Avoiding ideas that conflict with your own gives the reader the impression that you may be uncertain, fearful, or unaware of opposing ideas. Thus it is essential that you not only address counterarguments but also do so respectfully.

Try to address opposing arguments earlier rather than later in your essay. Rhetorically speaking, ordering your positive arguments last allows you to better address ideas that conflict with your own, so you can spend the rest of the essay countering those arguments. This way, you leave your reader thinking about your argument rather than someone else’s. You have the last word.

Acknowledging points of view different from your own also has the effect of fostering more credibility between you and the audience. They know from the outset that you are aware of opposing ideas and that you are not afraid to give them space.

It is also helpful to establish the limits of your argument and what you are trying to accomplish. In effect, you are conceding early on that your argument is not the ultimate authority on a given topic. Such humility can go a long way toward earning credibility and trust with an audience. Audience members will know from the beginning that you are a reasonable writer, and audience members will trust your argument as a result. For example, in the following concessionary statement, the writer advocates for stricter gun control laws, but she admits it will not solve all of our problems with crime:

Although tougher gun control laws are a powerful first step in decreasing violence in our streets, such legislation alone cannot end these problems since guns are not the only problem we face.

Such a concession will be welcome by those who might disagree with this writer’s argument in the first place. To effectively persuade their readers, writers need to be modest in their goals and humble in their approach to get readers to listen to the ideas.

Text above adapted from: Writing for Success – Open Textbook (umn.edu) Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Argument, Concession/Acknowledgment and Refutation

We have already seen that as a writer of an argumentative essay, you do not just want to present your arguments for or against a certain issue. You need to convince or persuade your readers that your opinion is the valid one. You convince readers by presenting your points of view, by presenting points of view that oppose yours, and by showing why the points of view different from yours are not as valid as yours. These three elements of an argumentative essay are known as argument (your point of view), concession/acknowledgement/counterargument (admission that there is an opposing point of view to yours) and refutation (showing why the counterargument is not valid). Acknowledging points of view different from yours and refuting them makes your own argument stronger. It shows that you have thought about all the sides of the issue instead of thinking only about your own views.

Identifying argument, counterargument, concession and refutation

We will now look at sentences from paragraphs which are part of an argumentative essay and identify these parts. Read the four sentences in each group and decide if each sentence is the argument, the counterargument, the acknowledgement / concession or the refutation. Circle your choice.

Schools need to replace paper books with e-books.

argument counterargument acknowledgement refutation

Others believe students will get bad eyesight if they read computer screens instead of paper books.

There is some truth to this statement.

However, e-books are much cheaper than paper books.

The best way to learn a foreign language is to visit a foreign country.

Some think watching movies in the foreign language is the best way to learn a language.

Even though people will learn some of the foreign language this way,

it cannot be better than actually living in the country and speaking with the people every day.

Exercise above adapted from: More Practice Recognizing Counterarguments, Acknowledgements, and Refutations. Clyde Hindman. Canvas Commons. Public domain.

More Practice Recognizing Counterarguments, Acknowledgements, and Refutations | Canvas Commons (instructure.com)

Sentence structure: Argument and Concession

Read the following sentences about the issue of cell phone use in college classrooms. Notice the connectors used between the independent and the dependent clauses.

Although cell phones are convenient, they isolate people.

dependent clause independent clause

Cell phones isolate people, even though they are convenient.

independent clause dependent clause

In the sentences above, the argument is “cell phones isolate people”. The counterargument is “cell phones are convenient” and the acknowledgment/concession is expressed by the use of although / even though to make the concession of the opposing argument.

In addition, and most importantly, notice the following:

Which clause contains the writer’s argument? Which clause contains the concession?

The writer’s position is contained in the independent clause and the concession is contained in the dependent clause. This helps the writer to highlight their argument by putting it in the clause that stands on its own and leaving the dependent clause for the concession.

Notice that it doesn’t matter if the independent clause is at the beginning or at the end of the sentence. In both cases, the argument is “cell phones isolate people.”

Notice the difference between these two sentences:

Cell phones are convenient, even though they isolate people.

independent clause dependent clause

Cell phones isolate people, even though they are convenient.

independent clause dependent clause

This pair of sentences shows how the structure of the sentence reflects the point of view of the writer. The argument in the first sentence is that cell phones are convenient. The writer feels this is the important aspect, and thus places it in the independent clause. In the dependent clause, the writer concedes that cell phones isolate people. In contrast, in the second sentence the argument is that cell phones isolate people. The writer feels this is the important aspect and therefore puts this idea in the independent clause. The writer of this sentence concedes that cell phones are convenient, and this concession appears in the dependent clause.

Read the following pairs of sentences and say which sentence in the pair has a positive attitude towards technology in our lives.

A

- Although technology has brought unexpected problems to society, it has become an instrument of progress.

- Technology has brought unexpected problems to society, even though it has become an instrument of progress.

B

- Technology is an instrument of social change, even though there are affordability issues.

- There are affordability issues with technology, even though it is it is an instrument of social change.

Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

Maria Antonini de Pino – Evergreen Valley College, San Jose, California, USA

LIST OF SOURCES (in order of appearance)

- Text adapted from: Writing for Success – Open Textbook (umn.edu)

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International

- Exercise adapted from: More Practice Recognizing Counterarguments, Acknowledgements, and Refutations. Clyde Hindman. Canvas Commons. Public domain.

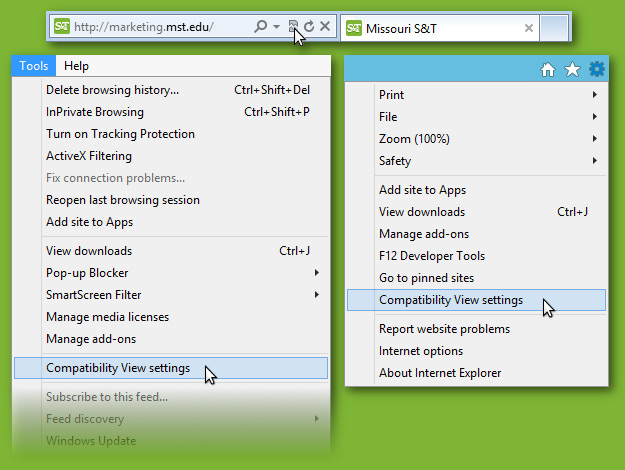

Your version of Internet Explorer is either running in "Compatibility View" or is too outdated to display this site. If you believe your version of Internet Explorer is up to date, please remove this site from Compatibility View by opening Tools > Compatibility View settings (IE11) or clicking the broken page icon in your address bar (IE9, IE10)

Missouri S&T Missouri S&T

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty and Staff

- writingcenter.mst.edu

- Online Resources

- Writing Guides

- Counter Arguments

Writing and Communication Center

- 314 Curtis Laws Wilson Library, 400 W 14th St Rolla, MO 65409 United States

- (573) 341-4436

- [email protected]

Counter Argument

One way to strengthen your argument and demonstrate a comprehensive understanding of the issue you are discussing is to anticipate and address counter arguments, or objections. By considering opposing views, you show that you have thought things through, and you dispose of some of the reasons your audience might have for not accepting your argument. Ask yourself what someone who disagrees with you might say in response to each of the points you’ve made or about your position as a whole.

If you can’t immediately imagine another position, here are some strategies to try:

- Do some research. It may seem to you that no one could possibly disagree with the position you are taking, but someone probably has. Look around to see what stances people have and do take on the subject or argument you plan to make, so that you know what environment you are addressing.

- Talk with a friend or with your instructor. Another person may be able to play devil’s advocate and suggest counter arguments that haven’t occurred to you.

- Consider each of your supporting points individually. Even if you find it difficult to see why anyone would disagree with your central argument, you may be able to imagine more easily how someone could disagree with the individual parts of your argument. Then you can see which of these counter arguments are most worth considering. For example, if you argued “Cats make the best pets. This is because they are clean and independent,” you might imagine someone saying “Cats do not make the best pets. They are dirty and demanding.”

Once you have considered potential counter arguments, decide how you might respond to them: Will you concede that your opponent has a point but explain why your audience should nonetheless accept your argument? Or will you reject the counterargument and explain why it is mistaken? Either way, you will want to leave your reader with a sense that your argument is stronger than opposing arguments.

Two strategies are available to incorporate counter arguments into your essay:

Refutation:

Refutation seeks to disprove opposing arguments by pointing out their weaknesses. This approach is generally most effective if it is not hostile or sarcastic; with methodical, matter-of-fact language, identify the logical, theoretical, or factual flaws of the opposition.

For example, in an essay supporting the reintroduction of wolves into western farmlands, a writer might refute opponents by challenging the logic of their assumptions:

Although some farmers have expressed concern that wolves might pose a threat to the safety of sheep, cattle, or even small children, their fears are unfounded. Wolves fear humans even more than humans fear wolves and will trespass onto developed farmland only if desperate for food. The uninhabited wilderness that will become the wolves’ new home has such an abundance of food that there is virtually no chance that these shy animals will stray anywhere near humans.

Here, the writer acknowledges the opposing view (wolves will endanger livestock and children) and refutes it (the wolves will never be hungry enough to do so).

Accommodation:

Accommodation acknowledges the validity of the opposing view, but argues that other considerations outweigh it. In other words, this strategy turns the tables by agreeing (to some extent) with the opposition.

For example, the writer arguing for the reintroduction of wolves might accommodate the opposing view by writing:

Critics of the program have argued that reintroducing wolves is far too expensive a project to be considered seriously at this time. Although the reintroduction program is costly, it will only become more costly the longer it is put on hold. Furthermore, wolves will help control the population of pest animals in the area, saving farmers money on extermination costs. Finally, the preservation of an endangered species is worth far more to the environment and the ecological movement than the money that taxpayers would save if this wolf relocation initiative were to be abandoned.

This writer acknowledges the opposing position (the program is too expensive), agrees (yes, it is expensive), and then argues that despite the expense the program is worthwhile.

Some Final Hints

Don’t play dirty. When you summarize opposing arguments, be charitable. Present each argument fairly and objectively, rather than trying to make it look foolish. You want to convince your readers that you have carefully considered all sides of the issues and that you are not simply attacking or caricaturing your opponents.

Sometimes less is more. It is usually better to consider one or two serious counter arguments in some depth, rather than to address every counterargument.

Keep an open mind. Be sure that your reply is consistent with your original argument. Careful consideration of counter arguments can complicate or change your perspective on an issue. There’s nothing wrong with adopting a different perspective or changing your mind, but if you do, be sure to revise your thesis accordingly.

30 Refutation Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

Refutation refers to the act of proving a statement or theory wrong through the use of logical reasoning and evidence.

Some strategies for refutation, which we may use in an argumentative essay, speech, or debate, include:

- Reductio ad Absurdum : Taking an argument to its logical conclusion to demonstrate its absurdity.

- Counterexamples : Presenting counterexamples , which are practical and real-life examples that contradict the opponent’s claims.

- Identifying Logical Fallacies : Highlighting instances in which the opponent’s claims don’t follow logical reasoning.

- Highlighting Omissions: Demonstrating that the opponent failed to discuss or consider facts that dispute their claims.

I recommend to all my students that they refute possible counterclaims and contradicting perspectives in their argumentative essays in order to establish an authoritative position, demonstrate awareness of a broad range of perspectives, and add depth to your arguments.

Below is a range of methods of refutation.

Refutation Examples

1. analogical disproof.

This method involves refuting an argument by drawing a parallel to a situation that’s logically similar but absurd or clearly incorrect. Used properly, it can effectively puncture an opponent’s argument, showing that the same logic could lead to preposterous conclusions.

Example: “All birds fly. Penguins are birds, so they should fly.” The analogical disproof might be: “Not all office workers use computers. You’re an office worker, so should you not use a computer?”

2. Test of Consistency

This refutation method tests whether an argument stands consistent under different circumstances or scenarios. If an argument contains contradictions or doesn’t hold true in various contexts, it falls under inconsistency.

Example: Someone posits, “A person should always lend money to friends.” A consistency test might involve asking, “Should a person still lend money if they know their friend will spend it irresponsibly?”

See More: Consistency Examples

3. Rebuttal by Cause and Effect

This approach involves contesting an argument by disputing the assumed relationship between cause and effect. Here, you challenge the validity of the cause, the effect, or the linkage between the two.

Example: To refute, “Violent video games cause aggressive behavior in players,” you might present studies showing no significant increase in aggression among players of violent video games. This disrupts the asserted cause-effect relationship.

See More: Cause and Effect Examples

4. Prioritization of Evidence

This method questions the quality, reliability, or relevance of the evidence presented in an argument. You might challenge evidence’s weight, context, source, or legitimacy to weaken the opponent’s stance.

Example: Against the claim, “Spicy food aids in weight loss because it boosts metabolism,” you could highlight that the studies underpinning that claim are less reliable than studies demonstrating that exercise boosts weight loss.

5. Challenge the Relevance

Challenging the relevance involves disputing how pertinent or directly related the opponent’s points are to the argument at hand. Irrelevant points detract from the main argument and don’t strengthen the position they are intended to support.

Example: If someone argues, “Technology improves quality of life because smartphones have advanced cameras,” you might challenge the relevance by questioning how advanced cameras light to better quality of life.

See More: Relevance Examples

6. Statistical Refutation

Statistical refutation seeks to invalidate an argument by questioning the statistical evidence used. This might involve critiquing how data were collected, interpreted, or applied.

Example: If a study claims, “80% of people feel healthier when they eat chocolate daily,” you could challenge the data by asking who was surveyed and how the question was asked.

7. Appeal to Common Sense

An appeal to common sense challenges a claim by invoking widely accepted truths or knowledge. This strategy can debunk arguments that defy everyday observations or popular wisdom.

Example: If someone says, “to prevent climate change we need to shut down all coal-fired powerplants immediately,” you could refute it by appealing to the common sense notion that shutting them all down right now would cause the entire economy to collapse overnight.

See More: Examples of Common Sense

8. Pointing Out Oversimplification

This method involves highlighting how an opponent’s argument oversimplifies a complex issue. It exposes a lack of depth or nuance in their argument, undermining its credibility.

Example: A statement like “More jobs equals less poverty” could be refuted by pointing out the oversimplification in neglecting factors like cost of living and wage levels.

See More: Oversimplification Examples

9. Dismantling a False Dilemma

A false dilemma presents a situation as having only two possible outcomes or solutions. Dismantling a false dilemma involves introducing alternatives or proving that the two proposed options aren’t the only ones.

Example: Against the assertion, “Either we preserve our traditions, or we embrace progress,” you could challenge that we can preserve traditions and also move forward.

See More: False Dilemma Examples

10. Rebuttal through Definition

Rebuttal through definition involves challenging an argument by critiquing the definitions of the concepts, phenomena, or terms used. Here, you question the way an opponent has defined key elements of their argument.

Example: If an argument purports, “Happiness is having a lot of money,” you might dispute that definition by referencing different measures of happiness that don’t involve wealth, such as relationships or personal growth.

See More: Rebuttal Examples

11. Rebuttal by Precedence

This method employs historical or present precedents to debunk an argument. By illustrating similar situations where the opponent’s proposition didn’t hold true or feasible decisions were made contrary to the claim, the argument can be refuted.

Example: If faced with the claim, “No democracy can survive without a two-party system,” you could counter by citing examples of thriving democracies around the world with more than two significant parties.

12. Challenge the Representativeness

Challenging the representativeness entails scrutinizing whether an argument’s supporting evidence adequately represents the whole. It rejects sweeping generalizations or conclusions based on limited data.

Example: Should someone argue, “Most students dislike school, as proven by a survey from my class,” you could counter by questioning whether your class is representative of all students around the country.

13. Rebuttal through Syllogism

Rebuttal through syllogism uses the opponent’s premises to arrive at a different conclusion. If, through logical reasoning, the proposed conclusion does not necessarily follow the premises given, the argument can be effectively refuted.

Example: To the statement, “All apples are fruit. All fruit grow on trees. Therefore, all trees grow apples,” a syllogistic rebuttal might state, “While all apples grow on trees, not all trees grow apples.”

14. Pointing Out Non-Sequitur

Pointing out non-sequitur involves highlighting that an argument’s conclusion does not logically follow from its premises. Non-sequiturs often involve leaps in logic or unwarranted assumptions.

Example: In response to the claim, “He’s a great musician, so he’ll be a fantastic concert organizer,” one might point out the non-sequitur by reminding that a musical talent does not equate managerial skills.

15. Rebuttal by Exception

Rebuttal by exception operates by finding exceptions to the generalization made in an argument. By highlighting exceptions that contradict the claim, the argument’s validity is diminished.

Example: If someone argues, “All politicians are corrupt,” you could refute it by highlighting politicians known for their integrity and conviction.

16. Evidence-Based Counterargument

An evidence-based counterargument refutes a claim by presenting strong, credible, and relevant evidence that contradicts the original argument. This method is most effective when the counter-evidence directly disputes the original claim or its supporting facts.

Example: If a person claims, “Milk should be avoided because it’s unhealthy,” an evidence-based counterargument might bring up numerous scientific studies that indicate the nutritional benefits of milk.

See More: Counterargument Examples

17. Logical Analysis

A logical analysis focuses on the internal coherence and logical validity of an argument. By identifying logical fallacies or missteps in reasoning, you can refute a claim by showing how it fails to adhere to the principles of logic.

Example: A statement like “Every time I eat pizza, it rains, so pizza causes rain” can be refuted through logical analysis by highlighting the improper correlation being made.

18. Reductio ad Absurdum

The Reductio ad Absurdum technique demonstrates the absurdity of an argument by pushing it to its logical extreme, where it produces an absurd or preposterous conclusion. This method effectively challenges the premises or logic of the original claim.

Example: If someone argues, “We should never take any risks,” a Reductio ad Absurdum response might be: “By that logic, no one should ever leave their house because stepping outside is inherently risky.”

19. Counterexamples

Counterexamples are specific instances or examples that contradict a general claim or principle. By showing that the contrary is possible or proven, counterexamples can significantly weaken an argument.

Example: If someone claims, “All athletes are team players,” a compelling counterexample might highlight known instances of successful athletes who are infamous for their individualistic nature.

20. Question the Source

Questioning the source involves casting doubt on the credibility, relevance, or authority of the source supporting an argument. If the source is untrustworthy, the claim it supports is also brought into question.

Example: If the argument is “Vitamin C prevents cold because a juice-ad claims so,” you may question the objectivity of a source that may profit from selling more juice.

See More: Best Sources to Cite in Essays

21. Alternative Explanation

Providing an alternative explanation challenges an argument by proposing a different interpretation or understanding of the topic. This method allows you to dispute a claim by suggesting that another explanation is more plausible, relevant, or comprehensive.

Example: An argument might be, “Increased police presence reduces crime.” An alternative explanation could suggest that a more likely cause of reduced crime is improved social support systems and opportunities.

22. Challenge Assumptions

Challenging assumptions requires questioning the premise or basis of an argument. If the argument is built on flawed or questionable assumptions, exposing these can undermine the argument.

Example: When confronted with the argument “Marriage is essential for happiness,” one might challenge the underlying assumption that happiness necessarily requires marriage, citing examples of fulfilled single individuals.

See More: Assumptions Examples

23. Ethical or Moral Challenge

This type of refutation questions an argument on ethical or moral grounds. If the suggested actions or results of an argument lead to morally questionable outcomes, it can be a valid point of refutation.

Example: If someone says, “We should eliminate all pests for a more comfortable life,” you might counter it by pointing out the ethical concerns regarding biodiversity and the broader ecosystem’s health.

24. Using Comparison to Demonstrate Flawed Arguments

Comparisons involve using parallel scenarios, situations, or cases to refute an argument. By emphasizing the similarities or differences, you can question the validity of the argument.

Example: If the claim is “More expensive colleges provide a better education,” you could compare specific high-quality, affordable colleges with premium, yet underperforming ones to refute this argument.

25. Highlight Omissions

Highlighting omissions refers to pointing out relevant facts, information, or arguments that the opponent has left out of their claim. By illuminating these gaps, you can challenge the reliability or completeness of their argument.

Example: If someone argues, “He must be unsuccessful, he never went to college,” you can point out the omission of successful individuals who did not follow the traditional academic path.

26. Reframe the Debate

Reframing the debate involves changing the perspective or the center of the argument. It allows you to shift focus to a different, often overlooked aspect of the discussion, thus challenging the premises or relevance of the original argument.

Example: When faced with the claim, “Academic achievements determine success in life,” you can reframe the debate by suggesting that emotional intelligence, resilience, or interpersonal skills could be more significant indicators of life success.

27. Historical or Precedent-Based Refutation

This method utilizes historical events or established precedents to refute a claim. By referencing cases that contradict the opponent’s assertion, you can question its validity or applicability.

Example: In response to the claim, “Communism leads to societal chaos,” you could point out Cuba, who maintains law and order, to contradict the argument.

28. Practical Implications

Refuting via practical implications involves evaluating the real-world implications or consequences of an argument. This can be used to highlight unforeseen or negative implications that counter the argument’s intent.

Example: If someone suggests, “Cutting all funding for arts can help resolve government budget issues,” you could mention the practical implication that this could result in lost cultural heritage and inspire public backlash.

See Also: Implications Examples

29. Question Motives or Bias

This method of refutation questions whether the argument might be influenced by the speaker’s motives or biases. If the speaker seems to benefit from their claim or appears biased, their argument can be viewed suspiciously.

Example: If a smartphone developer declares, “My company’s phones are unbeatable,” question their bias as they stand to gain from promoting their company’s products.

See Also: Types of Bias

30. Seek Expert Testimony

Seeking expert testimony involves drawing on the knowledge or expertise of recognized authorities on the topic at hand. If expert opinion conflicts with the original statement, the credibility of the argument is undermined.

Example: In an argument about climate change, expert testimony from credible climate scientists refuting a claim of disbelievers can strengthen your refutation.

Understanding refutation will aid in developing stronger arguments and more impactful communication. I recommend to my students that they always refute the strongest claims of their opposition in order to more authoritatively prosecute their own perspective. But remember, in refuting opposing views, you need to be very careful not to fall into poor quality arguments, logical fallacies, or arguments that might otherwise damage your own legitimacy and reputation. Refutation must be clear, systematic, and well-thought-out in order for it to be effective.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 15 Green Flags in a Relationship

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 15 Signs you're Burnt Out, Not Lazy

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 15 Toxic Things Parents Say to their Children

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Counterarguments

A counterargument involves acknowledging standpoints that go against your argument and then re-affirming your argument. This is typically done by stating the opposing side’s argument, and then ultimately presenting your argument as the most logical solution. The counterargument is a standard academic move that is used in argumentative essays because it shows the reader that you are capable of understanding and respecting multiple sides of an argument.

Counterargument in two steps

Respectfully acknowledge evidence or standpoints that differ from your argument.

Refute the stance of opposing arguments, typically utilizing words like “although” or “however.”

In the refutation, you want to show the reader why your position is more correct than the opposing idea.

Where to put a counterargument

Can be placed within the introductory paragraph to create a contrast for the thesis statement.

May consist of a whole paragraph that acknowledges the opposing view and then refutes it.

- Can be one sentence acknowledgements of other opinions followed by a refutation.

Why use a counterargument?

Some students worry that using a counterargument will take away from their overall argument, but a counterargument may make an essay more persuasive because it shows that the writer has considered multiple sides of the issue. Barnet and Bedau (2005) propose that critical thinking is enhanced through imagining both sides of an argument. Ultimately, an argument is strengthened through a counterargument.

Examples of the counterargument structure

- Argument against smoking on campus: Admittedly, many students would like to smoke on campus. Some people may rightly argue that if smoking on campus is not illegal, then it should be permitted; however, second-hand smoke may cause harm to those who have health issues like asthma, possibly putting them at risk.

- Argument against animal testing: Some people argue that using animals as test subjects for health products is justifiable. To be fair, animal testing has been used in the past to aid the development of several vaccines, such as small pox and rabies. However, animal testing for beauty products causes unneeded pain to animals. There are alternatives to animal testing. Instead of using animals, it is possible to use human volunteers. Additionally, Carl Westmoreland (2006) suggests that alternative methods to animal research are being developed; for example, researchers are able to use skin constructed from cells to test cosmetics. If alternatives to animal testing exist, then the practice causes unnecessary animal suffering and should not be used.

Harvey, G. (1999). Counterargument. Retrieved from writingcenter.fas.harvard.edu/pages/counter- argument

Westmoreland, C. (2006; 2007). “Alternative Tests and the 7th Amendment to the Cosmetics Directive.” Hester, R. E., & Harrison, R. M. (Ed.) Alternatives to animal testing (1st Ed.). Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry.

Barnet, S., Bedau, H. (Eds.). (2006). Critical thinking, reading, and writing . Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Contributor: Nathan Lachner

Consider the following thesis for a short paper that analyzes different approaches to stopping climate change:

Climate activism that focuses on personal actions such as recycling obscures the need for systemic change that will be required to slow carbon emissions.

The author of this thesis is promising to make the case that personal actions not only will not solve the climate problem but may actually make the problem more difficult to solve. In order to make a convincing argument, the author will need to consider how thoughtful people might disagree with this claim. In this case, the author might anticipate the following counterarguments:

- By encouraging personal actions, climate activists may raise awareness of the problem and encourage people to support larger systemic change.

- Personal actions on a global level would actually make a difference.

- Personal actions may not make a difference, but they will not obscure the need for systemic solutions.

- Personal actions cannot be put into one category and must be differentiated.

In order to make a convincing argument, the author of this essay may need to address these potential counterarguments. But you don’t need to address every possible counterargument. Rather, you should engage counterarguments when doing so allows you to strengthen your own argument by explaining how it holds up in relation to other arguments.

How to address counterarguments

Once you have considered the potential counterarguments, you will need to figure out how to address them in your essay. In general, to address a counterargument, you’ll need to take the following steps.

- State the counterargument and explain why a reasonable reader could raise that counterargument.

- Counter the counterargument. How you grapple with a counterargument will depend on what you think it means for your argument. You may explain why your argument is still convincing, even in light of this other position. You may point to a flaw in the counterargument. You may concede that the counterargument gets something right but then explain why it does not undermine your argument. You may explain why the counterargument is not relevant. You may refine your own argument in response to the counterargument.

- Consider the language you are using to address the counterargument. Words like but or however signal to the reader that you are refuting the counterargument. Words like nevertheless or still signal to the reader that your argument is not diminished by the counterargument.

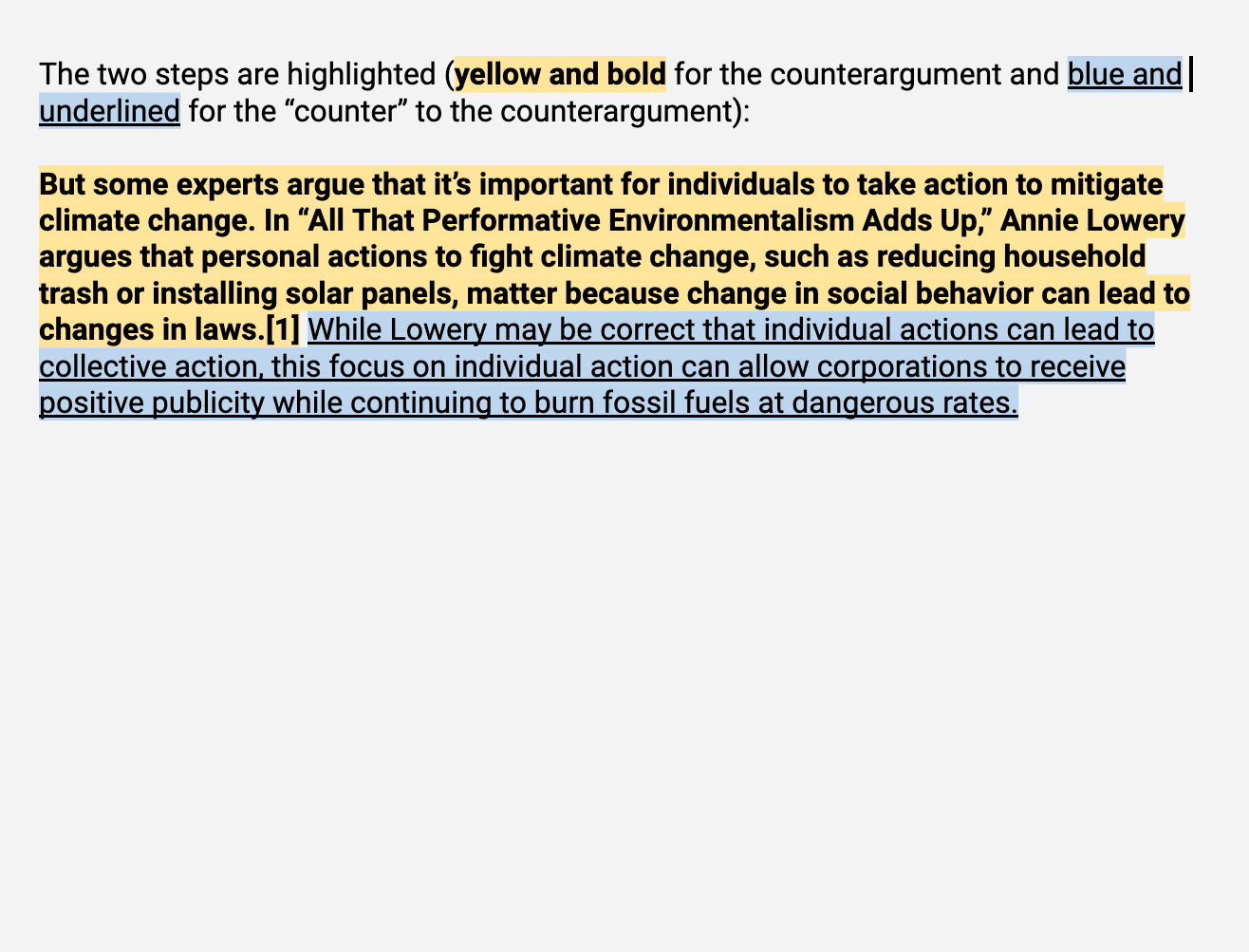

Here’s an example of a paragraph in which a counterargument is raised and addressed.

Image version

The two steps are marked with counterargument and “counter” to the counterargument: COUNTERARGUMENT/ But some experts argue that it’s important for individuals to take action to mitigate climate change. In “All That Performative Environmentalism Adds Up,” Annie Lowery argues that personal actions to fight climate change, such as reducing household trash or installing solar panels, matter because change in social behavior can lead to changes in laws. [1]

COUNTER TO THE COUNTERARGUMENT/ While Lowery may be correct that individual actions can lead to collective action, this focus on individual action can allow corporations to receive positive publicity while continuing to burn fossil fuels at dangerous rates.

Where to address counterarguments

There is no one right place for a counterargument—where you raise a particular counterargument will depend on how it fits in with the rest of your argument. The most common spots are the following:

- Before your conclusion This is a common and effective spot for a counterargument because it’s a chance to address anything that you think a reader might still be concerned about after you’ve made your main argument. Don’t put a counterargument in your conclusion, however. At that point, you won’t have the space to address it, and readers may come away confused—or less convinced by your argument.

- Before your thesis Often, your thesis will actually be a counterargument to someone else’s argument. In other words, you will be making your argument because someone else has made an argument that you disagree with. In those cases, you may want to offer that counterargument before you state your thesis to show your readers what’s at stake—someone else has made an unconvincing argument, and you are now going to make a better one.

- After your introduction In some cases, you may want to respond to a counterargument early in your essay, before you get too far into your argument. This is a good option when you think readers may need to understand why the counterargument is not as strong as your argument before you can even launch your own ideas. You might do this in the paragraph right after your thesis.

- Anywhere that makes sense As you draft an essay, you should always keep your readers in mind and think about where a thoughtful reader might disagree with you or raise an objection to an assertion or interpretation of evidence that you are offering. In those spots, you can introduce that potential objection and explain why it does not change your argument. If you think it does affect your argument, you can acknowledge that and explain why your argument is still strong.

[1] Annie Lowery, “All that Performative Environmentalism Adds Up.” The Atlantic . August 31, 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/08/your-tote-bag-can-mak…

- picture_as_pdf Counterargument

Encyclopedia

Writing with artificial intelligence, counterarguments – rebuttal – refutation.

- © 2023 by Roberto León - Georgia College & State University

Ignoring what your target audience thinks and feels about your argument isn't a recipe for success. Instead, engage in audience analysis : ask yourself, "How is your target audience likely to respond to your propositions? What counterarguments -- arguments about your argument -- will your target audience likely raise before considering your propositions?"

Table of Contents

Counterargument Definition

C ounterargument refers to an argument given in response to another argument that takes an alternative approach to the issue at hand.

C ounterargument may also be known as rebuttal or refutation .

Related Concepts

Audience Awareness ; Authority (in Speech and Writing) ; Critical Literacy ; Ethos ; Openness ; Researching Your Audience

Guide to Counterarguments in Writing Studies

Counterarguments are a topic of study in Writing Studies as

- Rhetors engage in rhetorical reasoning : They analyze the rebuttals their target audiences may have to their claims , interpretations , propositions, and proposals

- Rhetors may develop counterarguments by questioning a rhetor’s backing , data , qualifiers, and/or warrants

- Rhetors begin arguments with sincere summaries of counterarguments

- a strategy of Organization .

Learning about the placement of counterarguments in Toulmin Argument , Arisotelian Argument , and Rogerian Argument will help you understand when you need to introduce counterarguments and how thoroughly you need to address them.

Why Do Counterarguments Matter?

If your goal is clarity and persuasion, you cannot ignore what your target audience thinks, feels, and does about the argument. To communicate successfully with audiences, rhetors need to engage in audience analysis : they need to understand the arguments against their argument that the audience may hold.

Imagine that you are scrolling through your social media feed when you see a post from an old friend. As you read, you immediately feel that your friend’s post doesn’t make sense. “They can’t possibly believe that!” you tell yourself. You quickly reply “I’m not sure I agree. Why do you believe that?” Your friend then posts a link to an article and tells you to see for yourself.

There are many ways to analyze your friend’s social media post or the professor’s article your friend shared. You might, for example, evaluate the professor’s article by using the CRAAP Test or by conducting a rhetorical analysis of their aims and ethos . After engaging in these prewriting heuristics to get a better sense of what your friend knows and feels about the topic at hand, you may feel more prepared to respond to their arguments and also sense how they might react to your post.

Toulmin Counterarguments

There’s more than one way to counter an argument.

In Toulmin Argument , a counterargument can be made against the writer’s claim by questioning their backing , data , qualifiers, and/or warrants . For example, let’s say we wrote the following argument:

“Social media is bad for you (claim) because it always (qualifier) promotes an unrealistic standard of beauty (backing). In this article, researchers found that most images were photoshopped (data). Standards should be realistic; if they are not, those standards are bad (warrant).”

Besides noting we might have a series of logical fallacies here, counterarguments and dissociations can be made against each of these parts:

- Against the qualifier: Social media does not always promote unrealistic standards.