- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.4: Research Proposals

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 128984

Learning Objectives

- Perform biodiversity research through making and translating your observations of the natural world into research questions, hypotheses, and experimental design that are grounded in scientific literature.

- Communicate the research process to your peers in a clear, effective, and engaging manner.

Written Proposal

Writing about research is a primary method scientists use to communicate their work. Thus, this course will involve developing a written research proposal. We will use several drafts to refine the research proposal. The first draft can utilize the template available in Appendix 6. Subsequent drafts should become more refined and start to take the format of a scientific paper. The proposal should include an introductory section providing background on the topic of interest, drawing from several primary research articles. This section also develops the argument for why the research question is worth studying. The research question and hypothesis should also be included in the introduction.

The second section should include the proposed methodology. Describe how the hypothesis will be tested. It should outline the experiments and what will be needed to perform them. Ideas can be supported by referring to previously published research. The third section will address anticipated results. Consider the expected findings and the implications of those findings for the original research question and hypothesis. Consider what it would mean if the results turned out a different way. Finally, be sure to include both in-text citations and a full reference list at the end. The proposal should have good narrative flow and be proofread for proper spelling and grammar. See the rubric in the Appendix 3 for evaluation guidelines.

Oral Presentation

Scientists also frequently share their research findings via presentations, such as at meetings with other scientists. Developing an oral presentation of the research proposal provides an opportunity to practice communicating science to our peers. The presentation should be ~10 minutes and delivered via a slideshow. The presentation should include the same content as the written portion, but the distinction here the audience will be engaged in a different way. The best presentations tell a good story, so think about how to translate the proposal into a story – typically start with background information so the audience members have some understanding of the context. Then use the background information strategically to build up to the identified research gap and the corresponding research question. The question then leads naturally into the hypothesis or hypotheses to be tested. The final part of the presentation will be the experimental plan – how will the hypothesis be tested? Try to envision all possible outcomes from the experiment and how that will support or refute the hypothesis and inform on the interpretation of the results.

There will be opportunities for questions from peers at the end. It is important to try to ask questions at the end of presentations in order to practice giving this kind of feedback. This is a very common way in which scientists provide feedback to each other on their work. Attending departmental seminars or conferences will enable witnessing this first hand. See the rubric in the Appendix 3 for evaluation guidelines.

Proposal Workshop I

Proposing research ideas is a key element of working in the biodiversity science field. Thus this first workshop will be focused on sharing and expanding upon initial ideas for a research proposal. It will take a lab meeting format with a round table discussion where each student has the opportunity to share their research proposal ideas. Peers will then ask follow-up questions to help support idea development. Incidentally, this also serves as an opportunity to practice communicating science to peers. It takes practice to clearly articulate ideas. Following the workshop, begin exploring some literature related to the topic of interest and start putting ideas down on paper – they will not be polished yet, but it will help to develop the initial draft of the research proposal. See the Appendix 6 for a proposal first draft template.

Proposal Workshop II

This workshop will continue to develop the research question, hypothesis, and experimental design. We will discuss developing ideas in pairs with both the course instructor and classmates. We will work to develop ideas into excellent proposal material by digging into the following questions.

Research Question

- What is your research question?

- Is your question clearly stated and focused? If not, how might you tailor it?

- Why are you interested in this question? What makes you curious about it? What have you learned from previous studies that lead you to want to ask this question?

Hypotheses/predictions

- What are your hypotheses/predictions?

- Are they stated clearly? If not, what needs to be adjusted?

- Are they aligned with the question you are asking?

- Why are you interested in this hypothesis?

Experimental Plan

- What is your experimental plan?

- Does the design fit with your hypothesis?

- Are there things that still need to be considered? If so, what are they?

Proposal Workshop III

This workshop is an opportunity to polish. Use this time to solicit final feedback from peers, test out design ideas for the final presentation, or practice delivering the presentation in front of an audience.

Excellent opening paragraph stating why is the research important and leading to the research goals

Clear and concise presentation of research aims \(questions\)

Research plan is well \ detailed starting from third paragraph.

Pronoun problem: who is the "w\ e"? Earlier, "I" is very clear, but this "we" lacks a clear antecedent.

Writing tip: good use of "signa\ l" words \("first," "second"\) to organize information and highlight key points.

Contributors: P. Pazos, Searle Center for Teaching Excellence and P. Hirsch, The Writing Program, [email protected]

Posted: 2008

TITLE: The Mitochondrial Stress Response and the Communication of Stress Responses Between Subcellular Compart\ ments

Compelling presentation of preparation from courses and prior lab experience.

Very detailed presentation of techni\ ques learned that are relevant to the project

Writing tip: "data" is a p\ lural word. Say, "The data suggest. . . " and "they [meaning the data] indicate."

Overall comments:

Good quality proposal overall. The author clearly explains the aims a\ nd methods to carry out those aims.

Research question: Analysis of mitochondria's unfolding protein response and its crosstalk with other folding envir\ onments in the cell.

Compelling presentation of prior experience in courses and labs. Could include specific techniques learned.

Good use of citations and references

Suggestions:

Should add headings to make it more readable and add some structure.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

Published on October 12, 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on November 21, 2023.

A research proposal describes what you will investigate, why it’s important, and how you will conduct your research.

The format of a research proposal varies between fields, but most proposals will contain at least these elements:

Introduction

Literature review.

- Research design

Reference list

While the sections may vary, the overall objective is always the same. A research proposal serves as a blueprint and guide for your research plan, helping you get organized and feel confident in the path forward you choose to take.

Table of contents

Research proposal purpose, research proposal examples, research design and methods, contribution to knowledge, research schedule, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research proposals.

Academics often have to write research proposals to get funding for their projects. As a student, you might have to write a research proposal as part of a grad school application , or prior to starting your thesis or dissertation .

In addition to helping you figure out what your research can look like, a proposal can also serve to demonstrate why your project is worth pursuing to a funder, educational institution, or supervisor.

Research proposal length

The length of a research proposal can vary quite a bit. A bachelor’s or master’s thesis proposal can be just a few pages, while proposals for PhD dissertations or research funding are usually much longer and more detailed. Your supervisor can help you determine the best length for your work.

One trick to get started is to think of your proposal’s structure as a shorter version of your thesis or dissertation , only without the results , conclusion and discussion sections.

Download our research proposal template

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing a research proposal can be quite challenging, but a good starting point could be to look at some examples. We’ve included a few for you below.

- Example research proposal #1: “A Conceptual Framework for Scheduling Constraint Management”

- Example research proposal #2: “Medical Students as Mediators of Change in Tobacco Use”

Like your dissertation or thesis, the proposal will usually have a title page that includes:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- Your institution and department

The first part of your proposal is the initial pitch for your project. Make sure it succinctly explains what you want to do and why.

Your introduction should:

- Introduce your topic

- Give necessary background and context

- Outline your problem statement and research questions

To guide your introduction , include information about:

- Who could have an interest in the topic (e.g., scientists, policymakers)

- How much is already known about the topic

- What is missing from this current knowledge

- What new insights your research will contribute

- Why you believe this research is worth doing

As you get started, it’s important to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the most important research on your topic. A strong literature review shows your reader that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge or theory. It also shows that you’re not simply repeating what other people have already done or said, but rather using existing research as a jumping-off point for your own.

In this section, share exactly how your project will contribute to ongoing conversations in the field by:

- Comparing and contrasting the main theories, methods, and debates

- Examining the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches

- Explaining how will you build on, challenge, or synthesize prior scholarship

Following the literature review, restate your main objectives . This brings the focus back to your own project. Next, your research design or methodology section will describe your overall approach, and the practical steps you will take to answer your research questions.

To finish your proposal on a strong note, explore the potential implications of your research for your field. Emphasize again what you aim to contribute and why it matters.

For example, your results might have implications for:

- Improving best practices

- Informing policymaking decisions

- Strengthening a theory or model

- Challenging popular or scientific beliefs

- Creating a basis for future research

Last but not least, your research proposal must include correct citations for every source you have used, compiled in a reference list . To create citations quickly and easily, you can use our free APA citation generator .

Some institutions or funders require a detailed timeline of the project, asking you to forecast what you will do at each stage and how long it may take. While not always required, be sure to check the requirements of your project.

Here’s an example schedule to help you get started. You can also download a template at the button below.

Download our research schedule template

If you are applying for research funding, chances are you will have to include a detailed budget. This shows your estimates of how much each part of your project will cost.

Make sure to check what type of costs the funding body will agree to cover. For each item, include:

- Cost : exactly how much money do you need?

- Justification : why is this cost necessary to complete the research?

- Source : how did you calculate the amount?

To determine your budget, think about:

- Travel costs : do you need to go somewhere to collect your data? How will you get there, and how much time will you need? What will you do there (e.g., interviews, archival research)?

- Materials : do you need access to any tools or technologies?

- Help : do you need to hire any research assistants for the project? What will they do, and how much will you pay them?

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Once you’ve decided on your research objectives , you need to explain them in your paper, at the end of your problem statement .

Keep your research objectives clear and concise, and use appropriate verbs to accurately convey the work that you will carry out for each one.

I will compare …

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

A PhD, which is short for philosophiae doctor (doctor of philosophy in Latin), is the highest university degree that can be obtained. In a PhD, students spend 3–5 years writing a dissertation , which aims to make a significant, original contribution to current knowledge.

A PhD is intended to prepare students for a career as a researcher, whether that be in academia, the public sector, or the private sector.

A master’s is a 1- or 2-year graduate degree that can prepare you for a variety of careers.

All master’s involve graduate-level coursework. Some are research-intensive and intend to prepare students for further study in a PhD; these usually require their students to write a master’s thesis . Others focus on professional training for a specific career.

Critical thinking refers to the ability to evaluate information and to be aware of biases or assumptions, including your own.

Like information literacy , it involves evaluating arguments, identifying and solving problems in an objective and systematic way, and clearly communicating your ideas.

The best way to remember the difference between a research plan and a research proposal is that they have fundamentally different audiences. A research plan helps you, the researcher, organize your thoughts. On the other hand, a dissertation proposal or research proposal aims to convince others (e.g., a supervisor, a funding body, or a dissertation committee) that your research topic is relevant and worthy of being conducted.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. & George, T. (2023, November 21). How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-proposal/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- Research Process

Writing a Scientific Research Project Proposal

- 5 minute read

- 97.4K views

Table of Contents

The importance of a well-written research proposal cannot be underestimated. Your research really is only as good as your proposal. A poorly written, or poorly conceived research proposal will doom even an otherwise worthy project. On the other hand, a well-written, high-quality proposal will increase your chances for success.

In this article, we’ll outline the basics of writing an effective scientific research proposal, including the differences between research proposals, grants and cover letters. We’ll also touch on common mistakes made when submitting research proposals, as well as a simple example or template that you can follow.

What is a scientific research proposal?

The main purpose of a scientific research proposal is to convince your audience that your project is worthwhile, and that you have the expertise and wherewithal to complete it. The elements of an effective research proposal mirror those of the research process itself, which we’ll outline below. Essentially, the research proposal should include enough information for the reader to determine if your proposed study is worth pursuing.

It is not an uncommon misunderstanding to think that a research proposal and a cover letter are the same things. However, they are different. The main difference between a research proposal vs cover letter content is distinct. Whereas the research proposal summarizes the proposal for future research, the cover letter connects you to the research, and how you are the right person to complete the proposed research.

There is also sometimes confusion around a research proposal vs grant application. Whereas a research proposal is a statement of intent, related to answering a research question, a grant application is a specific request for funding to complete the research proposed. Of course, there are elements of overlap between the two documents; it’s the purpose of the document that defines one or the other.

Scientific Research Proposal Format

Although there is no one way to write a scientific research proposal, there are specific guidelines. A lot depends on which journal you’re submitting your research proposal to, so you may need to follow their scientific research proposal template.

In general, however, there are fairly universal sections to every scientific research proposal. These include:

- Title: Make sure the title of your proposal is descriptive and concise. Make it catch and informative at the same time, avoiding dry phrases like, “An investigation…” Your title should pique the interest of the reader.

- Abstract: This is a brief (300-500 words) summary that includes the research question, your rationale for the study, and any applicable hypothesis. You should also include a brief description of your methodology, including procedures, samples, instruments, etc.

- Introduction: The opening paragraph of your research proposal is, perhaps, the most important. Here you want to introduce the research problem in a creative way, and demonstrate your understanding of the need for the research. You want the reader to think that your proposed research is current, important and relevant.

- Background: Include a brief history of the topic and link it to a contemporary context to show its relevance for today. Identify key researchers and institutions also looking at the problem

- Literature Review: This is the section that may take the longest amount of time to assemble. Here you want to synthesize prior research, and place your proposed research into the larger picture of what’s been studied in the past. You want to show your reader that your work is original, and adds to the current knowledge.

- Research Design and Methodology: This section should be very clearly and logically written and organized. You are letting your reader know that you know what you are going to do, and how. The reader should feel confident that you have the skills and knowledge needed to get the project done.

- Preliminary Implications: Here you’ll be outlining how you anticipate your research will extend current knowledge in your field. You might also want to discuss how your findings will impact future research needs.

- Conclusion: This section reinforces the significance and importance of your proposed research, and summarizes the entire proposal.

- References/Citations: Of course, you need to include a full and accurate list of any and all sources you used to write your research proposal.

Common Mistakes in Writing a Scientific Research Project Proposal

Remember, the best research proposal can be rejected if it’s not well written or is ill-conceived. The most common mistakes made include:

- Not providing the proper context for your research question or the problem

- Failing to reference landmark/key studies

- Losing focus of the research question or problem

- Not accurately presenting contributions by other researchers and institutions

- Incompletely developing a persuasive argument for the research that is being proposed

- Misplaced attention on minor points and/or not enough detail on major issues

- Sloppy, low-quality writing without effective logic and flow

- Incorrect or lapses in references and citations, and/or references not in proper format

- The proposal is too long – or too short

Scientific Research Proposal Example

There are countless examples that you can find for successful research proposals. In addition, you can also find examples of unsuccessful research proposals. Search for successful research proposals in your field, and even for your target journal, to get a good idea on what specifically your audience may be looking for.

While there’s no one example that will show you everything you need to know, looking at a few will give you a good idea of what you need to include in your own research proposal. Talk, also, to colleagues in your field, especially if you are a student or a new researcher. We can often learn from the mistakes of others. The more prepared and knowledgeable you are prior to writing your research proposal, the more likely you are to succeed.

Language Editing Services

One of the top reasons scientific research proposals are rejected is due to poor logic and flow. Check out our Language Editing Services to ensure a great proposal , that’s clear and concise, and properly referenced. Check our video for more information, and get started today.

- Manuscript Review

Research Fraud: Falsification and Fabrication in Research Data

Research Team Structure

You may also like.

Descriptive Research Design and Its Myriad Uses

Five Common Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Biomedical Research Paper

Making Technical Writing in Environmental Engineering Accessible

To Err is Not Human: The Dangers of AI-assisted Academic Writing

When Data Speak, Listen: Importance of Data Collection and Analysis Methods

Choosing the Right Research Methodology: A Guide for Researchers

Why is data validation important in research?

Writing a good review article

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

Science & Quantitative Reasoning Education

Yale undergraduate research, how to write a proposal.

The abstract should summarize your proposal. Include one sentence to introduce the problem you are investigating, why this problem is significant, the hypothesis to be tested, a brief summary of experiments that you wish to conduct and a single concluding sentence. (250 word limit)

Introduction

The introduction discusses the background and significance of the problem you are investigating. Lead the reader from the general to the specific. For example, if you want to write about the role that Brca1 mutations play in breast cancer pathogenesis, talk first about the significance of breast cancer as a disease in the US/world population, then about familial breast cancer as a small subset of breast cancers in general, then about discovery of Brca1 mutations in familial breast cancer, then Brca1’s normal functions in DNA repair, then about how Brca1 mutations result in damaged DNA and onset of familial breast cancer, etc. Definitely include figures with properly labeled text boxes (designated as Figure 1, Figure 2, etc) here to better illustrate your points and help your reader wade through unfamiliar science. (3 pages max)

Formulate a hypothesis that will be tested in your grant proposal. Remember, you are doing hypothesis-driven research so there should be a hypothesis to be tested! The hypothesis should be focused, concise and flow logically from the introduction. For example, your hypothesis could be “I hypothesize that overexpressing wild type Brca1 in Brca1 null tumor cells will prevent metastatic spread in a mouse xenograph model.” Based on your hypothesis, your Specific Aims section should be geared to support it. The hypothesis is stated in one sentence in the proposal.

Specific Aims (listed as Specific Aim 1, Specific Aim 2)

This is where you will want to work with your mentor to craft the experimental portion of your proposal. Propose two original specific aims to test your hypothesis. Don’t propose more than two aims-you will NOT have enough time to do more. In the example presented, Specific Aim 1 might be “To determine the oncogenic potential of Brca1 null cell lines expressing wild type Brca1 cDNA”. Specific aim 2 might be “To determine the metastatic potential of Brca1 null cells that express WT Brca1”. You do not have to go into extensive technical details, just enough for the reader to understand what you propose to do. The best aims yield mechanistic insights-that is, experiments proposed address some mechanisms of biology. A less desirable aim proposes correlative experiments that does not address mechanistically how BRCA1 mutations generate cancer. It is also very important that the two aims are related but NOT interdependent. What this means is that if Aim 1 doesn’t work, Aim 2 is not automatically dead. For example, say you propose in Aim 1 to generate a BRCA1 knockout mouse model, and in Aim 2 you will take tissues from this mouse to do experiments. If knocking out BRCA1 results in early embryonic death, you will never get a mouse that yields tissues for Aim 2. You can include some of your mentor’s data here as “Preliminary data”. Remember to carefully cite all your sources. (4 pages max; 2 pages per Aim)

Potential pitfalls and alternative strategies

This is a very important part of any proposal. This is where you want to discuss the experiments you propose in Aims 1 and 2. Remember, no experiment is perfect. Are there any reasons why experiments you proposed might not work? Why? What will you do to resolve this? What are other possible strategies you might use if your experiments don’t work? If a reviewer spots these deficiencies and you don’t propose methods to correct them, your proposal will not get funded. You will want to work with your mentor to write this section. (1/2 page per Aim)

Cite all references, including unpublished data from your mentor. Last, First, (year), Title, Journal, volume, pages.

*8 page proposal limit (not including References), 1.5 spacing, 12pt Times New Roman font

- View an example of a research proposal submitted for the Yale College First-Year Summer Research Fellowship (PDF).

- View an example of a research proposal submitted for the Yale College Dean’s Research Fellowship and the Rosenfeld Science Scholars Program (PDF) .

Biology Research: Getting Started: Research Design/Methods

- Grant Proposals

- Research Design/Methods

- Finding Articles

- Writing & Citing

- Research Tips

- Background Information

Books on Research

- ISBN: 9781473907539

Experimental Design

Useful Resources

- Biological Procedures Online Biological Procedures Online, from BioMed Central, publishes articles that improve access to techniques and methods in the medical and biological sciences.

- Introduction to Designing Experiments A 7-part series from Films on Demand that includes how to design research, hypotheses, sampling, ethics and bias, and more.

- Exploring Qualitative Methods How to conduct research using qualitative data from Films on Demand.

- Organizing Quantitative Data Video from Films on Demand on using quantitative data.

- Statistics for Biologists This resource from Nature magazine offers guidance in using statistics in biology research

Health and Sciences Librarian

- << Previous: Grant Proposals

- Next: Finding Articles >>

- Last Updated: Feb 1, 2024 1:56 PM

- URL: https://libguides.jsu.edu/bioresearch

Thesis proposal example 2

Senior Honors Thesis Research Proposal

Albert B. Ulrich III Thesis Advisor: Dr. Wayne Leibel 11 September 1998

Introduction:

Neotropical fish of the family Cichlidae are a widespread and diverse group of freshwater fish which, through adaptive radiation, have exploited various niches in freshwater ecosystems. One such evolutionary adaptation employed by numerous taxa is miniaturization, an evolutionary process in which a large ancestral form becomes reduced in size to exploit alternative niches. A considerable amount of research has been conducted on the effects of miniaturization on amphibians (Hanken 1983), but although miniaturization has been found to occur in 85 species of freshwater South American fish, little has been done to investigate the effects which miniaturization imposes on the anatomy of the fish (Hanken and Wake 1993).

Background:

Evolution is the process by which species adapt to environmental stresses over time. Nature imposes various selective pressures on ecosystems causing adaptive radiation, where species expand and fill new niches. One such adaptation for a new niche is miniaturization. Miniaturization can be defined as “the evolution of extremely small adult body size within a lineage” (Hanken and Wake 1993). Miniaturization is observed in a variety of taxa, and evolutionary size decreases are observed in mammals and higher vertebrates, but it is more common and more pronounced in reptiles, amphibians and fish (Hanken and Wake 1993). Miniaturization evolved as a specialization which allowed the organisms to avoid selective pressures and occupy a new niche. Miniaturization as a concept is dependent on the phylogenetic assumption that the organism evolved from a larger predecessor. Over time, the miniature organism had to adapt to the new conditions as a tiny species. All of the same basic needs had to be met, but with a smaller body.

In miniature species there is a critical relationship between structure of the body and body size, and frequently this downsizing results in structural and functional changes within the animal (Harrison 1996). Within the concept of miniaturization is the assumption that the species evolved from a larger progenitor. It is necessary then to explore the effects of the miniaturization process. “Miniaturization involves not only small body size per se, but also the consequent and often dramatic effects of extreme size reduction on anatomy, physiology, ecology, life history, and behavior” (Hanken and Wake 1993).

Hanken and Wake 1993 found that the adult skulls of the salamander Thorius were lacking several bones, others were highly underdeveloped, and many species within the genus were toothless. Several invertebrate species display the wholesale loss of major organs systems as a result of the drastic reduction in body size (Hanken and Wake 1993). Hanken and Wake also have shown that morphological novelty is a common result of miniaturization. Morphological novelty, in essence, is the development of new structures in the miniature organism. For example, as body size decreases, certain vital organs will only be able to be reduced by a certain amount and still function. As a result organs such as the inner ear remain large relative to the size of the miniature skull, and structural innovations have to occur in order to support the proportionately large inner ear.

In 1983, James Hanken, at the University of Colorado determined that the adult skull of the Plethodontid salamanders could be characterized by three observations: 1) there was a limited development or even an absence of several ossified elements such as dentition and other bones; 2) there was interspecific and intraspecific variability; 3) there were novel mophological configurations of the braincase and jaw (Hanken 1983).

In his experiments, Hanken found that cranial miniaturization of the Thorius skull was achieved at the expense of ossification. Much of the ossified skeleton was lost or reduced, especially in the anterior elements, which are seen typically in larger adult salamanders (Hanken 1983). In contrast to this ossified downsizing, many of the sensory organs were not diminished in size — therefore present in greater proportion to the rest of the reduced head. He also reported that due to the geometrical space availability, there is a competition for space in reduced sized skulls, and the “predominant brain, otic capsules, and eyes have imposed structural rearrangements on much of the skull that remains” (Hanken 1983).

Hanken proposed that paedomorphosis was the mode of evolution of the plethodontid salamanders (Hanken 1983). Paedomorphosis is the state where the miniaturized structures of the adult salamanders can be described as arrested juvenile states. To support this theory, Hanken showed data where cranial skeletal reduction was less extreme in the posterior regions of the skull. One of the hallmarks of paedamorphosis is the lack of conservation in structures derived late in development. Early developed structures are highly conserved, and the latter derivations become either lost, or greatly reduced. Again, Hanken has shown that elements appearing late in development exhibit greater variation among species than do elements appearing earlier in ontogeny (Hanken 1983). But the presence of novel morphological features cannot be accounted for merely by truncated development and the retention of juvenile traits. Miniature Plethodontid salamanders display features that are not present in other species, juvenile or adult. These novel morphological features are associated with the evolution of decreased size and are postulated to compensate for the reductions occurring in other areas (Hanken 1983).

In 1985, Trueb and Alberch published a paper presenting similar results in their experiments with frogs. They explored the “relationships between body sizes of anurans and their cranial configurations with respect to the degree of ossification of the skull and two ontogenetic variables‹shape and number of differentiation events” (Trueb and Alberch 1985). Trueb and Alberch examined three morphological variables: size, sequence of differentiation events, and shape changes in individual structures. Size and snout length were measured, and the data showed that the more heavily ossified frogs tended to be smaller, whereas the less-ossified species were of average size, contrary to what was hypothesized. But Trueb and Alberch also attributed the diminution in size to paedomorphosis, citing that the smaller frogs lacked one or more of the elements typically associated with anuran skulls‹these missing elements were typically late in the developmental sequence. It is significant to note, however, that although there was an apparent paedomorphic trend, it could not be “applied unequivocally to all anuans” (Trueb and Alberch 1985). Very little research has been done on the effects of miniaturization on fish. In 1993, Buckup published a paper discussing the phylogeny of newly found minature species of Characidiin fish, but the extent of the examination was merely an acknowledgment that the species were indeed miniatures so that they could be taxonomically reclassified ( Buckup 1993). It is this deficit of knowledge with regard to miniaturization in fish that prompts this research.

Statement of the Problem:

How does miniaturization affect other vertebrates, such as fish? There are over 85 species of freshwater South American fish which are regarded as miniature, spanning 5 orders, 11 families and 40 genera (Hanken and Wake 1993). One such species, Apistogramma cacatuoides, is a South American Cichlid native to Peru. It lives in shallow water bodies in the rainforests, where miniature size is necessary. Males in this species reach approximately 8cm, and females only 5cm. This makes A. cacatuoides an ideal specimen for examination. In this senior honors thesis, I intend to examine the effects of miniaturization on cranial morphology of A. cacatuoides.

Plan of Research:

In this thesis, I will compare the cranial anatomy of A. cacatuoides to that of “Cichlasoma” (Archocentrus) nigrofasciatum, a commonly bred fish reared by aquarists known as the Convict Cichlid, a “typical” medium-sized cichlid also of South American origin. The Convicts will be examined at various stages in development, from juvenile to adult, and will be compared to A.cacatuoides.

The first part of this project will involve whole mount preparation of A. cacatuoides, utilizing the staining and clearing procedures described by Taylor and Van Dyke, 1985. This procedure involves the use of Alizarin Red and Alcian Blue to stain bone and cartilage, and takes into account the adaptations and recommendations Proposed in an earlier paper (Hanken and Wassersug 1981). The Taylor and Van Dyke procedure is specifically for the staining and clearing of small fish and other vertebrates. I tested the procedure during last semester¹s Independent Study and made a few minor adjustments to the protocol.

First, the specimens will be placed serially into an absolute ethyl alcohol solution and stained with Alcian Blue. The fish will then be neutralized in a saturated borax solution, transferred to a 20% hydrogen peroxide solution in potassium hydroxide, and then bleached under a fluorescent light. The unwanted soft tissues will then be cleared using trypsin powder, and then stained in KOH again with alizarin red. The final preparation of the fish involves rinsing the fish, and placing them serially into 40%, 70%, and finally 100% glycerin.

Following the above preparation of the specimens, the crania of the A. cacatuoides specimens will be examined for morphological variation and compared to the cranial anatomy of the Convict cichlid as a progenitor reference point examined at various developmental stages to see if paedomorphosis in indeed the mechanism of miniaturization in A. cacatuoides.

Expected Costs:

The project is estimated to cost no more that five hundred dollars for chemicals and supplies for the entire year.

Literature Cited:

Hanken, J., 1983. Miniaturization and its Effects on Cranial Morphology in Plethodontid Salamanders, Genus Thorius (Amphibia: Plethodontidae). I. Osteological Variation”. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society (London) 23: 55-75.

Hanken, James, 1983. Miniaturization and its Effects on Cranial Morhology in Plethodontid Salamanders, Genus Thorius (Amphibia, Plethodintidae): II.The Fate of the Brain and Sense Organs and Their Role in Skull Morphogenesis and Evolution . Journal of Morphology 177: 255-268.

Hanken, James and David Wake, 1993. Miniaturization of Body Size: Origanismal Consequences and Evolutionary Significance. Annual Review of Ecological Systems 24: 501-19.

Harrison, I. J., 1996. Interface Areas in Small Fish. Zoological Symposium No. 69. The Zoological Society of London: London.

Miller, P. J., 1996. Miniature Vertebrates: The Implications of Small Body Size. Symposium of the Zoological Society of London. No. 69: 15-45.

Taylor, William R. and George Van Dyke, 1985. Revised Procedures for Staining and Clearing Small Fishes and Other Vertebrates for Small Bone and Cartilage Study. Cybium. 9(2): 107-119.

Trueb, L. and P. Alberch, 1985. Miniaturization and the Anuran Skull: a Case Study of Heterochrony. Fortschritte der Zoologie. Bund 30.

Williams, T. Walley, 1941 Bone and Cartilage. Stain. Tech. 16:23-25.

Department of Biological Sciences

Examples of Undergraduate Research Projects

Fall 2021 projects, previous projects.

- How it works

Published by Robert Bruce at August 29th, 2023 , Revised On September 5, 2023

Biology Research Topics

Are you in need of captivating and achievable research topics within the field of biology? Your quest for the best biology topics ends right here as this article furnishes you with 100 distinctive and original concepts for biology research, laying the groundwork for your research endeavor.

Table of Contents

Our proficient researchers have thoughtfully curated these biology research themes, considering the substantial body of literature accessible and the prevailing gaps in research.

Should none of these topics elicit enthusiasm, our specialists are equally capable of proposing tailor-made research ideas in biology, finely tuned to cater to your requirements.

Thus, without further delay, we present our compilation of biology research topics crafted to accommodate students and researchers.

Research Topics in Marine Biology

- Impact of climate change on coral reef ecosystems.

- Biodiversity and adaptation of deep-sea organisms.

- Effects of pollution on marine life and ecosystems.

- Role of marine protected areas in conserving biodiversity.

- Microplastics in marine environments: sources, impacts, and mitigation.

Biological Anthropology Research Topics

- Evolutionary implications of early human migration patterns.

- Genetic and environmental factors influencing human height variation.

- Cultural evolution and its impact on human societies.

- Paleoanthropological insights into human dietary adaptations.

- Genetic diversity and population history of indigenous communities.

Biological Psychology Research Topics

- Neurobiological basis of addiction and its treatment.

- Impact of stress on brain structure and function.

- Genetic and environmental influences on mental health disorders.

- Neural mechanisms underlying emotions and emotional regulation.

- Role of the gut-brain axis in psychological well-being.

Cancer Biology Research Topics

- Targeted therapies in precision cancer medicine.

- Tumor microenvironment and its influence on cancer progression.

- Epigenetic modifications in cancer development and therapy.

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors and their role in cancer immunotherapy.

- Early detection and diagnosis strategies for various types of cancer.

Also read: Cancer research topics

Cell Biology Research Topics

- Mechanisms of autophagy and its implications in health and disease.

- Intracellular transport and organelle dynamics in cell function.

- Role of cell signaling pathways in cellular response to external stimuli.

- Cell cycle regulation and its relevance to cancer development.

- Cellular mechanisms of apoptosis and programmed cell death.

Developmental Biology Research Topics

- Genetic and molecular basis of limb development in vertebrates.

- Evolution of embryonic development and its impact on morphological diversity.

- Stem cell therapy and regenerative medicine approaches.

- Mechanisms of organogenesis and tissue regeneration in animals.

- Role of non-coding RNAs in developmental processes.

Also read: Education research topics

Human Biology Research Topics

- Genetic factors influencing susceptibility to infectious diseases.

- Human microbiome and its impact on health and disease.

- Genetic basis of rare and common human diseases.

- Genetic and environmental factors contributing to aging.

- Impact of lifestyle and diet on human health and longevity.

Molecular Biology Research Topics

- CRISPR-Cas gene editing technology and its applications.

- Non-coding RNAs as regulators of gene expression.

- Role of epigenetics in gene regulation and disease.

- Mechanisms of DNA repair and genome stability.

- Molecular basis of cellular metabolism and energy production.

Research Topics in Biology for Undergraduates

- 41. Investigating the effects of pollutants on local plant species.

- Microbial diversity and ecosystem functioning in a specific habitat.

- Understanding the genetics of antibiotic resistance in bacteria.

- Impact of urbanization on bird populations and biodiversity.

- Investigating the role of pheromones in insect communication.

Synthetic Biology Research Topics

- Design and construction of synthetic biological circuits.

- Synthetic biology applications in biofuel production.

- Ethical considerations in synthetic biology research and applications.

- Synthetic biology approaches to engineering novel enzymes.

- Creating synthetic organisms with modified functions and capabilities.

Animal Biology Research Topics

- Evolution of mating behaviors in animal species.

- Genetic basis of color variation in butterfly wings.

- Impact of habitat fragmentation on amphibian populations.

- Behavior and communication in social insect colonies.

- Adaptations of marine mammals to aquatic environments.

Also read: Nursing research topics

Best Biology Research Topics

- Unraveling the mysteries of circadian rhythms in organisms.

- Investigating the ecological significance of cryptic coloration.

- Evolution of venomous animals and their prey.

- The role of endosymbiosis in the evolution of eukaryotic cells.

- Exploring the potential of extremophiles in biotechnology.

Biological Psychology Research Paper Topics

- Neurobiological mechanisms underlying memory formation.

- Impact of sleep disorders on cognitive function and mental health.

- Biological basis of personality traits and behavior.

- Neural correlates of emotions and emotional disorders.

- Role of neuroplasticity in brain recovery after injury.

Biological Science Research Topics:

- Role of gut microbiota in immune system development.

- Molecular mechanisms of gene regulation during development.

- Impact of climate change on insect population dynamics.

- Genetic basis of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s.

- Evolutionary relationships among vertebrate species based on DNA analysis.

Biology Education Research Topics

- Effectiveness of inquiry-based learning in biology classrooms.

- Assessing the impact of virtual labs on student understanding of biology concepts.

- Gender disparities in science education and strategies for closing the gap.

- Role of outdoor education in enhancing students’ ecological awareness.

- Integrating technology in biology education: challenges and opportunities.

Biology-Related Research Topics

- The intersection of ecology and economics in conservation planning.

- Molecular basis of antibiotic resistance in pathogenic bacteria.

- Implications of genetic modification of crops for food security.

- Evolutionary perspectives on cooperation and altruism in animal behavior.

- Environmental impacts of genetically modified organisms (GMOs).

Biology Research Proposal Topics

- Investigating the role of microRNAs in cancer progression.

- Exploring the effects of pollution on aquatic biodiversity.

- Developing a gene therapy approach for a genetic disorder.

- Assessing the potential of natural compounds as anti-inflammatory agents.

- Studying the molecular basis of cellular senescence and aging.

Biology Research Topic Ideas

- Role of pheromones in insect mate selection and behavior.

- Investigating the molecular basis of neurodevelopmental disorders.

- Impact of climate change on plant-pollinator interactions.

- Genetic diversity and conservation of endangered species.

- Evolutionary patterns in mimicry and camouflage in organisms.

Biology Research Topics for Undergraduates

- Effects of different fertilizers on plant growth and soil health.

- Investigating the biodiversity of a local freshwater ecosystem.

- Evolutionary origins of a specific animal adaptation.

- Genetic diversity and disease susceptibility in human populations.

- Role of specific genes in regulating the immune response.

Cell and Molecular Biology Research Topics

- Molecular mechanisms of DNA replication and repair.

- Role of microRNAs in post-transcriptional gene regulation.

- Investigating the cell cycle and its control mechanisms.

- Molecular basis of mitochondrial diseases and therapies.

- Cellular responses to oxidative stress and their implications in ageing.

These topics cover a broad range of subjects within biology, offering plenty of options for research projects. Remember that you can further refine these topics based on your specific interests and research goals.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are some good research topics in biology?

A good research topic in biology will address a specific problem in any of the several areas of biology, such as marine biology, molecular biology, cellular biology, animal biology, or cancer biology.

A topic that enables you to investigate a problem in any area of biology will help you make a meaningful contribution.

How to choose a research topic in biology?

Choosing a research topic in biology is simple.

Follow the steps:

- Generate potential topics.

- Consider your areas of knowledge and personal passions.

- Conduct a thorough review of existing literature.

- Evaluate the practicality and viability.

- Narrow down and refine your research query.

- Remain receptive to new ideas and suggestions.

Who Are We?

For several years, Research Prospect has been offering students around the globe complimentary research topic suggestions. We aim to assist students in choosing a research topic that is both suitable and feasible for their project, leading to the attainment of their desired grades. Explore how our services, including research proposal writing , dissertation outline creation, and comprehensive thesis writing , can contribute to your college’s success.

You May Also Like

Welcome to the most comprehensive resource page of climate change research topics, a crucial field of study central to understanding […]

How many universities in Canada? Over 100 private universities and 96 public ones, the top ones include U of T, UBC, and Western University.

A preliminary literature review is an initial exploration of existing research on a topic, setting the foundation for in-depth study.

Ready to place an order?

USEFUL LINKS

Learning resources, company details.

- How It Works

Automated page speed optimizations for fast site performance

Researched by Consultants from Top-Tier Management Companies

Powerpoint Templates

Icon Bundle

Kpi Dashboard

Professional

Business Plans

Swot Analysis

Gantt Chart

Business Proposal

Marketing Plan

Project Management

Business Case

Business Model

Cyber Security

Business PPT

Digital Marketing

Digital Transformation

Human Resources

Product Management

Artificial Intelligence

Company Profile

Acknowledgement PPT

PPT Presentation

Reports Brochures

One Page Pitch

Interview PPT

All Categories

Top 11 Biology Research Proposal Ideas with Samples and Examples (Free PDF Attached)

Hanisha Kapoor

“Cancer cure is finally here! Doctors found the miracle drug! Cancer in all patients vanishes,” these have been some screaming headlines in newspapers in 2022. Even as the discovery of the cure (with many qualifiers as of now) is a miraculous achievement, it took real hard work.

At the centre of any sublime achievement in health sciences is a team of world-class researchers and doctors, who worked hard to draft a biology research proposal idea that got the nod of funding agencies. In the specific example cited above, Dostarlimab, was the drug that was researched.

What we illustrate through this study is the necessity and essentiality of crafting a research proposal that meets its goals and outperforms competition.

Explore this guide to write an impeccable research proposal to ensure you always write a winning proposition, and turn ideas into reality.

In this blog, we study the nuts and bolts of a well-structured presentation. The thing to ensure is that the research proposal covers all bases and leaves nothing to chance.

Biology Research Proposal Ideas Templates to Get Funded for New Discoveries and Advancements

If you want to project new developments and innovation that your research will bring to life, perk up your presentations with SlideTeam’s well-designed PPT Templates. Whether it is about showcasing different experiments or drug testing, incorporate our ready-made PPT Templates to gain that extra edge and purpose.

Persuade reviewers to support your findings using our actionable PowerPoint diagrams.

Writing a thorough dissertation proposal is a stepping stone to excelling in your academic projects. Read this blog and learn more on structuring your thesis.

Browse this collection of PowerPoint slides to make a substantial positive impact on how your research proposal is seen.

Let's begin!

Template 1: Biology Research Proposal PowerPoint Template

This is a 29-slide research proposal PPT diagram to help you put forth your ideas and discoveries in the field of biology. Use these well-crafted PowerPoint Templates to give your audience an overview of the project. You can also showcase steps of your research process, requirements, and other capabilities for completing the study. This ready-made PowerPoint Deck also comprises a slide on Budgeting to help you convince your reviewers to sanction that grant. Download this PPT Template now!

Download this template

Template 2: Biology Cover Letter Research Proposal Idea PPT Slide

As the adage goes, First Impression is the Last Impression . Ensure that you leave a long-lasting impression on your audience with the showcasing of your new research using this engaging PPT Template. Deploy a predesigned and easy-to-use PowerPoint Layout to pitch your client your project idea. Get a head-start from your reviewer and dig deeper into your research with this template as the reference. Download now!

Grab this slide

Template 3: Vision and Mission for Biology Research Proposal PowerPoint Graphic

Want to showcase the aim and goal of your research project? Get this content-ready PPT Template to pen down the vision and mission of your biology research proposal project. Present your future goals and expectations from this study with this fully editable PowerPoint Slide and help your audience comprehend your mission for this project. This PPT diagram can easily be downloaded. Just click the link below and use it as per requirements.

Grab this template

Template 4: Biology Project Objectives PowerPoint Template

What you plan to achieve by the end of the project is what matters the most to the reviewers. Thus, ensure that you highlight the project objectives, which include timelines, budget, etc., with this content-ready PowerPoint Template. Leave no scope for error and uncertainties in your proposal. Get your audience on board with you on your research idea using this customizable PPT slide. Download now!

Template 5: Biology Research Idea Context PPT Diagram

Here is another ready-to-use PowerPoint Template that helps you with the framework of how to contextualize your project. Walk your audience through the strategies you plan to execute to create practical solutions to the problems. Incorporate this fully editable PPT diagram and highlight the best possible treatment, medicines, vaccinations, etc., to combat disease. Use this custom-made PowerPoint Slide and present your detailed study with confidence. Grab this slide now!

Template 6: Methods for Biology Research Proposal PowerPoint Slide

This ready-made PowerPoint Diagram is well designed to help you demonstrate actionable methods that fight diseases. Be methodical and explain each process using this PPT design. Convince reviewers and ensure to get funded for your research with this customizable PowerPoint Graphic. Download now!

Template 7: Roadmap Biology PowerPoint Template

Deploy this preset as a communication tool to draw a painting review of your action plan. Define major tasks and goals and lay out your strategies to achieve those targets. This roadmap PPT Template helps showcase major steps and milestones in your journey. Use this ready-made PowerPoint Graphic as a guide to keep everyone in your team informed on the project status. Download now!

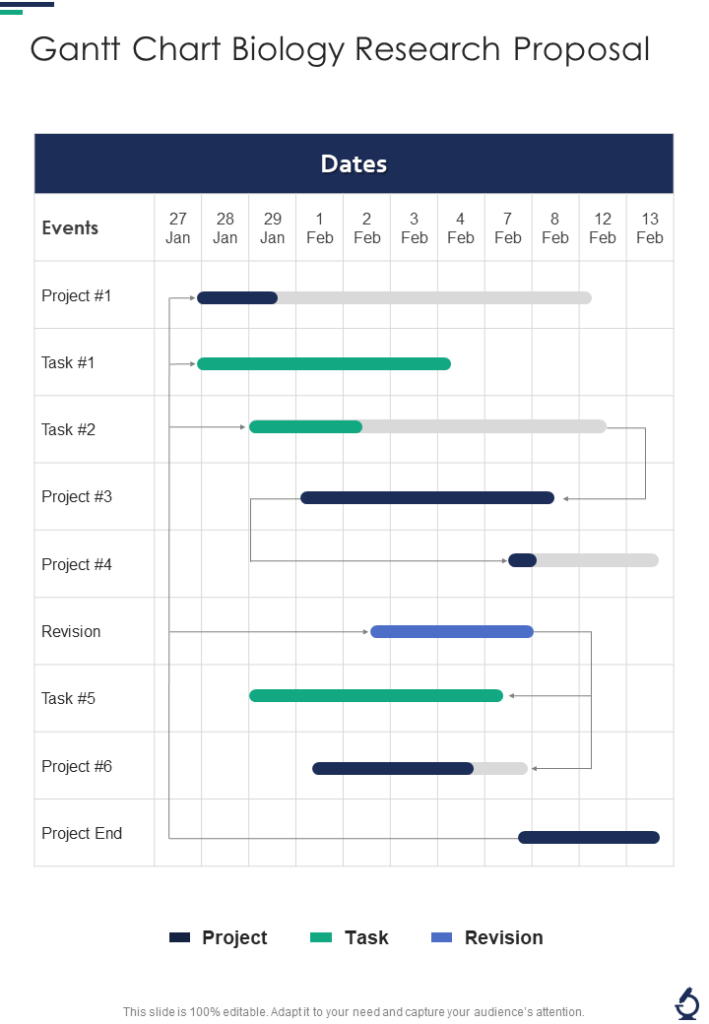

Template 8: Gantt Chart Research Proposal PowerPoint Design

Wish to complete your project on time? Grab this actionable PowerPoint Template and set dates and times for each task. This PPT Template also allows you to keep track of business activities and ensure your project’s timely completion . It is a customizable PowerPoint Diagram to help you change time and date as per requirements. Grab this useful PowerPoint Layout now!

Template 9: Budget Research Proposal PPT Diagram

Struggling to create a budget for your research proposal idea? How about using this illustration to outline a detailed expected project cost? This PPT Template helps you list all activities and the estimated cost of each. Justify your budget and get approval from your stakeholders using this customized PPT Diagram. Download now!

Template 10: Next Steps for Biology Research Proposal PowerPoint Template

Want to seal the deal with researchers for your next biology project? Use this content-ready PowerPoint Template and state the next steps for your study in a professional manner. This PPT Diagram also allows you to include some content. Use this template to convince your reviewers that you are a step ahead of all possible negative scenarios. Download now!

BONUS SLIDE

Contact us biology research ppt side.

It is impolite not to leave your contact number for your researchers or stakeholders. Thus, ensure you provide a point of contact so that your clients reach out to you without any inconvenience. Deploy this neat, clutter-free PPT Slide to add your address, phone number, and email id. It is a custom-made slide. You can use it as per requirement. Download now!

Justifying and presenting practical ways to study a research problem is a task. Thus, ease the burden and incorporate SlideTeam's ready-made research proposal presentation PPT Templates to showcase your analysis and in-depth research on a subject. These handy PowerPoint Diagrams can be customized with a single click. Download these ready-made and premium PowerPoint Slides from our monthly, semi-annual, annual, annual + custom design subscriptions here .

PS: Wish to present your scholarly literature review in a concise and easy manner? Explore this exclusive guide replete with literature review templates to make sure you reach the public as well, with your authoritative point of view.

FAQs On Biology Research Proposal Ideas

How to write a research proposal in biology.

Every research proposal is unique and aims to tackle a specific problem statement or hypothesis. It should focus on potentially valuable outcomes, fill in the gaps, and lead to progress of Scientific Knowledge in general. In biology, of course, there is still endless ground to cover in terms of our ability to tackle diseases; the Covid-19 pandemic brought out all our inadequacies to the fore as well.

As the starting point for any effort to improve things, writing an effective research proposal in biology is the key skill to inculcate for hard-core researchers and the academia. Given below are the five key steps we need to master before we put pen to paper for a biology research paper that rocks.

- Study the existing literature

- Narrow the topic down

- Identify keywords

- Formulate the topic

What is the purpose of research in the field of Biology?

Biological scientists conduct research to gain better understanding of life processes and apply that understanding to developing new products and processes. Here, the aim is to know better and deeper, and work to develop novel solutions to diseases. Remember, disease prevention is even more important than developing cures.

How long should a biology proposal be?

A focused and extensive thesis proposal should not be longer than 12 pages of text. Figures and data can be presented on additional pages, if these are critical to the persuasive pitch. Please remember it is purpose of the research proposal, its organization of information and the real-life connect it has that gets it the money. Length of the proposal is required, but a part of the format that every other researcher will have to comply to. You shine when your problem statement and hypothesis are the most relevant.

What are the features of a successful biology research proposal?

A good research proposal must:

- Cover the basics

- Describe the relevance

- Focus on the significance of the research

- Explain the approach

- Highlight your expertise

In short, explaining your approach in a relevant manner is the key differentiator that mark out the successful projects as a class apart. Your sincerity of purpose and attention to detail also has to be evident when it is show-time for presentations.

Download the free Biology Research Proposal .

Related posts:

- How to Design the Perfect Service Launch Presentation [Custom Launch Deck Included]

- Quarterly Business Review Presentation: All the Essential Slides You Need in Your Deck

- [Updated 2023] How to Design The Perfect Product Launch Presentation [Best Templates Included]

- 99% of the Pitches Fail! Find Out What Makes Any Startup a Success

Liked this blog? Please recommend us

Top 10 Impactful Ways of Writing a Research Design Proposal With Samples and Examples

Top 10 Business Loan Proposal Templates to Ensure Funding (Free PDF Attached)

This form is protected by reCAPTCHA - the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Digital revolution powerpoint presentation slides

Sales funnel results presentation layouts

3d men joinning circular jigsaw puzzles ppt graphics icons

Business Strategic Planning Template For Organizations Powerpoint Presentation Slides

Future plan powerpoint template slide

Project Management Team Powerpoint Presentation Slides

Brand marketing powerpoint presentation slides

Launching a new service powerpoint presentation with slides go to market

Agenda powerpoint slide show

Four key metrics donut chart with percentage

Engineering and technology ppt inspiration example introduction continuous process improvement

Meet our team representing in circular format

Cell Biology Preliminary Exam Format

form_preliminary_exam.pdf

Scroll to the bottom of this page for information about prelim practice sessions!

Research Proposal:

The proposal should be relevant to your anticipated thesis project. A successful written proposal should devise specific research aims that seek to answer an important scientific question, as identified by the student through a careful reading of the literature, including that encountered in formal coursework and lab rotations.

The research proposal will be in the form of an 11 page research proposal, excluding references. The format of the proposal will consist of 5 sections:

- Title Page with a brief abstract.

- Three pages of Historical Background.

- Specific Aims page.

- 1 - 1.5 pages of Significance and Innovation.

- 4.5 - 5 pages of Research Approach.

The proposal follows the NIH/NRSA guidelines with the additional 3 page historical review.

The formatting should be 11-point Arial with 0.5-inch margins on left, right, top, and bottom and single spaced.

The proposal is to be emailed as a PDF document to the DGS and committee members 10 days before your scheduled exam date. Your DGS's E-mail is: [email protected] .

The oral exam is scheduled to last 2 hours and begins with the student's brief 20-minute PowerPoint presentation of the proposal, in sufficient background and experimental detail for the committee to determine significance and feasibility. Following the presentation the exam will primarily focus on a critical evaluation of the research proposal and the student’s background knowledge of Cell Biology as it relates to their coursework and thesis proposal. This part of the examination is designed to determine the limits of the student’s knowledge and test their ability to think logically and critically.

Research Proposal Tips and Guidelines:

2. Historical Background: 3 pages

The review needs to have a historical perspective, tracing the current project from the key, founding observations to the present, and should highlight the most important discoveries, models and paradigms, detailing why they are significant and how they advanced the field. Your background should:

- Note the key findings that brought the field to its current state.

- Offer a critical perspective - if you feel that the field needs redirection, say so. If you feel that the field is embracing important but untested assumptions, say so. If you feel that particular groups or individuals have made particularly remarkable contributions to the field, say so. If you can identify landmark studies that you feel greatly influenced the field, highlight them and note why they are (were) significant.

- Conclude with how the background has led to the hypothesis or statement of unmet need that will form the basis of your Thesis Proposal and Specific Aims.

3. Specific Aims: 1 page

State concisely the goals of the proposed research and summarize the expected outcome(s), including the impact that the results of the proposed research will exert on the research field(s) involved.

4. Significance and Innovation: 1 – 1.5 page

- Explain the importance of the problem or critical barrier to progress in the field that the proposed project addresses.

- Explain how the proposed project will improve scientific knowledge, technical capability in one or more broad fields.

- Describe how the concepts, methods, technologies that drive this field will be changed if the proposed aims are achieved.

- Explain how the application challenges and seeks to shift current research paradigms.

- Describe any novel theoretical concepts, approaches or methodologies, instrumentation or intervention(s) to be developed or used, and any advantage over existing methodologies, instrumentation or intervention(s).

- Explain any refinements, improvements, or new applications of theoretical concepts, approaches or methodologies, instrumentation or interventions.

5. Approach: 4.5 – 5 pages

- Describe the overall strategy, methodology, and analyses to be used to accomplish the specific aims of the project.

- Discuss how the data will be collected, analyzed, and interpreted.

- Discuss potential problems, alternative strategies, and benchmarks for success anticipated to achieve the aims.

** A note on preliminary data: A student is allowed to utilize their own preliminary data related to their proposal, however, preliminary data is not required or expected for this exam. Properly cited published data from others can and should be used to inform project feasibility.

Q: So, what is a practice exam, and why should I consider doing one?

A: the practice exam group is essentially two fold....

Part 1: Before prelim season, we go through what to expect in a prelim, how to prepare, what goes in your document, choosing your committee, best practices in designing your talk, etc. This all happens over the course of two-three meetings.

Part 2: During prelim season, we have each second year schedule a practice prelim. In this practice, the student presents their project to their peers. The audience (open to any cell bio student) probes the presenters knowledge and understanding of their project by asking questions, ideally similar to what they experienced in their prelim.

The benefit to all of this is for the prelim-ers to know what to expect, diminish nerves, encourage better preparation, and provide a support system during this stressful process. For the older students, this group provides a productive way to interact with and meet the second years, serve as mentors, share their experiences, see what other labs in the department are starting to work on, and promoted a scientific community for the department.

- Learn English

- Universities

- Practice Tests

- Study Abroad

- Knowledge Centre

- Ask Experts

- Study Abroad Consultants

- Post Content

Biology Research Proposal: Guidelines and Examples

This article will give you the guidelines on how to write a good research proposal. Furthermore, if you lack idea's for writing a research proposal in the field of Biology/Life science, you will find many idea's in this article which you can use to write a project proposal of your own.

Writing a good research proposal is part and parcel in the life of an academician, student, scientist. You may need to write research proposals for PhD applications, for scholarships, for post-doctoral fellowships, as well as for getting grants and funding. Guidelines You may be very intelligent and have an excellent idea but to convince others about your idea, you need to present it excellently. First of all of you need to plan out every detail of your idea, so that you can predict timeline, requirements and most importantly what all you can infer from your data. Secondly you need to write it out in such a manner that you convince the pioneers of your field that your idea is excellent and it should definitely be translated into actual research. While in some cases the format and word limit of the proposals is mentioned, in other cases you have to write according to your own judgement. The format of a research proposal should include the following basics. 1. Title: The title should be precise and unassuming. Do not write – 'To develop cure for cancer' if in actually you want to check metastatic properties of X compound. A proposal is the not place where you want to make an interesting title that doesn't speak sufficiently about the project. Don't write – 'How do lysosomes eat?' if your project is about pathways involved in degradation inside lysosomes. Be scientific. Don't make the title too lengthy such that it is difficult to understand. 2. Abstract / Summary: In most cases the person reviewing your proposal will decide to read the entire proposal only on the basis of your abstract. So your abstract should be succinct and catchy at the same time. Ideally don't let it exceed 250 words. Avoid excess of technical details in the abstract and emphasize more on the idea and its significance. 3. Significance: Write exactly why is your idea so important. What are the reasons that such research should definitely be carried out. What is the benefit from the research going to be? 4. Objectives/ Aims: Write down the different objectives and aims that are included in your project. It is preferable to break down your project into sections and give each of them a heading – these can act as your objectives/aims. 5. Background / Literature review: Here in put in all the data that has led to the idea. Give proper references for all of the information. Make sure that it flows in logical order and it is possible to connect the statements to each other. If possible divide the background into subheadings all of which reflect the individual objectives. Subheadings can also be made according to any other suitable factors. The background should only include what is relevant for your project and not excess details – e.g. you want to characterize expression level using RT-PCR. So don't start with history of RT-PCR etc., just give a few examples(along with references) wherein RT-PCR has been used for the same purpose. 6. Methodology: This is where you finally explain how you intend to go about your work. The level of detail depends upon the requirements of the reviewer. Usually for grants high level of detail is required in this step. Explain the methodology of each objective in explicit detail. Any references used in section should be properly mentioned. It is also advisable to include a timeline in this section. The timeline should show how much time will be required for each step (e.g. 1st objective – 6months, 2nd objective – 2 years etc.). It is ideal to include a flow chart that illustrates your methodology as well as timeline. Herein you should also include the expected results as well as what interpretations can be made from those results. Furthermore, you need to add what you would do next if you achieve those results – whatever they might be. 7. References: Make a list of all the references used in the proposal. They should be in any one of the standard formats such as APA or Harvard Style referencing. They can be ordered either alphabetically or according to order in which they appear in the proposal. There shouldn't be difference in font or format in the entire reference list. The references should not include general websites such as Wikipedia or blogs, they can include books and journal articles. Your proposal should be easy read. Highlight all the important points so that a person skimming through it is also able to get the complete gist. Always maintain flow of thought while writing. Double check your work for grammatical errors and typos as they leave a very bad impression on the reviewer. Make sure that any figures, tables or flow charts included in the proposal are properly labelled. Examples For those of you struggling for a good idea to write a proposal on here are a few suggestions: 1. Gene/protein characterization (Molecular Biology) : Pick your favourite pathway and see if any gene's functions are still not known completely. Many times books mention such genes/proteins which have still not been worked on much. Gene characterization can involve – its expression levels, whether it is under an inducible promoter or constitutive promoter, which all cells/tissues it expresses in, which developmental stage it expresses in, effect of knockdown/knockout of the gene etc. Protein characterization – in addition to the previous steps one include – structure, location within the cell, presence of PTMs, interacting partners etc. 2. Checking various properties of particular compound(s) (Biochemistry) : Pick a medicinal plant that has not been worked on much and check the properties of its extracts. These could include antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, anti-viral, anti-cancer, etc. You can include further characterization of the extracts that give any positive result to identify the exact compound (by TLC, GC-MS, reagent based tests etc.). 3. Genome analysis for particular traits (Genomics/Bioinformatics) : You can compare genomes of species of economical or medical interest to find out different things such as difference in pathways, presence of homologs etc. You can either compare host and pathogen genomes or you can compare genomes of wild and true bred varieties of crop plants, or genomes of different types of parasite that attack the same host etc. 4. Effect of environmental factors on organisms (Environmental ecology/microbiology) : There are so many pollutants and chemicals in our environment. Pick one or few and develop a hypothesis on how they affect the local fauna and flora. Design experiments that can prove your hypothesis. 5. Population level studies: You can write a proposal about metagenomic studies carried out in different locations. E.g. Archaebacteria in swamp areas, fungi in Antarctic, bacteria in deep sea vents etc.

Related Articles