- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Abduction of Children

Introduction, general overviews.

- Offense, Offender, and Victim Characteristics

- Familial Abduction

- Stranger Abduction

- Awareness and Prevention

- AMBER Alert and Other Official Responses

- Social Constructions

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Child Protection

- Child Trafficking and Slavery

- Child Welfare Law in the United States

- Children and Violence

- Divorce and Custody

- History of Childhood in America

- Innocence and Childhood

- Moral Panics

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Agency and Childhood

- Childhood and the Colonial Countryside

- Indigenous Childhoods in India

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Abduction of Children by J. Mitchell Miller , Stephanie M. Koskinen LAST REVIEWED: 11 October 2021 LAST MODIFIED: 25 September 2019 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199791231-0226

Few crime topics elicit as much fear and concern as child abduction, which is also commonly known as child kidnapping. Child abduction, or kidnapping, is a criminal offense that entails the wrongful taking of a minor by force or violence, manipulation or fraud, or persuasion. There are basically two types of child abduction; familial-parental and the much-exaggerated stranger abductor. Parental abductions are heavily contextualized in child custody and involve far less physical danger to child victims than stranger abductions, which include the majority of violence and sexual violence associated with more extreme abduction events. Despite the popular culture myth of “abduction waves” and pedophiles lurking in the shadows, child abduction is actually a rare phenomenon, as indicated by Shutt, et al. 2004 (cited under Social Constructions ), which likened abduction likelihood to the rarity of a lightning strike. Nonetheless, media hype and sensationalism have framed both popular culture and social-legal constructions of abduction frequency, risk, and offender and victim stereotypes, most notably stranger/pedophile abductors and abduction epidemics. The extant academic literature on child abduction can be observed as a three-pronged typology of 1) historical works, more so accounts of well-known US child kidnappings such as the Lindbergh baby, Adam Walsh, and, more recently, Elizabeth Smart, and international research on abduction for ransom, custody, vice work, and military servitude; 2) legal overviews and opinions, both domestically and internationally, with the latter especially focused on abduction legislation initiatives within Hague Conference; and 3) the focus of this article, empirical scientific works primarily appearing in refereed journal articles. The majority of this literature originates from the behavioral (psychology) and social sciences (criminology and criminal justice, sociology, and political science) and, to a lesser degree, from professional school orientations (social work, nursing, and public health). As a rare event and relatively myopic, though seriously consequential, phenomenon, there isn’t a discernable number of reference works, anthologies, or established published bibliographies informing the child abduction knowledge base. Fortunately, there is a sizeable body of empirical works on child abduction to characterize the nature of the offense, its perpetrator and victim participants, and responses by juvenile and criminal justice as well as other stakeholder agencies. While substantial research attention has addressed child abduction in Africa, Latin America, and parts of Europe, this coverage is based on American research over the last few decades. This empirical literature on child abduction is presented in annotated form as a thematic taxonomy comprised of the following: 1) General Overviews , 2) Offense, Offender, and Victim Characteristics , 3) Familial Abduction , 4) Stranger Abduction , 5) Awareness and Prevention , 6) AMBER Alert and Other Official Responses , and 7) Social Constructions .

Research on child abduction in Boudreaux, et al. 2000 and more recently Walsh, et al. 2016 provides general overviews of the phenomenon. Palmer and Noble 1984 places selective emphasis on incidence rates, motivations, abduction typologies, and historical perspectives, while Heide, et al. 2009 synthesizes the literature on sexually motivated events. These refereed journal articles collectively constitute an empirical overview of child abduction that is enriched by an Oxford University Press book, Fass 1997 , and a technical report, Finkelhor, et al. 1990 , which detail and contextualize the general nature of abduction events.

Boudreaux, M. C., W. D. Lord, and S. E. Etter. “Child Abduction: An Overview of Current and Historical Perspectives.” Child Maltreatment 5.1 (2000): 63–71.

This journal article provides a comprehensive review of empirical literature on child abduction extant at the turn of the 20th century. Major themes include incidence rates, dichotomous operational definition of child abduction (legal/social), victim and offender characteristics, and a motivational typology (maternal longing, sex, retribution, profit, and homicidal intent). Risk factors, victim selection, and evidence-based responses such as child safety training programs and improved investigative practices are also summarized.

Fass, P. S. Kidnapped: Child Abduction in America . New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

This book presents a chronological unfolding of child abduction in the United States. Moving through famous kidnapping cases in American history, from the Ross case (“the crime of the century”) to the Vanderbilt custody abduction and the Lindbergh kidnapping, child abduction is characterized as a rare event exaggerated by the press. Fass presents narrative insight into family life, parenting, and media coverage.

Finkelhor, D., A. Sedlak, and G. T. Hotaling. Missing, Abducted, Runaway, and Thrownaway Children in America: First Report, Numbers and Characteristics National Incidence Studies: Executive Summary. Darby, PA: Diane, 1990.

This report provides a typology of missing and abducted children based on FBI case data. The authors present national estimates in nonfamily and family abduction categories including missing children data on cases where the children have run away or have otherwise gone missing without implication of any crime. The authors urge special attention to and policy focus on high-risk children, who are most likely to be victimized or become perpetrators of crime.

Heide, K. M., E. Beauregard, and W. C. Myers. “Sexually Motivated Child Abduction Murders: Synthesis of the Literature and Case Illustration.” Victims and Offenders 4.1 (2009): 58–75.

This analysis of sexual murders that involve children focuses on offenders who abduct their victims. Offender characteristics are studied, touching on trauma at birth, behavioral issues in childhood, and emotional and physical abuse. The authors suggest that a delay or cessation in personality development may be the root cause for offenders’ actions.

Palmer, C. E., and D. N. Noble. “Child Snatching: Motivations, Mechanisms, and Melodrama.” Journal of Family Issues 5.1 (1984): 27–46.

This article features data from a variety of offender and criminal justice professional interviews. The authors dichotomize motivations for “child snatching” between concern for the child and satisfaction of personal needs. Common factors among child abduction cases are analyzed, such as motivations, planning, hostility, trauma, familial involvement, and agency involvement. The authors recommend extended study of child snatchers and increased involvement by law enforcement.

Walsh, J. A., J. L. Krienert, and C. L. Comens. “Examining 19 Years of Officially Reported Child Abduction Incidents (1995–2013): Employing a Four Category Typology of Abduction.” Criminal Justice Studies 29.1 (2016): 21–39.

This journal article uses NIBRS data to identify child abduction characteristics. Findings suggest that media sensationalism is the cause of misconceptions and an overemphasis on stranger abduction, which are rare in comparison to acquaintance or family abductions.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Childhood Studies »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Abduction of Children

- Aboriginal Childhoods

- Addams, Jane

- ADHD, Sociological Perspectives on

- Adolescence and Youth

- Adolescent Consent to Medical Treatment

- Adoption and Fostering

- Adoption and Fostering, History of Cross-Country

- Adoption and Fostering in Canada, History of

- Advertising and Marketing, Psychological Approaches to

- Advertising and Marketing, Sociocultural Approaches to

- Africa, Children and Young People in

- African American Children and Childhood

- After-school Hours and Activities

- Aggression across the Lifespan

- Ancient Near and Middle East, Child Sacrifice in the

- Animals, Children and

- Animations, Comic Books, and Manga

- Anthropology of Childhood

- Archaeology of Childhood

- Ariès, Philippe

- Attachment in Children and Adolescents

- Australia, History of Adoption and Fostering in

- Australian Indigenous Contexts and Childhood Experiences

- Autism, Females and

- Autism, Medical Model Perspectives on

- Autobiography and Childhood

- Benjamin, Walter

- Bereavement

- Best Interest of the Child

- Bioarchaeology of Childhood

- Body, Children and the

- Bourdieu, Pierre

- Boy Scouts/Girl Guides

- Boys and Fatherhood

- Breastfeeding

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie

- Bruner, Jerome

- Buddhist Views of Childhood

- Byzantine Childhoods

- Child and Adolescent Anger

- Child Beauty Pageants

- Child Homelessness

- Child Mortality, Historical Perspectives on Infant and

- Child Protection, Children, Neoliberalism, and

- Child Public Health

- Childcare Manuals

- Childhood and Borders

- Childhood and Empire

- Childhood as Discourse

- Childhood, Confucian Views of Children and

- Childhood, Memory and

- Childhood Studies and Leisure Studies

- Childhood Studies in France

- Childhood Studies, Interdisciplinarity in

- Childhood Studies, Posthumanism and

- Childhoods in the United States, Sports and

- Children and Dance

- Children and Film-Making

- Children and Money

- Children and Social Media

- Children and Sport

- Children and Sustainable Cities

- Children as Language Brokers

- Children as Perpetrators of Crime

- Children, Code-switching and

- Children in the Industrial Revolution

- Children with Autism in a Brazilian Context

- Children, Young People, and Architecture

- Children's Humor

- Children’s Museums

- Children’s Parliaments

- Children’s Reading Development and Instruction

- Children's Views of Childhood

- China, Japan, and Korea

- China's One Child Policy

- Citizenship

- Civil Rights Movement and Desegregation

- Classical World, Children in the

- Clothes and Costume, Children’s

- Colonial America, Child Witches in

- Colonialism and Human Rights

- Colonization and Nationalism

- Color Symbolism and Child Development

- Common World Childhoods

- Competitiveness, Children and

- Conceptual Development in Early Childhood

- Congenital Disabilities

- Constructivist Approaches to Childhood

- Consumer Culture, Children and

- Consumption, Child and Teen

- Conversation Analysis and Research with Children

- Critical Approaches to Children’s Work and the Concept of ...

- Cultural psychology and human development

- Debt and Financialization of Childhood

- Discipline and Punishment

- Discrimination

- Disney, Walt

- Divorce And Custody

- Domestic Violence

- Drawings, Children’s

- Early Childhood

- Early Childhood Care and Education, Selected History of

- Eating disorders and obesity

- Education: Learning and Schooling Worldwide

- Environment, Children and the

- Environmental Education and Children

- Ethics in Research with Children

- Europe (including Greece and Rome), Child Sacrifice in

- Evolutionary Studies of Childhood

- Family Meals

- Fandom (Fan Studies)

- Female Genital Cutting

- Feminist New Materialist Approaches to Childhood Studies

- Feral and "Wild" Children

- Fetuses and Embryos

- Films about Children

- Films for Children

- Folk Tales, Fairy Tales and

- Foundlings and Abandoned Children

- Freud, Anna

- Freud, Sigmund

- Friends and Peers: Psychological Perspectives

- Froebel, Friedrich

- Gay and Lesbian Parents

- Gender and Childhood

- Generations, The Concept of

- Geographies, Children's

- Gifted and Talented Children

- Globalization

- Growing Up in the Digital Era

- Hall, G. Stanley

- Happiness in Children

- Hindu Views of Childhood and Child Rearing

- Hispanic Childhoods (U.S.)

- Historical Approaches to Child Witches

- History of Childhood in Canada

- HIV/AIDS, Growing Up with

- Homeschooling

- Humor and Laughter

- Images of Childhood, Adulthood, and Old Age in Children’s ...

- Infancy and Ethnography

- Infant Mortality in a Global Context

- Institutional Care

- Intercultural Learning and Teaching with Children

- Islamic Views of Childhood

- Japan, Childhood in

- Juvenile Detention in the US

- Klein, Melanie

- Labor, Child

- Latin America

- Learning, Language

- Learning to Write

- Legends, Contemporary

- Literary Representations of Childhood

- Literature, Children's

- Love and Care in the Early Years

- Magazines for Teenagers

- Maltreatment, Child

- Maria Montessori

- Marxism and Childhood

- Masculinities/Boyhood

- Material Cultures of Western Childhoods

- Mead, Margaret

- Media, Children in the

- Media Culture, Children's

- Medieval and Anglo-Saxon Childhoods

- Menstruation

- Middle Childhood

- Middle East

- Miscarriage

- Missionaries/Evangelism

- Moral Development

- Multi-culturalism and Education

- Music and Babies

- Nation and Childhood

- Native American and Aboriginal Canadian Childhood

- New Reproductive Technologies and Assisted Conception

- Nursery Rhymes

- Organizations, Nongovernmental

- Parental Gender Preferences, The Social Construction of

- Pediatrics, History of

- Peer Culture

- Perspectives on Boys' Circumcision

- Philosophy and Childhood

- Piaget, Jean

- Politics, Children and

- Postcolonial Childhoods

- Post-Modernism

- Poverty, Rights, and Well-being, Child

- Pre-Colombian Mesoamerica Childhoods

- Premodern China, Conceptions of Childhood in

- Prostitution and Pornography, Child

- Psychoanalysis

- Queer Theory and Childhood

- Race and Ethnicity

- Racism, Children and

- Radio, Children, and Young People

- Readers, Children as

- Refugee and Displaced Children

- Reimagining Early Childhood Education, Reconceptualizing a...

- Relational Ontologies

- Relational Pedagogies

- Rights, Children’s

- Risk and Resilience

- School Shootings

- Sex Education in the United States

- Social and Cultural Capital of Childhood

- Social Habitus in Childhood

- Social Movements, Children's

- Social Policy, Children and

- Socialization and Child Rearing

- Socio-cultural Perspectives on Children's Spirituality

- Sociology of Childhood

- South African Birth to Twenty Project

- South Asia, History of Childhood in

- Special Education

- Spiritual Development in Childhood and Adolescence

- Spock, Benjamin

- Sports and Organized Games

- Street Children

- Street Children And Brazil

- Subcultures

- Teenage Fathers

- Teenage Pregnancy

- The Bible and Children

- The Harms and Prevention of Drugs and Alcohol on Children

- The Spaces of Childhood

- Theater for Children and Young People

- Theories, Pedagogic

- Transgender Children

- Twins and Multiple Births

- Unaccompanied Migrant Children

- United Kingdom, History of Adoption and Fostering in the

- United States, Schooling in the

- Value of Children

- Views of Childhood, Jewish and Christian

- Violence, Children and

- Visual Representations of Childhood

- Voice, Participation, and Agency

- Vygotsky, Lev and His Cultural-historical Approach to Deve...

- Welfare Law in the United States, Child

- Well-Being, Child

- Western Europe and Scandinavia

- Witchcraft in the Contemporary World, Children and

- Work and Apprenticeship, Children's

- Young Carers

- Young Children and Inclusion

- Young Children’s Imagination

- Young Lives

- Young People, Alcohol, and Urban Life

- Young People and Climate Activism

- Young People and Disadvantaged Environments in Affluent Co...

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.194.105.172]

- 185.194.105.172

An Exploratory Study on Kidnapping as an Emerging Crime in Nigeria

- First Online: 27 August 2021

Cite this chapter

- Alaba M. Oludare 3 ,

- Ifeoma E. Okoye 4 &

- Lucy K. Tsado 5

371 Accesses

- The original version of this chapter was revised. The correction to this chapter can be found at https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-71024-8_18

This chapter traces the history of kidnapping as a precursor to the recent spike in violent crimes in Nigeria. The crime of kidnapping is not a new crime in human history. Many nations have experienced and dealt with this crime before the recent spike in Nigeria. The purpose of this chapter is to study the crime of kidnapping in Nigeria and other countries and to examine the responses and lessons learned that may be adopted for reducing kidnapping in Nigeria. Using the rational choice and strain theories as the criminological framework for understanding kidnapping in present-day Nigeria, the chapter explores the psychological aspects of the crime. This chapter also presents statistics from SBM Intel, a research and communications consulting firm that collects and analyses data to influence change in Africa. The chapter further sheds light into how Nigeria has been dealing with the crime of kidnapping and concludes with policy implications and recommendations.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Change history

04 november 2021.

The original chapter was inadvertently published with incorrect affiliation of one of the authors ‘Ifeoma E. Okoye’. The affiliation has been corrected in the chapter as below:

Adeoye, M. N. (2005). Terrorism: An appraisal in the Nigerian context. In Issues in Political Violence in Nigeria . Hamson Printing Communications.

Google Scholar

Africa piracy: Foreigners being held hostage. (2011, October 14). Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/piracy/8824953/Africa-piracy-foreigners-being-held-hostage.html

Agnew, R. (1985). A revised strain theory of delinquency. Social Forces, 64 , 151–167. https://doi.org/10.2307/2578977

Article Google Scholar

Agnew, R. (2006). Pressured into crime . Los Angeles: Roxbury Publishing Company.

Ahiuma-Young, V. (2018). Nigeria’s unemployment rate, a national threat—labour. Vanguard. https://www.vanguardngr.com/2018/01/nigerias-unemployment-rate-national-threat-labour/

Akinsulore, A. (2016). Kidnapping and its victims in Nigeria: A criminological assessment of the Ondo State criminal justice system. ABUAD Journal of Public and International Law, 2 , 180–209. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311202422_KIDNAPPING_AND_ITS_VICTIMS_IN_NIGERIA_A_CRIMINOLOGICAL_ASSESSMENT_OF_THE_ONDO_STATE_CRIMINAL_JUSTICE_SYSTEM

Akpan, N. (2010). Kidnapping in Nigeria’s Niger Delta: An exploratory study. Journal of Social Sciences, 24 (1), 33–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2010.11892834

Anazonwu, C. O., Onyemaechi, C. I., & Igwilo, C. (2016). Psychology of kidnapping. Practicum Psychologia, 6 (1) https://journals.aphriapub.com/index.php/PP/article/view/144

Arewa, J. A. (2011). Core national values as determinant of national security and panacea for the crime of kidnapping and abduction in Nigeria. Law and security in Nigeria, 1 , 127–139. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311202422_KIDNAPPING_AND_ITS_VICTIMS_IN_NIGERIA_A_CRIMINOLOGICAL_ASSESSMENT_OF_THE_ONDO_STATE_CRIMINAL_JUSTICE_SYSTEM

Augustyn et al. (n.d.). Kidnapping: Criminal offence. In Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/kidnapping

Bayagbon, M. (2013, February 18). Ansaru claims kidnap of 7 foreigners in Nigeria. Vanguard Newspaper. https://www.vanguardngr.com/2013/02/ansaru-claims-kidnap-of-7-foreigners-in-nigeria/

Bernard, T. J., Snipes, J. B., & Gerould, A. L. (2010). Vold’s theoretical criminology (6th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Black’s Law Dictionary. (2009). (9th ed.). West Publishing Co.

Blackstone, W. (2010). Commentaries on the Law of England (Forgotten Books), 955-956.

Bolaji, S. (2018, March 28). Dapchi girls’ abduction: Some unanswered questions. Punch. https://punchng.com/dapchi-girls-abduction-some-unanswered-questions/

Bolton, A. (2014, June 3). Prisoner swap blows up White House. The Hill. https://thehill.com/policy/defense/208163-prisoner-swap-blows-up-on-the-white-house

Callimachi, R. (2014). Paying ransoms, Europe bankrolls Qaeda terror. The New York Times.

Colucci, L. (2008). Crusading realism: The Bush doctrine and American core values after 9/11. University Press of America, passim.

Cornish, D., & Clarke, R. V. (1986). The reasoning criminal: Rational choice perspectives on offending . Berlin: Springer- Verlag .

Book Google Scholar

Country Watch. (n.d.). Nigeria. http://www.countrywatch.com.ezproxy.apollolibrary.com/cw_country.aspx?vcountry=12

Crenshaw, M. (1981). The causes of terrorism. Comparative Politics, 13 (4), 379–399. https://doi.org/10.2307/421717

Douglas, J. E., Burgess, A. W., Burgess, A. G., & Ressler, R. K. (1992). Crime classification manual: A standard system for investigation and classifying violent Crimes . New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Durkheim, E. (1951). Suicide . London: Routledge.

French hostage Marie Dedieu held in Somalia dies. (2011, October 19). BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-15365469

Fulani herdsmen kidnap delta monarch. (2018, June 5). PM News. https://www.pmnewsnigeria.com/2018/06/05/gunmen-kidnap-delta-monarch/

Global Terrorism Database. (2019). About the GTD. https://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/about/

Godwin, A. C. (2018, February 10). Fulani Herdsmen Strike again in Benue, Kidnap four Policemen. Daily Post. https://dailypost.ng/2018/02/10/fulani-herdsmen-strike-benue-kidnap-four-policemen/

Heaton, L. (2017, May 31). The Watson files. Foreign Policy News. https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/05/31/the-watson-files-somalia-climate-change-conflict-war/

International Crisis Group. (2014). Curbing violence in Nigeria (11): The Boko Haram insurgency. Crisis Group Africa Report, 216 (1–54) https://d2071andvip0wj.cloudfront.net/curbing-violence-in-nigeria-II-the-boko-haram-insurgency.pdf

Johnson, A. (2018). Fulani herdsman has made over N100 million from Edo abductions. Pulse.ng. https://www.pulse.ng/gist/business-man-fulani-herdsman-has-made-over-n100m-from-edo-abductions/gln8ewg

Kanogo, T. (2020). Abduction in modern Africa. Encyclopedia. https://www.encyclopedia.com/children/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/abduction-modern-africa

Khan, N. A., & Sajid, I. A. (2010). Kidnapping in the North West Frontier Province (NWFP). Pakistan Journal of Criminology, 2 (1), 175–187. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268821034_Kidnapping_in_The_North_West_Frontier_Province_NWFP

Kidnapping rate in Africa. (n.d.). The Global Economy. https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/kidnapping/Africa/

Kornbluh, P., & Byrne, M. (1993). The Iran-Contra scandal: The declassified history . New York: The New Press.

Kwaja, C. M. A. (2009). Strategies for rebuilding state capacity to manage ethnic and religious conflict in Nigeria. The Journal of Pan African Studies, 3 (3), 105–115. https://go.gale.com/ps/anonymous?id=GALE%7CA306598784&sid=googleScholar&v=2.1&it=r&linkaccess=abs&issn=08886601&p=LitRC&sw=w

Lynch, M. J., & Michalowski, R. (2010). Primer in radical criminology: Critical perspectives on crime, power & identity (4th ed.). Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers Inc.

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Kidnapping. In Merriam-Webster.com legal dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/legal/kidnapping

Merton, R. K. (1938). Social structure and anomie. American Sociological Review, 3 (5), 672–682. https://doi.org/10.2307/2084686

Meyer, J. (2017). Why the G8 pact to stop paying terrorist ransoms probably won't work—and isn't even such a great idea. Quartz. https://qz.com/95618/why-the-g8-pact-to-stop-paying-terrorist-ransoms-probably-wont-work-and-isnt-even-such-a-great-idea/

Mullin, G., & Petkar, S. (2018, August 9). Living hell: Journalist kidnapped and raped in Somalia details horrific 15-month ordeal and reason why she decided not to kill herself amid torture. The Sun. https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/6966500/journalist-amanda-lindhout-kidnapped-raped-somalia/

Neumann, P. R. (2007, January 1). Negotiating with terrorists. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2007-01-01/negotiating-terrorists

Ngwama, J. C. (2014). Kidnapping in Nigeria: An emerging social crime and the implications for the labor market. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 4 (1), 133–145.

Nigerian National Bureau of Statistics. (2010). Nigeria Poverty Profile, 2010. http://www.tucrivers.org/tucpublication/NigeriaPovertyProfile2010.pdf

Nnam, U. (2013). Kidnapping and kidnappers in the South Eastern States of Nigeria: A sociological analysis of selected inmates in Abakaliki and Umuahia prisons . A postgraduate seminar presented to the Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Ebonyi State University, Abakaliki, Ebonyi State, Nigeria.

Nwagwu, E. J. (2014). Unemployment and poverty in Nigeria: A link to national insecurity. Global Journal of Politics and Law Research, 2 (1), 19–35. https://rcmss.com/2013/1ijpamr/Unemployment%20and%20Poverty_%20Implications%20for%20National%20Security%20and%20Good%20Governance%20in%20Nigeria.pdf

Ochoa, R. (2012). Not just rich: New tendencies in kidnapping in Mexico City. Global Crime, 13 (1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/17440572.2011.632499

Odoemelam, U., & Omage, M. (2013). Changes in traditional cultural values and kidnapping: A case of Edo State. British Journal of Arts and Social Sciences, 16 (1), 1–4. https://www.academia.edu/29335485/Changes_in_traditional_cultural_values_and_kidnapping_The_case_of_Edo_State

Ogbuehi, V. N. (2018). Kidnapping in Nigeria: The way forward. Journal of Criminology and Forensic Studies, 1 (3), 1–8. https://chembiopublishers.com/JOCFS/JOCFS180014.pdf

Ogundiya, S., & Amzat, J. (2008). Nigeria and the threat of terrorism: Myth or reality. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 10 (2), 165–189. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266883526_NIGERIA_AND_THE_THREATS_OF_TERRORISM_MYTH_OR_REALITY

Okafor, A. E., Ajibo, H. T., Chukwu, N. A., Egbuche, M. N., & Asadu, N. (2018). Kidnapping and hostage-taking in Niger Delta Region of Nigeria: Implication for social work intervention with victims. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 8 (11), 94–100. https://doi.org/10.30845/ijhss.v8n11p11

Okengwu, K. (2011). Kidnapping in Nigeria: Issues and common sense ways of surviving. Global Journal of Education Research, 1 (1), 1–8. http://www.globalresearchjournals.org/journal/gjer/archive/july-2011-vol-1(1)/kidnapping-in-nigeria:-issues-and-common-sense-ways-of-surviving

Oludayo T., Usman A.O. & Adeyinka A. A. (2019). ‘I Went through Hell’: Strategies for Kidnapping and Victims’ Experiences in Nigeria, Journal of Aggression,Maltreatment & Trauma, https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2019.1628155

Pearl, M. (2015, January 27). Where exactly is the rule that says governments can’t negotiate with terrorists? Vice. https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/9bzp5v/where-exactly-is-the-rule-that-says-you-cant-negotiate-with-terrorists-998

Pharoah, R. (2005). Kidnapping for ransom in South Africa. South Africa Crime Quarterly, 14 , 23–28. https://doi.org/10.17159/2413-3108/2005/v0i14a1007

Powell, J. (2017). We must negotiate with terrorists: The dirty secret our government does not want to admit . Salon. https://www.salon.com/2015/07/12/we_must_negotiate_with_terrorists_the_dirty_secret_our_government_does_not_want_to_admit/

Rementeria, D. (1939). Criminal law-kidnapping-ransom and reward. Oregon Law Review, 19 , 301.

Salawu, B. (2010). Ethno-religious conflicts in Nigeria: Causal analysis and proposals for new management strategies. European Journal of Social Sciences, 13 (3), 345–353. https://gisf.ngo/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/0071-Salawu-2010-Nigeria-ethno-religious-conflict.pdf

SBM Intel. (2020, May). Nigeria’s kidnap problem: The economics of the kidnap industry in Nigeria. https://www.sbmintel.com/wpcontent/uploads/2020/05/202005_Nigeria-Kidnap.pdf

Schiller, D. T. (1985). The European experience. In Terrorism and personal protection (pp. 46-63). Butterworth.

Schmalleger, F. (2018). Criminology today: An integrative introduction (9th ed.). London: Pearson Education Inc..

Sergie, M. A., & Johnson, T. (2011). Boko Haram . Council on foreign relations. http://www.cfr.org/africa/boko-haram/p25739

Solomon, H. (2014). Nigeria’s Boko Haram: Beyond the rhetoric . Policy & Practice Brief Knowledge for Durable Peace. Accord.

Somalia: Shaabab displays four abducted Kenyans. (2012, January 13). Daily Nation. https://allafrica.com/stories/201201140015.html

South African Police Service. (2014). Crime Situation in South Africa. https://www.saps.gov.za/resource_centre/publications/statistics/crimestats/2014/crime_stats.php

Turner, M. (1998). Kidnapping and politics. International Journal of the Sociology of Law, 26 (2), 145–160. https://doi.org/10.1006/ijsl.1998.0061

Umar, H. (2014, April 21). Up to 233 teenage girls were kidnapped from this Nigerian school. Business insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/233-teenage-girls-kidnapped-from-chibok-nigeria-school-2014-4?IR=T

Umego, C. (2019). Offence of kidnapping: A counter to national security and development. SSRN. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3337745

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2015). International classification of crime for statistical purposes (ICCS)—Version 1.0.W.O. https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/statistics/crime/ICCS/ICCS_English_2016_web.pdf

Watch: Kidnappings on the rise in South Africa. (2019, November 20). https://www.enca.com/news/watch-kidnappings-rise-south-africa

Weber, B. (2014, July 8). Umaru Dikko, Ex-Nigerian official, who was almost kidnapped, dies. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/08/world/africa/umaru-dikko-ex-nigerian-official-who-was-almost-kidnapped-dies.html

Webster, M. (2007). Kidnapping: A brief psychological overview. In O. Nikbay. & S. Hancerli, (Eds.), Understanding and responding to the terrorism phenomenon: A multi-dimensional perspective (pp. 231-241). National Criminal Justice Reference Service. https://www.ncjrs.gov/App/Publications/abstract.aspx?ID=247116

Williams, F. P., & Mcshane, M. D. (2010). Criminological theory (5th ed.). London: Pearson Education Inc..

Wilson, C. (1994). Freedom at risk: The kidnapping of free Blacks in America, 1780–1865 . Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky.

Okashetu v. State . (2016). ALL FWLR (Pt.861) 1262 S.C.

R v. CORT . (2004). 4 All ER 137.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Criminal Justice, Mississippi Valley State University, Itta Bena, MS, USA

Alaba M. Oludare

Department of Criminal Justice, Virginia State University, VA, USA

Ifeoma E. Okoye

Department of Sociology, Social Work and Criminal Justice, Lamar University, Beaumont, TX, USA

Lucy K. Tsado

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Alaba M. Oludare .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Teaching Laboratory for Forensics and Criminology, Department of Social and Behavioural Sciences, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Heng Choon (Oliver) Chan

Department of Mental Health Nursing School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Ghana, Accra, Ghana

Samuel Adjorlolo

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Oludare, A.M., Okoye, I.E., Tsado, L.K. (2021). An Exploratory Study on Kidnapping as an Emerging Crime in Nigeria. In: Chan, H.C.(., Adjorlolo, S. (eds) Crime, Mental Health and the Criminal Justice System in Africa. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-71024-8_5

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-71024-8_5

Published : 27 August 2021

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-71023-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-71024-8

eBook Packages : Law and Criminology Law and Criminology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

KIDNAPPING: A SECURITY CHALLENGE IN NIGERIA

2018, Kingsley Emeka Ezemenaka

This article presents a relatively new dimension of kidnapping, known as ritual kidnapping, which has been battling security and polity in Nigeria. The concepts of ritual and ransom kidnapping are explored and analysed within this text through the adoption of a theoretical framework on security with qualitative methods to explain the causes of kidnapping and ritual kidnapping, an overview of security in Nigeria, and a discussion surrounding the challenges regarding implementation of security within Nigeria. Drawing from results acquired during this study, it can be argued that while the concept of security is yet to be agreed on internationally to suit the needs of different states, Nigeria should adopt a hybrid security in addressing issues such as ritual kidnapping and other crimes in the country.

Related Papers

oasis international journal

The concept of kidnapping and the worrisome challenges, effects and eventual consequences it portends to any growing economy like Nigeria and the world over has been a subject matter of serious concern to both policy makers, government, political leaders as well as all stakeholders interested in the socioeconomic advancement of any given nation. Most literature attributes its pervasiveness to unemployment, poverty, illiteracy and other problems besetting mankind. On this premise, we formed the basis for this study. Extant literature were consulted and overhauled all aimed at getting to a concise critique of this social scourge/malady. The researchers explored the subject matter as it concerns Nigeria where kidnapping has dramatically become an unavoidable source of livelihood/organized business to a lot of people particularly the teeming youth. The paper traced the root of kidnapping in Nigeria to the clamor for oil resource control by the aborigines of the oil producing Niger Delta region who resorted to hostage taking, hijacking and kidnapping of oil workers to challenge government's hegemonic control over oil resources. Robert K. Merton's Strain Theory was employed as a theoretical framework to interrogate how contradictions within Nigeria's social structure and cultural values create deviance. At the end, various recommendations were advanced to aid policy makers, the government and concerned institutions on possible ways of bringing this social problem to its minimal level, one of which is that government at all levels should formulate and effectively implement policies and strategies aimed at addressing the root causes of kidnapping such as poverty, unemployment, environmental degradation and political and economic marginalization.

Samuel Oyewole

This study interrogates the threat of kidnapping for ritual in Nigeria, a subject that has not received sufficient academic attention, and its socio-political and economic underpinnings have largely been overlooked in state responses. Relying on available public data, this article examines the phenomenon and its motivations and implications for security, and the efficacy of state responses, and possible ways forward.

IOSR Journals

This paper examined human life versus the culture of death: kidnapping, Boko Haram and Fulani Herdsmen and their activities in Nigeria. The negative effect of kidnapping and other associated vices is becoming unbearable not onlyto Nigerians but to the international community. This has led to a high level of fearwhich threatens the economic prosperity, political climate, business and general climate of the country. The study examined concepts of kidnapping, Boko Haram and Fulani herdsmen, their activities and incidents of attacks. The overall implication of the culture of death caused by the nefarious activities has led to a worsened market structure leading to loss of jobs, displacement of workers and loss of value for human lives. Recommendations were made on how this incidence of death could be tackled to improve the economic condition of the country and as well as value human lives. Some of the recommendations are that there should be an application of appropriate sanctions on every perpetrator of these evil acts, there should be fair and equal distribution of resources, there should be diversification of economy for creation of employment opportunities and that the youth should be equipped with appropriate skills and training for entrepreneurial development.

Abdulkabir olaiya Suleiman

Nigeria was globally declared as one of the horrible country to subsist in the world because of the widespread of corruption, injustice, violence and lack of security that exposed many innocent lives to end up in the hitch of kidnappers. This manuscript discovers that the rate of kidnapping in Nigeria was geometrically increased such that more than 2000 innocent people including Chibok girls, politicians, government officials, influential people and kings were reported to have been kidnapped between 2014 and 2017. While some of these victims were rescued after paying huge amount of money as ransom, some of them were able to escape after being tortured or raped and others were incarcerated to die of mysterious hunger. This research put forward that, kidnapping is the abduction or holding people hostage either to take ransom from the victim's family or as a sacrifice for ritual money or as an extenuative appeasement to win political appointment. As a result of perpetual injustice and corruption in Nigeria, kidnapping has now become the most lucrative business that can transform penniless to become rich in a blink of an eye. This paper concludes that the blight of kidnapping in Nigeria continue to aggravate due to the gravity of corruption and unemployment that rendered many skillful graduate to become jobless which drive them to desperately looking for a way to survive. The major objective of this study is to analyze the causes and the consequence of kidnapping in order to provide possible solution with scholastic scrutiny.

Ubong E Abraham

Abstract The main thrust of this study was to investigate the problem of kidnapping and its consequences on Nigerians in general and Uyo dwellers in particular. To achieve this objective, the study elicited data through questionnaire from 260 randomly selected respondents comprising of policemen/women from various departments at the state police headquarters, Ikot Akpan Abia, Uyo, in Akwa Ibom State, lawyers from the state judiciary headquarters as well as clergymen and members of the public in the aforementioned study area. Chi-square analytical tool was used to analyze elicited data at 0.05 level of significance. The result from the test of hypothesis one shows that there is a significant relationship between the recurring rates of kidnapping and the people’s culture. Test of hypothesis two shows that there is no correlation between kidnapping and the disposition of government. Test of hypothesis three shows that kidnapping is significantly dependent on the provisions of the Nigerian constitution; while result from hypothesis four shows that there is no significant relationship between kidnapping and political activities. Findings from the study shows that, the prevalence of kidnapping in Nigeria is as a result of laxity in the law implementation process to prosecute offenders. Consequent upon this findings it is suggested that the issue of ransom payment by victim’s families/relatives to kidnappers should be seriously condemned. Government also should endeavour to create employment for the teaming population of youths as this will assist to check the proliferation of the kidnapping. Keywords: Kidnapping, social problem, socio-economic development, Uyo metropolis

Nnadi E Ejiofor

Highlight:Cost of construction activities is increasing geometrically in Nigeria. This increase affects her economic growth as it deters the effective contribution of construction industry to the GDP of the country. Security situation in the country has prevented efficient operations within the industry. It results to high overhead cost and total cost increase. Moreso, out of the six geopolitical zones of the country, some are noticeably a security threat region, while construction activities are unhindered and less costly in other regions of the country. This necessitated the research work which thus revealed that security situations in different part of the country have a huge influence over the cost of construction works. Abstract: Issues on security challenges and safety are matters of grave concerns in Nigeria today. Presently, life has always been precarious in the country and the impact of this massive sense of insecurity on the human living especially in the construction industry cannot be overemphasized. The paper examines in a thematic form, the importance of security to the nation " s economic growth, overview of Nigeria construction industry and notable security crisis facing some geopolitical zones in Nigeria. The study identifies the effect of security challenges on the overall project cost in the four geopolitical zones in Nigeria using questionnaires, structural interview and case study as the research methods which were analyzed using descriptive method. Investigationconfirmed security porosity as a threat on the economic development of the affected areas and revealed effect of poor security on construction works.

Journal ijmr.net.in(UGC Approved)

The mass exodus of business men and women, cum traders, from the South Eastern part of Nigeria to other parts of the country and other parts of the world, in recent time, has become so worrisome. A people generally reputed for businesses (trading activities), have suddenly found their fortunes dwindling as a result of terror attacks on their persons and their businesses. Volume of trade is ultimately lowered. The nature of terrorism that takes place in this part of the country is kidnapping. It is not an overstatement that lives and businesses have been lost to kidnapping incidences in the recent past in South Eastern states of Nigeria. These states comprise Ebonyi, Enugu, Imo, Abia and Anambra. This study was therefore an attempt to ascertain how terrorism affects business development in South East Nigeria. Major area of focus of this study was to determine extent of relationship that exists between kidnapping and volume of trade in South East Nigeria. Extensively, literature was reviewed on the subject matter. The expo facto design research method was adopted. Correlation coefficient and regression analyses were employed to determine the type of relationship that exists between the two major variables: kidnapping and volume of trade. It

The Study is on the Social Contract existing between the people of Nigeria and it leader, in the person of President Muhammadu Buhari, which was entered into with effect from 2015, when he was elected the President of Nigeria. The objective of the study is to assess the extent to which President Muhammadu Buhari has fulfilled the promised he made to Nigerians in the area of fighting insecurity and corruption together with the revamping of the Nigeria's battered inherited economy. The objective was achieved through the analysis of secondary sources of data and other documentary evidences. Based on these, the study discovered that President Muhammadu Buhari inherited an almost failed state in all ramifications, to the extent to which he had to immediately and severely fight corruption and insurgency. The study then concluded that the President is succeeding in the fight against insurgency and corruption together with the revamping of the Nigerian economy. The study therefore recommended that the President and the government should intensify their fight against corruption and the other form of insecurity like kidnappings, farmers and herders clashes, banditry and cattle rustling.

Mohammed Salihu

RELATED PAPERS

Babangida Umar Aminu

Kemi Okenyodo

African Journal of Social Science and Humanities Research

Dr Temitope Francis Abiodun

ODEY CLARENCE ODEY

Israel Adoba

John Nwanegbo-Ben

Dr. Ernest J E B O L I S E CHUKWUKA

Shawkat Kamal

MUSTANG JOURNAL OF BUSINESS AND ETHICS

Ngboawaji Daniel Nte

Chizoro Okeke

Chijioke . K . Iwuamadi, Ph.D

Oromareghake Patrick

Studies in Conflict & Terrorism

Rodanthi Tzanelli

Besenyő János

Robert J Bunker

innocent chiluwa

Ibraheem O Muheeb

Kennedy Ogba

Sarwuan Daniel Shishima

Haidy Ahmed Tarek Ebrahim Abd Rabo

CleenFoundation Nigeria

Gungun chompa

International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science (IJRISS)

OBETA M UCHEJESO

Chioma Omenma - onyekachi

Inge Ligtvoet

Patricia A Maulden

Raissa Pereira

Viljar Veebel , Raul Markus

Emmanuel B Aduku

AZUBIKE ALEX

FEMI P R A I S E MOYIN

Idam Macben

Femi Akinleye

Manuela Tvaronavičienė

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University website

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Child Kidnapping in America

Jaycee Dugard was found in August, 2009 18 years after her abduction. While most child abductions by strangers do not end so well, historian Paula Fass points out that stranger abductions comprise only a small percentage of child kidnapping cases even though they receive the lion's share of media attention. Fear over stranger abductions has grown in the United States since the 19th century, and often results more from general fears about society than the actual safety of individual children.

It was a strange and haunting coincidence. Jaycee Dugard was rescued from the husband and wife who kidnapped her 18 years ago in California at virtually the same moment Elizabeth Smart confronted her kidnapper in a Utah courtroom. Once again, the nation was riveted by the phenomenon of child kidnapping. As historian Paula Fass describes, child abduction, and our reactions to it, have a long history in the United States. This month she puts kidnapping in historical perspective.

Readers may also be interested in these recent Origins articles, The Real Marriage Revolution and The Politics of International Adoption .

Across the United States this autumn, Americans watched intently the unfolding of two highly publicized cases of child abduction.

The kidnappers of Elizabeth Smart were at last brought to trial for their crimes after years of being declared mentally unfit. Fourteen years old at the time, Elizabeth had been taken from her bedroom in June 2002 and found nine months later held captive by a Utah couple; the husband styling himself a prophet of God.

More astonishingly, Jaycee Lee Dugard returned after eighteen years of captivity at the hands of a northern California couple who had abducted her as an 11 year old. Jaycee had two children during her confinement, and the case included many strange features that resulted from the fact that she had lived for so long with the man who had abducted and raped her and kept her as his daughter.

Over the past one hundred and forty years, Americans have experienced regular periods of intense public anxiety about child abduction. These episodes of alarm often have as much to do with how Americans perceive or characterize child abduction as with the actual number of such crimes. These perceptions influence what the public imagines is most dangerous to children in the society.

Although most citizens today are rarely aware of it, their own fears and responses to child kidnapping have been shaped over the years by a series of historical developments: especially the growth of modern media, changes in family patterns and expectations for parents, and structures of policing and law. When parents today express horror (and fascination) about the terrible ordeal of Jaycee Dugard, they are following a tradition that began in 1874.

When Charles Brewster Ross (known as Charley) was kidnapped on July 1, 1874, he was certainly not the first child to be kidnapped in the United States. But, unlike the others who preceded him, his parents were able to turn Charley's abduction into a national cause and to bring their plight and their son's story to national attention.

They did so because they were well connected politically, well-off economically, and because Charley's father's (Christian Ross), initially refused to pay the (then) enormous ransom demand of $20,000 (only in part because he did not have the money). This refusal brought him a torrent of negative commentary and helped to define for the future what Americans expected of parents caught in such terrible situations.

Christian Ross responded by writing a book in which he explained himself and described his personal anguish at the loss of his son and the toll it took on his family. The resulting publicity about the father's role and his obligations to his son helped to carry the story of the "lost boy" far and wide (and well beyond the United States) and made Charley Ross famous.

The publicity made his retrieval into a national obsession. To this day, Charley's fate remains unknown despite decades of efforts and the tantalizing revelations of one burglar moments before his death that he had been involved in the kidnapping and knew the boy's whereabouts.

All the attention on Charley's disappearance also raised a completely new awareness about the crime of child abduction and the inadequacy of laws to cope with it, and put a spotlight on the need for new forms of child protection.

The public revulsion/fascination at the threat to children's safety that characterized the Charley Ross case has been stoked and revitalized every time news of a new child abduction takes place.

Not all kidnappings are alike today, and very few children return after a long absence like Jaycee Dugard; nor were kidnappings all alike in the past. But certain patterns connect abductions over time.

Child kidnappings fall into three general types: 1) abductions by parents or family members; 2) stranger abductions by men for monetary ransom or physical exploitation and abuse; 3) children abducted by women who intend to keep and raise them as their own.

While the first kind is far and away the most common, it is the second kind of abduction—and the fear it generates—that have been most responsible for public hysteria, new public policies, and changes in parental approaches to childrearing.

Parental Abductions

By far, the most frequent form of kidnapping is abduction by a parent or family member. Today, over one quarter of a million such cases are reported annually to the authorities. Many of these are minor episodes—often misunderstandings or disagreements over custody, and they are short term.

But some parental abductions can last many years and cause enduring harm to the child (or children) and to the parents from whose care a child has been illegally removed. The most difficult cases of this kind concern children who are taken from the United States to foreign countries, where American laws, and even international agreements, are ineffective or difficult to enforce.

The number of parental abductions has grown enormously over the last thirty-five years as divorce and disputes over custody have increased in the United States and as the ease of transportation has made it possible to take children to distant places. Yet, abductions of this kind were already well known earlier in the twentieth century and even in the late nineteenth century.

In one such instance, in 1879, Henry and Belthiede Coolidge were found quarreling about their daughter on a street in Manhattan. Each parent held one arm of the child and was pulling her in opposite directions. This was the most public display of a quarrel that had been unfolding over time as each parent had previously abducted the girl from the other. The Coolidges were waiting for the final disposition of their divorce case in the courts; each hoped to be in possession of the child at that time and each accused the other of posing potential harms to the child's well being.

These accusations and actions would become well known to Americans by the end of the twentieth century as parental kidnappings (which often involve the help of other family members) have become a familiar feature of popular literature, television dramas, and abduction news and information.

Twenty years ago many of these abducted children appeared on Advo (advertising) cards delivered to millions of homes across the country, and on milk cartons. Today, they are featured on highway Amber Alerts.

Stranger Abduction

Despite the prevalence of this familial form of child abduction, what Americans fear most are "stranger abductions," by which they usually mean children abducted by male strangers.

Although this is what most Americans think of when they hear about kidnapping, it is a far less common form of child loss both today and historically. The subject has been so widely misrepresented and misunderstood that it is important first to focus on the real dimensions of the crime: to understand how it has come to represent "a parent's worst nightmare" and why the alarm is so disproportionate to the actual prevalence of the crime.

Today, children abducted by strangers represent a very small fraction of abductions—successful abductions affect between 100 and 150 children every year. This is hardly a trivial matter to those directly involved, but the perceived threat to children is far greater than the number of children affected. To understand this requires that we return to that first widely publicized stranger abduction in 1874.

The case of Charley Ross demonstrated the public's rising expectations about parental responsibilities for maintaining the safety of their children. It also exposed the very real limits of police actions in cases of this kind. This intersection between private and public responsibilities for children's welfare set the boundaries and context for kidnappings ever since.

The case also showed the growing dependence of parents of victims on the media to broadcast their loss in hopes of having the child located and returned. The Ross family was the first to widely distribute very large numbers of missing child posters (now familiar to Americans). Some of these were distributed by the circus impresario P. T. Barnum.

The Rosses were also able to use the Western Union Telegraph Company to follow leads from many places that came in as the public reported sightings of Charley (now recognized from posters as well as widely disseminated newspaper stories) in various parts of the country. Within short order, Charley Ross's name, identity, and story became deeply part of the public's imagination and inscribed in the popular culture of the time.

Christian Ross, like many parents of victims today, devoted the remainder of his life to finding his son and other missing children. The Charley Ross case was also used everywhere to change laws and increase penalties for child abduction.

The case anticipated and set the pattern for later experiences of child abductions as children's parents turned to all means to try to retrieve their children. In the process, the public became aware of and alarmed by the potential harm to their children.

Today, parents of kidnap victims remain dependent on publicity along with police cooperation. They and the public continue to seek new and more effective laws to protect children. At the same time, the frantic search for remedies, and the wide media fascination for these cases, has helped to inflame the public's sense of the dangers to children. Parents feel an acute sense of their own helplessness to deal with the crime that has come to represent one of the central anxieties of modern parenting.

An excellent illustration of these dilemmas is the hysteria that resulted in 1932 when the young son of American aviator Charles Lindbergh was kidnapped from his home in New Jersey.

Despite the active intervention of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (newly refashioned in response to the crime), which spearheaded the international hunt for the child, the full-time attention of the New Jersey state police, as well as private efforts by Lindbergh, no one was able successfully to locate Charles Augustus Lindbergh, Jr. alive. His body was subsequently found not far from the Lindbergh home. It took years before the police tracked down his kidnapper.

Lindbergh was beloved as a national hero after his solo flight across the Atlantic in 1927. As an international celebrity, he was seen in larger than life terms, but despite his fame and renown he was able neither to protect his son from kidnappers nor to retrieve him alive, even after he paid the $50,000 ransom.

That case confirmed the difficulties that parents seemed to face and, like the Charley Ross affair before it, the Lindbergh case led to reinvigorated attempts to change laws and institutions in response. In this instance, the federal government enacted the first national kidnap statute (the Lindbergh Law) quickly after the abduction. That law was meant to punish perpetrators to the maximum degree by declaring such crimes to be capital offenses, and its violators subject to the death penalty.

When child abduction once again came to national attention as a painful and threatening problem in the late 1970s and 1980s, it came with a similar sense of the inadequacy of law and law enforcement, the helpless grief of parents, and the public's fascination with the crime. It could also draw on the ubiquitous presence of television news in American homes.

And it came with a new and horrifying twist. Fears of sexual abuse and sadistic impulses—not ransom demands—now came to define the nature of the crime and the terror that parents experienced in contemplating the harms threatening their children.

The sexual abuse of child kidnap victims had always lurked as a possibility. This was the case, for example, when Bobby Franks' body was discovered in 1924 and Nathan Leopold, Jr. and Richard Loeb were accused of disfiguring him with acid. But Americans had usually understood this possibility as a danger that was secondary to the ransom that motivated these crimes in the first place.

By the 1950s, however, Americans began to change how they perceived the motives for child abduction. Ransom as a motive for kidnapping receded as sexual abuse and rape became more public and familiar themes in society.

The threat of abduction became even more powerful. It was now a crime to be feared by the vast majority of parents, not just those who were likely to be targeted because of their wealth. Once sexual violation or other sadistic practices, which likely led to the victims' deaths, were seen as motives for child disappearance, all parents became vulnerable because all children could be victims of such crimes.

This is exactly what happened in the late 1970s and 1980s when Americans experienced a great panic in regard to child kidnapping. Fears about the sexual abuse of children—both real and perceived—grew sharply in the turbulent context of the more liberated sexual behaviors following the 1960s, the widespread employment outside the home of married women with children during the 1970s, and the greater openness and discussion of homosexuality at the time.

By the 1980s, as a result of the publicity surrounding a series of kidnappings of young boys—Adam Walsh, Etan Patz, Kevin White, and Jacob Wetterling; children who lived in all parts of the country and in communities large and small—Americans began to register intense fears about child abductions as sexual crimes.

During this period, parents of victims created foundations to commemorate the victims and to assist in finding other children and brought the subject to the attention of national authorities, including congressional panels. They helped to stimulate the passage of laws that authorized new FBI oversight and provided funding for a new agency, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children .

The subject also became central and dominant in public discussions about policing and public responsibilities, as well as in private conversations among parents, in schools, and in community forums.

In order to bring maximum attention to the subject, individuals and victims' organizations often publicized the prevalence of the crime by combining numbers for all missing children, including those taken by parents and those who had run away. At various points in the 1980s, Americans were led to believe that as many as a million children a year were missing and presumed to be the subjects of stranger abductions.

These statistics increased the sense of urgency and inflamed the dread of parents, children, and others concerned with child safety. By the 1990s, careful analysis by the Justice Department distinguished among these dangers to children, emphasizing the much smaller number of stranger abductions.

By then, however, child abduction had become a fixture of popular culture as posters, Advo cards, billboards, movies, books and magazine articles, television programs, and various other forms of media attention had made child abduction and fears about "Stranger Danger" into a national obsession. The ordeal of Elizabeth Smart, for example, quickly became a book, a made-for-TV movie, and fodder for multiple magazine covers.

The fears rapidly altered child rearing patterns. By the 1990s, parents began to register their distrust of institutions that had developed to supplement the parental supervision of children—such as teachers at child care centers, baby sitters, sports coaches, Boy Scout leaders, and even Santa Claus—as the panic about child sexual abuse spread. Increasingly, whenever they could do so, parents kept their children under tight supervision, walking or driving them to school, and restricting a once more casual attitude toward informal play.

Kidnapping was the most extreme of the many dangers that parents feared. As the sexual abuse of children seemed to have become rampant, or at least as its social existence became more generally acknowledged, child kidnapping became a symbolic expression of these concerns and a growing distrust of strangers.

States and communities throughout the country instituted new laws in response. Named after seven-year-old Megan Kanka, raped and killed by a neighbor who lured her into his house to play with his puppy, Megan's Laws became part of the repertoire of police departments and community vigilance. These laws required sexual offenders to be listed on registries available to everyone in the community.

Other new laws targeted "pedophiles" (adults sexually interested in children) who were now assumed (rightly or wrongly) to be responsible for almost all stranger kidnappings. These included limits on where those convicted of sexual offenses against children could live, the institution of longer prison sentences, supervision with electronic devices, and institutionalization even after prison terms had been fully served. All of these were responses to the perception and evidence that pedophiles could not be reformed or cured.

When Jaycee Lee Dugard was found to be living quietly in a makeshift structure in the backyard of her abductors' house in Antioch, California in late August 2009, part of the public's outrage resulted from the fact that Phillip Garrido was a registered sex offender on federal parole.

Despite the many regulations and required registrations now in place, and the fact that he had lived in this house for years, Garrido's crime had gone undetected by any of the many policing agencies who could have discovered Jaycee's presence. Jaycee's return exposed once again how insecure American children appeared to be even in the most rigorous and seemingly stringent legal environments that now defined the landscape.

Women and Kidnapping

Another surprising and worrisome feature of the Jaycee Dugard case was that Jaycee had been abducted, hidden, and apparently abused with the compliance or active participation of Nancy Garrido, Phillip's wife. The same had been true for Elizabeth Smart.

But Americans should not be surprised that women can participate in child kidnappings. Throughout the twentieth century, women have been caught stealing children (usually infants) they hoped to raise as their own. Childless themselves, they are often eager to please their husbands or boyfriends and lead them to believe that they had themselves given birth to the child.

Clearly, the Dugard kidnapping departed from this pattern, but it does point up how our expectations regarding the motives for and perpetrators of kidnapping can frequently be upended. Women can and do kidnap children. This third type of kidnapping is rare, but it has occurred with regularity throughout the century.

It also refutes the assumption that women would not abuse or harm children. Even instances in which children are kidnapped by their mothers demonstrate that women can participate in a crime that can harm both children and their parents.

Child Abduction in America, Past and Present

Child kidnapping is deeply implicated in modern life and the complex nature of American experience. It has become an important feature of our culture in the widespread attention that it receives and in the haunting fears that it has created among parents and children.

It has also painfully affected the victims of a wide variety of child disappearances, those committed for ransom, children taken by parents or family members, and those carried out by strangers whose motives are varied and unpredictable.

Kidnappings have taken place in many places and times throughout history, and they are part of fairy tales and folk legends. How we respond to them reflects our beliefs about the value of children, the responsibilities of parents, the nature of sexuality, gender, and law.

Americans today are not only the inheritors of traditions and practices surrounding kidnapping that go back to the disappearance of Charley Ross in 1874, but also of a wider human propensity to worry about our children's safety.

Over time, our perception of the crime in the United States has changed as we have re-imagined its motives and the harms done to victims. The crimes too have changed as those seeking publicity have altered their own criminal behavior.

Parental kidnappings in particular have increased by leaps and bounds over the twentieth century.

But what has grown most greatly and inexorably in the past century and a half is our alarm and anxiety that our children are more vulnerable than they once were and our sense that parents must somehow protect and defend them ever more vigilantly against the lurking threats of modern life.

More from the Author

For more on the history of child abduction and the history of children in America by Paula Fass, see Kidnapped: A History of Child Abduction in the United States , (Oxford University Press, 1997), Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood in History and Society , (Thomson/Gale, 2004) and Children of a New World: Society, Culture, Globalization , (New York University Press, 2006)

Origins suggests:

What to do if Your Child Goes Missing: The First 24 Hours by freepeoplesearch.org

Best, Joel. Threatened Children: Rhetoric and Concern About Child Victims . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

Fass, Paula S. Kidnapped: Child Abduction in America . New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Fisher, Jim. The Lindbergh Case . New Brunswick, N. J.: Rutgers University Press, 1987.

Greif, Geoffrey L., and Rebecca L. Hegar, When Parents Kidnap: The Families Behind the Headlines . New York: Free Press, 1993.

Hoffman, Jan. “Why Can’t She Walk to School: An Issue that Distills the Anxieties at the Heart of Modern Parenting.” New York Times , Sunday Styles, September 13, 2009, pp. 1, 14.

Jenkins, Philip. Moral Panic: Changing Concepts of the Child Molester in Modern America . New Haven, Ct.: Yale University Press, 1998).

Lanning, Kenneth V. Child Molesters: A Behavioral Analysis . Arlington, Va.: National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, in cooperation with the FBI, 1992.

Ross, Christian K. The Father’s Story of Charles Ross, the Kidnapped Child Containing a Full and Complete Account of the Abduction of Charles Brewster Ross From the Home of His Parents in Germantown, with the Pursuit of the Abductors and Their Tragic Death; the Various Incidents Connected with the Search for the Lost Boy: The Discovery of Other Lost Children, Etc. Etc. With Facsimiles of Letters from the Abductors . Philadelphia: John E. Potter, 1876.

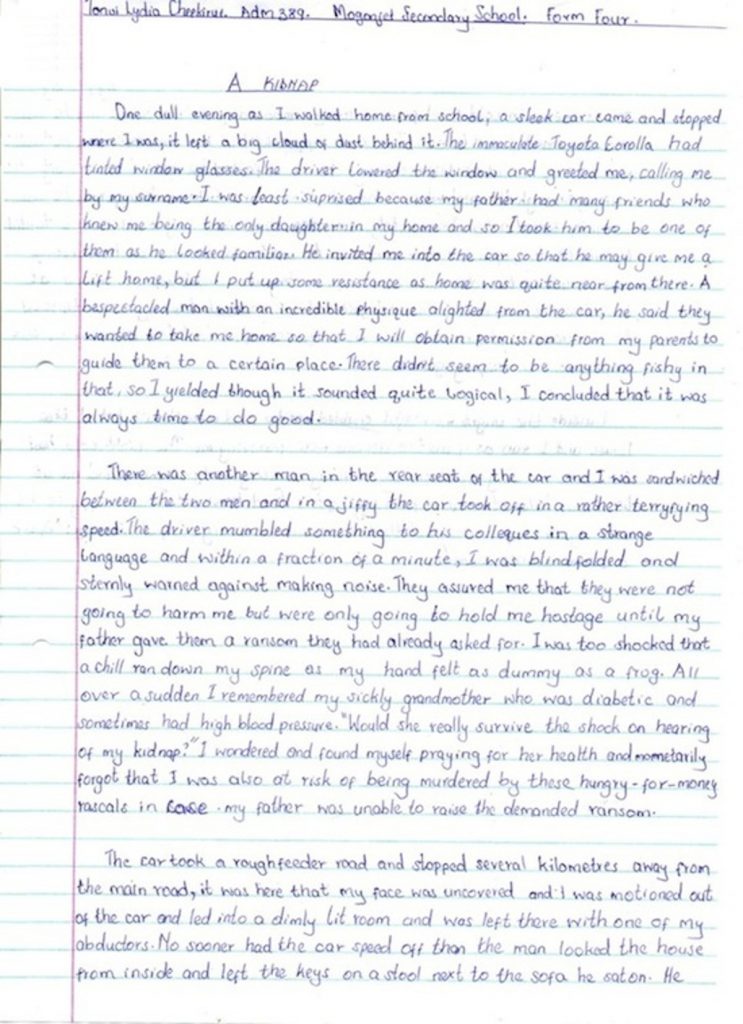

A Kidnap, by Lydia Chepkirui

Lift the Lid is proud to announce the winner of the 4th Annual Writing Competition at Mogonjet Secondary School in Kericho, Kenya. Lydia Chepkirui was chosen from six finalists for her personal essay “A Kidnap.”

Read her chilling true-life story.

An award of $100 was given to Lydia, $50 to benefit her class and $50 to help with school fees. We admire her bravery for revisiting the most frightening time of her life to write about when she was kidnapped and how she managed to escape. Her story is important to share, particularly how she became abducted by people she knew and how she kept a level head despite fearing for her life.

Congratulations Lydia on your noble and well-written essay!

If You Like This Story, Please Share!

Related posts.

How We Make Our World a Better Place – Mogonjet Secondary School – April 2024

7 More Scholarships, 7 More Smiles! – March 2024

*Progress Update* New Classroom Construction at Keneni Stars – March 2024

*Urgent* Lenana Girls Need Science Equipment by June – Mar 2024

Congratulations, Lydia! You are a talented writer, and clearly you put time and effort into your work. (I still get chills when I think of your experience.)

I hope to see more of your writing in the future!

Congratulations, Lydia! Your creativity is now turning your wealth. Make maximum use of the opportunity at hand. Hope to see you represent us all…. God be with you.

She is so creative and I will want to join in

Leave A Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

How to Write an Essay Introduction (with Examples)

The introduction of an essay plays a critical role in engaging the reader and providing contextual information about the topic. It sets the stage for the rest of the essay, establishes the tone and style, and motivates the reader to continue reading.

Table of Contents

What is an essay introduction , what to include in an essay introduction, how to create an essay structure , step-by-step process for writing an essay introduction , how to write an introduction paragraph , how to write a hook for your essay , how to include background information , how to write a thesis statement .

- Argumentative Essay Introduction Example:

- Expository Essay Introduction Example

Literary Analysis Essay Introduction Example

Check and revise – checklist for essay introduction , key takeaways , frequently asked questions .

An introduction is the opening section of an essay, paper, or other written work. It introduces the topic and provides background information, context, and an overview of what the reader can expect from the rest of the work. 1 The key is to be concise and to the point, providing enough information to engage the reader without delving into excessive detail.

The essay introduction is crucial as it sets the tone for the entire piece and provides the reader with a roadmap of what to expect. Here are key elements to include in your essay introduction:

- Hook : Start with an attention-grabbing statement or question to engage the reader. This could be a surprising fact, a relevant quote, or a compelling anecdote.

- Background information : Provide context and background information to help the reader understand the topic. This can include historical information, definitions of key terms, or an overview of the current state of affairs related to your topic.

- Thesis statement : Clearly state your main argument or position on the topic. Your thesis should be concise and specific, providing a clear direction for your essay.

Before we get into how to write an essay introduction, we need to know how it is structured. The structure of an essay is crucial for organizing your thoughts and presenting them clearly and logically. It is divided as follows: 2

- Introduction: The introduction should grab the reader’s attention with a hook, provide context, and include a thesis statement that presents the main argument or purpose of the essay.

- Body: The body should consist of focused paragraphs that support your thesis statement using evidence and analysis. Each paragraph should concentrate on a single central idea or argument and provide evidence, examples, or analysis to back it up.

- Conclusion: The conclusion should summarize the main points and restate the thesis differently. End with a final statement that leaves a lasting impression on the reader. Avoid new information or arguments.