- Find Vendors

- Learn CE/CME

Receive free bimonthly emails with the most popular healthcare simulation news & resources.

Get our newsletter.

I have read and agree to the HealthySimulation.com Privacy Policy & Terms of Use .

Reflecting on Reflective Thinking During Healthcare Simulation

Healthcare simulation , a form of experiential learning and debriefing , is a critical component of simulation-based learning ( INACSL , 2021; Nagle & Foli, 2021). Asking open-ended questions prompts learners to build on what they already know while exploring new content. This strategy helps learners synthesize new information, think critically about their performance, and identify knowledge gaps. Reflective open-ended questions help learners become more aware of how they acquire information and take more responsibility for their own education and training (Nagle & Foli, 2021). Clinical simulation is the perfect experiential learning tool for the development of reflective thinking and the simulated environment provides the required level of intentionality. This HealthySimulation.com further explains why reflective thinking is essential across medical simulation and provides insight into a useful framework.

In today’s world, simulation educators are busy being busy. They race through their day, bouncing from one activity or task to the next. Too often, they tell themselves that they are too busy to think; healthcare simulation educators just need to keep moving and keep doing. However, when they act without taking time to think about why they are doing what they are doing, clinical simulation educators tend to repeat similar actions in similar situations, eliciting similar results. If they want to produce different results, they need to spend time thinking about the why of their actions (Raelin, 2002). Healthcare simulation education needs to make time for reflective thinking.

Reflection is a metacognitive process that occurs before, during, and after situations, with the purpose of developing a greater understanding of both the self and the situation (Nagle & Foli, 2021). Reflection involves thinking about thinking, knowing what is and isn’t already known. When individuals reflect, they become aware of their thoughts, feelings, and actions and how they affect their behavior, as well as the behavior of those around them (Costa & Kallick, 2017).

Reflection also helps identify what is gained from an experience, making reflection a tool for self-improvement. Reflection is an active and dynamic process that keeps on developing and evolving as educators learn and respond to new experiences, situations, and information. Reflective thinking involves interpreting and evaluating experiences, deriving meaning from these experiences, and using them for problem-solving (Raelin, 2002).

One of the earliest theorists to consider learning through reflection was John Dewey, an American philosopher, and educational reformer. Dewey thought that reflection could be very useful in making sense of situations, particularly ones that are found difficult. Thinking about the experience, questioning why the situation occurred in a particular way, and considering ways healthcare simulation educators could change the outcome of the event produces learning.

The idea that individuals learn by doing (aka experiential learning) is only part of the story. If they stop there and do not spend time thinking about the decisions they made and the actions they took during the experience, they are leaving potential learning opportunities on the table, so to speak. “We do not learn from experience. We learn from reflecting on experience.” (Dewey, 1933, p.78).

Dewey realized the importance of reflection. The experience alone does not necessarily lead to learning; the experience is the reflection that makes sense of the experience for the individual, thereby making the experience meaningful. Each experience presents opportunities to build new knowledge, skills, and attitudes.

Reflecting on Reflection in Clinical Simulation

Reflection doesn’t just happen. Reflective thinking is a learned process that requires some degree of self-awareness and the ability to critically evaluate experiences, actions, and results. Reflection is about being conscious and aware of actions and their consequences. Reflection is personal and can be steeped in emotion. Critical reflection is one of the fundamental ways in which learners gain knowledge and improve. Practicing reflection helps learners develop a growth mindset (Coutts, 2021).

Experiential learning is a method of educating through first-hand experience, allowing skills and knowledge to be acquired outside of the traditional academic classroom setting. Learning is a process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience. The learning is enhanced if guided reflection is included as part of the experiential activity (Peterson & Kolb, 2017). Guided reflection is the facilitated intellectual and affective activities that allow individuals to explore their experiences in order to lead to new understanding and appreciation.

Guided reflection is a facilitated process that allows the learner to integrate the understanding gained from an experience, in order to enable better choices or actions in the future. Guided reflection reinforces the critical aspects of the experience and encourages insightful learning, allowing the participant to link theory with practice and research (Lioce et al., 2020).

Debriefing is a facilitated dialogue with peers and clinical educators following a healthcare simulation experience. This conversation is the most effective approach to foster deeper reflection, critical thinking, and clinical reasoning. The goal of the debriefing process is to assist in the development of insights, improve future performance, and promote the transfer and integration of learning into practice (INACSL Standards Committee, 2021).

Debriefing develops reflective thinking in participants. Reflective thinking is the self-monitoring that occurs during or after the healthcare simulation experience, assisting learners in identifying their knowledge gaps and the areas in which they need further improvement. Reflective thinking allows participants to make meaning out of the experience, identify questions generated by the experience, and ultimately, assimilate the knowledge, skills, and attitudes uncovered through the experience with pre-existing knowledge (Lioce et al., 2020).

While there are many frameworks for structuring a debriefing session, the STAND UP acronym focuses on promoting reflection during debriefing, regardless of the model being used:

S – Situation: Describe what happened during the experience; ensure everyone is on the same page T – Thoughts: Identify the thoughts, feelings, and reactions associated with the experience A – Analysis: Make sense of the experience and figure out its relevance N – Nonjudgmental Evaluation: Discuss what went well and what could be improved D – Determine Future Actions: Decide how this experience will inform future performance U – Understanding: Confirm and validate the learners’ takeaways from this experience P – Plan: Develop a plan for putting this learning into action

When healthcare simulation educators STAND UP for reflection, they are not leaving reflection to chance; they are planning for and monitoring learners’ opportunities for reflection. To STAND UP for reflection means they plan for times when learners will deliberately engage in the act of noticing how their thinking is evolving and the effect this has on their actions.

Learning is a result of reflecting on experience. Through reflection, they recognize the benefits of particular patterns of action and thought. By recognizing these patterns and the impact that they have on outcomes, clinical simulation educators equip themselves to incorporate the more effective patterns into future situations. They are also able to refine or abandon the patterns of action and thought that do not yield the desired outcomes.

Maximizing the Benefits of Reflection During Debriefing

During debriefing, facilitators guide learners to reflect upon their simulation actions and experiences. This guided reflection is essential in influencing student learning and clinical judgment development. With reflection, learners gain insights, leading to improved clinical judgment, critical thinking, and behavior changes. Antecedents necessary for reflection include a safe, supportive environment, previous knowledge, time, and trust between the facilitator, peers, and learner. Eight variables that impact the development of reflective thinking during debriefing include:

- Environment: Ensure the physical space is conducive for reflection. Minimize noise and distractions. Create calm spaces where individuals might be alone with their thoughts.

- Interactions: During debriefing, learners’ honest dialogue with peers and facilitator promotes sense-making, resulting in cognitive adjustments and perspective reframing. Creating a safe space for sharing of reflections is vital. Learners need to be able to engage in genuine reflection, sharing their misunderstandings, without fear of embarrassment or ridicule.

- Language: Learners benefit from learning a language that supports their reflective practice. This might be as simple as a set of questions the facilitator asks to guide the reflection.

- Modeling: Learners need to see their instructors engaging in reflective thinking. Make opportunities to join with students in reflective practice so they can see what it looks like for an experienced learner.

- Expectations: Be clear with expectations regarding reflection. Let learners know the time that will be allocated for reflection and the desired outcomes of the process.

- Opportunities: The same level of intentionality that goes into creating a healthcare simulation experience should be evident in the planning of reflection opportunities. When educators make reflection a routine part of healthcare simulation experiences, they promote the associated value. Scheduling time for reflection emphasizes the importance of this practice.

- Time: Reflection takes time. Learners need to see the value in spending time thinking about their actions. If educators don’t engage students in reflective thinking after a healthcare simulation experience, they are short-changing their learning.

- Learner-Centered: Attributes of learner-centered reflection are intentionally examining knowledge, skills, and attitudes; making sense of the medical simulation experience; thereby incorporating new information and behavior changes in future clinical situations. Consequences of learner-centered reflection include resolving knowledge gaps, correcting previous knowledge, developing a new understanding, and enhanced clinical judgment (Nagle & Foli, 2021).

Remember, reflection is a very personal experience. Facilitators should be mindful that the reflection that occurs during the debriefing session, can give learners an insight into their personality, and can reveal how they are feeling at a particular point in time. Exposure to these feelings can leave learners feeling vulnerable.

Reflective Thinking Leads to Reflective Practice

The reflection that occurs during the debriefing session is an example of Reflection-On-Action. Learners look back on the healthcare simulation experience to better understand the outcomes and how their thinking and actions contributed to those outcomes (Schön, 1983). Once learners gain proficiency at reflecting on action, the next step in their development as reflective thinkers is to reflect in action. Schön (1983) describes Reflection-In-Action as the ability to reflect on present experiences and activities to foresee how certain events or outcomes are happening, or are likely to happen.

This more advanced form of reflection allows those who engage in it to develop accountabilities and motivations for their actions and thinking. Costa & Kallick (2017) also acknowledged the need for reflection to span the entire learning experience. Instead of reflection being unidirectional, only looking back at an experience, reflection should be forward-facing, as well, considering possible outcomes of future actions based on prior experiences.

Reflective practitioner explores their actions and thinking before, during, and after an experience, considering the impact of their actions and thinking on themselves and others. Schön (1983) introduced the concept of the ‘‘reflective practitioner’’ as one who uses reflection as a tool for revisiting experience to learn from it and frame complex problems to better inform future performance.

Reflective capacity increases when individuals learn to reflect in action. Reflective capacity has been described as an essential characteristic of professionally competent clinical practice. In order to develop and maintain competence, learning effectively from experiences is vital. The fullest benefits of being a reflective practitioner are achieved when healthcare simulation educators plan for, notice, and reflect upon actions and then use the information gained to inform future choices (Coutts, 2021).

Experience plus reflection is the learning that lasts. If medical simulation educators genuinely value reflective thinking and want to produce reflective practitioners, they need to take a more proactive approach to develop the skill of reflection in learners. Instead of leaving reflection to chance, they need to build reflection into all learning experiences.

When simulation educators STAND UP for reflection and insist this critical component of the learning process be included in all healthcare simulation activities, learners will become more adept reflective thinkers. Learners will see the value of engaging in reflective thinking before, during, and after every learning experience. Reflection will be known as the glue that makes learning stick!

Learn How to Use the Reflective Pause in Clinical Simulation Debriefing to Maximize Learner Engagement

References:.

- Costa, A. L., & Kallick, B. (2017, April 25). Habits of mind: Strategies for disciplined choice making. The Systems Thinker. Retrieved August 27, 2022, from https://thesystemsthinker.com/habits-of-mind-strategies-for-disciplined-choice-making/

- Coutts, N. (2021, January 22). Taking a reflective stance. The Learner's Way. Retrieved August 20, 2022, from https://thelearnersway.net/ideas/2020/11/23/taking-a-reflective-stance

- Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. Boston, MA: D.C. Heath.

- INACSL Standards Committee, Decker, S., Alinier, G., Crawford, S.B., Gordon, R.M., & Wilson, C. (2021, September). Healthcare Simulation Standards of Best PracticeTM The Debriefing Process. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 58, 27-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2021.08.011 .

- Lioce, L. (Ed.), Lopreiato, J. (Founding Ed.), Downing, D., Chang, T.P., Robertson, J.M., Anderson, M., Diaz, D.A., and Spain, A.E. (Assoc. Eds.) and the Terminology and Concepts Working Group (2020). Healthcare Simulation Dictionary, 2nd edition. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Publication No. 20-0019. Nagle, A., & Foli, K. J. (2021). Student-centered reflection during debriefing. Nurse Educator, 47(4), 230–235. https://doi.org/10.1097/nne.0000000000001140

- Peterson, K., & Kolb, D. A. (2017). How you learn is how you live using nine ways of learning to Transform your life. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

- Raelin, J. A. (2002). "I don't have Time to think!" versus the art of reflective practice. Reflections: The SoL Journal, 4(1), 66–79. https://doi.org/10.1162/152417302320467571

- Ritchhart, R., & Church, M. (2020). Power of making thinking visible using routines to engage and empower learners. JOSSEY-BASS INC, U.S.

- Schön Donald A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

Jeanne Carey is the Director of Simulation at Baylor University Louise Herrington School of Nursing in Dallas, Texas. She holds advanced certification as a simulation educator and has 10 years of experience in all aspects of simulation, including the development and implementation of new simulation-based learning activities, training of simulation facilitators, and recruitment and management of standardized patients . Carey and the LHSON Simulation Team created the Two-Heads-Are-Better-Than-One (2HeadsR>1) strategy for role assignment in simulation. She is active in several simulation organizations and currently serves as an INACSL Nurse Planner.

5/21 @ 10AM PDT: Leveraging Sentinel U’s Virtual Simulations for Enhanced APRN Education 5/23 @ 10AM PDT: How to Map Healthcare Simulation Objectives to Program Outcomes 5/28 @ 10AM PDT: Behind the Scenes with Data: The Unsung Hero of Healthcare Simulation 5/29 @ 9AM PDT: Advantages of Using Digital Solutions for Effective Healthcare Simulation 6/5 @ 9AM PDT: How to Create Low-Cost Asynchronous Virtual Simulation for Graduate Level-Nursing Students 6/6 @ 10AM PDT: Unifying Healthcare Simulation Modalities: The PCS Cloud Experience 6/18 @ 10AM PDT: An Interprofessional, Experiential, Performance-based Model for Healthcare Professions

Prague’s SESAM 2024 To Move EU Clinical Simulation Community Forward

Dr. pam jeffries upcoming webinar on developing healthcare simulation centers to create realistic clinical scenarios.

Next week on May 15th, world renown nursing simulation expert Dr. Pamela R. Jeffries, PhD, RN, FAAN, ANEF, FSSH, Dean of Vanderbilt University School of Nursing, Co-Chair of GNSH, and author of several must-read healthcare simulation books will conduct a HealthySimulation.com CE webinar to focus on realism in healthcare simulation scenarios and building clinical simulation [...] 587 1 2 3 4 Featured Jobs BUSINESS & SIMULATION OPERATIONS SPECIALIST La Jolla, California

Manikins , AudioVisual Recording & Debriefing Systems , For Admins , About HealthySim

Advertise with us

Privacy Overview

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Reflective Responses Following a Role Play Simulation of Nurse Bullying

Deborah l. ulrich.

Wright State University, Dayton, OH, College of Nursing and Health, P: 937.775.2605, F: 937.775.4571

Gordon Lee Gillespie

University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, College of Nursing, P: 513.558.5236, F: 513.558.2142

Maura C. Boesch

Wright State University, Dayton, OH, College of Nursing and Health, P: 937.775.3607, F: 937.775.4571

Kyle M. Bateman

Union Memorial Hospital, Baltimore, MD, Cardiovascular Intensive Care Unit, P: 228.257.1702, F: 513.558.2142

Paula L. Grubb

CDC-National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Cincinnati, OH, Work Organization and Stress Research Team, P: 513.533.8179, F: 513.533.8596

The affective domain of learning can be used with role play simulation to develop professional values in nursing students. A qualitative exploratory design was used for this study to evaluate role play simulation as an active learning strategy. The context for the role play was bullying in nursing practice. Three hundred thirty-three senior nursing students from five college campuses participated. Following the role play simulation students completed a reflection worksheet. The worksheet data were qualitatively coded into themes. Thematic findings were personal responses during the simulation, nonverbal communications exhibited during the simulation, actions taken by participants during the simulation, and the perceived impact of bullying. Role play simulation was a highly effective pedagogy requiring no technology, was free, and elicited learning at both the cognitive and affective domains of learning.

Nurses are expected to adhere to the American Nurses Association ( ANA, 2015 ) Code of Ethics for Nurses and integrate ethical behaviors into their professional practice ( Fowler, 2008 ). An essential function for nurse educators is to instill these professional nursing values, morals, and ethics in students as the students develop and mature into professional nurses. Nurse educators can accomplish this education by designing learning opportunities that encompass the three categories or domains of learning commonly used in nursing academia: cognitive, psychomotor, and affective ( Shultz, 2009 ). The affective domain of learning is best suited for developing professional values and invokes feelings and emotions in students which is often difficult to teach as well as difficult to measure ( Brown, Holt-Macey, Martin, Skau, & Vogt, 2015 ; Cazzell & Howe, 2012 ; McArthur, Burch, Moore, & Hodges, 2015 ). Developing and evaluating active learning strategies incorporating the affective domain of learning are needed in nursing education to transform how nursing students are taught ( Valiga, 2014 ). The purpose of this study was to evaluate role play simulation as an active learning strategy to address the problem of bullying in nursing.

There is a growing body of literature describing teaching activities incorporating affective learning in nursing and/or interprofessional education (e.g., Cazzell & Howe, 2012 ; McArthur, Birch, Moore, & Hodges, 2015 ; Neville, Petro, Mitchell, & Brady, 2013 ; Rees, 2013 ). Neville et al. (2013) discussed undergraduate health science students observing an interprofessional healthcare team meeting and then reflecting and documenting their perceptions on the team member roles. McArthur et al. (2015) described an activity where undergraduate nursing students portrayed the life of a person with a physical disability with the aim of better understanding environmental limitations to live independently. While the body of literature is growing, there remains a dearth of published strategies focused to the affective domain of learning assessing student emotions, beliefs, attitudes, values, and moral behaviors.

Role play is an experiential learning strategy where learners take an active part in an imaginary scenario to provide targeted practice and receive feedback to enhance their skills all within a safe learning environment ( Wheeler & McNelis, 2014 ). The students figuratively place themselves in another person’s shoes so as to experience what that person is experiencing, while empathizing and understanding that person’s motivations ( McArthur et al., 2015 ). Role play provides the opportunity for students to explore the affective domain of emotions and values, although it also can provide cognitive learning as students analyze the situation they find themselves in as they experience the activity. The physical aspect of role play touches on the psychomotor domain, another domain of learning. Role play also provides a forum for students to make mistakes and try a variety of approaches to mitigate a difficult situation or problem. In this way, learners gain a repertoire of responses available for their future use when they encounter a similar situation ( Murphy, Yaruss, & Quesal, 2007 ). Debriefing after role play is a key to learning. Allowing students to discuss how they feel, why they respond as they do, how they might do something different the next time, and what they learned from the experience, the faculty member creates an interactive and inclusive environment where learning occurs. It helps students understand and accept their feelings and those of others as genuine and real, as well as develop competence in interacting in difficult circumstances.

An advantage to role play is simulating current practice problems with minimal requirement for technology leading to an inexpensive active learning strategy that can be implemented in multiple settings. A contemporary and pervasive problem for nurses in practice settings and students and faculty members in academic settings is bullying ( Berry, Gillespie, Gates, & Schafer, 2012 ; Clarke, Kane, Rajacich, & Lafreniere, 2012 ; Hutchinson, Wilkes, Jackson, & Vickers, 2010 ). Bullying can take a variety of forms from nonverbal intimidation such as ignoring or excluding a target to overt aggression ( Hutchinson, 2012 ). Given this pervasiveness, role play simulations developed to address bullying can educate students about this significant clinical problem, as well as facilitate discourse on ethical behaviors in response to bullying. In the current study, it was anticipated the student participants would experience affective domain of learning, identify strategies to address bullying professionally, and self-manage personal responses while adhering to the ANA’s Code of Ethics for Nurses.

A qualitative exploratory design was used for this study to evaluate role play simulation as an active learning strategy. The context for the role play was bullying in nursing practice. This study was by approved the Institutional Review Boards of three participating universities.

Setting and Sample

The research intervention took place at five college campuses from three universities in the Midwest United States. The sample was drawn from all senior level nursing students enrolled in a community health or leadership didactic course at one of the five college campuses.

Role Play Simulation

Three simulation scenarios were developed by faculty researchers. Each scenario was reviewed for content by expert faculty members, a graduate student, and an undergraduate student. After changes were made to the scenarios, the scenarios were pilot tested and further revised. The final version of the scenarios was used for this study.

At the start of the simulation, students were instructed on the learning outcome for the role play: examine the experience and outcomes of simulated bullying. Students were assigned to groups of four students per group. Students randomly drew a role card with instructions from an envelope: aggressor, target, nurse bystander, or patient. Aggressor and target role cards explained the simulation and provided instructions. The nurse bystander and patient role cards informed the students to act as they normally would once the simulation starts. Further, details about the role play instructions and simulation were previously reported (author information removed for anonymity). The role play simulation for all groups continued simultaneously for about five minutes and then was halted by the nursing faculty member.

Immediately following the role play, students completed an individual reflection worksheet developed by the researchers for use in this study. Questions on the worksheet included:

- What did it feel like to be in the role you played during the simulation?

- What nonverbal communication did you exhibit and see in others during the simulation?

- What actions were taken or attempted in order to resolve the issue?

- What impact to employees did the issue cause or may cause had the simulation been a real experience?

- What impact to patients did the issue cause or may cause had the simulation been a real experience?

Next, students reflected on the role play experience in their groups. Finally the faculty member facilitated a large group debriefing to explore their responses to the simulation and discuss professional mitigation strategies for future events in healthcare settings. The findings in this paper will focus on the individual self-reflection responses.

Faculty members teaching the role play simulation informed students that their role play worksheets would be used for research. Students declining their data to be used for research were instructed to write “Do Not Use” on the top of their worksheet. Worksheets were provided to the principal investigator and transcribed verbatim by a research assistant into a database.

Data Analysis

The data were independently reviewed by four researchers to determine important units of information based on naturalistic coding described by Lincoln and Guba (1985) . The research team then met to discuss their respective units of information and cluster the units of information into themes. Next, the data were independently analyzed and coded to themes. The team met to discuss their individual coding and came to consensus on the final thematic coding for each unit of information. The coded data then were extracted into Microsoft Word documents according to their respective themes and verified for accuracy and consistency by the research team.

Trustworthiness

The rigor or trustworthiness of the data was assured through the components of credibility, dependability, and confirmability ( Lincoln & Guba, 1985 ). Credibility was achieved by triangulating the data across participants and the research team coming to agreement on the themes and coding of units of information. Dependability was achieved by maintaining an audit trail documenting coding decisions made by the research team further increasing the consistency of data coding. Confirmability was achieved through investigator triangulation and an audit trail.

Reflection worksheets were received by 333 senior level nursing students portraying the roles of aggressor (n=91), target (n=83), nurse bystander (n=81), and patient (n=78). Themes were categorized according to personal responses during the simulation, nonverbal communications exhibited during the simulation, actions taken by participants during the simulation, and the perceived impact of bullying.

The personal responses simulated by the participants varied by student role (see Table 1 ). Students portraying the role of aggressor reported difficulty demonstrating bullying behaviors. They also reported having feelings of negative behavior and guilt. Students portraying the role of target most commonly reported feeling bullied, uncomfortable, or overwhelmed. Students portraying the role of the nurse bystander frequently felt helpless and unable to stop the bullying. Only 16 students intervened to stop the bullying. A high number of students portraying the role of patient reported feeling helpless and would likely lose trust in the healthcare team and/or feel neglected.

Students’ personal responses while simulating the roles of aggressor, target, nurse bystander, and patient.

Nonverbal communications were both exhibited and witnessed by the study participants (see Table 2 ). Nonverbal communications of students portraying the role of aggressors included aggressive arm gestures such as pointing fingers and flailing arms and facial communications such as rolling eyes and grimacing. Nonverbal communications of students portraying the role of targets included non-aggressive facial communications such as opening mouth in surprise and non-aggressive body posture such as leaning away from aggressor. Nonverbal communications of students portraying the role of nurse bystanders included non-aggressive facial communications and body posture such as backing away from the conflict. Nonverbal communications of students portraying the role of patients included both non-aggressive and aggressive facial communications.

Nonverbal communications exhibited and actions taken by students during the simulation as perceived by themselves and other students.

Actions taken by the study participants were categorized as proactive, passive, or aggressive (see Table 2 ). Aggressive actions were predominantly used by students portraying the role of aggressor. Examples include yelling and stating “Figure it out on your own.” Proactive actions were predominantly used by students portraying the roles of target and nurse bystanders. Examples include attempting compromise, suggesting that both parties take a break, and expressing their feelings. Passive actions were predominantly used by students portraying the role of patient. Examples include watching the incident transpire and doing nothing.

The perceived impact of bullying was assessed by the study participants (see Table 3 ). The perceived impact for employees resulting in adverse effects for following bullying incidents was the team/working environment, onset of negative emotions, and increased risk for legal consultation. Team/working environment impact was described as increased tension and conflict between employees and decreased morale and cohesion. Negative emotions included descriptors such as anxiety, fear, worry, anger, loss of confidence, disgruntlement, and confusion. Legal risk impact was described as loss of licensure, risk for malpractice claim, and employee discipline. The perceived impact to patients was negative organizational perception, personal emotions, and patient outcomes. Examples of negative organizational perceptions were loss of trust in care delivery and lack to return to that organization for future healthcare encounters. Examples of negative personal emotions for patients were feeling uncomfortable, afraid, confused, guilty, disrespected, neglected, and traumatized. Examples of negative patient outcomes were delays in care, poor patient care, lack of patient-centered care, and fragmented care.

Perceived impact of bullying in the workplace.

The role play activity evoked authentic affective responses from the participants, similar to research reported by McArthur et al. (2015) . The responses and perceived impact of the students playing the roles of target and nurse bystander were similar to those exhibited in real life bullying situations ( Berry et al., 2012 ; Reknes, Pallesen, Magerøy, Moen, Bjorvatn, & Einarsen, 2014 ; Vogelpohl, Rice, Edwards, & Bork, 2013 ). This alone points to the fact that role play can simulate real life to a great extent, allowing participants to actually feel the emotions and feelings they might experience should they encounter a similar situation in the future. Participants also exhibited verbal and nonverbal communications, as well as other physical actions of aggression and passivity in response to the role play. Body language, facial expressions, arm gestures, and other proactive, aggressive, and passive actions were noted by participants in the role play activity. Again, affective responses demonstrated that the participants were reacting in much the same manner as someone who would actually experience bullying. These responses and actions then can be leveraged during a critical debriefing facilitated by the nurse faculty member.

In order for role play to be effective in evoking similar responses to real life encounters, the faculty member needs to set the stage with a realistic and relevant scenario based in reality (Anonymous – reference blinded for peer review; McArthur et al., 2015 ). In this way, students can experience these stressful situations in a safe learning environment prior to experiencing them in nursing practice. This allows students to practice different ways of reacting and learning how to best deal with a professional practice issue.

Debriefing after role play is a major component of the role play activity and is seen by most to be more important than the role play scenario itself. Allowing students to discuss the situation they found themselves in, the way they responded and alternative responses for effective mitigation, and how others felt and responded will aide students to learn new ways to react, redirect, and hopefully halt bullying behaviors. Although debriefing is a huge part of the learning process, role play scenarios need to serve as the crux of the debriefing component. Role play must be realistic and relevant to practice if it is to evoke genuine feelings and emotions. Without a solid scenario for the role play, debriefing would not be as effective or lead to maximum learning. As evidenced by our findings, the role play simulation was realistic and evoked genuine feelings and emotions that were later leveraged in discussion/debriefing to plan professional mitigation strategies.

Role play also can address and lead to critical conversations about healthcare organizations. Students can relate the content of the scenario to their perceptions about how it could impact the organization and how a single bullying incident can spread quickly to affect the entire organization. In the bullying scenario, students reflected on the impact that bullying had for employees, patients, and the working environment of the healthcare team. They were able to grasp the enormity of the problem of bullying and see the problem from the viewpoints of all of the players: aggressors, targets, nurse bystanders, and patients. They noted the organizational impact, which expanded the learning and allowed the learners to see the cumulative impact of bullying.

Limitations

Three limitations were noted to this study. First, student knowledge about and experiences with bullying were not measured. This student background could have impacted student participation and engagement in the role play simulation and ultimately their affective responses documented on the reflection data collection tool. Second, fidelity to the implementation of the role play simulation was not measured by the research team. This limitation was minimized by the researchers providing 1:1 training to faculty members who implemented the simulation prior to deploying the intervention in the classroom. In addition, a detailed instructional guide was provided to faculty members to use during implementation to promote fidelity across classrooms. Third, the research was conducted with students who attended nursing schools in close geographic proximity, although the programs do enroll students who are not local to their campuses. This geography as well as the qualitative nature of the study design limit the generalizability of the study findings.

Implications for Nurse Educators

Bullying as a clinically significant practice problem recently garnered national attention when the ANA (2015) published the position statement “Incivility, Bullying, and Workplace Violence” which recognizes the magnitude and importance of bullying. Given the credence of bullying as a practice problem, education about bullying prevention and mitigation needs to be incorporated into nursing curricula. Role play simulations such as the one conducted in this study can serve as an effective strategy to deliver this course content.

As the costs associated with nursing education for books, tuition, and other fees continue to rise, the need for low cost or free educational activities becomes more important. The role play simulation discussed in this paper was conducted without costs to students or faculty members. More importantly, the desired student learning outcome to examine the experience and outcomes of simulated bullying was achieved with students describing a multitude of responses and actions reflecting their learning at the affective domain, an area often not addressed in nursing education.

The planned debriefing for this role play simulation could be extended to other professional behaviors and discussed in multiple courses. For example, students can discuss not only how to respond professionally to colleagues, but to patients and patients’ visitors demonstrating stress or agitation. Students in this study reported exhibiting behaviors deemed as aggressive including eye rolling, standing with their hands on their hips, and crossed arms. These gestures even if not intended to be aggressive were deemed as such. Therefore, students need to be educated as to how their nonverbal behaviors could manifest or be interpreted as aggression. Some students in this study who portrayed the role of targets were perceived as aggressive, likely a manifestation of their stress response to receiving bullying behaviors. These responses when witnessed by patients or visitors could lead to reduced patient satisfaction scores or an increase in patient complaints to healthcare administrators. Providing students multiple opportunities to practice their response and management to difficult situations using realistic scenarios related to current clinical problems and allowing a through debriefing can provide a mechanism for optimal student learning.

Role play simulation was a highly effective pedagogy requiring no technology, was free, and yet elicited learning at both the cognitive and affective domains of learning. Well written scenarios that are realistic and relevant to current nursing practice are excellent mechanisms to help students experience difficult issues and situations in safe supportive environments, while gaining new insights into best practices for handling difficult people, situations, and problems common to nursing practice. Future research is needed to evaluate students’ adoption and effective use of the education taught during this role play simulation.

Acknowledgments

This research study was funded by contract No. 200-2013-M-57090 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (CDC-NIOSH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the CDC-NIOSH.

Contributor Information

Deborah L. Ulrich, Wright State University, Dayton, OH, College of Nursing and Health, P: 937.775.2605, F: 937.775.4571.

Gordon Lee Gillespie, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, College of Nursing, P: 513.558.5236, F: 513.558.2142.

Maura C. Boesch, Wright State University, Dayton, OH, College of Nursing and Health, P: 937.775.3607, F: 937.775.4571.

Kyle M. Bateman, Union Memorial Hospital, Baltimore, MD, Cardiovascular Intensive Care Unit, P: 228.257.1702, F: 513.558.2142.

Paula L. Grubb, CDC-National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Cincinnati, OH, Work Organization and Stress Research Team, P: 513.533.8179, F: 513.533.8596.

- American Nurses Association. Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. Silver Spring, MD: Author; 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- Berry PA, Gillespie GL, Gates D, Schafer J. Novice nurse productivity following workplace bullying. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2012; 44 (1):80–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2011.01436.x. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown B, Holt-Macey S, Martin B, Skau K, Vogt EM. Developing the reflective practitioner: What, so what, now what. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning. 2015; 7 (5):705–715. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2015.06.014. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cazzell M, Howe C. Using objective structured clinical evaluation for simulation evaluation: Checklist considerations for interrater reliability. Clinical Simulation in Nursing. 2012; 8 (6):e219–e225. doi: 10.1016/j.ecns.2011.10.004. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Clarke CM, Kane, Rajacich DL, Lafreniere KD. Bullying in undergraduate clinical nursing education. Journal of Nursing Education. 2012; 51 (5):269–276. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20120409-01. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fowler M. Guide to the Code of Ethics for Nurses: Interpretation and Application. Silver Springs MD: American Nurses Association; 2008. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gillespie GL, Brown K, Grubb P, Shay A, Montoya K. Qualitative evaluation of a role play bullying simulation. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice. 2015; 5 (6):73–80. doi: 10.5430/jnep.v5n6p73. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hutchinson M. Bullying as workgroup manipulation: A model for understanding patterns of victimization and contagion within the workgroup. Journal of Nursing Management. 2012:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01390.x. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hutchinson M, Wilkes L, Jackson D, Vickers MH. Integrating individual, work group and organizational factors: Testing a multidimensional model of bullying in the nursing workplace. Journal of Nursing Management. 2010; 18 :173–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2009.01035.x. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications; 1985. [ Google Scholar ]

- Maier-Lorentz M. Writing objectives and evaluating learning in the affective domain. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development. 1999; 15 (4):167–171. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McArthur P, Burch L, Moore K, Hodges MS. Novel active learning experiences for students to identify barriers to independent living for people with disabilities. Rehabilitation Nursing. 2015 doi: 10.1002/rnj.208. in press. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Murphy W, Yaruss J, Quesal R. Enhancing treatment for school-age children who studder II. Reducing bullying through role-playing and self-disclosure. Journal of Fluency Disorders. 2007; 32 :139–162. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Neville CC, Petro R, Mitchell GK, Brady S. Team decision making: Design, implementation and evaluation of an interprofessional education activity for undergraduate health science students. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2013; 27 (6):523–525. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2013.784731. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rees KL. The role of reflective practices in enabling final year nursing students to respond to the distressing emotional challenges of nursing work. Nurse Education in Practice. 2013; 13 (1):48–52. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2012.07.003. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reknes I, Pallesen S, Magerøy N, Moen BE, Bjorvatn B, Einarsen S. Exposure to bullying behaviors as a predictor of mental health problems among Norwegian nurses: Results from the prospective SUSSH-survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2014; 51 (3):479–487. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.06.017. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schultz CM. Building a Science of Nursing Education: Foundation for Evidence-Based Teaching-Learning. New York, NY: National League of Nursing; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Valiga TM. Attending to affective domain learning: Essential to prepare the kind of graduates the public needs. Journal of Nursing Education. 2014; 53 (5):247. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20140422-10. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vogelpohl DA, Rice SK, Edwards ME, Bork CE. New graduate nurses’ perception of the workplace: Have they experienced bullying? Journal of Professional Nursing. 2013; 29 (6):414–422. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2012.10.008. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wheeler CA, McNelis AM. Nursing student perceptions of a community-based home visit experienced by a role-play simulation. Nursing Education Perspectives. 2014; 36 (4):259–261. doi: 10.5480/12-932.1. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Woods JH. Affective learning: One door to critical thinking. Holistic Nursing Practice. 1993; 7 (3):67–70. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zimmerman BJ, Phillips CY. Affective learning: Stimulus to critical thinking caring practice. Journal of Nursing Education. 2000; 39 (9):422–425. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

JavaScript must be enabled for this website to work

For instructions on how to enable JavaScript, please visit enable-javascript.com .

The Story-Reflection Cycle

How we combine the immersive power of story and the expansive power of reflection to teach students skills that stick

The narrative provides the conditions for learner motivation, agency, and choice.

Stories have the unique ability to harness our attention. In our simulations, we leverage interactive fiction to deliver a hyper immersive world, making learning compelling and personal. The story within the simulation reveals the key questions learners must grapple with.

Learners want to know what happens next because they live through compelling scenarios that carefully weave the learner into the narrative, making them a central and integral part of the fictional world. Within the story, the learner has control over what happens and gains a sense of agency as they make choices.

Progressing through branching narratives, learner choices lead them to different scenarios and, ultimately, to different endings. By immersing themselves in their roles and committing to their decisions, learners live through a narrative arc in which they are deeply invested.

Like the real world, information gathering in the simulation often comes in the form of interacting with interesting characters who challenge and surprise them. Throughout the simulation we embed messages from experts, characters who guide learners, and interactive videos that allow learners to speak to characters.

Players make a myriad of complicated business decisions through interaction.

To move learner focus from the intriguing details of the simulation to the larger underlying concepts we prompt learners to reflect on their actions both within the story and outside of the story. This reflective space gives learners the time to consider their decisions, broaden their perspective, and get back to the story with a richer, more holistic point of view.

Reflection prompts learners to take stock of the story and weave together the lessons of the simulation.

We ask learners to reflect . We embed narrative-driven reflection prompts throughout the simulation. For instance, in a team-based simulation, teams are asked to conduct an after action review and a coach character contacts individual players and asks them to review their decisions at inflection points in the simulation.

We ask learners to explain . The narrative design prompts learners to explain what they know to other characters and to themselves. The explanation allows learners to construct an accurate picture of what they know. For instance, in the BlueSky Ventures game, we deliberately set the learner up as a teacher, helping the main character to make investment recommendations. We do this because helping others helps the learner; by advising in-game characters the learner constructs and clarifies their own understanding.

We ask learners to think about the future . Characters in the game ask learners to consider the future within the game – what is the next best move given all the available information? The learner is asked to play out future scenarios before committing to a course of action, prompting them to think through possible ramifications of any decision and to reconstruct what they know. Outside of the game, the instructional design prompts players to apply what they learned through the simulation in a real-world context. Instructor debriefs connect player decisions within the course context to major concepts and real-world scenarios.

Want to learn more?

Use BlueSky Ventures with your class, a free, 90-minute business simulation, and see how we immerse students in the game while prompting them to learn new skills.

Try it yourself first! And then use our Discussion Guide to develop a rich debrief.

For more on the power of stories see: Willingham, D. T. (2021). Why don't students like school?: A cognitive scientist answers questions about how the mind works and what it means for the classroom . John Wiley & Sons.

For more on reflection and performance see: Di Stefano, G., Gino, F., Pisano, G. P., & Staats, B. R. (2016). Making experience count: The role of reflection in individual learning. Harvard Business School NOM Unit Working Paper , (14-093), 14-093.

For more on how we learn through explanation see: Lombrozo, T. (2006). The structure and function of explanations. Trends in cognitive sciences , 10 (10), 464-470.

You might also like

Creating distance to get close.

How to prompt students to shift focus so that they can learn from an experience

Editorial Team, Wharton Interactive

How to use simulations in your course

Simulations give students a chance to apply what they know in a place where failure is not critical…

Help | Advanced Search

Computer Science > Computation and Language

Title: self-reflection in llm agents: effects on problem-solving performance.

Abstract: In this study, we investigated the effects of self-reflection in large language models (LLMs) on problem-solving performance. We instructed nine popular LLMs to answer a series of multiple-choice questions to provide a performance baseline. For each incorrectly answered question, we instructed eight types of self-reflecting LLM agents to reflect on their mistakes and provide themselves with guidance to improve problem-solving. Then, using this guidance, each self-reflecting agent attempted to re-answer the same questions. Our results indicate that LLM agents are able to significantly improve their problem-solving performance through self-reflection ($p < 0.001$). In addition, we compared the various types of self-reflection to determine their individual contribution to performance. All code and data are available on GitHub at this https URL

Submission history

Access paper:.

- HTML (experimental)

- Other Formats

References & Citations

- Google Scholar

- Semantic Scholar

BibTeX formatted citation

Bibliographic and Citation Tools

Code, data and media associated with this article, recommenders and search tools.

- Institution

arXivLabs: experimental projects with community collaborators

arXivLabs is a framework that allows collaborators to develop and share new arXiv features directly on our website.

Both individuals and organizations that work with arXivLabs have embraced and accepted our values of openness, community, excellence, and user data privacy. arXiv is committed to these values and only works with partners that adhere to them.

Have an idea for a project that will add value for arXiv's community? Learn more about arXivLabs .

- About NEOMED Library

- About Our Collections

- Library Location & Hours

- Associated Hospital Libraries

- Copyright & Privacy Statements

- NEOMED University Homepage

COLLECTIONS BY FORMAT:

- Search for Journal Articles

- Search for Books, Journals & E-Books

- Library Databases & Clinical Tools

- Library Catalog

KEY RESOURCES:

- Cochrane Library

- NEOMED Bibliography Database

- More About Our Collections . . .

- Services for Students

- Services for Faculty & Staff

- Borrow, Renew & ILL

- Instruction & Curriculum Support

- Literature Search Services

- More Research Services . . .

- Study Spaces

- Printing & Copying

- 24-hour Silent Area

- Guides by Subject

- Course Guides

- Database Search Tips

- All Guides A-Z

- Logins for Students

- Logins for Faculty/Staff

- My Library Account

- Interlibrary Loan Account

- Off-Campus Access

- Library Login

- Get Full-Text Articles

- Reserve a Study Room

- Request an Article

- More FAQs . . .

- Library Home

- NEOMED Library

- Poverty Simulation Activity Guide

- COM Reflective Essay Assignment

- Instructions for the Session

- Supplemental Resources

- Information for Volunteers

Rubric for Reflective Essay

- Rubric for Reflective Essay Rubric adapted from: Brannon-Trottier G. Implementing the gateway framework for college readiness. Paper presented at: National Early College Conference; 2014 Dec 9-10; Dallas, TX. Rubric has been adapted a “Rubric for Student Reflections” handout. It was accessed on August 12, 2019, available here: http://earlycollegeconference.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Portfolio-Rubric-for-Reflection.PRINT_.pdf

Health Systems and Community I Students - Refective Essay Instructions

General Instructions:

Following the activity, students are to construct a 1-2-page typewritten reflective essay on their experience and the themes, issues, and/or dilemmas that arose due to the experience. The essay is to be reflective, meant to represent your personal feelings, insights, and supported opinions about the exercise as they relate to medicine and/or being a student-physician. These essays are not to be written as summaries of the simulation, the debrief discussion or the resources. If you are a student in the rural or urban pathway, you may focus aspects of your reflective essay around issues of poverty specific to those areas and/or populations.

Submit the completed essay via AIMS no later than 11:59 PM on the assigned due date corresponding with the assigned date of the Simulation (see chart below). Essays will be evaluated using the Reflection Rubric. More information on the rubric and the assignment can be found in the "Assignments" tab on AIMS. Students will receive narrative feedback in response to their submission, with a completed rubric attached.

Detailed Instructions:

The essay is to be reflective, meant to represent your personal feelings, insights, and supported opinions about the exercise as they relate to medicine and/or being a student-physician. These essays are not to be written as summaries of the simulation or the debrief discussion. The following questions may serve as a guide when reflecting upon your experience of the Poverty Simulation (students are not required to answer these questions) :

How did the exercise/activity resonate with you?

What surprised you about the behavior and decisions made during the simulation?

How did other people respond to your needs? How did you feel about their response?

Did your attitudes change during the month? If so, how?

What experiences have you had or witnessed related to the issues addressed during the exercise and/or discussion?

How will your approach to patients/families/patient care be shaped by these issues and experiences?

What insights or conclusions have you come to about the life experience of low-income families?

This exercise/activity is in no way able to cover all of the complexities of poverty in the United States. How might the experience of poverty vary, based culture, geographic location (urban, suburban, rural, medically underserved community, other country), time period, etc.?

What other factors intersect with poverty and why is it important for you to consider these as a future physician?

Pathway students may focus aspects of their reflective essay around issues of poverty specific to urban/rural areas and/or populations.

Essays must be submitted as a Word document or PDF via AIMS no later than 11:59 PM on the assigned due date corresponding with the assigned date of the Simulation (Students will receive written feedback.

All essays start with a score of 100%, a minimum score of 80% is required to pass. Students will receive narrative feedback with a completed rubric attached. Students receiving a Fail score will be required to resubmit within 48-hours. Please see rubric for more details.

- << Previous: Instructions for the Session

- Next: Supplemental Resources >>

- Last Updated: Jan 29, 2024 10:23 AM

- URL: https://libraryguides.neomed.edu/povertysimulation

Northeast Ohio Medical University is an Equal Education and Employment Institution ADA Compliance | Title IX

NEOMED Library - 4209 St, OH-44, Rootstown, OH 44272 - "A Building" Second Floor

330-325-6600

Except where otherwise noted, content on the NEOMED LibGuides is licensed for reuse under a Creative Commons 3.0 Attribution-NonCommercial license (CC BY-NC)

PROVIDE FEEDBACK

COLLECTIONS

LOCATION & HOURS

MAKE A FINANCIAL DONATION

OFF-CAMPUS ACCESS

HELP & GENERAL INFO

HOSPITAL LIBRARIES

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

Becoming a Co-Survivor—Reflections From the ICU

- 1 University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor

I will never forget the first time I saw someone die. The cacophony of code pagers halted morning signout on inpatient cardiology, and we sprinted to a patient in cardiac arrest. He did not survive. I trudged back to the team room, thinking of the family who just lost the most important person in their world. I never imagined I would be in their shoes later that year, witnessing the cardiac arrest of one of my most important people—my dad.

A few days after my dad had urgent cardiac surgery, I was at his bedside in the same hospital where I was completing my medical school clerkships. One moment, we were smiling and discussing which cake we would get to celebrate his discharge. Then everything changed. In an instant, my dad became wide-eyed and started gasping for air with an intensity and desperation I had never seen before. I called out to him, panic in my voice: “Dad, are you okay?!… Dad, can you hear me?!… Dad, please wake up!…,” all met by silence. His eyes remained still and the color drained from his face as I rubbed his sternum with my knuckles, then reached my fingers down to his wrist. He had no pulse.

Read More About

Burns CJ. Becoming a Co-Survivor—Reflections From the ICU. JAMA Cardiol. Published online May 15, 2024. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2024.1021

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Cardiology in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

UConn Today

- School and College News

- Arts & Culture

- Community Impact

- Entrepreneurship

- Health & Well-Being

- Research & Discovery

- UConn Health

- University Life

- UConn Voices

- University News

May 14, 2024 | Tiana Tran

A Reflection on Asian Culture

UConn Health Pharmacist Tiana Tran shares an essay for Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month

From left: UConn Health pharmacist Tiana Tran celebrates Tết with her sister, Viviana Tran, mother, Bachloan Phan, and father, Thoi Tran, February 2024. (Photo provided by Tiana Tran)

Growing up as a Vietnamese American, Vietnamese culture was perpetually ingrained into my home life. While both my sister and I were born in America, our parents made sure to include our culture in our childhoods. We were raised speaking Vietnamese and we spent quality time with our grandparents, which helped to solidify our language skills. We listened to Vietnamese music, played Vietnamese board games, and learned the history of our family. We enjoyed Vietnamese dishes nearly every day and celebrated Vietnamese traditions such as welcoming our departed ancestors home to eat dinner with us as well as colorful Lunar New Year festivities with family. As a result, my culture is very integral to my identity and I am proud of who I am.

Today, my family and I still perpetuate these traditions; just this February, my family got together and celebrated Tết, the Lunar New Year, in our own special way. I feel very grateful that my family and my culture are so present in my life.

A large part of my culture, and most East Asian, Southeast Asian, and South Asian cultures, revolves around community and family. In the spring, we celebrate Tết with our loved ones. We welcome the new year, full of new beginnings and good fortune, with our community. The celebrations are a chance for everyone to become closer and for communities to get together. It’s a chance for us to appreciate our roots, pay respects to our ancestors, and share well wishes for the new year with our loved ones.

With May’s arrival and spring in full bloom, I reflect upon the community I am a part of at UConn Health, and the immense pride I feel for working in and with a health system that truly cares for everyone. I am so incredibly grateful for the opportunities I have received that allowed me to contribute to the health care system as a pharmacist. This spring, I reflect on my identity and my culture, and how I am so proud of my heritage because it has made me the person I am today.

This May, I reflect on my roots, how my loved ones, my ancestors, and my culture have led me to where I am now. To everyone who has Asian or Pacific Islander heritage, I am so proud to see us represented at UConn Health, where we work together to cultivate a community of care in our health care system.

And to everyone in general, I invite you to do the same and reflect on your roots, and how they have led you to where you are today. Happy Asian American Heritage Month!

Tiana Tran, Pharm.D., is a 2022 graduate of the UConn School of Pharmacy. She completed her pharmacy residency at UConn Health a year later, and started as a staff pharmacist at UConn Health last August.

Recent Articles

May 17, 2024

UConn Health Marks Clinical Trials Day

Read the article

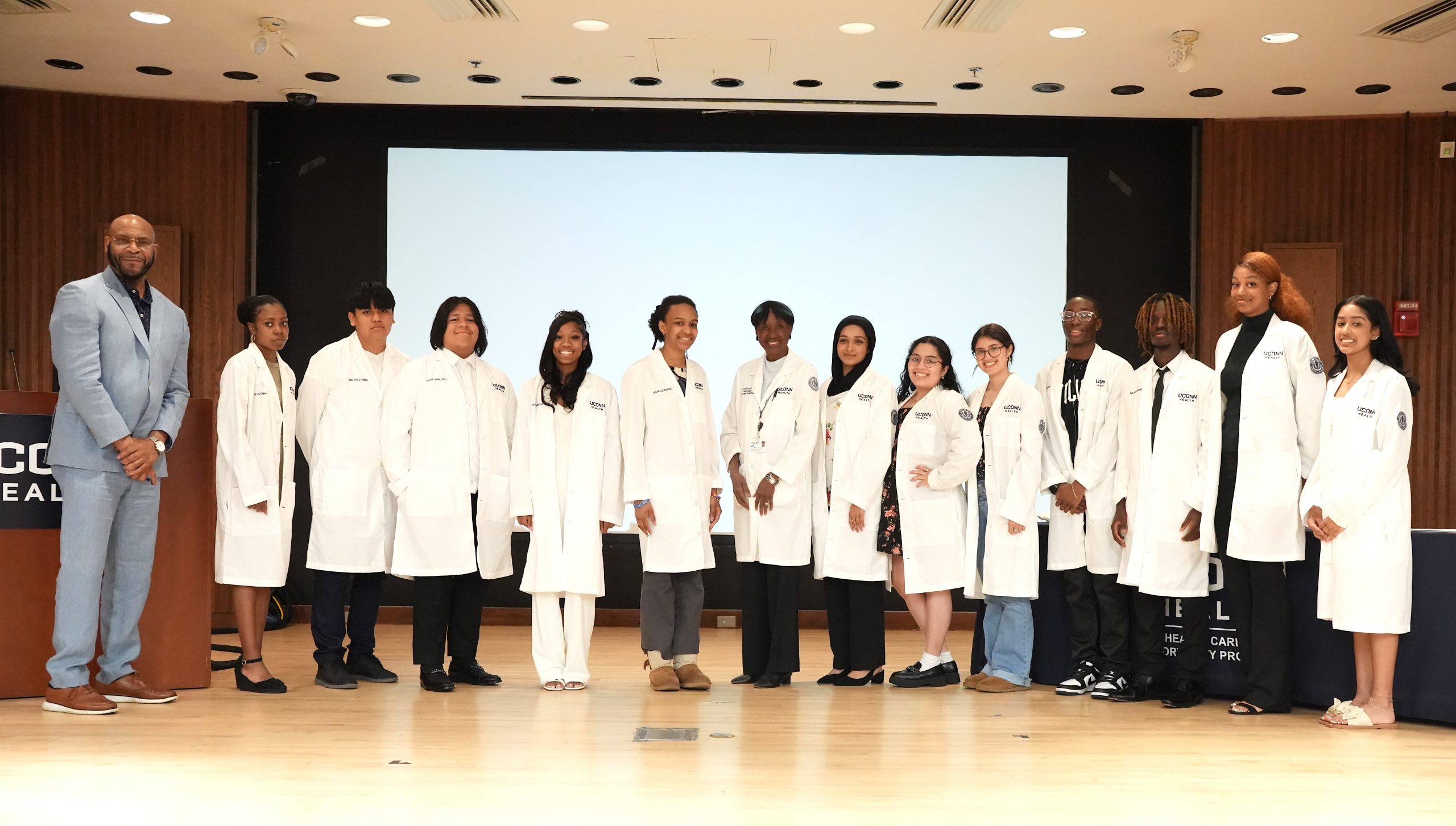

‘Doctors Academy’ at UConn Health Graduates High School Seniors

Generous Gift Provides Superior Quality Steinway Pianos for UConn’s Music Students

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

https://www.nist.gov/publications/flat-histogram-monte-carlo-simulation-water-adsorption-metal-organic-frameworks

Flat-histogram Monte Carlo Simulation of Water Adsorption in Metal-organic Frameworks

Download paper, additional citation formats.

- Google Scholar

If you have any questions about this publication or are having problems accessing it, please contact [email protected] .

- pop Culture

- Facebook Navigation Icon

- Twitter Navigation Icon

- WhatsApp icon

- Instagram Navigation Icon

- Youtube Navigation Icon

- Snapchat Navigation Icon

- TikTok Navigation Icon

- pigeons & planes

- newsletters

- Youtube logo nav bar 0 youtube

- Instagram Navigation Icon instagram

- Twitter Navigation Icon x

- Facebook logo facebook

- TikTok Navigation Icon tiktok

- Snapchat Navigation Icon snapchat

- Apple logo apple news

- Flipboard logo nav bar 1 flipboard

- Instagram Navigation Icon google news

- WhatsApp icon whatsapp

- RSS feed icon rss feed

Complex Global

- united states

- united kingdom

- netherlands

- philippines

- complex chinese

Work with us

terms of use

privacy policy

cookie settings

california privacy

public notice

accessibility statement

COMPLEX participates in various affiliate marketing programs, which means COMPLEX gets paid commissions on purchases made through our links to retailer sites. Our editorial content is not influenced by any commissions we receive.

© Complex Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Complex.com is a part of

Reporter Denies He Was Assaulted by Drake as Anonymous Claims Circulate

"I am not in the position to talk about [Drake's] character outside of our meetings, but I can say I was not violated in any way," Christopher Alvarez emphasized.

A freelancer reporter claims his reputation was ruined after he was dragged into a social media hellstorm amid Drake and Kendrick Lamar ’s feud.

Christopher Alvarez, a 26-year-old writer and recent graduate of Columbia Journalism School, penned a personal essay for Brooklyn Daily Eagle debunking his involvement as the alleged OVO mole and other malicious rumors about his association with the Canadian rapper.

It began when tweets from a user named EbonyPrince2k24 began threatening legal action against Drake on Friday, as reported by the Eagle . The anonymous individual allegedly had evidence of wrongdoing as well as items supposedly left by Drake at the Mark Hotel in New York City—including a laptop, medications with Drake’s legal name on them, as well as receipts and clothing.

#1. King @kendricklamar is not a liar, and I am not a thief! #2. Mr. Aubrey Graham ( @Drake ) & Mr. Livingston Allen ( @Akademiks ) have until noon Monday 5/13/24 to retract your claims of theft, or my attorney Ms. Adrienne Edward and I will exhaust every legal option available. pic.twitter.com/Mm6TBjMiXc — EbonyPrince2k24 (@EbonyPrince2k24) May 11, 2024

To Mr. Aubrey Graham ( @Drake ), may this photo help jog your memory as to where you discarded those items. The issue in the photo should also jog your memory. Jimmy Brooks would not have been proud of you that night... pic.twitter.com/QnPFsIERO7 — EbonyPrince2k24 (@EbonyPrince2k24) May 11, 2024

Among the items was a copy of Brooklyn Daily Eagle ’s May 8 edition. A photo of Alvarez, who lives with Thanatophoric Dysplasia Type 2, a rare skeletal disorder that requires him to use a wheelchair, was also shared from security footage of the lobby.

These tweets, along with other cryptic videos and allegations, quickly went viral on social media. It was later discovered that EbonyPrince may have been an employee of the Mark Hotel attempting to sell Drake’s unclaimed items from the hotel’s lost and found.

As the situation escalated, Alvarez continued to be wrongfully implicated online. Some users suggested that Drake may have been involved in some kind of altercation with the writer.

Alvarez told the Eagle that he’s interacted with all kinds of celebrities, including Drizzy himself, whom he has a photo with.

“I've had the privilege to be with Drake, Kendrick Lamar and other celebrities who have been very nice to me, but I don't understand where it all got blurred with the fans. I can confirm that I was with Drake on the night of Jan. 22, 2023. After his NYC concert with 21 Savage ,” Alvarez wrote in his essay for the publication. “I was called to meet Drizzy at The Mark Hotel, and we had a blast listening to new beats. I am not in the position to talk about his character outside of our meetings but I can say I was not violated in any way.”

“Growing up in a society that was not meant for me to succeed in, I would never put myself in a position that would further dehumanize the disability community,” Christopher added, citing CDC statistics that 80 percent of women and 30 percent of men with developmental disabilities have been sexually assaulted.

“Lastly, I have been getting a lot of spam phone calls, texts, emails and social media messages saying that I am the ‘snitch’ in this beef, that I accepted ‘hush money’ from Drake and that I was somehow in on the plan because I follow ‘underaged high school girls,’" Alvarez emphasized. "First, I don’t know anything about Drake and Lamar’s beef because to me life is too short to hate and I don’t follow it. Second, I’m a hard-working journalist who holds elected officials and private entities accountable; I don’t have rappers on speed dial to be ‘the mole’ or ‘snitch.’”

Read both the Brooklyn Daily Eagle 's full report and Alvarez's piece here .

SHARE THIS STORY

Complex Music Newsletter

Stay ready. The playlists, good reads and video interviews you need—delivered every week.

By entering your email and clicking Sign Up, you’re agreeing to let us send you customized marketing messages about us and our advertising partners. You are also agreeing to our

Latest in Music

| BY ALEX OCHO

Diddy Apologizes After 2016 Cassie Assault Video Surfaces: 'I Take Full Responsibility for My Actions'

| BY MARK ELIBERT

Kendall Jenner Spotted at Bad Bunny Show in Orlando

Slim Thug Apologizes to Cassie After Diddy Assault Video Surfaces: 'I Can't Stand Behind This'

50 Cent Celebrates Final Lap Tour Crossing $100 Million: 'You Can Do It Too'

Woman Dancing Behind JoJo Siwa and Mario Lopez Goes Viral

Joe Budden Addresses Criticism for Removing Diddy and Cassie Segment, Claims 'Absolutely No Ties' to Mogul

Mariah the Scientist Reveals Young Thug’s Thoughts on Drake and Kendrick’s Feud: ‘He F*cks with Everybody’

| BY JAELANI TURNER-WILLIAMS

Video of John Legend and Chrissy Teigen at Photo Booth Goes Viral

Lupe Fiasco Announces New Album 'Samurai,' Releases Video as Samurai Culture Regains Popularity

L.A. District Attorney’s Office: Diddy 2016 Assault Video 'Extremely Disturbing,' But Too Old to Prosecute

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Reflection is important for learning in simulation-based education (SBE). The importance of debriefing to promote reflection is accepted as a cornerstone of SBE. Gibbs's reflective cycle is a theoretical framework comprised of six stages and can be used during structured debriefing to guide reflection. The aim of the article was to provide an overview of Gibbs's reflective cycle and its ...

The Reflective Simulation Framework. The (RSF) which comprises six dimensions is an iterative learner centred model which can be used flexibly to explore the simulated experience in order to enhance learning and practice and crucially act as a basis for multiple feedback systems ... Paper No4, CH 5, 39-46. www.health.heacademy.ac.uk ...

In each simulation session, the case was presented first, followed by a demonstration of the manikin for the nursing staff, and then a short briefing. Each simulation lasted approximately 10-15 minutes, followed by 25-30 minutes of reflection during debriefing. Three teams of 12 nurses from the medical department participated.

Healthcare simulation education needs to make time for reflective thinking. Reflection is a metacognitive process that occurs before, during, and after situations, with the purpose of developing a greater understanding of both the self and the situation (Nagle & Foli, 2021). Reflection involves thinking about thinking, knowing what is and isn ...