Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 04 December 2020

- Correction 09 December 2020

How to write a superb literature review

Andy Tay is a freelance writer based in Singapore.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Credit: Getty

Literature reviews are important resources for scientists. They provide historical context for a field while offering opinions on its future trajectory. Creating them can provide inspiration for one’s own research, as well as some practice in writing. But few scientists are trained in how to write a review — or in what constitutes an excellent one. Even picking the appropriate software to use can be an involved decision (see ‘Tools and techniques’). So Nature asked editors and working scientists with well-cited reviews for their tips.

WENTING ZHAO: Be focused and avoid jargon

Assistant professor of chemical and biomedical engineering, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

When I was a research student, review writing improved my understanding of the history of my field. I also learnt about unmet challenges in the field that triggered ideas.

For example, while writing my first review 1 as a PhD student, I was frustrated by how poorly we understood how cells actively sense, interact with and adapt to nanoparticles used in drug delivery. This experience motivated me to study how the surface properties of nanoparticles can be modified to enhance biological sensing. When I transitioned to my postdoctoral research, this question led me to discover the role of cell-membrane curvature, which led to publications and my current research focus. I wouldn’t have started in this area without writing that review.

Collection: Careers toolkit

A common problem for students writing their first reviews is being overly ambitious. When I wrote mine, I imagined producing a comprehensive summary of every single type of nanomaterial used in biological applications. It ended up becoming a colossal piece of work, with too many papers discussed and without a clear way to categorize them. We published the work in the end, but decided to limit the discussion strictly to nanoparticles for biological sensing, rather than covering how different nanomaterials are used in biology.

My advice to students is to accept that a review is unlike a textbook: it should offer a more focused discussion, and it’s OK to skip some topics so that you do not distract your readers. Students should also consider editorial deadlines, especially for invited reviews: make sure that the review’s scope is not so extensive that it delays the writing.

A good review should also avoid jargon and explain the basic concepts for someone who is new to the field. Although I trained as an engineer, I’m interested in biology, and my research is about developing nanomaterials to manipulate proteins at the cell membrane and how this can affect ageing and cancer. As an ‘outsider’, the reviews that I find most useful for these biological topics are those that speak to me in accessible scientific language.

Bozhi Tian likes to get a variety of perspectives into a review. Credit: Aleksander Prominski

BOZHI TIAN: Have a process and develop your style

Associate professor of chemistry, University of Chicago, Illinois.

In my lab, we start by asking: what is the purpose of this review? My reasons for writing one can include the chance to contribute insights to the scientific community and identify opportunities for my research. I also see review writing as a way to train early-career researchers in soft skills such as project management and leadership. This is especially true for lead authors, because they will learn to work with their co-authors to integrate the various sections into a piece with smooth transitions and no overlaps.

After we have identified the need and purpose of a review article, I will form a team from the researchers in my lab. I try to include students with different areas of expertise, because it is useful to get a variety of perspectives. For example, in the review ‘An atlas of nano-enabled neural interfaces’ 2 , we had authors with backgrounds in biophysics, neuroengineering, neurobiology and materials sciences focusing on different sections of the review.

After this, I will discuss an outline with my team. We go through multiple iterations to make sure that we have scanned the literature sufficiently and do not repeat discussions that have appeared in other reviews. It is also important that the outline is not decided by me alone: students often have fresh ideas that they can bring to the table. Once this is done, we proceed with the writing.

I often remind my students to imagine themselves as ‘artists of science’ and encourage them to develop how they write and present information. Adding more words isn’t always the best way: for example, I enjoy using tables to summarize research progress and suggest future research trajectories. I’ve also considered including short videos in our review papers to highlight key aspects of the work. I think this can increase readership and accessibility because these videos can be easily shared on social-media platforms.

ANKITA ANIRBAN: Timeliness and figures make a huge difference

Editor, Nature Reviews Physics .

One of my roles as a journal editor is to evaluate proposals for reviews. The best proposals are timely and clearly explain why readers should pay attention to the proposed topic.

It is not enough for a review to be a summary of the latest growth in the literature: the most interesting reviews instead provide a discussion about disagreements in the field.

Careers Collection: Publishing

Scientists often centre the story of their primary research papers around their figures — but when it comes to reviews, figures often take a secondary role. In my opinion, review figures are more important than most people think. One of my favourite review-style articles 3 presents a plot bringing together data from multiple research papers (many of which directly contradict each other). This is then used to identify broad trends and suggest underlying mechanisms that could explain all of the different conclusions.

An important role of a review article is to introduce researchers to a field. For this, schematic figures can be useful to illustrate the science being discussed, in much the same way as the first slide of a talk should. That is why, at Nature Reviews, we have in-house illustrators to assist authors. However, simplicity is key, and even without support from professional illustrators, researchers can still make use of many free drawing tools to enhance the value of their review figures.

Yoojin Choi recommends that researchers be open to critiques when writing reviews. Credit: Yoojin Choi

YOOJIN CHOI: Stay updated and be open to suggestions

Research assistant professor, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, Daejeon.

I started writing the review ‘Biosynthesis of inorganic nanomaterials using microbial cells and bacteriophages’ 4 as a PhD student in 2018. It took me one year to write the first draft because I was working on the review alongside my PhD research and mostly on my own, with support from my adviser. It took a further year to complete the processes of peer review, revision and publication. During this time, many new papers and even competing reviews were published. To provide the most up-to-date and original review, I had to stay abreast of the literature. In my case, I made use of Google Scholar, which I set to send me daily updates of relevant literature based on key words.

Through my review-writing process, I also learnt to be more open to critiques to enhance the value and increase the readership of my work. Initially, my review was focused only on using microbial cells such as bacteria to produce nanomaterials, which was the subject of my PhD research. Bacteria such as these are known as biofactories: that is, organisms that produce biological material which can be modified to produce useful materials, such as magnetic nanoparticles for drug-delivery purposes.

Synchronized editing: the future of collaborative writing

However, when the first peer-review report came back, all three reviewers suggested expanding the review to cover another type of biofactory: bacteriophages. These are essentially viruses that infect bacteria, and they can also produce nanomaterials.

The feedback eventually led me to include a discussion of the differences between the various biofactories (bacteriophages, bacteria, fungi and microalgae) and their advantages and disadvantages. This turned out to be a great addition because it made the review more comprehensive.

Writing the review also led me to an idea about using nanomaterial-modified microorganisms to produce chemicals, which I’m still researching now.

PAULA MARTIN-GONZALEZ: Make good use of technology

PhD student, University of Cambridge, UK.

Just before the coronavirus lockdown, my PhD adviser and I decided to write a literature review discussing the integration of medical imaging with genomics to improve ovarian cancer management.

As I was researching the review, I noticed a trend in which some papers were consistently being cited by many other papers in the field. It was clear to me that those papers must be important, but as a new member of the field of integrated cancer biology, it was difficult to immediately find and read all of these ‘seminal papers’.

That was when I decided to code a small application to make my literature research more efficient. Using my code, users can enter a query, such as ‘ovarian cancer, computer tomography, radiomics’, and the application searches for all relevant literature archived in databases such as PubMed that feature these key words.

The code then identifies the relevant papers and creates a citation graph of all the references cited in the results of the search. The software highlights papers that have many citation relationships with other papers in the search, and could therefore be called seminal papers.

My code has substantially improved how I organize papers and has informed me of key publications and discoveries in my research field: something that would have taken more time and experience in the field otherwise. After I shared my code on GitHub, I received feedback that it can be daunting for researchers who are not used to coding. Consequently, I am hoping to build a more user-friendly interface in a form of a web page, akin to PubMed or Google Scholar, where users can simply input their queries to generate citation graphs.

Tools and techniques

Most reference managers on the market offer similar capabilities when it comes to providing a Microsoft Word plug-in and producing different citation styles. But depending on your working preferences, some might be more suitable than others.

Reference managers

Attribute | EndNote | Mendeley | Zotero | Paperpile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Cost | A one-time cost of around US$340 but comes with discounts for academics; around $150 for students | Free version available | Free version available | Low and comes with academic discounts |

Level of user support | Extensive user tutorials available; dedicated help desk | Extensive user tutorials available; global network of 5,000 volunteers to advise users | Forum discussions to troubleshoot | Forum discussions to troubleshoot |

Desktop version available for offline use? | Available | Available | Available | Unavailable |

Document storage on cloud | Up to 2 GB (free version) | Up to 2 GB (free version) | Up to 300 MB (free version) | Storage linked to Google Drive |

Compatible with Google Docs? | No | No | Yes | Yes |

Supports collaborative working? | No group working | References can be shared or edited by a maximum of three other users (or more in the paid-for version) | No limit on the number of users | No limit on the number of users |

Here is a comparison of the more popular collaborative writing tools, but there are other options, including Fidus Writer, Manuscript.io, Authorea and Stencila.

Collaborative writing tools

Attribute | Manubot | Overleaf | Google Docs |

|---|---|---|---|

Cost | Free, open source | $15–30 per month, comes with academic discounts | Free, comes with a Google account |

Writing language | Type and write in Markdown* | Type and format in LaTex* | Standard word processor |

Can be used with a mobile device? | No | No | Yes |

References | Bibliographies are built using DOIs, circumventing reference managers | Citation styles can be imported from reference managers | Possible but requires additional referencing tools in a plug-in, such as Paperpile |

*Markdown and LaTex are code-based formatting languages favoured by physicists, mathematicians and computer scientists who code on a regular basis, and less popular in other disciplines such as biology and chemistry.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03422-x

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Updates & Corrections

Correction 09 December 2020 : An earlier version of the tables in this article included some incorrect details about the programs Zotero, Endnote and Manubot. These have now been corrected.

Hsing, I.-M., Xu, Y. & Zhao, W. Electroanalysis 19 , 755–768 (2007).

Article Google Scholar

Ledesma, H. A. et al. Nature Nanotechnol. 14 , 645–657 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Brahlek, M., Koirala, N., Bansal, N. & Oh, S. Solid State Commun. 215–216 , 54–62 (2015).

Choi, Y. & Lee, S. Y. Nature Rev. Chem . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-020-00221-w (2020).

Download references

Related Articles

- Research management

Why I’ve removed journal titles from the papers on my CV

Career Column 09 AUG 24

Why we quit: how ‘toxic management’ and pandemic pressures fuelled disillusionment in higher education

Career News 08 AUG 24

Scientists are falling victim to deepfake AI video scams — here’s how to fight back

Career Feature 07 AUG 24

Our local research project put us on the global stage — here’s how you can do it, too

Comment 06 AUG 24

Hybrid conferences should be the norm — optimize them so everyone benefits

Editorial 06 AUG 24

How a space physicist is shaking up China’s research funding

News Q&A 02 AUG 24

The UK launched a metascience unit. Will other countries follow suit?

Nature Index 07 AUG 24

Professor/Associate Professor/Assistant Professor/Senior Lecturer/Lecturer

The School of Science and Engineering (SSE) at The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen (CUHK-Shenzhen) sincerely invites applications for mul...

Shenzhen, China

The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen (CUHK Shenzhen)

Postdoctoral Fellowships at West China Hospital/West China School of Medicine of Sichuan University

Open to PhD students, PhD, Post-Doc and residents.

Chengdu, Sichuan, China

West China School of Medicine/West China Hospital

Welcome Global Talents to West China Hospital/West China School of Medicine of Sichuan University

Top Talents; Leading Talents; Excellent Overseas Young Talents on National level; Overseas Young Talents

Open Faculty Position in Mathematical and Information Security

We are now seeking outstanding candidates in all areas of mathematics and information security.

Dongguan, Guangdong, China

GREAT BAY INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDY: Institute of Mathematical and Information Security

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Review Paper Format: How To Write A Review Article Fast

This guide aims to demystify the review paper format, presenting practical tips to help you accelerate the writing process.

From understanding the structure to synthesising literature effectively, we’ll explore how to create a compelling review article swiftly, ensuring your work is both impactful and timely.

Whether you’re a seasoned researcher or a budding scholar, these insights will streamline your writing journey.

Research Paper, Review Paper Format

| Parts | Notes |

|---|---|

| Title & Abstract | Sets the stage with a concise title and a descriptive abstract summarising the review’s scope and findings. |

| Introduction | Lays the groundwork by presenting the research question, justifying the review’s importance, and highlighting knowledge gaps. |

| Methodology | Details the research methods used to select, assess, and synthesise studies, showcasing the review’s rigor and integrity. |

| Body | The core section where literature is summarised, analysed, and critiqued, synthesising evidence and presenting arguments with well-structured paragraphs. |

| Discussion & Conclusion | Weaves together main points, reflects on the findings’ implications for the field, and suggests future research directions. |

| Citation | Acknowledges the scholarly community’s contributions, linking to cited research and enriching the review’s academic discourse. |

What Is A Review Paper?

Diving into the realm of scholarly communication, you might have stumbled upon a research review article.

This unique genre serves to synthesise existing data, offering a panoramic view of the current state of knowledge on a particular topic.

Unlike a standard research article that presents original experiments, a review paper delves into published literature, aiming to:

- clarify, and

- evaluate previous findings.

Imagine you’re tasked to write a review article. The starting point is often a burning research question. Your mission? To scour various journals, piecing together a well-structured narrative that not only summarises key findings but also identifies gaps in existing literature.

This is where the magic of review writing shines – it’s about creating a roadmap for future research, highlighting areas ripe for exploration.

Review articles come in different flavours, with systematic reviews and meta-analyses being the gold standards. The methodology here is meticulous, with a clear protocol for selecting and evaluating studies.

This rigorous approach ensures that your review is more than just an overview; it’s a critical analysis that adds depth to the understanding of the subject.

Crafting a good review requires mastering the art of citation. Every claim or observation you make needs to be backed by relevant literature. This not only lends credibility to your work but also provides a treasure trove of information for readers eager to delve deeper.

Types Of Review Paper

Not all review articles are created equal. Each type has its methodology, purpose, and format, catering to different research needs and questions.

Systematic Review Paper

First up is the systematic review, the crème de la crème of review types. It’s known for its rigorous methodology, involving a detailed plan for:

- identifying,

- selecting, and

- critically appraising relevant research.

The aim? To answer a specific research question. Systematic reviews often include meta-analyses, where data from multiple studies are statistically combined to provide more robust conclusions. This review type is a cornerstone in evidence-based fields like healthcare.

Literature Review Paper

Then there’s the literature review, a broader type you might encounter.

Here, the goal is to give an overview of the main points and debates on a topic, without the stringent methodological framework of a systematic review.

Literature reviews are great for getting a grasp of the field and identifying where future research might head. Often reading literature review papers can help you to learn about a topic rather quickly.

Narrative Reviews

Narrative reviews allow for a more flexible approach. Authors of narrative reviews draw on existing literature to provide insights or critique a certain area of research.

This is generally done with a less formal structure than systematic reviews. This type is particularly useful for areas where it’s difficult to quantify findings across studies.

Scoping Reviews

Scoping reviews are gaining traction for their ability to map out the existing literature on a broad topic, identifying:

- key concepts,

- theories, and

Unlike systematic reviews, scoping reviews have a more exploratory approach, which can be particularly useful in emerging fields or for topics that haven’t been comprehensively reviewed before.

Each type of review serves a unique purpose and requires a specific skill set. Whether you’re looking to summarise existing findings, synthesise data for evidence-based practice, or explore new research territories, there’s a review type that fits the bill.

Knowing how to write, read, and interpret these reviews can significantly enhance your understanding of any research area.

What Are The Parts In A Review Paper

A review paper has a pretty set structure, with minor changes here and there to suit the topic covered. The format not only organises your thoughts but also guides your readers through the complexities of your topic.

Title & Abstract

Starting with the title and abstract, you set the stage. The title should be a concise indicator of the content, making it easier for others to quickly tell what your article content is about.

As for the abstract, it should act as a descriptive summary, offering a snapshot of your review’s scope and findings.

Introduction

The introduction lays the groundwork, presenting the research question that drives your review. It’s here you:

- justify the importance of your review,

- delineating the current state of knowledge and

- highlighting gaps.

This section aims to articulate the significance of the topic and your objective in exploring it.

Methodology

The methodology section is the backbone of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, detailing the research methods employed to select, assess, and synthesise studies.

This transparency allows readers to gauge the rigour and reproducibility of your review. It’s a testament to the integrity of your work, showing how you’ve minimised bias.

The heart of your review lies in the body, where you:

- analyse, and

- critique existing literature.

This is where you synthesise evidence, draw connections, and present both sides of any argument. Well-structured paragraphs and clear subheadings guide readers through your analysis, offering insights and fostering a deeper understanding of the subject.

Discussion & Conclusion

The discussion or conclusion section is where you weave together the main points, reflecting on what your findings mean for the field.

It’s about connecting the dots, offering a synthesis of evidence that answers your initial research question. This part often hints at future research directions, suggesting areas that need further exploration due to gaps in existing knowledge.

Lastly, the citation list is your nod to the scholarly community, acknowledging the contributions of others. Each citation is a thread in the larger tapestry of academic discourse, enabling readers to delve deeper into the research that has shaped your review.

Tips To Write An Review Article Fast

Writing a review article quickly without sacrificing quality might seem like a tall order, but with the right approach, it’s entirely achievable.

Clearly Define Your Research Question

Clearly define your research question. A focused question not only narrows down the scope of your literature search but also keeps your review concise and on track.

By honing in on a specific aspect of a broader topic, you can avoid the common pitfall of becoming overwhelmed by the vast expanse of available literature. This specificity allows you to zero in on the most relevant studies, making your review more impactful.

Efficient Literature Searching

Utilise databases specific to your field and employ advanced search techniques like Boolean operators. This can drastically reduce the time you spend sifting through irrelevant articles.

Additionally, leveraging citation chains—looking at who has cited a pivotal paper in your area and who it cites—can uncover valuable sources you might otherwise miss.

Organise Your Findings Systematically

Developing a robust organisation strategy is key. As you gather sources, categorize them based on themes or methodologies. This not only aids in structuring your review but also in identifying areas where research is lacking or abundant.

Tools like citation management software can be invaluable here, helping you keep track of your sources and their key points. We list out some of the best AI tools for academic research here.

Build An Outline Before Writing

Don’t underestimate the power of a well-structured outline. A clear blueprint of your article can guide your writing process, ensuring that each section flows logically into the next.

This roadmap not only speeds up the writing process by providing a clear direction but also helps maintain coherence, ensuring your review article delivers a compelling narrative that advances understanding in your field.

Start Writing With The Easiest Sections

When it’s time to write, start with sections you find easiest. This might be the methodology or a particular thematic section where you feel most confident.

Getting words on the page can build momentum, making it easier to tackle more challenging sections later.

Remember, your first draft doesn’t have to be perfect; the goal is to start articulating your synthesis of the literature.

Learn How To Write An Article Review

Mastering the review paper format is a crucial step towards efficient academic writing. By adhering to the structured components outlined, you can streamline the creation of a compelling review article.

Embracing these guidelines not only speeds up the writing process but also enhances the clarity and impact of your work, ensuring your contributions to scholarly discourse are both valuable and timely.

Dr Andrew Stapleton has a Masters and PhD in Chemistry from the UK and Australia. He has many years of research experience and has worked as a Postdoctoral Fellow and Associate at a number of Universities. Although having secured funding for his own research, he left academia to help others with his YouTube channel all about the inner workings of academia and how to make it work for you.

Thank you for visiting Academia Insider.

We are here to help you navigate Academia as painlessly as possible. We are supported by our readers and by visiting you are helping us earn a small amount through ads and affiliate revenue - Thank you!

2024 © Academia Insider

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Turk J Urol

- v.39(Suppl 1); 2013 Sep

How to write a review article?

In the medical sciences, the importance of review articles is rising. When clinicians want to update their knowledge and generate guidelines about a topic, they frequently use reviews as a starting point. The value of a review is associated with what has been done, what has been found and how these findings are presented. Before asking ‘how,’ the question of ‘why’ is more important when starting to write a review. The main and fundamental purpose of writing a review is to create a readable synthesis of the best resources available in the literature for an important research question or a current area of research. Although the idea of writing a review is attractive, it is important to spend time identifying the important questions. Good review methods are critical because they provide an unbiased point of view for the reader regarding the current literature. There is a consensus that a review should be written in a systematic fashion, a notion that is usually followed. In a systematic review with a focused question, the research methods must be clearly described. A ‘methodological filter’ is the best method for identifying the best working style for a research question, and this method reduces the workload when surveying the literature. An essential part of the review process is differentiating good research from bad and leaning on the results of the better studies. The ideal way to synthesize studies is to perform a meta-analysis. In conclusion, when writing a review, it is best to clearly focus on fixed ideas, to use a procedural and critical approach to the literature and to express your findings in an attractive way.

The importance of review articles in health sciences is increasing day by day. Clinicians frequently benefit from review articles to update their knowledge in their field of specialization, and use these articles as a starting point for formulating guidelines. [ 1 , 2 ] The institutions which provide financial support for further investigations resort to these reviews to reveal the need for these researches. [ 3 ] As is the case with all other researches, the value of a review article is related to what is achieved, what is found, and the way of communicating this information. A few studies have evaluated the quality of review articles. Murlow evaluated 50 review articles published in 1985, and 1986, and revealed that none of them had complied with clear-cut scientific criteria. [ 4 ] In 1996 an international group that analyzed articles, demonstrated the aspects of review articles, and meta-analyses that had not complied with scientific criteria, and elaborated QUOROM (QUality Of Reporting Of Meta-analyses) statement which focused on meta-analyses of randomized controlled studies. [ 5 ] Later on this guideline was updated, and named as PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses). [ 6 ]

Review articles are divided into 2 categories as narrative, and systematic reviews. Narrative reviews are written in an easily readable format, and allow consideration of the subject matter within a large spectrum. However in a systematic review, a very detailed, and comprehensive literature surveying is performed on the selected topic. [ 7 , 8 ] Since it is a result of a more detailed literature surveying with relatively lesser involvement of author’s bias, systematic reviews are considered as gold standard articles. Systematic reviews can be diivded into qualitative, and quantitative reviews. In both of them detailed literature surveying is performed. However in quantitative reviews, study data are collected, and statistically evaluated (ie. meta-analysis). [ 8 ]

Before inquring for the method of preparation of a review article, it is more logical to investigate the motivation behind writing the review article in question. The fundamental rationale of writing a review article is to make a readable synthesis of the best literature sources on an important research inquiry or a topic. This simple definition of a review article contains the following key elements:

- The question(s) to be dealt with

- Methods used to find out, and select the best quality researches so as to respond to these questions.

- To synthetize available, but quite different researches

For the specification of important questions to be answered, number of literature references to be consulted should be more or less determined. Discussions should be conducted with colleagues in the same area of interest, and time should be reserved for the solution of the problem(s). Though starting to write the review article promptly seems to be very alluring, the time you spend for the determination of important issues won’t be a waste of time. [ 9 ]

The PRISMA statement [ 6 ] elaborated to write a well-designed review articles contains a 27-item checklist ( Table 1 ). It will be reasonable to fulfill the requirements of these items during preparation of a review article or a meta-analysis. Thus preparation of a comprehensible article with a high-quality scientific content can be feasible.

PRISMA statement: A 27-item checklist

| Title | ||

| Title | 1 Identify the article as a systematic review, meta-analysis, or both | |

| Summary | ||

| Structured summary | 2 Write a structured summary including, as applicable, background; objectives; data sources; study eligibility criteria, participants, treatments, study appraisal and synthesis methods; results; limitations; conclusions and implications of key findings; and systematic review registration number | |

| Introduction | ||

| Rationale | 3 Explain the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known | |

| Objectives | 4 Provide an explicit statement of questions being addressed with reference to participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design (PICOS) | |

| Methods | ||

| Protocol and registration | 5 Indicate if a review protocol exists, if and where it can be accessed (such as a web address), and, if available, provide registration information including the registration number | |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 Specify study characteristics (such as PICOS, length of follow-up) and report characteristics (such as years considered, language, publication status) used as criteria for eligibility, giving rationale | |

| Sources of Information | 7 Describe all information sources in the survey (such as databases with dates of coverage, contact with study authors to identify additional studies) and date last searched | |

| Survey | 8 Present the full electronic search strategy for at least one major database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated | |

| Study selection | 9 State the process for selecting studies (that is, for screening, for determining eligibility, for inclusion in the systematic review, and, if applicable, for inclusion in the meta-analysis) | |

| Data collection process | 10 Describe the method of data extraction from reports (such as piloted forms, independently by two reviewers) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators | |

| Data items | 11 List and define all variables for which data were sought (such as PICOS, funding sources) and any assumptions and simplifications made | |

| Risk of bias in individual studies | 12 Describe methods used for assessing risk of bias in individual studies (including specification of whether this was done at the study or outcome level, or both), and how this information is to be used in any data synthesis | |

| Summary measures | 13 State the principal summary measures (such as risk ratio, difference in means) | |

| Synthesis of outcomes | 14 For each meta-analysis, explain methods of data use, and combination methods of study outcomes, and if done consistency measurements should be indicated (ie P test) | |

| Risk of bias across studies | 15 Specify any assessment of risk of bias that may affect the cumulative evidence (such as publication bias, selective reporting within studies). | |

| Additional analyses | 16 Describe methods of additional analyses (such as sensitivity or subgroup analyses, meta-regression), if done, indicating which were pre-specified. | |

| Results | ||

| Study selection | 17 Give numbers of studies screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally with a flow diagram. | |

| Study characteristics | 18 For each study, present characteristics for which data were extracted (such as study size, PICOS, follow-up period) and provide the citation. | |

| Risk of bias within studies | 19 Present data on risk of bias of each study and, if available, any outcome-level assessment (see item 12) | |

| Results of individual studies | 20 For all outcomes considered (benefits and harms), present, for each study, simple summary data for each intervention group and effect estimates and confidence intervals, ideally with a forest plot (a type of graph used in meta-analyses which demonstrates relat, ve success rates of treatment outcomes of multiple scientific studies analyzing the same topic) | |

| Syntheses of resxults | 21 Present the results of each meta-analyses including confidence intervals and measures of consistency | |

| Risk of bias across studies | 22 Present results of any assessment of risk of bias across studies (see item 15). | |

| Additional analyses | 23 Give results of additional analyses, if done such as sensitivity or subgroup analyses, meta-regression (see item 16) | |

| Discussion | ||

| Summary of evidence | 24 Summarize the main findings, including the strength of evidence for each main outcome; consider their relevance to key groups (such as healthcare providers, users, and policy makers) | |

| Limitations | 25 Discuss limitations at study and outcome level (such as risk of bias), and at review level such as incomplete retrieval of identified research, reporting bias | |

| Conclusions | 26 Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence, and implications for future research | |

| Funding | ||

| Funding | 27 Indicate sources of funding or other support (such as supply of data) for the systematic review, and the role of funders for the systematic review |

Contents and format

Important differences exist between systematic, and non-systematic reviews which especially arise from methodologies used in the description of the literature sources. A non-systematic review means use of articles collected for years with the recommendations of your colleagues, while systematic review is based on struggles to search for, and find the best possible researches which will respond to the questions predetermined at the start of the review.

Though a consensus has been reached about the systematic design of the review articles, studies revealed that most of them had not been written in a systematic format. McAlister et al. analyzed review articles in 6 medical journals, and disclosed that in less than one fourth of the review articles, methods of description, evaluation or synthesis of evidence had been provided, one third of them had focused on a clinical topic, and only half of them had provided quantitative data about the extend of the potential benefits. [ 10 ]

Use of proper methodologies in review articles is important in that readers assume an objective attitude towards updated information. We can confront two problems while we are using data from researches in order to answer certain questions. Firstly, we can be prejudiced during selection of research articles or these articles might be biased. To minimize this risk, methodologies used in our reviews should allow us to define, and use researches with minimal degree of bias. The second problem is that, most of the researches have been performed with small sample sizes. In statistical methods in meta-analyses, available researches are combined to increase the statistical power of the study. The problematic aspect of a non-systematic review is that our tendency to give biased responses to the questions, in other words we apt to select the studies with known or favourite results, rather than the best quality investigations among them.

As is the case with many research articles, general format of a systematic review on a single subject includes sections of Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion ( Table 2 ).

Structure of a systematic review

| Introduction | Presents the problem and certain issues dealt in the review article |

| Methods | Describes research, and evaluation process Specifies the number of studies evaluated orselected |

| Results | Describes the quality, and outcomes of the selected studies |

| Discussion | Summarizes results, limitations, and outcomes of the procedure and research |

Preparation of the review article

Steps, and targets of constructing a good review article are listed in Table 3 . To write a good review article the items in Table 3 should be implemented step by step. [ 11 – 13 ]

Steps of a systematic review

| Formulation of researchable questions | Select answerable questions |

| Disclosure of studies | Databases, and key words |

| Evaluation of its quality | Quality criteria during selection of studies |

| Synthesis | Methods interpretation, and synthesis of outcomes |

The research question

It might be helpful to divide the research question into components. The most prevalently used format for questions related to the treatment is PICO (P - Patient, Problem or Population; I-Intervention; C-appropriate Comparisons, and O-Outcome measures) procedure. For example In female patients (P) with stress urinary incontinence, comparisons (C) between transobturator, and retropubic midurethral tension-free band surgery (I) as for patients’ satisfaction (O).

Finding Studies

In a systematic review on a focused question, methods of investigation used should be clearly specified.

Ideally, research methods, investigated databases, and key words should be described in the final report. Different databases are used dependent on the topic analyzed. In most of the clinical topics, Medline should be surveyed. However searching through Embase and CINAHL can be also appropriate.

While determining appropriate terms for surveying, PICO elements of the issue to be sought may guide the process. Since in general we are interested in more than one outcome, P, and I can be key elements. In this case we should think about synonyms of P, and I elements, and combine them with a conjunction AND.

One method which might alleviate the workload of surveying process is “methodological filter” which aims to find the best investigation method for each research question. A good example of this method can be found in PubMed interface of Medline. The Clinical Queries tool offers empirically developed filters for five different inquiries as guidelines for etiology, diagnosis, treatment, prognosis or clinical prediction.

Evaluation of the Quality of the Study

As an indispensable component of the review process is to discriminate good, and bad quality researches from each other, and the outcomes should be based on better qualified researches, as far as possible. To achieve this goal you should know the best possible evidence for each type of question The first component of the quality is its general planning/design of the study. General planning/design of a cohort study, a case series or normal study demonstrates variations.

A hierarchy of evidence for different research questions is presented in Table 4 . However this hierarchy is only a first step. After you find good quality research articles, you won’t need to read all the rest of other articles which saves you tons of time. [ 14 ]

Determination of levels of evidence based on the type of the research question

| I | Systematic review of Level II studies | Systematic review of Level II studies | Systematic review of Level II studies | Systematic review of Level II studies |

| II | Randomized controlled study | Crross-sectional study in consecutive patients | Initial cohort study | Prospective cohort study |

| III | One of the following: Non-randomized experimental study (ie. controlled pre-, and post-test intervention study) Comparative studies with concurrent control groups (observational study) (ie. cohort study, case-control study) | One of the following: Cross-sectional study in non-consecutive case series; diagnostic case-control study | One of the following: Untreated control group patients in a randomized controlled study, integrated cohort study | One of the following: Retrospective cohort study, case-control study (Note: these are most prevalently used types of etiological studies; for other alternatives, and interventional studies see Level III |

| IV | Case series | Case series | Case series or cohort studies with patients at different stages of their disease states |

Formulating a Synthesis

Rarely all researches arrive at the same conclusion. In this case a solution should be found. However it is risky to make a decision based on the votes of absolute majority. Indeed, a well-performed large scale study, and a weakly designed one are weighed on the same scale. Therefore, ideally a meta-analysis should be performed to solve apparent differences. Ideally, first of all, one should be focused on the largest, and higher quality study, then other studies should be compared with this basic study.

Conclusions

In conclusion, during writing process of a review article, the procedures to be achieved can be indicated as follows: 1) Get rid of fixed ideas, and obsessions from your head, and view the subject from a large perspective. 2) Research articles in the literature should be approached with a methodological, and critical attitude and 3) finally data should be explained in an attractive way.

Libraries | Research Guides

Literature reviews, what is a literature review, learning more about how to do a literature review.

- Planning the Review

- The Research Question

- Choosing Where to Search

- Organizing the Review

- Writing the Review

A literature review is a review and synthesis of existing research on a topic or research question. A literature review is meant to analyze the scholarly literature, make connections across writings and identify strengths, weaknesses, trends, and missing conversations. A literature review should address different aspects of a topic as it relates to your research question. A literature review goes beyond a description or summary of the literature you have read.

- Sage Research Methods Core This link opens in a new window SAGE Research Methods supports research at all levels by providing material to guide users through every step of the research process. SAGE Research Methods is the ultimate methods library with more than 1000 books, reference works, journal articles, and instructional videos by world-leading academics from across the social sciences, including the largest collection of qualitative methods books available online from any scholarly publisher. – Publisher

- Next: Planning the Review >>

- Last Updated: Jul 8, 2024 11:22 AM

- URL: https://libguides.northwestern.edu/literaturereviews

What is a review article?

Learn how to write a review article.

What is a review article? A review article can also be called a literature review, or a review of literature. It is a survey of previously published research on a topic. It should give an overview of current thinking on the topic. And, unlike an original research article, it will not present new experimental results.

Writing a review of literature is to provide a critical evaluation of the data available from existing studies. Review articles can identify potential research areas to explore next, and sometimes they will draw new conclusions from the existing data.

Why write a review article?

To provide a comprehensive foundation on a topic.

To explain the current state of knowledge.

To identify gaps in existing studies for potential future research.

To highlight the main methodologies and research techniques.

Did you know?

There are some journals that only publish review articles, and others that do not accept them.

Make sure you check the aims and scope of the journal you’d like to publish in to find out if it’s the right place for your review article.

How to write a review article

Below are 8 key items to consider when you begin writing your review article.

Check the journal’s aims and scope

Make sure you have read the aims and scope for the journal you are submitting to and follow them closely. Different journals accept different types of articles and not all will accept review articles, so it’s important to check this before you start writing.

Define your scope

Define the scope of your review article and the research question you’ll be answering, making sure your article contributes something new to the field.

As award-winning author Angus Crake told us, you’ll also need to “define the scope of your review so that it is manageable, not too large or small; it may be necessary to focus on recent advances if the field is well established.”

Finding sources to evaluate

When finding sources to evaluate, Angus Crake says it’s critical that you “use multiple search engines/databases so you don’t miss any important ones.”

For finding studies for a systematic review in medical sciences, read advice from NCBI .

Writing your title, abstract and keywords

Spend time writing an effective title, abstract and keywords. This will help maximize the visibility of your article online, making sure the right readers find your research. Your title and abstract should be clear, concise, accurate, and informative.

For more information and guidance on getting these right, read our guide to writing a good abstract and title and our researcher’s guide to search engine optimization .

Introduce the topic

Does a literature review need an introduction? Yes, always start with an overview of the topic and give some context, explaining why a review of the topic is necessary. Gather research to inform your introduction and make it broad enough to reach out to a large audience of non-specialists. This will help maximize its wider relevance and impact.

Don’t make your introduction too long. Divide the review into sections of a suitable length to allow key points to be identified more easily.

Include critical discussion

Make sure you present a critical discussion, not just a descriptive summary of the topic. If there is contradictory research in your area of focus, make sure to include an element of debate and present both sides of the argument. You can also use your review paper to resolve conflict between contradictory studies.

What researchers say

Angus Crake, researcher

As part of your conclusion, include making suggestions for future research on the topic. Focus on the goal to communicate what you understood and what unknowns still remains.

Use a critical friend

Always perform a final spell and grammar check of your article before submission.

You may want to ask a critical friend or colleague to give their feedback before you submit. If English is not your first language, think about using a language-polishing service.

Find out more about how Taylor & Francis Editing Services can help improve your manuscript before you submit.

What is the difference between a research article and a review article?

| Differences in... | ||

|---|---|---|

| Presents the viewpoint of the author | Critiques the viewpoint of other authors on a particular topic | |

| New content | Assessing already published content | |

| Depends on the word limit provided by the journal you submit to | Tends to be shorter than a research article, but will still need to adhere to words limit |

Before you submit your review article…

Complete this checklist before you submit your review article:

Have you checked the journal’s aims and scope?

Have you defined the scope of your article?

Did you use multiple search engines to find sources to evaluate?

Have you written a descriptive title and abstract using keywords?

Did you start with an overview of the topic?

Have you presented a critical discussion?

Have you included future suggestions for research in your conclusion?

Have you asked a friend to do a final spell and grammar check?

Expert help for your manuscript

Taylor & Francis Editing Services offers a full range of pre-submission manuscript preparation services to help you improve the quality of your manuscript and submit with confidence.

Related resources

How to edit your paper

Writing a scientific literature review

How To Write An A-Grade Literature Review

3 straightforward steps (with examples) + free template.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | October 2019

Quality research is about building onto the existing work of others , “standing on the shoulders of giants”, as Newton put it. The literature review chapter of your dissertation, thesis or research project is where you synthesise this prior work and lay the theoretical foundation for your own research.

Long story short, this chapter is a pretty big deal, which is why you want to make sure you get it right . In this post, I’ll show you exactly how to write a literature review in three straightforward steps, so you can conquer this vital chapter (the smart way).

Overview: The Literature Review Process

- Understanding the “ why “

- Finding the relevant literature

- Cataloguing and synthesising the information

- Outlining & writing up your literature review

- Example of a literature review

But first, the “why”…

Before we unpack how to write the literature review chapter, we’ve got to look at the why . To put it bluntly, if you don’t understand the function and purpose of the literature review process, there’s no way you can pull it off well. So, what exactly is the purpose of the literature review?

Well, there are (at least) four core functions:

- For you to gain an understanding (and demonstrate this understanding) of where the research is at currently, what the key arguments and disagreements are.

- For you to identify the gap(s) in the literature and then use this as justification for your own research topic.

- To help you build a conceptual framework for empirical testing (if applicable to your research topic).

- To inform your methodological choices and help you source tried and tested questionnaires (for interviews ) and measurement instruments (for surveys ).

Most students understand the first point but don’t give any thought to the rest. To get the most from the literature review process, you must keep all four points front of mind as you review the literature (more on this shortly), or you’ll land up with a wonky foundation.

Okay – with the why out the way, let’s move on to the how . As mentioned above, writing your literature review is a process, which I’ll break down into three steps:

- Finding the most suitable literature

- Understanding , distilling and organising the literature

- Planning and writing up your literature review chapter

Importantly, you must complete steps one and two before you start writing up your chapter. I know it’s very tempting, but don’t try to kill two birds with one stone and write as you read. You’ll invariably end up wasting huge amounts of time re-writing and re-shaping, or you’ll just land up with a disjointed, hard-to-digest mess . Instead, you need to read first and distil the information, then plan and execute the writing.

Step 1: Find the relevant literature

Naturally, the first step in the literature review journey is to hunt down the existing research that’s relevant to your topic. While you probably already have a decent base of this from your research proposal , you need to expand on this substantially in the dissertation or thesis itself.

Essentially, you need to be looking for any existing literature that potentially helps you answer your research question (or develop it, if that’s not yet pinned down). There are numerous ways to find relevant literature, but I’ll cover my top four tactics here. I’d suggest combining all four methods to ensure that nothing slips past you:

Method 1 – Google Scholar Scrubbing

Google’s academic search engine, Google Scholar , is a great starting point as it provides a good high-level view of the relevant journal articles for whatever keyword you throw at it. Most valuably, it tells you how many times each article has been cited, which gives you an idea of how credible (or at least, popular) it is. Some articles will be free to access, while others will require an account, which brings us to the next method.

Method 2 – University Database Scrounging

Generally, universities provide students with access to an online library, which provides access to many (but not all) of the major journals.

So, if you find an article using Google Scholar that requires paid access (which is quite likely), search for that article in your university’s database – if it’s listed there, you’ll have access. Note that, generally, the search engine capabilities of these databases are poor, so make sure you search for the exact article name, or you might not find it.

Method 3 – Journal Article Snowballing

At the end of every academic journal article, you’ll find a list of references. As with any academic writing, these references are the building blocks of the article, so if the article is relevant to your topic, there’s a good chance a portion of the referenced works will be too. Do a quick scan of the titles and see what seems relevant, then search for the relevant ones in your university’s database.

Method 4 – Dissertation Scavenging

Similar to Method 3 above, you can leverage other students’ dissertations. All you have to do is skim through literature review chapters of existing dissertations related to your topic and you’ll find a gold mine of potential literature. Usually, your university will provide you with access to previous students’ dissertations, but you can also find a much larger selection in the following databases:

- Open Access Theses & Dissertations

- Stanford SearchWorks

Keep in mind that dissertations and theses are not as academically sound as published, peer-reviewed journal articles (because they’re written by students, not professionals), so be sure to check the credibility of any sources you find using this method. You can do this by assessing the citation count of any given article in Google Scholar. If you need help with assessing the credibility of any article, or with finding relevant research in general, you can chat with one of our Research Specialists .

Alright – with a good base of literature firmly under your belt, it’s time to move onto the next step.

Need a helping hand?

Step 2: Log, catalogue and synthesise

Once you’ve built a little treasure trove of articles, it’s time to get reading and start digesting the information – what does it all mean?

While I present steps one and two (hunting and digesting) as sequential, in reality, it’s more of a back-and-forth tango – you’ll read a little , then have an idea, spot a new citation, or a new potential variable, and then go back to searching for articles. This is perfectly natural – through the reading process, your thoughts will develop , new avenues might crop up, and directional adjustments might arise. This is, after all, one of the main purposes of the literature review process (i.e. to familiarise yourself with the current state of research in your field).

As you’re working through your treasure chest, it’s essential that you simultaneously start organising the information. There are three aspects to this:

- Logging reference information

- Building an organised catalogue

- Distilling and synthesising the information

I’ll discuss each of these below:

2.1 – Log the reference information

As you read each article, you should add it to your reference management software. I usually recommend Mendeley for this purpose (see the Mendeley 101 video below), but you can use whichever software you’re comfortable with. Most importantly, make sure you load EVERY article you read into your reference manager, even if it doesn’t seem very relevant at the time.

2.2 – Build an organised catalogue

In the beginning, you might feel confident that you can remember who said what, where, and what their main arguments were. Trust me, you won’t. If you do a thorough review of the relevant literature (as you must!), you’re going to read many, many articles, and it’s simply impossible to remember who said what, when, and in what context . Also, without the bird’s eye view that a catalogue provides, you’ll miss connections between various articles, and have no view of how the research developed over time. Simply put, it’s essential to build your own catalogue of the literature.

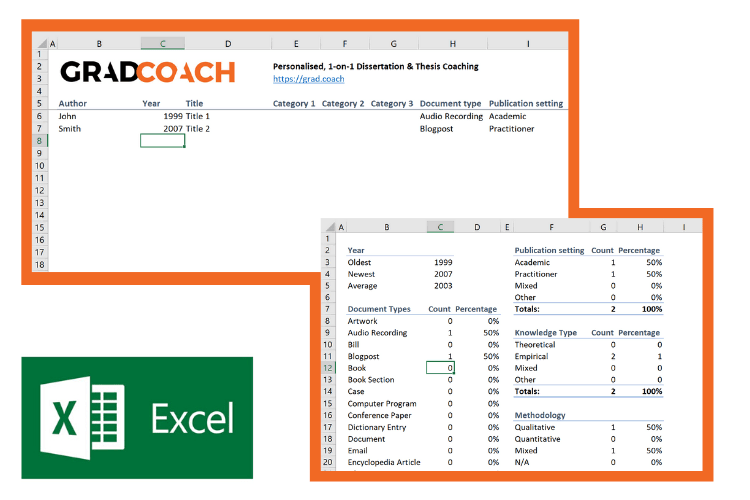

I would suggest using Excel to build your catalogue, as it allows you to run filters, colour code and sort – all very useful when your list grows large (which it will). How you lay your spreadsheet out is up to you, but I’d suggest you have the following columns (at minimum):

- Author, date, title – Start with three columns containing this core information. This will make it easy for you to search for titles with certain words, order research by date, or group by author.

- Categories or keywords – You can either create multiple columns, one for each category/theme and then tick the relevant categories, or you can have one column with keywords.

- Key arguments/points – Use this column to succinctly convey the essence of the article, the key arguments and implications thereof for your research.

- Context – Note the socioeconomic context in which the research was undertaken. For example, US-based, respondents aged 25-35, lower- income, etc. This will be useful for making an argument about gaps in the research.

- Methodology – Note which methodology was used and why. Also, note any issues you feel arise due to the methodology. Again, you can use this to make an argument about gaps in the research.

- Quotations – Note down any quoteworthy lines you feel might be useful later.

- Notes – Make notes about anything not already covered. For example, linkages to or disagreements with other theories, questions raised but unanswered, shortcomings or limitations, and so forth.

If you’d like, you can try out our free catalog template here (see screenshot below).

2.3 – Digest and synthesise

Most importantly, as you work through the literature and build your catalogue, you need to synthesise all the information in your own mind – how does it all fit together? Look for links between the various articles and try to develop a bigger picture view of the state of the research. Some important questions to ask yourself are:

- What answers does the existing research provide to my own research questions ?

- Which points do the researchers agree (and disagree) on?

- How has the research developed over time?

- Where do the gaps in the current research lie?

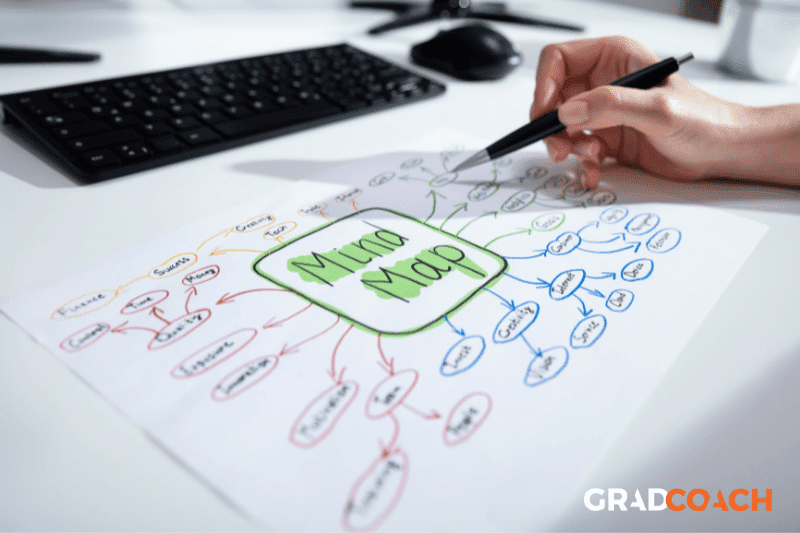

To help you develop a big-picture view and synthesise all the information, you might find mind mapping software such as Freemind useful. Alternatively, if you’re a fan of physical note-taking, investing in a large whiteboard might work for you.

Step 3: Outline and write it up!

Once you’re satisfied that you have digested and distilled all the relevant literature in your mind, it’s time to put pen to paper (or rather, fingers to keyboard). There are two steps here – outlining and writing:

3.1 – Draw up your outline

Having spent so much time reading, it might be tempting to just start writing up without a clear structure in mind. However, it’s critically important to decide on your structure and develop a detailed outline before you write anything. Your literature review chapter needs to present a clear, logical and an easy to follow narrative – and that requires some planning. Don’t try to wing it!

Naturally, you won’t always follow the plan to the letter, but without a detailed outline, you’re more than likely going to end up with a disjointed pile of waffle , and then you’re going to spend a far greater amount of time re-writing, hacking and patching. The adage, “measure twice, cut once” is very suitable here.

In terms of structure, the first decision you’ll have to make is whether you’ll lay out your review thematically (into themes) or chronologically (by date/period). The right choice depends on your topic, research objectives and research questions, which we discuss in this article .

Once that’s decided, you need to draw up an outline of your entire chapter in bullet point format. Try to get as detailed as possible, so that you know exactly what you’ll cover where, how each section will connect to the next, and how your entire argument will develop throughout the chapter. Also, at this stage, it’s a good idea to allocate rough word count limits for each section, so that you can identify word count problems before you’ve spent weeks or months writing!

PS – check out our free literature review chapter template…

3.2 – Get writing

With a detailed outline at your side, it’s time to start writing up (finally!). At this stage, it’s common to feel a bit of writer’s block and find yourself procrastinating under the pressure of finally having to put something on paper. To help with this, remember that the objective of the first draft is not perfection – it’s simply to get your thoughts out of your head and onto paper, after which you can refine them. The structure might change a little, the word count allocations might shift and shuffle, and you might add or remove a section – that’s all okay. Don’t worry about all this on your first draft – just get your thoughts down on paper.

Once you’ve got a full first draft (however rough it may be), step away from it for a day or two (longer if you can) and then come back at it with fresh eyes. Pay particular attention to the flow and narrative – does it fall fit together and flow from one section to another smoothly? Now’s the time to try to improve the linkage from each section to the next, tighten up the writing to be more concise, trim down word count and sand it down into a more digestible read.

Once you’ve done that, give your writing to a friend or colleague who is not a subject matter expert and ask them if they understand the overall discussion. The best way to assess this is to ask them to explain the chapter back to you. This technique will give you a strong indication of which points were clearly communicated and which weren’t. If you’re working with Grad Coach, this is a good time to have your Research Specialist review your chapter.

Finally, tighten it up and send it off to your supervisor for comment. Some might argue that you should be sending your work to your supervisor sooner than this (indeed your university might formally require this), but in my experience, supervisors are extremely short on time (and often patience), so, the more refined your chapter is, the less time they’ll waste on addressing basic issues (which you know about already) and the more time they’ll spend on valuable feedback that will increase your mark-earning potential.

Literature Review Example

In the video below, we unpack an actual literature review so that you can see how all the core components come together in reality.

Let’s Recap

In this post, we’ve covered how to research and write up a high-quality literature review chapter. Let’s do a quick recap of the key takeaways:

- It is essential to understand the WHY of the literature review before you read or write anything. Make sure you understand the 4 core functions of the process.

- The first step is to hunt down the relevant literature . You can do this using Google Scholar, your university database, the snowballing technique and by reviewing other dissertations and theses.

- Next, you need to log all the articles in your reference manager , build your own catalogue of literature and synthesise all the research.

- Following that, you need to develop a detailed outline of your entire chapter – the more detail the better. Don’t start writing without a clear outline (on paper, not in your head!)

- Write up your first draft in rough form – don’t aim for perfection. Remember, done beats perfect.

- Refine your second draft and get a layman’s perspective on it . Then tighten it up and submit it to your supervisor.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

38 Comments