Life after COVID: most people don’t want a return to normal – they want a fairer, more sustainable future

Chair of Cognitive Psychology, University of Bristol

Professor of Cognitive Psychology and Australian Research Council Future Fellow, The University of Western Australia

Disclosure statement

Stephan Lewandowsky receives funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 964728 (JITSUVAX). He also receives funding from the Australian Research Council via a Discovery Grant to Ullrich Ecker, from Jigsaw (a technology incubator created by Google), from UK Research and Innovation (through the Centre of Excellence, REPHRAIN), and from the Volkswagen Foundation in Germany. He also holds a European Research Council Advanced Grant (no. 101020961, PRODEMINFO) and receives funding from the John Templeton Foundation (via Wake Forest University’s Honesty Project).

Ullrich Ecker receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

University of Western Australia provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

University of Bristol provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

We are in a crisis now – and omicron has made it harder to imagine the pandemic ending. But it will not last forever. When the COVID outbreak is over, what do we want the world to look like?

In the early stages of the pandemic – from March to July 2020 – a rapid return to normal was on everyone’s lips, reflecting the hope that the virus might be quickly brought under control. Since then, alternative slogans such as “ build back better ” have also become prominent, promising a brighter, more equitable, more sustainable future based on significant or even radical change.

Returning to how things were, or moving on to something new – these are very different desires. But which is it that people want? In our recent research , we aimed to find out.

Along with Keri Facer of the University of Bristol, we conducted two studies, one in the summer of 2020 and another a year later. In these, we presented participants – a representative sample of 400 people from the UK and 600 from the US – with four possible futures, sketched in the table below. We designed these based on possible outcomes of the pandemic published in early 2020 in The Atlantic and The Conversation .

We were concerned with two aspects of the future: whether it would involve a “return to normal” or a progressive move to “build back better”, and whether it would concentrate power in the hands of government or return power to individuals.

Four possible futures

| “Collective safety” | “For freedom” |

| “Fairer future” | “Grassroots leadership” |

In both studies and in both countries, we found that people strongly preferred a progressive future over a return to normal. They also tended to prefer individual autonomy over strong government. On balance, across both experiments and both countries, the “grassroots leadership” proposal appeared to be most popular.

People’s political leanings affected preferences – those on the political right preferred a return to normal more than those on the left – yet intriguingly, strong opposition to a progressive future was quite limited, even among people on the right. This is encouraging because it suggests that opposition to “building back better” may be limited.

Our findings are consistent with other recent research , which suggests that even conservative voters want the environment to be at the heart of post-COVID economic reconstruction in the UK.

The misperceptions of the majority

This is what people wanted to happen – but how did they think things actually would end up? In both countries, participants felt that a return to normal was more likely than moving towards a progressive future. They also felt it was more likely that government would retain its power than return it to the people.

In other words, people thought they were unlikely to get the future they wanted. People want a progressive future but fear that they’ll get a return to normal with power vested in the government.

We also asked people to tell us what they thought others wanted. It turned out our participants thought that others wanted a return to normal much more than they actually did. This was observed in both the US and UK in both 2020 and 2021, though to varying extents.

This striking divergence between what people actually want, what they expect to get and what they think others want is what’s known as “ pluralistic ignorance ”.

This describes any situation where people who are in the majority think they are in the minority. Pluralistic ignorance can have problematic consequences because in the long run people often shift their attitudes towards what they perceive to be the prevailing norm. If people misperceive the norm, they may change their attitudes towards a minority opinion, rather than the minority adapting to the majority. This can be a problem if that minority opinion is a negative one – such as being opposed to vaccination , for example.

In our case, a consequence of pluralistic ignorance may be that a return to normal will become more acceptable in future, not because most people ever desired this outcome, but because they felt it was inevitable and that most others wanted it.

Ultimately, this would mean that the actual preferences of the majority never find the political expression that, in a democracy, they deserve.

To counter pluralistic ignorance, we should therefore try to ensure that people know the public’s opinion. This is not merely a necessary countermeasure to pluralistic ignorance and its adverse consequences – people’s motivation also generally increases when they feel their preferences and goals are shared by others. Therefore, simply informing people that there’s a social consensus for a progressive future could be what unleashes the motivation needed to achieve it.

- United States

- Coronavirus

- Coronavirus insights

- United Kingdom (UK)

Director of STEM

Community member - Training Delivery and Development Committee (Volunteer part-time)

Chief Executive Officer

Finance Business Partner

Head of Evidence to Action

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Two Years Into the Pandemic, Americans Inch Closer to a New Normal

Two years after the coronavirus outbreak upended life in the United States, Americans find themselves in an environment that is at once greatly improved and frustratingly familiar.

Around three-quarters of U.S. adults now report being fully vaccinated , a critical safeguard against the worst outcomes of a virus that has claimed the lives of more than 950,000 citizens. Teens and children as young as 5 are now eligible for vaccines . The national unemployment rate has plummeted from nearly 15% in the tumultuous first weeks of the outbreak to around 4% today. A large majority of K-12 parents report that their kids are back to receiving in-person instruction , and other hallmarks of public life, including sporting events and concerts, are again drawing crowds.

This Pew Research Center data essay summarizes key public opinion trends and societal shifts as the United States approaches the second anniversary of the coronavirus outbreak . The essay is based on survey data from the Center, data from government agencies, news reports and other sources. Links to the original sources of data – including the field dates, sample sizes and methodologies of surveys conducted by the Center – are included wherever possible. All references to Republicans and Democrats in this analysis include independents who lean toward each party.

Data essay from March 2021: A Year of U.S. Public Opinion on the Coronavirus Pandemic

The landscape in other ways remains unsettled. The staggering death toll of the virus continues to rise, with nearly as many Americans lost in the pandemic’s second year as in the first, despite the widespread availability of vaccines. The economic recovery has been uneven, with wage gains for many workers offset by the highest inflation rate in four decades and the labor market roiled by the Great Resignation . The nation’s political fractures are reflected in near-daily disputes over mask and vaccine rules. And thorny new societal problems have emerged, including alarming increases in murder and fatal drug overdose rates that may be linked to the upheaval caused by the pandemic.

For the public, the sense of optimism that the country might be turning the corner – evident in surveys shortly after President Joe Biden took office and as vaccines became widely available – has given way to weariness and frustration. A majority of Americans now give Biden negative marks for his handling of the outbreak, and ratings for other government leaders and public health officials have tumbled . Amid these criticisms, a growing share of Americans appear ready to move on to a new normal, even as the exact contours of that new normal are hard to discern.

A year ago, optimism was in the air

Biden won the White House in part because the public saw him as more qualified than former President Donald Trump to address the pandemic. In a January 2021 survey, a majority of registered voters said a major reason why Trump lost the election was that his administration did not do a good enough job handling the coronavirus outbreak.

At least initially, Biden inspired more confidence. In February 2021, 56% of Americans said they expected the new administration’s plans and policies to improve the coronavirus situation . By last March, 65% of U.S. adults said they were very or somewhat confident in Biden to handle the public health impact of the coronavirus.

The rapid deployment of vaccines only burnished Biden’s standing. After the new president easily met his goal of distributing 100 million doses in his first 100 days in office, 72% of Americans – including 55% of Republicans – said the administration was doing an excellent or good job overseeing the production and distribution of vaccines. As of this January, majorities in every major demographic group said they had received at least one dose of a vaccine. Most reported being fully vaccinated – defined at the time as having either two Pfizer or Moderna vaccines or one Johnson & Johnson – and most fully vaccinated adults said they had received a booster shot, too.

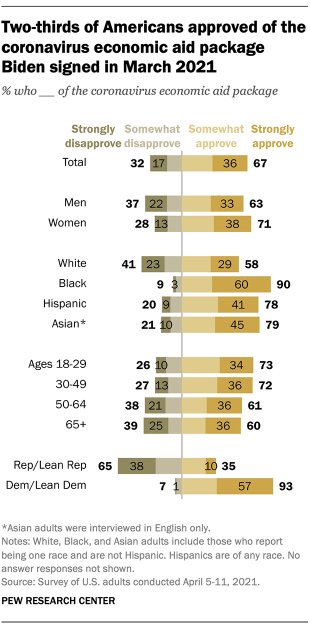

The Biden administration’s early moves on the economy also drew notable public support. Two-thirds of Americans, including around a third of Republicans, approved of the $1.9 trillion aid package Biden signed into law last March, one of several sprawling economic interventions authorized by administrations of both parties in the outbreak’s first year. Amid the wave of government spending, the U.S. economy grew in 2021 at its fastest annual rate since 1984 .

Globally, people preferred Biden’s approach to the pandemic over Trump’s. Across 12 countries surveyed in both 2020 and 2021, the median share of adults who said the U.S. was doing a good job responding to the outbreak more than doubled after Biden took office. Even so, people in these countries gave the U.S. lower marks than they gave to Germany, the World Health Organization and other countries and multilateral organizations.

Data essay: The Changing Political Geography of COVID-19 Over the Last Two Years

A familiar undercurrent of partisan division

Even if the national mood seemed to be improving last spring, the partisan divides that became so apparent in the first year of the pandemic did not subside. If anything, they intensified and moved into new arenas.

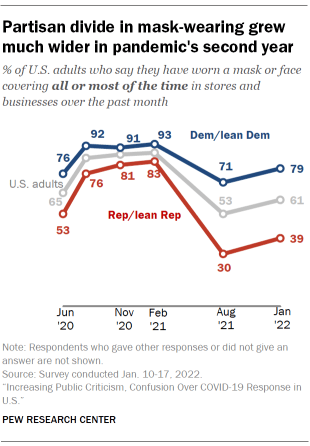

Masks and vaccines remained two of the most high-profile areas of contention. In February 2021, Republicans were only 10 percentage points less likely than Democrats (83% vs. 93%) to say they had worn a face covering in stores or other businesses all or most of the time in the past month. By January of this year, Republicans were 40 points less likely than Democrats to say they had done so (39% vs. 79%), even though new coronavirus cases were at an all-time high .

Republicans were also far less likely than Democrats to be fully vaccinated (60% vs. 85%) and to have received a booster shot (33% vs. 62%) as of January. Not surprisingly, they were much less likely than Democrats to favor vaccination requirements for a variety of activities, including traveling by airplane, attending a sporting event or concert, and eating inside of a restaurant.

Some of the most visible disputes involved policies at K-12 schools, including the factors that administrators should consider when deciding whether to keep classrooms open for in-person instruction. In January, Republican K-12 parents were more likely than Democrats to say a lot of consideration should be given to the possibility that kids will fall behind academically without in-person classes and the possibility that students will have negative emotional consequences if they don’t attend school in person. Democratic parents were far more likely than Republicans to say a lot of consideration should be given to the risks that COVID-19 poses to students and teachers.

The common thread running through these disagreements is that Republicans remain fundamentally less concerned about the virus than Democrats, despite some notable differences in attitudes and behaviors within each party . In January, almost two-thirds of Republicans (64%) said the coronavirus outbreak has been made a bigger deal than it really is . Most Democrats said the outbreak has either been approached about right (50%) or made a smaller deal than it really is (33%). (All references to Republicans and Democrats include independents who lean toward each party.)

New variants and new problems

The decline in new coronavirus cases, hospitalizations and deaths that took place last spring and summer was so encouraging that Biden announced in a July 4 speech that the nation was “closer than ever to declaring our independence from a deadly virus.” But the arrival of two new variants – first delta and then omicron – proved Biden’s assessment premature.

Some 350,000 Americans have died from COVID-19 since July 4, including an average of more than 2,500 a day at some points during the recent omicron wave – a number not seen since the first pandemic winter, when vaccines were not widely available. The huge number of deaths has ensured that even more Americans have a personal connection to the tragedy .

The threat of dangerous new variants had always loomed, of course. In February 2021, around half of Americans (51%) said they expected that new variants would lead to a major setback in efforts to contain the disease. But the ferocity of the delta and omicron surges still seemed to take the public aback, particularly when governments began to reimpose restrictions on daily life.

After announcing in May 2021 that vaccinated people no longer needed to wear masks in public, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reversed course during the delta wave and again recommended indoor mask-wearing for those in high-transmission areas. Local governments brought back their own mask mandates . Later, during the omicron wave, some major cities imposed new proof-of-vaccination requirements , while the CDC shortened its recommended isolation period for those who tested positive for the virus but had no symptoms. This latter move was at least partly aimed at addressing widespread worker shortages , including at airlines struggling during the height of the holiday travel season.

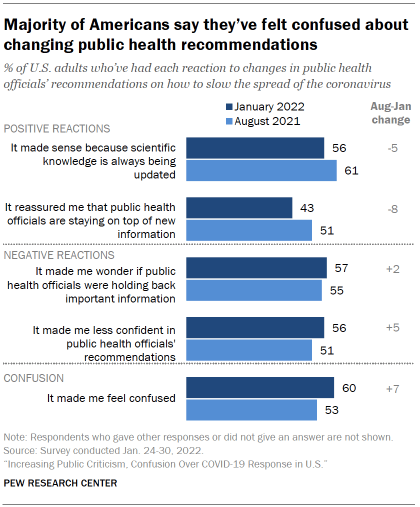

Amid these changes, public frustration was mounting. Six-in-ten adults said in January 2022 that the changing guidance about how to slow the spread of the virus had made them feel confused , up from 53% the previous August. More than half said the shifting guidance had made them wonder if public health officials were withholding important information (57%) and made them less confident in these officials’ recommendations (56%). And only half of Americans said public health officials like those at the CDC were doing an excellent or good job responding to the outbreak, down from 60% last August and 79% in the early stages of the pandemic.

Economic concerns, particularly over rising consumer prices, were also clearly on the rise. Around nine-in-ten adults (89%) said in January that prices for food and consumer goods were worse than a year earlier . Around eight-in-ten said the same thing about gasoline prices (82%) and the cost of housing (79%). These assessments were shared across party lines and backed up by government data showing large cost increases for many consumer goods and services.

Overall, only 28% of adults described national economic conditions as excellent or good in January, and a similarly small share (27%) said they expected economic conditions to be better in a year . Strengthening the economy outranked all other issues when Americans were asked what they wanted Biden and Congress to focus on in the year ahead.

Looking at the bigger picture, nearly eight-in-ten Americans (78%) said in January that they were not satisfied with the way things were going in the country.

Imagining the new normal

As the third year of the U.S. coronavirus outbreak approaches, Americans increasingly appear willing to accept pandemic life as the new reality.

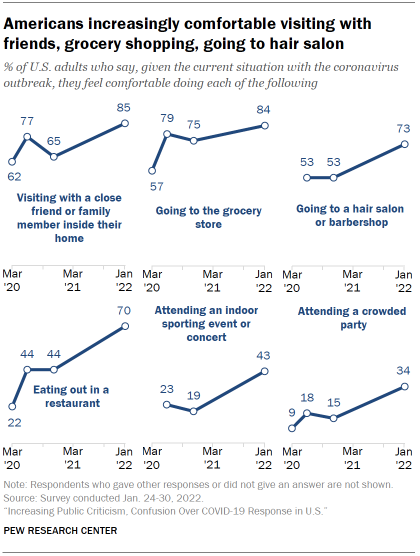

Large majorities of adults now say they are comfortable doing a variety of everyday activities , including visiting friends and family inside their home (85%), going to the grocery store (84%), going to a hair salon or barbershop (73%) and eating out in a restaurant (70%). Among those who have been working from home, a growing share say they would be comfortable returning to their office if it were to reopen soon.

With the delta and omicron variants fresh in mind, the public also seems to accept the possibility that regular booster shots may be necessary. In January, nearly two-thirds of adults who had received at least one vaccine dose (64%) said they would be willing to get a booster shot about every six months. The CDC has since published research showing that the effectiveness of boosters began to wane after four months during the omicron wave.

Despite these and other steps toward normalcy , uncertainty abounds in many other aspects of public life.

The pandemic has changed the way millions of Americans do their jobs, raising questions about the future of work. In January, 59% of employed Americans whose job duties could be performed remotely reported that they were still working from home all or most of the time. But unlike earlier in the pandemic, the majority of these workers said they were doing so by choice , not because their workplace was closed or unavailable.

A long-term shift toward remote work could have far-reaching societal implications, some good, some bad. Most of those who transitioned to remote work during the pandemic said in January that the change had made it easier for them to balance their work and personal lives, but most also said it had made them feel less connected to their co-workers.

The shift away from office spaces also could spell trouble for U.S. downtowns and the economies they sustain. An October 2021 survey found a decline in the share of Americans who said they preferred to live in a city and an increase in the share who preferred to live in a suburb. Earlier in 2021, a growing share of Americans said they preferred to live in a community where the houses are larger and farther apart , even if stores, schools and restaurants are farther away.

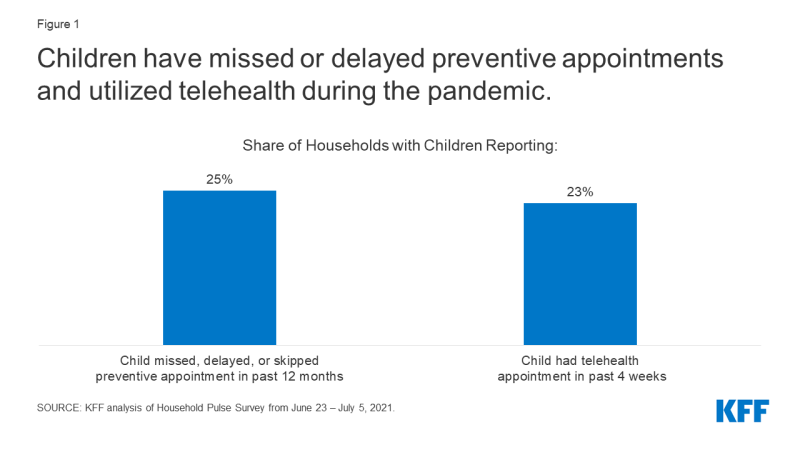

When it comes to keeping K-12 schools open, parental concerns about students’ academic progress and their emotional well-being now clearly outweigh concerns about kids and teachers being exposed to COVID-19. But disputes over school mask and vaccine rules have expanded into broader debates about public education , including the role parents should play in their children’s instruction. The Great Resignation has not spared K-12 schools , leaving many districts with shortages of teachers, bus drivers and other employees.

The turmoil in the labor market also could exacerbate long-standing inequities in American society. Among people with lower levels of education, women have left the labor force in greater numbers than men. Personal experiences at work and at home have also varied widely by race , ethnicity and household income level .

Looming over all of this uncertainty is the possibility that new variants of the coronavirus will emerge and undermine any collective sense of progress. Should that occur, will offices, schools and day care providers again close their doors, complicating life for working parents ? Will mask and vaccine mandates snap back into force? Will travel restrictions return? Will the economic recovery be interrupted? Will the pandemic remain a leading fault line in U.S. politics, particularly as the nation approaches a key midterm election?

The public, for its part, appears to recognize that a swift return to life as it was before the pandemic is unlikely. Even before the omicron variant tore through the country, a majority of Americans expected that it would be at least a year before their own lives would return to their pre-pandemic normal. That included one-in-five who predicted that their own lives would never get back to the way they were before COVID-19.

Lead photo: Luis Alvarez/Getty Images.

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

A Year After Coronavirus: An Inclusive ‘New Normal’

Six months into a new decade, 2020 has already been earmarked as ‘the worst’ year in the 21st century. The novel coronavirus has given rise to a global pandemic that has destabilized most institutional settings. While we live in times when humankind possesses the most advanced science and technology, a virus invisible to the naked eye has massively disrupted economies, healthcare, and education systems worldwide. This should serve as a reminder that as we keep making progress in science and research, humanity will continue to face challenges in the future, and it is upon us to prioritize those issues that are most relevant in the 21st century.

Even amidst the pandemic, Space X, an American aerospace manufacturer, managed to become the first private company to send humans to space. While this is a tremendous achievement and prepares humanity for a sustainable future, I feel there is a need to introspect the challenges that we are already facing. On the one hand, we seem to be preparing beyond the 21st century. On the other hand, heightened nationalism, increasing violence against marginalized communities and multidimensional inequalities across all sectors continue to act as barriers to growth for most individuals across the globe. COVID-19 has reinforced these multifaceted economic, social and cultural inequalities wherein those in situations of vulnerability have found it increasingly difficult to get quality medical attention, access to quality education, and have witnessed increased domestic violence while being confined to their homes.

Given the coronavirus’s current situation, some households have also had time to introspect on gender roles and stereotypes. For instance, women are expected to carry out unpaid care work like cooking, cleaning, and looking after the family. There is no valid reason to believe that women ought to carry out these activities, and men have no role in contributing to household chores. With men having shared household chores during the lockdown period, it gives hope that they will realize the burden that women have been bearing for past decades and will continue sharing responsibilities. However, it would be naïve to believe that gender discrimination could be tackled so easily, and men would give up on their decades' old habits within a couple of months. Thus, during and after the pandemic, there is an urgent need to sensitize households on the importance of gender equality and social cohesion.

Moving forward, developing quality healthcare systems that are affordable and accessible to all should be the primary objective for all governments. This can be done by increasing expenditure towards health and education and simultaneously reducing expenditure on defence equipment where the latter mainly gives rise to an idea that countries need to be prepared for violence. There is substantial evidence that increased investment in health and education is beneficial in the long-term and can potentially build the basic foundation of a country.

If it can be established that usage of nuclear weapons, violence and war are not solutions to any problem, governments (like, for example, Costa Rica) could move towards disarmament of weapons and do their part in building a more peaceful planet that is sustainable for the future. This would further promote global citizenship wherein nationality, race, gender, caste, and other categories, are just mere variables and they do not become identities of individuals that restrict their thought process. The aim should be to build responsible citizens who play an active role in their society and work collectively in helping develop a planet that is well-governed, inclusive, and environmentally sustainable.

‘A year after Coronavirus’ is still an unknown, so I think that our immediate focus should be to tackle the complex problems that have emerged from the pandemic so that we make the year after coronavirus one which highlights recovery and acts as a pathway to fresh beginnings. While there is little to gain from such a fatal cause, it is vital that we also use it to make the ‘new normal’ in favour of the environment and ensure that no one is left behind.

Related items

- Country page: India

- UNESCO Office in New Delhi

- SDG: SDG 3 - Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages

This article is related to the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals .

Article Terms of Reference: Development of O3 & ESA Commitment Live Indicator Dashboard 29 August 2024

Other recent articles

Article Terms of Reference for the development of an electronic health database for campus health facilities in Zimbabwe 23 July 2024

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Policy

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About Policy and Society

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Coronavirus disease as a catalyst for change: an early arrival of the future of work, the differential impact of coronavirus disease on the labor market, coronavirus disease and wlb: a mixed picture, forecasting key trends for the labor market and wlb, discussion and conclusion, conflict of interest.

- < Previous

“New normal” at work in a post-COVID world: work–life balance and labor markets

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Lina Vyas, “New normal” at work in a post-COVID world: work–life balance and labor markets, Policy and Society , Volume 41, Issue 1, March 2022, Pages 155–167, https://doi.org/10.1093/polsoc/puab011

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The coronavirus pandemic has interrupted labor markets, triggering massive and instant series of experimentations with flexible work arrangements, and new relationships to centralized working environments. These approaches have laid the basis for the “new normal,” likely extending into the organization of work in the post-pandemic era. These new arrangements, especially flexible work arrangements, have challenged traditional relationships with employees and employers, work time and working hours, the work–life balance (WLB), and the relationship of individuals to work. This paper investigates how labor markets have been interrupted due to the pandemic, focusing especially on manual (blue-collar) and nonmanual (white-collar) work and the future of the WLB, along with exploring the projected deviations that are driving a foreseeable future policy revolution in work and employment. This paper argues that although hybrid and remote working would be more popular in the post-pandemic for nonmanual work, it will not be “one size fits all” solution. Traditional work practices will remain, and offices will not completely disappear. Manual labor will continue current work practices with increased demands. Employers’ attention to employees’ WLB in the new normal will target employees’ motivation and achieving better WLB. These trends for the labor market and WLB are classified into three categories—those that are predicated on changes that were already underway but were accelerated with arrival of the pandemic (“acceleration”); those that represent normalization of what were once considered avant-garde ways of work (“normalization”); and those that represent modification or alteration of pre-pandemic set-up (“remodelling”).

Technological, social, and political transformations are powerful forces that radically shape many aspects of our lives, including the world of work, where societies are often forced to take proactive steps to adapt in order to remain competitive and survive. One notable example is the Industrial Revolution, which reshaped societies and economies in lasting ways and drastically changed the way people work, live, and establish a work–life balance (WLB). The ongoing coronavirus disease pandemic is similarly producing fundamental changes in work, work practices, the relationship of workers to co-workers, companies, and localities, as well as WLB. As part of the ongoing efforts to reduce the transmission of coronavirus disease and help protect the health and safety of employees, public and private organizations have generally adopted remote work arrangements, social distancing measures, staggered working hours, and other methods to reduce the presence of employees within work environments while also sustaining organizational activities ( International Labour Organization [ILO], 2020a ; World Health Organization [WHO], 2020 ).

While such practices are now widespread, they have not been uniform, varying between countries not only in terms of the intensity of their adoption and practice, but also in terms of their application across labor markets. For example, white-collar office workers, or those engaged in activities associated with mental work, have enjoyed the health protections of remote work options, while those engaged in physical work activities (consumer and business services, manufacturing, assembly, transportation, and related activities) have had to maintain their physical presence at work, often exposing them to greater health risks ( ILO, 2020c ).

Post-pandemic recovery must address the interruptions in the labor markets around the world, interruptions that have given rise to numerous experimentations with remote work, flexible work arrangements, and new relationships to centralized working environments. However, as far as the long-run diagnosis is concerned, there is a debate on whether coronavirus disease is a unique devastation, after which the work environment will return back to its “old normal” pre-coronavirus disease state, or whether the world is undergoing a sweeping disruption that will give rise to a “new normal,” with researchers and governments speculating about a complete series of different “new normal” future states of the world. Such changes bring up a discussion on what the new normal would be like and what can be foreseen in the post-pandemic world, particularly in the world of work. Therefore, this paper investigates the “new normal” in terms of two key themes—the labor market and WLB. The paper looks at how coronavirus disease has impacted work and the resultant effect on the labor market and WLB currently and in the future (see Figure 1 ). The labor market is explored in terms of the divaricate pathways between blue-collar and nonmanual workers.

Coronavirus pandemic and the labor market.

The goal of this paper is twofold. First, the paper attempts to clarify how coronavirus disease has been a mechanism for change in how work is conducted. The intention is to examine both positive and negative impacts of coronavirus disease on the labor market and WLB. Second, the paper sketches or maps forward an image of the post-coronavirus disease “new normal”, the likely composition of the future labor market, and what WLB might look like, highlighting possible trends and directions. These trends can be classified into one or more of three categories: acceleration, normalization, and remodelling. Acceleration represents those developments that were already underway in the work-world but were thrust onto a higher trajectory because of the unique conditions of the pandemic. Normalization represents the widespread acceptance and adoption of those practices that were once considered to be the exclusive preserve of a few or considered to be novel and rarely used. Remodelling refers to a modification or alteration of the existing pre-COVID set-up in line with the changes ushered in by the pandemic.

This paper is structured in the following manner: it begins with a description of the changes catalyzed by the pandemic in the labor market and with respect to WLB. It then forecasts seven key trends for these. This is followed by a conclusion.

Emergencies are frequently regarded as catalysts for change. The recent coronavirus disease pandemic is no exception. Many policy changes have been initiated to cope with the challenges that accompanied the crisis. While many welcomed the changes in the labor market, others regard them as emergency-induced changes—as something we should not be too positive about. Recalling pre-pandemic life, for decades working in an assigned workspace has been a standard pattern of work in many countries, while conversely, before the pandemic struck, work from home (WFH) was considered as a privilege for certain employees. The ongoing pandemic has become an unexpected catalyst for remote work and forced a reconsideration of work in terms of the designated workplace location and workplace practices ( de Lucas Ancillo et al., 2020 ; Kniffin et al., 2021 ; Ratten, 2020 ; Savić, 2020 ) on a global scale never seen before. It is worth pointing out that many of workers worldwide had never worked from home before. Although there was a slow but gradual increase in the number of remote workers before the pandemic, the world of work has fundamentally changed because of the coronavirus disease pandemic: WFH in pyjamas has become commonplace, and meeting virtually is increasingly mainstream.

In the days when severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) swept across the globe in 2003, home working was not an option for most workers worldwide, as the majority of them did not have access to essential devices and equipment to carry out their work at home. This is quite different from working in the current coronavirus disease pandemic era, with technology now providing more options for work practices. In Hong Kong, for example, WFH was not an option for the workforce during SARS ( Labour Department, 2003 ). However, in the midst of the ongoing coronavirus disease pandemic, such work arrangements were adjusted based on the severity of the local epidemic situation ( Vyas & Butakhieo, 2021 ). Now more than a year into the pandemic, companies worldwide are still pondering the workplace practice that best suits their own needs, and there is no doubt that the lively debate on remote working will continue. Yet this trial run of remote working has shed some light on the future of the workplace, ranging from the telework capacity of the economy to the public attitudes toward remote working. All this is owing to the pandemic as an impetus for a massive and unprecedented change. The pandemic is causing an early arrival of the future of work that was initially envisioned by policymakers around the world.

The pandemic has affected occupations and segments of the labor market differentially ( ILO, 2020b ). White-collar workers in particular have been affected by the pandemic, experiencing significant changes in working practices. WFH arrangements have been widespread, with various repercussions in terms of productivity, locality, working hours, and the traditional separation of work and home environments ( Caringal-Go et al., 2021 ; Wong et al., 2021 ). Typically, the home environment is one that allows the stresses of work to melt away, and permits workers to enjoy time with family separated from work pressures or activities. The conversion of the home environment into a work environment has tended to corrupt the sanctity of the home, with job-related issues fusing into the home and time previously free of work. Firmly demarcated work hours (which begin and end with arriving at and departing from a physical workplace) have disappeared, making it easy to carry on working out of hours and disrupt the home life and WLB.

By contrast, work and work conditions for blue-collar workers have largely remained unchanged outside of social distancing, sanitation, and related health measures. However, the focus here must not be on how the job has changed, but rather on the implications of continuing to work through the pandemic. Blue-collar workers have been forced to brave the health dangers of continued social contact, risking sickness with every interaction. The demands of the jobs would mean that those more vulnerable than others have no alternative safer option: For these workers, sitting at home means being unable to work, which incurs financial strain. Additionally, continuing to work outside the home may cause tension at home due to the workers being at risk of bringing the virus back and infecting loved ones. Both white-collar and blue-collar workers have been impacted; however, their work practices have changed in different ways because of the pandemic.

Having a harmonious balance between work and personal life (i.e., a good WLB) is critical to bringing a healthy and stress-free environment and allowing employees to unleash their full potential. However, striking a good WLB is a challenge for most workers, more so for those with caregiving responsibilities, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is also believed that creating a flexible and family-friendly workplace (e.g., having flexible work hours or offering remote work) can help to improve the well-being of the workforce ( Feeney & Stritch, 2019 ; Shagvaliyeva & Yazdanifard, 2014 ).

Many workers now work from their “workspace” of choice which includes home, office, and co-working spaces (depending on the work tasks they are entrusted with). Workers may thereby see better outcomes for their health, family, and overall well-being. While many have adjusted to and enjoyed this change, others have had challenges in drawing a line between working and non-working hours. The likelihood is high for a number of employees to experience increased working hours, as well as increased work-life conflict. For example, in today’s hyper-connected world, many remote working employees are expected to respond to urgent tasks as well as after-work emails, resulting in a blur between work and leisure. A recent study revealed that employees WFH during the pandemic experienced an increase in work-related fatigue and overlap between work and non-work life ( Palumbo, 2020 ).

Indeed, different scholars have different views on the impact of remote working on the WLB of workers. Some believe that WFH has positive impact on the WLB ( Pelta, 2020 ). On the contrary, there are adverse effects found in studies where a blur between work life and personal life is visible and it seems that home-based working may negatively impact WLB ( Grant et al., 2019 ; Nakrošienė & Butkevičienė, 2016 ; Palumbo et al., 2020 ). Putri and Amran (2021) studied the effect of WFH during the coronavirus disease on the WLB of employees in Indonesia and found that it had a positive impact. However, employees often are not able to balance their work and personal time as their working environment might be flexible, but their hours are increased. It has also been found that working from home or working remotely at least 1 day a week gave employees a better WLB ( BBC News, 2021a ). The trend seems to favor hybrid working over a completely remote working environment.

The paper flags seven key trends that will manifest themselves in the future. First, accelerating digital transformation will become critical for the workplace. Second, hybrid work would be a new normal at work in the post-pandemic era. Despite this, some work practices will not be eliminated. Thus, the third trend will be the continued existence of the “office” albeit in a modified form. Fourth, all of the above will induce changes in organizational infrastructure and labor mobility. Fifth, the challenges of performance management and atomistic tendencies at work may arise. Sixth, there may be a potential exacerbation of existing inequalities. Seventh, there will be increased focus on WLB in the future.

Of the aforementioned trends, some are predicated on changes that were already underway but were accelerated with the advent of the pandemic (“acceleration”). Other trends represent the normalization of what were once considered avant-garde ways of work (“normalisation”). Yet other trends represent a remodelling of the status-quo (“remodelling”). And some trends represent a combination of two or more of the above ( Table 1 ).

Forecasting key trends in the labor market and WLB.

| . | Acceleration . | Normalization . | Remodelling . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accelerated digital transformation | X | ||

| Emergence of hybrid work | X | X | |

| The continued existence of the “office” | X | ||

| Changes in organizational infrastructure and labor mobility | X | X | X |

| The challenges of performance management and atomistic tendencies at work | X | X | |

| Potential exacerbation of existing inequalities | X | X | |

| Managing work–life balance | X | X |

| . | Acceleration . | Normalization . | Remodelling . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accelerated digital transformation | X | ||

| Emergence of hybrid work | X | X | |

| The continued existence of the “office” | X | ||

| Changes in organizational infrastructure and labor mobility | X | X | X |

| The challenges of performance management and atomistic tendencies at work | X | X | |

| Potential exacerbation of existing inequalities | X | X | |

| Managing work–life balance | X | X |

Accelerated digital transformation

Changes in the labor markets to keep businesses running are inevitable in the post-pandemic era, and technological adoption is the most visible change in the labor market. It has been shown that digital technology was adopted in organizations prior to the emergence of the pandemic, and this adoption was accelerated during the pandemic ( Forman & van Zeebroeck, 2019 ; Murdoch & Fichter, 2017 ; Vargo et al., 2021 ). The pandemic has thus triggered a shift to a more digital society—or, to be more precise, the real world is gradually dying out, and the fast-paced technological world is rapidly replacing the old one. Digital transformation has, therefore, become an imperative for businesses across industries of all sizes for survival, and adequate digital infrastructure is essential for working in the future ( Gadhi, 2020 ; Melhem et al., 2020 ). The world of work is therefore heading a new way, in line with the changes in the business world. Thus, it could be said that digital and technological enhancements and transformations have an impact on several types of work. Nonmanual work, for example, would benefit more from this enhancement than manual labor, which requires on-site work. Employees with a high capability to work remotely will possibly have a reduced risk of perishing in the future labor market.

Digital technologies and the emergence of the coronavirus disease pandemic could be considered the most critical elements for accelerating the growth of remote working. Other factors, such as the pandemic-driven recession and the geopolitical contest between countries, are causing uncertainty in the future labor market outlook. The post-pandemic times will bring along a possible risk and challenge to organizational sustainability and human resource management.

Emergence of hybrid work

It is anticipated that the world of work will undergo a significant shift toward hybrid work in the post-coronavirus disease world, making hybrid working to some extent the “new normal” at work ( Ro, 2020 ). This is particularly likely for the highly educated and well-paid faction of the workforce. The potential of adopting remote work largely depends on whether a job has tasks and activities which do not require workers to be physically present on-site to get the work done ( Lund et al., 2020 ). Professions requiring in-person involvement such as agricultural work, restaurant, and hotel services are not able to adopt remote working ( Dingel & Neiman, 2020 ). In other words, the adoption of “new normal” work practices—remote working and WFH—will depend on the nature of the work, because not all tasks can be accomplished remotely. Given that, it would require significant rethinking about which jobs are suitable to perform remotely. In the long run, hybrid working has to be thoughtful and granular.

Well into the pandemic, the limitations and merits of remote work are more visible, and this give us reason to believe it will become a part of the future. Employees who WFH have higher flexibility and can adjust their working hours in line with their personal and family needs. While some people are returning to the workplace as many restrictions are being lifted, there are some pandemic-driven practices like hybrid work, WFH, remote work, flexible workplace/worktime, work anywhere, and work near home that persist. Businesses around the world will most likely continue to use them, particularly white-collar jobs. For example, two out of three white-collar workers in Hong Kong still want to WFH, and companies are considering redesigning office space to accommodate hybrid work ( Lam, 2021 ). Several examples around the world, including the BP oil company, have decided to implement a new hybrid model that will enable workers to WFH 2 days a week ( Ambrose, 2021 ). Another example is the nationwide decision in England to allow white-collar workers to work from anywhere, giving them more control over their lives ( BBC News, 2021a ). Some of the world’s most well-known firms, including Amazon, Apple, Google, Facebook, British Airways, Microsoft, and Siemens AG, are inclined to adopt remote working in post-pandemic times ( BBC News, 2020 ; Hartmans, 2020 ; Siemens AG, 2020 ). All the aforementioned examples involve nonmanual work, and it seems very likely that these companies will be willing to embrace remote working in the post-pandemic period.

Additionally, people working in global teams, particularly with white-collar jobs, have further endorsed the feasibility of flexible work that includes WFH and is not confined by standard business hours. The results of multiple surveys conducted around the world prove consistent with each other, suggesting that after coronavirus disease recedes, quite a number of office employees, regardless of nationality or race, would prefer to work remotely at least some days ( Kelly, 2021 ; PWC, 2021 ; Wong & Cheung, 2020 ).

The continued existence of the “office”

Previous studies have revealed that remote working can enhance productivity (e.g., Bloom et al., 2015 ; Grant et al., 2013 , 2019 ). However, it has been argued by scholars that working remotely amidst the pandemic has had both positive and negative impacts on productivity. On the one hand, some employees thought they were more productive when working from home because a flexible working arrangement allows them to manage their working time and place on their own. On the other hand, other employees experienced a difficulty in getting work done at home, caused by the interruption of family members and/or children at home ( Gibbs et al., 2021 ; Mustajab et al., 2020 ; Parker et al., 2020 ).

In a similar manner, several employees with either manual or nonmanual jobs believe that WFH is not the right fit for them. Manual types of work may not be able to adopt WFH due to the nature of the work. Some nonmanual workers prefer returning to the workplace after the pandemic. Working in an office can be more beneficial than working at home in terms of generating new ideas and socialising, and new employees can benefit from working in an office by learning about the organization and its culture ( BBC News, 2021d ; Vasel, 2021 ). WFH can keep new employees from gaining such knowledge. Employees also seem likely to resign if they are required to WFH full time and are not permitted to work in an office ( BBC News, 2021c ). Accordingly, traditional work practices, such as working in an office, are still needed.

Changes in organizational infrastructure and labor mobility

Businesses worldwide are seeing the merits of WFH or hybrid work, including but not limited to having a larger talent pool and saving money on rent ( de Lucas Ancillo et al., 2020 ). This will drive the recovering economy to rethink the need for office space, especially for nonmanual work types, with some companies considering reducing their office space or relocating from high-cost cities (i.e., London, New York, Paris, Hong Kong, etc.) to a more affordable place, and some adapting to a completely virtual office environment. Others are evaluating the possibility of renting co-working spaces. Companies are taking advantage of the demand for hybrid work to save the cost of renting an office ( BBC News, 2021b ). In addition to the relocation of workplaces from major cities to cheaper places, it is also believed that there will be a radical transition in urban life, where remote-working employees will migrate out of business capitals to cities with more affordable rentals and living costs ( Lund et al., 2021 ), owing largely to the prevalence of remote working. Such a transition will boost the economy of the cities concerned as well as their surrounding areas.

The challenges of performance management and atomistic tendencies at work

The “new normal” work practice would impact certain businesses and individuals or even work itself. For example, working mothers will be able to reduce commuting time and have more time to take care of their children. However, some managers feel that they cannot manage employees who are working remotely. Expectations for working objectives and output are not clear, and it is difficult to know whether employees are actively working ( ILO, 2020b ). Apart from that, some organizations have found it is difficult to switch to remote working for several reasons, such as a lack of digitized paperwork, information confidentiality concerns, and the fact that some organizations do not yet have in place guidelines and procedures for remote working ( ILO, 2020c ). The potential impacts of remote work practices should be given careful attention: For example, technology-related problems take longer to resolve remotely than in an office where employees might have technical support. Remote workers may encounter this problem, and such a problem could disrupt the working environment and work productivity.

Digital miscommunication, which is a lack of informal interaction and human interaction, could also be one of the potential impacts of remote working. This miscommunication might shape a work design that is more individual- than team-based, and make co-workers’ interaction and team building even more difficult.

Potential exacerbation of existing inequalities

Given the adoption of more digital technology, automation, and artificial intelligence (AI), as well as the “new normal” work practice in the post-pandemic labor force, certain types of occupations could be adversely affected (see Figure 1 ). The least educated, unskilled, and low-skilled workers may be replaced by automation ( Lund et al., 2021 ). Vulnerable workers will likely be the hardest-hit group; some of them might have to work multiple jobs (probably freelance jobs) to sustain a living. It is likely further to exacerbate existing inequalities in the world of work, and therefore reskilling and upskilling will become more necessary than ever before. Similarly, jobs such as personal care, on-site customer service, and leisure and travel have been severely disturbed by the pandemic. Businesses and policymakers can help workers in workforce transitions by additional training and education programs For example, businesses might analyze which tasks can be done remotely instead of looking at an entire occupation and possibly eliminating it. Policymakers might facilitate businesses in terms of digital infrastructure enhancement ( Lund et al., 2021 ). Work-related policy changes that will protect and support businesses and workers, including enhancing employees’ WLB in the post-pandemic, are also essential. The future trend of the labor market will be a challenging time for everyone and the labor policies will need to be improved and strengthened in order to thrive in the post-coronavirus disease world.

Managing WLB

As the trend seems to favor hybrid working over a completely remote working environment, whole or partial renegotiation and reorganization will be essential. Managers and HR will have to accommodate the changes in organizational strategies as well as in HR policies. A study by Kumar and Mokashi (2020) on WLB in the UK’s higher education institutions employees revealed that supervisor support during coronavirus disease helped employees enhance their living quality. Similar to previous studies, it has been reemphasized in coronavirus disease times that supervisors’ or managers’ support can help employees achieve a good WLB ( Julien et al., 2011 ; Talukder & Galang, 2021 ; Talukder et al., 2018 ).

Alternatively, governments may opt to implement specific policies in this regard. One notable example would be to adopt the “right-to-disconnect” law similar to that which is enforced in the Philippines and France, where employees have the right not to respond to work-related engagements and demands during nonworking hours ( Broom, 2021 ; Department of Labor and Employment, Philippines, 2017 ; Eurofound, 2019 ). Encouraging healthy work practices such as working within regular hours and taking regular breaks will help employees to draw a firm line between work and nonwork activities ( Adamovic, 2018 ; Chen & Fulmer, 2018 ). Optimizing personal and work life is not easy when adopting a “new normal” working model. Employees need to be disciplined and well-organized in their work and personal life management. This global health crisis has made people pay more attention to health and hygiene, which has also driven up the demand for healthy workplace cultures. However, to attain a WLB in the post-coronavirus disease world, employers may need to consider and plan a way forward such as providing clarity to employees and a variety of programs to support employees in their well-being as well as fostering a “trust- and outcome-based working culture” ( Sarin, 2020 ; Wolor et al., 2020 ). Employers’ attention to employees’ WLB will assist in keeping employees motivated and maintaining their performance. Therefore, WLB in the post-pandemic times should be brought to both employers’ and employees’ attention and should be considered when developing a plan for policy changes that would benefit both companies and employees.

This paper explores how the coronavirus disease has disrupted the labor markets, focusing on blue-collar and nonmanual (white-collar) work, the future of the WLB, what the “new normal” would be like, and what can be foreseen in the post-pandemic. As evident, the pandemic has created a health crisis and a labor market alarm, and led to many changes, particularly in the working world. These changes either “accelerated” the pace of developments that were already underway, and/or are contributing to a “remodelling” of the pre-pandemic work-world and/or have contributed to the “normalization” of what were considered to be experimental and novel ways of work.

In seeking a possible working solution during such difficult times, “acceleration” is seen in the increased use of technology to enable remote working arrangement initially as a stopgap measure and followed by a hybrid manner of work, with the exception of professions that require a physical presence. Resulting in a significant “normalization” of these practices. While various work procedures and habits have been followed, there has been a wide variation in their use worldwide and across different professions in the labor market. Workers with high educational attainment and those who work as white-collar office workers have had the privilege of working in a safe and protected environment, while those who are engaged in manual and physical work engagement have braved challenges and continued to work under high risk.

Many white-collar workers that were forced to WFH as an emergency response to the pandemic did not receive additional support from their organizations. They survived using their limited personal resources while carrying out the job requirements. Many such employees acquired skills suitable to the future WLB policy, such as, get used to remote working, manage stress and productivity, and carefully splitting work and family time. In doing so workers were “remodeling” pre-pandemic work practices alongside “normalization” of news ways. In the future, such employees should be supported with WFH arrangements ever after the pandemic, with admission from their organizations. Employers have experimented on the feasibility of such work practices and are focusing more on cost saving and higher profitability. Although there remains a conflict between the expectations of employers and employees, On the whole, hybrid working and staying flexible is likely to be in demand and could be the “new normal” in the post-COVID period. In this case, businesses worldwide will need to proactively craft a long-term remote or hybrid work strategy based on their own needs, as there is no “one-size-fits-all” solution. Similarly, governments worldwide need to revisit the current employment policies to have strict and proper employment laws in place and assure fair employee treatment.

The changes in the labor policy framework dramatically impacted the inequalities, representing both “acceleration” and “remodelling”. The work-types for manual workers and nonmanual workers have undergone changes and made it clear that the economy must transform into retail, where it is driven by the needs of customers for the best possible level of service. Due to the nature of the work, a WFH arrangement cannot be utilized for those who need to be physically present to offer their services. Moreover, vulnerable employees (e.g., low-paid, low-skilled workers, persons with disabilities, and migrant workers) have been hit particularly hard by the pandemic. Many of them have been put on furlough since the early stages of the pandemic, leading some to consider making a living in the gig economy, as there seems to be little prospect soon of an end to the recession caused by the pandemic. However, jobs in the gig economy—for example, project-based jobs and independent contractual jobs—appear to have weaker protection and lesser benefits for workers ( United Nations, 2020 ). Furthermore, automation tends to replace the least educated, unskilled, and low-skill labor. As such, it has the potential to exacerbate existing inequities.

In light of the aforementioned changes in the labor market, the development of future WLB policies must include a spectrum of directions, such as customization of working hours under WFH, ensuring trust and support for WFH employees, responding to the demands to work from the office, and guaranteeing equal pay and the right to disconnect. Thus, policymakers must chart out a proper plan of action and consider not only jobs and groups of people but also when and which people can work remotely or on-site. According to Boland et al. (2020) , there are four steps to reimagine work and the workplace in the post-pandemic working world. First, how is work done in the post-pandemic working world? Organizations should restructure their working processes and functions to perform work: For example, workers may chart out tasks to be performed in the formal office environment versus those that could be taken care of in a remote setting. Second, once reconstructing their work processes and identifying the tasks that can be done remotely, organizations should consider segments of workers and reclassify roles to identify employees’ suitability for exclusively WFH or hybrid remote working and on-site working. Third, to maintain productivity and collaboration organizations should design workspaces that support workers both remotely and on-site, with tools such as virtual whiteboards and videoconferences. Lastly, some organizations may shift from a big city to a small city to save on their rental costs. Co-working spaces, flexible leases, flex space, and remote work seem to be examples of post-coronavirus disease options. These four steps—restructuring the working process, identifying tasks, redesigning workspaces, and relocating offices—will help organizations get some idea of how to prepare for and foresee the future of work and the workplace.

WLB should take a central development in labor policy in the post-pandemic working world. Balancing work and personal life is challenging both for employers and employees. Although previous studies have emphasized that remote work, WFH, or flexible workplaces can enhance employees’ WLB ( Pelta, 2020 ), WFH during the pandemic showed that some employees encountered an imbalance between work and personal/family life (see Figure 1 ). There is demand for giving people deserved “holidays” as due to hybrid digital working, as some employees have been working 24/7 without weekend breaks. People are being deprived of both their personal space and weekly time off as their work is “omnipresent” and one can access the office from anywhere on any device, be it a phone, laptop, iPad, or other tool. In contrast, some employees were able to enhance their WLB through a WFH arrangement, with things such as flexible working hours and having more time to take care of young children and/or elderly parents, and thus were more motivated. During this WFH period, some employees were able to achieve a good WLB while others were not.

The coronavirus disease pandemic has demanded adjustments and changes from the workers, who are in supervision and managers’ positions. Previous studies have found that supervisors influence employees’ WLB, with supervisor trust and support enhancing the WLB of employees ( Kumar & Mokashi, 2020 ; Talukder & Galang, 2021 ). Organizations and policymakers may need to consider how work is supervised and appraised in order to help supervisors trust employees and provide support to help employees achieve a WLB in the post-coronavirus disease world,. Also, the importance of a workplace productivity culture should be better defined by the managers so that workers can choose to work within or outside of the formal work environment without any negative repercussions. For instance, in European countries some regulations and policies related to WLB and flexible work practices, such as the “right to disconnect”, promote teleworkers’ WLB such that workers can opt whether to work or not outside of working hours ( Eurofound, 2020 ). Hence, to help employees achieve their WLB in the post-pandemic world, organizations and policymakers might consider an emphasis on:

Allowing employees to customize their work commitment and working hours and thus make WFH employees motivated and productive;

Trust and support WFH employees to help them reduce stress (which may also lead to an increase in productivity and work commitment);

Enhancing work motivation and employees’ well-being, understand that some employees may be willing to WFH and others prefer to be in an office;

Guaranteeing employees both equal pay for remote working and the right to disconnect;

Reconstructing how work is done, and identify which work can be performed remotely and which requires an onsite work environment.

Although remote working is an important trend in the post-pandemic world, many crucial issues in terms of the well-being of remote employees, national laws and regulations, and cyber-security risks require monitoring and further solutions. Therefore, relevant parties at all levels of society, including policymakers and businesses, must work together to create a more sustainable model for “new normal” work practices.

Fundamental changes should apply to labor policy. How governments address the “new normal” of remote and hybrid working will affect both the WLB and workplace inequalities and abuse. It is essential to have policies that encourage employee protection and well-being. To sum up, the pandemic has awakened countless speculations, assumptions, and debates on what the impending labor market will look like. coronavirus disease has given rise to transformation, interruption, endurance, and ambiguity. Studying the post-pandemic paths, as they take the form of “acceleration,” “normalization,” and “remodelling.” is vital in anticipating the connection between workplace disruptions and a pathway to a “new normal.”

The research was supported by a “Departmental Small Research Grant” funded by Department of Asian and Policy Studies, Faculty of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences, The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

None declared.

Adamovic M. ( 2018 ). An employee-focused human resource management perspective for the management of global virtual teams . The International Journal of Human Resource Management , 29 ( 14 ), 2159 – 2187 . https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1323227 .

Google Scholar

Ambrose J. ( 2021 , March 8 ). BP to tell 25,000 office staff to work from home two days a week . The Guardian . https://www.theguardian.com/business/2021/mar/08/bp-to-tell-25000-office-staff-to-work-from-home-two-days-a-week .

BBC News . ( 2020 , October 9 ). Microsoft makes remote work option permanent . BBC . https://www.bbc.com/news/business–54482245 .

BBC News . ( 2021a , March 25 ). Nationwide tells 13,000 staff to ‘work anywhere’ . BBC . https://www.bbc.com/news/business–56510574 .

BBC News . ( 2021b , March 9 ). Hybrid working will become the norm . BBC . https://www.bbc.com/news/business–56331654 .

BBC News . ( 2021c , March 26 ). People may quit if forced to work from home, Rishi Sunak warns . BBC . https://www.bbc.com/news/business–56535575 .

BBC News . ( 2021d , March 1 ). Covid: ‘People are tired of working from home’ . BBC . https://www.bbc.com/news/business–56237586 .

Bloom N. , Liang J. , Roberts J. , & Ying Z. J. ( 2015 ). Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment . The Quarterly Journal of Economics , 130 ( 1 ), 165 – 218 .

Boland B. , De Smet A. , Palter R. , & Sanghvi A. ( 2020 ). Reimagining the office and work life after COVID-19 . McKinsey & Company . https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/reimagining-the-office-and-work-life-after-covid-19 .

Broom D. ( 2021 , March 5 ). Is it time remote workers are given the ‘right to disconnect’ while at home? World Economic Forum . https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/03/right-to-disconnect-from-work-at-home-eu/ .

Caringal-Go J. F. , Teng-Calleja M. , Bertulfo D. J. , & Manaois J. O. ( 2021 ). Work-life balance crafting during COVID-19: Exploring strategies of telecommuting employees in the Philippines . Community, Work & Family , 1 – 20 , pre-publication issue. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2021.1956880 .

Chen Y. , & Fulmer I. S. ( 2018 ). Fine-tuning what we know about employees’ experience with flexible work arrangements and their job attitudes . Human Resource Management , 57 ( 1 ), 381 – 395 . https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21849 .

de Lucas Ancillo A. , del Val Núñez M. T. , & Gavrila S. G. ( 2020 ). Workplace change within the COVID-19 context: A grounded theory approach . Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja , 34 (1), 2297 – 2231 . https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2020.1862689 .

Department of Labor and Employment, Philippines . ( 2017 , February 1 ). Bello: ‘Right to disconnect’ after office hours choice of employees . Department of Labor and Employment. GOV.PH . https://www.dole.gov.ph/news/bello-right-to-disconnect-after-office-hours-choice-of-employees/ .

Dingel J. I. , & Neiman B. ( 2020 ). How many jobs can be done at home? Journal of Public Economics , 189 , 104235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104235 .

Eurofound . ( 2019 , October 22 ). Right to disconnect . European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions . https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/observatories/eurwork/industrial-relations-dictionary/right-to-disconnect .

Eurofound . ( 2020 ). Regulations to address work–life balance in digital flexible working arrangements . New Forms of Employment Series, Publications Office of the European Union . https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_publication/field_ef_document/ef19046en.pdf .

Feeney M. K. , & Stritch J. M. ( 2019 ). Family-friendly policies, gender, and work–life balance in the public sector . Review of Public Personnel Administration , 39 ( 3 ), 422 – 448 . https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X17733789 .

Forman C. , & van Zeebroeck N. ( 2019 ). Digital technology adoption and knowledge flows within firms: Can the Internet overcome geographic and technological distance? Research Policy , 48 ( 8 ), 103697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.10.021 .

Gadhi S. ( 2020 , April 1 ). How digital infrastructure can help us through the COVID-19 crisis . World Economic Forum . https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/digital-infrastructure-public-health-crisis-covid–19/ .

Gibbs M. , Mengel F. , & Siemroth C. ( 2021 , May 11). Work from home & productivity: Evidence from personnel & analytics data on IT professionals . University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper, 2021–2056 . http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3843197 .

Grant C. , Wallace L. , & Spurgeon P. ( 2013 ). An exploration of the psychological factors affecting remote e-worker’s job effectiveness, well-being and work-life balance . Employee Relations , 35 ( 5 ), 527 – 546 . https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-08-2012-0059 .

Grant C. A. , Wallace L. M. , Spurgeon P. C. , Tramontano C. , & Charalampous M. ( 2019 ). Construction and initial validation of the E-Work Life Scale to measure remote e-working . Employee Relations , 41 ( 1 ), 16 – 33 . https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-09-2017-0229 .

Hartmans A. ( 2020 , December 15 ). Google just delayed its office reopening until September 2021. Here’s how other major Silicon Valley companies are thinking about the future of work . https://www.businessinsider.com/silicon-valley-future-of-work-port-coronavirus-apple-amazon-facebook-2020-10?r=US&IR=T .

International Labour Organization . ( 2020a , March 18 ). COVID-19 and the world of work: Impact and policy responses . ILO . https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_738753.pdf .

International Labour Organization . ( 2020b , May 27 ). ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work. Fourth edition . https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_745963.pdf .

International Labour Organization . ( 2020c ). An employer’s guide on working from home in response to the outbreak of COVID-19 . International Labour Office . https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_dialogue/---act_emp/documents/publication/wcms_745024.pdf .

Julien M. , Somerville K. , & Culp N. ( 2011 ). Going beyond the work arrangement: The crucial role of supervisor support . Public Administration Quarterly , 35 ( 2 ), 167 – 204 .

Kelly J. ( 2021 , May 21 ). Survey asks employees at top U.S. companies if they’d give up $30,000 to work from home: The answers may surprise you . Forbes . https://www.forbes.com/sites/jackkelly/2021/05/21/survey-asks-employees-at-top-us-companies-if-theyd-give-up-30000-to-work-from-home-the-answers-may-surprise-you/?sh=1328144330f8 .

Kniffin K. M. , Narayanan J. , Anseel F. , Antonakis J. , Ashford S. P. , Bakker A. B. , Bamberger P. , Bapuji H. , Bhave D. P. , Choi V. K. , Creary S. J. , Demerouti E. , Flynn F. J. , Gelfand M. J. , Greer L. L. , Johns G. , Kesebir S. , Klein P. G. , Lee S. Y. , … Vugt M. V. ( 2021 ). COVID-19 and the workplace: Implications, issues, and insights for future research and action . American Psychologist , 76 ( 1 ), 63 – 77 . https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000716 .

Kumar R. , & Mokashi U. M. ( 2020 ). COVID-19 and work-life balance: What about supervisor support and employee proactiveness? Annals of Contemporary Developments in Management & HR (ACDMHR) , 2 ( 4 ), 1 – 9 .

Labour Department . ( 2003 , November ). Guidelines for employers and employees: Prevention of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS ) . HKSAR . https://www.info.gov.hk/info/sars/lft/employ_e.htm .

Lam K.-S. ( 2021 , April 21 ). Two of three Hong Kong office staff want to keep working from home, boding ill for demand in the world’s most expensive office market . South China Morning Post . https://www.scmp.com/business/article/3130267/two-three-hong-kong-office-staff-want-keep-working-home-boding-ill-demand .

Lund S. , Madgavkar A. , Manyika J. , & Smit S. ( 2020 , November 23 ). What’s next for remote work: An analysis of 2,000 tasks, 800 jobs, and nine countries . McKinsey & Company . https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/whats-next-for-remote-work-an-analysis-of-2000-tasks-800-jobs-and-nine-countries .

Lund S. , Madgavkar A. , Manyika J. , Smit S. , Ellingrud K. , Meaney M. , & Robinson O. ( 2021 , February 18 ). The future of work after COVID-19 . McKinsey Global Institute . https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/the-future-of-work-after-covid–19 .

Melhem M. , Lawal M. , & Bashir S. ( 2020 , June 12 ). Enhancing digital capabilities in a post-COVID-19 world . World Bank . https://blogs.worldbank.org/digital-development/enhancing-digital-capabilities-post-covid-19-world .

Murdoch D. , & Fichter R. ( 2017 ). From doing digital to being digital: Exploring workplace adoption of technology in the age of digital disruption . International Journal of Adult Vocational Education and Technology (IJAVET) , 8 ( 4 ), 13 – 28 . https://doi.org/10.4018/IJAVET.2017100102 .

Mustajab D. , Bauw A. , Rasyid A. , Irawan A. , Akbar M. A. , & Hamid M. A. ( 2020 ). Working from home phenomenon as an effort to prevent COVID-19 attacks and its impacts on work productivity . TIJAB (The International Journal of Applied Business) , 4 ( 1 ), 13 – 21 .

Nakrošienė A. , & Butkevičienė E. ( 2016 ). Nuotolinis darbas Lietuvoje: Samprata, privalumai ir iššūkiai darbuotojams . Filosofija. Sociologija , 27 ( 4 ), 364 – 372 .

Palumbo R. ( 2020 ). Let me go to the office! An investigation into the side effects of working from home on work-life balance . International Journal of Public Sector Management , 33 ( 6/7 ), 771 – 790 . https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-06-2020-0150 .

Palumbo R. , Manna R. , & Cavallone M. ( 2020 ). Beware of side effects on quality! Investigating the implications of home working on work-life balance in educational services . The TQM Journal , pre-publication issue. https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-05-2020-0120 .

Parker K. , Juliana Menasce Horowitz J. M. , & Minkin R. ( 2020 , December 9 ). How the coronavirus outbreak has—and hasn’t—changed the way Americans work . Pew Research Center . https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2020/12/09/how-the-coronavirus-outbreak-has-and-hasnt-changed-the-way-americans-work/ .

Pelta R. ( 2020 , September 21 ). FlexJobs Survey: Productivity, work-life balance improves during pandemic . Flexjobs . https://www.flexjobs.com/blog/post/survey-productivity-balance-improve-during-pandemic-remote-work/ .

Putri A. , & Amran A. ( 2021 ). Employees’ work-life balance reviewed from work from home aspect during COVID-19 pandemic . International Journal of Management Science and Information Technology , 1 ( 1 ), 30 – 34 .

PWC . ( 2021 , January 12 ). It’s time to reimagine where and how work will get done . PWC . https://www.pwc.com/us/en/library/covid-19/us-remote-work-survey.html .

Ratten V. ( 2020 ). Coronavirus (COVID-19) and entrepreneurship: Changing life and work landscape . Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship , 32 ( 5 ), 503 – 516 .

Ro C. ( 2020 , August 31 ). Companies are looking to the post-Covid future. For many, the vision is a model that combines remote work and office time . BBC Worklife . https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20200824-why-the-future-of-work-might-be-hybrid .

Sarin B. ( 2020 , December 25 ). The work-life post-COVID-19: From collision to integration . People Matters Pte. Ltd . https://www.peoplemattersglobal.com/article/life-at-work/the-work-life-post-covid-19-from-collision-to-integration–27979 .

Savić D. ( 2020 ). COVID-19 and work from home: Digital transformation of the workforce . Grey Journal (TGJ) , 16 ( 2 ), 101 – 104 .

Shagvaliyeva S. , & Yazdanifard R. ( 2014 ). Impact of flexible working hours on work-life balance . American Journal of Industrial and Business Management , 4 ( 1 ), 20 – 23 .

Siemens AG . ( 2020 , July 16 ). Siemens to establish mobile working as core component of the ‘new normal’ . https://press.siemens.com/global/en/pressrelease/siemens-establish-mobile-working-core-component-new-normal .