- DOI: 10.1016/J.RTBM.2020.100529

- Corpus ID: 225007811

Competition for rail transport services in duopoly market: Case study of China Railway(CR) Express in Chengdu and Chongqing

- Yitong Ma , Daniel Johnson , +1 author Xianliang Shi

- Published 30 September 2020

- Economics, Engineering, Business, Geography

- Research in transportation business and management

14 Citations

Modeling government subsidy strategies for railway carriers: environmental impacts and industry competition, impact of china railway express on regional resource mismatch—empirical evidence from china, new canal construction and marine emissions strategy: a case of pinglu, comparative analysis of long-distance transportation with the example of sea and rail transport, isolated territories and infrastructure development: a case for land transportation investment in madagascar, roads or railways a case study of madagascar, how would co-opetition with dry ports affect seaports’ adaptation to disasters, unintended environmental gains: the impact of china-europe railway express on carbon dioxide emissions in china, toward a positive compensation policy for rail transport via mechanism design: the case of china railway express, time is money: impact of china-europe railway express on the export of laptop products from chongqing to europe, 29 references, a study on the government subsidies for cr express based on dynamic games of incomplete information, hinterland patterns of china railway (cr) express in china under the belt and road initiative: a preliminary analysis, impact of rail transport services on port competition based on a spatial duopoly model, on service network improvement for shipping lines under the one belt one road initiative of china, evaluation of consolidation center cargo capacity and loctions for china railway express, development of port service network in obor via capacity sharing: an idea from zhejiang province in china, serial and parallel duopoly competition in multi-segment transportation routes, a game theoretical approach to competition between multi-user terminals: the impact of dedicated terminals, the impact on port competition of the integration of port and inland transport services, impact of the carat canal on the evolution of hub ports under china’s belt and road initiative, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

- View Record

TRID the TRIS and ITRD database

Competition for rail transport services in duopoly market: Case study of China Railway(CR) Express in Chengdu and Chongqing

Known as the Belt and Road Initiative, China Railway(CR) Express is driving China's efforts to boost connectivity and explore regional cooperation with Eurasian markets. In order to investigate the fierce hinterland competition between two neighbouring CR Express lines, this paper first formulates a non-cooperative game model to explore strategic decisions on pricing accounting for competition in a spatial setting, given frequency, government subsidy, local road infrastructure investment, and operation costs. The authors then extend the model to analyze decisions on frequency and pricing together, and the implications for social welfare, profits and market share as well. Based on a case study of CR Express lines originating from Chengdu and Chongqing to Hamburg, the authors verify their model and conclude some findings. The results show that government subsidy is the major factor that influences operators pricing strategy. Also, frequency and local road infrastructure investment have effects on operators' decisions. For the government, giving more freedom to operators, that is letting operators decide their frequency, is a good way to bring benefits for both social welfare and operator profits.

- Record URL: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rtbm.2020.100529

- Record URL: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2210539519303931

- Find a library where document is available. Order URL: http://worldcat.org/issn/22105395

- © 2020 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Abstract reprinted with permission of Elsevier.

- Johnson, Daniel

- Wang, Judith Y T

- Shi, Xianliang

- Publication Date: 2021-3

- Media Type: Web

- Features: Figures; Maps; References; Tables;

- Research in Transportation Business & Management

- Issue Number: 0

- Publisher: Elsevier

- ISSN: 2210-5395

- Serial URL: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/22105395

Subject/Index Terms

- TRT Terms: Business practices ; Case studies ; Competition ; Railroad transportation

- Identifier Terms: China Railway Express Company

- Geographic Terms: Chengdu (China) ; Chongqing (China)

- Subject Areas: Administration and Management; Railroads;

Filing Info

- Accession Number: 01756044

- Record Type: Publication

- Files: TRIS

- Created Date: Oct 27 2020 12:25PM

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Price and Quantity Competition in a Differentiated Duopoly

1984, Rand Journal of Economics

Related Papers

European Economic Review

Monica Lopez

Ferenc Szidarovszky

This study complements the results developed by Häckner (2000) and Hus and Wang (2005). It constructs a n-firm oligopoly model with prod- uct differentiation and compares optimal prices, profits and welfare ob- tained under Cournot competition with those under Bertrand competi- tion. Three main results are demonstrated: (1) higher-qualified firms charge higher price under Bertrand competition than under Cournot com- petition when the goods are complements; (2) it depends on the ratio of the market average quality to the individual quality whether Cournot profit is higher than Bertrand profit or not; (3) social welfare (the sum of consumer surplus and profits) can be higher under Cournot competition than under Bertrand competition in the case of higher-qualified firms.

Economics Bulletin

Nicola Meccheri

International Journal of Game Theory

Martin N Shubik

Journal of Economics - J ECON

Joaquín Andaluz

Developing a location-price spatial model in a unionized mixed-duopoly, we find that the welfare-maximizing nature of the public firm implies a lower degree of product differentiation such that, in contrast to the private duopoly, the “Principle of Maximum Product Differentiation” is not reproduced. Considering two different wage-regimes for the public firm, this paper examines the effects of wage regulation imposed on civil servants. It is shown that, when a public firm’s union is prohibited from collective bargaining, the firm is more competitive, and the degree of differentiation is less. Moreover, regulation always reduces both the private firm’s profit and the level of social welfare.

Choi Kangsik

Malgorzata Knauff

We consider Cournot oligopoly with differentiated product. We develop respective sufficient conditions on the inverse demand and cost function that make the oligopoly a game of strategic substitutes when goods are substitutes and a game of strategic complementarities when goods are complements. The scope of this result is illustrated by examples. JEL classification: C72, L10, L13.

Tarun Kabiraj

We construct a model of differentiated duopoly with process R&D when goods are substitutes. In the first stage firms decide their technologies (i.e., the average costs of production) and in the second stage they compete in quantities or prices. We have shown that not only the Cournot firms invest a larger amount on R&D than the Bertrand firms, but, contrary to the result in the literature, Cournot price can be less than Bertrand price. This occurs when the R&D technology is relatively inefficient.

Research Papers in Economics

This paper aims at investigating if the conventional wisdom, that a decrease in the degree of product differentiation (which implies increasing competition) always reduces firms' profits, remains true in a differentiated duopoly model with decentralized, or firm-specific, monopoly unions. In this context, when product differentiation decreases, an important effect, termed "endogenous" or "union wage effect", adds to the standard competition effect in affecting profits. Moreover, the union wage effect operates against the competition effect and, provided that unions are sufficiently wage-oriented, that is, they sufficiently prefer wages to employment, can actually reverse the conventional result under both Cournot and Bertrand competition. However, this is more likely to occur under competition a la Cournot.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

mimee mimii

The Annals of Regional Science

Svend Albaek

SSRN Electronic Journal

corrado benassi

ACTA OECONOMICA PRAGENSIA Journal of Central and Eastern European Economic and Management Issues

Doriani Lingga

International Journal of Industrial Organization

Steffen Hoernig

Arijit Mukherjee

The Manchester School

Toshihiro Matsumura

Economia e Politica Industriale

Keita Yamane

Tetsuya Shinkai

The B.E. Journal of Theoretical Economics

Yi-Ling Cheng

Economics Letters

Emmanuel Petrakis

Tatyana Lebed

Keio Economic Studies

Osiris J Parcero

Australian Economic Papers

John Roemer

Journal of Public Economic Theory

The Rand Journal of Economics

Nicholas Economides

Pedro Jara-Moroni

Journal of Economics <html_ent glyph="@amp;" ascii="&"/> Management Strategy

Jacques-françois Thisse

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Price Competition in a Vertizontally Differentiated Duopoly

- Open access

- Published: 03 February 2023

- Volume 62 , pages 219–239, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Iwan Bos 1 &

- Ronald Peeters 2

2381 Accesses

Explore all metrics

This paper develops a price competition duopoly model in which products are both horizontally and vertically differentiated. Firms each offer a standard and a premium product to buyers—some of whom are brand loyal. We establish the existence of a unique and symmetric competitive pricing equilibrium. Equilibrium prices are increasing in the degree of horizontal differentiation and the number of brand-loyal customers. The equilibrium price of the standard (premium) good is decreasing (increasing) in the quality difference and profits can increase in costs when this difference is large enough. If the pricing decision is taken at the product (division) level, then there is again a unique (and symmetric) competitive pricing equilibrium. Equilibrium prices and profits are lower than in the centralized case and demand for the standard product is higher when the quality difference is sufficiently large. Welfare is unambiguously lower with decentralized pricing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Prices as signals of product quality in a duopoly

Product quality and endogenous firm objectives

Price competition with differentiated goods and incomplete product awareness

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the period mid 2017 until mid 2018, U.S. citizens spent over $5 billion on dry dog food. Footnote 1 The table below lists the four leading dry dog food brands in the period mid 2017 until mid 2018. Footnote 2 These four brands are produced by the two major firms in the dog food market: Nestlé (39% market share) and Mars (24% market share). The last column of the table presents the price per pound at Walmart for a large-sized bag. Footnote 3 Notice that both manufacturers offer a ‘standard’ and a ‘premium’ brand and that segment prices are (approximately) the same.

Rank | Brand | Dollar sales (million) | Manufacturer | $/lb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | Pedigree | $603 | Mars, Inc. | 0.52 |

2 | Purina dog chow | $457 | Nestlé Purina Petcare Co. | 0.45 |

3 | Purina one smartblend | $346 | Nestlé Purina Petcare Co. | 1.08 |

4 | Iams proactive health | $265 | Mars, Inc. | 1.08 |

There are many industries that consist of a few firms that compete in multiple market segments that are characterized by product quality. Footnote 4 A critical feature of such quality-segmented markets is that competition has both a horizontal and a vertical dimension. For instance, if a firm raises the price of its premium product, then it is likely to ‘lose’ customers to rival brands as well as to its own lower quality division(s). Likewise, if a firm cuts its premium product price, then ceteris paribus it steals customers from comparable quality competitors while cannibalizing the sales of its other items. The fact that multi-product firms are partly in competition with themselves makes the design of an optimal pricing policy far from trivial.

The purpose of this paper is to study strategic pricing by sellers that are competing ‘head-to-head’ in several quality segments simultaneously. Toward that end, we develop a price-setting duopoly model of vertizontal product differentiation in which firms offer both a standard and a premium product. Demand for these product types comes from two different sorts of customers: those who are brand-anchored; and those who are quality-anchored. Brand-anchored buyers choose only between the standard and premium product of their preferred supplier; by contrast, quality-anchored buyers have a preference for a particular quality level and choose between brands only. Footnote 5 The model contains no less than nine distinct demand- and supply-side parameters, which enables us to study separately the impact of these ‘horizontal’ and ‘vertical’ forces on firms’ pricing decisions.

To summarize some of our main findings: We establish the existence of a unique (and symmetric) competitive pricing equilibrium and perform a series of comparative statics exercises on this equilibrium outcome. With regard to the ‘horizontal forces’, we find that equilibrium prices are increasing in the extent of brand differentiation and decreasing in the number of quality-anchored buyers. With regard to the ‘vertical forces’, we establish that equilibrium prices are increasing in the number of brand-anchored buyers and show that the price of the standard (premium) product is decreasing (increasing) in the quality difference. Interestingly, we find that equilibrium profits may rise when there is a segment-wide increase in production costs.

We then use these results as a basis of comparison to explore the effect of decentralized pricing. If pricing decisions are taken at the product (division) level, then there is again a unique (and symmetric) competitive pricing equilibrium. The equilibrium outcome is such that both prices and profits are lower than in the centralized case. If the quality difference between the standard and premium product is substantial and the costs of producing additional quality are sufficiently small, then a switch from centralized to decentralized pricing leads to an increase of the standard good’s sales. By contrast, the premium product’s market share increases when the quality difference is limited and the marginal costs of producing extra quality are high enough. Last, we find that societal welfare is unambiguously lower with decentralized pricing.

The next section provides a brief literature review. Section 3 introduces the vertizontal differentiation model. The symmetric version of this model is analyzed in Sect. 4 . Sections 5 and 6 consider the impact of asymmetry in consumer preferences, unit costs and organizational structure. Section 7 concludes. All proofs are relegated to the Appendix.

2 Literature Review

This research is at the intersection of three strands of literature: First, it is naturally related to other works that consider vertizontal product differentiation. Vertizontal differentiation models have been employed to study a variety of economic questions: Di Comite et al. ( 2014 ), for instance, introduces a quadratic representative consumer model with vertizontal preferences to assess empirically firm performance in export markets. Building on Neven and Thisse ( 1990 ); Ribeiro ( 2015 ) analyzes price competition between two platforms ( e.g. , media outlets, clubs) that are vertizontally differentiated. Li and Peeters ( 2017 ) examine a vertizontal differentiation setting to study strategic quality information disclosure. None of this research considers multi-product competition, however.

Second, our work contributes to the growing literature on strategic firm behavior in multi-product oligopolies. Nocke and Schutz ( 2018 ) provides a framework to study multi-product pricing when these goods are horizontally differentiated. With regard to quality differentiation, Champsaur and Rochet ( 1989 ) examines what range of qualities profit-maximizing duopolists prefer to offer. More recently, Jing and Zhang ( 2011 ) and Johnson and Myatt ( 2003 , 2006 , 2015 ) also study competition among firms that sell multiple quality-differentiated products to address questions that are related to price promotions, entry, and product-line configurations. These works consider heterogeneity either in taste or in quality—but not both.

Perhaps closest to our work are Gilbert and Matutes ( 1993 ) and Desai ( 2001 ); both articles analyze strategic product line choices by multi-product firms in a vertizontally differentiated spatial setting. A key difference for our model is the presence of brand-loyal customers. Furthermore, our focus is on strategic pricing with vertizontal product differentiation and on how this pricing is affected by demand and supply side factors, such as consumer preferences, degree of differentiation, and production costs.

Third, and last, our analysis sheds light on the potential impact of delegating pricing authority. Stephenson et al. ( 1979 ), for example, use a sample of medical supplies and equipment sellers to compare central pricing authority with delegated pricing authority to the sales force. Among other things, they establish that gross margins and return on assets are lower with decentralized pricing. As argued by Lal ( 1986 ), however, delegating pricing responsibility to salespersons can be profitable when they have superior information about the selling environment. Frenzen et al. ( 2010 ) provide some empirical support for this. They establish a positive relation between pricing authority delegation and firm performance and this effect is strengthened in the presence of information asymmetry and market-related uncertainty.

More generally, there is an extensive literature that addresses the question of who should be granted pricing authority within an organization. Major contributions include Moorthy ( 1988 ), Bhardwaj ( 2001 ), Joseph ( 2001 ), McGuire and Staelin ( 2008 ), and Homburg et al. ( 2012 ), amongst many others. This literature presents conditions under which (de-)centralized pricing is optimal from a company’s perspective.

We compare the situation where price decisions are taken at the firm level (centralized pricing) with the situation where price decisions are taken at the product-quality-type level (decentralized pricing). Within our vertizontal differentiation setting, prices and profits are higher under centralized pricing. A main difference with the existing literature on the locus of pricing authority is that we consider the impact of (de-)centralized pricing on the demand for quality and welfare.

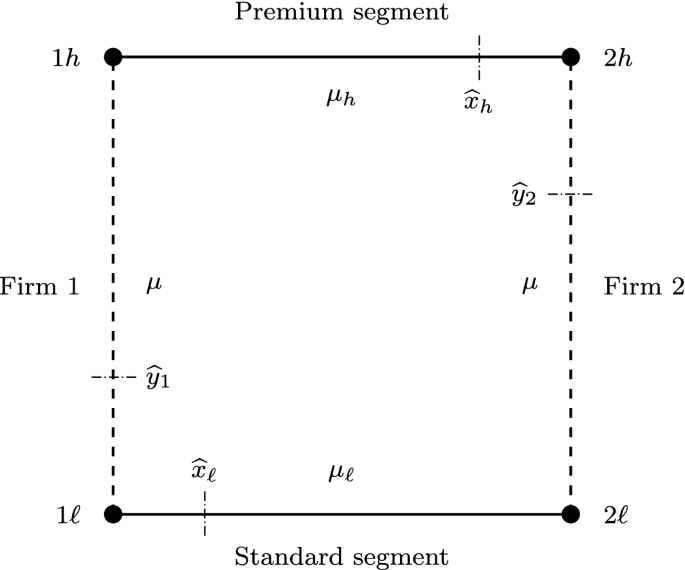

3 A Model of Vertizontal Product Differentiation

Consider a simultaneous-move price-setting duopoly with a low- (standard) and a high- (premium) quality market segment. Along the lines of Hotelling ( 1929 ), let both of these submarkets be represented by a unit interval. Quality is homogeneous within each segment and is indicated by the quality indices \(\beta >0\) and \(\beta +\delta >0\) for the standard and the premium product, respectively. The additional (perceived) quality of the premium product is therefore given by \(\delta >0\) . Products are positioned at the extremes of their respective segment and, without loss of generality, we assume that firm 1 is located at ‘0’ and firm 2 is located at ‘1’.

Firms’ cost structures are identical, and the low- and the high-quality varieties are respectively produced at constant marginal costs \(c_{\ell }\) and \(c_h\) , with \(c_h>c_{\ell }\ge 0\) . It is further assumed that \(\delta >c_h-c_{\ell }\) : The difference in product quality exceeds the additional costs of producing the premium product. Both the quality indices and cost parameters are exogenously given.

The demand side comprises two types of consumers: There is a mass of \(2\mu >0\) buyers who are brand-anchored and equally divided between both firms. These customers choose between buying a low- and a high-quality item from a particular brand: firm 1 or firm 2. They are characterized by a taste parameter y , which is uniformly distributed on the unit interval [0, 1] and which reflects the willingness to pay for extra quality. Thus, a consumer at the lower bound does not derive utility from more quality, whereas it is maximally valued at the upper extreme.

The remaining consumers are quality-anchored : They have a strict preference for a given quality and only choose between buying from firm 1 or firm 2. Both the standard and the premium quality-anchored buyers are uniformly distributed on the unit interval [0, 1] with mass \(\mu _{\ell }>0\) and \(\mu _h>0\) , respectively. A customer who is ‘located’ at \(x_j\) experiences a disutility of \(\tau _j\cdot x_j\) when buying from firm 1 and \(\tau _j\cdot (1-x_j)\) when buying from firm 2, where \(\tau _j>0\) for \(j=\ell ,h\) . Footnote 6

Our categorisation of customers is in part motivated by some recent findings in the consumer search literature. For example, it has been argued that consumers only search a small part of the attribute space and that state-dependence in search behavior is strong (Kim et al., 2011 ; Bronnenberg et al., 2016 ). This limits consumers’ consideration set (Mehta et al., 2003 ; De los Santos et al., 2012 ) and makes for insufficient comparisons across products and services (Simonson et al., 2013 ; Sela & LeBoeuf, 2017 ). With regard to the presence of quality-anchored buyers, note that this may partly result from differences in income. Indeed, an alternative interpretation is that consumers have the same valuation for quality, but different spending budgets (Gabszewicz & Thisse, 1979 ; Shaked & Sutton, 1982 ; Klumpp & Su, 2019 ).

As is well-known, in these types of spatial settings one can distinguish three cases depending on the set prices: (i) local monopolies; (ii) single monopoly; and (iii) competition. Footnote 7 In the following, we confine ourselves to situations in which the products compete. Case (i) is ruled out by assuming that all consumers buy the good—the market is ‘covered’—which effectively requires the quality index \(\beta \) to be sufficiently high. Specifically, each customer is assumed to purchase one unit of the product so that total market demand is given by \(2\mu +\mu _{\ell }+\mu _h>0\) .

To exclude Case (ii), we employ the notion of ‘social equilibrium’ as introduced by Debreu ( 1952 ). Footnote 8 The distinctive feature of this concept is that the sets of feasible strategies depend on the strategies that are chosen by others. Within the context of our model this means that a firm’s feasible prices are effectively determined by its rival’s price. In particular, for some given segment price of the competitor, a seller cannot set its price so low that it gains the complete segment. Likewise, it cannot pick a price so high that it loses the entire segment. Price differences are thus restricted in such a way that all product types have a positive market share.

Let us now derive demand for each product type. Consider a brand i -anchored buyer ‘located’ at \(y_i\) . This consumer is indifferent between buying the low-quality and buying the high-quality variety when:

where \(p_{ih}\) and \(p_{i\ell }\) are the prices of firm i ’s high- and low-quality product, respectively. Note that the degree to which the premium product is valued more than the standard product is determined by the combination of the ‘objective’ quality measure \(\delta \) and the ‘subjective’ quality measure \(y_i\) .

As an illustrative example, consider the choice between buying a software package with and without a supporting service package. At equal prices, virtually everyone would value the bundle more than the stand-alone software package. This difference in quality is captured by the parameter \(\delta \) . Yet, some customers may have poor computer skills and highly appreciate the additional support, whereas others may be IT experts who require little to no help. This heterogeneity in the ‘valuation of quality’ is captured by the parameter \(y_i\) .

Similarly, a quality j -anchored customer ‘located’ at \(x_j\) in the segment \(j=\ell ,h\) is indifferent between buying from firm 1 and buying from firm 2 when:

Taken together, this gives the following demand for the firms’ high- and low-quality product:

where \({\widehat{y}}_i\equiv \max \big \{\min \big \{\frac{p_{ih}-p_{i\ell }}{\delta },1\big \},0\big \}\) , \(i=1,2\) and \({\widehat{x}}_j\equiv \max \big \{\min \big \{\frac{p_{2j}-p_{1j}+\tau _j}{2\tau _j},1\big \},0\big \}\) , \(j=\ell ,h\) .

Figure 1 provides a graphical illustration of this model.

A stylized illustration of a vertizontally differentiated duopoly with brand-anchored consumers who are located on the dashed vertical segments and quality-anchored consumers who are located on the solid horizontal segments

In the following, we focus on cases in which each product type is bought by both brand- and quality-anchored buyers: \({\widehat{x}}_j\in (0,1)\) , \(j=\ell ,h\) ; and \({\widehat{y}}_i\in (0,1)\) , \(i=1,2\) (see Fig. 1 ). These conditions depend on price differences and are satisfied as long as the differences are not too large. Given that the competitor charges \(p_{kh}\) and \(p_{k\ell }\) , the condition \({\widehat{x}}_j\in (0,1)\) holds when firm i picks prices \(p_{ij}\in (p_{kj}-\tau _j,p_{kj}+\tau _j)\) . Similarly, \({\widehat{y}}_i\in (0,1)\) requires that \(p_{i\ell }\) and \(p_{ih}\) are chosen such that \(0<p_{ih}-p_{i\ell }<\delta \) . Note, however, that for the latter both prices are selected by the same seller. To ensure that \({\widehat{y}}_i\) remains in the interior, we impose the following assumption which effectively provides an upper bound on the difference between competition intensity in both quality segments. Footnote 9

Assumption 1

\(-(c_h-c_{\ell })<\tau _h-\tau _{\ell }<\delta -(c_h-c_{\ell })\) .

In the following analysis, we solve for a Nash equilibrium of this game—which we refer to as competitive pricing equilibrium .

4 Equilibrium Pricing and Analysis

In this section, we explore the nature of price competition between the two firms. Under the assumption that both simultaneously pick prices from their (relative) strategy sets as specified above, firm 1 chooses \(p_{1\ell }\) and \(p_{1h}\) to maximize

whereas firm 2 selects \(p_{2\ell }\) and \(p_{2h}\) to maximize

The next result shows that there is a unique competitive pricing equilibrium and that this equilibrium is symmetric. Moreover, the equilibrium price of the premium product exceeds that of the standard product:

Proposition 1

Under Assumption 1 , there is a unique competitive pricing equilibrium. In this equilibrium, firms set prices symmetrically at:

Furthermore, \(0<p_h^*-p_{\ell }^*<\delta \) . Footnote 10

The way in which equilibrium prices are presented here is reminiscent of the equilibrium outcome in a standard version of Hotelling’s model of horizontal product differentiation: \(p_j^*=c_j+\tau _j\) , \(j=\ell ,h\) . In fact, notice that both prices coincide when the number of brand-anchored buyers becomes negligible: \(\mu \downarrow 0\) .

Even though one might a priori expect firms to set higher prices in the presence of brand-anchored buyers, Proposition 1 reveals that vertizontal equilibrium prices may actually be lower than those in the corresponding horizontal version without brand-loyal customers: when \(\mu \downarrow 0\) . The price of the standard product is, for example, lower than \(c_{\ell }+\tau _{\ell }\) when there is severe price competition in the premium segment ( \(\tau _h\downarrow 0\) ) and relatively low competitive pressure in the other submarket ( \(\tau _{\ell }\uparrow c_h-c_{\ell }\) ).

Likewise, the premium price is lower than \(c_h+\tau _h\) when there is strong price competition in the standard-quality product market ( \(\tau _{\ell }\downarrow 0\) ) and relatively low competitive pressure in the premium segment ( \(\tau _h\uparrow \delta -(c_h-c_{\ell })\) ). Intense price competition in one segment therefore puts downward pressure on prices in the adjacent segment and this ‘negative vertical price effect’ can dominate the ‘positive horizontal price effect’: The presence of brand-anchored buyers can lead to more competitive prices in the segment where price competition is otherwise less severe.

We now proceed by studying comparative statics of the equilibrium prices. The next proposition shows that both prices are increasing in both unit production costs:

Proposition 2

Under Assumption 1 , the equilibrium prices \(p_{\ell }^*\) and \(p_h^*\) are increasing in the unit production costs \(c_{\ell }\) and \(c_h\) .

The firms’ standard and premium prices are naturally increasing in their own production costs. Demand for the adjacent quality then rises with a subsequent price increase in that segment. It can, moreover, be shown that the direct effect dominates the indirect effect, so that an increase in \(c_h\) ceteris paribus boosts low-quality product sales. An increase in \(c_{\ell }\) likewise leads to a rising premium product market share, all else equal.

The impact on prices of a change in the (perceived) quality difference ( \(\delta \) ), horizontal competitive pressure ( \(\tau _{\ell }\) and \(\tau _h\) ), and the number of brand- and quality-anchored buyers ( \(\mu \) , \(\mu _{\ell }\) and \(\mu _h\) ) is less clear. To explore this in more detail, we impose the following condition:

Assumption 2

\(-\frac{c_h-c_{\ell }}{2}<\tau _h-\tau _{\ell }<\frac{\delta -(c_h-c_{\ell })}{2}\) .

This assumption is directly comparable to Assumption 1 and restricts the range within which the horizontal differentiation parameters are allowed to vary.

Let us start by exploring the effect of changes in the horizontal dimension of the model. The following result gives the price impact of changes in the horizontal differentiation parameters and the number of low- and high-quality-anchored consumers.

Proposition 3

Under Assumption 2 , the equilibrium prices \(p_{\ell }^*\) and \(p_h^*\) are increasing in the horizontal differentiation parameters \(\tau _{\ell }\) and \(\tau _h\) and decreasing in the number of low and high quality-anchored buyers \(\mu _{\ell }\) and \(\mu _h\) . Footnote 11

An increase in the horizontal differentiation parameter \(\tau _j\) , \(j=\ell ,h\) , leads ceteris paribus to an increase of prices in segment j . This, in turn, generates more demand in the other segment with a subsequent price increase.

With regard to the number of quality-anchored buyers, more customers in, say, the premium segment intensifies competition in that part of the market with lower premium prices resulting. More brand-anchored buyers are therefore willing to switch to the high-quality product, which in turn makes it less costly to cut prices in the lower segment. As before, the direct effect dominates the indirect effect so that an increase in the number of high (low) quality-anchored buyers results in more high (low) quality product sales. Notice that it is the presence of brand-anchored consumers that drives this effect: Absent a brand-loyal customer base, equilibrium prices would be independent of the mass of quality-oriented consumers.

Next, let us turn to the vertical sphere. The following result shows how the equilibrium prices are affected by changes in the number of brand-anchored customers and the quality difference:

Proposition 4

Under Assumption 2 , the equilibrium prices \(p_{\ell }^*\) and \(p_h^*\) are increasing in the number of brand-anchored consumers \(\mu \) . Furthermore, \(p_{\ell }^*\) is decreasing and \(p_h^*\) is increasing in the quality difference \(\delta \) .

A growing number of brand-anchored buyers naturally enhances the incentive to exploit their loyalty through raising prices.

The price effect of a change in quality difference is more subtle. As one would expect, an immediate effect of an increase in \(\delta \) is that more buyers prefer the high-quality product. The resulting premium price rise does not fully offset this effect, which is partly due to the presence of competition in the high-quality segment. The subsequent loss in brand-anchored consumers who buy the standard product makes it less costly to cut the standard good price and steal some business in the low-quality segment. Overall, however, premium product sales are increasing in the quality difference.

Let us now turn to equilibrium profits: Profits are not trivial to analyze within the current framework, which is particularly due to the richness in the parameters that describe the demand side. By imposing symmetry across quality segments, however, we can establish the following supply-side effect.

Proposition 5

Assume \(\mu _h=\mu _{\ell }\) and \(\tau _h=\tau _{\ell }\) .

If \(\delta >2(c_h-c_{\ell })\) , then equilibrium profits \(\pi _1^*\) and \(\pi _2^*\) are increasing in \(c_{\ell }\) and decreasing in \(c_h\) .

If \(\delta <2(c_h-c_{\ell })\) , then equilibrium profits \(\pi _1^*\) and \(\pi _2^*\) are decreasing in \(c_{\ell }\) and increasing in \(c_h\) .

This result reveals that equilibrium profits can decrease, but may also increase in unit production costs. If the quality difference between the standard and premium product is sufficiently large, then profits are decreasing in \(c_{h}\) and increasing in \(c_{\ell }\) . The reason is as follows: If \(\delta >2(c_{h}-c_{\ell })\) , then the majority of brand-anchored buyers opts for the premium product: \({\widehat{y}}_{i}^{*}=\frac{p_{ih}^{*}-p_{i\ell }^{*}}{\delta }<\frac{1}{2}\) is relatively low. Footnote 12 The reduced price-cost margin \(p_{ih}^{*}-c_{h}\) would therefore result in relatively large losses. This negative direct effect is only partly offset by the positive indirect effect: the rise in the price of the standard good. The latter effect is smaller since only a modest part of the brand-anchored buyers prefers the low-quality product when the quality difference is high.

In a similar fashion, equilibrium profits increase in \(c_{\ell }\) . The direct effect is again negative, but relatively small since few brand-anchored consumers choose the standard good. By contrast, the positive indirect effect that comes from the increase in the premium price is comparably big because of the large share of brand-anchored buyers that picks the high-quality product. The combined effect is positive when \(\delta \) is sufficiently high. A similar logic applies when the difference in quality is sufficiently low, meaning that the majority of brand-anchored buyers opts for the standard good: \({\widehat{y}}_{i}^{*}=\frac{p_{ih}^{*}-p_{i\ell }^{*}}{\delta }>\frac{1}{2}\) is relatively high. In that case, profits are decreasing in \(c_{\ell }\) and increasing in \(c_{h}\) .

In sum, firms benefit from a segment-wide cost decrease in the most popular submarket. Strikingly, however, they also benefit from a segment-wide cost increase in the least popular submarket. The negative direct effect of the cost increase is more than compensated for by the resulting price increase in the adjacent popular segment. Footnote 13

5 Asymmetries

In this section and in Sect. 6 , we consider price competition in the vertizontally differentiated duopoly when there is some asymmetry between the sellers. We examine two types of asymmetries: asymmetry in demand- and supply-side parameters; and (in Sect. 6 ) asymmetry in organizational structure. To maintain tractability, it is assumed throughout this section that \(\mu _{h}=\mu _{\ell }\) , \(\tau _{h}=\tau _{\ell }\) , and \(c_{\ell }=0\) . Footnote 14

5.1 Demand- and Supply-side Parameters

We discuss two possible demand-side asymmetries that relate to consumer preferences: (1) the number of brand-anchored consumers in the vertical segments; and (2) the product taste of quality-anchored consumers in the horizontal segments. We also consider a possible supply-side asymmetry: unit cost of producing the premium product.

To begin, suppose there is a difference in brand-loyal customer bases. In that case, we find that the firm with more brand-anchored buyers ceteris paribus charges a higher price for both the standard and the premium product. Being the higher-priced firm, this seller consequently captures a smaller share of the quality-anchored buyers. However, the implied lower market share is more than compensated for by the higher mark-up so that the firm with the larger brand-loyal customer base is the one making more profit.

Let us now turn to the possibility that quality-oriented buyers have different tastes for both brands. Specifically, it is assumed that \(\tau _{\ell }\) ( \(=\tau _{h}\) ) are different for the two firms. In this case, we find that the favorite firm—the seller with the lower \(\tau \) —sets the higher price for both product varieties. Taking a comparative statics perspective, this firm is able to harvest its brand-loyal customer base without losing too much share in the two quality segments. In fact, the equilibrium is such that it still has the higher market share in each horizontal submarket. Since there are no differences in the vertical segments, this implies that the firm with the lower \(\tau \) earns the highest profits.

Third, suppose that one of the sellers faces higher costs when producing its premium product. This firm then charges a higher price for its high-quality good, which implies a smaller market share in the premium segment. Interestingly, this high-cost supplier becomes the lower-priced firm in the standard segment. The implied larger market share in the low-quality segment does not make up for its disadvantageous position in the premium segment, however. Overall, therefore, it is the low-cost supplier that makes more profit.

6 Organizational Structure

A different type of asymmetry that can affect the competitive pricing equilibrium concerns the allocation of pricing authority. In the preceding analysis, we have assumed pricing decisions to be taken at the firm level. Yet, and as already touched upon in Sect. 2 , companies sometimes choose to delegate such decisions to lower-level management or sales departments. Within the context of our model, decentralized pricing means that pricing decisions are taken at the product quality type level.

The issue of (de-)centralized pricing has been addressed by McGuire and Staelin ( 2008 ) within the context of a vertical production chain. Amongst others, they show that decentralized decision-making is a Nash equilibrium when products are sufficiently close substitutes. Moorthy ( 1988 ) offers conditions under which (de-)centralized pricing emerges as an equilibrium. Bhardwaj ( 2001 ) extends these analyses by explicitly taking account of sales agents’ effort. He finds that firms prefer centralized pricing when there is sufficiently intense effort competition.

Under the parameter restrictions that we impose to maintain tractability— \(\mu _{h}=\mu _{\ell }\) , \(\tau _{h}=\tau _{\ell }\) , and \(c_{\ell }=0\) —we find that centralized pricing is an equilibrium and decentralized pricing is not. Footnote 15 Yet, when firms adopt a different organizational structure, it is the seller that delegates pricing authority that makes more profits. If we take a Darwinian dynamic perspective as in Alchian ( 1950 ) and Vega-Redondo ( 1997 ), this suggest that decentralized pricing may become the dominant organizational mode. In the next section, we explore the possibility that both sellers delegate pricing decisions to the product division level in more detail.

6.1 Centralized Versus Decentralized Pricing

We now direct attention to the case in which both firms have delegated pricing authority and compare this with the centralized pricing results presented in Sect. 4 . Since prices are determined at the product quality type level, these quality divisions effectively operate as distinct firms: With decentralized pricing there is competition among four rather than two vertizontally differentiated market entities. In what follows, we show that with decentralized pricing: (i) consumers are better off; (ii) firms are worse off; and (iii) society as a whole is worse off. Moreover, the market share of the standard product is shown to increase (decrease) with decentralized pricing when the marginal costs of quality is sufficiently low (high).

The next result is directly comparable to Proposition 1 and shows that there is again a unique (and symmetric) competitive pricing equilibrium when prices are set at the product type level. Akin to the centralized pricing case, the equilibrium price of the premium product exceeds that of the standard good.

Proposition 6

Under Assumption 1 and \(\delta \ge \max \{\tau _{\ell },\tau _h\}\) , there is a unique competitive pricing equilibrium. In this equilibrium, firms set prices symmetrically at:

Furthermore, \(0<p_h^{\circ }-p_{\ell }^{\circ }<\delta \) .

To avoid complex expressions, but without renouncing any factor that is crucial to the understanding of the mechanic forces when comparing decentralized pricing with centralized pricing in the context of the vertizontally differentiated market, we restrict the parameters to \(\mu _h=\mu _{\ell }=\mu =1\) and \(\tau _h=\tau _{\ell }\) and assume \(\delta \ge \max \{\tau _{\ell },\tau _h\}\) (such that \({\widehat{y}}^{\circ }\in (0,1)\) ). Doing so, we obtain the following result.

Proposition 7

Prices and profits are lower under decentralized pricing than under centralized pricing. Moreover,

If \(\delta >2(c_h-c_{\ell })\) , then there is greater demand for low quality under decentralized pricing than under centralized pricing.

If \(\delta <2(c_h-c_{\ell })\) , then there is greater demand for high quality under decentralized pricing than under centralized pricing.

This proposition shows that producer surplus—which is defined as the sum of profits—is lower when pricing authority is delegated. This is a direct consequence of increased competition. By contrast, consumers benefit from decentralized pricing. Indeed, each non-switching customer benefits from a lower price, and those who do switch benefit even more.

Notice that whether demand shifts from the standard to the premium segment or vice versa depends on the marginal cost of quality. If \(\delta >2(c_{h}-c_{\ell })\) , then the amount of premium products that are sold under centralized pricing exceeds the amount of standard products that are sold. A transition to decentralized pricing results in a price reduction for all products. However, since the premium product has the bigger market share, the corresponding marginal revenue is lower: It is ceteris paribus more costly to reduce the price of the premium product than that of the standard good. Delegating pricing authority in this case consequently leads to an increase in the equilibrium price difference, which implies an increase in the standard good’s market share (Proposition 7 (i)). As Proposition 7 (ii) shows, the opposite occurs when \(\delta <2(c_{h}-c_{\ell })\) .

To determine the net welfare effect, first note that the market is covered under both centralized and decentralized pricing. As long as customers do not switch between product types, therefore, a change in the locus of pricing authority would only cause a redistribution of welfare. Consequently, any change in total surplus should come from those who switch between the low- and high-quality product type. Proposition 7 (i) shows that if \(\delta >2(c_{h}-c_{\ell })\) , then for each brand there is an interval Y of brand-anchored buyers who switch from the high- to the low-quality product. Likewise, Proposition 7 (ii) shows that when \(\delta <2(c_{h}-c_{\ell })\) , there is an interval Y of brand-anchored buyers who switch in the opposite direction.

These switching consumers \(y\in Y\) create a welfare gain (loss) by a reduction (increase) in \(c_{h}-c_{\ell }\) and a welfare loss (gain) of \(\delta y\) . Aggregating these differences over all switching consumers gives the change in overall welfare,

which leads to the following conclusion:

Proposition 8

Decentralized pricing unambiguously yields a welfare loss.

The logic behind this result is as follows: Suppose that \(\delta >2(c_{h}-c_{\ell })\) , so that the market share of the standard product increases when moving from a centralized to a decentralized pricing system (Proposition 7 (i)). Since part of the premium products are replaced with standard products, there is a saving in production costs. This has a positive effect on societal welfare. There is, however, a counter effect: First, the switching customers lose the benefit of having a higher-quality product \(\delta \) ; this is an effect that is relatively substantial in this case. Second, those who switch have a relatively high valuation for quality: y is relatively high. Together, this implies that the loss \(\delta y\) of a switching customer with valuation y is large and, in fact, so large that it outweighs the positive cost-saving effect.

Now suppose that \(\delta <2(c_{h}-c_{\ell })\) , so that the market share of the premium product increases when moving from a centralized to a decentralized pricing system (Proposition 7 (ii)). This results in an increase in production costs, which negatively affects social welfare. There is also a positive effect \(\delta y\) , because a switching customer with valuation y now consumes the premium product. Notice, however, that in this case switching customers have a fairly low valuation for quality— y is ‘small’—and that the extra quality of a premium product is limited: \(\delta \) is ‘small’. As Proposition 8 reveals, the additional gain from an increase in the premium product’s market share is insufficient to compensate for the additional costs of producing the high-quality good.

7 Concluding Remarks

In this paper, we consider strategic pricing by sellers that supply multiple quality variants of their product and simultaneously compete ‘head-to-head’ in the corresponding quality-segments. Specifically, we analyzed a duopoly model of vertizontal product differentiation in which firms offer a standard and a premium good. Under the assumption that demand includes both brand- and quality-anchored buyers, we established the existence of a unique (and symmetric) competitive pricing equilibrium. These equilibrium prices are increasing in the degree of brand differentiation as well as in the number of brand-anchored buyers. Moreover, equilibrium profits may increase in production costs and the equilibrium price of the standard (premium) product is decreasing (increasing) in the quality difference.

We contrasted these findings with the possibility that pricing decisions are taken decentrally at the product type level. We prove there is again a unique (and symmetric) competitive pricing equilibrium in which both prices and profits are lower than in the centralized case. We furthermore find that demand for the standard product is higher when the quality difference is sufficiently large and show that welfare is unambiguously lower with decentralized pricing.

There are several natural avenues for future research: One is to extend the dimensions of the model: the number of firms or of quality segments. This, however, is likely to prove challenging in terms of deriving explicit and meaningful expressions. Another is to use this framework to analyze competition among multi-product and single-product, niche, firms. Finally, it is worth exploring what type of vertizontally differentiated markets may emerge endogenously. The interesting question is then under what conditions firms would position themselves ‘head-to-head’ along the quality spectrum when engaging in price competition.

Source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/253976/pet-food-industry-expenditure-in-the-us .

Source: https://www.petfoodprocessing.net/articles/12825-state-of-the-us-pet-food-and-treat-industry .

Information retrieved on May 20, 2019.

As reported in Nocke and Schutz ( 2018 ), multiproduct firms account for 91% of total output and 41% of the number of firms in the U.S. with an average four-firm concentration ratio of 35% in U.S. manufacturing when measured at the NAICS 5-digit level.

At the firm level, therefore, brand-anchored buyers are ‘captive’ and quality-anchored buyers are ‘non-captive’. See, for instance, Sonderegger ( 2011 ).

As in Altomonte et al. ( 2016 ) and Desai ( 2001 ), this model therefore allows for asymmetric horizontal product differentiation across market segments.

See, for instance, Tirole ( 1988 ).

For a discussion and appraisal of this equilibrium concept, see Dasgupta and Maskin ( 2015 ).

As will become clear in the next section, Assumption 1 is a sufficient condition for the existence of a unique Nash equilibrium in which \({\widehat{y}}_i\in (0,1)\) . Given the equilibrium prices, one can then easily derive restrictions on the relative prices such that this equilibrium is indeed a social equilibrium.

It can be easily verified that \(c_h>c_{\ell }\) implies \(p_{\ell }^*\ge c_{\ell }\) and \(\delta >c_h-c_{\ell }\) implies \(p_h^*\ge c_h\) .

It is worth noting that Assumption 1 would be sufficient to establish the reported impact of \(\tau _{\ell }\) and \(\tau _{h}\) .

One can verify that \(p_{ih}^{*}-p_{i\ell }^{*}=c_{h}-c_{\ell }\) when \(\delta =2\left( c_{h}-c_{\ell }\right) \) so that \({\widehat{y}}_{i}^{*}=\frac{c_{h}-c_{\ell }}{\delta }=\frac{1}{2}\) . In that case, the number of premium products that are sold equals the number of standard products that are sold.

Within the context of a homogeneous-good Cournot oligopoly game, Kimmel ( 1992 ) shows that firms may benefit from an industry-wide cost increase. In our model, the covered-market assumption contributes to this result.

The Mathematica code and output on which the reported findings are based are provided in an online appendix to this paper, which is publicly available on the Open Science Framework (OSF; doi: 10.17605/osf.io/wcd7s) and accessible via https://osf.io/wcd7s/ .

See the online Appendix.

Alchian, A. A. (1950). Uncertainty, evolution, and economic theory. Journal of Political Economy, 58 (3), 211–221.

Article Google Scholar

Altomonte, C., Colantone, I., & Pennings, E. (2016). Heterogeneous firms and asymmetric product differentiation. Journal of Industrial Economics, 64 (4), 835–874.

Bhardwaj, P. (2001). Delegating pricing decisions. Marketing Science, 20 (2), 143–169.

Bronnenberg, B. J., Kim, J. B., & Mela, C. F. (2016). Zooming in on choice: How do consumers search for cameras online? Marketing Science, 35 (5), 693–712.

Champsaur, P., & Rochet, J.-C. (1989). Multiproduct duopolists. Econometrica, 57 (3), 533–557.

Dasgupta, P. S., & Maskin, E. S. (2015). Debreu’s social equilibrium existence theorem. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112 (52), 15769–15770.

Debreu, G. (1952). A social equilibrium existence theorem. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 38 (10), 886–893.

De los Santos, B., Hortaçsu, A., & Wildenbeest, M. R. (2012). Testing models of consumer search using data on web browsing and purchasing behavior. American Economic Review, 102 (6):2955–2980.

Desai, P. S. (2001). Quality segmentation in spatial markets: When does cannibalization affect product line design? Marketing Science, 20 (3), 265–283.

Di Comite, F., Thisse, J.-F., & Vandenbussche, H. (2014). Verti-zontal differentiation in export markets. Journal of International Economics, 93 (1), 50–66.

Frenzen, H., Hansen, A.-K., Krafft, M., Mantrala, M. K., & Schmidt, S. (2010). Delegation of pricing authority to the sales force: An agency-theoretic perspective of its determinants and impact on performance. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 27 (1), 58–68.

Gabszewicz, J. J., & Thisse, J.-F. (1979). Price competition, quality and income disparities. Journal of Economic Theory, 20 (3), 340–359.

Gilbert, R. J., & Matutes, C. (1993). Product line rivalry with brand differentiation. Journal of Industrial Economics, 41 (3), 223–240.

Homburg, C., Jensen, O., & Hahn, A. (2012). How to organize pricing? Vertical delegation and horizontal dispersion of pricing authority. Journal of Marketing, 76 (5), 49–69.

Hotelling, H. (1929). Stability in competition. Economic Journal, 39 (153), 41–57.

Jing, B., & Zhang, Z. J. (2011). Product line competition and price promotions. Quantitative Marketing and Economics, 9 (3), 275–299.

Johnson, J. P., & Myatt, D. P. (2003). Multiproduct quality competition: Fighting brands and product line pruning. American Economic Review, 93 (3), 748–774.

Johnson, J. P., & Myatt, D. P. (2006). Multiproduct Cournot oligopoly. RAND Journal of Economics, 37 (3), 583–601.

Johnson, J. P., & Myatt, D. P. (2015). The properties of product line prices. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 43 , 182–188.

Joseph, K. (2001). On the optimality of delegating pricing authority to the sales force. Journal of Marketing, 65 (1), 62–70.

Kim, J. B., Albuquerque, P., & Bronnenberg, B. J. (2011). Mapping online consumer search. Journal of Marketing Research, 48 , 13–27.

Kimmel, S. (1992). Effects of Cost Changes on Oligopolists’ Profits. Journal of Industrial Economics, 40 (4), 441–449.

Klumpp, T., & Su, X. (2019). Price-quality competition in a mixed duopoly. Journal of Public Economic Theory, 21 , 400–432.

Lal, R. (1986). Delegating pricing responsibility to the salesforce. Marketing Science, 5 (2), 159–168.

Li, X., & Peeters, R. (2017). Rivalry information acquisition and disclosure. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 26 (3), 610–623.

Google Scholar

McGuire, T. W., & Staelin, R. (2008). An industry equilibrium analysis of downstream vertical integration. Marketing Science, 27 (1), 115–130.

Mehta, N., Rajiv, S., & Srinivasan, K. (2003). Price uncertainty and consumer search: A structural model of consideration set formation. Marketing Science, 22 (1), 58–84.

Moorthy, K. S. (1988). Strategic decentralization in channels. Marketing Science, 7 (4), 335–355.

Neven, D. J., & Thisse, J.-F. (1990). On quality and variety competition. In J. J. Gabszewicz, J. F. Richard, & L. Wolsey (Eds.), Economic Decision Making: Games, Econometrics and Optimization. Contributions in the Honour of Jacques H. Dréze . North-Holland, Amsterdam.

Nocke, V., & Schutz, N. (2018). Multiproduct-firm oligopoly: An aggregative games approach. Econometrica, 86 (2), 523–557.

Ribeiro, V. M. (2015). Product differentiation in two-sided markets. Ph.D. Dissertation, Chapter 5 . University of Porto.

Sela, A., & LeBoeuf, R. A. (2017). Comparison neglect in upgrade decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 54 , 556–571.

Shaked, A., & Sutton, J. (1982). Relaxing price competition through product differentiation. Review of Economic Studies, 49 (1), 3–13.

Simonson, I., Bettman, J. R., Kramer, T., & Payne, J. W. (2013). Comparison selection: An approach to the study of consumer judgment and choice. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 23 (1), 137–149.

Sonderegger, S. (2011). Market segmentation with nonlinear pricing. Journal of Industrial Economics, 59 (1), 38–62.

Stephenson, P. R., Cron, W. L., & Frazier, G. L. (1979). Delegating pricing authority to the sales force: The effects on sales and profit performance. Journal of Marketing, 43 (2), 21–28.

Tirole, J. (1988). The Theory of Industrial Organization . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Vega-Redondo, F. (1997). The evolution of Walrasian behavior. Econometrica, 65 (2), 375–384.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Organisation, Strategy and Entrepreneurship, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands

Department of Economics, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand

Ronald Peeters

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Iwan Bos .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We appreciate the comments and suggestions of two anonymous reviewers and the editor, Lawrence White. Bos and Peeters acknowledge the hospitality of the Maastricht University School of Business and Economics and the University of Otago, where part of this research was conducted.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file 1 (pdf 145 KB)

Appendix: proofs, proof of proposition 1.

The first-order conditions for the two simultaneous maximization problems yield the following system of linear equations:

For both firms, solutions being maxima of their respective maximization problem is guaranteed by the negative definite Hessians:

Since the matrix of coefficients in the system of linear equations is non-singular, we know that this system has one real solution. Moreover, given that asymmetric equilibria need to come in pairs, this solution must be symmetric. Exploiting this symmetry (that is, assuming \(p_{1\ell }=p_{2\ell }=p_{\ell }\) and \(p_{1h}=p_{2h}=p_h\) ), the above system reduces to

Solving this system gives the solution \((p_{\ell }^*,p_h^*)\) as specified in the proposition. Finally, feasibility conditions for the demand being well-specified (i.e., \({\widehat{y}}_1,{\widehat{y}}_2\in (0,1)\) at prices \(p_{\ell }^*\) and \(p_h^*\) ) requires \(p_h^*>p_{\ell }^*\) and \(p_h^*-p_{\ell }^*<\delta \) . As one can easily verify, Assumption 1 is a sufficient condition for \(p_h^*>p_{\ell }^*\) and \(p_h^*-p_{\ell }^*<\delta \) .

\(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 2

The first derivative of \(p_{\ell }^*\) with respect to \(c_{\ell }\) and \(c_h\) is respectively given by:

and the first derivative of \(p_h^*\) with respect to \(c_{\ell }\) and \(c_h\) is respectively given by:

Proof of Proposition 3

The first derivative of \(p_{\ell }^*\) with respect to \(\tau _{\ell }\) , \(\tau _h\) , \(\mu _{\ell }\) and \(\mu _h\) is respectively given by:

The first derivative of \(p_h^*\) with respect to \(\tau _{\ell }\) , \(\tau _h\) , \(\mu _{\ell }\) and \(\mu _h\) is respectively given by:

The terms in squared brackets in the numerator are positive by Assumption 2 .

Proof of Proposition 4

The first derivative of \(p_{\ell }^*\) with respect to \(\mu \) and \(\delta \) is respectively given by:

The first derivative of \(p_h^*\) with respect to \(\mu \) and \(\delta \) is respectively given by:

In determining the sign of these derivatives, notice that the term in squared brackets in the numerators is positive by Assumption 2 .

Proof of Proposition 5

Setting \(\mu _{\ell }=\mu _h\) and \(\tau _{\ell }=\tau _h\) , the first derivative of \(\pi ^*\) with respect to \(c_{\ell }\) and \(c_h\) is given by:

The term in the squared brackets determines the sign of the derivatives.

Proof of Proposition 6

The first-order conditions for the four simultaneous maximization problems yield the following system of linear equations

Since the matrix of coefficients in the system of linear equations is non-singular, we know that this system has one real solution. Moreover, given that asymmetric equilibria need to come in pairs, this solution must be symmetric. Exploiting this symmetry—assuming \(p_{1\ell }=p_{2\ell }=p_{\ell }\) and \(p_{1h}=p_{2h}=p_h\) —the above system reduces to

Solving this system gives the solution \((p_{\ell }^{\circ },p_h^{\circ },)\) as specified in the proposition. Finally, feasibility conditions for the demand being well-specified (i.e., \({\widehat{y}}_1,{\widehat{y}}_2\in (0,1)\) at prices \(p_{\ell }^{\circ }\) and \(p_h^{\circ }\) ) requires \(p_h^{\circ }>p_{\ell }^{\circ }\) and \(p_h^{\circ }-p_{\ell }^{\circ }<\delta \) . It can be verified that Assumption 1 and \(\delta \ge \max \{\tau _{\ell },\tau _h\}\) are a sufficient condition for \(p_h^{\circ }>p_{\ell }^{\circ }\) and \(p_h^{\circ }-p_{\ell }^{\circ }<\delta \) .

Proof of Proposition 7

For \(\mu _h=\mu _{\ell }=\mu =1\) and \(\tau _h=\tau _{\ell }=\tau \) , we have:

From this, we obtain the profits

The statement in the proposition follows from a comparison of these values.

Proof of Proposition 8

If \(\delta >2(c_h-c_{\ell })\) , then \(Y=[{\widehat{y}}^*,{\widehat{y}}^{\circ }]\) and the change in welfare is given by

Alternatively, if \(\delta <2(c_h-c_{\ell })\) , then \(Y=[{\widehat{y}} ^{\circ },{\widehat{y}}^*]\) and the change in welfare is given by

Both expressions lead to

which is negative.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Bos, I., Peeters, R. Price Competition in a Vertizontally Differentiated Duopoly. Rev Ind Organ 62 , 219–239 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-023-09895-0

Download citation

Published : 03 February 2023

Issue Date : May 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-023-09895-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cannibalization

- Multi-product oligopoly

- Vertizontal differentiation

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

Understanding a Duopoly

Duopoly vs. duopsony.

- Advantages and Disadvantages

Two Main Types of Duopoly

Examples of duopoly, what is a duopoly in economics, what is an example of a duopoly, is duopoly a oligopoly, the bottom line.

- Fundamental Analysis

- Sectors & Industries

Duopoly: Definition in Economics, Types, and Examples

Gordon Scott has been an active investor and technical analyst or 20+ years. He is a Chartered Market Technician (CMT).

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/gordonscottphoto-5bfc26c446e0fb00265b0ed4.jpg)

Yarilet Perez is an experienced multimedia journalist and fact-checker with a Master of Science in Journalism. She has worked in multiple cities covering breaking news, politics, education, and more. Her expertise is in personal finance and investing, and real estate.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/YariletPerez-d2289cb01c3c4f2aabf79ce6057e5078.jpg)

- Antitrust Laws: What They Are, How They Work, Major Examples

- Understanding Antitrust Laws

- Federal Trade Commission (FTC)

- Clayton Antitrust Act

- Sherman Antitrust Act

- Robinson-Patman Act

- How and Why Companies Become Monopolies

- Discriminating Monopoly

- Price Discrimination

- Predatory Pricing

- Bid Rigging

- Price Maker

- Monopolistic Markets

- Monopolistic Competition

- What Are the Characteristics of a Monopolistic Market?

- Monopolistic Market vs. Perfect Competition

- What are Some Examples of Monopolistic Markets?

- A History of U.S. Monopolies

- What Are the Most Famous Monopolies?

- Monopoly vs. Oligopoly

- Duopoly CURRENT ARTICLE

- What are Current Examples of Oligopolies?

Investopedia / Julie Bang

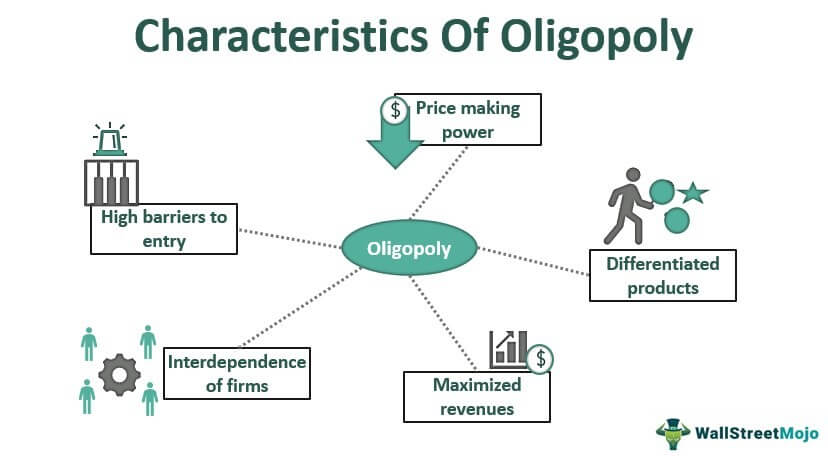

A duopoly is a situation where two companies together own all, or nearly all, of the market for a given product or service. A duopoly is the most basic form of oligopoly , a market dominated by a small number of companies. A duopoly can have the same impact on the market as a monopoly if the two players collude on prices or output.

Key Takeaways

- A duopoly is a form of oligopoly, where only two companies dominate the market.

- The companies in a duopoly tend to compete against one another, reducing the chance of monopolistic market power.

- Visa and Mastercard are examples of a duopoly that dominates the payments industry in Europe and the United States.

- One disadvantage of duopolies is that consumers have little choice in products.

- Another disadvantage of duopolies is that the two players may collude and increase prices for the consumer.

In a duopoly, two competing businesses control the majority of the market sector for a particular product or service they provide. A business can be part of a duopoly even if it provides other services that do not fall into that market sector. For example, Google and Meta (formerly Facebook) have dominated digital advertising for much of the 21st century, and they function as a duopoly in that field. However, Google is not associated with a duopoly in its other product sectors, such as computer software.

A duopoly is a form of oligopoly and should not be confused with a monopoly , where only a single producer exists and controls the market. With a duopoly, each company will tend to compete against the other, keeping prices lower and benefiting consumers. However, since there are only two major players in an industry under a duopoly, there is some likelihood that a monopoly could be formed, either through collusion between the two companies or if one goes out of business.

In a duopoly, oligopoly, or monopoly, the parties involved may collude and use their power to inflate prices. Since it results in consumers paying higher prices than they would in a truly competitive market, collusion is illegal under U.S. antitrust law.

A duopoly is a particular type of oligopoly, An oligopoly exists when a few businesses control the vast majority of the market sector. While a duopoly qualifies as an oligopoly, not all oligopolies are duopolies. For example, the automobile industry is an oligopoly because there are a limited number of producers, but more than two, who must respond to worldwide demand .

A duopoly should not be confused with a duopsony . In a duopoly, two competing businesses control the majority of the market sector for a particular product or service they provide. For example, Coca-Cola and Pepsi represent a duopoly because the two firms control almost the entire market for cola beverages.

A duopsony, however, is an economic condition whereby there are only two large buyers for a specific product or service. The buyers thus have considerable bargaining power and can determine market demand as long as there are plenty of firms vying to sell to them.

Intel Corp. ( INTC ) and Advanced Micro Devices Inc. ( AMD ) are an example of a duopsony. Combined, they command nearly 100% of sales in the computer processing chip market and have substantial influence over their suppliers. Duopsony is also known as a "buyer's duopoly" and is related to oligopsony , a term describing a market where there are a limited number of buyers.

Advantages and Disadvantages of a Duopoly

The two companies benefit by cooperating to improve profits.

Companies do not have to constantly engage in fruitless competition or worry about disruptors.

Prices may be controlled by the rivalry between the two companies.

Free market trading and the entrance of new companies are restricted.

Industry innovation and progress can be curtailed.

Consumers have limited options.

Price fixing and collusion may cost consumers more.

Duopolies can have both positive and negative effects on the companies in the duopoly and the consumer. First, the two companies can cooperate with each other and maximize their profits as there are no other competitors. In other words, there is a collusive cooperative equilibrium. The companies in a duopoly can concentrate on improving their existing products rather than feeling pressure to create new products for the market. Because the two companies compete with each other, the consumer benefits because prices are controlled to some extent and do not become monopoly prices.

The disadvantages of duopolies are that they limit free trade. With a duopoly, the supply of goods and services lacks diversity, and there are limited options for consumers. Also, it is difficult for other competitors to enter the industry and gain market share. The absence of competitors in a duopoly stifles innovation. With a duopoly, prices may be higher for consumers when the competition is not driving prices down.

Price fixing and collusion can occur in duopolies, which means consumers pay more and have fewer alternatives.

The two main types of duopoly are the Cournot duopoly and Bertrand duopoly.

The Cournot duopoly model states that the quantity of goods or services produced structures the competition between companies in an industry. According to the model, the two companies decide collaboratively to split the market. If one company alters its production levels, the other company must also alter its production to maintain the equilibrium of a 50/50 split of the market.

On the other hand, the Bertrand duopoly model states that price, not production quantity, structures the competition between the two firms. The model posits that consumers will choose the lower-priced product when given two choices of equal quality. This implies that the two companies in the duopoly will engage in a price war to gain market share.

Boeing and Airbus have been considered a duopoly for their command of the large passenger airplane manufacturing market. Similarly, Apple and Samsung dominate the smartphone market. While there are other companies in the business of producing passenger planes and smartphones, the market share is highly concentrated between the two businesses identified in the duopoly.

Visa ( V ) and Mastercard ( MA ) are considered a duopoly. The two financial powerhouses own over 80% of all European Union card transactions. This dominance has led the European Central Bank (ECB) to try to find ways to break up the duopoly. So far, the ECB has tried interchange fee caps, but a new scheme that would allow instant payments using national payment cards across European countries could be a game-changer.

A European infrastructure for instant payments would eliminate the need for people to use the global services of Visa or Mastercard. Another suggestion is to allow instant payments at points of interaction or points of sale so that the need for the traditional cards would disappear altogether.

A duopoly exists when two companies dominate a market for a given product or service. A duopoly can have the same impact on the market as a monopoly if the two players collude on prices or output.

An example of a duopoly is the dominance that Apple and Samsung have over the smartphone market.

A duopoly is the most basic form of oligopoly, which is a market dominated by a small number of companies.

There are plenty of examples of duopolies in today's markets—Coca-Cola and Pepsi in the soda industry and Apple and Samsung in the smartphone industry are two of them.

Duopolies are a form of oligopoly, and the biggest disadvantage of duopolies, oligopolies, and monopolies is that the companies involved can dominate markets, collude with each other, and raise prices for the consumer.

U.S. Department of Justice. " Price Fixing, Bid Rigging, and Market Allocation Schemes: What They Are and What to Look for ." Accessed Nov. 25, 2021.

Finextra. " ECB Chief Says Instant Payments Could Break Visa/Mastercard Duopoly ." Accessed Nov. 25, 2021.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-641203034-51b9f5ca223d4f7aac79eb73708dc151.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

Woolworths vs Coles: The Australian Supermarket Duopoly

Table of contents.

At the engine of our modern capitalism is competition. Companies fight for market share, customer loyalty, and survival – at the end of the day. And it’s through these epic battles, that we as consumers get better products at better prices over the long term. A great example of this sort of hard-fought competition is the rivalry between Woolworths and Coles in the Australian supermarket space.

- 995 stores

- 210,067 employees

- $44.44 AUD billions in revenue FY21 (Australian Food)

- On average 27.8 million customers served per weekN/D

- 800+ stores

- 112,269 employees

- $33.85 AUD billions in revenue FY21 (Supermarkets)

{{cta('eed3a6a3-0c12-4c96-9964-ac5329a94a27')}}

From Humble Beginnings

Woolworths opened their doors back in 1924 with a single store in Sydney, and a dream to make it big [1] . 3 years later, they opened a second store on the back of the early momentum and officially became a chain. The offering was successful from the beginning because of the perfect match with the consumer requirements at the time. The middle class was growing and as purchasing power increased, so did the demand for supermarkets. Woolworths rode this trend and rapidly scaled across the country, bringing their unique ethos and way of doing business to people the nation over.

By 1959, they had 300 stores in operation, and they had established themselves as a key player in the industry, one that had significant bargaining power when it came to dealing with vendors and suppliers of all kinds. They began to launch their own white-label brands, acquire smaller players, and quickly became a corporation that wielded immense influence in every consumer vertical that you can imagine. Everything from clothing, to food, to drinks, to household items – they worked their way into each, eventually delivering a supermarket experience that was extremely hard to beat.

In 1993, Woolworths listed on the public markets in what was Australia’s largest ever share float at the time. Once again this accelerated the growth of the company and if you fast forward to today, you can see that they haven’t slowed down since.

Coles got started ten years earlier than Woolworths (1914) with much less fanfare [2] . It was a different time economically and founder GJ Coles opened his store in Victoria with a goal of creating a simple and honest store experience for his customers. As they rode the waves of the Great Depression and the aftermath of World War II, they slowly pivoted their offering to target the married women who had now joined the workforce and were looking for a much more convenient and efficient shopping experience, due to the new time constraints.

Under this mandate, they launched themselves headfirst into a range of different industries including foodstuffs, appliances, cosmetics, and so much more. There was no limit to what they would consider and the only thing that mattered was finding out what customers wanted.

One of the key pillars of Coles' philosophy was to be altruistic wherever possible. GF Coles really wanted his creations to do good in society and he was constantly looking to find ways to donate portions of his profits to hospitals, nursing homes, relief funds, and anywhere else where there was a desperate need. He believed that businesses had a social responsibility to the communities that they operated in, and that ethos carried forward into everything they did. It felt like a safe, warm space for customers to get what they needed, while also knowing that a small piece of their shopping would go to support people in more difficult circumstances than they were.

As the years rolled on, Coles expanded their empire, transforming their early success into a national phenomenon. With every new store came better options for customers, more variety in terms of items, and a more streamlined experience all around. If you look at them today, it’s clear that they’ve come a long way from very humble beginnings, and they represent the quintessential modern supermarket chain. It’s been one hell of a ride.

Finding Their Lane

It’s easy to look at how supermarkets like Woolworths and Coles are set up today and assume that it’s always been that way. But that’s simply not the case. The supermarket industry has ebbed and flowed over the years, disrupting itself time and again, while adjusting to the changing consumer needs at every step along the journey.