How to Write a PhD Concept Paper

A concept paper – or concept note – is one of the initial requirements of a PhD programme. It is normally written during the PhD application process as well as early on in the programme once a student has been admitted.

A concept paper is basically a shorter version of a research proposal – in most cases between 2,000 and 2,500 words – that expresses the research ideas of the potential PhD student.

Besides being short, it should be concise yet have adequate details to convince the Department the student is applying to that he/she is worth being admitted to the programme.

Example of a title with a sub-title

References/bibliography, why do phd programmes require applicants to submit a concept paper.

A concept paper serves four main purposes:

- It gives the Department the student is applying to an idea of the student’s research interests.

- Based on point one, it informs the Department whether the student will be a good fit to the Department or not. To be a good fit, the research interests of the applicant should match those of the Department’s faculty.

- Based on the two points above, it enables the Department to offer support to the student throughout his/her PhD studies in the form of supervision and mentorship.

- Because the concept paper is written – and must be accepted – before the full proposal, it saves the student time and effort that would otherwise be spent on topics that may end up being rejected by the Department. A concept paper is therefore the first step to writing the PhD thesis/dissertation (see the figure below).

Format of a PhD Concept Paper

The format of a concept paper might vary from one university to another. A PhD student should therefore read the guidelines provided by his/her University of interest before writing a concept paper.

In general, the following is a common format of a concept paper:

Title of proposed study

The title of the proposed study is the first element of a concept paper.

The title should describe what the study is about by highlighting the variables of the study and the relationship between the variables if applicable.

The title should be short and specific: it is best to have a title that is not more than 15 words’ long.

Example of a title:

Use of Mobile Phone Applications for Weight Management in the United States

In order to add more specificity to the title, you can add a subtitle to the main title. The title and subtitle should be separated by a full colon.

Use of Mobile Phone Applications for Weight Management in the United States:

A Behavioural Economics’ Analysis

Background to the study

The background to the study contains the following elements:

- The history of the topic, both globally and in the proposed location of your study.

- What other researchers have found out from their own studies.

- What the gaps in the existing literature are, that is, what the other researchers have not addressed.

- What your study will contribute towards filling the identified gaps.

The implication of the above is that one must have conducted some literature review prior to writing the background to the study.

Statement of the problem

The statement of the problem is a clear description of the issue that the study will address, the relevance of the issue, the importance (benefits) of addressing the issue, and the method the researcher will use to address the issue.

Goal and objectives of the study

Once you have identified the problem of your study, the next step is to write the goal and objectives of the study. There is a difference between these two:

The goal of the study is a broad statement of what the researcher hopes to accomplish at the end of the study. The goal should also be related to the problem statement.

Any given project should have one goal because having many goals would lead to confusion. However, that one goal can have multiple elements in it, which would be accomplished through the project’s objectives.

The objectives of the study, on the other hand, are specific and detailed statements of how the researcher will go about accomplishing the stated goal.

The objectives should:

- Support the accomplishment of the goal.

- Follow a sequence, that is, like a step-by-step order. This will help you frame the activities needed to be undertaken in a logical manner so that the goal is achieved.

- Be stated using action verbs, for instance, “to identify”, “to create”, “to establish”, “to measure”, etc.

- Be about 3-4: having too few of objectives will limit the scope of your PhD dissertation, while having too many objectives may complicate the dissertation.

- Be SMART, that is, Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, and Time-bound.

The video below clearly explains how to set SMART goals and objectives:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MAhs-m6cNzY

Important tip 1: depending on your PhD programme, you may be required to have at least 3 journal papers to qualify for graduation. Each of your objectives can be converted into a separate journal paper on its own.

Research questions and hypotheses

Every PhD dissertation needs research questions. Research questions will help the student stay focused on his/her research.

The aim of the research is to provide answers to the research questions. The answers to the questions will form the thesis statement.

Examples of research questions:

In the title example given earlier about use of mobile phone applications for weight management in the United States, a student may be interested in the following questions:

- To what extent do adults in the United States use mobile phone applications to manage their weight?

- Is there any gender disparity in the use of mobile phone apps for weight management in the United States?

- How effective are mobile apps for weight management in the United States?

Good research questions are those that can be explored deeply and widely as well as defended using evidence. Questions with ‘yes” or “no” responses are not academic-worthy.

When developing research questions, you also need to think about the data that will be required to answer the questions. Do you have access to that data? If no, will your time and financial resources allow you to collect that data?

Important tip 2: Your PhD study is time-limited therefore data requirement issues need to be thought through at the initial stages of your concept paper writing so that you don’t waste too much time either collecting the data in the future or trying to access the data if it already exists elsewhere.

Preliminary literature review

At the concept paper stage, a preliminary literature review serves three main purposes:

- It shows whether you have knowledge of the current state of debate about your chosen topic.

- It shows whether you are familiar with the experts in your chosen topic.

- It also helps you identify the research gaps.

Proposed research design, methods and procedures

This sections provides a brief overview of the research methodology that you will adopt in your study. Some issues to consider include:

- Will your study use quantitative, qualitative or mixed-methods approach?

- Will you use secondary or primary data?

- What will be the sources of your data? Will you need any ethical clearance from your university before collecting data?

- Will the data sources be readily accessible?

- Will you use external assistance for data collection? Or will you do all the data collection yourself?

- How will the data be analysed? Which softwares will you use? Are you competent in those softwares?

While the above issues are important to think through, please note that the research design and methods will be informed by your research objectives and research questions. As an illustration:

A research question that aims to measure the effect of one (or more) variable(s) on another variable will definitely require quantitative research methods.

On the other hand, a research question that aims to explain the existence of a phenomenon will render itself to the use of qualitative research methods.

Contribution to knowledge

This is perhaps the most important aspect of a PhD dissertation. Your concept note needs to briefly highlight how your project will add value to knowledge.

Making significant contribution to knowledge at the PhD level does not mean a Nobel prize standard of knowledge (this you can do after your PhD when you’ll have all the time in the world to do so). You can achieve this in various ways:

- New applications of existing ideas.

- New interpretations of previous ideas.

- Investigating an existing issue in a new location.

- Development of a new theory.

- Coming up with a new technique, among others.

The last section of the concept paper is the reference list or bibliography. This is the section that lists the literatures that you have reviewed and cited in your paper.

There is a slight difference between a reference list and a bibliography:

A reference list includes all those studies that have been directly cited in the paper.

A bibliography, on the other hand, includes all those studies that have been directly cited in the paper as well as those that were reviewed and consulted but not cited in the paper.

When creating the reference list/bibliography, one should be mindful of the referencing style that is required by their PhD department (that is, whether APA, MLA, Chicago, Havard, etc).

Final Thoughts on Writing a PhD Concept Paper

The concept paper is the first step to writing the PhD dissertation. Once accepted, the student will proceed to writing the proposal, which will then be defended before proceeding with writing the full dissertation.

The concept paper is a mini-proposal and has most of the components expected in the proposal.

However, the concept paper should be short and precise while at the same time have adequate information to enable the PhD Committee of the PhD Programme the student is applying to judge if the student will be a good fit to the programme or not.

Related posts

How To Choose a Research Topic For Your PhD Thesis (7 Key Factors to Consider)

Comprehensive Guidelines for Writing a PhD Thesis Proposal (+ free checklist for PhD Students)

Grace Njeri-Otieno

Grace Njeri-Otieno is a Kenyan, a wife, a mom, and currently a PhD student, among many other balls she juggles. She holds a Bachelors' and Masters' degrees in Economics and has more than 7 years' experience with an INGO. She was inspired to start this site so as to share the lessons learned throughout her PhD journey with other PhD students. Her vision for this site is "to become a go-to resource center for PhD students in all their spheres of learning."

Recent Content

SPSS Tutorial #12: Partial Correlation Analysis in SPSS

Partial correlation is almost similar to Pearson product-moment correlation only that it accounts for the influence of another variable, which is thought to be correlated with the two variables of...

SPSS Tutorial #11: Correlation Analysis in SPSS

In this post, I discuss what correlation is, the two most common types of correlation statistics used (Pearson and Spearman), and how to conduct correlation analysis in SPSS. What is correlation...

How To Write A Dissertation Or Thesis

8 straightforward steps to craft an a-grade dissertation.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) Expert Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020

Writing a dissertation or thesis is not a simple task. It takes time, energy and a lot of will power to get you across the finish line. It’s not easy – but it doesn’t necessarily need to be a painful process. If you understand the big-picture process of how to write a dissertation or thesis, your research journey will be a lot smoother.

In this post, I’m going to outline the big-picture process of how to write a high-quality dissertation or thesis, without losing your mind along the way. If you’re just starting your research, this post is perfect for you. Alternatively, if you’ve already submitted your proposal, this article which covers how to structure a dissertation might be more helpful.

How To Write A Dissertation: 8 Steps

- Clearly understand what a dissertation (or thesis) is

- Find a unique and valuable research topic

- Craft a convincing research proposal

- Write up a strong introduction chapter

- Review the existing literature and compile a literature review

- Design a rigorous research strategy and undertake your own research

- Present the findings of your research

- Draw a conclusion and discuss the implications

Step 1: Understand exactly what a dissertation is

This probably sounds like a no-brainer, but all too often, students come to us for help with their research and the underlying issue is that they don’t fully understand what a dissertation (or thesis) actually is.

So, what is a dissertation?

At its simplest, a dissertation or thesis is a formal piece of research , reflecting the standard research process . But what is the standard research process, you ask? The research process involves 4 key steps:

- Ask a very specific, well-articulated question (s) (your research topic)

- See what other researchers have said about it (if they’ve already answered it)

- If they haven’t answered it adequately, undertake your own data collection and analysis in a scientifically rigorous fashion

- Answer your original question(s), based on your analysis findings

In short, the research process is simply about asking and answering questions in a systematic fashion . This probably sounds pretty obvious, but people often think they’ve done “research”, when in fact what they have done is:

- Started with a vague, poorly articulated question

- Not taken the time to see what research has already been done regarding the question

- Collected data and opinions that support their gut and undertaken a flimsy analysis

- Drawn a shaky conclusion, based on that analysis

If you want to see the perfect example of this in action, look out for the next Facebook post where someone claims they’ve done “research”… All too often, people consider reading a few blog posts to constitute research. Its no surprise then that what they end up with is an opinion piece, not research. Okay, okay – I’ll climb off my soapbox now.

The key takeaway here is that a dissertation (or thesis) is a formal piece of research, reflecting the research process. It’s not an opinion piece , nor a place to push your agenda or try to convince someone of your position. Writing a good dissertation involves asking a question and taking a systematic, rigorous approach to answering it.

If you understand this and are comfortable leaving your opinions or preconceived ideas at the door, you’re already off to a good start!

Step 2: Find a unique, valuable research topic

As we saw, the first step of the research process is to ask a specific, well-articulated question. In other words, you need to find a research topic that asks a specific question or set of questions (these are called research questions ). Sounds easy enough, right? All you’ve got to do is identify a question or two and you’ve got a winning research topic. Well, not quite…

A good dissertation or thesis topic has a few important attributes. Specifically, a solid research topic should be:

Let’s take a closer look at these:

Attribute #1: Clear

Your research topic needs to be crystal clear about what you’re planning to research, what you want to know, and within what context. There shouldn’t be any ambiguity or vagueness about what you’ll research.

Here’s an example of a clearly articulated research topic:

An analysis of consumer-based factors influencing organisational trust in British low-cost online equity brokerage firms.

As you can see in the example, its crystal clear what will be analysed (factors impacting organisational trust), amongst who (consumers) and in what context (British low-cost equity brokerage firms, based online).

Need a helping hand?

Attribute #2: Unique

Your research should be asking a question(s) that hasn’t been asked before, or that hasn’t been asked in a specific context (for example, in a specific country or industry).

For example, sticking organisational trust topic above, it’s quite likely that organisational trust factors in the UK have been investigated before, but the context (online low-cost equity brokerages) could make this research unique. Therefore, the context makes this research original.

One caveat when using context as the basis for originality – you need to have a good reason to suspect that your findings in this context might be different from the existing research – otherwise, there’s no reason to warrant researching it.

Attribute #3: Important

Simply asking a unique or original question is not enough – the question needs to create value. In other words, successfully answering your research questions should provide some value to the field of research or the industry. You can’t research something just to satisfy your curiosity. It needs to make some form of contribution either to research or industry.

For example, researching the factors influencing consumer trust would create value by enabling businesses to tailor their operations and marketing to leverage factors that promote trust. In other words, it would have a clear benefit to industry.

So, how do you go about finding a unique and valuable research topic? We explain that in detail in this video post – How To Find A Research Topic . Yeah, we’ve got you covered 😊

Step 3: Write a convincing research proposal

Once you’ve pinned down a high-quality research topic, the next step is to convince your university to let you research it. No matter how awesome you think your topic is, it still needs to get the rubber stamp before you can move forward with your research. The research proposal is the tool you’ll use for this job.

So, what’s in a research proposal?

The main “job” of a research proposal is to convince your university, advisor or committee that your research topic is worthy of approval. But convince them of what? Well, this varies from university to university, but generally, they want to see that:

- You have a clearly articulated, unique and important topic (this might sound familiar…)

- You’ve done some initial reading of the existing literature relevant to your topic (i.e. a literature review)

- You have a provisional plan in terms of how you will collect data and analyse it (i.e. a methodology)

At the proposal stage, it’s (generally) not expected that you’ve extensively reviewed the existing literature , but you will need to show that you’ve done enough reading to identify a clear gap for original (unique) research. Similarly, they generally don’t expect that you have a rock-solid research methodology mapped out, but you should have an idea of whether you’ll be undertaking qualitative or quantitative analysis , and how you’ll collect your data (we’ll discuss this in more detail later).

Long story short – don’t stress about having every detail of your research meticulously thought out at the proposal stage – this will develop as you progress through your research. However, you do need to show that you’ve “done your homework” and that your research is worthy of approval .

So, how do you go about crafting a high-quality, convincing proposal? We cover that in detail in this video post – How To Write A Top-Class Research Proposal . We’ve also got a video walkthrough of two proposal examples here .

Step 4: Craft a strong introduction chapter

Once your proposal’s been approved, its time to get writing your actual dissertation or thesis! The good news is that if you put the time into crafting a high-quality proposal, you’ve already got a head start on your first three chapters – introduction, literature review and methodology – as you can use your proposal as the basis for these.

Handy sidenote – our free dissertation & thesis template is a great way to speed up your dissertation writing journey.

What’s the introduction chapter all about?

The purpose of the introduction chapter is to set the scene for your research (dare I say, to introduce it…) so that the reader understands what you’ll be researching and why it’s important. In other words, it covers the same ground as the research proposal in that it justifies your research topic.

What goes into the introduction chapter?

This can vary slightly between universities and degrees, but generally, the introduction chapter will include the following:

- A brief background to the study, explaining the overall area of research

- A problem statement , explaining what the problem is with the current state of research (in other words, where the knowledge gap exists)

- Your research questions – in other words, the specific questions your study will seek to answer (based on the knowledge gap)

- The significance of your study – in other words, why it’s important and how its findings will be useful in the world

As you can see, this all about explaining the “what” and the “why” of your research (as opposed to the “how”). So, your introduction chapter is basically the salesman of your study, “selling” your research to the first-time reader and (hopefully) getting them interested to read more.

How do I write the introduction chapter, you ask? We cover that in detail in this post .

Step 5: Undertake an in-depth literature review

As I mentioned earlier, you’ll need to do some initial review of the literature in Steps 2 and 3 to find your research gap and craft a convincing research proposal – but that’s just scratching the surface. Once you reach the literature review stage of your dissertation or thesis, you need to dig a lot deeper into the existing research and write up a comprehensive literature review chapter.

What’s the literature review all about?

There are two main stages in the literature review process:

Literature Review Step 1: Reading up

The first stage is for you to deep dive into the existing literature (journal articles, textbook chapters, industry reports, etc) to gain an in-depth understanding of the current state of research regarding your topic. While you don’t need to read every single article, you do need to ensure that you cover all literature that is related to your core research questions, and create a comprehensive catalogue of that literature , which you’ll use in the next step.

Reading and digesting all the relevant literature is a time consuming and intellectually demanding process. Many students underestimate just how much work goes into this step, so make sure that you allocate a good amount of time for this when planning out your research. Thankfully, there are ways to fast track the process – be sure to check out this article covering how to read journal articles quickly .

Literature Review Step 2: Writing up

Once you’ve worked through the literature and digested it all, you’ll need to write up your literature review chapter. Many students make the mistake of thinking that the literature review chapter is simply a summary of what other researchers have said. While this is partly true, a literature review is much more than just a summary. To pull off a good literature review chapter, you’ll need to achieve at least 3 things:

- You need to synthesise the existing research , not just summarise it. In other words, you need to show how different pieces of theory fit together, what’s agreed on by researchers, what’s not.

- You need to highlight a research gap that your research is going to fill. In other words, you’ve got to outline the problem so that your research topic can provide a solution.

- You need to use the existing research to inform your methodology and approach to your own research design. For example, you might use questions or Likert scales from previous studies in your your own survey design .

As you can see, a good literature review is more than just a summary of the published research. It’s the foundation on which your own research is built, so it deserves a lot of love and attention. Take the time to craft a comprehensive literature review with a suitable structure .

But, how do I actually write the literature review chapter, you ask? We cover that in detail in this video post .

Step 6: Carry out your own research

Once you’ve completed your literature review and have a sound understanding of the existing research, its time to develop your own research (finally!). You’ll design this research specifically so that you can find the answers to your unique research question.

There are two steps here – designing your research strategy and executing on it:

1 – Design your research strategy

The first step is to design your research strategy and craft a methodology chapter . I won’t get into the technicalities of the methodology chapter here, but in simple terms, this chapter is about explaining the “how” of your research. If you recall, the introduction and literature review chapters discussed the “what” and the “why”, so it makes sense that the next point to cover is the “how” –that’s what the methodology chapter is all about.

In this section, you’ll need to make firm decisions about your research design. This includes things like:

- Your research philosophy (e.g. positivism or interpretivism )

- Your overall methodology (e.g. qualitative , quantitative or mixed methods)

- Your data collection strategy (e.g. interviews , focus groups, surveys)

- Your data analysis strategy (e.g. content analysis , correlation analysis, regression)

If these words have got your head spinning, don’t worry! We’ll explain these in plain language in other posts. It’s not essential that you understand the intricacies of research design (yet!). The key takeaway here is that you’ll need to make decisions about how you’ll design your own research, and you’ll need to describe (and justify) your decisions in your methodology chapter.

2 – Execute: Collect and analyse your data

Once you’ve worked out your research design, you’ll put it into action and start collecting your data. This might mean undertaking interviews, hosting an online survey or any other data collection method. Data collection can take quite a bit of time (especially if you host in-person interviews), so be sure to factor sufficient time into your project plan for this. Oftentimes, things don’t go 100% to plan (for example, you don’t get as many survey responses as you hoped for), so bake a little extra time into your budget here.

Once you’ve collected your data, you’ll need to do some data preparation before you can sink your teeth into the analysis. For example:

- If you carry out interviews or focus groups, you’ll need to transcribe your audio data to text (i.e. a Word document).

- If you collect quantitative survey data, you’ll need to clean up your data and get it into the right format for whichever analysis software you use (for example, SPSS, R or STATA).

Once you’ve completed your data prep, you’ll undertake your analysis, using the techniques that you described in your methodology. Depending on what you find in your analysis, you might also do some additional forms of analysis that you hadn’t planned for. For example, you might see something in the data that raises new questions or that requires clarification with further analysis.

The type(s) of analysis that you’ll use depend entirely on the nature of your research and your research questions. For example:

- If your research if exploratory in nature, you’ll often use qualitative analysis techniques .

- If your research is confirmatory in nature, you’ll often use quantitative analysis techniques

- If your research involves a mix of both, you might use a mixed methods approach

Again, if these words have got your head spinning, don’t worry! We’ll explain these concepts and techniques in other posts. The key takeaway is simply that there’s no “one size fits all” for research design and methodology – it all depends on your topic, your research questions and your data. So, don’t be surprised if your study colleagues take a completely different approach to yours.

Step 7: Present your findings

Once you’ve completed your analysis, it’s time to present your findings (finally!). In a dissertation or thesis, you’ll typically present your findings in two chapters – the results chapter and the discussion chapter .

What’s the difference between the results chapter and the discussion chapter?

While these two chapters are similar, the results chapter generally just presents the processed data neatly and clearly without interpretation, while the discussion chapter explains the story the data are telling – in other words, it provides your interpretation of the results.

For example, if you were researching the factors that influence consumer trust, you might have used a quantitative approach to identify the relationship between potential factors (e.g. perceived integrity and competence of the organisation) and consumer trust. In this case:

- Your results chapter would just present the results of the statistical tests. For example, correlation results or differences between groups. In other words, the processed numbers.

- Your discussion chapter would explain what the numbers mean in relation to your research question(s). For example, Factor 1 has a weak relationship with consumer trust, while Factor 2 has a strong relationship.

Depending on the university and degree, these two chapters (results and discussion) are sometimes merged into one , so be sure to check with your institution what their preference is. Regardless of the chapter structure, this section is about presenting the findings of your research in a clear, easy to understand fashion.

Importantly, your discussion here needs to link back to your research questions (which you outlined in the introduction or literature review chapter). In other words, it needs to answer the key questions you asked (or at least attempt to answer them).

For example, if we look at the sample research topic:

In this case, the discussion section would clearly outline which factors seem to have a noteworthy influence on organisational trust. By doing so, they are answering the overarching question and fulfilling the purpose of the research .

For more information about the results chapter , check out this post for qualitative studies and this post for quantitative studies .

Step 8: The Final Step Draw a conclusion and discuss the implications

Last but not least, you’ll need to wrap up your research with the conclusion chapter . In this chapter, you’ll bring your research full circle by highlighting the key findings of your study and explaining what the implications of these findings are.

What exactly are key findings? The key findings are those findings which directly relate to your original research questions and overall research objectives (which you discussed in your introduction chapter). The implications, on the other hand, explain what your findings mean for industry, or for research in your area.

Sticking with the consumer trust topic example, the conclusion might look something like this:

Key findings

This study set out to identify which factors influence consumer-based trust in British low-cost online equity brokerage firms. The results suggest that the following factors have a large impact on consumer trust:

While the following factors have a very limited impact on consumer trust:

Notably, within the 25-30 age groups, Factors E had a noticeably larger impact, which may be explained by…

Implications

The findings having noteworthy implications for British low-cost online equity brokers. Specifically:

The large impact of Factors X and Y implies that brokers need to consider….

The limited impact of Factor E implies that brokers need to…

As you can see, the conclusion chapter is basically explaining the “what” (what your study found) and the “so what?” (what the findings mean for the industry or research). This brings the study full circle and closes off the document.

Let’s recap – how to write a dissertation or thesis

You’re still with me? Impressive! I know that this post was a long one, but hopefully you’ve learnt a thing or two about how to write a dissertation or thesis, and are now better equipped to start your own research.

To recap, the 8 steps to writing a quality dissertation (or thesis) are as follows:

- Understand what a dissertation (or thesis) is – a research project that follows the research process.

- Find a unique (original) and important research topic

- Craft a convincing dissertation or thesis research proposal

- Write a clear, compelling introduction chapter

- Undertake a thorough review of the existing research and write up a literature review

- Undertake your own research

- Present and interpret your findings

Once you’ve wrapped up the core chapters, all that’s typically left is the abstract , reference list and appendices. As always, be sure to check with your university if they have any additional requirements in terms of structure or content.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

20 Comments

thankfull >>>this is very useful

Thank you, it was really helpful

unquestionably, this amazing simplified way of teaching. Really , I couldn’t find in the literature words that fully explicit my great thanks to you. However, I could only say thanks a-lot.

Great to hear that – thanks for the feedback. Good luck writing your dissertation/thesis.

This is the most comprehensive explanation of how to write a dissertation. Many thanks for sharing it free of charge.

Very rich presentation. Thank you

Thanks Derek Jansen|GRADCOACH, I find it very useful guide to arrange my activities and proceed to research!

Thank you so much for such a marvelous teaching .I am so convinced that am going to write a comprehensive and a distinct masters dissertation

It is an amazing comprehensive explanation

This was straightforward. Thank you!

I can say that your explanations are simple and enlightening – understanding what you have done here is easy for me. Could you write more about the different types of research methods specific to the three methodologies: quan, qual and MM. I look forward to interacting with this website more in the future.

Thanks for the feedback and suggestions 🙂

Hello, your write ups is quite educative. However, l have challenges in going about my research questions which is below; *Building the enablers of organisational growth through effective governance and purposeful leadership.*

Very educating.

Just listening to the name of the dissertation makes the student nervous. As writing a top-quality dissertation is a difficult task as it is a lengthy topic, requires a lot of research and understanding and is usually around 10,000 to 15000 words. Sometimes due to studies, unbalanced workload or lack of research and writing skill students look for dissertation submission from professional writers.

Thank you 💕😊 very much. I was confused but your comprehensive explanation has cleared my doubts of ever presenting a good thesis. Thank you.

thank you so much, that was so useful

Hi. Where is the excel spread sheet ark?

could you please help me look at your thesis paper to enable me to do the portion that has to do with the specification

my topic is “the impact of domestic revenue mobilization.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Community Blog

Keep up-to-date on postgraduate related issues with our quick reads written by students, postdocs, professors and industry leaders.

What is a Concept Paper and How do You Write One?

- By DiscoverPhDs

- August 26, 2020

What is a Concept Paper?

A concept paper is a short document written by a researcher before starting their research project, with the purpose of explaining what the study is about, why it is important and the methods that will be used.

The concept paper will include your proposed research title, a brief introduction to the subject, the aim of the study, the research questions you intend to answer, the type of data you will collect and how you will collect it. A concept paper can also be referred to as a research proposal.

What is the Purpose of a Concept Paper?

The primary aim of a research concept paper is to convince the reader that the proposed research project is worth doing. This means that the reader should first agree that the research study is novel and interesting. They should be convinced that there is a need for this research and that the research aims and questions are appropriate.

Finally, they should be satisfied that the methods for data collection proposed are feasible, are likely to work and can be performed within the specific time period allocated for this project.

The three main scenarios in which you may need to write a concept paper are if you are:

- A final year undergraduate or master’s student preparing to start a research project with a supervisor.

- A student submitting a research proposal to pursue a PhD project under the supervision of a professor.

- A principal investigator submitting a proposal to a funding body to secure financial support for a research project.

How Long is a Concept Paper?

The concept paper format is usually between 2 and 3 pages in length for students writing proposals for undergraduate, master’s or PhD projects. Concept papers written as part of funding applications may be over 20 pages in length.

How do you Write a Concept Paper?

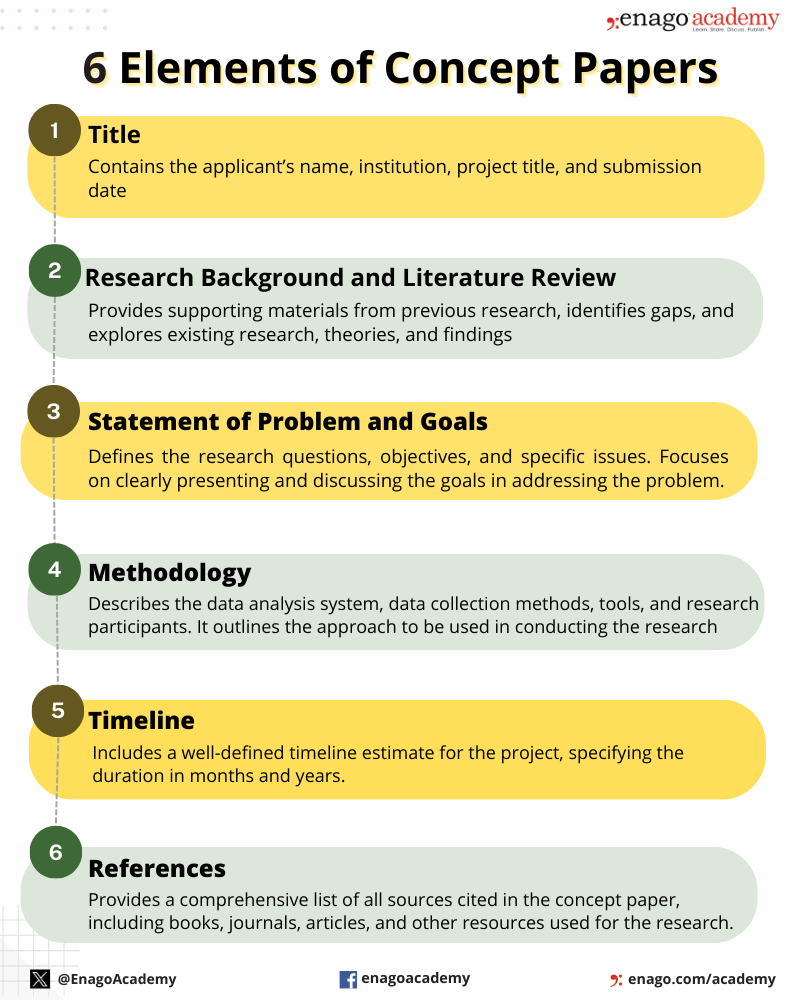

There are 6 important aspects to consider when writing a concept paper or research proposal:

- 1. The wording of the title page, which is best presented as a question for this type of document. At this study concept stage, you can write the title a bit catchier, for example “Are 3D Printed Engine Parts Safe for Use in Aircraft?”.

- A brief introduction and review of relevant existing literature published within the subject area and identification of where the gaps in knowledge are. This last bit is particularly important as it guides you in defining the statement of the problem. The concept paper should provide a succinct summary of ‘the problem’, which is usually related to what is unknown or poorly understood about your research topic . By the end of the concept paper, the reader should be clear on how your research idea will provide a ‘solution’ to this problem.

- The overarching research aim of your proposed study and the objectives and/or questions you will address to achieve this aim. Align all of these with the problem statement; i.e. write each research question as a clear response to addressing the limitations and gaps identified from previous literature. Also give a clear description of your primary hypothesis.

- The specific data outputs that you plan to capture. For example, will this be qualitative or quantitative data? Do you plan to capture data at specific time points or at other defined intervals? Do you need to repeat data capture to asses any repeatability and reproducibility questions?

- The research methodology you will use to capture this data, including any specific measurement or analysis equipment and software you will use, and a consideration of statistical tests to help interpret the data. If your research requires the use of questionnaires, how will these be prepared and validated? In what sort of time frame would you plan to collect this data?

- Finally, include a statement of the significance of the study , explaining why your research is important and impactful. This can be in the form of a concluding paragraph that reiterate the statement of the problem, clarifies how your research will address this and explains who will benefit from your research and how.

You may need to include a short summary of the timeline for completing the research project. Defining milestones of the time points at which you intend to complete certain tasks can help to show that you’ve considered the practicalities of running this study. It also shows that what you have proposed is feasible in order to achieve your research goal.

If you’re pitching your proposed project to a funder, they may allocate a proportion of the money based on the satisfactory outcome of each milestone. These stakeholders may also be motivated by knowing that you intend to convert your dissertation into an article for journal publication; this level of dissemination is of high importance to them.

Additionally, you may be asked to provide a brief summary of the projected costs of running the study. For a PhD project this could be the bench fees associated with consumables and the cost of any travel if required.

Make sure to include references and cite all other literature and previous research that you discuss in your concept paper.

This guide gave you an overview of the key elements you need to know about when writing concept papers. The purpose of these are first to convey to the reader what your project’s purpose is and why your research topic is important; this is based on the development of a problem statement using evidence from your literature review.

Explain how it may positively impact your research field and if your proposed research design is appropriate and your planned research method achievable.

This post explains where and how to write the list of figures in your thesis or dissertation.

The term rationale of research means the reason for performing the research study in question.

Impostor Syndrome is a common phenomenon amongst PhD students, leading to self-doubt and fear of being exposed as a “fraud”. How can we overcome these feelings?

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Browse PhDs Now

Learn more about using cloud storage effectively, video conferencing calling, good note-taking solutions and online calendar and task management options.

The scope and delimitations of a thesis, dissertation or paper define the topic and boundaries of a research problem – learn how to form them.

Emma is a third year PhD student at the University of Rhode Island. Her research focuses on the physiological and genomic response to climate change stressors.

Ellie is a final year PhD student at the University of Hertfordshire, investigating a protein which is implicated in pancreatic cancer; this work can improve the efficacy of cancer drug treatments.

Join Thousands of Students

Concept Papers in Research: Deciphering the blueprint of brilliance

Concept papers hold significant importance as a precursor to a full-fledged research proposal in academia and research. Understanding the nuances and significance of a concept paper is essential for any researcher aiming to lay a strong foundation for their investigation.

Table of Contents

What Is Concept Paper

A concept paper can be defined as a concise document which outlines the fundamental aspects of a grant proposal. It outlines the initial ideas, objectives, and theoretical framework of a proposed research project. It is usually two to three-page long overview of the proposal. However, they differ from both research proposal and original research paper in lacking a detailed plan and methodology for a specific study as in research proposal provides and exclusion of the findings and analysis of a completed research project as in an original research paper. A concept paper primarily focuses on introducing the basic idea, intended research question, and the framework that will guide the research.

Purpose of a Concept Paper

A concept paper serves as an initial document, commonly required by private organizations before a formal proposal submission. It offers a preliminary overview of a project or research’s purpose, method, and implementation. It acts as a roadmap, providing clarity and coherence in research direction. Additionally, it also acts as a tool for receiving informal input. The paper is used for internal decision-making, seeking approval from the board, and securing commitment from partners. It promotes cohesive communication and serves as a professional and respectful tool in collaboration.

These papers aid in focusing on the core objectives, theoretical underpinnings, and potential methodology of the research, enabling researchers to gain initial feedback and refine their ideas before delving into detailed research.

Key Elements of a Concept Paper

Key elements of a concept paper include the title page , background , literature review , problem statement , methodology, timeline, and references. It’s crucial for researchers seeking grants as it helps evaluators assess the relevance and feasibility of the proposed research.

Writing an effective concept paper in academic research involves understanding and incorporating essential elements:

How to Write a Concept Paper?

To ensure an effective concept paper, it’s recommended to select a compelling research topic, pose numerous research questions and incorporate data and numbers to support the project’s rationale. The document must be concise (around five pages) after tailoring the content and following the formatting requirements. Additionally, infographics and scientific illustrations can enhance the document’s impact and engagement with the audience. The steps to write a concept paper are as follows:

1. Write a Crisp Title:

Choose a clear, descriptive title that encapsulates the main idea. The title should express the paper’s content. It should serve as a preview for the reader.

2. Provide a Background Information:

Give a background information about the issue or topic. Define the key terminologies or concepts. Review existing literature to identify the gaps your concept paper aims to fill.

3. Outline Contents in the Introduction:

Introduce the concept paper with a brief overview of the problem or idea you’re addressing. Explain its significance. Identify the specific knowledge gaps your research aims to address and mention any contradictory theories related to your research question.

4. Define a Mission Statement:

The mission statement follows a clear problem statement that defines the problem or concept that need to be addressed. Write a concise mission statement that engages your research purpose and explains why gaining the reader’s approval will benefit your field.

5. Explain the Research Aim and Objectives:

Explain why your research is important and the specific questions you aim to answer through your research. State the specific goals and objectives your concept intends to achieve. Provide a detailed explanation of your concept. What is it, how does it work, and what makes it unique?

6. Detail the Methodology:

Discuss the research methods you plan to use, such as surveys, experiments, case studies, interviews, and observations. Mention any ethical concerns related to your research.

7. Outline Proposed Methods and Potential Impact:

Provide detailed information on how you will conduct your research, including any specialized equipment or collaborations. Discuss the expected results or impacts of implementing the concept. Highlight the potential benefits, whether social, economic, or otherwise.

8. Mention the Feasibility

Discuss the resources necessary for the concept’s execution. Mention the expected duration of the research and specific milestones. Outline a proposed timeline for implementing the concept.

9. Include a Support Section:

Include a section that breaks down the project’s budget, explaining the overall cost and individual expenses to demonstrate how the allocated funds will be used.

10. Provide a Conclusion:

Summarize the key points and restate the importance of the concept. If necessary, include a call to action or next steps.

Although the structure and elements of a concept paper may vary depending on the specific requirements, you can tailor your document based on the guidelines or instructions you’ve been given.

Here are some tips to write a concept paper:

Example of a Concept Paper

Here is an example of a concept paper. Please note, this is a generalized example. Your concept paper should align with the specific requirements, guidelines, and objectives you aim to achieve in your proposal. Tailor it accordingly to the needs and context of the initiative you are proposing.

Download Now!

Importance of a Concept Paper

Concept papers serve various fields, influencing the direction and potential of research in science, social sciences, technology, and more. They contribute to the formulation of groundbreaking studies and novel ideas that can impact societal, economic, and academic spheres.

A concept paper serves several crucial purposes in various fields:

In summary, a well-crafted concept paper is essential in outlining a clear, concise, and structured framework for new ideas or proposals. It helps in assessing the feasibility, viability, and potential impact of the concept before investing significant resources into its implementation.

How well do you understand concept papers? Test your understanding now!

Fill the Details to Check Your Score

Role of AI in Writing Concept Papers

The increasing use of AI, particularly generative models, has facilitated the writing process for concept papers. Responsible use involves leveraging AI to assist in ideation, organization, and language refinement while ensuring that the originality and ethical standards of research are maintained.

AI plays a significant role in aiding the creation and development of concept papers in several ways:

1. Idea Generation and Organization

AI tools can assist in brainstorming initial ideas for concept papers based on key concepts. They can help in organizing information, creating outlines, and structuring the content effectively.

2. Summarizing Research and Data Analysis

AI-powered tools can assist in conducting comprehensive literature reviews, helping writers to gather and synthesize relevant information. AI algorithms can process and analyze vast amounts of data, providing insights and statistics to support the concept presented in the paper.

3. Language and Style Enhancement

AI grammar checker tools can help writers by offering grammar, style, and tone suggestions, ensuring professionalism. It can also facilitate translation, in case a global collaboration.

4. Collaboration and Feedback

AI platforms offer collaborative features that enable multiple authors to work simultaneously on a concept paper, allowing for real-time contributions and edits.

5. Customization and Personalization

AI algorithms can provide personalized recommendations based on the specific requirements or context of the concept paper. They can assist in tailoring the concept paper according to the target audience or specific guidelines.

6. Automation and Efficiency

AI can automate certain tasks, such as citation formatting, bibliography creation, or reference checking, saving time for the writer.

7. Analytics and Prediction

AI models can predict potential outcomes or impacts based on the information provided, helping writers anticipate the possible consequences of the proposed concept.

8. Real-Time Assistance

AI-driven chat-bots can provide real-time support and answers to specific questions related to the concept paper writing process.

AI’s role in writing concept papers significantly streamlines the writing process, enhances the quality of the content, and provides valuable assistance in various stages of development, contributing to the overall effectiveness of the final document.

Concept papers serve as the stepping stone in the research journey, aiding in the crystallization of ideas and the formulation of robust research proposals. It the cornerstone for translating ideas into impactful realities. Their significance spans diverse domains, from academia to business, enabling stakeholders to evaluate, invest, and realize the potential of groundbreaking concepts.

Frequently Asked Questions

A concept paper can be defined as a concise document outlining the fundamental aspects of a grant proposal such as the initial ideas, objectives, and theoretical framework of a proposed research project.

A good concept paper should offer a clear and comprehensive overview of the proposed research. It should demonstrate a strong understanding of the subject matter and outline a structured plan for its execution.

Concept paper is important to develop and clarify ideas, develop and evaluate proposal, inviting collaboration and collecting feedback, presenting proposals for academic and research initiatives and allocating resources.

I got wonderful idea

It helps a lot for my concept paper.

Information is key to the guidelines of a concept paper

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Career Corner

Academic Webinars: Transforming knowledge dissemination in the digital age

Digitization has transformed several areas of our lives, including the teaching and learning process. During…

- Manuscripts & Grants

- Reporting Research

Mastering Research Grant Writing in 2024: Navigating new policies and funder demands

Entering the world of grants and government funding can leave you confused; especially when trying…

How to Create a Poster That Stands Out: Tips for a smooth poster presentation

It was the conference season. Judy was excited to present her first poster! She had…

Academic Essay Writing Made Simple: 4 types and tips

The pen is mightier than the sword, they say, and nowhere is this more evident…

![dissertation concept note What is Academic Integrity and How to Uphold it [FREE CHECKLIST]](https://www.enago.com/academy/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/FeatureImages-59-210x136.png)

Ensuring Academic Integrity and Transparency in Academic Research: A comprehensive checklist for researchers

Academic integrity is the foundation upon which the credibility and value of scientific findings are…

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

- Industry News

- Publishing Research

- AI in Academia

- Promoting Research

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Infographics

- Expert Video Library

- Other Resources

- Enago Learn

- Upcoming & On-Demand Webinars

- Peer Review Week 2024

- Open Access Week 2023

- Conference Videos

- Enago Report

- Journal Finder

- Enago Plagiarism & AI Grammar Check

- Editing Services

- Publication Support Services

- Research Impact

- Translation Services

- Publication solutions

- AI-Based Solutions

- Thought Leadership

- Call for Articles

- Call for Speakers

- Author Training

- Edit Profile

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

In your opinion, what is the most effective way to improve integrity in the peer review process?

Stay ahead of the AI revolution.

How to Write a Concept Note: A Step-by-Step Guide

Concept notes are important documents that serve as a brief outline of a project. They are used to present a proposed project to potential stakeholders and funders, and are usually requested before a full project proposal is submitted. If you are planning to embark on a new project, it is essential to know how to write a concept note. In this guide, we'll take you through the step-by-step process of writing a winning concept note.

Understanding the Purpose of a Concept Note

Before we delve into the details of how to write a concept note, it is important to understand its purpose. A concept note serves several functions:

What is a Concept Note?

A concept note is a brief outline of a project proposal, usually submitted to potential stakeholders and funders to solicit their support.

Let’s take an example of a non-profit organization that wants to start a new project to provide education to underprivileged children. The organization will need funding and support from donors to make this project a success. To attract potential donors, the organization will need to submit a concept note that outlines the basic details of the project.

Why is a Concept Note Important?

Concept notes are important because they help to identify potential stakeholders and funders for a proposed project. By providing a brief overview of the project, concept notes help to gauge interest and support. This is especially important when dealing with multiple potential stakeholders and funders, as it allows the organization to tailor their proposal to the interests of each party.

Moreover, concept notes help organizations to save time and resources. Instead of preparing a full proposal for every potential stakeholder or funder, concept notes can be used to filter out those who are not interested in the project, allowing the organization to focus on those who are.

When to Use a Concept Note?

Concept notes are usually requested by potential stakeholders and funders before a full project proposal is submitted. They can also be used to introduce a new project to an organization or community. In addition, concept notes can be used as a tool for internal planning and decision-making.

For example, a company may use a concept note to introduce a new product or service to its employees before launching it to the public. This allows the company to gather feedback and make any necessary changes before investing resources into a full launch.

In conclusion, concept notes are an important tool for organizations to attract support and funding for their projects. By providing a brief overview of the project, concept notes help to gauge interest and support, saving time and resources. They can be used to introduce new projects to stakeholders and funders, as well as for internal planning and decision-making.

Key Components of a Concept Note

The following are key components that should be included when writing a concept note:

Project Title

The project title should be clear and concise. It should capture the essence of the project in a few words.

Project Objective

The project objective should be clearly stated, and should contain a succinct statement of what the project intends to achieve.

Background and Context

The background and context should provide an overview of the problem that the project intends to address. It should also highlight the relevance of the problem to the target audience and the broader community.

Target Audience and Beneficiaries

The target audience and beneficiaries should be clearly identified. This helps to ensure that the project is designed to meet the needs of the intended beneficiaries.

Project Activities and Methodology

The project activities and methodology should describe the specific steps that will be taken to achieve the project objectives. It should also provide details on how the project will be implemented.

Expected Outcomes and Impact

The expected outcomes and impact should clearly state what the project hopes to achieve and how it will contribute to the broader goals of the organization or community.

Monitoring and Evaluation

The monitoring and evaluation plan should outline how the project will be monitored and evaluated to determine its success.

Budget and Resources

The budget and resources section should provide a detailed breakdown of the costs associated with the project, as well as the resources required to implement it.

Step-by-Step Guide to Writing a Concept Note

Now that we have covered the key components of a concept note, it is time to take you through a step-by-step guide to writing a winning concept note.

Step 1: Research and Preparation

Before you start writing your concept note, it is important to conduct thorough research on the problem you are seeking to address, the target audience, and the available resources. This will help you to develop a comprehensive understanding of the project and its requirements.

Step 2: Develop a Clear Project Objective

The project objective is the backbone of your concept note. It should be clear, concise, and specific. A well-defined objective will help you to stay focused on the project and ensure that the project is designed to achieve the intended outcomes.

Step 3: Provide a Strong Background and Context

The background and context section of your concept note should provide a clear understanding of the problem the project intends to address and its relevance to the target audience and the broader community. This section should demonstrate the importance of the project and why it is needed.

Step 4: Identify Your Target Audience and Beneficiaries

The target audience and beneficiaries section of your concept note should clearly identify who the project is meant to benefit. This section should also provide details on how the project will improve the lives of the intended beneficiaries.

Step 5: Outline Your Project Activities and Methodology

The project activities and methodology section of your concept note should provide a detailed explanation of how the project will achieve its objectives. This section should outline the specific steps that will be taken to implement the project and achieve the desired outcomes.

Step 6: Describe Expected Outcomes and Impact

The expected outcomes and impact section of your concept note should detail the expected results of the project and how they will contribute to the broader goals of the organization or community. This section should also provide a clear understanding of the impact the project is expected to have on the beneficiaries.

Step 7: Develop a Monitoring and Evaluation Plan

The monitoring and evaluation plan should outline how the project will be monitored and evaluated to determine its success. This section should also include the indicators that will be used to measure the project's impact.

Step 8: Prepare a Budget and Identify Resources

The budget and resources section of your concept note should provide a detailed breakdown of the costs associated with the project, as well as the resources required to implement it. This section should also include details on how the project will be funded.

By following these steps, you will be able to develop a comprehensive and winning concept note that will help you to secure funding for your project. Remember to keep your concept note clear, concise and focused on the project objectives. Good luck!

ChatGPT Prompt for Writing a Concept Note

Chatgpt prompt.

Please prepare a comprehensive and detailed document outlining the key ideas, objectives, and strategies for a proposed project or initiative. This document should clearly articulate the purpose of the project, the target audience, the expected outcomes, and the resources required to implement it. The concept note should be well-structured, concise, and informative, providing a clear roadmap for the proposed project and demonstrating its potential impact and value.

[ADD ADDITIONAL CONTEXT. CAN USE BULLET POINTS.]

Recommended Articles

How to write a case note: a step-by-step guide, how to write a comprehensive dap note, feeling behind on ai, get the latest ai.

- Cambridge Libraries

Study Skills

Research skills.

- Searching the literature

- Note making for dissertations

- Research Data Management

- Copyright and licenses

- Publishing in journals

- Publishing academic books

- Depositing your thesis

- Research metrics

- Build your online profile

- Finding support

Note making for dissertations: First steps into writing

Note making (as opposed to note taking) is an active practice of recording relevant parts of reading for your research as well as your reflections and critiques of those studies. Note making, therefore, is a pre-writing exercise that helps you to organise your thoughts prior to writing. In this module, we will cover:

- The difference between note taking and note making

- Seven tips for good note making

- Strategies for structuring your notes and asking critical questions

- Different styles of note making

To complete this section, you will need:

- Approximately 20-30 minutes.

- Access to the internet. All the resources used here are available freely.

- Some equipment for jotting down your thoughts, a pen and paper will do, or your phone or another electronic device.

Note taking v note making

When you think about note taking, what comes to mind? Perhaps trying to record everything said in a lecture? Perhaps trying to write down everything included in readings required for a course?

- Note taking is a passive process. When you take notes, you are often trying to record everything that you are reading or listening to. However, you may have noticed that this takes a lot of effort and often results in too many notes to be useful.

- Note making , on the other hand, is an active practice, based on the needs and priorities of your project. Note making is an opportunity for you to ask critical questions of your readings and to synthesise ideas as they pertain to your research questions. Making notes is a pre-writing exercise that develops your academic voice and makes writing significantly easier.

Seven tips for effective note making

Note making is an active process based on the needs of your research. This video contains seven tips to help you make brilliant notes from articles and books to make the most of the time you spend reading and writing.

- Transcript of Seven Tips for Effective Notemaking

Question prompts for strategic note making

You might consider structuring your notes to answer the following questions. Remember that note making is based on your needs, so not all of these questions will apply in all cases. You might try answering these questions using the note making styles discussed in the next section.

- Question prompts for strategic note making

- Background question prompts

- Critical question prompts

- Synthesis question prompts

Answer these six questions to frame your reading and provide context.

- What is the context in which the text was written? What came before it? Are there competing ideas?

- Who is the intended audience?

- What is the author’s purpose?

- How is the writing organised?

- What are the author’s methods?

- What is the author’s key argument and conclusions?

Answer these six questions to determine your critical perspectivess and develop your academic voice.

- What are the most interesting/compelling ideas (to you) in this study?

- Why do you find them interesting? How do they relate to your study?

- What questions do you have about the study?

- What could it cover better? How could it have defended its research better?

- What are the implications of the study? (Look not just to the conclusions but also to definitions and models)

- Are there any gaps in the study? (Look not just at conclusions but definitions, literature review, methodology)

Answer these five questions to compare aspects of various studies (such as for a literature review.

- What are the similarities and differences in the literature?

- Critically analyse the strengths, limitations, debates and themes that emerg from the literature.

- What would you suggest for future research or practice?

- Where are the gaps in the literature? What is missing? Why?

- What new questions should be asked in this area of study?

Styles of note making

- Linear notes . Great for recording thoughts about your readings. [video]

- Mind mapping : Great for thinking through complex topics. [video]

Further sites that discuss techniques for note making:

- Note-taking techniques

- Common note-taking methods

- Strategies for effective note making

Did you know?

How did you find this Research Skills module

Image Credits: Image #1: David Travis on Unsplash ; Image #2: Charles Deluvio on Unsplash

- << Previous: Searching the literature

- Next: Research Data Management >>

- Last Updated: Apr 11, 2024 9:35 AM

- URL: https://libguides.cam.ac.uk/research-skills

© Cambridge University Libraries | Accessibility | Privacy policy | Log into LibApps

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What Is a Thesis? | Ultimate Guide & Examples

What Is a Thesis? | Ultimate Guide & Examples

Published on September 14, 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on April 16, 2024.

A thesis is a type of research paper based on your original research. It is usually submitted as the final step of a master’s program or a capstone to a bachelor’s degree.

Writing a thesis can be a daunting experience. Other than a dissertation , it is one of the longest pieces of writing students typically complete. It relies on your ability to conduct research from start to finish: choosing a relevant topic , crafting a proposal , designing your research , collecting data , developing a robust analysis, drawing strong conclusions , and writing concisely .

Thesis template

You can also download our full thesis template in the format of your choice below. Our template includes a ready-made table of contents , as well as guidance for what each chapter should include. It’s easy to make it your own, and can help you get started.

Download Word template Download Google Docs template

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Thesis vs. thesis statement, how to structure a thesis, acknowledgements or preface, list of figures and tables, list of abbreviations, introduction, literature review, methodology, reference list, proofreading and editing, defending your thesis, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about theses.

You may have heard the word thesis as a standalone term or as a component of academic writing called a thesis statement . Keep in mind that these are two very different things.

- A thesis statement is a very common component of an essay, particularly in the humanities. It usually comprises 1 or 2 sentences in the introduction of your essay , and should clearly and concisely summarize the central points of your academic essay .

- A thesis is a long-form piece of academic writing, often taking more than a full semester to complete. It is generally a degree requirement for Master’s programs, and is also sometimes required to complete a bachelor’s degree in liberal arts colleges.

- In the US, a dissertation is generally written as a final step toward obtaining a PhD.

- In other countries (particularly the UK), a dissertation is generally written at the bachelor’s or master’s level.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

The final structure of your thesis depends on a variety of components, such as:

- Your discipline

- Your theoretical approach

Humanities theses are often structured more like a longer-form essay . Just like in an essay, you build an argument to support a central thesis.

In both hard and social sciences, theses typically include an introduction , literature review , methodology section , results section , discussion section , and conclusion section . These are each presented in their own dedicated section or chapter. In some cases, you might want to add an appendix .

Thesis examples

We’ve compiled a short list of thesis examples to help you get started.

- Example thesis #1: “Abolition, Africans, and Abstraction: the Influence of the ‘Noble Savage’ on British and French Antislavery Thought, 1787-1807” by Suchait Kahlon.

- Example thesis #2: “’A Starving Man Helping Another Starving Man’: UNRRA, India, and the Genesis of Global Relief, 1943-1947″ by Julian Saint Reiman.

The very first page of your thesis contains all necessary identifying information, including:

- Your full title

- Your full name

- Your department

- Your institution and degree program

- Your submission date.

Sometimes the title page also includes your student ID, the name of your supervisor, or the university’s logo. Check out your university’s guidelines if you’re not sure.

Read more about title pages

The acknowledgements section is usually optional. Its main point is to allow you to thank everyone who helped you in your thesis journey, such as supervisors, friends, or family. You can also choose to write a preface , but it’s typically one or the other, not both.

Read more about acknowledgements Read more about prefaces

An abstract is a short summary of your thesis. Usually a maximum of 300 words long, it’s should include brief descriptions of your research objectives , methods, results, and conclusions. Though it may seem short, it introduces your work to your audience, serving as a first impression of your thesis.

Read more about abstracts

A table of contents lists all of your sections, plus their corresponding page numbers and subheadings if you have them. This helps your reader seamlessly navigate your document.

Your table of contents should include all the major parts of your thesis. In particular, don’t forget the the appendices. If you used heading styles, it’s easy to generate an automatic table Microsoft Word.

Read more about tables of contents

While not mandatory, if you used a lot of tables and/or figures, it’s nice to include a list of them to help guide your reader. It’s also easy to generate one of these in Word: just use the “Insert Caption” feature.

Read more about lists of figures and tables

If you have used a lot of industry- or field-specific abbreviations in your thesis, you should include them in an alphabetized list of abbreviations . This way, your readers can easily look up any meanings they aren’t familiar with.

Read more about lists of abbreviations

Relatedly, if you find yourself using a lot of very specialized or field-specific terms that may not be familiar to your reader, consider including a glossary . Alphabetize the terms you want to include with a brief definition.

Read more about glossaries

An introduction sets up the topic, purpose, and relevance of your thesis, as well as expectations for your reader. This should:

- Ground your research topic , sharing any background information your reader may need

- Define the scope of your work

- Introduce any existing research on your topic, situating your work within a broader problem or debate

- State your research question(s)

- Outline (briefly) how the remainder of your work will proceed

In other words, your introduction should clearly and concisely show your reader the “what, why, and how” of your research.

Read more about introductions

A literature review helps you gain a robust understanding of any extant academic work on your topic, encompassing:

- Selecting relevant sources

- Determining the credibility of your sources

- Critically evaluating each of your sources

- Drawing connections between sources, including any themes, patterns, conflicts, or gaps

A literature review is not merely a summary of existing work. Rather, your literature review should ultimately lead to a clear justification for your own research, perhaps via:

- Addressing a gap in the literature

- Building on existing knowledge to draw new conclusions

- Exploring a new theoretical or methodological approach

- Introducing a new solution to an unresolved problem

- Definitively advocating for one side of a theoretical debate

Read more about literature reviews

Theoretical framework

Your literature review can often form the basis for your theoretical framework, but these are not the same thing. A theoretical framework defines and analyzes the concepts and theories that your research hinges on.

Read more about theoretical frameworks

Your methodology chapter shows your reader how you conducted your research. It should be written clearly and methodically, easily allowing your reader to critically assess the credibility of your argument. Furthermore, your methods section should convince your reader that your method was the best way to answer your research question.

A methodology section should generally include:

- Your overall approach ( quantitative vs. qualitative )